13. Resisting Cybercide, Strengthening Solidarity: Standing up to Israel’s Digital Occupation

© 2023 Miriyam Aouragh, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345.14

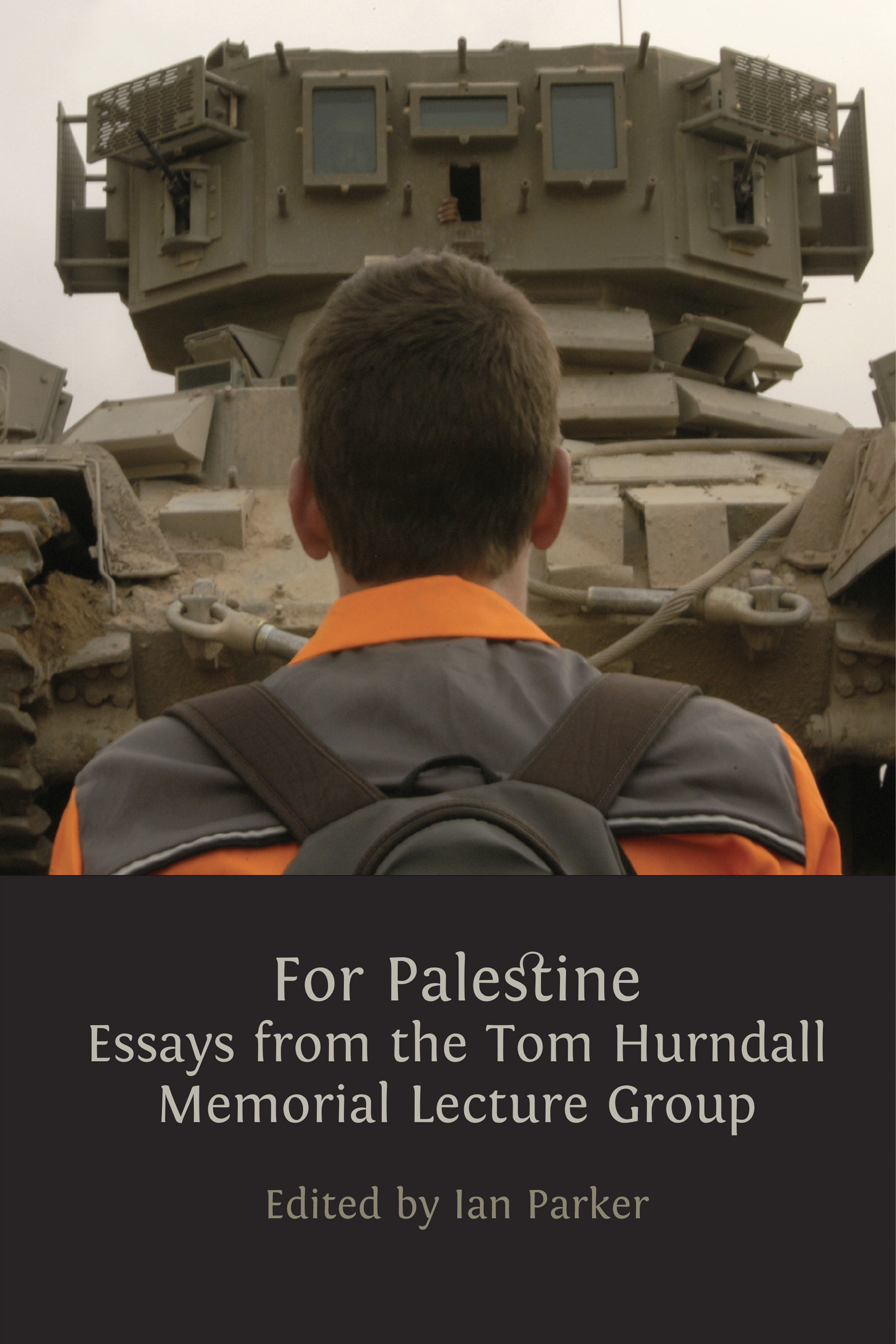

Over the years, the political impact of digital media as tools for ‘citizen journalists’ has grown substantially. It is this arena that Tom Hurndall was navigating with his photo journalism, bearing witness to the destruction, occupation and resistance in Palestine. In the years since the Second Intifada (2000–2005), we have seen digital technologies become a key tool for solidarity groups across the world.

Mainstream media have come to function as gatekeepers by determining what stories are aired or properly contextualised. Thus, the Internet has influenced Palestinian politics by disseminating textual, visual, and audio narratives beyond the confines of censorship of commercial media and political elites. More than a decade later, the Internet has by now grown into a counter-public space for Palestinian liberation politics.

The relationship between technology and politics is multivalent and in contrast to a technologically deterministic view, reality is messy. Political change ultimately must emerge from human decisions and practices, themselves based on historical conditions. This implies great contradictions and therefore requires a nuanced approach. The Israeli state and its international supporters deploy the same technologies for instance. In fact, they have a far greater advantage than Palestinians. There are two sides to this, simply put, the material and the immaterial. The immaterial is found for instance in the effort to mobilise pro-Israel sentiments. I have discussed this Israeli public diplomacy through social media as a form of Hasbara 2.0 (Aouragh, 2016). The material side has to do with the warfare and surveillance — the destruction and violence so to speak — which I have framed as Cybercide (Aouragh, 2015).

I will return to this later. But first, if we agree that social media has affected the basic algorithms of resistance, we need to contextualise this resistance and media. Media and information studies researchers can benefit from historians of European and US Empire who have documented the ways in which Western technological advances are often based on particularly violent experiments in warfare and of counter-insurgency developed in the Third World. Rashid Khalidi (2006) writes about French and British air bombardments, and this became the basic knowledge for textbooks on aerial bombardments. It was indeed in the early postcolonial era, across the Third World, when the village and slum became a social laboratory for research. That is not all; the idea of individual rights associated with access to media and information technologies was part of the tightening grip of postcolonial states in regulating media and information. For this to become clear, we need to relate to the political-economic context, for Information and Communication Technologies, ICTs, are not operating in an immune field or vacuum.

Technology as a commodity (infrastructures) and as capital accumulators (ownership, profit) are protected through an inherited inequality between North and South. This meant a late and very uneven development of post-independent states’ own infrastructures. Neoliberal multinationals (e.g. ‘public private partnerships’) are state-protected corporations that can behave like cyber Gods, like anonymous entities they can for instance allocate URL (Uniform Resource Locator) names, refuse political website addresses, and under the guise of national security or privacy laws some nations are rejected while others are included. Palestine is a case in point. In the case of finding a generic URL-based naming system, it took Palestinians many years of negotiation (and pleading) to get the Internet country code top-level domain — the sovereign .ps domain — assigned.

Thus we have here a combined problem of being bound by neoliberal rules in the ICT sector at large, while being disadvantaged by a forced, uneven inheritance of colonial infrastructures. This political economic approach helps to demystify the diffusion of technologies and instead to frame them as part and parcel of the expansion of capitalist market systems and geopolitical interests. This is nowhere as clear as in Palestine. But the struggles against occupation must be situated within the structure of settler colonialism for, as scholars have argued, Palestine is not colonised in the ‘common sense’ of the word (Salamanca et al., 2012). Palestine, both in its abstract sense as a nation and as a territory in the concrete physical reality, faces colonial subjugation. This is motivated by the need to empty the land of its inhabitants, rather than ‘civilising’ the people as part of the pretext to extract the land and exploit the people.

But what does this mean concretely for online politics? On the most basic level, it means that technology has been part of the underlying reality within which Palestinian resistance operates. In other words, the Palestinian political landscape mediates between settler colonialism and cyber-colonialism.

Cyber-colonialism

The Internet had become increasingly incorporated into Israeli military strategies — prohibiting, removing, and destroying the Palestinian Internet. This is regarded as the (uglier) façade of the more latent hasbara policies, a destructive condition that I began to understand in connection with what was termed Israeli politicide by Baruch Kimmerling (2003).

This cybercide is intimately embedded in military procedures: employing the Internet is not a random move. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector itself is part of the military industrial complex. The urge to control the politics of mediation while simultaneously conducting cyber warfare was most clearly seen for the first time during the July 2006 war on Lebanon. Two and a half years later, Israel organised the military invasion of Gaza (Operation Cast Lead) — one of the bloodiest to that date in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) — where its Internet skills were significantly stronger. Then it took even further measures when it stormed the Mavi Marmara (one of the solidarity flotilla ships sailing toward Gaza carrying tonnes of aid) on 31 May 2010. In a sense, this was a tipping-point. Israeli paratroopers were dropped on the ship from their helicopters, they confiscated laptops and mobile phones from activists aboard the ship. Israel had already tried to block cellular and radio communication. An outcry was expected and therefore it was imperative to limit the impact of the killing of unarmed civilians in international waters. Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca Stein analysed the Israeli military tactics during the attack on the Mavi Marmara flotilla (Kuntsman and Stein, 2015). And what is interesting about this case is that one of the passengers had managed to smuggle out a digital tape of the first moments of the attack. Once out of the country, the footage was uploaded online, and a different version of what had happened appeared, one that refuted the ‘self-defence’ rationale underlying Israel’s versions.

It is important to understand the relationship between the Internet and politics through on-the-ground practices. When we expose the economic and territorial structures that shape and negate Palestinian resistance, tangible frustrations of Palestinian cyber-activists become clear. This is why we should always relate back to settler colonialism as a dynamic and multi-layered phenomenon, which includes online and offline features and is both political and economic. This is the case with what can be called ‘cyber-colonialism’.

Throughout the past twenty years, the Israeli army has jammed and hacked telephones, Internet, and broadcast signals. Occupation forces have destroyed infrastructure almost continuously, the Israeli army intentionally and repeatedly severs the only landline connection between southern and northern Gaza and has dug up cyber-optic cables in the West Bank, or uprooted transmission towers.

The challenge of Palestinian activism is therefore equally dynamic and multi-layered. It entails manoeuvring between online and offline organising as well as attempting to circumvent crackdowns on those practices, as when the Israeli army engages in acts of cybercide by destroying hardware, bombing broadcasting stations, ransacking IT forms and even via remote-control killings of Palestinian protesters.

During fieldwork in Palestine in 2012 the Stop the Wall office was raided by the Israeli military: computers, hard disks, and memory cards were stolen. Not much later, Israeli soldiers confiscated the computer of Addameer, a prisoners’ and human rights organisation. As a consequence, activists and everyday users alike are well aware that the Internet is constrained by Israeli military, economic, and ‘security’ policies. Among Palestinians there is widespread awareness that their Internet usage is under surveillance. Israeli security forces have used confiscated personal communications to blackmail others into collaboration. This threat constantly hangs like a Damocles Sword above the computer screens of activists. The Internet is used at one’s own risk due to a combined impact of surveillance and intimidation.

The difference between the Internet as a space in which to mobilise solidarity and as a tool by which to organise protest is starker than anywhere else, predominantly because Palestinian infrastructures are so clearly compromised. Although used efficiently for international mobilisation, it is noticeable that the Internet is not the primary tool for persuasion — other spheres and mediums such as satellite television, mosque announcements, university campus gatherings, and posters are often as important to fulfil this need.

Therefore, to be relevant for Palestinian activism, online politics must facilitate offline mobilisation and long-term strategies. Grassroots campaigns demonstrate that the Internet has empowering characteristics and is significant for activism. However, this is precisely why they are also violently targeted and their equipment destroyed during raids. In other words, the disempowering materiality of technology shapes that very empowering activism.

Thus, cyber-colonialism functions through a double-layered mechanism, involving overt and covert control, and combines latent and manifest methods, and is concluded by a politics of controlling, altering, and deleting. The relationship is dialectical: the implication of the online must always be addressed by what it means offline. Within the Palestinian realm today, offline activism is marked by colonialism on the one hand and an oppressive internal authority (Palestinian National Authority) on the other. Does this mean that Palestinian resistance will always be the weaker party?

Meticulous Strategy, Magnificent Failure

For Palestinians, cybercide and especially hasbara (Israeli state propaganda) mediates not only the exercise of power over life and death, but over truth itself. It is difficult to mask images of conflict when one perpetually is involved in wars. The underlying truth of colonialism, obscured by an ideological bias, does not allow hasbara to arrive at the most logical explanation that would be in tune with most public relations approaches or media analyses. However, the overall impact of the Palestinians on social media outweighs that of Israel, defying the mathematical logic that one might presume applies. That an opponent with more resources, superior access to intelligence and crucial international backing is not able fully to impose its will is an important confirmation of the efforts of activism and power of solidarity.

It is important to remember that the grassroots struggle against Apartheid South Africa took many decades; without all of the initial cracks in the projection of white supremacy by solidarity groups both big and small around the world, a collective that managed to pressure international governments to end their diplomatic and economic support for South Africa would not have emerged.

The lacuna between Israel’s desired public persona and its actual international perception continues to deepen, and pro-Palestinian movements are gaining public support. There is a parallel common sense seeping through, one that defies many of hasbara’s attempts to ‘explain’ it all away. This ‘common sense’ is captured by the words chanted in the streets of many capitals across the world in July and August 2014: ‘In our thousands — in our millions — we are all Palestinians.’ This striking chant proclaims that (pro-)Palestinian public diplomacy, which clearly does not rely on government interventions, is an international people’s objective. The basic fact, therefore, is that every time Israeli propaganda becomes more masterful in its techniques and receives more budgets, it ends in disappointment. Paradoxically, grassroots diplomacy — a public relations that is formed by universal principles of justice and equality — offers qualities that money cannot buy.

One of those qualities was Tom Hurndall. The Palestinian cause and its great ‘sumud’ and courageous resistance had become visible for a new generation during the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Palestinians sparked hope and rebellion, and they inspired Tom. He in turn represented a peaceful and strong humanity which continued to inspire many of us when we heard of his tragic end, fatally wounded by the Israel Defence Forces whilst protecting Palestinian children in Gaza. He died on 13 January 2004. This was my message at the time.

Dear family and friends of Tom,

Despite nine months in a coma, Tom’s death took us by surprise. It left us in a moment of retreat. Stunned while staring at the television screen. Upon hearing the news of his passing, many thoughts crossed my mind. I am sure that others felt similar emotions, ranging from anger to sadness and settling on renewed determination.

Tom’s death was the result of a cowardly act. Of viciousness. Itself the result of an entrenched racist and oppressive system. Tom’s killing revealed not only the mercilessness of the tactics used by the Israeli army, but also disclosed the hypocrisy and compliance of our own Western governments.

Tom symbolized the peaceful, yet at the same time strong, will of humanity. That is more than can be said of the many “Coalition Forces” army casualties in Iraq who receive elaborate memorials and media coverage. We remember the double standard when an Israeli bulldozer crushed the young American peace activist Rachel Corrie to death in Gaza. Not long after that dark day in March, all media spotlights and patriotic rhetoric were focused on another young American woman: Private First Class Jessica Lynch, an injured war heroine ‘rescued’ by Special Forces in an aura of Hollywood style triumphalism. Not yet a year since her ordeal, Ms. Lynch has already been featured as the subject of books, a made-for-t.v. movie, and several nationally broadcast interviews.

This tragedy reminds us of the Orwellian axiom that ‘Who controls the present controls the past, and who controls the past can control the future.’ As we gaze at our television screens, we see how chillingly accurate this formula is when Israeli spokespersons change the logic of language by redefining a permanent apartheid wall as a ‘terror prevention fence’. Most of the peace activists currently in Palestine are doing all they can to resist that wall. And they should, because it is like a poisonous snake that slowly penetrates, encircles, strangles and then swallows what is left of Palestine.

Fatalist though it may sound, given the current political realities it is just a matter of time before the next victim, another Tom Hurndall or Rachel Corrie, or an Israeli protestor, will fall (and be commemorated by us) while resisting that snake in disguise. And it is inevitable, too, that the next person killed by the Israeli Army will be blamed for their own death in the mainstream media. The ruling ideas are indeed the ideas of the ruling class.

Yet, times are changing. The thick wall of ideological domination, protected by military supremacy, which separates us from what could be a better world is starting to show cracks. Not only does the dissemination of alternative information through the Internet and satellite television give us a voice and thus a tool to organize, modern mass media are also enabling millions of people throughout the world to become organized and to actively take to the streets, motivated by an international level of solidarity never before seen. Tom was certainly a key player in this new global politics.

The struggle for justice would be stronger if Tom were still with us. But I believe that his selfless actions and the ultimate price he paid sparked a desire to know, struggle, act; to help bring about a revolution in perception and action concerning Palestine.

We don’t need elaborate memorials or long speeches from the same establishments that continue to back Israel and provide it with the very weapons and bulldozers that cause death and destruction. What we do need is hope and will to make a difference.

One can only feel astonishment at the bald contradictions and injustices of the current world order, and horror at the astronomical prices that must be paid to support this unbalanced system. The latest bill for maintaining power in Iraq, after a war that was based on lies and deceptions, is illustrative. For a war that only ideologically deranged neocons [neoconservatives] and corporate interests are still willing to defend, Bush needs an extra $86 billion just to hang on. At the same time, we live in a world where 799 million people suffer from famine; 115 million children can’t afford to go to school; more than 30,000 people die from hunger and poverty-related disease every single day. The UN estimates that $9 billion are needed to provide basic education for all the worlds’ children and $36 billion to provide clean water and basic healthcare for all.

While gazing at the news of Tom’s death, and looking at the picture of his gentle face again, it became clearer than ever before that the priorities of Bush, Blair, and Sharon are anything but the priorities of ordinary people trying to make a living and to live in peace. Since the result of these global contradictions will be increasing political instability on a global scale, priorities must be set with regard to our own individual choices. Indeed, it is not enough merely to analyze the world, the challenge ‘is to change it’ as Marx observed over 150 years ago. Although it won’t be easy we will have to make our own history.

Tom made a choice; Tom made history. It is people like him, Rachel, and many others who personify a new generation unwilling to blindly accept the world as it is, but who instead take risks and work together to forge new protest movements. People like Tom actively helped to universalize the Palestinian struggle, who together with millions of others in Washington, London, Paris, Genoa, Porto Allegre, Cairo and Ramallah showed that the Palestinian flag can become a symbol that binds us together. As the late Edward Said said, Palestinians by themselves cannot defeat Zionism and its US backers.

To pay tribute to the many Toms and Rachels of Britain, to Gaza, Jerusalem or Shatila camp, I conclude by saying to those who have been taken from us: ‘You will never be forgotten and we will complete what you started.’ And to all those still fighting I say ‘We are with and beside you, no matter what.’ And to all those who are not yet part of the struggle for justice, I implore: ‘Join the struggle, because united we will stand and divided we shall fall.’

I hope that on the coming international anti-war day planned for 20 March 2004 in all major cities around the world, that pictures of Tom, Rachel and so many other heroes — people who made history by making choices — will be carried in our hearts, minds, and on our banners.

With comradely, loving, and respectful feelings,

Miriyam Aouragh

Bibliography

Aouragh, M., ‘Between Cybercide and Cyber Intifada: Technologic (dis-) Empowerment of Palestinian Activism’, in: Jayyusi, L., & Roald, A. S. (eds), Media and Political Contestation in the Contemporary Arab World: A Decade of Change (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 129–60, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137539076_6.

Aouragh, M., ‘Hasbara 2.0: Israel’s Public Diplomacy in the Digital Age’, Middle East Critique, 25:3 (2016), 271–97, https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2016.1179432.

Kimmerling, B., Politicide: Ariel Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians (London: Verso, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2005.104.678.25.

Khalidi, R., The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006).

Kuntsman, A. and Stein, R.L., Digital Militarism: Israel’s Occupation in the Social Media Age (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804794978.

Salamanca, O.J., Mezna Qato, M., Rabie, K. and Samour, S., ‘Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine’. Settler Colonial Studies 2.1 (2012), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473x.2012.10648823.

Fig. 16 Tom Hurndall, ISM volunteer in the street on the Rafah border with IDF vehicle, April 2003. All rights reserved.