The Visibility of the Translator: A Case Study of the Telugu Section in Progress Publishers and Raduga

©2024 Anna Ponomareva, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0340.26

Introduction

Lawrence Venuti’s book The Translator’s Invisibility opened a new era in Translation Studies by emphasising the importance of translators in the creation of literature in translation.1 Jeremy Munday’s ideas on microhistory have also contributed to this turn.2 His translator works in a particular social and historical environment. Gengshen Hu, a scholar from China, offers a bird’s-eye view of translation and the translator. His book Eco-Translatology: Towards an Eco-paradigm of Translation Studies provides a wider context for the translator by considering the publishing industry, cultural policies, and readers’ expectations as formative aspects of his environment.3 Both theories allow me to analyse my experience of working in the Telugu sections of Progress and Raduga, the biggest publishing houses to specialise in literature in translation in the USSR, between 1979 and 1991.

I will present my recollections as a microhistorical case study in which several era-specific elements are explored: the inner workings of the publishing houses, the translators and translation teams, and the importance of their collaboration with each other. Additionally, the voices of our Telugu readers will be heard, and I shall conclude my study by pointing to the impact of Russian literature in translation on readers.

Translation as Ideology

Progress Publishers (formerly Foreign Literature Publishing House) was established in 1931 as another attempt to re-invent Maksim Gorky’s World Literature (‘Vsemirnaia literatura’) project, the first publishing house in Soviet Russia (1918–24).4 Later, in 1956, Progress Publishers formed its Telugu section. Then, in 1980, this section was divided when Progress was split into two publishing houses, Progress Publishers (specialising in literature of philosophy, social sciences, and politics) and Raduga (which focused on various types of fiction and children’s literature). Both publishing houses were funded by the Soviet government, and their role could easily be categorised as a form of soft power. Soviet translated books helped the authorities to create the image of a progressive and peaceful state which supported other countries in developing their literature by spreading leftist ideas and introducing their young readers to education by reading good quality books.

In 2011, the CIA released a sanitised copy for publication online of its 1985 report, The Soviets in India: Moscow’s Major Penetration Program.5 The report has a chapter which, in the spirit of the Cold War period, is called ‘Soviet Propaganda and Disinformation Activities’ (pp. 6–16). It includes a section dedicated to the publishing activities of the former USSR, one of which was the organisation of international bookfairs. Page 16 of the report reproduces a poster (Figure 1) that references the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation (signed in August 1971) in its advertisement for an Indo-Soviet book fair in Chennai (formerly Madras) in 1984.

Fig. 1 Poster advertising Soviet books.6

The report also names Mezhdunarodnaia Kniga as “the Soviet agency that organizes bookfairs in India and distributes books at cut-rate price through USSR bookstores and Indian book-stalls”.7 Earlier in the text, in a section titled ‘The Two Communists Parties’ (in the chapter on ‘Funding Political Parties and Politicians’), the exact figure of this cut-rate price is named as “a 60- or 65-percent discount which was offered to People’s Publishing House (PPH), an Indian company wholly owned by CPI”.8

The abbreviation CPI stands for the Communist Party of India, one of several Communist parties in the country. Chandra Rajeswara Rao (1914–94) was the General Secretary of this party for many years, from 1964 to 1990. He was a Telugu native speaker. When he visited the Soviet Union, Comrade Rao always tried to find time in his busy schedule, in particular during CPSU party congresses in Moscow, to see his “Russian Telugu girls”. He used this gender- and age-specific expression since, at the time when I worked there, both Telugu sections (at Progress and Raduga) were composed entirely of female staff.9 These rare meetings with the general secretary of the CPI were perhaps the only opportunities for us to understand and maintain our ideological mission as part of the propaganda machine of the Soviet state. The rest of our time was dedicated to translation as a cultural and educational activity.

Translation as Publishing Business

The Telugu sections at Progress and Raduga were formed of teams of professional staff. Our in-house translators were all native Telugu speakers and Indian left-wing or progressive intellectuals. Some of them were literary figures in their own region. For example, Srirangam Srinivasa Rao (1910–83), popularly known as Sri Sri, an Indian poet and lyricist (and no relation to Comrade Rao), worked with us in the early 1970s. All of our chief editors were Russian native speakers who were also fluent in Telugu and English. We used the English translations of books originally written in Russian as our source texts. Svetlana Dzenit, the founder of the Telugu section and its first head, had a degree in English and studied Telugu with Telugu specialists who lived and worked in Moscow in the 1950s. According to her experience, in addition to two- to three-hour Telugu lessons with a native-speaking tutor on Sundays, all staff members were required to study independently. Dzenit writes: “There were the Arden grammar book, published at the beginning of the 20th century, and Telugu-English Dictionary by Professor P. Sankaranarayana”.10 Later, Dzenit published her own Russian-Telugu dictionary.11

Other senior colleagues, Olga Barannikova, Tamara Kovaleva, and Olga Smyslova, who were chief editors, studied Telugu at St Petersburg University with Nikita Gurov (1935–2009), who established the discipline of Telugu studies there in 1962. Their knowledge of Telugu helped them to communicate with native Telugu translators and participate actively in editing translators’ drafts. They were translators themselves, and published their translations of Telugu novels and poetry into Russian. However, copy editors, such as Valeriia Kozlenko and Natasha Mikhnevich, did not have degrees in Telugu but learned the language on the job. They were responsible for maintaining the quality of publication standards, largely in terms of their technical requirements and terminology control, but not necessarily focusing on the linguistic or political peculiarities of the translated text.

The next group of colleagues were the youngest who, due to their age and experience, worked as copyists and proof-readers. They usually came to work immediately after finishing their high-school education. They spent a month or so familiarising themselves with the Telugu alphabet and then started to work by providing neat copies of translators’ drafts. Neither publishing house had typewriters or computers equipped for Telugu script. In Raduga, Olesia Medvedeva, Tania Mramornova, and I copied by hand into Telugu many manuscripts which were translations of Russian and Soviet fiction (for example, novels by Lev Tolstoy, Fedor Dostoevsky, Maksim Gorky, and Chinghiz Aitmatov) and children’s literature. Copyists worked side-by-side with editors. They also learned the language on the job. Later, after a year or two, they were given proof-reading tasks which largely required careful attention to detail and an excellent memory. My last transcriber’s job was copying Rallanhandi’s (who preferred to be called RVR) translation of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina into Telugu in 1990. This manuscript has never been published in Russia.

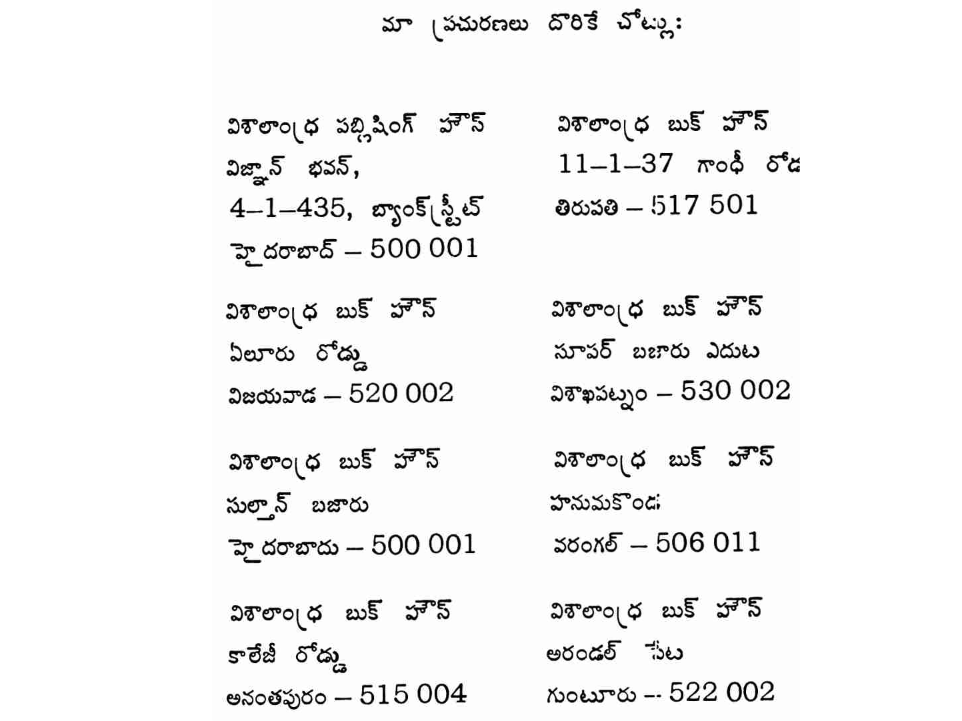

Our daily translation teamwork also included the maintenance of our own Russian/English/Telugu terminology lists through numerous visits to the publishing house library and consultation of encyclopaedias. Today, this work has been transferred from a paper format, such as card catalogue or filing-cabinet records, to CAT tools, building special terminology dictionaries in machine-translation programmes. Our translation work in Moscow continued beyond the confines of Progress and Raduga. From 1969, the year in which Dzenit made her first business trip to India, we had regular contact and co-operation with Visalaandhra Publishing House. As our regional partner in India and our educator too, they sent us books in Telugu and their own newspaper, Visalaandhra, which provided good opportunities for us to read about events happening in Andhra. We also used their pool of staff members (or their recommendations) in order to select translators to invite to work with us in Moscow. Every book we translated contained a list of Visalaandhra branches where readers could purchase or order our other books. According to this list, written in Telugu, there were at least eight outlets: two offices in Hyderabad, and one office each in Vijayawada, Visakhapatnam, Warangal, Guntur, Tirupati, and Anantapur:12

Fig. 2. Contact details for all eight book outlets of Visalaandhra Publishing House in Ukrainian Folk Tales.13

In order to maintain correspondence with our readers and to obtain their opinions on our work, we also encouraged them to contact us in writing by using our official postal address. We used the Progress address during the first couple of years of the establishment of Raduga, then moved to our own premises, a building located behind the Stalin skyscraper of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at 43 Sivtsev Vrazhek Lane. Our address was written in English; we received correspondence from readers in both English and Telugu. Answering questions or addressing requests expressed in these letters was part of everyone’s workload. Sometimes, the head of the Telugu section would share reader feedback (including requests for specific books to be translated) with the head of the Department for Literature in Translation into Indian Languages. These discussions could result in plans to print more copies or prepare other editions of a particular publication.

Translation as Global Cultural Initiative

Before perestroika, only the heads of the Telugu sections could travel to India and visit our business partners there. After 1985, it became possible for other members of staff to go. These trips became more focused on expanding our horizons and studies of Telugu, in addition to maintaining our business contacts with Visalaandhra Publishing House. For example, I studied Telugu at the University of Madras from 1987–88. My visit to India was sponsored by the Soviet government: in addition to my studies, I actively participated in the Soviet-Indian friendship festival in 1987–88, organised under the joint initiative of Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi. Among my official engagements were the following activities: delivering a speech titled ‘The Importance of the October 1917 Revolution on the Development of Telugu Literature’ in Telugu at the CPI’s Congress in Vidjayawada; taking part in awards ceremonies organised by the journal Soviet Land and the regional branch of TASS (The Telegraph [News] Agency of the USSR); and working at the Soviet bookfair in Madras; and travelling freely, with the support of Vadim Cherepov, the Consul General of the USSR in Madras between 1979 and 1990, within the Southern state of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. My experiences in Southern India enriched my knowledge of Indian culture and encouraged me to continue translating.

Concluding Remarks

I agree with Munday that “lived experience” has subjective elements, but I also hope that my own experience provides new perspectives on literary translation and its process. Out of the four advantages listed by Munday to applying a quantitative macro-social history approach,14 my microhistory clearly illustrates the last one, i.e. that “it links the individual case study with the general socio-historical context”. Moreover, it provides evidence on translation as a collaborative activity in which the importance of team spirit and cultural enthusiasm rather than censorship and ideology is emphasised.

The impact of our translation work commissioned by Progress and Raduga on Telugu readers is difficult to overestimate. Today, when there is no literary tie between post-Soviet Russia and India on the level of state-sponsored publications, there remains great interest in our books among contemporary reading audiences in India. Young readers find them in the libraries of their parents and grandparents and use the platform of social media to read and discuss them. Divya Sreedharan (2021)15 and Sai Priya Kodidala (2020)16 provide several examples of various online sites, blogs and Facebook pages dedicated to the popularisation of this type of literature. Sreedharan also states:

The Soviet literary heritage continues to exist in India. Many Indians who had been thrilled to read Soviet magazines and books some time ago, after becoming adults maintained their passion for the books of their childhood and even started to collect them.17

It seems that the process of creating world literature in translation, Gorky’s famous initiative, continues in the twenty-first century.

1 Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (London and New York: Routledge, 1995).

2 Jeremy Munday, ‘Using Primary Sources to Produce a Microhistory of Translation and Translators: Theoretical and Methodological Concerns’, Translator Studies in Intercultural Communication, 20:1 (2014), 64–80, https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/84279/1/Munday%20microhistory%202014.pdf.

3 Gengshen Hu, Eco-Translatology: Towards an Eco-paradigm of Translation Studies (Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020).

4 Izdatel’stvo Progress: 50 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1981).

5 CIA, The Soviets in India: Moscow’s Major Penetration Program: An Intelligence Assessment (1985), https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP86T00586R000400490007-7.pdf.

6 Ibid., p. 16.

7 Ibid., p. 15.

8 Ibid., p. 4.

9 These so-called “Russian Telugu girls” will be more fully discussed later in my article.

10 Svetlana Dzenit and Anna Ponomareva, The History of Telugu Section: Progress Publishing House, Moscow, USSR (Vijayawada: Visalaandhra Publishing House, 2012). Telugu version: ద్జెనిత్, స్వెత్లానా & అన్నా పొనోమరోవా, ప్రగతి ప్రత్సురణలయం, మాస్కో, యు. ఎస్. ఎస్. ఆర్. తెలుగు విభాగపు మాజీ అద్ఖిపతి (2012). The dictionaries cited above are: Albert Henry Arden, A Progressive Grammar of the Telugu Language with Copious Examples and Exercises (Madras: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1905) and Paluri Sankaranarayana, An English-Telugu Dictionary, 4th edn (Madras: P.K. Row Bros, 1900).

11 Svetlana Dzenit and Nidamarti Uma Radzheshvara Rao, Russian-Telugu Dictionary (Russko-telugu slovar’) (Moscow: Russkii iazyk, 1988).

12 The addresses of the branches of Visalaandhra Publishing House can be found in the following publication: Ukrainian Folk Tales (Moscow: Raduga Publishers, 1988); in Telugu, ఉక్రేనియన్ జానపద గాథలూ, p. 249, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B07Gk0_NnBKiWWlYNElveVJXbWs/edit?resourcekey=0-NBTK-VwncQVhnD2VgkwR5Q.

13 Ukrainian Folk Tales, p. 247.

14 Munday, ‘Using Primary Sources’, pp. 5 and 12.

15 Divya Sreedharan, ‘How Soviet Books Became Iconic in India’ (‘Kak sovetskie knigi stali kul’tovymi v Indii’) (2021), https://russkiymir.ru/publications/287073/.

16 Sai Priya Kodidala, ‘From Moscow to Vijayawada: How Generations of Telugu Readers Grew up on Soviet Children’s Literature’, Firstpost, 14 September 2020, https://www.firstpost.com/art-and-culture/from-moscow-to-vijayawada-how-generations-of-telugu-readers-grew-up-on-soviet-childrens-literature-8809591.html.

17 Sreedharan, ‘How Soviet Children’s Books Became Collectors’ Items in India’. AP’s translation.