12. Climate Change, Distributive Justice, and “Pre-Institutional” Limits on Resource Appropriation

© 2023 Colin Hickey, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0338.12

1. Introduction

In this paper I attempt to build part of a distinctive theory of global distributive justice in order to give an adequate account of climate morality. My primary goal, by focusing on issues of fairness regarding distributive shares of a particular kind of global resource, is to argue that individuals are, prior to the existence of just institutions, bound as a matter of principles of global distributive justice to restrict their use, or share the benefits fairly of any use beyond their entitlements, of the Earth’s capacity to absorb greenhouse gases to within a specified justifiable range.1

Others in the climate literature have gestured in vaguely similar directions by offering principles of distribution (usually for emissions).2 Peter Singer, for instance, has defended a form of egalitarianism about greenhouse gas emissions (Singer 2006). Henry Shue distinguishes between subsistence and luxury emissions, arguing that “emissions should be divided somewhat more equally than they currently are” because it is not fair “to ask some people to surrender necessities so that other people can retain luxuries” (Shue 2014, 58, 64).

One striking feature about the inherited literature, however, is the frequency with which these views fail to clarify the implications of such principles for individuals’ duties (rather than collectives), especially in a setting prior to the existence of just institutions (what I will call “pre-institutional”).3 It is genuinely unclear whether they are offering arguments about what our “pre-institutional” duties are or only offering arguments about how our climate institutions should look (and then perhaps derivatively what our “post-institutional” duties of compliance would be with them).4

In this paper I hope to deepen the rationale—in light of our pre-institutional setting and with deliberate orientation toward individual duties—for the kinds of intuitions Shue and others in the literature correctly signal, but which have been left underexplored and latent.

I approach the task by revisiting, and drawing inspiration from, two prominent models from classical political philosophy for thinking about norms (rights, permissions, limits, etc.) regarding pre-institutional use of unowned resources generally; Locke and Kant respectively. The resource I’m directly concerned with, as mentioned above, is the Earth’s Absorptive Capacity (EAC), which is the Earth system’s ability to absorb greenhouse gasses without dangerous perturbations to the climate. EAC is a scarce, valuable, rival, non-excludable global resource that no one owns.5 All the manifold catastrophes of climate change arrive when (as is rapidly happening) this resource is used up and we emit more greenhouse gasses than can be safely absorbed—a possibility that unfortunately our extensive fossil fuel reserves allows for (see IPCC 2014 and 2018). We don’t yet have property schemes suited to distributing this resource fairly and so it is a fruitful endeavor to look back to some of the basics about appropriating unowned resources, and fair shares, from the classical liberal tradition.

To be clear, I am not defending or endorsing either Locke or Kant’s overall systems nor arguing that they offer adequate overall theories of distributive justice. Instead, I highlight them as a frame of reference to think about the pre-institutional moral problem. I extract specific and plausible resources they develop about basic pre-institutional rights, in order to ultimately make way for a preliminary account of distributive shares of EAC and the permissions, rights, and duties that attach to those. In Section 2, I consider the Lockean tradition and its focus on fundamental norms and rights of equality and self-preservation and how those can route to a preliminary account of distributive shares and pre-institutional duties. In Section 3, I turn to the Kantian tradition and its focus on fundamental norms and rights of equality and freedom and how those can route to a preliminary account of distributive shares and pre-institutional duties. In Section 4, I argue that drawing inspiration from these two views with respect to what absolutely basic pre-institutional rights individuals possess reveals a disjunctive account for why it is plausible to think that individuals have pre-institutional duties to restrict their use of EAC to within a justifiable range. Given the disjunctive account, I suggest that these duties are at least as demanding as the less demanding of the two views, and can be morally liable for repair upon violation. Both point in a similar direction regarding distributive pre-institutional shares that is more plausible than the position of skeptics who, in order to maintain their skepticism of pre-institutional duties, have to deny the basic pre-institutional rights to self-preservation or freedom. This overall picture comes with some fairly radical implications, especially for the well-off. Finally, in Section 5, I consider how targets of the duties of this purported minimal core might try to temper the implications of this disjunctive account and show why such attempts are unlikely to succeed.

2. The Lockean Model of Norms of Pre-institutional Resource Appropriation

In his Second Treatise of Government John Locke confronts the challenge of showing that property rights can be valid pre-institutionally (Locke 1963).6 The following section draws on Locke interpreters Jeremy Waldron and Gopal Sreenivasan to show how the Lockean employment of fundamental norms of equality and self-preservation generate rights to resources pre-institutionally that can serve as a minimal ground for sorting out fair distributive shares and restrictions on EAC use (Waldron 2002, esp. ch. 6; Sreenivasan 1995).

Locke thinks, plausibly, that we have a basic right to self-preservation. He comes to this through his theological commitments, that God created us and gave the world to us in common for “the support and comfort” of our being.7 This source of normativity provides the basis for norms of pre-institutional resource appropriation. It does so particularly when combined with Locke’s claim that we are all fundamentally moral equals.8 No one has superior moral status. We are all on a par. So unlike Hobbes’s egoism, which in Waldron’s words

“treats P’s survival as a sui generis source of normativity for P, something which is normatively quite opaque to Q, and it treats Q’s interest as a sui generis source of normativity for Q, which is normatively quite opaque to P”

Locke recognizes that the source of normativity of self-preservation in my case, your case, and all cases is the same (Waldron 2002, 157–8).9 This key aspect seems plausible, even if we balk at Locke’s specific religious justification for the right to self-preservation.

Combining the points about self-preservation with the claim of fundamental equality provides Locke with a basic normative scheme. Everyone has a right to self-preservation. And because of the identical source of normativity for all regarding rights to self-preservation, other things being equal (i.e., when one’s “own preservation comes not in competition”) everyone is bound to preserve “the rest of Mankind” (2T 6). As Sreenivasan interprets this, he distinguishes between everyone’s “natural right to preservation” and their natural right “to preserve themselves,” which differ with respect to the corresponding duties they impose on others:

“In the former case, others have a duty to refrain from directly endangering the life of the rights-bearer; in the latter case, others have a duty to refrain from impeding the rights-bearer from actively preserving herself” (Sreenivasan 1995, 24).

The way we exercise and make meaningful such rights is by using natural resources. These are the means of our self-preservation. So the right of self-preservation ultimately refers to one’s share of the means necessary for one’s self-preservation. It is a right of access to such resources, without being denied or facing undue burden, which will be key to thinking about pre-institutional distributive resource shares (Sreenivasan 1995, 43). Given such rights, Locke thinks there must be legitimate ways for individuals to appropriate resources for rightful private use and benefit that were previously unowned without requiring, for instance, everybody’s consent or approval by some political body (2T 26).10 Famously, Locke directs his attention to labor, which is necessary generally to realize the value of Earth’s resources.11 As Waldron puts it, for Locke, the significance of our labor is that, given the teleology of resources described above, it is “the appropriate mode of our participation in the creation and sustenance of our being” (Waldron 2002, 164). Or as Sreenivasan puts it, “property in labour’s product may be seen as the actualization of a prior right to the means of self-preservation” (Sreenivasan 1995, 41). Within the rest of the framework thus far, Locke is in a position to show the constraints of legitimate resource appropriation by labor, which operate pre- and post-institutionally. These take the shape of Locke’s so-called spoilage and sufficiency limitations, and his doctrine of charity.

The spoilage limitation comes from Locke’s claim that “Nothing was made by God for Man to spoil or destroy” (2T 31). Waldron thinks this is best understood as a way of condemning acquisitions that “perish uselessly” in the possession of the acquirer. As he puts it,

“For everyone to be denied the use of them by someone who has no use for them himself, or does not propose to put them to human use, is a direct affront to the teleological relation in which each of us stands to the bounty provided by God” (Waldron 2002, 170).

Precisely how much this norm constrains individual resource appropriation or serves to condemn inequality depends on some interpretation. Given the advent of money and market economies, one can accumulate land and appropriate resources in far greater quantities than can be directly put to personal use, in exchange for money, which doesn’t “spoil” in the traditional sense, like a storeroom of perishable crops (2T 46). So for the spoilage limitation to do work to condemn excess appropriation and inequality in modern economies, excess money must be able to be understood as “spoiling” in the normatively relevant sense. Waldron’s interpretation allows for as much, though just how far it would go in counting stored wealth as spoiling is up for grabs.12

The sufficiency limitation owes itself to Locke’s claim about resource appropriation being legitimate “at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others” (2T 27). Waldron understands this as a sufficient, rather than necessary, condition on the legitimacy of resource appropriation,

“highlighting the point that there is certainly no difficulty with unilateral acquisition…in circumstances of plenty but leaving open the possibility that some other basis might have to be found to regulate acquisition in circumstances of scarcity” (Waldron 2002, 172).13

In circumstances of plenty, as far as the rights of others are concerned, one’s use does as good as taking nothing from the unowned resources and so can be legitimately used without their consent (Sreenivasan 1995, 48). When resources become scarcer, the possibility of prejudice to others’ rights, particularly rights to the means of self-preservation, becomes more salient as do avenues to lodge complaints about the legitimacy of use (Waldron 2002, 172). Resource appropriation violates rights to the means of self-preservation when one’s use isn’t in service of one’s own self-preservation, but which could be used by others whose self-preservation is under threat (Sreenivasan 1995, 49). The sufficiency limitation therefore functions to “ensure that the material preconditions of everyone’s right to the means of preservation remain firmly in place” (Sreenivasan 1995, 49). Sreenivasan’s use of terms like “ensure” and “firmly in place” is worth noting, because they highlight an emphasis on the notions of stability and security of self-preservation indicated by the view.14 More than mere self-preservation, the right Locke is concerned with points to protections against being subject to constant threats to survival, where the rug could be pulled out at any time by significant and arbitrary powers.15

The final norm Locke employs to constrain resource appropriation by labor operates through his account of charity. Locke’s view of charity is however very unlike contemporary views, which see it either as supererogatory or perhaps as a duty without a corresponding right. Instead, while called a view of “charity”, Locke’s view reads like a component of a theory of distributive justice. As Waldron puts it, the view

“requires property-owners in every economy to cede control of some of their surplus possessions, so that they can be used to satisfy the pressing needs of the very poor, when the latter have no way of surviving otherwise” (Waldron 2002, 177).

Locke speaks of such needy individuals having “a right” and “a title” to such surpluses, which “cannot be denied” to them (1T 42). It is wrong for individuals to withhold such surpluses and they cannot be said to be exercising their property rights. Waldron even makes the case that Locke thought this form of charity could be enforced by a state, and that neither the wealthy nor civil society could stand in the way and resist efforts by the poor to seize such surpluses (Waldron 2002, 182, 185).16 The qualification of having no other means of survival is important, however, because it applies only to those who cannot subsist through their own labor, and reveals that the general way to relieve poverty involves restructuring the economy to secure meaningful employment for all who can (Sreenivasan 1995, 42–3).

There, in outline, is the Lockean model for pre-institutional resource appropriation. Of course, Locke’s account is thoroughly reliant on theological premises and so we might be skeptical that it can be helpful in our current context regarding climate change and EAC. I follow Sreenivasan in thinking that despite that fact, “the adoption of a secular outlook does not in the least diminish the contemporary relevance of the Lockean argument for private property” (Sreenivasan 1995, 6). This is centrally true because we can make good secular sense of fundamental moral equality among persons and basic rights to self-preservation of the kind employed by the Lockean model, which have implications for legitimate pre-institutional distributive shares and resource appropriation, and do so without requiring the religious teleology of resources.

However, before more completely linking the Lockean model (and its various resources) with climate change and pre-institutional EAC use, in the next section I present the Kantian model of pre-institutional resource appropriation.

3. The Kantian Model of Norms of Pre-institutional Resource Appropriation

We have, in the Lockean tradition, a view wherein pre-institutional distributive shares and norms regarding appropriation of unowned resources are determinate and normatively authoritative in light of our moral equality and rights to self-preservation. In this section, I look at a second model for thinking about these norms, inspired by the Kantian tradition, which takes moral equality and rights to freedom as the grounding mechanisms—again with an eye toward extracting plausible resources for a preliminary account of appropriation and fair distributive shares of EAC.17

From the bottom up, Kant’s view starts with everyone’s basic right of freedom, which provides the central distinction with the Lockean approach detailed above. This right is often interpreted, at its root, as independence from being constrained by another’s choice (Kant 2010, GW 4:446–7). As stated, this is too broad to be meaningful. Given that rights to freedom are reciprocal and, of necessity, mutually held by all, we can indeed be constrained by the choices of others (Kant 1996, MM 6:238).18 As Tom Hill helpfully puts it, rights to freedom are limited by “principles of justice, noninjury, contract, and responsibility to others” (Hill 1991, 48). The basic right of freedom is meant to protect, as Hill puts it, “certain decisions that deeply affect [a] person’s own life, so long as they are consistent with other basic moral principles, including recognition of comparable liberties for others” (Hill 1991, 48). The important moral value of such protection is in being able to pursue a range of desires, interests, and projects in a way that can be construed as us making our own lives (Herman 1993, 178). Having such protection is to be able to live a moderately self-determining life with its own shape that isn’t subject to the domination of others. For the rest of this paper I will take the key aspect of this basic right to freedom to rest in its commitment to and guarantee of what I will call a certain threshold sphere of effective agency.19

In order to actually be free in this sense, we must act and pursue ends in the world. We need physical means to carry out our projects. We need a sphere of freedom, manifested in external objects, that is normatively (and empirically) protected from the interferences of others. But unlike, for instance, the right to bodily integrity, we cannot simply point to our bodies to explain intuitively what it is that others cannot encroach upon. Meaningful and effective agency in the world requires things external to ourselves to use, which need to be acquired (MM 6:248).20 Eventually, Kant thinks that this will require the state, which is in some ways the central reason why he argues we need to leave the state of nature, and why with more space I would also argue that we have duties to participate in the creation of institutions of climate justice.21

But in advance of that, Kant thinks that when we combine our right to freedom as effective agency with the claim that it is necessary to use external objects to make meaningful that freedom, a series of derivative rights can be generated. These derivative rights Kant calls, rights to “empirical possession” and “intelligible possession”.

The former (rights to “empirical possession”) are the kinds of rights that allow us to condemn someone for taking away the apple I am holding just before I bite into it, or the shirt from off my back. In cases when we are literally in physical possession of some object, Kant thinks we can understand the claim that others not take it from us—in roughly the same way we can when we point to our bodies and make claims against others not to violate them.

But simple rights to “empirical possession” are obviously not sufficient to secure our effective agential freedom. We need more than mere protection against violation of objects we currently possess. We need some assurance, to pursue most of our ends, that when we place objects down their normative status is still as part of our rightful sphere, which others cannot encroach upon. So, Kant introduces another kind of right he thinks we have; rights to “intelligible possession”. These are the kinds of rights that allow us to condemn someone for taking the apple I was going to eat while I step away to the bathroom, or taking my shirt from my laundry hamper. Recognizing rights to such things is hugely important for securing a sphere of effective agency. Given that unilaterally using unowned resources takes them from the common stock and thus makes them unavailable to others (in both the empirical sense that they cannot make use of it and in the normative sense that they would have a new obligation to respect my acquisition), any intelligible possession potentially limits the freedom of others.

Kant makes sense of this by considering conditions on resource appropriation, claiming that “something external can be originally acquired only in conformity with the idea of a civil condition, that is, with a view to it and to its being brought about, but prior to its realization” (MM 6:264). Some attempts to use things, or claim some pre-institutional distributive share, are going to be ruled out by this, because they couldn’t reasonably survive ratification through institutions as we approach a “civil condition.” That is, some distributive schema obviously violate a notion of equal freedom and mutual protection of spheres of effective agency, and with it they violate notions of fairness and mutual justifiability. Anna Stilz provides a helpful reading of what this amounts to for Kant:

“For my possession of this particular object or piece of land to genuinely impose an obligation on others to recognize and respect it, it has to be something that they could agree to, viewed as free and independent individuals who also have a similar interest in holding property. And in order for them to be able to agree, my holdings cannot infringe their human right to independence: for if a regime of external property jeopardized this right, then their hypothetical consent would be impossible to obtain. This means two things: first, that my property rightfully extends only to a “fair share,” one that is consistent with others’ exercising a similar right. And second, I am reciprocally bound to recognize others’ property once I have appropriated my own, for otherwise I would dominate them by forcing them to recognize a right in me that I am not prepared to grant others. My property rights, in sum, must be justifiable to others as free and independent persons if they are to impose valid obligations” (Stilz 2009, 43–44).

These conditions are especially important because Kant thinks that property rights come with a right to use, individually, coercion against interference to protect such property in defense of our external freedom (MM 6:233).22 Claiming a certain authority to use pre-institutional resources (with obligations that others not interfere and rights to defend against such interference) without reciprocally recognizing others’ rights to use by limiting one’s own use is a form of domination. It is a way of disrespecting the rights to freedom as effective agency of others.

4. Locke, Kant, and EAC

We have now seen two distinct models for starting to think about pre-institutional distributive shares and their connected norms (rights, permissions, limits, etc.) regarding an individual’s pre-institutional use of unowned resources. Both appeal to norms of equality to generate their schema, but while the Lockean picture pairs equality with rights to what is necessary for secure and stable self-preservation the Kantian picture combines equality with what is necessary to secure rights to meaningful freedom, interpreted as a sphere of effective agency. Each view is a general view about resources, but given the particular structure and function that EAC plays, as our resource of interest in the context of climate change, each view has plausible implications that indicate the existence of a determinate core of pre-institutional restrictions on EAC use, as a moral minimum. Addressing the implications drawing on the Lockean and Kantian pictures, in turn, I argue here that since either view is more plausible as a moral minimum than alternatives which are altogether skeptical of the existence of such duties, because the fundamental rights they trace are so plausible, we have a disjunctive argument for pre-institutional distributive shares that respect those rights and thereby for the existence of pre-institutional duties to restrict EAC use. As such, I take the more important theoretical controversy to be determining whether the moral minimum is where the Lockean view would place it or where the Kantian view would, and what that implies, given some individuals are falling below that minimum entitlement, in order to establish how demanding such duties are. The Kantian picture seems to presuppose the requirements for secure and stable self-preservation, but might extend significantly further depending on how much Kantian effective agency requires by way of material goods. From one angle, this may appear to make the Kantian picture more demanding because it requires that others are owed a higher standard. From another angle, however, it also has the prospect of protecting more of our own resource use. In the end, I hope to show that in our empirical context with respect to climate change, these differences don’t amount to much.

4.1 Implications of the Lockean Account

Recall that for the Lockean one is only licensed to appropriate surplus resources when certain conditions are met. If those conditions are not met, then the resource appropriation is not licensed because it constitutes a violation of a negative duty owed to others against interference with their rights. In particular, the Lockean view issues restrictions on surplus resource appropriation when such use competes with the secure and stable self-preservation of others. As long as others are secure in their capacities for self-preservation, as a conception of pre-institutional justice and distributive shares, the Lockean view can tolerate significant inequalities. Yet as soon as the inequalities place some above and others below a threshold of secure self-preservation, where the surplus competes with the deprivation, the normative mechanisms of the Lockean-style view go to work.

Locke himself, appropriately indexed to his era, was largely concerned with land as a resource. Owning and working land was the quintessential way of securing one’s self-preservation. The modern world is very different from Locke’s world. Owning and working land is not the generalizable way of securing self-preservation. And yet, Locke’s theory is built around a basic norm that allows it to carry implications through malleable empirical circumstances. In the modern world, use of EAC itself functions similarly to land ownership in Locke’s time. Using EAC is the quintessential way of securing the conditions for self-preservation. This is not a necessary fact (indeed, it better not be!). Conditions for self-preservation can be improved without EAC (e.g., with access to clean energy). And more access to EAC doesn’t automatically improve conditions for self-preservation (similar, in that respect, to land ownership for Locke, whose value towards self-preservation also depends on other things). While we will always emit some greenhouse gases (if nothing else but to breathe), we need not structure our forms of life, institutions, and means of securing self-preservation (among other things) around doing so. This is the whole point behind radical decarbonization. The goal, in fact, is to get to a point where those low-level GHG emissions don’t really, in any meaningful sense, count as using EAC at all because EAC is functionally specified as a “scarce” resource. Once we have a safe enough operating space, while it is still biophysically true that there is a discrete amount of GHG that could be emitted before raising temps, e.g., 2°C, it loses its status as a normatively significant resource for appropriation and distribution. All of that said, even if it is fungible and not intrinsically valuable (but instead as a means to what it lets us do an be) that doesn’t detract from its value, contingently, in a given context, for supporting our most basic needs (to energy, but also tied up in everything from clean water, food, clothing, shelter, medical care, etc.). Empirically, in the real world as it is now, security in self-preservation is closely associated with EAC use and alternative uses of EAC compete with what could go (or have the benefits of the usage go) towards securing self-preservation.

There are hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people lack the conditions for secure self-preservation, which would be alleviated with more access to EAC use. Countless others use EAC for much beyond self-preservation. Furthermore, we know that there is a very tight global constraint on EAC use altogether. And lastly we know, given that EAC is a scarce global common pool resource, unlike many other resources, use in one corner does actually compete with everyone around the globe (and many of those into the future). My emitting GHGs doesn’t prevent others from emitting GHGs, but my use of the limited and functionally specified EAC budget, qua scarce resource, does compete with others’ use of the EAC budget. Together, these elements indicate that the conditions which license one to use surplus EAC are unlikely to be met, which in turn recommends pre-institutional restrictions on using EAC for the modern Lockean.

At first glance, one might think that in such circumstances of scarcity the Lockean view points to a restriction on entitlements to EAC use beyond one’s own self-preservation, until the self-preservation of others is secure. To do otherwise would be seen as violating one’s negative duty to not interfere with the self-preservation of others. This would be a particularly demanding implication, and though it would certainly satisfy the Lockean provisos, and avoid wrongdoing, the full view is slightly more complicated.

When Locke discussed land, he was careful to make clear that meeting the conditions for licensed use (i.e., abiding by the provisos) didn’t necessarily mean that land use was illegitimate unless everybody had a plot they could work for their self-preservation (Sreenivasan, 1995, p. 39). Locke’s own position then wasn’t then a right of each to use and own land, per se. One individual could have used and owned massive portions of land, employed people on it with a living wage, and not thereby threatened their rights to the stable conditions for their self-preservation, even though they were prevented from owning a share of land (Sreenivasan 1995, 51).23

Taking that lesson to the modern context, the Lockean position shouldn’t be understood as a right to or restriction on EAC use per se, and can take on the lessons of Pareto efficiency. Just like the person who used disproportionately large tracts of land thereby preventing others from owning it, but employed others on it with a living wage, it is possible that an individual’s massive use of EAC could support or expand the secure self-preservation of others who were thereby prevented from using the EAC themselves. The fundamental operative norm for the Lockean is secure and stable self-preservation, and the actual distribution of EAC use is merely an important means of realizing that norm. Inequalities in EAC use only become problematic when they undercut that norm.24

However, this should not comfort the status quo because most of us have clearly undercut that norm. What the above paragraphs tell us is that as long as some are not secure in their self-preservation one must either restrict EAC use to only what supports one’s secure self-preservation or use any EAC beyond that to support the self-preservation of as many individuals as it could have supported were it left to them.25 It is clear that our conditions are such that some are not secure in their self-preservation. While it is difficult to make general claims about what precisely is required for secure and stable self-preservation, if we look at any plausible measurement of development or the kinds of things we might investigate to assess how norms of secure self-preservation stack up, hundreds of millions, if not billions of people worldwide likely fall below that threshold. Nearly 750 million people live in extreme poverty on less than $1.90 a day, hundreds of millions more live on less than $3.10 a day (World Bank 2016). In 2018, about 2 billion people experienced moderate or severe levels of food insecurity (UN FAO 2019). Around a billion people lack access to electricity and 3 billion are exposed to dangerous pollution levels because of lack of access to clean cooking solutions (UN, 2020) and 400 million lack access to vital health services (WHO 2015).

It is equally clear that most of the global affluent meet neither of the two disjuncts that would make permissible their EAC use for the Lockean in a context where others are not secure in their self-preservation. While there are possible (perhaps actual) exceptions, the overwhelming majority of such individuals use more EAC than supports their secure self-preservation. But it is also unlikely that they can plausibly claim that the benefit from their EAC use above that threshold is justifiably distributed to support the self-preservation of others thereby prevented from using the EAC (unlike the employer landowner).26 And because of that, the Lockean view, which is concerned with equal fundamental pre-institutional rights to self-preservation in order to account for a preliminary picture of fair pre-institutional distributive shares, speaks with loud implications, condemning most of our EAC use as wrongful and in violation of the rights of those below the self-preservation threshold.

It is worth clarifying the nature of this proposed rights violation. Recall, going back to Sreenivasan, the Lockean view distinguishes between two aspects of the right to self-preservation. The first implies duties against directly endangering the life of the rights-bearer. One might try to argue that our GHG emissions violate this kind of duty. For reasons I can’t address here, I worry this is an uphill battle. However, by splitting the right to self-preservation, the Lockean has another rights-based, distributive justice-oriented mechanism for condemning excess appropriation as wrong. The second associated right (to “preserve oneself”) implies duties to refrain from impeding the rights-bearer from actively preserving themself. And it is this right, in the context of fairly distributing entitlements to appropriate a scarce EAC that many millions could (and indeed would if given the opportunity) actively use as the means to preserve themselves, which appropriating surplus EAC runs afoul of.27

Before discussing the Kantian account and comparing the two, the above elements of the Lockean view allow it to avoid a potential worry that has been lodged at others, like Peter Singer, for focusing too much on GHG emissions directly and not recognizing that distributive justice takes place in a broader context.28 The Lockean view, as I have presented it, does widen our lens past exclusive attention in isolation to GHGs (or EAC, as it were) to focus on a full bundle of resources for what is necessary to support secure self-preservation. It is sensitive to historical contingency, and empirical variation depending on looming threats and available resources. However, just the same, those contingencies are precisely what allows us to say that, until there is some radical change in empirical context like a massive technological innovation or radical population shift, there is something at a global scale unique about EAC and requires us to be concerned from the perspective of principles of appropriation and distributive justice with the overuse of a scarce, valuable, rival, non-excludable global resource that no one owns and how it interfaces with basic access to secure and stable self-preservation. Unlike distributing a bushel of apples, which can be exploited and merely disappear for future use and benefit and then be replaced by pears or oranges, EAC is a resource that when over-exploited at scale doesn’t just disappear for future use and benefit, it brings a legacy of climatic disruption thereby undermining future substitution strategies. This is part of the reason why EAC use has to be managed and deserves its centerpiece in the theory, even if the Lockean view can and should agree secure and stable self-preservation takes place within a broader network of resources.

4.2 Implications of the Kantian Account

Let me step back to briefly discuss the implications of the Kantian account (concerned with rights protecting a sphere of effective agency for a preliminary) for a pre-institutional, account of distributive shares of, and restrictions on, EAC.

While the Lockean can be sensitive to some inequalities (the asymmetry of power that certain forms of inequality in resource holdings generates can constitute a threat of domination that disrupts the security and stability of self-preservation even if their absolute holdings would be sufficient absent such domination), it is plausible that the Kantian account which highlights effective agency as its fundamental pre-institutional right is less tolerant of inequalities. The threat of domination or disruption to a sphere of effective agency appears before the threat of domination or disruption to secure and stable self-preservation. So, while the Lockean-style view might be able to tolerate relatively significant pre-institutional inequality while keeping everybody above the threshold for secure and stable self-preservation, it is much more likely that such inequality could disturb the Kantian-style view’s aim of mutually attainable effective agency for all.29

Derivative on that broader aim, the Kantian view will come to govern EAC use given its close association with—beyond mere survival—all aspects of people’s freedom to set ends and pursue their projects. Just as the Lockean view can point to the countless masses who lack secure self-preservation, which would be alleviated with greater access to EAC, the Kantian will see that the broader aim of mutually attainable freedom as effective agency is quite clearly disrupted by contemporary distributions of EAC appropriation, and in virtue of that, some individuals must have outstripped their fair share entitlements.

Like the Lockean view does for its basic norm of self-preservation, the Kantian takes justification with respect to its norm of freedom as effective agency in a larger context than simply EAC use, even though it is the scarce, unowned resource that triggers pre-institutional norms of justice so as to not upset equality of freedom. So, a Kantian fair distributive share of pre-institutional resources need not mean maximal equal rights to EAC use and can similarly take on the lessons of Pareto efficiency. Some may require, for all manner of reasons, more or less actual EAC to be able to effectively express their agency and pursue their projects. But like the Lockean regarding self-preservation, if one uses a larger share than another it has to be justified in virtue of achieving consistency with or not undermining mutually held effective agency.

So, when someone uses EAC beyond what is sanctioned for mutually attainable effective agency (without sharing the benefits to support equal attainment for others) they will have violated pre-institutional principles of justice that apply directly to individuals which protect the basic Kantian pre-institutional concern for freedom qua effective agency. In doing so, and falling outside one’s fair distributive share, individuals encroach upon another’s (or some other’s) pre-institutional rights of distributive justice, which constitutes a wrong.

To see this more schematically, imagine the Kantian distributive scheme allots entitlements to the EAC budget (before dangerous climate change begins) between 100 people. Maximal mutually attainable effective agency might mean that some people get 1%, others might get .5% or 2%. If, on this basis, I am normatively entitled to 1%, but instead take 2% of the budget, I am taking something beyond my fair share that was allotted to another or some others. I can of course, descriptively, emit more GHGs, but this just takes additional percent from the EAC budget, either squeezing yet others out of a share, or contributing to shooting past the budget. Doing so outstrips my entitlement and normatively crowds others out from having their own fair share.30 Other things being equal this disrupts the norm of equal freedom as I am now in a privileged, exceptional space, even if I can’t know or identify who all is disadvantaged.

To reiterate, this is not an enforceable wrong by the coercive arm of the law yet because we are operating in a context where such institutions don’t yet exist, but it may be appropriately condemnable through other mechanisms of holding to account (e.g., reactive attitudes) and the appropriate target of moral persuasion, nudging, education, etc. Moreover, this form of wrongful rights violation brings with it a residue, or normative link, that follows it until institutions are actualized where redress for the violation could potentially be legitimately enforced by the coercive arm of the law (e.g., in the form of a retroactive EAC use/benefit tax).

We might not be able to determine where the threshold for effective agency rests (and thereby what constitutes overshooting and encroaching upon others’ rights) with “mathematical exactitude,” as Kant ultimately aims. There is surely some ambiguous range as to what is required to meet that threshold for individuals. So, it is best to think of these kinds of pre-institutional distributive shares as prohibitions on resource appropriation/benefit as prohibitions against using more than would be allowable at the highest end of this range.

However, it seems even in its non-mathematically exact form, the Kantian account is already determinate enough to definitively rule out a rather wide range of resource appropriation. For example, obviously it would rule out all of the EAC going to those whose names begin with “H”. So too, slightly more controversially, they would rule out existing distributive patterns. There is simply no way to justify, consistent with the demand for a threshold of effective agency regarding would-be users of EAC, as an unowned global common pool resource of the kind we have described, the notion that the average American could use more than 30 times the average Bangladeshi with parallel inequalities in human development.31

From this angle, the Kantian-style account may look to deliver a more demanding set of duties on, e.g., the average American than the Lockean-style approach; distributive shares and pre-institutional rights protecting a sphere of effective agency are likely more extensive rights protecting secure and stable self-preservation. However, given how the views are constructed, the story is not so simple.

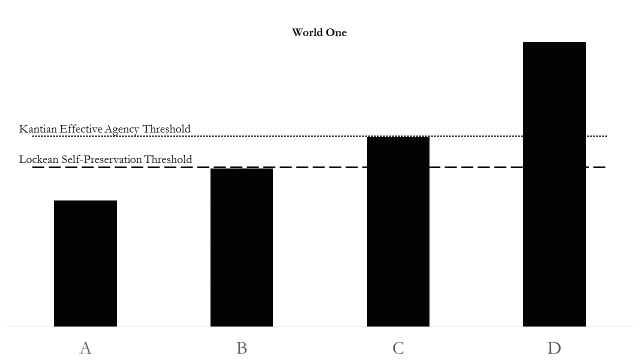

One way to help clarify this is by looking at the following two graphs. Each represents a different possible world populated by four individuals and their resource appropriation. Also indicated is what resource allotment in the world would meet both the Lockean subsistence threshold and the Kantian fair share distribution.32

Figure 1. Comparing Thresholds: World One.

In World One (Figure 1), the Lockean analysis would suggest that C and D both have illegitimate holdings in virtue of A’s deprivation and their surplus above the threshold of secure self-preservation. For the Lockean, the fact that B does not reach the Kantian threshold is immaterial to the analysis of rights and entitlements. But as long as A falls short of the threshold of secure and stable self-preservation, either through lack of access to the direct use of EAC or via the lack of benefit from others’ direct use, both C and D count as violating A’s rights and are called upon to relinquish their use or share the benefit from it. Furthermore, the fact that D has far more illegitimate holdings and could raise A to the Lockean threshold without C having to give anything up all the while still maintaining an overall resource advantage does not thereby entitle C to their own surplus (even though C is not beyond what would be their “Kantian” threshold). The surplus holdings of C are implicated because A and B have rights to secure and stable self-preservation and in circumstances of scarcity, such as the world presents, C’s holdings are still proximate impediments to those rights being fulfilled. Finally, if C were to give up or share the benefit of some EAC to raise up A, then D, without giving up anything, and maintaining significant resource advantages would be back in the moral clear on the Lockean-style view.33

The Kantian picture, however, would evaluate this world differently with respect to who is owed redistribution and who bears the duties to do so. The Kantian analysis would suggest that C is in the moral clear. C is entitled to their own holdings because they are within the range of what is required for C to achieve effective agency. C has therefore not illegitimately appropriated the resource and cannot be required to give up some of their holdings, even if doing so would raise another above the self-preservation threshold without simultaneously dropping C below that threshold.34 On the other hand, the Kantian analysis would suggest that D has illegitimately used the resource. D would be required to disgorge whatever of their surplus portion of the resource (or the benefit from it) above the Kantian mutually attainable threshold is required in order to bring both A and B to the threshold for effective agency.

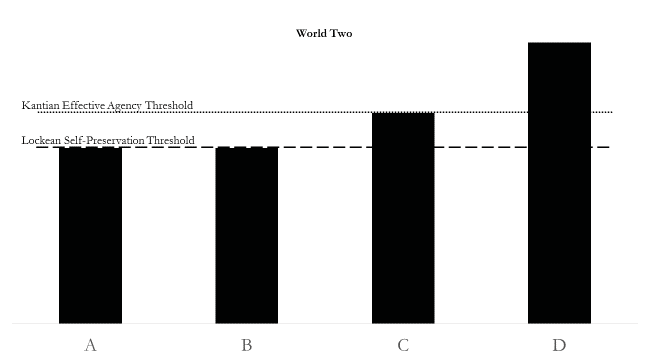

Consider, by contrast a second world (Figure 2), whose implications might already be clear.

Figure 2. Comparing Thresholds: World Two.

In World Two, the Lockean analysis implies no pre-institutional redistributive duties. Everybody is above the secure and stable self-preservation threshold. From the Lockean perspective, the mere fact that D could eliminate some inequality and raise A and B to the Kantian threshold, does not indicate any unfulfilled rights, wrongdoing, or generate any duties.

The Kantian-style analysis, on the other hand, would suggest again that D has illegitimate holdings; owed to A and B. Now, imagine that D relinquishes some holdings, so as to bring everybody above the threshold for effective agency but in the process expands their own capabilities to effectively realize their ends and so still maintains a comparative advantage. On the interpretation I’m offering, that kind of inequality is not problematic for the Kantian. However, it is possible that D could grow their pot of resources large enough so as to undermine the effective agency of the others, even if their actual resource holdings don’t actually change.

It is worth drawing out these theoretical differences to better understand each view and how they operate, and much more could be said. However, we need not exhaustively dive into the details to generate a significant takeaway. While across possible worlds we can locate important divergence, in our current world, as it is, grappling with the moral problem of climate change, there is likely significant convergence between the outputs of the views. If one doesn’t like the Lockean mechanism (which requires that others need only meet a lower threshold, but symmetrically also protects fewer of our own resource entitlements against the demands of duty) the way to distance oneself from it while still plausibly being committed to some notion of pre-institutional moral equality will be to move closer to the Kantian model (which requires that others meet a higher threshold, but symmetrically also protects more of our own resource entitlements against the demands of duty). But, in the empirical context of our climate duties, when we “crunch the numbers”, so to speak, settling the controversy is not particularly necessary for action guiding purposes. I will say more about this below, but given how tight the global EAC budget is in order to reach the 1.5° or even 2° targets, how many users and would-be users there are, and how many people face threats to their secure self-preservation, the threshold for effective agency that is mutually attainable is likely not far from one’s Lockean threshold.35

In this I think we have a preliminary case for pre-institutional distributive shares of EAC and a disjunctive account of why it is plausible to think that individuals have pre-institutional duties to restrict their use of EAC, or share the benefits fairly of any use beyond their entitlement, to within a justifiable range, and can be morally liable for repair upon violation. The Lockean and Kantian accounts are not just because they come from prominent figures in Western philosophy, but because they highlight very plausible but distinct fundamental pre-institutional rights, which in the context of climate change and EAC serve as plausible preliminary accounts of fair distributive shares and the permissions, rights, and duties that attend such shares. Appealing to different fundamental norms, the models point in a similar direction that I contend surely is an advance on the “Hobbesian” skeptic of pre-institutional constraints to resource appropriation, precisely because they can reasonably be construed as taking pre-institutional moral equality seriously, while the Hobbesian can’t. Capturing a form of moral equality, even as narrowly proscribed and modest as the Lockean’s equal rights to secure and stable self-preservation, seems so foundational that it is plausible to see it as a condition of adequacy of a view. While more work might ultimately need to be done to settle the demands of each view and settle between them, for now we can tentatively conclude that our pre-institutional duties to use EAC are at least as demanding as the less demanding of the two views, and perhaps as demanding as the more demanding of the two views.36

5. Demandingness and Priority to Disgorge

I want to briefly consider how we should think about the differences between the Lockean and Kantian accounts as they relate to duties to disgorge surplus resources (outside one’s fair distributive share, pre-institutionally) and the demandingness thereof. Each view is a basic account of resource entitlements and legitimacy of using/benefitting without an explicit account of degrees of wrongness associated with illegitimate use or priority to disgorge resources among those with a surplus. Without filling in a complete account, there are things to say to better understand the conceptual space. We can help distinguish between these categories by reflecting on the extent and purpose of resource appropriation above the threshold for legitimacy (i.e., outside one’s fair distributive share).

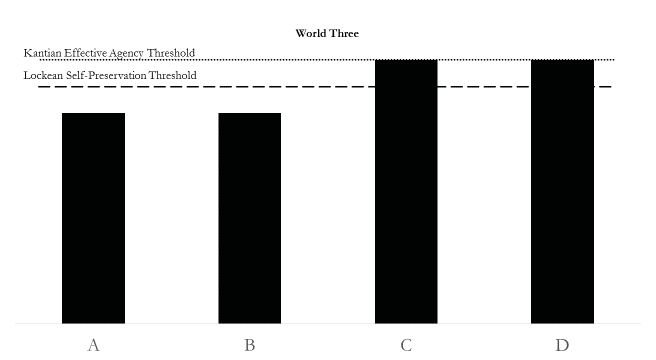

Let’s look first from the perspective of the Kantian view. While it is committed to the importance of a threshold of effective agency, this presupposes as more basic the lower Lockean style threshold of secure self-preservation. Because of this, if we imagine a third world (Figure 3, below) of supreme scarcity where circumstances don’t admit of securing the threshold of effective agency for all and some others aren’t even secure in their self-preservation, even the Kantian will have strong reason to suggest people give up resources that are in service of securing effective agency for securing self-preservation. This is one way of narrowing the gap between the views in context.

Figure 3. Comparing Thresholds: World Three.

Now consider things from the perspective of the Lockean. If we go back to World One, the Lockean is committed to the idea that both C and D are illegitimately using surplus resources. However, there is no reason for the Lockean to deny (indeed very good reason for them to accept) the extremely important moral value of effective agency. Because of this, the Lockean has avenues to suggest that D is in a worse position and priority to disgorge should fall on them first. They are holding on to more resources that are in service of things of less moral value. This is yet another way in which the gap narrows between the two views.

Just as the Kantian threshold can sometimes provide some buffer against the wrongness of, and priority to disgorge, surplus use past the Lockean threshold, we might wonder whether there are morally significant values attached to other purposes for surplus use beyond securing effective agency that serve a similar function. The disjunctive view I have presented has the potential to be very demanding, and those concerned about demandingness are likely on the lookout for other moral values to buffer against the demands of what they will have to sacrifice. In principle it does seem as though there are important additional distinctions to make. Even if everybody is above the threshold for effective agency it seems worse and a higher priority for disgorgement when people use their surplus in ways that are completely wasteful or merely pursuing pure preference-satisfaction or hedonic fun than if they use it to contributing to meaningful, identify-shaping projects. The latter can be deeper and more significant moral values (though they are not always as neatly separable, given that identity-shaping projects contribute to what counts as preference satisfaction and pleasure, and vice versa). I want in no way to deny the possibility of such distinctions, even if it would take more work to argue about how they stack up. I do however want to maintain that if in fact we think, as we should, there is a baseline of morally vital considerations like the Lockean or Kantian thresholds to which everyone has an entitlement, it is implausible to think that these kinds of admitted moral values could override the demand to disgorge. To do so would be to violate the most basic form of reciprocity that we sketched by Anna Stilz above. To do so would be to deny to others what you think would be minimally required for yourself. The world we currently inhabit, unfortunately, is one in which these distinctions largely get swamped out in generating a relatively clear sense of the kinds of demanding action required of those worried that these distinctions might make a difference to them. There are such huge numbers of individuals falling below either threshold that the reductions in, or benefit sharing of, EAC are so large they will cut against waste, luxury, pure hedonic pursuits, and deeply meaningful projects of vast swaths of the global affluent, who are each (from the global perspective) positioned more like D than C in World One.

So when scholars attempt to raise issues of demandingness as potential defeaters of duties, or engage with Henry Shue’s distinction between “subsistence” and “luxury” emissions to try to find where the line sits at which their resource holdings are protected against, I want to suggest it is implausible if they arrive at a picture very close to the status quo.

This is an important point at which my view intersects with the other main view to explicitly attend to the pre-institutional/post-institutional distinction with respect to distributive justice. As I mentioned above, Christian Baatz agrees that, “from the moral point of view, even in the absence of institutions, fair shares exist” (Baatz 2014, 3). In light of this, Baatz is also concerned with trying to specify what duties individuals have, and comes to the conclusion that they have the duty to “take already available measures to reduce emissions in their responsibility as far as can reasonably be demanded of them” (Baatz 2014, 15). As he interprets it, emissions reductions can be “reasonably demanded” insofar as

“an action generating GHG emissions either (a) has no moral weight or (b) an alternative course of action (that is to be considered as an adequate substitute) causing less emissions exists” (Baatz 2014, 15).

Baatz pitches this as a “first approximation” and, in a reply to critics, seems to suggest that these should be taken as what can be reasonably demanded “at minimum” (Baatz 2016, 161).37 This is an important clarification because, if taken as exhaustive, these two conditions risk failing to adequately capture everything that could be reasonably demanded of people, and which duties should actually attach to “fair shares.” There are genuine questions about whether we would be able to reach our targets of reducing global emissions (from 2010 levels by about 45% by 2030 and to net zero by 2050), if all of the emissions that cleared these standards were protected against the demands of duties to be reduced or eliminated (IPCC 2018, 14).

For one, very few emissions actually have no moral weight. Many of our emissions are caught up in our projects and ends that are deeply autonomy enhancing, identity-constituting, and meaningful. They facilitate familial obligations. They support the bonds of friendship. They satisfy deep and enduring preferences. Even the highest luxuries have some moral weight. At the very least they can be sources of pleasure, which is a morally significant feature. So, if we can only reasonably demand those emissions that have no moral weight be reduced/eliminates, the list might be quite small. This worry can be somewhat mitigated if we interpret Baatz as meaning “justice-relevant” moral value, which some of the categories above might not have, which would generate further reasonable demands. Doing so would require an account of what values are “justice-relevant,” but would be an important step in filling out the gap left by Baatz’s preliminary account that could be put into further conversation with the Lockean-Kantian account I develop here.

It is also worth remarking on Baatz’s second condition. He doesn’t provide a ready-made interpretation for what would count as an “adequate substitute”. Trying to fill it in runs into potential difficulties quickly. Intuitively, if I live in Florida and do all city/highway driving, it seems like a fuel-efficient car might be an adequate substitute for driving a gas guzzling Jeep. But imagine I live in the mountains of Colorado and do significant off-roading. It is less clear switching to a hybrid would be an “adequate” substitute. This ambiguity, which depends on the plurality of values involved in our decision-making, has the potential to multiply through many of our behaviors. This connects to a broader point, which is just to say that even if we have switched to the least-emissive substitute for a given action, behavior, or activity we aren’t licensed to infer that such emissions are legitimate. We might have to drop them altogether to abide our fair share. What I think this reveals is that there is a lot more work to be done than where Baatz leaves us, but it also might direct our attention away from “substitution” specifically and towards overall entitlements closer to the picture I have been painting with the Lockean-Kantian account.

Ultimately, seeing Baatz’s account as a preliminary take about what is required “at minimum” invites us to investigate further what other, additional kinds of demands might be reasonably made. Exactly how far he would be willing to go is an open question. When clarifying, in his Reply to Critics, that the conditions he sketched were what could be reasonably demanded at a minimum, Baatz still refers to his view as a “permissive” account, which suggests that the view really is designed to offer more protections than existing accounts of climate duties (Baatz 2016, 165). This makes sense when we situate it in the broader picture that is central to Baatz’s account, which is to foreground how dependent our emissions are on the “carbon-intensive structures” we are embedded within (Baatz 2014, 10). With respect to our emissions entitlements and the duties that attach to them, his basic orientation is that the more dependent our emissions are on structural features around us, the less we can be asked to give them up.

So however Baatz might eventually fill in the story from the preliminary account, it is almost sure to be more permissive than the Lockean-Kantian account I have been developing here. Just as the Kantian threshold for effective agency protected more of our own resource entitlements against the demands of duty than the Lockean, Baatz’s ultimate account would almost certainly protect even more than that in virtue of how they depend on external structures. These are good arguments to have out.

But I will close with a few final notes that I suggest are in my favor. First, once we have made the move to talking about EAC rather than emissions, per se, we will be able to question the very idea that having one’s emissions dependent on structures is the kind of thing that could defeat one’s duties of distributive justice. Some of one’s emissions might depend on carbon-intensive structures that cannot be avoided without threatening to disrupt the Lockean or Kantian norms, but that doesn’t mean we are entitled to the use of the EAC. Given that we can use and, to some measure, replenish EAC, it seems plausible that even if we are forced into emitting more carbon due to intensive structures, the principles of justice aren’t simply defeated. One might, for instance, be bound to replenish EAC in other ways (e.g., offsetting), as compensation. Dependence on structures, then, isn’t the normatively fundamental feature which should toggle or temper demandingness. Instead it should be, I suggest, our abilities with respect to using EAC and our vulnerabilities with respect to the Lockean/Kantian thresholds.38

But there are also further general reasons to be skeptical of any companion views that might attempt, via alternative routes, to similarly protect more of our EAC use from the demands of duty than the Kantian threshold, given the moral problem we face in climate change. These reasons ultimately boil down to the fact that settling moral duties in this domain occurs in conditions of uncertainty. Like every such case there is an element of moral risk involved. Of course, there could be a technological magic bullet that eliminates vulnerability below the Lockean self-preservation threshold or expands the sphere of mutually attainable Kantian effective agency to mitigate the demandingness of the duty. While that possibility needs to be balanced in the all things considered determination of the duties, the overwhelming weight of the uncertainty and moral risk is on the other side, such that even upon interpreting the Lockean and Kantian threshold rather thinly we likely still face the prospect of tragically more people falling below them. I will raise three in particular here.

The first is what happens when we consider population projections over the next century. The UN World Population Division projects, using their “medium fertility” models, that by 2050 there will be 9.7 billion people on the planet. By 2100 that figure goes to nearly 11 billion, adding more than three billion people in “less developed regions” from current population figures (UN DESA 2019). These numbers significantly increase the likelihood that there will be people falling below the Lockean threshold in order to trigger its implications for those above it. But moreover, it shows us that we need to be wary of how expansively (regarding EAC heavy features) one could interpret secure self-preservation or effective agency that is mutually attainable (or some other fundamental norm), given an increase in the number of individuals needing a fair share, so as to not completely overshoot the global budget with increasing populations.39

A further reason to doubt the plausibility of more permissive assessments of what individuals are allowed to use in the wake of the problem we face involves probability assessments regarding actually staying within the EAC budget. The IPCC AR5 figures requiring 40–70% emissions reductions by 2050 and 100% or further by 2100 all leave as much as a 33% chance that even accomplishing such reductions we surpass the, already overly-conservative, 2°C threshold of dangerous climate change. To increase the probabilities, for a yet smaller target at 1.5°C, requires an even smaller global budget, which translates in to smaller mutually attainable shares. As such we are further unlikely to be able to count, as normatively protected, the kinds of emissions that more permissive views might want in order to mitigate the demandingness of the duty without making it significantly less probable, or even impossible to hit such targets.

These are not going to be easy conclusions for many to accept. Our lives are structured to use EAC far beyond the Kantian’s more permissive threshold in their quotidian details but also to build bonds of friendship, engage in meaningful work and identity crafting activity, pursue necessary recreation from life’s stresses, etc. Unfortunately, even more foundational moral norms are at stake.40

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, I have argued that individuals are, pre-institutionally, bound as a matter of global distributive justice to restrict their use, or share the benefits fairly of any use beyond their entitlement, of the Earth’s capacity to absorb greenhouse gases (EAC) to within a specified justifiable range. While I can’t defend the claim here, it is also worth seeing how this kind of argument can serve as the normative basis for what distributively just global institutions to govern climate change would look like in allocating access to, or shares of, that resource and its benefits—thereby translating authoritative but more coarse-grained pre-institutional moral prohibitions, requirements, and permissions regarding distributive justice into specified, fully determinate institutional ones. This kind of translation is important for bringing not only the specification, coordination, and enforcement of duties that institutions uniquely provide, but in doing so ultimately will help make it less arduous for many individuals to fulfil their duties of distributive justice, given greater compliance and social support.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful for the insightful and constructive referee comments that I received during the review process. I also want to thank Ingrid Robeyns and the Fair Limits team for feedback and discussion, as well as the unending help I received from Maggie Little, Madison Powers, and Henry Richardson. Part of the work of this project was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 726153). This chapter was first published in European Journal of Philosophy, 2021, 19: 215–235.

References

Anderson, E. 1999. What is the point of equality? Ethics, 109, 287–337. https://doi.org/10.1086/233897

Baatz, C. 2014. Climate change and individual duties to reduce GHG emissions. Ethics, Policy and Environment, 17, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2014.885406

Baatz, C. 2016. Reply to my critics: justifying the fair share argument. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 19, 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2016.1205710

Beitz, C. 2009. The Idea of Human Rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blomfield, M. 2013. Global common resources and the just distribution of emission shares. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 21, 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2012.00416.x

Caney, S. 2012. Just emissions. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 40, 255–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/papa.12005

Cripps, E. 2013. Climate Change and the Moral Agent: Individual Duties in an Interdependent World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dolšak, N. and Ostrom, E. 2003. The challenges of the commons. In The Commons in the New Millennium: Challenges and Adaptations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 3–34.

Gardiner, S. 2004. Ethics and global climate change. Ethics, 114, 555–600. https://doi.org/10.1086/382247

Griffin, J. 2008. On Human Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herman, B. 1993. The Practice of Moral Judgment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026397

Hickey, C., Rieder, T., and Earl, J. 2016. Population engineering and the fight against climate change. Social Theory and Practice, 42, 845–870. https://doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract201642430

Hill, T. 1991. Autonomy and Self-Respect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC. 2014. Summary for policymakers. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, C.B. Field, et al. (eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/ar5_wgII_spm_en.pdf

IPCC. 2018. Summary for policy makers. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report, V. Masson-Delmotte, et al., (eds.). Geneva: World Meteorological Organization, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf

Jacobson, M., et al. 2017. 100% clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight all-sector energy roadmaps for 139 countries of the world. Joule, 1, 1–14, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2017.07.005

Johnson, B. 2003. Ethical obligations in a tragedy of the commons. Environmental Values, 12, 271–287. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327103129341324

Kant, I. 1996. The Metaphysics of Morals (MM), ed., M. Gregor, trans. M. Gregor. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, I. 2010. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (GW), ed., M. Gregor, trans., M. Gregor. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kingston, E. and Sinnott-Armstrong, W. 2018. What’s wrong with joyguzzling? Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 21, 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-017-9859-1

Locke, J. 1963. Two Treatises of Government, rev. ed., ed., P. Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maltais, A. 2013. Radically non-ideal climate politics and the obligation to at least vote green. Environmental Values, 22, 589–608. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327113X13745164553798

Mauritsen, T. and Pincus, R. 2017. Committed warming inferred from observations. Nature Climate Change, 7, 652–655. doi:10.1038/nclimate3357

Miller, D. 2009. Global justice and climate change: How should responsibilities be distributed? In The Tanner Lectures on Human Values Vol. 28, Peterson, G. (ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: The University of Utah Press.

Neumayer, E. 2004. National carbon dioxide emissions: Geography matters. Area, 36, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00317.x

Nickel, J. 2007. Making Sense of Human Rights, 2nd Ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy, State and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Nussbaum, M. 2009. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

O’Neill, O. 2005. The dark side of human rights. International Affairs, 81, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00459.x

Raftery, A., et al. 2017. Less than 2°C warming by 2100 unlikely. Nature Climate Change, 7, 637- 641. doi:10.1038/nclimate3352.

Shue, H. 1996. Basic Rights, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shue, H. 2014. Subsistence emissions and luxury emissions. In Climate Justice: Vulnerability and Protection. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1993.tb00093.x

Simmons, A. J. 1992. The Lockean Theory of Rights. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Simmons, A. J. 2001. Justification and Legitimacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, P. 2006. Ethics and climate change: A commentary on MacCracken, Toman and Gardiner. Environmental Values, 15, 415–422. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327106778226239

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. 2005. It’s not my fault: Global warming and individual moral obligations. In his (co-ed.) Perspectives on Climate Change: Science, Economics, Politics, Ethics: Advances in the Economics of Environmental Research, Vol. 5. Amsterdam: Elsevier JAI, pp. 285–309.

Sreenivasan, G. 1995. The Limits of Lockean Rights in Property. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stilz, A. 2009. Liberal Loyalty: Freedom, Obligation, and the State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Traxler, M. 2002. Fair chore division for climate change. Social Theory and Practice, 28, 101–34. https://doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract20022814

U.S. EIA. 2017. International Energy Statistics. Available at: http://www.eia.gov/cfapps/ipdbproject/IEDIndex3.cfm?tid=5&pid=5&aid=8 [Accessed 13 May 2020].

UN. 2020. Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy. Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/energy/ [Accessed 13 May 2020].

UN DESA (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division). 2019. World Population Prospects 2019. Available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ [Accessed 13 May 2020].

UN FAO. 2019. The state of food security and nutrition in the world. Available at: http://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition [Accessed 13 May 2020].

UNDP. 2018. Human Development Reports. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data [Accessed 13 May 2020].

Vanderheiden, S. 2006. Climate change and the challenge of moral responsibility. Ethics and the Life Sciences, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.5840/jpr_2007_5

Waldron, J. 2002. God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations of John Locke’s Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WHO. 2015. New report shows that 400 million do not have access to essential health services. 12 June. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/uhc-report/en/ [Accessed 13 May 2020].

World Bank. 2016. Poverty overview. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview [Accessed 13 May 2020]

1 Though I won’t argue so here, I also think this serves as the normative basis for what distributively just global institutions to govern climate change would look like in allocating access to, or shares of, that resource and its benefits.

2 For some broader surveys on various principles scholars have considered see Gardiner (2004) or Caney (2012).

3 Shue, e.g., is prone to drape his work in collective language, filling it with “we”, “the affluent”, or “affluent nations,” etc. (see e.g., Shue 2014, 49–51, 73, 76, 294), though he does recognize the need for an account of the transition and the end goal, p. 56–8, 73.

4 Many inside the climate ethics literature and beyond have thought that pre-institutional rights and duties with respect to resource appropriation are either non-existent or too unclear to deliver over any content, and therefore individuals, at most, have duties to support the creation of collective institutions to solve the problems of climate change. See Sinnott-Armstrong (2005), Kingston and Sinnott-Armstrong (2018), Maltais (2013), Johnson (2003). Elizabeth Cripps (2013) prioritizes promoting institutions in. It is also a central part of Onora O’Neill’s (2005) work that is skeptical of duties to support human rights outside of a context of institutional assignment. One notable exception to this trend comes, as I will discuss at-length below, from Christian Baatz (2014) who acknowledges the pre- and post-institutional distinction and claims that “from the moral point of view, even in the absence of institutions, fair shares exist.”

5 For a selection of others that discuss this idea see Shue (2014), Traxler (2002), Vanderheiden (2006), Blomfield (2013), Dolšak and Ostrom, (2003). While much more could be said of each of these features, which I take up elsewhere, it is worth mentioning a few things. First, the scarcity here is “functionally specified” by being indexed to a normative notion of safety and determined contextually within a specific time frame, with respect to a specific body of practices, and interdependent with some other networks of moral norms (so, while it is true that no matter what, there is a finite amount of GHGs that can be absorbed before temperatures rise 2°C, EAC would not be functionally scarce if, e.g., I were the only one emitting). Precise debates about this budget are complicated and I defer largely to the IPCC, but the account is not beholden to them and can serve as the right structural model for whatever the most defensible case is. This is a global constraint, given how the global climate system works. Moreover, EAC is valuable not intrinsically, but because of what activities it lets us do and what kinds of lives it lets us lead (if it weren’t, it wouldn’t be scarce). These are possible without EAC (which is a good thing for the clean energy transition), but just because it is fungible, that does not detract from the idea that it is valuable in a given context and contingently supportive of our most basic needs. It is rival not because my emitting stops you from emitting, but my use of the fixed and functionally specified EAC budget, qua scarce resource, does compete with others’ use of the EAC budget. It is non-excludable, and hence a global “common pool resource” of the kind Ostrom describes precisely because it is difficult to prevent potential appropriators globally from accessing the resource (via emissions), which encourages free-riding. Finally, it is unowned in that we do not have recognized property regimes, private or otherwise, to manage the use, purchase, sale, transfer, etc., of EAC. Those more standard aspects of ownership entail things like the entitlement or protected dominion to: access, use, manage, exclude, derive income from, or transfer a good. There are no received mechanisms for conceptualizing any of those protections or entitlements (much less fairly assigned), regarding EAC, even if people certainly are using the resource. This is importantly not to say that there are no binding norms governing the use or benefit from the use of EAC in a pre-institutional setting; I’ll argue below that there are significant binding norms, but they are not norms of ownership.

6 From here on I will refer to the first treatise as 1T and the second treatise as 2T and refer to paragraph numbers.

7 Regarding Locke’s view on original communism see 2T 25–6. Locke thinks we are “sent into the World by [God’s] order and about [God’s] business” (2T 6). God’s design has given us the right “to make use of those things, that were necessary or useful to his Being.” God implanted us with the strong desire for self-preservation and “furnished” the world with things that are “fit” and “serviceable,” for our subsistence as the means of our preservation to which we are directed by our senses and reason, by God’s design (1T 86).

8 As Waldron has argued forcefully, this position about equality is also held on strictly theological grounds. Regarding Locke’s view on equality see 2T 4 and 123. See also Waldron 2002, 6.

9 This doesn’t mean that pre-institutionally resource appropriation has to be strictly egalitarian. Indeed, part of the very goal of the Second Treatise is to justify some “disproportionate and unequal” distribution. But it does provide the basis for constraining possible resource appropriation. See 2T 50 and Waldron (2002, 152).

10 Sreenivasan calls this the “consent problem” and sees it as Locke’s central task to solve.

11 I can’t settle controversies about why exactly labor confers property. See, e.g., Sreenivasan (1995, ch. 3), and Nozick (1974, 174).