11. The Oslo Accords and Palestine’s Political Economy in the Shadow of Regional Turmoil1

© 2023 Adam Hanieh, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345l.12

Support for Palestine has long been a deeply held principle of political movements in the Middle East. Throughout much of the 1970s, Palestinian refugee camps in countries such as Jordan and Lebanon formed an important centre of revolutionary movements in the Arab world, providing fertile ground for political and military training for much of the region’s Left (and, indeed, globally). These struggles of Palestinian refugees forced even the most pro-Western regimes in the region to pay lip service to the cause of Palestinian rights. In later decades, the successive uprisings of Palestinians living under Israeli military occupation provoked an outpouring of street demonstrations and other forms of protest across the Arab worlddemanding regimes sever political and economic ties with Israel and provide real support to the Palestinian struggle. The political networks that formed in these solidarity movements, often the most palpable expression of resistance to autocratic governments in the Middle East, would later play an important prefigurative role in the uprisings of 2011.

Given the preponderant weight of the question of Palestine to Middle East politics, it is striking how little substantive discussion there has been around issues of its political economy. In stark contrast to other parts of the region — where sharp analyses of capitalist development and the strategies adopted by states and ruling elites are regularly dissected and debated — Palestine remains largely viewed as a ‘humanitarian issue’. Much solidarity work (both in the Arab world and further afield) typically emphasises the violation of Palestinian rights and the enormous suffering this entails, rather than Palestine’s connection to the wider region and its articulation with forms of imperialist power. Placed in a category of its own, Palestine has become an exception that somehow defies the analytical tools used to unpack and comprehend neighbouring states.

In this chapter I aim to present a counter-narrative to this exceptionalism by examining some aspects of the political economy of Palestine, particularly through the period that has followed the 1993 Oslo Accords. Officially known as the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, the Oslo Accords were signed between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the Israeli government on 13 September 1993. Firmly ensconced in the framework of a ‘two-state solution’, Oslo supposedly promised ‘an end to decades of confrontation and conflict’, the recognition of ‘mutual legitimate and political rights’, and the aim of achieving ‘peaceful coexistence and mutual dignity and security and […] a just, lasting and comprehensive peace settlement.’ Its supporters claimed that Oslo would see Israel gradually relinquish control over territory in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, with the newly established Palestinian Authority (PA) eventually forming an independent state in these areas. The negotiations process and subsequent agreements between the PLO and Israel were to pave the way for the current situation in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The Palestinian Authority, which now rules over an estimated 2.6 million Palestinians in the West Bank, has become the key architect of Palestinian political strategy. Its institutions draw international legitimacy from Oslo, and its avowed strategic goal of ‘building an independent Palestinian state’ remains grounded in the same framework. The incessant calls for a return to negotiations — echoed by US and European leaders on an almost daily basis — hark back to the principles laid down in September 1993.

Several decades on, it is now common to hear Oslo described as a ‘failure’ due to the ongoing reality of Israeli occupation. The problem with this assessment is that it mistakes the stated goals of Oslo for its real aims. From the perspective of the Israeli government, rather than ending the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip — or addressing the substantive issues of Palestinian dispossession — Oslo’s role was ultimately functional. By creating the perception that negotiations would lead towards some kind of ‘peace’, Israel was able to portray its intentions as those of a partner rather than as an antithesis of Palestinian sovereignty. Based upon this perception, the Israeli government used Oslo as a fig leaf to consolidate and deepen its control over Palestinian life, employing the same strategic mechanisms wielded since the onset of the occupation in 1967. Settlement construction, restrictions on Palestinian movement, the incarceration of thousands of Palestinians, and command over borders and economic life — all came together to form a complex system of control. A Palestinian face may preside over the day-to-day administration of Palestinian affairs, but ultimate power remains in the hands of Israel. This structure has reached its apex in the Gaza Strip — where over 1.7 million Palestinians are penned into a tiny enclave with entry and exit of goods and people largely determined by Israeli dictat (with part of the administration of this system subcontracted to regional neighbours such as Egypt). In this sense, there has been no contradiction between calls to support the ‘peace process’ and deepening colonisation — the former consistently worked to enable the latter.

No less importantly, Oslo had a pernicious political effect. By reducing the Palestinian struggle to a process of bartering around slithers of land in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Oslo ideologically disarmed the not-insignificant parts of the Palestinian political movement that advocated continued resistance to Israeli colonialism and sought the genuine fulfilment of Palestinian aspirations. The most important of these aspirations was the demand that Palestinian refugees had the right to return to their homes and lands from which they had been expelled in 1947–1948. Oslo made talk of these goals appear fanciful and unrealistic, normalising a delusive pragmatism rather than tackling the foundational roots of Palestinian exile. Outside of Palestine, Oslo fatally undermined the widespread solidarity and sympathy with the Palestinian struggle built during the years of the First Intifada — displacing an orientation towards grassroots, collective support with a faith in negotiations steered by Western governments. It would take over a decade for solidarity movements to rebuild themselves.

It is worth remembering that amidst the clamour of international cheerleading for Oslo — capped by the Nobel Peace prize awarded jointly to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, and PLO leader Yasser Arafat in 1994 — a handful of perceptive voices forecast the situation we face today. Noteworthy amongst these opposition voices was Edward Said, who wrote powerfully against Oslo, commenting that its signing displayed ‘the degrading spectacle of Yasser Arafat thanking everyone for the suspension of most of his people’s rights, and the fatuous solemnity of Bill Clinton’s performance, like a 20th-century Roman emperor shepherding two vassal kings through rituals of reconciliation and obeisance’ (Said, 1993). Describing the agreement as ‘an instrument of Palestinian surrender, a Palestinian Versailles’, Said noted that the PLO would become ‘Israel’s enforcer’, helping Israel deepen its economic and political domination of Palestinian areas and consolidating a ‘state of permanent dependency’. Whilst analyses such as those of Said are important to recall simply for their remarkable prescience and as a counterpoint to the constant mythologising of the historical record, they are all the more significant today when virtually all world leaders continue to make the requisite genuflection at the altar of a chimerical ‘peace process’.

Nonetheless, one question that often goes unaddressed in analyses of Oslo and the two-state strategy is why the Palestinian leadership headquartered in the West Bank has been so willingly complicit with this disastrous project. Too often the explanation for this reduces to essentially a tautology — something akin to ‘the Palestinian leadership have made bad decisions because they are poor leaders.’ The finger is often pointed at corruption, or the difficulties of the international context that limit the available political options. What is missing from this type of explanation is a blunt fact: some Palestinians have a great stake in seeing a continuation of the status quo. Over the last two decades, the evolution of Israeli rule has produced profound changes in the nature of Palestine’s political economy. These changes have been concentrated in the West Bank, cultivating a social base that supports the political trajectory of the Palestinian leadership — one all too eager to relinquish Palestinian rights, while, in return, being incorporated into the structures of Israeli settler colonialism. It is this process of socio-economic transformation that explains the Palestinian leadership’s submission to Oslo, and points to the need for a radical break from the current Palestinian political strategy.

The Social Base of Oslo

The 1993 signing of the Oslo Accords needs to be understood through the paramount importance of the US-Israel alliance to Middle East politics. As a settler-colonial state, Israel had come into being in 1948 through the expulsion of around three-quarters of the original Palestinian population from their homes and lands (Pappe, 2006). Precisely because of this initial act of dispossession and its overarching goal of preserving itself as a self-defined ‘Jewish state’, Israel quickly emerged as a key partner of foreign powers in the region (Honig-Parnass, 2011; Machover, 2012). Inextricably tied to external support for its continued viability in a hostile environment, Israel could be counted on as a much more reliable ally than any Arab state. During the 1950s, Israel’s main external support had come from Britain and France. (In the region, Iran, up until its 1979 revolution, was the main ally of Israel.) But the June 1967 war saw the Israeli military destroy the Egyptian and Syrian air forces and occupy the West Bank, Gaza Strip, (Egyptian) Sinai Peninsula, and (Syrian) Golan Heights. Israel’s defeat of the Arab states encouraged the United States to cement itself as the country’s primary patron, supplying it annually with billions of dollars’ worth of military hardware and financial support.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellites from 1989–1992, US strategy in the Middle East continued to centre upon its alliance with Israel, alongside the oil-rich Gulf monarchies and other Arab client states such as Egypt and Jordan. However, the new international situation in the early 1990s saw a shift in how these various pillars of US power were articulated in the region. A key feature of this strategy was the goal of normalising economic and political relations between Israel and the Arab world. Precisely because of its long-privileged relationship with the United States — expressed most sharply in the massive receipts of aid without the conditionalities characteristic of loans to other states — Israel’s economy had developed in a qualitatively different direction than those of its neighbours. Israel’s capitalist class had emerged with the support of the state apparatus around activities such as construction, agriculture, and finance. But direct US financial support helped to enable the development of high value-added export industries connected to sectors such as information technology, pharmaceuticals, and security. In 2010, just under half of all Israeli exports (excluding diamonds) were considered ‘high tech’ (Brusilovsky and Gitelson, 2011, 5). Unlike with other states in the region, the United States had run a massive trade deficit with Israel since the signing of a US-Israel free trade agreement (FTA) in 1985. In this context, the push to normalisation would inevitably strengthen the position of Israel (and thus the United States) within regional hierarchies.

A precondition for this knitting together of various regional allies of the US was the dropping of Arab economic boycotts against the Israeli state. From the Israeli perspective, these boycotts were estimated to have cost a cumulative $40 billion from 1948–1994 (Retzky, 1995; Bouillon, 2006). But even more important for Israeli capital than the direct cost of being isolated from the Arab world were the barriers the boycott presented to the internationalisation of Israeli capital itself. In the mid-1980s, Israel had been hit by an economic crisis addressed in the neoliberal 1985 Economic Stabilisation Plan (ESP), which saw the privatisation of many state-owned companies and allowed the large conglomerates that dominated the Israeli economy to make the leap into international markets (Nitzan and Bichler, 2002). The ESP also opened the Israeli economy to foreign investment. Many international firms, however, were reluctant to do business with Israeli firms (or inside Israel itself) because of the secondary boycotts attached to the policies of Arab governments (Nitzan and Bichler, 2002, 337). In this sense, Oslo was very much an outcome suited to the capitalism of its time — the expansion of internationalisation that characterised the global economy of the 1990s.2 In all these ways, Oslo presented itself as the ideal tool to fortify Israel’s control over Palestinians and simultaneously strengthen its position within the broader Middle East.

On the ground, the unfolding of the Oslo process was ultimately shaped by the structures of occupation laid down by Israel during the preceding decades. Through this earlier period, the Israeli government launched a systematic campaign to confiscate Palestinian land and construct settlements in the areas that Palestinians were driven out from during the 1967 war. The logic of this settlement construction was embodied in two major strategic plans, the Allon Plan (1967) and the Sharon Plan (1981). Both these plans envisaged Israeli settlements placed between major Palestinian population centres and on top of water aquifers and fertile agricultural land. An ‘Israeli-only’ road network would eventually connect these settlements to each other and also to Israeli cities outside of the West Bank. In this manner, Israel could seize the land and resources, divide Palestinian areas from each other, and avoid as much as possible direct responsibility for the Palestinian population. The asymmetry of Israeli and Palestinian control over land, resources and economy, meant that the contours of Palestinian state formation were completely dependent upon Israeli design.

Combined with military-enforced restrictions on the movement of Palestinian farmers and their access to water and other resources, the massive waves of land confiscation and settlement building during the first two decades of the occupation transformed Palestinian landownership and modes of social reproduction. From 1967 to 1974, the area of cultivated Palestinian land in the West Bank fell by around one-third (Samara, 1988). The expropriation of land in the Jordan Valley by Israeli settlers meant that 87% of all irrigated land in the West Bank was removed from Palestinian use (Samara, 1988, 91). Military orders forbade the drilling of new wells for agricultural purposes and restricted overall water use by Palestinians, while Israeli settlers were encouraged to use as much water as needed (Graham-Brown, 1990, 68). With this deliberate destruction of the agricultural sector, poorer Palestinians — particularly youth — were displaced from rural areas and gravitated towards working in the construction and agriculture sectors inside Israel. In 1970, the agricultural sector represented over 40% of the Palestinian labour force working in the West Bank. By 1987 this figure was down to only 26%. Agriculture’s share in GDP fell from 35% to 16% between 1970 and 1991.3

Under the framework established by the Oslo Accords, Israel seamlessly incorporated these earlier changes to the West Bank into a comprehensive system of control. Palestinian life became progressively transformed into a patchwork of isolated enclaves — with the three main clusters in the north, centre and south of the West Bank divided from one another by settlement blocs. The Palestinian Authority was granted limited autonomy in areas where most Palestinians lived (so-called Areas A and B), but travel between these areas could be shut down at any time by the Israeli military. All entry to and from Areas A and B, as well as the determination of residency rights in these areas, was under Israeli authority. Israel also controlled the vast majority of water aquifers, all underground resources, and all air space in the West Bank, with Palestinians thus relying on Israeli discretion for their water and energy supplies. Israel’s complete control over all external borders, codified in the 1994 Paris Protocol economic agreement between the PA and Israel, meant that it was impossible for the Palestinian economy to develop meaningful trade relations with a third country. The Paris Protocols gave Israel the final say on what the PA was allowed to import and export. The West Bank and Gaza Strip thus became highly dependent on imported goods, with total imports ranging between 70 and 80 percent of GDP (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), https://www.pcbs.gov.ps). By 2005, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics estimated that 73.9 percent of all imports to the WB/GS originated in Israel while 87.9 percent of all WB/GS exports were destined for Israel.4

With no real economic base, the PA was completely reliant upon external capital flows of aid and loans, which were again under Israeli control. Between 1995 and 2000, 60 percent of the total PA revenue came from indirect taxes collected by the Israeli government on goods imported from abroad and destined for the Occupied Territories. This tax was collected by the Israeli government and then transferred to the PA each month according to a process outlined in the Paris Protocol.5 The other main source of PA income came from aid and foreign disbursements by the United States, Europe, and Arab governments. Indeed, figures for aid measured as a percentage of Gross National Income indicated that the West Bank and Gaza Strip was among the most ‘aid dependent’ of all regions in the world.

Changing Labour Structure

This system of control engendered two major changes to the political economy of Palestinian society. The first of these related to the nature of Palestinian labour, which increasingly became a ‘tap’ that could be turned on and off depending on the economic and political situation and the needs of Israeli capital. Beginning in 1993, Israel consciously moved to substitute the daily Palestinian labour force that commuted from the West Bank with foreign workers from Asia and Eastern Europe (Bartram, 1998). This substitution was partly enabled by the declining importance of construction and agriculture as Israel’s economy shifted away from those sectors towards hi-tech industries and exports of finance capital in the 1990s. Between 1992 and 1996, Palestinian employment in Israel declined from 116,000 workers (33 percent of the Palestinian labour force) to 28,100 (6 percent of the Palestinian labour force). Earnings from work in Israel collapsed from 25 percent of Palestinian GNP in 1992 to 6 percent in 1996 (World Bank, 2001). Between 1997 and 1999, an upturn in the Israeli economy saw the absolute numbers of Palestinian workers increase to approximately pre-1993 levels, but the proportion of the Palestinian labour force working inside Israel had nonetheless almost halved compared with a decade earlier (Farsakh, 2005, 209–10).

Instead of working inside Israel, Palestinians became increasingly dependent upon public sector employment within the PA or on transfer payments made by the PA to families of prisoners, martyrs or the needy. Public sector employment made up nearly 25 percent of total employment in the West Bank and Gaza Strip by mid-2000, a level that had almost doubled since mid-1996 (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), https://www.pcbs.gov.ps). More than half of the PA’s expenditure was to go on wages for these public sector workers. The other major sector of employment was the private sector, particularly in the area of services. This was overwhelmingly dominated by very small family-owned businesses — over 90 percent of Palestinian private sector businesses employ less than ten people — as a result of decades of Israeli de-development policies (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), https://www.pcbs.gov.ps).

Capital and the Palestinian Authority

Alongside the increasing dependence of Palestinian families on either employment or payments from the Palestinian Authority, the second major feature of the socio-economic transformation of the West Bank was related to the nature of the Palestinian capitalist class. In a situation of weak local production and extremely high dependence on imports and flows of foreign capital, the economic power of the Palestinian capitalist class in the West Bank did not stem from local industry, but rather from proximity to the PA as the main conduit of external capital inflows. Through the Oslo years this class came together through the fusion of three distinct social groups: (1) ‘Returnee’ capital, mostly from a Palestinian bourgeoisie that had emerged in the Gulf Arab states and held strong ties to the nascent Palestinian Authority; (2) families and individuals that had traditionally dominated Palestinian society, often large landowners from the pre-1967 period (particularly in the northern areas of the West Bank); and (3) those who had managed to accumulate wealth through their position as interlocutors with the occupation since 1967. While the memberships of these three groups overlapped considerably, the first was particularly significant to the nature of state and class formation in the West Bank. Gulf-based financial flows had long played a major role in tempering the radical edge of Palestinian nationalism; but their conjoining with the Oslo state-building process radically deepened the tendencies of statisation and bureaucratisation within the Palestinian national project itself.

This new, three-sided configuration of the capitalist class tended to draw its wealth from a privileged relationship with the Palestinian Authority, which assisted its growth through means such as granting monopolies for goods such as cement, petrol, flour, steel and cigarettes, issuing exclusive import permits and customs exemptions, giving sole rights to distribute goods in the West Bank/Gaza Strip, and distributing government-owned land at below value. In addition to these state-assisted forms of accumulation, much of the investment that came into the West Bank from foreign donors through the Oslo years — e.g. road and infrastructure construction, new building projects, agricultural and tourist developments — were also typically connected to this new capitalist class in some form.

In the context of the PA’s fully subordinated position, the ability to accumulate was always tied to Israeli consent and thus came with a political price — one designed to buy compliance with ongoing colonisation and enforced surrender. It also meant that the key components of the Palestinian elite — the wealthiest businessmen, the PA’s state bureaucracy and the remnants of the PLO itself — came to share a common interest with Israel’s political project. The rampant spread of patronage and corruption were the logical byproducts of this system, as individual survival depended upon personal relationships with the Palestinian Authority. The systemic corruption of the PA that Israel and Western governments regularly decried through the 1990s and the 2000s, was, in other words, a necessary and inevitable consequence of the very system that these powers had themselves established.

The Neoliberal Turn

These two major features of Palestinian class structure — a labour force dependent upon employment by the Palestinian Authority, and a capitalist class deeply imbricated with Israeli rule through the institutions of the PA itself — continued to characterise Palestinian society in the West Bank through the first decade of the 2000s. The division of the West Bank and Gaza Strip between Fatah and Hamas in 2007 deepened this transformation, with the West Bank subject to ever-more complex forms of movement restrictions and economic control. Simultaneously, Gaza has developed in a different trajectory, with Hamas rule reliant upon profits drawn from the tunnel trade and aid from states such as Qatar.

In recent years, however, there has been an important shift in the economic trajectory of the Palestinian Authority, encapsulated in a harsh neoliberal programme premised on public sector austerity and a development model aimed at further integrating Palestinian and Israeli capital in export-oriented industrial zones. This economic strategy only acts to further tie the interests of Palestinian capital with those of Israel, building culpability for Israeli colonialism into the very structures of the Palestinian economy. It has produced widening poverty levels alongside a growing polarisation of wealth. In the West Bank, real per capita GDP increased from just over $1400 in 2007 to around $1900 in 2010, the fastest growth in a decade (UNCTAD, 2011). At the same time, the unemployment rate remained essentially constant, at around 20%, among the highest in the world. One of its consequences was profound levels of poverty alongside the growing wealth of a tiny layer; indeed, the consumption of the richest 10% increased from 20.3% of total consumption in 2009 to 22.5% in 2010 (UNCTAD, 2011, 5).

In these circumstances, growth has been based on prodigious increases in debt-based spending on services and real estate. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the hotel and restaurant sector grew by 46% in 2010 while construction increased by 36% (UNCTAD, 2011, 2). At the same time, manufacturing decreased by 6% (UNCTAD, 2011, 2). The massive levels of consumer-based debt levels are indicated in figures from the Palestinian Monetary Authority (2011, 13), which show that the amount of bank credit almost doubled from 2008 to May 2010 — from $1.72 billion to $3.37 billion. Much of this involved consumer-based spending on residential real estate, automobile purchases or credit cards — the amount of credit extended for these three sectors increased by a remarkable 245% from 2008 to 2011 (Palestinian Monetary Authority, 2011, 13). These forms of individual consumer and household debt potentially carry deep implications for how people view their capacities for social struggle and their relation to wider society. Increasingly caught in the web of financial relationships, individuals seek to satisfy needs through the market, usually through borrowing money, rather than through collective struggle for social rights. The growth of these financial and debt-based relations thus acts to individualise Palestinian society. It had a conservatising influence over the latter half of the 2000s, with much of the population becoming more concerned with ‘stability’ and the ability to pay off debt rather than the possibility of popular resistance.

New Regional alliances: Israel and the Gulf States

As noted earlier, the impetus for the Oslo signing was strongly connected to the strategic attempt by the US to link its various regional allies into a single economic space, characterised by free trade and investment flows. This goal, however, was deeply shaken by the Arab uprisings that erupted across the Middle East throughout 2010 and 2011. Through their challenge to key regional allies — notably Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak — these uprisings significantly destabilised the patterns of US regional hegemony that had been laid down since the Oslo Accords. In their initial phases, the uprisings represented an important moment of popular hope across the region, embodying a rejection of neoliberal authoritarianism and aspirations for a long sought-after transformation in socio-economic and political rights (Hanieh, 2013). In many ways, these uprisings represented the most significant upsurge of popular mobilisation since the post-war Arab nationalist struggles; the striking manner in which their political and social forms were generalised so rapidly across all states in the Middle East indicated a profound challenge to the regional order that had been extant in the region for the past five decades.

Since this initial phase, Western powers and their regional allies have moved decisively in an attempt to reconstitute state structures and the local bases of support on which their hegemony depends. Despite ongoing struggles, established elites have largely been able to win back political power. Military and state-supported repression was a critical element in this return to the status quo — seen, for example, in the assassinations of Tunisian opposition leaders Chokri Belaid and Mohammed Brahmi in 2013, and the May 2013 military coup in Egypt. Simultaneously, the devastating repression of the Assad regime in Syria and the ongoing disintegration of the Iraqi state helped to spur the growth of sectarian and Islamic fundamentalist movements across the region, further disrupting the social and political goals initially embodied in the uprisings.

Throughout these developments, the long-term aim of Israel’s integration into the Arab world continues to be an important focus of Western policy, despite the popular Arab antipathy towards this goal. In particular, the close relationship between Israel and the Gulf monarchies — notably Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — has become an increasingly open feature of the new regional situation since 2011. This relationship is apparent in joint military exercises, as well as commercial and economic ties in the security, surveillance and high-tech sectors. There have also been public visits to Israel by high-ranking political figures in the Gulf, something that would have been unthinkable a few years ago.

For Palestine, these regional developments are closely interconnected to the processes described earlier. As noted, Palestinian political and economic elites are tightly linked to the Gulf states: the Gulf provides significant financial aid to the PA, and Palestinian capitalists are heavily involved in economic activities in the Gulf (and, in several cases, actually hold Gulf citizenships). There can be little doubt that the leading Gulf states are seeking to formalise their relationship with Israel under US auspices and, within this, the acquiescence of the Palestinian political leadership remains essential. The single major obstacle to this remains the aspirations of the wider Palestinian population — including the millions of Palestinian refugees scattered across the Middle East. Whether Palestinian rights are ultimately subordinated to the interests of this new pan-regional alliance remains an open question; but a political course increasingly directed by Washington, Tel Aviv, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi will undoubtedly provoke major tensions within the Palestinian political project.

Beyond the impasse?

The current cul-de-sac of Palestinian political strategy is inseparable from these regional and domestic political economy dynamics. The two-state strategy embodied in Oslo has produced a Palestinian social class that draws significant benefits from its position atop these processes and its linkages with the structures of occupation. This is the ultimate reason for the PA’s supine political vision, and it means that a central aspect of rebuilding Palestinian resistance must necessarily confront the position of these elites. Over the last few years there have been some encouraging signs on this front, with the emergence of new youth and other protest movements that have taken up the deteriorating economic conditions in the West Bank and explicitly targeted the PA’s role in contributing to them. But as long as the major Palestinian political parties continue to subordinate questions of class to the supposed need for ‘national unity’ it will be difficult for these movements to find a deeper traction.

Moreover, the history of the last two decades shows that the ‘hawks and doves’ model of Israeli politics — so popular in the perfunctory coverage of the corporate media and wholeheartedly shared by the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank — is decidedly false. Force has been the essential mid-wife of ‘peace negotiations’. Indeed, the expansion of settlements, movement restrictions and the permanence of military power have made possible the codification of Israeli control through the Oslo Accords. This is not to deny that real and substantive differences are present between various political forces within Israel; but rather to argue that these exist along a continuum rather than in sharp disjuncture to one another. Violence and negotiations are complementary and mutually-reinforcing aspects of a common political project, shared by all mainstream parties, and both act in tandem to deepen Israeli control over Palestinian life. The last two decades powerfully confirm this fact. The reality of Israeli control today is an outcome of a single process that has necessarily combined violence and the illusion of negotiations as a peaceful alternative. Indeed, the counterposing of a so-called Israeli peace camp and ‘right wing extremists’ acts to obfuscate the centrality of force and colonial control embodied in the political programme of the former.

The reality is that the overriding nature of the last six decades of colonisation in Palestine has been the attempt by successive Israeli governments to divide and fracture the Palestinian people, attempting to destroy a cohesive national identity by separating the Palestinian people from one another. This process is illustrated clearly by the different categories of the Palestinian people: Palestinian refugees, who remain scattered in refugee camps across the region; Palestinians who remained on their land in 1948 and later became citizens of the Israeli state; the fragmentation of the West Bank into isolated cantons; and now the separation of West Bank and Gaza Strip. All of these groups of people constitute the Palestinian nation, but the denial of this unity of the people has been the overriding logic of colonisation since before 1948. Both the Zionist left and right agree with this logic, and have acted in unison to narrow the Palestinian ‘question’ to isolated fragments of the nation as a whole.

Given this arrangement of social forces, any effective renewal of Palestinian political strategy is necessarily bound up with the dynamics of the regional scale as a whole. Those of us living in the UK have a crucial role to play in this process. This means not only supporting campaigns such as BDS but also confronting the complicity of the UK and other governments in sustaining all autocratic and repressive states across the region. As part of this, we must continue to show solidarity with the ongoing struggles for economic, political, and social rights in the Middle East — these have not been extinguished despite the repression of the last few years. Such a spirit of internationalism drove Tom Hurndall’s selfless actions in Palestine, and he will long provide inspiration for all of us concerned with seeing real justice achieved.

Bibliography

Bartram, D. V., ‘Foreign Workers in Israel: History and Theory’, International Migration Review 32, 2 (1998), 303–25.

Bouillon, M. E., The Peace Business: Money and Power in the Palestine-Israel Conflict (London: I.B. Taurus, 2006).

Brusilovsky, H. and Gitelson, N., Israel’s Foreign Trade 2000–2010 (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 2011).

Farsakh, L. Palestinian Labour Migration to Israel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

Graham-Brown, S., ‘Agriculture and Labour Transformation in Palestine’, in Glavanis, K. and Glavanis, P. (eds), The Rural Middle East: Peasant Lives and Modes of Production (London: Zed Books, 1990), pp. 53–69.

Hanieh, A., Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East (Chicago: Haymarket, 2013).

Honig-Parnass, T., The False Prophets of Peace: Liberal Zionism and the Struggle for Palestine (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011).

Machover, M., Israelis and Palestinians: Conflict and Resolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012).

Nitzan, J. and Bichler, S., The Global Political Economy of Israel (London: Pluto Press, 2002).

Palestinian Monetary Authority, Monthly Statistical Bulletin, May. Ramallah, 2011.

Pappe, I., The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (London: Oneworld Publications, 2006).

Retzky, A., ‘Peace in the Middle East: What Does It Really Mean for Israeli Business?’, Columbia Journal of World Business 30, 3 (1995), 26–32.

Said, E., ‘The Morning After’ London Review of Books, 15, 20 (21 October 1993), https://www.lrb.co.uk/v15/n20/edward-said/the-morning-after.

Samara, A., The Political Economy of the West Bank 1967–1987: From Peripheralization to Development (London: Khamsin Publications, 1988).

UNCTAD, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Report on UNCTAD Assistance to the Palestinian People: Developments in the Economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, July 15 (Geneva: UNCTAD, 2011).

World Bank, ‘Trade Options for the Palestinian Economy’, Working Paper no. 21, 2001, https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-197986/.

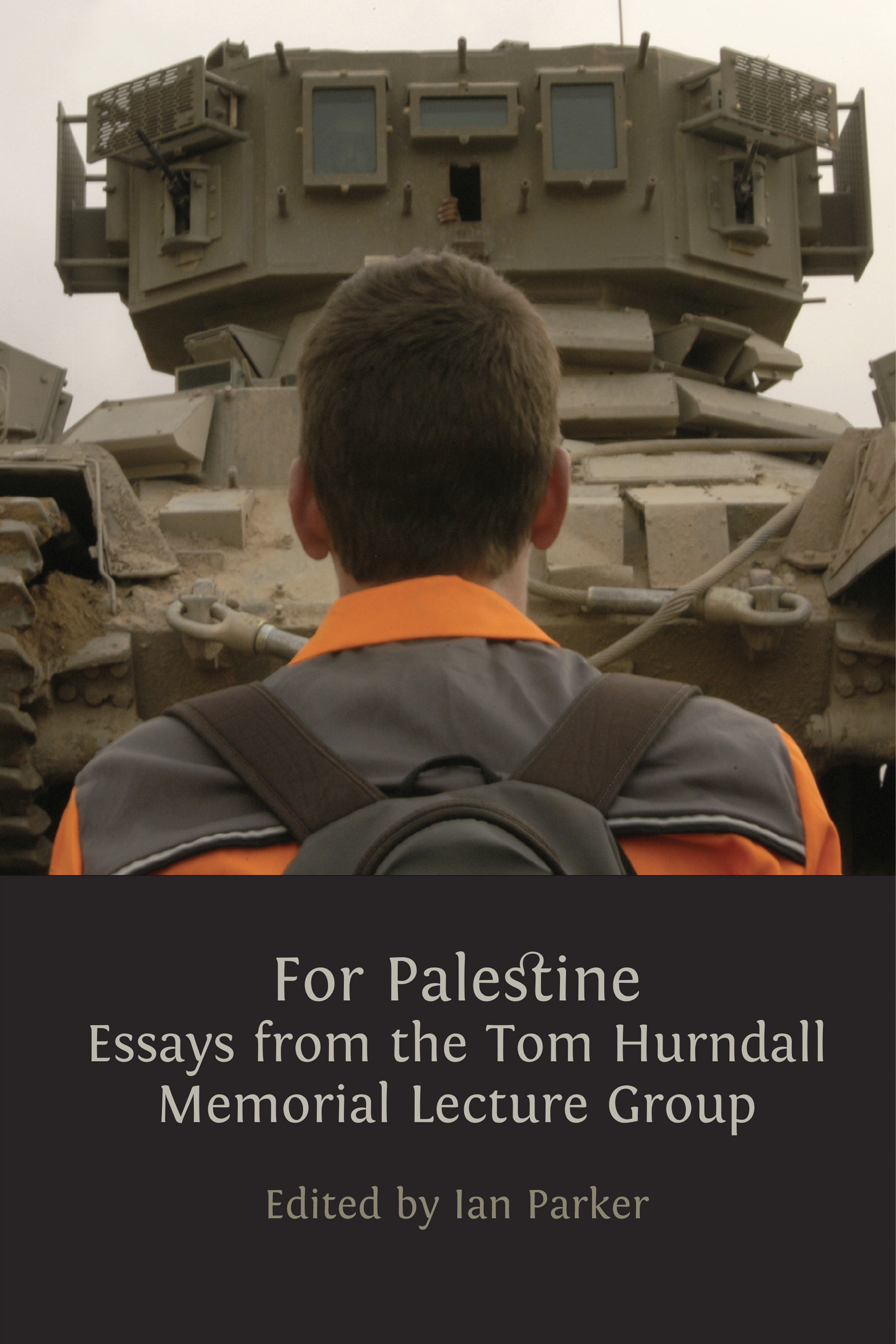

Fig. 14 Tom Hurndall, ISM volunteer in front of an Israeli APC at the Rafah border, April 2003. All rights reserved.

1 The text of this chapter draws upon two previously published works by the author: ‘The Oslo Illusion’, Jacobin Magazine, 21 April 2013, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2013/04/the-oslo-illusion/ and Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013).

2 The other component to this was the transformation of the PLO into an apparatus dependent upon the support of other Arab governments and funding from the Gulf region. The PLO’s isolation following its backing of Saddam Hussein in the 1990–1991 war also played a major role in its support for the Oslo process.

3 For the Labour and GDP figures see Farsakh (2005, 41–42; 98). It should be emphasised that population figures in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are somewhat suspect given that, until 1997, the only census conducted in the area was one performed by the Israeli military in 1967 immediately after the occupation began.

4 PCBS―Total Value of Exports from Remaining West Bank and Gaza Strip by Country of Destination and SITC. Total Value of Imports for Remaining West Bank and Gaza Strip by Country of Origin and SITC, 2005. This dependency was only to increase with time.

5 The Paris Protocol was signed in 1994 and gave precise expectations of which goods Palestinians were allowed to export and import, as well as tax regulations and other economic issues.