7. Slip Songs and Engraved Song Sheets

© 2023 David Stoker, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347.07

The early decades of the eighteenth century have been described as a time when ‘music was rapidly changing in form, substance, and performance. It was becoming much more the concern of everyday folk.’1 Prior to this, music, whether printed by letterpress or using engraved plates, was usually reserved for serious or religious compositions. The Catalogue of All the Musick Books That Have Been Printed in England published by John Playford in 1653 contained ‘no popular songs or dance books, no theatre music’, all of which would become a staple feature of eighteenth-century music publishing.2 Engraved, as opposed to letterpress, printed music had existed in England since the 1580s, but it was only in the mid-seventeenth century that it became at all common and music became an established specialism within the engraver’s trade. Members of the Playford family would continue to publish songbooks that were both engraved and printed by letterpress throughout the second half of the century.3 After 1695, specialist music publishers such as John Walsh and, later, John Cluer began catering for the more popular market with publications that offered individual songs and collections of new songs, or ‘ayers from the stage’, and instruction manuals for playing instruments in a domestic setting.4 However, their engraved musical publications were still beyond the pockets of most of the public.

There was also a market for the publication of the words of both traditional and newly composed popular songs, only occasionally with any indication as to the tune to which they were to be sung. These were sold either collected in songbooks or as individual broadside ballads. A typical seventeenth-century broadside ballad of the type collected by Samuel Pepys would have been printed on a half-sheet of paper, using black-letter type, and might comprise either a contemporary song (or songs) or a traditional ballad. The black-letter ballads began to decline in popularity towards the end of the century, to be replaced by half-sheet white-letter ballads (printed in roman or italic type), and by a new popular printed format, the slip song. The latter remained the principal and cheapest vehicle for disseminating the words of popular songs well into the nineteenth century.

A database of slip songs

Of all the eighteenth-century printed formats, slip songs (sometimes referred to as ‘slip ballads’ or merely ‘slips’) are the most difficult to categorize or deal with from the point of view of bibliographical control. This may explain the lack of research into their format, production, and distribution, compared with chapbooks or traditional broadside ballads. They were cheap, ephemeral publications; only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of titles and editions produced have survived, usually only as a single copy. Only a minority of the surviving exemplars include an imprint which might indicate their date and place of printing, or who was responsible for their production and sale. Where this is given it has sometimes been misinterpreted, because they were usually produced by businesses working on the fringes of the established book trade in London or by poorly documented printers working in the provinces. Likewise, they were sold by a network of pedlars, hawkers, patterers, and ballad singers, or else from market stalls, rather than in retail bookshops.

In order to gain a better understanding of the format, their printers and publishers, and the types of songs produced, the author downloaded 3,830 bibliographical records containing the phrase ‘slip song’ or ‘slip-song’ within the ‘general notes’ field from the more than 480,000 records currently in the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC). Subsequent examination of the records found several of them where the general notes field was referring to another publication, or where there was an obvious error in the description. These were discounted, and the sample was further restricted to items printed in Britain and Ireland. This left a total of 3,806 records which were used to create a database of songs which could be sorted and analysed according to the contents of the different fields.

Before presenting the results of this exercise, a more than usually strong health warning needs to be issued about the reliability of the conclusions that can be drawn from such data. ESTC is a large and detailed bibliographical source, which records the collections of many libraries and repositories throughout the world, but it is a union catalogue and cannot be assumed to be entirely consistent in its use of terminology.5 Furthermore, the records of items that happen to have survived in libraries are not necessarily representative of the output of contemporary presses. To give one of many possible examples, 222 slip songs were printed in or assigned to the city of Salisbury, which would appear to make this the most important centre for such publications outside of London. However, 214 of these came from one little-known printer, John Fowler, who only operated within the city for a few years during the late 1780s before moving to London. The large number of entries are due to the preservation of three scrapbooks of his publications in the British Library.6 Thus, chance survivals can skew the results. Nevertheless, ESTC is the best tool available and some interesting results are forthcoming from an analysis of its contents.

Definition, format, illustration, and price

The use of the word ‘slip’ to refer to a narrow piece of paper was current in the seventeenth century, and proofs of printed books on long sheets were often referred to as ‘slips’. The term ‘slip song’ appears to be a more recent coinage, which occurs frequently in twentieth-century literature but without any clear definition in terms of bibliographical format. The main distinguishing features of these publications are:

- content — a song or lyric of some kind

- shape — usually, but not universally, long and narrow

- format — printed on one side of a half-sheet of paper or smaller.

Leslie Shepard does not include an entry in his glossary of street literature terms, although under ‘ballad’ he defines a ‘slip ballad’ or ‘single slip’ as ‘a single column ballad sheet, usually cut from a double column sheet’.7 The Oxford Companion to the Book describes ‘slip song’ in terms of its shape and what it does not contain:

Texts customarily printed on long narrow slips of paper. Music was hardly ever printed together with the words in this format; on the rare occasions when it is to be found it is usually as a decorative pretence, devoid of genuine musical significance. At best, such notations served as an aide-memoire for the reader, who would then select a suitable melody from a corpus of simple tunes known principally from oral tradition.8

Another recent definition is ‘a song printed on a single sheet or “slip” of paper’, although this does not differentiate slip songs from the broadside ballad format.9

Slip songs are a type of broadside ballad, in so far as they were printed on one side of the paper, and some musicologists and folk song scholars have used the terms interchangeably.10 Yet the book trade regarded them as separate types of publication, at least during the eighteenth century (Fig. 7.1). Both the William and Cluer Dicey catalogue and the Dicey and Marshall catalogue treat ‘old ballads’ and ‘slips’ as separate categories. They were almost universally printed using letterpress during the greater part of the eighteenth century, although during the 1770s and 1780s a new category of engraved and etched song sheet gradually began to be introduced, perhaps aiming for a more prosperous market. Apart from a few exceptions, these are not included in ESTC, and elsewhere they are usually described as ‘song-sheets’. This format does not, therefore, feature in the following analyses, but is discussed separately at the end of the chapter.

Fig. 7.1. The Bonny Broom (Lynn: printed and sold at Garratt’s Printing Office, [between 1762 and 1797]). Five editions of this song are listed in ESTC, but not this one. Courtesy Lewis Walpole Library.

Determining the format of these songs has proved problematic. The subject is complex and in the absence of clear cataloguing rules different libraries appear to have adopted different practices. Surviving copies have often been trimmed, so it is not possible to determine their original dimensions. The traditional method of determining format is to examine the direction of the chain lines. If printed four to a sheet, the chain lines would normally be vertical in relation to the text, whereas with eight to a sheet they would be horizontal. Yet recent research suggests that chain lines do not provide an infallible means of determining format, especially in the eighteenth century and among printers of street literature, where double-sized sheets of paper, cut in half, might have been used.11

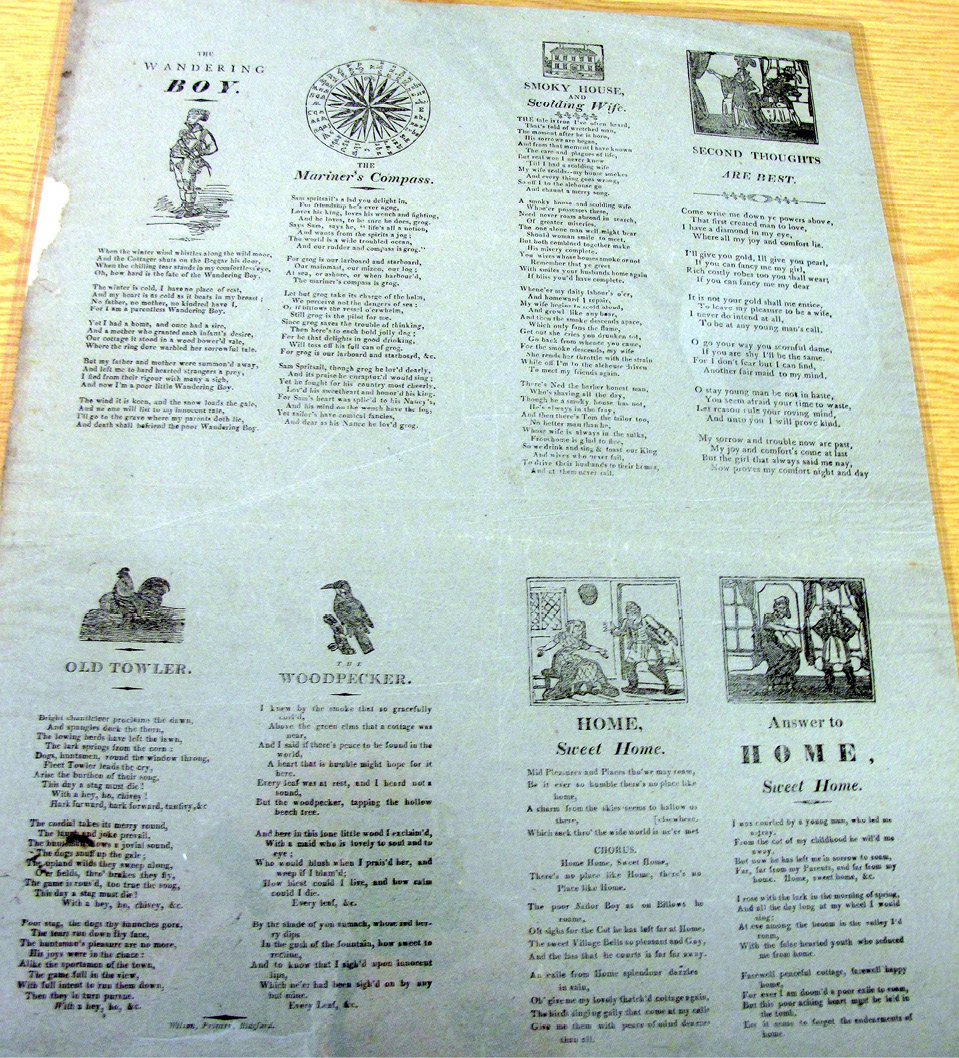

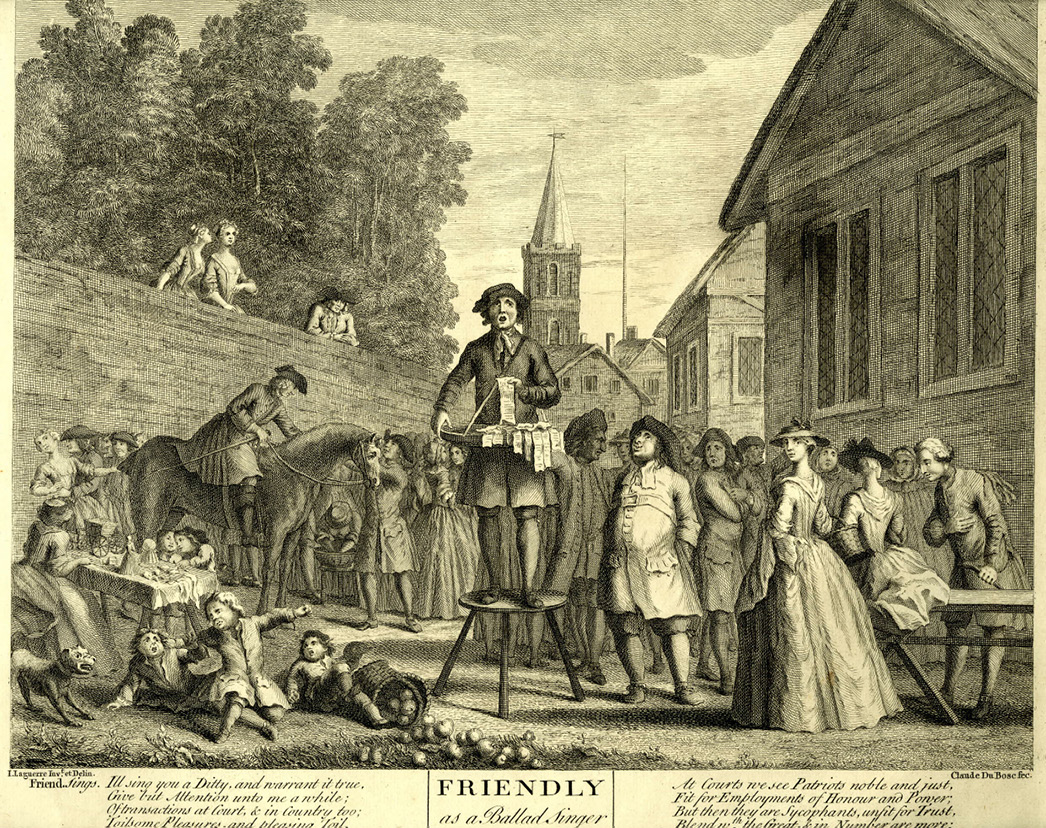

In the author’s experience, a typical slip song would be around 8–10 cm in width and 25–30 cm in length, which would allow for eight single-column songs to be printed on a sheet of paper, therefore giving a format of 1/8o. This impression is confirmed by a search of the JISC Historical Texts database, which includes 1,399 examples with images.12 There are also several examples of uncut sheets of songs in the Bodleian Library that have either eight songs to a sheet or four to a half-sheet (Fig. 7.2).13 However, this is not borne out by the analysis of ESTC entries, where 2,822 (74 per cent) of the records are shown as 1/4o, compared with only 650 (17 per cent) as 1/8o. Shepard’s definition — and the survival of numbers of joined pairs on a quarter-sheet of paper (20–25 cm) — imply that, howsoever they may have been printed, slip songs were likely sold wholesale in pairs, leaving it to the ballad seller, or perhaps even the purchaser, to separate the two parts. The etching Friendly as a Ballad Singer at the Country Wake (c.1745) and the mezzotints The Old Ballad Singer (1775) and The Pretty Maid Buying a Love Song (1780) all clearly illustrate the sale of individual slip songs (Figs 7.3 and 7.4).14 There are substantial numbers of unseparated pairs in ESTC (where they are often recorded in the ‘copy notes’ field).15 The practice of selling songs in pairs may have become more prevalent with printers such as John Pitts and James Catnach at the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth.16 Sometimes a single imprint is given between the two columns, sometimes each column has a separate imprint, but more often there is no imprint.

Fig. 7.2. Eight early nineteenth-century slip songs on a single sheet. Bodleian Library, Firth b.26(467/468).

Fig. 7.3. Friendly as a Ballad Singer at the Country Wake (c.1745), etching and engraving. British Museum 1890,0415.335. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Claude_Du_Bosc_afer_John_Laguerre,_Friendly_as_a_Ballad_Singer_at_the_Country_Wake,_British_Museum_1890,0415.335.jpg.

Fig. 7.4. The Old Ballad Singer (Carington Bowles, 1775), mezzotint. Courtesy Lewis Walpole Library.

More than 91 per cent of the songs are either 1/8o or 1/4o and printed in a single column on one side of the paper, but this still leaves a significant number of exceptions. Items listed with a format of 1o were ruled out, but there remain 222 examples listed with a format of 1/2o, presumably because of the dimensions and direction of the chain lines. A half-sheet, printed in landscape orientation, was the format most commonly used for broadside ballads during the eighteenth century, but there was evidently some overlap with slip songs. For the purposes of this exercise, broadside ballads are regarded as being on a half-sheet or larger, normally printed in two or more columns, whereas a slip song would be on a half-sheet or smaller, printed in a single column.17

There are also a few songs printed in double columns on quarter-sheets which are described as slip songs, but the proportion of these cannot be ascertained from bibliographical entries. However, there are plenty of contemporary songs with the same dimensions, but which are described only as broadside poems. For example, A New Song, to an Old Tune and The Tree of Liberty, a New Song are two very similar-looking songs — each printed in two columns, without imprint, but dating from the 1790s and calling for political reform — of which the former, but not the latter, is recorded as a slip song.18

Another deviation from the norm is those songs that satisfy the other criteria in terms of their shape and a single column, but that were printed on both sides of the paper. There were only seven of these, five of them dating from the first half of the century. One such is Mr. Paul’s Speech Turn’d into Verse.19 Why they should have been printed in this way is not clear. Finally, there are two examples where three songs written by the radical orator and writer John Thelwall survive on a single sheet, clearly intended to be separated, giving a format of 1/3o.20 There are also 106 examples (3 per cent) with small formats such as 1/12o, and even two examples at 1/16o.21

One (occasionally two) crude woodcut illustrations are found on 2,358 (62 per cent) of the titles. In most of these cases, a generic and only vaguely relevant cut that the printer happened to have in stock was used. For example, The Token, one of Charles Dibdin’s sea songs, was illustrated with a cracked woodcut representation of Noah’s ark and the dove returning with a twig, which had been cut for chapbook version of the story.22 Other woodcuts appear with several songs or in known chapbooks, and are sometimes the only means of identifying the producer of a given title. Only six examples in the database record a price — three at 1d. and three at ½d. The 1764 Dicey/Marshall catalogue quotes a wholesale price for slips of 4s. (48d.) per ream of twenty quires (a ream being forty-eight sheets) — that is, twenty copies for 1d.

Subject, content, and date

A typical slip song usually consisted of the words of a contemporary popular song, whether from theatrical performances or sung at pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall and Ranelagh. It might also be used for other purposes, such as political campaigns or sensational accounts of crimes or disasters (Fig. 7.5). Songs and ballads were one of the oldest means of political expression available to the poor, and several slip songs from the 1790s advocated liberty and constitutional reform. The Genius of Liberty, sung to the tune of ‘Rule, Britannia!’, was sold at ‘the Tree of Liberty’ in London’s Soho.23 No doubt Hannah More was thinking of such items when in 1795 she spoke of ‘corrupt and vicious little books and ballads which have been hung out of windows in the most alluring forms or hawked through town and country’.24 There were no hard and fast rules as to their content, which might include both happy and sad love songs, songs relating to country or city life, patter songs, songs to dance to, humorous or satirical songs, songs in support of election candidates or seeking political reform, and at times traditional ballads and folk songs (although these were more often produced as broadside ballads). Sometimes one song was written in ‘answer to’ or as a ‘sequel to’ another famous title.25

Fig. 7.5. Song: The Independent Electors of Middlesex. The names of Byng and Burdett date this to the 1802 parliamentary election. Courtesy Lewis Walpole Library.

Slip songs were not the only format in which contemporary popular songs were distributed. Publishers of street literature such as the Dicey family (1730s–60s), the Marshall family (1770s–90s), or Joshua Davenport and John Evans (1790s–1800s) all produced collections of popular songs in eight-page chapbook format. The Dicey/Marshall catalogue of 1764 refers to them as ‘collections’; other sources call them ‘songsters’, as they were often named after singing birds. With each new edition of a given title new songs would be inserted.26 A single song might therefore be published in several different formats throughout the course of the century.27 Likewise, the same song might be published by two competing printers in the same town. O(h) Dear! What Will Become of Me? was printed as a slip song by John Marshall at No. 42, Long Lane, but was also printed and published by his rival John Evans, next door at No. 41.28

In the early ESTC entries no subject information was recorded, merely a limited number of genres applied to single-sheet publications.29 The number of possible genres has grown since then and subject fields have been introduced. The overwhelming majority of the slip songs in ESTC (3,739, or more than 98 per cent) have been allocated to the ‘broadside poems’ genre, but 523 of these also have a second genre such as ‘songs’ (409), ‘poems’ (seventy-eight), ‘ballads’ (twenty-four), ‘hymns’ (four), ‘dialogues’ (two), ‘plays’ (two), or ‘musical works’ (two). Of the sixty-four entries that are not allocated to the ‘broadside poems’ genre, twelve have no description, forty-seven are designated ‘songs’, two each are ‘poems’ or ‘satires’, and one ‘song-sheets’. One slip song, Dr. Wests Advice to his Patients, is designated as an ‘advertisement’, and another, A True and Particular Account of One John Green, has been placed in the genre of ‘almanacs’, although this is likely to be an error.30

The inclusion of three subject fields (‘subject’, ‘corporate subject’, ‘person as subject’) is a relatively recent development. Only one third of the entries analysed contain this information, so comparisons with the overall sample are not possible. In some instances, the subject field merely duplicates information in the genre field, such as ‘songs, English — early works to 1800’, or ‘English poetry — 18th century’. Ninety-six entries have the subject field descriptor ‘Great Britain — politics and government’, sixty-nine of which also include the descriptor ‘anecdotes’. Other recurring subjects for songs are ‘parliamentary and local elections’, ‘French Revolution’, ‘Jacobites and the Jacobite Rebellion’, and ‘political satire’. More than a hundred entries have the corporate subject descriptor ‘Great Britain — Parliament’. Similarly, the majority of entries with a person as subject contain the names of political figures, especially those standing for election.

Any discussion of the dates of slip songs must be extremely tentative given the lack of information included on them. Only ninety (2.4 per cent) of the 3,820 entries analysed carry a date of publication. Of these, seventy-seven are dated 1794 and also include the month of publication. This was probably the result of a legal dispute then taking place between two neighbouring printers in London (see below). A few others carry statements that may indicate a date, such as ‘printed in the first year of the downfal [sic] of Fox’ — that is, 1784.31 Some songs can be dated with reasonable accuracy from the dates of theatrical productions from which they were taken, the dates of the events portrayed, or, in some cases, the dates of associated material.

There is not always consistency in the way that ascribed dates are shown. In two examples, the date is shown as ‘17—?’, and in three others the date range ‘1700–1800’ has been allocated, presumably for want of any more precise information.32 Others have been given purely speculative dates such as ‘1800?’ based on nothing more than the layout and typography of the item. Where a printer or publisher is named, the date range given often corresponds to their known period of working. Thus, sixty-two items in the Harding collection at the Bodleian Library printed in Newcastle upon Tyne with an ‘Angus, printer’ imprint are allocated to the period 1774–1825.33 About half of them should presumably fall outside the scope of ESTC, but there is no obvious way of telling which ones. Slip songs continued to be printed for many decades into the nineteenth century, but their printers tended to hold on to printing types and retained antiquated features such as the long ‘s’ well after they had been abandoned by those working in the established book trade.

The earliest slip song recorded in ESTC is a song with the opening lines ‘By the merry Landes date ah, / There Dwelt a jolly Miller’, preserved among the Roxburghe Ballads, which carries no imprint.34 This has been ascribed to ‘ca. 1635?’, and is very much an outlier, printed in a black-letter type. There appear to be no other survivors before the mid-1690s, so it has been discounted. There are three further undated titles ascribed to the 1690s, but only one of them appears at all certain, since it concerns the death of Queen Mary on 28 December 1694.35 It is only from 1701 onwards that there is any firmer evidence to assist in dating.

Using actual or ascribed dates, or else the initial date given when there is a date range, a crude measure of the numbers surviving from each decade can be obtained. Between 1701 and 1760, this figure fluctuated between forty-one and 144 titles each year, and the slip song seems to have been a relatively minor format or genre. After 1770, there was rapid growth in the numbers of slip songs being produced (or at least surviving), with 644 titles from 1771–80, 1,011 from 1781–90, and 1,476 for the period 1791–1800. The increase may be partly due to the growth in printed matter generally, or to the spread of printing to towns and cities in the provinces. There may also be reasons associated with the genre, such as the growth in popularity of theatrical and musical performances and the opening of more pleasure gardens towards the end of the century.

Authorship and performance

Only 196 (5.2 per cent) of the 3,806 slip songs in ESTC carry any direct indication of their authorship, with phrases such as ‘words by’, ‘written by’, or ‘composed by’ included in the subtitle. Of these, forty-two contain initials, incomplete names, descriptors such as ‘a Lady’, or obvious pseudonyms such as ‘Oliver Oddfish’.36 On occasion, ballad singers used colourful language to attract attention to their wares, such as the New Song, Warbled out of the Oracular Oven of Tho. Baker.37

Only twelve examples gave any indication of specific responsibility for the music. The Beer-Drinking Britons is described as ‘Set by Mr. Arne, and sung by Mr. Beard’, although there is no indication that the words were written by Henry Woodward.38 The twenty-three examples with the phrase ‘composed by’ may indicate that both words and music were written by the author. An indication of the tune to which the song was to be sung is given in 551 instances (14.4 per cent). These were often well-known tunes of the time, many of which are still popular in the present century, such as ‘Rambling Boy’, ‘The Vicar of Bray’, ‘O Dear, What Can the Matter Be?’, and ‘The Roast Beef of Old England’.

A further 174 examples name the singer who had introduced the song, or the theatrical production in which it was introduced, twenty-eight of which also identify the author of the words. This was often the case if the performer or production were well known. Two examples are Jacky Bull from France, Sung by Mr. Wilson, in The Agreeable Surprize and The Rosy Dawn, Sung by Mrs. Wrighten, at Vauxhall.39 In a few instances a song might be written and printed for a political occasion, such as Oppression’s Defeat, a Song, Sung at a Meeting of the Surry-Street Division of the Friends of the People, Written by a Member, which is signed at foot ‘T. N.’.40 Others may have been suppositious, written on behalf of the supposed author, such as The Lamentation of Rebecca Downing, Condemn’d to Be Burnt at Heavitree, near Exeter, on Monday, July 29, 1782, for Poisoning her Master, Richard Jarvis.41 Using the above-mentioned clues, musicologists and library cataloguers have assigned authors or pseudonyms to 543 (over 14 per cent) of the slip songs in the database. The authorship of the remainder is unknown.

By far the most prolific songwriter recorded in the database is the composer, musician, dramatist, novelist, and actor Charles Dibdin the Elder (c.1745–1814), who composed popular songs for the theatre and many songs associated with the navy, such as ‘Tom Bowling’. He was responsible for 112 entries, although he is reputed to have composed more than six hundred songs during his career (the latter part of which falls outside the scope of ESTC). Other prolific songwriters include the composer and organist James Hook (1746–1827) with thirty entries, and the writer and actor John O’Keeffe (1747–1833) with twenty-three. The title of one of O’Keeffe’s songs, printed by Fowler in Salisbury, took up almost as much space as the two stanzas of the song:

Sir Gregory Gigg;

or, the

City Beau.

A Favourite Song, in The Son in Law.

Sung by Mr. Mills, in the Character of

Bouquet, at the Salisbury Theatre.

Tune – Young Jockey stole my Heart away.42

Language, country, and place of publication

All but seven of the 3,820 surviving slip songs were in the English language — if one discounts the two editions of A Speech Deliver’d by the High-German Speaking-Dog.43 Two of the exceptions are in Latin with English translations, printed by Fowler in Salisbury, apparently for the use of Winchester College.44 The remaining five are in French and date from the immediate post-revolutionary period; none of them have any form of imprint, but they are assumed to have been printed in London, presumably because of their content or the collection with which they are associated. Four of them are in the same bound volume in the British Library and are provisionally dated ‘1790?’.45 The fifth is a version of the famous French burlesque song Chanton de Malbrouk, among the Madden Ballads at Cambridge University Library, with the ascribed imprint ‘London? 1795?’.46

The slip song format, as represented in ESTC, also appears to be overwhelmingly English, with 3,725 entries printed (or ascribed to presses) in England. This represents almost 98 per cent of the slip songs from the Britain and Ireland. Fifty-six entries are from Scotland, twenty-six from Ireland, and there are no examples from Wales.47 In two of the Scottish cases there is clearly a mistake in the record because the imprints are from known English printers.48 All but one of the remaining Scottish entries have no imprint and have been ascribed to presses in Edinburgh (forty-eight items), Glasgow (five items), and Aberdeen (one item) on the basis of their content or associated material. In only one instance can a Scottish slip song be confidently ascribed to a local printer — Jervis Taking the Spanish Fleet, with the imprint of C. McLachlan, printer, Dumfries, which can be dated to 1797 from the events described.49 Yet there is little doubt that slip songs were regularly ‘sold at the fairs and markets of central Scotland’ during the eighteenth century.50 Five of the Irish items are identified as having been printed in Dublin or else have the imprint of a known Dublin printer; the remainder have no imprint, but nineteen have been ascribed to Dublin and one each to Belfast and Downpatrick.

Of the entries from England, 3,106 (83 per cent) were either printed in London or else attributed to printers there. Yet only 113 of these specifically say so, although a further 403 entries contain addresses that are either within the city or in its immediate vicinity (notably Smithfield, Holborn, Clerkenwell, Seven Dials, and Westminster), or else that contain the name of a printer or publisher known to have been operating there. Until July 1799 there was no legal requirement for printers to identify their publications, but publishers — especially in London — often did so during the 1780s and 1790 as a means of letting customers know where to obtain supplies. The most common addresses found on ESTC slip songs are associated with well-known printers: No. 41, Long Lane, East Smithfield (John Evans, 210 examples); No. 42, Long Lane (John Marshall and John Evans, 159 examples); No. 6, George’s Court, St John’s Lane, West Smithfield (Joshua Davenport, sixty-six examples). However, the overwhelming majority were produced without imprint and a further 2,582 items are ascribed to unnamed London printers.

An analysis of songs from English towns and cities outside of London is also problematic. The results for the three towns with largest number of surviving entries are all skewed by chance survivals. Mention has already been made of the 214 Fowler songs out of a total of 222 from Salisbury, and the sixty-two Angus survivals out of a total of 146 from Newcastle upon Tyne. There are also eighty-eight songs with no imprint in the Bodleian Library that have been attributed to an unnamed press in Coventry with ascribed dates of 1768–90.51 One of these is annotated in manuscript ‘Richard Bird Printer & Composer 1780’.52

Fifty English provincial towns are represented, but in many instances the publication is ascribed to an unknown printer operating there. Thirty-two examples survive from the emerging manufacturing centre of Manchester; almost all have imprints that date them to the last decade of the century. These are also largely contained in three volumes in the Harding collection in the Bodleian Library.53 Other rapidly growing towns during the last quarter of the century are less well represented, such as Birmingham (ten items), Liverpool (three items), and Leeds (no items). There are surprisingly few examples from established eighteenth-century provincial printing centres such as Bristol (two certain and one possible items), Norwich (three likely and four possible items), and York (two possible items). Each of these cities had several successful theatrical and concert venues and active presses throughout the century, several of which specialized in ephemeral publications. As with all types of ephemeral literature, it is likely that the majority of productions have been lost.

Printers and publishers

Only 612 (16 per cent) of the slip songs in ESTC include the name of a printer or publisher/distributor in an imprint. In most of these cases the same business was serving both functions. In a further 197 instances there is an address but no name given in the imprint. Thus, responsibility for production and/or distribution can be ascertained for only one song in five. The name that appears most frequently (214 imprints) is John Fowler of Salisbury. He appears to have operated a business specializing in such songs between 1785 and 1788, and created his own unique format for them, as he explained in his advertisement:

Of J. Fowler, Printer, In Silver-street, Salisbury, A very Capital Collection Of the most Approved Songs, Duets, Trios, &c. Ancient, as well as Modern; Many of which are not to be purchased at any other Shop in the Kingdom: and For Correctness, and Elegance, exceed every thing of the Kind yet published. The Songs, &c. are neatly printed in the Size of a large Card, on Writing Paper, with Borders of Flowers. The Printer hereof being the Original and only Publisher of them.54

Fowler’s productions were not typical slip songs in that they usually had a decorative border of flowers, no woodcut illustrations, and were occasionally printed in two columns. Other provincial printers named in the imprints of six or more slip songs are Angus of Newcastle upon Tyne (sixty-three items), Shelmerdine of Manchester (eighteen items), Burbage and Stretton of Nottingham, Jennings of Sheffield, Smith of Lincoln, and Swindells of Manchester (seven items each), and Wrighton of Birmingham (six items), but these follow the usual single-column pattern.

The imprints from the London trade are probably more typical, but often list the distributor (‘sold by’) as opposed to the printer (‘printed by’), although in many instances both functions were carried out by the same person. London imprints are also more likely to give just a distribution address without a name. For example, 120 imprints have the name John Evans or J. Evans & Co. (seventy-eight ‘sold by’, twenty-seven ‘printed by’, and fifteen ‘printed and sold by’). A further 154 items have the addresses No. 41 or No. 42, Long Lane, West Smithfield, which are associated with John Evans. He began his career working for Richard Marshall of Aldermary Churchyard, and in 1783 was appointed as manager of John Marshall’s wholesale shop at No. 42, Long Lane, which after 1787 was operated in Evans’s name, although still funded and supplied by Marshall. Following a dispute with his employer in March 1793, Evans moved next door to No. 41, Long Lane, where he set up a press in opposition to Marshall. The dispute was eventually resolved in December 1795. However, during the period of the dispute many slip songs with the imprint ‘Sold at No. 42, Long Lane’ also carry dates of publication as a way of differentiating them from those printed and published by Evans next door.55

The name of Joshua Davenport, also from West Smithfield, is found in 118 imprints (twenty-two ‘printed by’ and ninety-six ‘printed and sold by’). As with the productions of the Angus family in Newcastle, it is likely that a high proportion of these post-date 1800, especially since sixty-four of them have an address that he occupied between 1800 and 1808.56 The vicinity of Smithfield, on the outskirts of the City of London, was an important area for the production of street literature, associated with ballad printers and publishers since the seventeenth century.57 Two others identify the printer there as J. Thompson.58 Five slip songs were printed for the radical bookseller Thomas Spence, whose imprints describe his address at No. 8, Little Turnstile, Holborn, as ‘the Hive of Liberty’ and himself as a ‘patriotic bookseller and publisher of Pig’s Meat’.59

The most prolific printer and publisher of slip songs during the eighteenth century barely features in the ESTC database, because they hardly ever included an imprint on these publications. This was the Dicey/Marshall publishing enterprise, which operated from premises in Bow Churchyard between 1736 and 1763, and in Aldermary Churchyard between 1753 and 1806.60 The catalogue issued by William and Cluer Dicey in 1754 spoke of ‘near two thousand different sorts of slips; of which the new Sorts coming out almost daily render it impossible to make a Complete Catalogue’. That number had risen to ‘near three thousand’ in 1764 when Cluer Dicey and Richard Marshall produced their catalogue. There are two references to Bow Churchyard among the slip songs in ESTC, but both are actually half-sheet broadside ballads printed in four or five columns, and so have been discounted.61 There is only one reference to Aldermary Churchyard in the database, for The Blue Bell of Scotland printed by John Marshall between 1793 and 1800, with words adapted to take account of the war with France.62 Were it not for the records of the two Chancery suits brought by John Marshall against John Evans in 1793 and 1794, little would be known of Marshall’s activities in this area, or that he was the proprietor of the business at No. 42, Long Lane between 1783 and 1796.

Many surviving Dicey/Marshall slip songs without imprints can be identified because the woodcuts used correspond with others of their productions. For example, the song Ground Ivy uses the same woodcut of a woman carrying a staff as the chapbook history The Whole Life and Death of Long Meg of Westminster, which has an Aldermary Churchyard imprint.63 Likewise, the song Country Toby uses the woodcut of an old man with a rake that is used with The Arraigning and Indicting of Sir John Barleycorn, which survives in chapbook editions with Bow Churchyard, Aldermary Churchyard, and ‘printed and sold in London’ imprints.64 The crude woodcut of a woman sitting in front of curtains that appears with The Blue Bell of Scotland also appears with several other contemporary slip songs, including The Bonny Lass of Aberdeen.65 The work of Giles Bergel and others using ImageMatch software will no doubt lead to further identifications.66

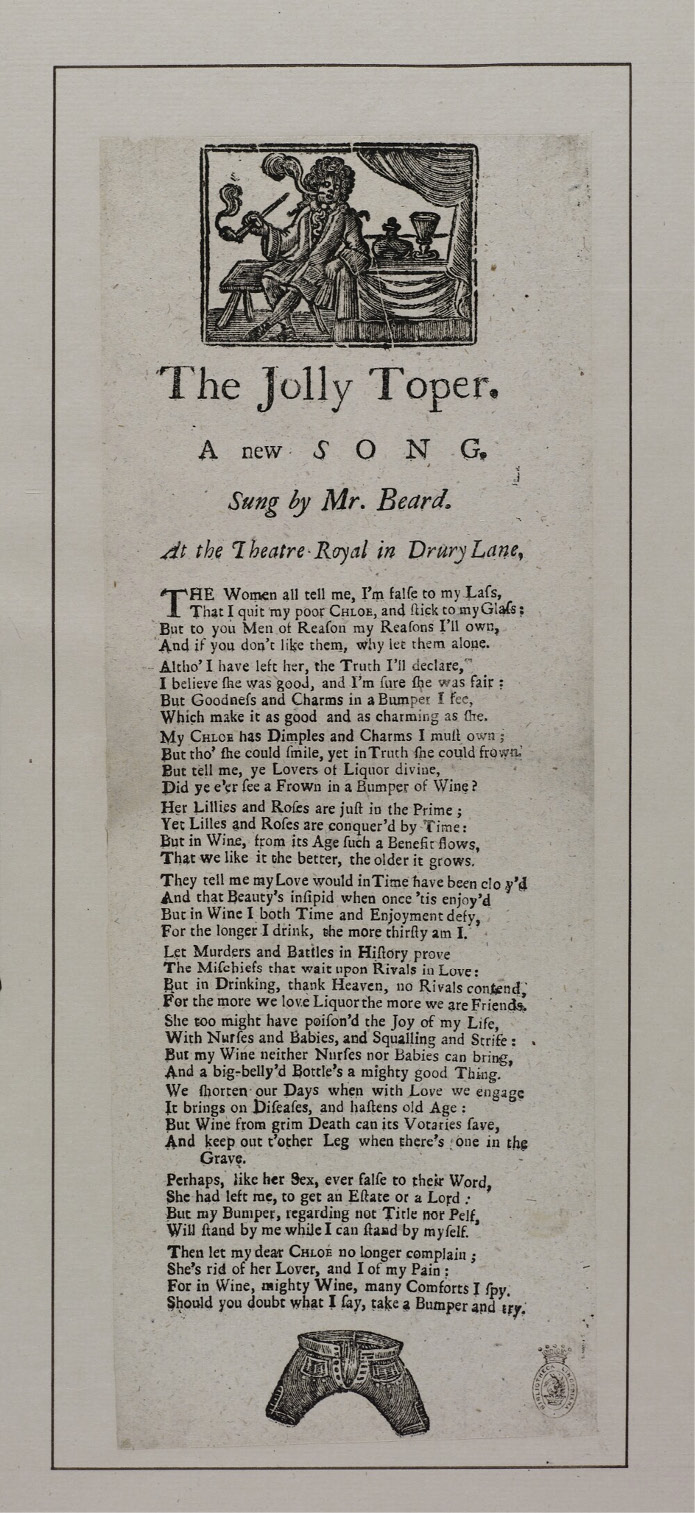

Fig. 7.6. The Jolly Toper (c.1770). The woodcut of the man smoking a pipe appears on at least six Dicey/Marshall broadside ballads. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland through the Creative Commons 4.0 International Licence.

Locations and collectors of slip songs

The last fields of an ESTC record indicate the locations and shelfmarks (where known) of recorded copies of each edition. The analysis of these indicated that there are 4,930 copies recorded in seventy-five repositories in Britain and Ireland, mainland Europe, North America, and Australia. That is to say, there is an average of 1.3 copies per title, or the majority of surviving songs exist in a single copy only. Three major British libraries dominate the holdings, with 1,959 items recorded in Cambridge University Library, 1,189 in the British Library, and 1,086 in the Bodleian Library.

The Cambridge songs are virtually all from the collection of ‘16,354 garlands, slips and sheets’, dating from between 1775 and 1850, acquired by Sir Frederic Madden, mostly during the years when he was the Keeper of Printed Books at the British Museum. Following Madden’s death in 1873, this collection was sold to Henry Bradshaw, librarian of Cambridge University, whose executors later sold it to the university. Most of Madden’s eighteenth-century material came from an earlier collector, the mathematician, surveyor, and orientalist Reuben Burrow. This was acquired by Madden in 1835 and his diary for 1837 shows that he also sought out materials from old ballad printers:

called again at Pitts, who had looked out for me 58 dozen, all printed by himself since the year 1790. He used formerly to reside at 14 Gt. St. Andrew St. and has been in business, he says, for 39 years. Pitts told me, he had a large collection of old Ballads by other printers, which he had purchased about 40 years since, and offered to sell them to me; an offer, which of course, I accepted. I paid for the 58 dozen £ 1.9.0. […] He told me he had them chiefly from Wise, in Rosemary Lane and of a man who lived in Tyler St., Clare Market […] before he set up business himself, was apprentice to Marshall in Aldermary Churchyard, the printer of penny histories etc.67

The origins of most of the songs in the Bodleian Library can be readily identified due to the library’s practice of allocating shelfmarks to named collections. Many of these come from well-known collectors such as Charles Harding Firth, (1857–1936), Regius Professor of Modern History (eighty-six items), John Johnson (1882–1956), printer to the University of Oxford (fifty-seven items), Francis Douce (1757–1834), Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum (sixteen items), and Lord George Curzon (1859–1925), Foreign Secretary (ten items relating to Napoleon). By far the most important collection of songs, with 627 items, is that of Walter Harding (1883–1973), who was born in Britain but lived in Chicago and pursued a career as a music hall pianist and cinema organist.68

Most of the slip songs in the British Library cannot be identified from ESTC as coming from known collections, with the single exception of those items that were once part of the Roxburghe Ballads. This collection contained primarily early broadside ballads originally collected by Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford (1661–1724) and later owned by John Ker, 3rd Duke of Roxburghe (1740–1804) who added to the collection. They were purchased by the British Museum in 1845. Two libraries in the USA with substantial collections of slip songs are the New York Public Library (136 items) and Harvard University Libraries (133 items).

Engraved song sheets

During the late 1770s and the 1780s an upmarket version of the letterpress slip songs gained popularity as a new format for the distribution of songs. On these sheets the words of the song were engraved and an appropriate illustration etched or burnished using mezzotint on to a soft metal plate for printing, usually in 1/4o format. The words are usually arranged in two or three columns, and the illustration is larger and more detailed than was possible with a narrow slip song, giving a squarer shape, with dimensions of around 26 × 18 cm.69 The earliest survivors in this format are satirical songs, but by the 1780s they are mostly songs associated with theatrical productions, by Charles Dibdin and others, which may have been sold to theatre- and concert-goers to enable them to sing along with the actors. There are also a few surviving examples of songs celebrating naval or military victories.70 As engravings, the publisher’s name and address and the date of first publication were usually included, in order to obtain the protection of Engraving Copyright Act of 1767. Very few of these have been entered in ESTC, but many examples are preserved in the Bodleian Library and the Museum of London.71

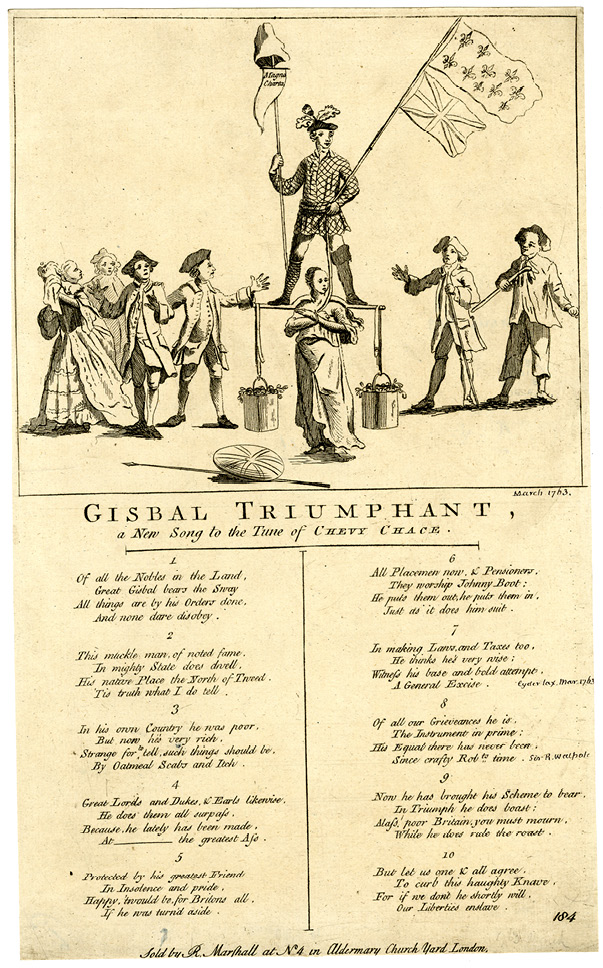

The earliest example known to the author is an undated song satirizing Lord Bute, entitled Gisbal Triumphant, which has the imprint of Richard Marshall at No. 4, Aldermary Churchyard (Fig. 7.7).72 The engraving and etching is dated March 1763, but Richard Marshall was the proprietor of the press between 1770 and his death in 1779. Two further examples of the format, this time satirizing William Pitt’s tax policies, survive in the Bodleian Library with the imprint of E. Rich, No. 55, Fleet Street, dated 1785 and 1787, respectively.73

Fig. 7.7. Gisbal Triumphant (Richard Marshall, c.1770), etching and engraving. British Museum 1868,0808.4290. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gisbal,_Triumphant_(BM_1868,0808.4290).jpg.

There are fifty-two examples of song sheets published by Charles Sheppard, an engraver of No. 19, Lambeth Hill, London, on the Bodleian Library ballads website, dating from 1786 until the early nineteenth century. John Marshall also printed substantial numbers during the 1790s, although only one is included in ESTC.74 In Marshall’s case he could produce the same song in different formats for different markets. Thus The Jolly Ringers, a song by Charles Dibdin from his opera Castles in the Air, was produced as a letterpress slip song in April and May of 1794, and as an engraved song sheet on 9 July 1794.75

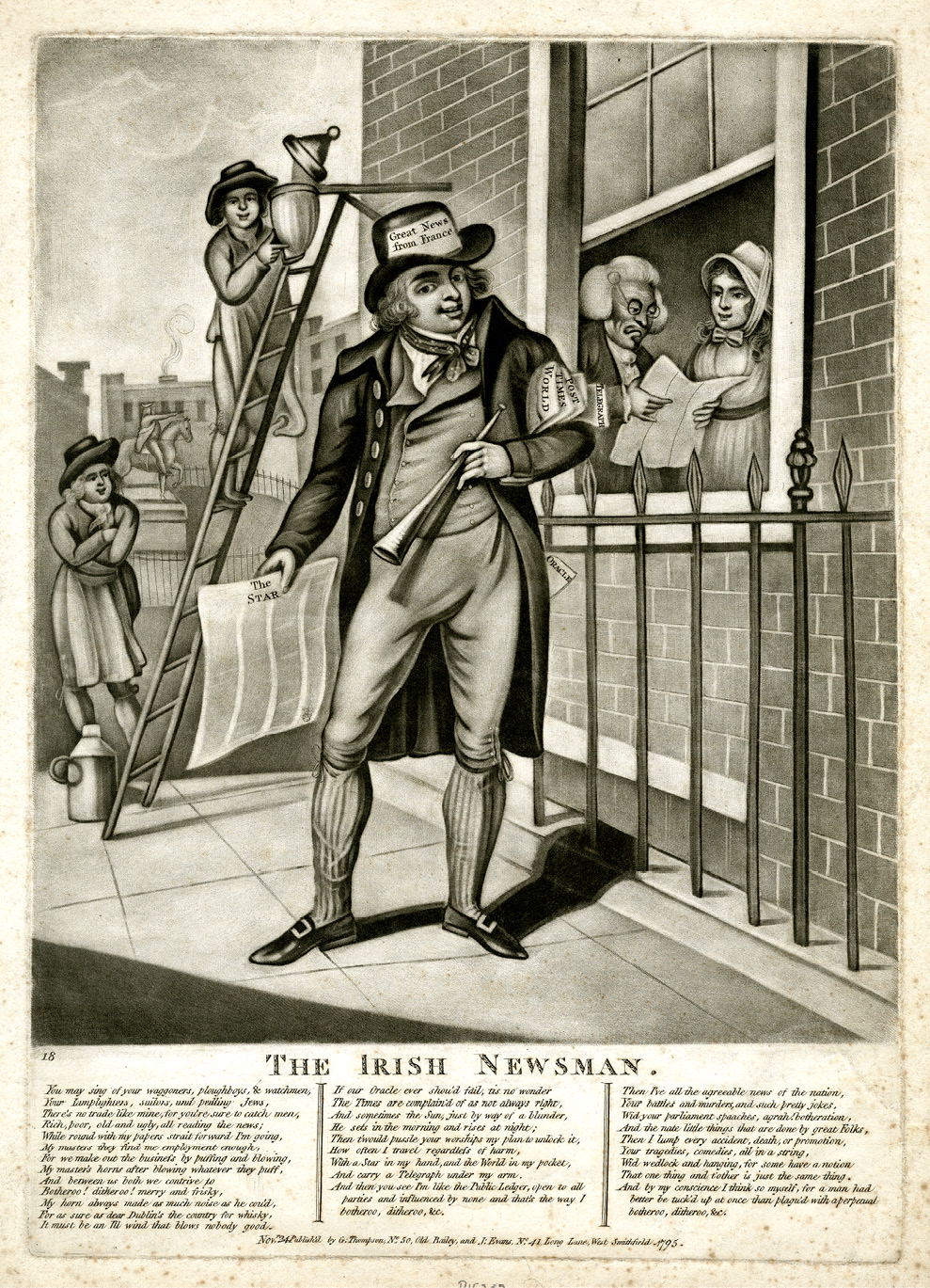

John Evans and his cousin Thomas Evans, of No. 79, Long Lane, Smithfield, also both published in this format. Some of the John Evans titles have dates as far back as 1786 with the address as No. 42, Long Lane. This was a date when, according to Marshall’s testimony in his chancery suit, Evans was still working as manager of the shop and before he was permitted to operate the business in his own name.76 So, either Marshall had allowed his manager a remarkable degree of freedom to publish on his own behalf, or else these items are reprints by Evans of earlier publications that have not survived. John Evans lost his legal battle with John Marshall in September 1795 and was forced to leave the premises at No. 42, Long Lane, West Smithfield, where he had operated under his own name for several years. He promptly moved next door to No. 41 and set up a new business. He also teamed up with another neighbouring publisher of popular prints, George Thompson of No. 50, Old Bailey, and No. 43, Long Lane, to produce the satirical song sheet The Irish Newsman. This time the image was in mezzotint (Fig. 7.8).

After the expiry of his lease on No. 42, Long Lane in April 1796, Marshall gave up the printing ballads and songs in favour of the Cheap Repository Tracts. Soon afterwards, Evans moved back and occupied both the adjacent properties. He would continue a successful business there, producing all kinds of street literature under the imprints of John Evans & Co., Howard and Evans, and John Evans and Son, until his death in 1820.77 Both John and Thomas Evans continued to produce letterpress slip songs and engraved song sheets well into the nineteenth century, and the two formats were also adopted by other key figures in the nineteenth-century street literature trade, including John Pitts and James Catnach.78 Richard Dadd’s watercolour painting of The Ballad Monger shows that these publications were still popular in the 1850s.79

Fig. 7.8. The Irish Newsman (George Thompson and John Evans, 1795), mezzotint. British Museum 2010,7081.1172. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Irish_Newsman_(BM_2010,7081.1172).jpg.

* * *

This essay has been a preliminary foray into an under-researched subject, primarily based on ESTC bibliographical records and electronic surrogates. There are, undoubtedly, many other surviving eighteenth-century slip songs in local libraries, record repositories, and private collections that are not recorded in ESTC, or else lying uncatalogued in libraries that already have substantial recorded collections. There is a real need to identify and record them before beginning to look more closely at the items themselves and how they were published and distributed.

1 William C. Smith, A Bibliography of the Musical Works Published by John Walsh during the Years 1695–1720 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1948), p. vi.

2 Smith, Bibliography of John Walsh, p. v.

3 Cyrus Lawrence Day and Eleanore Boswell Murrie, ‘English Song-Books, 1651–1702, and their Publishers’, The Library, 4th ser., 16 (1936), 355–401.

4 For example: A Collection of New Songs, with a Through Base to Each Song, and a Sonata for Two Flutes (John Walsh, 1697) [Smith no. 13]; A Collection of Ayers, Purposely Contriv’d for Two Flutes (John Walsh, 1698) [Smith no. 18]; Theater Musick, being a Collection of the Newest Ayers for the Violin, with the French Dances Perform’d at Both Theaters (John Walsh, 1698) [Smith no. 19a]; The Harpsicord Master, containing Plain and Easy Instructions for Learners on the Spinet or Harpsicord (John Walsh, 1698) [Smith no. 14].

5 One library describes seven songs printed between 1713 and 1720 on single sheets with dimensions of 44 × 35 cm as slip songs, whereas virtually all other libraries would regard them as broadside ballads (ESTC N66789, N66792, N66796, N66829, N66833, N66834, N66835).

6 London, British Library, 1163.a.19., 11621.i.11., 11622.c.7.

7 Leslie Shepard, The History of Street Literature: The Story of Broadside Ballads, Chapbooks, Proclamations, News-Sheets, Election Bills, Tracts, Pamphlets, Cocks, Catchpennies, and Other Ephemera (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1973), p. 224.

8 Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and H. R. Woudhuysen, The Oxford Companion to the Book (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 1161–62.

9 Kate Horgan, The Politics of Songs in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 1723–1795 (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2014), p. 123.

10 The Roud Broadside Index, for instance, does not differentiate between them and simply records them all as broadsides.

11 For turned chain lines in street literature, see John Meriton, with Carlo Dumontet (eds), Small Books for the Common Man: A Descriptive Bibliography (London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2010), p. 903; and for double-mould paper, see Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press; Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies, 1995 [1972]), pp. 63–65.

12 JISC Historical Texts allows cross-searching of several databases that include images, including Early English Texts Online and Eighteenth Century Collections Online https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/.

13 For example: Oxford, Bodleian Library, Firth b.26(467/468). The imprint, which falls between two of the songs (bottom left in Fig. 7.2), may indicate that they were intended to be sold wholesale either as four quarto pairs, or as a single sheet.

14 London, British Museum, 1890,0415.335, 2010,7081.3072, 1874,1010.22; all reproduced at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection.

15 For example: Pretty Sally, by the Light of the Moon + A New Song, called A Sprig of Shillelah, Sung by Mr. Manly, Theatre, Halifax (printed at Jacobs Office, Halifax) [ESTC T217177, T217178].

16 Leslie Shepard, John Pitts, Ballad Printer of Seven Dials (London: Private Libraries Association, 1969), illustrates an eighteenth-century ‘single slip’ printed by John Marshall (p. 100) and eight early nineteenth-century examples printed by Pitts (pp. 116–19). He also illustrates two unseparated ‘double slips’ printed by Pitts (pp. 120–21).

17 There are a few ESTC slip songs in two columns that have a printed border, giving a wider and shorter size, but these are a minority.

18 A New Song, to an Old Tune — viz. ‘God Save the King’ [ESTC T43008]; The Tree of Liberty, a New Song, Respectfully Addressed to the Swinish Multitude by their Fellow Citizen, William England [ESTC T51671].

19 Mr. Paul’s Speech Turn’d into Verse, and Explain’d for the Use of all Lovers of the Church, and the Late Queen Ann (London: printed in the year 1716), price 1d. [ESTC N4394].

20 John Thelwall, News from Toulon; or, The Men of Gotham’s Expedition + A Sheepsheering Song + Britain’s Glory; or, The Blessings of a Good Constitution [ESTC T43076, T48028, N38440].

21 Because of the uncertainty in determining the format, some more recent additions to ESTC also include the dimensions within the notes field.

22 Charles Dibdin, The Token (sold at No. 42, Long Lane, printed in April 1794) [ESTC T51441].

23 The Genius of Liberty (sold by R. Lee, at the Tree of Liberty, No. 2, St Ann’s Court, Soho) [ESTC T4809]. Other examples of slip songs seeking political reform are: The Tree of Liberty (sold, wholesale and retail, by Citizen T. G. Ballard, No. 3, Bedford Court, Covent Garden) [ESTC T207158]; Thomas Spence, The Rights of Man, First Published in the Year 1783 (printed for T. Spence, bookseller, No. 8, Little Turnstile, Holborn) [ESTC T45086]; Song, Sung at the Anniversary of the Society for Constitutional Information, Held at the Crown-and-Anchor Tavern, London, May 2, 1794 [ESTC N38469].

24 A Plan for Establishing a Repository of Cheap Publications on Religious & Moral Subjects [ESTC T155148]. Hannah More’s ballads were usually published in broadside format, but one example, Dick and Johnny; or, The Last New Drinking Song [ESTC T31834], was published without imprint as a 1/8o slip song.

25 For example: The Answer to The Gown of Green (printed by J. Grundy, Worcester) [ESTC N71051]; The Pipe and Jug, a Sequel to The Brown Jug [ESTC T42313].

26 Dicey/Marshall catalogue (1764), p. 97: ‘N. B. Each Time of Re-printing the above Song-Books, the Songs therein are always changed for New.’

27 Jennifer Batt, ‘ “It ought not to be lost to the world”: The Transmission and Consumption of Eighteenth-Century Lyric Verse’, Review of English Studies, n.s., 62 (2011), 414–32, has traced one lyric poem, ‘The Midsummer Wish’, through at least fifty publications, including slip songs and broadside ballads.

28 O Dear! What Will Become of Me?(sold at No. 42, Long Lane) [ESTC T203635]; Oh Dear! What Will Become of Me? (sold at 41, Long Lane) [ESTC N71507]. Marshall later claimed in the Court of Chancery that Evans had taken copies of all his publications when he left his employ in 1793; Evans agreed that he had printed ‘some few slips and publications’, but denied that any of them ‘were the original designs or inventions of the Plaintiff’. See David Stoker, ‘John Marshall, John Evans, and the Cheap Repository Tracts’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 107 (2013), 81–118.

29 John Bloomberg-Rissman, ‘Searching ESTC on RLIN’, Factotum: Newsletter of the English STC, Occasional Paper, 7 March 1996.

30 Dr. Wests Advice to his Patients [ESTC T199417]; A True nad [sic] Particular Account of One John Green, Who Was Tried, Cast and Condemn’d at Stafford Assizes Last for the Barbarous and Bloody Murder of Ann Estings, his Sweetheart ESTC T176591].

31 The Westminster Election, a Song (London: printed in the first year of the downfal [sic] of Fox) [ESTC T207212].

32 A New Song, called The Cobler of Castlebury [ESTC T490629]; The Distracted Maids Lamentation, [ESTC T483154]; Joan’s Ale Is New [ESTC N71387]; The Maidens Lamentation for the Walking-Taylor [ESTC N71043]; The Mock-Song, Sung by Mr. Roberts at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane [ESTC N71042].

33 Examples are found in several volumes in the Harding collection, notably in Harding B25.

34 By the merry Landes date ah, / There Dwelt a jolly Miller [ESTC S124358].

35 The Court and Kingdoms in Tears; or, The Sorrowful Subjects Lamentation for the Death of Her Majesty Queen Mary [ESTC R217307].

36 For example: The Address, in Answer to the Petition, a New Song, by H. M. — [ESTC T203672]; An Epistle to Sir. Scipio Hill, from Madam Kil — k [ESTC N5914]; Absence, a New Song, Wrote by a Gentleman of Southampton, on a Lady Leaving that Place (Fowler, printer, Salisbury) [ESTC T19008]; Five Compleat Ken Crackers, by Oliver Oddfish, Esqr., a New Song [ESTC T199748].

37 New Song, Warbled out of the Oracular Oven of Tho. Baker, just after the D. of M — gh’s Triumphal Procession thro’ the City of London [ESTC T1643].

38 Henry Woodward, The Beer-Drinking Britons, set by Mr. Arne, and sung by Mr. Beard, at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, in the Pantomime called Mercury-Harlequin [ESTC T197969]. Woodward’s pantomime was first staged at Drury Lane on 27 December 1756.

39 John O’Keeffe, Jacky Bull from France, Sung by Mr. Wilson, in The Agreeable Surprize [ESTC T200276]; James Hook, The Rosy Dawn, Sung by Mrs. Wrighten, at Vauxhall, Set by Mr. Hook [ESTC T45239].

40 T. N., Oppression’s Defeat, a Song, Sung at a Meeting of the Surry-Street Division of the Friends of the People, Written by a Member [ESTC T154871].

41 The Lamentation of Rebecca Downing, Condemn’d to Be Burnt at Heavitree, near Exeter, on Monday, July 29, 1782, for Poisoning her Master, Richard Jarvis (Exon: printed by T. Brice) [ESTC T192847].

42 John O’Keeffe, Sir Gregory Gigg; or, The City Beau (Fowler, printer, Salisbury) [ESTC T48325].

43 A Speech Deliver’d by the High-German Speaking-Dog when He Had Audience at Kensington, Introduced by His Grace the Duke of N-wc---le [ESTC T1659, N66843].

44 Canticum, Sung Annually at Winchester College [ESTC T19900]; A Young Student’s Will, Spoken Extempore to his Friend (Fowler, printer, Salisbury) [ESTC T52898].

45 Adieu cœur moi, allez partir ma chere [ESTC T225641]; Il confessoit trois dames [ESTC T225644]; Je suis sortie de mon pays [ESTC T225645]; La jeune Nanette [ESTC T225639] (London, British Library, Cup.21.g.38/27–30).

46 Chanton de Malbrouk; ou, La mort de Malbrouk [ESTC T198609].

47 There are a few late eighteenth-century Welsh-language slip songs in the J. H. Davies ballad collection in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, although these are not recorded in ESTC: for example, Myfyrdod ar fywyd a marwolaeth [Meditation on Life and Death] (1794), or the satirical song Hanes Dic Sion Dafydd [The Story of Dic Sion Dafyd] (Dolgellau: T. Williams, c.1799).

48 Robert Tannahill, Jessy, the Flow’r o’ Dumblain (Evans, printer, Long Lane, London) [ESTC N71465]; A Sup of Good Whisky (D. Wrighton, printer, Snow Hill, Birmingham) [ESTC N72167].

49 Jervis Taking the Spainsh [sic] Fleet (C. M’Lachlan, printer, Dumfries) [ESTC T197434].

50 Murray Pittock, ‘Scottish Song and the Jacobite Cause’, in The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature, vol. 2, Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918), ed. Susan Manning (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), pp. 105–09 (p. 105).

51 Oxford, Bodleian Library, G.A.Warw. b.1. These are for the most part local political songs associated with the election campaigns of Sampson Gideon Eardley, Baron Eardley, and John Baker Holroyd, Earl of Sheffield.

52 A New Song [ESTC N71407]. The song celebrates John Baker Holroyd’s success in the Coventry parliamentary election of 1780. Another copy of the same song identifies ‘Edward Bird, brasier’ as the writer.

53 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Harding Ballads and Songs, vols 1–3.

54 Of J. Fowler, Printer, in Silver-Street, Salisbury (Fowler, printer, Salisbury) [ESTC T42105]. By 1789 Fowler was in business at No. 21, Newcastle Street, Strand, London, and no longer specializing in songs. He is known until c.1795.

55 For details of Evans’s career and his dispute with Marshall, see Stoker, ‘John Marshall, John Evans, and the Cheap Repository Tracts’.

56 William B. Todd, A Directory of Printers and Others in Allied Trades: London and Vicinity, 1800–1840 (London: Printing Historical Society, 1972), p. 53, shows Davenport located at Nos. 6/7, Little Catherine Street, Strand, 1790–99, and No. 6, George’s Court, St John’s Lane, [West Smithfield], 1800–08.

57 Shepard, John Pitts, p. 39.

58 Pat of Kilkenny (Thompson, typr., No. 21, Upper East Smithfield) [ESTC T196395]; Merry Deverting Song, called The Riddle (printed by J. Thompson, 21, East Smithfield) [ESTC T201883].

59 Charles Morris, A New Irish Song, by Captain Morris (printed for T. Spence, at the Hive of Liberty, No. 8, Little Turnstile) [ESTC T6695]; A Parody, upon the Song of Poor Jack (printed for T. Spence, No. 8, Little Turnstile, Holborn, patriotic bookseller and publisher of Pig’s Meat) [ESTC T224033].

60 David Stoker, ‘Another Look at the Dicey-Marshall Publications, 1736–1806’, The Library, 7th ser., 15 (2014), 111–57. The firm continued in business selling children’s books until the 1830s, but appears to have withdrawn from selling songs and ballads towards the end of the eighteenth century.

61 The Crafty Lover; or, The Lawyer Outwitted (printed and sold at the Printing Office in Bow Churchyard, London) [ESTC T34369]; The Children in the Wood: or, The Norfolk Gentleman’s Last Will and Testament (printed and sold in Bow Churchyard) [ESTC T30582].

62 The Blue Bell of Scotland (printed by J. Marshall, Aldermary Chur[c]hyard, London) [ESTC T22922]. Another slip song is The Christening Little Joey; or, The Devil t [sic] Pay (printed by J. Marshall, London) [ESTC T191602], but does not include the Aldermary Churchyard address.

63 Ground Ivy, a New Song [ESTC T199996]; The Whole Life and Death of Long Meg of Westminster (printed and sold in Aldermary Churchyard, London) [ESTC T52454].

64 Country Toby, a New Song [ESTC T199154]; The Arraigning and Indicting of Sir John Barleycorn, Knt. (printed and sold in Aldermary Churchyard, London) [ESTC T22429].

65 The Bonny Lass of Aberdeen [ESTC T198305].

66 Giles Bergel, et al., ‘Content-Based Image-Recognition on Printed Broadside Ballads: The Bodleian Libraries’ ImageMatch Tool’, paper presented at IFLA WLIC 2013, Singapore http://library.ifla.org/209/1/202-bergel-en.pdf.

67 Robert S. Thomson, ‘Publisher’s Introduction: Madden Ballads from Cambridge University Library’. Madden’s papers concerning his ballad collection are at Cambridge University Library, MS Add.2646, MS Add.2687.

68 W. N. H. Harding, ‘British Song Books and Kindred Subjects’, Book Collector, 11 (1962), 448–59; Karen Attar (ed.), Directory of Rare Book and Special Collections in the UK and Republic of Ireland, 3rd edn (London: Facet Publishing, 2016), pp. 320–21.

69 An example, The Chapter of Kings, published by John Marshall on 17 March 1795, is illustrated in Shepard, John Pitts, p. 99.

70 For example: Admiral Hotham Triumphant (published April 21, 1795, by I. Marshall, No. 4. Aldermary Churchyard, London) [Museum of London, A19358].

71 Museum of London, A19346–A19367.

72 Gisbal Triumphant, a New Song (sold by R. Marshall, at No. 4, in Aldermary Churchyard, London) [London, British Museum, 1868,0808.4290].

73 Mr. Axe and Mr. Tax: The Fame of the Shop; or, Billy’s Desert (published by J. Barrow, Aug. 30, 1785; sold by Parsley, Christ Church, Surry; and by Rich, No. 75, Fleet Street) [Oxford, Bodleian Library, Firth b.22(f. 93)]; The Politic Farmer; or, A Fig for Taxation, a New Song (published as the Act directs, by E. Rich, No. 55, Fleet Street, 1 February 1787) [Oxford, Bodleian Library, Firth b.22(f. 94)].

74 Charles Dibdin, Happy Jerry (published March 11, 1794, by I. Marshall, No. 4, Aldermary Churchyard, London) [ESTC N70727].

75 Charles Dibdin, The Jolly Ringers, Sung by Mr. Dibdin (sold at No. 42, Long Lane, printed in May 1794) [ESTC T200909, T29172]; The Jolly Ringers (published July 9, 1794, by I. Marshall, No. 4, Aldermary Churchyard, London) [Museum of London, A19357].

76 For example: Friend & Pitcher (publish’d June 13, 1786, by I. Evans, No. 42, Long Lane, West Smithfield, London) [Oxford, Bodleian Library, Harding B 12(32)]. This song would be reprinted many times as both a slip song and engraved song sheet over succeeding decades.

77 For Evans’s nineteenth-century career, see David Stoker, ‘The Later Years of the Cheap Repository’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 111 (2017), 317–44.

78 Shepard, John Pitts, chapters 2 and 3.

79 Image available at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1953-0509-2.