15. The Crafting of the News: The British Media and the Israel-Palestine Question1

I want to start by saying two basic things to map out my thesis, if you like, about the British media coverage, particularly the broadcasting media coverage of the Israel/Palestine question over the past forty years or so. The first thing I want to say is that journalism is not a perfect art, a perfect form. News editors are faced everyday with myriad stories. They have to make instant judgements, important stories fall by the wayside and are ignored. Many other things operate to take our interest, which is in Palestine and Israel, out of focus for a while. But the main point I want to make is that when the story is covered, as it is from time to time now, and as it used to be more consistently, it should be covered properly.

And my case is that over the past twenty years now, the BBC particularly, but the other broadcast media as well, and to some extent, newspapers which had been sympathetic to the Palestinian cause or Palestinian legitimate aspirations for equal rights, have not done the job properly. As to the BBC, I say this not because I am anti-BBC, and not because I’m a resentful ex-employee. I still admire the BBC. And I think the institution should remain. But it does not do the Israel/Palestine job properly. It listens to the voices of government and it takes into account the voices of pressure groups instead of listening to public opinion, which as we know, steadily over the past twenty-five years or so, has moved away from open support of Israel and taken, especially in Britain and in Western Europe, the Palestinian cause seriously.

History

That’s my basic thesis. I want to go back now a little bit into the history of this whole affair. In the 1950s and ’60s, the Palestinian identity had more or less disappeared from the public discourse outside the world of the Palestinian Arabs themselves. The word just was not used. It was not an issue. After 1948, unfortunately, the Palestinian Arabs, the refugees, the ones still hanging on in Israel, those treated as second- and third-rate citizens, were regarded as Arabs, Arab refugees. They were not called Palestinians and there was no Palestinian cause as such that we heard about in the West. The media coverage of the Middle East in those days, in the fifties and the sixties, was very much a coverage of Israel against the Arabs. Plucky little Israel fighting off the great hordes of the Arab masses, who were, we were led to believe, about to descend on plucky little Israel and eliminate it at any moment, if they were given half a chance.

This was of course exacerbated by the West’s relationship with Gamal Abdel Nasser, the great foe, the great fear in the media and in government circles in the West, especially after what happened, the Suez crisis, was Arab nationalism. The governments in the West chose to see Arab nationalism not as a legitimate enterprise in itself, which it obviously was, but as an arm of some kind of global Soviet-inspired revolution. In the American view, it came under the heading of the Eisenhower Doctrine, you were either with us or against us. And because Nasser’s Egypt and Syria, and after 1958, Iraq, were countries that in their different ways were backing Arab nationalism, the Arabs were seen vaguely as troublesome and possibly pro-Soviet.

These are very broad brushstrokes, but that was the way the Western media, and the BBC included, tended to see it. In 1956, for instance, the Guardian was against the Suez conspiracy between Britain, France and Israel to attack Egypt. The Guardian and those who opposed the conspiracy, including the Leader of the Opposition, Hugh Gaitskell, whose opposition speech was controversially carried by the BBC, chose to take as the object of criticism the British and the French. Israel very largely escaped criticism. As someone who wrote a book about the Guardian at the time said, The Guardian was more interested in saving Israel from itself than actually criticising Israel. The Guardian, by the way, had a long history of involvement with Zionism. CP Scott, the legendary editor of the Guardian, the Manchester Guardian, as it then was, Manchester being a strong centre of British Jewry, British Jewish art, business, industry and influence, was very close to the Zionists. And in fact, he was the one who befriended Chaim Weizmann and introduced him to the prime minister of the day, Lloyd George. CP Scott played a big part in pushing the Zionist case in Britain at a crucial time.

However, that is the broad look of the British coverage of the region at the time. No Palestinians, but Arabs, deeply suspect for being possibly pro-Soviet. That was really the way in which the coverage was delineated. It was very much part of the Cold War attitude.

Broadly the Palestinians weren’t getting a look in. Palestinian nationalism itself, though, was beginning to emerge inside the Middle East, in Kuwait. Yasser Arafat had created Fatah in 1959. In 1963 or ‘64, the PLO had been created very much under the Egyptian umbrella. Yasser Arafat didn’t take it over until the mid-sixties. The seeds of Palestinian nationalism were being sewn but they weren’t being shown in the media.

Another big problem for the media in those days was in Israel itself, and this was true, well after the ‘67 War, when things began to change. Most of the operators there, most of the journalists in Israel were residents of Israel. Many of them were Jewish Most of them actually were Jewish. Many of them were Jewish residents of Israel, if not citizens of Israel. The BBC correspondent from 1967 onwards, for another fifteen years or so, was an excellent correspondent called Michael Elkins, but he was definitely a Zionist. He was a man who had gone to Israel to escape persecution in America of allegations that he was a communist. His heart was in Israel. His family were in Israel. He believed in Israel. He was an excellent reporter on Israel. But like many of his colleagues, he did not, even after 1967, spend much time in the West Bank and had no great empathy for it. He reported Israel and did it very well. And I think this was true of many of the other reporters that the major British media relied on.

1967 changed everything, of course. In 1967, the Israelis occupied the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights. They annexed later on East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, and they still hold onto and threaten to annex most of the West Bank. And of course they still occupy Gaza in the sense that they are responsible for it, although it’s under a dreadful siege.

The point was, this was in a sense, a terrible mistake for the Israelis because when they invaded the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, what they did was they brought to the attention of the world a problem which had lain fallow since 1948 and the world began to pay attention to the fact that there were such things as Palestinians, that there was a Palestinian nationalism and that it was a force to be reckoned with.

Now, at first, it didn’t get off the ground very well. I want to give you some examples of the way the British media particularly, and the BBC, ignored this, or rather, didn’t ignore but slighted this fateful position that the Palestinians were in. Reporters started to go to the West Bank from Jerusalem and from London. And to give you one example, one of my great heroes was a doyen of Middle East reporting in the sixties. He had been on the staff of the Guardian but by now he was a freelance. His name was Michael Adams. His son is Paul Adams, who now is a diplomatic correspondent for the BBC and is himself an expert on the area. Michael Adams went to the West Bank in 1968 to have a proper look at the way in which the Arabs and the Palestinians were being treated. And he didn’t like what he found. Other reporters found the same. He wrote three articles for the Guardian. The then editor Alastair Hetherington, who himself was very pro-Israeli, but not perhaps as much as CP Scott, but certainly in that great Guardian tradition of being very much on the side of Israel and Zionism, didn’t like this, that’s to say the first three articles, but he printed them.

The Fourth Article

This is quite close to my heart because I had similar trouble with this same story thirty years later. This fourth article was about three villages in the West Bank, just north of Jerusalem. One of which you’ll be familiar with, from the Bible Emwas, which in the Bible was called Emmaus. These three villages were obliterated by the Israeli army long after the fighting stopped. The Israeli reason for this was that they felt that the position of these three villages, which was in a position north of and overlooking the main highway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, was militarily suspect. So they kicked the villagers out. They made them march to Ramallah about fifteen miles away, and they razed them. They flattened the three villages. If you go there now, as I’ve gone there, you can still see the ruins under the foliage, but there’s nothing there. These villages ceased to exist. The Guardian refused to accept this article. It was too much for Alastair Hetherington. Michael Adams then took it to The Times. The Times set it in type, as they did in those days, but in the end refused to run it. In the end The Sunday Times ran it.

Likewise, the foreign editor of The Times, who I used to know quite well, a very mild-mannered man, nearing retirement then in 1968, called EC Hodgkin, Teddy Hodgkin, also went to the West Bank and, in his erudite way, he was an expert on the Middle East…he’d covered the original United Nations General Assembly meeting, which partitioned Israel in 1947. Teddy went and wrote an article for The Times, which they published, and which was highly critical of the way Israel was behaving to the refugees in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem. There was uproar. Emanuel Shinwell of the Labour Party, a very famous MP at that time, very well thought of, very highly regarded, but an archetypal vitriolic Zionist, cursed Teddy Hodgkin, this very mild-mannered Englishman, as a vicious antisemite in the Houses of Parliament, a terrible libel of course, which Hodgkin was able to do nothing about.

A little later, The Times decided to publish a supplement, which was organised and paid for by the Arab League. And it did publish four pages within which was an Arab’s explanation of what was happening in the Middle East and in the West Bank of the occupied territories. At that stage, The Times did publish that supplement. It was paid for. They more or less had to. But the editor, William Rees Mogg, father of our famous Jacob, decided at the same time that he should write an apology in the leader columns for this article, dissociating The Times from it in some strange way. He was publishing it, but he didn’t like it, is what he wanted to tell the readers. So it was for The Times, but not of The Times. And he authorised his correspondent then in Jerusalem to write a piece from Israel, which they printed on the front page.

So you can see that even after the Israeli occupation, although there were murmurs and the beginnings of discussion about the condition of the Palestinians on the West Bank, it was a hard job for the journalist.

I want to give you one example of the way the BBC covered the story at the time, because like now, whenever the Palestinian question came up in the late sixties on programmes like The World at One or other current affairs programmes on television, the Israeli point of view prevailed. There was the usual predominance of Israeli spokesmen over Palestinian spokesmen. There was the usual acceptance of the Israeli point of view as being more valid than the Palestinian point of view. There was an imbalance, which I maintain has continued almost ever since, with a gap, which I shall explain. At that time, Christopher Mayhew, a colleague of Michael Adams, a Member of Parliament at that stage, had been in the Foreign Office, he’d quit the Foreign Office over Suez, he wrote to the BBC Secretariat complaining about the imbalance of coverage. This was in 1968. He got this reply from the BBC Head of Secretariat. And I think you should read this very carefully because it’s indicative of the way the BBC still thinks:

Journalists doing an honest job in this country have to take account of the fact that Israeli or Zionist public relations are conducted with a degree of sophistication, which those on the other side have rarely matched. An accurate reflection of publicly expressed attitudes on the issue may well inevitably reveal at times a preponderance of sympathy for the Israeli side.

In other words, said Mayhew and says Tim Llewellyn, the BBC view is that it should not concern itself with striking a balance, but reflect the greater power of the Israeli lobby.

And it’s interesting, thirty years later, I had a very similar conversation, this was in about 2003 or 2004 during the Aqsa Intifada, when things were going very badly and the reporting by the BBC had, once again, deteriorated. I’m going to read what I wrote not long ago about this. I heard a similar view put by a senior BBC news executive with responsibility for Middle East coverage. And I was, like Mayhew before me, complaining about BBC bias and coverage of the second Intifada of 2000 to 2005. I put it to him that if the Palestinian side were not coming up with articulate spokesmen in modern studios in easily accessible locations like West Jerusalem, London, or New York, it was up to producers and reporters to dig them out, find ways of representing Palestinian representatives, commentators on Palestinian views, and put them on the air in the interests of impartiality. The executive’s rejoinder to me was in the same vein as the secretariat had replied to Mayhew, thirty years earlier. He said that if the BBC reporters and producers and editors did that, we would be doing the Palestinians’ job for them.

So, the situation at the end of the 1960s was that the Palestinians were beginning to put themselves on the map. They were doing it in many different ways, but the reporting of their case was still very tricky and still regarded with the greatest suspicion by the organised forces of the British media, the BBC particularly.

Of course, the Palestinians had their own difficulties. First of all, one way they were putting themselves on the map was in creating enormous difficulties in the Middle East itself. There was Black September in Jordan. There was the move to Beirut where they started to cause difficulties for the Lebanese government, after they’d been thrown out of Jordan, bringing their army into Lebanese territory, next door to Israel. And we know what came of that.

So the Palestinian image was being put forward, but sometimes in a negative way. However things did begin to change on other fronts. And I think this is very significant. In the 1970s, a number of different things were happening. The Palestinians were becoming recognised as a people with a cause, and more and more writers were beginning to take up that cause. The mood of the Western world at that stage was, especially among younger people, but among many politicians, somewhat revolutionary. It was the era of Vietnam. Les évenèments on the streets of Paris. There was a movement that said that the Third World, as we called it then, had to be heard. There were injustices that outlasted the end of colonialism. Colonialism was continuing in a new form. The French had only just got out of Algeria, leaving chaos behind them for a while. So there was a different mood abroad.

Secondly, the Palestinians themselves, although their name was in lights for hijacking, for the dreadful occurrences of the murders in Munich in 1972, the attacks across the Israeli border, the Palestinians would be making their case diplomatically. In 1973, the Arab States nominated the PLO and Yasser Arafat as the representative of the Palestinian cause, which was a massive step forward because many of the Arab States were deeply suspicious of Yasser Arafat.

In 1974 in November, Yasser Arafat addressed the United Nations General Assembly. He made his famous ‘gun and the olive branch’ speech, in which he said that if he was accepted diplomatically, if the world looked on the Palestinians with grace and favour, he would reply by being a diplomat himself. And we started to hear the first murmurs of the idea of a two-state solution. Of course, this was rejected by Israel, but the European powers were beginning to listen.

In 1973, Egypt attacked across the Suez Canal, into the occupied Sinai Peninsula and pushed the Israelis back. It looked like a defeat at first. The Israelis came back but the Arabs proved that they were a force to be reckoned with. Later on, in those seventies, there was the Camp David Peace Agreement, when Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt. This was not actually good news for the Palestinians, but it all helped to change the mood.

And the reason I’m talking about this is that during that period, interestingly, the BBC’s attitude — and this was about the time I joined them, as the mood of the politicians began to take into account the Palestinians — towards the reporting began to change.

When I arrived in the Middle East in 1974, I was able to report without fear or favour from the Arab side about what the Israelis were doing. I remember one of the first stories I ever wrote was about how the Israelis had blown up the Syrian town of Kuneitra, on the Golan Heights. The story they were putting out was that Kuneitra had been destroyed by shelling, but it was obvious when we went into there, in spring of 1974, this is after the October War in 1973, that the place had been blown up as the Israelis left, and this proved to be true, and the UN confirmed it. That story was used without fear of favour.

Changing Mood

The mood was changing in the media. The Palestinian case was to be accepted. But at the same time, suspicions of what Israel were doing were growing and the old full-hearted support for Israel was dropping. So you see here, I’m showing parallel lines: as the government shifts, so does the BBC, and so do many of the other elements of the media.

We come to the fact that also at that time, the nature of the press corps in that area was changing. From the seventies onwards, and particularly as the 1980s approached, the newspapers and the BBC started to change their personnel. A whole new generation of younger reporters was beginning to emerge, both in Beirut, where the reporters like myself mixed with the Palestinians, civilian and PLO. We didn’t always get on terribly well with the PLO. They were quite rightly suspicious of anything Western, but we understood what was going on. We heard the Palestinian side of the story, and we were able to write our stories in a much more sensitive way about why the Palestinians were behaving the way they did and why they wanted their rights.

At the same time, in Israel, the newspapers and the BBC were beginning to get worried about the fact that so many of their reporters there were actually Jewish and Zionist, were supportive of Israel, were residents of Israel. And over the years, the foreign media gradually moved in excellent reporters from outside. Sometimes they were Jewish, sometimes they were not, but they were outsiders. They were people coming from Britain, from France, from Scandinavia, from Germany, from the United States, and people who took a different view of Israel, people who had a more objective view of Israel.

This made an enormous change. In the early eighties, people like Ian Black of the Guardian, a superb reporter who speaks Arabic and Hebrew, made a tremendous difference to the way the West Bank and the whole Israel/Palestine issue was being reported. And so we see gradually that under this kind of umbrella of overall British government approval, and of course the same is true with other European governments, to a certain extent, the French particularly, not so much perhaps the Germans, but the reporting became more balanced.

One big event, which is probably largely forgotten now, which helped this process was that the EEC — that’s the European Economic Community, which had nine members, of which the United Kingdom was one — made its famous Venice Declaration in 1980, in which it more or less recognised the Palestine Liberation Organisation, which was a big step at that time. And in a sense, in a sideways way, was critical of the Camp David Agreement, in which Israel had made peace with Egypt, without mentioning really in any significant way, the Palestinians, and left the rest of the Arab world in the lurch, emphasised the fact that the Palestinian question had to be looked at.

And so we have over that period between, I would say, 1974 and the Oslo Agreement, a growing feeling in government circles and in the West in general, less so in the United States, of course, who paid some lip service to this, but the Israeli lobby held on strong there. But certainly, as regards British journalists, the movement was in tandem with government thinking. Even under Mrs. Thatcher, junior ministers, like William Waldegrave and David Mellor, very different people who used to come out to the West Bank — I met them there — were very critical, openly critical of Israel, as indeed was Robin Cook ten years later, under Tony Blair. It would never happen now. But the mood was changing.

At the same time, the Israelis were making fantastic mistakes. Let’s just take a couple of them. People were becoming aware of Israel’s aggression in Lebanon, and the fact that in 1978, Israel had actually occupied the South of Lebanon. People talk as if Israel started to occupy it in 1982, but it didn’t. It started in 1978. That started to arouse problems. Many more press people came out because there was a UN force there, Irish journalists, Norwegian journalists came out. All sorts of people who would not normally have gone to the Middle East were attracted because of the presence of their countries’ soldiers on that tense border between Israel and Lebanon. And not surprisingly, because of the aggressive tactics of the Israelis, these reporters began to find out that the Palestinians and the Lebanese and the South were actually human beings, were oppressed, were having great difficulties under the Israeli thumb, and that the Israelis did not play cricket, to say the least.

So the mood started to shift yet again, but the biggest fundamental mistake the Israelis made was their invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which ended alas in that massacre, which I covered, which I was the first to get the news out about for the BBC, the Sabra-Shatila massacre. The Israelis did not carry out that massacre, but they allowed it to happen. It could not have happened without them. That, on top of a whole summer of Israeli bombing of civilian targets in Lebanon, of the Lebanese and the Palestinians and the ultimate invasion of Beirut itself, the massacre and the long and bloody and tedious withdrawal of Israeli soldiers back down through to the South, which they hung on to for another eighteen years, cast the Israelis in a terribly bad light, and they did not handle it well. They came in for enormous criticism at home as well.

Now I was covering the Middle East at that time. So were my colleagues, many fine reporters like David Hirst at the Guardian, Robert Fisk of The Times… The Washington Post reporters won a Pulitzer Prize for their reporting on Sabra-Shatila. We can see how Israel was really under the media gun. Things weren’t perfect, don’t get me wrong. Israel’s support in America remained strong and it still remained strong, but somewhat subdued, in Britain.

I remember coming back after Sabra-Shatila, and my stories had run without any demur, there was no question. And so it went throughout the 1980s. You start to see the pattern.

What changed though — and there’s a lot more detail to this, which you can ask me about — what really changed I think was in 2000, the mood in the British government changed. Tony Blair was a strong supporter of Israel. Gordon Brown was a strong supporter of Israel. The attacks on the Twin Towers cast a great shadow over the Arab and the Muslim world, for all the wrong reasons, but it did. The Second Intifada, which was a violent Intifada on both sides, was very badly reported. The BBC hedged its bets, it made terrible mistakes in its reporting. The reporting of that Second Intifada, well, I thought was disgraceful and I said so publicly. It was terribly unbalanced. The language used to describe the way Palestinians behaved and the way Israelis behaved was very different.

I’ll just give you one example. Just before the Intifada started, there was an attack on Israeli Palestinians inside Israel itself. In October 2000, Israelis in a mob stabbed two Palestinian Israelis to death south of Tel Aviv. In subsequent violence, thirteen Israeli Palestinians were reported killed. The BBC and ITV reporting was muted. After these attacks, two Israelis held prisoner in a Palestinian police station in Ramallah were killed by a crowd of Palestinians who thought they were undercover agents. Now the language used to describe them was extraordinary. They were ‘killers’. There was ‘rage in their faces’. The descriptions of these acts were much more colourful and vivid than they were about the killers of the Arabs inside Israel. There was a terrible imbalance in the way cause and effect were described. Israelis were always retaliating for Palestinian attacks. And that’s something that still holds true today.

In 2001, the Israelis assassinated a Palestinian leader of the PFLP, firing a rocket through his office window in Ramallah. A month or so later, in a hotel in East Jerusalem, the PFLP assassinated the Israeli tourism minister, shooting him dead inside a hotel inside the West Bank. Now, when that happened, I recall the reporting of the death of the Israeli minister, who was a hardliner, made no mention of the fact that this was an answer to a murder of a Palestinian in the weeks before. And continually we found that there is what I call a spurious imbalance, a spurious equivalence in the way the two sides were reported.

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is described as a war, it takes on warlike terms. One side against the other side, as if there were two equal sides involved in all this.

That’s been the nature of the reporting, I think ever since the beginning of 2000 and the Second Intifada. The Israelis regained their strength, their power over the media. And what we’ve seen in the past few years, unfortunately, with all the protest against this, the board of governors at the BBC reported in favour of these criticisms of the BBC and other broadcast media in 2006. But it did no good. The BBC took absolutely no notice of it. In fact, they got worse, and we see to this day that the reporting is still either missing completely or biased against the Palestinians.

I’ll give you one example. I want to read to you from an interview, and this is typical, which John Humphrys did with a BBC correspondent in Jerusalem after there had been attacks in Jerusalem against settlers and other Israelis. This is how Humphrys began his conversation with this correspondent. Humphrys speaking, ‘yet another attack on Israelis last night, this time an Arab man with a gun and a knife killed a soldier and wounded ten people. Our Middle East correspondent is (I’ll leave his name out to save his face). The number is mounting. Isn’t it? The number is about fifty now, isn’t it?’

Not only does Humphrys’s introduction make it sound as though only Israelis are being attacked. He implies that the fifty who’d been killed since the beginning were all Israelis. The correspondent doesn’t correct him. He says, ‘yes, we think around fifty, over the course of the last month or so, John.’ In fact of the fifty dead, all but eight were Palestinians.

So you see this tremendous imbalance of cause and effect, of who’s doing what to whom, and the lack of explanation why. That same correspondent I heard recently, after more attacks in Jerusalem, was asked why these young Arab men, Palestinian men were carrying out these attacks. He had no answer. He said he didn’t know. That is quite pathetic. Without, in any way, excusing these attacks on Israelis, on settlers, there is an explanation and he could have found it out by ringing up any of a dozen easily accessible Israeli and Palestinian social workers, sociologists, commentators, and experts inside East Jerusalem within a few minutes.

Antisemitism

So there’s a lackadaisical air about the BBC reporting, but it is I think, deliberate, that they would rather not explain things and they would rather avoid the wrath of the Israeli lobby. And then one of the big things that’s made all this worse over the past decade or so is the virulence now with which the friends of Israel and Israel itself are pursuing the idea of antisemitism, so that any criticism of Israel is antisemitic.

This is sticking. This is serious. Nobody at the BBC, no executive, no producer, no editor, no reporter, no one sitting at their desk likes to be called an antisemite, whatever the truth of the accusation. Most of them have no more clue about how to handle this than Jeremy Corbyn and his friends were able to handle the assault on them. This has been a very significant move.

At the same time, our government shows no signs of shifting its view of doing anything about the current threats against the Palestinians, their situation, the threat of annexation, the movement of the American embassy to Jerusalem and so on.

So in that atmosphere, what the BBC does now, I think, is to avoid the issue if it can. The Guardian, it was said, was very glad in 2005, when the Iraq War took place and took the focus away from Palestine and therefore took away a lot of the pressure, which it had been getting for its reporting of the Second Intifada.

I think what we’ve seen in the past few years is the Arab Awakening, the civil war in Syria, the dreadful after-effects of the war in Iraq, and now of course we have domestic issues like Brexit, and then COVID-19, and these have been a great relief for the BBC, a reason to ignore the Palestinian question. I don’t blame the reporters so much in this, as I blame the system. The reporters report in the way they know they will get on the air. That is to say they will report the way I’ve been describing, which is to continue the spurious equivalence, pretending that the talk about one side and the other is a way of getting at the truth.

I’m going to leave it there because I think I spent far too much time on the background, but I think I’ve made the essential point. The BBC especially shifts with the government thinking, and the effectiveness of the friends of Israel and their supporters is crucial in this, and allegations of antisemitism are as crucial as anything.

Media

Well, I think my own feeling is of course online. If you read online websites like Middle East Eye, Electronic Intifada, Middle East Monitor, Mondoweiss, you’ll find fair reporting of not just the situation on the ground in Palestine, but also the background to it and the lobbies and the various pressures, et cetera, et cetera.

As to the mainstream media. I don’t think anybody in Britain is doing a good job with them. And frankly, the Guardian did for many years, the Guardian was at the forefront. Even when the BBC was good, the Guardian was always even more on the ball. And the Guardian remained on the ball in the 2000s, long after the BBC had given up the ghost completely and was reporting it as a kind of table tennis match between Israel and the Palestinians. The only channel I watch now is Al Jazeera. But other people may watch others.

I mention these because I think they’re reliable. I’ve been in journalism now for, I dread to say it, more than sixty years. And I think I know what is authentic and what isn’t. I’ve been following the terrible events in Beirut and Al Jazeera has done a brilliant job. None of these spurious allegations about nuclear missiles are being reported, or taken seriously, as they shouldn’t be, but the reporting on the background is very good.

I think the British government has an influence, not so much directly. I don’t think anybody rings up from Number 10 to some sort of commissar at the BBC or ITV or Sky and tells them the menu for the day. But I think that these broadcasters, especially the BBC, which is very vulnerable, look at what happened in 2005 when they lost the director general and the chairman in one fell swoop over their reporting of Iraq, after their critical reporting of the dodgy dossier. That was another great setback for the BBC. However, to answer the question, I think that the BBC watches the government very closely, but certainly not MI6 or the Foreign Office. The Foreign Office itself has lost a lot of its power, a lot of its weight, unfortunately. And if you go to the Foreign Office for a briefing about Palestine, you probably get a very sympathetic version of the Palestinians and what’s happening. So I would say the answer briefly is that neither of those institutions are really what matter.

This business of the way the Palestinian question has been ignored and is being ignored now is very important. And especially in view of the concentration, quite rightly so, that we’ve had recently on Black Lives Matter and Britain’s past colonial excesses. Now it seems to me that it’s not at all rare on the BBC or on ITV or on Channel Four to see factual and fictional pieces about the horrors of the British experience, the Indian experience of the British Raj, the Amritsar Massacre, the Bengal Famine, the terrible effects of Partition. They’re constantly on our screens, we are very conscious of our dreadful colonial heritage as regards India and Africa.

And now with Black Lives Matter, quite rightly, we’re examining our whole relationship with black British people. The Windrush affair has brought it into the forefront. And all these things are quite valid. The Balfour Project is very aware of this, and that’s why we asked our last speaker, Sarah Helm, to touch on this. Because despite all this soul-searching about the British Empire, the one legacy of the British Empire which still hangs on to the great detriment of the people there and us all, and I reckon eventually to Israel itself, is the Balfour Declaration and its consequences. We made Israel. There’s no question about it. Israel would not have happened without British interference, British takeover of Palestine, the finagling of the Mandate and all the rest of it. And the savage putdown of the Palestinian rebellion in 1936.

Conclusions

Keep complaining at the end of every BBC programme, radio or any other media outlet. Who wrote it? Who produced it? Take the names, write to them directly, write to the complaint system. Follow the rules. They are onerous, and the chances are as ever, and as I found my cost, you’ll get the run-around. Your complaints will be disagreed with rather than fundamentally challenged. And it’s a depressing experience, but it has to be kept up. Because if you don’t challenge, if you don’t keep at it, nothing will ever happen. It’s a depressing prospect, but I’m afraid, that is the way: to keep at the BBC, to keep at your MP. The BBC represents you, not the government, not Israel. The BBC is actually listening to Israel instead of listening to the British people. That’s what you have to remember, and that is outrageous.

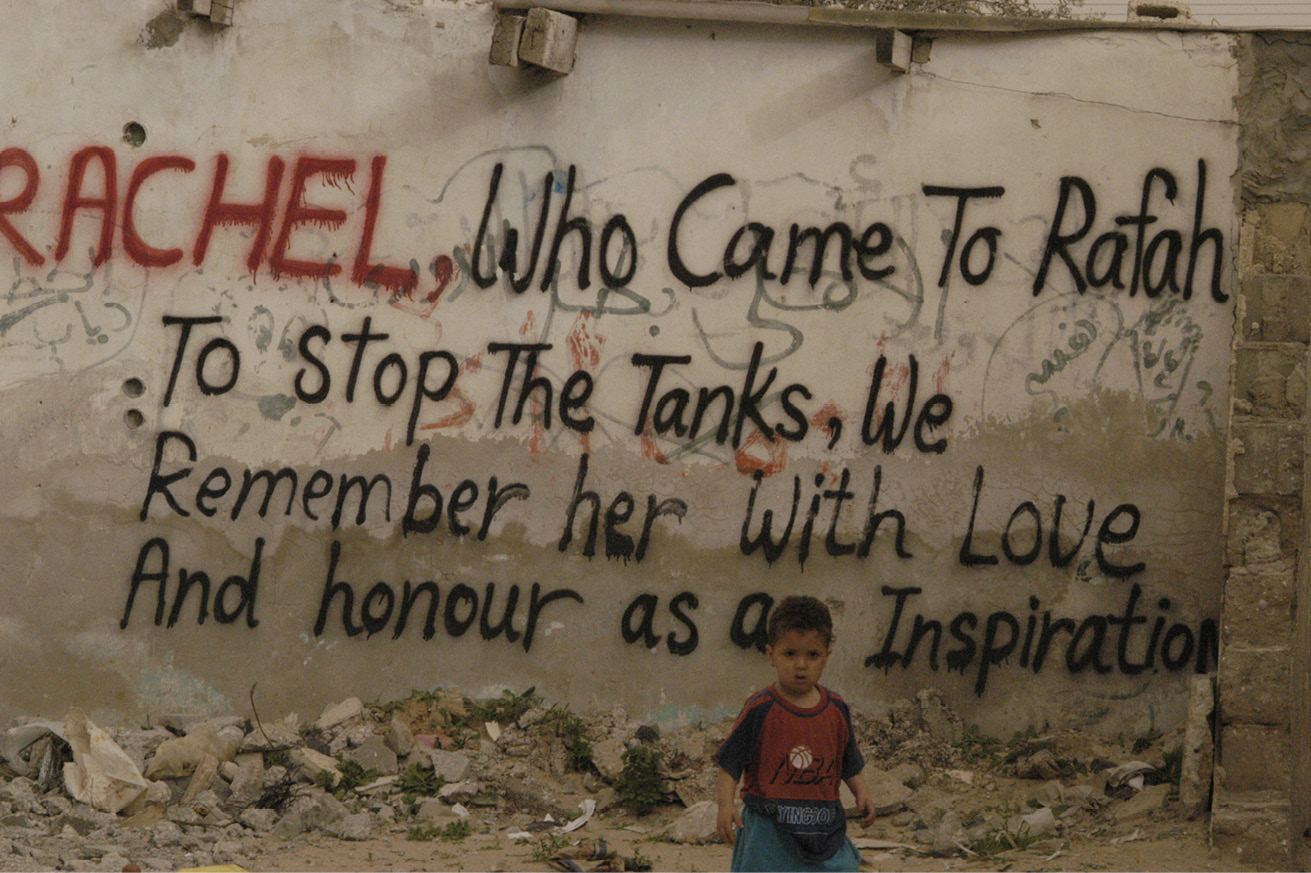

Fig. 18 Tom Hurndall, Memorial to Rachel Corrie at the Rafah border, April 2003. All rights reserved.

1 This is extracted from a talk given online on 13 August 2020, which is available at https://balfourproject.org/tim-on-media/.