15. Duelling with Champollion

© 2023 Andrew Robinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0344.15

Mr Champollion, junior […] has lately been making some steps in Egyptian literature, which really appear to be gigantic. It may be said that he found the key in England which has opened the gate for him, and it is often observed that c’est le premier pas qui coûte [it is the first step which costs]; but if he did borrow an English key, the lock was so dreadfully rusty, that no common arm would have had strength enough to turn it.

Young, letter to William Hamilton, 1822 [397]

When Young returned to London from his grand tour in late 1821, a highly dramatic new phase in ancient Egyptian researches was about to begin. In the first phase, from the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 until the publication of his Encyclopaedia Britannica article, ‘Egypt’, in 1819, Young had had the field of hieroglyphic decipherment largely to himself. Now he would be joined in earnest by Champollion, who would quickly overtake him and become the founder of Egyptology as a science.

During the 1820s, the two men sometimes cooperated with each other, but mostly they competed as rivals. Their relationship could never have been a harmonious one. Young claimed that Champollion had built his system of reading hieroglyphics on Young’s own discoveries and his hieroglyphic ‘alphabet’, published in 1815–1819. While paying generous and frequent tribute to Champollion’s unrivalled progress since then, Young wanted his early steps recognised. This Champollion was adamantly unwilling to concede, and in his vehemence he determined to give all of Young’s work the minimum possible public recognition. Just weeks before Young’s death in 1829, Champollion, writing in the midst of his expedition to ancient Egypt—he was then at Thebes in the Valley of the Kings (a place he had just named)—exulted privately to his brother back in France:

So poor Dr Young is incorrigible? Why flog a mummified horse? Thank M. Arago for the arrows he shot so valiantly in honour of the Franco-Pharaonic alphabet. The Brit can do whatever he wants—it will remain ours: and all of old England will learn from young France how to spell hieroglyphs using an entirely different method […] May the doctor continue to agitate about the alphabet while I, having been for six months among the monuments of Egypt, I am startled by what I am reading fluently rather than what my imagination is able to come up with.[398]

The nationalistic overtones—at times evident in Young’s writings, too—have to some extent bedevilled honest discussion of Young and Champollion ever since those Napoleonic days of intense Franco-British political rivalry. Even Young’s loyal friend, the physicist Arago, turned against his work on the hieroglyphics, at least partly because Champollion was an honoured fellow countryman. Thus, a recent French book for the general reader by a writer of Egyptian origin, Robert Solé, and the Egyptologist Dominique Valbelle, translated into English as The Rosetta Stone: The Story of the Decoding of Hieroglyphics, deliberately omits the trenchant criticism of Champollion’s character written to Young in 1815 by his former teacher Sylvestre de Sacy (who would hail Champollion for his success ten years later), quoted earlier; it also omits two other controversial episodes, in which Champollion is generally held to have suppressed an erroneous publication of his own and to have failed to acknowledge a crucial inscriptional clue provided by another. (We shall come to these in more detail.)

Alongside this, Egyptologists, who are the people best placed to understand the intellectual ‘nitty-gritty’ of the dispute, are naturally drawn to Champollion more than Young, because Champollion founded their subject. No scholar of ancient Egypt would wish to think ill of such a pioneer. Even John Ray, the Egyptologist who has done most in recent years to give Young his proper due, admits: ‘the suspicion may easily arise, and often has done, that any eulogy of Thomas Young must be intended as a denigration of Champollion. This would be shameful coming from an Egyptologist.’[399]

Then there is the cult of genius to consider: the fact that many of us prefer to believe in the primacy of unaccountable moments of inspiration over the less glamorous virtues of step-by-step, rational teamwork. Champollion maintained that his breakthroughs came almost exclusively out of his own mind, arising from his indubitably passionate devotion to ancient Egypt. He pictured himself for the public as a ‘lone genius’ who solved the riddle of ancient Egypt’s writing single-handedly. The fact that Young was known primarily for his work in fields other than Egyptian studies, and that he published on Egypt anonymously in his first phase, made Champollion’s solitary self-image easily believable for most people. It is a disturbing thought, especially for a specialist, that a non-specialist might enter an academic field, transform it, and then move onwards to work in an utterly different field.

Lastly, in trying to assess Young and Champollion, there is no avoiding the fact that they were highly contrasting personalities and that this contrast sometimes influenced their research on the hieroglyphs. Champollion had tunnel vision (‘fortunately for our subject’, says Ray); was prone to fits of euphoria and despair; and had personally led an uprising against the French king in Grenoble, for which he was put on trial. Young, apart from his polymathy and a total lack of engagement with party politics, was a man who ‘could not bear, in the most common conversation, the slightest degree of exaggeration, or even of colouring’ (according to Gurney).[400] They were poles apart intellectually, emotionally and politically.

Consider their respective attitudes to ancient Egypt. Young never went to Egypt, and never wanted to go. In founding an Egyptian Society in London in 1817, to publish as many ancient inscriptions and manuscripts as possible, so as to aid the decipherment, Young remarked that funds were needed ‘for employing some poor Italian or Maltese to scramble over Egypt in search of more.’[401] Champollion, by contrast, had long dreamt of visiting Egypt and doing exactly what Young had depreciated, ever since he saw the hieroglyphs as a boy; and when he finally got there, he was able to pass for a native, given his swarthy complexion and his excellent command of Arabic. In his wonderfully readable and ebulliently human Egyptian Diaries, Champollion describes entering the temple of Ramses the Great at Abu Simbel, which was blocked by millennia of sand:

I almost entirely undressed, wearing only my Arab shirt and long underwear, and pressed myself on my stomach through the small aperture of a doorway which, unearthed, would have been at least twenty-five feet high. It felt as if I was climbing through the heart of a furnace and, gliding completely into the temple, I entered an atmosphere rising to fifty-two degrees: holding a candle in our hand, Rosellini, Ricci, I and one of our Arabs went through this astonishing cave.[402]

Such a perilous adventure would probably not have appealed to Young, even in his carefree youth as an accomplished horseman roughing it in the Scottish Highlands. His motive for ‘cracking’ the Egyptian scripts was fundamentally philological and scientific, not aesthetic and cultural (unlike his attitude to the classical literature of Greece and Rome). Many Egyptologists, and humanities scholars in general, tend not to sympathise with this motive. They also know little about Young’s scientific work and his renown as someone who initiated many new areas of scientific enquiry and left others to develop them. As a result, some of them seriously misjudge Young. Not knowing of his fairness in recognising other scientists’ contributions and his fanatical truthfulness in his own scientific work, they jump to the obvious conclusion that Young’s attitude to Champollion was chiefly envious. The classicist Maurice Pope says this more or less in his book, The Story of Decipherment, as quoted in the introduction; while two archaeologists, Lesley and Roy Adkins, in The Keys of Egypt: The Race to Read the Hieroglyphs, state openly that ‘while maintaining civil relations with his rival, Young’s jealousy had not ceased to fester.’[403] Not only would such an emotion have been out of character for Young, it would not have made much sense, given his major scientific achievements and the fact that these were increasingly recognised from 1816 onwards—starting with French scientists. For Champollion, the success of his decipherment was a matter of make or break as a scholar; for Young, his Egyptian research was essentially yet another fascinating avenue of knowledge to explore for his own amusement.

Champollion’s first significant publication on the Egyptian scripts came in April 1821, and appeared from Grenoble, just three months before he left that city for Paris. Nowhere in it did he make any reference to Young, and, according to Champollion, he was unaware of Young’s Encyclopaedia Britannica article ‘Egypt’ until he returned to Paris. His De l’Écriture Hiératique des Anciens Égyptiens consisted of a mere seven pages of text and seven plates. It announced four firm conclusions, of which two were important. One was correct: that the hieratic script on Egyptian manuscripts—and hence presumably the demotic script—was only a ‘simple modification’ of the hieroglyphic.[404] (Young had come to a similar conclusion in 1815 and published it in his ‘Egypt’ in 1819.) The other conclusion was incorrect: that the hieratic/demotic characters were ‘signs of things and not of sounds’—in other words, there was no phonetic element in the hieratic/demotic script, which was a conceptual script like the hieroglyphs, said Champollion. (Young, and before him Åkerblad, of course was certain that there was an alphabetical element in the demotic, but that this element was mixed with non-phonetic signs derived from the hieroglyphs.)

The error was a serious one, and it seems as though Champollion soon realised this, because he is alleged to have made strenuous efforts to withdraw all copies of his 1821 publication, suppress the text and redistribute only the plates. The allegation is likely to have been true, given the subsequent rarity of the publication, the fact that Champollion presented only the plates to Young, who was unaware of the text, and—most telling of all—that Champollion chose to make no reference of any kind to the publication in his breakthrough publication of 1822. Clearly, in the year that elapsed between August 1821 (when Champollion lectured to the Academy of Inscriptions in Paris on the ideas in his Grenoble publication) and his announcement of a decipherment to the same institute in September 1822, Champollion changed his mind and decided that there was, after all, an alphabetic element in the Egyptian scripts. The question then becomes, what caused his change of mind?

It was now, in Paris in 1821–1822, that Champollion definitely studied Young’s article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, by his own admission. Though the idea does not seem credible, Champollion asked the world to believe that the article did not substantially influence his thinking. But it would, without doubt, have made him aware of Young’s belief in a phonetic element in the scripts, published in the form of a short list of hieroglyphs representing ‘Sounds’ and a second list of demotic signs labelled ‘Supposed enchorial alphabet’. Moreover, Champollion could not conceivably have missed the fact that Young’s rudimentary hieroglyphic ‘alphabet’ had been derived from the cartouches of Ptolemy and Berenice, as we explained in Chapter 10, ‘Reading the Rosetta Stone’. Surely, having absorbed this 1819 article, and earlier work by Young, Champollion was now primed to take his first correct original step.

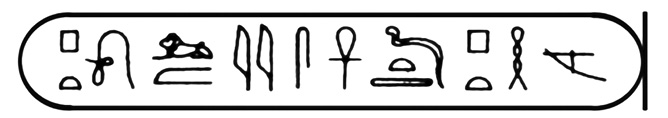

It came in January 1822, when he saw a copy of an obelisk inscription sent to the National Institute in Paris by the English collector William Bankes, who had had the obelisk removed from Philae (near Aswan) by Giovanni Belzoni and transported to Bankes’s country house in England, where it still stands. The importance of the obelisk was that it was bilingual. The base-block inscription was in Greek, while the column inscription was in hieroglyphic script. This, however, did not make it a true bilingual, a second Rosetta Stone, because the two inscriptions did not match. Notwithstanding, in 1818, Bankes realised that in the Greek letters the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra, Ptolemaic queen, were mentioned, while in the hieroglyphs two (and only two) cartouches occurred—presumably representing the same two names as written in Greek on the base. One of these cartouches was almost the same as a longer cartouche on the Rosetta Stone identified as Ptolemy by Young:

—so the second obelisk cartouche was likely to read Cleopatra. In sending a copy of the inscription to scholars, including the National Institute, Bankes pencilled his identification of Cleopatra in the margin of the copy.

Unfortunately for Young, the copy that came to him contained a significant error. The copyist had expressed the first letter of Cleopatra’s name with the sign for a T instead of a K. So, says Young, ‘as I had not leisure at the time to enter into a very minute comparison of the name with other authorities’—this was the period when he took over the Nautical Almanac—’I suffered myself to be discouraged with respect to the application of my alphabet to its analysis’.[405] In other words, Young had an unlucky break here, but he was also undermined by his lifelong tendency to spread himself.

Champollion, however, was not a man to be diverted from study of Egypt by other interests and duties. He took the new clue—without any acknowledgment to Bankes or Young—and ran with it. Just as Young had done, he decided that a shorter version of the Ptolemy cartouche on the Rosetta Stone spelt only Ptolemy’s name:

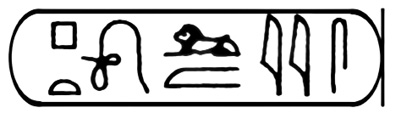

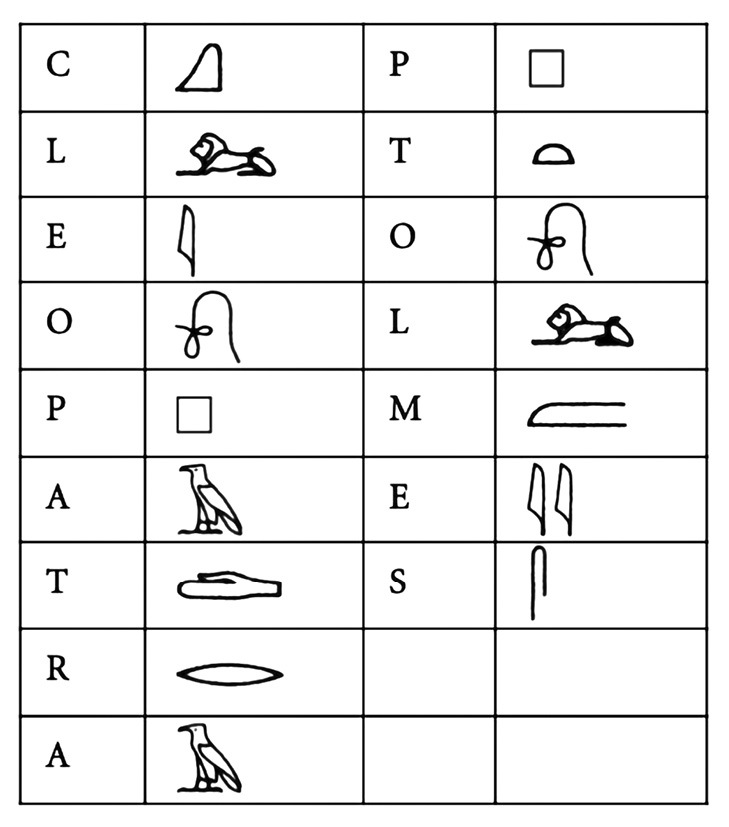

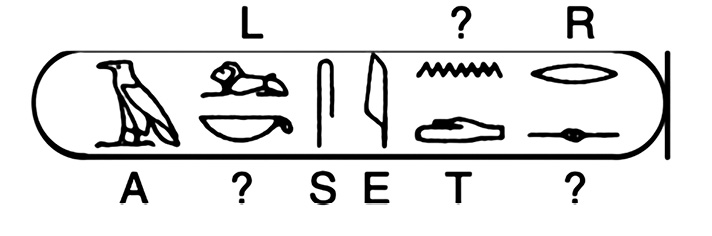

while the longer cartouche must involve some royal title, tacked on to Ptolemy’s name. Again, as Young had done, Champollion assumed that Ptolemy was spelt alphabetically, and thus, following Bankes’s identification, that the same applied to Cleopatra on the obelisk from Philae. He proceeded to guess the phonetic values of the hieroglyphs in both cartouches:

There were four signs in common, those with the phonetic values L, E, O and P, but the phonetic value T was represented differently in the two names. Champollion deduced correctly that the two signs for T were what is known as homophones, that is, different signs with the same sound (compare in English Jill and Gill, Catherine and Katherine)—a concept that Young was also aware of.

The real test of the decipherment, however, was whether these new phonetic values, when applied to the cartouches in other inscriptions, would produce sensible names. Champollion tried them in the following cartouche:

Substitution produced AL?SE?TR?. Champollion guessed ALKSENTRS = (Greek) ALEXANDROS [ALEXANDER]—again the two signs for K/C (𓎡 and 𓏘) are homophonous, as are the two signs for S (𓊃 and 𓋴).

Using the growing alphabet, Champollion went on to identify the cartouches of other rulers of non-Egyptian origin, Berenice (already tackled, though with mistakes, by Young) and Caesar, and a title of the Roman emperor, Autocrator. It was quickly obvious to him that many more identifications would now follow. On 27 September 1822, Champollion felt ready to announce his breakthrough at a meeting of the Academy of Inscriptions, and to follow it in October with the publication of his celebrated Lettre à M. Dacier—Bon-Joseph Dacier was the secretary of the Academy—in which he unveiled his first shot at a complete hieroglyphic/demotic list of signs with their Greek equivalents, accompanied by a light-hearted cartouche of his own name written in demotic script. (This understandable flourish, which Champollion omitted from his later, more dignified publications, is something not easy to imagine from the pen of his more soberly scientific rival, Young.)

Young was in Paris again at the time and was present at the meeting on 27 September. In fact, he was invited to sit next to Champollion while he read out his paper. It was the first personal encounter of the two decipherers, who were formally introduced by Arago after the meeting, and naturally they had much to discuss, although Young could hardly avoid noticing Champollion’s lack of open acknowledgment of his own work. He wrote to Hudson Gurney from Paris:

Fresnel, a young mathematician of the Civil Engineers, has really been doing some good things in the extension and application of my theory of light, and Champollion […] has been working still harder upon the Egyptian characters. He devotes his whole time to the pursuit and he has been wonderfully successful in some of the documents that he has obtained—but he appears to me to go too fast—and he makes up his mind in many cases where I should think it safer to doubt. But it is better to do too much than to do nothing at all, and others may separate the wheat from the chaff when his harvest is complete. How far he will acknowledge everything which he has either borrowed or might have borrowed from me I am not quite confident, but the world will be sure to remark que c’est le premier pas qui coûte, though the proverb is less true in this case than in most, for here every step is laborious. I have many things I should like to show Champollion in England, but I fear his means of locomotion are extremely limited, and I have no chance of being able to augment them.[406]

Young’s work was conspicuously downplayed in the Lettre à M. Dacier—so patently, in fact, that anyone knowledgeable of the recent history of the Rosetta Stone could not fail to conclude that Champollion had done this deliberately. As Young would remark publicly the following year, with notable understatement: ‘I did certainly expect to find the chronology of my own researches a little more distinctly stated.’[407] Champollion’s first publication of the decipherment shows that from the very beginning he was set on keeping all the glory for himself, since he could have had no other motive to downplay Young’s role in October 1822, before Young had made a single public criticism of him or his work.

His attitude to Young comes out most clearly if we consider Champollion’s description of how Cleopatra’s cartouche was identified and used to construct an alphabet, as translated by Young himself from the Lettre à M. Dacier (the italic emphases are also Young’s):

The hieroglyphical text of the inscription of Rosetta exhibited, on account of its fractures, only the name of Ptolemy. The obelisk found in the Isle of Philae, and lately removed to London, contains also the hieroglyphical name of one of the Ptolemies, expressed by the same characters that occur in the inscription of Rosetta, surrounded by a ring or border, which must necessarily contain the proper name of a woman, and of a queen of the family of the Lagidae, since this group is terminated by the hieroglyphics expressive of the feminine gender; characters which are found at the end of the names of all the Egyptian goddesses without exception. The obelisk was fixed, it is said, to a basis bearing a Greek inscription, which is a petition of the priests of Isis at Philae, addressed to King Ptolemy, to Cleopatra his sister, and to Cleopatra his wife. Now, if this obelisk, and the hieroglyphical inscription engraved on it, were the result of this petition, which in fact adverts to the consecration of a monument of the kind, the border, with the feminine proper name, can only be that of one of the Cleopatras. This name, and that of Ptolemy, which in the Greek have several letters in common, were capable of being employed for a comparison of the hieroglyphical characters composing them; and if the similar characters in these names expressed in both the same sounds, it followed that their nature must be entirely phonetic.[408]

There is not even a nod here to Young (or Bankes). The fact stung him—encouraged by his friend Gurney—into publishing a book for a general readership, this time under his own name, entitled An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities. He comments on the previous passage by Champollion as follows:

This course of investigation appears, indeed, to be so simple and so natural, that the reader must naturally be inclined to forget that any preliminary steps were required: and to take it for granted, either that it had long been known and admitted, that the rings on the pillar of Rosetta contained the name of Ptolemy, and that the semicircle and the oval constituted the female termination, or that Mr Champollion himself had been the author of these discoveries.

It had, however, been one of the greatest difficulties attending the translation of the hieroglyphics of Rosetta, to explain how the groups within the rings [cartouches], which varied considerably in different parts of the pillar, and which occurred in several places where there was no corresponding name in the Greek, while they were not to be found in others where they ought to have appeared, could possibly represent the name of Ptolemy; and it was not without considerable labour that I had been able to overcome this difficulty. The interpretation of the female termination had never, I believe, been suspected by any but myself: nor had the name of a single god or goddess, out of more than five hundred that I have collected, been clearly pointed out by any person.

But, however Mr Champollion may have arrived at his conclusions, I admit them, with the greatest pleasure and gratitude, not by any means as superseding my system, but as fully confirming and extending it.[409]

Indeed, Young added a provocative subtitle to his book: ‘Including the Author’s Original Alphabet, As Extended by Mr Champollion’.

Champollion was duly provoked. In March 1823, having seen only an advertisement for the new book, he wrote angrily to Young: ‘I shall never consent to recognise any other original alphabet than my own, where it is a matter of the hieroglyphic alphabet properly called; and the unanimous opinion of scholars on this point will be more and more confirmed by the public examination of any other claim.’[410] Scholarly war had been declared.

Young’s supporters felt that he had taken the vital first steps that had enabled Champollion to advance, and that Champollion had either ignored these or claimed that he had come to the same conclusions independently. ‘Nothing can exceed the effrontery of Champollion in thus complaining to Dr Young, the author of the discoveries […] as if he himself were the person aggrieved,’ wrote John Leitch[411], the editor of Young’s linguistic works, in the 1850s. Champollion’s supporters argued, by and large, that while Young had taken some first steps, not all of them were correct, as witness his misreading of some of the signs in the cartouches of Ptolemy and Berenice. Champollion, they said, had established a system that worked easily when applied to new cartouches, as opposed to Young’s more ad hoc methods, that in some cases required ingenious manipulation to produce phonetic values. And inevitably they pointed to Champollion’s truly revolutionary progress from 1823 onwards, which Young himself generally admired.

At the end of the chapter, ‘Mr Champollion’, in his book, Young summarised his basic wish:

[that] the further [Champollion] advances by the exertion of his own talents and ingenuity, the more easily he will be able to admit, without any exorbitant sacrifice of his fame, the claim that I have advanced to a priority with respect to the first elements of all his researches; and I cannot help thinking that he will ultimately feel it most for his own substantial honour and reputation, to be more anxious to admit the just claims of others than they be to advance them.[412]

This was a reasonable, temperate request, but it fell on stony ground. Either Champollion had too much vanity to concede anything important to Young, or he had genuinely convinced himself, through his long years of obsession with ancient Egypt, that the crucial first steps were really taken by him—or perhaps there was an amalgam of both feelings in his mind. By sticking intransigently to his claim of sole authorship, he achieved his ambition and came to enjoy general acceptance as the decipherer of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. But in so doing he lost his good name. Young was right in his gentle warning: Champollion’s personal reputation will forever be tainted by his hubris toward Young.

By the time that Young’s book appeared, Champollion was already far ahead of him in the hieroglyphic decipherment. In April 1823, he unveiled his second great breakthrough, which he had hinted at in his Lettre à M. Dacier. There he had shown that his alphabet could be applied to the cartouches of ancient rulers of Egyptian origin, the pharaohs, as well as to the more recent non-Egyptian Ptolemies of Greek and Roman times. In particular, he had identified a cartouche from Abu Simbel that seemed to spell the name Ramses, a king who, according to a well-known Greek history of Egypt written by the Ptolemaic historian Manetho in the third century bc, belonged to the nineteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt. Now, in his second publication six months after the Lettre, Champollion successfully began to apply his alphabet to the main text in the hieroglyphic script—not just the royal names in the cartouches. From this, he found the courage to reject and transcend the centuries-old, stifling belief that hieroglyphic was an entirely conceptual script that used phonetic signs only to represent non-Egyptian names. With this radical new assumption—that the writing system of the ancient Egyptians, both the hieratic/demotic and the hieroglyphic, was a mixture of conceptual signs and phonetic signs—Champollion was able to transliterate hundreds of ordinary hieroglyphic words. In many cases, he knew that his transliteration was likely to be correct because it resembled a word in Coptic with a meaning that made sense in the hieroglyphic context (Coptic being the most recent stage of the ancient Egyptian language). It is mainly the Coptic clue that enables us to guess roughly how the hieroglyphic inscriptions must have sounded when read aloud.

In 1824, after many more months of intensive study of hieroglyphs in various Egyptian inscriptions and papyrus manuscripts, Champollion published his definitive statement of his decipherment, Precis du Système Hiéroglyphique des Anciens Égyptiens. In his introduction, he made a point of stating what he saw as Young’s contribution:

I recognise that he was the first to publish some correct ideas about the ancient writings of Egypt; that he also was the first to establish some correct distinctions concerning the general nature of these writings, by determining, through a substantial comparison of texts, the value of several groups of characters. I even recognise that he published before me his ideas on the possibility of the existence of several sound-signs, which would have been used to write foreign proper names in Egypt in hieroglyphs; finally that M. Young was also the first to try, but without complete success, to give a phonetic value to the hieroglyphs making up the two names Ptolemy and Berenice.[413]

Perhaps it is superfluous to comment much further. Champollion’s statement, though not inaccurate, is clearly grudging and damns Young with faint praise in its vague references to ‘correct ideas’ and ‘correct distinctions’. It fails to articulate Young’s two key perceptions of general principles, published in 1819: first, that the demotic (enchorial) script to some extent resembled the hieroglyphic script visually and hence that the former script was derived from the latter; second, that the demotic script was therefore not an alphabet but a mixture of phonetic signs and hieroglyphic signs. This line of argument was what led Young to suggest that the hieroglyphic script too might contain some phonetic elements (for spelling non-Egyptian names like Ptolemy), more than two years before his rival.

Young’s own mild verdict on the conflict, as stated in his autobiographical sketch, was: ‘He found that it is easier to gain credit in England for literature than for science; while he observed that, on the continent, there was more candour and indulgence among men of science than among scholars.’[414] Though Young does not specifically say so, one can hardly doubt that he was alluding here to the different receptions in England and France accorded to his wave theory of light and his work on the Rosetta Stone. In France, Fresnel—the scientist—had done full and prompt justice to Young’s work; Champollion—the scholar—had done it a tardy injustice.

After 1823, Young did not contribute much to the hieroglyphic decipherment, and in 1827 he abandoned his work altogether. But he certainly did not abandon the writing of ancient Egypt. Instead, he turned from the hieroglyphic to the demotic script, inspired by an amazing accidental encounter with a papyrus manuscript in late 1822 that we shall describe in the next chapter. This fluke—which Young wrote about at length in An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities—stimulated a late flowering of Egyptian activity in Young. Reading demotic became one of the manifold activities that would fill the final years of this indefatigable polymath.

Notes and References

Note that the precise wording of the quotations from Young’s letters, the originals of which were available to George Peacock and Alex Wood but have since disappeared, sometimes differs in their two biographies; in each case, I have chosen what appears to me to be the most reliable version.

[397] Letter to Hamilton (29 Sept. 1822) in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 220.

[398] Letter to Champollion-Figeac (25 Mar. 1829) in Champollion: 184.

[399] Ray, ‘The name of the first: Thomas Young and the decipherment of Egyptian writing’ (unpublished lecture).

[400] Gurney: 46.

[401] Letter to Gurney (Oct. 1817) in Peacock: 451.

[402] Letter to Champollion-Figeac (1 Jan. 1829) in Champollion: 140.

[403] Adkins: 190.

[404] Quoted in Solé and Valbelle: 76.

[405] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 49. Bankes’s contribution to the decipherment is discussed in Usick: 77–79.

[406] Letter to Gurney (Sept. 1822) in Peacock: 321–22 and Wood: 231. Both Peacock and Wood quote the letter but in somewhat different ways.

[407] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 43.

[408] Quoted in Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 44–45.

[409] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 45–46.

[410] Letter to Young (23 Mar. 1823) in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 256. The translation is from Wood: 237.

[411] Note by editor (Leitch) in Young, Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3: 255.

[412] Young, Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature: 53–54.

[413] Quoted in Parkinson, Cracking Codes: 40.

[414] Quoted in Hilts: 253.