16. Palestine is a Four-letter Word: Psychoanalytic Innocence and Its Malcontents1

In Can the Monster Speak? (2021: 96) Paul B. Preciado punctuates his rousing call to psychoanalysts: ‘my mission is the revenge of the psychoanalytic and psychiatric “object” (in equal measure) over the institutional, clinical and micropolitical systems that shore up the violence wreaked by the sexual, gender and racial norms. We urgently need clinical practice to transition. This cannot happen without a revolutionary mutation in psychoanalysis, and a critical challenge of its patriarchal-colonial presuppositions’. Preciado summons us to something very specific. It is not abstract or theoretical. It is material and technical. If psychoanalysis is to transform itself from a disciplinary practice of quiet (and often explicit) violence, we are asked to confront the dynamics and paradigms that objectify rather than liberate.

What follows in this chapter is an account of how contemporary psychoanalysis resists, subverts, and defangs such a possible revolutionary mutation and threats of transformation. But also, more importantly and simultaneously, this chapter highlights the real-time transformation of the field by Palestinian clinicians who wilfully enact and materialise the promise of mutation, and indeed liberation, across Palestine.

To map out the counter-revolutionary forces that attempt to upset the life-affirming mutation happening in Palestine, I will use work that my partner and co-author, Stephen Sheehi and myself outline in our book, Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practicing Resistance in Palestine (Routledge, 2022). Importantly, our work and book utilises a decolonial feminist solidarity-building approach to map out, discuss and platform the work of our Palestinian colleagues, not as they are interpolated by and through settler-colonial logic, nor through what Françoise Vergès (2021) identifies as ‘femoimperialism’ (17) or ‘civilizational feminism’ (4). Rather, we approach Palestinian clinicians through the understanding of them, following Sara Ahmed (2014), as ‘willful subjects’.

Heeding Ahmed (2014: 1–2), we see in Palestine that ‘willfulness is a diagnosis of the failure to comply with those whose authority is given [and]… involves persistence in the face of having been brought down’. It is not coincidental that a decolonial feminist ‘style of politics’ guided our book, especially since decolonial feminist and queer methodologies affirm that cis-heteronormative patriarchal structures, including all forms of capitalism, colonialism, and settler colonialism are the problem. It is not coincidental then that these systems themselves structurally and persistently identify wilfulness as the central problem, a problem of resistance.

Here, I am also heeding what Mamta Banu Dadlani (2020) invites us to do, psychoanalytically, in her own internalisation of Ahmed’s (2019) call to ‘queer’ spaces, theory and action. My approach in this chapter parallels Dadlani’s approach. She reminds us that ‘queer use is a dangerous task, as it involves a lack of reverence for what the colonizer has gifted. By attending to what one is supposed to pass over, creatively engaging with what is left behind, and finding value in what is discarded…one falls out of compliance, and queer use becomes an act of destruction and vandalism of normalized use’ (Dadlani, 2020: 124). In Palestine, we remain invited into this type of world, into a process, mutation and liberation by Palestinian clinicians, comrades and colleagues. These clinicians assert themselves daily as defiant, unassimilable ‘problems’. They are clinicians who ‘fall out of compliance’ because they engage in acts of refusal that alert us to their wilful self-affirmation, individually and communally. In their affirming acts of refusal, both in the street and in the clinical spaces, they ‘speak life’, as Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian says, and they ‘speak Palestine’. In doing so, they insist on the power of liveability.

In psychoanalysis, in a parallel to that which Preciado and Dadlani alert us, wilfulness is largely problematised. Indeed, in psychoanalytic parlance, what Dadlani (2020) especially also dares us to do is attend to the ideological underpinnings of patterns that replicate themselves along always-already fault lines, the violence of which is structured to fall on certain bodies before others. This distribution of violence, vulnerability, and precarity is never coincidental but rather reifies the very structures that created these conditions/possibilities of oppression.

This is how Palestine emerges as a four-letter word in psychoanalysis.

Vignette One: Collapsing Psychoanalytic Space

I presented at the 2017 Society for Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (SPPP) Spring meeting in New York City as a part of a panel that we simply called, ‘Talking About Palestine in Psychoanalysis’. We were happy to see that many Society members also wanted to talk about Palestine in psychoanalysis, with the space quickly becoming standing-room only. Our intention was to use psychoanalytic theory, practice and technique to highlight how the Palestinian narrative had been missing from psychoanalysis — some of us spoke to how that was not coincidental, particularly given the ways in which, historically, settler colonialism operated: the colonised does not have the luxury of a narrative. In fact, the colonised, as Frantz Fanon reminds us, is always presumed guilty. Our panel was one of many that sought to alter the psychoanalytic terrain such that, in this case, the silenced and presumed-guilty Palestinian narrative could find space and so that we, psychoanalysts and psychoanalytic practitioners, could provide witness.

The mere mention of Palestine instigated an ideological psychic break: approximately halfway through our panel, a middle-aged man wearing a white shirt adorned with the Israeli flag made his flagrant entrance into our room. He carried a large paper bag and exuded aggressive energy by locking eyes with me (the only woman, and only Arab, on the panel) and repeatedly flexed his biceps and cracked his knuckles, as if preparing for a fight. The irony was not lost on me that he also appeared to “warrior up” by wrapping his neck with what is traditionally a kuffiyeh (a black and white scarf that has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance). His version of the scarf, however, was adorned with Israeli flags. This man, a fellow SPPP member and psychoanalyst living in New York, blocked the doorway and only entrance to the room for the duration of the panel; he disrupted the panel continually, admonishing the panellists and audience with declarations such as, ‘there is no such thing as Palestinians!’ and ‘Palestine has no place in psychoanalysis!’ Despite several interventions from more senior clinicians, he continued his disruptive behaviour. When people exited at the conclusion of the panel, he forced pamphlets onto them that were entitled, ‘101 Lies that Palestinians Tell’.

The experience was a first for many people in the audience.2 The attempts from senior clinicians were admirable and appreciated given the onslaught, yet largely relied on traditional psychoanalytic theory to offer readings of what may have been happening in the group process. What was largely missing from the interventions, however, was an acknowledgement of what was unfolding in real time, materially, or an analysis regarding the ways in which normative ideology was being actively weaponised. Indeed, hegemonic ideology is most threatened by changes that challenges its primacy. I understood what appeared to be this man’s imperative as not only an attempt to silence dissenting voices, but also, to purposefully deflect and derail a reality-testing exercise that sought to bring Palestine to the forefront against the crushing weight of a dominantly entrenched Zionist ideology.

If we are to call this an enactment, it is one that stems from the fear inherent in a changing of the tides. Indeed, the enactment appeared to be one that exposed a real-time disruption of settler-colonial reality bending (Sheehi and Sheehi, 2022). That is, the mere mention of talking about Palestine was so threatening as to cause a cavalcade of aggression, the primary intention of which was suppressing expression, thought, and witnessing. This act was not arbitrary, nor was it individual or individualised, but rather a logical extension of the violence of the settler-colonial state of Israel, a state that necessitates settler-colonial outposts everywhere — here at a conference — to sustain its myth. Further, in the context of psychoanalysis, it was a vigilante attempt to name what constitutes appropriate or pure psychoanalytic content — a practice that itself is deeply troubling and perpetuated by ideology. So, it comes to be that when we speak of Palestine, the ideological weight of Zionism as its alleged counterpart, as its reaction formation, as the salve perhaps for annihilation anxiety, collapses our ability to remain as much in the material space, as in the symbolic.

The Unspeakable P-word

This vignette, though perhaps more extreme than what typically unfolds on a listserve, might be familiar. Those of us who have long fought in solidarity with the right for Palestinian self-determination against the settler-colonial, Apartheid state now known as Israel have noticed, repeatedly, that something curious, if not entirely ideologically predictable, appears to happen with the mere whisper of Palestine within psychoanalysis. An unspeakable “p” word within a “p” word that transforms the symbolic into the real with one utterance: Palestine. Within our memberships, on our listserves, in our psychoanalytic conferences, the presence of Palestine renders a parallel process, the burden of which appears to be uncontainable; the affective response of which appears to be anxiety-ridden; the experiential space of which appears to be perpetually conflict-inducing. The curiousness comes because the word “Palestine” appears to hold a unique power within psychoanalysis. The taboo word swiftly conjures the most unbending ideological splits despite contemporary psychoanalysis’ emphasis and insistence on fluidity in theory, technique and practice, and despite its growing willingness to address issues of class, race, gender and ableism.

As a psychoanalytic clinician, scholar and activist, I believe psychoanalysis has a critical role in speaking to and about injustices, liberation struggles, and the unconscious processes that may work to replicate systems of oppression. Of course, I am not the first to note this. From Freud to Fenichel, Fromm to Fanon, and more contemporarily, clinician-activists,3 especially those from and in the Global South, and especially Palestinians, have urged clinicians to interrogate and centre the decided link between psychoanalysis and our sociopolitical world. Moreover, they have called on us as a field to embody the ethics of clinical work, to veer away from disavowing our responsibility in unpacking the distressing and demoralising material stemming from the systemic inequities beyond our clinics.

In the case of Palestine, however, we have seen that time and again, these ethical calls often turn to ether and are subject to a particular type of weaponised ‘psychoanalytic rigor’ such that, in Fanonian terms, one witnesses the materialisation of a ‘racial distribution of guilt’. In Psychoanalysis Under Occupation (Sheehi and Sheehi, 2022: 61), we expand on this tendency and locate it within a phenomenon we term, psychoanalytic innocence. Ideology is intrinsic to the viability of psychoanalytic innocence and ideological misattunement (Sheehi and Crane, 2020) is a central, mechanical tenet of psychoanalytic innocence which allows for displacement and banishment of material reality and social conditions from the therapeutic space. Stephen Portuges (2009: 70) warns us about this misuse of psychoanalysis’ hallmark principle, neutrality, which ‘has turned out to be a technical intervention that obfuscates the recognition and elucidation of the role of ideologically constructed factors in the psychoanalytic theory of treatment that contribute to patients’ psychological difficulties’. He reminds us that this ideological manoeuvre displaces the embodiment of social conditions and material realities within historically marginalised patients.

Like neutrality, in making Palestine a four-letter word, psychoanalytic theory and practice, through psychoanalytic innocence, works in service of settler-colonial violence. For example, psychoanalysis’ insistence on dialogue, reason, and working through, even with the mention of Palestine, without a sustained analysis of the material conditions of dispossession inflicted on Palestinians acts under the pretence not only of neutrality and objectivity, but also universalism, empathy as an endpoint of process, and the myth of safety. In this way, psychoanalytic innocence works in concert with the logic of settler colonialism and occupation, denying the everyday violence enacted on Palestinians and conveniently forgetting how this is also structured by the unconscious. Indeed, psychoanalytic innocence relies on the hegemony of what Lynne Layton (2006) has termed ‘normative unconscious processes’. Deployed in this way, it is particularly insidious because it simultaneously forfeits psychoanalysis’ supposition of unconscious process and structure, while also ignoring material reality.

I would also like to draw our attention to how liberal and humanistic psychoanalysis maintains this naturalisation, remaining complicit through forms of oppression by seeking to graph a universalised ‘healthy’ adaptability onto colonial and racialised subjects whose humanity and psychic interiority are negated. In a liberalised version of psychoanalytic theory, these colonial subjects, especially Palestinians, are only able to access ‘empathy’ from psychoanalysis when they occupy the position of ‘victim’, and surrender their rights to experience political and material realities in full alignment with their experience and social context — a psychological process that involves succumbing to ‘colonial introjects’, as I have noted elsewhere (Sheehi/Masri, 2009), or to what David Eng (2016) calls ‘colonial object relations’. This does not happen intrapsychically, but rather, structurally and systemically, one part of which is when Palestine is treated as a four-letter word.

Treating Palestine as a four-letter word demands an unspoken, yet affectively felt, prerequisite for Palestinian and pan-Arab subjectivity: you must simultaneously open yourself to predominantly anti-Palestinian spaces, but do so without claim to historical, and political specificity, and, also commit to a fundamentally self-effacing dialogue while being aggressed upon. This dialogue is expected to happen without noting the visceral truth (what Fanon might say is felt on a cellular level) of how this feels and what it means materially, i.e., the reality of what Dorothy E. Holmes (2006) might call ‘wrecking effects’. More specifically, we are not to speak of how this depoliticised dialogue about Palestine, whether in the clinic or professionally, replicates a particular social order that demands one’s non-affect while itself being mobilised through affect — demanding to be felt but remain unseen, unacknowledged, and unpacked.

The discussion of Palestine is indeed circumscribed by entrenched ideological formations, particularly Zionism, that saturate, even unconsciously, our theory and practice as a psychoanalytic collective. While many in the field have long sounded the alarm of PEPness (Progressive Except Palestine) as one such hegemonic ideological formation alongside cisheteronormativity, patriarchy, etc. that enframe our field, practice and theory, the utterance of Palestine continues to cause a particular type of collapse of psychoanalytic process, technique and practice. In other words, the mention of Palestine appears to shut down psychoanalytic thinking and trigger an urgent fleeing into psychoanalytic innocence. My observation, then, is that the utterance of Palestine provokes a resistance against what otherwise might be spoken about and/or experienced as a natural reflex to psychoanalytic thinking. If we view this as ideological, it is also decidedly not coincidental. In keeping with psychoanalytic innocence, the utterance itself — Palestine — is seen as the aggressor.

The way I have witnessed this process to unfold — or perhaps better, collapse — is through a primarily unconscious internalisation of an ideological formation, which is itself supported by material, social, cultural, and historical conditions (i.e., the conditions that perpetuate the social relations in which we are reared and come to find identifications) (Layton, 2006; Portuges, 2009).

Fanon (1952, 1963) himself was aware of the potential for this doubled-edged sword of psychoanalysis. Armed with its tools and promises, he also alerts us to the dangers of dominant ideological formations within psychoanalysis itself and how they work to reconstitute themselves in the same breath they are being torn down. If Fanon is speaking of the power and force of racism and colonialism, I am speaking of Zionism as a settler-colonial ideological formation, a set of logics — psychic, political, economic and social, based on the negation of the Palestinian people.

The presence of this internalised dominant ideological formation in our psychoanalytic collective precipitates a splitting off of conflicting identifications in order to retain and maintain its structural coherence. This is the foundation from which normative unconscious processes (Layton, 2006) emerge. That is, the unbending identification instigates an expression of normative unconscious processes that necessitate the disavowal of other potential self-states, or identifications, that may contradict or threaten the integrity of the ideological formation. The anxiety of deviation, therefore, is so pronounced, though perhaps not conscious, that all attempts to hold true to the position are made. Due to its unconscious ‘common sense’ (Hollander, 2009) quality, this ideological formation is at once all-encompassing and can go on unchallenged if not acknowledged and unpacked by our community as a whole.

The countless examples of this collapse is an indictment of how psychoanalytic scholars and clinicians (even activists), are complicit in perpetuating ways of thinking and actions, professionally and clinically, that deny the humanity of the Palestinian people. It is also an indictment of how the mere mention of Palestine collapses analysable spaces in service of a dominant ideological position of innocence in which psychoanalysis finds itself secure and privileged.

Disavowing Israeli Apartheid

Many readers will be familiar with the details of how the International Association of Relational Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy (IARPP) made the unconscionable decision to hold its 2019 conference in what is now known as Tel Aviv, Israel, as well as the years of ‘negotiations’ in the aftermath of this decision. This particular event was the lynchpin in solidifying my thinking about how entrenched psychoanalysis’ ideological misattunement is, and what later cohered around the concept of psychoanalytic innocence (Sheehi and Sheehi, 2022).

Indeed, this example highlights how Palestine, after decades, continues to consistently emerge as a four-letter word not just within the clinic, nor on the individual level through the analytic dyad, but rather structurally and systemically. This debacle is also meant to urgently highlight how Psychoanalysis, through its insistence on apolitical, universal humanism causes undue harm and violence to Palestine and Palestinians on a global scale. I am hopeful that this will alert us to our field’s responsibility in the suffering of others, as Layton (2019) reminds us.

I will primarily focus on how psychoanalytic innocence operates rather than deflect from the affective charge by exclusivising or essentialising this to IARPP as an institution. Indeed, IARPP’s bad faith decision is helpful only inasmuch as it provides us with a very visible and archetypal example of how ‘liberal’ modalities of psychoanalytic practice betray what Avgi Saketopoulou (2020) also aptly refers to as ‘whiteness closing ranks’ within psychoanalysis, here when the issue of Palestine is raised.

Psychoanalytic innocence emerges as a powerful lens to read why the IARPP deliberately crossed an international picket line called for by more than 20,000 Palestinian social workers and psychologists (https://bdsmovement.net/news/palestinian-union-social-workers-and-psychologists-urges-colleagues-not-participate). This analytic is especially important if we are to move away from sanctimonious ad hominem attacks. The IARPP affair demonstrates psychoanalytic innocence, bringing into focus the mechanisms by which psychoanalytic associations and, indeed, practitioners, especially from the global North, not only disavow the comprehensive violence of settler-colonial systems, but also actively perpetuate and participate in this violence, by pathologising, in this instance, resistance to Israeli apartheid and by diminishing the value of Palestinian life and well-being.

Indeed, psychoanalytic innocence helps us account for the glaring contradictions in IARPP’s positions, seemingly indecipherable to IARPP leadership. For example, without invoking psychoanalytic innocence, how else do we account for locating the conference in Tel Aviv with the theme ‘Imagining with Eyes Wide Open: Relational Journeys’? This decision betrays the unconscious marking (Razack and Fellows, 1998) immediately naming whose relational journey is worth imagining. As I have noted elsewhere (2019), how does an organisation imagine a conference in the settler-colonial state of Israel without implicitly, if not explicitly, dis-imagining Palestinians? Or at least, a particular type of Palestinian? This was further highlighted in an absurd pre-conference roundtable discussion that aimed to speak about ‘the absence of Palestinians to look at the obstacles to an Israeli Palestinian encounter’ — even here blatantly disavowing the countless Israeli-Palestinian encounters that happen under a brutal occupation. This same roundtable asked the seemingly innocent questions: ‘can we create a dialogue about the absence of dialogue? Can we give presence in the absence of presence? Is the absence a powerful protest or a refusal to see another?’

We are able to see clearly through this example how the power of psychoanalytic innocence relies heavily on the ability to weaponise and abuse theory to gaslight those who engage in the politics of refusal, whether that be a patient, a supervisee, a student, an analysand, or in this case Palestinians and those who believe in their right to self-determination. The IARPP replicated the same strategies of innocence within psychoanalysis, with the organisation and its leadership appealing to abstract notions of “reason”, “civility”, and, of course, “dialogue” — all the while disavowing how these terms and notions are decidedly not neutral and, in fact, rely on racialised, classed and gendered codes to gain traction.

Psychoanalytic innocence here resembles Margarita Palacios and Stephen Sheehi’s (2020: 295) exposé of white innocence, namely that, ‘within its habitus of universal humanity, permits us also to consider how the flesh itself that is constituent of the “we” is not ideologically and socially same throughout this heterogeneity of the third-person collective’. In this way, IARPP provided the ideological valiance of “impartiality” and “openness” as the operative structural process of collusion with racism and settler colonialism.

What is especially important when considering psychoanalytic innocence are the ways in which the field brazenly deploys tropes of “dialogue” and “neutrality” to censure, while simultaneously deflecting from how these very concepts are also mechanisms for collusion, control and dominance. This perhaps was evident in IARPPs co-presidential statement:

We will be extending invitations to Palestinian colleagues, and we will work to enable their presence with us. Rather than foreclosing those issues and silencing conversation, we aim to create within our relational psychoanalytic conference an open and safe space in which attendees across the political spectrum can engage and exchange views. We believe that dialogue, more than ever, is needed across divides.

While on the surface this might strike some as “reasonable”, if we operationalise psychoanalytic innocence, and the way Gloria Wekker (2016) highlights how Edward Said’s (1993) ‘cultural archive’ manoeuvres unconsciously. Most importantly, it is not reasonable if we attend to a sustained material analysis, at which point the statement emerges as an archetypal hybrid of liberal bad faith, combining the “white innocence” of the United States with the disavowal and nomenclature of soft Zionism. Even if Palestinian and non-Palestinian Arab clinicians had been willing to betray the Palestinian call for boycott, most were not able to travel to Israel, legally, as they would have faced criminal proceedings in their home countries. Finally, we know that even if they were able to receive “visas”, the process is intended to be psychologically humiliating and subjecting Palestinians to such processes just to be present would be an unconscionable violation.

The weaponisation of language contrived to shut down, not create, space and legitimised explicitly non-Palestinian voices as the arbiters and protectors of Palestinian freedom of speech. Samah Jabr, a Palestinian psychiatrist and chair of the Mental Health Unit at the Palestinian Ministry of Health and her co-author Elizabeth Berger, hone in on such language, saying, ‘leadership took ownership of the virtuous language of “dialogue”, the “third”, and “empathy” while asserting that Palestinians who decline their kind invitation might be indulging in the reprehensible language of “splitting”, “non-inclusiveness”, or “acting out” ’ (Berger and Jabr, 2020). In this particular example, the statement acts as testimony to the predetermined parameters of conversation or “dialogue”, one that communicates little interest in material reality. In this way, psychoanalysts, and psychoanalytic organisations, quickly come to embody what Fanon warned were the ways in which clinicians act as agents of the State.

Further, IARPP not only egregiously attempted to derail an independent event called ‘Voices of Palestine’ held simultaneously to their NYC 2018 conference, but also, in what we already know is a surveillance state, hotel security was alerted of potential ‘danger’ posed by supporters of the event. Indeed, New York Police Department (NYPD) and Homeland Security were present in full and visible force during the Voices event, a presence that was deemed ‘coincidental’, despite proof from hotel staff stating otherwise. Here innocence is marked since, surely one could anticipate that a call to NYPD about ‘concerns’ regarding any activity in support of Palestine would be heard and read against anti-Arab and Islamophobic tropes that readily saturate the collective unconscious.

If we are not using psychoanalytic innocence as a framework analytic, we might be tempted, indeed seduced, into reading IARPP’s response to the dissent of its members as a psychological ‘enactment’ of the irreparable violence between Zionists and Palestinians. What this reading misses, however, are the ways in which this response demonstrates a clear example of how psychoanalytic innocence ensures that psychoanalysis, as a field, ideologically and politically colludes with power — not as a byproduct or symptom, but as constitutive of its practice and theory. This is because collusion and complicity operate within a shared structural, systemic, and political tradition of whiteness that emerges out of coloniality and settler colonialism. What the traditional psychoanalytic reading also displaces is how calls for ‘dialogue’ and neutrality — mainstays of our practice — are weaponised, here insinuating that there might even be a ‘safe-space’ where dialogue can exist. In fact, this example demonstrates how dialogue itself can be a structural tool to disempower.

Again, perhaps if we were not attentive to the mechanics of psychoanalytic innocence, we would get mired in theories of displaced fear or misdirected hate, identification with the aggressor, etc. — all important theoretical readings, but readings that nonetheless do not account for material reality, let alone offer a sustained analysis of struggle in the context of settler colonialism or why Palestine consistently emerges as a four-letter word.

IARPP enacts and performs a betrayal of what, structurally, we as a psychoanalytic field have always relied on: the fantasy that we can exist outside of the material reality of power. Here, psychoanalytic power is literal in terms of credibility as bestowed by the psychoanalytic establishment, and the power we have to name another’s process; it is also innocent, as an organisation like IARPP is given space to exist both as a perpetrator of political and social violence and still be received as non-threatening, afforded plausible deniability through the wilful unlinking of whiteness (and its violence) and coloniality from their organisational actions (even pleading with us to remember ‘the good people’ within its ranks — of course they exist, even if they become magically undone of their power to represent structures).

When it comes to Palestine — and by extension, perhaps all other ‘unseeable’, unanalysable spaces and issues (classism, sexism, transphobia, xenophobia), we first must acknowledge and examine our own collective complicity and investment in sustaining the structures through and by which oppression can continue to happen.

Oppression works best when the oppressed, here the Palestinian, becomes responsible for all suffering — theirs and that of their oppressor, while the oppressor, through collective complicity and hegemonic power is consistently exonerated and provided the magnanimity of innocence. The success of a dominant ideological formation, as distinguished from other types of ideologies, is predicated on the normalisation of its presence, the literal ‘taking in whole’, such that it is undetectable and results in a ‘common sense’ acceptance. Within our ranks, our own continued unwillingness to include the Palestinian narrative within our oeuvre as well as the foreclosed analytic spaces such as those described above normalise and, indeed, prioritize Zionism, while in the same breath demanding ‘dialogue’ (Sheehi, 2018) from those who express dissent.

Insisting on Presence

The act of refusal is a wilful act, a positive act, and a productive act — an act that, according to Glen Coulthard in Red Skin, White Masks, can also be encouraged and read as a ‘disciplined maintenance of resentment’ (2014: 108). We should not read this as a deflection from the depth work of psychoanalysis, but rather, as a contingency for vibrant liveability in the face of oppressive structures. Palestinian refusal, especially on the part of our Palestinian clinician colleagues, is an affirmative wilful disobedience and is a retooling not only of psychoanalytic theory and practice but also the ethics of care. To bring us back to Preciado (2021: 94), their ‘position is one of epistemological insubordination’.

Our Palestinian colleagues and comrades are ‘willfully disobedient’, as Sara Ahmed (2014: 149) would say, the disobedience of an oppressed people to become an ‘agent of [their] own harm’. Whether in the clinic, in supervision, or in the street, Palestinian clinicians validate Palestinian selfhood and Palestinian subjectivity in the face of brutal occupation. Their ‘willful disobedience’, especially in positions in which they are constitutively disenfranchised, radiantly expresses wilfulness as an act of affirming relationality, as a wilful act of affirming and standing with their patients, each other, their families and their community.

These positions by Palestinians are decolonial and feminist positions, ones that reclaim feminism, in Vergès’ (2021: 17) words, and realise in their powerful simplicity, ‘the way in which the complex of racism, sexism and ethnocentrism pervades all relations of domination’. While we are busy metamorphosing the mere whisper of Palestine into a four-letter word, our Palestinian colleagues are refusing, in the most beautiful Fanonian sense, to become agents of the state and to engage in carceral discipline of themselves or their patients. Rather, they are mutating psychoanalytic practice into a radical, decolonial feminist practice that operates on a revolutionary potential of attuned care.

In this way, Palestinian insistence on presence, even as psychoanalysis actively attempts its negation, embodies Preciado’s call to us: ‘drag the analysts’ couches into the streets and collectivize speech, politicize bodies, debinarize gender and sexuality and decolonize the unconscious’ (95).

Our Palestinian colleagues engage daily with revolutionary acts of refusal, which also embody autonomy — an autonomy that is social and communal rather than focused solely on the individual or limited to the clinical dyad. It is an autonomy that insists on indigenous presence in defiance of settler regimes, carceral logics and, most importantly to our field, their psychoanalytic proxies.

Our Palestinian clinician comrades resist becoming a four-letter word and, instead, highlight for us how their clinical work comes to be both a space for resistance for their patients and also an extension of their own resistance against settler-colonial hegemony; a collective practice, unified precisely through its engagement with creating and maintaining life and life-worlds, as well as political and historical realities, for Palestinians, by Palestinians.

Bibliography

Ahmed, S., Willful Subjects (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822376101.

Berger, E., and Jabr, S., ‘Silencing Palestine: Limitations on free speech within mental health organizations’, International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 17(2) (2020), 193–207, https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.1630.

Coulthard, G. S., Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001.

Dadlani, M. B., ‘Queer use of psychoanalytic theory as a path to decolonization: A narrative analysis of Kleinian object relations’, Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 21(2) (2020), 119–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2020.1760027.

Eng, D. L., ‘Colonial object relations’, Social Text, 34(1) (2016), 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3427105.

Fellows, M. L., and Razack, S., ‘The race to innocence: Confronting hierarchical relations among women’, Journal of Gender Race & Justice, 1 (1998), 335.

Fanon, F., Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 1952).

Layton, L., ‘Attacks on linking: the unconscious pull to dissociate individuals from their social context’, in L. Layton, N.C. Hollander, S. Gutwill (eds), Psychoanalysis, Class and Politics: Encounters in the Clinical Setting (London: Routledge, 2006), pp. 107–17, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203965139.

Palacios, M., and Sheehi, S., ‘Vaporizing white innocence: confronting the affective-aesthetic matrix of desiring witnessing’, Subjectivity, 13(4) (2020), 281–97, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-020-00106-9.

Preciado, P. B., Can the Monster Speak?: Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts, vol. 32 (Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2021).

Portuges, S., ‘The politics of psychoanalytic neutrality’, International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 6(1) (2009), 61–73, https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.188.

Said, E., Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 1993).

Sakatopoulou, A., ‘Whitness Closing Ranks’, 2020, https://wp.nyu.edu/artsampscience-nyu_pd_blog/2020/06/30/whiteness-closing-ranks-avgi-saketopoulou/.

Sheehi, L., and Crane, L. S., ‘Toward a liberatory practice: Shifting the ideological premise of trauma work with immigrants’, in P. Tummala-Narra (ed.), Trauma and Racial Minority Immigrants: Turmoil, Uncertainty, and Resistance (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2021), pp. 285–303, https://doi.org/10.1037/0000214-016.

Sheehi, L. and Sheehi. S., Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practicing Resistance in Palestine (New York: Routledge, 2022), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429487880.

Sheehi, L., ‘Disavowing Israeli Apartheid’, Middle East Report Online (MERO), 2019, https://merip.org/2019/06/disavowing-israeli-apartheid/.

Sheehi, L. (n.e Masri), ‘Introjects in the Therapeutic Dyad: Towards Decolonization’, Major Area Paper in the Completion of the Doctorate of Psychology’, George Washington University, 2009. Unpublished.

Sheehi, S., ‘Psychoanalysis under occupation: Nonviolence and dialogue initiatives as a psychic extension of the closure system’, Psychoanalysis and History, 20(3) (2018), 353–69, https://doi.org/10.3366/pah.2018.0273.

Vergès, F., A Decolonial Feminism, trans. A. J. Bohrer (London: Pluto Press, 2021), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1k531j6.

Wekker, G., White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822374565.

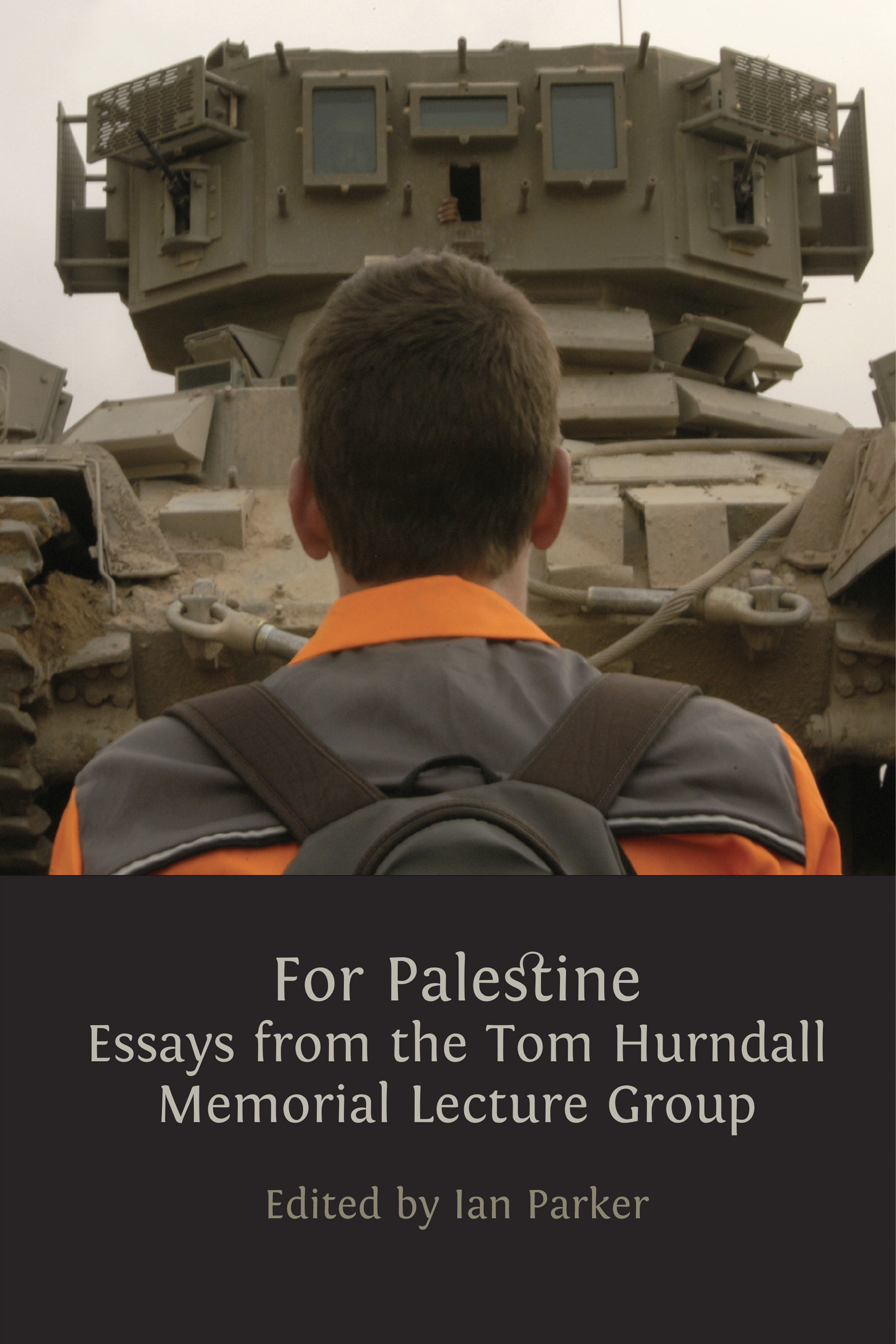

Fig. 19 Anonymous, Tom Hurndall playing football in the Al Ruweishid Refugee Camp at the Jordan/Iraq border, photo taken on his Nikon camera, March 2003.

1 My immense gratitude to Ian Parker without whom this piece would not have come into existence and whose fierce solidarity is moving, even across the distance. Thank you, also, to Manchester Metropolitan University for holding the Hurndall Memorial Lecture at which I was generously invited to speak. Most movingly, I want to thank and extend my deepest love and solidarity to and with the Hurndall family — it is a moving honour for me to carry Tom’s legacy in print — a responsibility I take seriously and with the militancy that does his life justice. My own commitment to revolutionary love is daily stoked by my partner and co-author, Stephen Sheehi — thank you for lending your heart, comradeship and brilliance to this piece and to our book. A brief portion of the vignette on ‘collapsing psychoanalytic space’ appeared in Sheehi, L. (2018). ‘Palestine is a Four-Letter Word’, DIVISION/Review, 18, pp. 28–31.

2 A video I took of the disruption is deeply troubling — a room full of clinicians, many of whom are “frozen”, heads hanging, unsure of how to intervene. Many confided in me following the panel that they had been concerned the man was carrying a weapon; many women further commented to me about their sense of danger and feelings of being intimidated as well as their concern about confronting an aggressive, hypermasculinist male in a closed space with no escape.

3 See for example, work by Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Rana Nashashibi, Fathy Flefel, Samah Jabr, Lama Khouri, Shahnaaz Suffla, Mohamed Seedat, Kopano Ratele, Guilaine Kinouani, Foluke Taylor, Robert Downes, Ian Parker, Erica Burman, Martin Kemp, Chanda Griffin, Leilani Slavo Crane, Annie Lee Jones, Kirkland Vaughans, Carter J. Carter, Nancy Hollander Lynne Layton Stephen Portuges and countless others.