14. Israel’s Nation-State Law and Its Consequences for Palestinians

I will take this opportunity to discuss Israel’s nation-state law, passed in July 2018. Firstly, I will outline what the law says and what its effects are. Secondly, I will suggest that the law establishes Israel as an ethnocratic, as opposed to a democratic, state, that the law is in violation of international law, and that it paves the way for Israel to practice apartheid. Finally, I will examine the political context in which the law was passed and argue that, whilst the law is fundamentally a misguided attempt by Israel to respond to a crisis of legitimacy, it must be resisted as it represents an entrenchment of Israel’s discriminatory regime against Palestinians, and contributes to the erosion of Palestinian rights.

Israel’s Nation-State Law

On the 19 July 2018, the Israeli Knesset passed the ‘Basic Law: Israel — The Nation-State of the Jewish People’ (‘the nation-state law’). The document is here: https://m.knesset.gov.il/EN/activity/documents/BasicLawsPDF/BasicLawNationState.pdf. The law contains the following provisions:

- the ‘Land of Israel’ known as ‘Eretz Israel’ is the historical homeland of the Jewish people;

- the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people, and the realisation of national self-determination in the State of Israel will be exclusive to the Jewish people;

- immigration leading to automatic citizenship is exclusive to Jews;

- ‘Greater and united Jerusalem’ is the capital of Israel;

- Hebrew is the official language of the state, and Arabic will have special status;

- the state will act to encourage, consolidate and promote Jewish settlement, and the state will work to foster ties with Diaspora Jewry.

The Constitutional Status of the Nation-State Law

The nation-state law is a constitutional law which determines the way the state of Israel is defined. In particular, the law determines the identity of the political community that constitutes the locus of sovereignty of the state — that is the people that the state is meant to serve and to represent — as well as defining the aspirations and visions of that political community, and its cultural identity (in terms of language, religion and symbols). It also determines how all other laws, policies and practices of the state must be interpreted and applied.

Confirming the law’s constitutional status, a report commissioned by the Israeli Justice Minister in 2015 into the implications of the nation-state law concluded that the law was not merely declaratory — grounding into law already-existing policies and practices of the state, as had been argued — but that it amounted to a ‘constitutional anchoring of the vision of the state’. As a result, the report advised against the enactment of the law because it was obvious to the author that such constitutional anchoring should only be done in the framework of constitutional politics, and when it enjoys the support of a large sector of society. By contrast, the report noted that such a process had not taken place in Israel at the time the law was proposed, and therefore recommended against the law.

The Nation State Law Makes Israel an Ethnocracy

Let us now look at the law’s provisions in more detail. The law stipulates in Article 1:

(a) The Land of Israel (Eretz Israel) is the historical homeland of the Jewish people, in which the State of Israel was established;

(b) The State of Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination;

(c) The realization of the right to national self-determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish people.

In defining the state of Israel as the ‘nation-state of the Jewish people’ alone, and stating that the Jewish people have an exclusive right to self-determination, the law provides that the political community that the state serves and represents, is one ethno-national group only — the Jewish people — as opposed to all the national groups or persons residing in the territory subject to the state’s constitutional order.

A comparative study commissioned by the Knesset found that there is currently no constitution in the world that appropriates the state exclusively for one ethnic group. Rather, constitutions generally adopt one of two ways of dealing with different ethnic groups within the territory of the state: the first is to define the political community of the state as containing the main national groups who are specifically recognised; the second relies on a territorial nation-state model, where the sovereign is defined as comprising all the residents of the territory of the state.

The fact that the nation-state law provides that Israel is the nation state of only one of the national groups within its territory, and establishes Israel as an ‘ethnocracy’ rather than as a democracy, it would be tantamount to, for example, Britain defining itself not as the state of the British people, but as the state of ‘the whites or ‘the Christians’.

Furthermore, it is clear that the ethnocratic effect of the law is deliberate. During the drafting of the law, the legal advisor to the Knesset put forward an alternative proposal, which would have included the principle of equality and a provision that the state belonged to all of its citizens. The proposal was explicitly rejected by Knesset members. The Knesset’s legal advisor explained after the law was passed, ‘We […] recommended during the discussions in the committee that it would have been appropriate, as has been done in other constitutions, [that] alongside the mention of the Jewish nation there be a mention of the issue of equality and the issue of the state belonging to all citizens, [but] the committee chose not to make this into a law.’

The Law Ensures Exclusive Jewish Self-Determination and May Amount to Annexation

Article 1 of the law also provides that Jews have an exclusive right to self-determination in the land of Israel. Therefore, it denies any right of self-determination to Palestinians in the same country.

Furthermore, although the law does not explicitly define the territory of the state of Israel, it refers both to ‘Eretz Israel’ (Greater Israel which encompasses the whole territory of Mandate Palestine) and to ‘the State of Israel’ without distinguishing between the two. This means the law may be interpreted as applying both in Israel within the ‘Green Line’ (‘Israel proper’), as well as in the occupied Palestinian territories and if this is correct, the law could amount to an act of annexation.

How the Nation-State Law Violates International Law

Having looked at the provisions of the law in more detail, we are now in a position to analyse the ways in which the law can be said to be in violation of international law.

Firstly, the law is in conflict with international human rights law. The latter provides that all persons have a right to equality, and to be free from discrimination on ethnic, national, racial or religious grounds, and, furthermore, that states have a duty to treat equally all individuals within their territory or subject to their jurisdiction. The nation-state law, because it defines the Jewish people as the only ethnonational group represented by, and therefore served by, the state, effectively mandates the unequal treatment of Jews and Palestinians by the state. Indeed, the law provides that many state functions are reserved exclusively for the benefit of Jews such as, for example, Jewish settlement and citizenship and, therefore, rights to nationality and land. By contrast, Palestinian rights are not mentioned in spite of the fact that they make up roughly 50% of the population of the territory which Israel controls. Thus the law breaches the obligation contained in international human rights law of non-discrimination and equality of treatment.

Secondly, the law violates the Palestinian right to self-determination in that it reserves self-determination rights exclusively to Jews. International law has recognised that Palestinians have a right to self-determination through the creation of an independent state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and that all peoples, generally, have a right to self-determination, with no one nation having a right to rule over another. The nation-state law violates international law through these principles by providing that the self-determination of Jews is an exclusive right.

Finally, the law creates the foundation for the practice of apartheid in Israel. Apartheid is defined as the perpetration of inhumane acts, as part of an institutionalised regime of racial discrimination, which has the purpose of ensuring the domination of one racial group over another. Many commentators have suggested that the discriminatory policies and practices of Israel, which include the indefinite occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the fifty or so laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel, and the policy of denying nationality and the right of return to expelled Palestinian refugees whilst promoting Jewish emigration to and citizenship of Israel, mean that Israel is already a state that practices apartheid. However, the nation-state law effectively elevates the supremacy of Jews over other ethnic groups in Palestine to a constitutional value, establishing a legal framework for the practice of apartheid.

The Broader Context

All of this begs the questions: why was the nation-state law passed, and how does it fit into the broader political context?

There is no doubt that Trump’s presidency in the US emboldened Israel to pursue its most extreme agenda. Indeed, the nation-state law was passed in the context of the acceleration of other Israeli policies which all, in one way or another, have sought to extinguish the main demands of the Palestinian national movement, and thus to ensure the supremacy of Jewish nationalist aspirations in Israel/Palestine. These polices include expanding settlements in the E1 area of the West Bank, thereby ensuring a lack of territorial contiguity of a future Palestinian state, solidifying the Jewish presence in Jerusalem to ensure that the city cannot act as a future capital of Palestine, and pressuring UNRWA (the UN’s Palestinian refugee agency) to stop defining the descendants of expelled Palestinians as refugees with a right of return to their homes in what is now Israel.

However, it is also important to understand the passing of the nation-state law as a response to a crisis of legitimacy that Israel correctly perceives itself to be suffering from, both domestically and internationally.

This crisis of legitimacy is caused, firstly, by Israel’s continued colonisation of Palestinian land and the failure to bring about a two-state solution. This has created a situation on the ground in which Israel controls all of the territory of Mandate Palestine, a territory inhabited by approximately equal numbers of Palestinians and Jews, but in which Palestinians are denied all or most of their human rights. This unacceptable situation, which many commentators consider to amount to apartheid, presents a clear challenge to Israel’s legitimacy, as well as threatening Israel’s viability in practice as an exclusively Jewish state.

Secondly, civil society activism, and in particular the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement, have successfully raised awareness of Israel’s crimes and violations of international law, eroding Israel’s legitimacy in the international arena and causing ever-more vocal calls for Israel to either transform itself into a state for all of its citizens, or to give up its rule of occupied Palestinian territory, thus enabling a Palestinian state to emerge.

I believe that Israel is keenly aware of the contradictory position into which its policies have placed it, and which means it cannot be a democracy with international legitimacy, while at the same time presiding over an apartheid reality on the ground. I believe that Israel has responded to this paradoxical situation by passing the nation-state law. It is as if Israel’s leaders believe that by codifying Israel’s exclusively Jewish character into law, this will help stem the threat to the Jewish character of the state, as well as somehow putting a stop to the legitimacy crisis that Israel faces.

Conclusion

The nation-state law establishes Israel as an ethnocracy as opposed to a democracy. It entrenches Israel’s discriminatory regime, and it supresses the Palestinian right to self-determination. The law will undoubtedly contribute to the further erosion of Palestinian rights. It is important for those who care about the Palestinian cause to understand what the nation-state law represents, and to help Palestinians resist it by advocating for the international community to take action to bring an end to Israel’s discriminatory policies and practices.

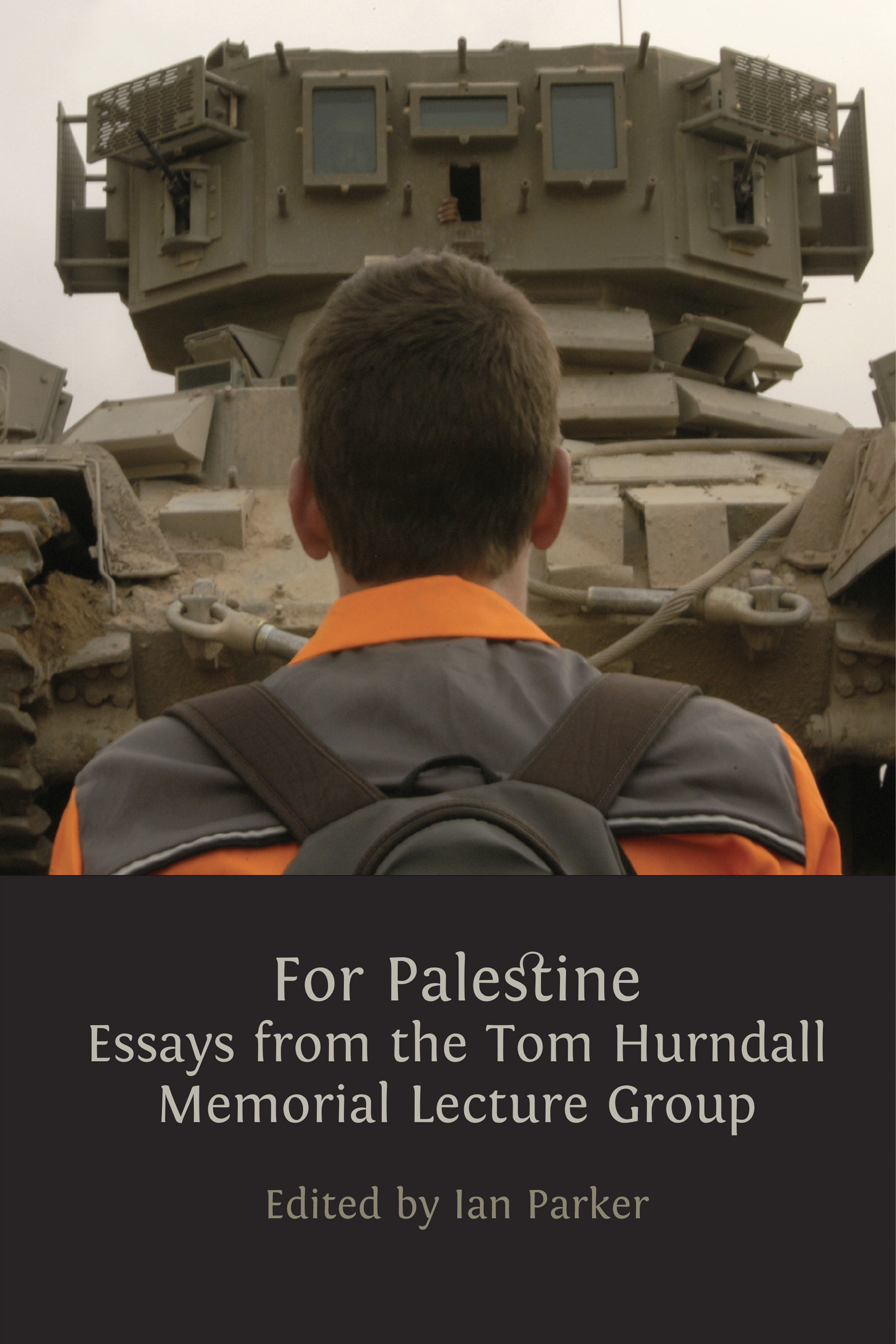

Fig. 17 Tom Hurndall, Flags burnt at funeral for Palestinian killed in an Israeli airstrike, April 2003. All rights reserved.