5. Anthony Soulby, Chapbook Printer of Penrith (1740–1816)

© 2023 Barry McKay, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347.05

The greater part of the commerce in dry goods in the city of Troyes is carried by the peddlers who come here to stock up on the Bibliothèque bleue. If the printshop of the widow Oudot were eliminated, this branch of commerce in the city of Troyes would soon wither and dry up […] the peddlers, no longer finding they could stock up on the Bibliothèque bleue as before, would not choose to go out of their way as they do now to come only to Troyes to buy merchandise and goods they could find just as well anywhere else.1

If one were to make a few minor changes to this statement from 1760 from the records of the city of Troyes in eastern France, one could well be referring to Penrith in the decades around 1800 and thus raising the question: how important was the production of chapbooks to the overall economy of this small Cumbrian market town, and, more importantly for the purposes of this chapter, who was responsible for their production?

Penrith’s geographical location made a not insignificant contribution to its commercial well-being, for it stood at the hub of an important group of roads that provided passage south towards Kendal and onwards into industrial Lancashire, south-east across the wastes of Stainmore to Scotch Corner and from there to the Great North Road from Newcastle to London, north to Carlisle and onwards to Scotland, and east into the northern Lake District, an area that was becoming increasingly attractive to an ever-growing number of tourists. Furthermore, and perhaps most significantly for this chapter, the town was situated along the chapmen’s routes — not only for those going north–south between Scotland, the Midlands, and southern England, and vice versa, but also for those seeking trade in the small towns and villages of the English northern counties and the Scottish borders.

Between the 1760s, when John Dunn began printing chapbooks in Whitehaven, and the early 1850s, twenty-six printers produced a little over five hundred chapbooks in several towns of what is now Cumbria.2 To this figure should be added fifty or so that were printed in Newcastle and that carry a Carlisle bookseller’s imprint. Only a few individual titles are recorded from the presses of several of these printers. Since these statistics are based on located and recorded examples, we must remember that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and it is entirely possible that a great many more await recovery or else have been irretrievably lost. Of these Cumbrian chapbooks, more than three hundred were printed in Penrith.3 The vast majority of those were printed in the period between 1779 — the date of the earliest known chapbook printed by Ann Bell — and 1815, the last year of printing activity of Anthony Soulby.

Bell’s first dated chapbook is preceded by the first separately printed edition of one of the classics of Cumbrian dialect literature, Isaac Ritson’s Copy of a Letter, Wrote by a Young Shepherd, to his Friend in Borrowdale.4 Whether or not this is truly a chapbook is possibly a moot point; it may have been a piece of printing for the growing tourist market, or intended to appeal to a local audience, or indeed both, and of course it would have reached at least some of its local market via the hands of chapmen. The text had first appeared in A Survey of the Lakes of Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire by the local surveyor, James Clarke.5 It also appeared in several editions in what one may call chapbook format from other Cumbrian printers, and featured in a number of other works printed in Cumbria. Isaac Ritson (1761–89), native of Eamont Bridge, a mile or so south of Penrith, was one-time schoolmaster at Penrith and a competent classical scholar, who later attended medical classes at Edinburgh and finally settled in London, where he contributed medical articles to the Monthly Review. He wrote the preface and much of the text of Clarke’s Survey, but the distinguished literary career predicted for him by his friends never materialized, as he died prematurely in Islington in 1789 at the age of just twenty-eight.

The number of chapbooks printed in Penrith argues that the town deserves recognition as one of the leading provincial chapbook printing towns. Although the number may be somewhat underwhelming when compared with the titles that appeared from printers in London and Newcastle, it is significantly greater than the numbers recorded for other towns noted for their contribution to chapbook literature, such as Alnwick, Banbury, or York. Two printers dominated the chapbook trade in Penrith: Ann Bell (fl. 1778–1811), from whose press we can identify 120 chapbooks, and Anthony Soulby, who printed at least 116 chapbooks. For the purposes of this study, I must, for want of more information on her activities, ignore Ann Bell, other than for the occasional reference, and concentrate on Soulby.

Anthony Soulby was born in 1740, the fourth of five children of John and Anne (née Langhorne), at Kirkby Thore, a small village a few miles south of Penrith but situated over the county border into Westmorland. Nothing is known of the first twenty-eight years of his life, but he was clearly working in the book trade in Penrith by 1768, when his name appears in an advertisement in the Newcastle Courant as one of the booksellers from whom could be had copies of The Child’s Tutor; or, Entertaining Precepts, published by White and Saint in Newcastle in 1768, but only recorded in ESTC in a single copy of the third edition of 1772.6

It appears that his eldest brother, John Soulby (1730–1805), was also trading as a bookseller in Penrith at a similar time, as he is named in another advertisement, also in the Newcastle Courant, which pre-dates the mention of Anthony by a few months, for the first part of Smollett’s The Present State of All Nations (1768–69).7 The question of whether the two brothers were trading together is raised by yet another advertisement in the Newcastle Courant, in which ‘J. and A. Soulby’ are jointly named selling the Universal Cash-Book and Newcastle Pocket Diary.8 This possibility is perhaps reinforced by the lengthy imprint of The Merry Companion (1772), which includes ‘Messrs Soulbys’ of Penrith.9 Their names also appear in the form of ‘A. & J. Soulby’ as agents for the Cumberland Pacquet on a number of occasions between January and November 1778, although when the newspaper was founded by the Whitehaven bookseller John Ware in 1774, Anthony alone was named as an agent. In February 1777, the Scottish bookseller Charles Elliot was in correspondence with John Soulby, pressing him for payment of a debt owed and promising: ‘I shall do everything in my power to sell [for] you some thousand of Undress’d Quil[l]s but has very little prospect I da[re] say I Have 40 Thousand Dressed Quil[l]s of one kind and another by me w[h]ich will last me Retailing some years.’10 Subsequently, no other printed reference to John Soulby can be found until a mention of him as ‘the late Mr John Soulby, formerly a stationer’ in Penrith in an announcement of the marriage of his daughter, Miss Ann Soulby, in 1807.11

To concentrate now on Anthony Soulby. From 1771 his name starts to appear with some frequency in book trade and proprietary medicine advertisements in the Newcastle Courant and later in the Cumberland Pacquet. In that year he married Ann Bird in Penrith. In 1772, on the birth of their son Samuel, Anthony Soulby is recorded in the Penrith parish registers as a bookseller, and on the births of their other eight children between 1773 and 1790 he is variously recorded as either a bookseller or a stationer. Although regrettably little is known of Anthony Soulby’s early trading activities as a bookseller, that begins to change during the second half of the 1770s. In 1778, his earliest known dated imprint appears on a work by the curate of nearby Edenhall and Langwathby, John Troutbeck’s A Sermon wherein Pious Education, and Timely Correction, of Children Are Recommended.12 Soulby’s choice of printer for this work is a little strange, for although John Bell was a printer working in Penrith at that time, and elsewhere in Cumberland both Carlisle and Whitehaven could have provided printing work, it was actually printed in Edinburgh by William Darling, a man who on three occasions between 1773 and 1775 had been sued by various London booksellers for selling unauthorized editions of their works.

Anthony Soulby’s name continues to crop up in book trade advertisements in the region’s newspapers throughout the late 1770s and the 1780s; his name appears among the subscribers to Ewan Clark’s Miscellaneous Poems;13 and in 1780 he is named as an agent on a handbill for Cooke’s English state lottery.14 Clearly the business was making steady progress. By 1783 he had at least two apprentices, neither of whom, it appears, was entirely happy in his situation, for a notice in the Cumberland Pacquet records that George Goulding, aged sixteen, and Isaac Hewetson, a Quaker, aged fifteen, had absconded from his service, ‘this being the second Elopement made by Goulding from his Servitude’.15 Soulby does seem to have had trouble with apprentices, for another, J. S. [John Sowerby?] Lough of Kendal, who had been apprenticed to Soulby in 1803, also absconded in 1809.16

Like his brother John, Anthony Soulby also had dealings with Charles Elliot, and the Edinburgh man seems to have been no happier with the younger brother. Soulby was in debt to Elliot for the balance of an account when Elliot wrote to him in February 1782:

I received Several Letter from you and 3 Rms of Vile Coarse paper which you charge 6/ for pr Ream it is No Earthly use to me and not worth 3/6 it is only indeed fitt a little House it cost besides 2/ some odd of Carriage […] Advise what I must do with your paper as I can make no Earthly use of it unless sold for waste — It was very odd of thinking of Sending me Such paper here, or that I would be foolish enough to accept of Such as a Just debt, if you mean to have any future commissions executed by me you will pay up the Old Balance & be more regular in future.17

It seems the Soulbys may have had an occasional tendency towards barter.

In May 1785 a Penrith bookseller, George Mark, of whom nothing else in known, placed an advertisement in the Cumberland Pacquet:

WANTED a STATIONER, and

BOOKBINDER,

Penrith, April 28, 1785.

That chuses to Purchase a Genteel Stock in Trade, consisting of a great Variety of Books and Stationary [sic] Wares, of all Sorts; a Good Circulating Library, and all Sorts of Utensils for Bookbinding. May enter into full Business, in a Well A[c]custom[e]d Shop, at Penrith, in Cumberland, which is well Situate for the Business, in a fine Country, and a very great Market on Tuesdays.

For further Particulars, apply to George Mark, Bookseller, Stationer, and Bookbinder, in the Market-Place who will treat about the same.18

It is not unreasonable to suggest that Anthony Soulby was the man who would ‘chuse’ to purchase this business. While no advertisement has been located that announces a change of ownership in the business, the circumstantial evidence is compelling for at some point in the second half of the 1780s he issued A Catalogue of A. Soulby’s Circulating Library.19 Although undated, I suggest the catalogue dates to the period 1785–89. It was printed by John Bell, the first — and until this time the sole — printer in Penrith, who disappears from the record sometime before 1789, when his wife, or perhaps widow, Ann Bell, began her career as a printer. The catalogue advertised:

At his Shop in Penrith, May be had a great Variety of Bibles Testaments, Prayer-Books, Blank Books for Merchants Accompts, and all Sorts of Stationery Wares, upon reasonable Terms. All kinds of books bound at a reasonable price. — Ready Money for any Library, or Parcel of old Books. New Publications from London, at the Advertised Prices, or by the Fly at one-penny each Pamphlet.

In addition, Soulby had ‘Left with Mr. John Pattinson, Grocer, in Aldston [i.e. Alston], A Large Quantity of School Books’, and he also offered ‘Chapman Books, one hundred different Sorts and upwards’. Alas, we have no definite proof that Soulby was trading from the Market Place in Penrith’s town centre before 1806, but it would seem a most desirable location for a growing retail business. Only two of his publications, both undated chapbooks, give this as his address in the imprints. Since he did not include printing in references to the range of services he offered before 1794, such references cannot be counted as evidence for his presence at the address from an early date.

Soulby’s trade connections as a bookseller were widespread. Charles Elliot in Edinburgh has already been noted. The day-books of another Edinburgh house, Bell and Bradfute, show he was doing business with them in the 1790s,20 as well as with Benjamin Crosby in London. He also had dealings with John Ware of Whitehaven, including on one occasion in 1800 taking six and a half dozen individual songs by Charles Dibdin.21 In 1802 he supplied the poet Robert Anderson with a song by Dibdin and a collection of the most popular songs, before spending a pleasant evening with him.22 Not all of Soulby’s relations with customers were quite so agreeable, however. On 3 February 1802, Dorothy Wordsworth noted that she had written to him, apparently concerning a copy of Chaucer that was ‘not only misbound but [also] a leaf or two wanting’.23

It is in 1794 that we first have firm evidence of Anthony Soulby as a printer. In that year he printed a slender ten-page quarto ‘Rules and Orders’ for a Friendly Society.24 It is not impossible — indeed, it is highly likely — that he printed his first chapbook the following year. A copy of Three Choice Songs, printed in Penrith, in Carlisle Public Library carries a manuscript inscription dated 1795.25 If this had been printed by Ann Bell, it seems unlikely that, having traded under her own name since at least 1789, she would have referred to her business as the ‘new’ Printing Office. The woodcut on the title page has not been found used elsewhere by Soulby — nor by any other Cumbrian printer — but this is not surprising because Soulby eventually held a large stock of woodblocks and only rarely made repeated use of them. It does, however, pose the question as to why Soulby did not include his name in the imprint: I submit that it is possible the chapbook was commissioned by a chapman who did not wish his competitors to know the source of his supply.

Examples of Soulby’s book printing are uncommon and for the most part date from 1798 onwards; furthermore, only very few examples of ephemeral printing from his press are known. Thus, when one considers that Ann Bell was well into the production of her chapbooks, and that Soulby’s own circulating library contained ‘one hundred different Sorts and upwards’ of chapbooks, one can only suppose that Soulby saw a potentially profitable business opportunity in the production of these small books. In 1796 he advertised in the Cumberland Pacquet for a journeyman printer.26 Who filled this post is not known, but it might have been one James Langden, who was in the town in 1800. With a full-time journeyman printer, and therefore a press to be kept occupied, it seems not improbable that chapbook printing would be an answer to any slack press-time. Soulby printed at least 116 chapbooks between 1795 and 1815. An average of six or so a year is hardly a dramatic output, but equally is not a figure to be dismissed lightly. We must also bear in mind that he may have printed many more, as all the output figures for chapbooks in this study are based on known and recorded copies, and we do not know what proportion of his output those represent. In one instance we have evidence that he printed 2,000 copies of a chapbook, yet only rarely are surviving examples known in more than one copy.

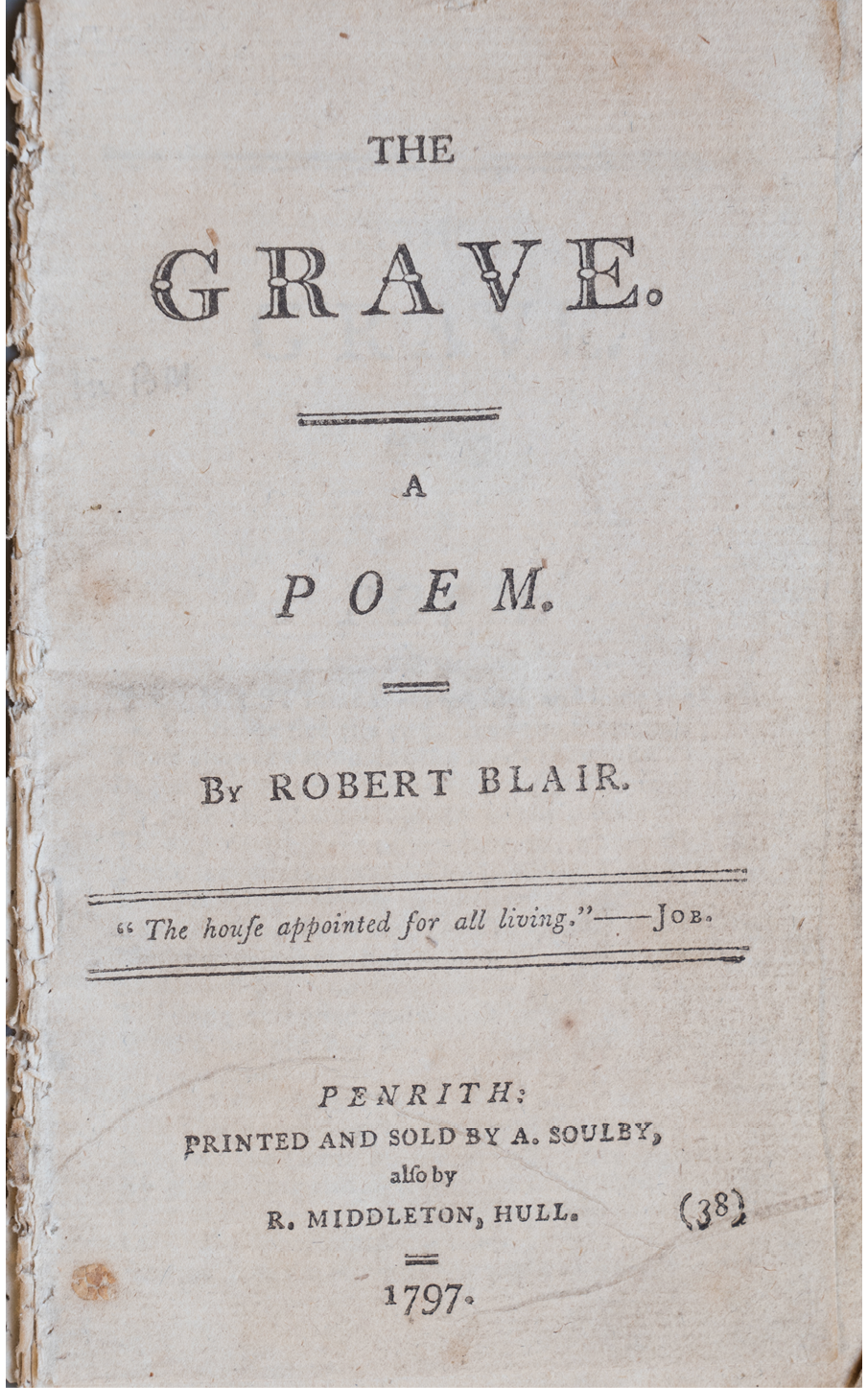

Only three Soulby chapbooks are dated, the earliest of which — an edition of Robert Blair’s The Grave — was printed in 1797 (Fig. 5.1).27 The imprint states that it was also sold by R. Middleton of Hull, a geographically rather distant trade connection, and a bookseller unrecorded in Chilton’s study of the book trade in Hull.28 The Grave also carries a series number, in this case no. 38, on the title page. The four other chapbooks printed by Soulby that carry series numbers are The History of Adam Bell (no. 23), The Adventures of Houran Banow (no. 25), The History of Selico (no. 27), and The History of Timor (no. 28). If these series numbers are to be taken at face value and were used in a chronological sequence, then there must be at least another thirty-three Soulby chapbooks still awaiting recovery, all of them presumably dating to 1797 or earlier.

It was at about this time that Soulby’s short-lived, though not undistinguished, career as a book printer began. In 1798 he printed A Sentimental Tour, Collected from a Variety of Occurrences, from Newbiggin near Penrith, Cumberland, to London by George Thompson of Esk-Bank Academy.29 As stated in the advertisement on the back page of his circulating library catalogue, Soulby had established a trading presence in the town of Alston, less than twenty-five miles from Penrith but remotely situated high in the North Pennines. In 1800 Soulby is listed as a bookseller in the imprint of Poems, on a Variety of Interesting Subjects, attributed to a Mr Cowan of High Wigton, Dumbarton, printed in Alston by John Harrop, with whom Soulby may have had other dealings.30

Fig. 5.1. Robert Blair, The Grave. Author’s collection.

On 25 May 1799 the day-books of Thomas Bewick’s workshop record that a ‘Front[i]s.[piece to read[in]g [made] Easy’ was supplied to ‘Jno Soulby Printer Penrith’ at a price of 16s. 0d., as well as ‘3 small Cuts Do’ at 4s. 6d. each.31 The ‘Jno Soulby’ named here is more likely to have been Anthony Soulby’s son John rather than his brother. Woodcuts intended for this publication had already been ordered from Bewick by John Harrop in 1797 and 1798. Nigel Tattersfield has suggested that this publication may have originally been Harrop’s idea, but it seems that he abandoned the publication and either handed over or sold the cuts to Soulby, for it was from his press that the title appeared, undated but with a preface dated Penrith, 1800.32 Tattersfield also suggests that a cut of a piper beside a stream and beneath overarching trees was one of the three small cuts ordered from Bewick on 25 May 1799.33 The cut was used with a chapbook titled The New Songster and, together with a number of typefounders’ stock blocks, with W. Thompson’s A Discourse on the Nature of Christ’s Kingdom (1807).34

In the early years of the nineteenth century Soulby also printed an anonymous edition of The Pleasing Instructor by Cumbrian-born Anne Fisher (1719–78).35 The Bewick workshop day-books reveal that on 27 February 1802 Soulby was charged £2. 4s. 0d. for ‘2 Cuts pleasing instructor’.36 Then in March 1805 Soulby wrote to Bewick to commission a cut of ‘The Basket-Maker’, an illustration that appears opposite page 30 of The Pleasing Instructor.37 It seems reasonable to posit that the book was published later in 1805, or shortly thereafter. Benjamin Crosby, the London bookseller also named in the imprint, appears to have been the London agent for a number of Soulby’s publications.

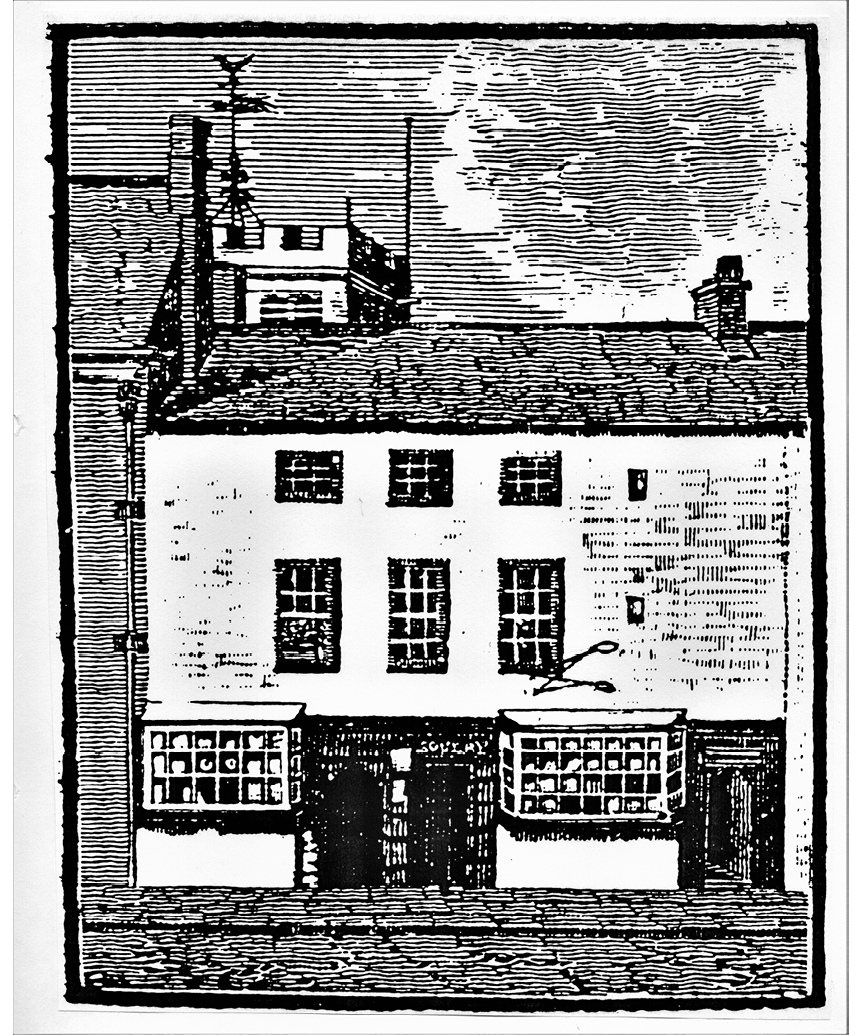

Over the years Soulby ordered a number of woodcuts from Bewick, including four on 24 April 1804, two of which appear in Soulby’s edition of The New Songster; or, Musical Olio, together with the cut of a piper beside a stream noted above.38 Not all the cuts he acquired from Bewick were for his more prestigious book printing, as cuts were also ordered for use in purely ephemeral printing. One such is a race cut, ordered on 28 March 1808, which, rather than a generalized example of a not uncommon image, is quite specific to the Penrith racecourse. With the letter in which he placed the order, Soulby included a crude sketch, ‘not taken from the spot […] Mr Bewick may do it as he thinks will look best.’39 Among the details Soulby requested be included in the block were ‘Penrith Beacon, with a Man standing beside it — viewing’. This nice attention to detail is clearly visible in the finished cut, which was used on a poster for the Inglewood Hunt Penrith Races of 1811.40 Penrith racecourse was situated on the north side of the town, and the Beacon is shown on the cut positioned at its correct location. Posters for Penrith races exist for several years from this time until the late 1820s, but this is the only one known to have come from Soulby’s press. The cuts used on the later examples differ from the Soulby block, and none includes Penrith Beacon until a poster of 1828, printed by George Foster in Penrith, which once again made use of the cut made for Soulby. There is a splendid engraving of Penrith Beacon which Thomas Hugo included in his collection of Bewick woodcuts, with the information that it came ‘from Soulby’s Office, Penrith’.41 The most interesting of the cuts from the Bewick workshops, however, is one made by Edward Willis and sold on 15 March 1806 for 15s. 0d., which shows us Soulby’s shop in the Market Place in Penrith, from which his chapbooks were issued (Fig. 5.2).42

In terms of broad subject matter, 40 per cent of Soulby’s chapbooks were ‘entertaining histories’, heroic ballads in either verse or prose, and similar material, 25 per cent were garlands or songbooks, 25 per cent were religious texts or tales of a moral and improving nature, and the remaining 10 per cent comprised miscellaneous titles. Unlike several other Cumbrian chapbook printers, he did not ‘pirate’ many of the chapbooks from Hannah More’s Cheap Repository, contenting himself with just two, The Two Soldiers and The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain.

Fig. 5.2. Anthony Soulby’s shop in the Market Place in Penrith. Author’s collection.

Among the entertaining histories, Soulby issued editions of most standard favourites, including Robin Hood, where, with a fine measure of pedantry, he eschewed the usual form of the title and instead published it as The History of Robert Earl of Huntington, Vulgarly Called Robin Hood. He also published an edition of The History of Adam Bell, Clim of the Clough and William of Cloudeslie, a long-standing title first known in printed form in a few surviving leaves from an edition printed by Wynkyn de Worde, c.1505. Since the action in this ancient tale took place in Inglewood Forest, a few miles from Penrith, it would have been a strange omission had Soulby not printed it. This is one of those titles with a series number on the title page, so perhaps dates from 1797 or a little before. Ann Bell also printed an edition of Adam Bell, but not until 1805. This is not the only instance where the two contemporary Penrith printers issued their own editions of chapbooks. Besides Adam Bell, both Soulby and Bell published Antonio and Clarissa, Captain James Hind, Ducks and Green Peas; or, the Newcastle Rider, The Valiant London Apprentice, The Great Messenger of Mortality, Tom Hickathrift, Robin Hood, Seven Wise Masters, and The Shepherdess of the Alps. Tom Hickathrift was issued in two parts by Soulby, and almost certainly by Bell, too, but only part two of her version has been located.

Several histories were printed by Soulby in more than one edition. His Conquest of France used a different woodcut for each edition, while both editions of Sir James the Rose used the same cut, though Soulby’s name does not appear on one of them. One wonders whether this might have been an instance where he was commissioned by a chapman to print copies without an imprint, but also printed run-on copies with his imprint.

It seems that there were at least three editions of Sir Lancelot du Lake. One edition has an image of a man taking a woman by the arm, which could, at a stretch, be regarded as fitting the tale, since when he ‘armed rode into the forest wide’ Lancelot did indeed come across ‘a damsel fair’.43 Another edition, however, has a damaged woodcut of three cripples, which could, I suppose, represent those knights already wounded by Tarquin.44 What is strange about Soulby’s use of this woodcut is that he had another, perhaps more suitable, image of a knight fighting a giant which saw service with his editions of Tom Hickathrift, on the title pages of both parts, and Sir James the Rose. There may even be a third edition of Sir Lancelot du Lake, for a bookseller offered a copy for sale some years ago, noting that it also included a song, ‘Ma chère amie’, which is not found with the other editions.45 Soulby’s version of Sir Lancelot du Lake is given a local setting by having the action take place in Inglewood Forest, which was also the haunt of Adam Bell and his fellow northern archers, and of King Arthur’s court, which sat at Eamont Bridge, a couple of miles south of Penrith. Evidence of the supposed veracity of the tale is provided by the statement: ‘Taken from an ancient Manuscript, losely [sic, lately?] found in the ruins of a Danish Temple, called Mabourgh Castle, by Mr. Scullough, of Emont Bridge, Guide to the antiquities there.’

Among the less common histories printed by Soulby, three stand out. The histories of Selico and of Timur display a certain uniformity of design in the layout of the titles, and, since both carry series numbers, they perhaps again date to 1797 or a little before. The History of Timur is not known to have been published by any other chapbook printer, and the source of the tale presents an interesting problem. Timur is a variant of Tamburlaine, and the city of Ispahan (Isfahan in modern Iran) is memorable as the place where Tamburlaine erected a kelleh minar, a tower of 70,000 skulls, in order to deter other cities from resisting his force of arms. This scarcely bears any resemblance to the actual tale of the ups and downs of a merchant’s life recorded in this chapbook, and summarized at some length on the title page. Soulby did, however, draw on the Arabian Nights as a source for another chapbook, The Adventures of Houran Banow, which derives from the voyages of Sinbad, and he listed a four-volume set of the Arabian Nights in the catalogue of his circulating library. The design of the title page of Houran Banow resembles those of Timur and Selico, and it, too, carries a series number.

The History of Selico is the most interesting of this group. The tale is presumably an abridgement of a work by Jean Pierre Claris de Florian; indeed, the chapbook is attributed to him in a manuscript annotation to the copy in Carlisle Library.46 It first appeared as an English verse translation from Florian’s French prose in a 32-page octavo printed by R. Trewman and Son in Exeter and sold in London by G. and T. Wilkie, c.1794.47 At the foot of the title page is a note: ‘N.B. The Profits arising from the Sale of this Poem, are intended to be applied to the Subscription established for effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.’ Another edition was printed in London around 1800 by T. Maiden for J. Roe and Anne Lemoine, and the story was later dramatized by George Colman the Younger as The Africans; or, War, Love, and Duty, but neither the Soulby nor the London chapbooks make any mention of contributions to abolitionist funds.

In the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum is a bound volume of thirty Soulby chapbooks.48 One of these chapbooks, Friburg Castle, carries an imprint that merely reads ‘printed in the present year’, but includes an ornament used by Soulby in An Account of a Most Surprising Savage Girl, which is also in the National Art Library volume.49 The majority of the chapbooks have an ‘advertisement’ continuation of the imprint, which takes one of three forms:

(i) Thirteen chapbooks include the phrase ‘of whom may be had a large assortment of histories, songs, patters, children’s books, &c.’, a formula used by Soulby in seven other places. One of this group, The Shepherdess of the Alps, is on paper watermarked 1802, so if we accept Edward Heawood’s dictum that most paper in England was used within three years of manufacture, and bear in mind that one of the titles, The Life, Adventures and Glorious Sea Engagements of the Brave Admiral Blake, is described as ‘a companion to the life of the immortal Nelson’, a Soulby chapbook of which no copy has come to light, then this would allow us to place this group into the period between c.1802 and c.1807, or slightly later.

(ii) Five chapbooks describe Soulby’s shop as one ‘where may be had a great variety of histories, songs, patters, children’s books, &c.’, a phrase used by Soulby on two more occasions. One of the Soulby songbooks that carry this phrase includes a song celebrating Wellington’s victory at the battle of Salamanca, which would date the chapbook to sometime after (probably only shortly after) July 1812.

(iii) The final group in this volume, which may well represent (in part at least) Soulby’s swansong as a chapbook printer, include the phrase ‘who has constantly on sale, a large and general assortment of histories, songs, godly books, &c.’ This phrase, which was also repeated by Joseph Allison, who used several woodcuts from Soulby’s shop, appears with eight Soulby chapbooks, including his final known dated chapbook, Fun upon Fun; or, The Comical and Merry Tricks of Lepar the Taylor, printed in 1815. Seven of these chapbooks are in the National Art Library volume, and the other is a chapbook titled A Garland of New Songs (including Peace and Plenty), the subjects of which probably celebrate the battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815.

A quarter of Soulby’s chapbook output consisted of small songbooks, invariably of eight pages and usually described on the title page as ‘choice’, ‘excellent’, or ‘new’, and not infrequently as ‘choice new’ or ‘excellent new’. Songs by Burns and Charles Dibdin are occasionally included, and there is a fair sprinkling of patriotic material, as might be expected at a time when the country was at war. There are, however, few that relate to the land war, Sandy of the Forth and The Battle of Salamanca being rare examples. Most of the martial songs glorify the British navy, and almost invariably the role of the ordinary seaman. There is also a fair selection of love songs — some platonic, others decidedly less so. It was doubtless the latter that prompted a local commentator, R. S. Ferguson, to write about Jack the Piper; or, Friar and Boy: ‘If Anthony Soulby considered this very coarse ballad a “Godly Book”, he must have had a great imagination.’50

Another quarter of the Soulby chapbooks consisted, broadly speaking, of godly books or tales of a morally improving nature, some of the type that Charles Lamb lambasted as the writings of ‘the cursed Barbauld Crew, those Blights and Blasts of all that is Human in man and child’.51 Of overtly theological pieces, Soulby’s edition of Robert Blair’s The Grave, printed in 1797, has been briefly mentioned above. First published in London in 1743 as an octavo, a provincial edition, also in octavo, was printed in Darlington in 1776 by Marshall Vesey for the Durham bookseller Patrick Sanderson, who was also Vesey’s father-in-law. Thereafter a number of duodecimo editions appeared in Scotland from printers in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Perth, and Paisley between 1768 and 1798. English editions were printed by Catnach in Alnwick in 1796 and Merridew in Coventry, c.1799. Soulby also issued a second, undated edition of this title, and in the 1830s Fordyce of Newcastle printed an edition that was sold by J. Whinham of Carlisle (all the known chapbooks that carry Whinham’s imprint as a bookseller were printed by Fordyce).

The Great Messenger of Mortality appeared in a number of broadside editions, including from Bow Churchyard and from John White in Newcastle, but the only known chapbooks are from an unknown printer in Edinburgh (c.1800?), John Marshall in Newcastle sometime after 1810, and three Cumbrian editions. These last were published by Soulby, c.1802–c.1807 (based on the form of advertisement in the imprint), Ann Bell, with a particularly graphic image on the title page, and Michael and Richard Branthwaite in Kendal, sometime after 1803. Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained was quite widely published in both broadside and chapbook editions.

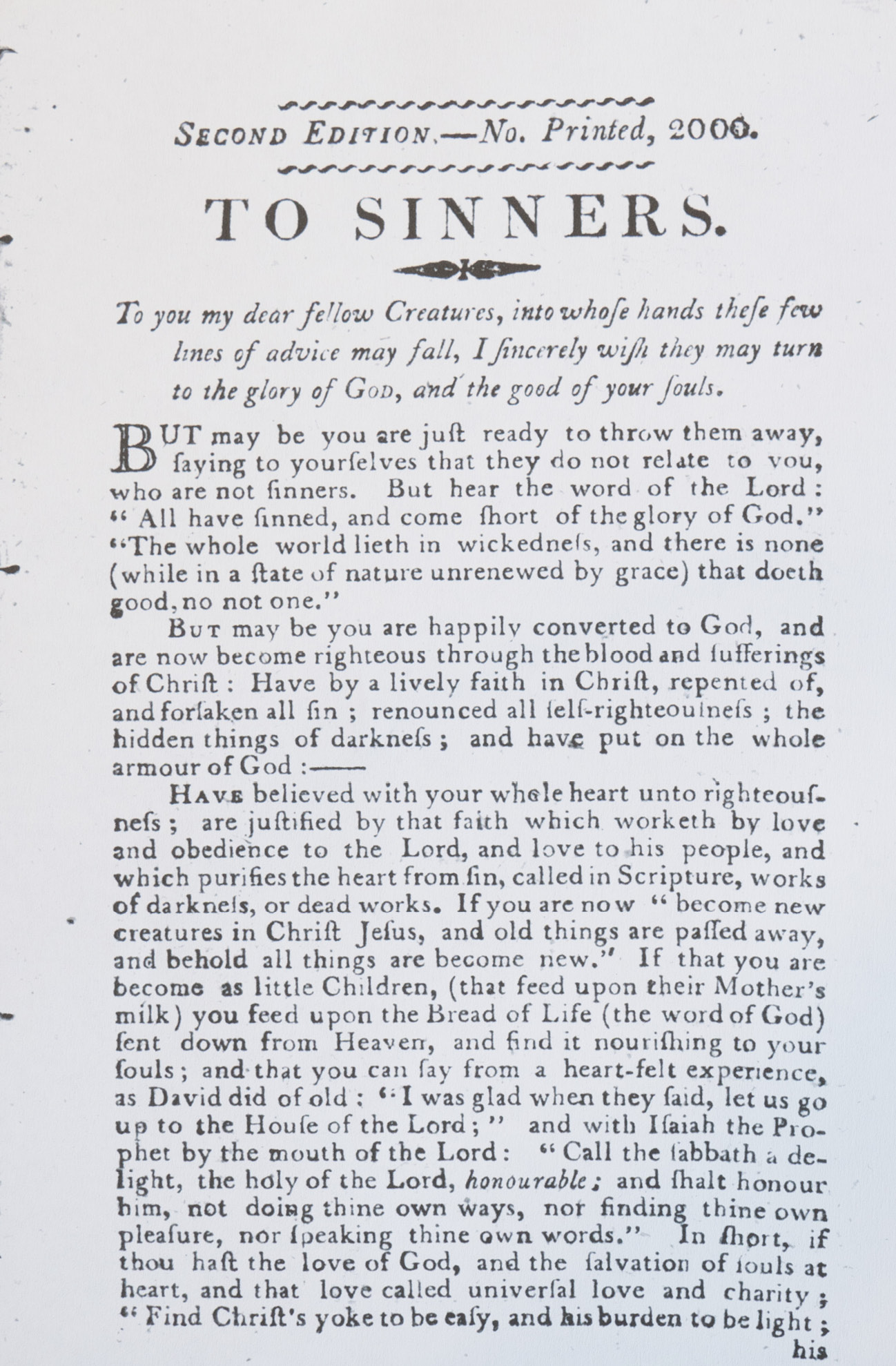

Two of Soulby’s theological chapbooks may be the work of a local cleric, and they read somewhat like sermons. The title page of To Sinners states that it was printed in two editions and, uniquely in this writer’s experience, records the print run, which amounted to 2,000 copies (Fig. 5.3). The presence of a drop-title may suggest that this could be considered a tract rather than a chapbook — but then, what is a chapbook? When asked to address the problem of definition at a conference at the Victoria and Albert Museum some years ago, I discussed the matter with the late Professor Richard Landon of Toronto. Tongue-in-cheek, he offered the suggestion that a chapbook was ‘a wee book vended by a chap’. I think another attendee remarked that, while he was not sure what exactly constituted a chapbook, he ‘knew where he kept his collection of them’.

An Address to Parents is known in three copies. That in the Carlisle Public Library is unmarked, but one in a private collection and one in Cambridge University Library both carry the same careful manuscript textual excisions, which leads one to think they may well have been authorial amendments post-printing. In the text the author speaks highly of the Sunday school movement, which had been started by Robert Raikes in Gloucester in 1780 and spread so rapidly that by 1787 there were 1,800 pupils in Manchester and Salford alone. Indeed, one writer has noted that ‘it was a significant characteristic of Sunday schools in the North of England and Wales that they were attended by adults as well as children’.52 The only other chapbook edition located under this precise title was printed in Birmingham by Groom, c.1855; however, the two texts have not been compared, so the latter may not be a reprint of the Soulby chapbook.

Fig. 5.3. To Sinners. Author’s collection.

The Shepherdess of the Alps is a translation of Jean-François Marmontel’s La Bergère des Alpes, one of the series of ‘Contes moraux’ begun in 1758, and was also the subject of an opera by Charles Dibdin in 1780. ESTC records chapbook editions in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Preston, and York. Soulby, Ann Bell, and Joseph Allison all printed editions in Penrith. The wording of the advertisement following the imprint in Soulby’s edition may suggest a date of c.1802–c.1807. Of the two known copies of Soulby’s edition, the one in the National Library of Scotland is printed on pale blue paper.

Again, the wording of the imprint advertisement suggests that The Painful Sickness and Happy Death of John Boltwood falls into the c.1802–c.1807 period. Written by G. Collison (d.1847), it appeared in the Cottage Library of Christian Knowledge (1806?). Apart from Soulby’s edition, ‘published by particular request’, only one other commercial edition of this chapbook has been located and that, too, was printed in Penrith, by James Shaw (fl.1813–34). One wonders if the ‘particular request’ that Soulby publish this text was made by the same local cleric as may have written the titles noted above.

The Sunday schools and charity schools had a significant effect on literacy, although their efforts in this worthy direction — together with the output of religious publishing societies — was in no small part intended to supplant ballads and chapbooks with more moral reading matter. One of the leaders of this movement for suitable cheap literature was Hannah More (1745–1833) and her contributions to the genre were well written and, by and large, fair-minded. The success of More and her fellow contributors to the various Cheap Repository Tracts led to an over-inflation of the genre, as worthy officials of like-minded bodies climbed on to the bandwagon and flooded the market with many prosy, sententious, and occasionally downright nauseating little tracts — some, one suspects, with texts that were written around the images available to the various proprietors. Yet, it is possible that the demand for small, cheap books resulting from the increase in literacy brought about by the Sunday school movement and this outpouring of subsidized cheap literature actually stimulated the commercial chapbook trade, for there was a notable and dramatic increase in production after 1800. The Cheap Repository for Moral and Religious Publications had set out deliberately to challenge the chapbook trade by producing and distributing their publications in a like manner. They published eighty-six titles in 1795 and 1796, and at the end of their first year the treasurer reported that ‘about two million have been printed […] besides great numbers in Ireland’.53 That is an average print run of over 23,000 copies of each title.

One tract from the Cheap Repository that crossed the divide from the subsidized to the commercial chapbook trade was Hannah More’s The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain, which first appeared in 1795. A number of editions came from the Cheap Repository’s printers — Marshall, Hazard, and Evans, as well as their Irish printers — and there were editions from similarly motivated American societies. The text was also translated into Welsh in 1810, Russian in 1815, and there was even an edition in Syriac. Apart from the religious societies’ editions, there were only a few commercial editions. Outside Cumbria, copies are only known from Swindells in Manchester, Randall in Stirling, and ‘printed for the booksellers’ in Edinburgh. Soulby’s advertisement following the imprint suggests that his edition belongs to the period 1812–15. If so, he was preceded in Penrith by Ann Bell, who printed it in 1805. George Ashburner in Ulverston also printed an edition, between 1810 and 1820.

What this and other ‘piracies’ of religious titles suggests is that commercial chapbook printers had scant regard for any concept of copyright. One wonders whether there was a feeling that any chapbook text was effectively in what we would today call the ‘public domain’, so reprinting was not considered an illegal act. Given the number of such titles that came from printers in the north of England and Scotland, one suspects that printers a long way from London were not overly concerned about possible copyright claims. Equally, it might be that Hannah More and her fellow authors were content to see their improving texts circulated as widely as possible.

Over his years as a printer, Soulby accumulated a wide range of illustrative and decorative materials, eventually numbering more than 130 known pieces. Of these, some thirty are typefounder’s casts, several of which are to be found in the Stephensons’ Specimens of 1796.54 Over thirty of his woodcuts could be described as fine work. Many of these are known to have come from the Bewick workshops, but only very rarely are they used in chapbooks. The cut that appears with Breach of the Sabbath is certainly in the ‘fine’ category, and while it cannot be specifically identified, it may be one of those (on unspecified subjects) that Bewick supplied to Soulby on 3 May 1799.55

The remainder of Soulby’s cuts can be described as ranging from near-fine to downright crude. Two out of this broad and thoroughly unprofessional classification appear to be factotum cuts. One showing two Native Americans approaching a man seated at a desk appears on the title page of Five Excellent New Songs (containing Sweet Poll), and within the text of both The History of Lawrence Lazy and The Famous History of the Valiant London Apprentice, in each case with a letter P in the hole. If there is an element of doubt as to whether this particular cut was holed for the insertion of a letter, there is no doubt about another factotum cut of a ship, which is also found in the Valiant London Apprentice, with no letter in the hole, in Richard Whittington, with a letter U in the hole, and on the title page of Antonio and Clarissa, with a letter N in the hole.

As is perhaps to be expected at this period, the long ‘s’ is a frequent feature of the typography of Soulby’s chapbooks. Occasionally the compositor had to fiddle to fit copy to the space available. One example is The History of Nicholas Pedrosa, which is set at twenty-eight lines to the page up to page 18, when it is suddenly leaded out to reduce the lines to twenty-two to the page. Even so, the copy would not fill the required space, so a song, Ben Backstay (generously leaded), occupies the final two and a half pages of the chapbook. The opposite problem arose with the setting of The History of Guy Fawkes, where part of the way down page 21 a smaller type size was suddenly adopted.

For the last decade of Soulby’s life there is little surviving evidence of any activity other than chapbook printing. In 1809 his name appears as a bookseller for a book printed by one John Soulby in Barnard Castle, whose familial relationship to Anthony Soulby (if indeed there was one) has proved elusive. His imprint appears on a broadside account of a murder trial in 1814. But perhaps the most surprising item from Soulby’s business to survive from this period is another edition of the catalogue of his circulating library, which — unlike the earlier edition of the 1770s, issued before he commenced as a chapbook printer — contains no chapbook titles. Clearly, now that he was a printer of this important contribution to the reading matter of the commonality of England, he was not going to lend them to anyone when he could sell them.

Anthony Soulby’s wife died in January 1814, and he himself died in January 1816. His will had evidently been drawn up before his wife’s death as he makes bequests to her through his executors (one of whom was a yeoman named Isaac Hewetson, possibly the same as his absconding apprentice from decades before, although the name was not uncommon in Cumberland) and thence to his surviving children. These include household goods, as well as properties in Penrith and Kirkby Thore, yet no mention is made of his business premises or stock-in-trade.

For over thirty years Ann Bell and Anthony Soulby had been the printers in Penrith, and their success as chapbook printers could have been a draw to others keen to profit in that market. Francis Jollie senior, a printer of chapbooks in Carlisle, sent his son, Francis junior, to Penrith, where between 1812 and perhaps 1815 he printed chapbooks and made a couple of contributions to a pamphlet war over a local execution, wherein various clerics sought not to argue the pros and cons of capital punishment but rather competed in print over their ability to quote from scripture. After Soulby’s death, a number of his woodcuts were used on chapbooks printed in Penrith by Joseph Allison. Several other printers established in the town in the later years of Soulby’s life also printed a few chapbooks. Nonetheless, it is the work of Ann Bell and Anthony Soulby that raised the profile of Penrith to a significant place in the pantheon of English chapbook printing towns, and doubtless also attracted chapmen to the town, with the same sort of beneficial effects as were noted for the city of Troyes at the beginning of this chapter.

1 Robert Mandrou, De la culture populaire aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: La Bibliothèque bleue de Troyes; quoted in Roger Chartier, The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), p. 261.

2 Until 1974, what is now Cumbria consisted of the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, together with Lancashire north of the Sands and the Sedbergh district of Yorkshire.

3 This is almost certainly a conservative figure as, at the time of writing, the author has not completed examination of a number of uncatalogued chapbook collections, including, most notably, those in Newcastle University Library, wherein a number of chapbooks printed by Francis Jollie junior during his short sojourn in Penrith have already been found.

4 Copy of a Letter, Wrote by a Young Shepherd, to his Friend in Borrowdale, new edn (Penrith: printed for J. Richardson, bookseller, 1788) [ESTC N27616].

5 James Clarke, A Survey of the Lakes of Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire (London: printed for the author, and sold by him at Penrith, Cumberland; also by J. Robson, and J. Faulder, New Bond Street; P. W. Fores, No. 3, Piccadilly; the engraver, S. J. Neele, 352, Strand, London; L. Bull and J. Marshall, Bath; Rose and Drury, Lincoln; Todd, Stonegate, York; Ware and Son, Whitehaven; C. Elliot, Edinburgh; and most other booksellers in the kingdom, 1787) [ESTC T168323].

6 Newcastle Courant, 1 October 1768, p. 1.

7 Newcastle Courant, 4 June 1768, p. 4.

8 Newcastle Courant, 26 November 1768, p. 3.

9 The Merry Companion, being a Collection of English and Scottish Songs, Ancient and Modern (Newcastle upon Tyne: printed by I. Thompson, Esq., 1722; for John Brown; and sold at the New Printing Office, in the Side; by Mr Charnley, Mr Slack, Mr Chalmers, Mr Akenhead, Mr Barber, and Mr Atkinson, booksellers, in Newcastle; also by Mr Sanderson, Mr Manisty, and Mrs Clifton, in Durham; Mr Graham, in Sunderland; Mr Oliver, in Shields; Mr Vasey, and Mr Darnton, in Darlington; Mrs Hodgson, in Carlisle; Mr Muckle, in Barnardcastle; Mr Corney, and Mess. Soulbys, in Penrith; Mr Ashburner, and Mr Fenton, in Kendal; Mr Greenwood, in Kirbylonsdale; Mr Dunn, in Whitehaven; Mrs Cowley, in Cockermouth; Miss Furnance, in Wigton; Mess. M’Lacthan and Chalmers, in Dumfries; Mr Richardson, in Annan; Mr Elliot, in Kelso; and Mr Graham, in Alnwick) [ESTC T77503].

10 Peter Isaac, ‘Charles Elliot and the English Provincial Book Trade’, in The Human Face of the Book Trade: Print Culture and its Creators, ed. Peter Isaac and Barry McKay (Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies; New Castle, DE, Oak Knoll Press, 1999), pp. 97–116 (p. 109); quoting John Murray Archives, Letter-book 2, folio 111, Charles Elliot to John Soulby, 6 February 1777.

11 Newcastle Courant, 8 August 1807, p. 4.

12 I am grateful to Dr Sydney Chapman and Judith Clarke of Penrith Museum for drawing this book to my attention.

13 Ewan Clark, Miscellaneous Poems (Whitehaven: printed by J. Ware and Son, 1779), p. xx [ESTC N6099].

14 Penrith Museum.

15 Cumberland Pacquet, 4 November 1783, p. 3.

16 Cumberland Pacquet, 21 March 1809.

17 Isaac, ‘Charles Elliot and the English Provincial Book Trade’, p. 109; quoting John Murray Archives, Letter-book 6, folio 34, Charles Elliot to Anthony Soulby, 10 February 1782.

18 Cumberland Pacquet, 3 May 1785, p. 3. The same announcement appeared in the Newcastle Courant, 14 May 1785, p. 3, but advertising for a ‘Bookseller and Stationer’.

19 A Catalogue of A. Soulby’s Circulating Library (J. Bell, printer, Penrith) [private collection].

20 I am grateful to Dr Iain Beavan for this information.

21 Carlisle, Cumbria Record Office, Day-books of John Ware, 16 July 1800.

22 I am grateful to Sue Allan for drawing this reference in Robert Anderson’s diary to my attention.

23 Dorothy Wordsworth, The Grasmere Journals, ed. Pamela Woof (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), p. 62.

24 Rules and Orders of the Friendly Society, which Commenced the 11th Day of January 1783, and Continues at the House of Thomas Dixon, George-Inn, Kirkoswald, in the County of Cumberland (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby, 1794).

25 Three Choice Songs: 1. Liberty-Hall; 2. Roger & Peggy; 3. Vicar & Moses (printed at the new Printing Office, Penrith) [Carlisle Library, Local Studies, M176 (86)P].

26 Cumberland Pacquet, 9 February 1796, p. 3.

27 Robert Blair, The Grave, a Poem (Penrith: printed and sold by A. Soulby; also by R. Middleton, Hull, 1797) [ESTC T74313].

28 C. W. Chilton, Early Hull Printers and Booksellers: An Account of the Printing, Bookselling and Allied Trades, from their Beginning to 1840 (Hull: Kingston-upon-Hull City Council, 1982). (See also ESTC T210928.)

29 G. Thompson, A Sentimental Tour, Collected from a Variety of Occurrences, from Newbiggin near Penrith, Cumberland, to London (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby, for the author; and sold by Crosby, near Stationer’s Hall, Ludgate Street; Faulder, Bond Street; Anderson, Holborn, London; and the booksellers in general, 1798) [ESTC T97571].

30 Poems, on a Variety of Interesting Subjects, both Moral and Religious; to which are added, Two Poems by the Late Dr. Watts (Alston: printed by and for John Harrop; and sold by A. Soulby, Penrith; Jollie, Carlisle; Charnley, Bell, and Whitfield, Newcastle; Pennington, Durham; Welford, Bishop Auckland; and Heavisides, Darlington, 1800), price 1s. [ESTC T54963].

31 Nigel Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick: The Complete Illustrative Work, 3 vols (London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2011), TB2.517.

32 Isaac Hewetson, Reading Made Easy; or, A Step in the Ladder to Learning (Penrith: printed by A. Soulby; and sold by Crosby and Letterman, Stationer’s Court, Ludgate Hill, London) [ESTC N472761].

33 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, TB2.126.

34 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, TB2.517.

35 The Pleasing Instructor; or, Entertaining Moralist (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby; and sold by Crosby & Co., No. 4, Stationers’ Court, Ludgate Street, London) [London, British Library, RB.23.a.20806.].

36 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, II, 528.

37 Anthony Soulby to Thomas Bewick, 27 March 1805. I am grateful to the late Iain Bain for a transcription of this letter.

38 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, TB2.431.

39 Grasmere, Wordsworth Trust, 2013.57.3.5, Anthony Soulby to Thomas Bewick, 28 March 1808. I am grateful to the late Iain Bain for drawing my attention to this letter and supplying me with a copy of the sketch.

40 Penrith Museum.

41 Thomas Hugo, Bewick’s Woodcuts: Impressions of Upwards of Two Thousand Wood-blocks, Engraved, for the Most Part, by Thomas & John Bewick (London: L. Reeve & Co., 1870), no. 800.

42 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, II, 892.

43 An Excellent Old Song, setting forth the Memorable Battle Fought between Sir Lancelot du Lake and Tarquin the Giant, Who Dwelt at the Giant’s Cave, at Edenside, near Penrith (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby) [ESTC T225026].

44 An Excellent Old Song, setting forth the Memorable Battle Fought between Sir Lancelot du Lake and Tarquin the Giant, Who Dwelt at the Giant’s Cave, at Edenside, near Penrith (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby) [Carlisle Library, Local Studies, PL M176].

45 Book Bag, Catalogue 3 (1995), item 3.

46 The History of Selico (Penrith: printed by Anthony Soulby) [Carlisle Library, Local Studies, PL M176].

47 Selico, an African Tale (Exeter: printed by R. Trewman and Son; and sold by G. and T. Wilkie, Paternoster Row, London; and all other booksellers), price 1s. 6d. [ESTC T182163].

48 London, National Art Library, Forster S 4to 1522.

49 An Account of a Most Surprising Savage Girl (Penrith: A. Soulby, printer) [London, National Art Library, Forster S 4to 1522]. The title is erroneously attributed to John Soulby in John Meriton, with Carlo Dumontet (eds), Small Books for the Common Man: A Descriptive Bibliography (London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2010), p. 675.

50 [R. S.] ‘Chancellor’ Ferguson, ‘On the Collection of Chap-books in the Bibliotheca Jacksoniana, in Tullie House, Carlisle, with Some Remarks on the History of Printing in Carlisle, Whitehaven, Penrith, and Other North Country Towns’, Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archæological Society, 14 (1896), 1–120 (p. 64).

51 Quoted in Victor E. Neuburg, The Penny Histories: A Study of Chapbooks for Young Readers over Two Centuries (London: Oxford University Press, 1968), p. 55.

52 Thomas Kelly, A History of Adult Education in Great Britain, 2nd edn (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1970), p. 6.

53 Treasurer’s Report, List of Subscribers, and List of Tracts at the front of a bound volume of Cheap Repository Tracts containing thirty-three chapbooks. I am grateful to the late Alex Fotheringham for drawing this to my attention.

54 James Mosley (ed.), S. & C. Stephenson, A Specimen of Printing Types & Various Ornaments, 1796 (London: Printing Historical Society, 1990).

55 Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick, II, 888.