Introduction

Robert Brym

© 2024 Robert Brym, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0342.00

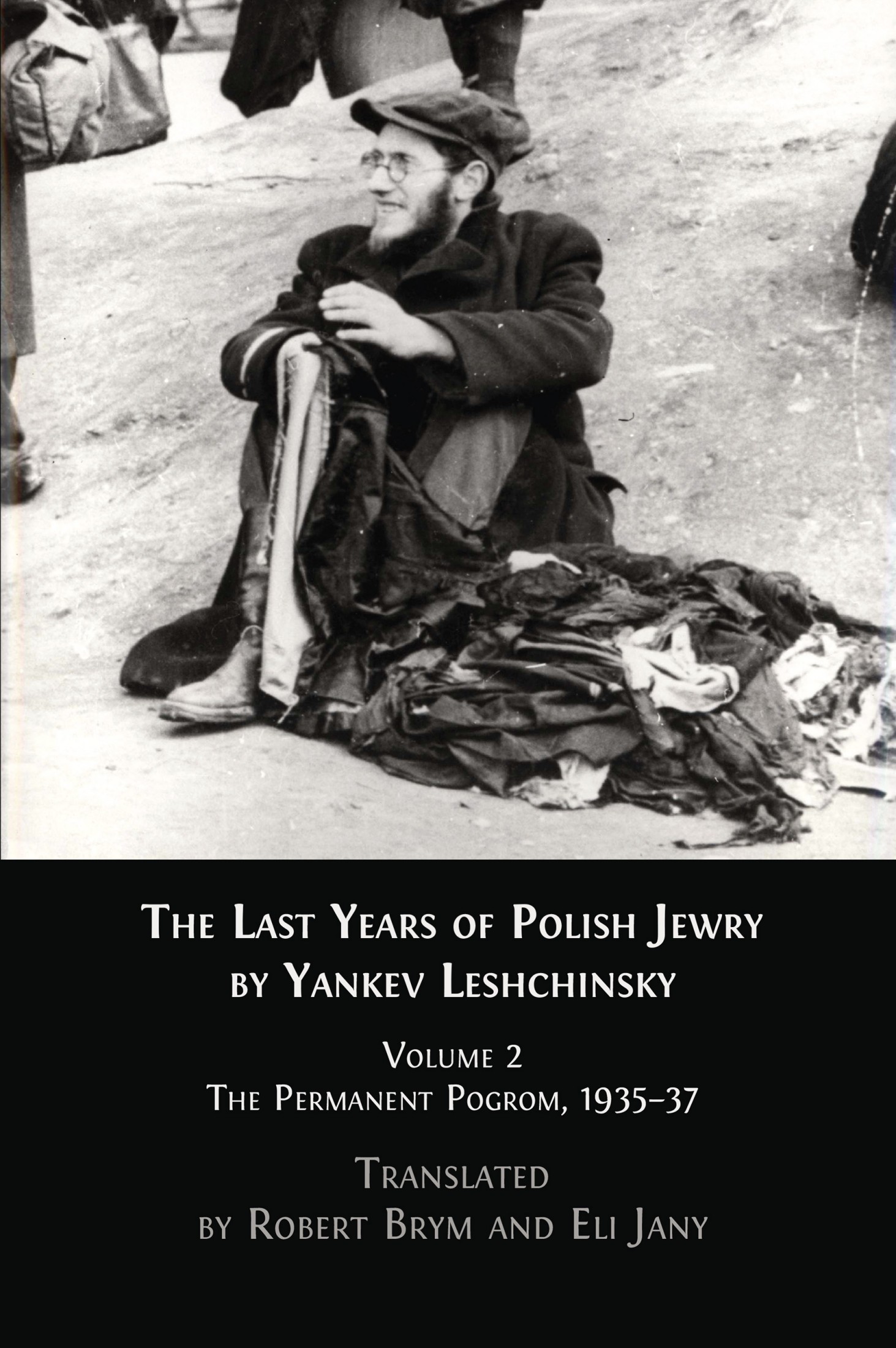

On the night of 22 June 1936, about seventy right-wing nationalists entered Mishlenitse (Myślenice), a small town south of Krakow, Poland. They cut the town’s telephone cables, commandeered rifles from the local police station, and then turned to their main task: attacking Jewish-owned crockery, grocery, leather goods, and haberdashery shops. They broke windows, destroyed merchandise, and set fires, including one at the local synagogue. Interpersonal violence was not their main goal; they killed no one and assaulted four Jews. Rather, the attackers were seeking to put into practice ideas expressed in a document issued by the Krakow branch of the Narodowa Demokracja party. It urged a “fight against Jewish capitalism… [and] for returning to the Polish nation one million trade, craft and industrial workshops, which constitute today the foundation of Jewish power, capable of providing work and bread to all Poles who do not have them today.”1 Twenty months later, in the only verdict pertaining to the Mishlenitse ethnic riot, its leader was found guilty on the sole charge of seizing arms from the police station. He was sentenced to a prison term of three-and-a-half-years, later commuted to one year (Fig. 1).

In the 1930s, Poles referred to incidents like the one in Mishlenitse as “excesses.” In contrast, Jews call such events “pogroms.” This volume, which collects Yankev Leshchinsky’s writings on various aspects of popular and official antisemitism in Poland from 1935 to 1937, focuses on anti-Jewish pogroms and Jewish responses to them.2

Fig. 1 The Mishlenitse pogromists on the way to trial, May 1937. Polish National Digital Archives, public domain, https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/wyszukiwarka

The noun “pogrom” derives from the Russian verb pogromit’ (погромить), “to destroy” or “to massacre.” Recently surveying the history of anti-Jewish pogroms in Eastern Europe from 1881 to 1946, Eugene M. Avrutin and Elissa Bemporad wrote:

[T]he term “pogrom” characterizes mob attacks or deadly ethnic riots that were usually, but not always, carried out in urban settings….[P]ogrom refers to a constellation of violent events, ranging from spontaneous ethnic riots (resulting in bodily injury, looting or destruction of property, and death) to genocidal violence (the deliberate killing of an a entire group of people).3

This definition applies reasonably well to as many as twelve interwar anti-Jewish riots in Poland that are mentioned in the literature. Apart from the events at Mishlenitse, they include pogroms that took place between June 1935 and August 1937 in Grodno, Adzhival (Odrzywoł), Pshitik (Przytyk), Minsk-Mazovyetsk (Mińsk Mazowiecki), Brisk (Brzesc), Dzhedzhgov (Dzierzgowo), Tshenstokhov (Częstochowa), Kelts (Kielce), Warsaw, Vilna (Wilno; Vilnius), and Lomzhe (Łomża) (see Fig. 2). Such pogroms, concentrated in towns and cities running along a diagonal from southwestern to northeastern Poland, resulted in “dozens of casualties” according to Anna Cichopek-Gajraj and Glenn Dynner. In contrast—and testifying to the question of what constitutes a pogrom as much as the difficulty of discovering precise numbers—Antony Polonsky writes that fourteen Jews were killed and “as many as 2,000” injured.4

Fig. 2 Poland, August 1939. The locations of twelve anti-Jewish riots that took place between 1935 and 1937 and are referred to as pogroms in the literature. Modified from Wikimedia, CC BY-SA, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Poland_August_1939.png

It is evident from the long first essay in this collection that Leshchinsky would have considered these counts of the murdered and injured too low—and Avrutin and Bemporad’s definition of “pogrom” too narrow. For one thing, the counts apparently do not take into account people who were seriously injured during a pogrom but died from their injuries long after the rioting ended. Leshchinsky mentions eight known cases: Borekh Zilberberg, one Lutenberg, and Khaim Perlis, who died between two weeks and four months after the Brisk pogrom; Gedalye, Feyge, and Yudl Tishler, who succumbed to their injuries up to six months after the Pshitik pogrom; Khaim Shimenovski, who passed away a year after the Minsk-Mazovyetsk pogrom; and Leyb Shapiro, who died eighteen months after injuries he sustained in the Grodno pogrom.

More importantly, not just in an arithmetic but in a sociological sense, most acts of violence that caused deaths and injuries are not included in conventional tallies of pogrom-related deaths and injuries. From the incidents that historians of interwar Poland commonly identify as pogroms, one is likely to learn that they each involved a few score to perhaps a thousand attackers. Historians do not qualify incidents involving fewer assailants as pogroms. Thus, they do not recognize as a pogrom ten young men attacking Jews strolling or sitting on benches in Warsaw’s Saxon Garden, chasing and beating them with wooden sticks, throwing them into the park’s pond, and toppling carriages with small Jewish children in them, even though in 1937 similar attacks persisted for weeks on end and resulted in many injuries, some serious. And when just one Pole from a peasant family noticed a sixty-two-year-old Jew passing by his house, ran outside, unprovoked, with an axe, split open the Jew’s head, and left him dying in a pool of blood, it is certainly not counted as a pogrom in the conventional definition of the term. Yet thousands of Poles, unprovoked, physically attacked Jews with whom they were unacquainted between 1935 and 1937.

If, on the other hand, one surveys and adds up the carnage, as Leshchinsky did by systematically poring over contemporary Jewish press reports, a picture emerges not of twelve discrete events, each characterized by short time spans of a day or two and participants typically numbering in the scores or hundreds, but of a single sustained collective event stretching over nearly three years and involving many discrete bursts of property destruction and interpersonal violence, varying widely in duration, intensity, and level of participation. Specifically, the nationwide collective event targeted Jews in more than 150 Polish towns for beatings, stabbings, bombings, looting, acts of arson, and the vandalization of business and residential property. It was supported above all by the Narodowa Demokracja party (Endecja for short), which mobilized activists from all Polish social classes. Understanding how deeply entrenched antisemitism was in Poland, the Endeks, as party members were commonly known, intensified their antisemitism partly as a means of outbidding other parties for popular support.5

Leshchinsky calls this sociological phenomenon a “permanent pogrom.”6 He recognizes that the number of murdered Jews in the Polish pogroms of 1935–37 was small compared to the more than 100,000 killed in Ukrainian pogroms during the Russian civil war (1918–21).7 However, Leshchinsky’s list of violent anti-Jewish actions allows him to make the credible claim that the permanent pogrom in Poland killed “hundreds” and wounded “as many as 10,000” Jews during the period under consideration (pp. 23, 61, below). He also believed that his numbers are underestimates:

[T]he material we will use in our work… consists only of newspaper articles that have gone through the highly stringent Polish censor, so the articles are like official acknowledgements. In the editorial archives of all Jewish newspapers there are mountains of material that could not be made public due to censorship….There can be no doubt they were not allowed to be made public because they reflect actual life too clearly. However, we have not used these archival materials (p. 23, below).

In terms of the permanent pogrom’s effects, Leshchinsky writes: “It paralyzes the Jewish masses, disorganizes Jewish society, wildly tears livelihoods from Jewish hands, shifting the full attention of the Jewish individual and the Jewish community to fleeing, emigrating, saving oneself; weakening in this way the courage to struggle for the jobs that have been saved.” Nonetheless, “[t]he dry numbers derived from the list of the wounded in cities where there were attacks…do not convey even in the palest form and by the weakest measure the truly tragic situation that is signified by the words ‘permanent pogrom’” (pp. 57, 58, below). The chief emotional consequence of the permanent pogrom was the normalization of fear. Knowing they could be attacked at any time and in any place, most of Poland’s 3.1 million Jews walked with cowed heads and tensed shoulders, always ready to bolt in response to the slightest stir.

Yet many refused to bolt. In Warsaw, Lodz, Bialystok, and elsewhere, organized groups of Jewish workers defended Jews from attack, went on the offensive, and occasionally took pre-emptive action. Often, “[a]s soon as a commotion breaks out in the street…youth, workers, porters, and athletes run toward the commotion to defend their battered brothers, to teach the hooligans a lesson and to take revenge on the pogromists”.8

In 1936, the trial took place of forty-three Poles and fourteen Jews accused of violent crimes during the Pshitik pogrom. Thirty-nine Poles, including the murderers of Khaye and Yosef Minkovski, a Jewish couple, were sentenced to light prison terms ranging from one-half to one year. The Jews’ entirely credible claim that they were acting in self-defence was rejected by the court. Ten Jews were sentenced to six months in prison and one received a sentence of eight years. Poland’s Jewish community erupted in fury. Jewish workers’ parties, supported by the Polish Socialist Party, organized a highly effective nationwide strike of Jews. According to Leshchinsky, “[a] quarter of a million Jewish shops and market stalls and 200,000 Jewish workshops closed in unison across all of Poland” (p. 136, below).

Fig. 3 Mourners follow a horse-drawn hearse carrying Khaya Minkovski, murdered in the 1936 pogrom in Pshitik. ©Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, http://polishjews.yivoarchives.org/archive/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=4526.

The permanent pogrom did not spare universities and high schools, where armed attacks on Jewish students were widespread. In 1935, Jews had begun to be assigned segregated seating at Lvov (Lwów) Polytechnic.9 Jewish students took to standing in protest during their classes. By 1937 the spread of so-called ghetto benches caused Polish Jewry to protest en masse.10 On 19 October, a six-hour closure of all Jewish schools, shops, workshops, factories, banks, cafes, and restaurants in Warsaw took place. It was followed by a “Week for Jewish Students” during which Jews boycotted places of entertainment and refrained from all non-essential expenditures.

Such efforts notwithstanding, Jewish resistance was on the whole piecemeal and ineffective. Leshchinsky notes that some religious Jews prayed and fasted in the hope that God would answer their entreaties. Liberal Jews appealed to the government for more repressive measures against antisemitic rioters. However, for all practical purposes, the government’s response was similar to that of the Almighty. The permanent pogrom dragged on. The police continued to arrest many fewer Poles for attacking Jews than they arrested Jews for defending themselves. For their part, the disparate Jewish parties and ideological currents were unable and unwilling to forge a united and steadfast opposition front.

Leshchinsky recognized that the fundamental cause of Poland’s permanent pogrom was “economic.” Specifically, the industrialization of Poland was incompatible with the ethnic composition of the country’s class structure.

Industrialization requires what sociologists call “structural mobility.” Agricultural jobs must be turned into jobs for artisans, merchants, industrialists, professionals, and industrial and white-collar workers. However, in Poland, non-Jewish peasants comprised 60% of the Polish labour force according to the 1931 census. Jews, on the other hand, were considerably overrepresented as professionals, greatly overrepresented as artisans, and vastly overrepresented as merchants—precisely the types of jobs Poles sought in increasing number as their undeveloped agricultural system failed to sustain them.11 Pressured by the forces of capitalist development, the country’s extraordinarily high level of ethnic stratification increased the likelihood that Poles would seek to remove Jews from various positions in the ethnic stratification system, as the Endek document quoted in this Introduction’s first paragraph urged. As the depression deepened, the likelihood increased.

If these structural circumstances set the stage for interethnic violence, largely political circumstances affected the timing, scope, and severity of violence during the permanent pogrom: the growing influence of Nazi Germany on Polish society, chillingly pictured in Fig. 1, above; the increasing hostility of Poland’s Catholic Church toward Jews; and the death of Joseph Pilsudki {Józef Piłsudski}, Poland’s former Prime Minister, on 12 May 1935.12

Pilsudski remained a dominant political figure even after he left office in 1928, balancing authoritarian-centrist and totalitarian-nationalist elements in the ruling Sanacja (“healing”) party and thereby keeping a lid on interethnic conflict and its violent expression. After his passing, Sanacja split into warring factions. Members of its totalitarian-nationalist wing believed that by relaxing sanctions against antisemitic violence the government could increase its appeal to young totalitarian-nationalists and thus limit the growth of parties to its right, including but not restricted to Endecja. Their words and actions helped to unleash the permanent pogrom.

In 1937, after nearly three years of bloodshed and destruction, another change in political conditions began to rein in the permanent pogrom. Even before the 1938 Nazi Anschluss of Austria, the attention of Polish politicians was deflected from internal ethnic conflict and drawn toward foreign policy and national security issues. Moreover, the Polish government came to view anti-Jewish violence as ineffective if not counterproductive. The opinion grew that replacing Jewish merchants and artisans with Poles would not rid the country of Jews and could not in any case take place on a sufficiently large scale to solve the structural mobility problem since Jews formed just 10% of the country’s population. Instead, the government decided that the mass emigration of Jews was required.

To that end, the government now established close contact with Zionist organizations to facilitate the removal of Jews from Polish society. It lobbied the League of Nations in support of Jewish emigration to Palestine, Madagascar, or anywhere else. Little came of this effort. Britain was reluctant to permit the mass migration of Jews to Palestine for fear of further angering its Arab majority. The depression and the spread of fascism ensured that no country was much interested in immigrants, let alone Jewish immigrants. In 1937, only about 9,000 Jews—less than 0.3% of Poland’s Jewish community—managed to leave the country.

And so it transpired that Poland’s Jews were trapped in a fate immeasurably worse than the permanent pogrom.