4. The Pshitik pogrom

Translation © 2024 Brym & Jany, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0342.04

The “Jewish pogrom”

Jews apparently carried out a pogrom in Pshitik against “goyim” {gentiles}! Did you know about this already? We did not know about it in Poland either, and yet I have the indictment right in front of my eyes and am reading it in astonishment. It turns out that the Jews of Pshitik have carried out a pogrom against the Christians! The Pshitik Jews, who had been tormented and persecuted for months leading up to the pogrom, who were afraid to turn up at the market with their merchandise, who were terrorized by every little Christian boy—these very Pshitik Jews, on the infamous date of 9 March 1936, during the fair, when there were thousands of peasant villagers in town, threw stones at the Christians and beat them with clubs and iron rods. Not only did they beat them; they also shot them many times. With their shooting and beating of “goyim,” the Jews provoked an attack.

For this reason, the indictment begins with the fourteen Jewish defendants. The Jews face harsh sentences. There is not one word about the fact that they were compelled to protect and defend themselves against a bestial mob, an agitated crowd that had already pillaged and beaten and was prepared to kill. Of course, it is difficult to establish precisely when a person has the right to defend himself with the most extreme means. Is it in the beginning, when he is first attacked, when he still has strength and the genuine opportunity to save himself from the wild assailants? Or is it only when he is lying wounded, defeated, and unable to move that he has the right to reach for his revolver? The investigative authorities ought to have asked themselves this question and determined a clear answer: did the couple of young Jewish men shoot when the pogrom was already in progress or before it began? It is indeed unimportant whether the pogromists killed the Minkovski family before or after the shooting. The pogromists would in any case have killed, if not the Minkovskis, then others. The indictment itself proves that the pogromists were satisfied when they caught the scent of Jewish blood, when they saw the blood-drenched bodies of the Minkovskis, who were by that point not even recognizable.

What exactly is the indictment’s approach to the events in Pshitik? It begins with the fact that several peasants resisted the efforts of the police to create order. It would, of course, be logical here to dwell in detail upon the events, to paint a picture of the pogrom, of the mob gone wild, of the agitators inciting them and calling for pogroms and murder, of the attacks on Jews and the beatings—in short, a picture of the true pogrom. It would then make sense to describe how Jews tried to defend themselves, some with revolvers and others with clubs. However, the indictment’s author takes an entirely different approach. He drags the Jews out into the foreground; he places those who had the audacity to defend themselves front and centre. The indictment begins as follows:

The Jews, Yankl Avrom Khaberberg, Leyzer Feldberg, Yankl Zeyde, Refoel Honik, Moyshe Fersht, Shoyel Kengel, Moyshe Tsuker, Leyb Lenge, Yitskhok Bande, and Yitskhok Fridman face the following accusation: At the same time as the clash between the police and the peasants, they attacked the peasants, who were rushing to drive home, beating them with clubs and other instruments, throwing stones at them, and thereby causing Jozef Szymanski head wounds that led to mental health issues, and wounding many other peasants, who sustained bruises and edema.

This introduction alone already turns the whole case backward. Peasants are racing to escape the market, peasants are rushing home, and Jews turn up and start beating them. Innocent little lambs are attacked by wild Jewish beasts who will not let the lambs go home in peace and quiet! That’s what the Pshitik Jews are capable of! And that is just the beginning. The indictment continues: “The Jews are further accused of intending to murder the peasants who were rushing to leave the market, since they shot at them! However, they failed several times to hit their target, since only three peasants were seriously injured, one of them life-threateningly.”

Again, the peasants are bothering nobody, laying a hand on nobody; they are nice, quiet, peaceful little Pshitik Christians. The poor guys just want to run home to their wives and children as quick as they can. The previously mentioned ten Jews, however, are armed with revolvers and ready and willing to murder. These hostile Jews shoot with the clear intention to murder, but they do not succeed.

Then come additional specific accusations against individual Jews. Sholem Leska is accused of “attempting to murder the peasants who were walking around the market, shooting from the window of his house and murdering one peasant.”

Thus, again, the peasants are walking calmly around the market, and the Jew Leska shoots from his window, simply for the purpose of murder. However, this same indictment establishes that the window had been shattered. Well, who smashed the window through which Leska subsequently shot? If the peasants were simply strolling around peacefully, why on earth were Jews’ windowpanes smashed?

Next comes the accusation against Yankl Bornshteyn, who also attempted to murder peasants. He shot, but missed.

Only after the indictment finishes with the Jews, the main criminals and primary defendants, does it move on to the forty accused Christians, who, “after the peasant had been shot dead,” attacked Jewish houses in groups, “shattered doors and windows, broke into the houses, destroyed all of the furniture, smashed everything they came across, beat all the Jews, murdered the Jews Yoysef and Khaya Minkovski, seriously wounded five Jews, and more mildly wounded several additional Jews.”

Everything is now clear. If the Jews had not beaten the peasants, who were rushing home, if the Jews had not shot at the peasants who were walking peacefully around the market, there would have been no pogrom at all, and Pshitik would have remained some anonymous, grubby town, rather than becoming world-famous. It is clear who the guilty party is.

This same spirit will undoubtedly carry over into the trial set to begin on the second of June in Radom, in which fourteen Jews and forty Christians stand accused. However, the former are accused of crimes carrying sentences of five to ten years imprisonment, whereas the latter face far less serious sentences.

If one sets the indictment aside and starts reading the justification of the accusations, one sees that the writer got so carried away by the facts in front of his eyes that he forgot what he was supposed to be justifying and inadvertently let a lot of truth slip out. He remembers his objective from time to time and emphasizes that Jews armed themselves, that Jews bought revolvers in Radom, that Jews were even seen to have brought nine revolvers. Among the Christian population, people were saying that Jews were preparing for a general attack. The overall picture, however, even as it is painted in the justification of the indictment, ultimately reveals the truth that Jews had been living in a state of panic for months, that the Endeks had long ago implemented a boycott of Jewish businesses, using force to prevent people from buying from Jews, that Jewish windowpanes had long since been at their mercy, and that a pogrom mood could be felt in the air that day.

Let us consider just a few sketches taken straight from the justification of the indictment. People broke into the home of Yankl Bornshteyn through the windows. They smashed the wardrobe, table, and chairs, and struck Bornshteyn with clubs and stones. The investigation found forty-eight stones in the home, many of them large. So when did Bornshteyn shoot—before they threw the stones or after? While the pogromists were in the home, they were obviously not throwing stones. This clearly indicates that Bornshteyn wanted to chase off the pogromists by shooting—that is, of course, if Bornshteyn even shot at all, which he himself denies.

Sholem Leska confessed to shooting and killing the peasant, and his fate is very grave indeed.

Even in the dry, bureaucratic description, the scene in the home of Feyge Shukh makes a powerful impression. She hid her eight children in the attic and stood by the door to her home, heroically fighting against a crowd of peasants who beat her with clubs, inflicted three severe head wounds, fractured her spine, and caused many bruises to her chest and back. She saved her children though.

Here is another moving scene: in the heat of the pogrom—in the greatest peril, a seventy-year-old Jewish woman named Yokheved Palant went out into the street to look for her children. The pogromists surrounded her and beat her brutally, causing numerous head wounds.

A shocking impression is left by the description of how people broke into the home of the cobbler Minkovski, beat him cruelly and brutally over the head with crowbars, and dragged his children out from under the bed. The cobbler’s wife fell under the blows and the cobbler himself was transformed into a pool of blood.

As you read the bureaucratic description, you see before your eyes Kishinev, Homel, Bialystok, and tens of other major cities where pogroms took place during the tsarist period. The same cruelty, the same sadism, the same brutality and bestiality, the same loss of human appearance and human feelings.

At the same time, there was something that brought comfort. Jews, it appears, defended themselves! The Jews of Pshitik did not allow themselves to be slaughtered like sheep! The indictment does exaggerate, but something did take place. There were young Jews who were ready to make the greatest sacrifice to prevent our name from being disgraced and our honour from being mocked!

5 June 1936

The scene is set

I want to begin my report on the Pshitik trial with the following picture. More than 400 witnesses had to be sworn in. They were brought into the hall in groups. First come four groups of gentiles—320 witnesses, mostly young men with healthy, rustic faces. Dressed in boots, they enter the hall resolutely and confidently, almost joyfully, almost brashly. They answer prosecutor’s questions loudly, insolently, provocatively, almost belligerently. So it goes, one group after another—the floor trembling under the 320 pairs of healthy boots, the stamping of their metal heels, the scraping of their thick soles.

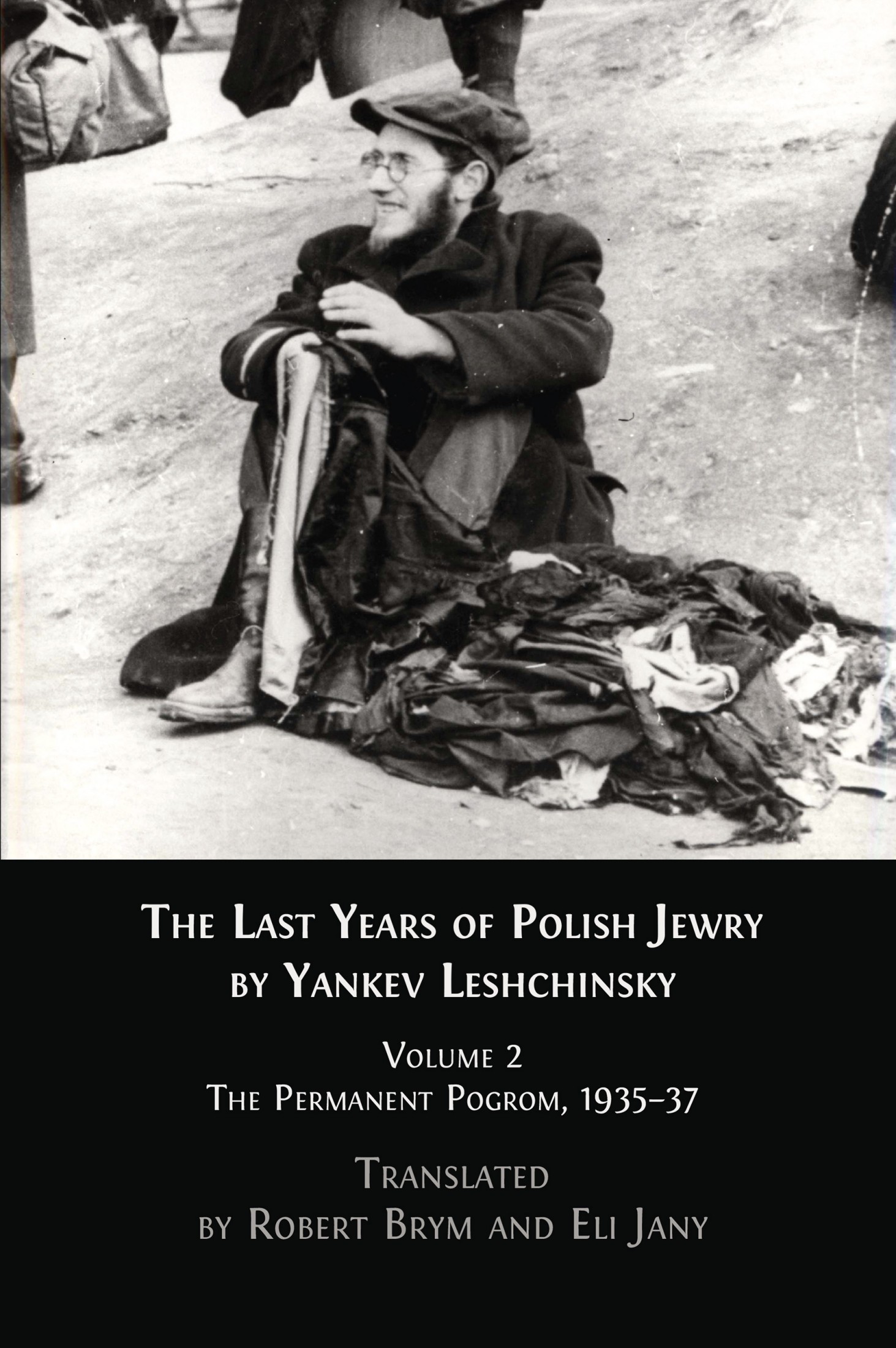

Here come the eighty Jewish witnesses. First, the five orphans of the murdered Minkovskis, between six and fourteen years old. After them, the grandmother, over seventy years old, and ten aged, stooped men, old women so tiny and short you can hardly see them—a whole group of men and women, shabby, faded, dejected, hesitant, with lost faces and extinguished eyes. They look almost like a pack of beggars and panhandlers, at least like a group of wanderers, arriving from a long and difficult journey, tired, far from home, depleted, longing for rest and security.

I was standing very close to the judges’ table and could observe the impression that the arrival of this group of witnesses made on everyone—the judges, the lawyers, and the journalists: crushing, shocking! It was a deeply unpleasant picture. The contrast with the young peasants’ suntanned faces and tall figures was too great. Everyone was seized by entirely different feelings. Against their will, a thought flashed through everyone’s minds, even the viciously antisemitic lawyers’: before our eyes stand the beaten and the tormented, the harassed and the hounded.

At that moment, the trial acquired its true historical significance, and all the investigations, speculations, interrogations, and pains to pick out the guilty and the innocent seemed superfluous, somehow foolish and absurd. It is clear, after all, that the strong are the ones who do the beating. It is even clearer that the weak are the ones who get beaten. What was the point of going through such long, drawn-out ceremonies?

In truth, the matter is not quite so simple. These weak grandfathers and weary fathers, these stooped grandmothers and wrinkled mothers have children. Not all Jewish youth are little and skinny these days, and even when they are little and skinny, they are strong with an entirely different will and sense of courage, not with a passive will for God to rescue and redeem, but an active will to stop others, here and now, from spitting in their face. Their will is to respond to an attack not with prayers and petitions to God, not with begging and pleading, but with a bullet.

In this sense, the figure of the Jewish tailor boy Leska is truly symbolic. He is not yet twenty years old, short and skinny, near sighted and bespectacled. He confessed that he had fired a revolver. He hit a peasant and killed him instantly. We are not judging now on the third day of the trial whether Leska ought to have fired at the moment he did. But Leska from Pshitik, still in a long kaftan, just a couple years out of the yeshiva, a member of the Mizrakhi religious Zionist movement, a young man who had never seen or heard from his father or grandfather about weapons, about shooting, about revolvers and rifles—this young man was armed and ready to fight for himself, his parents, his little brothers and sisters.

The forty-three Christian accused are practically all cut from the same cloth—peasant youths, the first generation to don city clothes: shoes, a tie, a half-white collar, an ironed suit, hair combed with a part. This is the first generation of peasants to graduate elementary school. They arrived to occupy the market and fair sites, and they attacked the Jews.

When the chairman starts asking each of the accused about their name and past, the difference between the Jewish and non-Jewish small-town youth immediately becomes apparent.

“Have you ever been to prison?” the chairman asks, and almost all of the Jews answer, “No!” A few have served time, but for Communism. Many of the Christian have served time for stealing laundry or a horse, for fighting, or for assaults against Jews. Theft, brawling, and assaults against Jews—these are the commonest crimes in villages and in small towns which are themselves practically villages or are located right next to a village.

One must not overgeneralize, of course. Poland has no shortage of Jewish thieves and louts who go around with knives, ready to stab someone at the slightest confrontation. Nonetheless, both these types are less common among Jews. The main point is that here in the courtroom sit two highly disparate groups. On one side, assailants, brawlers, hooligans, people who allowed themselves to be convinced that Jews are responsible for all misfortunes. On the other side, people who, in the worst-case scenario, wanted to defend themselves, tried to defend themselves, refused to hide in the attic or basement listening to the cries and screams of women and children being beaten.

I say “in the worst-case scenario” because the accused Jews all deny that there was a self-defence organization, that they had several revolvers, and they assert that they wanted to defend themselves against hooligans and murderers, that every person has a right to self-defence.

The disparity was likewise glaring as they answered the chairman’s questions. The brawlers were audacious, sure of themselves, even a little impudent. Several even dared to say that they were not willing to answer now and reserved the right to speak later. The chairman of the court’s angry words were of no use—they remained stubbornly silent. The Jewish accused were not entirely sure of themselves, with fear on their faces and distrust of those in whose hands their fate laid. At the same time, they conducted themselves with dignity and intelligence. Their responses got straight to the point and they refused to be twisted around by the antisemitic lawyers.

Let us briefly consider the judges and lawyers, and we will then have before us all the actors in the tragedy currently playing out in the Radom courtroom.

The chairman of the court, for the time being, makes a very favourable impression. His conduct is impartial, serious, and honest. He made a speech to the Christian witnesses that might serve as a key to how he wants to conduct the trial, and perhaps also the trial’s outcome. He demanded from them the truth, because only through truth can the hatred and hostility between different segments of the population be reduced. There have been enough victims, and the discord has come at a heavy price; every witness must strive not to exact revenge, but to help establish peaceful relations by telling the truth. The chairman spoke these words with a resolute and commanding voice. Unfortunately, this did not make much of an impression on the Christian witnesses, and they continued to conduct themselves in an impudent and provocative manner. One got the impression that there were more pogromists, and more dangerous ones, among the witnesses than the accused. The chairman also made a speech for the Jewish witnesses, but in a somewhat different style. Here, he felt it necessary to mention that an oath without a rabbi is still an oath, since God is everywhere.

At the same time, however, the chairman has two court assessors {investigating magistrates} who are noted antisemites, and they make no effort to hide their antipathy toward the Jewish accused.

The Jewish accused are defended by a group of brilliant and widely renowned lawyers. Alongside the Jews Berenson, Ettinger, Margolis, and Kriger, there are the Christians Petruszewicz, Paschalski and Szymanski. Petruszewicz is a lawyer from Vilna, one of the old-time Russian political defenders, a true friend of humanity, a true leftist, and an eminent and esteemed jurist who is also a professor at Vilna University. Paschalski is the president of the Riflemen’s Association, an organization of Pilsudski’s that plays a major role in Polish political life.

The pogromists are represented by fifteen antisemitic lawyers. Their best lawyers from Warsaw and Lodz, in addition to those from Radom, felt that it was their “moral” duty to come and save the pogromists. From the very first moment, they made it clear that they had come not for money, not for the sake of this or that individual defendant, but to save the Polish nation from the Jewish leech. It is a fact that not one of them is accepting any payment. They have come here to spend whole days sweating in court solely to perform a good deed. In short, they are convinced, tenacious, proficient antisemites. Among them is a rather beautiful young female lawyer, with a pleasant face that is entirely unsuited to the venomous hatred that sprays from her mouth every time she questions a Jewish defendant. She is, however, very active.

The scene has been set; the actors have taken their places. With racing hearts, the Jews of Poland, and perhaps also Jews around the world, snap up every bit of news about what is happening onstage.

19 June 1936

Leyzer Feldberg

The two days that I spent at the Pshitik trial were truly historic days. This was not so much because great heroes appeared and exposed the entire tragic situation of a group of people who are attacked daily, require police protection but do not receive it, and are nevertheless forbidden from defending themselves, and especially from organizing for the purpose of self-defence. Alas, there are no great heroes at the Pshitik trial. Almost all the defendants have set out to prove that they could not have shot, would not have wanted to shoot, and did not even think about beating pogromists. The defendant Leska represents an exception in this regard, but we are afraid that this is only because he has ended up in a situation in which he is forced to confess and plead self-defence against assailants as his motive. Leska, as is known, shot from a window and killed a peasant, and he is facing the heaviest sentence.

Let us be impartial toward all the Jewish defendants, who sit before the court in terror and anxiety as they insult and disgrace their own honour. On the day of the pogrom, they conducted themselves far more heroically, far more courageously, far more admirably and honourably. More than one hooligan’s back got a taste of a Jew’s club or iron bar. At that moment, they behaved as healthy, normal people ought to when they are attacked.

Nonetheless, the two days of the trial were historic. The proceedings were raised to a high level insofar as the pain and grief not of individual people but of all three million Polish Jews, drowning in misery, were established.

The credit for all of this is due to an ordinary Jewish man, a very simple man of the type immortalized by Sholem Aleichem in Tevye the Dairyman. These simple people, steadfast in their faith, firm in their conscience, intact and unbroken in their nature, candid and generous, unafraid for their own skin and prepared to serve as a sacrifice should the community require it—people like this often become heroes without even realizing that they are speaking or acting heroically, but simply by showing, “This is how I am!” This is the most appealing characteristic of these simple souls; they possess the wisdom of the people, and with this they compel even their enemies to hear them out.

God sent precisely such a man of the people to the trial, someone without pretentions or disguises. He plays his role absolutely naturally and so honestly, so conscientiously, so faithfully to reality, that over these two days he became a central figure. His name has probably remained in your memory from the telegrams: Feldberg! Leyzer Feldberg!

He is a tall man of sixty-eight years. He has a pale face from weeks of sitting under arrest, and several welts on his bare head. He is hard of hearing, and for this reason his entire figure, especially his face, appears constantly tense and strained. He began to draw attention from the very first day. His entire appearance seemed to cry out that a country where this old man could sit under arrest for assaulting and beating innocent peasants is without a doubt under the rule of arbitrariness, anarchy, lawlessness, disorder, and chaos. As soon as he answered the first formal questions from the chairman of the court, one could sense in this man a special inner certainty, a special purity and strength of conscience. He stepped up to the courtroom lectern with a calm intensity and answered—and his answers had to be believed! On the second day of the trial, he became unwell and had to be excused from the courtroom. Today, however, on the fourth day of the trial, he is being questioned.

This questioning has brought us honour and pride. This sixty-eight-year-old Jewish man declares openly, proudly, courageously, loudly, nearly shouting, that if he had at that moment had a weapon, he would have shot it. He walks right up close to the judge and shouts straight into his face: “Even if you, Your Honour, were to harm me, I would still defend myself!”

This makes a profound impression. More interesting, provocative, and powerful, however, is what he goes on to tell. He describes, almost poetically, how he belongs to one union—the union of the patriarch Abraham! The children of this union stood at the base of Mount Sinai and were the first to hear God’s voice, which commanded: thou shalt not murder, thou shalt not steal! These commandments of God remain this union’s holiest values to this day. This is the introduction that allows him to conclude that the Jews of Pshitik, children of Abraham, did not bother anyone and were happy when they were left to work and live in peace. “If only there were no knives and no clubs, the town would have been peaceful and calm,” Feldberg repeats several times. With a calm but deeply moving voice, he describes how they began to put the knives and clubs to work, how they even beat peasants who dared go up to a Jew’s street stall, how they transformed the town into a hell and the market days into days of anguish and catastrophe.

Jews ran to the local authorities and the authorities in Radom. He describes bluntly how the town hall received the Jewish delegation in which he took part, and how the district administrator cynically reassured the Jews that “nobody has been killed yet, after all.” In simple words, he describes how they threw the Jewish shoemaker Palant into the river, and how the Jewish delegations demanded protection and pleaded to be saved from murder, but the administrator cracked jokes and claimed that they were just going for the Jews’ pockets. “No,” old Leyzer Feldberg cries out in the courtroom, “they are going for our heads, not our pockets!” If they leave our heads intact, the gentiles will continue buying from us!

It is impossible to convey the full speech of this courageous man. He is always on cue. He says, “To me, a good priest is better than a bad rabbi.” This makes an impression because people can sense the truth of his words.

The following day, however, was even more interesting. Only then did the old man describe how he survived the Pshitik tragedy, which is the tragedy of more than three million Jews. He arrives at the courthouse paler, weaker, more exhausted. People can tell from his face that the old man has slept poorly and that something is tormenting him. He stands up right at the beginning of the session and declares that he has something else to add to what he had said yesterday. Lying on the hard bench in prison, he remembered things he had forgotten to say. The old man then tells in exhaustive detail how they threw the Jewish man Palant into the river, and how he had told the district administrator that they had killed a Jew. At that moment, the chairman, the prosecutor, and the antisemitic lawyer Kowalski exclaim, “There were no Jews killed!” Old Leyzer gazes around with a pair of large, bulging eyes and replies, “But they murdered him!” He says these words very quietly, because the assertion of the aforementioned three apparently hit him hard, but in his gaze is everything: astonishment and contempt.

Pale and agitated, he sits down on the defendants’ bench. They question several Christian witnesses. The Christian witness Rogulski, the owner of the house in which the Minkovskis were so bestially murdered, enters. This Rogulski remains absolutely calm as he describes how, when he went into the Minkovskis’ room, he found the husband already dead and the wife still dying. When the chairman asks whether he knows the murderers, he replies, “No.” At that moment, however, old Feldberg jumps up, runs over to the judges’ table and cries out, “I can’t take it anymore! I can’t take it anymore!” Pointing out Rogulski, he shouts even louder, “It’s him; he killed them! He’s the murderer!”

Feldberg falls over; several of the accused weep. A recess is called. Feldberg is taken to the hospital.

This scene will remain in the memory of everyone sitting in the courtroom. The antisemitic lawyers, one of whom is the grandchild of a converted Jew, the famous historian Kraushar, can go ahead and smile into their bristly, pure-Polish moustaches; the antisemitic correspondents can go ahead and gnash their teeth as they spread the words of every brutish witness while suppressing the most important moments in the courtroom. Nobody will break free of the influence of Leyzer Feldberg, that man of the people whose every word, whose every movement radiates the wisdom and truth of the folk.

24 June 1936

Jewish and non-Jewish witnesses

One could write a mountain of text about the Pshitik trial. Every day, every hour there are surprises and characteristic qualities. Like in a film, picture after picture flies before one’s eyes: witnesses, Jewish and non-Jewish, old gentile and Jewish women, old Jewish and gentile men, young gentile men from the country and small-town ones with combed hair and neckties. An entire gallery of highly interesting, often captivating types, a genuine laboratory or observatory, an observation point for artists as well as sociologists, for those who study the evolution of human society.

One sees here how the village creates its inhabitants, and how the town whittles away at their exterior somewhat, removing their natural simplicity and rustic naïveté, greasing them with small-town pomade, teaching them to look at a newspaper or book, awakening within them appetites and desires, making them crueller and their souls more sinister, with greater cynicism and sharper teeth. The small-town antisemite can thus lie more easily and is no longer so afraid of being lashed in the world to come or penalized in this one, since he is more convinced than the rural antisemite of his party’s imminent victory. It is for this reason that he is more insolent. He acts as though he already has half a win in his pocket, or even more. He feels like he is the judges’ and prosecutors’ future boss and has almost no respect for them whatsoever.

Observing these witnesses with their small-town neckties, one is inadvertently reminded of the trial in Berlin for the pogrom on Kurfürstendamm.39 Of course, a Berlin hooligan looks entirely different than one from Pshitik, but there is one immense similarity that astounds the observer: the same insolence, built on the secure belief that any minute now, the whip will be in their hand as they assume power. There is a particular cynicism crying out from this insolence, but one must admit that it makes an impression, influencing in particular the judges and the prosecutor. Here in Radom, just like in Berlin, these witnesses, who really ought to be sitting among the accused, speak loudly, imperiously, in a commanding voice.

In our first report about the Pshitik trial, we already drew some comparisons between the Jewish and non-Jewish witnesses. At that point, however, we saw a large crowd of several hundred non-Jews and nearly a hundred Jews. Now we see them one at a time, and only here does it become so clear who is the beater and who the beaten that even the wildly antisemitic lawyers often lose their courage, and when they do dig in their heels and try insistently to twist things so that the Jews were beating and the peasants running away, they fail miserably.

Let us consider another couple of scenes of testimonies from witnesses on both sides.

There were a couple of days when the Jewish witnesses revealed a little corner of that bloody Monday, a date that will be remembered in Jewish history. The corner is small because the witnesses are still living in Pshitik for the time being, although it is unlikely they will hold out there much longer. They remain immobilized in Pshitik and are afraid to identify the perpetrators. They thus pretend to be blind and ignorant so as to avoid provoking the ferocious enemy.

Here stands Khaye Fridman. During the pogrom, she was holding a small child in her arms. She pleaded with the hooligans not to harm the child, and they did her that favour by directing all of their blows against her. The chairman asks her to approach the defendants’ bench and identify the perpetrators. She excuses herself, saying that the blows to her eyes had caused her to see poorly, and she does not want to assume the responsibility of identifying people.

Here stands Gedalye Hempel. They cut up his eye, fractured his rib, and caused many wounds all over his body. He was hospitalized for several days, and to this day he has still not recovered and surely never will. One can tell from his face that not only his body, but also his soul has been thoroughly beaten. It is not actually necessary to lose a foot or a hand, to become a cripple, an invalid. From twenty blows to the sides and a couple of good strikes to the head and eyes, one loses something that can be more than a foot. This witness, nervous and uncertain, is similarly afraid to approach the defendants’ bench and clearly identify the hooligans.

In private, they say openly that they know the hooligans, but they are afraid of retribution.

An elderly Jewish woman comes in, the mother of the accused Borenshteyn. Every forty-five- or fifty-year-old Jewish woman from Pshitik looks like she is sixty or sixty-five: a wrinkled, worn-out face, sunken eyes, and a terribly thin body. They are all grandmothers. She speaks quietly and calmly, but everyone is shaken. She paints a picture of how she went up to the attic with eight children and a six-year-old grandchild, how they all recited the vidui {final confession} in preparation for death, how her grandchild asked her to recite it with him. During her testimony, a scene plays out that repeats often in the courtroom. One of the judges, an avowed antisemite by the name of Plewako, asks the old woman Borenshteyn whether she has a son who is a Communist. She replies that she had a son who was a Communist, but he died in prison. She does not even let out a moan, but people can sense the bleeding of this mother’s heart. An antisemitic lawyer jumps up and asks whether her accused son is also a Communist. The accused Borenshteyn jumps up and confirms that he has had a shekel40 since 1917.

The Endek lawyers strive to prove that all Jews are Communists, and that the most terrifying Communists from Pshitik are those fourteen people sitting on the defendants’ bench. It must be recognized that as soon as the word “Communism” is mentioned, it is as though the large-horned devil himself has strolled into the courtroom and cast everyone into a state of panic. Everyone somehow says this word in a special tone. The judges, prosecutor, and antisemitic lawyers all say it as though it were the most hideous crime in the world, as though it were the lowest possible degree of moral decline. This has a particular undertone: only Jews could undergo such moral decline as to become Communists. The Jewish defendants are terrified. They are not, in fact, Communists, but they sense that the smallest inkling, the slightest suspicion of Communism would be enough to ruin them. After all, this suspicion can blind even the most honest judge.

A Jewish man with a white beard walks in, barely standing on his own two feet. He had been in the hospital for weeks. He had pleaded for death to come. The angel of death was indeed standing by his bed, but departed at the last minute. He was not destined to be redeemed from life in exile. The hooligans beat him over the head with crowbars, not stopping until he lost consciousness and they believed him dead. Not until several hours later in a hospital bed did he recover, or rather, begin to feel his superhuman agony, from which only death can save him. What can this Leybush Toyber tell? He is still trembling and terrified, and they cannot get anything out of him. Nevertheless, this half-deaf old man was the living witness to who really started a pogrom, and who is capable of being wild, murderous, and bestial.

No matter how bestial, how murderous, and how cruel a person is capable of being, he is nevertheless still a person. Even these forty-four pogromists, who behave like bridegrooms, like heroes, like great fighters for the people; even these antisemitic lawyers, these genuine wild beasts, these truly wicked demons, who apparently obtained a university education for the sole purpose of making the beast within them quicker-witted, more sadistic, and cynical—they are all created in God’s image and have within them a human spark.

It was sufficient to seat the witness Feyge Shukh before the judge. She is unable to stand, this mother who bore the blows of ten hooligans to prevent a club or stone from striking any of her seven children. This broken woman restored human form to these wild beasts. This Feyge Shukh, a woman of iron just half a year ago, repeatedly loses consciousness. How could you not, seeing your assailants strolling freely through the corridor? How could you stand it, when your assailants are called to testify that the other assailants, the ones sitting on the defendants’ bench, are actually innocent little lambs who came to the market to look for a bride or for a relative’s grave at the cemetery? She is thus unable to stand, and they allow her to sit before the court. That is enough. Does she need to say anything? Does she need to speak? Her entire broken, wounded body cries out that, in Pshitik, beasts went on a rampage, murdering out of a love for murder, out of bloodthirstiness, out of the thrill of beating the heads of weak people with stones. And yet she tells how she remained in the house to give all seven children time to hide in the attic. At first, they threw stones through the window. Then, they broke into the house and began beating her, a mother of seven children.

She was lying on the ground more dead than alive as the hooligans were about to leave, remarking cheerfully that Feyge was surely in the next world by now. Unfortunately, her body trembled, and the hooligans turned around and resumed the beating: “She’s a strong one, damn it,” one of them grumbled. If one is destined to live, one lives, and Feyge Shukh picked herself up and barely managed to crawl over to her Christian neighbour, a woman who had lived right across the street for decades. She begged her to let her stay for a while, but the neighbour drove her out. At this point, Feyge bursts into tears. Sure, hooligans are wild, that’s natural, but for her long time neighbour Kasia to behave so bestially, that is too much to bear! She speaks, this shard. This remnant of a person has courage; she has a desire to speak and identify her assailants. And she identifies them: there are three of them, the leaders, the ones who beat her with crowbars.

The prosecutor proposes that they place the three men she identified among the remaining eight. During this operation, she loses consciousness. However, she recovers and again identifies the assailants. Inside this weak body, a vigilant soul is still alive; inside this battered, wounded head, a healthy brain is still working, and she recognizes everything, and she wants to speak and to identify. Yes, she is made of iron, just as the doctor told her as she was brought to the hospital in Radom.

It is not her body that is made of iron, but her soul, her spirit. The old Jewish spirit, forged from true Jewish belief, from Jewish faith and Jewish steadfastness. There is nothing new under the sun! There is nothing new in the world. Pshitik is not the first hell on earth, and the shattered Feyge from Pshitik is not the first Jewish victim. Worse things have already been seen: burnings at the stake, hangings, mass murders, hundreds of communities destroyed. Hundreds of thousands expelled and tortured. Feyge from Pshitik finds herself in very good company. She does not lose confidence. Feyge from Pshitik is sister to millions of brothers and sisters all over the world, and she does not feel lost during the Radom trial. It has all happened before, and much more is yet to come, and Feyge’s faith will never be broken or extinguished.

It is hard to describe the orphan witnesses. It is even written in the Talmud that orphans cannot have mercy. It is only natural. I have seen Jewish orphans in orphanages, and pogrom orphans are not news to me. I have seen them in Kishinev, Bialystok, Odessa, Kiev, and many other cities. I have seen grown-up orphans and little children. But I have never seen such calm, reassured orphans as the children of the murdered Minkovskis. In the eyes of pogrom orphans, one could always see the clinging terror, the fear that seized and entrapped the child’s soul. The orphans from the Pshitik pogrom give the impression that they do not yet know that dying means being lost forever, never again seeing their mother’s eyes, never again hearing their father’s voice. They are still waiting for a miracle, for their parents to return and bring them back to their own warm home. Their being true orphans could only be sensed in the courtroom. Perhaps they too only felt the true meaning of being orphans in the court. The murderers standing before their eyes must have conjured up images of their parents, and the axe, and the blood, and the screams, and the writhing and convulsing in a pool of blood, and the lying under the bed, and the watching and seeing them hacking into people with an axe, into a father, into a mother.

And so it was. The six-year-old orphan was thus unable to even raise his eyes to look at the murderers. The gentle words of the chairman and the requests of the Jewish lawyers are of no use. He is unable to look at the murderers, even to identify them. That is beyond what a six-year-old child can bear.

Meanwhile, the twelve-year-old orphan, Hershl, conducts himself truly heroically. He holds his big, dark eyes open, looking at all of them honestly and bravely: at the judges, lawyers, and accused. And he identifies the four murderers. He identifies them several times, in various poses and arrangements, mixed in with many others. He recognizes them so clearly and straightforwardly that even the evilest lawyers cannot twist their way out of his hands. He answers all of the questions concisely and clearly, not in a rehearsed manner, but from his heart, from his memory, from his sharp eye that probably captured for eternity both the wild faces of the murders and the horrifically bloodied faces of his parents. His testimony astounded everyone and will undoubtedly play a major role in rendering the verdict.

We cannot elaborate on all of the Jewish witnesses, but one thing was clear. Almost all of them came with marks on their bodies. Some were deafened or blinded by the blows, one had seventeen wounds and others even more, some had wounds in their souls and others had holes in their skulls. Almost all had been beaten, torn apart, ruined physically, mentally, and materially, with permanent traces that will last for generations.

1 July 1936