Italy:

Mariia Olsuf’eva: The Italian Voice of Soviet Dissent or, the Translator as a Transnational Socio-Cultural Actor

©2024 Ilaria Sicari, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0340.11

The Translator of Samizdat as Socio-cultural Actor

In the wake of the “cultural turn”,1 in recent decades the field of Translation Studies has witnessed the emergence of a sociological approach which considers any translation as a “socially regulated activity”,2 namely, a cultural product “necessarily embedded within social context”.3 In this perspective, all the human agents involved in the different phases of a translation—i.e. selection, production, and dissemination—started to “be accounted for not only as professionals but as socialized individuals”.4 When considering the translator as a socialised individual, one should take into account not only that “[t]he habitus of a translator is the elaborate result of a personalized social and cultural history”,5 but also that “[t]he actors’ plural and dynamic (intercultural) habitus therefore forms a key concept for understanding the modalities of intercultural relationships”.6 The translation itself is then conditioned to a certain extent by “the agents involved in the translation process, who continuously internalize the aforementioned structures [such as power, dominance, national interests, religion or economics—IS] and act in correspondence with their culturally connotated value systems and ideologies”.7 Consequently, it is possible to contextualise the social dimension of the translation and its relative reception only if the agency of the translators is also taken into account. In this analytical framework, the translator should be perceived not only as the linguistic and cultural mediator of the source text and as co-creator of the target text, but also as a socialised individual who acts and, consequently, makes choices according to his/her personal experiences; his/her political, religious, and ideological beliefs, and, not least, his/her relationships with other socio-cultural actors involved in the selection, production and diffusion of translations.8

In the specific case of translating samizdat, the modalities and dynamics of intercultural relationships implemented by the translator working across the Iron Curtain had a transnational dimension. The unofficial flow of cultural objects across and beyond the Iron Curtain—a geopolitical and ideological boundary that was permeable9 to the point of being defined by György Péteri as a transparent “Nylon Curtain”10—was primarily composed of two kinds of texts, both of which constitute “a specific form of socio-cultural practice”:11 samizdat and tamizdat. A transnational cultural cross-border transfer such as the smuggling of uncensored Soviet texts in both directions—samizdat from Eastern to Western Europe and tamizdat, the other way around—was possible only thanks to the cooperation and collaboration of different cultural actors (editors, translators, literary agents, critics, journalists) and social agents (such as human rights activists, dissidents, diplomats, political, and religious figures) involved in the production, diffusion, and reception of those texts on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Consequently, samizdat and tamizdat were the result of a complex process of negotiation and bargaining by a varied group of individuals forming a “transnational community”.12 Thus, this “transnational socialization of texts”13 was made possible thanks to the personal contribution—at different levels and with different functions—of social and cultural agents who acted not only as professionals, but also as socialised individuals. The translation of samizdat as a social practice and the role of the translator as a transnational socio-cultural actor responsible for the socialisation of these texts between the two sides of the Iron Curtain will be illustrated by the case of one of Italy’s major translators of samizdat: Mariia Olsuf’eva. As I show below, several factors make her case emblematic for this volume.

By examining the archive of Mariia Olsuf’eva’s personal papers14 as well as archival documents of the publishing houses Mondadori and Il Saggiatore,15 I aim to reconstruct her activity in terms of what Jeremy Munday calls the “micro-history of translators”, meaning the reconstruction of the social and cultural history of translators. As “personal papers […] give an unrivalled insight into the working conditions and state of mind […] of the originator of the papers and the social activity in which he or she is engaged”,16 through the analysis of these documents, I will delineate a complex picture of the exchanges and transnational relations that Olsuf’eva conducted with the various socio-cultural actors involved in the production, circulation, and dissemination in Italy of uncensored Soviet literature (nepodtsenzurnaia literatura). In particular, I shall address her role in the reception of samizdat and tamizdat in Italy; explore her position within the transnational community as an enabler of their circulation between Eastern and Western Europe; and, last but not least, I shall examine the functions of her socio-cultural activity and activism.

Mariia Olsuf’eva: A Transnational Socio-cultural Actor

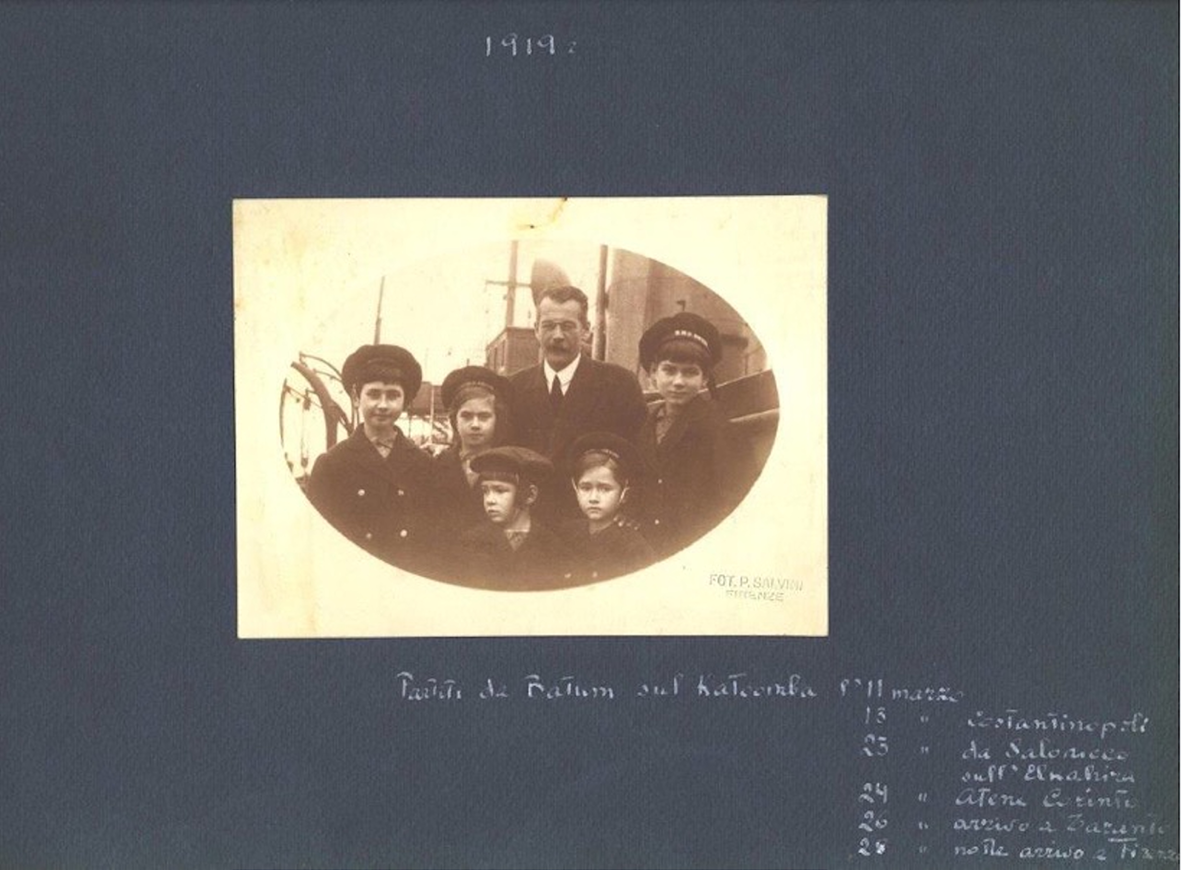

Mariia Olsuf’eva’s transnational position is evident even in her identity card: she was a Russian born in Italy, with dual Italian and Swiss citizenship. Russian was her mother tongue, but she also spoke Italian, into which she translated and interpreted. Daughter of the tsarist colonel Vasilii Alekseevich Olsuf’ev and descended from an ancient Russian noble family, Mariia Olsuf’eva was born in Florence in 1907, where she spent the first four months of her life before moving to Russia, her home until the age of eleven.17 Every year she holidayed at her parents’ Florentine villa, thus maintaining a deep bond with the Tuscan city.18 The outbreak of the October Revolution found her in the Caucasus with her family: by travelling through Batumi and Constantinople, after a daring journey on an English military ship, they managed to take refuge in Italy in 1919, settling permanently in Florence.19 In 1926, Mariia Olsuf’eva married a Swiss-Italian agronomist, Marco Michahelles, and thus acquired Swiss citizenship. However, Florence remained her adopted city; she died there in 1988.

Fig. 1 A page from the family album that portrays Mariia Olsuf’eva (first on left) with her father, Vasilii Alekseevich Olsuf’ev, sisters (Dar’ia, Aleksandra and Ol’ga), and brother, Aleksei, in Batumi, en route to Italy, 1919. The dates and stages of the journey are marked at the bottom right. Courtesy of Daria Bertoni.

Fig. 2 Mariia Olsuf’eva (first on the right) with her mother, Ol’ga Pavlovna Shuvalova, sisters and brother in Italy, 1921. Courtesy of Daria Bertoni.

Mariia Olsuf’eva often said that Russia was the country where she felt she had her roots.20 Throughout her life, she maintained this bond with her motherland by translating numerous Russian writers into Italian, weaving a series of contacts with the Russian intelligentsia in exile, forging lasting and deep friendships with leading Soviet dissidents and, importantly, acting as starosta of the Orthodox church of Florence.21 Her support for Florence’s large Russian community soon led her to welcome the exiles of the so-called third wave of immigration (1960–80) arriving from the Soviet Union.22 Olsuf’eva did not only offer support to exiled Russians, but also actively worked in favour of Soviet dissidents and activists within the USSR. She made their voices heard beyond the Iron Curtain not only by translating their works into Italian, but by sharing their appeals in national and foreign newspapers and by promoting various initiatives in their favour. A member of Amnesty International, she was among the founders of its Florentine section, launching national and international campaigns in support of different dissidents—including Andrei Sakharov, Elena Bonnėr, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn—with whom Olsuf’eva was also linked by a deep friendship. Due to her activism, her work as a translator of many samizdat and tamizdat texts, and her material contribution to the circulation of Soviet clandestine manuscripts, in 1973 she was declared persona non grata by Soviet authorities.23 She died in Italy, unable to return to Russia, thus paying dearly for her life choices.

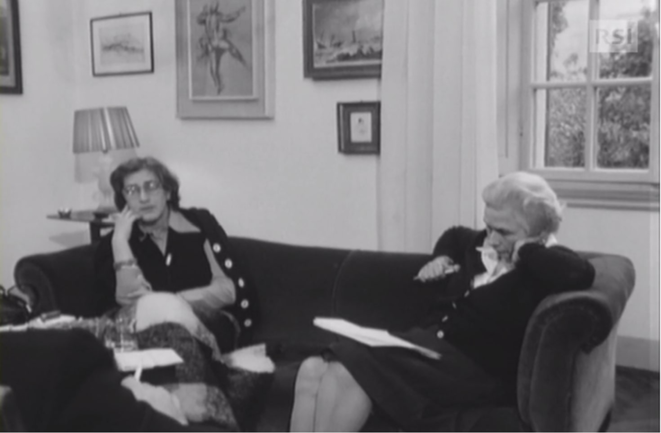

In an interview broadcast in 1975 on Swiss-Italian radio and television (RSI), she commented:

Of course, I regret that I will not be able to go back [to Russia]. On the other hand, I prefer to have translated Solzhenitsyn, this is also a choice. If I were faced with this choice, to translate Solzhenitsyn or to be able to get my visa back to Russia, I would choose to translate Solzhenitsyn. Being Solzhenitsyn’s voice in Italy is a tremendous honour for me.24

To the journalist Enrico Romero, who asked her if translating Solzhenitsyn was “a kind of posthumous revenge”25 for the exile into which she had been forced, Olsuf’eva replied:

No. It is not a revenge. It is simply that I consider him such a great writer and [The Gulag Archipelago] is such an important work for all of us, and it is an honour for me to translate it. I do not know how to express it otherwise. For me, it is the highest point a translator can reach.26

Fig. 3 A frame from Romero’s interview with Maria Olsuf’eva, released in 1975. Courtesy of RSI.

In a 1974 letter to Solzhenitsyn (responding to his concern that her translation of the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago—Arkhipelag Gulag, 1973–75—was made too hastily, thus compromising textual fidelity), Olsuf’eva expressed even more frankly and resolutely her reasons for translating his work:

I have no doubt that here and there another translator would change a comma, an adjective, etc. but I have fulfilled what I considered and still consider much more important: to give Italy, especially in such a politically difficult moment for this country, the possibility of knowing as soon as possible the whole truth, that truth which A. D. Sakharov, in transmitting to me by telephone his Appeal from Moscow [Moskovskoe obrashchenie, 1974], said was needed by all men on earth.27

These few lines clearly show that Olsuf’eva saw her task more as a mission than as a purely literary activity. That mission was not only cultural but markedly social and political, a side which she considered “much more important” than all the rest: her goal was to spread the voice of Soviet dissent in Italy (and throughout the world), thereby contributing to the struggle for civil rights that was being fought in the USSR and, through the translations of prohibited books, to attract the interest of international public opinion on these issues.

Cultural Activity

Olsuf’eva started translating from Russian into Italian in the 1950s, initially while teaching at the Higher School for Interpreters and Translators in Florence and later collaborating with some of the main Italian publishing houses for about forty years.28 Her first translation, published in 1957, was Vladimir Dudintsev’s Not by Bread Alone (Ne khlebom edinym, 1956).29 Her translation activity therefore coincided with the years of the so-called Thaw (ottepel’), which marked, in the Soviet cultural field, phases when the easing of censorship gave hope for a liberal turning point and the restoration of freedom of speech—ultimately to be bitterly betrayed by increased control over the cultural life of the country. Despite the continuous fluctuation of Soviet cultural policies during those years (1956–66), Olsuf’eva consistently strove to give a voice to authors who could not be legally printed in the USSR. The long list of titles translated by her and published in Italy consists primarily of works that arrived clandestinely beyond the Iron Curtain (samizdat) or were printed abroad (tamizdat). She penned the first Italian translations of writers such as Andrei Platonov,30 Andrei Siniavskii,31 Valerii Tarsis,32 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn,33 Andrei Sakharov,34 Eduard Kuznetsov,35 and Vladimir Maksimov,36 to name only a few. However, she also translated official authors such as Andrei Voznesenskii,37 Iurii Bondarev,38 and even recipients of the Stalin Prize for Literature such as Veniamin Kaverin39 and Vera Panova.40 Various factors contributed to the disproportion between the official and unofficial Soviet texts translated by Olsuf’eva: the dynamics of the Italian publishing market as well as her personal involvement and interests, determined this imbalance.

From the publication of the first Italian tamizdat in 1957—Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago (Doktor Zhivago, 1957) published by Feltrinelli—a stream of uncensored Soviet literary texts began to flow clandestinely yet unstoppably from the USSR into the catalogues of Italian publishing houses. Indeed, Italy was one of the European countries where the publication of tamizdat flourished. This phenomenon involved both the main Italian publishing houses—like Mondadori, Einaudi and Il Saggiatore—and others founded at that time which specialised in the publication of uncensored Soviet literature, such as La Casa di Matriona and Jaca Book. Besides this specifically Italian impetus, another key factor was Olsuf’eva’s personal interest and direct involvement in the selection of translations. Thanks to her contact with numerous Soviet dissidents, she was able to pitch these texts to Italian publishers, often mediating between the latter, Soviet authors, and various transnational socio-cultural actors.

Her activity as a mediator and, not infrequently, as a literary agent for dissident writers intensified after her first institutional visit to Moscow at the invitation of Viktor Shklovskii, several of whose works she had translated for the De Donato publishing house.41 In December 1967, she wrote excitedly to Giampaolo Dossena—a Mondadori editor—that she would spend New Year in Moscow.42 Olsuf’eva often recalled that trip as a turning point in her professional and private life when she encountered several leading exponents of the Soviet intelligentsia:

I just happened, at the beginning, to meet Shklovskii […] and through him I met the first writers right at our home43 during a New Year’s party, where I also met Sakharov’s wife [Elena Bonnėr] […]. And since then, one thing leading to another, it has been a string of acquaintances that have given me a lot.44

Thanks to her friendship with the Sakharovs, her circle of acquaintances in Russia greatly expanded, soon including several groups of dissidents, especially Muscovites. Thanks to their intercession, when Solzhenitsyn signed a contract with Mondadori in 1974 for the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago, he requested that the translation be entrusted to her. The book caused quite a stir in the Italian press and public opinion,45 and Olsuf’eva gave several interviews explaining why Solzhenitsyn chose her as his Italian translator:

I don’t know Solzhenitsyn personally. I know him through the friends we have in common. First of all, the scientist Andrei Sakharov […]. It was Sakharov who told me about Solzhenitsyn during my visit to Moscow. […] Previously I had translated Cancer Ward, so I think that’s why Solzhenitsyn trusted me.46

This trust was later confirmed by the writer himself, as Olsuf’eva mentioned in a 1975 interview:

I personally met him [Solzhenitsyn] only in September, when he returned. He knew about me, I asked him why and with a smile he told me ‘when I was still allowed into the House of Writers, which as you know is your home, I heard about you and your translations and so I wanted you to be the translator of my works’. Needless to say, this gave me immense pleasure.47

Over time, the professional relationship between Olsuf’eva and Solzhenitsyn turned into friendship, thanks to the support that she offered the Soviet writer. Their closeness is evidenced not only by their correspondence, but also by the numerous letters that she received from editors and various Italian and international cultural personalities requesting her to act as an intermediary with Solzhenitsyn. Among Olsuf’eva’s personal papers is one particularly interesting letter from Giorgio Mondadori on 22 February 1974, ten days after Solzhenitsyn had been expelled from the USSR. The publisher offered his hospitality to the writer in his house near Verona, in order to show support at such a fraught moment. Giorgio Mondadori asked Olsuf’eva—then translating The Gulag Archipelago—to communicate his invitation to Solzhenitsyn.48 On 3 March, Olsuf’eva wrote to Solzhenitsyn attaching her Russian translation of the letter she received from Mondadori.49 The film director Franco Zeffirelli, in the days immediately following the expulsion of the Soviet writer from the USSR, also felt the need to express his solidarity by sending a telegram to Olsuf’eva’s Florentine address, in which he asked her, as a friend of the writer, to transmit his message of solidarity to Solzhenitsyn.50 Olsuf’eva’s friendly relations with other leading Soviet dissidents were also known outside Italy; for example, Patricia Blake, an American Slavic scholar specialising in dissident literature, wrote to her on 29 August 1971 requesting an interview about Solzhenitsyn (on whom Blake was writing a biography).51 Olsuf’eva told Blake that she had not yet had the pleasure of meeting the writer personally, but that she could help by sharing anecdotes she had heard from mutual friends. However, she asked Blake to keep her identity strictly confidential and not name her in the book as a source.52

Olsuf’eva’s international fame as a personality close to the circles of Soviet dissent increased further in 1975, the year when Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The physicist could not personally collect the award because the Soviet authorities had denied him permission to go abroad. His wife Elena Bonnėr—who, when he was proclaimed the winner of the Nobel Prize, was in Florence as Olsuf’eva’s guest to undergo an eye operation—went to Oslo in his stead. She chose Olsuf’eva to accompany her to the ceremony and interpret.

Fig. 4 King Olav V, M. Olsuf’eva and E. Bonnėr at the Nobel Prize ceremony, December 1975. Courtesy of Elena Bonnėr’s heirs. ©Norsk Telegrambyrå.

Fig. 5 M. Olsuf’eva sitting in the stalls during the Nobel Prize ceremony, December 1975. Courtesy of E. Bonnėr heirs. ©Norsk Telegrambyrå.

Fig. 6 E. Bonnėr at the Press Conference with M. Olsuf’eva in the background, December 1975. Courtesy of E. Bonnėr heirs. ©Norsk Telegrambyrå.

Olsuf’eva’s personal papers contain invitations to the official award ceremony and to the gala dinner;53 a signed typewritten copy in Russian and English of Sakharov’s lectio magistralis (Mir, progress, prava cheloveka—Peace, Progress, Human Rights); a copy of the speech given on that occasion by Elena Bonnėr; and a series of congratulatory letters and telegrams, including a letter from Nikita Struve congratulating Bonnėr and Olsuf’eva on their global celebrity, referring to the fact that the international press had published the official photographs of the awards ceremony in which both were portrayed alongside King Olav V of Norway.54

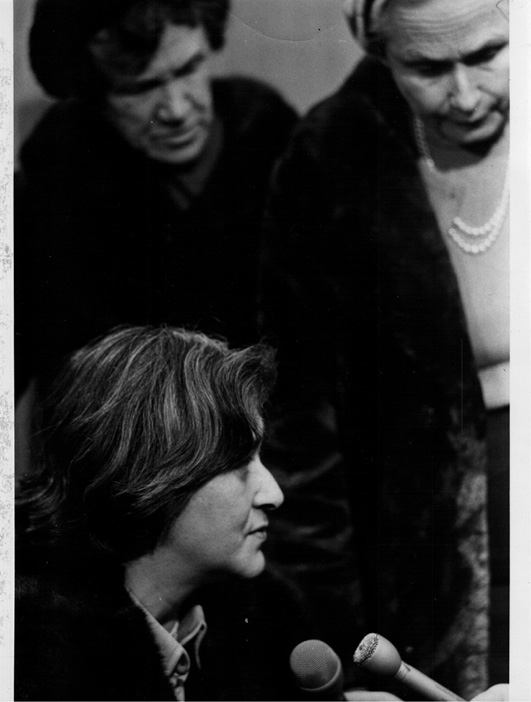

Thanks to her contacts with numerous Soviet dissidents (Sakharov, Bonnėr, Solzhenitsyn, Roy Medvedev, Andrei Amal’rik, Vladimir Bukovskii, and Natalia Gorbanevskaia, to name but a few) and with some of the most influential intellectual Russian émigrés in the West (including Nikolai Struve, Marc Slonim and Zhores Medvedev), Olsuf’eva soon became a key contact for anyone seeking to contact Soviet dissidents at home or abroad. Italian publishers interested in samizdat wrote to her, as did journalists, intellectuals, and politicians. On 30 January 1974, for example, the journalist Enrico Romero—author and director of a series of interviews dedicated to Soviet dissidents, broadcast by the Swiss-Italian radio and television station (RSI)—wrote mentioning Medvedev’s willingness to be interviewed if Olsuf’eva acted as an interpreter and mediator.55 Olsuf’eva’s work with RSI is evidenced not only by this correspondence with Romero, but also by an interview with Bonnėr that aired in February 1976, in which Olsuf’eva is filmed with Bonnėr. In fact, the interview took place in Olsuf’eva’s house in Florence.

Fig. 7 Frame from E. Romero’s interview with E. Bonnėr (on the left), accompanied by M. Olsuf’eva (on the right), 1976. Courtesy of RSI.

Further proof of Olsuf’eva’s activity as a cultural intermediary is found in her correspondence with Sergio Jacomella—the director of a Swiss-Italian socio-cultural cooperative—who, between 1974 and 1977, organised in Lugano a series of meetings with major Soviet dissidents. Jacomella praised her “invaluable mediation” and “precious collaboration” in meetings with Aleksandr Galich and others.56 Olsuf’eva also corresponded with Giovanni Volpe—publisher and founder of the Gioacchino Volpe Foundation—who wrote to her seeking contact details for dissidents whom he wished to invite to the conference ‘Order and Disorder’ (‘Ordine e disordine’), which was to be held in Rome in April 1979.57 In her reply, Olsuf’eva suggested inviting the poets Natalia Gorbanevskaia and Naum Kozhavin; she furnished Volpe with their addresses, as well as Vladimir Bukovskii’s.58 Even Ronald Reagan resorted to Olsuf’eva to contact Soviet dissidents directly: when he first stood for the presidency of the United States (1975), he tasked Senator James Buckley with sending an article about Sakharov to Bonnėr via Olsuf’eva’s Florentine address.

These close friendships with Soviet dissidents allowed Olsuf’eva to play a fundamental role in the circulation and diffusion of samizdat in Western Europe, not only pitching the translation of their works to Italian publishers, but also often acting as their literary agent, representative, and copyright protector. Several times Olsuf’eva took the initiative of pitching the translation of books that interested her or of samizdat manuscripts that had come into her possession to different publishing houses, as in the case of Anatolii Marchenko’s Testimonies (Moi pokazaniia, 1969), which she introduced to Il Saggiatore thus:

Following the telephone conversation of 20 February [1969] with Miss De Vidovich [editor of Russian literature], I hasten to send you the typescript (photocopied) of the book, unpublished in the USSR, Anatolii Marchenko’s Testimonies, which I received from Nikita Struve in Paris. [...] if the book rights have not yet been acquired by some other publisher, I would deem it appropriate and urgent to translate it.

However, her proposal was rejected by the publishing house on the grounds that the work had “a more scandalous than literary nature”. In 1977, she pitched to the Florentine publishing house Editoriale Nuova two non-fiction books by Valerii Chalidze (The Legal Situation of Workers in the USSR and Criminal Russia: Essays on Crime in the Soviet Union): the editorial director Giampaolo Martelli thanked her and requested the original manuscripts in order to submit them to his editorial consultants, a request that Olsuf’eva satisfied by sending the manuscripts in her possession. Martelli’s letter reveals his keenness to stay updated about “the most significant books by Soviet authors who turn to you for the publication of their works in Italy”, while demonstrating how editors held Olsuf’eva’s collaboration in high esteem.

One of the authors who benefited most from Olsuf’eva’s intermediation was undoubtedly Eduard Kuznetsov; their substantial correspondence (1972–80) attests to their friendship.59 In 1972, Olsuf’eva personally undertook to publish Kuznetsov’s diary of his years of imprisonment in a labour camp in Mordovia. Olsuf’eva’s 1972 translation for the publisher Longanesi, as Without Me. Diary of a Soviet Concentration Camp, 1970–1971 (Senza di me. Diario di un campo di concentramento sovietico, 1970–1971), was a world première. Her correspondence with Longanesi clearly shows that the proposal was pitched by Olsuf’eva herself.60 The most interesting aspect of this correspondence is Olsuf’eva’s role as the author’s literary agent, providing the publishing house with detailed information on the remuneration to be paid to the author through her:

We agreed that as copyright fees for publishing the work, you will pay me the lump sum of 1,000,000 lire. This amount includes my translation into Italian and any amount due on the work up to 10,000 copies of your edition. Beyond this amount, you will pay me an 8% stake on the cover price of each copy sold. For any other use of the work, in any language and any form, you will reserve for me 50% of the net revenue.61

Olsuf’eva frequently reiterated the need to protect the rights of Soviet authors, well aware of the difficulty experienced even by officially approved writers in receiving copyright fees across the Iron Curtain. She often acted as their guarantor, offering to personally collect their fees and to send them on to the recipients, sometimes even advancing money out of her own pocket.62 One such example is her correspondence with Bulat Okudzhava, several of whose poems she translated: Okudzhava, through his wife, asked her to help him obtain his copyright fees.63 Olsuf’eva repeatedly used his fees to buy and send on garments for the Okudzhavas; she also personally brought his money to Russia.64 Confirming Olsuf’eva’s helpfulness, a 1977 letter from Bonnėr’s son-in-law, Efrem Jankelevich, mentions that Bonnėr hoped to be able to travel to Italy using the fee for the translation of an article by Sakharov.65

Olsuf’eva also carried out an important role as an intermediary between Soviet authors and their Western literary agents, as evidenced by a letter sent on behalf of Bonnėr to the literary agent Eric Linder.66 Here Olsuf’eva was passing on a request from Bonnėr to the agent: since the Garzanti publishing house had rejected Sakharov’s My Country and the World (lI mio paese e il mondo, 1975), Bonnėr wanted another firm, Rusconi, to option it.

Another relevant aspect of Olsuf’eva’s cultural activity was her commitment to disseminating samizdat and tamizdat works not only in Italy, but abroad. By exploiting her personal acquaintance with numerous cultural agents, Olsuf’eva was able to advertise the tamizdat publication of Kuznetsov’s Diary which, as we have seen, was first published thanks to her mediation. In a letter to the publisher Mario Monti on 25 November 1972, Olsuf’eva proposed sending this tamizdat work to Time correspondent Patricia Blake and to the editors of the Nouvel Observateur, who were keen to run a review of Kuznetsov’s work.67

I have shown that Olsuf’eva’s agency as a cultural actor was not limited to translation, but also included various editorial activities, such as pitching texts to publishers on her own initiative and offering to mediate with and on behalf of Soviet authors about copyright issues, as well as promoting tamizdat works in the national and international press. Another significant side of her commitment as a social actor was her work for Amnesty International, which facilitated her representation of Soviet dissidents in Italy. As such, Olsuf’eva exemplified the role of a “gatekeeper”.68

Social Activity and Activism

From the late 1960s onwards, Mariia Olsuf’eva was committed to defending human rights in the USSR: she helped promote a series of international campaigns and mobilisations supporting political prisoners and other victims of Soviet authorities. In 1968 she became the spokesperson for an initiative promoted by Marc Slonim to support Solzhenitsyn at the Mondadori publishing house.69 Slonim’s letter, translated into Italian by Olsuf’eva and enclosed with her own message,70 was a last-ditch attempt to stop the oppression to which Solzhenitsyn was subjected in the USSR: Slonim proposed to send, on the occasion of Solzhenitsyn’s fiftieth birthday (11 December 1968), a series of telegrams from writers, translators, professors, editors and any other cultural actors in Europe and the United States to the Writers’ Union and to the Literaturnaia gazeta. It was hoped that this show of European intellectuals’ genuine commitment to Solzhenitsyn and his protection could not fail to impress the Party leaders.71 Thanks to mediation by Olsuf’eva and by the literary agent Eric Linder,72 the Mondadori Director of the Foreign General Secretariat Glauco Arneri and the Editorial Directors Donato Barbone and Vittorio Sereni joined the initiative.73

In 1980, Olsuf’eva personally promoted an international protest campaign against the escalation of the persecutions suffered by the Sakharovs, now in internal exile in Nizhnii Novgorod, the birthplace of Gorky. On 19 February, Olsuf’eva sent three telegrams from her Florentine address to, respectively, Iurii Andropov,74 the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, and the Procurator-General Roman Rudenko. The first two cables, in Italian, were sent on behalf of the Florentine branch of Amnesty International, which she had helped found in 1977; the third, in Russian, was signed personally by her. A few days later, Olsuf’eva began collecting signatures, campaigning for the Sakharovs. This campaign soon involved several Italian MPs, as shown by letters exchanged with the Christian Democrat member of parliament Gianni Cerioni and his assistant, Giuseppe Fortunato. On 23 February, on behalf of Cerioni, Fortunato sent Olsuf’eva several documents with official Italian Chamber of Deputies headers, to be used for messages signed by the Italian MPs; on 25 February, Olsuf’eva sent to Cerioni three letters she had written (in Italian and Russian) to be addressed to Gromyko, Anatolii Aleksandrov (the President of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR), and Iurii Khristoradnov (the First Secretary of the CPSU Gorky City Committee). She also promoted this campaign with Italian editors: one letter from the publishing house Città Armoniosa reported that “about Sakharov we filled out a lot of the sheets that you sent to us. About 500 signatures”. In those years, she also collaborated with Amnesty regularly as a translator and interpreter.75

As with her cultural activity, Olsuf’eva’s varied work as a social actor and human rights activist kept her occupied on several fronts simultaneously. On 15 February 1974, the British newspaper The Guardian published Sakharov’s ‘Appeal from Moscow’, in which he protested against the arrest of Solzhenitsyn and requested the publication of The Gulag Archipelago in the USSR. Olsuf’eva was mentioned in the article because Sakharov had dictated the text of his appeal to her over the phone, so that it could be disseminated in the West.76 The Italian press also mentioned Olsuf’eva, quoting her in numerous articles relating to human rights in the USSR, or publishing photographs that portrayed her in the company of important Soviet dissidents and human rights activists. On 13 September 1977, during Bonnėr’s second stay in Florence, La Nazione reported on her meeting with the city’s mayor, Elio Gabbuggiani, publishing a picture of the two in Olsuf’eva’s company alongside its article.77 She was once again interpreting, having also organised the meeting.

On 22 March 1978, La Nazione wrote about an institutional visit to Florence by the General Secretary of Amnesty International, Martin Ennals: Olsuf’eva was present on that occasion too, not only as an interpreter, but as a member of Amnesty International and co-founder of its Florentine Group.78 In 1977, she also committed herself to protecting the families of political prisoners in the USSR, launching an international aid campaign. Among the papers relating to her activity as a member of Amnesty International are two letters with the names and addresses of the families of political convicts which request the recipients (other Amnesty co-ordinators) to deliver staple goods via tourists visiting the USSR and other occasional travellers.79 The list of desired goods, which Olsuf’eva received from Bonnėr, contained shoe and clothing sizes for the Russian end users.80 She therefore aimed to provide support to Soviet dissidents and their families via every possible route, promoting international campaigns in their favour so as to raise public awareness, as well as offering pragmatic material help, such as clothes parcels and other goods.

Conclusion

Olsuf’eva’s case exemplifies “the active and often physical contribution”81 made by individuals involved in the cross-border flow of samizdat and tamizdat, a transnational community composed of many émigrés from different waves of the Russian diaspora. Their role has been described thus by Kind-Kovács:

The role of émigrés was one, if not the most crucial element in the initiation and maintenance of cross-cultural literary entanglements. While the community across the “Other Europe” was one of discourses and ideas, through the West this virtual community developed into a tangible collective. The long-term presence of émigrés created the foundations for cross-border communication.82 [original italics]

As we have seen, in fact, it was also thanks to Olsuf’eva’s network of contacts from the different waves of Russian emigration to Europe and the United States that she was able to obtain manuscripts smuggled out of the USSR, which she then pitched to Italian publishing houses and, ultimately, translated. Therefore, besides her roles as a translator and intercultural mediator, she was actively involved in the production, dissemination, and reception of samizdat and tamizdat and, last but not least, as an activist defending human rights in the USSR.

In the transnational distribution of uncensored Soviet literature (nepodtsenzurnaia literatura), the translator’s role was not limited to linguistic and cultural mediation. In the case of samizdat and tamizdat, we have seen that the translator was often one of the main actors within that ‘transnational community’ which enabled the circulation of cultural goods and ideas on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Thus, when considering the production, dissemination and reception of the ‘other literature’ between the ‘two Europes’, it is important to rethink the role of the translator, as a transnational (non-state) actor of cultural diplomacy.83 Reframing the translator’s role in this way would moreover enrich the field of cultural Cold War studies, which has often wrongly regarded translators as marginal to the production, dissemination and reception of unofficial Soviet culture across the Iron Curtain.84

1 Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere, ‘Introduction: Proust’s Grandmother and the Thousand and One Nights: The “Cultural Turn” in Translation Studies’, in Translation, History and Culture, ed. by Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere (London: Pinter, 1990), pp. 1–13. See also Susan Bassnett, ‘The Translation Turn in Cultural Studies’, in Constructing Cultures: Essays On Literary Translation, ed. by Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1998), pp. 123–40.

2 Theo Hermans, ‘Translation as Institution’, in Translation as Intercultural Communication, ed. by Mary Snell-Hornby, Zuzana Jettmarová and Klaus Kaindl (Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 1997), pp. 3–20 (p. 10).

3 Michaela Wolf, ‘Introduction: The Emergence of a Sociology of Translation’, in Constructing a Sociology of Translation, ed. by Michaela Wolf and Alexandra Fukari (Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 2007), pp. 1–36 (p. 1).

4 Reine Meylaerts, ‘Translators and (Their) Norms’, in Beyond Descriptive Translation Studies, ed. by Anthony Pym, Miriam Shlesinger and Daniel Simeoni (Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 2008), pp. 91–102 (p. 91).

5 Daniel Simeoni, ‘The Pivotal Status of the Translator’s Habitus’, Target, 10:1 (1998), 1–39 (p. 38).

6 Meylaerts, ‘Translators and (Their) Norms’, p. 91.

7 Michaela Wolf, ‘Introduction: The Emergence of a Sociology of Translation’, p. 4.

8 An interesting sociological study of this type was recently published by Cathy McAteer, who, focusing her attention on the ‘social identity’ of certain Russian-to-English translators in the twentieth century, highlighted their personal contribution in the reception of translated literature abroad. See Cathy McAteer, Translating Great Russian Literature. The Penguin Russian Classics (London and New York: Routledge BASEES Series, 2021), esp. Chapter 2, ‘David Magarshack: Penguin Translator Becomes Translation Theorist’, pp. 43–87, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-mono/10.4324/9781003049586-2/david-magarshack-penguin-translator-becomes-translation-theorist-cathy-mcateer?context=ubx&refId=d79d056f-bf7a-4602-ab6c-b13b0fc7af92.

9 On the Iron Curtain’s “permeability”, see Friederike Kind-Kovács, ‘Crossing Germany’s Iron Curtain. Uncensored Literature from the GDR and the Other Europe’, East Central Europe, 41 (2014), 180–203 (p. 180) and Friederike Kind-Kovács and Jesse Labov, ‘Samizdat and Tamizdat. Entangled Phenomena?’, in Samizdat, Tamizdat and Beyond: Transnational Media During and After Socialism, ed. by Friederike Kind-Kovács and Jesse Labov (New York: Berghahn, 2013), pp. 1–23.

10 György Péteri, ‘Nylon Curtain–Transnational and Transsystemic Tendencies in the Cultural Life of State-Socialist Russia and East-Central Europe’, Slavonica, 10:2 (2004), 113–23.

11 Olga Zaslavskaya, ‘Samizdat as Social Practice and Communication Circuit’, in Samizdat: Between Practices and Representations, ed. by Valentina Parisi (Budapest: Central European University, 2015), pp. 87–99 (p. 87), https://ias.ceu.edu/sites/ias.ceu.edu/files/attachment/article/421/valentinaparisisamizdat.pdf.

12 Friederike Kind-Kovács, ‘Tamizdat: A Transnational Community’, in F. Kind-Kovács, Written Here, Published There: How Underground Literature Crossed the Iron Curtain (Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, 2014), pp. 83–208.

13 Valentina Parisi, ‘Viaggio nella vertigine di Evgenija Ginzburg come esempio di socializzazione transnazionale dei testi’, eSamizdat, IX (2012–13), 77–85.

14 Olsuf’eva’s personal papers are stored at the Contemporary Archive ‘Alessandro Bonsanti’ of the Gabinetto G. P. Vieusseux (ACGV) in Florence, Italy.

15 The archival funds of the publishing houses Mondadori and Il Saggiatore are stored at the Arnoldo and Alberto Mondadori Foundation (FAAM) in Milan, Italy.

16 Jeremy Munday, ‘Using Primary Sources to Produce a Microhistory of Translation and Translators: Theoretical and Methodological Concerns’, The Translator, 20:1 (2014), 64–80 (p. 73).

17 See Stefania Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva nell’Archivio Contemporaneo Gabinetto G. P. Vieusseux (Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 2002), p. 7; Mariia V. Olsuf’eva-Mikaėllis, ‘Moim detiam’, in D. A. Olsuf’ev, Vechnyi kover zhizni: Semeinaia khronika, ed. by M. Talalaia (Moscow: Indrik, 2016), pp. 369–84 (p. 369, p. 372).

18 Mariia V. Olsuf’eva-Mikaėllis, ‘Moim detiam’, p. 376.

19 Enrico Romero, ‘Intervista a Maria Olsufieva’, Incontri. Fatti e personaggi del nostro tempo, Radio-Televisione della Svizzera Italiana (RSI), 29 September 1975.

20 Ibid.

21 Grazia Gobbi Sica, In Loving Memory: Il cimitero degli allori di Firenze (Florence: Leo S. Olshki, 2016), p. 97, p. 283.

22 See Romero, ‘Intervista a Maria Olsufieva’; Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva, p. 8.

23 Sakharov’s widow Elena Bonnėr wrote in her memoirs that Mariia Olsuf’eva, her niece Elena Borghese and her friend Nina Kharkevich used to visit the Sakharovs in Moscow twice a year, from 1968 until 1973, when Mariia and Nina were stopped at Soviet customs with a “load of samizdat” and, consequently, were banned from the USSR. See Andrei Sakharov, Elena Bonnėr i druz’ia: zhizn’ byla tipichna, tragichna i prekrasna, ed. by B. Al’tshchuler and L. Litinskii (Moscow: AST, 2020).

24 Romero, ‘Intervista a Maria Olsufieva’. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own. Olsuf’eva is still “Solzhenitsyn’s voice in Italy”: her translation of The Gulag Archipelago is the only Italian version of this key work by the Russian writer, and it is still in print. See, for example, the latest reprint of Olsuf’eva’s translation in a revised and supplemented version by Maurizia Calusio, published in Mondadori’s ‘I meridiani’ series as A. Solženicyn, Arcipelago Gulag, trans. by M. Olsuf’eva (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 2001).

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva, p. 144.

28 Antonella d’Ameliia, ‘Olsuf’eva Mariia Vasil’evna’, Russkoe prisutsvie v Italii v pervoi polovine XX veka. Entsiklopediia, ed. by A. D’Ameliia and D. Ritstsi (Moscow: ROSSPĖN, 2019), pp. 490–91 (p. 490).

29 V. Dudincev, Non si vive di solo pane [Ne khlebom edinym], trans. by M. Olsuf’eva (Firenze: Centro internazionale del libro, 1957). The novel also appeared in the US and London that same year in Edith Bone’s English translation, with E.P. Dutton and Hutchinson respectively.

30 Andrej Platonov, Nel grande cantiere [Kotlovan, 1969], trans. by M. Olsuf’eva (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1969); Andrej Platonov, Il villaggio della nuova vita [Chevengur, 1972], trans. by M. Olsuf’eva (Milan: Mondadori, 1972). Olsuf’eva’s translation preceded the first English translation by Thomas Whitney by four years. Published by Ardis in 1973, Whitney’s translation was succeeded in 1975 by Mirra Ginsburg’s version for E.P. Dutton.

31 Andrej Sinjavskij, La gelata [Fantasticheskie povesti, 1961], trans. by M. Olsuf’eva (Milan: Rizzoli, 1962).

32 Valerij Tarsis, La mosca azzurra [Skazanie o sinei mukhe, 1963], trans. by M. Olsuf’eva, (Milan: Rizzoli, 1964).

33 This was Divisione cancro [Rakovyi korpus, 1968], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1968) and ostensibly authored by ‘Anonimo sovietico’. This was the same year that Lord Nicholas Bethell’s and David Burg’s translation of Cancer Ward appeared in English, published by The Bodley Head. Other Solzhenitsyn translations which she completed include Aleksandr Solženicyn, Vivere senza menzogna [Zhit’ ne po lzhi, 1974], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1974); A. Solženicyn, Arcipelago Gulag, vol. 1 [Arkhipelag GULAG, 1973], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1974); A. Solženicyn, Lettera ai dirigenti dell’Unione Sovietica [Pis’mo vozhdiam Sovetskogo Soiuza, 1974], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1974); A. Solženicyn, Arcipelago Gulag, vol. 2 [Arkhipelag GULAG, 1974], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1975); A. Solženicyn, La quercia e il vitello: saggi di vita letteraria [Bodalsia telënok s dubom, 1975], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1975); A. Solženicyn, Arcipelago Gulag, vol. 3 [Arkhipelag GULAG, 1975], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1978). Thomas Whitney’s English translation of The Gulag Archipelago (New York: Harper and Row, 1973) appeared only a year before Olsuf’eva’s.

34 Andrei Sacharov, Il mio paese e il mondo; Progresso, coesistenza e libertà intellettuale [O strane i mire, 1975; Razmyshleniia o progresse, mirnom sosushchestvovanii i intellektual’noi svobode, 1968], trans. by M. Olsufieva and C. Bianchi (Milan: Euroclub, 1976); A. Sacharov, Un anno di lotta di Andrej Sacharov [Trevoga i nadezhda: Odin god obshchestvennoi deiatel’nosti A. Sakharova, 1978], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Milan: Bompiani, 1977).

35 Eduard Kuznetsov, Senza di me: diario da un lager sovietico 1970–71 (Dnevniki, 1973), trans. by M. Olsufieva and O. Michahelles (Milan: Longanesi, 1972).

36 Vladimir Maksimov, La quarantena [Karantin, 1973], trans. by M. Olsufieva and O. Michahelles (Milan: Rusconi, 1975).

37 Andrej Voznesenskij, Scrivo come amo [Pishetsia kak liubitsia], trans. by M. Olsoufieva and M. Socrate (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1962).

38 Iurii Bondarev, Il silenzio [Tishina, 1962], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Milan: Rizzoli, 1962).

39 Veniamin Kaverin, Sette paia di canaglie [Sem’ par nechistykh, 1962], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Milan: Rizzoli, 1962).

40 Vera Panova, Sergio [Serezha, 1955], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1965).

41 Viktor Shklovskii, Una teoria della prosa [O teorii prozy, 1929], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Bari: De Donato, 1966); V. Shklovskii, Viaggio sentimentale [Sentimental’noe puteshestvie, 1923], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Bari: De Donato, 1966); V. Shklovskii, La mossa del cavallo [Khod konia, 1923], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Bari: De Donato, 1967); V. Shklovskii, Majakovskij [O Maiakovskom, 1940], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1967); V. Shklovskii, Il punteggio di Amburgo [Gamburskii schët, 1928], trans. by M. Olsoufieva (Bari: De Donato, 1969); V. Shklovskii, Marco Polo [Marko Polo razvedchik, 1931], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Mondadori, 1972); V. Shklovskii, Tol’stoj [Lev Tol’stoi, 1963], trans. by M. Olsufieva (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1978).

42 Florence, Archivio Contemporaneo ‘Alessandro Bonsanti’ Gabinetto G. P. Vieusseux (ACGV), Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.3.15.

43 Here Olsuf’eva refers to the fact that, by a curious chance, the House of Writers (Dom Literatorov) in Moscow, where all the official ceremonies of Soviet literati took place (including New Year celebrations which she herself attended several times) had its headquarters in Povarskaia Street, in the very building which had been the Olsuf’ev Palace before they fled Russia. Olsuf’eva repeatedly mentioned the toast that Shklovskii dedicated to her during the celebrations of 1 January 1968, calling her “the landlord”, and how, as soon as word got out that the granddaughter of the old owner (Count Olsuf’ev) was present in the room, everyone raised their glasses in greeting: “I spent in that house three New Years, always invited by fellow writers of the Union [of Soviet Writers]. And it is funny that every time, as soon as word got around that the old owner was present [...] a line of people would form in front of me, with full mugs, to greet me joyfully, to toast my health, as if indeed for a moment they were once again the guests of an Olsuf’ev. Funny, isn’t it?”. Claudio Serra, ‘Solgenitsin ha voluto lei’, L’Europeo, 7 February 1974, 48–51 (p. 48).

44 Romero, ‘Intervista a Maria Olsufieva’.

45 On the reception in Italy of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, see: A. Reccia, ‘Narrazione del silenzio e dibattito nella prima ricezione di Arcipelago Gulag in Italia’, in Lo specchio del Gulag in Francia e in Italia, ed. by Luba Jurgenson and Claudia Pieralli (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2019), pp. 323–42.

46 Mario Pancera, ‘Intervistata a Firenze la signora russa che ha tradotto “Gulag”’, Corriere d’informazione, 13 February 1974, p. 3.

47 Romero, ‘Intervista a Maria Olsufieva’.

48 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL. 3.12.19.

49 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL. 3.12.21.

50 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.3.9.

51 Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva, pp. 135–36. A footnote to Blake’s review of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago informed the reader that “[Blake herself] is writing a biography of Solzhenitsyn” (New York Times Book Review, 26 October 1975, 1). However, no trace of this volume has been found either in Blake’s bibliography, or in the general bibliography on Solzhenitsyn: probably, the book remained unpublished, although Blake had worked on it for several years.

52 Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva, pp. 136–37.

53 The following references are located in ACGV. For the invitations Olsuf’eva received to attend the award ceremony, see OL.2.2.16, and for the gala dinner OL.2.2.18. For the signed copy of Sakharov’s lectio magistralis, see OL.2.2.20 and Bonnėr’s speech OL.2.2.19. For examples of congratulatory letters and telegrams, see OL.2.2.24.

54 See, for example: Russkaia mysl’, December 1975; Herald Tribune, 11 December 1975.

55 AGCV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.4.9.

56 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL. 2.4.19.

57 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL. 2.4.47a. Given that papers by Soviet dissidents were not published in the conference proceedings (Ordine e disordine. Settimo incontro romano, 1977, Roma: Giovanni Volpe Editore, 1980) and none is mentioned in the list of participants (Ordine e disordine, p. 217), one might reasonably assume that the Soviet dissidents did not take part in the conference sessions.

58 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL. 2.4.47b.

59 The following references concerning Olsuf’eva’s mediation with Soviet dissidents are located at ACGV. For more on President Reagan, Senator Buckley and Olsuf’eva, see OL. 2.2.14a and OL.2.2.14b. For more on Olsuf’eva’s Marchenko pitch to Il Saggiatore, see OL. 3.15.70, and regarding the publisher’s rejection of the work as more scandalous than literary, see OL.3.15.73. For correspondence between Martelli and Olsuf’eva, see OL. 3.7.1. and OL. 3.7.2. On Olsuf’eva’s friendship with Eduard Kuznetsov, see OL.3.28.

60 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.3.11.30.

61 Ibid.

62 Pavan, Le carte di Marija Olsuf’eva, p. 30.

63 Ibid., p. 78.

64 Ibid., p. 79.

65 Ibid., p. 98; ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.2.25.

66 The letter is stored in the archive of the International Literary Agency (Agenzia Letteraria Internazionale, ALI) at the Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori (FAAM) in Milan. FAAM, Agenzia Letteraria Internazionale–Erich Linder, Serie annuale 1975, b. 54, f. 10 (Maria Olsufieva).

67 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.3.11.34.

68 William Marling, Gatekeepers: The Emergence of World Literature and the 1960s (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

69 FAAM, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Area Editoriale Marco Polillo, Solženicyn, serie non-ordinata, 32b.

70 FAAM, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Area Editoriale Marco Polillo, Solženicyn, serie non-ordinata, 32c.

71 Ibid.

72 FAAM, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Area Editoriale Marco Polillo, Solženicyn, serie non-ordinata, 32a.

73 A copy of the cable sent by Vittorio Sereni on that occasion is stored at the Arnoldo Mondadori Foundation: FAAM, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Direzione Letteraria Vittorio Sereni, Solzhenitsyn, 26/20. See also: FAAM, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Area Editoriale Marco Polillo, Solženicyn, serie non-ordinata, 32; 32b.

74 The archival references relevant to this paragraph are all located at ACGV. For Olsuf’eva’s telegram to Andropov, see OL.2.2.56; to Gromyko, see OL.2.2.55; to Rudenko, see OL.2.2.54. For Fortunato’s documents to Olsuf’eva, see OL.2.2.57. Olsuf’eva’s letters to Gromyko via Cerioni are found at OL.2.2.61; her letters to Aleksandrov are found at OL.2.2.60; and her letters to Khristoradnov are at OL.2.2.59. The letter from Città Armoniosa can be found at OL.3.5.24a.

75 In January 1980, Olsuf’eva wrote to Leoni that she was working on an urgent translation of Amnesty International’s annual report on the USSR (ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.3.5.21); on another occasion, she also mentioned her participation as an official interpreter in the Sakharov Hearings, which were held in Washington in 1979 (ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.3.5.20).

76 William L. Webb, ‘Dissidents Challenge the Kremlin’, The Guardian, 15 February 1974, https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2013/feb/13/alexander-solzhenitsyn-arrest-1974-archive.

77 ‘Elena Sakharova dal sindaco’, La Nazione, 13 settembre 1977.

78 ‘Il rapporto annuale sui diritti dell’uomo’, La Nazione, 22 marzo 1978.

79 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.1.3; ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.1.4.

80 ACGV, Marija Olsuf’eva, OL.2.4.50.

81 Friederike Kind-Kovács, Written Here, Published There, p. 220.

82 Kind-Kovács, Written Here, p. 155.

83 See, for example, Giles Scott-Smith’s essay ‘Opening Up Political Space: Informal Diplomacy, East-West Exchanges and the Helsinki Process’, in Beyond the Divide. Entangled Histories of Cold War Europe, ed. by Simo Mikkonen and Pia Koivunen (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2015), pp. 23–43; and various essays in Entangled East and West: Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Interaction during the Cold War, ed. by Simo Mikkonen, Giles Scott-Smith and Jari V. Parkkinen (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2019).

84 On the cultural Cold War, see The Cultural Cold War in Western Europe 1945–1960, ed. by Giles Scott-Smith and Hans Krabbendam (Portland: Frank Cass, 2003); Across the Blocs. Cold War Cultural and Social History, ed. by Rana Mitter and Patrick Major (Portland: Frank Cass, 2004); and Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West, ed. by Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith and Joes Segal (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012). See also Esmaeil Haddadian-Moghaddam and Giles Scott-Smith, ‘Translation and the Cultural Cold War. An Introduction’, Translation and Interpreting Studies, 15:3 (2020), Special Issue: Translation and the Cultural Cold War, 325–32.