8. Archaeology, Architecture and the Politics of Verticality1

© 2023 Eyal Weizman, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0345.09

Since the 1967 war, when Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, a colossal project of strategic, territorial and architectural planning has lain at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The landscape and the built environment became the arena of conflict. Jewish settlements — state-sponsored islands of “territorial and personal democracy”, manifestations of the Zionist pioneering ethos — were placed on hilltops overlooking the dense and rapidly changing fabric of the Palestinian cities and villages. “First” and “Third” Worlds spread out in a fragmented patchwork: a territorial ecosystem of externally alienated, internally homogenised enclaves located next to, within, above or below each other. The border ceased to be a single continuous line and broke up into a series of separate makeshift boundaries, internal checkpoints and security apparatuses. The total fragmentation of the terrain on plan demanded for the design of continuity across the territorial section. Israeli roads and infrastructure thereafter connected settlements while spanning over Palestinian lands or diving underneath them. Along these same lines, Ariel Sharon proposed a Palestinian State on a few estranged territorial enclaves ‘connected by tunnels and bridges’, while further insisting that Israel would retain sovereignty on the water aquifers underneath Palestinian areas and on the airspace and electromagnetic fields above them.

Indeed, a new way of imagining territory was developed for the West Bank. The region was no longer seen as a two-dimensional surface of a single territory, but as a large three-dimensional volume, containing a layered series of ethnic, political and strategic territories. Separate security corridors, infrastructure, and underground resources were thus woven into an Escher-like space that struggled to multiply a single territorial reality.

What was first described by Meron Benvenisti as crashing ‘three-dimensional space into six dimensions — three Jewish and three Arab’ became the complete physical partitioning of the West Bank into two separate but overlapping national geographies in volume across territorial cross sections, rather than on a planar surface.

The process that split a single territory into a series of territories is the “Politics of Verticality”. Beginning as a set of ideas, policies, projects and regulations proposed by Israeli state-technocrats, generals, archaeologists, planners and road engineers since the beginning of the occupation of the West Bank, it has by now become the common practise of exercising territorial control as well as the dimension within which territorial solutions are sought.

Archaeology

When the Zionists first arrived in Palestine late in the nineteenth century, the land they found was strangely unfamiliar; different from the one they consumed in texts photographs and etchings. Reaching the map co-ordinates of the site did not bring them there. The search had to continue and thus split in opposite directions along the vertical axis: above, in a metaphysical sense, and below, as archaeological excavations.

That the ground was further inhabited by the Arabs and marked with the traces of their lives complicated things even further. The existing terrain started to be seen as in a protective wrap, under which the historical longed-for landscape was hidden. Archaeology attempted to peel this visible layer and expose the historical landscape concealed underneath. Only a few metres below the surface, a palimpsest made of five-thousand-year-old debris, traces of cultures and narratives of wars and destruction was arranged chronologically in layers compressed with stone and by soil.

Biblical Archaeology as a scientific discipline was initiated by William Foxwell Albright’s excavation works in Palestine in the early 1920s. Archaeology was seen as a sub-discipline in biblical research, a tool for the provision of objective external evidence that will prove the originality of ancient traditions. Biblical Archaeology attempted to match traces of Bronze Age material ruins with biblical narratives.

This legacy suited modern Israel well. In its early days, the state attempted to fashion itself as the successor of ancient Israel, and to construct a new national identity rooted in the depths of the ground. Material traces took on immense importance, as an alibi for the Jewish return. But differing from the American branch of biblical archaeology, the Israeli one was secular, working to create a secular ‘fundamentalism’ that saw the Bible both as a document in need of verification and as a source that can be relied upon as evidence.

If the land to be “inherited” was indeed located under the surface, then the whole subterranean volume became a national monument, from which an ancient civilisation could be politically resurrected to testify for the right of present-day Israel.

At the centre of this activity, quickly its very symbol, was Yig’al Yadin, the former military chief of staff turned archaeologist. Seeking to supply Israeli society with historical parallels to the struggles of Zionism, he focused his digging on the periods of the biblical occupation and settlement of the Israelites in Canaan, on ancient wars and on monumental building and fortification works carried out by the kings of Israel. In his methodology, weapons were studied more than any other ingredients of life.

Even the excavation works were conceived as inherently military: sites were located after an observation from detailed maps and aerial photographs, excavation camps were regimented by military discipline, and transportation was relying on military vehicles and helicopters.

After the Six-Day War, archaeological sites and data became more easily available. The mountains of the West Bank are where most sites of biblical significance are located. Most organised archives of archaeology and antiquity: the East Jerusalem-based Rockefeller Museum, the American school for Oriental Research, the French École Biblique with their collections and libraries came under Israeli control.

The settlement project of the West Bank was based on an attempt to anchor new claims to ancient ones. Some settlements were constructed adjacent to or over sites suspected of having a Hebrew past. Making the historical context explicit allowed for the re-organisation of the surface, creating an apparent continuum of Jewish inhabitation. Settlements even recycled history by adopting the names of biblical sites, making public claim to genealogical roots. The visible landscape and the buried one were describing two different maps in slippage over each other.

Archaeological Architecture

The 1967 war marks a stylistic transition in Israeli architecture. The wave of nationalistic sentiment that followed the “liberation” and unification of Jerusalem, together with the surveying of abundant archaeological sites in the West Bank were incorporated overnight into a new mode of architectural production. The practice of archaeology was extruded into a new building style.

In the 1950s and 1960s state-sponsored housing developments reflected the socialist ethos in the austere, white-block model of European Modernism. But as Zvi Efrat claims, when the Six-Day War wound-up, national taste was radically transformed. The focus of architectural inspiration shifted from European Brutalism to Jerusalemite Orientalism. The “organic” structures of the oriental old city of Jerusalem were reproduced in endless light and material studies, in charcoal drawings and in archaeology albums.

Then, without the rhetorical manifestos that announce the immanent emergence of a new avant-garde, new neighbourhoods, especially in and around Jerusalem, started boasting arches and domes (most often reproduced in prefabricated concrete) colonnades and courtyards, within “old city-like” clusters of buildings clad with a veneer of slated Jerusalem stone.

Concrete skeletons were wrapped with layers embodying series of references varying from the biblical to the oriental, crusader Arab and even mandatory style, used separately or all together. It was this architectural postmodernism “avant la lettre”, that reflected the confusion of a newly inaugurated national-religious identity.

The Vertical Schizophrenia of the Temple Mount

Subterranean Jerusalem is at least as complex as its terrain. Nowhere is this truer than of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. The ascent of the then Prime Minister Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount in 2000 and the bloodshed during the Intifada that followed were not unique. The Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif has often been the focal point of the conflict.

The Haram al-Sharif compound is located over a filled-in, flattened-out summit on which the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock are located. The mount is supported by retaining walls, one of which is the Western Wall, whose southern edge is known as the Wailing Wall. The Western Wall is part of the outermost wall of what used to define the edge of the Second Temple compound.

Most archaeologists believe that the Wailing Wall was a retaining wall supporting the earth on which the Second Temple stood at roughly the same latitude as today’s mosques. But the Israeli delegation at Camp David negotiations argued that the Wailing Wall was built originally as a free-standing wall, behind which (and not over which) stood the Second Temple. What follows is that the remains of the Temple are to be found underneath the mosques and that what separated the most holy Jewish site from the Muslim mosques is a vertical distance of a mere ten metres. That vertical separation into the above and below was the source of the debate that followed.

Since East Jerusalem was occupied in 1967, the Muslim religious authority (the Wakf) has charged that Israel is trying to undermine the compound foundations in order to topple the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and to clear the way for the establishment of the Third Jewish Temple. Jewish groups contend that the Wakf’s extensive work in the subterranean chambers under the mosques is designed to rid the mountain of ancient Israelites remnants, and that the large-scale earth works conducted in the process destabilise the mountain and have generated cracks in the retaining wall of the mount.

On 24 September 1996, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, wanting to demonstrate his control of all layers of the city, ordered the opening of a subterranean archaeological tunnel running along the foundation of the Western Wall, alongside the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount compound. The opening of the ‘Western Wall Tunnel’ was wrongly perceived as an attempt at subterranean sabotage. But Palestinian sentiments were fuelled by memories of a similar event that occurred in December 1991 which saw another excavated tunnel under the Harram collapsing and opening a big hole in the floor of the Mosque of Atman ben-Afan.

Israel’s chief negotiator at Camp David, Gilead Sher, told how, during the failed summit on 17 July 2000 in the presence of the whole Israeli delegation, Barak declared: ‘We shall stand united in front of the whole world, if it becomes apparent that an agreement wasn’t reached over the issue of our sovereignty over the First and Second Temples. It is the Archemedic point of our universe, the anchor of the Zionist effort […] we are at the moment of truth.’

The two delegations laid claim to the same plot of land. Neither side was willing to give it up. In attempts to reconcile the irreconcilable, intense spatial contortions were drawn on variously scaled plans and sections of the compound.

The most original bridging proposal at Camp David came from the then US President Bill Clinton. After the inevitable crisis, Clinton dictated his proposal to the negotiating parties. It was a daring and radical manifestation of the region’s vertical schizophrenia, according to which the border between Arab East and Jewish West Jerusalem would, at the most contested point on earth, flip from the horizontal to the vertical — giving the Palestinians sovereignty on top of the Mount while maintaining Israeli sovereignty below the surface, over the Wailing Wall and the airspace above it. The horizontal border would have passed underneath the paving of the Haram al-Sharif, so that a few centimetres under the worshippers in the Mosque of al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock, the Israeli underground would be dug up for remnants of the ancient Temple, believed to be ‘in the depth of the mount’.

In order to allow free access to the Muslim compound, now isolated in a three-dimensional sovereign wrap by Israel, Barak, embracing the proposal, suggested ‘a bridge or a tunnel, through which whoever wants to pray in al-Aqsa could access the compound’.

But the Palestinians, long suspicious of Israel’s presence under their mosques, have flatly rejected the plan. They claimed (partly bemused) that ‘Haram al-Sharif […] must be handed over to the Palestinians — over, under and to the sides, geographically and topographically.’

Regarding the truth about the remnants of the Temple ‘in the depth of the mount’, there are few and varied scholarly studies and opinions. But Charles Warren, a captain in the Royal Engineers. who was in 1876 one of the first archaeologists to excavate the tunnels and subterranean chambers under the Haram/Temple Mount, recorded no conclusive ruins of the Temple, but a substance of completely different nature:

The passage is four feet wide, with smooth sides, and the sewage was from five to six feet deep, so that if we had fallen in there was no chance of our escaping with our lives. I, however, determined to trace out this passage, and for this purpose got a few old planks and made a perilous voyage on the sewage to a distance of 12 feet… The sewage was not water, and not mud; it was just in such a state that a door would not float, but yet if left for a minute or two would not sink very deep…

If that Indiana Jones-type description was correct, what Clinton and the negotiating teams hadn’t realised was that the Temple Mount sat atop a network of ancient ducts and cisterns filled with generations of Jerusalem’s sewage.

Storrs’ Stare of Medusa

Perhaps Jerusalem’s best-known by-law is the one enacted in 1918 by the first British military governor of the city, Sir Ronald Storrs, soon after he started his term in office. The first urban by-law of the British mandate in Palestine required square, dressed natural stone — Jerusalem stone — for the façades and visible external walls of all new buildings constructed in the city.

This historicist by-law, later confirmed by the Jerusalem District Building and Town Planning Commission in 1936, determined the image of Jerusalem more than any other law, by-law or programme devised by the authorities over the subsequent eighty years.

Storrs was the officer in commanded of the battle for Jerusalem in General Allenby’s army. So deep was his admiration for Jerusalem, fuelled by romantic and religious zeal, that whilst fighting the Ottoman army, and subsequently taking Jerusalem off their hands, he issued an order according to which during the battle none of Jerusalem’s buildings must be destroyed. Storrs’ aim was to protect the holy city as he imagined it, and repel all threats to its ‘hallowed and immemorial tradition’. During the time of his rather peaceful reign, the city’s growing poverty on the one hand and its rapid expansion on the other threatened to overrun its image much more than the potential destruction of war.

Whilst enacting the by-law demanding the stone finish, Storrs sought to regulate the city’s appearance, to resist time and change, and could not have realised that whilst dressing Jerusalem in a single architectural uniform, he in effect created the conditions for its excessive expansion, self-replication, and sprawl as a single entity.

In the context of contemporary Jerusalem, the stone does more than just fulfil an aesthetic agenda of preservation — it defines visually the geographic limits of Jerusalem and more importantly — since Jerusalem is a holy city — marks the extent of its holiness.

The idea of Jerusalem as the City of God, and thus as a holy place, is entrenched in Judeo-Christian belief. In their Diaspora, Jews started yearning for a city that became in their imagination increasingly disassociated from the reality of the physical site. Jerusalem itself became holy rather than a place containing holy sites.

If the city itself is holy, then, in the contemporary context, the totality of its buildings, roads, vegetation, infrastructure, neighbourhoods, parking garages, shops and workshops is holy. A special holy status is reserved for the ground. And if the ground is holy, its relocation as stones from the horizontal (earth) to the vertical (walls), from the quarries to the façades of buildings, transfers holiness further. As Jerusalem’s ground paving of stone climbs up to wrap its façades, the new “ground topography” of holiness is extended.

When the city itself is holy, and when its boundaries are constantly being negotiated, redefined, and redrawn, holiness becomes a planning issue. Shortly after the occupation of the eastern Arab part of the city, the municipal boundaries of Israeli Jerusalem were expanded to include the Palestinian populated eastern parts as well as large empty areas around and far beyond them (and the municipal area of Jerusalem grew from 33.5 square kilometres in 1952 to 108 square kilometres in 1967). These “new territories” annexed to the city, designed as “reserves” for future Israeli expansions, were required to comply with Storrs’ by-law — their buildings to be clad in stone, preserving the traditional and familiar Jerusalem look — turning suburban neighbourhoods, placed on remote and historically insignificant sites far from the historical centre, to “Jerusalem”, and participating thus in the city’s sacredness. The holy status, felt psychologically and defined visually in the stone, places every remote and newly built suburb well within the boundaries of ‘the eternally unified capital of the Jewish people’.

Like the Gaze of Medusa, Storrs’ law petrified new constructions into stone in new neighbourhoods, suburbs and settlements: shopping malls, kindergartens, community centres, synagogues, office buildings, electrical relay station, sports halls and housing were covered in stone, and as far as the stone façades were extended, the holiness of Jerusalem sprawled.

Jerusalem did not grow and develop naturally. The expansions of Jewish neighbourhoods after the 1967 war, into Arab lands to the north and the east, were designed to ensure the impossibility of a geographical re-division of the city into two distinct parts, Arab-Palestinian and Jewish. The fact that the new hilltop neighbourhoods were located according to this political and strategic logic, rather than according to urban logic, has created a disaster on a colossal scale. The new neighbourhoods demanded an ever-increasing paving of roads and an expensive network of infrastructure while their placement in remote locations left large, empty areas between them and the historical city centre.

The new suburban hilltop neighbourhoods built beyond the 1967 lines, on areas annexed to the city, are located farthest away from the centre and describe the outermost circle. Nonetheless, the stone regulations that apply there are as strict as those demanded for in the city centre. The symbolic centre has relocated to the periphery, leaving vast gaps in the urban fabric in-between. The relocation of the centre to the periphery was not only a symbolic move — the city inhabitants themselves, wary of the congested, multicultural and disputed city centre, opted for the ethnic, cultural and social homogeneity of the periphery. Approximately 200,000 Jewish people migrated within Jerusalem between 1990 and 1997, more than a half of them from the centre of the western city to the new periphery. These in-town migrants, seeking the aura of Jerusalem in its suburbs, have transplanted its holiness along with its stone.

The 1955 masterplan grants an important concession and incentive. Unlike other claddings, the stone, sometimes as thick as twenty-five centimetres, is allowed to project outside of the building envelope, thus occupying, on occasions where the building line corresponds with that of the street, public ground. The law acknowledges the fact that this cladding performs an important public function, and since public signs are meant to occupy public ground, the stone was allowed “to invade” the street. (In that respect, it is worth noting that architects building in Jerusalem found creative variations for the use of stone cladding, most notably Ram Karmi, then the architect of the Ministry of Housing, advocated the use of stone cladding vertically rather than horizontally — exposing the fact that the building is clad in stone and not built in it.)

The extension of the city’s “holiness” to the new suburbs was conceived as part of an Israeli attempt to generate widespread public acceptance of the newly annexed territories, otherwise viewed as a political and urban burden. Whatever is called Jerusalem, by name and by the use of stone, lies at the heart of the Israeli consensus that “Jerusalem shall not be re-divided”. The cladding of buildings in stone is an architectural ritual whose repetition attempts to fabricate a collective memory serving a nationalistic agenda.

Jerusalem, as a name, as an idea and as a city, has strong grips over the mind of its inhabitants. A city that was always perceived as an idea rather than a concrete, earthly reality has no boundaries besides those in the mind. The stone cladding functions thus to connect the transformed geographical reality of Jerusalem with the ephemeral idea of the heavenly city. This politically conscious use of geographical identity relies heavily on stone as a signifier to call forth the image of a mystic past. The public acceptance of the expansion of Jerusalem is made possible by the replication of its “character” and “feel”. The spectator is left incapable of drawing the boundary between the city and its idea, between its earthly geographical reality and a sense of sanctification and renewed holiness epitomised in the salvation of the ground.

Although originally conceived to protect and preserve an aesthetic status quo, Storrs’ stone by-law was extended by Israeli policy makers beyond the performance of mere aesthetic purposes. By visually defining the geographic limits of the city and marking the extent of its holiness, it has been made into a politically manipulative and colonising architectural device.

Terrain

More, then, than anything else, the Israeli-Palestinian terrain is defined by where and how one builds. The terrain dictates the nature, intensity and focal points of confrontation. On the other hand, the conflict manifests itself most clearly in the adaptation, construction and obliteration of landscape and built environment. Planning decisions are often made not according to criteria of economical sustainability, ecology or efficiency of services, but to serve strategic and national agendas.

The West Bank is a landscape of extreme topographical variation, ranging from four hundred and forty metres below sea level at the shores of the Dead Sea, to about one thousand metres in the high summits of Samaria. Settlements occupy the high ground, while Palestinian villages occupy the fertile valley in between. This topographical difference defines the relationship between Jewish and Palestinian settlements in terms of strategy, economy and ecology.

The politics of verticality is exemplified across the folded surface of the terrain — in which the mountainous region has influenced the forms the territorial conflict has produced.

Vertical Planning

Matityahu Drobles was appointed head of the Jewish Agency’s Land Settlement Division in 1978. Shortly after, he issued The Master Plan for the Development of Settlements in Judea and Samaria. In this master plan he urges the government to

[…] Conduct a race against time […] now [when peace with Egypt seemed imminent] is the most suitable time to start with wide and encompassing rush of settlements, mainly on the mountain ranges of Judea and Samaria… The thing must be done first and foremost by creating facts on the ground, therefore state land and uncultivated land must be taken immediately in order to settle the areas between the concentration of [Palestinian] population and around it… being cut apart by Jewish settlements, the minority [sic] population will find it hard to create unification and territorial continuity.

The Drobles master plan outlined possible locations for scores of new settlements. It aimed to achieve its political objectives through the re-organisation of space. Relying heavily on the topography, Drobles proposed new high-volume traffic arteries to connect the Israeli heartland to the West Bank and beyond. These roads would be stretched along the large west-draining valleys; for their security, new settlement blocks should be placed on the hilltops along the route. He also proposed settlements on the summits surrounding the large Palestinian cities, and around the roads connecting them to each other.

This strategic territorial arrangement has been brought into use during the Israeli Army’s invasion of Palestinian cities and villages. Some of the settlements assisted the IDF in different tasks, mainly as places for the army to organise, re-fuel and re-deploy.

The hilltops lent themselves easily to state seizure. In the absence of an ordered land registry in time of Jordanian rule, Israel was able to legally capture whatever land was not cultivated. Palestinian cultivated lands are found mainly in the valleys, where the agriculturally suitable alluvial soil erodes down from the limestone slopes of the West Bank highlands. The barren summits were left empty.

The Israeli government launched a large-scale project of topographical and land-use mapping. The terrain was charted and mathematised, slope gradients were calculated, the extent of un-cultivated land marked. The result, summed up in dry numbers, left about thirty-eight per cent of the West Bank under Israeli control, isolated in discontinuous islands around summits. That land was then made available for settlement.

Community Settlements

The “Community Settlement” is a new type of settlement developed in the early 1980s for the West Bank. It is in effect a closed members’ club, with a long admission process and a monitoring mechanism that regulates everything from religious observance to ideological rigour, even the form and outdoor use of homes. Settlements function as dormitory suburbs for small groups of Israelis who travel to work in the large Israeli cities. The hilltop environment, isolated, with wide views, and hard to reach, lent itself to the development of this newly conceived utopia.

In the formal processes, which base mountain settlements on topographical conditions, the laws of erosion had been absorbed into the practice of urban design. The mountain settlement is typified by a principle of concentric arrangement, with roads laid out in rings following the topographical lines around the summit.

The “ideal” arrangement for a small settlement is a circle. But in reality the particular layout of each depends on site morphology and the extent of available state land. Each is divided into equal, repetitive lots for small, private, red-roofed homes. The public functions are generally located within the innermost ring, on the higher ground.

The community settlements create cul-de-sac envelopes, closed off to their surroundings, promoting a mythic, communal coherence in a shared formal identity. It is a claustrophobic layout, expressing a social vision that facilitates the intimate management of the lives of the inhabitants.

Optical Urbanism

High ground offers three strategic assets: greater tactical strength, self-protection, and a wider view. This principle is as long as military history itself. The Crusaders’ castles, some built not far from the location of today’s settlements, operated through the reinforcement of strength already provided by nature. These series of mountaintop fortresses were military instruments for the territorial domination of the Latin kingdom.

The Jewish settlements in the West Bank are not very different. Not only places of residence, they create a large-scale network of “civilian fortification” which is part of the army’s regional plan of defence, generating tactical territorial surveillance. A simple act of domesticity, a single-family home shrouded in the cosmetic façade of red tiles and green lawns, conforms to the aims of territorial control.

But unlike the fortresses and military camps of previous periods, the settlements are sometimes without fortifications. Up until recently, only a few settlements agreed to be surrounded by walls or fences. They argued that they must form continuity with the holy landscape; that it is the Palestinians who need to be fenced in.

During the First Intifada many settlements were attacked, and debate returned over the effect of fences. Extremist settlers claimed that protection could be exercised solely through the power of vision, rendering the material protection of a fortified wall redundant and even obstructive.

Indeed, the form of the mountain settlements is constructed according to a geometric system that unites the effectiveness of sight with spatial order, producing “panoptic fortresses”, generating gazes to many different ends. Control — in the overlooking of Arab town and villages; strategy — in the overlooking of main traffic arteries; self-defence — in the overlooking of the immediate surroundings and approach roads. Settlements could be seen as urban optical devices for surveillance and the exercise of power.

In 1984 the Ministry of Housing published guidance for new construction in the mountain region, advising: ‘Turning openings in the direction of the view is usually identical with turning them in the direction of the slope … [the optimal view depends on] the positioning of the buildings and on the distances between them, on the density, the gradient of the slope and the vegetation’.

That principle applies most easily to the outer ring of homes. The inner rings are positioned in front of the gaps between the homes of the first ring. This arrangement of the homes around summits, outward looking, imposes on the dwellers axial visibility (and lateral invisibility), oriented in two directions: inward and outward.

Discussing the interior of each building, the guidance recommends the orientation of the sleeping rooms towards the inner public spaces and the living rooms towards the distant view. The inward-oriented gaze protects the soft cores of the settlements, the outward-oriented one surveys the landscape below. Vision dictated the discipline and mode of design on every level, even down to the precise positioning of windows: as if, following Paul Virilio, ‘the function of arms and the function of the eye were indefinitely identified as one and the same’.

Seeking safety in vision, Jewish settlements are intensely illuminated. At night, from a distance they are visible as brilliant white streaks of light. From within them, the artificial light shines so brightly as to confuse diurnal rhythms. This is in stark contrast to Palestinian cities: seeking their safety in invisibility, they employ blackouts as a routine of protection from aerial attacks.

In his verdict in support of the “legality” of settlement, Israeli High Court Justice Vitkon argued,

One does not have to be an expert in military and security affairs to understand that terrorist elements operate more easily in an area populated only by an indifferent population or one that supports the enemy, as opposed to an area in which there are persons who are likely to observe them and inform the authorities about any suspicious movement. Among them no refuge, assistance, or equipment will be provided to terrorists. The matter is simple, and details are unnecessary.

The settlers come to the high places for the “regeneration of the soul”. But in placing them across the landscape, the Israeli government is drafting its civilian population alongside the agencies of state power, to inspect and control the Palestinians. Knowingly or not, settlers’ eyes, seeking a completely different view, are being “hijacked” for strategic and geopolitical aims.

The Paradox of Double Vision

The journey into the mountains, seeking to re-establish the relation between terrain and sacred text, was a work of tracing the location of “biblical” sites, and constructing settlements adjacent to them. Settlers turned “topography” into “scenography”, forming an exegetical landscape with a mesh of scriptural signification that must be “read”, not just “viewed”.

For example, a settlement located near the Palestinian city of Nablus advertises itself thus:

Shilo spreads up the hills overlooking Tel Shilo, where over three thousand years ago the children of Israel gathered to erect the Tabernacle and to divide by lot the Land of Israel into tribal portions… this ancient spiritual centre has retained its power as the focus of modern day Shilo.

Rather than being a resource for agricultural or industrial cultivation, the landscape establishes the link with religious-national myths. The view of the landscape does not evoke solemn contemplation, but becomes an active staring, part of an ecstatic ritual: ‘it causes me excitement that I cannot even talk about in modesty’, says Menora Katzover, wife of a prominent settlers’ leader, about the view of the Shomron mountains.

Another sales brochure, published for member recruitment in Brooklyn and advertising the ultra-orthodox settlement of Emanuel, evokes the pastoral: ‘The city of Emanuel, situated 440 metres above sea level, has a magnificent view of the coastal plain and the Judean Mountains. The hilly landscape is dotted by green olive orchards and enjoys a pastoral calm.’

There is a paradox in this description. The very thing that renders the landscape “biblical” — traditional inhabitation, cultivation in terraces, olive orchards and stone buildings — is made by the Arabs whom the settlers come to replace. The people who cultivate the ‘green olive orchards’ and render the landscape biblical are themselves excluded from the panorama.

It is only when it comes to the roads that the brochure mentions Arabs, and that only by way of exclusion. ‘A motored system is being developed that will make it possible to travel quickly and safely to the Tel Aviv area and to Jerusalem on modern throughways, bypassing Arab towns’ (emphasis in the original). The gaze that can see a “pastoral, biblical landscape” will not register what it doesn’t want to see — the Palestinians.

State strategy established vision as a means of control, and uses the eyes of settlers for this purpose. The settlers celebrate the panorama as a sublime resource, but one that can be edited. The sight-lines from the settlements serve two contradictory agendas simultaneously.

The Emanuel brochure continues, ‘Indeed new Jewish life flourishes in these hills of the Shomron, and the nights are illuminated by lights of Jewish settlements on all sides. In the centre of all this wonderful bustling activity, Emanuel, a Torah city, is coming into existence.’

From a hilltop at night, a settler can lift his eyes to see only the blaze of other settlements, perched at a similar height atop the summits around. At night, settlers could avoid the sight of Arab towns and villages, and feel that they have truly arrived ‘as the people without land — to the land without people’. (This famous slogan is attributed to Israel Zangwill, one of the early Zionists who arrived to Palestine before the British mandate, and described the land to which Eastern European Zionism was headed as desolate and forsaken.)

Latitude thus becomes more than merely relative position on the folded surface of the terrain. It functions to establish literally parallel geographies of “First” and “Third” Worlds, inhabiting two distinct planes, in the startling and unprecedented proximity that only the vertical dimension of the mountains could provide.

Rather than the conclusive division between two nations across a boundary line, the organisation of the West Bank’s particular terrain has created multiple separations, provisional boundaries, which relate to each other through surveillance and control. This intensification of power could be achieved in this form only because of the particularity of the terrain.

The mountain settlements are the last gesture in the urbanisation of enclaves. They perfect the politics of separation, seclusion and control, placing them as the end-condition of contemporary urban and architectural formations such as “New Urbanism”, suburban enclave neighbourhoods or gated communities. The most ubiquitous of architectural typologies is exposed as terrifying within the topography of the West Bank.

The assassination of Palestinian militants within their cities was made possible by technological advances and the ability to achieve rapidly integrative systems. Beyond the hardware of the aerial platforms, it is the soft technological application of information and communications technology that allows for the synergetic integration of military equipment. This integration relies on the control of the airways and the electromagnetic spectrums, thus making essential the possession of total control of the airspace. With the presence and availability of this technology, acts of personal liquidation became subjected only to will.

If the potential of iron bombing to horrify the imagination has already been exhausted, this next step of warfare, in which armies could target individuals within a battlefield or civilians in precise urban warfare, when summary executions are carried out after short meetings between army generals and politicians working their way down “wanted” men lists, makes warfare an almost personal matter, and sets with it a new horizon of horror.

Bibliography

Boeri, S. ‘Border Syndrome’, in Franke, A., Weizman, E., Boeri, S. and Segal, R. (eds), Territories (Berlin: KW and Walther Keoing, 2003).

Etkes, D., ‘Settlement Watch’, Peace Now, 2003, https://peacenow.org.il/en//category/settlements

Graham, S., Urbicide, in Jenin, 2002, www.opendemocracy.net.

Halper, J., The Matrix of Control, https://icahd.org/get-the-facts/matrix-control.

Kemp, A., ‘Border space and national identity in Israel’, in: Yehuda Shenhav (ed.), Theory and Criticism, Space, Land, Home, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv (Jerusalem: The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2000), pp. 13–43

Lein, Y., ‘Behind the Barrier’, Jerusalem: B’Tselem, 2003, http://www.btselem.org/Download/2003_Behind_The_Barrier_Eng.doc.

Lein, Y. and Weizman, E., ‘Land Grab’, Jerusalem: B’Tselem, 2002, https://www.btselem.org/download/200205_land_grab_eng.pdf.

Ministry of Agriculture and the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, Masterplan for Jewish Settlements in the West Bank Through the Year 2010 and Masterplan for Settlement for Judea and Samaria, Development Plan for the Region for 1983–1986. Jerusalem: Ministry of Agriculture and the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, 1983.

Rotbard, S., ‘Tower and stockade’, in Segal, R. and Weizman, E. (eds), A Civilian Occupation, Tel Aviv and London (Tel Aviv and London: Babel Press and Verso Press, 2003), pp. 59–67.

Segal, R. and Weizman, E., ‘The Mountain’, in: Segal, R. and Weizman, E. (eds), A Civilian Occupation (Tel Aviv and London: Babel Press and Verso Press, 2003), pp. 39–58.

Sharon, A. with Chanoff, D., Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001).

Weizman, E., The Politics of Verticality, 2002, www.opendemocracy.net.

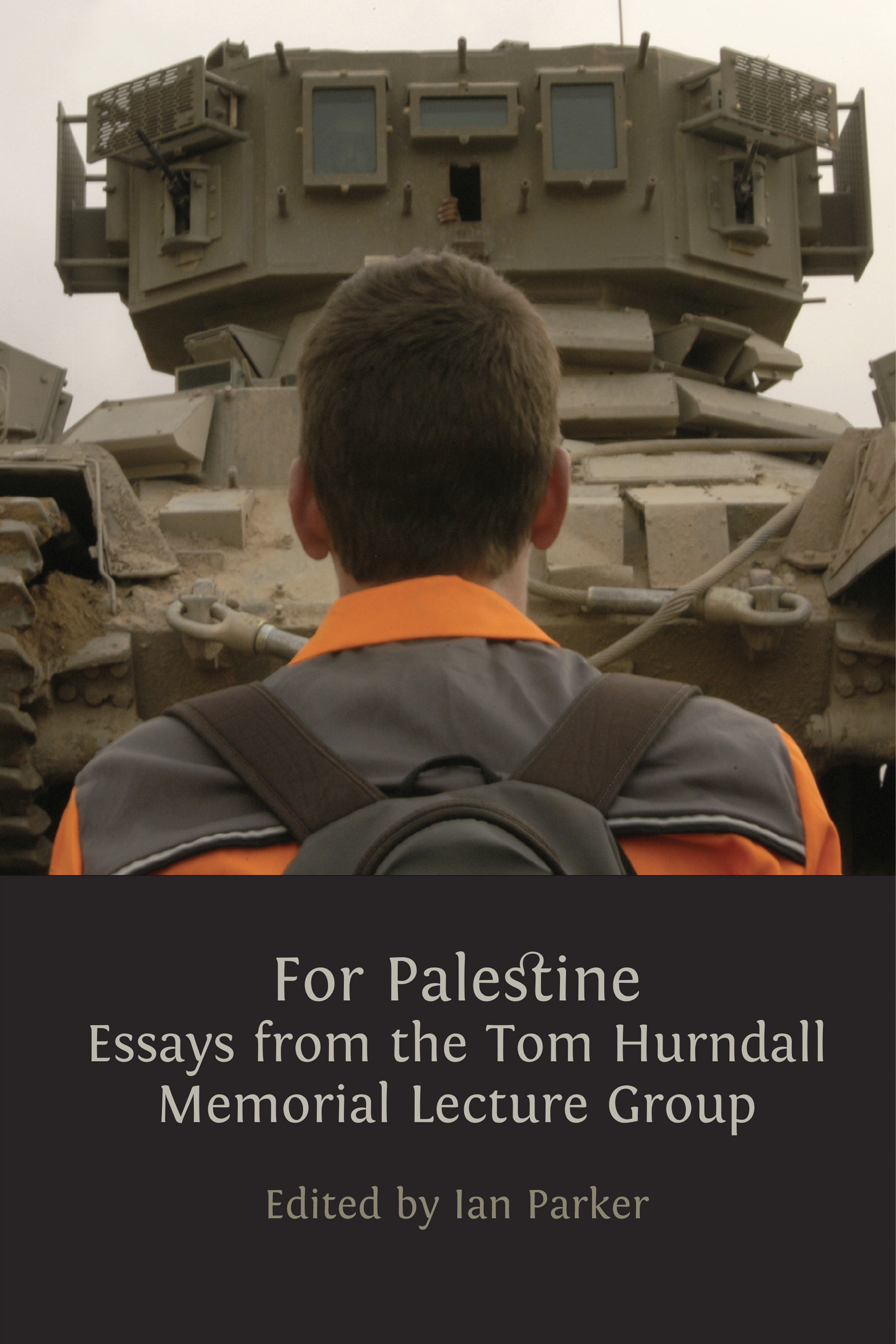

Fig. 11 Tom Hurndall, Tank in Rafah, April 2003. All rights reserved.

1 This lecture and chapter was extracted from Weizman, E., ‘The Politics of Verticality: The West Bank as an Architectural Construction’, Mute Magazine, 1 (2004), 27, https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/politics-verticality.