5. Swearing: From Gospels to Legal Manuscripts

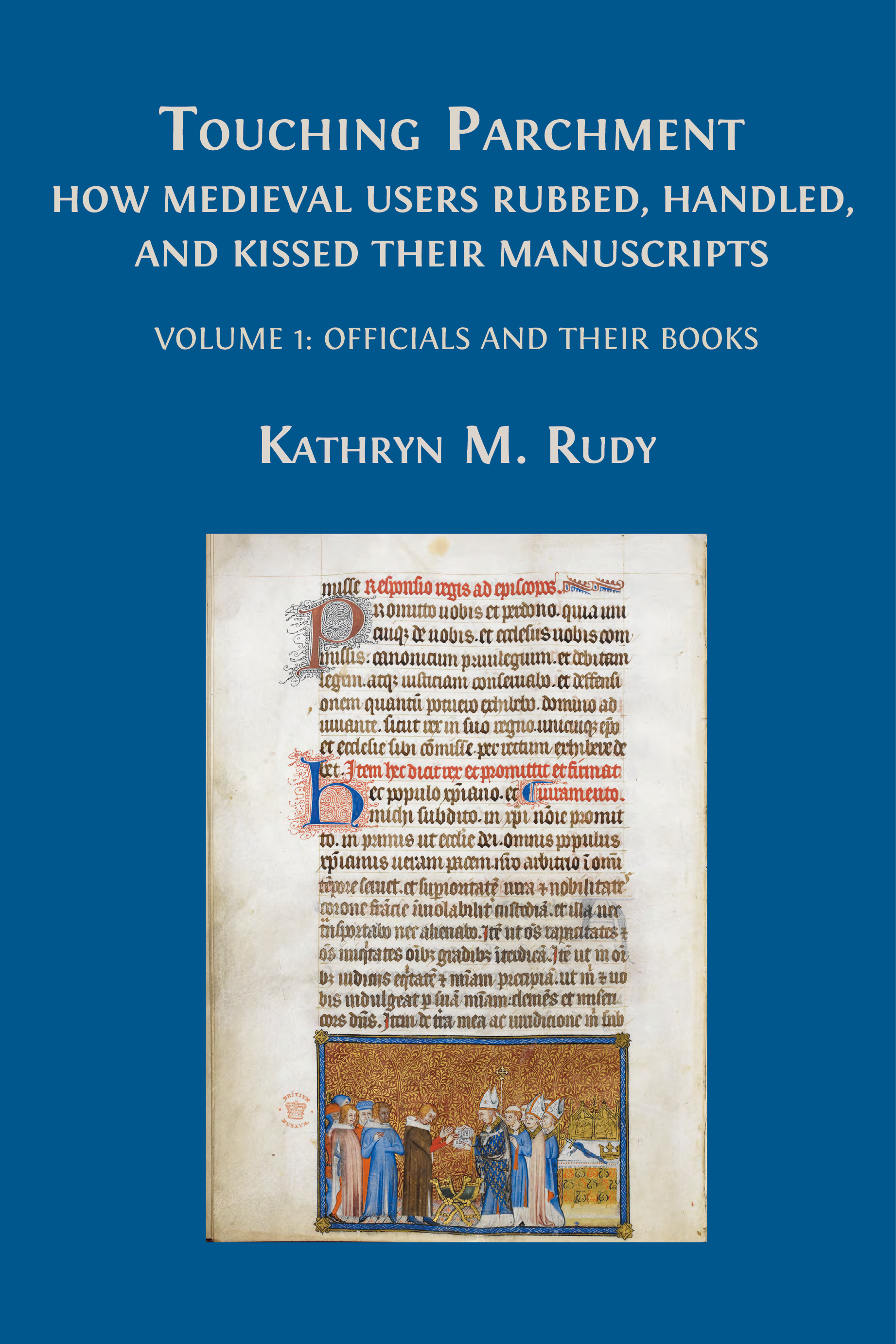

© 2023 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0337.05

Recording laws and swearing oaths helped to uphold promises and to minimize future uncertainty. Legal agreements between rulers and the oaths that bound them had, by the later Middle Ages, passed into all manner of interpersonal connections—rituals involving words, gestures, and props operated to assert oaths and guarantee promises. As discussed in the previous chapter, a new trend emerged, which saw Gospel manuscripts replace relics as the props used in oath-swearing. This chapter reveals a further trend: an expansion of oath-swearing that relied upon new legal books and new books of privileges and statutes to serve the administrative needs of an ever-broader array of civic organizations. Where oath-swearing on books might once have been the purview of emperors and kings alone, by the late Middle Ages the literate public had also adopted the practice. These new legal books began to include excerpts from the Gospels so that oaths could be sworn on the legal manuscripts themselves, as if people were making a binding gesture not just with the Gospels, but also with the new forms of stabilizing civic law.

Medieval cities in Northern Europe that had a Jewish population kept a separate oath for them, because it would make no sense for Jews to swear on the Gospels.1 Instead, Jews were compelled to swear on the Hebrew Bible while reading a vivid statement about the punishments that would befall them should they lie under oath. Sometimes they had to endure the added humiliation of touching the judge’s staff or standing on the skin of a freshly killed animal. The earliest surviving example, the Erfurt Oath, made around 1200, is a short text on a small piece of parchment inscribed with gold initials and with its wax seal attached, to give the document official authority. Its text comprises a statement for Jews to read ceremonially before making statements in court (Fig. 60). Medieval oaths for Jews typically invoke the name of God, recall miraculous events that testify to God’s omnipotence, and curse perjury.2 Of course the Erfurt Oath has no signs of repeated wear, for it was not touched ritualistically; only an accompanying Pentateuch would have been touched. This treatment underscored how Christians alone were permitted—and indeed required—to touch the most powerful symbols in the dominant culture: images of Jesus and Mary, which found their way into a new class of manuscripts for civic law.

Fig. 60 Erfurt Jewish Oath, parchment and a wax seal, ca. 1200, Erfut. Erfurt, Old Synagogue. Photo kindly supplied by the Municipal Archive Erfurt, 2006

I. Last Judgment Imagery for Reinforcing Obligation

In the early thirteenth century, Eike von Repgow compiled customary law in the Holy Roman Empire. He translated his sources from Latin into German and gathered it into the Sachsenspiegel, or “Saxon mirror,” which began circulating by 1235. Those in certain Germanic-speaking lands, from the Netherlands to Ukraine, translated it into local vernaculars and adopted it as the main written legal code.3 Considered the fountainhead of German jurisprudence, the Sachsenspiegel operated in some places until the nineteenth century. The text, which survives in some 400 manuscript copies, was instrumental in codifying property law, inheritance, and neighborly relations, as it offered rules for preventing conflict and resolving disputes by addressing potentially frictive items, such as the quality of fences, where to build ovens and toilets, how to prevent water run-off, and how to position windows to preserve neighbors’ privacy. For Eike von Repgow, good fences made good neighbors. Eike’s book promoted rituals around making oaths and keeping promises, but how those promises were sealed shifted over time.

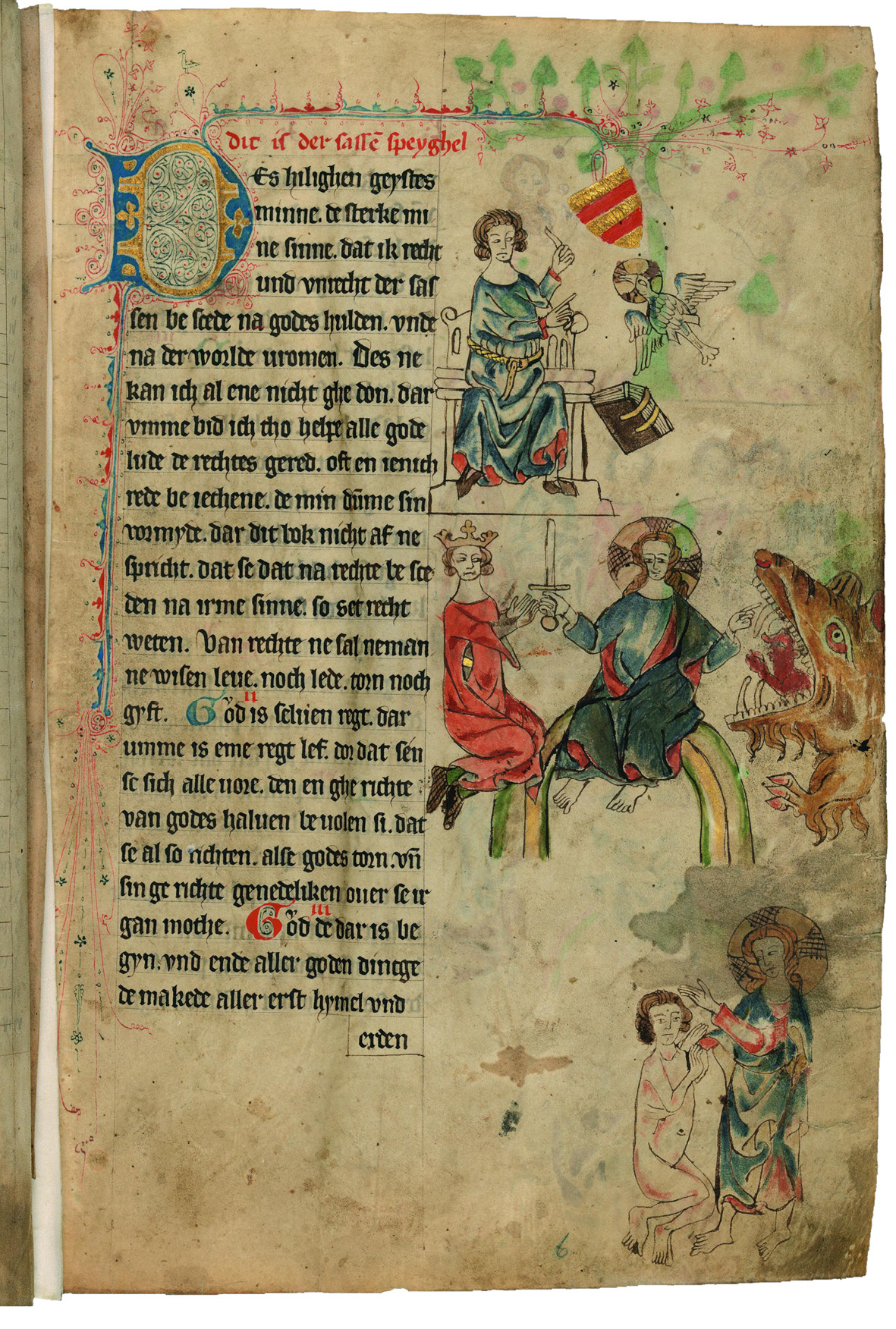

Of the roughly 400 surviving manuscript copies of the Sachsenspiegel, only four extant copies, all German, contain fulsome illustrations.4 These take the form of marginal drawings which are keyed by capital letters to the texts they accompany. In the copy now in Oldenburg, dated 1336, for example, the book opens with images showing the divine origins of law that are described in the rhyming prologue: the Holy Spirit brings the law (represented as a dove clumsily delivering a tome); Christ wields the sword of justice while seated on a rainbow; and God creates Adam, to show that he is the origin of all things on heaven and earth, including law (Fig. 61).5

Fig. 61 Opening folio of the Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow, copied in 1336, Rastede (Lower Saxony). Oldenburg, Landesbibliothek, Ms. CIM I 410, fol. 6r

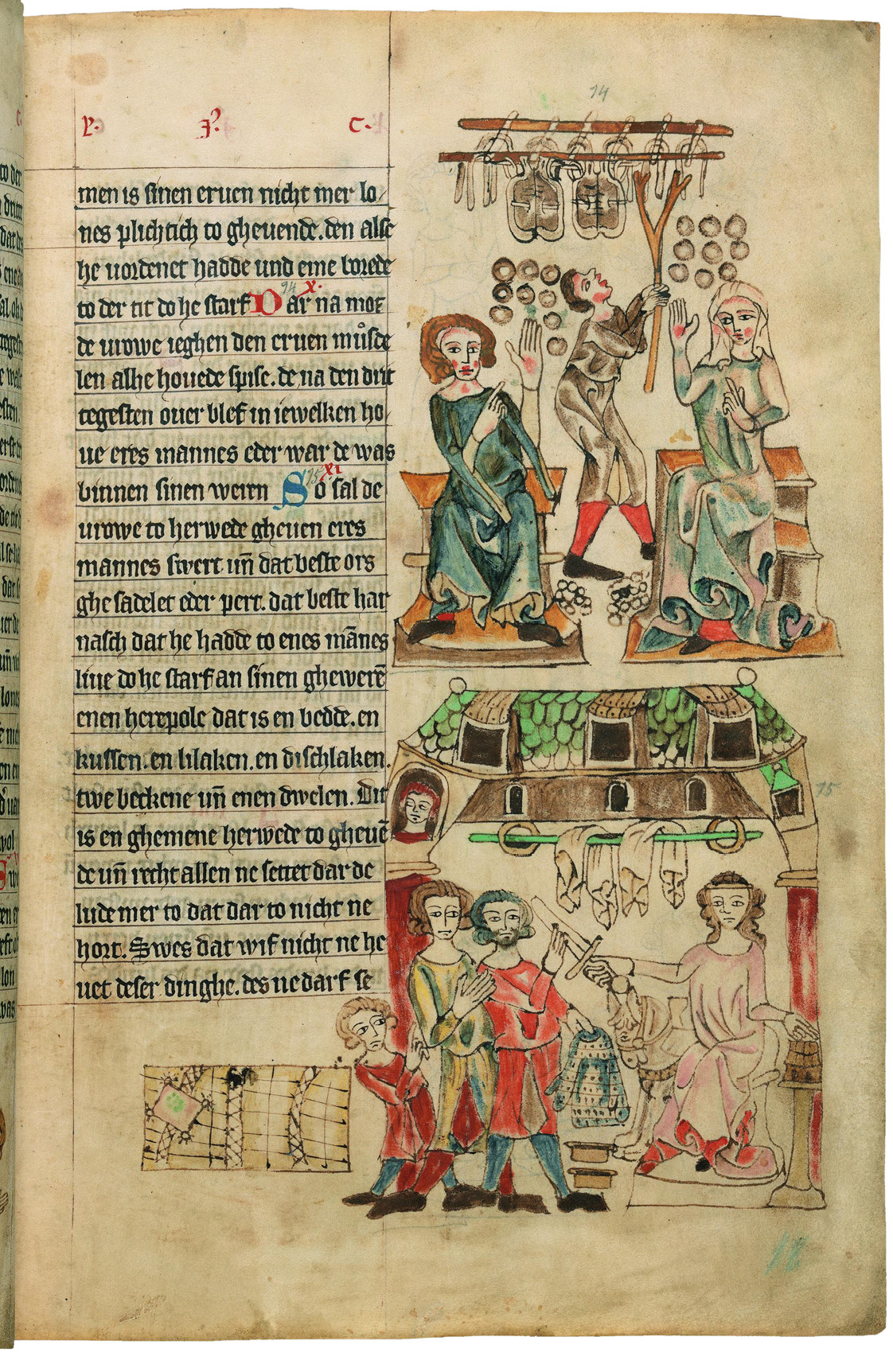

Other illustrations in the early Sachsenspiegel manuscripts usefully show the gestures and objects of jurisprudence, including court benches and reliquaries, which are rarely mentioned in the text. Swearing is an essential act for sealing oaths and proving innocence, as the terminology indicates. The term “Unschult” is used in the book to mean “the act of proving one’s innocence by means of an oath sworn on a reliquary.”6 Both women and men could take oaths. For example, a woman could take an oath to claim her morning gift (given by the husband to his new bride the morning after their wedding) when she was widowed. The Oldenburg manuscript describes this in the text. Another episode dealing with women and property shows, in the marginal imagery, the widow of a knight returning the military equipment he used until he died. As the text puts it, the equipment comprised “her husband’s sword, his best charger or riding horse with saddle, his best coat of mail and tent, and also the field gear, which consists of an army cot, a pillow, linen sheet, tablecloth, two washbasins, and a towel” (Fig. 62).7 The text goes on to explain that “The wife need not supply the articles she does not have as long as she dares to swear that she does not possess them. This is to be done separately for each and every such item. However, if it can be proven, no man or woman can cleanse himself with an oath.” The thinking in this text is that a widow would not perjure herself for a pillow. The image shows the widow taking this oath by placing her hand on a reliquary, although the reliquary is not mentioned in the text. The illuminator either copied the reliquary from his exemplar or added it because this was the conventional way of swearing oaths at the time.

Fig. 62 Folio from the Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow, copied in 1336, Rastede (Lower Saxony). Oldenburg, Landesbibliothek, Ms. CIM I 410, fol. 18r.

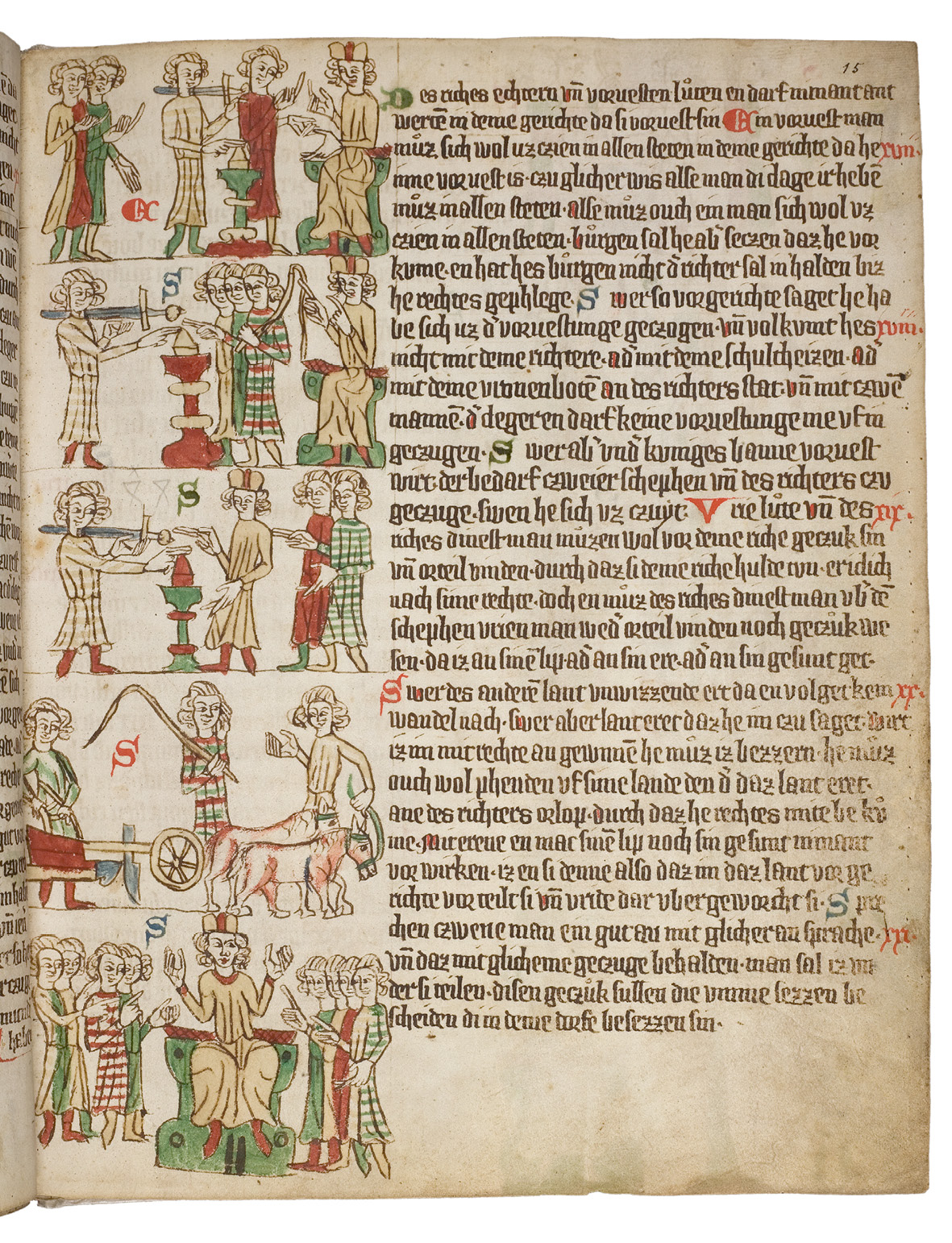

At least in the idealized world of the images accompanying the four fully illuminated early copies of the Sachsenspiegel, figures with oversized hands make elaborate oath-swearing gestures by extending two long fingers toward a golden reliquary. The Heidelberger Sachsenspiegel (Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. Germ. 164), contains numerous scenes showing people gesturing in this way. On fol. 15r, for example, figures in the first, second, and third registers are depicted placing two fingers on a reliquary situated on a pedestal (Fig. 63).8 This gesture, made with the appropriate prop and uttered with the correct words, means that their respective testimonies will carry weight. These images help to instruct the users of the new legal code on how to put it into practice.

Fig. 63 Folio from the Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow, early fourteenth century, central-eastern Germany. Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 164, fol. 15r. Reproduced under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 license

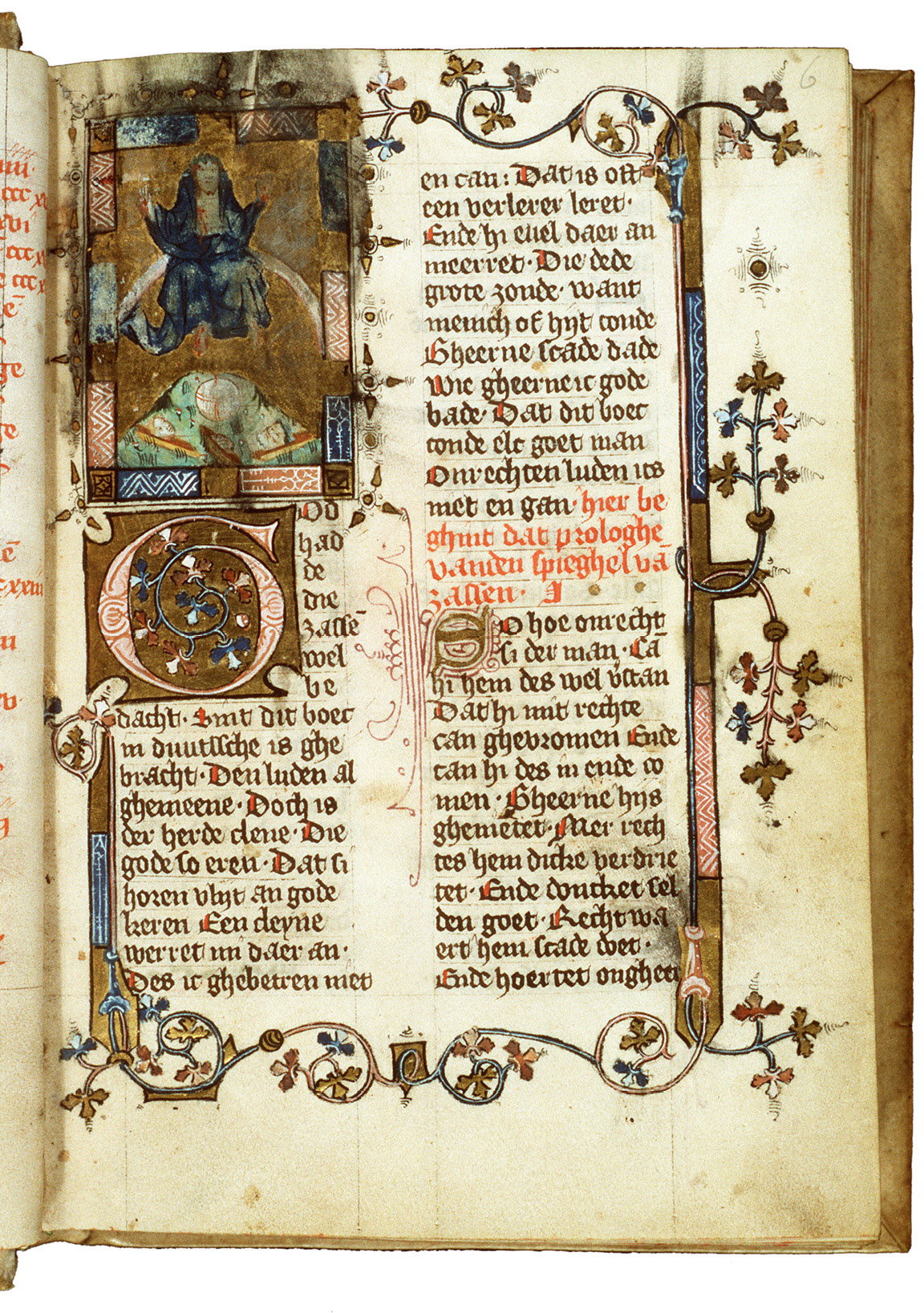

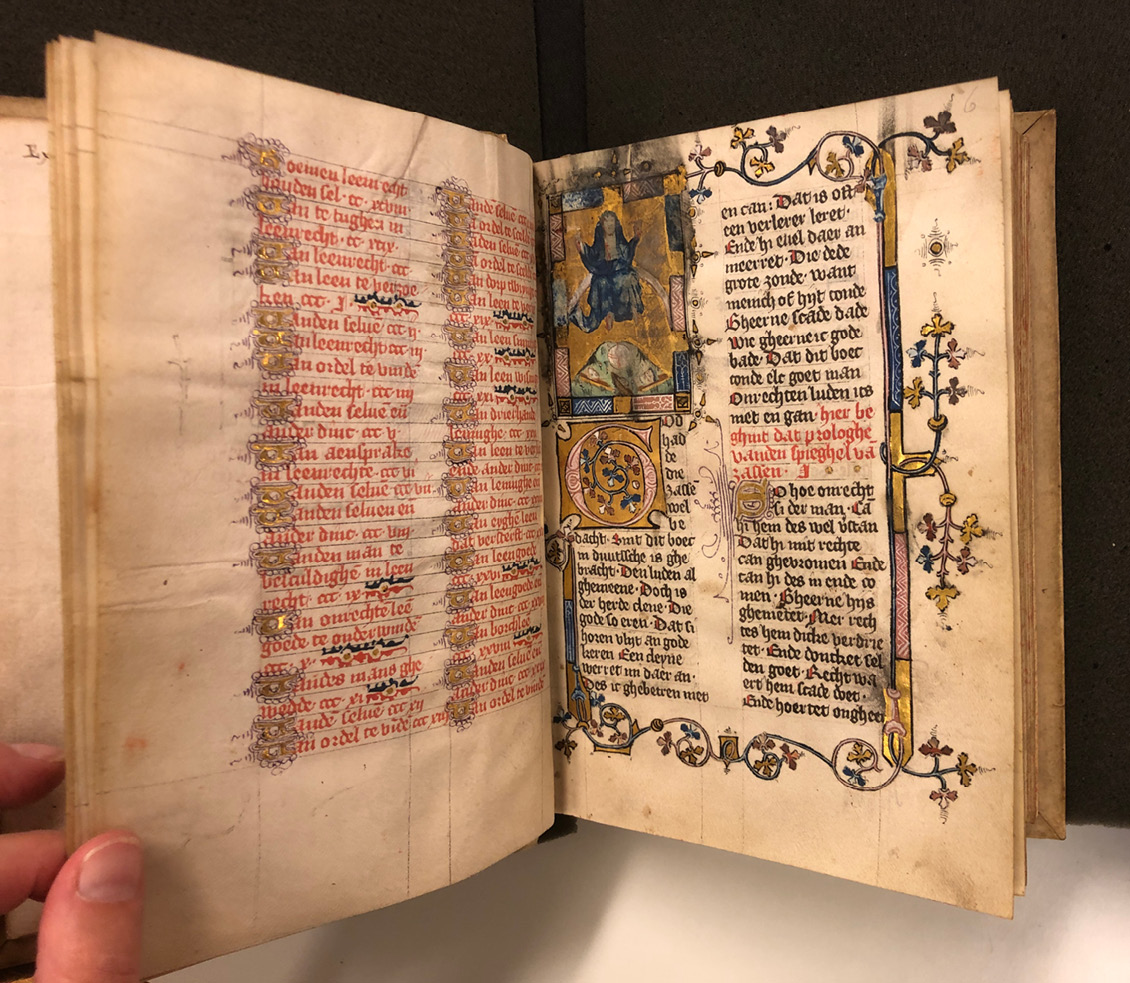

Around 1400, Duke Albert of Bavaria brought the Sachsenspiegel with him to his new throne in The Hague, from which he ruled Holland. In a copy still in The Hague, a rhyming prologue explains that this book was translated into Middle Dutch, or dietsch (HKB, Ms. 75 G 47).9 Scribes in Utrecht, the main center for manuscript production in the Northern Netherlands at that time, copied the text. In this copy, the marginal imagery disappeared, except for two images. The first of these depicts a Last Judgment, the ultimate legal event (Fig. 64). This image appears in the initial at the start of the rhyming prologue, wherein the image of Christ as judge summarizes a judicial system within a Christian context.

Fig. 64 Folio from the prologue of the Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow, translated into Middle Dutch, with a miniature depicting the Last Judgment, copied ca. 1405, Utrecht. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 75 G 47, fol. 6r

The image of the Last Judgment in the Dutch manuscript is severely damaged. Imagining the manuscript in use is easier with my amateur photograph where my fingers provide a human scale (Fig. 65). It has been used ritually and touched with what may be two different gestures. First, the image appears to have been touched with a wet finger, especially around Christ’s knee, where the blue paint defining his cloak as been liquefied and rubbed off. Court officials may have touched this initial when they read the prologue out loud, possibly as a gesture to set the tone in a legal hearing. As with other instances of prolectors touching initials, this oath-swearing gesture may also have attested to the accuracy of the pronouncement of the written words, functioning as a seal of authentication for oral delivery. Such a gesture could also draw the audience’s attention to the authority of the book from which the court official was reading.

Fig. 65 Amateur photograph showing the opening of the Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow, translated into Middle Dutch, with a miniature depicting the Last Judgment, copied ca. 1405, Utrecht. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 75 G 47, fols 5v-6r

This explanation also makes sense in the context of the manuscript, since the prologue is written in rhyme, and rhyming texts as a rule are designed to be voiced. In other words, given the rhyming nature of the prologue, it is highly likely that it would have been read aloud in public. One can imagine that a legal official read this aloud before a court procedure to prime the audience’s acceptance of the law as God-given. Considering the way in which several areas of the image seem to have been wet-touched (three panels of the decorative frame, the orb that symbolizes his rule, and the hem of his blue robe), the official may have made the sign of the cross on the image, tapping it in four places with his finger, while uttering the words “Father, Son, Holy Spirit, Amen.” I caution that this interpretation is speculative but note that a more plausible hypothesis is not forthcoming.

A second, more diffuse kind of touching is oriented toward the top of the page. A considerable amount of the pigment from the page—both paint and the ink framing the gold—have been pulled upward into the margin. This pattern of wear is consistent with a scenario in which an official proffered the book to people who reached in to touch the image, perhaps to swear an oath, and then pulled the hand out of the book, dragging some of the pigment with it. This exchange meant that the person touching the image would encounter the page upside-down, without reading the text. It is possible that when the Sachsenspiegel was copied and lost most of its images, the gestures around touching relics were also lost. Although the gesture appears numerous times in the imagery of the four manuscripts mentioned above, swearing on reliquaries does not figure much in the text. It is possible that in Holland, plaintiffs and those trying to prove their innocence swore on books—including this very legal manuscript—rather than on reliquaries. The use-wear evidence in the later copy made in The Netherlands suggests a shift from using relics as oath-swearing props to using the book itself for that purpose.

Other legal manuscripts similarly borrowed Last Judgment iconography, such as a Promptuarium iuris (“Repository of Law”) now in Graz (Fig. 66).10 The manuscript was written in two volumes, probably in Seckau. Its singular image, at the beginning of the first volume, shows Christ as Salvator Mundi seated atop a double rainbow with swords emanating from his mouth, symbolizing the justice he metes out. Christ overshadows two groups of men, the representatives of the spiritual realm under his right hand (the pope and three cardinals) and representatives of the worldly realm under his left (the emperor and magistrates). Ulrich IV von Albeck (d. 1431) was Bishop of Seckau from 1417 until his death. He both authored and commissioned the volumes.11 In the image he kneels directly under Christ, offering the book to the pope. Pope Eugenius IV had wanted to appoint Ulrich cardinal, but Ulricht died on 12 December 1431 on his way to Rome. His intestines were buried in the cathedral in Padua, and the rest of his body was returned to the cathedral in Seckau.

Fig. 66 Opening and dedicatory image of Ulrich IV von Albeck’s Promptuarium iuris, copied and illuminated in 1429. Graz, University Library, Ms 23, vol. 1, fol. 1r

As an aspirant to the spiritual administration, Ulrich IV not only wrote this book, but apparently used it, as well. Ulrich IV began composing the book in 1408 when he was working in the church at Mainz. The book consists of a summary of legal concepts from writers such as Gratian, organized by lemmata in alphabetical order. Ulrich’s signature copy does not survive, and it only survives in the fair copy now in two volumes in Graz. The first volume was copied by Marci Kaiichstain Pruteni de Osterrad from Pomerania and finised on 20 April 1429, and the second volume by Georius Salsator of Glatz and finished on 30 August 1429. Ulrich apparently split his book into two volumes and had two scribes work on it so that it would be finished faster. As Ivo Pfaff has pointed out, Ulricht apparently added several entries to the margins of the manuscript after the volumes were completed. Ulrich may have also touched the frontispiece in specific ways. The abrasion is faint, however, because he was only alive for a year and a half after the volumes were complete. The open book that Ulrich offers the pope in the image is darkened, and the figure of Ulrich has been smudged. The pope’s chest, too, seems slightly abraded. Is it possible that Ulrich enacted the dedication of his book to the pope over and over during the months before his trip to Rome to become a cardinal?

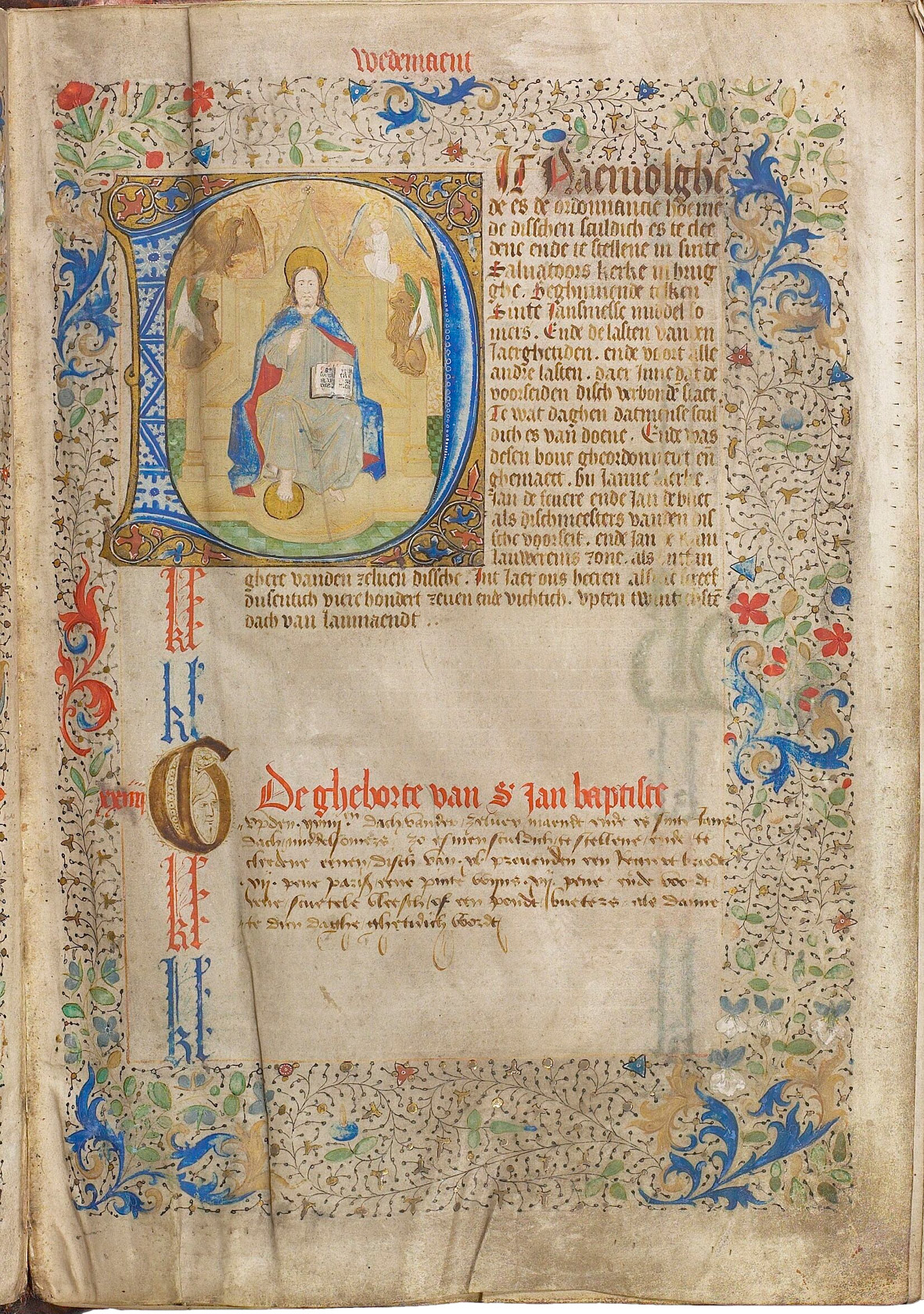

Other kinds of official books borrowed Last Judgment iconography to reinforce a sense of duty and obligation. For example, the testament of ecclesiastical stewards (register of dismeesters) for the Church of St Salvator in Bruges opens with an image of Christ in Judgment, surrounded by the four evangelists’ symbols (Fig. 67).12 The incipit announces: “The following is the schedule of who is responsible to fulfill the role of steward, to clothe and serve in the Church of St Salvator in Bruges, beginning with the Mass of St Jan in the summer, and finishing at year’s end.” Written in 1457, the text is furnished with headings for each day of the half-year, which the Master Steward would fill in. Having one’s name inscribed into one of the spaces, underneath the eye of Christ the Judge and the Evangelists, would impress the severity of one’s obligation to ensure that the Mass would be properly resourced on one’s chosen day, annually from 1457 onward. This manuscript is the inverse of a necrology, which also consists of an empty calendar designed to be filled in with the names of the dead on their death dates. For a necrology, the church is responsible for serving the congregants annually on their death dates; for the register of dismeesters, the congregants are responsible for serving the church annually on their appointed day. The image is slightly damaged, as if some of the volunteers had sealed their obligations by touching it with a wet finger.

Fig. 67 Opening folio of the register for the dismeesters (stewards) of the Cathedral of Sint-Salvator, Bruges, 1457, Bruges. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels (Belgium), cliché z011761

II. Local Government: Customary Law Books

A smoothly running civic and ecclesiastical order relied on parties swearing to binding terms by sealing them with rituals. However, in an era when church constantly seeped into state, oaths for earthly rulers and for more run-of-the mill testimonies borrowed elements from religious rituals. Books of civic rituals often contain Gospel passages and images closely related to those designed for missals, because Mass formed the central ritual of the culture, from which other rituals drew upon and adapted. Such images seem to have been implicated in overt, public bodily gestures that, like the ritual of the Canon of the Mass, depended on making physical contact with the image, even at the cost of destroying the image piecemeal.

In the fourteenth century, cities increasingly adopted separate, secularized legal codes, but the ceremonies nonetheless borrowed from older gestural traditions and therefore included images on which to swear. Separate legal codes also corresponded to the formation of new types of building—court houses and city halls—in which acts of jurisprudence took place, instead of being practiced in churches or under church portals. The books and the corresponding architecture marked the beginning of secular law distinctive from ecclesiastic or canon law, although it is not helpful to distinguish too sharply between sacred and secular. In Germanic lands, the new books were largely versions of the Sachsenspiegel, and in French-speaking lands, versions of coutumes or coutumiers (custom books). Written in the vernacular, they contained laws and legal examples, organized by theme.13 They became the basis of legal rights and obligations, and marked a turn away from despotism and toward universal justice. Whereas previously, justice had been meted out in churches, sometimes under an image depicting Christ’s Last Judgment, in the late Middle Ages, justice increasingly came to be practiced in separate courthouses, although these, too, sometimes brandished images of the Last Judgment or scenes of judgment drawn from antiquity.14 Their architectural settings, either a town hall or a church portal, imply a public audience for the book-centered ceremonies. The size of the space provides a clue as to the size of the audience, but in any setting, the gestures involving quite large books would have the effect of amplifying the gestures and their visibility to the gathered audience.

Coutumiers

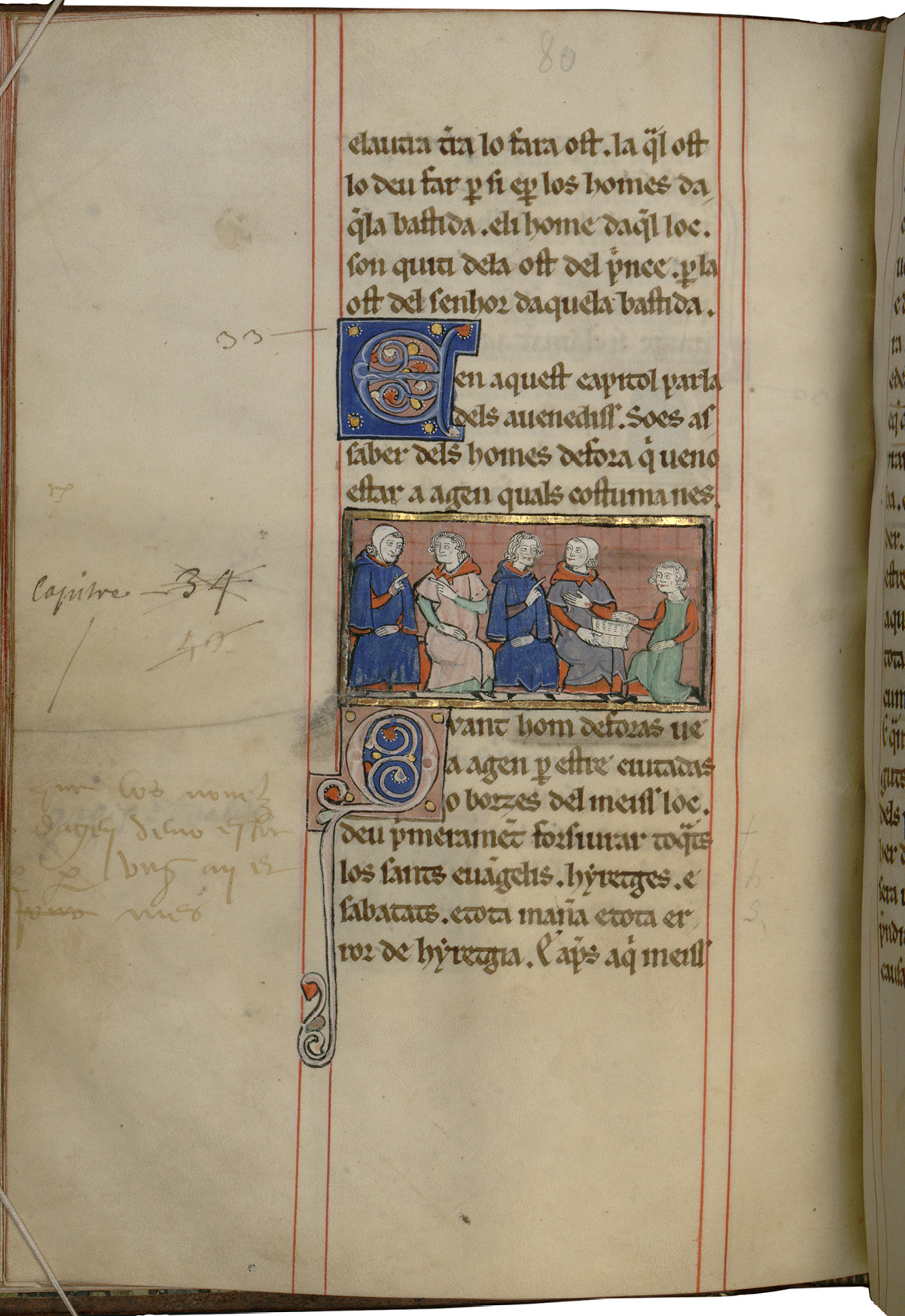

In the thirteenth century, French towns began to collect their legal codes and write them into coutumiers.15 These included prescriptive laws and oaths to swear. Several of these books survive and one early example, which dates from the thirteenth or early fourteenth century (Agen, Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42), contains the customary laws practiced in the southern French town of Agen, with frequent references to how to use this very book. Although several close copies of the manuscript survive, only the Agen exemplar is illustrated, with historiated initials that mostly depict occupations, and with column-wide miniatures of men and women undergoing judicial procedures and legal ceremonies.16 These differ altogether from the images in the Sachsenspiegel. For example, one miniature introducing a text about adultery shows the punishment of an adulterous couple: they are tied together and led through the streets behind a parade of trumpeters (Fol. 39v). Ron Akehurst has discussed the Agen manuscript and analyzed its imagery from the perspective of a social historian, offering a basic description of the vignettes and remarking on issues of class, gender, and clothing, but not on the physical use of the book.17

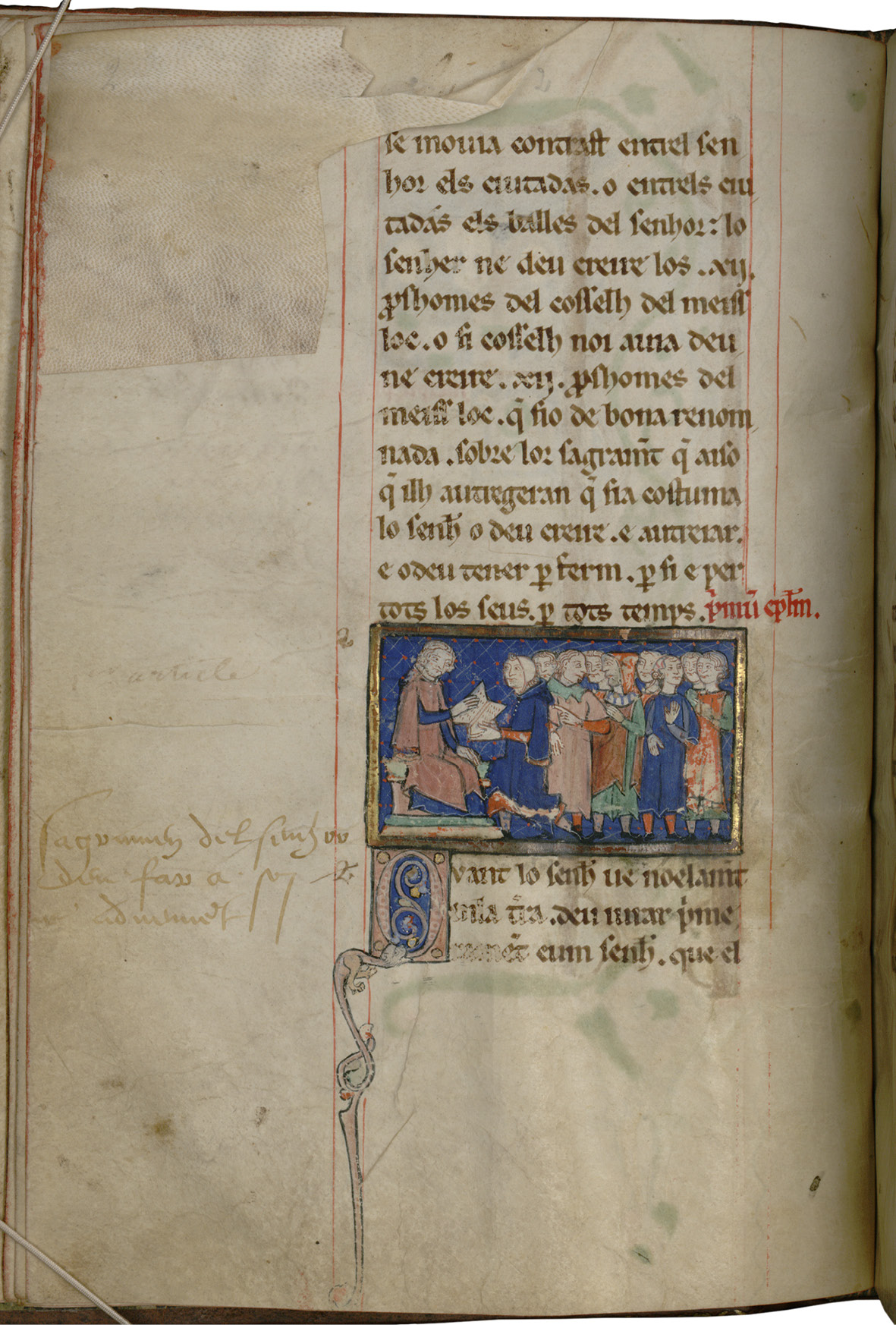

Four of the miniatures in the Agen coutumier show people taking oaths on a book. The first of these intra-textual miniatures depicts a swearing ceremony, at which a lord, seated before a standing crowd, places his hands on a book (Fig. 68). According to the text, first the lord swears on the Gospels to the citizens, then the citizens swear to the lord. Such oaths of allegiance, which draw upon lord-vassal oaths discussed earlier, formed part of the social glue in late medieval France.

Fig. 68 Swearing ceremony, with a lord seated before standing crowd. From the Livre des statuts et coutumes de la ville d’Agen, ca. 1300. Agen Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42, fol. 14v.

One of the other miniatures in Agen Ms. 42 depicts someone swearing on a book in the presence of council members (Fol. 40v). This relates to the next miniature, which shows a lawsuit taking place before the council, therefore suggesting that swearing such an oath was a prerequisite to giving testimony. A chapter dedicated to the subject of newcomers reiterates the iconography of touching the book: it shows a recent arrival swearing his allegiance to Agen (fol. 53v; Fig. 69). These figures are therefore demonstrating a physical context for a coutumier, or at least for one containing the Gospels. Although it is dangerous to treat medieval miniatures—which are stylized, selective, based on models, and designed in part to enhance the texts they accompany—as documentary evidence for medieval reality, in this case other evidence confirms that judicial books were indeed used in ceremonies such as those pictured. The entire book is designed to demonstrate, through words and images, how justice should be practiced.

Fig. 69 Newcomer swearing on a book. From the Livre des statuts et coutumes de la ville d’Agen, ca. 1300. Agen Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42, fol. 53v.

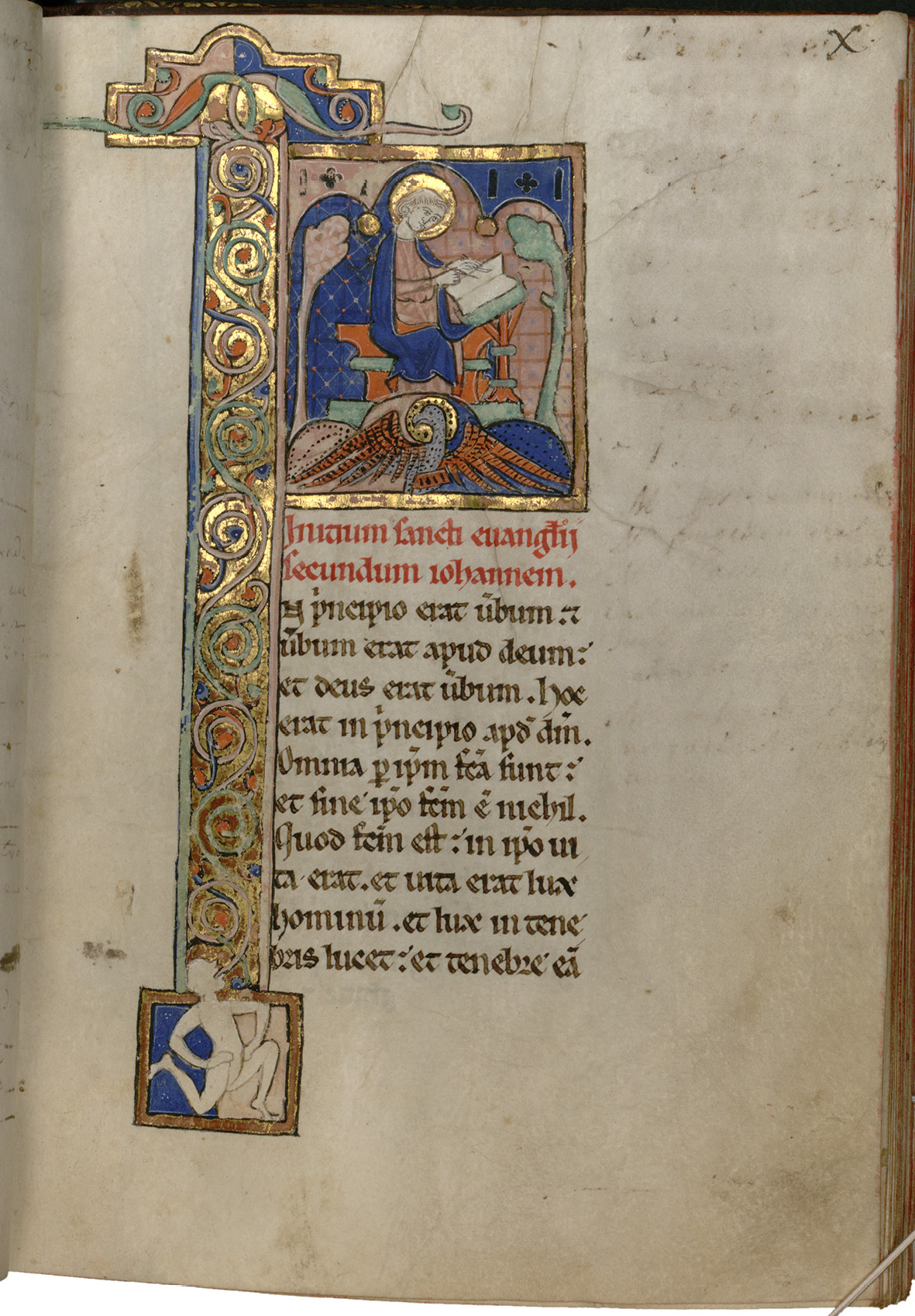

Patterns of wear near the beginning of the manuscript reveal that many people used the Agen manuscript to swear oaths. First, it contains the incipits of the four books of the Gospels, each introduced by a historiated initial (Fig. 70). These clearly refer to the Gospel books discussed earlier, which were an essential element in oath-swearing in the early Middle Ages. Old conventions, such as including evangelists’ portraits and texts from the Gospels, lent authority to the legal book and created a bond with tradition. Although their presence may have helped to give credence to the new vernacular legal code in the body of the book, the Evangelists’ pages were clearly not used extensively, as their still-clean state attests.

Fig. 70 Incipit of the Gospel of John. From the Livre des statuts et coutumes de la ville d’Agen, ca. 1300. Agen Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42, fol. 10r.

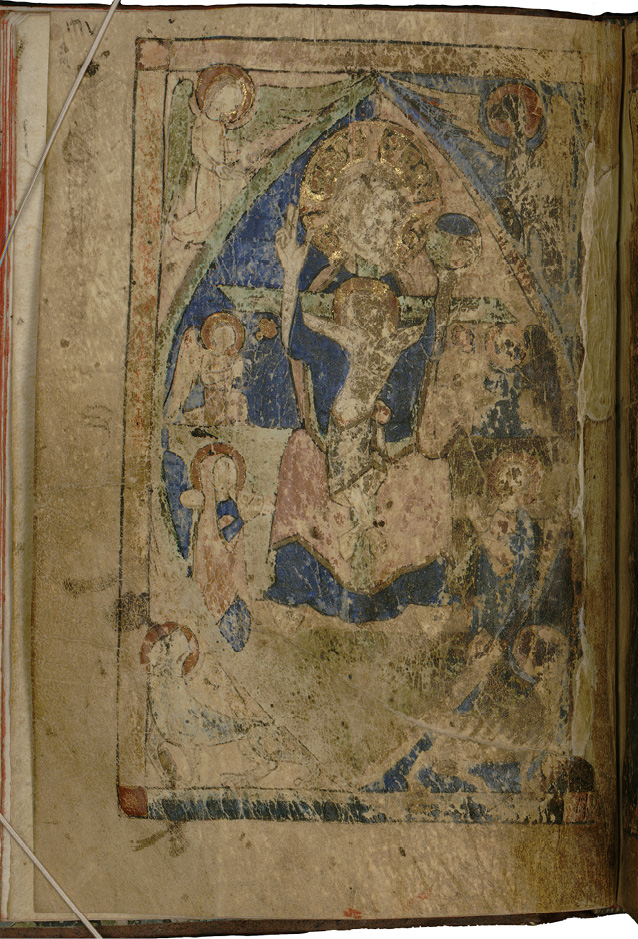

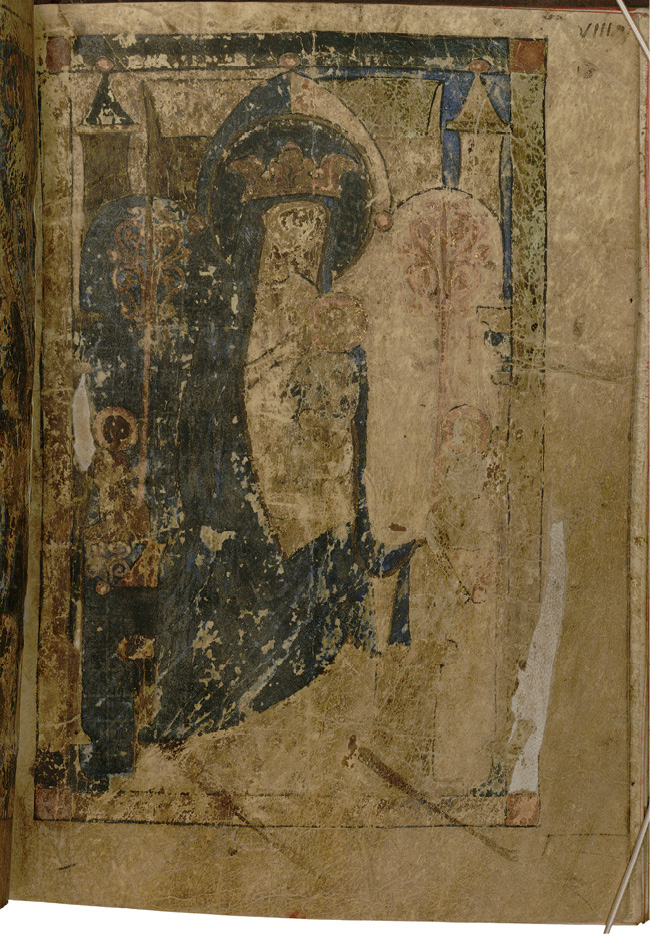

Users of this coutumier swore their oaths not on the Evangelist portraits but on a much larger target—an enormous two-page spread which prefaces the Gospel readings (Fig. 71). The full-page images were painted on a separate bifolium. These images are now so thoroughly worn that they are difficult to make out, but scrutiny reveals, on the left side of the gutter, an image of the Throne of Mercy in a mandorla, flanked by Mary, John, and angels, with the Evangelists’ symbols in the corners. On the right side, the Virgin in blue, her crowned head in front of a mandorla, holds the Christ Child, flanked by two angels. She appears between two narrow towers, possibly suggesting that she is the Portal of Paradise, one of her guises.

Fig. 71 Opening bifolio, with the Throne of Mercy in a Mandorla with the Evangelists’ Symbols, and the Virgin and Child Flanked by Angels, full-page miniatures in the Livre des statuts et coutumes de la ville d’Agen, ca. 1300. Agen Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42, fols 7v-8r.

Vigorous wear affirms how the book was used ceremonially: the officials who controlled the book obviously used these full-page images for swearing oaths rather than the smaller Evangelist portraits elsewhere in the manuscript. One explanation is that the two-page spread includes the imagery of the Evangelists (their symbols in the corners of the verso), of God in Majesty, of the Passion (with the Christ Crucified that God holds), of the Queen of Heaven, and the mystery of the Incarnation (on the recto). These images therefore united the most powerful symbols of love and nurturing alongside those of suffering and judgment.

Many clues on the bifolium (fols 7–8) reveal ways in which it was handled. It has been glued onto another piece of parchment for reinforcement. This was undoubtedly necessary because of the frequent hard wear that the bifolium received, akin to that in the Clermont Missal, discussed above, whose oath-swearing folios had fallen into tatters. So abused was it that dirt and wear have caused the sheets to crack. Both the top and the bottom of the page are worn and shiny, as an effect of offering the book toward the oath-swearer. Either the officiant held the top, so that the image would be oriented toward the recipient, or he held the bottom, so that the recipient touched the image upside down. The grasping pattern is therefore like that in the Clermont Missal. Oath-swearers then deliberately touched the face of God, or the body of Christ, or the face of the Virgin or any of the angels around them, both recto and verso. The Child and the area to his right have been rubbed down to the parchment. Most of the gilding on his halo, and on the decoration in the tree, has worn off. The diffuse but frequent way in which this image was touched is consistent with many people touching it once with a dry hand. Given this use-wear, it appears that the judge held out the book to be touched: in fact, several of the ceremonies depicted in the manuscript, as discussed earlier, confirm that it was handled in this way.

Rood Privilegeboek

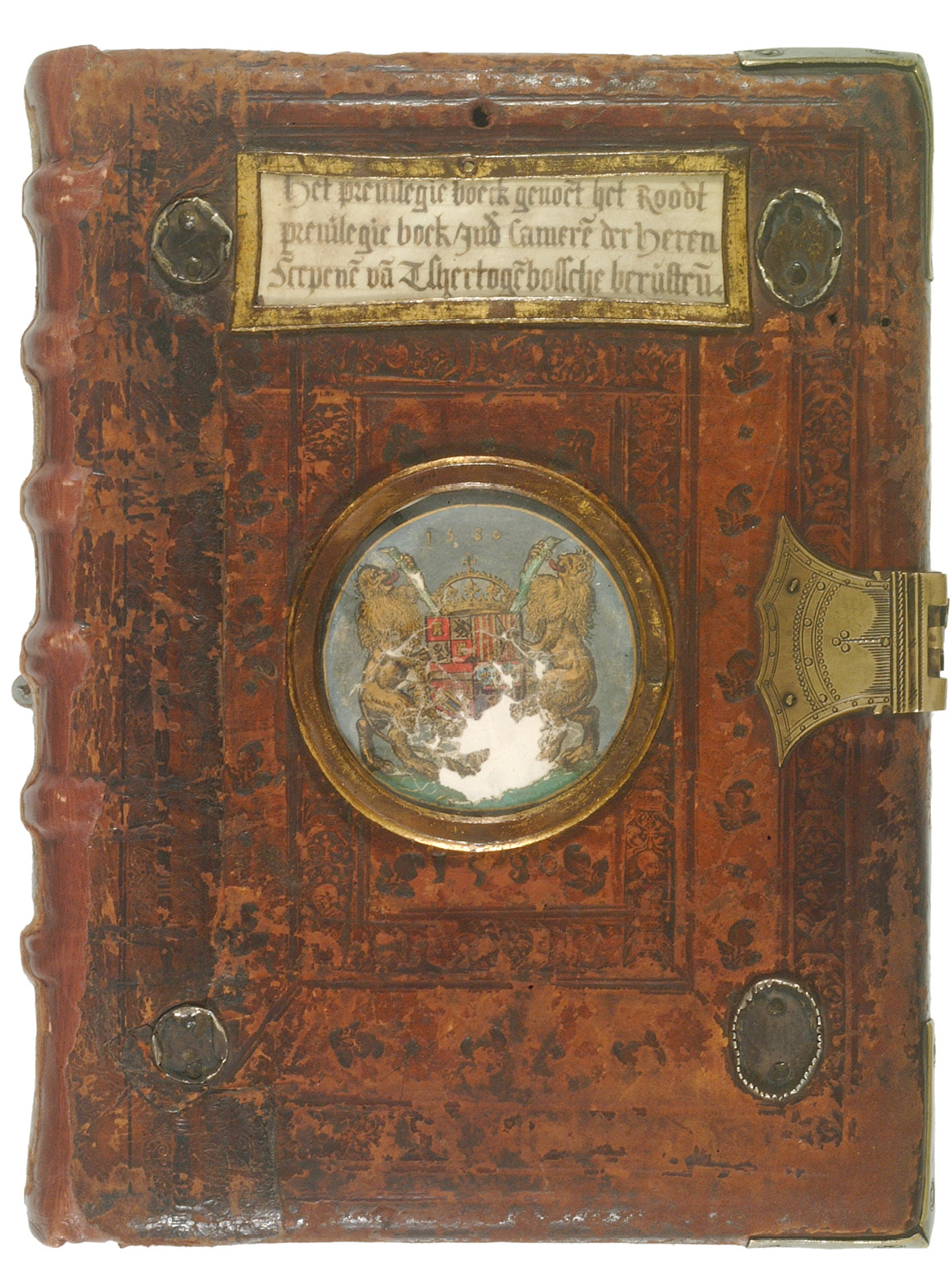

After ca. 1300 many cities wrote customs books, not only in France but throughout Europe. Only a few of these survive, perhaps because they were housed in civic buildings rather than libraries, and therefore did not follow the established routes for groups of manuscripts that were later swept into national libraries for preservation. The customs book in ’s-Hertogenbosch is still in the place for which it was written.18 Written in various campaigns from ca. 1430 until the late sixteenth century, the manuscript received its current red binding stamped with the date 1580 (Fig. 72). At the center of the front cover, a medallion brandishes the arms of Philip II, King of Hapsburg Spain (r. 1556–1598), below a titular label behind protective horn, which indicates “Dit privilegieboeck genoemt het roode previlegieboeck, inder cameren der Heren Scepenen van Tshertogenbossche berusten” (This privilege book called the “Red Privilege Book” is kept in the chambers of the Lord Aldermen of ’s-Hertogenbosch).19 Ceremonies that involved this manuscript were conducted in that room. A chain connected the book to a lectern there, as a hole at the top of the binding testifies. Metal settings in the front cover, now empty, once held jewels that would have made the book’s ceremonial gravitas visible even from a distance, like that of a ceremonial Gospel manuscript in a jeweled binding.

Fig. 72 Front cover dated 1580, Roodt Privilegieboeck. ’s-Hertogenbosch, Stadsarchief, oudarchief inv. nr A 525.

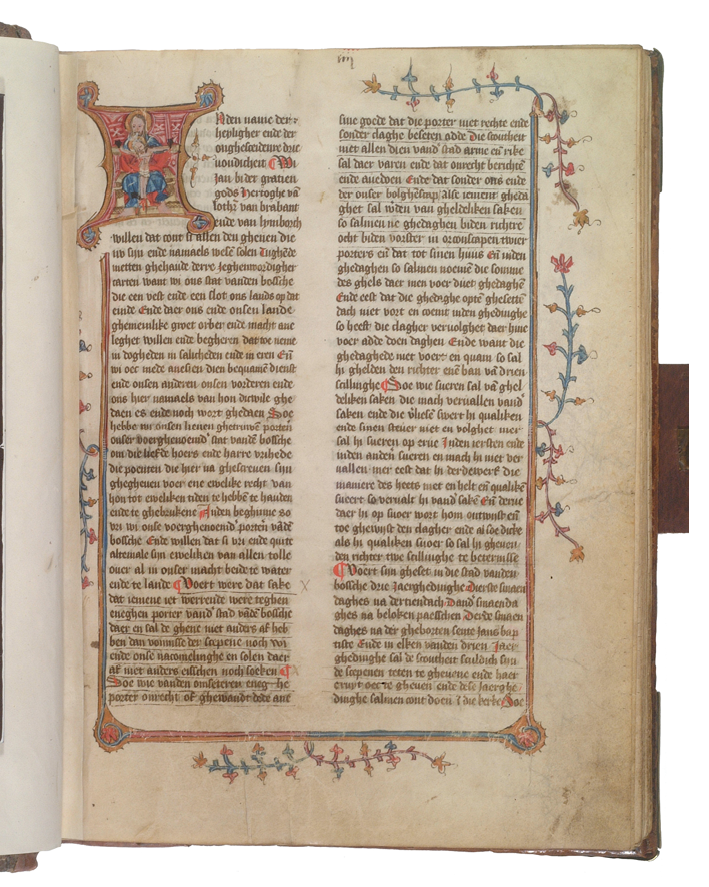

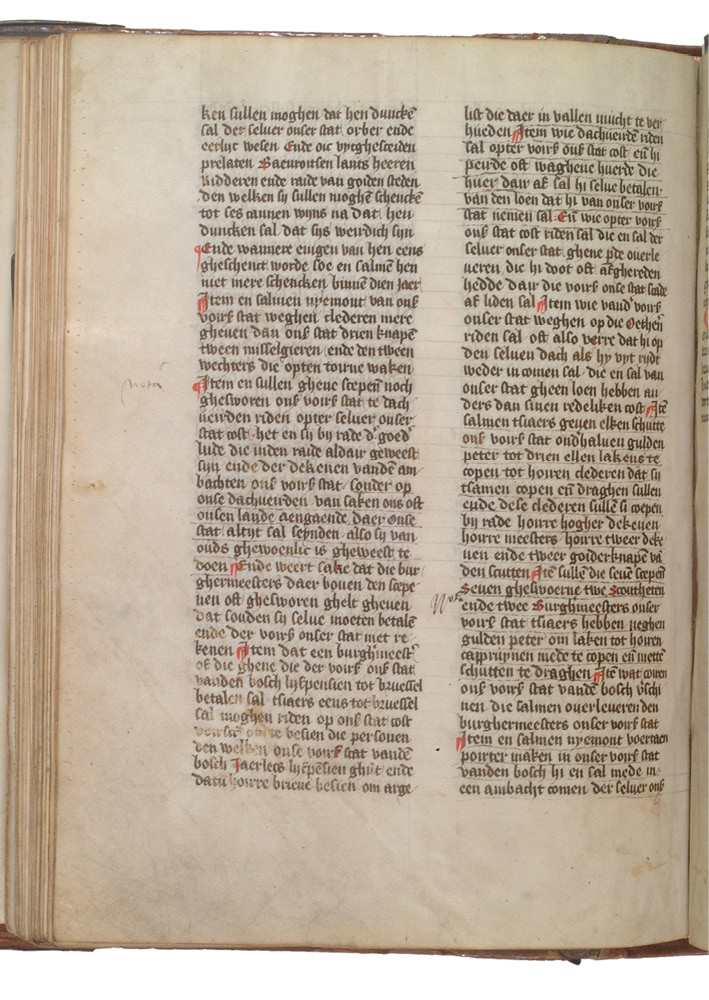

The manuscript contains copies of charters and other texts, plus some images, discussed below. Charters are formally recognized legal acts and privileges. Those for ’s-Hertogenbosch were granted by successive dukes of Brabant, beginning in 1191 with the foundation of the city. Fols 1–99 were written in one hand on parchment and were copied to consolidate all the various charters pertaining to ’s-Hertogenbosch through 1427. These texts were probably copied shortly after 1430, when Philip of Saint-Pol, the last Duke of Brabant, died. The Burgundian dukes who replaced him, beginning with Philip the Good, ruled from Brussels and tried to impose new regulations and taxes. The citizens of ’s-Hertogenbosch reacted by copying their founding documents and charters to try to revert to the agreements made by the previous, less oppressive government.

Fols 100–21, also on parchment, were added in the fifteenth century by a different hand, and fols 122–204, on smaller paper quires, were added piecemeal until ca. 1560. Of the privileges copied into the manuscript, 84 of them appear in their original versions elsewhere in the archive, and 63 survive only as copies in the Rood Privilegeboek. The privileges range in scale from the local (an agreement in 1485 by Simon van Gheel, the owner of watermills outside Rosmalen, to maintain the bridge by the watermills, fol. 208v) to the inter-regional (a peace agreement in 1390 between William, Duke of Gelderland and Johanna, Duchess of Luxembourg, fol. 73v).20 Technically, the manuscript is a cartulary, since it contains transcriptions of privileges and laws, but its function is broader than most cartularies because the volume itself represented legal authority and served as a prop in ceremonies.

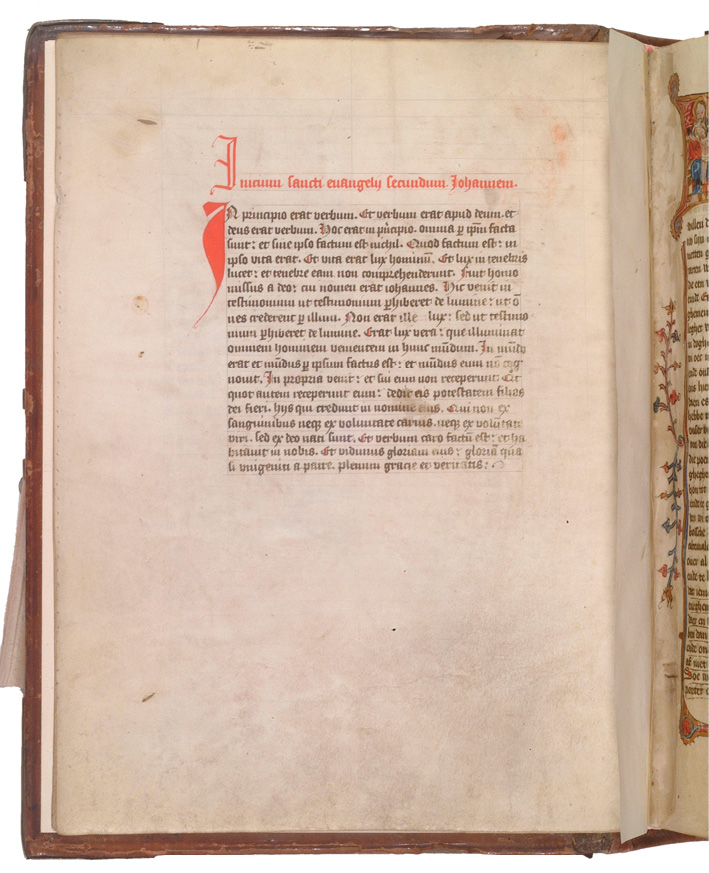

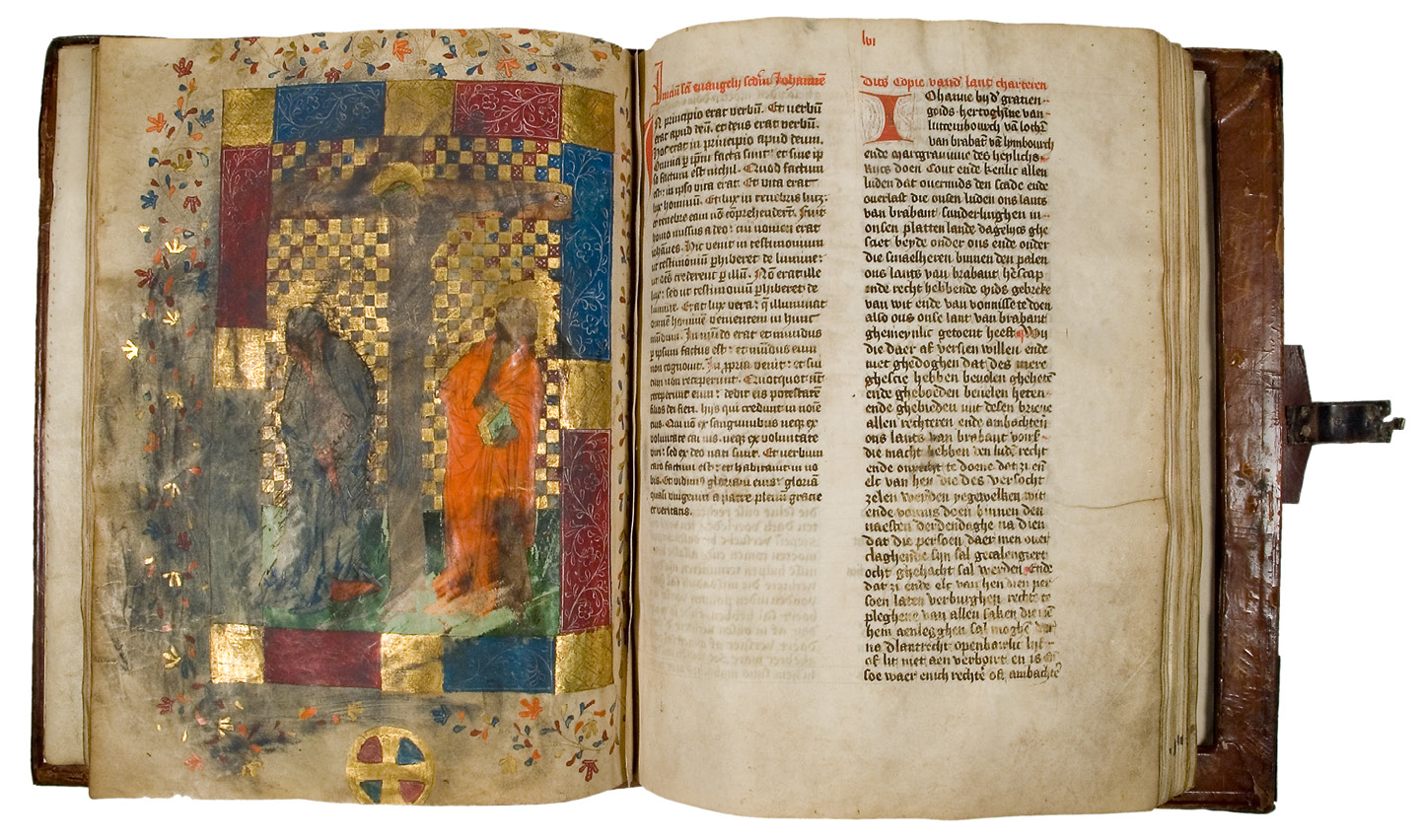

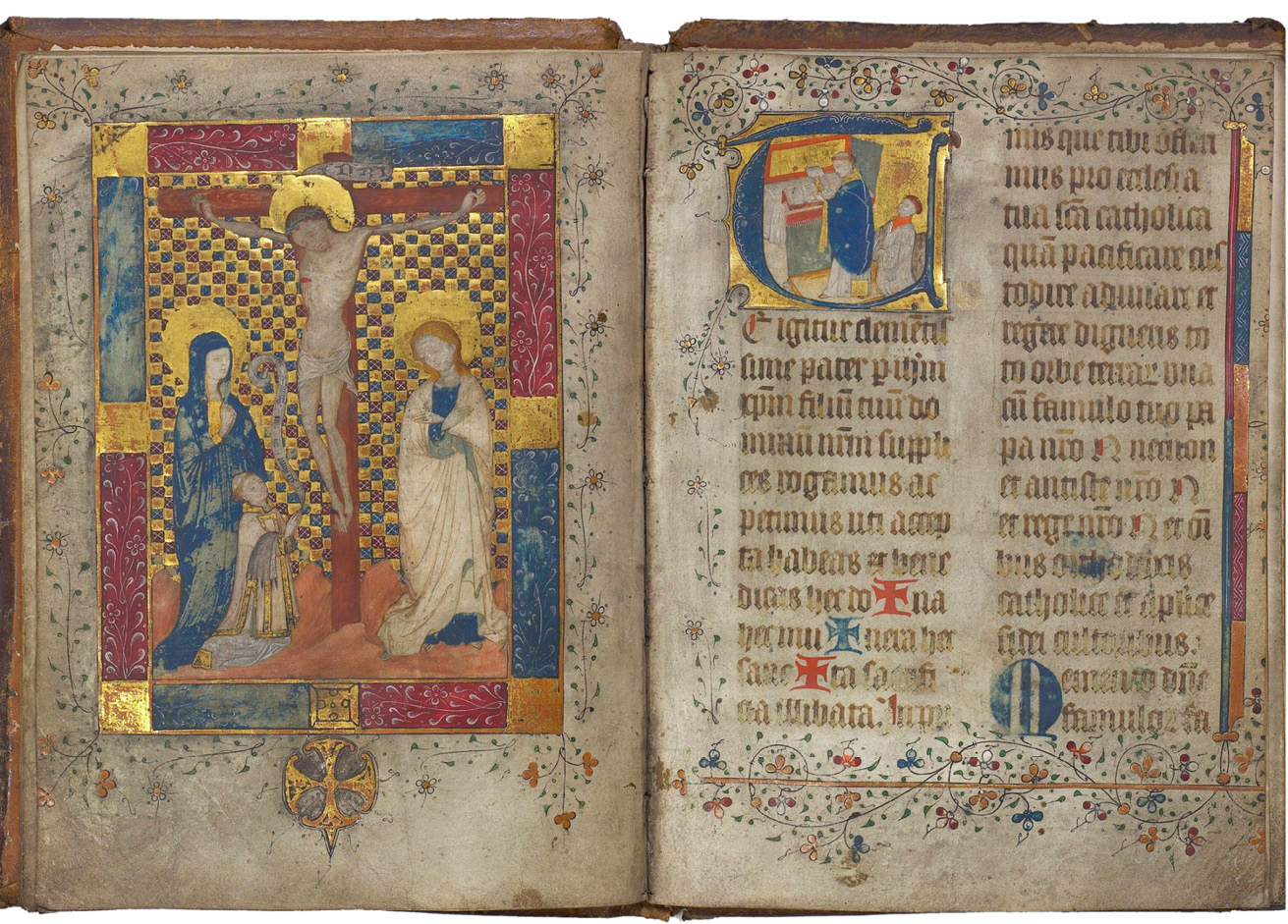

The Rood Privilegeboek draws upon structures for establishing authority from both the missal and the Gospel. It opens with the “In Principio” text, which may have been added as an afterthought onto the otherwise blank page prefacing the colorful opening (Fig. 73). Perhaps its placement at the beginning of the manuscript helps to authenticate the rest of the contents of the book. Like the Agen and other related manuscripts, it has one large miniature for swearing, in this case, a full-page crucifixion (Fig. 74).21 The image, with its diaper background, resembles in style and execution a Canon plate in a missal made ca. 1425–1450 in Utrecht (Fig. 75).22 The Crucifixion in the Rood Privilegeboek likewise dates to this period and was probably inserted into the manuscript in the 1430s when the first group of charters was copied. In other words, it forms part of the apparatus for establishing the authority of the city’s pre-1430 laws and privileges.

Fig. 73 Opening in the Roodt Privilegieboeck, with the beginning of the Book of John, and the beginning of the charter. ’s-Hertogenbosch, Stadsarchief, oudarchief inv. nr A 525, fols iii (verso) – iiii (recto).

Fig. 74 Full-page miniature depicting Christ crucified between Mary and John bound into the book of civic statutes for the city of ’s-Hertogenbosch, called the Roodt Privilegieboeck, ca. 1430. ’s-Hertogenbosch, Stadsarchief, oudarchief inv. nr A 525, fols 55v-56r

Fig. 75 Opening of a missal at the Canon, made in Utrecht and exported to Bruges. Bruges, Sint-Salvatorkathedraal, treasury. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels (Belgium), cliché Z011681

Two questions about the Crucifixion page need to be addressed: What was its original placement, given that the book was put together over several centuries, and what does the pattern of damage say about how the book functioned? The leaf with the Crucifixion is a singleton that was not expressly made for this manuscript: it is too large, and it had to be trimmed slightly to fit the book block. Was this sheet taken out of another manuscript, a missal, and swept up in the rebinding of 1580? No. The pattern of wear it has incurred differs significantly from that of a missal, such as those discussed in the previous chapter. Specifically, there is no sign of facial oil or saliva within the severely damaged leaf.

Given the parchment size difference, and the fact that it was obviously made in a different campaign of work, can one say that the Crucifixion folio was added later? Studying the previous opening provides the answer (Fig. 76). The leaf with the Crucifixion forms part of the original material, which was present when the manuscript was first inscribed. This is apparent because the back of the Crucifixion leaf is inscribed in the original hand. This means that the Crucifixion was planned, from the manuscript’s inception, in its current location.

Fig. 76 Roodt Privilegieboeck,’s-Hertogenbosch, Stadsarchief, oudarchief inv. nr A 525, fols LX verso– LX bis recto

Nevertheless, I suggest that the aldermen who made the Rood Privilegeboek instead purchased a ready-made parchment sheet with the Crucifixion, of the sort made to be inserted into missals. Since the Crucifixion was usually the only image in a missal, they were typically made separately elsewhere and integrated into the book block at the time of binding. These loose Crucifixion sheets found other homes and purposes, and one was purchased, possibly from a painter in Utrecht, to form part of the Rood Privilegeboek.

The Crucifixion image and its parchment substrate have undergone severe abrasion resulting from a particular pattern of dry-handling. The image has been touched vigorously and by many people, who each reached for a slightly different place on the image. Valentijn Paquay has shown that the members of the city government of ’s-Hertogenbosch used this manuscript to swear their oaths of office, doing so from its location chained to a lectern in the town hall. The seven aldermen each served only a one-year term, and therefore the entire college of aldermen changed annually. This event took place on 1 October. As they took their respective oaths, they placed their hands on the Canon plate in the manuscript.

Jos Koldeweij suggests that the little cross at the bottom of the folio in the Rood Privilegeboek “was intended to spare the miniature: the user of the manuscript must lay his hand on it and not on the costly … image of the Crucifixion.”23 This may be the case (and an analogous example containing statutes and regulations of the Chapter of St Servatius in Maastricht, discussed in Volume 2, likewise has a cruciform touching target). However, there is another possible explanation: as suggested earlier, illuminators manufactured such images on spec for missals. With that destination in mind, the illuminators included such crosses as osculation targets. When this folio was purchased for the Rood Privilegeboek rather than for a missal, the function of the little cross fell away. In other words, the scribe of the Rood Privilegeboek selected the Crucifixion image because it was clearly recognizable as one that activated the most dramatic moment of the Mass, but in the Rood Privilegeboek and the ceremonies in which it was used, the supernatural presence and gravitas of transubstantiation were re-deployed in a new setting. The new rituals, however, did not involve kissing.

Building on these observations, I note that the left margin is severely discolored because pigment has been pulled from the center of the image into the left boundary. This pattern suggests a scenario: when used for oath-swearing rituals, the manuscript lay open, while both an officiant and the alderman swearing the oath stood around the open book. Each alderman stood to the left of the manuscript and placed his hand on the image. The official stood at the bottom of the book, so that the text was oriented toward him. After the oath was recited, the alderman retracted his hand, leaving a leftward smear in its wake.

In addition to its role for swearing in aldermen, the manuscript may have also played a part in another ritual, involving the dukes and duchesses who ruled Brabant. Johanna of Brabant and her husband Wenceslaus of Luxembourg ratified the land charter of Brabant in 1356, and this formed the basis for law until 1792 for the Southern Netherlands. Johanna executed this during her “Blijde Inkomste” (or joyous entry) into the city in 1356, and successive rulers swore an oath to uphold this document during their respective joyous entries into the four major cities of Brabant: Antwerp, Brussels, Leuven, and ’s-Hertogenbosch. (Leuven still has a street in the middle of town called Blijde-Inkomstestraat along which the rulers would have paraded into town.) In addition to Johanna, rulers who staged joyous entries into Brabantine cities include: Jan IV (in 1415), Philip of Saint-Pol (in 1427), Philip the Good (in 1430), Charles the Bold (in 1467), Mary of Burgundy (in 1477), Philip the Handsome (in 1482), and Charles V (in 1506). Scholars, however, disagree whether they all conducted joyous entries into ’s-Hertogenbosch, but according to Jos Koldeweij, they did so, and for those entries that took place after 1430, the respective rulers swore their oaths on the Rood Privilegeboek.24 Many of the added pages in the manuscript even contain notes and details about the joyous entries, which further place the manuscript in the ambit of these formal events.

As Valentijn Paquay points out, however, the ordo indicates that rulers should swear on a Gospel manuscript, not on the Rood Privilegeboek.25 I would point out, however, the scribe has copied the incipit of the Book of John, In principio erat verbum, perhaps so that the volume could take on the role of a Gospel manuscript in oath-taking ceremonies. The Crucifixion image faces fol. 56r, which contains the incipit of the Book of John. This biblical text accompanies numerous oaths and oath-swearing plates, including the one from Agen discussed above. The text that immediately follows the beginning of John is also telling. It is a copy of the very land charter issued by Johanna in 1383, which includes a section about the rights of people who move into one of the cities of Brabant. In other words, the small amount of text from John transforms the manuscript into a “Gospel,” at least for this ceremonial purpose, while the presence of the land charter further lends the manuscript and its attendant ceremonies legitimacy.

In short, the Rood Privilegeboek strategically incorporates elements from the Gospel (John), the missal (Crucifixion), and civic law (foundational document). In fact, the manuscript has a second copy of John’s Gospel text near the beginning of the manuscript on fol. 3r. Although it is unusual to include the same text twice, it is in fact common to see John’s Gospel copied into all kinds of manuscripts that serve as witnesses. In short, the Crucifixion image fulfils a role like the full-page images in the Agen manuscript, which also prefaces a Gospel text before the legal texts begin. In the Rood Privilegeboek, this initial Gospel text and Crucifixion miniature draw on the power of Gospel manuscripts and missals, respectively, to witness the laws in what is ostensibly a civic, non-liturgical book.

Given the streaky pattern of wear on the outer margin of the Crucifixion, I propose that the oath-swearer enclosed his hand in the book while the relevant texts, copied elsewhere in the book, were being pronounced aloud by an official. If this hypothesis is correct, then the hand position may refer to another symbolic aspect of vassalage: the vassal signaled his willingness to be subject to a lord by having his hands enclosed within the lord’s hands. This gesture is intimate, in that it involves touching, and it also reiterates a symbolic hierarchy, in which the lord’s hands on the outside signal his protection of the vassal, and the vassal, with his hands on the inside of the clasp, signals his submission. In the case of the Rood Privilegeboek, the book represents authority, while the swearer demonstrates his acquiescence. The book closes onto the “vassal’s” hand, as if the book itself were the hands of the overlord.

Other medieval cities likewise produced and used books of privileges which combined aspects of the cartulary—that is, a recopied summa of all charters, laws, and privileges for a given place. To recopy the loose sheets and assemble them into one codex would give them a heft and authority appropriate to their new ceremonial role. Many of the resulting volumes are bound in red and referred to as “red books.” For example, the Rotes Stadtbuch of Hamburg from 1301 is in a bright red leather binding that not only clasps shut but has a tiny keyhole to prevent malfeasance.26 Before the table of contents, this manuscript brandishes a full-page miniature depicting Christ the Judge, standing on a rainbow, prevailing over men from different social stations. An angel unlocks the portal to paradise for the virtuous, while devils pull sinners into the maw of hell. The image seems like an intermedial translation of a church portal, wherein the carved Last Judgment presided over public terrestrial judgement below. This image, however, has not been repeatedly and systematically touched. As with all of the examples discussed in this chapter and the next one, local tradition dictated how ceremonial books would function.

The city of Cologne likewise produced a book of oaths in 1398 (an Eidbuch).27 Like the Rood Privilegeboek of ’s-Hertogenbosch, this one also has a full-page Crucifixion of the sort normally made for missals. This Canon plate is encircled by the symbols of the four evangelists, and two coats of arms. The image is not damaged, however, demonstrating that the ritual surrounding the manuscript did not involve laying hands on this image.

Use-wear analysis suggests that the ceremonial use of such legal and privilege books must have been highly localized, with specific rituals building around individual volumes. Each has a different pattern. For example, the Rotes Privilegienbuch der Stadt Regensburg contains the privileges granted to the city of Regensburg from the twelfth century until the time of copying in the fifteenth.28 Like other privilege books, this one is bound in red leather, hence its title. This manuscript is embellished with portraits of the rulers who had granted the privileges, with each portrait heading up a section of the book, performing the function of something between an author portrait and an official bust that confers value on a coin. Despite the presence of images throughout the manuscript, including a full-page Crucifixion overshadowing the kneeling pope and emperor, there is no abrasion to suggest its ceremonial use for oath swearing. How such manuscripts were handled, it would seem, depended on local tradition.

III. The University: Old Proctors’ Book

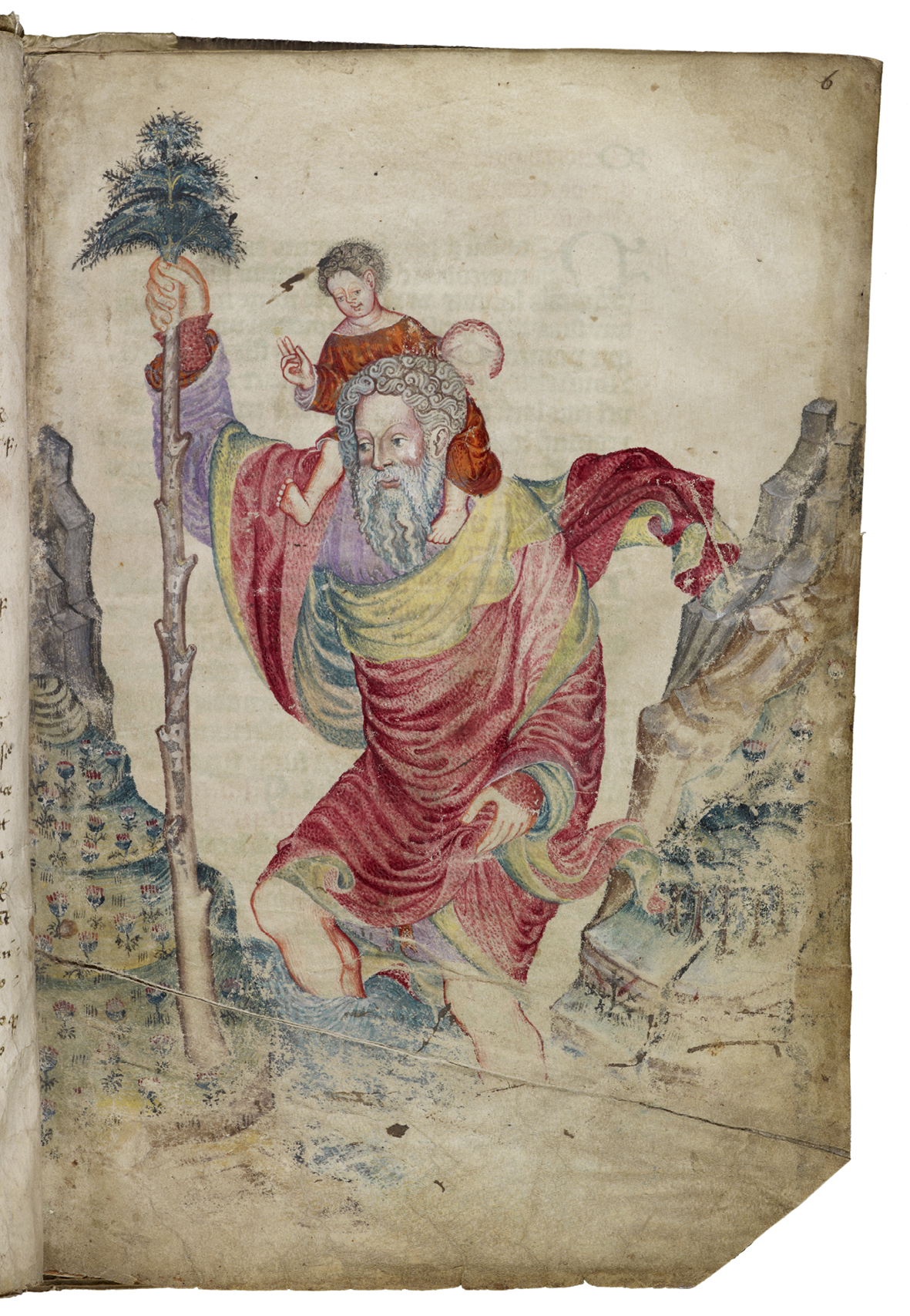

The Old Proctors’ Book of Cambridge (Statuta universitatis Cantabrigiensis) was made after 16 June 1381, when an angry mob burned the archives of Cambridge in a bonfire (Cambridge, University Archives, Collect. Admin. 3).29 As Nicholas Rogers has astutely pointed out, this event catalyzed the production of new copies of the burned books, including this book of statutes. A patent letter of Richard II dated 12 December 1384 in the original hand provides an approximate date for the manuscript’s genesis. This early date, which indicates that the proctors lost no time in commissioning the replacement volume, attests to the central role of this manuscript for running the university.30 The volume also contains a university calendar, incipits of the four Gospels, the oaths sworn by university officials, as well as oaths for civic officials who publicly acknowledged the power of the university over the borough at a ceremony called the “Magna Congregatio.” Its tattered state and its many additional oaths, penned by several scribes in different campaigns of work, reveal the manuscript’s regular use by the university proctors, the chancellor’s executive officers.

An image of St Christopher forms the first folio of a quire containing oaths to be read at the “Magna Congregatio,” which was to take place annually “when the magistri return to teaching after the feast of the Division of the Apostles [15 July],” according to the rubric on the verso of the very sheet with the saint’s image (Figs 77 and 78).31 A second image in the manuscript depicts the Virgin and Child enthroned, produced in a different campaign of work, which prefaces a separate series of oaths (Fig. 79). The leaf with the Virgin is bifoliate with a missing leaf that may have contained another image, perhaps a Crucifixion. While images of Jesus and Mary appear in other manuscripts for oath swearing, as discussed earlier, and their presence here is not surprising, the inclusion of St Christopher is unusual in this context. It may relate to his role in preventing false oaths. As Rogers points out, the Beaufort Hours contains a prayer to St Christopher in which the saint is invoked against “malas perversas machinaciones fraudulentas conspiraciones mendacia falsa testimonia occulta sive aparta consilia.” Invoking him through his image may have also helped to guard against bad and perverse machinations, fraudulent conspiracies, lies, false testimonies, and hidden or covert plans.

Fig. 77 Folio in the Old Proctors’ Book of Cambridge with an image depicting St. Christopher. Cambridge, University Archives, Collect. Admin. 3, fol. 6r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Fig. 78 Folio in the Old Proctors’ Book of Cambridge with the beginning of a series of oaths. Cambridge, University Archives, Collect. Admin. 3, fol. 6v. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Fig. 79 Folio in the Old Proctors’ Book of Cambridge with an image depicting Virgin and Child in an architectural niche. Cambridge, University Archives, Collect. Admin. 3, fol. 8r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Rogers refers to the St Christopher and Mary miniatures as “solemnizing images,” which “underline the solemnity of the oaths sworn at the ‘Magna Congregatio.’” He states that the oaths themselves were sworn on the Gospel sequences—texts that, as we have seen, are ubiquitous in oath-swearing manuscripts.32 These are inscribed in the same hand as the oaths, beginning on fol. 9v. The problem with his assertion, however, is that the folios of the Gospel texts are not worn very significantly, and they bear no witness to having been used for swearing. I think that Rogers has inverted the purposes of the texts and images: evidence from signs of wear suggest that the Gospel sequences form a “solemnizing” component to the volume, while the images were the targets for officials’ oaths. This is the inverse of Rogers’s proposal.

The patterns of wear on the images testify to their having been touched. The luminous parchment of the St Christopher leaf, with its slightly waxy finish, has a surface to which water-based paint barely adheres. Curiously, only the bottom of the image is degraded from repeated acts of handling. In particular, the stream in the foreground has been rubbed so severely that the flaked paint reveals raw parchment. Equally curiously, the numerous people who caused this cumulative wear did not touch the saint’s face. Likewise, the image of the Virgin has also been abraded at the lower third. There the parchment has buckled, as if the moisture from hands had caused the material to distort, and those distortions were pressed between the pages into permanent creases.

How did users handle this manuscript to cause this pattern of wear? That the bottom third of the image of the Virgin has been degraded indicates that those who swore their oaths stood at the bottom of the book. That the book’s users were members of the university implies that they were literate: unlike the users of the ’s-Hertogenbosch customs book, they did not need to have the oath read to them. Why did they not touch the faces of the figures? This question requires some haptic imagination. First, it is important to remember that many folios of the manuscript are now missing, and the folios may not be in their original order. It is unclear what these images originally faced. After they turned to the page containing the relevant oath and read it aloud, they did not turn back to the image page and touch it. Rather, the pattern of wear suggests that they held their hand on the image page the entire time they were reading the oath aloud, thereby touching the image and reading the text at the same time. In other words, the swearer had his hand stuck in the closed book and was touching an image that he was not actually looking at. This pattern of wear—abrasion at the bottom without targeting the face—fits that scenario: touching the image while reading the oath on a different page.

In particular, abrasion only along the bottom edge indicates that it was touched while the oath swearer was reading from a different page. Such a configuration would illuminate a fact about this codex and the mechanics of its handling: that one can interact with more than one page at a time, and that touching does not imply seeing, but rather can take the place of seeing. Touchers or readers must have done this because touching the image was essential to sealing the oath, but not every folio could be illuminated. In fact, they were taking advantage of one of the structural benefits of the codex: that one can have fingers or even entire hands in different openings at the same time. By acting in this way, they demonstrated that an image does not have to be visible to be in service of an outcome.

IV.The Inquisition: Inquisitor’s Manual

The Waldensians, a group active in ca. 1380–1410 (especially in Germany), refused to swear oaths. These Christians were followers of Peter Waldo, a rich man who gave away his possessions around 1173 and then advocated for a simple apostolic life. Waldensians took seriously the injunction in the Book of Matthew not to swear oaths. Additionally, Waldensians did not give credence to the saints, to relics, or to the Virgin Mary, and as such, they neither invoked saints nor believed in saintly intervention. They did not believe in the consecration or dedication of churches or altars, nor did they believe in the sacrality of priests’ garments, salt, holy water, or ashes. They would not use images in their devotions. Their scruples, based on close reading of scripture, vexed the Church, because the Waldensians threatened its values, beliefs, objects, and rituals. They were forerunners of the Cathars, and the Church labelled both groups heretics.

As Reima Välimäki has eloquently shown, inquisitors used manuals to root out Waldensians by questioning them about their faith and then forcing them to recant their objectionable beliefs and confirm their orthodoxy.33 Several inquisitors’ manuals survive, including one compiled in the fourteenth century in Bohemia (Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek, Cod. 177).34 This manuscript was rebound in the early fifteenth century in a red leather binding that recalls those of the oath books of ’s-Hertogenbosch and the various German cities (Fig. 80). It contains some 40 different texts related to heresy, including lists of heresies, excerpts from canon law on excommunication and absolution, relevant papal bulls, texts for interrogating Waldensians, definitions of legal terms and concepts, and a formula for them to recite in which they renounced their questionable beliefs (or asserted their orthodoxy).35

Fig. 80 Front cover of a compilation of texts about inquisition and heresy, fourteenth century. Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek (OÖLB), Cod. 177. [to cite this according to the library’s standards: Linz, AT-OOeLB, Hs.-177 (Sammelhandschrift zu Themen von Inquisition und Umgang mit Häresie, Saec. XIV). 1300.]

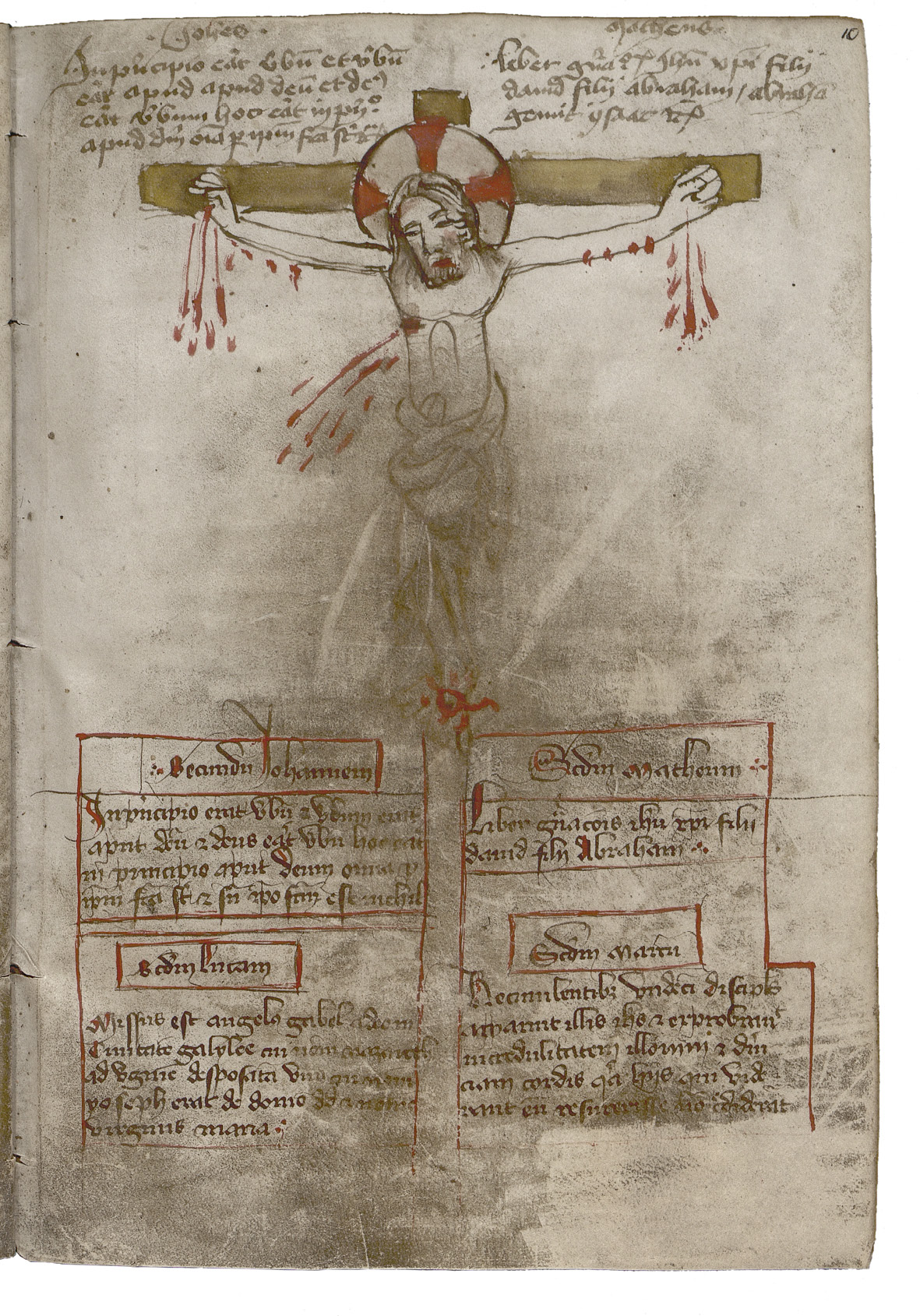

According to Välimäki, the Linz manual was owned by the inquisitor Petrus Zwicker. Signs of wear in the volume show that an inquisitor, possibly Zwicker, used the manuscript not only for its textual contents, but also as a physical prop in rituals in which those accused of heresy would abjure their heretical beliefs. These signs of wear occur in the first quire, which comprises the first ten folios of the manuscript. This section includes a table of contents (fols 1v-3v) to fols 11r-51r, which by virtue of its descriptive nature must have been made after the folios it describes. The person who compiled the table of contents overestimated how much parchment that job would require and added a full quire of 10 folios when four would have sufficed. Paleographical analysis indicates that various hands also added the other items within a few decades after the main body of the manuscript was written, as early users continually identified texts that would enhance the book’s function. Important additions in the present context are excerpts from the beginnings of the four Gospels (at the bottom of fol. 1r; Fig. 81), questionnaires to determine whether someone was a heretic (fols 4r-5r, 6r-7r), and an image depicting Christ crucified (fol. 10r, Fig. 82).36 The simple image is drawn in ink with pen and washes, highlighted in yellow watercolor, and then embellished with rubricator’s red ink to emphasize Christ’s tripartite halo and to make the blood leap from his body. This image, together with the added texts, contributes to the book’s function.

Fig. 81 Folio from a compilation of texts about inquisition and heresy, with incipits of the four Gospels. Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek (OÖLB), Cod. 177, fol. 1r.

Fig. 82 Folio from a compilation of texts about inquisition and heresy, with a drawing of Christ Crucified. Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek (OÖLB), Cod. 177, fol. 10r.

More added texts top and tail the page: above are the incipits of the Books of John and Matthew, and below the incipits of all four Gospels. Wielding the rubricator’s red ink, the scribe has framed these texts in red boxes. The same brown and red inks appear in the lower texts, their frames, and in the drawing of Christ, suggesting that the image was made by the scribe and is an extension of the texts. With the addition of these texts and images in the otherwise blank areas of the front matter, the book’s early user (or users) has turned this book from one that functioned in theory—with papal bulls, canon law, and descriptions of heresy—into one that was of immediate and urgent use in practice—with questionnaires and formulas for absolution—to a use as a prop. As one can see from the way in which fols 1r and 10r are abraded, the book itself became a tool in the inquisitor’s kit. One explanation for these features stands out.

Early in the book’s career, an inquisitor copied the Gospel incipits onto the bottom of the first folio and required accused heretics to touch the text while swearing to their orthodoxy. The added texts would have functioned as an abbreviated Gospel manuscript and would have meant that the inquisitor would have only had to carry his work-a-day manual, and not a separate oath-swearing Gospel manuscript. Shortly thereafter, he or another inquisitor sought to expand the oath-taking apparatus in the manual by filling a blank folio with an image of the Crucifixion. There was extra space in the first quire, for the reasons discussed earlier. The expander did not add a gilded Crucifixion image like those in oath-swearing books (Eidbücher, discussed above), for several reasons. Such a small manual (only 200 x 135–140 mm) would not have accommodated the kind of Canon plate designed for missals and which were available as loose sheets. Given the less exulted context of an inquisition to try a heretic, the book would not have needed a costly gilded image anyway: the scribe’s drawing would have sufficed. Recopying the Gospel incipits onto the page would have brought the abbreviated Gospel onto the active surface that the accused touched. The abraded areas on fol. 10r stretch from Christ’s torso and legs where people reached in confidently and touched the image, to the entire area of the framed Gospel texts, including the very lower border, where people have only ventured a finger or two onto the parchment.

By compelling Waldensian heretics to recant their heretical beliefs while placing their hand on the image, the heretics ipso facto demonstrated their embrace of multiple mainstream, anti-Waldensian beliefs: swearing oaths, doing so on the Gospels, acknowledging the power of the Gospels, and of images, including that of Christ Crucified, and even swearing on a page with the incipit from the Book of Matthew, which as every Waldensian would have known, proscribes swearing. That the inquisitor specifically recopied the incipit from Matthew above the Crucifixion drawing reinforces the subjugation of the accused Waldensian. Through their small, possibly coerced, ritual words and actions, the accused refuted heresy with both his mouth and his body, while the inquisitor drew upon both the texts in the little manual and the physical book itself. Gestures for acceding to the civic legal agreements were adjusted for a related purpose: to demonstrate one’s membership to a group.

1 For Jews and oath-taking, see Mann, “Oaths and Vows in the Synoptic Gospels,” pp. 260–74; and Guido Kisch, “A Fourteenth-Century Jewry Oath of South Germany,” Speculum, 15.3 (1940), pp. 331–37.

2 Christine Magin, “So dir Gott helfe: Der Erfurter Judeneid im historischen Kontext,” Erfurter Schriften zur Jüdischen Geschichte 4 (2017), pp. 14–28; J. E. Scherer, Die Rechtsverhältnisse der Juden in den Deutsch-Österreichischen Ländern. Mit einer Einleitung über die Principien der Judengesetzgebung in Europa während des Mittelalters (Duncker & Humblot, 1901); Jacob Rader Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1990, originally published in 1938), pp. 49f; Otto Stobbe, Die Juden in Deutschland während des Mittelalters (L. Lamm, 1923), pp. 7, 153–9, 262–5. See also www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0015_0_14995.html.

3 For a translation of the text, see Dobozy, Maria and Karras, Ruth Mazo, The Saxon Mirror: A “Sachsenspiegel” of the Fourteenth Century (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). They use the manuscript in Wolfenbüttel. For a comprehensive study about how the Sachsenspiegel operated during the land settlements of the thirteenth century, see Klápste, Jan, The Czech Lands in Medieval Transformation (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450), trans. Sean Mark Miller and Katerina Millerová (Brill, 2012).

4 The four illuminated copies are in Heidelberg (https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg164/), Oldenburg (dated 1336, https://digital.lb-oldenburg.de/ssp/nav/classification/137692), Dresden (https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667916), and Wolfenbüttel (https://www.sachsenspiegel-online.de/cms/).

5 Guido Kisch outlines ways in which Eike von Repgow draws upon the Bible in Sachsenspiegel and Bible (Publications in Mediaeval Studies, Vol. 5) (The University of Notre Dame Press, 1941).

6 Dobozy, p. 183.

7 I am relying on the translation in Dobozy, p. 77, no. 22.

8 Peter Bell, Joseph Schlecht, and Björn Ommer use machine learning to identify and quantify the instances of oath-swearing on relics within the images in the Heidelberg Sachsenspiegel (University Library, MS Cod. Pal. Germ. 164), in “Nonverbal Communication in Medieval Illustrations Revisited by Computer Vision and Art History,” Visual Resources, 29.1–2 (2013), pp. 26–37.

9 The Hague, KB, 75 G 47: Eike von Repgow, Saksenspiegel, made ca. 1405 in Utrecht. 119 folios, parchment, 209x150 (145x96) mm, 2 columns, 28 lines, littera textualis. Henri L.M. Defoer, Anne S. Korteweg, and Wilhelmina C.M. Wüstefeld, The Golden Age of Dutch Manuscript Painting. Exh. cat. (The Pierpont Morgan Library, 1989), no. 6.

10 For a description, bibliography, and images, see https://unipub.uni-graz.at/obvugrscript/content/titleinfo/5951855.

11 It has been studied by Ivo Pfaff, “Das Promptuarium juris des Reichskanzlers und Bischofs Ulrich von Albeck,” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung fur Rechtsgeschichte. Romanistische Abteilung (1921), 42, pp. 158–75.

12 Bruges, Kathedraal Sint-Salvator, no signature, fol. 1r: Dit daervolghende es de ordonnancie hoemen de disschen sculdich es te cleedene ende te stellene in sinte Salvatoors kerke in Brugghe. Beghinnende telken Sinte Iansmesse middle somers. Ende de lasten vanden jaerghetiden. Ende voort alle andre lasten. Daer inne dat de voorseiden disch verbonden state. Te wat daghen datmense sculdich es van doene. Ende was desen bouc gheordoneert ende ghemaect bij Janne [..]erke. Jan de Fevere ende Jan de bliec[?] als dischmeesters vanden dische voorseit. Ende Jan de [Ra?]m Lauwereins zone, als [?]nttan[?]ghere vanden zelven dissche. Int jaer onse herren als ic screef dusentich viere hondert zeven ende vichtich upten twintschsten dach van laumaendt (my transcription).

13 A regional example from the northern Netherlands is discussed in Remi van Schaïk, with assistance from Jildou Bijlstra, “Het Groninger Stadboek gebonden en verlucht,” Historisch Jaarboek Groningen (2017) pp. 6–27.

14 Hans J. van Miegroet, “Gerard David’s ‘Justice of Cambyses’: Exemplum Iustitiae or Political Allegory?,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 18.3 (1988), 116–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/3780674; Hugo van der Velden, “Cambyses for Example: The Origins and Function of an Exemplum Iustitiae in Netherlandish Art of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 23.1 (1995), 5–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/3780781.

15 Agen, Archives Départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Ms. 42. See Alison Stones and François Avril, Gothic Manuscripts, 1260–1320: Part Two, 2 vols. (Harvey Miller Publishers, 2014), Vol. 1, pp. 261–75 for a full description and bibliography; pp. 191, 243–46, 254–56 for comparanda. Maïté Billoré and Esther Dehoux, “The Judge and the Martyr: Images of Power and Justice in Religious Manuscripts from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Centuries,” in Textual and Visual Representations of Power and Justice in Medieval France: Manuscripts and Early Printed Books, edited by Rosalind Brown-Grant, Anne D. Hedeman, and Bernard Ribémont (Ashgate, 2015), pp. 171–90 analyze images of judgment in coutumiers. See also Esther Cohen, The Crossroads of Justice: Law and Culture in Late Medieval France (E.J. Brill, 1993).

16 The text has been edited: Amédée Moullié, “Coutumes Priviléges et Franchises de la Ville d’Agen,” Recueil des travaux de la société d’agriculture, sciences et arts d’Agen (1850), 5, pp. 237–343. The source text for this edition was a manuscript in roll form, which has been lost or destroyed.

17 F.R.P. Akehurst, “Illustration and Decoration in Agen Archives Départementales de Lot-et-Garonne 42,” in “Li Premerains Vers”: Essays in Honor of Keith Busby (Faux Titre), edited by Catherine M. Jones and Logan E. Whalen (Rodopi, 2011), pp. 1–11. Images of all folios of this manuscript are available online: http://www.cg47.org/archives/coups-de-coeur/Tresors/tresors-archives.htm. It has been refoliated since Akehurst’s article and also since the photos were taken. The new foliation in pencil is rational and supersedes the various foliations in Roman and Arabic numerals. Akehurst’s foliation = the current pencil foliation + 3. Therefore, the adulterous couple appear on what is now fol. 39v, which corresponds to Akehurst’s fol. 42v.

18 As of 2004, the red book of ’s-Hertogenbosch is on long-term loan from the city archives to Het Noordbrabants Museum. A digital facsimile is availble: https://zoeken.erfgoedshertogenbosch.nl/detail.php?id=748605440. The city has notable local pride and maintains a website, Bossche Encyclopedie, that collects information about the city’s history, written by amateur and professional historians. For the item under discussion, see Valentijn Paquay, “Het Rood Privilegeboek (1): Kroonjuweel van de stad,” and “Het Rood Privilegeboek (2): Kroonjuweel van de stad,” Bossche Bladen (n.p. [2009]), pp. 84–89 and 117–22, reproduced in Bossche Encyclopedie, edited by A.F.A.M. (Ton) Wetzer, https://www.bossche-encyclopedie.nl/. See also Hanno Wijsman, “Een eed zweren op een miniatuur,” Handschriften voor het hertogdom. De mooiste verluchte manuscripten van Brabantse hertogen, edellieden, kloosterlingen en stedelingen (Veerhuis, 2006), pp. 146–51 nr. 20.

19 Other cities’ analagous books were likewise bound in red and called “red books,” for example, the Rotes Stadtbuch Hamburg from 1301–1306 (Staatsarchiv der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, Senat CI VII Lit. LaNr. 2 Vol. 1b), whose images appear online at https://drw-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de/hdhs/objekte/2268k.htm#2334.

20 The charters and privileges in Den Bosch are summarized in order of date by the former archivist of ’s-Hertogenbosch, J.N.G. Sassen, in Charters en privilegiebrieven, berustende in het archief der gemeente ’s Hertogenbosch (Stadsarchief ’s-Hertogenbosch, 1862); he discusses the Rood Privilegeboek and keys its contents to the original charters on pp. 173–83. The full text appears online https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011557104. The manuscript itself is digitized: https://zoeken.erfgoedshertogenbosch.nl/detail.php?id=748605440. I thank Lianne van Beek, Senior archivist, Erfgoed ’s-Hertogenbosch, and Marlisa den Hartog, curator at Het Noordbrabants Museum, for assistance with this item.

21 I have nuanced my ideas about this manuscript since I first published it in Rudy, Postcards on Parchment, pp. 288–90; Jos Koldeweij, “Gezworen op het kruis of op relieken,” in Representatie. Kunsthistorische bijdragen over vorst, staatsmacht en beeldende kunst, opgedragen aan Robert W. Scheller, edited by Johann-Christian Klamt and Kees Veelenturf (Valkhof Pers, 2004), pp. 158–79.

22 The Utrecht Missal is now in the treasury of the Sint-Salvatorskathedraal in Bruges and may have been commissioned for that church. For a description of this manuscript, bibliography, and images, see http://balat.kikirpa.be/object/144774

23 Koldeweij, “Gezworen op het kruis,” p. 161.

24 Jos Koldeweij, “’Vanden eedt op het heylige evangelie’. Het ‘Roode Previlegie-boek’ en de Blijde Inkomste,” Bossche Bladen, 6 (2004), pp. 16–22. Valentijn Paquay, “Het Rood Privilegeboek,” (2009) states that several of the joyous entries did not take place, but he does not cite his evidence.

25 Valentijn Paquay, “Het Rood Privilegeboek,” (2009).

26 Hamburg, Staatsarchiv, 111–1 Senat CI. VII Lit. La Nr. 2 Vol. 1b. Images and a description appear at https://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=mss/ed000059&distype=thumbs.

27 The Eidbuch of Cologne is described in In Name der Freiheit 1288–1988, Keulen 1988, 344, cat.nr 3.11.

28 Munich, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, BayHStA, Reichsstadt Regensburg Amtsbücher und Akten 6. The manuscript is described and fully digitized at https://bavarikon.de/object/bav:GDA-OBJ-00000BAV80043782.

29 For a description, see Paul Binski, P. N. R. Zutshi, and Stella Panayotova, Western Illuminated Manuscripts: A Catalogue of the Collection in Cambridge University Library (Cambridge University Press, 2011), Cat. 185, pp. 175–76, which is superseded by the online record provided by Jacqueline Cox, Keeper of the University Archives, where the manuscript is digitized: http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-UA-COLLECT-ADMIN-00003/1. The first full treatment of the manuscript was provided by M. B. Hackett, The Original Statutes of Cambridge University (Cambridge, 1970), pp. 260–85, 345.

30 Nicholas Rogers, “The Old Proctor’s Book: A Cambridge Manuscript of c. 1390,” in England in the Fourteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1985 Harlaxton Symposium, edited by W.M. Ormrod (Boydell, 1986), pp. 213–23; and “From Alan the Illuminator to John Scott the Younger: Evidence for Illumination in Cambridge,” in The Cambridge Illuminations: The Conference Papers, edited by Stella Panayotova (2007), pp. 287–99, esp. pp. 290, 297, fig. 4a.

31 Rogers, “The Old Proctor’s Book,” (1986), p. 213, n. 2 provides a collation.

32 Rogers (1986), passim.

33 Reima Välimäki, The Awakener of Sleeping Men: Inquisitor Petrus Zwicker, the Waldenses, and the Retheologisation of Heresy in Late Medieval Germany (PhD thesis, University of Turku, 2016). Those considering the stakes of extracting oaths can consult R. I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250 (2nd ed.) (Blackwell, 2007); and more recently but with a narrower scope, Derek Hill, Inquisition in the Fourteenth Century: The Manuals of Bernard Gui and Nicholas Eymerich, Heresy and Inquisition in the Middle Ages (York Medieval Press, 2019).

34 Linz, Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek (OÖLB), Cod. 177, is fully digitized https://digi.landesbibliothek.at/viewer/fullscreen/177/23/.

35 For a list of the contents, see Välimäki, The Awakener of Sleeping Men, 2016, pp. 382–85.

36 Välimäki, The Awakener of Sleeping Men (2016), describes the contents fully on pp. 382–85.