3. New-Old Thinking on Palestine

There is a famous Jewish maxim that people tend to look for a lost key where there is light and not where they lost the key. There is a sense that the diplomatic efforts to end the Israel/Palestine conflict were a search for the key where there was light, but not where it was lost. In this chapter, I will attempt to explain why this was a shot in the dark and why it is still going on, despite its obvious failure. In the second part I will suggest a better location for the lost key and a different pathway towards a solution.

Oslo Accords

The efforts of the Oslo peace accords, which has now been dead for many years, began in the immediate aftermath of the 1967 June War. It was an accord directed from Washington and highly influenced by both mainstream scholarly ideas of ‘conflict management’ and Israel’s major concerns. From the very start, the Palestinians were ignored as significant contributors to the peace agreements. These efforts were based on a certain perception of the origins of the Israel/Palestine conflict and the reasons for its continuation. This perception re-graded the 1967 June War as the starting point for the conflict and hence framed the conflict as a dispute over the future of the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Such a perception reduces Palestine geographically to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (22% of historical Palestine) and the Palestinians to the people living in those two areas. More profoundly, this approach is based on the assumption that the conflict in Israel/Palestine is between two national movements with equal right to the place that need external help to find a compromise.

This paradigm of parity stems from the academic background of many of the Americans involved in the peace process. According to this view, an outside mediator should have adopted a business-like approach to the conflict over Palestine (in its reduced geographical and demographic definition). This paradigm is based on two principles. The first is that everything visible is divisible or, put differently, partition is the best solution for conflicts such as the one raging between Israel and Palestinians. The second principle is that partition should reflect the balance of power and would, most importantly, be accepted by the stronger party of the divide. This meant not only that Israel since 1967 in all the peace plans was offered more and the Palestinians less; the proposition was also accompanied by a certain didactical logic: if the weaker party declines the offers of partition, then a lesser deal will be offered to it. Hence the Palestinians were offered half of Palestine in 1947, around twenty percent after 1967 and subsequently just over ten percent of their homeland.

Since 2007, this approach has been abandoned, at least temporarily, by the main outfit that is supposed to carry it on: the ‘Quartet’ (made up of the EU, UN, US and Russia). Before 2007, however, it dominated the peace efforts from the days of the shuttle diplomacy in the 1970s (when the then American Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, was moving between Amman and Jerusalem trying to find a formula which would divide the West Bank and the Gaza Strip between Israel and Jordan), through the Autonomy talks following the Israeli-Egyptian peace agreement, up to the Madrid conference of 1991 that introduced the Palestinians as partners for the partition of the occupied 1967 territories. In 1993, this approach was the basis for the Oslo Accords, an agreement that has disastrously deteriorated the quality of life of the occupied people of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. However, the principle of partition and the didactic approach were less manifest in the Declaration of Principles signed on the White House lawn on 13 September 1993.

In an article in Ha’aretz on 4 September 2018, Amira Hass explained in detail how Oslo was the fruit of Israel’s cunning scheme to perpetuate the occupation rather than to end it. Hass claimed that the ‘Bantustans’, the fragmented West Bank and the Gaza Strip, are the result of ingenious Israeli planning that was carried out by deceiving the world and creating a situation that absolved Israel of any legal and economic obligations to these enclaves. Hass pointed to another fact that indicates that the Oslo process enacted a further partition and fragmentation of Palestine. The negotiations with the Palestinians were entrusted to the Civil Administration. This body had managed the occupation since 1981 and was bound to continue the occupation by all means possible. One of their practices, typical to any colonial regime, was ‘divide and rule’. Therefore, while the Oslo Accords promised to protect the integrity of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as one unit, the Civil Administration did all it could to keep them apart, in the name of the accord.

The accord left the decision about the status of the Palestinians in the occupied territories in the hands of this Civil Administration. This power of registration allowed Israel to treat the Gaza Strip as a different administrative unit after 1993. On top of this, Israel made it almost impossible for people to move between the two enclaves. The accord does not mention the word ‘occupation’, Hass commented, nor the right of the Palestinians for self-determination; while the Palestinians, and probably most of the international representatives involved in the accord, assumed that Palestinian self-determination and the end of the occupation was the main goal of the Oslo Accords.

The separation is accompanied by a particularly cruel water policy. The separation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank included a partition of the water resources, which allocated to the people in Gaza a very limited aquifer that soon dried out and led to the salination of the soil. Further proof of Israel’s real intentions behind Oslo is the increased policy of house demolition pursued since the accords. This, again, formed part of the systematic destruction of the infrastructure that rendered the prospect of an independent state de facto impossible.

The separation of the West Bank into Areas A, B and C enabled Israel, through the definition of Area C as one under exclusive Israeli military control, to annex informally 60 percent of the West Bank. The rest were bisected by apartheid roads open only to settlers and new settlements, all part of a plan that accompanied the 1993 alleged Israeli commitment to reconcile with the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

So, one important reason for the failure of this approach was that there was never a genuine wish by Israel to accept a ‘two states’ solution based on the Palestinian right of self-determination and independence. However, even if there was some ambivalence displayed by Israel (due to a struggle between a kind of peace camp that wanted to move towards a two-states solution and a right-wing coalition vehemently opposed to the idea), it seems that in the beginning of this century such an ambiguity faded away and the Israeli political system shifted to the right with a clear anti-two states agenda.

More importantly, there emerged a new political consensus that since the peace process is dead, what is needed is a unilateral Israeli policy of annexation, fragmentation, ethnic cleansing and strangulation. The purpose of these unilateral actions is to ensure Israel’s supremacy in historical Palestine and beyond. This approach is different from the one adopted by the governments which ruled Israel in the first thirty years of occupation. While all Israeli governments since 1967 could not envisage an Israel without the West Bank (and some without the Gaza Strip as well), they disagreed on how best to ensure this geographical achievement that had been won in the June War of 1967. Until the turn of this century, the governments of Israel were obsessed with the demographic question; hence the principal methodology for keeping the West Bank as part of Israel included territorial compromises and active ethnic cleansing in areas such as the Greater Jerusalem region, in order to have the land without the people.

Israeli political leaders are not deterred by the demographic reality in twenty-first-century Israel and Palestine. The vision of a Jewish state in which most of the Palestinians do not have equal rights is a reality into which many of the Israeli Jews were born and which they accept as morally valid and politically feasible (and this was finally institutionalised through the Nationality Law passed at the end of 2018). Any Palestinian resistance is framed today in Israel as terrorism, and any criticism from the outside is branded as antisemitism.

This approach and policy dimmed the dividing line between Israel and the occupied territories. Although there are still differences in the judicial status of Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line, these seem to disappear quickly. The facts on the ground, i.e., an ongoing Jewish colonisation of the West Bank, which includes not just small settlements, but proper urban sprawl, render any idea of a sovereign independent Palestinian state impossible. As mentioned before, ‘Dawlat Filastin’, the State of Palestine, which is how the Palestinian authority refers to Area A in the West Bank, is merely eleven percent of the West Bank (which is less than three percent of historical Palestine), and is under total Israeli control.

Thus, in 2019, we were faced with an international community that still sponsors the two-state solution, a fragmented Palestinian leadership losing its legitimacy by the day that also adheres to this solution, and diminishing Israeli support for this kind of solution. The real peace effort has been dead for all intents and purposes for a long time. We waited, without holding our breath, for Donald Trump’s ‘Deal of the Century’ that was supposed to reignite the process. We now have quite a clear idea of what that would have entailed: in essence, an American blessing of Israeli unilateralism. The plan was very clearly stated by major figures in the government that ruled Israel in 2018, and which was always likely to have a similar composition after the April 2019 elections. It included an Israeli annexation of Area C (as noted, 60 percent of the West Bank) as a major step to be followed by enhanced autonomy in Areas A and B for the Palestinian Authority. The next step is to try to depose Hamas and install the PA instead, either by force or thorough political agreements.

Trump was not going to offer anything that the American administrations have not offered before. He was in any case more honest about America’s role in the Israel/Palestine question. The previous administrations pretended to be honest brokers in the conflict, but in essence unconditionally adopted the Israeli point of view and disregarded the Palestinian one. In the past, the official position of the State Department was that the Israeli annexations of Jerusalem and the Jewish colonies in the West Bank were illegal, but in practice nothing was done to stop them from expanding. Trump seemed to be more candid when he admitted openly that the US is not an honest broker and that his first priority is to give carte blanche to the Israelis to do what they deem right in the Palestine question. Trump’s policy would have been the same as previous ones, but without the charade.

In fact, we knew that it was more likely that Trump would desert any meaningful effort to intervene in the Israel/Palestine question. It also seemed very unlikely that another international actor, be it the EU or China, would take America’s place. The result is stagnation in the peace process and the continuation of Israeli unilateral policies aiming at solidifying Israeli control all over historical Palestine. The imbalance of power is such that currently one can see no internal or external actors who can change this course of action or improve this dismal reality.

An Alternative Way Forward

This is a good time for reflection on an alternative way forward in the long run, without forgetting for a moment to deal with the catastrophic situation on the ground. The situation on the ground worsens precisely because the old plan is not working and there is no alternative to replace it. The number of political prisoners in the West Bank has increased, as has the killing and the demolishing of homes and villages such as Han al-Ahmar. The Judaisation is expanding, the brutal settlers’ harassment reaching new heights of intimidation and violence. The situation in the Gaza Strip is even worse. The UN predicted that in 2020 the Strip would be unsustainable, and therefore, we have to be conscious of the need for short-term action and long-term thinking. In many ways, the BDS (the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement represents the need to engage urgently with that reality, while strategising for the future. The movement was founded around 2005 in response to a call from the Palestinian civil society to the international community to take a more vigorous position towards the Israeli policy in Palestine. It identified three basic rights which Israel violates with regard to the Palestinians: the right of the Palestinian refugees to return; the right of the Palestinians who live in the occupied West Bank and the besieged Gaza Strip to be freed from military rule; and the right of the Palestinian minority of Israel to equal citizenship in the state. One can only hope that this strategy, which has so far been effective, will eventually stop at least some of the atrocities on the ground.

Meanwhile, we should make up for the wasted half-century, in which everyone was looking for the key to where the light is and not where we lost it. For that to happen, we have to recognise the need to revisit the history of the Zionist project in Palestine and adopt a new dictionary that would fit the realities on the ground and the chances for reconciliation in the future.

The new approach is based on a historical analysis that goes back to the early days of Zionism (whereas the dominant view in the West depicts 1967 as the departure point of the conflict). The new approach also frames the conflict as one between a settler-colonial movement, Zionism, and the native population, the Palestinians (and not between two national movements).

We make a distinction between settler colonialism and classical colonialism. The settler colonialists are Europeans who were forced to leave Europe due to persecution or a sense of existential danger and who settled in someone else’s homeland. They were at first assisted by empires, but soon rebelled against them as they wished to re-define themselves as new nations. Their main obstacle however was not their empires, but the native population. And they acted according to what the great scholar of settler colonialism, Patrick Wolfe, called ‘the logic of the elimination of the native’. At times this led to a genocide, as happened here, at times to apartheid, as occurred in South Africa. In Palestine, the presence of the native population led to the ethnic cleansing operation of the 1948 Nakba and ever since. The settlers also saw themselves as the indigenous and perceived the indigenous as aliens.

The paradigm explains well what lay behind the ethnic cleansing operations in 1948. Regardless of the quality of the Palestinian leadership, the ability or inability of the Arab world to help, or the genuine or cynical wish of the Western world to compensate for the Holocaust, Zionism was a classical settler-colonial movement that wanted a new land without the people who lived on it. Hence, long before the Holocaust, the Zionist settlers acted upon the logic of the elimination of the natives and 1948 provided the opportunity for partial realisation of the vision of a de-Arabised Palestine.

However, in 1948, ‘only’ half of the indigenous population was expelled, and Israel succeeded in taking over 78% of the coveted new homeland. (A homeland demanded by the secular Jewish settler movement, Zionism, by using a sacred religious text, the Bible, as a scientific proof for their right to national sovereignty in the land, and hence the Palestinians were the usurpers who took it over. The first setters who came in between 1882 and 1914 could have not made it in Palestine without the help of the local Palestinians, but in their diaries and letters back home they described their local hosts as the foreigners who usurped our ancient homeland and destroyed it.) The inability to get rid of all the Palestinians and the takeover of most, but not all, of the land is an incomplete process that explains the Israeli policy towards the Palestinians ever since 1948.

This is the background for the harsh policy towards the Palestinians left within Israel, the 1948 Arabs as they are named by the Palestinians or the Israeli Arabs as they are referred to by Israel. Until 1956, this community was subjected to further ethnic cleansing operations, dozens of villages were expelled, in which there lived people regarded as citizens of the Jewish state whose Declaration of Independence promised to protect them, yet who were expelled by the settler state.

Then they were put under harsh military rule that robbed them of any normality in their life, where soldiers could arrest, shoot or banish them at will. The settler-colonial state saw its Arab citizens as aliens with a potential of becoming hostile aliens at any given moment.

The settler-colonial paradigm also explains the Israeli policy leading to the June 1967 War, as well as its policy during the early years of the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The occupation was not a defensive response to an all-Arab attack, but rather an Israeli solution to the incomplete nature of the 1948 operations.

The paradigm of settler colonialism also offers an explanation for the major decisions that Israel took after the war, decisions that expose why there was no chance from the beginning for any peace process based on a two-state solution. More than anything else, for me, it exposes the Israeli perception of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as two huge mega-prisons that by now a third generation of hundreds of thousands of Israelis is involved in policing and maintaining as a way of life that to them appears normal and acceptable, while the rest of us look on with disgust, horror and dismay at the brutality and inhumanity imposed on millions of Palestinians incarcerated there, whose only crime is being Palestinians. Nowhere else in the world do such mega-prisons exist, and yet Israel has been excused for this inhuman monstrosity it created in 1967 and continues to maintain today.

The settler state needed the remaining 22%, as the borders of 1948 were deemed indefensible and, moreover, the ancient biblical sites in the West Bank were deemed the heart of the ancient land of Israel without which the new nation-state would not thrive. Ever since 1948, important sections of the Israeli political and military elite planned takeovers of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The plans moved into a more practical stage when, in 1963, the principal politician objecting to such a takeover, David Ben-Gurion, was removed from political life. In 1963, a group of senior officers and officials drew up the ‘Shaham plan’, which would ultimately be implemented in 1967, to abolish the military rule imposed on the Palestinians inside Israel and instead impose it on those Palestinians living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip after their planned occupation.

As early as four years before the actual takeover, it was clear that with the coveted new territory, the settler state would have new demographic problems. Like all settler-colonial movements before them, space and people were the two main factors troubling the future of a settler colony. The more territory one holds, the more natives there are. The issue was how to eliminate them, and the answer and methods depended on the capacity, circumstances, and the ability of the indigenous population to resist.

In the immediate aftermath of the June 1967 War, the decision as to how to engage with the new territory while solving the new demographic challenge rested with the thirteenth government of Israel. It was the most consensual government that Israel ever had or will have. Every shade of Zionism and Jewish orthodox anti-Zionism was represented in this unity government. This explains its ability to carve out a strategy that is still adhered to today. It is based on several decisions. The first of these was the decision not to officially annex the new territories, but also never to give them up as part of the space of the future Jewish state. This is how the geographic (spatial) issue was resolved. As for the population, after some hesitation and quite substantial forced transfer of populations, the decision was made not to ethnically cleanse the population. The status of the population was to have some official connection with the previous powers, namely Jordan and Egypt, but basically, the Minister of Defence defined the new inhabitants of the greater Israel, as citizenless citizens. A worried Minister of Foreign Affairs, Abba Eban, inquired how long people could live in such a condition. ‘Oh’, Dayan answered, ‘for at least fifty years’.

The next decision was not to engage in a peace process, with the help of the Americans, that aimed to obtain international — and if possible Arab, and later on even Palestinian — legitimisation of or at least consent for Israel’s wish to have the territory without the people, and its demands that this should be the basis for a future peace process. It was taken for granted that there would be genuine public debate in Israel about the future of the territories and some friction with the US, but it was felt that at the end of the day, the Israeli interpretation of what consituted peace and what constituted a solution would prevail. Nothing that happened in the next fifty-two years indicates that these politicians were wrong to set their hopes on Palestinian fragmentation, Arab impotence, American immunity and global indifference.

The approach of having the land without the people and calling this arrangement peace was devised in June 1967. The Labour Party, still dominating Israeli and Zionist politics, always believed that some land could be conceded for the sake of demographic purity, and were thus enchanted by the colonialist idea of partition, which alas quite a few Palestinians fell for over the years. Partitioning of the new occupied territories into a Jewish West Bank and Gaza Strip and a Palestinian West Bank and Gaza Strip was the way forward.

The first partition map was presented by Yigal Allon, one of the leaders of the Labour government. The Jewish space would be determined, he said in June 1967, by colonisation. He drew a strategic map that left only densely populated Palestinian areas out of the Jewish West Bank and Gaza Strip. The problem for the thirteenth government and those that followed it, the Golda Meir and Rabin governments, was that the new messianic movement, Gush Emunim, had a different map of colonisation, one based on the Bible and the nationalistic imagination of Israeli archaeologists, who wanted to settle Jews precisely on densely populated Palestinian areas. As early as 1974, this twin effort from above and below defined the West Bank as a partitioned space between a Jewish West Bank and a Palestinian one. The former was growing all the time, while the latter was shrinking all the time.

The other constituent element of the settler-colonial policy after 1967 was the question of how to rule and police the citizenless citizens. In the last fifty-two years, the settler state has employed two models for ruling millions of citizenless citizens. Both of these models are mega-prison models, with only one difference from a real prison: that a prisoner can leave the prison and become a refugee with no right of return.

The open prison model is based on allowing freedom of movement inside the Palestinian areas and controlled movement outside the Palestinian areas and between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It gives no growing space for the Palestinians, nor any new villages or towns built on land coveted for present or future Jewish settlements. There is no resistance to the geopolitical reality imposed by Israel, and a certain level of autonomy in the running of municipal affairs. The first open prison was run between 1967 and 1987. Life was constantly monitored by the army and, from 1981 onwards, by an organisation called the Civil Administration, and ruled by a set of regulations that gave the military unlimited power in the lives of citizenless citizens. They were arrested without trial, expelled, their houses and business demolished, wounded and killed at the discretion of soldiers, quite often of lower ranks.

This form of rule prevailed first between 1967 and 1987, and then for a second time between 1993 and 2000. It has prevailed for Areas A and B in the West Bank since 2004. Every new open prison model is worse for ‘the inmates’ than the last. Privileges granted in the first term are reduced as long-term punishment for resisting the model. Remember, this is the world of jailer and warden. Thus, the second open prison, which one might call the open prison model of the Oslo Accords, and which created mini prisons in Areas A, B and C and the Gaza Strip, is far less open that its predecessor. This didactic approach of teaching the Palestinians lessons that will make them docile and disempower them to the point of submission is ingrained in the Israeli perception, and supported by Israeli orientalists.

The first Palestinian resistance to the open prison model was in the First Intifada in 1987. As a punishment, the open prison model was replaced with a maximum-security prison. Between 1987 and 1993, this included short-term punitive actions; mass arrests without trial, wounding and killing of demonstrators, massive demolition of houses, shutting down of business and the education system and, most importantly, further expropriation of land for the sake of Jewish settlements.

The Palestinians were offered a sophisticated open prison model in Oslo (regardless of how Palestinians and the wider world saw the accord). This is why the end of the occupation is not mentioned in the accord and there is no promise to end the intensive Israeli involvement in the lives of Palestinians, even if the latter were to implement every other Israeli demand of the accord.

However, this model also included a long-term, didactic punishment. From 1994 there was no longer freedom of movement within Palestinian areas, let alone outside of them, and the Judaisation of the West Bank increased. The Gaza Strip was encircled with barbed wire in 1994, and the privilege granted in the open prison model for Gazans to work in Israel was also withdrawn. A further permanent punishment was the allocation of more water to the Gush Qafif settlements, and of the decision to cut the Gaza Strip into two parts controlled by Israel.

While life under the first open prison model was unacceptable to the Palestinians, the second model was far worse, objectively, and even more importantly, because it was presented as part of a peace process. The years devoted to Oslo and its implementation had created a life under conditions far worse than those in the prior model.

The second uprising yet again generated a punitive maximum-security model: far worse in its short-term punitive actions and long-term punishments. There was now massive use of military power, including F-16 fighter jets and tanks, against the civilian population, in particular during the 2002 Defence Shield operation. The urbicide that had been witnessed in Syria, Iraq and Yemen recently was a prelude to the use of such power in the third model of the maximum-security prison imposed on Gaza after Hamas took over in 2006.

In 2007, the two models clearly transpired in Israel’s approach to ruling the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, still loyal to the thirteenth government’s main decision in 1967 not to annex, not to expel and not to withdraw. The only aspect discarded was the attempt to present this approach as a temporary measure pending peace, or to describe the open prison model as a ‘peace plan’. Even the Israeli public and politicians grew tired of this charade and adopted what Prime Minister Ehud Olmert called ‘unilateralism’. Where there is collaboration there is an open prison model, in Areas A and B, with long-term punitive actions: hundreds of checkpoints and an apartheid wall meant to humiliate millions of people into submission in the belief that this will discourage a third uprising. The checkpoints are the recruiting ground for a cruel network of informants that is expected to attack the dignity and self-respect of a whole nation that miraculously still succeeds in remaining human and steadfast. There were also closures of whole towns and villages, with only one exit controlled day and night by the army or, recently, by private companies.

Where there is resistance, as in the Gaza Strip, the maximum-security prison has turned into a ghetto, with Israel rationing food and calories, undermining the health and economy to the point of creating a human catastrophe, as acknowledged by the UN’s prediction of the de-development and unsustainability of the Gaza Strip for years onwards.

The military punishment is none other than a set of war crimes and an incremental genocide of the Palestinian people in the Gaza Strip. This is achieved by dehumanising the Palestinians, and their children, depicting them as soldiers in an enemy’s army that can legally be targeted by the Israeli army as enemy forces (this was the same doctrine used in the Nakba: a village was an army base, a neighbourhood an army outpost, and those who lived in them were enemy soldiers, not men, women and children).

All the Zionist parties of Israel in one form or another subscribe to these two models as the only possibility. The dominant political powers in Israel wish to import this twin model into Israel proper vis-à-vis the Palestinians in Israel, and they might succeed in doing so. The recently passed nationality law is an indication that this is indeed their future policy.

The only way of stopping this is first to recognise the settler-colonial nature of Israel and as a result to understand that what is needed is not peace but decolonisation, not just of the areas occupied in 1967, but of the whole of historical Palestine, which includes implementation of Palestinian refugees’ right of return.

Secondly, we should revisit the two-state solution as an open prison model and think hard about how one might create one democratic state for all, taking into account two things: 1. that the representative bodies of the Palestinians, until today, still subscribe to the two-state solution, and 2. that there is already one settler apartheid, Israel, all over historical Palestine. We need a Palestinian change of mind, and international endorsement and BDS of such a way forward, and then we might actually succeed in generating a change from within Jewish society. When all of these elements are finally in place, there will be a hope for this torn country and its people.

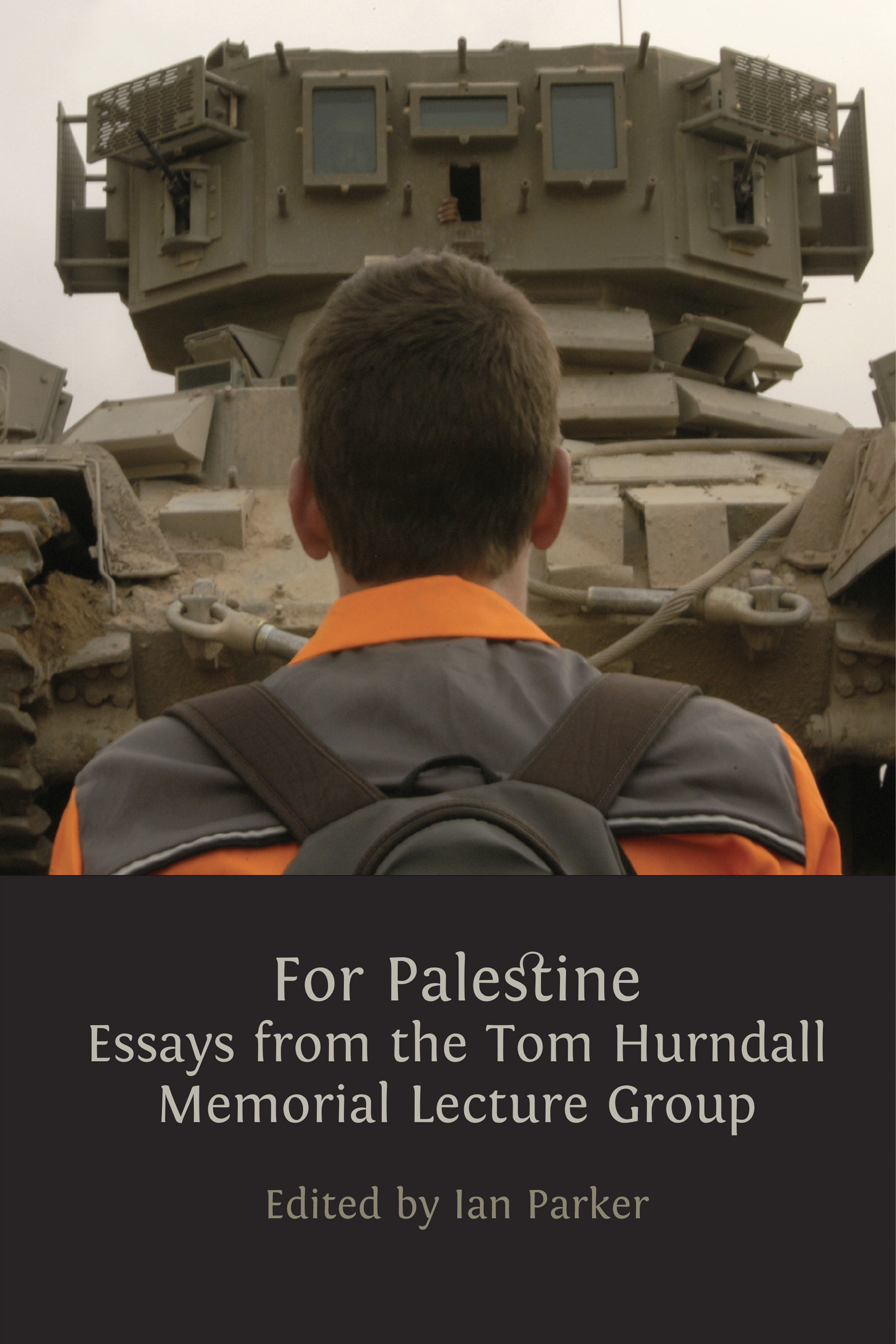

Fig. 6 Tom Hurndall, Destruction in Rafah, Gaza, April 2003. All rights reserved.