1. The pogroms in Poland, 1935–37

Translation © 2024 Brym & Jany, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0342.01

Comparative pogromology

Pogroms in each country and era have a unique character and scope, because every pogrom wave has its own driving force, agents, ideologues, perpetrators, and organizers, its own economic basis, political atmosphere, and social environment.

Tsarist pogroms were to a great extent directly organized and executed by state organs.13 Their socio-ideological environment was the insignificant and uninfluential Black Hundreds,14 an organization that was sustained by the financial support of the tsarist government. Their political support was from a thin stratum of reactionary monarchist intellectuals. The large, intellectually rich, and influential Russian intelligentsia—from journalists for small provincial newspapers to great men of letters and painters—opposed tsarism, the pogroms, and the entire anti-Jewish policy. Their struggle against tsarism was consequently transformed into a struggle against antisemitism.

The class basis of the tsarist pogroms was very narrow. It consisted of the so-called meshchantsvo—urban Christian storekeepers and artisans, the only social groups negatively affected by Jewish competition and capitalist agility, although they feared these talents much more than they suffered from them. All other classes were so caught up with the economic upswing of capitalist Russia and so enchanted with the struggle to loosen social and national restraints, opening wide doors for young and vigorous Russian capitalism, that, with rare exceptions, there could be no question of students, intellectuals, and the better part of the bourgeoisie participating in pogroms.15 The Russian bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia—the most important political forces in the country—benefited from blessed Jewish agility because the Jews were the most talented and nimble elements distributing manufactured goods from Moscow and Russian cultural treasures over the length and breadth of the country. They suffered least from Jewish competition because Jews were largely confined to the Pale of Settlement.

The tsarist pogroms were bloody and cruel because they were carried out by mercenary secret agents, ex-police officers, incentivized members of the underworld, and even soldiers in the painfully infamous Bialystok pogrom of 1906 in which as many as 100 Jews were killed, many of them women, children, and the elderly.

The goal of the tsarist pogroms was decidedly political—to drown Bolshevism, which had so quickly captured the hearts of the Ukrainian masses, in Jewish blood; to scare away the Jewish masses from participating in the revolutionary movement; and to divert the rage of the dissatisfied masses from the political regime to the Jewish scapegoat.

The Petliura and Denikin pogroms (1918–1921) were utterly different.16 In the red-hot atmosphere of war and revolution; in the complicated skein of ethnic and social contradictions that uniquely characterized Ukraine, entangled and deepened by the hunger that the Russian and German armies left as their legacy; in the incandescent atmosphere of the social and ethnic struggles, it was inevitable that the disorganized Ukrainian army regiments and organized adventurist bands would awaken the traditions of the Haidamaks, the slaughter tradition of Khmelnitsky’s and Honta’s Cossacks.17 The Ukrainian pogroms were therefore transformed into terrifying mass slaughters with tens of thousands murdered and wounded and hundreds of thousands fleeing their homes.

The goal here was also expressly political—to drown Bolshevism, which had quickly and strongly captured the hearts of the Ukrainian masses, in Jewish blood; discourage the awakened and excited Jewish masses from participating in the political struggle; create a chasm between Jewish and Ukrainian workers; and deflect attention from the class struggle, which the Bolsheviks stressed, to the ethnic struggle.

If the central organizer of the tsarist pogroms was the police department, then it was the general staff in the Petliura pogroms. If in the tsarist pogroms it was necessary to organize pro-pogrom sentiment in every place, then in the time of war and revolution it was enough merely to show the way and pro-pogrom sentiment overwhelmed the entire land like a plague. If in the tsarist pogroms it was enough to kill any Jew to foment panic among all Jews and hold their political activities in check, then in the revolutionary fire of 1918–19 it was necessary to murder young Jewish men, the pogromists’ actual or potential political opponents. In the Petliura pogroms, the percent of murdered Jewish men between the ages of twenty and forty-five was therefore shockingly high. There were also slaughters of entire cities and towns where not only elderly people, women, and children were exterminated, but even the sick who were dragged out of hospitals. However, the organizers and ideologues of the Petliura pogroms, the masters of Petliura’s general staff, aimed for Jewish youth.

The class basis of the Petliura pogroms was broad, although conditioned by the war and the times. There existed a deep contradiction between the Ukrainian countryside and the towns where Jews lived. The peasants brought grain, eggs, milk, butter, and other products to town but could not sell them for enough money to buy the salt, rolling tobacco, kerosene, matches, and material for clothes that they needed. Jewish storekeepers, who carried all these items in minimal quantities, followed the tradition common to all storekeepers throughout the world and among all peoples; they insisted on extracting the highest prices possible. The gap between the price of agricultural products and manufactured goods was enormous. Therefore, in the previously described heated atmosphere it was not at all difficult to make the small-town Jewish storekeeper with an inventory worth all of ten roubles that he hoped to sell for a 10% or 20% profit—this small screw in the complicated machine of the war-and-revolution economy—seem responsible for all the war troubles, the mobilizations, requisitions, “contributions,” and plain robberies conducted by regular and irregular armies that sprang up like mushrooms after rain and swept the country like locusts. The hungry, war-weary, exasperated Ukrainian peasant eagerly adopted the slogan: release your bitterness on the Jews, the historical scapegoat.

Unique features characterized the Denikin pogroms even though they occurred mainly in the same heated Ukrainian atmosphere. With Great Russian White officers lacking their own national environment and masses—occupiers in essence, threatened from two sides, by the Bolsheviks and the Ukrainians—the Denikin army had to live by robbery.18 Hatred and contempt toward Jews combined with a special sympathetic weakness for Jewish women were inherited characteristics in this aristocratic-officer environment. Anger against Jews as the most formidable enemies of tsarism was also transmitted from generation to generation. It is therefore no surprise that Jews became the most suitable object for the Denikin pogroms, the main features of which were plunder and rape.

For the sake of their honour, it was also much more acceptable for aristocratic officers to place blame for the decline on the weak Jews rather than confess their own responsibility for the social and political reactionaryism that so frightened off the masses, especially the peasants who had barely managed to reclaim land from the nobility.

In both the Petliura and Denikin cases a vicious cycle was created: the more frequent and murderous the pogroms became, the stronger and larger became the flow of Jewish youth to the Red Army; and the more Jewish sympathies for the Reds grew, the crueller and bloodier the pogroms became. Frightened to death by the rivers of Jewish blood that began to flood tens of Jewish towns, and scared enough to flee to the far corners of the world with every movement of the Petliura or Denikin army group, the Jewish masses, especially the youth, driven by basic instincts, had one way out: to join the Red Army, receive weapons, and thus hope to save women and children from death by pogrom and fall on the battlefield rather than die in an attic or a cellar.

Class-conscious organized Jewish workers, urban and schooled in Marxism, remained anti-Bolshevik much longer than did non-Jewish workers, who had among them many peasant anarchist rebels. The Jewish population in general, more than half of which consisted of bourgeois elements, suffered much more from Bolshevik requisitions and “contributions” than did the non-Jewish population, among which bourgeois elements amounted to just a few percent. And yet opponents of the Bolsheviks and children of bourgeois Jews who were impoverished by the Bolsheviks ran to the Red Army because they were willing to give all, really everything down to the shirt off their back, to anyone who would undertake the mission of stopping the murderer, tearing the knife from his hand or cutting off the hand entirely. For physical rescue they were willing to sacrifice not only material goods and economic resources, not only social principles and achievements, but also political worldviews and ideological differences.

The Red Army undertook the mission of physical rescue, and one must be objective and admit that it often conducted this mission heroically, which far surpassed the general hatred of a common enemy. Understandably, this further inflamed the passion of Petliura’s and Denikin’s soldiers; the greater their defeats on the battlefield, the more blood they spilled in the helpless unarmed cities and towns. And it is also understandable that the more that innocent Jewish blood was spilled, the more the Jewish masses ran to the Red Army.

In the pogrom waves of contemporary Poland, the central driving force is direct economic competition. The agents and directors of the attacks and excesses are those who are directly interested in getting rid of Jewish competition—those who want to take over the Jewish place in the market or the job in the store, the candidates for the position of the Jewish doctor or lawyer, the children of the broad Polish classes of various social origins who are ready and waiting for vacated Jewish occupations.

The political aspect, the blaming of Jews for Communism, for being enemies of Polish independence, for striving to turn Poland into a Jewish-Polish state—all these are side issues, additional factors secondary to the main point, the economic struggle, that has taken the form of pogroms, murders, knife attacks, and beatings with wooden sticks visited on those who earlier had a job in trade or medicine. In the Russian and Ukrainian pogroms, the organizers were in a police department or an army general staff, but here in Poland they are in a party headquarters that relies on a large mass of people from various classes, on aristocrats and priests, on the urban bourgeoisie and the majority of the intelligentsia, on petit bourgeois storekeepers and craftspeople, and on the large number of today’s typical déclassé individuals from various social classes. And let us also say openly that in that party there are also not a few workers, although the overwhelming majority, the more politically conscious and active majority of the Polish working class, is organized in the socialist party, which fights energetically against the pogroms and antisemitism.

In Russia and Ukraine, participants in the pogroms were agents of the police who discarded their uniforms, anarchic soldiers and bands, desperate officers who in the revolution lost their army and their inherited aristocratic wealth. In Poland, the participants consisted of a large number of the unemployed or those who had not yet joined the paid labour force, from a student to a janitor’s son, from an Orthodox priest’s daughter to a chimney sweep, from a former landowner’s son to a landless peasant, from an unemployed musician to a tailor’s journeyman, from an apprentice lawyer to a street merchant, from a hungry artisan working from home to a sated official who lacks access to jobs for his growing children and believes in securing places for them by driving the Jews out of Poland.

Therefore, in Russia and Ukraine, there were bloody pogroms, mass slaughters, but here in Poland there are sporadic murders, excesses, attacks, knifings, beatings with sticks, and bombs placed in Jewish businesses; there, organized, politically connected, and therefore time-limited incidents with the goal of creating political panic or political isolation, political demagogy or simply political deception; but here in Poland separate, disconnected, widely distributed ambushes and attacks that have an entirely different aim—to remove, chase, force out, compel abandonment of a store, a market job, a workshop, a hospital, or a lawyer’s practice. One senses in these ambushes and attacks an organized central force—but a party force that can provide slogans, advice, and means but not police or army forces that can initiate and halt incidents when and how they want.

The class base (or, to put it more crudely, primitively, and therefore accurately, the intestinal base) is here shockingly broad: millions of hungry peasants who have nothing to do in the countryside and who rush like a natural force into the city and urban occupations; small shopkeepers, artisans, and homeworkers; large parts of the bankrupted nobility; ruined formerly well-to-do peasants; urban bourgeois elements suffering from the economic crisis; impoverished intellectuals; and finally, the entire younger generation from all classes and strata, which sees before it no bright prospects in poor Poland, which is pressed between two large economic and political forces—Germany and Russia—and has no room for economic expansion and no hope of political expansion. This broad class basis of antisemitism explains the social atmosphere in which Polish Jewry lives, an atmosphere in which one is suffocated.

Crisis and hunger; overpopulation in the countryside; weak development of industry that cannot absorb the large natural increase of 450,000 people per year; low agricultural prices on the world market; the fall of exports; the decline of emigration, which used to remove 150,000 people a year from the country; and the waning of seasonal labour migration, which used to bring millions of zloty into the country annually—all these factors create rich ground for antisemitic agitation and demagogic antisemitic slogans. However, one cannot solve all these serious and complicated economic issues with holes in the skulls of Jewish students and wounds in the breasts of Jewish storekeepers. On the contrary, antisemitic actions further disorganize economic life, which is already minimally organized. They increasingly anarchize certain parts of the population. The panic disturbs the already weak willingness to invest on the part of large sections of the population.

To understand the entire knotted ball of factors that influence Poland’s bloodthirsty antisemitism positively and negatively one must consider that the Endek party19 is the oldest, largest, and strongest antisemitic party in Poland. Although with respect to antisemitism it has brought together enthusiasts and members from all classes and strata, it has not been able to win broad support among the peasantry and working class. It thus remains chiefly a party of the nobility and priests, industrialists and storekeepers, officials and intellectuals. As strongly as this crafty Jesuitical party wants to unite the aristocracy with the peasantry and the industrialists with the workers through antisemitism, it did not and probably will not succeed. This party therefore has broad socio-political influence but a small social base.

In contrast, the socialist movement, the only organized force that opposes antisemitism in all its forms, has a broad social base—peasants and workers—but a very small political base. That is because the press, the theatre, radio, and all other organs that influence the population, as well as existing political grandstanders, are in the hands of dominant classes that are in Poland without exception antisemitic. Some are for pogroms, others for so-called “cultural” antisemitism, that is, for economic and social antisemitism without bombs and knives. However, practice has already shown that the classes that carry out the antisemitic program, when they write that Jews are the enemies of Poland, that they are harmful to the population, that one must get rid of them as soon as possible and, as long as they are in the country, one must isolate them as much as possible and push them as much as possible into the ghetto, arrive at the only logical conclusion: one must do everything up to and including staging pogroms so Jews will take flight, the faster the better.

One cannot blame the Polish government for organizing pogroms against Jews. However, one can and must blame it for preparing the ground for pogroms: tolerating the propagandizing that inevitably leads to pogroms; allowing to go unpunished the small attacks and casual excesses that whet the appetite of hooligans and that get transformed into mass attacks and killings; and finally, only weakly punishing knifings and murders. In the bitter struggle between right and left, the right throws all its might into concentrating the dissatisfaction of the masses on ethnic antagonism, with the government pouring water on the millstone of this wildly antisemitic right wing. It turns out to be a strange imbroglio. The government, attacked by the Endek party, helps the latter strengthen its position.

In reality, this situation has more to do with political competition. The governing party, Sanacja,20 wants to tear the popular antisemitic slogan out of the hands of the Endek party and use it for its own party interests. However, it lost the competition because, firstly, it was a little late to the game and, secondly, overtaking the Endek party in pogrom agitation and pogrom tactics is in practice exceedingly difficulty. The outcome is fatal. The government isolates the Jews politically, starves them economically, and ghettoizes them culturally, while the Endek party supplements this “state” policy with beatings and killings of Jews, breaking the windows of Jewish houses and throwing bombs into Jewish businesses, driving Jews out of the marketplaces and placing boycott agitators in front of Jewish businesses, setting Jewish homes on fire, and dousing Jewish merchandise with oil. Violent hatred and venomous agitation accompany these actions. If the masses believed one-tenth of the accusations and defamations hurled against the Jews, they would have exterminated all of them long ago.

Let us now turn to the factual part of our work, which will clearly show how tolerant the Polish government is toward the bloodiest antisemitic provocations and pogroms.

The countryside

First, a few words about the material we will use in our work. Unfortunately, it consists only of newspaper articles that have gone through the highly stringent Polish censor, so the articles are like official acknowledgements. In the editorial archives of all Jewish newspapers there are mountains of material that could not be made public due to censorship. This does not mean that the archives do not reflect reality. Quite the opposite. There can be no doubt they were not allowed to be made public because they reflect actual life too clearly. However, we have not used these archival materials.

We begin with the murdered. We have a list with the names of hundreds of murdered people in tens of places. From this alone it is already clear that we are dealing not with bloody mass pogroms but with individual attacks and murders that characterize Polish excesses—economic competition with knives and wooden sticks up to the point of murder. Only in Grodno, Pshitik, and Minsk-Mazovyetsk were there real pogroms with the music of breaking glass, feathers flying like snow, human sacrifices, and many wounded in each city.

Let us briefly consider a few terrifyingly characteristic murders. In May 1935, in Duksht {Dūkštas}, Vilna district, a Jewish family—a husband, wife, and children by the name of Feldman—is just about ready to migrate to the land of Israel. They travel to relatives in the neighbouring little town of Vidzi {Vidžiai} to take their leave. They are happy, they are leaving the diaspora, they are going home; the family members have been active Zionists for years. The family is in full harmony; they are in seventh heaven. Friday evening young Yankev Feldman goes for a walk with his relatives on the streets of Vidzi. Suddenly two Christians with whom they are unfamiliar run over to them and deliver blows to the young Feldman’s head with pieces of iron and stab his sides with knives. If the hooligans had known this young Jew was willingly about to leave Poland they would certainly have killed someone else because their aim is really not so much to murder as to decrease the number of Jews in Poland.

Here is a murder in the village of Leopoldov in the environs of Shedlets {Siedlce} in June 1935: Goldman, a sixty-two-year-old Jew from Riki {Ryki}, a country merchant, passes by the house of a peasant, Jaras. This peasant’s son, a local Endek activist, exits the house with an axe. With its sharp side he splits open the Jew’s head. He does not quite kill him because the Jew is destined to writhe in pain for several hours. The Jew dies the next morning in his town while all its Jews cry and lament for Goldman and for the destiny of the entire Jewish community, which finds itself in the line of concentrated Endek fire, accompanied by blood, fear, concerns about tomorrow, and worries about making a living today.

The Jewish community in Minsk-Mazovyetsk was shaken by the murder of Yisroel Tsirlich, a young Jewish man of twenty-odd years, a well-known and beloved local Po’ale Tsiyon {Labour Zionist} activist and leader of the party in his city. He came from the train station the Thursday night before the first of May 1936. Suddenly a group of hooligans befell him. They knifed him in the lung and the kidney, having earlier that evening wounded several other Jews on that same road. They left him lying in a pool of blood and ran off. Losing blood, the wounded man barely dragged himself to a Jewish home, but the residents were too frightened by the cries in the street to open the door. He died in the street. Several other Jews were severely wounded that day. Early the next day the hooligans tried to continue their attacks, but they clashed with organized resistance. Two of them were seriously wounded. Several of them were jailed along with the Jewish porter, Yitskhok Ostshega, who was blamed for knifing one of the hooligans.

In the village of Verniki {Zwiernik?} near Pilzne {Pilzno} in Western Galicia lived a Jewish family that owned a store. There was also a non-Jewish storekeeper in the village. In January 1936 the Jewish storekeeper was attacked in an attempted robbery. An eighty-year-old man by the name of Khanine Garlitser and his son were shot and lightly wounded, but this time the attack was repelled. The family remained in the village, living in fear because their enemy, the competitor, threatened and promised revenge. The murderers waited for an evening when both young sons were not in the village and the eighty-year-old remained alone with his daughter. On 20 March 1936 they broke into the store, delivered a blow to the daughter’s head with an iron, killing her instantly. Then they broke into the house. The old man was sitting and studying the gemora.21 He hadn’t even heard the death-throes of his daughter. They didn’t have to struggle long with the old man. One blow of the iron killed him, spraying the gemora with blood.

The murder of Jewish landowner Markus Nelken in the village of Rataye {Rataje}, not far from the town of Pizdri {Pyzdry}, was especially shocking. The prelude to the murder involved a Jewish manager who worked for the landowner. The manager’s son-in-law, Mordkhe Bararbis, had a small shop in the village, where, in 1935, an Endek organization was formed. From then on, the Jewish storekeeper didn’t have a quiet day. In the beginning the Endeks advised him to leave the village but he did not. However, when they started repeatedly breaking the store’s windows, he understood the sign of the times and fled.

The antisemitic organization kept on growing. The population was incited. In the village there was frequent discussion of putting an end to the zhids.22 The main role in the organization was played by one Sobolevski and, even more, his wife. Sobolevski worked for a Jew, Nelken, but he spoke not of his Jewish boss but of the zhid. A celebration of the patriotic organization’s new flag took place, and Sobolevski’s wife gave a provocative talk in the church. On 9 March 1936 Sobolevski went to Nelken with an axe under his coat. He delivered two blows to Nelken’s head, killing him instantly. The police apprehended Sobolevski only two days later. Bound in chains, he mockingly remarked that he got rid of only one zhid.

The extent of the tragedy of Polish Jewry, which becomes more insecure in its physical existence day by day; which feels more and more like it is in an environment that is losing the most elementary human feelings in relation to the Jews; which chokes on its last bit of bread because it knows well that this last bit of bread is the main reason for all the hatred and enormous misfortune—the fathomless depth of the tragedy of a landless people, of a tenant people, appears in the murder of three members of the Florents family in the village of Vala-Kurashava {Wola Kuraszowa}.

A poor Jew with a wife and several children lived there. He was the only storekeeper in the village. In 1935 a revolution took place in the village. Marian Mamchik, the son of a peasant, more educated than his father, a reader of antisemitic newspapers, lacking opportunities for work or a job, opened a little shop. And Marian Mamchik declared with words and with stones, with angry stares and with wooden sticks, that he must remain the only storekeeper in the village because there is no room for two.

The indictment states: “Seven days prior to the murder, on 23 December 1935, Marian Mamchik, the owner of a store in Vala-Kurashava, promised the accused, Kazimierz Marei and Jan Fenatshna, several bottles of liquor for breaking the windows of the store of the Jew, Florents.” Here is what happened according to the trial report: “On the night of 30 December a group of nine young peasants headed by the two accused entered the shop of Hirsh Florents and sang traditional Christmas carols. The Jew politely received them, and after the songs were finished offered them cigarettes and candies. Nor was he stingy with money. The group left, and the Florents family went calmly to sleep, not sensing that the misfortune they were about to experience approached with every passing minute.

Around midnight they heard an urgent banging on the door. Hirsh Florents got up first and asked, “Who’s there?” However, before he managed to hear the answer the doors to the vestibule were thrown open. Florents then bolted the inner doors behind him. Then, the attackers, with indescribable wildness, ripped off the shutters and the windows and tore into the house. The screams of the attacked were heart-rending. Hirsh Florents managed to flee through a side window to call for help, but none of the peasant neighbours wanted to move until he finally convinced one of them. The help was too late. When they arrived at the house they saw by the pale light of a night lamp Miriam Florents lying on the floor with no sign of life. Near the dead mother, four of her children were lying in a pool of blood.

Fourteen-year-old orphaned Zaynvl survived the ordeal with a broken hand and testified at trial: “After they broke and destroyed everything in the house they ran over to mommy with an axe. She begged for mercy and promised to leave the village. We, the children, were hiding under the bed. However, the murderers dragged us out one by one and hit each one on the head and on the body with a board, then covered our heads with buckets.”

The widower and father ended his testimony thusly: “When no help came, I ran back home and found a picture of destruction and murder. My wife was lying there with a cut up face and no sign of life. Ten-year-old Moyshele was lying there with his brain split and a cut up body. His mouth was open, as if he let out a shriek before he died. Beside them, twelve-year-old Malkele lay beaten—she was such a dear child. Only fourteen-year-old Zaynvl and six-year-old Yisroel showed signs of life. I then began running with my last strength to the nearest town and only in the morning returned with a doctor. And that morning I finally left the village.”

He left, but a little too late. The lively Jew was late this time and thus paid dearly. At trial Florents said that he was already thinking about leaving the village, but the competitors had no patience. At trial they claimed that they believed that in Poland it was permissible to kill Jews and drive them out. One murderer was sentenced to twelve years in prison and the second to six years. However, the jail sentences will not bring the dead back to life, and six-year-old Yisroel, who remained in a prolonged state of shock, will not recover emotionally. The place was “sanitized,” and the newly minted Polish storekeeper can celebrate his victory.

Here is a murder typical of those in the Ukrainian villages: on 15 August 1936, in the village of Tulishkov {Tuliszków}, they broke into the home of Diamand, a farmer, decapitating and cutting up the bodies of the entire family of four souls, then setting the house on fire. The neighbours noticed the fire, put it out, and found the mutilated bodies.

And here is another case that clearly illustrates the situation of the Jews in the countryside: in the village of Tsigane, eastern Galicia, lived a Jewish widow, Roze Kon. She was born in the village and lived there for many years. It is not known when her ancestors settled there but it is possible that they arrived a century or even two centuries ago. The widow had a small food shop and there she toiled. Her old mother and a nine-year-old daughter lived with her.

The local antisemites began tormenting the widow. Pickets outside her store didn’t allow Christian customers to enter. There were actually days when they had no income. In the end, antisemites broke in at night and murdered the woman. A local well-known antisemite was arrested and evidence existed that he participated in the murder. The sorrow and despair of the two who remained alive—the old woman and the young daughter—cannot be described.

In the village of Khnidav, eastern Galicia, they murdered the Jew, Yosef Meser, and his wife, Gitl. Both were more than seventy years old and had lived their entire lives in the village. They murdered them with an axe while they were in their beds and then set fire to the beds. In all these cases, nothing was stolen, an indication that the murder was not a result of robbery but was an “ideational,” “patriotic” murder.

A Jew was standing in his house in the village of Nove-Myasto {Nowe Miasto} saying his evening prayers. Suddenly a shot rang out. He died on the spot. Who shot him? Why? Nobody was apprehended. We therefore don’t know who shot him. However, we know why he was shot. He was a Jew, and that answers all questions.

Frequently one reads in Yiddish newspapers such notices: “On the road near Slonim two dead Jews were found. They used to travel between villages” (Haynt, 9 May, 1937). In the period of interest here we counted eight murdered Jews whose names could not be determined. Here is a brief notice typical for murders in Ukrainian villages: “Sunday, 28 March 1937, in the village of Kotlov {Kotłów}, the horrifying murder of Moyshe Kugler and his wife was carried out. After stabbing him with knives, the bandits slit his throat and shot his wife three times. The deceased left three orphans between the ages of eight and fourteen. It is believed that the perpetrators were Ukrainian nationalist terrorists” (Dos naye vort, Warsaw, 31 March 1937). And here is another interesting notice: “This evening (5 January 1937), in the village of Maike, Dalhin county, eastern Galicia, three masked bandits entered the apartment of Dovid Klinger and stabbed him and his wife, Gitl, to death with stilettoes. Nothing in the house was disturbed” (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 7 January 1937).

The declaration a murderer gave in a Lemberg {Lvov; Lviv} court is characteristic of the mood that has emerged in the population. He killed the Fridman couple from Yanov {Janów}, and during the trial said the following: “In the military they taught me that the Bolsheviks are the biggest enemies of the Polish state. Because all Jews are Bolsheviks, I believed I did well by killing a couple. Hitler would have awarded me a distinction” (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 10 April 1937).

The fatal influence of antisemitic provocation on the population—especially on the rural population, which is much more naïve and often takes the words of a newspaper as a sort of command or recommendation from the regime—was expressed even more clearly during the trial. Consider also the trial of a young peasant from the village of Leshno {Leszno}, near Kozhenits {Kozienice}, who lured two village merchants, Leyb Flamenboym, aged seventy, and Meylekh Goldvaser, aged forty-two, with the proposal to sell them hides, and killed them with a hammer. He was arrested the same day at his friend’s wedding. He was led away from the dancing, chained, and jailed. At trial he openly, calmly, and cold-bloodedly declared that he killed the two Jews because he read in the newspapers that the Jews must be driven out of Poland. The prosecutor demanded the death penalty. Frightened by the prosecutor’s speech, the murderer, in his last words, appealed to the judges for clemency because he didn’t kill actual people, just Jews (Haynt, Warsaw, 16 November 1936).

The following case perfectly expresses the atmosphere in which Poland’s village Jew lives. The large ten-member Miler family lived in the village of Zhidlovyetz. On the night of 8 June 1937 their house was set on fire. Awakened, the family jumped out of their beds to try and save themselves. However, the doors were securely bolted from the outside by boards. The Millers barely managed to escape, although two family members were badly burned. One of the two, Meylekh Miler, aged thirty, died the same day of his wounds. The newspaper correspondent wrote the following: “Though the Jew got along well with his neighbours—peasants—nobody wanted to give him a ride to the hospital because they feared revenge” (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 14 June 1937).

The murder of Monish Poznanski from Kviv {Klwów} shows how far the cruelty of the hooligans can reach and how wild the entire population becomes in the pogrom atmosphere. The surviving eight- and thirteen-year-old grandchildren painted a picture of inhumanity that curdles the blood in one’s veins.

During a pogrom in Kviv, Jews fled to Pshitik. Children, women, the elderly, the ill, baskets with a few items, featherbeds—all thrown together in wagons, and they flee to blessed Pshitik, which already survived the inevitable pogrom edict. On the way, they threw the Jews out of the wagons and beat them. We let the children tell the rest: “Our grandfather was lying on the ground. There was a large black spot near his temple. We carried him, his arms around us. He didn’t speak, and his eyes were bloodshot. We took him to Vozhniak, the school teacher, but Vozhniak locked his door and didn’t let us in. We continued over the entire village but nobody wanted to help. They didn’t even give us a little water. Our grandfather became weaker and weaker, and he was wobbling. When we arrived at another village, Vzhesub {Wrzeszczów} it was already evening. I took two zloty out of grandfather’s wallet to hire a wagon to Pshitik. We said to one of the peasants: ‘Help us bring our grandfather to Pshitik. He will pay you well. He is a good man.’ It didn’t help. We had to return to the village of Potvorub {Potworów}, where we went to the village magistrate. Grandfather fell down and started to moan. The magistrate got a wagon and brought us to Pshitik” (Moment, Warsaw, 20 July 1937). When they brought the sixty-four-year-old Poznanski to the hospital in Radom, the doctor determined that his eyes had been gouged and his skull fractured. That night, Poznanski died without regaining consciousness.

We will end this chapter of rural hell with the frightful murder of five Jewish souls in the village of Stavi {Stawy}, Kelts district. Here is how the correspondent of a Warsaw newspaper described the murder, which terrified the entire area and filled all the country Jews of the region with indescribable dread (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 20 October 1937): “Moyshe Shmulevitsh had for many years lived in the village of Stavi and had a little shop there. Recently Shmulevitsh had received threats demanding that he leave the village. At about 11:30 on the tragic Thursday night of 15 October 1936, someone knocked on his door. Shmulevitsh, thinking it was a customer, opened the door. Several men entered and immediately began shooting. The first victim to fall was Moyshe Shmulevitsh, then his thirty-five-year-old wife, Sore Rokhl, and his seventy-three-year-old mother. They cut out the tongue of the grandmother. Hearing the shooting, a twenty-three-year-old cousin, Mirl Koyfman, who was their house guest, ran in. She was immediately shot. Then the teacher, Moyshe Kenigshteyn, was murdered. Only the two children who hid themselves survived: twelve-year-old Yankl and sixteen-year-old Feygele.”

To clarify the depth of the tragedy of the rural Jewish population, it is enough to briefly quote from the speech of the attorney for the main defendant in the murder trial, the young peasant, Józef Zhepyetski. Lawyer Tshikhovski exclaimed: “Here is the young Christian village merchant, who yearns for trade. The whole country regards him and such as him with delight; he and such as him should be freed. He is a young productive type and there are many like him in Poland.”

All the accused were freed, but in a few months it turned out that this young peasant, whom “the whole country regards with delight,” was the murderer not only of the Jewish family but of his friend in crime, whom he began to suspect would betray him.

The cities

The murders described earlier have an avowed economic character. Almost all murders in the countryside must be considered as such. Urban murders have an entirely different character. In the former case Jews are typically murdered by an acquaintance, often a neighbour with whom they had good or bad relations for many years, but in all cases, relations under which lay certain economic interests. The situation is completely different in the latter case. In cities, Jews are attacked and murdered by strangers whom they had never seen before and with whom they had absolutely no prior relations. They are murdered simply because they are Jews, only because they belong to a certain ethnic group. The fatal influence of antisemitic provocation is easily determined in both rural and urban murders, but in the urban murders, members of antisemitic parties are the main perpetrators, often with the direct influence of a party meeting. The direct influence of wild but permitted antisemitic agitation emerges in its naked form in the urban murders. These murders are political, not in the sense that the attackers have political accounts to settle with those who were attacked, but in the sense that members of certain parties include murdering Jews in their program. However, not all urban murders have a political character; the impression is created among many urban Poles that one can resolve the problem of Jewish competition with an axe or a revolver.

Here are a couple of examples. On one and the same street in Vilna, Savitsh Street, there lived two shoemakers: a Jew, Simkhe Magid, and a Christian, Franciszek Nikolayev. The former worked in a little shoe factory and the latter had an open workshop. They were of course not well-to-do; the factory worker was doubtless poorer than the owner of his own workshop. The Jew lost his job when the little factory closed. He was weeks without income. They eat up everything they have left, pawn their last few pillows, and then he, his wife, and their five-year-old son go hungry. Magid decides to open a workshop, like thousands of the unemployed do everywhere. He borrows and scrapes together a few tens of zloty and opens a workshop facing the street. The Christian doesn’t think long. He takes a hammer, tears into Magid’s workshop, and delivers several blows to his head. This is not the place to describe the suffering of the poor shoemaker, who lost his ability to speak, then his eyesight, and died two days later (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 14 August 1937).

Here is a second case, deriving not from the competitive struggle but simply from the lawlessness that exists when one buys from a Jew. In the town of Stanin, Lukov {Łuków} county, there was a fair, where a Jewish hat maker worked. A peasant went to him for a hat. He tried on hats until one appealed to him. He put the hat on his head and walked away. The Jews ran after him and asked to be paid, and the peasant paid him right there by hitting him on the head with a wooden peg. The Jew fell in a puddle of blood and died before being brought to the hospital (Folkstsaytung, Warsaw, 20 June 1937).

Let us turn now to political murders, not in the sense that members of various political orientations struggle against one another and their struggles reach the point of reciprocal murder, but in the sense that, in this case, every Jew, old or young, devout or not, conservative or radical, is regarded as an enemy who deserves the death penalty.

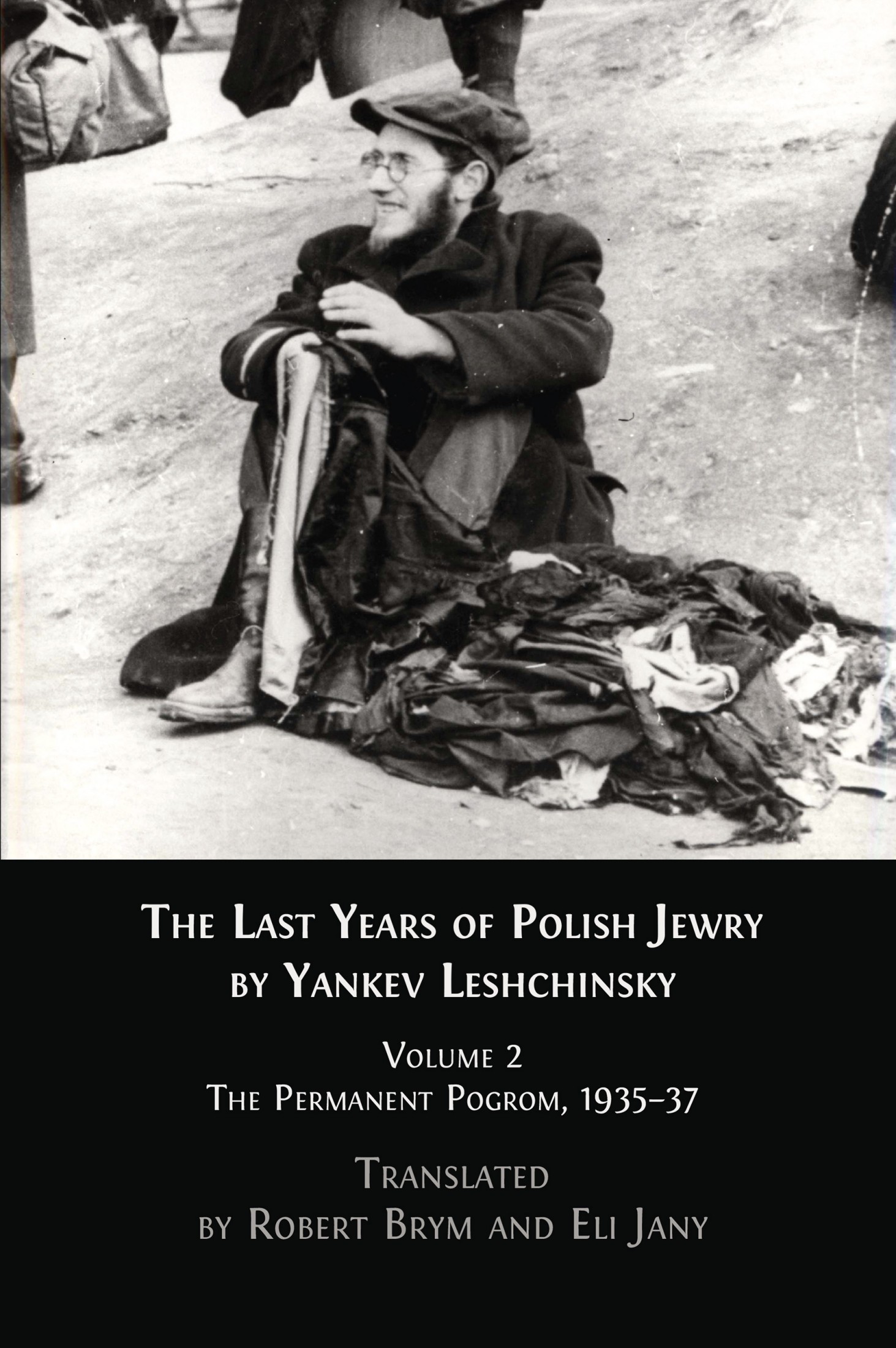

Fig. 4 Members of the Bund marching on 1 May 1936, Warsaw. ©Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem, archive item 1605_626, https://photos.yadvashem.org/photo-details.html?language=en&item=10143&ind=3

The most outrageous murder that terrified not just the Jewish population but also large parts of better Polish society was that of a five-year-old Jewish child at the Bund23 demonstration on 1 May 1937. Members of the Nara Party {Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny, the National Radical Party} shot into the Jewish crowd that stood on the sidewalk and watched the demonstration. They released a thick volley of fifty to sixty revolver shots and threw several petards. One can imagine what kind of panic such an attack can elicit. Victims were numerous. In the crowd stood a mother with her five-year-old son in her arms. One child, one eye in one’s head.24 A bullet hit the child, little Avremele Shaynker, in the temple. He died immediately. Fifty-year-old Feyge Nivan and her husband lay in blood. She was hit by three bullets in her stomach, foot, and hand. Hersh Drumlevitsh, a forty-three-year-old shoemaker, was wounded in a cheek and an eye. Lightly wounded were fifty-nine-year-old merchant, Avrom Englisher, eight-year-old Gershn Perlmuter, a sixteen-year-old Nisnboym and a few others. People who had no connection with the demonstration therefore suffered.

A few days later, the heroes of the Nara Party put out a flyer in which they expressed pride in having attacked Jewish “Marxism.” However, even this vile justification does not correspond to reality. For the Nara people, all Jews are Marxists, all Marxists are Jews, and five-year-old Avremele Sheynker, whose childish eyes were so delighted by a Jewish May Day demonstration, was certainly a candidate “Marxist.”

No less frightful and also no less vile and cowardly was the murder of a couple of Jews in Lodz {Łódź}. In September 1936, the Polish Socialist Party commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of “Bloody Wednesday,” a day when the party carried out an armed attack on the bloody Tsarist police force in 1906.25 The Lodz branch organized a large demonstration. The boyovke {combat unit} of the Nara party organized an attack on the demonstration, but came out of it badly because the socialist militia rebuffed them. Unable to engage in an open fight with the socialist militia, they sought an easier way to release their built-up patriotic energy. They went to Jewish streets and started breaking windows and heads. One of the passers-by, a Jew by the name of Glitsenshteyn, forty-four years old, was stabbed by a Nara man while exiting a streetcar and died on the spot. There were many other Jewish wounded. One cannot deny that Jews are responsible for Polish socialists commemorating the Polish struggle against the tsar; Jews played a big role in Bloody Wednesday, unfortunately not only as subjects, as active organizers and participants in the fight against the tsar, but also as objects because the tsarist regime also compensated Jews with pogroms for their participation in the Polish freedom struggle. In this manner, Polish Jews were paid twice with pogroms for their participation in the Russian revolutionary struggle, once by the tsar before the freeing of Poland and a second time by the Nara Polish patriots after the freeing of Poland.

The commemoration of the struggle against the tsar cost the Jews of Lodz dearly, but Jews in other Polish cities paid no less. In Warsaw, the Lodz scenario repeated itself. The Nara members attacked the socialist demonstration and had to retreat under attack and in disgrace. Having withdrawn from a strong opponent, they turned to a weaker “enemy”—the Jew. They took to the streets and beat every Jew they met and broke every Jewish window, and ambulances picked up the wounded: Yitskhok Goldman, aged fifty-six; Avrom Diamant, aged twenty-two; Ben-Tsien Marienshtat, aged fifty-four; Henek Lebenboym, aged twenty-one; Yisroel Berezniak, aged thirty; Dovid Vofshnit, aged twenty-one; and Yankev Gotfrid, aged twenty-one. These are the wounded who were registered, but as a general rule that we have confirmed many times, the non-registered wounded are at least three times as numerous.

On 30 January 1937 the official Polish telegraphic agency announced: “On 27 January this year on Pomorska Street three citizens of the Jewish faith were attacked and wounded or killed—Grinshteyn, Fishl; Khelmner, Shimen; and Tshariski, Fayvl. Khelmner died of his wounds. The authorities managed to arrest the murderer, twenty-five-year-old Jan Antczak, a commander in the National Radical Party’s militia. The murder was executed with a Finnish knife.”

Did the murderer have an unsettled account with the patriotic commander? Yes, a large unsettled account, although they had never laid eyes on one another. This is how the matter unfolded. On the evening of the 27th, in the National Radical Party meeting hall, the renowned priest, Trzeciak, made a presentation stating that all the misfortunes of Poland, both historically and at present, derive only from the Jews. If Jews were not in Poland, the country would be rich and powerful. Well, a Polish patriot, especially one who occupies such a high position as commander of the militia, will understandably want to free the fatherland of its enemies. So Anczak leaves the party meeting and immediately begins fighting against the enemies of the fatherland. Khelmner died, and was therefore entirely vanquished, and several others were badly wounded, and therefore only partly vanquished, but they at least became less harmful.

This commander was accused of the murder of two Jews, and it is worthwhile to consider his trial for a moment because it indicates the atmosphere in which such murders became not just possible but inevitable. First, the indictment stated that “Glitsenshteyn was murdered in a beastly manner. He was already lying dead on the streetcar tracks while Anczak kept on striking his head with an axe until the head became a formless bloody mass of flesh.”

In response to the judge’s question as to whether he admitted killing the two Jews, Anczak joyously answered: “Yes, the Jews are spies, harmful people; at the demonstration they shouted anti-Polish and anti-religious slogans.” The judge: “Why did you kill Glitsenshteyn? He wasn’t even at the demonstration.” The accused: “But he is also a Jew.” To the judge’s question of whether the accused saw Glitsenshteyn’s open skull, Anczak responded: “Yes, I saw that. Afterwards I calmly left. This is what one must do!” (Folktsaytung, Warsaw, 22 May 1937).

Here is how Jews fall from murderous hands because they are Jews and because a party that openly preaches on behalf of the murder and extermination of Jews and that arms its members operates legally. On 9 November 1936 someone suddenly started breaking the windows of Yosef Berkovitsh’s little shop at 11 Kilinskogo {Kilińskiego} street in Lodz. Not every Jew is terrified by every bang on a window. The owner of this shop went out and ran after the person who broke the windows. The vandal immediately pulled out a revolver and started shooting Jews who had meanwhile assembled. Two Jews—Berkovitsh and Zendl—were so badly wounded that they died the next day. Two other Jews, Mendl Rubenshteyn and Moyshe Vayszam, were also badly wounded but remained alive. The question remains as to whether their survival will be enjoyable. Who was the shooter? An eighteen-year-old youth, Tadeusz Shanyavski, in whose pocket a National Radical Party membership card was found (Nayer Folks-blat, Lodz, 10 November, 1937).

To convey the mood of the Jewish population in these murderous days is impossible. Tens of thousands of Jews took part in the funeral processions, led by representatives of the kehila.26 They protested and cried, fainted and demanded physical defence against the hooligans, who were openly armed and openly incited to commit murder. Panic encompassed the Jewish population, and mothers were afraid to let their children out on the streets.

The same type of murder also occurred in Kalisz, where two Polish youngsters, one eighteen and the other fourteen, murdered a seventeen-year-old Jewish boy, Manyek Kronenberg. They confessed that they did not know him and had never before seen him, but they frequented the party office, where they heard much talk about Jews as the worst enemies of Poland, and they wanted to accomplish something, so they stabbed the first Jew they encountered.

Such “political” murders numbered forty or fifty in the last two years. We will not recount each one. However, it is a moral obligation at least to recall the fallen member of the {Zionist} Pioneers group, Fride Volkoviska, eighteen years old, who was shot through a window of the Pioneers house on their farm in Grokhov {Grochów} near Warsaw. It was determined that the murder was executed by a member of the National Radical Party.

We noted earlier the poisoned atmosphere in which rural Jews lived. Let us now provide an example showing how far the wildness reached in the cities. In July 1936, not far from Warsaw, near Shvider {Świder}, two Jews were swimming, a young man by the name of Hokhman and a young woman, Fridman. They both began to drown. She managed to reach the shore but the young man died. The young woman related that the whole time some Christians stood on the shore and heard the shouts of Hokhman, who struggled for an entire quarter of an hour with the waves, calling out and begging for help—but the Christians laughed and said: “Let there be one less Jew.”

We will later deal more precisely with antisemitic occurrences in many Polish cities that must be referred to by their proper name: pogroms. However, one defining feature of the tsarist pogroms, and certainly a very important one, is absent from the Polish pogroms—the number of casualties is relatively small, and in some pogroms no one was killed. That is true, at least, if we count deaths at the time of the pogrom itself. If one counts deaths including the number of people who were wounded during a pogrom and later died, the picture changes a little.

For example, the Brisk pogrom of May 1937 almost became best known for the fact that after sixteen hours of rampaging, pillaging, and beating, there was not one Jewish death but tens of wounded and hundreds of robbed stores. Some Polish newspapers that preach “cultural” antisemitism even expressed pride in the “humanism” of the Polish pogromists. In reality, this “humanitarian” pogrom entailed three or four Jewish deaths. We will soon explain the “or,” but first we turn to the three certain Jewish deaths.

Borekh Zilberberg, a forty-seven-year-old Brisk resident, had a watchmaking business at 41 Dombrovski {Dąbrowskiego} Street. During the pogrom they broke into his shop and beat him over the head with sticks. He suffered a stroke. He was taken to Warsaw, where he was operated on several times, but the operations were unsuccessful. On 29 May, after two weeks of inhuman suffering, he died. The authorities did not allow the body to be brought to Brisk or buried in Warsaw during daytime. At 3 a.m., when the city was fast asleep, they had to bury the body of the first victim of the Brisk pogrom. Only three of Zilberberg’s brothers and his wife were present. His wife fainted repeatedly.

A week later, the Jews of Brisk carried the second pogrom victim to their own cemetery: Lutenberg, a fifty-year-old tailor. During the pogrom they executed a real massacre at the poor tailor’s place. They shattered two of his sewing machines, tore up the bedding, broke the furniture, cut up everything he has working on, including a pair of officer’s pants, and smashed his head with a stone. We mention the stone last because, for a couple days, Lutenberg lamented his broken sewing machines more than the injury to his head. But the morning after the pogrom festival it was necessary to supply his wife and children with bread. A few days later he lay down, and in three weeks he gave up his soul to God.

Only four months later did another Brisk resident die—fifty-year-old Khaim Perlis. He, too, was beaten about the head with stones and sticks. He hung on for four months, but did not manage to twist out of the hands of the Angel of Death.

And here is the fourth of the “three or four” deaths mentioned earlier. During the pogrom, a Mrs. Grinberg was struck in the head with a piece of iron. Her skull was cracked and they barely managed to save her by sewing up her wounds. In a few weeks her condition worsened and she was operated on in Warsaw. She remained alive. But was she not jealous of her pogrom colleagues who had already been relieved of their suffering? Were the previously mentioned Brisk pogrom victims luckier than their colleagues in Pshitik who died on the spot and did not have to endure hellish brain operations, flickering for weeks before dying?

The same was the case for the victims of other “bloodless” pogroms. A whole year after the Minsk-Mazovyetsk pogrom, one of its victims, thirty-one-year-old Khaim Shimenovski, died in a Warsaw hospital. During the pogrom he was hit in the head with a stick and from then on he suffered until he died on 30 May 1937. The Grodno Jew, Leyb Shapiro, lay tormented in hospital for one-and-a-half years after receiving several head and chest wounds during the Grodno pogrom.

And the Pshitik pogrom? Everyone knows about the Minkovskis’ cruel murder. In addition, an entire family was killed, their deaths mentioned only in the official chronicle.

During the pogrom, shoemaker Gedalye Tishler hid with his adult children in his attic but the hooligans found them there and dealt them murderous blows with sticks. All of them were wounded, but not seriously. In any case, for a few days nobody could predict that in half a year the members of this family would be dead. At first, the daughter, twenty-three-year-old Feyge, died. Soon after, the twenty-two-year-old son, Yudl, met the same fate. And a few months later, the father died. The widowed mother prays for death because she has been left not only forlorn, broken, and psychologically ruined, but also physically weak and with absolutely no material means with which to live. To live?… Is this living? Is it not easier for those who had the good fortune to lose the world at the first blow to the head?

Not all residents of Pshitik are so unfortunate as to linger years before their redemption from life in the diaspora. Here is a lucky resident by the name of Den who did not suffer from the Pshitik pogrom—but was destined to die at the hands of a pogromist from Pshitik. Fate caught up with him in Radom, where the victims of the Pshitik pogrom lie. On 15 March 1937 he passed by the building where the infamous Pshitik trial took place. Den instinctively stopped. What sort of Jew could pass by the Polish courthouse where for the first time in independent Poland a verdict was reached that punishes those who defended themselves and frees those who beat and murder? Suddenly he heard a tearful cry from a Jew. A well-known pogromist from the Pshitik area, Stanislav Simtshik, was beating a Jew, a fruit merchant, seventy-year-old Yankev Ayznberg. Den started running over to Ayznberg but didn’t manage to get all the way there because the pogromist turned around and delivered a blow to his head with a stick. The blow was such that Den never regained consciousness and died a few hours later. A month later a short letter from his widow was published in the Jewish press: “My children and I are simply dying from hunger. Maybe good people will be found who can help us. Feyge Khaye Den.” We include Den as a victim of the pogroms for two reasons—first, because he was killed by an active pogromist from Pshitik, and second because if he had not been standing by the building in which the Pshitik trial took place, he would have perhaps avoided being killed.

We have so far discussed victims who to varying degrees were direct victims of attacks. However, there were no fewer indirect victims as a result of the pogrom atmosphere and especially pogrom fear. For example, there was a pogrom in November 1936 in Vilna. It was one of those pogroms that supposedly demonstrated the higher culture of the Polish pogromists, who are said not to murder as energetically as their tsarist or Petliura colleagues did. How should we categorize the death of the following Jewish victim? On 20 November 1936, National Radical Vilna students organized a prayer meeting in a church. The bishop blessed them. After prayers, and laden with the Bishop’s blessing, they let loose in the streets beating Jews and breaking windows. The seventy-year-old Jew, Borekh Feldsher, was walking in the street. Out of fear, he had a heart attack and died on the spot before the blessed students were able to approach him. Was he not a pogrom victim?

The mass pogroms: Grodno, Pshitik, Minsk-Mazovyetsk, Adzhival, 1935–36

In 1935–36 three large pogroms occurred in Poland: in Grodno, June 1935; in Pshitik, March 1936; and in Minsk-Mazovyetsk, June 1936. We view these three events as pogroms in the sense that they involved mass suffering and mass participation in the attacks and murders. Actually, one can speak of a mass-pogrom in one other place, because in Adzhival the attacks and murders of November 1935 had a mass character.

In Poland the attacks have persisted for years. They do not everywhere have the character of mass stands against Jews but of partisan excesses against a few Jews, a few stores, or a few fairs. The attackers do not always have the aim of murder. Sometimes their aim is more to frighten, elicit panic among Jews, and disorganize them, forcing them to run away and emigrate. Therefore, it is very difficult to distinguish between true pogroms and excesses. However, it is in the nature of small-scale pogroms to be transformed into mass events.

Until a certain time, the policy of the government was clear: tolerate a few small pogroms as a good way to assist its entire anti-Jewish economic policy. Make the air suffocating for the Jews, but don’t allow mass pogroms that would interest the outside world in the condition of the Jews in Poland. However, it seems that in the last few months the tactics changed and bigger pogroms are now tolerated, but only with beatings and robberies without serious physical injuries. This may be a clearly thought-out plan to let the Jewish and also the non-Jewish world know that there is no longer a place in Poland for the Jews. Emigration is the only escape. This became the idée-fixe of leading Polish figures; all means became kosher. One can believe that if mass pogroms without many deaths don’t work and the Jews remain stubborn, they will turn to pogroms on the Ukrainian model with mass slaughter.

Let us consider the three large pogroms in chronological order. In doing so we will endeavour to consult the indictments that are certainly not inclined to take the Jewish side. We begin with Grodno, allowing the indictment to trace the evolution of the pogrom:

In Grodno on the evening of 7 June 1935, there took place the funeral of seaman Kushtsh, who was wounded on 5 June by Shmuel Shteyner and Meylekh Kantarovski during an argument in a dance class. (Both Jewish youth were convicted by the Grodno area court, one sentenced to 12 years and the other to 2 years in prison.) Apart from family, friends, and acquaintances, the approximately 1,000 people who were then in the street attended the funeral. On the way to the cemetery the procession grew steadily, approaching 2,000 people by the time it reached the military cemetery. After the funeral a crowd of close to 1,000 people let loose. It was led by the student, Sunak. Panasiuk, Martshintshuk, Zigmanski, and Zhukovski riled up the crowd. The police told the crowd to disperse, but Panasiuk gave a speech in which he said: “‘We have buried a friend whom Jews slaughtered. We must seek revenge for his death! Down with the Jews! Death to the Jews!” Then came the response from the crowd: “Down with the Jews! Beat Jews so that great Poland will live!” Panasiuk shouted: “We already have three facts in Grodno. In 1930 Jews murdered Moravski, and this year they killed a peasant from Martshinkan and Kushtsh. Tomorrow they will do the same to us! Enough fine words! We need to take action! Let us go to town and show what we can do.”

Seeing that Sunak was arranging the crowd in rows, Panasiuk shouted out: “Guys, come with me to beat Jews and avenge the death of our friend! For one of ours, a hundred Jews!” This exhortation mobilized the crowd, which set off to the city, tearing out fence posts and collecting cobblestones along the way. Led by the five men mentioned earlier, the mob set off by way of Skidler Street, Yeruzalimska Street, Brigidska Street, Batori Place, Dominican Street, Kalushinska Street, and Napoleon Street, breaking the windows of Jewish stores and dwellings, and beating Jews whom they encountered. The excesses continued from 6:30 to 10 p.m. Around midnight they moved to the suburbs.

During the excesses against Jews the following participants were detained and identified: Olga Zhuk, who broke windows on Yeruzalimska Street; and Kozlovski, who egged on a group of about 100 men to beat Jews and break windows. On Brigidska Street the police detained Mazhdzher, who held a stick and yelled, “Beat Jews,” and on Vitoldove Street they detained Balitzki on whom they found a stiletto. While taking him to the police station he resisted arrest. On Kalushinska they apprehended Aleshtshik. His hands were bloodied. With a larger group he had been knocking out windows. On Napoleon Street Yarashevitsh and Romantshuk had been breaking windows. The main leader, Panasiuk, fled. However, on the 17th he gave himself up to the police and confessed.

During the excess the lightly and heavily wounded Jews included Yisroel Berezhinski, Yitskhok Leypunski, Hirsh Grinblum, Iser Atlas, Frantshishek Kovalski, Shmuel Kleynbart, Ber and Avrom Burde, Gotlib Levin, Yankev Gradunski, Gedalye Bekher, Leyb Butshinski, and Shloime Pozniak. Berezovski and Bekher died of their wounds. The inquiry ascertained that windows had been knocked out of 183 houses and eighty-five stores. Damages totalled about 30,000 zloty. Trials concerning theft and robbery of property during or immediately after the excesses (there were more than ten of the latter) were transferred to the municipal court or were the subject of separate inquiries.

Of the seventeen accused Poles, only Panasiuk and Plotzki confessed during the inquiry. The others denied participating in the events. The prosecution summoned seventy witnesses to the trial.

According to the indictment, thirteen Jews were wounded, two of whom died. In reality, many more were wounded. Forty people, most of them lightly wounded, were registered in the kehila. The number of those who suffered materially was also greater than stated. Three hundred people registered in the kehila as having suffered material damages valued in total at more than 60,000 zloty. However, it is actually not possible to quantify the bodily and material damage of a pogrom. The shoemaker Gotlib Levin lay in hospital for seven days. The typesetter Leyb Butshinski took seven weeks to heal in Grodno and Warsaw. It is difficult to say whether they fully recovered and their capacity to work was fully restored. Every pogrom leaves an imprint lasting years on reciprocal relations between Jews and Christians, on the mood of the Jewish masses and their sense of security, and on Jewish participation in social and political life.

Grodno had never experienced a pogrom before. For many years, Jews composed a majority of the population, and only in independent Poland did their percentage begin to fall—from 60% in 1897 to 54% in 1921 to 42% in 1931. The Polish population grew proportionately, and with it elements that charged into the mercantile and artisanal livelihoods that had been in Jewish hands for centuries. Polish officials and members of the free professions grew in number even more quickly. These were the two occupational sectors that were the most active bearers and disseminators of antisemitism in Poland.

The trial concerning the Grodno pogrom that took place in November 1935 first uncovered the entire dirty pus that spurted from the infected antisemitic abscess. Aside from one worker who regretted his actions and sought forgiveness, all of the accused vehemently denied everything or audaciously and explicitly declared that they had no regrets, that they had to take revenge, and that they would continue the struggle against the Jews by all available means.

A scene took place that shocked everyone in court. A twelve-year-old orphan, Yosef Blekher, testified that he was standing near his home when his father (a poor tailor who had worked hard for a piece of bread his entire life) was cruelly murdered in the middle of the street, his head beaten until he fell, bloody and unconscious. After this scene, which really shocked everyone in the court, the prosecutor asked the main defendant, Panasiuk, if he regretted his actions. The answer was savage and clear: he had no regret, he said; the Jews got off easy. But what can one expect from the Panasiuks and their friends when the lawyers themselves made far more terrifying speeches in court openly calling for the Jews to be rooted out and for the struggle against the Jews to continue by the same means that Panasiuk and his friends used?

By the time of the trial there were already in Grodno three pogrom victims—Moyshe Lipski, Yisroel Berezovski, and Gedalye Bekher. More than ten Jews were seriously wounded and crippled and more than thirty others were lightly wounded, which ruined tens of families and created a pogrom mood in the city for months and perhaps years. How did the court punish the hooligans? Here is the verdict:

- Six accused (Zhukovski, Yudzhak, Baletski, Maleiko, Nobeykon, and Losate) were freed.

- Seven accused (Mozedzhezh, Zhukov, Bielski, Aleshtshak, Yaroshevitsh, Romantshuk, and Plotzki) received six months in jail.

- Three accused (Kozlovski, Martshintshuk, and Zigmanski) received nine months in jail, and the main accused at trial, Panasiuk, received the most severe punishment, just one year in jail.

- Nine of the tried men had their sentences delayed for five years.

- Panasiuk and Zygmanski were freed on bail of 200 zloty each.

This verdict instilled fear in the Jewish population—not only in Grodno—and deeply upset all Polish Jews. And not only Jews. Grinyevitsh, the Chairman of the court in the Grodno trial (and vice-Chairman of the Grodno regional court), entered a “Votum Separatum.” We consider it important to provide the conclusions of this historical document, the contents of which strongly object to the court’s verdict:

- “Such occurrences,” the Votum Separatum says, “are a blow to the foundations of legality in Poland. They lower our country in the public opinion of the civilized world.

- “State power should cut off excesses at their roots without pity. Courts must punish the guilty to the fullest extent of the law.

- “Weak punishment can only contribute to the audacity of people like Panasiuk and his friends, creating among them a sense of inappropriate defence by the state in connection with the lives and property livelihoods of Jews.

- “The bearing of the accused in court is a demonstration of their considerable ill will.

- “The assertion of one witness that on the second and third day after the events Jewish youth began to organize fighting groups with the aim of revenge is an ungrounded supposition because they did not organize for the sake of revenge but for self-defence in case the events recurred.

- “The responsibility of the accused is not lessened by the claim that their actions were an expression of anger generated by the murder of Christians. Panasiuk and his friends must well understand and remember that in a lawful regime one can punish only those who are directly responsible [for a crime], and punishment is solely the responsibility of the court.”

For all these reasons, Chairman Grinyevitsh held that Panasiuk should be imprisoned for three years rather than one year; Kozlovski, Martshintshuk and Zigmanski for two years instead of nine months; and the remaining seven defendants, one year apiece instead of six months.

It must be noted that, a few months after Panasiuk was freed, he placed a bomb in the clinic of the Grodno Society for Safeguarding the Health of the Jewish Population.27 It caused only material damage, but only because it exploded before opening hours. If it had exploded half an hour later, there would have been many victims.

One must also add that at the appeal trial in Vilna in May 1936, even more severe punishments were handed out than those recommended in the Votum Separatum of the Chairman of the Grodno court: Panasiuk got five years rather than one year, Kozlovski, three years rather than nine months, and Martshintshuk and Zimanski two years instead of nine months, with the sentences of the rest remaining the same. In the end, however, the pogromists were placed in the category of political activists, and amnesty for political criminals was granted to all those sentenced.

If the Grodno pogrom struck like a bolt from the blue because the Jewish population did not take the local Endek organization seriously enough, the same cannot be said for the other pogroms. In Adzhival, Pshitik, and Minsk-Mazovyetsk, the pogroms were the high point of terrorist campaigns that had raged for months in the surrounding region. These anti-Jewish terrorist campaigns caused many wounded in Adzhival, Pshitik, and surrounding towns, and even one murder in Minsk-Mazovyetsk (of Yisroel Tsilikh) before the pogroms. Around Pshitik, the Endek party concentrated a force that was supposed to clear Jews out of a district of about ten towns and provide an example of how to do without Jews in both buying and selling. This pogrom campaign in Adzhival brought about unrest of such proportions that the police had to shoot and kill eighteen peasants. Several police officers were also killed. The number of wounded on both sides was much larger.

The Adzhival pogrom wave is well described in the indictment read at trial in June 1936. We will therefore let the indictment speak for itself even though it greatly minimizes Jewish human and material losses. However, it describes well the entire hellish atmosphere created in the Jewish population and strikingly depicts the demagogic and criminal work of the Endek party, which invented the vilest defamations and wildest fantasies to rile people up against Jews. Unintentionally, the indictment read at trial also offers a splendid picture of what letting pogrom agitation loose can precipitate and how difficult it is afterwards to oppose a mass of people who are freely allowed to be provoked and incited to violence.

Twenty peasants were brought to trial for beating Jews, robbing them, and resisting police. The indictment describes the events thusly:

Vigorous activity on the part of the Endek party in the territory of Ossa and neighbouring townships dates from 1935. The Endeks engaged in such an extensive propaganda and recruitment campaign among the peasants that in many cases the entire adult population of a village belonged to the Endek party. The economic crisis in the countryside created fertile ground for agitation that was strengthened by demagogic, anti-Jewish slogans and that saw in the Jews the sole reason for every evil in Poland. Together with the development of the Endek organization there took place a boycott that involved not buying and preventing others from buying from Jews. This agitation was at first quiet and restrained. Later, with the growth of political circles and the recruitment of the masses to the ranks of the Endek party—including irresponsible people, often with a criminal past—recruitment got out of hand and agitation became sharper and took on violent forms, leading inevitably to anti-Jewish excesses.

On Wednesday, 20 November 1935, members of the Endek party in Adzhival, who were assembled in their headquarters, went to the market where a fair was taking place. They formed groups that began walking around the market demanding that the people who were circulating among the stalls and tables not buy from Jews given that the same goods could be purchased from Christians. Clusters of people assembled around these groups, and at a certain moment, due to the pushing of the masses, they began knocking over the Jewish stalls. A group of 30–40 men tipped over the wagon of the Jew, Aleshitski, thereby breaking some of the dishes it contained, and Aleshitski himself was badly injured.

Other groups placed themselves near the Jewish shops. Some went inside, asked to see merchandise, and walked off with it without paying. Merchants who demanded payment were beaten….The merchant Yankl Baritski was hit in the stomach by a stone, and Alter Veksler was hit twice in the face, loosening some of his teeth. Veksler’s wife ran after the assailant and stopped him, but he pushed her away. His confederates proceeded to encircle and beat her.

On the following market day, 27 November 1935, similar excesses took place in similar circumstances, the only difference being that they did not overturn Jewish stalls because the Jewish merchants, afraid of what might happen, did not set up their stalls. On that day, directly after a meeting at the Endek local party headquarters, party members began shutting down Jewish stores and beating Jews.

A group of 150 men entered Moyshe Kutshinski’s mill, threatening and forcing the peasants who were there to remove the grain they had delivered. They broke the sluices, drained the water, and shut down the mill. They beat the Jews, Khaim Lenge, Meyer Nayberg, Khaim Mlinkevitsh, Yehoyshue Milshteyn, Hershl Leyb Groskop, Leye Fayfer, and Itsik Baritski. With sticks and stones they broke the windows of the houses of Laye Fayfer, Peysekh Rosneholts, Chaim Lenga, Yosl Lerman, and Avrohom Karkovski. While shutting down the stores a few participants beat the Jew, Abram Vayntroyb.

…This time too, although the patrol had been reinforced and numbered eight police officers, because of the aggressiveness of the masses they could not control the situation unless they used guns. So they adopted a wait-and-see attitude, observing the most active individuals who were already known from the events of 20 November: Antoni Grushetzki, Yuzef Khrobak, Pyotr Vzhaski, and Adam Bartos from the village of Asa, as well as Stanislav Grushetski from the village of Zarki, Yan Dzhuba and Zhembitski from Byelin. The last named, armed with a threshing flail, took part in beating many Jews, and Yan Dzshuba threw a stone that hit Baritski’s foot.

The two outbreaks in Adzhival were repeated in Pshiskhe on 28 November 1935, and according to available information excesses were also being prepared in other places. This situation threatened the social order, so security forces were compelled to act forcefully against the people whose activities were liable to endanger it. On the evening of 29 November 1935, several members of the Endek party in Adzhival were arrested on suspicion of provoking antisemitic excesses. Then the members of the aggressive party came out against the police decree and sent envoys to the neighbouring villages.

Shortly afterwards, groups of peasants were drawn to Adzhival. Most were armed with sticks, some with pitchforks, axes, and the like. At about nine o’clock Adzhival was surrounded on all sides by a mass of peasants. The inquiry later determined that Endek envoys and “runners” had sounded the alarm to the population of the neighbouring villages. Those who did not want to join the march on Adzhival were terrorized and forced to do so, so only a small number of adult men in a whole series of villages covering a radius of eight kilometres succeeded in remaining in place.

To rile up the masses, a rumour was spread that Jews in Adzhival had arrested Bishop Sandomirski, who was staying there on 28 November, that Jews were torturing priests, and also that the police in Adzhival are in fact not police but Jews dressed in police uniforms. Among the provocateurs only a few people were successfully identified because in most cases an unidentified person rode through the villages on a horse alarming the peasants and telling them to go to Adzhival.

The assembled groups around Adzhival did not dissipate following the police demand, instead assaulting the police with jeers, contempt, and threats. Having an order not to allow the mass into Adzhival, the police repelled the peasants many times and fired warning volleys. However, at certain points this did not work and the situation became more dire. Arms were used, wounding and killing some peasants.