10. Reading the Rosetta Stone

© 2023 Andrew Robinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0344.10

You tell me that I shall astonish the world if I make out the inscription. I think it on the contrary astonishing that it should not have been made out already, and that I should find the task so difficult as it appears to be.

Young, letter to Hudson Gurney, 1814 [278]

Young became hooked on the scripts and languages of ancient Egypt in 1814, the year he began to decipher the Rosetta Stone. He continued to study them with variable intensity for the rest of his life, literally until his dying day. The challenge of being the first modern to read the writing of what appeared then to be the oldest civilisation in the world—far older than the classical civilisation of his beloved Greeks—was irresistible to a man who was as equally gifted in languages, ancient and contemporary, as he was in science. He himself in 1823 described his obsession as being driven by ‘an attempt to unveil the mystery, in which Egyptian literature has been involved for nearly twenty centuries’.[279] His epitaph in London’s Westminster Abbey states, accurately enough, that Young was the man who ‘first penetrated the obscurity which had veiled for ages the hieroglyphics of Egypt’[280]—even if it was Jean-François Champollion who in the end would enjoy the glory of being the first actually to read the hieroglyphs.

But before we delve into Young’s attempt, we need some historical background, a survey of earlier thinking of the kind in which Young himself specialised (for example, in his Natural Philosophy and his Consumptive Diseases). To decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs in the period 1814–1824 required Young and Champollion to sweep away centuries of erroneous thinking, dating back to classical antiquity, while building on a handful of genuine insights from various scholars.

The civilisation of the pharaohs had gone into eclipse some two thousand years earlier, when it was conquered by Alexander the Great and came under the Hellenistic rule of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Such was its legendary magnificence, however, that the Greeks and Romans, especially the Greeks, regarded ancient Egypt with a paradoxical mixture of reverence for its wisdom and antiquity and contempt for its ‘barbarism’. The very word hieroglyph derives from the Greek for ‘sacred carving’. Egyptian obelisks were taken to ancient Rome and became symbols of prestige; today, thirteen large obelisks stand in Rome, while only four remain in Egypt.

The classical authors generally credited Egypt with the invention of writing (though Pliny the Elder attributed it to the inventors of cuneiform). However, none of them could read the hieroglyphs in the way that they were able to read the Greek and Latin alphabet, even though hieroglyphic inscriptions continued to be written in Egypt as late as ad 394. They preferred to believe, as Diodorus Siculus wrote in the first century bc, that the Egyptian writing was ‘not built up from syllables to express the underlying meaning, but from the appearance of the things drawn and by their metaphorical meaning learned by heart.’[281] In other words, the hieroglyphs were conceptual or symbolic, not phonetic like their own alphabet. Thus, a hieroglyphic picture of a hawk represented anything that happened swiftly; a crocodile symbolised all that was evil.

By far the most important authority was an Egyptian magus named Horapollo (Horus Apollo) supposedly from Nilopolis in Upper Egypt. His treatise, Hieroglyphika, was probably composed in Greek, during the fourth century ad or later, and then sank from view until a manuscript was discovered on a Greek island in about 1419 and became known in Renaissance Italy. Published in 1505, the book was hugely influential: it went through thirty editions, one of them illustrated by Albrecht Dürer, and even remains in print.

Horapollo’s readings of the hieroglyphs were a combination of the (mainly) fictitious and the genuine. Young called them ‘puerile […] more like a collection of conceits and enigmas than an explanation of a real system of serious literature’.[282] For instance, according to the esteemed Hieroglyphika:

[W]hen they wish to indicate a sacred scribe, or a prophet, or an embalmer, or the spleen, or odour, or laughter, or sneezing, or rule, or judge, they draw a dog. A scribe, since he who wishes to become an accomplished scribe must study many things and must bark continually and be fierce and show favours to none, just like dogs. And a prophet, because the dog looks intently beyond all other beasts upon the images of the gods, like a prophet.[283]

… And so on. There are elements of truth in this: the jackal (‘dog’) hieroglyph writes the name of the god Anubis, who is the god of embalming, a smelly business (hence the meaning ‘odour’?); and a recumbent jackal writes the title of a special type of priest, the ‘master of secrets’, who would have been a sacred scribe and considered something of a prophet; while a striding jackal can also stand for an official, and hence perhaps for a judge. But consider Horapollo’s ‘What they mean by a vulture’:

When they mean a mother, or boundaries, or foreknowledge […] they draw a vulture. A mother, since there is no male in this species of animal. […] The vulture stands for sight since of all other animals the vulture has the keenest vision. […] It means boundaries, because when a war is about to break out, it limits the place in which the battle will occur, hovering over it for seven days. Foreknowledge, because of what has been said above [about sight] and because it looks forward to the amount of corpses which the slaughter will provide it for food.[284]

This was almost all fantasy, except for ‘mother’: the hieroglyph for mother is indeed a vulture.

The Arabs who occupied Egypt with the coming of Islam in the medieval period had a marginally more accurate understanding of the hieroglyphs because they at least believed that the signs were partly phonetic, not purely symbolic. (Their attribution of phonetic values was wrong, however.) But this belief did not pass from the Islamic world to the European. Instead, fuelled by Horapollo, the Renaissance revival of classical learning brought a revival of the Greek and Roman belief in the hieroglyphs as symbols of wisdom. The first of many scholars in the modern world to write a whole book on the subject was a Venetian, Pierius Valerianus. He published it in 1556, and illustrated it with delightfully fantastic ‘Renaissance’ hieroglyphs.

The most famous of these interpreters was the Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher. In the mid-seventeenth century, Kircher became Rome’s accepted pundit on ancient Egypt. But his voluminous writings took him far beyond ‘Egyptology’; ‘sometimes called the last Renaissance man’ (notes the Encyclopaedia Britannica[285]), and dubbed ‘the last man who knew everything’ in 2004 in an academic study[286], Kircher attempted to encompass the totality of human knowledge. The result was a mixture of folly and brilliance—with the former easily predominant—from which his reputation never recovered.

In 1666, Kircher was entrusted with the publication of a hieroglyphic inscription on an Egyptian obelisk in Rome’s Piazza della Minerva. This had been erected on the orders of Pope Alexander VII to a design by the sculptor Bernini (it stands to this day, mounted on a stone elephant, encapsulating the concept ‘wisdom supported by strength’). Kircher gave his reading of a cartouche—i.e., a small group of hieroglyphs in the inscription enclosed by an oval ring—as follows: ‘The protection of Osiris against the violence of Typho must be elicited according to the proper rites and ceremonies by sacrifices and by appeal to the tutelary Genii of the triple world in order to ensure the enjoyment of the prosperity customarily given by the Nile against the violence of the enemy Typho.’[287] Today’s accepted reading of this cartouche is simply the name of a pharaoh, Wahibre (Apries), of the twenty-sixth dynasty!

An ironic Young—who was also, let us not forget, a Quaker by upbringing, with a natural resistance to priestly authority and tradition—noted of Father Kircher: ‘according to his interpretation, which succeeded equally well, whether he happened to begin at the beginning, or at the end, of each of the lines, they all contain some mysterious doctrines of religion or of metaphysics.’[288] Mumbo-jumbo had a ready market in seventeenth-century Rome, just as it had in ancient Rome and, indeed, in our twenty-first-century world.

By contrast, Kircher genuinely assisted in the rescue of Coptic, the language of the last phase of ancient Egypt, by publishing the first Coptic grammar and vocabulary. The word Copt is derived from the Arabic qubti, which itself derives from Greek Aiguptos (Egypt). The Coptic script was invented around the end of the first century ad, and from the fourth to the tenth centuries Coptic flourished as a spoken language and as the official language of the Christian church in Egypt; after that it was replaced by Arabic, except in the church, and by the time of Kircher, the mid-seventeenth century, the language was headed for extinction (though it was still used in the liturgy). During the eighteenth century, however, several scholars acquired a knowledge of Coptic and its alphabet, which in its standard form consists of the 24 Greek letters plus six signs borrowed from the last stage of the script of ancient Egypt (the demotic script, which appears on the Rosetta Stone along with the hieroglyphic script, as we shall shortly see). This knowledge of Coptic would prove essential in the decipherment of the hieroglyphs in the nineteenth century.

Wrong-headed theories about the Egyptian script flourished throughout the Enlightenment period. For example, a Swedish diplomat, Count Palin, suggested in three publications that parts of the Old Testament were a Hebrew translation of an Egyptian text—which was a reasonable conjecture—but then Palin tried to reconstruct the Egyptian text by translating the Hebrew into Chinese. This was not quite as crazy as it sounds, given that both Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters have a strong conceptual and symbolic element; the very fact of the existence of the Chinese script, and also a particular structural link between the two scripts, would in fact offer an important clue in deciphering Egyptian in the more cautious hands of others. But Palin went way too far with his hieroglyphic extravaganza. As Young noted coolly:

[T]he peculiar nature of the Chinese characters […] has contributed very materially to assist us in tracing the gradual progress of the Egyptian symbols through their various forms; although the resemblance is certainly far less complete than has been supposed by Mr Palin, who tells us, that we have only to translate the Psalms of David into Chinese, and to write them in the ancient character of that language, in order to reproduce the Egyptian papyri, that are found with the mummies.[289]

The first ‘scientific’ step in the right direction came from an English clergyman. In 1740, William Warburton, the future bishop of Gloucester, suggested that all writing—hieroglyphs included—might have evolved from pictures, rather than by divine origin. A French admirer of Warburton, Abbé J. J. Barthélemy, then made a sensible guess in 1762 that obelisk cartouches might contain the names of kings or gods—ironically, on the basis of two false observations (one being that the hieroglyphs enclosed in the oval rings differed from all other hieroglyphs). Finally, near the end of the eighteenth century, a Danish scholar, Georg Zoëga, hazarded that some hieroglyphs might be, in some measure at least, what he called ‘notae phoneticae’[290], Latin for ‘phonetic signs’: representing sounds rather than concepts in the Egyptian language. The path toward decipherment was at last being cleared.

And now we have reached a turning point: the arrival of Napoleon’s invasion force in Egypt in 1798 and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone. The word cartouche, as applied to Egyptian hieroglyphs, dates from this fateful expedition. The oval rings enclosing groups of hieroglyphs, visible within inscriptions on temple walls and elsewhere in Egypt to any casual observer, reminded the French soldiers of the cartridges (cartouches in French) in their guns.

Fortunately, the military force was almost as interested in culture as in conquest. A party of French savants, including the celebrated mathematician Jean-Baptiste Fourier, accompanied the army and remained in Egypt for some three years. There were also many artists, chief of whom was Dominique Vivant Denon. Between 1809 and 1828, Denon and others illustrated the Description de l’Égypte, and the whole of Europe (especially a polymath like Young) was astonished by the marvels of the pharaohs. One of the French drawings shows the city of Thebes, with the columns of the temple of Luxor behind and highly inscribed obelisks in the foreground. The carved scenes depict the charge of chariot-borne archers under the command of Ramses II against the Hittites in the battle of Kadesh (c. 1275 bc). Napoleon’s army was so awestruck by this unheralded spectacle that, according to a witness, ‘it halted of itself and, by one spontaneous impulse, grounded its arms.’[291]

It was a demolition squad of French soldiers that stumbled across the Rosetta Stone in mid-July 1799, probably built into a very old wall in the village of Rashid (Rosetta), on a branch of the Nile just a few miles from the sea. Recognising its importance, the officer in charge had the stone moved immediately to Cairo. Copies were made and distributed to the scholars of Europe during 1800—a remarkably open-minded gesture considering the politics of the period. In 1801, the stone was shifted to Alexandria in an attempt to avoid its capture by British forces. But after a somewhat unseemly wrangle, it was eventually handed over, shipped to Britain, and displayed in the British Museum, where it has remained ever since, apart from an excursion to Paris in October 1972 for the 150th anniversary of Champollion’s decipherment.

According to one of the museum’s curators of Egyptian antiquities in 1999, Richard Parkinson, the Rosetta Stone ‘is the most popular single artifact in the British Museum’s collections’.[292] In his catalogue of the exhibition ‘Cracking Codes’, celebrating the bicentenary of the stone’s discovery, he writes: ‘Unfortunately, the stone’s iconic status seems to encourage visitors to reach out and touch the almost miraculous object.’[293] The familiar white characters on the black surface, polished by generations of visitors’ hands until the stone looked more like a printer’s lithographic stone (which it was actually used as, in the early nineteenth century) than a two-thousand-year-old monument, were mainly the result of chalk and carnauba wax rubbed into the surface by museum curators to increase visibility and aid preservation. In the 1990s, in time for the bicentenary, this policy was changed and the stone cleaned to reveal its natural colour. It is now seen to be a dark grey slab of igneous rock (not basalt, as formerly believed), which sparkles with feldspar and mica and has a pink vein through its top left-hand corner; it weighs some three quarters of a ton.

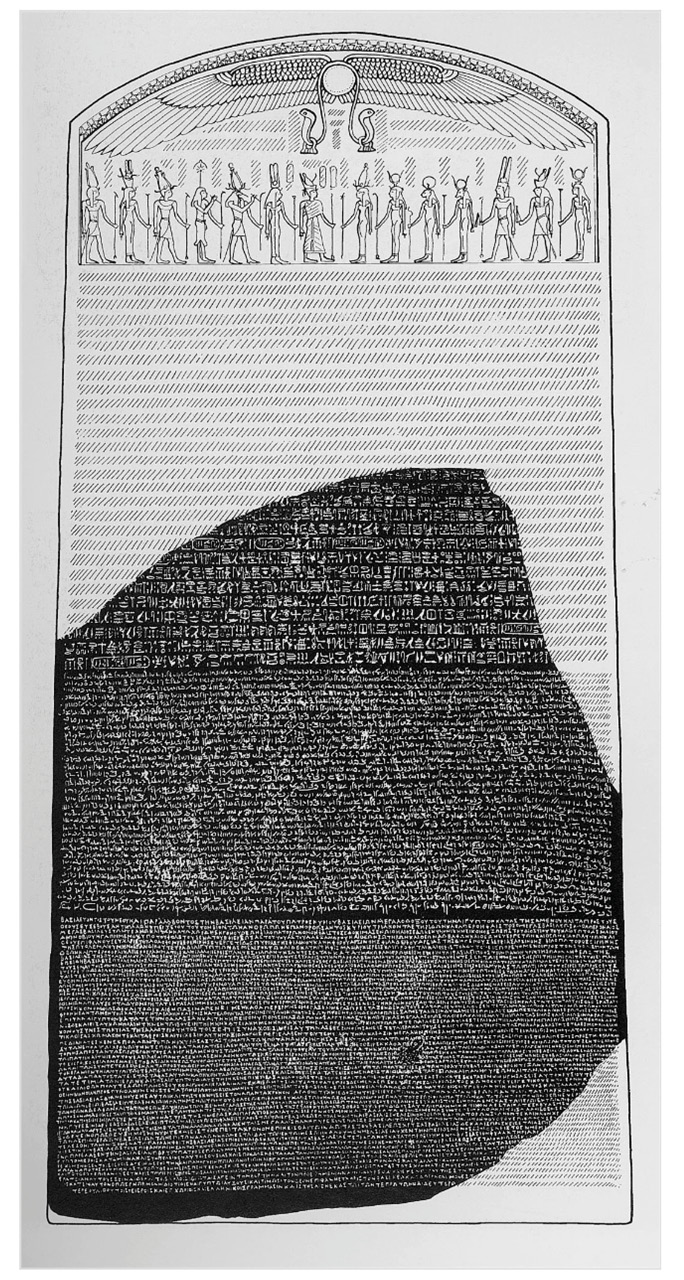

Even a quick glance reveals that the stone is broken—this fracture probably occurred before it came to Rosetta—both in the right-hand corner and, most obviously, at the top. So, the inscription is incomplete. Fortunately, there exist other similar complete inscriptions (found after the decipherment), including a near-copy inscribed fourteen years later and now in the Cairo Museum, so we can visualise the Rosetta Stone as it would originally have looked (see Figure 10.1).

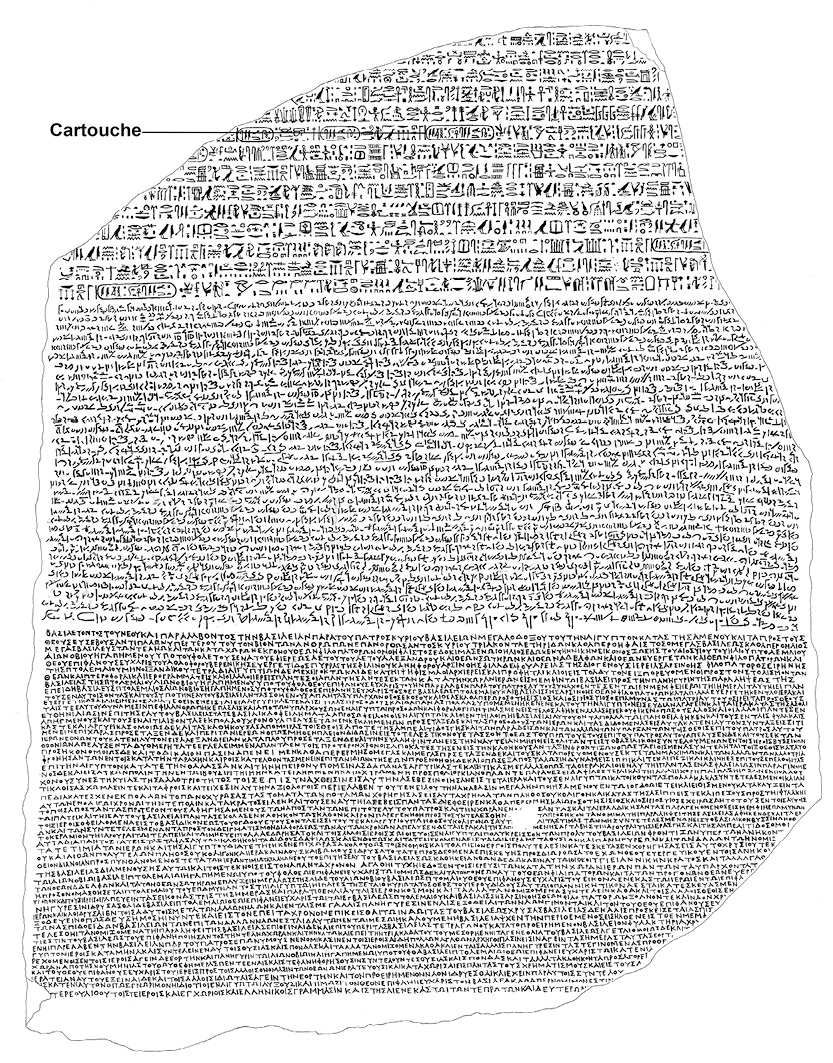

From the moment of discovery, it was clear that the inscription on the stone was written in three different scripts, the bottom one being the Greek alphabet and the top one—the most badly damaged—Egyptian hieroglyphs with visible cartouches, as shown in Figure 10.2. Sandwiched between them was a script about which little was known. It plainly did not resemble the Greek script, but it seemed to bear at least a passing resemblance to the hieroglyphic script above it, though without having any cartouches. Today we know this script as demotic, a development (c. 650 bc) from a cursive form of writing known as hieratic used in parallel with the hieroglyphic script from as early as 3000 bc (hieratic itself does not appear on the Rosetta Stone). The name derives from Greek demotikos, meaning ‘in common use’—in contrast to the sacred hieroglyphic, which was essentially a monumental script. The term demotic was first used by Champollion, who refused to import Young’s earlier coinage, enchorial, which Young had adopted from the description of the second script given in the Greek inscription: enchoria grammata, or ‘letters of the country’.

Fig. 10.1 The Rosetta Stone, as it would have looked before it was broken, drawn by C. Thorne and R. Parkinson. ©British Museum

The first step toward decipherment was obviously to translate the Greek inscription. This was done by, among others, Young’s classicist friend Richard Porson and, more accurately, by C. G. Heyne, the professor Young had known at Göttingen in the 1790s. It turned out to be a decree issued at Memphis, the principal city of ancient Egypt, by a general council of priests from every part of the kingdom assembled on the first anniversary of the coronation of the young Ptolemy V Epiphanes, king of all Egypt, on 27 March 196 bc. Greek was used because it was the language of court and government of the descendants of Ptolemy, Alexander’s general. The names Ptolemy, Alexander and Alexandria, among others, occurred in the Greek inscription.

Fig. 10.2 The Rosetta Stone inscription in hieroglyphic script (at top, with cartouche indicated), in demotic script (middle) and in Greek script (bottom). ©British Museum

Much of the decree is taken up, to put it bluntly, with the terms of a deal by which the priests agreed to give their support to the new king (who was only thirteen) in exchange for certain privileges. While this was of some interest to historians of ancient Egypt and its religion, the eye of would-be decipherers was caught by the very last sentence. It read: ‘This decree shall be inscribed on a stela of hard stone in sacred [i.e., hieroglyphic] and native [i.e., demotic] and Greek characters and set up in each of the first, second and third [-rank] temples beside the image of the ever-living king.’[294] In other words, the three inscriptions—hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek—were equivalent in meaning, though not necessarily ‘word for word’ translations of each other. This was how scholars first knew that the stone was a bilingual inscription: the kind most sought after by decipherers, a sort of Holy Grail of decipherment. The two languages were clearly Greek and (presumably) ancient Egyptian, the language of the priests, the latter being written in two different scripts—unless the ‘sacred’ and ‘native’ characters concealed two different languages, which seemed unlikely from the context. (In fact, as we now know, the Egyptian languages written in hieroglyphic and demotic are not identical, but they are closely related, like Latin and Renaissance Italian.)

Since the hieroglyphic section was so damaged, attention focused on the demotic. Two scholars, a distinguished French Orientalist in Paris, Sylvestre de Sacy (a future teacher of Champollion), and a Swedish diplomat, Johan Åkerblad, adopted similar techniques. They searched for a name, such as Ptolemy, by isolating repeated groups of demotic symbols located in roughly the same position as the eleven known occurrences of Ptolemy in the Greek inscription. Having found these groups, they noticed that the names in demotic seemed to be written alphabetically, as in the Greek inscription—that is, the demotic spelling of a name apparently contained more or less the same number of signs as the number of letters in its assumed Greek equivalent. By matching demotic sign with Greek letter, they were able to draw up a tentative alphabet of demotic signs. Certain other demotic words, such as ‘Greek’, ‘Egypt’, and ‘temple’, could now be identified using this demotic alphabet. It looked as though the entire demotic script might be alphabetic like the Greek inscription.

But in fact it was not, unluckily for de Sacy and Åkerblad. Young was sympathetic: ‘ [They] proceeded upon the erroneous, or, at least imperfect, evidence of the Greek authors, who have pretended to explain the different modes of writing among the ancient Egyptians, and who have asserted very distinctly that they employed, on many occasions, an alphabetical system, composed of 25 letters only.’[295] Taking their cue from classical authority, neither de Sacy nor Åkerblad could get rid of his preconception that the demotic inscription was written in an alphabetic script—as against the hieroglyphic inscription, which both scholars took to be wholly non-phonetic, its symbols expressing ideas, not sounds, along the lines of Horapollo. The apparent disparity in appearance between the hieroglyphic and demotic signs, and the suffocating weight of European tradition that Egyptian hieroglyphs were a conceptual or symbolic script, convinced them that the invisible principles of hieroglyphic and demotic were wholly different: the hieroglyphic had to be a conceptual/symbolic script, the demotic a phonetic/alphabetic script.

Except for one element. De Sacy deserves credit as the first to make an important suggestion: that the foreign names inside the hieroglyphic cartouches, which he naturally assumed were Ptolemy, Alexander and so on, were also spelt alphabetically, as in the demotic inscription. He was led to this by some information given to him by one of his pupils, a student of Chinese, in 1811. The Chinese script was at this time generally thought in Europe to be a primarily conceptual script like the hieroglyphs. Yet, as this student pointed out, foreign (i.e., non-Chinese) names, such as those of the Jesuit missionaries in China, had to be written phonetically in Chinese with a special sign to indicate that the Chinese characters were being reduced to a phonetic value without any conceptual value. (English-speakers, of course, indicate some foreign words in writing English with their own ‘special sign’—italicisation.) Were not Ptolemy, Alexander and so on, Greek names foreign to the Egyptian language, and might not the cartouche be the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic equivalent of the special sign in Chinese? But as for the rest of the hieroglyphs—all those not enclosed in cartouches—de Sacy was convinced they must undoubtedly be non-phonetic.

Enter Young in earnest, in early 1814. One might have expected him to have involved himself earlier with the Rosetta Stone, after it first went on display in London in 1802. However, at that time, he was totally occupied with his Royal Institution lectures, and after the mammoth task of publishing these in 1807, he devoted himself mainly to medicine. What finally triggered his active interest in the hieroglyphs, he tells us, was a review he wrote in 1813 of a massive work in German on the history of languages, Mithridates, oder Allgemeine Sprachkunde by Johann Christoph Adelung, which contained a note by the editor ‘in which he asserted that the unknown language of the stone of Rosetta, and of the bandages often found with the mummies, was capable of being analysed into an alphabet consisting of little more than thirty letters’.[296] When an English friend shortly afterwards returned from the East and showed Young some fragments of papyrus he had collected in Egypt, ‘my Egyptian researches began’. First he examined the papyri and reported on them to the Royal Society of Antiquaries in May 1814. Then he took a copy of the Rosetta Stone inscription away with him from Welbeck Street to the relative tranquillity of Worthing and spent the summer and autumn studying Egyptian, when he was not attending to his medical patients.

Apart from his exceptional scientific mind and his broad knowledge of languages, Young brought to the problem one other extremely valuable and relatively uncommon ability. He had trained himself to sift, compare, contrast, retain and reject large amounts of visual linguistic data in his mind. This ability has been a sine qua non for serious decipherers ever since Young and Champollion, as I have described in my two books on decipherment: Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts and The Man Who Deciphered Linear B: The Story of Michael Ventris. (Although outsiders to decipherment often like to imagine that in today’s world computers could be programmed to accomplish such sifting, in reality the human factor remains all-important—mainly because only a human being can spot that two signs which objectively look somewhat different are in fact variants of the same sign. We can all learn, from our knowledge of a language, how to recognise the same phrase written in two very different kinds of handwriting; but the same task is extremely difficult for computers.)

In his teens and twenties, as we know, Young was celebrated for his penmanship in classical Greek, leading to the publication of Calligraphia Graeca with John Hodgkin. From this he developed a minutely detailed grasp of the Greek letter forms. Then, in his mid-thirties, he was called upon to restore some Greek and Latin texts written on heavily damaged papyri dug up in the ruins of Herculaneum, the Roman town smothered along with Pompeii by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in ad 79. The fused mass of papyri had first to be unrolled without utterly destroying them, and then interpreted by classical scholars capable of guessing the meaning of illegible words and missing fragments. The unrolling required Young’s chemical skills (and those of Humphry Davy); the interpretation demanded his forensic knowledge of classical languages. In neither activity was Young at all satisfied with his results, but his experience with the Herculaneum papyri made him keenly aware of the relevance of his copying skills to the arcane arts of restoring ancient manuscripts. As he noted in his biography of Porson, ‘those who have not been in the habit of correcting mutilated passages of manuscripts, can form no estimate of the immense advantage that is obtained by the complete sifting of every letter which the mind involuntarily performs, while the hand is occupied in tracing it’.[297]

The mass of unpublished Egyptian research manuscripts by Young, now kept at the British Library, bear out this claim. Much of his success in this field would be due to his indefatigable copying—often exquisitely and occasionally in colour—of hieroglyphic and demotic inscriptions taken from different ancient manuscripts and carved inscriptions, and also from different parts of the same inscription; followed by the word-by-word comparisons that such copying made possible. By placing groups of Egyptian signs adjacent to each other, both on paper and in his memory, Young was in a position to see resemblances and patterns that would have gone unnoticed by other scholars. As his biographer Peacock wrote, after immersing himself in Young’s manuscripts, ‘It is impossible to form a just estimate either of the vast extent to which Dr Young had carried his hieroglyphical investigations, or of the real progress which he had made in them, without an inspection of these manuscripts.’[298] They also serve as a reminder, if one is still needed, of how unfounded are some modern claims that Young was a dilettante scholar.

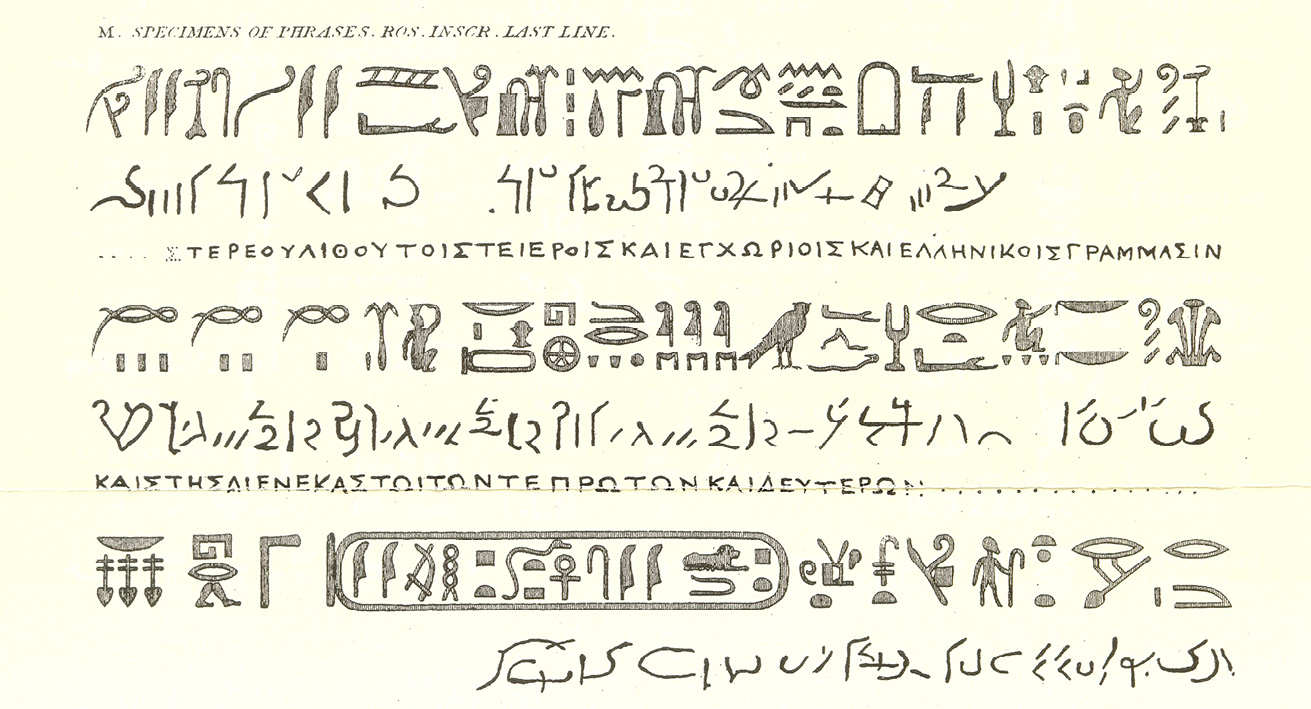

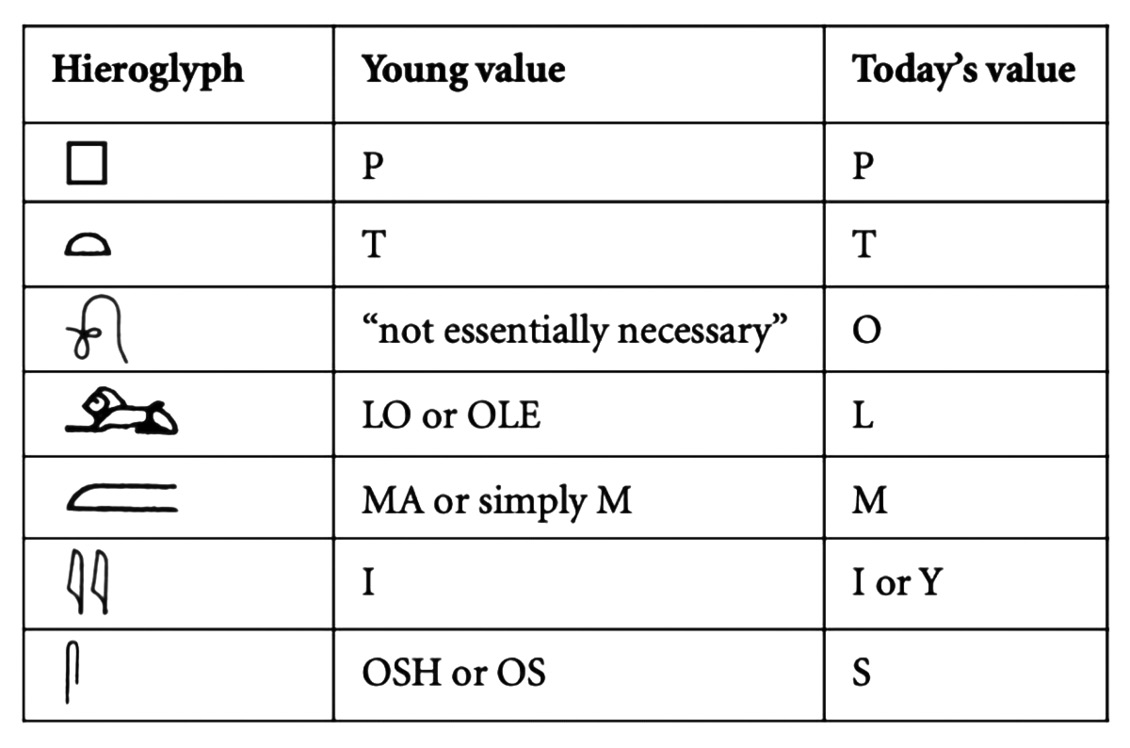

It was his powerful visual analysis of the hieroglyphic and demotic inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone that gave Young the inkling of a crucial discovery. He noted a ‘striking resemblance’, not spotted by any previous scholar, between some demotic signs and what he called ‘the corresponding hieroglyphics’[299]—the first intimation that demotic might relate directly to hieroglyphic, and not be a completely different script, somewhat as a modern cursive handwritten script partly resembles its printed equivalent. We can see this relationship from the drawing he published showing the last line of the Rosetta inscription in hieroglyphic (which includes a cartouche), demotic and Greek, reproduced in Figure 10.3. If you examine a hieroglyphic sign and the demotic sign below it, you can see that some resemble each other. Equally clear, however, is that other ‘corresponding’ signs do not.

The clinching evidence for the truth of this partial resemblance came with the publication of several manuscripts on papyrus in the monumental French survey mentioned earlier, Description de l’Égypte, the most recent volume of which Young was able to borrow in 1815. He later wrote:

I discovered, at length, that several of the manuscripts on papyrus, which had been carefully published in that work, exhibited very frequently the same text in different forms, deviating more or less from the perfect resemblance of the objects intended to be delineated, till they became, in many cases, mere lines and curves, and dashes and flourishes; but still answering, character for character, to the hieroglyphical or hieratic writing of the same chapters, found in other manuscripts, and of which the identity was sufficiently indicated, besides this coincidence, by the similarity of the larger tablets or pictural representations, at the head of each chapter or column, which are almost universally found on manuscripts of a mythological nature.[300]

Fig. 10.3 Specimens of phrases from the last line of the Rosetta Stone inscription in hieroglyphic/demotic/Greek scripts, as shown in Young’s Encyclopaedia Britannica article, ‘Egypt’ (1819).

In other words, Young was able to trace how the recognisably pictographic hieroglyphs, showing human figures, animals, plants and objects of many kinds, had developed into their cursive equivalents in the hieratic and demotic scripts.

But if the hieroglyphic and demotic scripts resembled each other visually in many respects, did this also mean that they operated on the same linguistic principles? If so, it posed a major problem, because the hieroglyphic script was generally supposed to be purely conceptual or symbolic (except for the foreign names in the cartouches, as suggested by de Sacy), whereas the demotic script was supposed (by Åkerblad) to be purely alphabetical. The two views could not be satisfactorily reconciled, if some of the signs in the demotic scripts were in fact hieroglyphic in origin.

So Young took the next logical step and made another important discovery. He told de Sacy in a letter in August 1815: ‘I am not surprised that, when you consider the general appearance of the [demotic] inscription, you are inclined to despair of the possibility of discovering an alphabet capable of enabling us to decipher it; and if you wish to know my “secret”, it is simply this, that no such alphabet ever existed’.[301] His conclusion was that the demotic script consisted of ‘imitations of the hieroglyphics […] mixed with letters of the alphabet.’[302] It was neither a purely conceptual or symbolic script, nor an alphabet, but a mixture of the two. As Young wrote a little later, employing an analogy for the demotic script that perhaps only a polymath such as he could have come up with, ‘it seemed natural to suppose, that alphabetical characters might be interspersed with hieroglyphics, in the same way that the astronomers and chemists of modern times have often employed arbitrary marks, as compendious expressions of the objects which were most frequently to be mentioned in their respective sciences.’[303] A modern, non-scientific example of the same idea would be such ‘compendious’ signs as $, £, %, =, +, which represent concepts non-phonetically, and often appear adjacent to alphabetic letters.

Young was correct in these two discoveries about the relationship between the hieroglyphic and demotic scripts. But we must also note that the discoveries did not now lead him to make a third discovery. He did not question the almost-sacred notion that the hieroglyphic script was purely symbolic. He continued to adhere to the view that the only phonetic elements in the hieroglyphic script were to be found in the foreign names in the cartouches, as first suggested by de Sacy. The idea that the hieroglyphic script as a whole might be a mixed script like the demotic script was to be the revolutionary breakthrough of Champollion.

As yet, in 1815, Young and Champollion, who started work on the Rosetta Stone around the same time as Young, had had little contact with each other. The previous November, Champollion had written to the president of the Royal Society from his base in Grenoble, enclosing his new book on Egypt and requesting some clarifications of parts of the Rosetta inscription which were not clear in his French copy; and Young, as the society’s foreign secretary, had willingly obliged him, while also adding that Champollion might wish to consult his own conjectural translation of the Rosetta Stone which he had recently sent to de Sacy, one of Champollion’s teachers when he had studied in Paris. This was really all that had passed between Young and Champollion. Young must therefore have been very taken aback to receive a letter from de Sacy written from Paris in July which openly warned him about his ex-student:

If I might venture to advise you, I would recommend you not to be too communicative of your discoveries to M. Champollion. It may happen that he may hereafter make pretension to the priority. He seeks, in many parts of his book, to make it believed that he has discovered many words of the Egyptian inscription of the Rosetta Stone: but I am afraid that this is mere charlatanism: I may add that I have very good reasons for thinking so.[304]

De Sacy was writing a mere month after the battle of Waterloo, in which Champollion had supported the defeated Napoleon, and it was clear from other remarks made by de Sacy that the revolutionary ex-student and the royalist former professor were now deeply divided by politics in addition to linguistic scholarship. Even so, de Sacy’s explicit warning had a prophetic ring, and to some extent put Young on his guard against his leading competitor. ‘Since Champollion was obsessed by anything to do with ancient Egypt, this warning was partly justified, and should not be dismissed merely as academic jealousy on the part of a former teacher,’ writes the Egyptologist John Ray.[305] What had started as a frank exchange of letters between Champollion and Young in 1814–1815 would never develop into a major intellectual correspondence—in stark contradiction to Young’s exchanges about the wave theory of light with French physicists during the same period, which we shall come to in the next chapter. In 1815, Young already felt he was the leader in the hieroglyphic field, but Champollion—though considerably younger—was not willing then, or at any point thereafter, to accept a subservient role.

Over the next three years, Young made a number of solid contributions to the decipherment of hieroglyphic and demotic. For example, he identified hieroglyphic plural markers and various numerical notations, and a special sign used to mark feminine names. But his most important further discovery, following his two insights into the demotic-hieroglyphic relationship, arose from Barthélemy’s idea that the cartouches expressed royal or religious names and de Sacy’s idea that foreign names in the cartouches might be spelt phonetically.

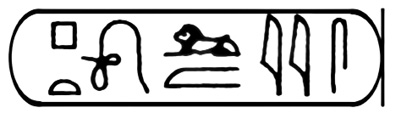

There were six cartouches on the Rosetta Stone. From the Greek translation, these cartouches clearly had to contain the name Ptolemy (Ptolemaios, in Greek). Three of them looked like this:

and the other three like this:

Young postulated that the longer cartouche wrote the name of Ptolemy with a title, as suggested by equivalents in the Greek inscription, which read ‘Ptolemy, living for ever, beloved of Ptah’.

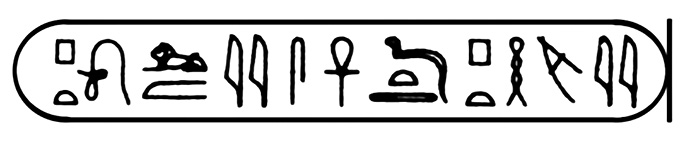

This enabled Young to match the hieroglyphic signs in the short cartouche with known letters and phonetic values. Here is what he deduced, along with today’s accepted phonetic value:

And here is his reasoning for these values:

The square block and the semicircle answer invariably in all the manuscripts to characters resembling the P and T of Åkerblad, which are found at the beginning of the enchorial name [i.e., the assumed name of Ptolemy written in demotic]. The next character, which seems to be a kind of knot, is not essentially necessary, being often omitted in the sacred characters [i.e., hieroglyphic], and always in the enchorial. The lion corresponds to the LO of Åkerblad; a lion being always expressed by a similar character in the manuscripts; an oblique line crossed standing for the body, and an erect line for the tail: this was probably read not LO but OLE; although, in more modern Coptic, OILI is translated as ram; we have also EIUL, a stag; and the figure of the stag becomes, in the running hand [i.e., demotic or hieratic], something like this of the lion. The next character is known to have some reference to ‘place’, in Coptic MA; and it seems to have been read either MA, or simply M; and this character is always expressed in the running hand by the M of Åkerblad’s alphabet. The two feathers, whatever their natural meaning may have been, answer to the three parallel lines of the enchorial text, and they seem in more than one instance to have been read I or E; the bent line probably signified great, and was read OSH or OS; for the Coptic SHEI seems to have been nearly equivalent to the Greek sigma. Putting all these elements together we have precisely PTOLEMAIOS, the Greek name; or perhaps PTOLEMEOS, as it would more naturally be called in Coptic.[306]

This passage was worth quoting at length to show that Young was sometimes capable of poor reasoning as well as his typical acuity. His analysis of Ptolemy’s cartouche was mostly on target, but he was plainly wrong about the value of the knot, and also wrong in assuming that some of the phonetic values might be syllabic rather than alphabetic. He was less successful with the cartouche of a Ptolemaic queen, Berenice, which he guessed to be hers from a copy of an inscription beside her portrait in the temple complex of Karnak at Thebes. With the two cartouches taken together, Young was able to assign six phonetic values correctly, three partly so, while four were assigned incorrectly: the beginnings of his hieroglyphic ‘alphabet’.

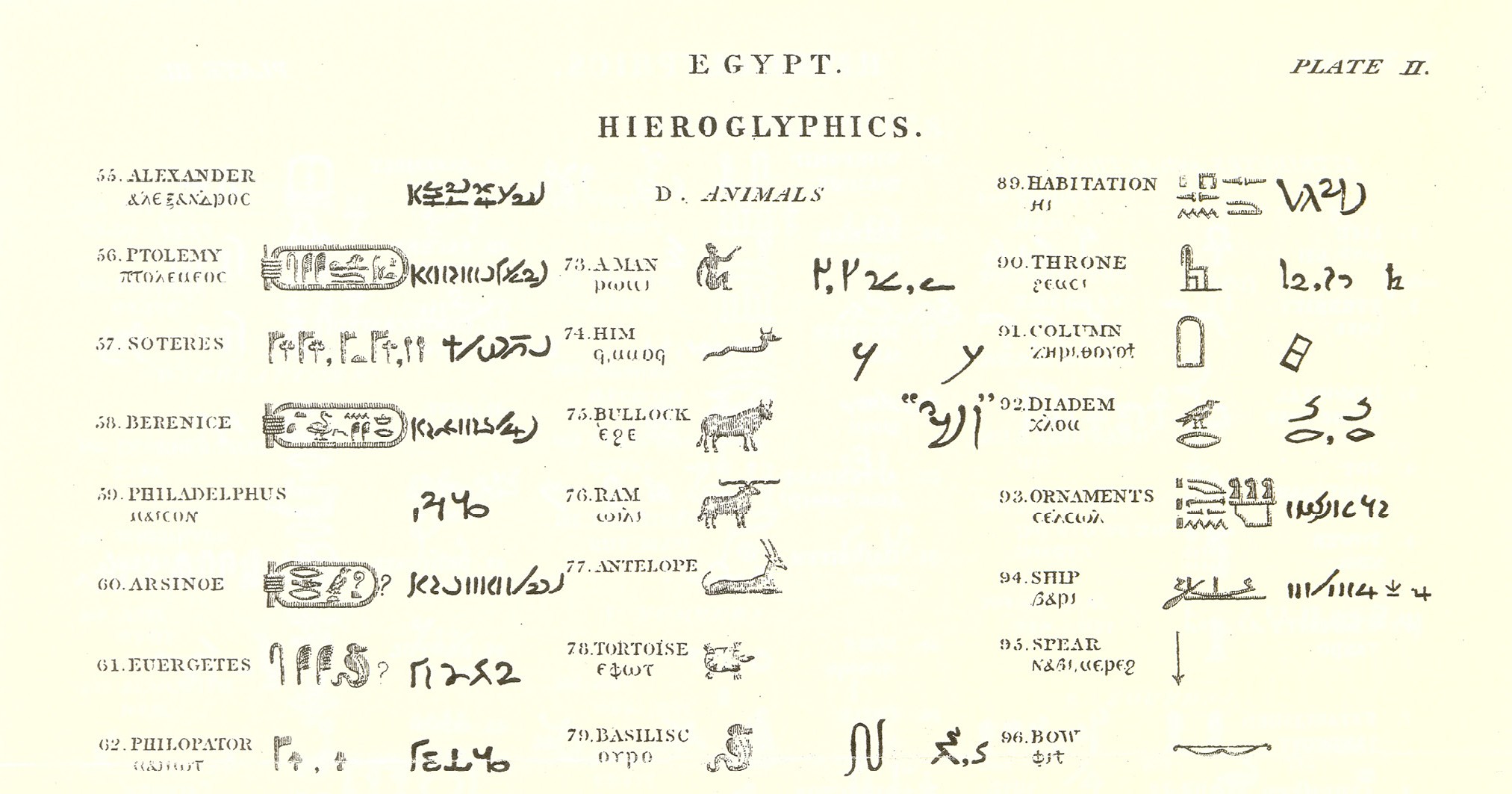

In 1818, Young summarised his Egyptian labours in a magnificent article, ‘Egypt’, in the supplement to the fourth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which appeared in 1819.[307] Here he published a vocabulary in English offering equivalents for 218 demotic and 200 hieroglyphic words, including proper names, things and numerals, a portion of which is shown in Figure 10.4; his phonetic values for thirteen hieroglyphs, cautiously headed ‘Sounds?’; and a ‘Supposed enchorial alphabet’ for the demotic script. About eighty of his demotic-hieroglyphic equivalents have stood the test of time until today—an impressive record. Nothing remotely resembling this article had been published before on the subject of ancient Egyptian writing. Despite the fact that Young’s results were ‘mixed up with many false conclusions,’ noted Francis Llewellyn Griffith, a highly respected Egyptologist working a century or so after him, ‘the method pursued was infallibly leading to definite decipherment.’[308] Young’s article on ‘Egypt’ was a landmark. But it was also anonymous: not until 1823 did he publish on Egypt under his own name. This self-effacement would undoubtedly encourage Champollion in his desire to avoid giving Young more credit than he absolutely had to.

Fig. 10.4 Part of Young’s hieroglyphic and demotic vocabulary, as shown in his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, ‘Egypt’ (1819).

Of course most of those interested in ancient Egyptian inscriptions—a growing number of travellers and scholars curious and wealthy enough to visit Egypt and collect its antiquities—knew perfectly well who the anonymous author of the Encyclopaedia Britannica article was. In the 1820s, Young (like Champollion in France) was in constant communication with many such people, in a determined effort to obtain as many copies of new inscriptions and manuscripts as he could. One of them, the flamboyant circus actor, engineer, explorer and excavator Giovanni Belzoni (who first tunnelled under the middle pyramid at Giza), wrote in his grand folio Belzoni’s Travels, published in 1820:

I have the satisfaction of announcing to the reader, that, according to Dr Young’s late discovery of a great number of hieroglyphics, he found the names of Nichao and Psammethis his son, inserted in the drawings I have taken of this tomb. It is the first time that hieroglyphics have been explained with such accuracy, which proves the doctor’s system beyond doubt to be the right key for reading this unknown language; and it is to be hoped, that he will succeed in completing his arduous and difficult undertaking, as it would give to the world the history of one of the most primitive nations, of which we are now totally ignorant.[309]

Champollion was not even mentioned by Belzoni. In 1820, the French scholar was still virtually lost in the maze of the hieroglyphs. In Chapter 15, ‘Duelling with Champollion,’ we shall see how Champollion extricated himself in 1821–1822, and in a few short months overtook Young. But before coming to that, we must return to Young’s interests in natural philosophy and see how his undulatory theory of light—still very controversial when we left it in 1807—was at long last put on a firm scientific footing.

Notes and References

Note that the precise wording of the quotations from Young’s letters, the originals of which were available to George Peacock and Alex Wood but have since disappeared, sometimes differs in their two biographies; in each case, I have chosen what appears to me to be the most reliable version.

[278] Letter to Gurney (no date given) in Peacock: 261. Wood: 210 gives the date as Aug. 1814.

[279] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: ix.

[280] Quoted in Peacock: 486.

[281] Quoted in Boas: 101.

[282] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 3.

[283] Boas: 63.

[284] Ibid: 49–50.

[285] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edn: entry for ‘Kircher, Athanasius’.

[286] See the subtitle of the book by Findlen.

[287] Quoted in Pope: 31–32.

[288] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 2.

[289] Ibid: 7.

[290] Pope: 58.

[291] Quoted in Claiborne: 24.

[292] Parkinson, The Rosetta Stone: 47.

[293] Parkinson, Cracking Codes: 25.

[294] Quoted in Andrews: 28.

[295] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 9.

[296] Ibid: xiv–xv.

[297] Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 612.

[298] Peacock: 281. The five volumes of Young’s MSS in the British Library have the shelf mark Add. 27281–27285.

[299] Letter to Sylvestre de Sacy (3 Aug. 1815) in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 54.

[300] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 15–16.

[301] Letter to de Sacy (3 Aug. 1815) in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 53.

[302] Ibid: 54.

[303] Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 133.

[304] Letter to Young (20 July 1815) in Peacock: 266–67. The French original appears in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 51.

[305] Ray, ‘The name of the first: Thomas Young and the decipherment of Egyptian writing’ (unpublished lecture).

[306] Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 156–57.

[307] Young’s article for the Encyclopaedia Britannica appears in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 86–197; the vocabulary is at the end on fold-out sheets.

[308] Quoted in Gardiner: 14.

[309] Belzoni: 205–06.