2. Human Rights in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

© 2023 Richard Kuper, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345.03

The events in Gaza and on the West Bank, appalling as they are, are not the only, or even the most terrible, infringement of human rights to be found on the planet. One only has to think of the genocide in Darfur, or the torture camp at Guantanamo. Why does the fate of the Palestinian people, and peace in the Israel-Palestinian conflict, matter so profoundly?

Singling out Israel

Individuals will have personal reasons for singling out any cause they choose to support. You might identify with those who are suffering or see their oppressors as like ‘us’, or feel responsible historically in some way for that particular cause, and wish to make amends. And while we might hope that all oppressions would be universally condemned on the simple grounds that people shouldn’t treat others the way they do, we know this doesn’t cut much ice in the real world. There are too many valid causes and we inevitably select from these, hoping perhaps that success in one will have a knock-on effect. But shouldn’t we be consistent? Isn’t Israel singled out above all possible justification? Doesn’t this encourage antisemitism? Isn’t Israel demonised? The answer is, sometimes, yes. Solidarity movements generally tend to exaggerate the purity of their own side and the sheer bloody nastiness of the oppressors.

Sometimes this exaggeration does overstep all reasonable, and sometimes indeed acceptable, boundaries. In the case of Israel, it is especially important to get the criticism right. Not just because those striving for justice in the region are up against powerful geo-political interests that give Israel a great deal of support; but, because of Israel’s particular history, getting it wrong can and is used to mobilise sympathy and support in favour of ‘plucky little Israel’, ‘outpost of Western values’, and this despite action after action that, in the case of some other state, would call down universal condemnation. We need to remember that the immediate circumstances giving rise to the establishment of Israel is a history of European antisemitism culminating in a genocide in which a full third of Jews worldwide were exterminated. It was a genocide in which, it must be said, the world basically stood by. This has to be taken on board if we want to understand the extraordinary depths of emotion that surround so many discussions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

I would go further and say that we need to understand the fear of antisemitism among Jewish communities in the world today, nor must we downplay its existence. The fact that cries of antisemitism are sometimes used to silence critics of Israeli policies should not lead us to dismiss all cries of antisemitism as phoney. They are not. Antisemitism, like all other forms of racism, is a plague in Western societies and a plague on civilised values. But I am not concerned here with a strategy for opposing racism in general, or antisemitism in particular. I merely want to alert you to the need to be alert in solidarity work for those things which undermine the struggle morally, and allow debate to be diverted from the realities of the situation on the ground into emotive highways and byways. There is no need to exaggerate, no need to demonise, no need to make false comparison; and we simply need to think carefully about the language of struggle that we deploy. So I want to reflect on this ‘singling out Israel’ issue.

Double Standards

My own reasons for concern are perhaps worth recording. I grew up in apartheid South Africa in the 1950s and Zionism promised an alternative life for young and idealistic Jews like myself who found apartheid anywhere between uncomfortable and unbearable, and who saw little possibility of doing anything meaningful about it. A disproportionate number of Jews, to their credit, were deeply involved in the anti-apartheid struggle; but others organised an alternative social world around the goal of making ‘aliyah’ (lit: rising up) to Israel and found warmth and comfort in the egalitarian ideals of the kibbutz or in the challenge of building a new society from the ground up, of ‘making the desert bloom’. Of course, we ‘knew’ there were some Arabs in Israel; we also knew that many had left, egged on, we believed, by vindictive Arab leaders who promised that they would return triumphant to their lands once the Jews had been thrown into the sea. Unwittingly, we cast Arabs into the same mould as the apartheid regime we abhorred cast the blacks; as alien, foreign, other, an existential threat. It didn’t strike us as odd in the slightest that a people who had had nothing to do with the Holocaust in Europe should somehow be expected to pay the price they had been forced to pay.

I came to England and became a committed socialist. But it nonetheless took me a long time to recognise the double standards I was operating in my personal life with regard to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; and my commitment today to the Palestinian cause has no doubt elements of atonement within it. I most certainly single out Israel, in part at least because I turned a blind eye to aspects of it when I should have known better, and because I expected more of it. My personal trajectory may not be intrinsically interesting. But what is interesting is that so many people converge on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a focus of their attention and commitment.

Indeed, Norman Geras, writing on 13 January 2006 in his blog, makes this a reason for inherent suspicion:

It doesn’t just happen that a whole lot of individuals converge on one cause. There have to be reasons. The movement today to institute boycotts of one kind and another against Israel, but not against other states whose human rights records are worse, and often vastly worse than Israel’s — I just name Sudan here to get this point comprehensively settled — didn’t come about simply through a lot of different individuals homing in, for a multitude of personal reasons, on the justified grievances of the Palestinians. Either there are good reasons […] [o]r there are not such good reasons — and then there is at least a prima facie case for thinking some prejudice against the country or its people may be at work.

Now I happen to think there are good reasons (even if they’re not good enough for Norman Geras, whose comments postdate an earlier attempt of mine to look at the issue of ‘Singling out Israel’!).

The points I had previously made, and which Geras found inadequate, were the following:

First, Israel singles itself out and presents itself as special. It sees itself as a state based, as its Declaration of Independence declares, ‘on the precepts of liberty, justice and peace taught by the Hebrew Prophets’. In the words of Isaiah, ‘We are a light unto the nations’. Israel is constantly lauded as the only ‘democratic country in the Middle East’ with the ‘most moral army in the world’. It invites evaluation in terms of its own founding principles and it constantly reaffirms its commitment to these values. It claims to be defending Western values and presents itself as an outpost of these principles. What better criteria to judge it by?

Second, Israel is special, in that it controls a number of religious sites that are of especial significance to three world religions. They have been contested over the generations and the millennia. In recognition of this reality, UN Resolution 181 of 1947, on which Israel’s legitimacy is based, called for the creation of a special international zone, encompassing the Jerusalem metropolitan area. Since then, religious concerns and motivations have deepened, and there are literally hundreds of millions of Christians and Muslims, in particular, who have grave concerns about their holy places. You don’t need to be religious yourself to appreciate the profound part that religious sentiment has played historically, and indeed increasingly continues to play, in today’s world. All of this sits uneasily with Israel’s 1980 ‘annexation’ of East Jerusalem and declaration that ‘a united Jerusalem’ is ‘the eternal capital of the Jewish state’, an annexation that the UN Security Council Resolution 478 of 1980 unanimously rejected as a violation of international law.

Third, the United States clearly finds Israel special, in that it has been far-and-away the largest single recipient of US foreign aid since the 1960s. From 1949 to 1996, the total of US foreign aid to all of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean combined was $62.5 billion, almost exactly the same amount given to Israel alone in this period! Total aid to Israel was approximately one third of the US foreign-aid budget until the Iraq invasion, and still remains at a very high level. The extent to which the US has singled out Israel as its most loyal ally in the region is indeed extraordinary. Insofar as one believes that the US plays a dominant role in the international system, its choice of which countries to support is of legitimate concern. When the US, often standing alone, vetoes resolution after resolution concerning Israel in the UN Security Council, on the issue of Gaza on 13 July 2006 and again on 11 November 2006, Israel is singled out. Israel is singled out, too, by the US as being the only country allowed to possess nuclear weapons with no demands being made for their control.

Fourth, Israel singles itself out in a different way with regard to the Jews of the world. It presents itself as their real home, as opposed to the multiplicity of countries in which Jews have settled and integrated. Integration can never be permanently successful, antisemitism is ever-present and persecution is always just around the corner. In that sense, there is always an implicit accusation of disloyalty made against Jews who do not give Israel their whole-hearted support. And Jews who speak out against the actions of the Israeli government as ‘Not in Our Name’ are often accused from within the Jewish community of ‘self-hatred’ or worse.

To these four points I would now like to add two more.

Fifth: Israel presents itself as a bastion of ‘Western values’ in general terms as already mentioned, but, since 11 September 2001, also in the ‘war against terror’, a battle that Israel claims to have been fighting for decades. Days after 9/11 Sharon called Arafat ‘our Bin Laden’, despite Arafat’s opposition to Bin Laden’s opportunistic adoption of the Palestinian cause. And indeed, Israel is treated differently in many ways, as though it were the frontline in some division of the world between the West and ‘the Other’, Europeans and Muslims or whatever terms some supposedly fundamental divide the future clash of civilisations is cast in.

The sixth point is the occupation. What other country has been in occupation of another people’s land for such a long period, in defiance of international law; what country has refused to define its borders and accept, or indeed even acknowledge, the green line and print it on its maps, as the Israeli government has failed to do over past decades? Perhaps China’s domination of Tibet has some parallels, though the PRC bases its claims to Tibet on the theory that Tibet became an integral part of China 700 years ago. It is a disputed history perhaps, but very different from the Israel-Palestine situation.

It is my contention that each of these points, taken alone, gives a valid reason for ‘singling out’ Israel. Taken together, I believe the case is overwhelming. Double standards do indeed predominate in any discussion of Israel, but rarely in the way its supporters claim. Throughout much of Europe and much of the Muslim world, it looks as though Israel is indeed singled out for favour, for support, for exemption when others are condemned. It is time to stop singling Israel out in this way, and to hold it accountable to the same values and criteria it claims to be embodying: values that are liberal, democratic, non-discriminatory and just.

Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law

So, having identified what I believe to be ample grounds for this focus on Israel, I now want to single out Israel in a very precise sense, contrasting its high-flown rhetoric and its actual practice in respect of human rights, particularly in regard to war. Let me say at the outset that I am not a lawyer. But I can also say that these issues are too important to be left solely in the hands of lawyers. What I say will be informed by my reading of legal texts and issues, and I believe it will stand up to scrutiny at the legal level. I know it will stand up to scrutiny at the human and moral level, at the level of ordinary everyday understanding. And should it be found wanting on some nice legal point here or there, I hope it is the law which will change over time, not our reactions to what appear to me self-evident violations of human rights. I therefore make no claims to originality in what I am going to say. Rather, the reverse. I hope I can document everything by references to documents and interpretations which command general agreement. I am indebted in particular to the International Humanitarian Law Research Initiative, based at the Harvard School of Public Health, to B’Tselem, the Israeli information centre for human rights in the occupied territories, to ACRI, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel and to Human Rights Watch. (Perhaps I should add in thanks to the dozens of other organisations that also contribute to monitoring human rights in Israel-Palestine: the Palestine Centre for Human Rights, Physicians for Human Rights, Rabbis for Human Rights, MachsomWatch, the Israeli Campaign Against House Demolitions, Yesh Din, and the rest.)

I believe that the various charges add up to a simple one―that the Israeli army, far from acting as ‘the most moral army in the world’, as it claims to be, acts with impunity in the occupied territories, where violence on a daily scale, including torture and illegal killings, goes not only unpunished but generally unremarked upon. The Law of Occupation, according to the International Humanitarian Law Research Initiative, is one of the oldest and most developed branches of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Among other things, it regulates the relationship between the Occupying Power and the population of the occupied territory (including refugees and stateless people), providing protection to the latter against potential abuse by the former. The definition of occupation is very practical: does the foreign military force exercise actual control over a territory? There is no need for a declaration of intent by the occupying forces, nor are their motives for occupation relevant.

Occupation does not and cannot confer sovereignty over any of the occupied territory to the Occupying Power. This can come about only by a freely entered-upon agreement between equal partners. On the contrary, the Occupying Power has duties: it is responsible for ensuring public order and safety in the occupied territories, and should not interfere with the social and political fabric of society unless absolutely prevented from doing so.

The law of occupation is codified largely in the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, specifically designed to protect civilians in times of war. It focuses on the treatment of civilians at the hands of the adversary, whether in occupied territories or in internment. Adopted on 12 August 1949, it entered into force on 21 October 1950; and Israel ratified it with effect from 6 July 1951.

The Convention prohibits, among other things, violence to life and person, torture, taking of hostages, humiliating and degrading treatment, sentencing and execution without due legal process, and collective punishments of any kind, with respect to all ‘protected persons’. It calls for them to be humanely treated at all times, with no physical or moral coercion, intimidation or deportation. Article 147 specifies ‘grave breaches’ of the Convention as including wilful killing; torture or inhuman treatment; wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health; unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a protected person; wilfully depriving a protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial; taking of hostages and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly. Israel, I believe, is in daily breach of its obligations under international law. Putting it into cautious legal language, some of these breaches probably amount to war crimes.

a) Let us start with the simple issue of humane treatment (all Articles referred to below are Articles of the Fourth Geneva Convention, available at https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gciv-1949). Article 27 states: ‘Protected persons are entitled, in all circumstances, to respect for their persons, their honour, their family rights, their religious convictions and practices, and their manners and customs. They shall at all times be humanely treated, and shall be protected especially against all acts of violence or threats thereof and against insults and public curiosity.’

In reality, almost everything that follows here has a bearing on this general rubric of ‘humane treatment’. Let me introduce it here with a few instances of violations:

- Every day tens of thousands of Palestinians are subjected to a checkpoint system involving body searches, humiliation and inconvenience. These checkpoints are routinely justified as part of Israel’s necessary security system, to prevent terrorists infiltrating into Israel. What is not generally known is that of the more than 600 barriers, road blocks and physical checkpoints in existence on the West Bank at more or less any point in time, no more than twenty-six are between Israel and the occupied territories; the rest are all internal.

- In report after report, Machsom [Checkpoint] Watch and B’Tselem chronicle incidents of violence, at times gross violence, against Palestinians that are unnecessary and without justification. Claims of police or army brutality generally remain uninvestigated and have become the norm. This is made abundantly clear, too, in the testimony of former soldiers now in the organisation Breaking the Silence.

- From September 2000 to September 2006, sixty-eight pregnant Palestinian women gave birth at Israeli checkpoints, leading to thirty-four miscarriages and the deaths of four women, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry’s September report.

- The Family Unification Law forbids Israelis married to, or who will marry in the future, residents of the Occupied Territories from living in Israel with their spouses. This law does not apply to spouses who are not residents of the Occupied Territories and is inherently racist in its formulation.

b) More specifically, on the issue of torture or brutality, Article 31 states: ‘No physical or moral coercion shall be exercised against protected persons, in particular to obtain information from them or from third parties.’ Article 32 prohibits the use of ‘any measure of such a character as to cause the physical suffering or extermination of protected persons’, a prohibition that applies not just to murder, torture, etc., ‘but also to any other measures of brutality whether applied by civilian or military agents’.

Violations:

- According to a 2003 report by the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel and other human rights organisations [Back to a Routine of Torture: Torture and Ill treatment of Palestinian Detainees during Arrest, Detention and Interrogation September 2001–April 2003], there is evidence of systematic and routine torture of Palestinian prisoners causing ‘severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental’. Violence, painful tying, humiliations and many other forms of ill treatment, including detention under inhuman conditions, are a matter of course. The report claims that the activities of Shin Bet or General Security Services (GSS) are rubber stamped by the bodies which are supposed to keep the GSS under scrutiny:

- The High Court of Justice had not accepted a single one of the 124 petitions submitted by the Public Committee Against Torture against prohibiting detainees under interrogation from meeting their attorneys during times of Intifada.

- The State Prosecutor’s Office transfers the investigation of complaints to (you’ve guessed it!) a GSS agent to follow up.

- The Attorney General grants wholesale, and with no exception, the ‘necessity defense’ approval for every single case of torture.

The result is a total, hermetic, impenetrable and unconditional protection that envelops the GSS system of torture, and enables it to continue undisturbed, with no supervision of scrutiny to speak of. The achievements of the HCJ [Israeli High Court of Justice] ruling of 1999, which was to put an end to large-scale torture and ill treatment, limiting it to lone cases of ‘ticking bombs’, have worn thin… (2003 report by the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel and other human rights organisations)

Ha’aretz reported on 8 November 2006 that:

In the past year alone, about 40 allegations of serious torture of Palestinians have been submitted to Attorney General Menachem Mazuz. […] [He] has not deemed any of the complaints as warranting a criminal investigation against the interrogators.

c) With regard to collective punishment Article 33 states: ‘No protected person may be punished for an offence he or she has not personally committed. Collective penalties and likewise all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited.’

Violations:

- The Family Unification Law (see above), is a form of collective punishment.

- The sweeping nature of restriction of movement in the form of closure, siege and curfew constitutes a form of collective punishment. After the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, Israel imposed a total closure on the occupied territories and has prohibited Palestinian movement between the occupied territories and Israel and between the West Bank and Gaza, unless they have a special permit. Since 2000 Israel has issued no new entry permits. Israel also imposes internal closures on specific towns and villages. Since October 2000, most Palestinian communities in the West Bank have been closed off by staffed checkpoints, concrete blocks, dirt piles or deep trenches. During curfews, residents are completely prohibited from leaving their homes. As B’Tselem has put it:

The sweeping nature of the restrictions imposed by Israel, the specific timing that it employs when deciding to ease or intensify them, and the destructive human consequences turn its policy into a clear form of collective punishment. Such punishment is absolutely prohibited by the Fourth Geneva Convention.

- House demolitions are carried out under the emergency regulations (DER 119) of the British mandate which provide for an authority to demolish a house as a response against persons suspected of taking part in or directly supporting criminal or guerilla activities. Recently, application of DER 119 has become limited to instances in which an attack was launched from a specific house or cases in which an ‘inhabitant’ of the house was suspected of involvement in an offense. The term ‘inhabitant’, however, has been broadly defined to include persons who do not necessarily reside in said house regularly, and often is applied to family homes in which a suspected offender previously resided. The regular occupants’ knowledge of the offense has been deemed irrelevant by the Israeli authorities. This is clearly a form of collective punishment. Had I more time I would deal with issues like imprisonment without due process as well as deportations and destruction of personal property, all covered by relevant clauses of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Instead, let me move rapidly to one of the central questions of the occupation: — that of the colonies or, as the more anodyne English word has it, ‘settlements’.

d) Settlements: Article 49, para 6 states:

The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.’ And the Hague Regulations prohibit the occupying power to undertake permanent changes in the occupied area, unless these are due to military needs in the narrow sense of the term, or unless they are undertaken for the benefit of the local population.

Settlement activities were relatively slow to begin after the occupation, and there were only thirty settlements by 1977. But six years later, after Ariel Sharon became first Minister of Agriculture, then Minister of Defence, in the Likud government of Menachem Begin, the number soared to over a hundred. Similarly, the number of settlers, small to begin with and only topping fifty thousand in 1982, had doubled a decade later. Then, between 1993 and 2000, the number of settlers on the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem) increased by almost 100 percent. (These were of course the Oslo years, with the biggest single increase during 2000 at the height of the peace negotiations.) There are, as of 2006, close to four hundred and fifty thousand in all, including substantial settlements in East Jerusalem, numbering at least one hundred and eighty thousand.

The establishment of the settlements leads to the violation of the rights of the Palestinians as enshrined in international human rights law. Among other violations, the settlements infringe the right to self-determination, equality, property, an adequate standard of living, and freedom of movement. […]

Despite the diverse methods used to take control of land, all the parties involved — the Israeli government, the settlers and the Palestinians — have always perceived these methods as part of a mechanism intended to serve a single purpose: the establishment of civilian settlements in the territories.

B’Tselem’s conclusions, again in its own words, are as follows:

Israel has created in the Occupied Territories a regime of separation based on discrimination, applying two separate systems of law in the same area and basing the rights of individuals on their nationality. This regime is the only one of its kind in the world, and is reminiscent of distasteful regimes from the past, such as the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Peace Now Settlement Watch has published ‘Breaking the Law in the West Bank — The Private Land Report — Nov. 2006’, the summary of which begins:

This report by the Peace Now Settlement Watch Team is a harsh indictment against the whole settlements enterprise and the role all Israeli governments played in it. The report shows that Israel has effectively stolen privately-owned Palestinian lands for the purpose of constructing settlements and in violation of Israel’s own laws regarding activities in the West Bank. Nearly 40 percent of the total land area on which the settlements sit is, according to official data of the Israeli Civil Administration (the government agency in charge of the settlements), privately owned by Palestinians. The settlement enterprise has undermined not only the collective property rights of the Palestinians as a people, but also the private property rights of individual Palestinian landowners.

Summary: Grave Breaches of the Convention

Article 147 specifies ‘grave breaches’ of the Convention as including wilful killing; torture or inhuman treatment; wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health; unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a protected person; wilfully depriving a protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial; taking of hostages and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.

I have given a mere hint of the evidence for the prima facie breach of Article 147. Comprehensive records of all of these acts have been documented by reliable Israeli human rights organisations (as well, of course, by many reliable Palestinian organisations) and can be easily found on the internet.

What Does Israel Say about This?

Israel, after all, is not some two-bit banana republic, but fiercely proud of its allegiance to democracy and the rule of law.

Israel’s official position is that the Fourth Geneva Convention is not applicable. That claim is based on an extremely narrow interpretation of Article 2 of the Convention, claiming that the Convention only applies where a legitimate sovereign is evicted from the territory in question. According to this argument, since neither Egypt nor Jordan were recognised as legitimate sovereigns of the Gaza Strip and West Bank respectively prior to 1967, the Convention is not applicable.

This argument has however been rejected by the entire international community, including the United States (and by many Israelis), since Article 2 explicitly sets out the conditions of application and is clearly intended to apply when an occupation begins during an armed conflict between two or more High Contracting parties. It makes no distinction regarding the status of the territory in question.

Irrespective of the nature of the war in 1967, Israeli conquest of the Occupied Territories was the direct result of just such an ‘armed conflict’ between High Contracting Parties to the Convention.

Israel has also argued that it has voluntarily applied the ‘humanitarian’ provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention. This is disingenuous as the document is in its entirety a ‘humanitarian’ document and, as a signatory, Israel is bound by the entire document, not just the parts it chooses to apply. Furthermore, the Israeli Supreme Court recognises the situation as one of ‘belligerent occupation’ and has recently applied the Convention on the basis that ‘the parties agree that the humanitarian rules of the Fourth Geneva Convention apply to the issue.’

Israeli governments have sometimes claimed that the settlements are the result of the initiatives of private citizens, not state policy. This is a transparent lie, since government after government has implemented a consistent and systematic policy intended to encourage Jewish citizens to migrate to the West Bank. Tools used to this end are the granting of financial benefits and incentives to citizens, raises in the standard of living of these citizens and encouragement of migration to the West Bank. Indeed most of the settlements in the West Bank are defined as national priority areas. In 2000, for instance, the average per capita grant in the Jewish local and regional councils in the West Bank was approximately sixty-five percent higher than the average per capita grant inside Israel.

Israel argues it has valid claims to title in the occupied territories based on ‘its historic and religious connection to the land’, ‘its recognised security needs’, and the fact that it came under Israeli control ‘in a war of self-defense, imposed upon Israel’. Nothing in the Convention leads credence to any of these arguments which are irrelevant in terms of international law.

However, in June 2000, the Israeli government well and truly demonstrated the cynicism of its claim, in which it had persisted since occupying the territories in 1967, that the territories are ‘disputed’. In their last-ditch legal attempt to prevent the government from removing them, the Gaza settlers took their case to the Israeli Supreme Court. The government asserted that it was, indeed, in belligerent occupation of the territories, and had always been so. Therefore Israeli settlements in them could only ever have been temporary and could be removed by the government. The Supreme Court decided in favour of the government by a 10:1 majority. It said that its decision applied to the West Bank as well as Gaza.

The Concept of ‘Military Necessity’

Israel often uses the concept of ‘Military Necessity’ to justify its actions: Article 27 of the Fourth Geneva Convention allows the Parties to the conflict to ‘take such measures of control and security in regard to protected persons as may be necessary as a result of the war.’

But, military necessity is not what any occupying army says it is. Military necessity is, strictly, a legal concept rather than a military one, an exception to the applicability of International Humanitarian Law only as and when it is so stated in the law. So, for instance, military necessity can never justify actions that are prohibited in absolute terms under the law, e.g., acts of torture or other inhumane treatments.

A decision on the legality of the actions and policies of the occupying power must be made considering all information reasonably available, and after ascertaining that there is no feasible alternative, military necessity incorporates clear conditions: the occupying power must be facing an actual state of necessity; there must be an immediate and concrete threat; and the measures adopted must be proportionate.

The Wall

The hollowness of the Israeli justification was made very clear when the legal situation with regard to the Wall/barrier/security fence was clarified by the International Court of Justice in an advisory opinion issued on 9 July 2004. No overview of human rights in the territories would be complete without a look at the Wall which provides the starkest image possible of the realities of the occupation. A complex structure, part twenty-five-foot-high wall, part ditch and barbed wire, part an intrusion-detecting fence, part path/road and smoothed strip of sand to detect footprints, the barrier, when completed, will be over twice as long as the green line it is supposed to protect.

Only about one fifth of the route follows the Green Line itself; in some areas it will run far inside the West Bank in order to capture key Israeli settlements such as Ariel (twenty-two kilometres inside the West Bank), the Gush Etzion bloc (with fifty thousand settlers) near Bethlehem and the Maaleh Adumim settlement east of Jerusalem. ‘Despite Israel’s contention that the wall is a “temporary” security measure’, comments Human Rights Watch, it captures settlements that Israel has vowed to hold onto permanently; for example, when PM Sharon said that the Ariel bloc of settlements ‘will be part of the State of Israel forever’.

According to realistic estimates, the barriers will result in the isolation of tens of thousands of Palestinians from the rest of the West Bank and from each other. Strictly speaking, I could have used aspects of the Wall story to illustrate any and all of the breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention alluded to above, but there has actually been, in July 2004, a legal ruling by the International Court of Justice (available online at https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/131). This is the highest instance of international law, so it is worth looking at in its own right.

The ICJ ruling settled definitively many issues that Israel had long disputed:

- It emphasised that East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza are occupied territories.

- It ruled that both the Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention were applicable to the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT).

- It ruled that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the main foundation of international human rights law as opposed to international humanitarian law, are all applicable within the OPT; and that the construction of the barrier violated various provisions of each of these conventions.

- It ruled the construction of the barrier to be in violation of international law. The ICJ called upon Israel to immediately cease construction and dismantle the barrier, as well as to make restitution or pay compensation to those injured by the barrier.

- The ICJ noted the possibility that Israel would use the barrier as a means to incorporate the settlements which ‘would be tantamount to annexation’ and thus infringe the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination. It ruled that the barrier violated various provisions of international humanitarian law, especially relating to the destruction and seizure of property in occupied territories.

- It ruled: ‘The wall, along the route chosen, and its associate regime gravely infringe a number of rights of Palestinians residing in the territory occupied by Israel, and the infringements resulting from that route cannot be justified by military exigencies or by the requirements of national security or public order.’

- It ruled that Israel’s construction of the barrier was not justified either by the right to self-defence enshrined in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter or by a state of necessity.

It Is Time to Draw This to a Conclusion

It is my belief that it is necessary and desirable to ‘single out Israel’, but in doing so, I have chosen to focus on universalist human rights themes. We can, and must, debate the origins of these human rights violations: the extent to which they are simply the kind of thing that happens in all prolonged occupations, the extent to which they arise from Israel’s demographic obsession with having a Jewish state and the racist fear this generates about Palestinian population growth as a ‘ticking bomb’; the old Zionist dream of a greater Israel, wanting Judea and Samaria but not wanting the Palestinians, and so on. But in this talk I have merely wanted to focus on what Israel is currently doing and, by implication, the need to mobilise opposition to it.

I’d like to conclude by returning to the situation in Gaza: According to B’Tselem: ‘On October 30 [2006], Israel’s Prime Minister Ehud Olmert reportedly told the Knesset Security and Foreign Affairs Committee that in the past three months, the Israeli military has killed 300 “terrorists” in the Gaza Strip in its war against terror groups’.

B’Tselem points out that this includes 155 people, including 61 children, who did not even take part in any fighting and ‘sends a dangerous message to soldiers and officers, according to which unarmed Palestinian civilians are a legitimate target. The statement contains within it a twisted logic whereby the fact that someone was killed by the military proves that he or she is a terrorist.’ Since the commencement of Israel’s Occupation Forces operation in Beit Hanoun on 1 November 2006, the number of additional dead has reached 77.

Uri Avnery, asking if the Beit Hanoun massacre was done on purpose or by accident, says this:

The ammunition used by the gunners against Beit-Hanoun — the very same 155mm ammunition that was used in Kana — is known for its inaccuracy. Several factors can cause the shells to stray from their course by hundreds of meters. He who decided to use this ammunition against a target right next to civilians knowingly exposed them to mortal danger. Therefore, there is no essential difference between the two versions.

The truth is that the Israeli army and its soldiers on the ground are acting with impunity. There may be rules of engagement, there may be high moral standards, but in practice they are all too often ignored and no sanctions are applied to those ignoring them.

And Tom Hurndall’s murder showed all too well how the system works…

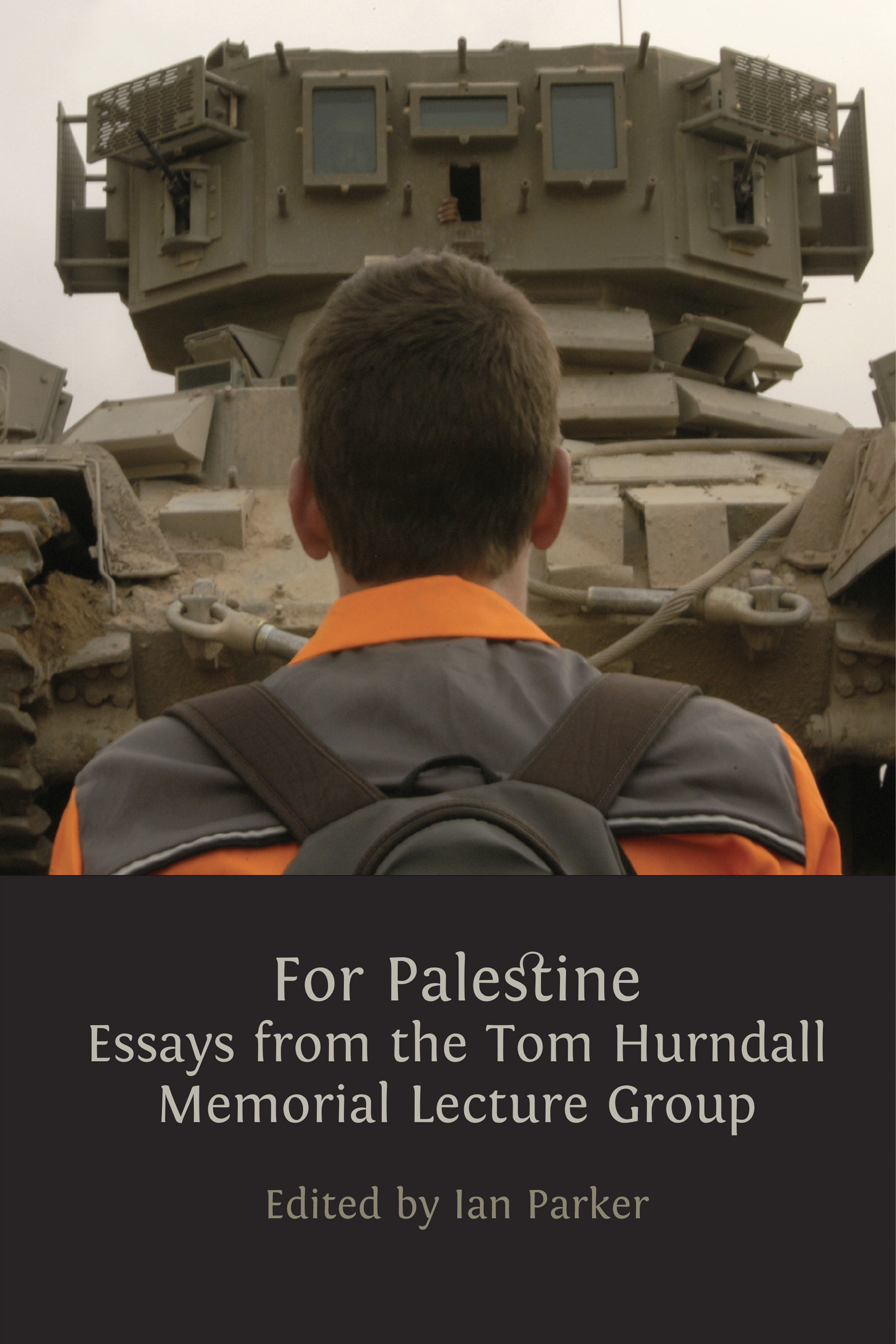

Fig. 5 Tom Hurndall, Israeli soldier communicating with ISM volunteers on the Rafah border, April 2003. All rights reserved.