3. The heritage of the Jewish factory owner

Translation ©2023 Brym & Jany, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0341.03

It is not only Jewish and non-Jewish workers in Poland who come from two completely different social, cultural and status groups. The same holds for owners of enterprises.

In Germany and great Russia, upstart tradesmen and rich traders played a major role in the development of industry. In Poland, these elements played an insignificant role, at least as far as the non-Jews among them were concerned. Until the eve of the war, most Christian entrepreneurs in Poland were landowners or former landowners, senior state office holders or their sons, engineers and jurists—almost all members of the upper classes. They were brought up for many generations in an atmosphere in which they dominated the masses and remained estranged from them. A chasm existed between them and the lower classes. Only rarely was a non-Jewish entrepreneur a former peasant, worker, tradesman or merchant who sprang from the lowest to the highest classes. And if Poles could be found among German weavers in the textile industry, then they were rare exceptions in all other branches of industry.

The origins of the first generation of Jewish factory owners were utterly different. A very small number of them came from the Jewish haute bourgeoisie with inherited wealth—bankers, landowners and major merchants. For the most part they came from the same classes that gave birth to the Jewish worker or from adjacent and related classes. There was no cultural chasm, no psychological wall, between the first generation of Jewish factory owners and Jewish workers, as there was between their Christian counterparts. The resulting psychological and cultural proximity and near equality between owners and workers caused the owners to see the workers as competitive threats. This circumstance was perhaps one of the most important factors leading them in due course to reject Jewish workers. Fear of the ambition of Jewish labourers and office workers, who quickly grasped the essence of the business, was not unfounded; we will soon see what a large percentage of Jewish factory owners were formerly office workers or master craft workers in factories.

We analysed biographical materials on more than 100 large and middling Jewish textile manufacturers from Lodz and Bialystok.1 An interesting picture emerged. Their emergence from classes very close to those from which Jewish workers were recruited stands out surprisingly sharply.

In connection with their cultural environment it is enough to say that 95% of the first generation of Jewish textile manufacturers studied in cheder. More than three-quarters ended their education with at least some yeshiva. One-third of the large textile manufacturers studied in yeshiva. None had any higher secular education. Only eight of 50 large manufacturers attended a secular school, although only a primary school and not a high school. Ten of the 50 received their secular education from private teachers.

Let us now see from what sort of population centres the entrepreneurs came, how they were employed before they became manufacturers and how their parents were employed. Of the 93 large and middling textile manufacturers whose place of birth is known, 74.2% were born in small towns, 8.6% in small cities and 17.2% in large cities.2 Regarding their former occupations, it is revealing to divide them into two groups, as follows:

Table 5 Former occupations of large and middling Jewish entrepreneurs, percent in parentheses

|

Former occupations |

||

|

26 (49.1) |

19 (47.5) |

|

|

8 (15.1) |

2 (5.0) |

|

|

Rabbis, rabbis in training |

5 (9.6) |

0 (0.0) |

|

2 (3.8) |

16 (40.0) |

|

|

Manufacturers |

12 (22.4) |

3 (7.5) |

|

Total |

53 (100.0) |

40 (100.0) |

The first group consists mainly of office workers, children of small-town businessmen who set out in the world to seek their fortune because there was nothing for them to do in their small towns and their inheritance was too small to be of much help. With gritted teeth and bitter hearts, they first worked for others. They were downwardly mobile or the children of the downwardly mobile, but they had a tremendous amount of energy, agility and stubborn will not to remain employees. They wanted to become independent and they made up nearly one-half of the first generation of middling and large textile factory owners. Of course, these former office workers, brokers and travelling salesmen did not constitute even 1% of all the Jews engaged in these occupations. Thousands dreamt and strived but only a few succeeded—the most talented, the most persistent, often also the most miserly and money-hungry. These entrepreneurs, who had themselves experienced working for someone else as salaried workers and made their way to the highest social rung, yet were so close to the masses, became and remained the biggest opponents of Jewish factory labour. That is understandable. They knew full well how close the Jewish worker often stood to the factory owner not only regarding understanding the technical side but also the whole complicated commercial substance of the enterprise.

There were very few former master craft workers among the early large textile factory owners—just 3.8% of the total—but among middling textile factory owners they constituted fully 40.0% of the total. Together with former office workers, brokers and travelling salesmen, they comprised 87.5% of the middling factory owners. Only 5 (12.5%) were former merchants, storekeepers or men who started out as factory owners right away. In contrast, among the large textile factory owners, the distribution of former occupations is completely different. Nearly 10% had been rabbis or rabbis-in-training. Few had been master craft workers in factories, but 22.4% were factory owners from the outset, starting the enterprise with their own capital. Former merchants and storekeepers, who probably also had some capital, constituted just over 15% of the group.

Unfortunately, we have information on the parents’ occupations of only 41 large textile factory owners. The parents of 25 of them (61.0%) had been merchants or storekeepers, 6 (14.6%) had been landowners or bankers, 5 (12.2%) had been manufacturers3 and 5 (12.2%) had been rabbis or teachers of religion. Only the two middle categories, comprising a little more than one-quarter of the total, can be counted as members of the Jewish haute bourgeoisie. The remaining nearly three-quarters were either middling owners or “small people with small aspirations.”4 There is no doubt that the middling Jewish textile factory owners originated in the common people much more often.

To add flesh and blood to the data just cited, we will recount a few short biographies of Jewish pioneers in the textile industry:

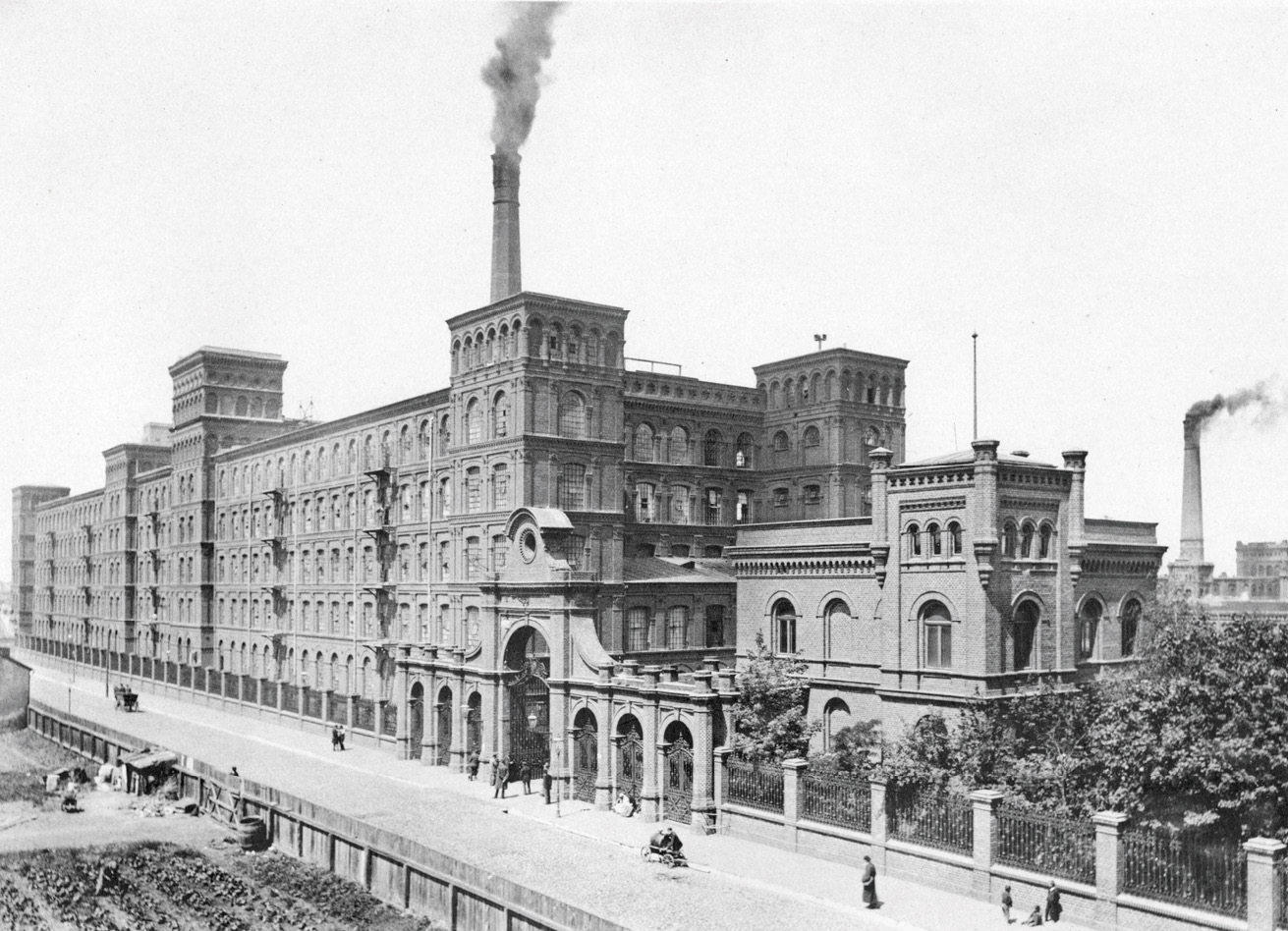

- “Israel Poznanski was born in 1883 in Alexander, near Lodz. His father, Kalman Poznanski, was an honest merchant. Israel married the daughter of Moyshe Herts, who was secretary of the Warsaw Jewish Community. Immediately after the wedding, Israel started a small business in Lodz’s old city.”5 We leave aside the whole story of how this small storekeeper built up his own gigantic factory structures, palaces and houses, mentioning only that, although the business started sharply declining during the war, the Poznanski factories still employed 4,297 workers in 1929.6 It is important to add that the success of the owners of this firm occurred during the life of the old Poznanski, who came from a simple but respectable home. During his life, the success of the business was much greater than after his death, when his children took over. They were educated and had completely different ambitions and appetites. They assimilated, and some of them converted.

- “Asher Cohen was born in Lodz in 1870. His father raised him, like all his children, at the bosom of the Torah. He hired the best rabbis and instructors to tutor the young Asher, who was blessed with a good head for the gemora and was also a diligent student. His father took great pride in his son who, he believed, was set to become a child prodigy. At sixteen-and-a-half, he was married, becoming the son-in-law of Zalmen Rubin in Tomashev {about 60 km. southeast of Lodz}, an important broker.”7 Omitting the story of how Asher became a maskil,8 learned weaving, founded a firm in partnership with others and became director of a large factory, what is important for us is that 8,500 people now work in Asher Cohen’s factories.9 The one-time student of the Talmud who was on the verge of becoming a child prodigy and then became a maskil is now the boss of a whole village of factories and houses with its own railroad and a colossal network of textile enterprises.

- “Markus Zilbershteyn began his career as the rabbi of the first Jewish industrial pioneers. Later, after he received a little secular education, he became a bookkeeper for the German firm, Kindler, in Pabianice {about 15 km. southwest of Lodz}.”10 In 1929, some 1,152 workers were employed in Zilbershteyn’s factory.11

- “Y. Rosenblat was born in Lodz. His father, who was from the shtetl Przedbórz {about 125 km northeast of Katowice} and was a rich chasid, owned real estate in the environs of Lodz and some houses in Lodz. The younger Rosenblat had a religious upbringing but tore himself away from the house of prayer and gemora at a young age. When he was 18, he began manufacturing.” Rosenblat’s factories employed 2,551 workers in 1929.

- “The Eitingons received a Jewish bourgeois education. They first studied in cheder and then in the Orsha municipal school. Naum and Boris, who moved to Lodz, proceeded though all the phases that Lodz residents usually went through. Naum worked in Tzemekh’s kerchief factory, starting at the lowest level, and rose higher on life’s ladder until he left the firm and founded a kerchief factory in partnership with his cousin, Mikhoel Eitingon, from Moscow. Boris Eitingon, arriving in Lodz, for a short time worked in his relative’s business, but he soon got a post in the distinguished firm of Shtiler and Byelshovski. Thus, both Naum and Boris were at first employees— and now 1,028 workers are employed in the Eitingon and Co. factories.

Fig. 3 Bronisław Wilkoszewski, Fabryka Tow. Ak. Poznańskiego [The Poznanski textile factory] (1896), Lodz, Poland. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronis%C5%82aw_Wilkoszewski_%E2%80%93_Fabryka_Tow._Ak._Pozna%C5%84skiego.jpg

Until now we have considered the biographies of large owners in Lodz’s Jewish textile industry. Now let us turn to a few biographies of owners who employ 300–400 workers each:

- “Yerakhmiel Lipshitz was born in Ozorkow {about 30 km. north of Lodz}. His grandfather was the rabbi of Ozorkow, and his impressive lineage extended all the way back to the rabbi of Kotzk {the spiritual founder of the Ger chasidic dynasty}. His father was a well-to-do glass merchant. At the age of 16, the young Lipshitz moved in with his relative in Lodz, Fayvl Shulzinger, and there graduated from his first “classes” in the “academy of trade.” Now Lipshitz owns an enterprise that has all the technical means to produce textiles from raw materials to finished products, including Raschel machines {for making lace}, knitting machines, circular knitting machines, his own weaving shop for making kerchiefs, and his own finishing machines.”

- Solomonovitsh was born in Petrikov {about 200 km west of Katowice}. He worked for a few years as a secretary in the wood industry. He married in Tomaszów. His father-in-law was the well-known Tomaszów broker and wood merchant.12

- Poretski and Govenski own one of the largest textile enterprises in Bialystok. Poretzky was born in Shtutshin and Govenski in Vasilishki, both in the province of Vilna. Soon after each of them were married, they started trading in wood. While they both founded their company, Poretzky’s son was mainly responsible for its development. He arrived in Bialystok in 1896 from a yeshiva and became the driving force of the enterprise. Their factory became well known because it was the site of one of the most difficult struggles of Jewish workers for the right to become machine weavers; they were the first to be victorious in this regard, winning the right to occupy one-half of the factory’s machine-weaving positions.

- A. and Y. Pikelni came from Novogrodek {about 200 km east of Bialystok}. Their father, a well-known scholar, owned a liquor factory. He was a follower of the Enlightenment and raised his sons accordingly. Avrom Pikelni was the first of the children to leave the town to seek his fortune, and because the family had a relative in Lodz, and Lodz was considered “Little America,” he moved there and took a position in the German firm, Josef Richter. A. and Y. Pikelni is now a mechanized weaving company in Zdunska Wola {about 50 km. southwest of Lodz} with 112 looms and a business in Lodz.

- Avrom Moyshe Prusak from the small town of Drobnin in Plotsk province was born in 1820 to a merchant family. He arrived in Lodz a young man and immediately took to trade and manufacturing. He was a religious, chasidic Jew who regularly sought advice from his rebbe and would do nothing without the rebbe’s approval. Prusak was among the very first pioneers of mechanized weaving in Lodz. At the time, factory owners and machine weavers were almost all Germans. When Prusak introduced weaving machines, he hired Jewish weavers and taught them machine weaving. This caused an uproar among the German machine weavers. Under the leadership of Julius Heinzel, who was then still a weaver but later became a great industrialist and was given the title of baron, they marched to the Jewish quarter to destroy the Jewish factories. However, the mayor found out about it in time and dispatched Cossacks, who dispersed the German weavers and drove them off.

- Herman Foyst was born in Czestochowa {about 125 km. northwest of Krakow}. At the age of 13 he set out to make a living for himself. He was employed in the office of the Jewish factory owner, Levitski, in Pabianice. He then took a position in the office of the largest factory in Pabianice, owned by the Baruch brothers. A few years after he married, he became a factory owner himself and he is now one of the richest entrepreneurs in Pabianice.

- Sh. H. Tsitron, born in Mikhalovo near Bialystok, was a grandson of the well-known Bodker rabbi and head of the Rozan yeshiva. His father had a dry goods store in Mikhalovo. Tsitron studied in yeshivas and arrived in Bialystok at the age of 17, where he started trading in cloth. Later he became a factory owner, and is now one of the biggest entrepreneurs in Bialystok.

- Yankev Kahan is known as the “the King of Socks” in Poland. Born in Berezovka near Odessa, where his father had a dry goods store, the young Kahan studied with the best tutors and was considered a genius. At 12 he became an orphan, and at 13 he went to Odessa where he became a sales clerk in a small manufacturing shop. Later he founded a brokerage office in Odessa and then moved to Lodz, where he became a travelling salesman. He then founded a sock factory and became the first person in Lodz to introduce sock manufacturing by machine. He is now one of the biggest sock manufacturers in Lodz. In his younger years Kahan wrote in Kol mevaser, Folksblat, and Spektor’s Hoyz-fraynd.

- Y. Sheps was born in Tomashev and as a child was considered a prodigy. As a youngster he became a rabbi in Tomashev and at the age of 15 he was already issuing rulings on religious questions. However, he made a living not as a rabbi but in the wool trade, and from there he transitioned to manufacturing.

- Volf Alt was born in Kovel {about 160 km. east of Lublin}. He arrived in Lodz as a child and completed school there. At the age of 15 he began work at Herman Kahan’s factory, where he became a master craft worker. Now independent, he employs 80 workers.

- The Teytelboym brothers were born in Gabin {about 100 km west of Warsaw}. They worked in Voydislavski’s factory as master craft workers. Already before the war they had their own factory where they employed 300 workers. Now they employ up to 100 workers.

What do we learn from these biographies? We learn first that all Jewish entrepreneurs began without capital, either inherited or substantial capital of their own making. All of them worked their way up thanks to their intelligence, energy, animated nature and entrepreneurial agility. Almost all Jewish entrepreneurs began putting out goods to be manufactured in people’s homes and then, after accumulating a little capital, they founded factories. The origins of nearly all of them were in the Jewish middle class; they came from comfortable homes, but from homes that were downwardly mobile. About half the factory owners went through a stage of working for someone else, for the most part as office workers and sales clerks getting a taste of dependent work, and then they made a transition from poor young Jewish men to major capitalists. Culturally, and almost without exception, they studied in cheder and had a traditional Jewish upbringing; they studied gemora and many went to yeshiva. Most of them received a secular education only when they were grown up, already engaged in life’s struggles, often from private tutors, and also not infrequently from self-education.

This is the profile of the first generation of textile factory owners. Clearly, the second generation has a completely different character, having opened a social and cultural gap between themselves and Jewish workers, who, to a considerable extent, are until today recruited from the same strata as the first generation of textile factory owners. However, an even larger proportion of the Jewish working class comes from ruined members of the petite bourgeoisie and from the poor masses in general, who live off fortuitous employment and earnings.

The condition of Bialystok industry after the war illustrates the enormous effect of the psychology deriving from these social origins on the development of the new occupations into which Jews have moved. In Bialystok, ownership of the textile industry is now completely in Jewish hands aside from one plush factory belonging to a German. Before the war there were 10 German factory owners and more than 100 Jewish factory owners, including owners who put out goods to be manufactured in people’s homes. In 1912, of 66 weaving factories (apart from those where weavers worked with customers’ materials), 58 were owned by Jews.13

The largest factories were in German hands. The 10 German factories employed about one-third of all textile workers in Bialystok, housed about 25–30% of all looms and were responsible for 40–45% of all textile production. After the war, Bialystok’s textile industry experienced considerable shrinkage. On the eve of the war there were 1,500 looms in operation and now there are only 1,000. Production has fallen by 50%. There were 4,675 textile workers in Bialystok in 1895; on the eve of the war about 10,000; in 1920, 5,133; and in 1928, 3,975.14 Bialystok thus employs fewer workers today than it did more than 30 years ago.

Why did all the German textile enterprises go under while the Jewish ones remained? This is a most interesting chapter of economic history that demonstrates the great importance of the psychology of various entrepreneurial groups—their entrepreneurial spirit, their stubborn adaptability, their capacity to outlast others and drag themselves through to better times.

Right after the war, the Bialystok textile industry revived a little. The Polish government, which led a war against the Bolsheviks, placed large orders. Later the economic crisis began. With Russia locked shut, it was first necessary to take advantage of the internal Polish market as much as possible, especially the newly integrated areas of Congress Poland. Second, it was necessary to seek new markets wherever possible—in the Far East, China, Japan, the Balkans and Hungary. So long as inflation lasted, and Polish goods were very inexpensive, the German textile factories in Poland continued to produce. But when stabilization occurred, Polish goods were insufficiently competitive. Capital became meagre and there was nowhere to borrow from. However, Jewish factory owners proved themselves wonderfully adaptable.

They sent agents to the farthest points in Asia. Because Russia was closed, they had to travel three months to reach China and the Far East. Goods took 5–6 months to arrive. It took 9–10 months before payment arrived. Some of the large Jewish factory owners themselves went on these long journeys to Asia, struggling to find a market for their goods. For example, blankets from Bialystok became one of the most widespread articles in China and to some degree also in Japan. To a considerable extent they out-competed English goods. After a long struggle in the Balkan countries, Bialystok’s Jewish factory owners also captured a significant market share, especially in Romania and Yugoslavia.

It was not easy for them to fund these ventures, but here too they proved themselves adaptable pioneers whom the German factory owners could not match. They started paying workers with six-month or even eight-month promissory notes. The workers had to sell them on the stock exchange. Bills for wagons of goods sent to faraway places were sold to banks, often to the Hamburger Volksbank but not infrequently also to local “percenters” who had multiplied in number throughout Poland. Finally, they simply borrowed money; the Jewish factory owner was not ashamed to borrow small sums from tens of people to put together the capital he needed. Interest-free loans from Jewish charitable organizations as well as loans from Jewish savings and loan associations also helped the Jewish middle and small factory owners.

The scattering of Jews to the ends of the Earth to find new buyers and adapt to the new market, the shipping of entire lots of material and receiving payment only 9–10 months later—this pure Jewish twisting, grabbing, covering, borrowing, patching and always being in a market of payments and obligations without knowing how many hundreds of promissory notes one had signed and when their terms expired (even promissory notes for 20 or 30 zloty)—all this without a strict bookkeeping system because one must, after all, economize on administrative expenses—this entire raucous mode of manufacturing was so alien to the German manufacturers that the Germans were forced to completely liquidate their enterprises. In this manner, inherited Jewish agility and adaptability in a moment of hardship became especially important factors in preserving existing positions and capturing new ones.

1 Based on Lazar Kahan’s Ilustrirter yorbukh far industri, handl un finansn, Lodz, 1925.

2 Eight in Lodz, four in Warsaw, three in Bialystok, one in Odessa.

3 Three textile manufacturers, one soap manufacturer, one manufacturer of spirits.

4 {The quotation is from Sholem Aleichem’s portrayal of shtetl life in his classic series of that title.}

5 Kahan, 52.

6 Rosset, Lodz miasto pracy, Lodz, 1929, 43.

7 Kahan, 64.

8 {A follower of the liberal Jewish Enlightenment.}

9 Rosset, 44.

10 Kahan, 38.

11 Rossett, 43.

12 These and later biographical details about factory owners are from L. Kahan’s book.

13 A. Ziskind, “Fun Byalistoker arbeter-lebn,” Fragn fun lebn, No. 2–3, 1912.

14 “Di antshteyung, antviklung un matzev fun der byalistoker tekstil-industri,” Yoyvl-zhurnal fun prof. fareyn fun tekstil-maysters in byalistok, March 1929, 30, 31.