2. Ways of Touching Manuscripts

© 2023 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0337.02

My typology of manuscript damage is divided into two large designations: I. inadvertent wear; and II. targeted wear, with further varieties of damage falling beneath these two headings. These categories then operate throughout the rest of the book and in the subsequent volumes. Wear resulted from explicit physical attention to the objects and people depicted in manuscripts, but also to some words and even types of decoration. Often this attention was targeted not at the whole figure but at a particular detail, such as the face, hands, or feet, or in the case of words, an initial. Targeted wear accumulates, so that multiple acts of reading/handling wear down an image, soften its outlines, and erode paint layers. Targeted wear, like inadvertent wear, can result from habituated actions, and much of it arises from two opposing feelings: veneration or belligerence. Layered onto these two categories are two sets of motivations, although these might overlap or be indistinguishable: the actions resulting from strong emotions, or from codified ritual.1

I. Inadvertent Wear

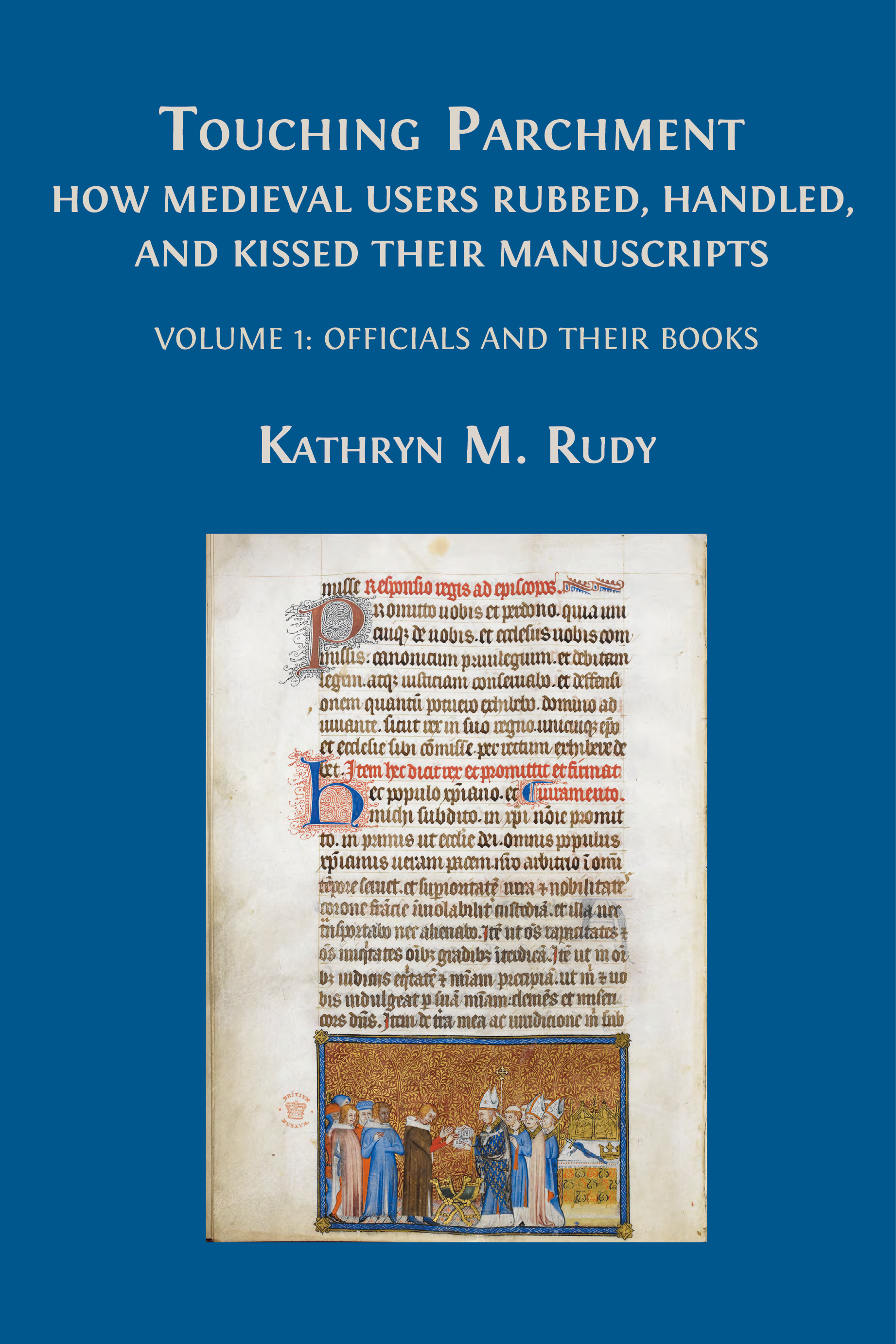

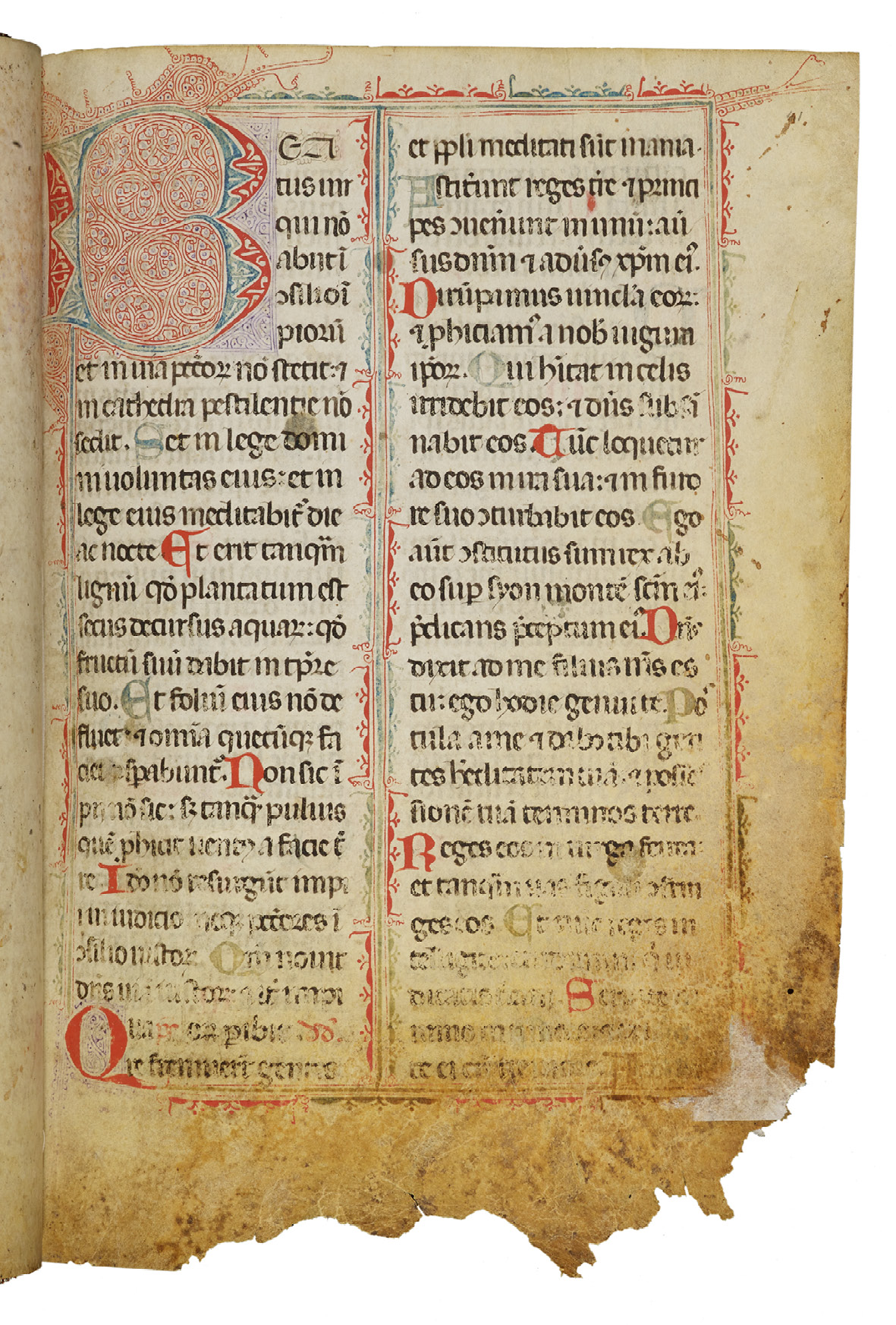

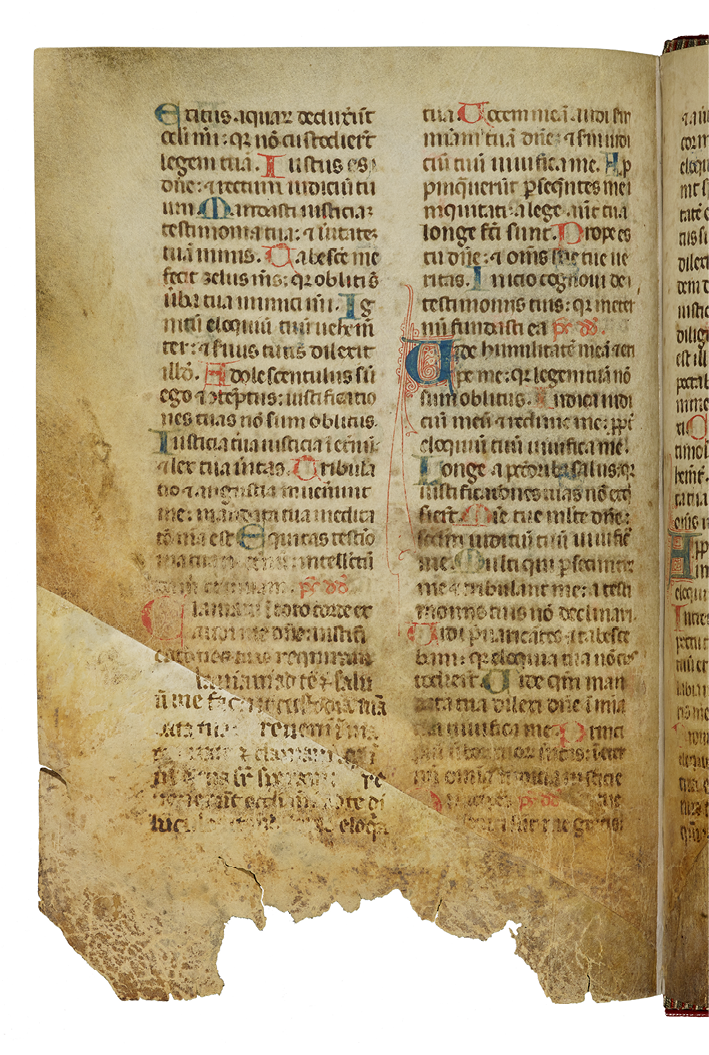

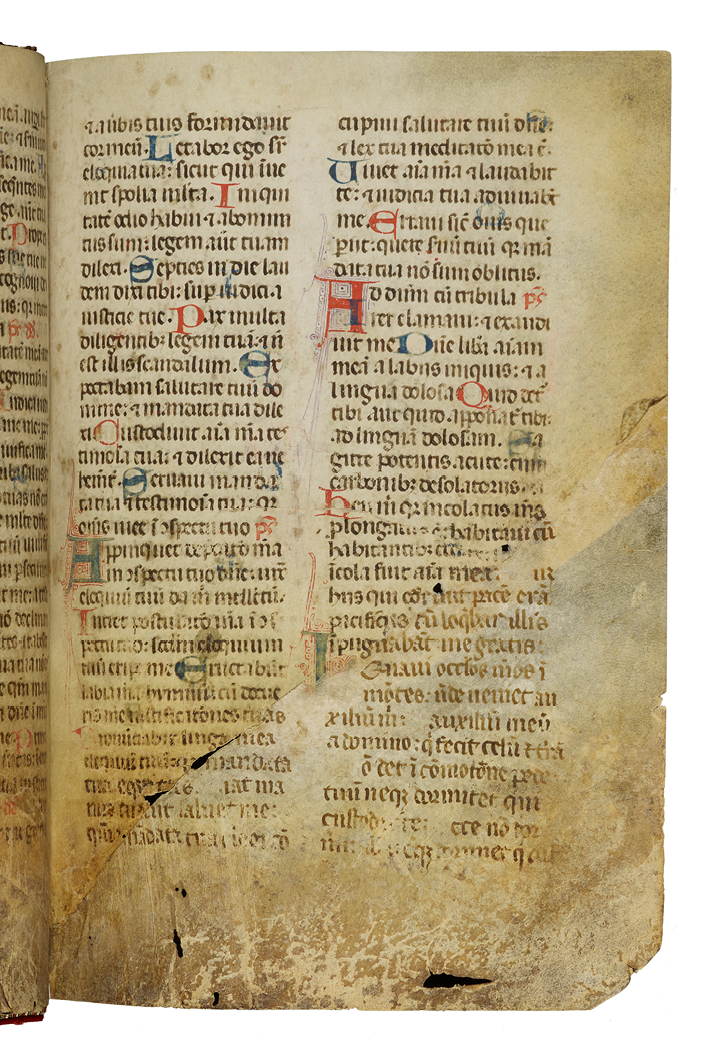

Owners inadvertently left signs of their presence simply by handling their books vigorously over time. A primitive choir breviary made in the last quarter of the thirteenth century in Provence has been so vigorously handled that the moisture from and contact with the user’s hands have caused the lower corner of the book to become friable and disintegrate (OBL, Ms. Lat. Liturg. d. 7; Fig. 4).2 In a whole section from folios 83 to 91, these damaged corners were cut away and new ones pasted in (Fig. 5). A medieval scribe has rewritten the texts onto those corners in an old-fashioned script to try to match the rest of the page. But even the replacement areas were so vigorously handled that they degraded, yellowed, and became brittle with moisture damage (presumably moisture from sweaty hands). More texts, in the form of entire quires, were also added in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. These repairs and additions indicate that the manuscript was in continuous use for several hundred years; its users repaired it to keep it functional even as it gradually disintegrated.3 In the modern era, the manuscript was owned by John Th. Payne, a London bookseller, and then sold at Sotheby’s on 30 April 1857. Trying to mask the extensive wear and discoloration, someone, possibly Mr. Payne, guillotined the book block and then gilded its edges before rebinding the volume.

Fig. 4 Heavily worn folio in a choir breviary, at the incipit Beatus vir. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Lat. Liturg. d. 7, fol. 41r.

Fig. 5 Opening in a choir breviary, with replaced corners. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Lat. Liturg. d. 7, fol. 88v-89r.

II. Targeted Wear

The way damage looks on the page usually allows one to distinguish between targeted and inadvertent wear. Whereas inadvertent wear is often confined to the edges of the page, to the margin, or to the upper layer of surface (from such causes as splashes of holy water, wine, rainwater, or wax), targeted wear often appears in the middle of the page and digs down into the layers. Targeted wear requires a motive, a desire to interact with a word, image, part of an image, or a shape (such as a decorative form). Here I do not explore the technical analysis of chemicals or paint solubility (other than to note that tempera and ink are water soluble), but rely entirely on the senses—specifically, close visual, tactile, and auditory perception. Parchment that has been wetted re-dries in such a way that it can change a book’s acoustics, just as repeatedly bending and unbending can soften parchment, and abrasion can change the surface texture, making it either shinier or more velvety.

Consider the following ways in which users could touch books, which can explain the patterns of wear found in late medieval manuscripts.

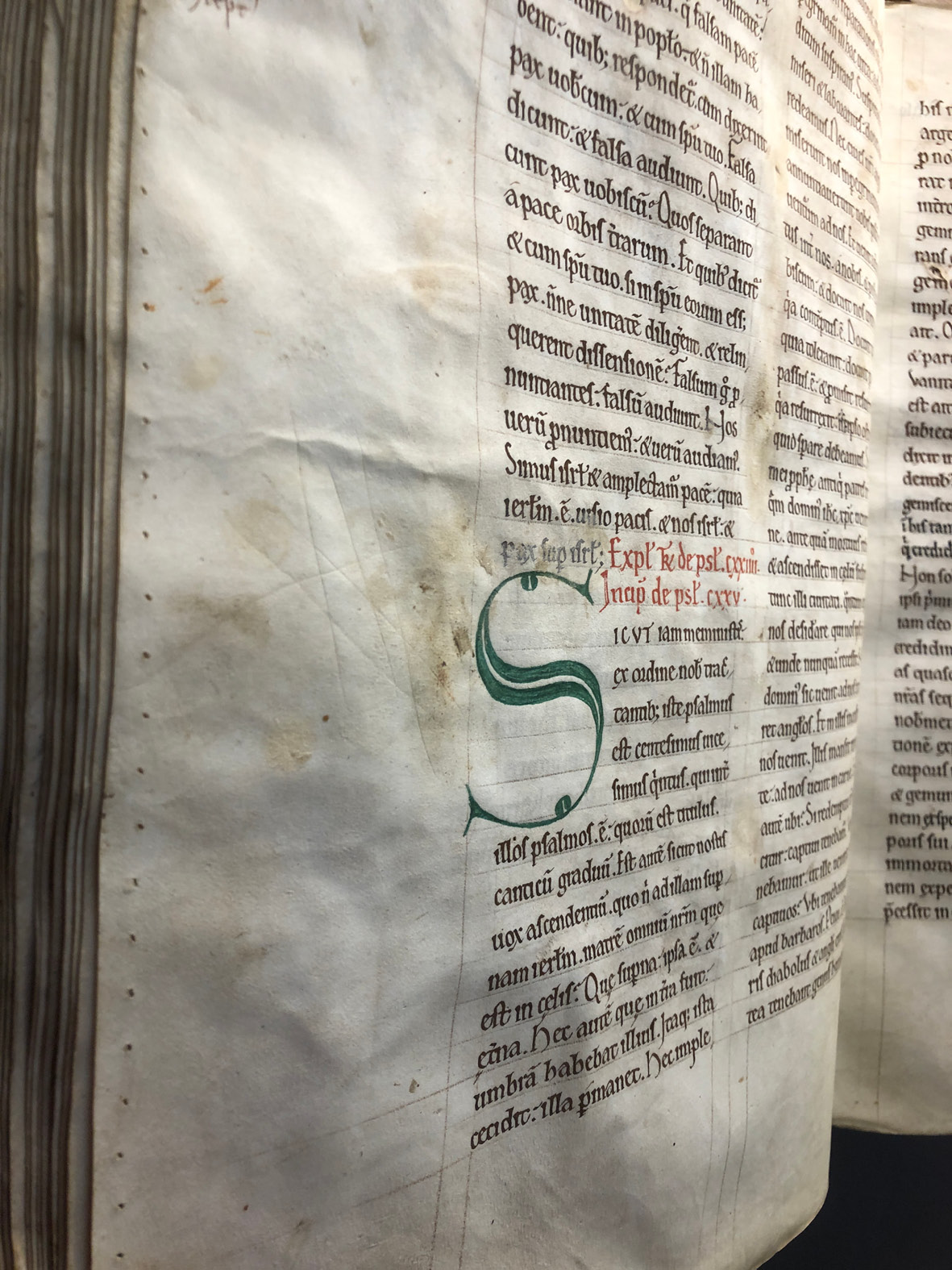

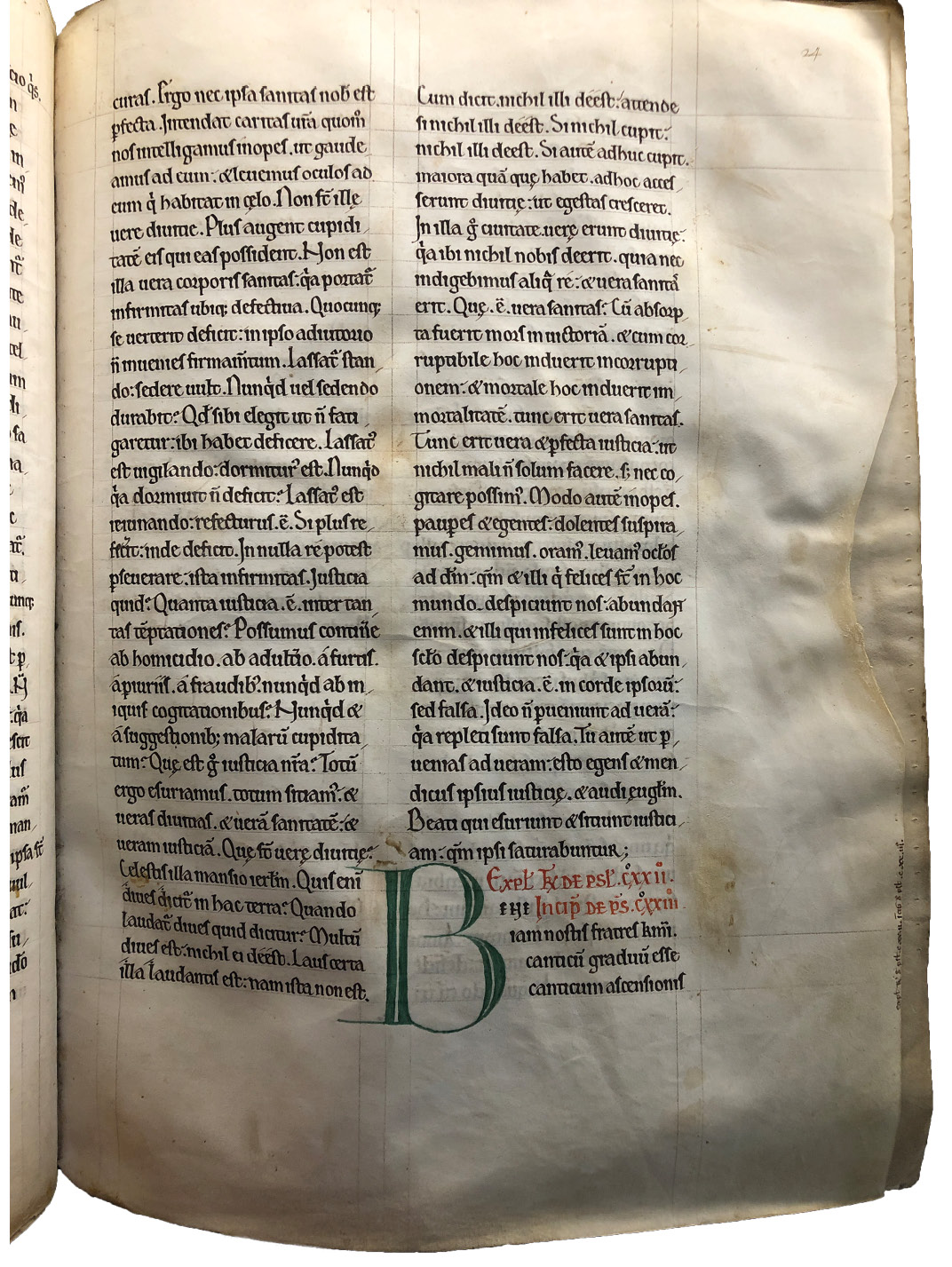

Depositing Wax

In the previous section, I proposed that wax stains constituted a form of inadvertent wear, part of the vicissitudes of handling books in the vicinity of lighted candles. However, readers could also deposit wax on purpose. An example appears in a twelfth-century manuscript containing Augustine’s commentary on Psalms CXIX-CL (OBL, Ms. Bodl. 241; Fig. 6 and Fig. 7).4 It belonged to Reading Abbey, where monks would have read the text aloud in the refectory. Hundreds of carefully placed wax stains dot the margins.5 They largely correspond to the textual divisions and are distinct from the “nota” signs inscribed in pen in the margins. Photographing the folios in raking light reveals how the wax caused distortions in the parchment, and it also reveals how several spots of wax (near the capital S and B, respectively) were scraped off, probably with a fingernail. The monk reading the collation may have signalled where the next day’s reading was to begin by depositing a ball of soft wax in the margin, and then scraping the wax off when he next progressed through the reading. In other words, the blobs of wax functioned like temporary place markers. This phenomenon is difficult to detect, since monks would scrape the wax off after use, and the residue is nearly invisible under traditional photography.

Fig. 6 Folio of Augustine’s commentary on Psalms from Reading Abbey, with wax stains, photographed in raking light. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodl. 241, fol. 33v

Fig. 7 Folio of Augustine’s commentary on Psalms from Reading Abbey, with wax stains. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodl. 241, fol. 24r

Ritualized Kissing

Users often kissed books. Sometimes the object of the kiss was the entire book (in which case the book could be closed) and sometimes it was an image, word, or letter within the book (which necessitated opening the book). Persons in authority performed this technique according to types of books and places within them (as when priests kissed missals). Moisture from the mouth could deform the parchment, weaken it, and make it wrinkle. Parchment that has been kissed may become tacky, so that it adheres to whatever surface touches it. This could result in paint transfer onto the facing page. Furthermore, paint that has been moistened through kissing can become smeared or streaky. Another of the by-products of kissing is inadvertent application of facial oils to the parchment. This can cause parchment to become darkened, shiny, and/or translucent.

Touching with a Wet (Kissed) Finger to Transport a Kiss

Just as a pax can carry the kiss from a priest’s mouth to his congregation, his finger could also carry a kiss from his mouth to the book. In effect, the finger mediated between the breath of a priest and the Word of God, as inscribed on the surface of the manuscript. In several examples, one can discern the whorls of a fingerprint stamped onto the manuscript; this could only have resulted from touching the book with a wet finger.

Many wet-touched initials appear in religious service books (such as Bodley missal Canon. Liturg. 344, for which see Figs 49–50). Officiants performed this gesture in order to venerate the Word of God while preserving the script: they often limited their touching to the oversized beginning letters. An initial stands for the text as a whole. A single wet-touching alone could mark the painted image; this partly depends on the water solubility of the inks and paints used. Although I cannot always distinguish the wear of wet lips from the wear of a wet finger, I suspect that readers preferred the finger when aiming at a small target. When wetting their fingers and books in this way, perhaps users sought to physicalize their emotional bonds with the Word or the figure behind the image depicted. Perhaps they wanted to forge a link between their breath and the book’s words.

Touching a Book Cover with a Dry Hand

Besides opening a book, other motivations exist for touching it: to carry it ceremoniously, affirm one’s adherence to a book-based dogma, or swear an oath. Oath-swearing was sometimes performed on a closed book, and sometimes on an open one. Such acts recognize the book’s cultural gravitas and treat the book—which contains the Word of God—as a relic.

Touching a Mark (Image, Text, or Decoration Within a Book) with a Dry Hand

Touching a mark with a dry hand implies a desire to be in physical proximity to an image, word, or decoration. Touching it with a finger, rather than with the whole hand, changes the gesture, making it more precise, so that one might only touch the depicted face or hem, a detail of the decoration, or a particular word in a text. This form of touching might also externalize one’s progress through a text. While a single event of touching may not register on the surface, repeated acts will dislodge the ink, paint, or gold, while depositing dirt and oil, so that its cumulative effects register a reader’s presence in the book. Those touching it could reach into the book lying open on a lectern; they could have their eyes on a page other than the one they were touching, or they could touch a book that was proffered to them. These situations will result in different patterns of wear.

Among this kind of cumulative wear, one can identify two subsets: a single individual touching the same image many times, or many people touching a particular image once. These activities result in different kinds of wear: an individual who touches a book repeatedly does so out of habit, and therefore touches it the same way each time. This results in neat, localized paint loss. In contrast, when large numbers of people each touch a painting once, they tend to do so differently from one another. They are not acting out of personal habit, but according to conventions adopted by particular groups of people. They might place the hand on an image to swear an oath upon the figure represented. Touching the image binds them with both the image and other members of this group. Because each act of touching is unique, the paint loss from these cumulative acts usually falls over a wider area and has an indistinct edge. Some beholders feel confident enough to touch the eyes depicted in the images with full contact; others touch the hem, or just lightly touch the represented chin. The motivation in play here is to publicly proclaim group membership, physically declaring one’s allegiance—frequently in a public setting.

Touching a Mark (Image, Text, or Decoration) with a Body Part Other Than the Hand

Some rituals call for the pressing of a manuscript to the body as a medicinal aid. The body part may be the forehead, or the abdomen of a woman in labor, for example. Most of these forms of touch depend on belief in the apotropaic power of manuscripts and amount to the practice of sympathetic magic. They are performed for the benefit of the person who is touching the book. The feeling involved here might be both despair and hope. Examples of this kind of touching will be taken up in Volumes 2 and 3.

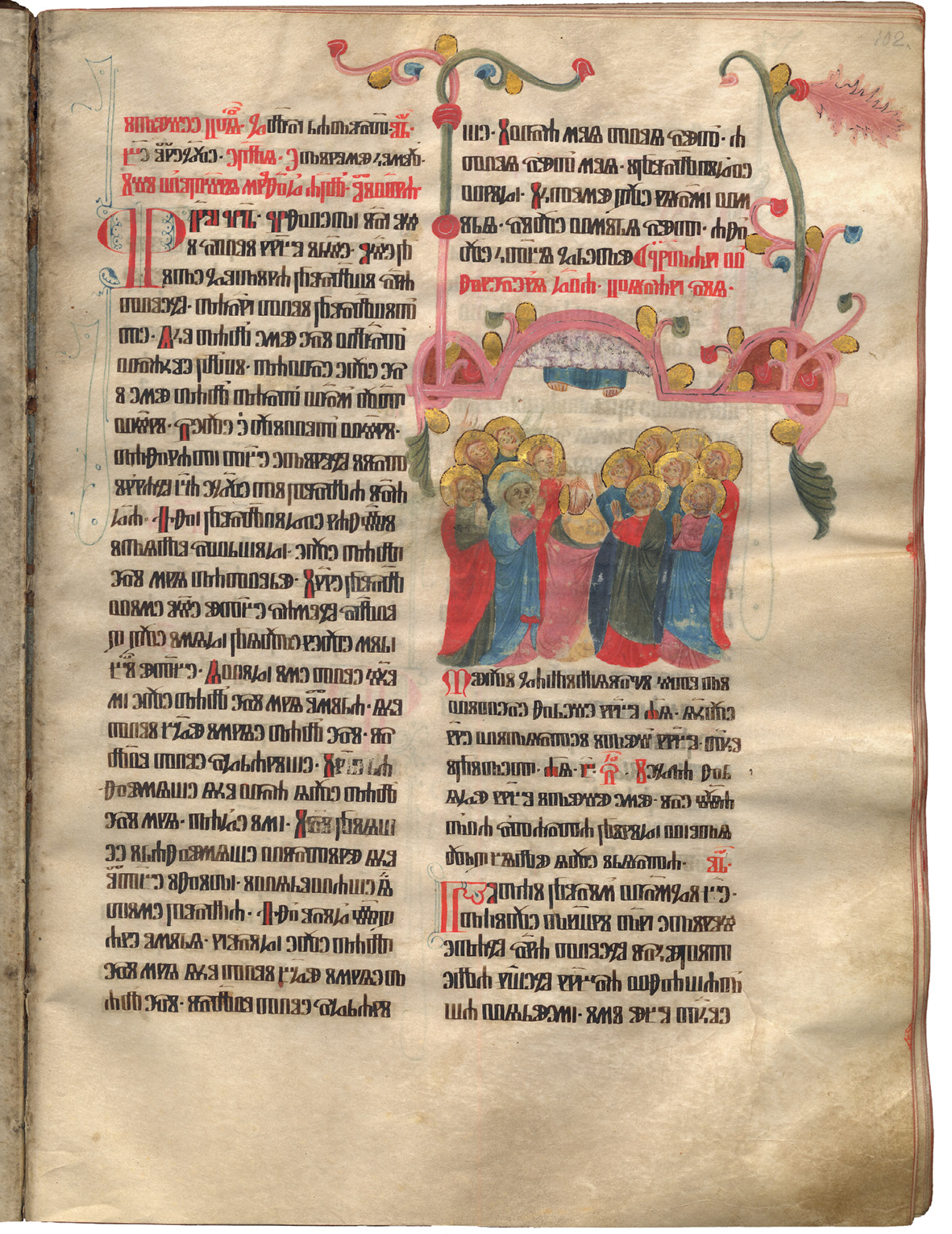

Dramatizing with a Finger

Someone has touched the apostles and Mary at the scene of the Ascension of Christ in a Roman missal written in ca. 1380–1420 in Church Slavonic and Croatian (Fig. 8).6 This missal is illuminated with relevant pictorial subjects and not simply a Crucifixion image, as many late medieval missals are (as discussed below in Chapter 4). The book’s user, presumably a priest or bishop, has not only touched the figures’ hems and faces with a wet finger—with special attention to the Virgin in blue—but he has also traced the path of their gaze upward as they watch Christ disappear into the firmament.

Fig. 8 Folio from a missal, with the Ascension of Christ, ca. 1380–1420. Ljubliana, The National and University Library of Slovenia, Ms. 162, fol. 102r. Public domain image provided by Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica

Erasing/Rubbing Out with a Finger

Whereas dramatizing with a finger usually involves a single quick gesture, erasing with a finger involves a back-and-forth motion. Its purpose is to rub out the representation, and thereby to demonstrate one’s moral position toward it. Devils, torturers, and other antagonists often receive this treatment, as do specific body parts: users often attack the heads and faces of figures to destroy them (as opposed to the feet, which seem only to be kissed in reverence). This act allows viewers to rise in anger and hatred, and to expunge the devil by attacking his picture. In some cases, beholders are merely taking cues from the Virgin, who was said to deface the devil.7 Whereas the destruction of figural forms from veneration often accumulates over many reading events, destruction from negation can be accomplished in an instant. While a person who touches an image for dramatic effect may not intend to destroy it, someone who touches it to erase it does so with destruction as his or her goal.

Sewing Curtains to the Page

In the interiors of their books, owners could sew curtains over an image, a word, or an entire page. As Christine Sciacca argues, the primary reason for medieval users to sew in curtains was to protect metallic pigment, to use the silk as interleaving material, but also to cover an image. Unveiling the illumination would result in a ceremonial moment of revelation.8 Veiling directs attention to a particular area of the book by temporarily obscuring it; unveiling ritualizes a gesture effected in parallel with reading. Sewing curtains into a manuscript involved two acts of piety. First, to place a particular image under a veil was to dress it in a luxury “jacket” that marked it as special, an act which elevated prized manuscripts to the level of relics.9 Second, each act of lifting the curtain created a ritual of veneration. The initial sewing and the later manipulation both cause targeted wear, and the two activities each leave telltale traces: the first leaves rows of needle holes, even when the curtain itself has been removed. The second causes a cumulative, often dark, scuff on the image or its frame where the thumb makes repeated contact. The sewing process brings about secondary rubbing, not on the image but near it.10 The practice of sewing curtains into manuscripts was not uncommon: in the Morgan Library alone, no fewer than 13 manuscripts have curtains or needle holes that imply missing curtains, many of them luxury Gospel manuscripts.11 Needle holes also appear at the tops of many full-page miniatures in books of hours; these will be taken up in Volume 3.

Other Kinds of Sewing

Users could sew protrusions, such as leather or parchment knots, or textile or parchment tabs, to the fore-edge to create a permanent bookmark. Their presence implies an overt use of the sense of touch (and not just the senses of sight and proprioception) to navigate through the leaves.

Parchment makers also repaired holes in parchment by suturing them. Scribes often interact with these holes, as with one scribe who continued the stitches to create a triangular face that seems to be sewn to the page (Fig. 9). To experience them fully, one would have to touch them.

Fig. 9 Margin in a missal with a repair, from a missal from the Knights Hospitallers, Southern Germany, 1469. ’s-Heerenberg, The Netherlands, Collection Dr. J. H. van Heek, Huis Bergh Foundation, Ms. 15. Image © The Huis Bergh Foundation, CC BY 4.0

***

All these forms of touching demonstrate that medieval manuscripts could inspire a wide range of interactions, not merely reading and viewing. The abrading gestures could occur with wet or dry techniques, directly with the body or mediated by instruments, by one person or by many, and on a continuum from spontaneous to premeditated. These variations produced different marks on the page and corresponded to diverse situations and states of mind. Among these intersection possibilities, one can observe a strong correlation between those readers who added objects to their manuscripts such as images, badges, and curtains, and those who regularly and heavily handled their books. That being the case, a single manuscript might exhibit wear from several of the categories outlined above. (Case studies of manuscripts that received multiple, complex forms of touching will appear in Volume 4.)

Distinguishing targeted wear from regular hard use can sometimes be difficult; of the dozens of examples of targeted wear considered in this study, most are quite clear, but a few are ambiguous. When seeking to untangle the causes of various forms of wear, I have asked of each example: How did the medieval person hold this book? What was the context of use—where and with what community of objects was the manuscript used? Was this book placed on a lectern, prie-dieu, or altar, or was it held in the hands? Could the excessive wear have been the result of regular handling? Is there a pattern of targeted wear across several folios in the manuscript (which would further suggest that the wear had been administered intentionally)? Do the patterns of wear across the entire book result from the use of the book in a ritual? Does other circumstantial evidence corroborate that the damage occurred in the Middle Ages rather than in the post-medieval period?

Occasionally one finds stray marks or signs of wear in manuscripts that are difficult to interpret: Are they traces of targeted wear or not? One such example is provided by a fingerprint on the face of a man building the Tower of Babel (Fig. 10). I doubt that this fingerprint represents an act of targeted wear, because no larger pattern of repeated wear appears in this manuscript; it seems unlikely that this anonymous figure would have elicited a sufficiently strong response to motivate a viewer to deliberately touch the image. My working assumption is that targeted wear would always have been linked to emotional motivation, and ought to make coherent sense within the context of a given volume. In the case of the Tower of Babel, I suspect that we are encountering the mark of a stray wet finger. In short, some signs of wear resist unambiguous interpretation, and I do not assume that every fingerprint, stain, and smudge in a given manuscript was purposefully aimed at a particular image.

Fig. 10 Tower of Babel, from Guiard des Moulins, Grande Bible Historiale Complétée, written and illuminated in Paris, 1371–1372. The Hague, Meermanno Museum, Ms. 10 B 23, fol. 19r

1 Andrew H. Chen, in Flagellant Confraternities and Italian Art, 1260–1610: Ritual and Experience (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), convincingly argues that ritual tempers and shapes emotion.

2 S.J.P. Van Dijk, Handlist of Latin Liturgical Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, 8 vols. (typescript 1957–1960), Service Books, p. 242. According to Van Dijk, in the fourteenth century the book belonged to Apt cathedral. Among the fifteenth-century additions in the calendar (6v) is the name of Casper de Chatillinge.

3 See Rudy, Piety in Pieces (2016), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0094.

4 Otto Pächt and J. J. G. Alexander, Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library Oxford (Vol. 2), edited by J. J. G. Alexander (Clarendon Press, 1966–1973), p. 119.

5 There are also some places where the candle spilled hot wax accidentally.

6 For a catalogue description and a full digitization of the Croatian missal (Lubljana, National and University Library, Ms. 162), see https://www.nuk.uni-lj.si/sites/default/files/dokumenti/2015/katalog_rokopisov.pdf

7 Deirdre Jackson, “Virgin, Devil, Bishop, King: Nicola Pisano’s Pulpit in Siena and Alfonso X’s Cantigas de Santa Maria,” Illuminating the Middle Ages: Tributes to Prof. John Lowden from His Students, Friends and Colleagues (Vol. 79 of the Library of the Written Word series), edited by Laura Cleaver, Alixe Bovey and Lucy Donkin, (Brill, 2020), pp. 259–75.

8 See Christine Sciacca, “Raising the Curtain on the Use of Textiles in Manuscripts,” in Weaving, Veiling, and Dressing: Textiles and Their Metaphors in the Late Middle Ages (Medieval Church Studies), edited by Kathryn M. Rudy and Barbara Baert (Brepols, 2007), pp. 161–90.

9 Sciacca makes this point, p. 163.

10 For an example (London BL, Harley Ms. 2966), see Kathryn M. Rudy, “Kissing Images” (2011).

11 According to Corsair (http://corsair.themorgan.org/index.html), the manuscripts in the Morgan Library with current or former curtains are G.24; G.44 (curtains removed, housed separately); G.48; M.1149; M.311; M.440; M.708; M.709; M.710; M.711; M.780; M.833; M.939. I thank Maria Fredericks for alerting me to the rich textiles in the Morgan’s manuscript collection. See Morgan Simms Adams, “Identifying Evidence of Textile Curtains in Medieval Manuscripts in the Morgan Library & Museum,” Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding (Vol. 6), (The Legacy Press, 2020), pp. 2–61.