7. Dismantling the Image of the Palestinian Homosexual: Exploring the Role of Alqaws1

© 2023 Wala AlQaisiya et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345.08

The Zionist colonisation of Palestine holds at its premise racial, sexual, and gendered discourses through which colonial power is exercised. It is through the production and creation of certain types of knowledge and specific domains of truth that the colonial regime perpetuates and reinforces its mechanisms and modes of governments on the colonisers, making them internalise a certain conduct. This chapter seeks to understand the means through which the Zionist colonial regime influences the production of specific objects of knowledge: sexuality and the image of the homosexual in Palestine. It wants to pinpoint the ways through which its power hinges on the bodies and desires of the colonised and, specifically, how the image of homosexuals came to be perceived and understood in determined ways within the Palestinian context and throughout its recent history.

It is from the unfolding presentation of the points of intersection between a determined structure of colonial power and its knowledges of sexuality that the role of indigenous feminist/queer organising becomes fundamental. As Palestinian activists and academics that are committed to engaged analyses and praxis towards decolonising gender and sexuality in our communities, we see that highlighting the work of alQaws for Gender and Sexual Diversity and its relevance to the Palestinian context and struggle is a necessary task, being an open feminist queer space that aspires to ‘disrupt sexual and gender based oppression and challenge regulation, whether patriarchal, capitalist or colonial of our sexualities and bodies’.2 AlQaws unveils how the decolonisation of a certain type of knowledge on sexuality and its deriving modes of conduct is what can lay the foundation for a radical disruption of the colonial Zionist structure.

The first part of this chapter investigates the recent historical determination of power and knowledge that shaped the image of the Palestinian homosexual, enabling the formulation of two specific portraits of the Palestinian queer: the collaborator and the Israelised, leading to the image of the Westernised agent. In a constant effort to interrogate and challenge those structures of power that allowed their promulgation, the second part draws on how Pinkwashing was specifically adopted as a Zionist colonial tactic through which the image of the Palestinian victim queer with its racial and normalising logic around meanings of sexuality and homosexuality came to be enabled and constructed. This is followed with an analysis of alQaws’s work and the relevance of their local strategies to challenge such narratives and essentially dismantle the image that has been ascribed to the Palestinian homosexual.

The Image of the Homosexual: Major Historical Events

From our own personal experiences and from working in the field, we know that the image of the homosexual in the Palestinian context can be summed up by the ‘Other’. As people living under a settler-colonial regime, this Other came to be constructed in relation to the coloniser and the Western values it bears and represents. Thus the image of the Palestinian homosexual at its worst links to that of the collaborator, a person who is involved in directly giving out information to the coloniser and, at its best, relates to an Israelised person who has adopted Israeli ways of living. This also relates to the image people have of the Westernised agent, or those infamously described as complicit in the project of ‘transforming their cultures into copies of Euro-America’.3 In order to understand the means by which this image came to the fore in Palestinian society, one has to trace discourses and events in search of what Foucault identifies as ‘instances of discursive production … of the production of power [and] the propagation of knowledge, which makes possible ‘a history of the present’. (quoted in Sullivan, 2003, 1). The following focuses on events starting from the First Intifada, through Oslo, continuing to the current political situation where intersections between politics and sexuality come to the fore in the Palestinian context. This, in turn, explains the consolidation of the current image of the Palestinian homosexual as rooted in the collaborator and/or Israeli and Westernised agent image that alQaws works on dismantling.

As the eruption of the Palestinian First Intifada (1987–1993) came to signify the epitome of a national struggle against the fist of the Zionist colonial regime, it also marked a historical moment for the consolidation of Palestinian nationalist agency, with its gendered and ultimately heterosexual implications. Joseph Massad (1995) traces the ‘conceiving of the masculine’ in Palestinian nationalist discourses which come to echo the masculinist heteronormative seeds found earlier in European and even Zionist national projects. Thus, the Intifada rose to depict the long awaited ‘Palestinian wedding’ as the communiqués of the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU) came to describe it; manifesting the ‘apogee of heterosexual love’ where ‘the heterosexual reproduction of the family is at the centre of the nationalist project’ (Massad, 1995, 477). Whilst the Intifada was at the peak of a national project which also sought to define Palestinianness against any colonial contamination, as Massad (1995) describes it, Israel was doing its best to intensify tactics aiming to foster its ideological foundation that renders natives’ bodies and land ‘inherently rapable and invadable’ (Smith, 2008, 312).

For Israel, the Intifada was an underground movement, with elements of unpredictability and spontaneity, which made it very difficult to contain by Israeli intelligence services. This is where Israel used tactics of infiltrating Palestinian factions in order to break their work through coercing Palestinian individuals into collaboration. This tactic was implemented through the usage of threats and blackmail against the docile bodies it targeted, through control and observation, and produced as mediums for the inscription of its power. Homosexuality, pre-marital sex as well as drugs and/or alcohol use, amongst other activities that were socially frowned upon in Palestinian society, were utilised to coerce Palestinians into working with Israeli authority if they did not wish to face the consequences of being publicly exposed. This took place at the time when the image of the homosexual as a collaborator as well as Israelised came to be enforced. The reaction of Palestinian factions, which defined these immoral behaviours as a threat that needed to be uprooted from political activism, was short-sighted and legitimised further the blackmail of Palestinians by the Israeli intelligence forces. Moreover, these same tactics were later used by different Palestinian factions and armed groups to discipline non-conforming behaviours, gender expressions, and those who were suspected to be homosexual during the anarchy of the late 1990s to early 2000s.

Such strategies of “cleansing” society, echoing the Foucauldian understanding of power in its sanitising form, were part of the bigger power paradigm that the signing of the Oslo Accords, the new era of so-called economic peace, between Israel and the PLO brought to the fore. The establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a governing body, which came as a means of ‘resecuring the authoritative leadership of the Diaspora-based elite’ (Parsons, 2005), helped to consolidate long-enshrined ideals of the nationalist agent that was not only masculine but also ‘bourgeois in-the-making’ (Massad, 1995, 479). The creation of a Palestinian bureaucratic elite within a PA’s authoritarian and neo-patrimonial regime was being encouraged and sustained — this time — by the international community (Le More, 2008, 6). Their funding for the new entity continued so long as it inflicted on the Palestinians the penalties required for noncompliance with the new sphere of securitisation and diplomacy through which Israel continued to retain its control (Le More, 2008, 6). As internal volatility grew in the late 1990s due to Israel’s expansionist regime and intensified closure policies, the same donor community that used to ‘turn a blind eye to reports of mismanagement corruption and human rights abuses’ started proposing changes in the PA institutions (Le More, 2008, 6). Two years after the eruption of the Second Intifada in 2000, a marker of PA’s inability to guarantee Israel’s security, proposals to reform PA institutions solidified and became more attuned towards a new leadership that could ‘deter terror’ following the agenda of good governance and human rights. Such ideals came forth within a project of modernity whose ontological foundations continue to rely on the construction of its oriental Other who is always failing. One could here be reminded of Žižek’s useful understanding of ideology through Lacan that ‘every perception of a lack or a surplus’ always involves a disavowed relation of domination (Žižek, 1995, 11). In this case, the ‘not enough of this too much of that’ is simply another colonial tool under the disguise of ‘not enough of democracy, too much of religion’, ‘not enough of modernity, too much homophobia’, etc.

From here, one comes to understand the setting of the criteria for LGBT rights in accordance with the frame of ‘sexually progressive’ countries that define a universal model to follow (Butler, 2010, 110). Massad (2007, 161) draws on US discourse on human rights which engendered the proliferation of the Gay International agenda and framework where ‘western male white-dominated organizations’ advocate for rights of ‘gays and lesbians all over the world’. Such universalisation of LGBT rights which binds LGBT movements elsewhere to forms of organising and gains made in the Stonewall era is what Jasbir Puar draws on in her definition of homonationalism, where LGBTQ people all over the world ‘experience, practice and are motivated by the same desires and their politics are grounded in an understanding that ties the directionality of their love and desire to stable identity from which to make political claims’ (Mikdashi, 2011). With Israeli LGBT people following the same trajectory, Israel’s ‘gay decade’ came forth following the decriminalisation of sodomy in 1988 (Gross, 2001). This in turn triggered an interest in the LGBT legal status under the PA whereby the ‘colonizer’s standards and achievements became the yardstick by which the colonized were measured and to which they had to conform’ (Maikey, 2012), ignoring the fact that the same ‘anti-sodomy’ laws were removed from the Jordanian penal code, which the PA inherited in 1957. Such Western interests and findings towards the status of gay rights in Palestine after Oslo enforced the image of the Palestinian homosexual as a Western agent.

Besides the imperial and coloniser standards that were shaping the discourse around nation building and gay rights, another, no less worrying discourse began to arise among Palestine solidarity activists who took the South African model of endorsement of constitutional protection in 1996, following the dismantlement of the apartheid regime, as the bar by which other nationals were to be judged. These examples and dynamics of the International and its homogenising force towards the same trajectory of development within the reductive frame of liberal discourses of rights ignores and glosses over native experiences of sexual politics. This includes the dynamics that shaped Palestinian LGBT and other feminist groups before and after the Second Intifada who started to formulate a separate agenda from their Israeli partners. Palestinian queer activists, who later established alQaws, stopped going to the Israeli Jewish organization Jerusalem Open House as their identification with the Palestinian liberation struggle was reinforced during the Second Intifada and the brutal killings of Palestinian demonstrators inside Israel. These events came to confirm once again the genocidal premise of the settler-colonial regime which traps the natives within the realm of the homo sacer;4 one that leaves us with the critical question regarding the relevance of human rights for those who are already ceaselessly and systematically reduced by the settler-colonial regime to the realm and reality of no rights.

Gaza came to represent such a reality following the Palestinian political disintegration after the 2006 elections leading to donors’ imposed sanctions in disapproval of Hamas and finally Israel’s imposed siege on the strip since 2007. That was also the year when alQaws officially separated from the Jerusalem Open House as Palestinian queer consciousness was emerging in relation to the political reality in which it was embedded. The Israeli aggression on Gaza in 2009 further solidified a more radical political discourse amongst Palestinian queers in alQaws. It also mapped a further separation from Israeli LGBT politics, which were committed to emblems of Israeliness, including service in the army, through which their entry into Israeli consensus was guaranteed (Walzer, 2000, 235). Following the shootings at Bar-Noar in 2009 (the attack in a gay bar in Tel Aviv which led to the killings of two people), some Palestinian queers were banned from expressing their solidarity in fear of them ‘talking politics’. Israeli right-wing politicians, who had praised the killings of Gazans a few months earlier, proclaimed a ‘Do Not Kill’ message to the rhythm of the Israeli national anthem at the vigil; a song celebrating the exclusively Jewish nature of the ‘land of Zion’. This dynamic further exposed Israeli LGBT politics as an expression of queer modernity — progressive and gay-loving — that relies at its essence on and works to perpetuate and naturalise the settler-colonial regime and its logic of native exclusion and elimination (Morgenson, 2011, 16).

The exclusionary essence of the settler-colonial regime comes within a global power dynamic and the violence enshrined in neoliberalism and its ideological cognates, securitisation, the necessity to protect from the terrorist Muslim Other, and hetero-/homo-normativisation. Such was the need in 2005, following the Second Intifada and the donors’ need to ‘reform’ Palestinian security section (Dana, 2014), to propagate ‘the new Palestinian man’ with millions of US dollars which, according to its pundits, enabled the structural analytic of a ‘gender blurring’ agenda in the West Bank where women, too, can join the mission of fighting ‘terrorism’. (Daraghmeh and Laub, 2014). This is the terrorism that Gaza has now come to represent due to its containment of the Muslim/monster Other whose elimination is encouraged and called upon in Israeli public discourse. Thus, the construction of Gaza comes as the homophobic space whilst the West Bank or Ramallah in particular, with its US-trained security guards, is becoming perceived as the more open, ‘gay friendly’ space (Chang, 2016). This issue was raised in alQaws’s recent interactions with some international donors, who expressed interest in knowing more about what they called it ‘the new scene of gay friendly cafés in Ramallah’, and hinting that they had heard Ramallah was becoming similar to the gay haven of Tel Aviv. In doing so, the colonial regime comes to sustain itself through a logic of divide et impera (divide and rule) by creating more categories, divisions, and barriers that ought to be internalised in order to act as if the colonial regime is non-existent. Hence, what remains is the acting out of these fantasies (i.e., liberal Ramallah/Backward Gaza) where an image of Europe could be conceived whilst disavowing the failure to which these fantasies are bound. In fact, these fantasies are part and parcel of a larger hierarchising structure that is embedded in the image of the Palestinian homosexual and the extent of homophobia/backward space to which it is relegated. Thus, those coming from the 1948 territories (Palestinians living in Israel) come first, followed by those in liberal Ramallah, who are then followed by the rest of the West Bank, and finally, at the bottom of the ladder, comes Gaza. Pinkwashing as a colonial tactic contributed to the consolidation of such an image and its hierarchising effect.

The Pinkwashing Logic

When one approaches the dynamics inherent to the image of the homosexual in Palestine, it is impossible to ignore the link between Zionism and Pinkwashing. It is necessary to shed light on how Zionist politics influence both the analysis and the campaign of Pinkwashing. This campaign is one that uses ostensibly ‘progressive’ policies around gay tolerance to hide and distract from practices of colonialism. In this framing, we understand Pinkwashing as ‘a tactic of Zionism and an influential discourse of sexuality that has emerged within it’ (Schotten and Maikey, 2012). Therefore, anti-Pinkwashing works as an analysis and practice that ‘continues to uncover and makes visible the racial, ethnic, and sexual violence that informs Zionist ideology’ (Schotten and Maikey, 2012). In order to further expose the connection between Pinkwashing and Zionism, it is crucial to deconstruct the main logics and notions behind this campaign that was relentlessly marketed as a ‘Gay Rights Campaign’. To phrase it slightly differently, alQaws is interested in exploring what makes this Pinkwashing project a successful campaign that is appealing to queer people around the world, or what makes Zionism appealing to queers around the world.

Firstly, Pinkwashing is an ontologically racist and colonial project that does not simply emphasise how Israel is a fun, fabulous, open, modern — thus democratic and liberal — state, but is mainly based on dehumanising Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims by presenting them as homophobic, backward, and barbaric. In the Pinkwashing narrative, homophobia and intolerance toward non-conforming sexual and gender expressions, identities, and behaviours, is a disease rooted in society while tolerance is inherent to Israel as a liberal modern project. Such is the orientalist logic where the other is reduced to a set of realities and values that fit the opposite side of the binary (progressive/backward). It is a familiar Zionist tactic that reframes the relationship between Israel and Palestine from “coloniser-colonised” to one that distinguishes between those who are “modern and open”, and those who are presented as “backward and homophobic”. Thus, it simplifies and anaesthetises the fundamental violence on the basis of which colonialism thrives.

Secondly, Pinkwashing’s promotion of a modern/backward binary shows how it is premised on a notion of progress where the other is always-already dehumanised in the definition of the “modern and progressive” self. But, Pinkwashing is also framed in a way that speaks to those who have assimilated and internalised Islamophobic, racist, and anti-Arab messages into their vision of “progressiveness” and “modernity” as it is reflected in the liberal white gay project in the last two decades. In this sense, engaging with Pinkwashing is not only promoting a racist narrative about Palestinians, but more disturbingly its popularity of Pinkwashing among gay groups may lead us to assume that these notions (i.e., racism and Islamophobia) exist in our own communities. In our opinion, this says more about the political choices of queer communities around the globe, than about the clear colonial interest reflected in Pinkwashing, and maybe suggests an intersectional understanding of countering this in our communities.

Thirdly, Pinkwashing follows a gay rights approach which isolates some queer identities from others and conceals the structural inequalities that make certain (Jewish, Israeli) bodies and identities “acceptable” and others (Palestinian, Arab) not. In other words, Pinkwashing is based on Western gay organising frameworks and notions and in this sense, it is creating a common language and a common cause with other gay (middle-class, white) individuals and communities. Pinkwashing relies heavily on the logic of “gay rights” as it is commonly understood and practiced by these communities — a single-issue politics based on one’s sexual identity to the exclusion of other interconnected injustices based on race, ethnicity, class, gender, and other difference. The reliance on the gay rights frame of analysis allows Israel to promote and publicise itself as gay-friendly, concealing its settler-colonial premise which is based on intense forms of sexual regulation that are both gendered and racialised.5

Israeli LGBT Groups “Saving” Palestinian Queers

Since its inception in 2005, the “Re-branding Israel” campaign — with its focus on gay rights — included partnerships with LGBT Israeli groups, who were and still are directly complicit with this new state-funded project.29 Together with government-led bodies, Israeli LGBT groups promote gay tourism to Tel Aviv, advocate for Israel as the world LGBT ambassador, and present the IDF as a tolerant army for gay Israelis (‘serving with pride’). Thus, the Pinkwashing campaign is seen and considered by Israeli LGBT leaders and groups as the ultimate sign of state recognition, and we, in alQaws, continue to argue that Pinkwashing could not thrive without this unconditional support, and crucial role of the Israeli LGBT community.

Besides their direct involvement in promoting Pinkwashing, both globally and locally, LGBT Israeli leaders and groups are actively part of the production of the racist discourse about Palestinians in general, and LGBT Palestinians in particular. The main aspects of this discourse are: 1) the need to save Palestinian LGBTQs from their own homophobic families and society; 2) the exclusion of the broader context of settler colonialism vis-à-vis LGBT issues; 3) the denial of agency: erasure of the Palestinian queer movement (IGY, https://igy.org.il/en/).

Once again, it is possible to trace how Israeli Pinkwashing ideology functions through the presentation of Palestinian society as either “too homophobic” or “not active enough”, echoing Žižek’s (1995, 11) famous understanding of ‘too much of this’, ‘not enough of that’. Pinkwashing also takes the form of the Israeli government’s initiatives to promote gay tourism. This programme stems directly from Israeli homonationalism and LGBT Israelis’ commitment to define and promote Israel in relation to its gay parties and beaches and its locals who are welcoming foreigners in (e.g., GAY TLV Guide, http://www.gaytlvguide.com/). Such acts of welcoming others in are another means of naturalising the settler-colonial regime through Israeli queer desires and bodies expressing ownership of and locality to indigenous land and hence entitlement to invite tourists in. These ideals of queer tourism are also a significant source of income for Israel. In this case, Pinkwashing represents the underlying logic of neoliberalism in the guise of “democracy” and “gay rights”.6 It allows the generation of economic profit through such universal ideals of “gay tourism”, thus reproducing the colonial system in its abuse of indigenous resources.

The Impact of Pinkwashing on Palestinian Queers: Internalising the Image

Challenging the premise of Pinkwashing entails an exploration of its impact on and implications for LGBT Palestinians. AlQaws identifies two main notions that are assimilated by Palestinian LGBT individuals and communities due to the Pinkwashing campaign.

Firstly, the coloniser standards and fantasies about gay rights, homophobia, and racism are internalised in Palestinian LGBTQ communities. As a form of colonisation, Pinkwashing promotes the false idea that the Palestinian LGBTQ individuals and communities have no agency or place inside their own societies. This creates a detrimental and toxic colonial relationship where the colonised comes to perceive the colonisers’ presence as necessary for providing that which fulfils our fantasies.

Secondly, the main notions that describe the personal lives and experiences of LGBT Palestinians are victimhood and pain. In the attempt to strengthen Pinkwashing and dehumanise Palestinians, Palestinian queer bodies, personal stories, challenges, and pain have been used constantly as “proof” of our society’s “not enough progress”. In this regard, the main accomplishment is to make queer Palestinians victims of their own families and communities, triggering in them a desire or a dream to flee homophobic Palestine and reach the coloniser’s sandy beaches. According to this logic, the society and families of Palestinian queers are the main cause of their problems, and their existences as queers relies on their ability to hate their own support system. This is yet another way of isolating sexual and gender violence from the broader context of colonised Palestine. As their problems are reduced to sexual orientations, LGBT Palestinians are left with the option of being victims and/or hating their families; hence, their only solution is to look towards the colonisers for safety. This in turn creates the victim-saviour dynamic which in recent years has been at the centre of representations of the relationship between Palestinians and Israeli queers. This saviour/victim dynamic glosses over the fact that Palestinians, whether queer or not, cannot cross over to reach what is presumed to be their “safe-haven Israel”. This is not only due to the concrete presence of the barriers, including the apartheid wall, that Israel installs to hinder Palestinian daily mobility but also effectively due to the Israeli legal system which is, designed to deny Palestinians’ sheer existence. Furthermore, it is fundamental to stress that fetishising Palestinian queer bodies and pain means creating this hierarchy between different bodies in Palestine.

On the one hand, there are the bodies that Israelis do not care to kill and erase — as it happens in Gaza — and there are those bodies, the queer bodies, which should be saved. The only Palestinian who is worth saving, therefore, is the one that falls within exotic Israeli fantasies about who the Palestinian queer is.

Dismantling the Image

The dominant social and political construction of the image of the Palestinian homosexual is directly impacted by the continuous exploitation of Palestinian queers’ bodies and sexualities, to fulfil the goals of the coloniser (i.e. blackmailing queers to become collaborators, the suggestion that queer Palestinians are victims waiting for an Israeli saviour, promoting a false narrative about Palestinian society’s homophobia, etc.). Furthermore, in recent years, foreign governments and some gay international organisations have started to express clear interest in meetings or encounters with alQaws activists as a way to challenge the PA and/or civil society organisations to “respect” gay rights. This new dynamic, which is affected by the growing role of foreign governments and funding in Palestine, is further enforcing the notion of homosexuality as a Western issue in the eyes of Palestinian society. Furthermore, this dynamic entails a disturbing subtext that any “progress” in making Palestine more “tolerant” to gay rights and especially amongst authorities, is a sign that the project of building the Palestinian state fits the ultimate modernity standards of “gay tolerance”. More concretely, by moving forward with this project, foreign governments will not only gain greater legitimacy through their intervention in the state-building process in Palestine, but will also frame the PA and Palestine as a new player in the modern world. It goes without saying that this dynamic is taking place in a vacuum, as if Palestine is not colonised. AlQaws saw a crucial challenge to address and disrupt this discourse, by developing a locally informed and holistic analysis regarding sexuality and homosexuality in Palestine. Sexual and bodily freedom cannot be separated from the fight against Israeli colonialism. Thus comes the need for a movement that understands and engages with its political reality.

However, there is a strong tendency within Palestinian society to prioritise struggles and a hierarchy of liberation; putting the Palestinian national struggle at the top of the list while other struggles (e.g. women’s rights, gender and sexuality rights, and minority rights) come last. Hence, besides being seen as Israelising collaborators or Westernising intruders, the mere fact of talking of the intersectionality or hierarchy of struggles is seen as a diversion from the main cause, or as another force to fragment an already fragmented society. Therefore, the goal of dismantling this image, within Palestinian society and more importantly within LGBTQ communities, will remain a complex political project. AlQaws’s leadership has integrated this project and analysis in their work by addressing four different layers: we explore these four layers in the following sections of the chapter.

Decolonising Palestinian Identity within the Palestinian Queer Community

AlQaws works with a large group of Palestinian queers across historical Palestine to enlarge our base of grassroots political activists through different platforms and groups. In these groups, civil society organisations, student groups, and LGBTQ groups, alQaws works on building (from our own experiences) intersectional analyses of the powers of oppression at hand, from colonialism to patriarchy and capitalism. AlQaws concentrates on challenging the Pinkwashing discourse that many Palestinian queers have internalised, by transforming our image of ourselves from one of victimhood in our homophobic societies, and distance from our families and communities, to one of an active battle for justice aimed at rebuilding these burnt bridges, and shaping the society in which we desire to live. For instance, in alQaws youth groups, we work collectively on understanding the links between sexual oppression and colonialism, and how our bodies, desires and sexualities have been used by Israel. Furthermore, in these groups we are committed to exploring both how homophobia and sexual oppression are constructed in Palestinian society, as well as to relating to the strategies of resilience used by individuals and groups to express their sexualities in such a complex context.

Imagining a Decolonised Palestine

Decolonising our sexualities means directly resisting the policies of fragmentation and division of Palestinians, as the main colonial/Zionist strategies used systematically since 1948. The main goal of this strategy is to continue to divide and rule Palestinians into sub-social religious groups: Christians, Druze, Muslims, Bedouin, Palestinians of Jerusalem, Arab Israelis, West Bankers, Gazans, etc. Through this, Israel aims to prove that Palestinians did not exist before 1948, and reifies the old Zionist logic of “a land without a people for a people without a land”, for if there are people on this land, they are nothing but “grazing nomads” who will always fail to have a sense of collective identity and history.

Being one of the few groups working on both sides of the ‘Green Line’ that divides Israel from the ‘OPTs’,7 alQaws was always aware of how much these divisions were reproduced in LGBTQ spaces, too often creating a specific hierarchy of power relations that is familiar to wider society. Commitment to building LGBTQ communities across Palestine means that a crucial aspect of queer organising should be tackling this issue in a deep and constant way. In alQaws’s spaces, activists from different parts of Palestine, who never met before, were meeting and working together for the first time. National meetings of alQaws, which take place in the West Bank, are sometimes the first opportunity for queers from Ramallah and Haifa to meet, offering a space in which their internalised attitudes about each other may be challenged and deconstructed. It is not a one-off task, but an ongoing process that we address and challenge through our national strategies and local leadership initiatives. While we address these differences in our local work, this approach offers a glimpse to the undivided and decolonised Palestinian society that our work contributes to achieving. Holding this approach and implementing it through various levels of our organisation challenges the very existence of Zionism.

Refusal to Normalise with Israeli LGBTQ Groups

Based on alQaws’s experience, which started as part of an Israeli Zionist organisation and the understanding of it as part of a broader colonial experience, alQaws refuses, as a principle, to work with any group, including Israeli LGBT groups and other civil society organisations and groups, that do not have a clear political stance that confronts and challenges Israeli settler colonialism, Zionism, and Jewish supremacy. AlQaws’s community will not engage in any action, project, or partnership that normalises the Zionist colonial entity and the colonised-coloniser relationship as disguised by an agenda for “social justice” and “gay rights”.8

Challenging the Hegemony of Western LGBT Organising

The decolonisation of sexualities within alQaws and the queer Palestinian movement cannot happen without addressing the global politics related to gay rights. AlQaws works on building alliances with activists, groups and civil society organisations who are committed to sexual and gender diversity. In doing so, it shifts the attention from the negative image associated with homosexuality and focuses instead on a wider understanding of sexuality and gender. This creates a movement open to all, and not only LGBTQ-identifying people, focusing on feminist/queer analysis as a lens through which to understand the links between the different oppressions we face rather than trapping ourselves in single-identity, a-political activism that fails to confront the root causes of oppression.

Despite its structural limitations, alQaws’s work resists the hegemony of LGBTQ Western organising approaches and frameworks, and questions its relevance to different Global South-based queer groups. During the last decade, alQaws published different articles and texts deconstructing the four notions of coming out, homophobia, pride, and visibility (Maikey and Shamali, 2016). It showed how locally-informed strategies are possible, more inspiring and, most importantly, more relevant to our context. Some of the questions that helped alQaws activists in this process were: how can we frame our struggle as against homophobia when we do not publicly discuss sexuality? Are pride parades the ultimate celebration of freedom and visibility in a context where millions of Palestinians have no access to water, health care, mobility, work, etc.? How can individual visibility be understood in a family-based society? Is coming out, as understood and practiced in the West, a crucial step for healthy and open life? What are the means of a healthy and open life for LGBTQ people whose bodies, minds and reality is colonised?

Conclusion

Once sexuality and the image of the Palestinian queer are contextualised properly, unfolding the connections and intersections with the Zionist colonial regime, contrary to what most Western LGTBQ groups propose, sexuality comes to be understood not as an isolated component, or a single issue, of society. Rather, this manoeuvre of unveiling the fantasies that are projected on to the other, which combines academic and activist work in a constant dialogical relationship, shows how discourses of sexuality are deeply embedded in a structure of power whose ultimate goal is the oppression, if not the total elimination, of the other. Therefore, starting from this premise, alQaws tries to face and dismantle those racial sexual and gendered discourses that the Zionist colonial regime generates in order to enforce a process of subjugation of Palestinians. It is for this reason that alQaws believes in the need to engage in an open and honest discussion around the domains of truths that sexuality in general, and the image of the Palestinian homosexual in particular, are invested in and aim to propagate. If oppression is to be fought and a more just order of society is to emerge, the relationship with our bodies and how power hinges on them needs to be challenged in a radical, fundamental manner.

Bibliography

Butler, J., Frames of War (New York: Verso, 2010).

Chang, A., ‘Exploring Gay Palestine’, Passport, 2016, http://www.passportmagazine.com/exploring-gay-palestine/.

Dana, T., ‘The Beginning of the End of Palestinian Security Coordination with Israel?’ Jadaliyaa, 2014, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/18379/the-beginning-of-the-end-of-palestinian-security-council.

Daraghmeh, M. and Laub, K., ‘Palestinian Presidential Guard Unveils its First Female Fighters − Headscarved Commandos Taking New Ground’, The Independent, 2014, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/palestinian-presidential-guard-unveils-its-first-female-fighters-headscarved-commandos-taking-new-ground-9244604.html.

Gross, A. ‘Challenges to Compulsory Heterosexuality: Recognition and Non-Recognition of Same-Sex Couples in Israeli Law’, in Wintermute, R. and Andenaes, M. (eds), Legal Recognition of Same-Sex Partnerships: A Study of National, European and International Law (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2001), pp. 391–414, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472562425.ch-020.

Le More, A., International Assistance to the Palestinians After Oslo: Political Guilt, Wasted Money (New York: Routledge, 2008), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203928332.

Maikey, H., ‘The History and Contemporary State of Palestinian Sexual Liberation Struggle’, in Lim, A. (ed.), The Case for Sanctions Against Israel (London and New York: Verso, 2012), pp. 121–30.

Maikey. H. and Shamali, S., ‘International Day Against Homophobia: Between the Western Experience and the Reality of Gay Communities’, 2016, http://www.alqaws.org/siteEn/print?id=26&type=1.

Massad, J., ‘Conceiving the Masculine: Gender and Palestinian Nationalism’, Middle East Journal, 49.3 (1995), 467–83.

Massad, J., Desiring Arabs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Mikdashi, M., ‘Gay Rights as Human Rights: Pinkwashing and Homonationalism’, Jadaliyya, 2015, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/24855/Gay-Rights-as-Human-Rights-Pinkwashing-Homonationalism.

Morgensen, S. L., Spaces Between Us: Queer Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Decolonisation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816656325.001.0001.

Parsons, N., The Politics of the Palestinian Authority: from Oslo to Alaqsa (London: Routledge, 2005), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203020951.

Schotten, H. and Maikey, H., ‘Queers Resisting Zionism: On Authority and Accountability Beyond Homonationalism’, Jadaliyya, 2012, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/27175/Queers-Resisting-Zionism-On-Authority-and-Accountability-Beyond-Homonationalism.

Smith, A., ‘American Studies without America: Native Feminisms and the Nation-State’, American Quarterly, 60.2 (2008), #312, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.0.0014.

Sullivan, N. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474472944.

Walzer, L., Between Sodom and Eden: A Gay Journey through Today’s Changing Israel (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

Žižek, S., Mapping Ideology (London: Verso, 1995).

Žižek, S., ‘Against Human Rights’, New Left Review, 34 (2005), 115–33.

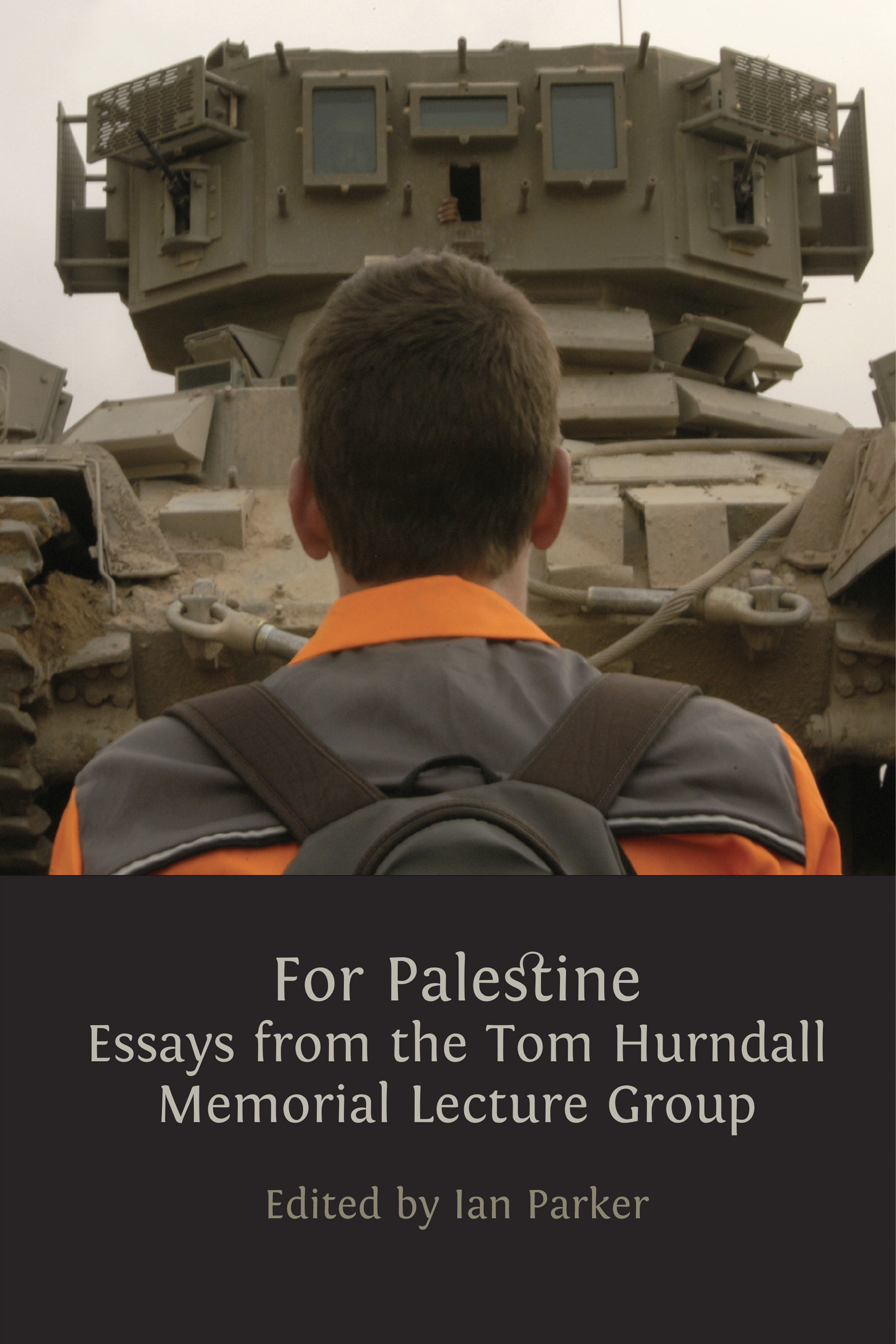

Fig. 10 Tom Hurndall, Shelled buildings in Rafah, April 2003. All rights reserved.

1 A version of this chapter first appeared in Bakshi, S., Jivraj, S. and Posocco, S. (eds), Decolonizing Sexualities: Transnational Perspectives, Critical Interventions (Oxford: Counterpress, 2016), pp. 125–40.

3 With reference to Joseph Massad’s critique of those identified as ‘the complicit’ gay internationalist Arabs, who are normalising and imposing Western gay identities that are not relevant to the Arab context, see F. Ewanje Epee and S. Maqliani-Belkacem (2013), ‘The Empire of Sexuality: An Interview with Joseph Massad’, Jadaliyya, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/10461/the-empire-of-sexuality_an-interview-with-joseph-m .

4 In reference to those excluded from the political community and reduced to ‘bare life’, see Žižek (2005).

5 This manifests in a few emblematic examples, such as the 2003 Citizenship and Entry Emergency Law that bars Palestinians married to Israelis from becoming citizens, ultra-Orthodox Jewish campaigns for gender segregation in public spaces, and the denial of Jewish-Jewish marriages inside Israel unless the couple is “converted” according to Orthodox principles.

6 The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) has defined normalisation specifically in a Palestinian and Arab context ‘as the participation in any project, initiative or activity, in Palestine or internationally, that aims (implicitly or explicitly) to bring together Palestinians (and/or Arabs) and Israelis (people or institutions) without placing as its goal resistance to and exposure of the Israeli occupation and all forms of discrimination and oppression against the Palestinian people.’ See PACBI, https://bdsmovement.net/pacbi.

7 Besides the fragmentation policies, it is important to mention how the separation of Palestinians is also achieved through ninety-nine fixed checkpoints (fifty-nine internal checkpoints and forty inspection points before entering Israel); more than 500 physical obstructions (iron gates, concrete blocks, and more) blocking access roads to main traffic arteries in the West Bank; sixty-five kilometres of closed roads inside the West Bank open to Israelis only; and the 430 miles of apartheid wall.

8 The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) has defined normalisation specifically in a Palestinian and Arab context “as the participation in any project, initiative or activity, in Palestine or internationally, that aims (implicitly or explicitly) to bring together Palestinians (and/or Arabs) and Israelis (people or institutions) without placing as its goal resistance to and exposure of the Israeli occupation and all forms of discrimination and oppression against the Palestinian people”. See PACBI, https://bdsmovement.net/pacbi.