10. Fallen Jewish Vilna

Translation ©2023 Brym & Jany, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0341.10

Vilna is now a dead city. For a newcomer, the streets immediately make a frightful impression. In truth, the sidewalks are a little fixed up and the houses are somewhat washed and cleaned. However, the people in the streets look more dejected, fallen, and neglected than they did three years ago. There is no city in Poland where people are so poorly dressed. People’s clothes are so worn that poverty seems universal. Poverty is a resident, a secure owner in the city, and is not of two minds about leaving here. People in Vilna have come to accept this situation. Privation stretches out broadly, dominating every aspect of life. There are no hopes, no prospects, so one must make peace with destitution.

In no other city of Poland does one see as many closed and bolted stores as in Vilna. On Strashun Street I counted 16 such stores out of 42. On the street of the Vilna Gaon,1 one of every four or five stores is closed—similarly on Daytsher, Zavalner Street, and Troker Street.

True, I was in Vilna at the end of January, in the month when one must renew {business} licenses. It is possible that many storekeepers will eventually receive enough money from America or a credit fund to renew their licenses. But in itself, the fact that one is forced to close up shop for a month or two demonstrates how profoundly destitute the population is. In the merchants’ union they gave me to understand that this January 352 stores and 60 workshops were closed because their owners could not afford license renewals. How many will eventually be able to reopen and how many will abandon their boarded-up doors and seek new livelihoods one cannot yet know. The closed stores make an impression similar to the scene immediately following a pogrom, when not everyone has returned to the city and not all inheritors have opened up the stores of their murdered parents.

The Jewish population, which is tormented by the tax collector and ruined by antisemitism, certainly feels as if it has endured a pogrom, a tax pogrom that has gone on for years and for which one sees no end. I first felt the tragedy of the tax- and antisemitism-pogrom when I began to enter stores that were open for business.

Many residents of Vilna certainly remember Zalkind’s large store. It existed for more than a century, surviving good times and bad, times of expansion and crisis. But then the business arrived at the period of antisemitism and tax pressure after Poland became independent.

Before the war, up to 150 people worked in Zalkind’s business—clerks, bookkeepers, and ordinary workers. It was a large clothing and haberdashery business with its own workshop with 50 tailors. The business occupied a large three-story building and always seemed lively, fresh, growing, and successful.

When I entered the store, I was astonished. Deep in the store it was dim. The top floors were dark. For a distance of several steps after the entrance, the store was illuminated. A man with a bandaged head was wandering around. His eyes jutted out prominently. They peered into the distant darkness and then wondered at the stranger entering the store and disturbing the grave-like stillness. Two other men stood by the checkout. They leaned against the wall—quiet, frozen, as if condemned. Two young women stood by the shelves. They were startled when I entered, not used to being disturbed.

The three men were the owners. The two young women were the last of the many clerks. They were the last flickering candles that will probably be snuffed out because the store must close down. The word “catastrophe” is too weak for the situation I encountered in the store, where to be served one used to have to wait for a long time until one of the clerks was free.

I grew depressed from the darkness, emptiness, stillness, and the quiet steps of the owner with the bandaged head, who moved around like a shadow, a symbol of life extinguished. I spent a long time in the store and had a long discussion with the owners about the factors that ruined such a sound and reliable business. Here they are:

The war was already a resounding blow because the population became impoverished. Vilna was near the front and was often cut off from the world. Afterwards inflation arrived. Merchandise became scarce and paper billions mushroomed. When the value of the currency, the zloty, was established {in 1924}, one received little merchandise of little worth. These were certainly big blows that weakened the business’s capital. But all these setbacks did not ruin the business. It was laid waste by factors of an entirely different character.

Zalkind’s business depended mainly on consumers comprised largely of Russian officers and officials from tens of state institutions. They made purchases without money, on instalment, and bought in the same store for decades. All of these customers are now gone. Polish officers and officials buy from Jews only when they lack an alternative. However, such cases are fewer every day. Polish-owned stores are opening, taking the place of the Jewish-owned stores.

In no city is the competition from new Polish storeowners felt more keenly than in Vilna. A good Polish haberdashery was established just in the last few years, and it diverted revenue that formerly went to Zalkind. A new Polish textile store was also established. It siphoned off the best Polish customers of dry goods. A new Polish business specializing in pharmaceuticals was also established, and the respected pharmaceutical business of the Jewish Segal brothers is wavering and shrinking from day to day. The Segal brothers are well-known Zionists. One of them now lives in the land of Israel, where he has many gardens and where his son tragically died in the last pogrom in Palestine. Before the war, Segal’s business in Vilna had up to 100 employees. Now it has fewer than ten.

The Polish storekeeper is often victorious against his Jewish counterpart because the Polish state is on his side. Here is an example: The Railway Directorate sent its officials a circular in which it recommended that they buy from Polish storekeepers. The circular does not say they should boycott Jewish storekeepers, but the Polish official easily surmises what is meant and is gladly ready to carry out the good deed of pushing Jews out.

Similarly, Bank Polski, the state bank, is in pure Polish hands, so a Polish storekeeper receives more credit more frequently and easily than does his Jewish counterpart. The kind of credit policy followed by the Polish state bank becomes clear from the fact that in 1929 it issued credit totalling 103 million zloty in Lodz and 312 million zloty in Posen. One does not need to study Polish economic life thoroughly to know that Posen does not have even one-quarter of the industry of Lodz. Lodz is second only to Warsaw in the amount of tax on gross sales that it contributes to state coffers; Posen is in fifth place. Why then does Posen receive three time more credit than Lodz does? Perhaps Lodz is so rich that it does not need so much credit? It emerges that even the world-famous Poznanski textile factory {in Lodz} discounted promissory notes on the stock exchange at more than 20%. Once can therefore imagine what kind of need exists in Lodz for credit. One must therefore look for another explanation, and it is not hard to find. In Lodz all factory owners with very few exceptions are Jews and Germans, not Poles. And in Posen there are few Jews—even few Germans remain there.

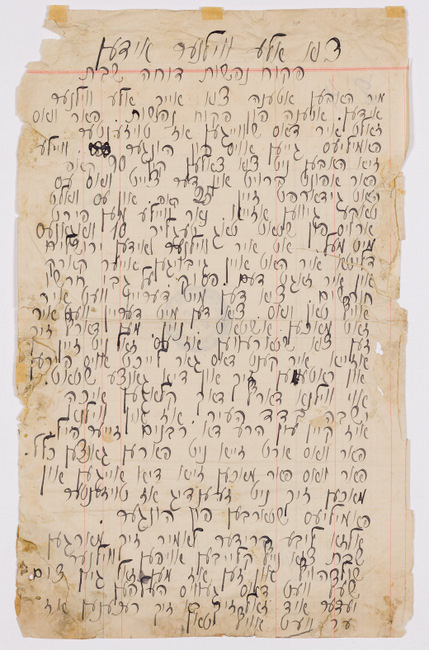

Fig. 7 Untitled handwritten appeal (1923?), Vilna, Poland. ©Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York. The appeal states: “To all Vilna Jews: saving souls is more important than keeping the Sabbath. We have a grievance against all Vilna Jews. The grievance concerns saving souls. Why should you be silent when thousands of Jewish families are starving?” The appeal singles out rabbis for ignoring the plight of families dying of hunger and calls on Jews to gather in a synagogue courtyard the next day, on the Sabbath, to address the issue. The appeal refers to a 360% increase in the price of a funt (0.41 kg) of bread, suggesting that it may have been written during the hyperinflation of 1923, http://polishjews.yivoarchives.org/archive/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=21092

Let us return to Vilna. One can see an example of how the Jewish artisan suffers from antisemitism from the following fact: Before the war, there were 300–350 Jewish painters in Vilna. They worked mainly on the railway line, state secondary schools, and also private buildings. The state was the largest construction enterprise. Today, Jews are not hired to do state work. Even city hall seldom gives Jews a little work. Accordingly, there are now in Vilna just 40 Jewish painters and 30 apprentices. Before the war, Christian painters were just one-fifth or one-sixth as numerous as Jewish painters. Today, there are ten times more Christian than Jewish painters. Before the war there was one Jewish contractor who had 80 Jewish workers. Now there are almost no Jewish entrepreneurs in this field. All Jewish painters are individuals who work with one apprentice.

Almost the same thing happened with carpenters. Before the war, there were 300–350 Jews in this trade. There were three big factories that employed more than 200 workers. Now there remain only 50–60 Jewish workers distributed over many small workshops. Meanwhile, the number of Christian carpenters has increased considerably. The only explanation is that private individuals build little and seldom. Only the state and the city build much, and they do not employ Jews.

The province of Vilna was always rich with forests. As everywhere in Poland, the lumber trade lies completely in Jewish hands. In the city of Vilna alone there are even now about 200 large and small lumber merchants with about 400 employees. All without exception are Jews. In the entire Vilna area about 1,000 Jews, owners and employees, earn a living from the lumber trade. Including their families, they number about 4,000 people because they are mainly Jews with large families. Around these 4,000 Jews are another 1,000 or so Jews working as dealers and artisans.

Recently an edict was issued to stop selling state-owned forests. The Jews greeted it like a thunderbolt but for Christian forest workers the situation is now better. The state will surely pay no worse than Jewish private entrepreneurs. However, laws concerning the length of the workday and insurance will be better respected. In place of 500–600 Jewish employees there will probably be no fewer than 1,000 Christians. Therefore it is not just the Jewish bourgeoisie that pays the price of nationalization but also Jewish workers.

To form a picture of the tax collectors as real murderers, it is enough to hear out just a few Vilna Jews about the taxes that are torn from the population. They are actually the main force driving Jews to suicide. It has progressed to the point that in Vilna a Christian storekeeper by the name of Dukovski committed suicide and left a letter to the Finance Department saying that he is departing the world because he can no longer afford to pay taxes. This one and only Christian suicide (compared to the tens of Jewish suicides) caused such an uproar that the entire Polish press reported it. As long as only Jewish merchants and storekeepers were throwing themselves from the upper stories and splitting open their heads, all Polish newspapers kept quiet.

One must understand that, in general, tax fees are much lighter for the Christian than the Jewish merchants and storekeepers. When I was in Poland, barely a day passed where in one place or another a Jew did not commit suicide because of taxes. In Lemberg, a mother of six children hanged herself after tax collectors removed the last bit of merchandise from her store. Interestingly, even a Polish National-Democrat, who according to his program must be an antisemite, broke down in tears at Warsaw City Hall when a Bundist read a document outlining how they took the last sack of potatoes from a Jewish family in lieu of taxes.

A Lodz merchant who travelled with me from Lodz to Warsaw told me the following characteristic story: He owns a textile store in Lodz. In the last two years he paid 1% of his gross income in tax because he is a wholesaler. Soon a new tax inspector came and decided that he is not a wholesaler but a retailer and must therefore pay 2.5% of his gross income. He was ready to pay the amount due when the inspector declared that he must also pay additional percentage points and fines for the last two years, amounting to exactly twice as much as the previous total.2 The merchant was hurrying off to Warsaw to ask the minister not to ruin him and turn him into a poor man. But there was faint hope that he would be heard and that it would be decided that the problem was the tax inspector, not the merchant. Such cases number in the hundreds and thousands. It is enough to say that in the last few years tax officials collected 200 million zloty more than was designated—all blood drawn from Jewish storekeepers, often small ones.

When the previously mentioned Christian storekeeper in Vilna committed suicide, nearly all stores in the city were closed for the funeral, which was attended by a huge crowd. In this manner they at least protested against the inhuman actions of the tax officials. But when a Jew jumps from the fifth story because the tax officials took everything from him, he is buried quietly somewhere behind a fence. His relatives are too ashamed to say that their father or uncle departed the world because of tax murderers. A few years ago, the rabbis even issued an appeal not to {religiously} honour a person who commits suicide because suicides have no life in the hereafter.

If one wants to see how Vilna is going under it is enough to sit for half an hour in the office of the gmiles khsodim {benevolent society} fund or the emigration office. Lending 50 or 100 zloty without interest to be repaid in small sums is the aim of the gmiles khsodim, which the “Joint” supports in hundreds of Jewish towns and which is now the most popular and loved institution everywhere (see fn. 1, p. 60). The fund was created for the weakest and poorest parts of the Jewish population in Poland. Among the latter, five or ten dollars is a significant amount of “capital” that cannot be obtained elsewhere. Their entire existence depends on such amounts.

The gmiles khsodim fund in Vilna does a very good job of rescuing the small storekeepers that have 50 zloty worth of merchandise, the women who sell fruit or chickens, the cobblers, and ordinary poor artisans. However, while it is designated for the poorest people, those who in normal times would be embarrassed to visit its office also seek assistance from the fund. I sat there and saw one man requesting a loan of 100 zloty ($11) because he could not afford to renew his business license and without the renewal he would have had to close his store. Artisans arrive who just a couple years ago employed two or three workers and enjoyed a good income. Teachers, salaried employees, workers, and, in truth, members of all classes enter. And if until last year everyone paid up when a loan repayment was due—because they knew for certain that they would get the hundred or fifty zloty again as soon as they settled up—now the situation is much worse. There are twice as many overdue and unredeemed promissory notes as those that are paid off by the due date.

In the waiting room of the emigration office I met a large crowd. Almost all the people were youthful, between 25 and 30 years old, men and women. I asked a young man of about 25 if he has anyone in Brazil, where he wanted to go. His answer was curt: “I am traveling to God. I have nobody there, but here I have nothing.” This was the mood of everyone in the waiting room—they were eager to move to the ends of the earth just to stop fading out and going under in Vilna, where people had given up hope and ceased to believe in better times. Vilna’s Jews migrate to remote parts of the world, to South America, Central America, Africa, and Australia to anywhere ships and trains go. Vilna’s Jews have beat a path to places where Jews have never been.

The Jews of Vilna do not lack energy and courage. Here before me stands a young woman, who looks about 19 years old although actually she will be 21 in a few months. Her father is in New York and he wants to bring her over. The American consul requires clear proof that she is not older than 21 but she has only a certificate from her shtetl’s rabbi. And in two months she will lose her right to go to her father in New York. A more desperate face is difficult to imagine. The young woman was really trembling and barely holding in her tears. And she was not the only such case.

I was told also in Warsaw, Lemberg, and Bialystok that the American consul torments the unlucky prospective emigrants who by law have the right to be admitted first into the quota. Among all these young people who lack official documents testifying that they are younger than 21, the consul intentionally introduces difficulties so that the term permitting entry into the United States will expire. In the Warsaw office I saw a young man who was two weeks away from losing his right of entry. In the space of two weeks it was impossible for him to prepare as many documents as the consul demanded. The young man argued, begged, and made plans but the manager of the office had to explain plainly that his running to lawyers would be a waste of money and effort. One felt that this was the end of the young man’s one and only hope, the loss of his years-long dream and therefore of everything, of the one opportunity to make something of his life. It had been five years since he completed his schooling, and during that period he had waited and looked forward to the moment when his turn would come and he would escape to his father in New York. I am sure that the young man did not receive a visa. I am not sure that he is still alive. His face was too desperate, his spirit too dejected.

In Vilna, all classes are dejected and impoverished. Understandably, there are still some rich people. However, they are so insignificantly small in number that one does not feel their presence in the city. And they, too, are sinking. In all cities there are plenty of Jews who have gone downhill but in Vilna there remains no sign of once rich people. In Warsaw, Lodz, Krakow, Lemberg—everywhere in cafes and restaurants I saw many Jews, many richly dressed Jewish women. But in Vilna one finds no Jews in the better restaurants. I purposely went to the few restaurants where at night there is music and dancing. I found no Jews there. In general, one sees only officials and officers in restaurants. In contrast, even in this difficult time, the most expensive cafes and restaurants in Warsaw are packed, mostly with Jews.

Why has Vilna suffered more than other cities? Warsaw, Lodz, Radom, Bialystok, and other cities lost a lot when the Russian market for their merchandise was no longer available. However, while the other cities gained markets in Posen, Upper Silesia, and Galicia, compensating to a great extent for the loss of the Russian market, Vilna lost everything.3 It is situated far from the new Polish markets and so cannot compete with other cities that are situated closer to them. Apart from chamois and glove makers, who sell large amounts of merchandise in Posen, no other article that used to be made in Vilna found a place in the new Polish markets. The sock industry, which used to employ thousands of people, is completely dead. Ready-to-wear clothing production is nearly dead. Tanneries are on their death bed. And so it is in all branches of trade and industry. Vilna lost not only the Russian market, where it used to send ready-to-wear clothing, shoes, socks, and leather, but also nearby markets. The Kovno, Minsk, and Vitebsk governorates used to be major consumers of Vilna’s products. Now they are torn away and cut off from Vilna.

Walled off by borders from all areas with which Vilna traded for centuries, and in particular from the Russian market, for which Vilna was producing more and more in the decades before the war, Vilna is also now far from the rich Polish market. It is wedged in a narrow corner, exhausted by the war, suffocating from antisemitism, drained by taxes. Once rich Jewish Vilna lies sick and weak, beaten and fallen, without hope for better and brighter times.

1 {Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, the Vilna Gaon (genius), was a leading eighteenth-century Talmudist and proponent of misnagdic (anti-Hasidic) Jewry.}

2 {These percentages seem small but it is unclear how often they were collected and how small the merchant’s margins were.}

3 {The new markets became available after World War I, when Poland gained new territories along with independence. The Russian market was lost during Poland’s 1919–21 war with Russia.}