6. Taxidermy and Natural History Dioramas

© 2023 Joanna Page, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0339.06

Many writers of late-nineteenth-century taxidermy manuals traced their art back to ancient times, while taking pride in more recent techniques that allowed them to preserve animals in ever more life-like attitudes.1 Such manuals were much in demand, as William Temple Hornaday noted in his own contribution to the genre, both by “eager young naturalists” pursuing zoology as a hobby and by professional collectors supplying a raft of new science museums.2 For Hornaday, a pioneering member of the wildlife conservation movement in the United States, the imperative to build up zoological collections stemmed from “the rapid and alarming destruction of all forms of wild animal life which is now going on furiously throughout the entire world.”3 The spectacular and costly habitat dioramas that were commissioned for museums in North America and Europe between 1880 and 1930 exhibited groups of taxidermied animals in theatrical scenes that evoked, as faithfully as possible, the appearance of savannas, jungles, or other natural environments. They were designed to give the urban public a rudimentary understanding of ecosystems and to instill in them “a deep respect for nature, or what might be described more accurately as a deep longing for a wilderness at the edge of existence.”4 These displays thus combined naturalist precision with a Romantic nostalgia for the primitive, for what might lie beyond the limits of culture.

With time, taxidermy came to embody a more contradictory and questionable set of meanings. It became impossible to ignore the imperialist discourses and practices that underpinned the hunting, collecting, and ordering of animal life from other regions of the world. The fact that early conservationists were often also major advocates of big-game hunting meant that the preservation of wild nature for which they campaigned was also a defence of the kind of masculinist values associated with sporting prowess. Donna Haraway’s influential account of early-twentieth-century dioramas in New York’s American Museum of Natural History locates taxidermy at the heart of the museum’s attempts to arrest the decay of (patriarchal) civilization and to preserve “imperialist, capitalist, and white culture” against the threat of decadence.5 Objections to taxidermy have also highlighted the cruelty to animals often involved in its practices. As a highly ambiguous object, the taxidermied animal presents us both with the simulation of life and the materiality of death. Zoe Hughes draws attention to the processes of disavowal at work as taxidermy “is encountered as animal material, harkens back to the animal, but erases the violence in between—the death, skinning, stretching, and sewing.”6

More recently, artists have sought to reclaim the practice of taxidermy, either to confront its role in a history of animal objectification or to repurpose it for other aims. Their more critical or creative approaches have been described as “botched taxidermy,”7 “rogue taxidermy”8 or “speculative taxidermy.”9 While some animal studies scholars reject outright the use of animal skins in art on the basis that they represent a gesture of human supremacy over animals, others have found, as Giovanni Aloi suggests, that “the new and often uncanny presence of this medium in contemporary art can propose critically productive opportunities to rethink human/animal relations.”10 In the work of Antonio Becerro (Chile), Vitor Mizael (Brazil), and Berenice Olmedo (Mexico), for example, taxidermy has been used to draw attention to the neglect, abuse, and slaughter of stray dogs in urban centres. Contemporary approaches to taxidermy may also facilitate a (reflexive) questioning of the exhibition practices of natural history museums, while promoting alternative narratives about ecology and the environment. One or both of these aims are central to the works presented in this chapter by Daniel Malva (Brazil), Adriana Bustos (Argentina), Pablo La Padula (Argentina), Rodrigo Arteaga (Chile), and Walmor Corrêa (Brazil).

Of these artists, only Corrêa deploys taxidermy techniques directly, although he chooses to work with specimens that have already been preserved. Malva photographs taxidermy animals and insects; Bustos intrudes into a diorama in a performance captured on video; La Padula and Arteaga create interventions with taxidermied animals in natural history collections and dioramas in museum settings. All five artists deconstruct the illusions of realism that devices of display so carefully generate and demonstrate how taxidermy objects and practices can be repurposed to create a critical dialogue with Eurocentric conceptions of the natural world or, more specifically, the role played by natural history in the formation of national and global imaginaries. These artists create “afterlives” for taxidermy animals that invite us to consider shifting entanglements between nature and culture or between science and popular myth; they also explore how taxidermy may be used to restore animal agency or to create alternative narratives for a post-anthropocentric era.

Animal Spectrality in Daniel Malva’s Natural History Museum

In the resurgence of taxidermy that has become evident in art over recent decades, epitomized in the work of Damien Hirst and Polly Morgan, Amanda Boetzkes finds an interest in communicating the “existential pathos of animal lives” lived in subordination. This is combined, however, with an attempt “to expose the particularity of those animal bodies and overturn the predominant aesthetic regime by which humans conceal animals in anthropocentric systems of signification.”11 This dual emphasis—registering a loss of animal agency while seeking, in part, to return it—is also evident in Daniel Malva’s Natural History Museum (2009–2014).12 The series comprises ninety-six photographs of exhibits from small and lesser-known museums and other collections in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, including insects, taxidermied animals, skeletons, and specimens in jars of formaldehyde. Boasting an elephant foetus, a severed human hand, and a tarantula, Malva’s collection yields a frisson of the macabre. His inclusion of preserved human organs and tissues points to the mortality that we share with nonhuman animals as a result of our (often disavowed) animality. It also sets into relief the (often arbitrary) divisions that Western societies have erected between humans and other animals, which have justified—and continue to justify—the capture and killing of animals and the preservation of their skins and organs.

Most of Malva’s photographs are not post-processed in any way, although they are scaled to reproduce the dimensions of the original organs and organisms. Malva hacked into his digital camera to insert a software programme that prevented the camera from making its usual corrections to the image’s exposure or colour. In other respects, however, the images depart from naturalism. As part of ongoing experiments with the construction of homemade lenses, Malva created a lens for this series from the lid of a shampoo bottle, which—in addition to the software hack—gives the images a cloudy, faded appearance. These ghostly apparitions give the exhibition an elegiac tone, as if it were a memorial to a series of extinct species, living only in our dreams or memories, or confined to the archives that have so exhaustively collected and classified them. Indeed, some of the specimens photographed here, together with the museums that housed them, no longer exist.13 Photography is perhaps the medium that most evocatively connects loss with the desire to preserve, serving as a memento or memorial that fixes the dead in its living past. For both Barthes and Sontag the photograph is always an “emanation” of a past reality, a trace of a material existence, a vestige of something now absent.14 In the uncertain outlines and the vaporous textures of Malva’s images, this “emanation” acquires a mystical character, taking on something of the viscous, luminous quality of ectoplasm, or the eerie transparency of spirits “captured” in nineteenth-century photographs.

Malva’s choice of lens suggests the extent to which we view the natural world through the prism of industrialization and mass production, while simultaneously allowing him to reject the naturalism of digital photography and the hypervisibility of contemporary nature documentaries. These animals are doubly removed from their original habitat, having been captured once for inclusion in a scientific collection and again in photographs for display in an art gallery. Their representation here draws attention to the processes of drying, stuffing, embalming, mounting, and pinning through which they have already been preserved and displayed (see Figs 6.1 and 6.2). For Malva, “era bem importante mostrar que essas peças não eram vivas” (it was very important to show that these exhibits were not alive).15 For this reason, many of the photographs show the labels, display stands, and glass jars that contain and explain the objects in a museum context. Malva’s images also demonstrate that the various techniques and compounds used to “fix” tissues and animals in a life-like state only slow down the process of decay rather than halting it altogether. The caiman’s heart (see Fig. 6.3, far left) is not naturally a different colour from those of the mammals with which it is displayed, but over time it has lost its pinkness. The photographs capture the decomposition of some of the tissues suspended in formaldehyde. Human handling of the objects has also caused damage: some of the taxidermied animals and insects have parts that are broken, twisted, or scratched.

Fig. 6.1 Daniel Malva, Mandrillus Sphinx, photograph from Natural History Museum (2013). 80 x 53.3 cm.

Fig. 6.2 Daniel Malva, Elephas maximus: fetus, photograph from Natural History Museum (2009). 30 x 20 cm.

Fig. 6.3 Daniel Malva, series of photographs of hearts, from Natural History Museum (from left to right): Caiman Latirostris, Equus Caballus, Homo Sapiens, Chrysocyon Brachyurus, Canis Lupus-Familiaris, Panthera Leo. 30 x 20 cm. As exhibited in a solo show entitled OJardim, Galeria Mezanino, São Paulo, Brazil, 2017 (photograph by the artist).

Boetzkes argues that “the persistent appearance of dead animal bodies in contemporary art’s revival of taxidermy nevertheless signals a disruption of the way in which humans imagine animals in a fundamental state of quiescence.”16 Malva’s photographs testify to the subordination of nonhuman animals, made perpetually available to our gaze through taxidermy, but they also undermine it through the use of portraiture, a genre usually reserved for human subjects. In many of his photographs it is possible to see the creases of a white sheet held up behind the animal, in order to separate it from the other taxidermy objects on display in the museum. This isolation, against a plain background, emphasizes the loss of the habitat from which the animal has been torn. But by photographing animals in this way, Malva returns to them an individuality that is lost in the natural history museum, in which they serve as exemplars of different species.

In many ways, however, the Natural History Museum encourages us to perceive characteristics that are shared across all species. The distancing effect achieved in Malva’s images reduces the differences between one specimen and the next, making their particularities less distinct. In a series of photographs of preserved hearts, for example, exhibited alongside each other, the resemblances are much more striking than the disparities. Malva includes a human heart alongside those of a caiman, horse, a maned wolf, a dog, and a lion (see Fig. 6.3 above). The human specimen is slightly smaller, but otherwise very similar in its shape, its colour, and the distribution of its pale pink coronary arteries, branching across the surface of the heart. Even the image of a whale heart usually exhibited near the series—an impressive 80x80 cm in size—bears a striking morphological resemblance to the others. These arresting correlations remind us that “on a biological level, we are all one and the same, the same material, the same mortal flesh.”17

Malva considers that what unites his many different photographic projects—which include studies based on dental x-rays, skulls, teeth, and body parts in formaldehyde from a human anatomy collection—is “o tema da morte, porque eu acho que a gente fecha os olhos para ela” (the theme of death, because I find that people close their eyes to it).18 Akira Mizuta Lippit claims that “No longer a sign of nature’s abundance, animals now inspire a sense of panic for the earth’s dwindling resources.” They take on a spectral form, never entirely vanishing but existing in “a state of perpetual vanishing.”19 In photographing taxidermied animals, Malva’s Natural History Museum captures this liminal existence, this extinction-in-progress. If the great European natural history collections were built on possession, Malva’s signifies loss and decay. Far from representing humanity’s subordination of the natural world, Malva’s photographed taxidermy speaks to us, not only of the silent extinctions of animals all around us, but of our own inevitable subjection to the most basic law of nature, death; perhaps even of our own extinction to come.

Paisajes del alma and the Diorama as a Regime of Visibility and Possession

Paisajes del alma (Landscapes of the Soul, 2011) is a collaboration between the Argentine artist Adriana Bustos and the German writer Sabine Küchler. It is a video of a performance that took place in a diorama constructed in 1990 by the Museo de Ciencias Naturales in Salta, in the north of Argentina.20 Before visiting the museum, both Küchler and Bustos had taken part in a two-month expedition to the Yungas forest near Salta, funded by the Goethe Institute. The video begins with still close-ups of some of the taxidermied animals that form part of the museum’s Yungas diorama, before opening out to a view of the whole scene. The images are overlaid with Küchler’s voice reading a passage from her book Was ich im Wald in Argentinien sah (2010), in which she relates her journey through the forest and a visit to the museum itself. Bustos enters the diorama to sit on a stool amid the ferns (Fig. 6.4), reading aloud from the book, although the voice we continue to hear is, at first, still Küchler’s. As Küchler’s text concludes, the final shot cuts to a view of the diorama with an empty stool.

Fig. 6.4 Still from video produced by Adriana Bustos, Paisajes del alma (2011). Video available at https://vimeo.com/688169765

The use of three languages in Paisajes del alma—the German voice-over, the Spanish translation read by Bustos that occasionally intrudes only to cede again to the German, together with the obligatory English subtitles, the lingua franca of science today—alludes to the (neo)colonial dynamics that have shaped natural history in Argentina. As Bustos explains, the nineteenth-century nation imagined and constructed by Sarmiento required the employment of a considerable number of German naturalists, who came to organize the nation’s knowledge of its flora and fauna, with little or no reference to local knowledges.21

Paisajes del alma contrasts the wildness of the Yungas with its domesticated, fictionalized version in the museum and reflects on the relationship, real and imagined, of humans with a forest that is so thick with vegetation that it is practically impenetrable. Küchler’s jungle is a chaotic battle scene, in which trees are described as wounded, twisted, and disfigured, ravaged by wind and fire. They are “desperate” and “exhausted” by the struggle to climb through a tangled mess of rotting branches to reach the light. With every attempt she and her companions make to open up a path, the jungle closes back around them: no trace of their presence would remain by the following day. In the circumstances, Bustos – who was the photographer on the expedition – suggested a trip to the Museo de Ciencias Naturales in Salta. There, Küchler writes, the animals were gathered, as if awaiting their visit. Her depiction of the Yungas forest contrasts with the sedate, manicured arrangement of the diorama, in which trees and plants give way courteously to render the animals fully available to our view and to allow us to appreciate the horizon vanishing into the distance on the customary painted backdrop. As Haraway writes of the African Hall dioramas in the American Museum of Natural History, “No visitor to a merely physical Africa could see these animals. This is a spiritual vision made possible only by their death and literal re-presentation. Only then could the essence of their life be present.”22 The diorama is thus a counter-jungle, a representation of animals that humans could never access in reality: an encounter only made possible through the death of those animals.

Aloi observes that the dioramas that became popular in natural history museums toward the end of the nineteenth century “excluded man from the unspoiled, deep nature” they depicted.23 Haraway also argues that the technology of the diorama both reproduces the innocence and purity of nature, “imagined to be without technology, to be the object of vision,” and, at the same time, the separation of man from nature: “Man is not in nature partly because he is not seen, is not the spectacle.”24 In Paisajes del alma, the incongruous presence of Bustos in the carefully arranged scene exposes the inherently performative nature of the natural history diorama, transforming it from a window onto the natural world into a theatrical stage. Her entrance onstage disrupts the false vision of an untouched nature, and turns the animals and plants into mere props or minor characters of a drama that is ultimately a projection of human interests and desires. Indeed, in the final line of Küchler’s text, the photographer explains that she loves the museum because “it tells us so much about the human being.”

Paisajes del alma also exposes another fiction often encoded in dioramas, that of the timelessness of nature. Exhibition, as Haraway reminds us, is “a practice to produce permanence, to arrest decay.”25 The emphasis in Paisajes del alma on the gradual decay of the diorama acts to historicize the vision of nature it conveys and to attenuate its effects of realism. In Küchler’s description, the diorama’s preservation of a timeless nature had already begun to show its age. She explains that, with time, the bright colours of the painted backdrop had dulled, fading to the pastel shades of a little girl’s bedroom and lending an agreeable tone to the scene. She notes that the taxidermied animals’ fur was thinning and that dust had settled like ash on the birds’ feathers. Like the diorama itself, the vibrant ecosystem it depicts is also in decline, as a result of uncontrolled deforestation. The yaguareté (jaguar) shown in the video’s first shot is a critically endangered species whose population in Argentina has drastically reduced since the beginning of the twentieth century, largely due to the destruction of its habitat and to hunting, in order to protect grazing cattle. In recent years, it has been estimated that fewer than 250 jaguars are in existence in the country, and that ninety-five percent of their habitat has been destroyed.26 If the Yungas diorama showcases the region’s diversity, the many animals it includes either remain difficult for humans to access or are fast disappearing as a result of the human exploitation of the forest. Although many dioramas are intended to convey the importance of conserving wild nature, the idyllic vision presented here of a healthy, biodiverse biome arguably perpetuates the fiction that the natural world is readily visible and available for human observation and ignores the reality of our destruction of it.

Paisajes del alma thus brings to the forefront how animal bodies have been expended in order to tell human stories. Both taxidermy and the diorama are illusions that conceal the killing that brought them into being and the everyday destruction that continues to threaten animals and their habitats. Küchler’s words and Bustos’s performance undermine the effect of permanence created by these technologies of preservation and exhibition, reinserting them in a broader history of habitat loss and extinction.

Expanded Dioramas in the Work of Rodrigo Arteaga

For the exhibition This Path, One Time, Long Ago (2018), Rodrigo Arteaga made a series of interventions in dioramas created for The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent, UK.27 Although these dioramas are simpler in execution than some of those created for the great science museums in the early twentieth century, they share several of their features. Animal mounts in life-like poses are set among three-dimensional reproductions of rocks, reeds, and ponds in the foreground that appear to merge into a broader landscape, painted on the back wall using techniques that create an illusion of depth and continuity. Despite their commitment to scientific accuracy and naturalism, dioramas make extensive use of elements appropriated from the theatrical arts, such as an enclosed stage, complex lighting designs, and the use of (frozen) gestures and the spatial arrangement of figures to suggest relationships and evolving narratives. While appearing to present a mere window onto the natural world, such dioramas effectively cast animals as “actors in a morality play on the stage of nature,” as Haraway puts it.28

What dioramas of the early twentieth century usually portrayed was an Edenic scene of ecological balance and “an immaculate vision of nature uncontaminated by human presence.”29 Arteaga’s interventions into the Potteries Museum dioramas were to disrupt these narratives entirely, by introducing artefacts of human craftmanship into natural scenes and shattering any illusion of realism in staging. In Wetland, painted ceramic ducks are placed next to taxidermied ones, while in Moorland, the overhead lights have become dramatically detached from the ceiling, hanging down amid stray cables (Fig. 6.5). Arteaga defies an important convention of diorama design, according to which the animals featured should show no awareness of human activity, much less be seen to respond to the violence of their hunters. Here, instead, the stag in Moorland appears to be startled by the falling lights; in Wetland, a taxidermied duck and its ceramic counterpart gaze at each other with mutual curiosity.

Fig. 6.5 Installation view of Rodrigo Arteaga, Moorland from This Path, One Time, Long Ago (2018). Potteries Museum & Art Gallery PMAG, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom (photograph by the artist).

In exposing the artifice of diorama design and inserting objects of human culture, Arteaga deconstructs the illusion of a pure, untouched nature. He reminds us that the “resurrection” of animals through taxidermy is always a rebirth into a cultural world in which they will be recast and resignified according to human values, conscripted to serve a particular vision of nature. Here, there can be no release from that imposition of human meaning but there can be a making-multiple of meanings that might oppose or complicate human purposes. If a taxidermy animal is rendered fully available for shaping and arranging by human artists and collectors, Arteaga’s animals seem to retain a possible agency and a capacity to participate in encounters that were not initially planned by the diorama designer. At the very least, the ambiguity of the taxidermy object is greatly amplified by these intrusions and the enmeshing of truth and fiction.

This Path, One Time, Long Ago proposes a “cross-pollination” of different sections within the museum that have conventionally been kept separate.30 The pottery ducks are intruders from the museum’s vast ceramics collection, infiltrating into the Natural Sciences dioramas, while animal mounts from the dioramas become interlopers in the Local History tableaux. In one of these, The Victorian House (Fig. 6.6), a hare sits on its haunches on the kitchen table while an owl presides over the room from a high shelf; the worn interior of The Pub has been overrun with birds and foxes. These mutual intrusions challenge distinctions between nature and culture, wildness and civilization, and animal and human. It is these distinctions that have underpinned efforts in both conservation and eugenics, two closely related philosophies that Haraway identifies as powerful forces shaping both research and exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History between 1890 and 1930. Arteaga’s work illustrates something of the contradictory practices that Bruno Latour finds to be constitutive of modernity: on the one hand, a “work of purification” that separates humans from nonhumans, and on the other, the proliferating creation of “hybrids of nature and culture.”31 As Arteaga explains, the intervention was designed to capture the radical “instability” of our perceived relations with the nonhuman world.32

Fig. 6.6 Installation view of Rodrigo Arteaga, The Victorian House from This Path, One Time, Long Ago (2018). Potteries Museum & Art Gallery PMAG, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom (photograph by the artist).

This idea is also very effectively explored in the “expanded diorama” Arteaga had created for his residency at the AirSpace Gallery the year before.33 The diorama was presented as if it were still under construction, or perhaps in the process of being dismantled, and there was no division between exhibition space and viewing space. Museum visitors could wander at will between a half-unrolled strip of plastic turf, a swan still wrapped in protective polythene, and numerous animal mounts with their storage identification labels attached (see Fig. 6.7). As well as thoroughly deconstructing the artifices central to diorama design, which sought to create a seamless vision of a single landscape, Arteaga’s expanded diorama thus created the possibility of a mutual invasion of spaces. Gallerygoers were able to enter the traditionally bound space of the diorama, and—conversely—taxidermy animals were placed in spaces of the museum that are normally reserved for humans. If the panoptic spatial relations of the conventional diorama tend to reinforce a sense of visual mastery and superiority, here viewers had to navigate a shared space in which they were the apparent object of multiple gazes, as birds stared down from the gallery’s ceiling lights and mice peered over high ledges. The original habitat dioramas embodied the “community concept” developed by Karl Möbius, whose emphasis on the relationships between animals, and between animals and their environment, was extremely influential in shaping late-nineteenth-century approaches to biology and ecology.34 By expanding the diorama beyond its usual spatial boundaries, Arteaga alludes to the complexity of relations in more-than-human communities, a subject of growing urgency in the twenty-first century.

Fig. 6.7 Installation view of Rodrigo Arteaga, Natural Selection (2017). AirSpace Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom (photograph by the artist).

Arteaga’s works also challenge the qualities of stasis, permanence, and transcendence that are quintessential to the diorama’s aesthetic and its narratives about nature. Natural Selection does this by extending the temporality of the diorama to include scenes of the preparation and storage that precede or follow an exhibition. Similarly, with its deliberately collapsed lighting systems, This Path, One Time, Long Ago suggests the decay of the museum’s fabric over time. Such techniques emerge from Arteaga’s understanding that “the tradition of the diorama is a place of contingency,”35 and that it may, in artistic remakings, chart the perceptual and conceptual reorganizations of our relationship with nature. The many different works and objects that make up the Natural Selection exhibition include mobile sculptures, in which a taxidermy mannequin is joined by organic and inorganic objects found on a brownfield site near the museum, all of which were suspended together in an ever-shifting spatial relationship. These continually moving constellations capture both our contemporary sense of the fragile balance of ecosystems and the fact that “our ways of thinking about ecology are also constantly changing, or ecology is constantly changing while we keep trying to understand it.”36

In Diorama en expansión, exhibited in 2001 in Santiago (Chile), Arteaga brought an understanding of these dynamic interactions into a more explicit dialogue with Chile’s ecological crisis.37 The diorama he created again invited viewers to move around the space; the addition of sound art and hanging mobile constructions that circled slowly also had an immersive effect. Prominent place was given to species that play an important role in regulating ecosystems, such as fungi and bats. Arteaga also included in the exhibition some pieces he had originally developed for the 2018 Slade School of Fine Art Degree Show (London), entitled Monocultivos (pinus radiata) and Monocultivos (eucalyptus globulus).38 These consisted of large sheets of paper from which the forms of leaves, seeds, and branches had been burned, leaving silhouettes. As Arteaga explains, they were intended to draw attention to the excessive monocultures of Monterey pines and fast-growing eucalyptus trees in Chile, and the relationship between these plantations and the recent increase in droughts and forest fires.39 In Arteaga’s hands, dioramas are rather more than “mausoleums of a vanishing heritage”;40 instead, they represent dynamic encounters that encourage an awareness of the continual transformations that characterize both the natural world and our constructions of it.

Pablo La Padula: Museo liberado and the Violence of the Modern State

A mischievous intent animates Pablo La Padula’s Museo liberado (Liberated Museum, 2021), which stages the “release” of taxidermy animals from their usual homes in the glass display cases and basement storage rooms of the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (MNHN) in Montevideo, Uruguay. La Padula’s concept involved a collaboration between the museum and the neighbouring Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo (EAC), with which it shares a building. The museum’s taxidermied animals were brought into the art gallery and positioned as if they were making a break for freedom: crawling, prowling, strutting, waddling, and swooping their way to the exit (see Fig. 6.8). The two interconnected rooms of the EAC’s Sala Miguelete have their architectural counterparts in two other rooms, situated across the corridor, which house dioramas curated by the MNHN. The mirroring of these two spaces allowed La Padula to reflect on the different ways in which art and science have sought to capture, interpret, and display the natural world. The theme of captivity acquires broader resonances given the history of the larger building that now accommodates both the MNHN and the EAC. This operated between 1888 and 1986 as Uruguay’s first and most important prison, and the first in Latin America to have been built according to the panopticon design; it also functioned as a detention centre for political prisoners during the military regime of 1973–1985.

Fig. 6.8 Installation view of Pablo La Padula, Sala de Escape from Museo liberado (2021). Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Montevideo, Uruguay (photograph by Elena Téliz and Maite Silva, Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo).

Entrance to the Museo liberado is through the “Sala de Captura” (Capture Hall). Working entirely with material borrowed from the MNHN, La Padula laid out in this space some of the techniques and devices used to capture and order the natural world, including illustrations, microscopes, and encyclopaedias (see Fig. 6.9). Many of these items, such as an old wooden card index cabinet and sepia portraits of the museum’s founder and a major patron, return us to the museum’s nineteenth-century past (it opened in 1838). Most of the yellowing notebooks, the insectariums and the specimens preserved in jars of formaldehyde relate to two expeditions organized by the Museum: to the Mato Grosso, Brazil (1955) and the Orinoco, Venezuela (1957) (see Fig. 6.10). Some of the room’s objects, such as the fossils and butterfly cabinets, were intended for public display, while many of them have remained in museum basements, store cupboards, and laboratories. Their presence draws attention to the customary division of the modern museum’s spaces into ones for professional use and others for public use. Antiquated museum pieces themselves, these artefacts also point to the gradual shift, since the nineteenth century, of the locus of scientific activity from the museum to the controlled conditions of laboratories based elsewhere.

Fig. 6.9 Installation view of Pablo La Padula, Sala de Captura from Museo liberado (2021). Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Montevideo, Uruguay (photograph by Elena Téliz and Maite Silva, Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo).

Fig. 6.10 Installation view of Pablo La Padula, Sala de Captura from Museo liberado (2021). Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Montevideo, Uruguay (photograph by Elena Téliz and Maite Silva, Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo).

The direct comparisons suggested by the architectural relationship between the Museo liberado and the MNHN galleries sharpen the institutional and decolonial critiques developed in La Padula’s installation. On the other side of the corridor, in the MNHN’s recently modernized dioramas, the fossils and taxidermied animals that have been recruited to showcase the major eras of the Earth’s pre-history are organized along a thick red timeline. As in many scientific collections and displays, these objects are categorized and made legible within a linear narrative of evolution that rests on (Western) ideas of time and progress. Their confinement in glass cases clearly demarcates a divide between viewing subject and object to be viewed. Across the way, in the Museo liberado’s “Sala de Captura,” there is no fixed path through the exhibition, no narrative, no timeline, and its objects are fully available to be touched, picked up and rearranged. No labels define them within expert taxonomies: La Padula firmly resisted the museum staff’s desire to identify the date and provenance of each item, wishing visitors to move freely around the room and to construct their own narratives in relation to the material they viewed.

This technique encourages a reflection on how the “meaning” of a specimen changes or is lost altogether when it is removed from its context within a thematic or narrative display. Museo liberado demonstrates that knowledge is not simply constructed through the observation of objects themselves; it emerges from a complex interplay between objects and their emplacement in particular spaces, as well as their insertion in regimes of visuality and their relationship with the texts that accompany them, in the form of labels, notes, and guides. As objects are moved from one space to another, as their labels are changed or removed, and as the circumscribed gaze of spectatorship becomes an opportunity for different kinds of interaction, the values that had seemed to be inherent in those objects become subject to change.

In presenting his proposal to redeploy objects from the MNHN, La Padula needed to reassure staff there that his intention was not to undermine the authority of science but to expand its perspectives. Reflecting on his own use of materials from natural history museums, Mark Dion finds that artists engaged in institutional critique fall into two camps: those who see the museum as “an irredeemable reservoir of class ideology” and those who adopt a critical stance toward the museum “because they want to make it a more interesting and effective cultural institution.”41 La Padula’s approach certainly falls into the latter category. Museo liberado encourages us to reflect on the historical relationship between the rise of the natural history museum and the consolidation of state power in Latin America, expressed in its capacity to extract, expropriate, and preserve life. The significant boom in scientific activity that took place in the region in the last part of the nineteenth century and the first three decades of the twentieth was driven by the faith that the political elites placed in science as a means of making the economy more productive, mapping out territories that had not yet been fully explored, Europeanizing local cultures, and educating, disciplining, and controlling large populations.42 La Padula’s critique is directed toward the powerful legacy of positivism that is still evident in the organization of many of Latin America’s museums; he considers that among the general public, “la ciencia sigue siendo un espejo de la naturaleza y maneja una verdad única e irrevocable” (science remains a mirror of nature and administers a unique and irrevocable truth).43

Positivism played a significant role, not only in the founding and shaping of museums in Latin America, but in the application of a rather reductive scientific logic to an understanding of the evolution of human society. For Auguste Comte, the French philosopher who first developed the doctrine of Positivism, humanity—rather than God or nature—was the horizon of positivist thought. The “diverse branches” of knowledge Comte describes are unified in a single science of which “our existence is at once the source and the end.”44 The two permanent dioramas presented by the MNHN, fittingly named “Nuestro Pasado” (Our Past) and “Nuestro Presente” (Our Present), communicate a clear vision of the role of science in society that accords with this positivist and humanist agenda. Printed on the glass through which the visitor views taxidermied animals and fossilized remains is the reminder that “conocer el pasado es un ejercicio fundamental para entender el presente y proyectar el futuro” (knowing the past is essential in understanding the present and projecting the future). Pointing to the importance of natural history in explaining the processes that underpin climate change, the Museum glosses over its own role, past and present, in the crises it now narrates: its collusion in colonial and capitalist expansion and the extinctions aided by its own collecting practices.

An allusion to this role is made in Museo liberado in the screening of Una aldea Makiritare (A Makiritare Village, 1958), a short documentary directed by Roberto Gardiol Armand’Ugon during the Orinoco Expedition, on a television in the corner.45 The film suggests a broader relationship between the zeal to collect and categorize natural specimens and the appropriative, exoticizing, imperialist gaze of mid-twentieth-century anthropology. In it, the camera lingers as it describes the pronounced muscular development of the thoracic cage in male members of the Makiritare tribe, objectifying them even as the narrator admires their primitive skills in canoe-building. The inclusion of the film in La Padula’s exhibition makes explicit the connection between collecting and conquering, reminding us that even in the new Latin American republics, the state’s assumption of the role of collection-building “contiene un acto de violencia estatal: la conquista de un territorio, la dominación de un grupo, la muerte de los individuos vivos, la internalización por coerción o consenso de determinadas reglas sociales” (contains an act of state violence: the conquest of a territory, the domination of a group, the death of living individuals, the internalization—by coercion or consensus—of certain social rules).46

The objects placed in the “Sala de Captura” thus emphasize the function of the Museum, not primarily as a space of displays to serve the aim of public education, but as the leader and sponsor of scientific expeditions and the curator of collections intended for research. These roles have been shaped by political, economic, and cultural objectives as much as scientific ones. Museo liberado insists on an essential point of equivalence between the natural history dioramas and the art gallery installations. It is not that one is more “natural” and the other more “cultural”: in their approach to the natural world, both are profoundly shaped by (Western) cultural paradigms, from colonialism to conservationism.47

In the “Sala de Escape” (Escape Hall), the taxidermied animals positioned as if they were heading for the exit include many species that are native to Uruguay, such as the rhea, the coati, the armadillo, and the carpincho. Their presence reminds us of the particular importance of natural history in the decades following Independence for many Latin American states. Given the absence of significant linguistic or cultural differences between criollo elites and their former colonizing power, natural history collections made a crucial contribution to the search for a national identity, while allowing the state to extend its power over its territory and to measure the economic value of its natural resources.48 While the taxidermied animals in the “Nuestro Presente” exhibition across the corridor are neatly segregated in dioramas to represent Uruguay’s major ecosystems (including native forests, wetlands, farmland, and coastal regions), in the “Sala de Escape” they are torn from their ecological niches and made, improbably, to share the same space. This uprooting is only a pale reflection, of course, of the much more violent extraction that brought them to the museum in the first place. These animals’ collective bid for freedom points to the cost—in animal, plant, and human life—of the consolidation of nations as political, economic, and cultural systems, both in Latin America and elsewhere.

The “Sala de Escape” was the subject of intense negotiations with the MNHN. The Museum had wanted all the taxidermy specimens to be carefully protected, placed on platforms and in glass cases, despite the fact that the animals loaned to La Padula were some of the museum’s most neglected and deteriorated objects, many of which had been piled up between cupboards in the basement.49 The opening of the exhibition was in fact delayed by several weeks while MNHN staff cleaned and restored some of the specimens to ready them for public viewing. In the end, after much discussion, no platforms were used but some of the animals were shown in glass cases. La Padula was content with the outcome, as it demonstrated the challenges of negotiating with an institution with its own rationales of preservation and exhibition, often very different from those of a contemporary art gallery. It also gestured toward the deliberately partial, compromised “freedom” that the animals had been granted. The taxidermied animals are arguably “freed” from serving as types or examples in of particular ecosystems or stages of evolution. But their expropriation for the purposes of an art installation does not, of course, liberate them: it simply subjects them to another kind of capture. As La Padula suggests, once these animals have become enmeshed in human culture, there can be no return for them to the wild.50 Their stiffened heads, many turned unnaturally away from their direction of travel, remind us that they were originally designed for another context and that their co-option into this exodus simply inscribes them into another fiction of human making.

In a context in which—as La Padula believes—“el común de la población tiende a pensar que el científico tiene una voz más veraz que la del campo de las artes visuales, la cultura” (the general population tends to think that the scientist’s voice is more truthful than those of the fields of visual arts or culture),51 Museo liberado relocates and recombines exhibits to highlight the illusory coherence of the natural history museum’s narratives and to construct a role for art in presenting a different kind of truth: one that reflects on the practices and the values that have produced the knowledge accumulated in the museum’s dioramas. Many natural history museums have been resignifying their exhibits to create new narratives on the current crises of biodiversity loss and climate change. Yet these themes may be no less deterministic or human-centred than older, positivist narratives of progress, order, and civilization.

Museo liberado reminds us of the many and varied ways in which animals have been, and continue to be, conscripted for human purposes, whether in science or in art. It reflects on the systems of capture through which the (animal and human) other is disciplined, but also those through which viewers become subject themselves to the disciplining power of the state. It is in this sense that Jens Andermann observes that the modern museum “looks forward to the camp,”52 a chilling alliance that is underscored in this case by the installation of Museo liberado in Montevideo’s ex-prison. As we contemplate the modern museum’s “collection of corpses,” Andermann suggests, “the silent threat implied in the museum’s visual pedagogy” is that we, too, might become exposed to the violence contained in the gaze.53 La Padula demonstrates that nature, once captured, cannot be freed from the self-regarding fantasies of human culture; likewise, in Museo liberado both humans and animals are ultimately caught up in the thanatopolitics of the liberal Latin American state.

Walmor Corrêa’s Animal Recompositions and Repatriations

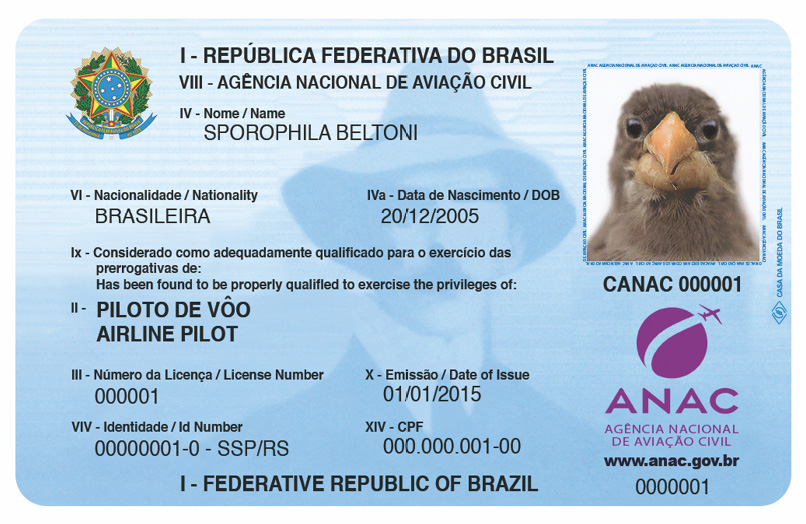

Among the various maps, drawings, photographs and paintings included in Walmor Corrêa’s Sporophila Beltoni exhibition (2018) are two forged documents proving Brazilian citizenship (an identity card and a passport) and a fake pilot’s licence issued by the national civil aviation authority (see Fig. 6.11).54 The creation of these forgeries would have been a crime, but for the fact that the putative owner of the documents is a Brazilian finch, a small, stubby-beaked bird staring squarely and solemnly at us in the identifying photograph.

Fig. 6.11 Walmor Corrêa, forged pilot’s licence, Sporophila Beltoni (2018). Instituto Ling, Porto Alegre, Brazil (photograph by artist).

The bird has remained still enough to photograph because it is a taxidermy specimen. Abandoned and incorrectly labelled, it was discovered by Corrêa at the back of a drawer in the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The journey that took him there had involved extensive research and correspondence with museum curators and Brazilian specialists, in the hope of finding a Sporophila beltoni, a bird formally identified only in 2013 by ornithologists from the Rio Grande do Sul. The specimen had been misclassified when it arrived in the museum in 1820, and had languished there since then, undiscovered. Corrêa’s research reconstructs the history of the bird’s death and its subsequent travels, hypothesizing—on the basis of the date on its identification tag and the signature tilt given to its head—that it was captured by the Austrian naturalist and taxidermist Johann Natterer. At a meeting with the Brazilian Ambassador to the US, Corrêa formally petitioned for the recognition of the bird’s Brazilian citizenship in the form of a passport. The many documents Corrêa commissions for the specimen, which include birth and death certificates, are a playful way of creating an identity for a bird that died for the sake of scientific knowledge but lay forgotten and wrongly catalogued for nearly two centuries. The project as a whole draws attention to the ways in which birds and other animals have been—and continue to be—killed and expatriated in the name of science, and how those specimens (and the knowledge they make possible) became concentrated in wealthy museums in Europe and North America.

Corrêa traces a cultural afterlife for the taxidermy bird, resituating it within the geopolitics of scientific exploration in the past and creating resonances with the barriers to human migration and citizenship that divide our “global” world in the present. Aloi suggests that an emphasis on the afterlives of taxidermied objects may return to the animal “a kind of individuality” through “the mapping of specific events that shaped its material existence.”55 Most importantly, it demonstrates that “the biological death of the animal does not equate to the end of animal agency.”56 Even in death, he argues, material animal bodies are “capable of affecting, and reflexively shaping, human/animal relations.”57 Corrêa’s Sporophila beltoni does not only tell the expected story of science’s collusion with power in the forms of colonialism and capitalism, but also points to the omissions, the mistakes, and the missing links that interrupt the construction and global circulation of knowledge. These chinks and ruptures in our systematization of nature allow us to imagine—if only playfully and temporarily—the overturning of the authority that justified imperial acts of dispossession on the part of museums in Europe and North America.

Other works by Corrêa create fictional afterlives for animals by intervening directly in taxidermy objects themselves. These are always bought from specialists or received via donations and resignified for artistic purposes. In Para onde vão os pássaros quando morrem? (Where Do Birds Go When They Die?, 2012), he constructs miniature dioramas of the kind commonly to be found as ornaments in nineteenth-century homes, with small taxidermy animals arranged under a glass dome. Typically, as Pat Morris points out, such displays were more decorative than scientifically accurate: species of birds from different continents were mixed together, adopting poses that were often unnatural but designed to show off their colourful plumage in the most favourable way.58 Brightly coloured hummingbirds were particularly popular in such displays, caught by professional bird trappers in Central and South America and sent to markets in London and Paris.59 Corrêa’s own dioramas often feature hummingbirds, modelled with precision to create beautiful, delicate specimens. They are perched elegantly on twisted twigs against a background of vivid green foliage, combining ferns, firs, grasses, and cacti in a deliberate disregard for ecological verisimilitude. The hummingbirds themselves are also a work of fiction. Their beaks are curled gracefully into a spiral, rendering them completely useless as a means for feeding. Other taxidermy animals recreated by Corrêa unexpectedly combine feathered bodies with heads of small rodents, joined so neatly at the neck that they seem entirely natural.

In part, Corrêa’s fictional creatures point to the artifice at the heart of taxidermy’s naturalism. The shock of the real in the taxidermic object—this is an animal that has lived and stands before us—is always created through a series of fabrications, which produce the effect of a living, breathing animal. Through animal re-creation, Mark Simpson suggests, taxidermy claims itself to be “an artless art—an art for nature and against artifice, a mode of mediation beyond mediation itself.”60 However, the “truth-value” of taxidermy specimens in a museum display, their usefulness as a pedagogic tool, depends not only on the painstaking creation of casts and models on the basis of careful measurements but also on multiple “small frauds.”61 “Composites” were often constructed, for example, to supply a single, unblemished specimen, as these were rarely to be found in nature (and much less, as Michael Rossi points out, when the subjects were whales killed by exploding harpoons).62 Corrêa’s work alludes to the fabrications and idealizations that guarantee the taxidermic reproduction of lifelikeness. Unlike the deliberately incongruous taxidermy hybrids produced by the German sculptor Thomas Grünfeld for his Misfits series (1989–), Corrêa’s exquisite recreations trick the eye, seeming so natural that we only notice their falsities on closer inspection.

These highly decorative ensembles of reinvented animals also seem to comment on the anatomical and ecological absurdities that resulted from taxidermy’s slippage in the nineteenth century from an object of scientific study to one of fashion and lucrative marketability. Yet Corrêa’s hybrids are also inspired by the particular fabrications and errors that are to be found in early Jesuit accounts of the wonders of Brazilian nature. Padre José de Anchieta describes an insect that may metamorphose into a rat or into a butterfly, and tiny hummingbirds that “alimentam-se só de orvalho” (feed only on dew).63 Anchieta also writes that one species of hummingbird is believed by all to derive from the butterfly, echoing a belief that was widespread at the time.64 As if to provide a poetic illustration of this heterogenesis, one of Corrêa’s dioramas depicts a tower of tropical butterflies, with two hummingbirds placed at the apex (see Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12 Walmor Corrêa, diorama from Para onde vão os pássaros quando morrem? (2012). Plastic, taxidermy, paint, resin, paper and glass, 60 x 20 cm (photograph by Letícia Remião).

In many of his domes, Corrêa adds a tiny trace of human consumption in the form of a cigarette butt, a piece of chewed gum, or the crumpled top of a Coca-Cola bottle, shattering the myth of an untouched nature that was so often depicted in natural history museum dioramas. The careless intrusion of trash in an otherwise perfected nature also points to the increasing incursion of human waste into natural environments. The themes of waste and disposability are developed more fully in the installation Voçê que faz versos (You Who Write Poetry, 2010), for which Corrêa assembled a scene of wooden crates and trash cans and introduced a number of his rodent-headed birds as scavengers, feeding on discarded cookies and other detritus (see Fig. 6.13).65 As in Arteaga’s Diorama en expansión, animals are not simply there to be looked at, confined within a remote wilderness and brought to us via the devices of museum displays. Instead, they are thoroughly interpolated in our own urban habitat in ways that confront and discomfort us.

Fig. 6.13 Walmor Corrêa, scene from Você que faz versos (2010). Instituto Goethe de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil (photograph by Letícia Remião).

The freezing in time and space of this scene seems to give it a noble quality that is belied by its prosaic subject matter. Aloi argues that the stasis of diorama displays bestows a quality of transcendence through an association with classical sculpture and painting.66 In classical art, “sculptural stillness constitutes the representational element signifying a moral dimension imbued with a meditative sense, suggesting the solemnity of an event and the ethical elevation of a subject matter.”67 In its own sculptural stasis, taxidermy also takes on the values of classical art and particularly its ennobling of nature, lending itself to the “ventriloquization of decorum” as a value expressed both in moral virtue and aesthetic elegance.68 Mark Dion’s taxidermy diorama Landfill (1999–2000) refuses to comply with this convention; as Aloi affirms, the scavengers picking over mounds of human-generated waste are a far cry from the heroic animals of classical art and cannot easily be inscribed with the attributes and values to which humans aspire.69 In a similar way, Corrêa’s Voçê que faz versos provokes a sense of deep incongruity in appearing to ennoble animals that we would normally overlook or exterminate without compunction.

The animal virtues that Voçê que faz versos seems to uphold in its aesthetic debt to classical sculpture are not ones of beauty or dignity, but those of adaptability and the capacity to recycle and repurpose. These are skills that are often found in synanthropic species, which have adapted their behaviour to urban living and benefit from the warmth, increased food supplies, and nesting opportunities they derive from a proximity to humans. In a similar way to Mark Dion in his Concrete Jungle (Mammalia) (1993), in which taxidermied rats, cats, and raccoons feed off human refuse, Corrêa points to the extent to which nature is reworked in culture. But in Corrêa’s Voçê que faz versos those skills of adaptation and recycling are also expressed in the artist’s own refashioning of taxidermy objects. To recompose the disposable, to make new creations from waste, are certainly skills that twenty-first-century humans are learning to respect and admire. If Concrete Jungle (Mammalia) reveals how human culture has thoroughly shaped the habitats and practices of other animals, Voçê que faz versos draws equal attention to what we may learn ourselves from the animals that cohabit with us: their adaptability, their resilience, their ingenious use of available sources of energy. Corrêa’s taxidermy hybrids are a celebration of the inventiveness, the diversity, and the resilience of life, which persists despite our continual depredations of it.

Conclusion

In 2015, the Natural History Museum, a project created by an activist artist collective based in the US, restaged a diorama that had formed part of an exhibition on climate change a few years earlier at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York.70 The original diorama had featured a polar bear clambering over a pile of garbage. In its recreation, the Natural History Museum inserted a Koch Industries oil pipeline into the pile as a protest against the entanglement of the interests of fossil fuel industries with those of AMNH, where David H. Koch was a board member and exhibition sponsor. Another activist art collective based in Argentina, the Grupo Etcétera, created its own diorama in 2021 as a protest against neo-extractivist practices in the region (see Fig. 6.14).71 Instead of taxidermied animals, it featured round, pink piggybanks set against a black-and-white backdrop of an entirely industrialized countryside. A video showing a cartoon version of The Three Little Pigs warns viewers to be wary of how one might build for the future. Entitled Diorama, Museo del Neo Extractivismo (Diorama, Museum of Neo-Extractivism), the installation also questioned how the museum as an institution might be implicated in constructing and disseminating fables about nature and our interventions in it, situating it squarely within a capitalist system that commodifies and exploits the natural world.

Fig. 6.14 Installation view of Grupo Etcétera, Diorama, Museo del Neo Extractivismo (2021). Centro Cultural Kirchner, Buenos Aires, Argentina (photograph by the author).

In their own remediations of, or interventions into, natural history museums and taxidermy animals, Arteaga, Bustos, Corrêa, La Padula, and Malva may be understood as engaging in forms of institutional critique. This critique is often of a different kind, however, to that pursued by the Natural History Museum, the MTL Collective, Grupo Etcétera, and other activist-artists who have sought to decolonize the (Western) museum, denouncing its role in operations of colonial exploitation, extraction, and erasure, as well as its fantasies of possession, its continued Eurocentrism, and its collusion with carbon-intensive industries or corporations with low ethical standards. The works explored in this chapter are more philosophical than overtly political in their critique. They interrogate the epistemological divisions between human and animal, nature and culture, subject and object, on which Western modernity has been founded, and which have driven its universalizing, imperialist, anthropocentric expansion across the world. This expansion was not checked by the transition to independence in Latin America: the new republics often engaged in even more brutal acts of subjugation in order to extend their governance over heterogeneous populations and profit from the natural resources available within the borders of their nations. The deconstructions, reconstructions, displacements, and remediations carried out by Arteaga, Bustos, Corrêa, La Padula, and Malva reconnect natural history with social history, showing how the modern museum in Latin America is implicated in a violence that includes both human and nonhuman animals. If there can be no return to nature for animals caught up in human culture, these artists do trace ways in which the use of taxidermy in art may return agency to animals, and even express values that are less anthropocentric.

1 See, for example, Maynard, Manual of Taxidermy; Browne, Practical Taxidermy.

2 Hornaday and Holland, Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting, vii.

3 Hornaday and Holland, vii.

4 Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, 104.

5 Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy,” 57.

6 Hughes, “Performing Taxidermy or the De- and Reconstruction of Animal Faces in Service of Animal Futures,” 172.

7 Baker, The Postmodern Animal, 54–76.

8 Marbury, Taxidermy Art, 12–15.

9 Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy.

10 Aloi, 16.

11 Boetzkes, “Art,” 65.

12 Some pieces were shown at the Galeria Mezanino, São Paulo, Brazil, in 2009. More complete exhibitions of the series were held in 2014 with the title Gabinete de curiosidades (Cabinet of Curiosities) at the Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London and the Shoot Gallery in Oslo.

13 Correspondence with the author, 19 January 2022.

14 Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, 88; Sontag, On Photography, 154.

15 Conversation with the author, 2 February 2022.

16 Boetzkes, “Art,” 68.

18 Conversation with the author, 2 February 2022.

19 Lippit, Electric Animal, 1 (original emphasis).

20 The video may be viewed at http://www.adrianabustos.com.ar/portfolio/recursos-

2014/

21 Correspondence with the author, 21 October 2022.

22 Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy,” 25.

23 Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy, 105.

24 Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy,” 52.

25 Haraway, 57.

26 Jara, “Situación crítica del yaguareté.” The yaguareté has in recent years been the target of several successful conservation initiatives in Argentina, including the Proyecto Yaguareté and the Fundación Rewilding Argentina.

27 The exhibition was a collaboration with AirSpace Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, where Arteaga completed a residency in 2017. Further images may be viewed at http://www.rodrigoarteaga.com/This-path-one-time-long-time-ago

28 Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy,” 24.

29 Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, 104.

31 Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, 20.

32 Arteaga, “A Natural Selection—Residency by Rodrigo Arteaga—#4.”

33 Images from the exhibition may be viewed at http://rodrigoarteaga.com/Natural-selection-AirSpace

34 Rader and Cain, Life on Display, 54.

35 Arteaga, “A Natural Selection—Residency by Rodrigo Arteaga—#4.”

37 Diorama en expansión was exhibited at the Museo de Artes Visuales (MAVI) in Santiago, between 25 September and 28 November 2021. Images of the exhibition may be viewed at https://www.rodrigoarteaga.com/ES/Diorama-en-expansion

38 The series were created in collaboration with the illustrator Marcela Mella.

39 Correspondence with the author, 21 October 2022.

40 Wonders, “Habitat Dioramas as Ecological Theatre,” 285.

41 Corrin, Miwon, and Bryson, “Miwon Kwon in Conversation with Mark Dion,” 16.

42 Carreras and Carrillo Zeiter, “Las ciencias en la formación de las naciones americanas: Una introducción,” 16.

43 Conversation with the author, 22 April 2021.

44 Comte, A Discourse on the Positive Spirit, 39.

45 The film may be viewed at https://vimeo.com/160761571

46 Podgorny and Lopes, El desierto en una vitrina, 20.

47 The insertion in the “Sala de Captura” of works by two invited Uruguayan artists, Magela Ferrero (El libro de las migas) and Brian Mackern (Frecuencias de resonancia), also pointed to the considerable convergence between scientists’ modes of capturing nature and those of artists.

48 Carreras and Carrillo Zeiter, “Las ciencias en la formación de las naciones americanas: Una introducción,” 13.

49 Conversation with the author, 6 October 2021.

51 Conversation with the author, 22 April 2021.

52 Andermann, The Optic of the State, 17.

53 Andermann, 57.

54 Walmor Corrêa e Sporophila Beltoni was held in the Instituto Ling in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 2018.

55 Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy, 54.

56 Aloi, 54.

57 Aloi, 56.

58 Morris, A History of Taxidermy, 56.

59 Morris, 56–57.

60 Simpson, “Powers of Liveness,” 60.

61 Rossi, “Fabricating Authenticity,” 353.

62 Rossi, 353.

63 Anchieta, Carta de São Vicente 1560, 27, 30, 46n58. This would of course be a biological impossibility, and in fact hummingbirds feed mainly on small insects and spiders.

64 Anchieta, 30, 46n58.

65 Voçê que faz versos was shown in 2010 at the Instituto Goethe in Porto Alegre and the Galeria Laura Marsiaj in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The exhibition’s title is taken from “José” (1942), a well-known poem by the Brazilian writer Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902–1987) that is often read as an expression of uncertainty and anguish, composed at a time of war on the international stage and political repression at home.

66 Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy, 114.

67 Aloi, 122.

68 Aloi, 127.

69 Aloi, 108.

70 The diorama, entitled Our Climate, Whose Politics?, was shown at the American Alliance of Museums Annual Convention in Atlanta in 2015.

71 Diorama, Museo del Neo Extractivismo was shown as part of an exhibition entitled Simbiología: Prácticas artísticas en un planeta en emergencia at the Centro Cultural Kirchner, Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2021–2022.