9. Sufficiency, Limits, and Multi-Threshold Views

© 2023 Colin Hickey, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0338.09

1. Introduction

Sufficientarianism, which has by now been amply discussed in the literature on distributive justice, maintains that we have particularly weighty (perhaps even distinct in kind) reasons to make sure that people have enough of certain goods. A more recent entrant to the literature on distributive justice is a view called “limitarianism.” Coined by Ingrid Robeyns, limitarianism maintains that it is impermissible to have too much of certain goods (Robeyns 2017). In other words, there are upper limits on how many resources we can justifiably have. Others in the literature have taken limitarianism as “turn[ing] the sufficiency view on its head” (Volacu and Dumitru 2019). While the sufficientarian identifies a threshold past which everyone should reside, the limitarian identifies a threshold below which everyone must stay.1

In this chapter I assess the relation between these two views.2 In particular, I investigate whether sufficientarians should (or even must) also endorse a limitarian thesis, and similarly whether limitarians should (or even must) also endorse a sufficiency thesis. I argue affirmatively that sufficientarians have very good reasons to adopt a limitarian thesis, as do limitarians to adopt a sufficientarian thesis. To put it differently, rather than simply turning the other view ‘on its head,’ I hope to show that the two views each contain within themselves the seed for the other.

The question of whether each view must also embrace the other is more contentious. While I entertain some speculative arguments about a necessary conceptual connection between the views, the results are more tentative. So, though it may in principle be possible to affirm one view without the other, doing so is hard to motivate and not advisable.

Of course, there is substantial variety in the type of sufficientarianism or limitarianism people do or could adopt. I am trying, here, to be widely ecumenical to understand the general structure of the relation between the views; so this isn’t to say there couldn’t be good reasons for certain versions of one to reject certain versions of the other.3

I end the chapter by suggesting some reasons why it should actually be less surprising than we might think that our most plausible theories of distributive justice would turn out to be “multi-threshold” views of a certain structure, containing (at least) one sufficientarian threshold and one limitarian threshold. Without discounting the challenge of specifying the substantive content of such sufficientarian and limitarian thresholds, the general structure maps on so neatly to our standard deontic conceptual language that it ought not to be a shock that our theories of distributive justice would take a parallel form.

2. Should Sufficientarians Also Be Limitarians? Must They?

I begin, in this section, by considering whether sufficientarians should (or even must) also endorse a limitarian thesis defining an upper limit on resource accumulation. I do so first by responding to a preliminary objection that would derail the idea from the start. I then consider some more positive reasons in favour of sufficientarians additionally endorsing a limitarian thesis. I close the section by entertaining some more speculative conceptual reasons as to why doing so might indeed be necessary.

2.1 A Preliminary Objection

The idea that sufficientarians should also be limitarians might strike some who are familiar with the sufficientarian literature as immediately objectionable. Traditionally, sufficientarianism has been pitched in connection with two theses: one “positive” and one “negative” (Casal 2007). The positive thesis highlights the particularly weighty reasons that we have to ensure that people secure enough of some goods.4 The negative thesis, on the other hand, is meant to suggest that once everyone has crossed the threshold with enough, no distributive criteria apply to the distribution of benefits and burdens above the threshold.5 As such, sufficientarianism is often taken to be a more minimalist kind of theory of distributive justice. It is a way of saying that, once people have enough, we do not have to worry about certain kinds of inequalities, or always prioritize the worst off.

In light of this standard picture, the potential problem for suggesting that sufficientarians ought also to adopt a limitarian thesis is not difficult to see. Wouldn’t sufficientarianism’s negative thesis rule out the possibility of also being committed to limitarianism from the start? After all, the negative thesis endorses the claim that “no distributive criteria apply” above the sufficiency threshold. But by suggesting that there are limits to the amount of resources one can justifiably accumulate, limitarianism is a distributive criterion above the sufficiency threshold. On its face, this seems inconsistent with the standard sufficientarian picture, and so attempting to merge the two might seem dead on arrival.

There are three points to make in response, in order to blunt the force of the charge and preserve the possibility that sufficientarians at least can additionally endorse limitarianism, so that we can determine below whether they should (or must). The first two concern how we should understand the status of the negative thesis and its relation to a potential limitarian commitment. The third challenges whether sufficientarians should endorse the negative thesis at all, and if so in what form.

The first point is a methodological one. In evaluating whether the negative thesis would foreclose the possibility of a concomitant limitarian threshold (much less recommend one), we should be attentive to the context and purposes for which sufficientarian arguments were proposed. This is the best way to understand and assess the core commitments of sufficientarianism and whether they should either prohibit or suggest a companion limitarian thesis. In other words, I suggest that we should interpret the claim of the negative thesis in light of its discursive target.

With that in mind, we can move to the second point. When Paula Casal first introduced and tried to clarify the conceptual core of sufficientarianism with the distinction between the positive and negative thesis, interestingly she pitched the latter as a “rejection of egalitarian and prioritarian reasoning at least above some critical threshold” (Casal 2007, p. 299). Noticeably absent is a rejection of limitarian reasoning. Now, of course it may appear slightly unfair to point out the omission in Casal’s statement as evidence of possible compatibility between the two. After all, the term “limitarianism” was only introduced subsequently. That said, it is in fact revealing for what the standard target is for defending and conceptually isolating sufficientarian thinking; namely, it targets particular kinds of (egalitarian and prioritarian) distributive patterns in ideal theorizing about distributive justice. Especially when we conjoin Casal’s claim with other classical statements of the negative thesis in the literature, a picture starts to emerge about the intended shape of the concept, and scope of the negative thesis, which is informative for how we should interpret its potential compatibility with a limitarian partner.

Consider, for instance, Harry Frankfurt’s version of the negative thesis: “if everyone had enough, it would be of no moral consequence whether some had more than others” (Frankfurt 1987, p. 21).6 Or, similarly, while considering and rejecting the negative thesis, Shields summarizes it this way: “once everyone has secured enough, no distributive criteria apply to [additional] benefits.”7 Unsurprisingly, the antecedents matter greatly here. Neither statement of the negative thesis provides any license to infer that a limitarian thesis couldn’t apply in circumstances where people do not have enough. But limitarianism (and its call for limits on individual resource accumulation) was explicitly introduced as a partial, non-ideal theory of justice. It was only ever meant to apply in our radically non-ideal circumstances.8 So even if the fundamental core of sufficientarianism requires a robust negative thesis of this variety (something I will question below), it is consistent with the fundamental core of limitarianism because the limitarian thesis is reserved for when the antecedent of the negative thesis is unsatisfied; a non-ideal world where countless people fall below the sufficiency threshold. Restricting the domain of potential compatibility in this way does not betray the spirit of sufficientarianism, which also has significant designs on non-ideal theorizing.9 So, for a significant (perhaps predominant) range of purposes to which we should want to put the concept to productive use, sufficientarianism’s negative thesis doesn’t preclude a limitarian counterpart.10

This brings us to the third point to mention in response to the preliminary objection, which is that there is a plausible case to be made that sufficientarians should reject this formulation of the negative thesis anyway. If sufficientarians do not endorse this version (call it the “strong” version) of the negative thesis, then there is no reason to block them from endorsing distributive principles above the sufficiency threshold (of any stripe, not merely limitarian principles). The argument for releasing the negative thesis, at least in this strong form, leans heavily on the influential work of Liam Shields, who has argued (persuasively, I think) that the essential conceptual core of sufficientarianism resides in the conjunction of the positive thesis from above and what he calls the “shift thesis.”

Shift Thesis: once people have secured enough there is a discontinuity in the rate of change of the marginal weight of our reasons to benefit them further (Shields 2012; 2016).11

I cannot, here, wade too far into the debate about Shields’ view, except to signal that it seems he is on to something important in denying that there is any good motivation at the conceptual core of sufficientarianism for maintaining the strong negative thesis. In fact, it has been the feature that has seemed particularly objectionable to critics of sufficientarianism; that it is indifferent to inequalities above the threshold that it shouldn’t be indifferent to (Shields 2012, p. 104).12 Undercutting this objection to sufficientarianism, while still preserving focal concern with certain distinct and morally important kinds of deprivation is likely a positive step for the sufficientarian. This is especially true if, as I argue below, they can do so while capturing an even more sensible version of the intuition undergirding the negative thesis—that some inequalities above the threshold do not matter.

On the other hand, Robert Huseby has recently developed a very different understanding of the negative thesis, which would actually make accepting it point more strongly in the direction of also adopting limitarianism (Huseby 2020).13 Instead of conceiving of the negative thesis, in marking out a domain above which distributive criteria do not apply, as referring to the same threshold as the threshold which marks out the category it is especially important for people to reach (i.e., the sufficiency threshold), he interprets it as referring to a different threshold. On this interpretation, the negative thesis is meant to refer just to the idea that “there is a level of well-being N such that above it, justice concerns do not arise, and such that those below [have] absolute priority over those above it” (Huseby 2020, p. 213). That level, N, might be very much higher than the sufficiency threshold, which would help avoid sufficientarianism being indifferent to certain inequalities and claims of those positioned above the sufficiency threshold.

This reading of the negative thesis actually makes it particularly compatible with limitarianism (indeed, it almost turns the negative thesis into a limitarian thesis about where the upper limit resides).14 On this interpretation, both the negative thesis and limitarianism indicate a position above the sufficiency threshold where additional goods provide no moral or justice-based value, and where those below it have absolute priority. All of which is to say, there is plenty of room for sufficientarians to also endorse limitarianism.

2.2 The Positive Case in Favour

In the previous subsection, I have tried to respond to a preliminary objection to the idea that sufficientarians should also be limitarians. Hoping to have carved open enough space for such a possibility, in this subsection I will develop the rudiments of a positive argument in favour of the idea.

There is an obvious sense in which the positive case rests on the merit of the arguments for limitarianism. If they are compelling, of course, the sufficientarian should endorse them, even if that were to require dropping a conceptual claim like the strong negative thesis.15 And while I will say somewhat more about the significant power of the undergirding intuitions and strength of those arguments later on, this would not be a particularly interesting finding because it has the form ‘S should believe L because L is true.’16

So instead, I want to talk about some other (more internal) reasons why there is a case to be made for sufficientarians to embrace limitarianism. I want to suggest a number of ways in which doing so helps the sufficientarian address lurking issues, while coming with little theoretical cost.

I mentioned above, following Shields, that there may be good reason for sufficientarians to drop the strongest version of the negative thesis. In part, this is because it seems to have counterintuitive implications, namely that it is “indifferent” to inequalities above the threshold that it shouldn’t be indifferent to. Someone who is treading water just above the threshold is in a very different position than a billionaire whose wildest dreams are satisfied.17 Dropping that strongest version of the negative thesis provides the conceptual space for addressing those counterintuitive implications. But actually, warding off the objection requires providing a positive account of why one is not in fact indifferent rather than merely pointing out (by dropping the strong negative thesis) that the view is not in principle indifferent.

In articulating when we can be said to have too much, limitarianism provides just such an account. Moreover, it does so in a way that can preserve what is likely the most fundamental and plausible insight from the original formulation of the strong negative thesis, which is that some inequalities above the threshold do not matter. It just refines the insight by pointing out that some do. For the limitarian, the inequality between the person making $60,000 and $65,000 might not matter (assume that they are both comfortably above the sufficiency threshold) but the inequality between someone making $15,000 (assume that puts them just above the sufficiency threshold) and $1,000,000 (assume that puts them above the limitarian threshold) does.18 This also preserves the sufficientarian’s resources for rejecting certain forms of prioritarian and egalitarian reasoning, without opening itself up to the most obvious kinds of objections they can lodge about priorities or inequalities that clearly seem to matter.

Additionally, the discourse around sufficientarianism is often heavily recipient-oriented. It focuses largely on characterizing what people are owed, and why those entitlements are particularly morally important (or their deprivation particularly pernicious), etc., rather than who does the owing. Supplementing with a limitarian view (especially, as discussed below, which is justified by the very same values) helps fill out the corresponding duty side of the equation for a more complete theory of distributive justice. It does not, of course, fill in all the gaps about responsibility, but does provide a much-needed infusion in that direction. Rejecting it basically amounts to rejecting the lowest-hanging fruit of the duty side of the ledger. I will say something more about this point in Section 5, below.

Embracing a limitarian thesis can, therefore, help the sufficientarian solve some problems and fill in some gaps. But it also can do so at relatively low theoretical cost. One of the main worries people have about limitarianism is scepticism about the idea that we can identify upper thresholds in a non-arbitrary way (see Timmer 2021b; 2022).19 Embracing limitarianism, for the sufficientarian, adds another threshold to be sure. But they are already committed to the existence and defensibility of one non-arbitrarily specified threshold (see Huseby 2020). So, adding another (limitarian) one doesn’t bring a unique kind of problem (as it would for a view that didn’t accept any thresholds). In for a penny, in for a pound, as it were. The key point is that the general kind of vulnerabilities for limitarianism don’t add much theoretical cost to a view which already is committed to the same kind of theoretical device, justified by the same kinds of reasons, at its foundation. This is particularly true if sufficientarians follow Huseby’s novel formulation of the negative thesis mentioned above, in which they are essentially already committed to identifying and defending the kind of upper threshold the limitarian would adopt.20 A separate point, also worth raising, is that once situated with non-ideal concerns, which is the particular focus for limitarianism, this kind of worry about arbitrariness, and therefore its potential theoretical cost, becomes even smaller as there can be good reasons to endorse thresholds that are legally or politically defensible, even if in some sense metaphysically arbitrary.21

2.3 The Necessity Claim (and the “Circumstances of Justice”)

Now that I have considered a few arguments in favour of the idea that sufficientarians have some important reasons to also endorse a limitarian thesis, I want to entertain the idea that they must do so. In particular, I want to look at one speculative argument that enquires into the very concept of the “circumstances of justice” themselves to locate a reason why sufficientarianism must also be committed to a limitarian thesis (under some description).

Consider, then, the standard concept of the “circumstances of justice.” Essentially, the circumstances of justice serve as the conditions for the application of principles of justice. Following Rawls (who is himself following Hume), these are the “conditions under which human cooperation is both possible and necessary” (Rawls 1999, p. 110).22 The conditions include properties of persons as well as properties of their environments. The circumstances are indicated by contexts in which individuals of roughly similar powers live together in time and space; where they are vulnerable to having their plans blocked by others. They are contexts where people’s needs and interests are similar or complementary enough to make mutually advantageous cooperation possible. But they are also different enough to result in different ends and purposes and “conflicting claims on the natural and social resources available” (Rawls 1999, p 110). Moreover, people are always operating with limited knowledge, where bias and distortion are common. Perhaps most importantly for our discussion, they are conditions of moderate scarcity of resources. As Rawls puts it,

Natural and other resources are not so abundant that schemes of cooperation become superfluous, nor are conditions so harsh that fruitful ventures must inevitably break down. While mutually advantageous arrangements are feasible, the benefits they yield fall short of the demands men put forward.23

What I want to suggest is that the very fact of being in the circumstances of justice, and therefore for any sufficientarian thesis to apply, itself may imply a tacit commitment to a limitarian thesis. Why would this be true?

There is an obvious sense in which the condition of moderate scarcity implies some collective limits.24 But as a descriptive matter, this is not yet interestingly normative in the way the limitarian thesis is meant, which purports to go beyond a mere general description of collectively finite resources. In order to count as normative, in the relevant sense, there has to be the possibility of failing to live up to the standards of the norm.

The route from the basic fact of finite resources to a properly normative limitarian thesis can go a number of different ways. One way is defending a normative threshold that is short of the finite physical limits.25 For example, consider climate change, where the (normative) limit of fossil fuels we can permissibly collectively burn is lower than the (descriptive) limit of all existing fossil fuel reserves we could burn because of the various destructive consequences of doing so.26

Another, and more universal, way to bridge the descriptive fact of finite resources to an appropriately normative limitarian thesis is in the move from a collective limit to matters of distribution and individual rights, permissions, and entitlements. For example, perhaps it is permissible to collectively use all of the world’s finite supply of some resource, but as long as we care at all about how that use is distributed (which the sufficientarian necessarily does), the non-normative finite collective limit will imply normative individual limits as participants, shareholders, users, etc. To see this point schematically, imagine a world with 10 people and 30 resource units. Suppose, per sufficientarianism, everyone is entitled to 2 units. By implication there is a meaningful upper normative limit for any individual at (at most) 12 units (2 from their sufficiency entitlement and potentially 10 from the surplus after everyone else secures their sufficiency entitlement). The precise individual limits that are implied as a matter of distribution from collective limits in relation to sufficientarian guarantees are, of course, up for debate. They may not be the limits that would be associated with a claim to an equal share. They may not be the limits Robeyns identified in coining “limitarianism,” which target resources beyond what is necessary for a flourishing life.27 But as long as we are concerned with some kind of fair share distribution that limits individuals to some non-exclusive share or another, the logic of a meaningful limitarian thesis is inevitable; to steal a phrase, it’s just the price that we’re haggling over (i.e., where the limitarian threshold it set). So regardless of how that debate is settled, I want to suggest that the collective limits inherent to being in the circumstances of justice imply some meaningfully normative individual limits. That may be enough, consistent with the spirit of the category, to show that the sufficientarian must also be committed to a limitarian thesis, under some description.28

This would be true unless through cooperation we can somehow overcome the conditions of moderate scarcity in a way that relaxes such distributive norms, which does not seem plausible for at least three reasons. First, empirically, the scale at which people’s valuable needs remain unmet is truly massive.29 Second, the way we conceive of scarcity in the circumstances of justice is also determined by the vast depths of human desire and imagination, as well as recognizing inevitable competition for status and positional goods, which together are likely to provide inexhaustible sources of want that inevitably outstrip what is made possible by our resources (even as they grow through cooperation, technology, efficiency gains, etc.). Third, even if cooperation is somehow sufficient to produce enough surplus to end conditions of moderate scarcity, it is not clear that this should license a relaxation of distributive norms such that it eliminates at least some meaningful limitarian thesis (rather than merely indicating the limit should be slightly higher). Doing so would seem to undermine the conditions of success and therefore the stability of being without moderate scarcity. Put more conceptually, it would be strange if justice working well could remove us from the circumstances of justice. It would seem more appropriate to me, in such a successful case of cooperation, to say we would have realized justice, with an imperative to preserve it, or adjust upward its ambitions.30

Attending more carefully, then, to the circumstances of justice may plausibly require the sufficientarian to accept a meaningfully limitarian thesis. But before moving to the next section, there is a broader point to be made. Some of the arguments used to motivate sufficientarianism, or criticize egalitarian or prioritarian thinking, are worth reconsidering in the context of thinking about the circumstances of justice. For instance, Roger Crisp famously uses his “Beverly Hills case” to suggest that if choosing between a group of rich and super-rich people for whom to offer fine wine, it would be “absurd” to necessarily require prioritizing the merely rich, just because they are worse off. Once individuals are above a certain level, he suggests, “any prioritarian concern for them disappears entirely” (Crisp 2003a, p. 755).

But there is a real issue for this kind of argument that is exposed when viewed in the context of the circumstances of justice. Namely, it is not clear why we should take Crisp’s intuition as pointing against equality or priority views in favour of sufficiency views, rather than simply indicating that the world he is considering is not operating in the circumstances of justice at all! To do the work he wants, the intuition relies on an implicit assumption that it is in the circumstances of justice and the prioritarian or egalitarian would be committed to giving the wine to the rich group rather than the super-rich group. But it is not clear that that is a legitimate assumption. This is a slippery move that happens often in the literature. The world in which our choice is between giving wine to the rich or super-rich is decidedly not one of moderate scarcity, which is the condition for the application of principles of justice.31 And there is a reasonable case to be made that this is what explains Crisp’s intuition, more than any necessary advantage of the sufficientarian.

Obviously, given my project here, this isn’t to cast doubt on the sufficientarian. But it is to highlight another way in which attending to the circumstances of justice in our arguments in this domain is crucially important. In particular, this is worth remarking on because this is the same type of argument that might be lodged against a sufficientarian adopting a companion limitarian thesis. For example, could we really justify redistributing the wine from the super-rich just above the limitarian threshold to the merely rich just below (when both are “above a certain level”)? The intuition that we might not be able to justify such a redistribution could only serve as an objection to the idea that sufficientarians should also embrace limitarianism if limitarianism was committed to such redistributions. But it isn’t and needn’t be.32 In fact, a more plausible explanation for the force of the intuition that we don’t need to redistribute in this way is precisely because the case as described in the thought experiment falls outside of the circumstances of justice (where the limitarian thesis applies), rather than indicating some problem with the limitarian thesis itself. In this way, attending to the circumstances of justice is also important as we evaluate the success of specific arguments and thought experiments regarding distributive justice.

The broader ‘circumstances of justice’ argument that the sufficientarian must also embrace a limitarian thesis is admittedly challenging.33 Recall, I have tried to be ecumenical about the form of sufficientarian and limitarian thesis. One might think, however, that even if there are necessarily limits, in order to count as meaningfully limitarian, the thesis would have to have more defined content than what limits could potentially fall out of this “circumstances of justice” argument. Or that the justification for the limit must be of a certain shape. It is hard to see any principled reason to believe this, without knowing more about the aggregate limits and what is demanded by the sufficiency threshold, but I do not have space to fully consider this possibility. However, it is worth situating that potential doubt in the broader discussion, because it wouldn’t cast doubt on the overall thesis, just on the idea that it would be a necessary claim. So, while I believe this argument is certainly worth entertaining, if it is ultimately uncompelling, I will be content to leave this section with a set of arguments from above to at least suggest that there are strong reasons in favour of sufficientarians also endorsing a limitarian thesis.

3. Should Limitarians Also Be Sufficientarians? Must They?

In the previous section, I considered whether sufficientarians should (or even must) also endorse a limitarian thesis, making the case that they indeed should. In this section, I proceed from the other direction to consider whether limitarians should (or even must) also endorse a sufficientarian thesis. Similarly, I conclude that they should. I again entertain a speculative argument for a conceptually necessary connection. And while it is debatable whether they must necessarily do so, in principle, any plausible and well-motivated limitarianism will.

Unlike sufficientarianism, limitarianism was never formulated with a symmetrical “negative” thesis, so there is not a similar initial worry that would rule out the limitarian’s adoption of an additional sufficientarian thesis. So, we can move directly to the positive reasons in favour of so doing.

3.1 The Positive Case in Favour

The main reason why limitarians should also be sufficientarians becomes clear when we consider the most plausible kinds of arguments on offer for the limitarian thesis itself. Those very arguments rely on robustly sufficientarian reasoning. The limitarian takes advantage of how hard it is to dislodge the intuitions at the core of sufficientarianism; tracing the particular moral importance of securing certain basic goods to the idea that some excess resource holdings which compete with them are unjustifiable.

There are two chief arguments that have been advanced in favour of limitarianism, which we can summarize as follows:

The Argument from Urgent Unmet Needs (UUN)—There are morally urgent unmet needs which could be eliminated via redistribution of resources from the extremely wealthy. Meeting such needs would come at the cost of significantly less morally important values from those above the limitarian threshold in the process.34

The Democratic Argument (DA)—Extreme wealth undermines core democratic values and rights to political equality. The affluent are able to convert their economic power into political power and skew nominally democratic processes toward their interests (via campaign and Super PAC spending, lobbying, gatekeeping, media access, agenda setting, think tanks, etc.). This strips lower earners of the real value of their democratic participation (Robeyns 2017, pp. 6–10; Christiano 2012).

Each of these arguments derives its force from a concern that can be (at least partially) put in terms of sufficientarian language (admittedly the first is easier than the second). The reason why luxury resources or extreme wealth should be capped and redistributed, according to UUN, is precisely because of the moral importance of raising people above a certain standard and eliminating unmet urgent need.35 Recall the statement of the sufficientarian’s positive thesis from above, which highlights the particularly weighty reasons we have to ensure that people secure enough of some goods.36 The way in which DA can be seen as potentially embracing a sufficientarian thesis is perhaps more obscure because on its surface it is about “political equality.” However, it is not uncommon for sufficientarians to think that for some goods the sufficientarian threshold that is called for is also an egalitarian demand. Sometimes having enough means having an equal share. This is particularly clear when considering political rights such as voting. Having one vote clearly isn’t enough if others have ten (and of course, even if one has equal formal voting rights, disproportionate hurdles to exercising the vote, or inequality shaping the political agenda, might also reveal insufficient political representation or participation). While the limitarian’s exact commitments with respect to political equality are up for debate, what is clear from DA is that extreme wealth means that some people have too much political power and, in virtue of that excess, given its positional nature, others have too little to be consistent with democratic values. That can reasonably be understood as a sufficientarian concern, such that sufficient political power for all, to whatever extent the limitarian ultimately thinks that actually needs to be equalized, requires limiting wealth and its attending political influence accordingly.

Both of the core arguments for limitarianism, UUN and DA respectively, can be understood as embracing the essence of (or at least implicating a form of) sufficientarianism, at least within the scope of the domain to which the limitarian thesis is meant to apply. It seems, then, that denying some version of sufficientarian thesis would be unmotivated and self-undermining for the limitarian.

3.2 The Necessity Claim

While the two main arguments that have been used to advance limitarianism seem to imply a commitment to sufficientarian logic in order to justify the proposed limit, there are other arguments one could give for adopting limitarianism. Both UUN and DA are other-regarding reasons for limitarianism, but one could also provide self-regarding reasons. For instance, perhaps extreme wealth, resources, goods, etc., reduce one’s own autonomy, or are intrinsically bad or corrupting of spirit.37 So it is, in principle, possible to reject the force of the UUN and DA (and their inferred commitment to a sufficientarian thesis) while still endorsing limitarianism. However, doing so seems particularly ill-considered. It is very hard to see how a self-regarding or intrinsic argument for limitarianism would be more plausible than UUN or DA, which would be required in order to defeat the case for limitarians also endorsing a sufficientarian thesis. If there is any role for these kinds of self-regarding or intrinsic arguments, it is likely to be as additional supporting arguments to strengthen the limitarian case beyond UUN and DA; almost certainly not replacement arguments. In so far as that is true, the necessity of endorsing a sufficientarian thesis, for the limitarian, is fairly secure (even if not a strict logical necessity).

But there is one other argument about why it might be required for limitarians to also endorse a sufficientarian thesis that I want to explore. It brings us back to the “circumstance of justice” that I suggested might have a role in securing the addition of a limitarian thesis for the sufficientarian. There is a related argument that can apply in this direction as well, for the limitarian to adopt a sufficientarian thesis.

Return to the basic idea that the “circumstances of justice” are meant to mark out the “conditions under which human cooperation is both possible and necessary.” What would make cooperation “necessary”? It could be read as a mere descriptive fact set by temporal and geographic cohabitation. On the other hand, one could argue that the most plausible interpretation of what is meant by cooperation in the circumstances of justice being “necessary” is already a normative phenomenon. On this account, the necessity is that there already exists an implied intolerability of at least some people falling below some standard that such cooperation is meant to correct. If true, it would suggest that inherent to the very idea of being in the circumstances of justice is a kernel of the sufficientarian logic. This result of such an interpretation of the circumstances of justice would, of course, bolster the position of the sufficientarian in the landscape of distributive justice, and be an important indicator of the foundational status of sufficientarian intuitions.38 But it would also have implications for limitarianism (and perhaps any theory of distributive justice).

To make it explicit: in order for limitarianism to hold, we have to be in the circumstances of justice. But if the very fact of being in those circumstances of justice entails a sufficientarian thesis (under some description, as the truth-maker of the claim that cooperation is “necessary”), then the limitarian also has to be committed to a sufficientarian thesis. It may not be precisely the same thesis as some sufficientarians might try to defend, but it seems sufficientarian in a non-trivial sense.

Again, I am trying to be ecumenical about the specific form of the sufficientarian and limitarian theses. However, parallel to the worry I raised in the other direction above, that might come at a cost. One might think that in order to count as meaningfully sufficientarian, the thesis would need more defined content or necessarily be a higher threshold than what could potentially fall out of this “circumstances of justice” argument.39 As before, I can’t fully consider this point, and don’t want too much to rest on this speculative argument. It may be too quick and easy to possibly be true, but its failure wouldn’t undermine the general case in favour of conjoining limitarianism with sufficientarianism. So, while it is certainly worth entertaining, we should be content to move from this broader section with a very strong argument for limitarians in favour of also endorsing a sufficientarian thesis, even if the case for a conceptual necessity on the basis of the circumstances of justice is not airtight (at least not for some specific and more robust interpretations of what the sufficientarian threshold would have to look like to count in the right way).

4. Distributive Justice and Multi-Threshold Views

I have attempted to argue in the previous two sect, first, that sufficientarians should also endorse a limitarian thesis, and second, that limitarians should also endorse a sufficientarian thesis. At a higher level of abstraction, this implies that each view should actually be a multi-threshold theory of distributive justice, consisting of both a sufficientarian threshold and a limitarian threshold. We can also refer to these as a “floor” threshold and a “ceiling” threshold, or a “lower” threshold and an “upper” threshold.

This multi-threshold structure is worth distinguishing from another kind of “multi-threshold” view that has surfaced in the sufficientarian literature. Robert Huseby has presented a sufficientarian view which also articulates two thresholds, what he calls a “minimal” and a “maximal” threshold. However, these function as two different kinds of sufficiency thresholds with more or less inclusive content. One highlights the importance of securing everyone’s basic needs, as a foundational threshold. The other highlights the importance of securing a state of contentment as a more involved demand of sufficientarian justice (Huseby 2010).40

For the purposes of this chapter, I am non-committal as to whether or not we should endorse these two sufficientarian thresholds, or whether there may be arguments for multiple limitarian thresholds where our reasons shift in character.41 The key takeaway is in the general structure; that there is good reason to think that sufficientarians and limitarians should each endorse at least two thresholds, one at the floor and one at the ceiling. Any additional thresholds, of Huseby’s variety or otherwise, can be put up for debate.42

Moreover, although this may sound strange, in particular contexts the lower threshold and the upper threshold might collapse into one another and share the same value. As I said above, it is not remarkable for sufficientarians to maintain that for some goods what counts as enough is equality. At the level of normative action-guidance the multi-threshold view in such contexts would be indistinguishable from the egalitarian, but preserve the modal flexibility across different possibility space where the thresholds intuitively should come apart.43

5. Distributive Thresholds and Deontic Statuses

In this section, I want to show why the multi-level threshold structure I have just articulated should actually be less surprising once we consider it in relation to other domains of normativity. In fact, once alerted to how neatly the core idea maps on to other very standard deontic conceptual language about rights, permissions, and duties, conjoining the idea of a sufficientarian and a limitarian threshold in a single view shouldn’t seem strange at all. Indeed, perhaps it should seem rather obvious.

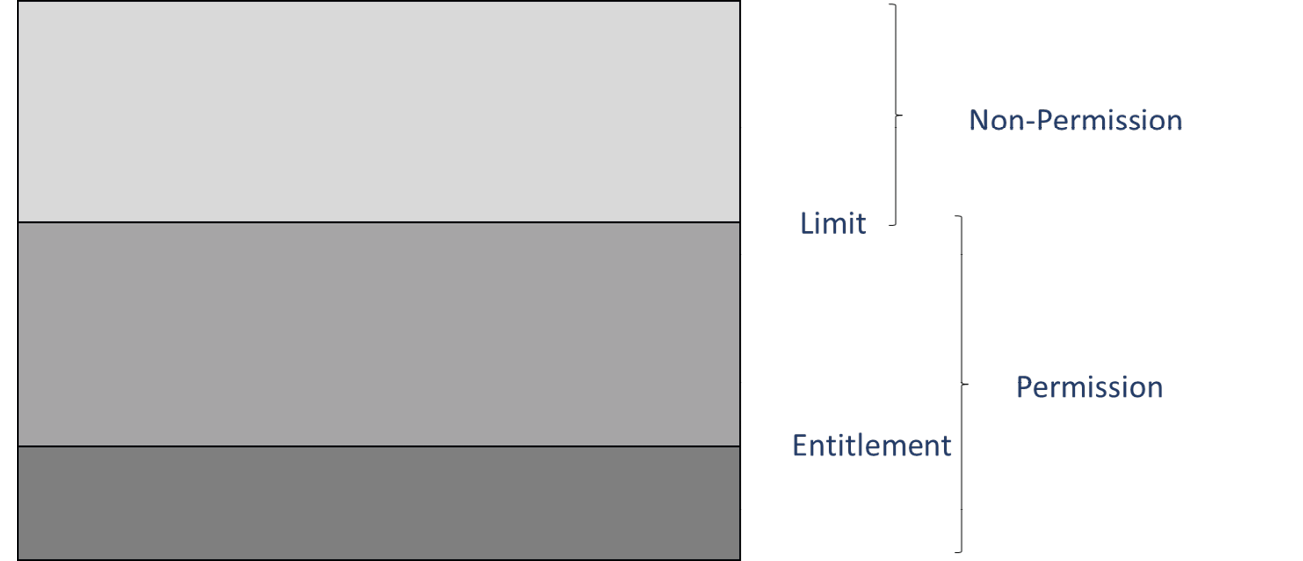

Triangulating across different normative language, the sufficiency threshold is essentially meant to indicate what people can claim as a matter of right or entitlement. The space between the sufficiency threshold and the limitarian threshold essentially indicates the range of permissible resource holdings that cannot be claimed as a matter of entitlement but which are also not wrong to have. And the limitarian threshold, as an upper limit on permissible resource holdings, is the point past which any such holdings are illegitimate. It is where permission runs out, and thus where wrongdoing begins and duties to disgorge come in to force.44

If we wanted to represent the conceptual space visually, we might have something like the following (Figure 1):

The structure inherent in the multi-threshold view is essentially the structure that undergirds all of our deontic discourse. Namely, it is one that marries rights or entitlements with permissions and non-permissions or prohibitions.45 For different purposes, one might want to interpret these three categories morally instead of politically. For instance, one might think that one is morally entitled to more or less than one is politically entitled to, or that the moral limits on resource holdings are more or less stringent than what is defensible or enforceable as a political limit. But regardless of the specific kind of deontic interpretation one wishes to give, what remains for the multi-threshold view is a very familiar structure. This should give us additional confidence that the outcome of endorsing a multi-threshold view, rather than being seen as strange or unique, should be welcomed as a sign of fluency in deontic discourse, of which distributive justice purports to be a part.

I should clarify one last point, before moving on to the final section of the chapter. Embracing this continuity between standard deontic language and the multi-threshold view is consistent with distinctions about varying “degrees of wrongness” or intra-category comparative prioritization. For instance, having a limitarian threshold doesn’t preclude judgments that it is more wrong to hoard a billion dollars than it is to hoard a million and one dollars, if the threshold were set at one million. The threshold simply indicates a shift in normative status from permission to non-permission. So, while both hoarders might be in violation of their duties, it is coherent to say that the billionaire is doing significantly worse. Indeed, part of the very explanation for why is the comparatively greater amount of other, more important normative values that could be satisfied with alternative usage of the billionaire’s surplus resources.

6. The Looming Question

My core ambition in this chapter has been to suggest that sufficientarians should endorse a limitarian thesis and limitarians should endorse a sufficientarian thesis, and thus both should be multi-threshold views. In some ways this leaves, of course, the biggest question still to be answered; how should we interpret the substantive, and therefore deontic, content of the thresholds? Where are they to be set? More than the mere structure, this is what is ultimately required to provide action guidance from a theory of distributive justice. I will not attempt to provide a convincing answer here, but by way of closing remarks, I want to offer a few thoughts toward that ultimate end.

First, as an important reminder, it is possible that different kinds of goods which are implicated as matters of concern in our theorizing about distributive justice may indeed, if pluralistic and irreducible, require discrete treatment when it comes to threshold setting.

Second, any adequate approach (or, ultimately, answer) to the question of threshold setting will need to involve high-bandwidth feedback between a range of foundational values and the relevant empirical context. For instance, we need to know the state of our collective resources and what is and is not attainable with them. My own view is that the limitarian threshold needs to be determined in relation to the sufficientarian threshold (see, e.g., Hickey 2021). So, in order to determine how high our distributive permissions go, we need to begin with what, at the low end, are plausibly specified as entitlements. I presume that will start with the most uncontroversial and minimalist proposals for entitlements, such as the concern for securing basic needs and subsistence. From there, we might extend to an expanded concern for securing a sphere of the goods of agency.46 Beyond that, we might perhaps move up another rung to an expanded concern for securing what Frankfurt (1987) or Huseby (2010) refer to as “contentment.” Beyond that still, we might perhaps ultimately extend to a concern for securing what Robeyns indicates in her deployment of the concept of “flourishing.”

There are inevitably robust arguments to be had about what plausibly constitutes an entitlement, and in turn how to specify what the limitarian threshold needs to be. However, one thing that does seem to be true is that the most troublesome conflicts do not begin to arise until we place the limitarian threshold low enough to start seriously cutting into individuals’ contentment or flourishing. As long as we are still in the business of cutting into mere luxuries of the wealthy, it isn’t plausible to think that their own entitlements could block redistribution towards the more basic entitlements of the worse off.

That said, in the real world, it may very well be that the most defensible upper limit is lower than we might think. It is possible that it could substantially cut into what we generally think of as permissible holdings or even entitlements, as part of our contentment or flourishing (see again Hickey 2021). In spite of real gains lifting millions out of abject poverty in recent years, the magnitude of suffering and urgent unmet needs around the globe is staggering. Put in terms of the deontic language just introduced, there is a virtually unending glut of the most basic rights and entitlements that are unfulfilled. Moreover, as we continue to address the cumulative costs of the pandemic, worsening climate change, deadly wars and conflicts, broader political unrest, etc., the prospects for further deterioration are high. Given the above, it might turn out that taking the moral equality of persons seriously will ultimately point to a lower upper limit than we may have imagined.

Moreover, this same set of facts may also reveal that what one is entitled (or permitted) to have may fall well short of what would actually be required for a flourishing life.47 Naturally, this depends on how minimalist one’s (personal or theoretical) conception of flourishing is. But it is safe to say that many visions outstrip what is likely to survive as a permissible distributive share when taking the scope of global basic needs seriously. Neither of these speculative thoughts is meant as a matter of principle, but rather a worried reflection on the fundamentally and unacceptably dire state of many billions of people around the globe who can all likely claim more plausible entitlements to distributive resources for basic needs than others can in service of providing the material conditions necessary for, say, contentment, flourishing, or luxury.

As with many philosophical projects, then, we are left with substantial questions. Defining the contours of the most plausible thresholds for any resulting multi-threshold view is chief among them. What I hope to have shown here, in arguing that sufficientarians should endorse a limitarian thesis and limitarians should endorse a sufficientarian thesis, is just that as they forge ahead in detailing the content of distributive justice, they should be looking in two directions, at (at least) two thresholds.

Acknowlegement

For helpful comments and discussion on earlier drafts of this chapter, I would like thank Ingrid Robeyns, Dick Timmer, and Fergus Green. Thanks also to audiences at the University of Bucharest and Princeton University for their valuable feedback. Part of this work was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 726153). It was also supported by the Climate Futures Initiative at Princeton University.

References

Axelsen, David and Lasse Nielsen. 2015. Sufficiency as Freedom from Duress, Journal of Political Philosophy, 23 (4), 406–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12048

Barry, Brian. 1989. Theories of Justice. Hemel-Hempstead: Harvester-Wheatsheaf.

Benbaji, Yitzak. 2005. The Doctrine of Sufficiency: A Defence, Utilitas, 17(3), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820805001676

Benbaji, Yitzak. 2006. Sufficiency or Priority? European Journal of Philosophy, 14(3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0378.2006.00228.x

Carey, Brian. 2020. Provisional Sufficientarianism: Distributive Feasibility in Non‐ideal Theory, The Journal of Value Inquiry, 54, 589–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10790-020-09732-7

Casal, Paula. 2007. Why Sufficiency Is Not Enough, Ethics, 117, 296–326. https://doi.org/10.1086/510692

Christiano, Thomas. 2012. Money in Politics. In: David Estlund (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 241–257.

Crisp, Roger. 2003a. Equality, Priority, and Compassion, Ethics, 113(4), 745–763. https://doi.org/10.1086/373954

Crisp, Roger. 2003b. Egalitarianism and Compassion, Ethics, 114(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1086/377088

Frankfurt, Harry. 1987. Equality as a Moral Ideal, Ethics, 98, 21–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2381290

Gough, Ian. 2017. Recomposing Consumption: Defining Necessities for Sustainable and Equitable Well-being, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 375 (Issue 2095): 20160379. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2016.0379

Hickey, Colin. 2021. Climate Change, Distributive Justice, and “Pre-Institutional” Limits on Resource Appropriation, European Journal of Philosophy, 29(1), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12569

Hope, Simon. 2010. The Circumstances of Justice, Hume Studies, 36(2), 125–148. http://doi.org/10.1353/hms.2010.0015

Hume, David. 2000. A Treatise of Human Nature (Ed. David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hume, David. 1998. An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (Ed. Tom L. Beauchamp). New York: Oxford University Press.

Huseby, Robert. 2010. Sufficiency: Restated and Defended, The Journal of Political Philosophy 18 (2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00338.x

Huseby, Robert. 2020. Sufficiency and the Threshold Question, The Journal of Ethics, 24, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-020-09321-7

Huseby, Robert. 2022. The Limits of Limitarianism, The Journal of Political Philosophy, 30(2), 230–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12274

Millward-Hopkins, Joel. 2022. Inequality can double the energy required to secure universal decent living, Nature Communications, 13, 5028. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32729-8

Nielsen, Lasse. 2019. Sufficiency and Satiable Values, Journal of Applied Philosophy, 36(5), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12364

Nussbaum, Martha. 2006. Frontiers of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

O’Neill, Daniel, et al. 2018. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 1, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Raworth, Kate. 2017. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. London: Random House.

Robeyns, Ingrid. 2017. Having Too Much. In: J. Knight & M. Schwartzberg (Eds). NOMOS LVI: Wealth. Yearbook of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy. New York: New York University Press, pp. 1–44.

Robeyns, Ingrid. 2019. What, If Anything, Is Wrong with Extreme Wealth? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 20 (3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1633734

Robeyns, Ingrid. 2022. Why Limitarianism? The Journal of Political Philosophy, 30(2), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12275

Shields, Liam. 2012. The Prospects for Sufficientarianism, Utilitas, 14, 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820811000392

Shields, Liam. 2016. Just Enough: Sufficiency as a Demand of Justice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Tebble, A. J. 2020. On the Circumstances of Justice, European Journal of Political Theory, 19(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885116664191

Temkin, Larry. 2003. Egalitarianism Defended, Ethics, 113(4), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1086/373955

Timmer, Dick. 2021a. Limitarianism: Pattern, Principle, or Presumption? Journal of Applied Philosophy, 38(5), 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12502

Timmer, Dick. 2021b. Thresholds in Distributive Justice, Utilitas, 33(4), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820821000194

Timmer, Dick. 2022. Justice, Thresholds, and the Three Claims of Sufficientarianism, The Journal of Political Philosophy, 30(3), 298–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12258

Vanderschraaf, Peter. 2006. The Circumstances of Justice. Politics, Philosophy & Economics 5(3), 321–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X06068303

Volacu, Alexandru and Adelin Dumitru. 2019. Assessing Non-intrinsic Limitarianism, Philosophia, 47, 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-018-9966-9

Wiedmann, Thomas, et al. 2020. Scientists’ warning on affluence, Nature Communications, 11, 3107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y

Zwarthoed, Danielle. 2018. Autonomy-Based Reasons for Limitarianism, Ethical Theory Moral Practice, 21, 1181–1204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-018-9958-7

1 Below I will discuss some of the arguments offered in favour of limitarianism, and throughout help to clarify its intended import, given that it is a less familiar view than sufficientarianism. We can begin, however, simply with this wide and intuitive understanding of the kind of functional role it aims to play.

2 Robeyns (2017, p. 38) foreshadows the possibility of an eventual investigation of this kind, writing, “One particular question that requires attention is how limitarianism relates to the understanding of sufficiency in terms of a shift in the reasons we give for caring about benefits below and above the threshold, rather than the more dominant understanding of simply caring that everyone has enough.” Introducing limitarianism means we have to consider how resources above the wealth limit relate to moral claims, not only of those below the sufficiency threshold, but also potentially those in the intermediate space above it but below the wealth limit. I will discuss this further below.

3 I cannot be completely ecumenical. For instance, if someone insists on holding a strong version of the “negative thesis” of sufficientarianism, as discussed below, and refuses to accept any movement towards the non-ideal discussion, they may not be convinced.

4 I am borrowing here from Liam Shields’ (2012, p. 106) formulation. Casal’s original statement of the positive thesis is that “it is important that people live above a certain threshold, free from deprivation.” See (2007, pp. 298–299).

5 This may be putting it slightly too strongly, as even Roger Crisp’s (2003a) well-known defense of the negative thesis does allow that there may be some aggregative criteria (to produce more rather than less, even if you don’t care about the distribution).

6 Frankfurt is, of course, mostly concerned with trying to show that we shouldn’t exaggerate the importance of economic equality, which is exactly my point; that we shouldn’t take the surface grammar of statements meant to criticize egalitarianism as forming some immutable core of sufficientarianism that would block limitarianism.

7 Shields does add, however, that “wholly aggregative criteria may apply” (2012, p. 103). See also David Axelsen and Lasse Nielsen’s (2015, p. 409) statement “once people are free from [significant pressure against succeeding in central areas of human life], inequalities are irrelevant from the point of view of justice.”

8 This point is made particularly clear in Robeyns (2022). In addition to the other arguments we will discuss below, Robeyns (2019, pp. 258–260) offers an explicitly “ecological argument” for limitarianism in the context of climate change, using wealth limits to fund mitigation and adaptation efforts. See also, e.g., Millward-Hopkins (2022) and Wiedmann et al. (2020).

9 For a specifically non-ideal argument for sufficientarianism, see Carey (2020).

10 I do not think doing so is required, but if readers feel otherwise, my overall thesis can be restricted in scope or pitched exclusively at the level of institutional design rather than fundamental values (to bracket the pure ideal-theoretic sufficientarian) and still be an interesting development.

11 Shields entertains that a different kind of thesis could, together with the positive thesis, help form the core of sufficientarianism, in particular a “diminution thesis” which states that “once people have secured enough our reasons to benefit them further are weaker” (2012, p. 107). He rejects this because he thinks it would not sufficiently distinguish the view from prioritarianism. I am not sure how strong of a desiderata this is, or whether there are other theoretical or pragmatic considerations that would adequately mark out this kind of sufficientarianism. It may be that being analytically distinct (rather than usefully separable, but ultimately inter-definable/translatable) is not a decisive point one way or another.

12 Correspondingly, once we drop the negative thesis for sufficientarianism, the standard egalitarian’s motivation for denying the core sufficientarian thesis decreases markedly. They have good reason to endorse the idea that the reasons are particularly weighty for having enough of certain goods, particularly in contexts when equality is not possible. They simply will want to maintain an additional claim about the distinctive value, and sometimes-normative-difference-maker of equality.

13 See particularly Huseby’s Section 3.

14 It does not actually do so, and would take an additional premise, but Huseby himself suggests it is “supported” by Robeyns’ limitarianism. Ibid., p. 211.

15 Which, as I mentioned above, I don’t think is required, even though there is good reason to.

16 Although it might be an interesting feature that, if this requires abandoning the strong negative thesis, the reason would be because of limitarianism.

17 Unless the threshold is interpreted so high as to make the difference plausibly meaningless. But doing so would betray the idea of sufficiency as a theory about a social minimum and do significantly more violence to the core idea than dropping the strong negative thesis.

18 Obviously, these figures are just meant schematically, not to imply the ultimate commitments of the sufficientarian or limitarian.

19 For additional considerations defending thresholds (whether between needs and wants, or regarding personhood, luxuries, or pain) see Benbaji (2005; 2006).

20 But a similar point can be made of forms of sufficientarianism that accept either satiable values or satiable principles. See Nielsen (2019).

21 Thanks to Dick Timmer for discussions on this point. See also his discussions in Timmer (2021b and 2022).

22 See also Hume (2000, 3.2.2.2–3, 3.2.2.16) and Hume (1998, 3.1.12, 3.1.18, 3.8–9). There are debates about what exactly Rawls adds or changes from Hume. See, e.g., Hope (2010). For broader discussions, see also Barry (1989), Nussbaum (2006), Vanderschraaf (2006), and Tebble (2020).

23 See Rawls’ full presentation at (1999, pp. 109–110). Hume thought that either extreme “abundance” or scarcity/“necessity” (on the environmental side), or perfect “moderation and humanity” or “rapaciousness and malice” (on the psychological side) would make justice useless, (1998, 9 3.1.12). It is common, then, to summarize the circumstances of justice as circumstances of limited altruism and moderate scarcity of resources.

24 Naturally, these might be affected somewhat by technology, efficiency, etc., which I will say more about below.

25 While I won’t pursue the point here, as it would take us too far into the weeds about the concept and logic of normativity, it is worth entertaining whether simply conjoining the facts of finite resources with a demonstration that our collective desires outstrip their possibilities is enough to provide a sufficiently normative thesis insofar as how staying within the confines of finite physical resources will be received psychologically.

26 This is, indeed, one of the reasons why Robeyns defends limitarianism. See (2019, pp. 258–260).

27 In fact, I discuss below some reasons why we might ultimately think that individual limits are actually lower than the point of flourishing.

28 I will say something below about the possibility that the general structural form of a limitarian thesis that might fall out of this isn’t substantive enough to count as meaningfully limitarian.

29 The status of this claim might depend on exactly how global the scope of principles of distributive justice is. It is more plausible that some individual societies might be able to eliminate, within their ranks, extreme want and thereby “moderate scarcity.” Often, of course, affluent societies that might look closer to having eliminated moderate scarcity simply offload the costs and hide the negative externalities elsewhere. That is a common motivation for wanting a picture of distributive justice that is global in scope. Moreover, any of this depends on how precisely we interpret what “moderate scarcity” consists in. All of that said, I am confident enough in the case for a global scope of justice that if my argument here is restricted to global views, I would not be upset. In my view, that would merely amount to a restriction to the right set of views anyway.

30 That is, it might position us to revise upward our judgments about what justice demands to situate us back in a newly conceived context of moderate scarcity; a rung higher up on the ladder.

31 Crisp himself, in responding to criticisms from Larry Temkin, makes clear that he is thinking of this case not as possible states of affairs of some rich people in our world, but a totally independent, fully-described possible world. See Crisp (2003b, p. 121). See also Temkin (2003).

32 See Robeyns (2022), responding to Huseby (2022) in a dynamic that played out in just this manner.

33 Indeed, some might worry it proves too much because it would entail that any view of distributive justice should embrace limitarianism. This, of course, isn’t an outcome that I’d be unhappy with. I have focused on the comparison because the views are seen as mirror images of each other.

34 In Robeyns’ original formulation, which places the limitarian threshold at riches above those required for flourishing, she claims that there is actually no moral cost to such redistribution, “since surplus money does not contribute to people’s flourishing, it has zero moral weight, and it would be unreasonable to reject the principle that we ought to use that money to meet these urgent unmet needs.” (p. 12) One need not agree with the idea that they have zero moral weight to feel the force of the comparative claim that holding on to such resources would be impermissible and can legitimately be redistributed.

35 As hinted above, a third argument is that such limits are required to stave off environmental catastrophe owing to the disproportionate and unsustainable consumption of the rich. See again Robeyns (2019), pp. 258–260. See also Hickey (2021). For other, more methodological, ways of defending limitarianism drawing on this basis, see Timmer (2021a).

36 An implication of the shift thesis is perhaps somewhat less explicit, but in the very act of singling out urgent unmet needs the argument seems to be implying that the reasons we have for eliminating those are particularly strong and different from other kinds of reasons one could claim for redistribution. While meeting unmet urgent needs might not signify yet that someone has “enough,” the unique way in which it stands as the justification of the limitarian threshold suggests the logic of sufficientarian and shift-based thinking.

37 Zwarthoed (2018), for instance suggests extreme wealth might hinder the development of deliberative capacities, facilitate problematic adaptive preference formation, erode one’s capacity to revise their conception of the good (because it habituates one to an expensive lifestyle, or irresistibly triggers fears of status loss), or be incompatible with an important form of transparency with one’s own values. Though one could potentially transform this argument into a “sufficientarian” form by appealing to a sufficient threshold of autonomy that everyone is entitled to, and suggesting that having excess wealth pushes people below that threshold. Doing so would bolster the necessity claim by including these self-regarding reasons for limitarianism in a sufficientarian logic.

38 Again, some might worry that this proves too much because it would entail that every theory of distributive justice should also be sufficientarian. For me, this is a welcome outcome, and it is interesting that it would emerge from a discussion about its relation to limitarianism.

39 Even if many sufficientarians focus on the importance for justice of securing “basic needs” for all, which might be minimal enough for this argument to work, it might not, for instance, establish the threshold of contentment that Frankfurt discusses, or the threshold of enjoying “freedom from duress” that Axelsen and Nielsen defend (2015). This result, of course, would not rule out the limitarian adopting one of these richer sufficientarian thresholds, it just might not fall out as necessary from this ‘circumstances of justice’ argument. It may fall out of UUN or DA.

40 These are different than the two thresholds mentioned above during the discussion of the positive and negative theses from Huseby’s more recent work (2020).

41 If we proliferate too many thresholds there is a risk of diluting the meaning of a threshold and veering closer to general prioritarian reasoning, but I don’t think that is a particular risk here.

42 For instance, again, like those in Benbaji (2005; 2006).

43 I take it that this potential to capture egalitarian intuitions, without sharing the same vulnerabilities, is a theoretical advantage.

44 In a different literature and for slightly different purposes, Ian Gough (2017) has described an analogous idea as a “consumption corridor” as the range “between minimum standards, allowing every individual to live a good life, and maximum standards, ensuring a limit on every individual’s use of natural and social resources in order to guarantee a good life for others in the present and in the future.” See also Raworth (2017).

45 Of course, there are other ways to justify non-permissions, like if someone steals from another, so I don’t want to imply that this simple representation covers all of the deontic landscape.

46 Perhaps like the “autonomy-catering” sufficientarian threshold proposed by Axelsen and Nielsen (2015).

47 On the difficulties of securing a good life for all within planetary boundaries, see O’Neill et al. (2018).