5. Reflections on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

In this chapter I argue that the state of Israel is legitimate, but only within its original boundaries, and that the Palestinians are the main victims of the conflict, victims of Israeli colonialism. The history of the region over the last sixty years can be convincingly explained in terms of the strategy of the ‘iron wall’, first expounded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, which advocates negotiation only from a position of unassailable strength. The basic deal of ‘land for peace’ expressed in UN Resolution 242 was sound, but never effectively implemented and Yitzhak Rabin, the only Israeli prime minister prepared to negotiate, was murdered. The recent, brutal onslaughts on Gaza give little grounds for optimism.

These are reflections about a subject which has preoccupied me for the best part of four decades. Most of these reflections are included in one form or another in my book Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations, published by Verso in 2009. The volume gathers a number of essays published in the previous twenty-five years on the theme of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Some of these essays are scholarly articles with footnotes; some are more polemical comment pieces for newspapers; others are review essays which originally appeared in the London Review of Books.

The paperback edition of this book was reviewed by Rafael Behr in The Observer on 3 October 2010. Behr perfectly encapsulates the book’s main topic:

Several times in Israel and Palestine, his collection of essays on the Middle East, Avi Shlaim refers to Zionism as a public relations exercise. It sounds glib. But Shlaim […] isn’t talking about sales and marketing. He means a configuration of history that casts one side of a dispute as victim and the other as aggressor in the eyes of the world. In Zionism’s case, the story told is of Israel restored to the Jews, carved from empty desert, ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’. By extension, Arab hostility to Israel’s creation was irrational cruelty directed against an infant state. It is a romantic myth requiring a big lie about the indigenous Palestinian population. Their expropriation was, in Shlaim’s analysis, the ‘original sin’ that made conflict inevitable. He also sees the unwillingness of Israeli leaders to recognise the legitimacy of Palestinian grievance as the reason why most peace initiatives have failed. There was a time of greater pragmatism, when ordinary Israelis at least were ready to swap land for peace. But that trend was crushed by a generation of turbo-Zionists from the Likud party. Instead of trading occupied territory for normal diplomatic relations with the Arab world, they aggressively colonised it, waging demographic war to shrink the borders and diminish the viability of any future Palestinian state. Palestinian leaders are not spared Shlaim’s criticism. He singles out Yasser Arafat’s decision to side with Saddam Hussein in the first Gulf war, for example, as a moral and political blunder. But most of the essays are about the cynical manoeuvrings of Israeli politicians. As a collection it is plainly one-sided; Shlaim does not aim at a comprehensive overview of the conflict so much as a running rebuttal of Israel’s version of it; an insurgency in the public relations war.1

I plead guilty to the charge of being one-sided. My sympathy is with the Palestinians because they are the victims of this tragic conflict, the victims of a terrible injustice. Injustice is by definition one-sided: it is inflicted by one party on another. I am a politically-engaged writer and I believe in justice for the Palestinians. By justice I mean an end to the occupation and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank with a capital city in East Jerusalem. The Palestinian state I envisage would be alongside Israel, not instead of Israel. In short, I am a supporter of a two-state solution. If this makes me one-sided, then so be it.

What I propose to do is not to try to summarise the book, but to offer you some reflections on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from an historical perspective. Everything to do with Israel is controversial, so let me pre-empt misrepresentations by stating where I stand. I have never questioned the legitimacy of the Zionist movement or that of the State of Israel within its pre-1967 borders. What I reject, and reject uncompromisingly, is the Zionist colonial project beyond the 1967 borders.

I belong to a very small group of Israeli scholars who are known collectively as ‘the new historians’ or ‘the revisionist Israeli historians’. The original group included Simha Flapan, Benny Morris, and Ilan Pappe. We were called the new historians because we challenged the standard Zionist version of the origins, character, and course of the Arab-Israeli conflict. In particular, we challenged the many myths that have come to surround the birth of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli war.

The first thing to say about ‘old history’ is that it is a nationalist version of history. The nineteenth-century French philosopher, Ernest Renan, wrote that ‘Getting […] history wrong is part of being a nation’. Nationalist versions of history do indeed have this feature in common: they tend to be simplistic, selective, and self-serving. More specifically, they are commonly driven by a political agenda. One political purpose they serve is to unite all segments of society behind the regime. The other common purpose is to project a positive image of the nation to the outside world. Conventional Zionist history is no exception — it is a tendentious and self-serving version of history.

The late Edward Said was not himself a historian, but he attached a great importance to the ‘new history’, to critical historiography about Israel’s past. The educational value of the ‘new history’, he thought, is three-fold: first, it educates the Israeli public about the Arab view of Israel and the conflict between the Arabs and Israel; second, it offers the Arabs an honest version of history, genuine history which is in line with their own experience, instead of the usual propaganda of the victors; third, the ‘new history’ helps to create a climate of opinion, on both sides of the divide, which is conducive to progress in the peace process. (One of the thirty essays in my book is on ‘Edward Said and the Palestine Question’.)

There are two aspects to the Arab-Israeli conflict: the inter-communal and the inter-state. The inter-communal aspect is the dispute between Jews and Arabs in Palestine; the inter-state aspect is the conflict between the State of Israel and the neighbouring Arab states. The neighbouring Arab states intervened in this conflict on the side of the Palestinians in the late 1930s and they have remained involved one way or another to this day. In the late 1970s, however, President Anwar Sadat of Egypt began the trend towards Arab disengagement from the conflict.

The Zionist movement was remarkably successful in the battle to win the hearts and minds of people. Zionism is arguably the second greatest PR success story of the twentieth century — after the Beatles! Zionist spokesmen skilfully presented their movement as the national liberation movement of the Jews, disclaiming any intention of hurting or dispossessing the indigenous Arab population. The founding fathers of Zionism promised that their movement would adhere to universal values like freedom, equality, and social justice. Based on these ideals, they claimed to aspire to develop Palestine for the benefit of all these people, regardless of their religion or ethnicity.

A huge gap, however, separated the proclaimed ideals of the founding fathers from the reality of Zionist treatment of the Arab population of Palestine on the ground. This gap was filled by Zionist spokesmen with hypocrisy and humbug. Even as they oppressed and dispossessed the Palestinians, the Zionists continued to claim the moral high-ground. In the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, they persisted in portraying Zionism as an enlightened, progressive, and peace-loving movement and its opponents as implacably hostile fanatics. One of the achievements of the ‘new history’ is to expose this gap between rhetoric and reality.

From the early days of the Zionist movement, its leaders were preoccupied with what they euphemistically called ‘the Arab question’. This was also sometimes referred to as ‘the hidden question’ — the presence of an Arab community on the land of their dreams. And from the beginning, the Zionists developed a strategy for dealing with this problem. This was the strategy of the ‘iron wall’, of dealing with the Arabs from a position of unassailable military strength.

In 2000 I published a book under the title The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. It covered the first fifty years of statehood, from 1948 to 1998. This is a fairly long history book but I can summarise it for you in a single sentence: Israel’s leaders have always preferred force to diplomacy in dealing with the Arabs. Ever since its inception, Israel has been strongly predisposed to resort to military force, and reluctant, remarkably reluctant, to engage in meaningful diplomacy in order to resolve the political dispute with its neighbours. True, in 1979 Israel concluded a peace treaty with Egypt and in 1994 it concluded a peace treaty with Jordan, but the overall pattern remains one of relying predominantly on brute military force.

The architect of the iron wall strategy was Ze’ev Jabotinsky, an ardent Jewish nationalist and the spiritual father of the Israeli Right. In 1923 Jabotinsky published an article titled ‘On the Iron Wall (We and the Arabs)’ with an analysis of ‘the Arab question’ and recommendations on how to confront it. He argued that no nation in history ever agreed voluntarily to make way for another people to come and create a state on its land. The Palestinians were a people, not a rabble, and Palestinian resistance to a Jewish state was an inescapable fact. Consequently, a voluntary agreement between the two parties was unattainable. The only way to achieve the Zionist project of an independent Jewish state in Palestine, Jabotinsky concluded, was unilaterally and by military force. A Jewish state could only be built behind an iron wall of Jewish military power. The Arabs will hit their heads against the wall, but eventually they will despair and give up any hope of overpowering the Zionists. Then, and only then, will come the time for stage two, negotiating with the leaders of the Palestine Arabs about their rights and status in Palestine.

The iron wall was a national strategy for overcoming the main obstacle on the road to statehood. The Arab revolt of 1936–1939 seemed to confirm the premises of this strategy. The point to stress is that this was not the strategy of the right, or of the left, or of the centre. Based on a broad consensus, it became the national strategy for dealing with the Arabs from the 1930s onwards. Regardless of the political colour of the government of the day, this was the dominant strategy under successive Israeli prime ministers from David Ben-Gurion, the founder of the state, to Binyamin Netanyahu, the current incumbent.

In my book I argue that the history of the state of Israel is the vindication of the strategy of the iron wall. First the Egyptians, in 1979, then the PLO, in 1993, then Jordan, in 1994, all negotiated peace agreements with Israel from a position of palpable weakness. So the strategy of ‘negotiations from strength’ worked. The disappointment is that, in Israel’s entire history, only one prime minister had the courage to move from stage one, the building of military power, to stage two, negotiations with the Palestinians. That prime minister was Yitzhak Rabin and the transition occurred during the secret talks in the Norwegian capital between Israeli and PLO representatives which produced the 1993 Oslo Accords.

In the rest of what I have to say, my reflections will revolve around four major landmarks in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the 1948 war for Palestine; the June 1967 war; the 1993 Oslo Accords; and the Gaza war of December 2008.

The War for Palestine

The first Arab-Israeli war was, in fact, two wars rolled into one. The first phase, from the passage of the UN partition resolution on 29 November 1947 to the expiry of the British Mandate over Palestine on 14 May 1948, was the war between the Jewish and Arab communities in Palestine and it ended with a crushing defeat for the Palestinians and in the decimation of their society. The second phase began with the invasion of Palestine by the regular armies of the neighbouring Arab states on 15 May 1948 and it ended with a ceasefire on 7 January 1949. This phase, too, ended with an Israeli triumph and a comprehensive Arab defeat.

The main losers in 1948 were the Palestinians. Around 730,000 Palestinians, over half the total population, became refugees and the name Palestine was wiped off the map. Israelis call this ‘the War of Independence’ while Palestinians call it the Nakba, or catastrophe. Whatever name is given to it, the war for Palestine marked a major turning point in the history of the modern Middle East.

The debate in Israel between the ‘new historians’ and the pro-Zionist ‘old historians’ initially revolved round the fateful events of 1948. There are several bones of contention in this debate. For example, the old historians claim that the Palestinians left Palestine of their own accord and in the expectation of a triumphal return. We say that the Palestinians did not leave of their own accord; that the Jewish forces played an active part in pushing them out. Another argument concerns Britain’s intentions as the Mandate over Palestine approached its inglorious end. The old historians claim that Britain’s main aim in the twilight period was to abort the birth of a Jewish state. On the basis of the official British documents, we argue that Britain’s real aim was to abort the birth of a Palestinian state. There is another issue in dispute: why did the political deadlock persist for three decades after the guns fell silent in 1949? The old historians say it was Arab intransigence; we say it was Israeli intransigence. In short, my colleagues and I attribute to Israel a far larger share of the responsibility for the root causes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than the orthodox Zionist rendition of events.

It seems to me undeniable that the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 involved a monumental injustice to the Palestinians. And yet I maintain that the State of Israel within its original 1949 borders is legitimate. Some people say that this is inconsistent: how can a state built on injustice be legitimate? My answer to my critics is twofold. First of all, there was the all-important United Nations resolution of 29 November 1947, which called for Mandatory Palestine to be divided into two states, one Arab and one Jewish. This resolution constitutes an international charter of legitimacy for the creation of a Jewish state. Secondly, in the first half of 1949, Israel negotiated, under UN auspices, a series of bilateral armistice agreements with all its neighbours: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. These are the only internationally recognised borders that Israel has ever had, and these are the only borders that I still recognise as legitimate.

My graduate students at Oxford challenge me relentlessly on this point. In the first place, they claim that the UN partition resolution was unfair to the Palestinians because it was their country that was being divided. My reply is that this argument confuses fairness with legality. The partition resolution may well have been unfair but since it was passed by a two-thirds majority of the votes in the General Assembly, it cannot be regarded as illegal. A further argument that my students deploy is that even if Israel was legitimate at birth, its occupation of the rest of Palestine since June 1967 and the apartheid system it has installed there undermines its legitimacy in the eyes of the world. This argument is much more difficult to counter. By its own actions, by maintaining its coercive control of the occupied Palestinian territories, and by its callous treatment of innocent Palestinian civilians, Israel has torn to shreds the liberal image it enjoyed in its first two decades of its existence.

The June 1967 War

The second major watershed is the June 1967 war, popularly known as the Six-Day War. The main consequence of that war was the defeat of secular Arab nationalism and the slow emergence of an Islamic alternative. In Israel, the resounding victory in the Six-Day War reopened the question of the territorial aims of Zionism. Israel was now in possession of the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights. The question was what to do with these territories and to this question two very different answers were given. The moderates favoured the restoration of the bulk of these territories to their owners in return for recognition and peace. The secular and religious nationalists, on the other hand, wanted to hold on to these territories, and especially to the West Bank, which they regarded as an integral part of the Land of Israel.

The United Nations had its own solution to the conflict: Security Council Resolution 242 of November 1967, which proposed a package deal, the trading of land for peace. Israel would give back the Occupied Territories with minor border modifications and the Arabs would agree to live with Israel in peace and security. One feature of Resolution 242 which displeased the PLO was that it referred to the Palestinians not as a national problem but merely as a refugee problem. Resolution 242 has been the basis of most international plans for peace in the region since 1967.

History shows that this formula is sound. Whenever it was tried, it worked. In 1979, Israel gave back every inch of the Sinai Peninsula and it received in return a peace treaty which is still valid today. In 1994, Israel signed a peace treaty with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and paid the price of returning some land it had poached along their common border in the south. This treaty, too, is still effective today. If Israel wanted to have a peace agreement with Syria, it would be within its reach through negotiations. But there is a price tag: complete Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights. The problem is that on the northern front, as on the eastern front, Israel prefers land to peace.

Quite soon after the ending of hostilities in June 1967, Israel started building civilian settlements in the Occupied Territories. These settlements are illegal, all of them, without a single exception, and they are the main obstacle to peace. Thus, as a result of its refusal to relinquish the fruits of its military victory, little Israel became a colonial power, oppressing millions of civilians in the Occupied Territories. It is largely for this reason that in the aftermath of its victory in the June 1967 war, Israel began to lose its international legitimacy while the PLO began to gain it.

The Oslo Accords

Like all other significant landmarks in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Oslo Accords has generated a great deal of controversy. It was signed on the lawn of the White House on 13 September 1993 and it represented a historic compromise between the two warring peoples. The historic compromise was clinched by a hesitant handshake between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. Despite all its shortcomings, the Oslo Accords constituted a historic breakthrough in the struggle for Palestine. It fully deserved the over-worked epithet ‘historic’ because it was the first agreement between the two principal parties to the conflict.

The Oslo Accords did not promise or even mention the brave phrase ‘an independent Palestinian State’. Its more modest aim was to empower the Palestinians to run their own affairs, starting with the Gaza Strip and the West Bank town of Jericho. The Accord is completely silent about all the key issues in this dispute. It says nothing about the future of Jerusalem, it says nothing about the right of return of the 1948 Palestinian refugees, it says nothing about the status of Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories, and it does not indicate the borders of the Palestinian entity. All these key issues were left for negotiations towards the end of the transition period of five years. So Oslo was basically an experiment in Palestinian self-government.

For Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s security was the paramount consideration. Provided Israel’s security was safeguarded, he was prepared to move forward and he did take another significant step forward by signing, on 28 September 1995, the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, commonly known as Oslo II. Rabin’s murder, two months later, dealt a body-blow to the fledgling peace process. We do not know what might have happened had Yitzhak Rabin not been assassinated. What we do know is that after his murder the peace process began to break down.

Why did the Oslo peace process break down? There are two conflicting answers. One answer is that the original Oslo Accords was a bad deal for Israel and that it was doomed to failure from the start. My answer is that Oslo was not a bad agreement, but rather a modest step in the right direction equipped with a sound gradualist strategy. The peace process broke down because Rabin’s Likud successors, led by Binyamin Netanyahu from 1996 to 1999, reneged on Israel’s side of the deal. There were other reasons for the breakdown of the peace process, notably the resort to terror by Palestinian extremists. But the single most fundamental reason was the continuing colonisation of the West Bank. This happened under both Labour and Likud governments after the signature of the Oslo Accords. It was a violation of the spirit, if not of the letter of the Oslo Accords.

The building of Jewish settlements on occupied land is not just a blatant violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention but an in-your-face aggression against the Arabs who live there. So is the so-called ‘security barrier’ that Israel is building on the West Bank. Settlement expansion on the West Bank can only proceed by confiscating more Palestinian land. It amounts to ruthless land-grabbing. And it is simply not possible to engage in land-grabbing and to pretend to be doing peace-making at the same time. Land-grabbing and peace-making are incompatible: they do not go together. It is one or the other and Israel has made its choice. It prefers land to peace with the Palestinians and that is why the Oslo peace process broke down.

The Gaza War

The fourth and final watershed in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on which I would like to offer a few reflections is the Gaza war unleashed by Israel on 27 December 2008. This was the climax of the strategy of the iron wall, of shunning diplomacy and relying on brute force to impose Israel’s will on the Arabs. ‘Operation Cast Lead’, to give the war its bizarre official title, was not really a war but a one-sided massacre.

On 7 January 2009, while the operation was in progress, I published a long article in the G2 section of the Guardian. The title I gave the article was ‘Israel’s Insane Offensive’ but the Guardian, typically, forgot to print the title. As will be clear from the title, I was extremely angry when I wrote this article. The article began by quoting a memo that Sir John Troutbeck, a senior official in the Foreign Office, wrote on 2 June 1948, to the Labour Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin. Troutbeck castigated the Americans for creating a gangster state headed by ‘an utterly unscrupulous set of leaders’. I used to think that this judgement was too harsh, but Israel’s vicious assault on the people of Gaza, and the complicity of George W. Bush in this assault, reopened the question.

Very briefly, my view of the Gaza War is that it was illegal, immoral, and completely unnecessary. The Israeli government claimed that the war in Gaza was a defensive operation. Hamas militants were firing Qassam rockets on towns in the south of the country and it was the duty of the Israeli government to take action to protect its citizens. This was the objective of Operation Cast Lead. The trouble with this official line is that there was an effective cease-fire in place in the months preceding the war. Egypt brokered the cease-fire between Israel and Hamas in June 2008. This cease-fire had a dramatic effect in de-escalating the conflict. In the first six months of that year, the average monthly number of rockets launched from Gaza on southern Israel was 179. After the cease-fire came into effect, the monthly average dropped to three rockets between July and October. It was Israel that violated the cease-fire. On 4 November 2008, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) launched a raid into Gaza that killed six Hamas fighters, thus bringing the cease-fire to an abrupt end. If all that Israel really wanted was to protect its citizens in the south, then all it had to do was to follow the good example set by Hamas in respecting the cease-fire.

The Egyptian-brokered cease-fire agreement also stipulated that Israel would lift the blockade of Gaza. After Hamas seized power in Gaza in June 2007, Israel started restricting the flow of food, fuel, and medical supplies to the strip. A blockade is a form of collective punishment that is contrary to international law. But even during the four months of the cease-fire, Israel failed to lift the blockade. Despite all the international protests, and despite all the boats organised by peace activists to carry humanitarian aid to Gaza, the savage blockade is still in force today.

During the war, the IDF used its superior power without any restraint. The casualties of the Gaza war were around 1400 Palestinians, most of them innocent civilians, and 13 Israelis. In the course of this war, the IDF deliberately inflicted a great deal of damage on the infrastructure of the Gaza Strip. It destroyed thousands of private houses, government buildings, police stations, mosques, schools, and medical facilities. The scale of the damage suggests that the real purpose of the war was offensive, not defensive.

It seems to me that the undeclared aims of the war were twofold. One aim was politicide, to deny the Palestinians any independent political existence in Palestine. The second aim of the war was regime change in Gaza, to drive Hamas out of power there. In the course of the war, war crimes were committed by both sides. These war crimes were investigated by an independent fact-finding mission appointed by the UN Human Rights Council and headed by Richard Goldstone, the distinguished South African judge. Goldstone found that Hamas and the IDF had both committed violations of the laws of war. The IDF, however, received more severe strictures on account of the scale and the seriousness of its violations.

My conclusion may come to you as a shock but it is not a conclusion I have reached lightly: Israel has become a rogue state. My academic discipline is International Relations. In the academic literature in this field, three criteria for a rogue state are usually put forward: one, a state that habitually violates international law; two, a state that either possesses or seeks to develop weapons of mass destruction; and three, a state which resorts to terror. Terror is the use of force against civilians for political purposes. Israel meets all three criteria and therefore, in my judgement, it is now a rogue state. It is because Israel behaves like a rogue state that it is well on the way to becoming a pariah state.

Dr Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president, wrote in his autobiography that it is by its treatment of the Palestinians that Israel will be judged. It is accordingly by this yardstick that I judge Israel — and I find it sadly wanting. This is a melancholy conclusion to a rather depressing set of reflections. Let me therefore end on a more hopeful note. The hopeful note comes from a letter written in September 2010 by Eyad Sarraj, a psychiatrist from Gaza, to Lynne Segal, one of the sponsors of the Jewish aid boat to Gaza:

Dear Lynne,

You write to me, and I must tell you that I am very inspired by the coming voyage of a Jewish boat to break the siege on Gaza. I have helped and worked with and received other boats, but this is the most significant one for me, because it carries such an important message. It brings to us and tells the world that those we Palestinians thought we should hate as our enemies can instead arrive as our friends, our brothers and sisters, sharing a love for humanity and for our struggle for justice and peace. I will wait with anticipation to shake hands with them and hold them dear in close embrace. They are my heroes.

Please, never despair that you cannot bring peace, and never give up work for a just world. When I see, read, and relate to Jews who believe in me as an equal human being, and who tell me that their definition of humanity is not complete without me, I become stronger in my quest for justice and peace. I learnt long ago that there are Jews in and outside Israel who belong with me in the camp of friends of justice and peace. I have always strongly believed that we can live together, that we must live together. We have no other choice except to live together. It is because of people like you, and events like this, that I will never give up on the hope.

With my best and warmest

Eyad Sarraj

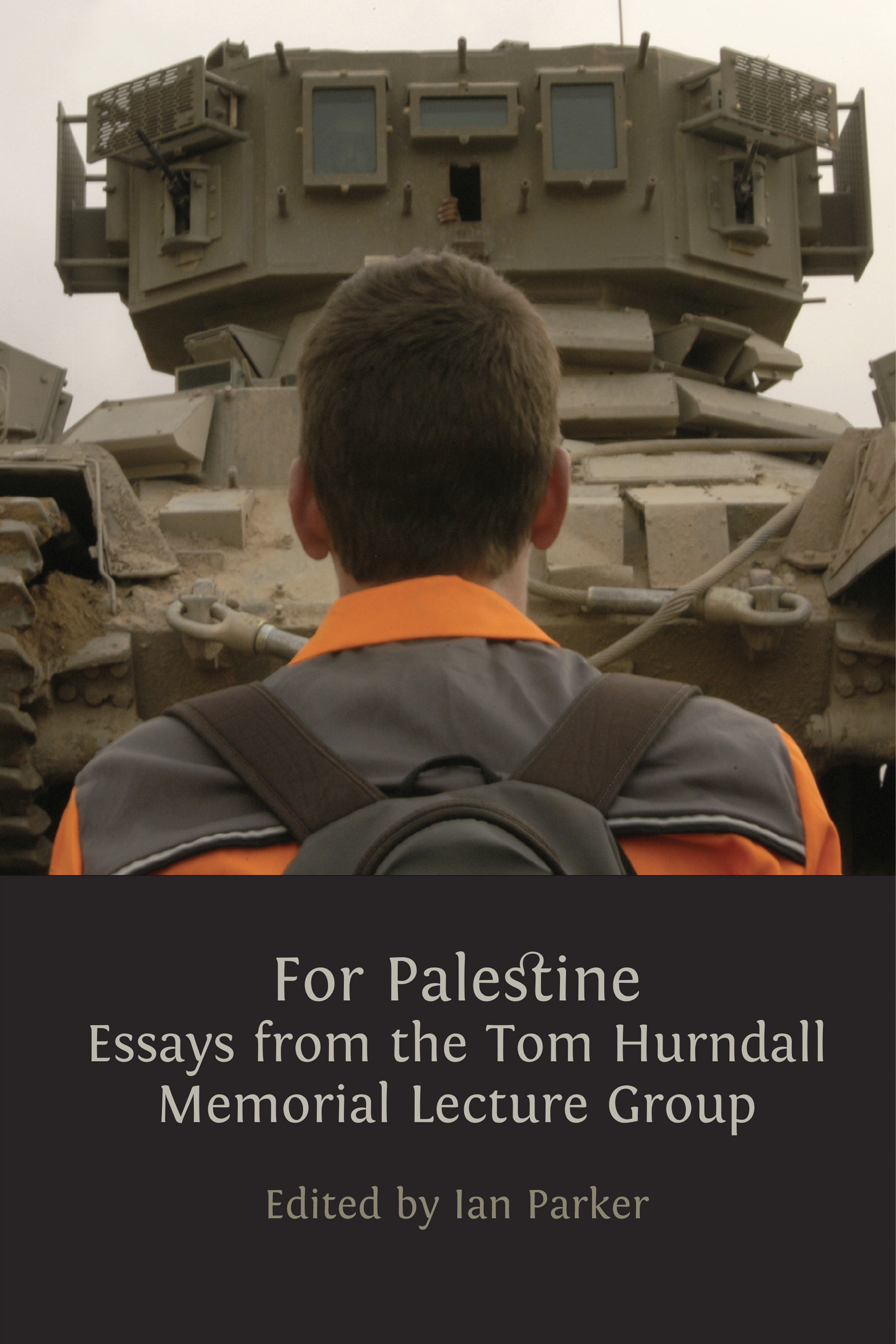

Fig. 8 Tom Hurndall, Palestinian children playing in the street in Jerusalem, April 2003. All rights reserved.