8. ‘The Arethusa’: Slip Songs and the Mainstream Canon

© 2023 Oskar Cox Jensen, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347.08

The year 1796 was a minor one at the end of a century that showed no signs of winding down. In China and Russia, new emperors took the throne; in France, a future emperor married his patron’s mistress, Joséphine de Beauharnais, before leaving to bloody the fields of northern Italy. In Britain, Edward Jenner inoculated young James Phipps, his gardener’s son, against smallpox, while (with greater relevance to the present readership) Robert Burns’s adaptation of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ was first published in that year’s edition of James Thompson’s Scots Musical Museum. Meanwhile in London a fourteen-year-old boy called William Brown was getting up to tricks worthy of his twentieth-century namesake:

Being one evening short of money, I hit upon a project to get some; the ballad singers of London were at that time singing with great éclat, the song called the Arethusa; I determined to take advantage of the circumstance, so getting a number of old newspapers, in the evening I took my station at the end of several streets, (having previously cut them into slips resembling songs) I began to sing the above, and so rapid was the sale, (in the dark) that in a quarter of an hour I had sold about forty at a halfpenny each, not considering it safe to remain too long in a place I shifted into the middle of Chancery-Lane, Holborn, where I struck up as usual; when I had sold about twenty more an old gentleman opened a door opposite to me, he had a wig on, held a candle in one hand and a stick in the other, and said to me ‘you scoundrel, if you don’t get you gone directly I’ll have you sent to the watch house’; I bade him good night and departed.1

In this chapter, I want to talk about the slips that William Brown purported to sell. Along with their more elevated counterpart — the single-page musical score — they were perhaps the iconic material innovation of eighteenth-century print-musical culture. As their material, printed dimension has been discussed so admirably by David Stoker in the previous chapter, this chapter will act as a companion piece in which I try to think about the slip songs’ content, origins, and their mediatory place in the wider culture. Far from being bound by the realm of ‘cheap print’, slips were passports between diverse but communicating worlds: street and pleasure garden, public house and theatre, the cheap printers of urban Britain and the conservatoires of Vienna and Italy. Before embarking on that journey, however, I would like to spend some time with William Brown’s anecdote and unpick the implications of his mischievous prank.

The slips that William Brown sold

By the time William Brown had his memoir printed in 1829 he was a village schoolmaster, though still far from respectable. Hailing from rural Devon, the son of a cooper, he moved with his family to London at the age of six and despite a solid working-class education at a day school he was loose on the town by his teens — the time at which, in the mid-1790s, he embarked upon his fondly remembered escapade. Concerned as we are with the history of cheap print in the eighteenth century, there are many things we can take away from the story.

Not least worthy of note — it is, after all, the detail that enables the trick — is the fact that in the dark (remembering that this was before the first gas lamps) one form of cheap print could much resemble another. Brown informs us only that he ‘got’ a ‘number of old newspapers’ — presumably for free (or near enough), the material value of the waste paper as recycling for pulp or kindling being negligible, and its contents being worthless after a few days had passed. This in itself recalls the verdict of a more reputable ballad singer, David Love, that ‘stale’ topical songs could not sell.2 The two media, newspaper and slip, were also alike enough in form — organized in columns of relatively dense text and printed in a modern white-letter font — for a newspaper divided into vertical strips to pass as a series of slip songs. Far from suggesting, however, the outdated idea that the newspaper effectively replaced the ballad, the points of resemblance reinforce an impression of two contemporary forms developing in tandem.

I am less concerned with the materiality of Brown’s sham slips than with what they tell us of both practice and provenance. The first-hand account reinforces the evidence of a wealth of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century images — paintings, prints, woodcuts — all depicting the active ballad singer performing from a slip song, with a further sheaf of slips to hand or in a basket.3 This was the hegemonic format of songs performed in city streets from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards for perhaps a hundred years, until the vastly improved economies of scale afforded by increasingly cheap songsters rendered the slip redundant, and costly even at ½d. While a single slip could contain multiple songs, one below another, the form favoured a single song of a relatively limited number of stanzas, and thus reinforced a coherent identity between the things the audience heard, saw, and bought from a ballad singer. The song in the ear was the song they bought — bought for itself, because it appealed — and though a couple of nineteenth-century accounts point to a singer performing only the early stanzas of a longer song before repeating herself, again there is a supposition in favour of a unity between the complete performance of, say, a four-stanza song to a street audience gathered for no more than three or four minutes, and the object subsequently purchased.

This pushes us towards an eighteenth-century culture based upon the performance of easily marketed works: accessible, relatively short songs combining melodic and textual interest, consumed in the street and memorized for domestic re-performance. This is the act ritualized in the famous poem published in the Weekly Register on 9 January 1731 (and again in most works of ballad scholarship for the past forty years) in which people ‘Gather about, to hear the tune’, make their purchase, and go off ‘Humming it […] Endeavouring to learn the song.’ This practice moves away from an early modern view of ballad culture where the thing that mattered was a long textual narrative unfolded across a succession of stanzas and set to a tune the melody of which (in purely musical terms) was more or less incidental.4 To borrow the words of an unfashionable musicologist, Edward T. Cone, in the case of ‘songs for which the strophic form is prescribed — hymns and ballads, for example […] we hear the music less as a theme with variations than as an unchanging background for the projection of a text, which is the real centre of interest. Indeed […] one hardly hears the music of a hymn [or ballad] at all.’5 As we shall see, this was far from always being the case even in the seventeenth century, while the culture of the eighteenth-century slip song strongly militates against any such model. Instead, it affirms the inherently musical interest of the song — it catches hold of the ear, it entertains, and its tune is sufficiently memorable to be passed on in the space of a short street performance (repeated across only a few stanzas) and is as likely to be a novelty as an old, familiar air. This is a culture with at least as much in common with the twentieth-century pop song as with the medieval or early modern long-form ballad. It might well have been the tune, rather than the topical words, that was the exciting new element in any given performance — and such was certainly the case with ‘The Arethusa’ (see Appendix, p. 216).

‘The Arethusa’ (Roud 12675)

More than a century ago, the origins of ‘The Arethusa’ sparked one of those tedious epistolary controversies in which the great song collectors specialized — in this case between Frank Kidson and William H. Grattan Flood, with Lucy Broadwood eventually weighing in as mediator.6 All parties agreed that the melody of the 1796 ‘Arethusa’, far from being entirely original, was based on a tune from around 1730 known as the ‘Princess Royal’. Kidson attributed this to an anonymous composer at the English (which is to say, Hanoverian) court. Grattan Flood was adamant that the tune could be traced back to the great Irish harpist Turlough O’Carolan (1670–1738), and it must be said that he presented some compelling evidence in his favour, in the shape of a certified O’Carolan composition identical in structure and rhyme scheme, with a remarkably similar melody in the B-section.7 While Broadwood’s attempted reconciliation — ‘As to the birthplace or parentage of the above tunes: who can, who need decide? Certain it is, that two such musical nations as the English and Irish have not inhabited the same islands for centuries without a plentiful exchange of verse and melody’ — has a ring of English complacency, even wilful forgetfulness of the two countries’ power relations, we can still take her point.8 Any objective verdict on the tune’s origin is, to my mind, the least interesting thing about it when compared with the historical processes that took it from first thought to William Brown’s trick.

Before even listening to the song itself we can trace a journey that, though remarkable, was wholly typical of eighteenth-century song, going from trained professional musician to street urchin, from court or countryside to city, in a symbiosis of orality and print. Before making its way on to a slip — ‘The Arethusa’, as Brown implies in his opening sentence, was being sold on slips in 1796 — the tune ‘Princess Royal’ had been through various sheet music editions in English, Irish, and Scottish collections of dance tunes before coming to the attention of William Shield (1748–1829), a noted Northumbrian composer based in London.9 Shield, a songwriter who rather specialized in adapting airs from both North Britain and (via his friend and colleague John O’Keeffe) Ireland, rearranged the tune as ‘The Arethusa’, with words by the playwright Prince Hoare, and it was performed by Charles Incledon, the leading tenor of his day, in the role of Cheerly in their farcical afterpiece Lock and Key, opening at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, on 6 February 1796.10

Covent Garden, one of the two royally sanctioned patent theatres, was prohibitively expensive for a working-class audience. Nor would the masses have had access to the printed music since even single-song scores tended to cost at least 1s. in late eighteenth-century London, besides requiring musical literacy. Yet as Brown makes clear, the song was a huge hit on the London streets, performed ‘with great éclat’ by ordinary ballad singers. As its many entries in the Roud index attest, it certainly got about, in books, songsters, chapbooks, and garlands, enduring well into the twentieth century, by which time it had also been incorporated as the third movement of Sir Henry Wood’s 1905 Fantasia on British Sea Songs, a fixture of the Last Night of the Proms. Most pertinently, it appeared on slips from Bridlington, Carlisle, Durham, Liverpool, London, Newcastle, and Preston. These cheap print editions were, of course, not licensed — they acknowledged neither Shield nor Hoare, neither of whom would have seen a penny from their sale. Yet such publications will have been the means of access for the vast majority of the song’s eventual audience.

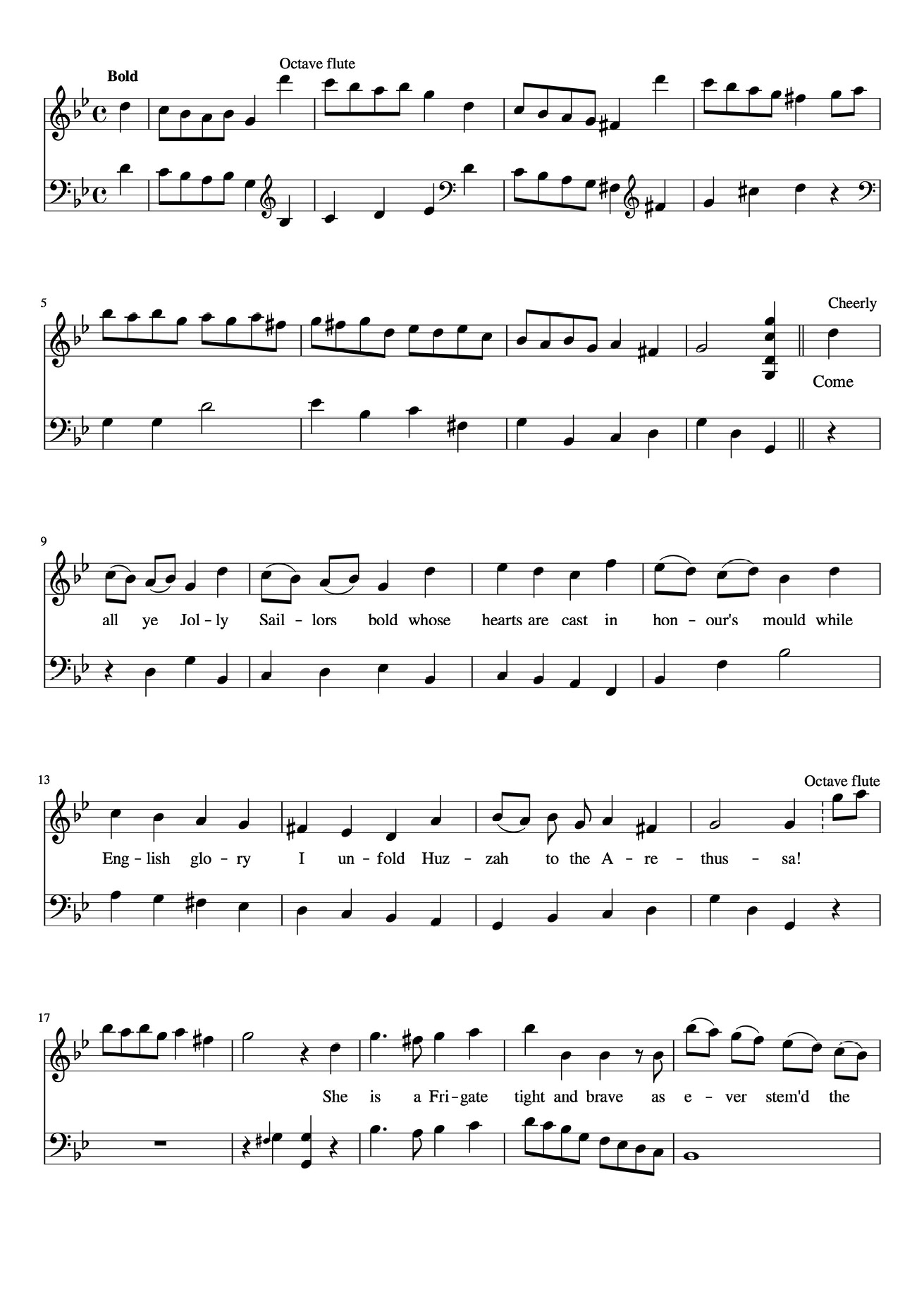

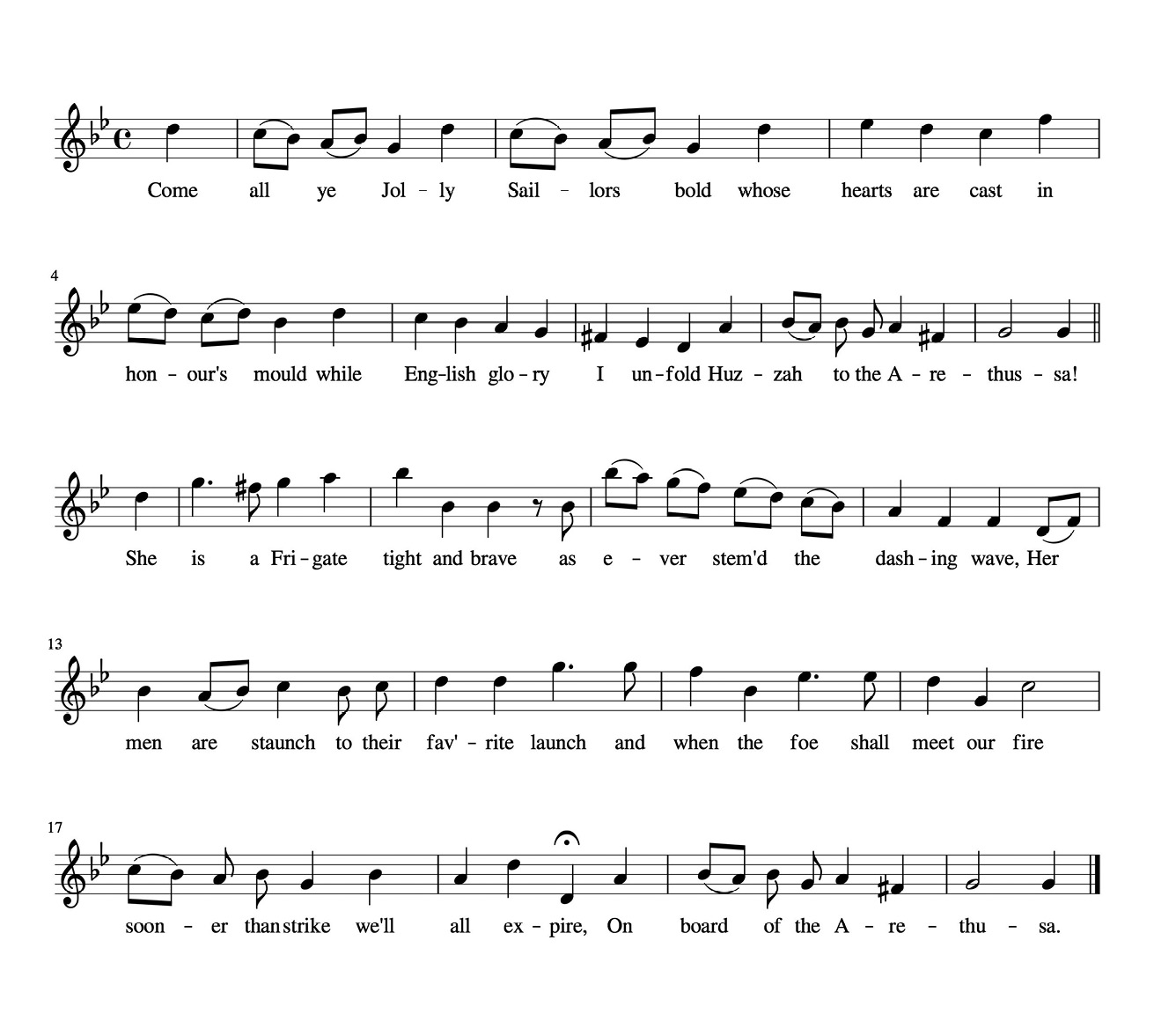

Happily, this song resists the argument that cheap print culture prioritized the transmission of printed texts over musical performance. Not only was William Brown not, in fact, selling a genuine text but rather the by-product of his own sung performance — thereby emphasizing the pleasurable and recognizable qualities of his song — but the song in question is highly dependent upon its original music. Rather than being written in a standard ballad metre it takes the form of ten-line stanzas of uneven length, with a complex rhyme scheme: aaabccd(internal)eeb. There is, I think, no question of its being sung to any tune but its own. Brown, like any solo singer, will have made the song his own (just as I myself cannot resist substituting two staccato crotchets for the more languid minim and crotchet of Shield’s version on every ‘–thusa’ of ‘Arethusa’, which to my ear lends the tune a more swashbuckling quality). But the song’s popularity in 1796 will have rested on its status as a memorable musical hit, associated with Incledon’s celebrity but standing up in its own right as an accessible, stirring, pleasurable melody — song as musical entertainment in the sense we understand it today, where the distinctive contours of the tune are of supreme importance to its effect (Fig. 8.1).

Although the song’s structure is uncommon, its journey is a familiar one. Any number of hit slip songs came to London from Ireland during this century via compilations of dance tunes, ‘The Black Joke’ being perhaps the best known.11 Many more originated on the London stage or in its pleasure gardens. They were united by their distinctive musical (as well as textual) interest, providing a constantly replenished repertoire of tunes that circulated by simultaneous print and oral transmission — tunes that had an aesthetic as well as a functional quality. Their mass dissemination, far from being envisioned or intended by their theatrical creators, was enabled by the agency of a hungry, discriminating mass market which would appropriate the songs it wanted from elite spaces with no conception of intellectual copyright, paying literally small change for access to a host of songs. So it was that William Brown, an untutored, immature boy from Devon, could play as central a part as any in the circulation of such a song, learning the tune from his fellow ballad singers who would originally have obtained it by, for instance, saving up for a cheap seat at the theatre or eavesdropping on rehearsals at the pleasure gardens.12 This was a healthy, irreverent mass musical culture. The slip song was its iconic physical incarnation, cheap, minimalist, unlicensed. It is a culture I have taken to calling the ‘mainstream’.13

Fig. 8.1. William Shield’s arrangement of ‘The Arethusa’ (first stanza). London, British Library, H.1653.b.(28.).

The mainstream in the long eighteenth century

In the second half of this chapter I want to introduce the case for the eighteenth century as the crucial era for the establishment of a mainstream song culture, spanning both social and geographical differences across Britain, which remains familiar to this day. The slip song is perhaps its ultimate material incarnation: the cheap, ephemeral, accessible product that enabled a repertoire meant for the middling denizens of major cities to be enjoyed by all ages and all classes. The slip, of course, did not exist in a vacuum. Mediating between the printers and their public there were William Brown’s peers, the ballad singers. I have made the case elsewhere, and at length, for the indispensable role of the ballad singer in turning these songs into a ubiquitous cultural product, heard everywhere, their words on the page but their tunes in the mouth.14 Here, I would like to think a bit more about the repertoire itself across the long eighteenth century.

To generalize: between the Restoration and what might be conceived of as the triumph of harmony in the middle third of the nineteenth century, when even the masses began to consume their music in four-part vocals or to the accompaniment of chord progressions constructed on piano or guitar, there was a period of more than 150 years when the mainstream song adhered to a very narrow set of characteristics. It was strophic, organized in a succession of stanzas (and often choruses) set to repetitive music. The music could range in complexity from an eight- to a 32-bar form, but was most commonly sixteen bars arranged (more or less) in an AABA structure. On this count, ‘The Arethusa’ is about as exceptional as things could get. Thanks to its particular origins with O’Carolan, its tune is twenty bars long rather than sixteen. Even here, however, the final part concludes with a return to the closing cadence of the eight-bar A section.

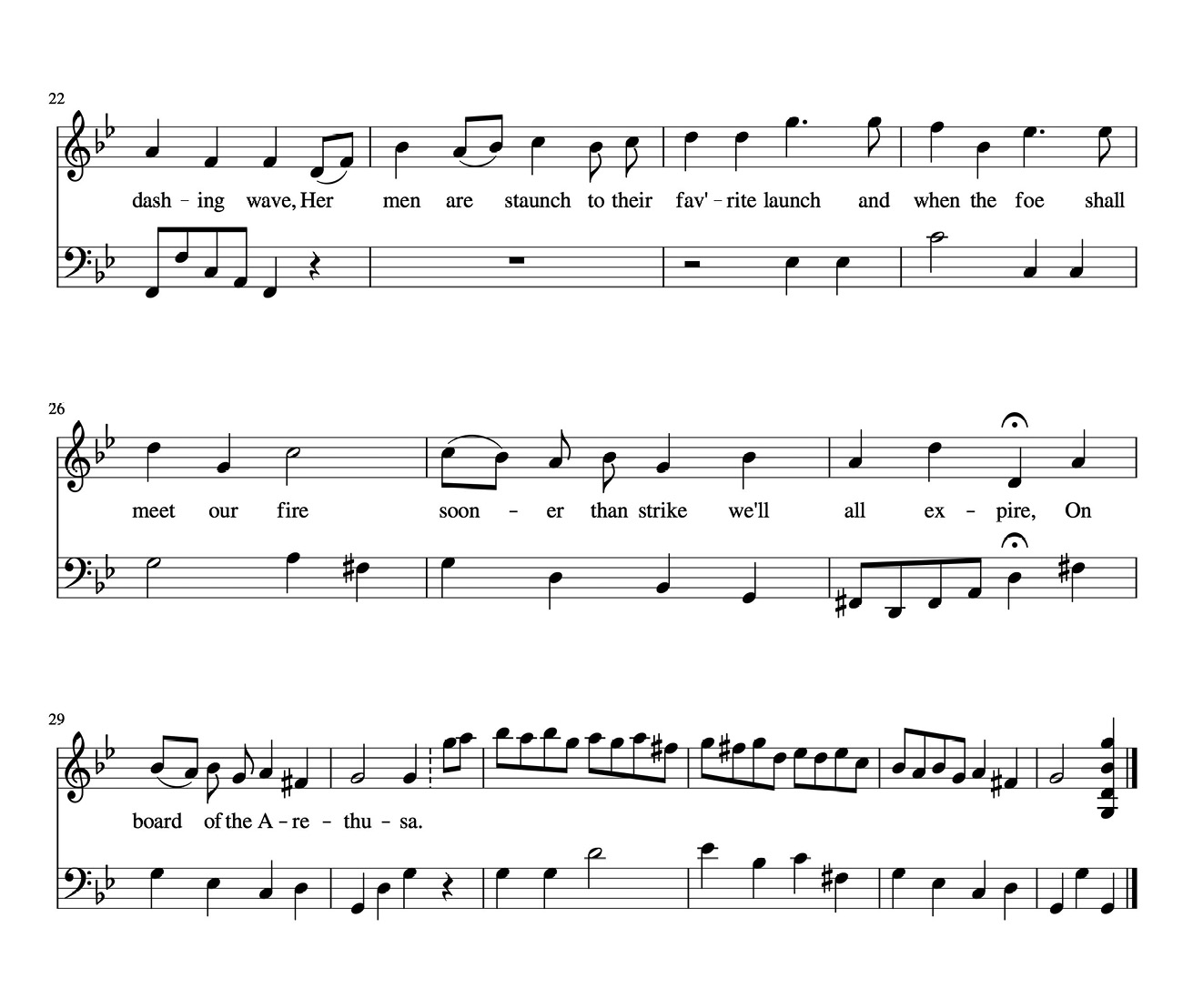

In other respects, though, it conforms entirely to wider mainstream conventions. Its modulations between keys are straightforward and return emphatically to their starting point. Its range in pitch is broad enough to allow for the melodic contours and leaps that lend it interest and distinction as a tune, with dramatic highs and lows, but remains at all times within the compass of the amateur singer, rather than the two-octave and more spans of some operatic arias. Its implied tempo is that of a ‘pop’ song. The mainstream songs found on slips do not appear to have gone to the extremes represented either by the most dirge-like of psalms or by the showy speeds of certain patter songs familiar from the opera or later music hall (think of the ‘Largo al factotum’ aria from Rossini’s Barber of Seville, with its tongue-twisters sung allegro vivace). Above all — and this is the ultimate hallmark of the mainstream song, particularly during the long eighteenth century — when stripped of its arrangement and reduced to a bare vocal melody, it is still eminently singable (Fig. 8.2). As words and tune alone, it retains all the drama, interest, and scope for aesthetic enjoyment that allowed it to function in the musically minimal world of the street ballad singer, the alehouse, the open road or the sea, and the poor household. Nor is this a compositional accident. For all that Shield includes a bass, the occasional chord, and embellishments for flute, even the commercial sheet music of ‘The Arethusa’ points to a conception of songwriting that is led by melody.

Fig. 8.2. ‘The Arethusa’, vocal melody.

As I have discussed elsewhere, such an approach amounted to a national ideology during this period.15 Both English song and the ‘national’ airs of the Celtic nations were thought of by contemporary musical theorists as essentially simple and melodic.16 Over-ornate melodicism was associated with Italy; chromaticism and a focus on harmony were associated with Germany. The English songwriters who composed for the theatres, ballad operas, or pleasure gardens seem to have written tunes first and then fitted basses or triads to them afterwards. Of course, this was necessarily the case with those many songs, such as ‘The Arethusa’, that arranged or adapted pre-existing melodies from tune-books for fiddle or flute.

This compositional practice, exemplified by the composer Charles Dibdin purportedly writing the song ‘True Courage’ in his head while walking round his garden before dinner and only later adding a plain accompaniment in line with his own pedagogical theories, also reflected performance practice.17 Performances of these songs at venues such as Covent Garden, Sadler’s Wells, Astley’s Amphitheatre, Vauxhall Gardens, or the Rotunda at Ranelagh were usually accompanied by small orchestras, primarily strings and woodwind.18 Domestic performances in middle-class parlours were usually accompanied by a keyboard part performed on the harpsichord, spinet, forte-piano, or, ultimately, pianoforte. Yet for all that, they were led by the singer who was invariably the star performer, whether on stage or in her own home. Even when they were visible, the instrumentalists were rarely known by name.19 Prevailing modes of theatricality (remembering that this song culture was inextricably bound up with the theatre) dictated a character-led vocal performance, reinforced by the invariable presence of fermata over important notes in sheet-music transcriptions, or indications of rallentando (gradually slowing down) and a tempo (returning to the previous speed).

All these conventions indicate a culture of melody-led song, with skilled accompanists following the gestures and performance decisions of the singers. The writers, subservient to these better-paid stars and aware of their songs’ afterlives in less formal spaces, were therefore in the business of turning out short, pleasurable, memorable melodies, motivated by both ideology and pragmatism. Such was the mainstream song: versatile, mobile, basic.

Creating a canon

In conceiving of or representing their compositional style as national, as English or British, these songwriters and their publics were, predictably, talking out of their hats, or at least their wigs. A great many of the composers of mainstream song were English and performed a high degree of Englishness in their lives, writings, and choice of lyrical content for their compositions. Set against this, a smaller number of highly influential songwriters came from the European mainland. More importantly still, the vast majority of English composers either travelled abroad for their musical training or were trained by foreigners in England.

The best way of demonstrating this is to create a canon, which also serves our wider purpose of gaining a general understanding of mainstream song culture. The assembling of a formidable series of names, dates, works, and associations is an entirely unreconstructed act and historiographically discreditable in the extreme, and it is not an end in itself, although it does lead us to ask why no such recognized canon exists in the way it does for poets, novelists, composers of instrumental music, or exponents of practically any other cultural form. Rather, it is a necessary precondition if we are to draw any firm analytical conclusions about the supremely important yet historically marginalized body of songwriters responsible for the generation of mainstream melodies.

There is no getting away from the fact that this is a canon of white men in wigs, so I may as well cave in to the formal conventions of the ‘great man’ narrative and say that the long eighteenth-century mainstream stretched from Henry Purcell (1659–95) to Henry Bishop (1786–1855).20 Except that Purcell, by far the best-known name on the list, was preceded by his family friend Matthew Locke (c.1622–77), who himself had various antecedents that early modernists would doubtless wish to make part of the conversation. So perhaps I should adopt a wholly arbitrary cut-off point of 1700. The fact that such respectable, court-based, baroque composers as Locke and Purcell were part of the same mainstream song culture as the slips peddled by the urchin William Brown may at first seem faintly surprising. If so, it is because we have forgotten something well known.

More than eighty years ago, Roy Lamson and Robert Gale Noyes compiled astonishing records of the cheap print editions of works by the great English Restoration composers.21 Lamson wrote that, ‘Stolen bodily by broadside-balladists for airs to their doggerel verses, many of Purcell’s melodies became familiar street-tunes’, and, citing as his prime example ‘If Love’s a Sweet Passion’, an aria from The Fairy Queen conforming in every respect to the characteristics of mainstream song, went on to say: ‘Only Matthew Locke’s “The Delights of the Bottle”, the setting of a song in Shadwell’s opera Psyche (1675), comes into competition. Locke’s tune was popular for eleven ballads, but to Purcell’s “If love’s a sweet passion” at least thirty-five broadsides were sung.’22

This is, of course, a crucial point. While the words of many mainstream songs originated with ballad poets and ballad singers themselves, especially since so many were contrafacta or parodies (although authorship might equally reside with Dryden, Pope, or Byron), the melodies — each of which could sustain numerous textual re-settings — appear, where their origin is known, to have come entirely from or via the trained composers of the theatres and pleasure gardens. Lamson and Noyes go on to cite many other luminaries whose works were enjoyed as much indirectly by a demotic street audience as they were directly by their own well-heeled patrons and audiences.

If this eloquent truth has somehow fallen out of our consciousness, it is primarily down to the influence of the great post-war cultural historian Peter Burke, whose view of the eighteenth century was one whereby popular and elite culture consciously uncoupled, with the two tribes no longer sharing the common culture of an earlier time.23 Burke includes songs and ballads in his remarkably broad analysis of early modern European culture, and here he is regrettably indebted to Francis James Child for his information, with consequences that are all too predictable.24 Burke attributes sole historical agency to the elite, whom he sees as abandoning what was once a common culture to the masses, to whom it was left as a residual, subordinate part of a severed whole. This takes no account of the operation of the mainstream, which in the case of song was founded on the systematic appropriation of elite and middling material by a dynamic mass market. This led more than one composer to lament the immense hypothetical royalties lost to this piracy. Charles Dibdin the Younger even sought legal advice on whether it would be worthwhile prosecuting the worst-offending printers, as his father had done (it was not).25 But mention of the Dibdins recalls me to my purpose, which is to follow the illustrious names of Locke and Purcell with their eighteenth-century successor songwriters.26

The early part of the century was dominated by a contemporary of Purcell who contrived to live rather longer, Richard Leveridge (1670–1758), composer of any number of famous songs, principally for the new genre of ballad opera.27 Leveridge’s three best-known compositions are the rearranged melody of ‘A Cobler There Was’ (often known as ‘Derry Down’), ‘Black-Ey’d Susan’, and ‘The Roast Beef of Old England’. His only rival in importance must be Henry Carey (1687–1743), composer of ‘Sally in our Alley’ and rumoured to be responsible for the form of ‘God Save the King’ that arose in the eighteenth century. His son, George Saville Carey (1743–1807), another prolific songwriter, said proudly (if contortedly) of his own songs that ‘when they have been yelled through the loud discordant lungs of an itinerant ballad-singer, where they have more been attended to from the incident than the music by the plebeian listeners in the streets of London, or sung as Tom of Bedlam did his frantic scraps, “at fairs, or wakes, or market-towns” […] my relatives hereafter, when I may be no more, though I may have done so little, may be glad, trifling as they are, that I have done so much’.28

A still more noteworthy father-son pairing was that of Thomas (1710–78) and Michael (1740–86) Arne, the former the composer of numerous successful and enduring songs, of which ‘Rule, Britannia!’ is the most remarkable. The latter’s more modest contribution to the mainstream is typified by the song sometimes known as ‘Loose Ev’ry Sail’. Thomas Arne’s almost exact contemporary was William Boyce (1711–79), once again best remembered for a bellicose naval hit, ‘Heart of Oak’. The next generation gave rise to the Vauxhall Gardens songwriters, among whose leading lights was Johann Christian Bach (1735–82), the youngest son of Johann Sebastian. Of his many influential Vauxhall songs, the one that proved the most successful in cheap print was ‘Cease a While Ye Winds to Blow’, which became known as ‘The Wanderer’ and spawned many answers and imitations.29

Bach had a close colleague in Samuel Arnold (1740–1802), whose biggest slip hit may have been ‘Little Sally’s Wooden Ware’, but whose most enduring mainstream melody is surely his arrangement of ‘Oh Dear, What Can the Matter Be?’. The 1740s were a good decade for prolific and staggeringly influential songwriters, ushering into the world Charles Dibdin the Elder (c.1745–1814), James Hook (1746–1827), and William Shield (c.1748–1829), who wrote perhaps four thousand songs between them. In their cases, it seems absurd to single out individual songs, but those best known today might be, respectively, ‘Tom Bowling’, ‘The Lass of Richmond Hill’, and ‘Bow Wow Wow’, especially since the consensus has been reached that Shield merely arranged ‘The Arethusa’.

Similarly prolific (though understandably less fêted) was William Reeve (1757–1815), responsible for endless stage-Irish compositions such as ‘Land of Potatoes’, and noteworthy to this readership for setting Charles Dibdin the Younger’s lyric ‘Hole in the Ballad’. More celebrated was Stephen Storace (1762–96), whose afterpiece No Song, No Supper alone yielded two great hits in ‘The Dauntless Sailor’ and ‘With Lowly Suit’, also known as ‘The Ballad-Singer’s Petition’.30 Actor-singer Charles Dignum (c.1765–1827) had hits of his own composition in the topical ‘The Fight off Camperdown’ and the perennial ‘The Disabled Seaman’, themes that reached their zenith in the best known of John Braham’s (c.1774–1856) many songs, ‘The Death of Nelson’, preceded by ‘The Death of Abercrombie’ and less tragic hits such as ‘The Beautiful Maid’. With Braham we might be said to have exhausted the eighteenth century, but it is worth concluding with a towering composer of the early nineteenth to illustrate how the tradition continued. Henry Bishop (1786–1855) was in every way a typical mainstream songwriter, whose biggest song, ‘Home, Sweet Home’, has left as large a mark on anglophone culture as any yet mentioned.

Characterizing the canon

Having assembled a brief list of names and dates, the natural questions are what to do with it and whether it was worth compiling in the first place. Happily, there are features common to both the songs and their composers that are helpful in trying to characterize the eighteenth-century mainstream. Thinking about the songs, given the wider concerns of this volume, it is interesting how they differ from their seventeenth-century predecessors. While there is a strong musical similarity and a general flavour of the baroque, one objective change that took place with the advent of the Georgian era was that the songs became shorter. Not in their original, stage incarnations — since those of Purcell, Locke, and their contemporaries were of similar and relatively brief duration — but in their transition to the street and the slip.

In the seventeenth century, stage songs appropriated by ballad printers and singers, and transferred to broadsides, were generally lengthened by any number of stanzas so as both to fill the sheet and to meet the expectations of singers and audiences.31 A broadside edition of Locke’s ‘The Delights of the Bottle’ (quoted by Noyes and Lamson) is headed with the following apologia:

Gallants, from faults he cannot be exempt,

Who doth a task so difficult attempt;

I know I shall not hit your features right,

’Tis hard to imitate in black and whight.

Some Lines were drawn by a more skilful hand,

And which they were you’l [sic] quickly understand;

Excuse me therefore if I do you wrong,

I did but make a Ballad of a Song.32

The final couplet is fascinating, suggesting a period when ‘ballad’ and ‘song’ were to be contrasted on grounds of length, and perhaps performance context. Although not all songs published in cheap print editions during the eighteenth century were necessarily shorter than before, there is a definite trend to be observed, especially as regards the mainstream songs that were taken from the theatres and pleasure gardens and reproduced on slips. While the reasons for this change are beyond the scope of this chapter, the result was a far greater conformity between the two versions — rarely more than four or five stanzas of distinctive music, with their material form (the slip) reifying these new qualities of brevity and portability.

As for the songwriters, clear themes emerge. Of my fourteen names (sons not counting), nine were born in London, one’s birthplace is unknown, and only the three great names of the 1740s hailed from elsewhere in England — Southampton, Norwich, and Swalwell (Northumberland). Bach, of course, born in Leipzig, is the other exception. All came from lower-middling backgrounds, a couple were illegitimate, and just two (save Bach) were from musical families. Shield’s father was a music teacher, and Storace’s played the double bass. The rest were typically sons of craftsmen and clerks. Their sources of musical education were various, encompassing tutors, choir schools, apprenticeships, and organists, but one uniting theme is the cosmopolitanism of their musical influences. This is extremely important given the rather xenophobic, little-England discourse that framed the song culture of the century, and the fact that so many of their enduring hits were patriotic odes to the navy and the sea. In fact, nine of the thirteen English composers demonstrably owed their training to continental musicians, who were overwhelmingly Italian, and even Dibdin, a locus for jingoistic discourse, taught himself everything he knew out of Rameau. Storace was a second-generation Neapolitan immigrant, and Braham suffered from anti-Semitism during his rise to fame.

Nor were they all given to writing endless sea songs. Even Dibdin’s constituted just some 9 per cent of his repertoire.33 Rather, it was this part of their output that found the greatest favour with cheap printers and their publics, especially during a century of almost ceaseless warfare. In fact, all of them worked constantly with Italian, German, and French musicians, in the theatres and especially the pleasure gardens, where they were just as likely to turn out romantic and pastoral songs. This last point underlines the most glaring common feature: that all of them were employed in London. Although regional song cultures continued to thrive in the eighteenth century, during which time regional printers also began to flourish and London itself was constantly being renewed by influences from the continent and also from the English regions, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, the mainstream itself was characterized by a strongly metropolitan focus. These white men in wigs were Londoners, if sometimes only by adoption; they were of lower-middling origin; and they owed their craft as much to the continent as to England.

Finally, they may have been men, but as recent scholarship has underlined, the songs often owed their initial success to the performances and celebrity of female singers, a fact that became unavoidable during the first flush of ballad opera and that remained the case well into the nineteenth century, when Catherine Stephens, Eliza Vestris, and many others became household names.34 None of which is to try and retro-fit a progressive narrative on to what was clearly a deeply patriarchal society, a fact reinforced by the series of father and son songwriters, including not only Arne and Carey but also the Linleys and, if the writers of the words are taken into account, the Arnolds and Dibdins too. There are subtleties to be teased out and the cosmopolitan nature of ‘English’ song should certainly be highlighted, but this was essentially a clubbable metropolitan culture of relative (if not absolute) privilege which became, if only through the work of the slip song press, perhaps the single most significant cultural force of the century.

* * *

Why am I, in an act of wilful anachronism and against all the revisionist tenets of social and cultural history, writing this chapter now? Surely, if a canon demonstrably exists, then it has long since been dismantled as ‘old hat’? Yet no such canon has ever been constructed. The two isolated works that perhaps come the closest to the attempt are an anthology of sheet music produced by Alfred Moffat and Frank Kidson in 1911 as a successor to an earlier compilation stretching from the Elizabethan to the mid-Georgian period (and therefore eschewing the century-based periodization I have advanced here), and a great scholarly tome from 1973, now long out of print, by Roger Fiske.35 Neither work actually argues for the recognition of its subjects as a coherent and culturally important body, and Fiske’s attitude to the composers he discusses is complex and conflicted, sometimes tipping into outright disdain.

There are several reasons for this neglect. The canon as a historical phenomenon is a product of the nineteenth century, of the Victorian impulse to categorize, combined with the Romantic idealization of the individual genius. As primarily commercial songwriters, employed by theatres and working to commission, the figures discussed here were especially resistant to a narrative of spontaneous artistic self-expression. On a practical level, they fell short when compared to poets, playwrights, novelists, or painters. Working with writers, composers were usually only half of the story, and contemporaries tended to anthologize English songwriting with regard to verse over melody.36 Some writers, such as John Gay and David Garrick, enjoyed far greater renown than their musical partners. Moreover, although some of the songwriters performed or sang their own works, others relied on actors from the outset. It is no coincidence that the nineteenth century venerated Dibdin above all others, because only he united the roles of poet, composer, and performer. Nor were most of the composers solely or even primarily songwriters; rather, songwriting was just one component of a wider body of work, both instrumental and vocal. While arguments might be — and sometimes were — made for the rude vitality and character of English song, there are very few defences of English music in general during the eighteenth century, when the withering assessment of Charles Burney generally held sway.37

These difficulties — and, above all, a self-conscious inferiority complex about English music which would only be compounded in the nineteenth century — explain the historical lack of a songwriting canon.38 That these composers remain relatively neglected today is in part down to the same reasons as in the past, but also down to a decline in the cultural capital of song.39 As a historicized art form it holds relatively low status, and the significance of this sort of song in particular has been largely obscured by the far greater scholarly interest in the ‘ballad’ (however defined), a field especially rich in the early modern period. There is perhaps a tendency, by historians, musicologists, and literary scholars, to underestimate the vast cultural importance and influence of the sorts of songs found on slips, which reached further than any other medium.

It does not help that the subject can seem so unfashionable. The mainstream (as exemplified by these composers) lacks the glamour of labouring-class cultural production; the political tendencies of many of its standout hits are often unsavoury; the composers were, as individuals, a rather boring and unlovely lot. When coupled with the low aesthetic status of the compositions, the prospect is not attractive. Against all of which, I can only raise the historian’s objection, that these songs mattered. They sold in their hundreds of thousands; they were consumed by all classes. Their tunes formed a large part of the musical life of most Britons; their texts mediated every social development, from nationalism, to sociability, to gender roles and relations. The material processes of their distribution provide a fascinating model of working-class appropriation of middling and elite culture, while giving the lie to any narrative of an insular English culture cut off from the wider world. And after spending a while with songs like ‘The Arethusa’, it is even tempting to make the case that they are still worth singing.

Appendix

Come all ye jolly sailors bold,

Whose hearts are cast in honour’s mould

While England’s glory I unfold,

Huzzah to the Arethusa!

She is a frigate tight and brave

As ever stemm’d the crashing wave,

Her men are staunch to their fav’rite launch

And when the foe shall meet our fire,

Sooner than fight we’ll all expire,

On board of the Arethusa!

’Twas with the spring-fleet she went out,

The English Channel to cruise about,

When four French sail, in show so stout,

Bore down on the Arethusa.

The fam’d Belle Poule straight ahead did lie,

The Arethusa seem’d to fly,

Not a sheet, nor a tack, nor a brace did she slack

Tho’ the Frenchmen laugh’d, and thought it stuff,

But they knew not the handful of men how tough

On board of the Arethusa!

On deck five hundred men did dance

The stoutest they could find in France

We with two hundred did advance

On board the Arethusa.

Our Captain hail’d the Frenchman, ho!

The Frenchman then cried out hallo!

Bear down, d’ye see, to our admiral’s lee,

No no, says the Frenchman, tha t can’t be,

Then I must lug you along with me

Says the saucy Arethusa!

The fight was off the Frenchman’s land

We forc’d them back upon their strand

For we fought till not a stick would stand

Of the gallant Arethusa.

And now we’ve driv’n the foes ashore

Never to fight with Britons more,

Let each fill a glass to his fav’rite lass,

A health to our captain and officers true,

And all who belong to the jovial crew

On board of the Arethusa!

1 William Brown, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of William Brown (York: T. Weightman, 1829), p. 13.

2 David Love, The Life, Adventures, and Experience, of David Love, 3rd edn (Nottingham: printed by Sutton & Son, for the author, 1823), p. 66. Love himself was not above subterfuge of Brown’s sort, however, as on the same page he confesses to disposing of these same ‘stale’ ballads by ‘crying, it is all found out, and the rogues will be hung […] some people said we have found out you [sic]; this we knew some weeks ago; others asked me, What is found out? I said, buy it, and you will see.’

3 Simply searching the word ‘ballad’ in the British Museum’s online database yields dozens of examples, of which perhaps the most iconic is Henry Robert Morland’s, frequently reproduced under numerous titles all including the words ‘Ballad Singer’ (c.1764).

4 This early modern perspective has been challenged by Christopher Marsh, Music and Society in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), which includes two long chapters on ballad culture.

5 Edward T. Cone, The Composer’s Voice (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974), p. 49.

6 [Frank Kidson], ‘New Lights upon Old Tunes: “The Arethusa” ’, Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 35 (1 October 1894), 666–68; Wm. H. Grattan Flood, ‘The Irish Origin of Shield’s “Arethusa” ’, Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 43 (1 May 1902), 339; W. H. Grattan Flood, ‘The Irish Provenance of Three English Sea-Song Melodies’, Musical Times, 51 (1 November 1910), 712–13; W. H. Grattan Flood and Lucy E. Broadwood, ‘ “The Arethusa” Air and “Hussey’s Maggot” ’, Musical Times, 52 (1 January 1911), 26–27.

7 It is worth noting that the British Library have sided with Grattan Flood here too, attributing ‘The Arethusa’ to O’Carolan in most of their entries for the song. The original O’Carolan source for ‘The Arethusa’ is commonly known as ‘Miss MacDermott’.

8 Flood and Broadwood, ‘ “The Arethusa” Air’, p. 27.

9 To cite one example from each country, ‘Princess Royal’ was published in John Walsh, The Compleat Country Dancing-Master (London: I. Walsh, 1731) (a 1715 edition by the same publisher appears to have a different tune); by William Mainwaring of Corelli’s Head, College Green, Dublin, in 1743; and in Alexander MacGlashan, Collection of Scots Measures, Hornpipes, Jigs, Allemands, and Cotillions (Edinburgh: N. Stewart, 1778).

10 There is a suggestion in the memoirs of William Parke, a musician in the Covent Garden orchestra, that the song debuted as early as 1794 in Netley Abbey, but if so it must have been an ad hoc interpolation, as it is not included in the full score of that production at London, British Library, D.287.(4.). See also William T. Parke, Musical Memoirs; Comprising an Account of the General State of Music in England, 2 vols (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830). A full reduction of Lock and Key for German flute can be viewed online at London, British Library, c.105.v.(3.). ‘The Arethusa’ is on pp. 24–25.

11 Paul Dennant, ‘The “barbarous old English jig”: The “Black Joke” in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, Folk Music Journal, 10.3 (2013), 298–318.

12 The ways in which ballad singers obtained their melodies are discussed further in Oskar Cox Jensen, The Ballad-Singer in Georgian and Victorian London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), chapters 3, 4.

13 Cox Jensen, The Ballad-Singer, chapter 4.

14 Cox Jensen, The Ballad-Singer, chapter 4.

15 Oskar Cox Jensen, ‘ “True Courage”: A Song in History’, in Charles Dibdin and Late Georgian Culture, ed. Oskar Cox Jensen, David Kennerley, and Ian Newman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 115–36.

16 There has been a recent upsurge of interest in the concept of the national air in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. See, for example, Celeste Langan, ‘Scotch Drink and Irish Harps: Mediations of the National Air’, in The Figure of Music in Nineteenth-Century British Poetry, ed. Phyllis Weliver (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2016 [2005]), pp. 25–49; Studies in Romanticism, 58.4 (2019), special issue on ‘Song and the City’: Ian Newman and Gillian Russell, ‘Metropolitan Songs and Songsters: Ephemerality in the World City’, Studies in Romanticism, 58.4 (2019), 429–49 (pp. 433–35); James Grande, ‘London Songs, Glamorgan Hymns: Iolo Morganwg and the Music of Dissent’, Studies in Romanticism, 58.4 (2019), 481–503. See also the Romantic National Song Network rnsn.glasgow.ac.uk.

17 Cox Jensen, ‘True Courage’.

18 There is now a wealth of literature on the music of the pleasure gardens to supplement the original resource, Warwick Wroth, The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century (London: Macmillan, 1896). See especially David Coke and Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011); Penelope J. Corfield, Vauxhall, Sex and Entertainment: London’s Pioneering Urban Pleasure Garden (London: History and Social Action, 2012); Jonathan Conlin (ed.), The Pleasure Garden, from Vauxhall to Coney Island (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

19 The best recent account of this culture is Berta Joncus, Kitty Clive, or The Fair Songster (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2019).

20 Details for the following paragraphs derive from two main sources, ODNB and Oxford Music Online, the latter of which incorporates the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Evidence for the slip song editions of the named ‘hit’ songs derives primarily from the Bodleian Library’s Broadside Ballads Online.

21 Robert Gale Noyes and Roy Lamson, ‘Broadside-Ballad Versions of the Songs in Restoration Drama’, Harvard Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, 19 (1937), 199–218; Roy Lamson, ‘Henry Purcell’s Dramatic Songs and the English Broadside Ballad’, PMLA, 53 (1938), 148–61.

22 Lamson, ‘Henry Purcell’s Dramatic Songs’, pp. 148–49.

23 Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, 3rd edn (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009 [1st edn, 1978]).

24 Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, p. 367.

25 Charles Dibdin the Elder complained in 1803 that: ‘I have already been under the very unpleasant necessity of commencing prosecutions against fourteen persons who have pirated my productions’, while his son was warned off prosecutions by his own printer who advised that ‘you’ll get damages awarded you no doubt, but you’ll have your own expenses, £60 perhaps, to pay; for the People that publish these things are too poor to pay damages or your expenses’. See Charles Dibdin, The Professional Life of Mr. Dibdin, 4 vols (London: Charles Dibdin, 1803), I, vi; George Speaight (ed.), Professional & Literary Memoirs of Charles Dibdin the Younger (London: Society for Theatre Research, 1956), p. 47.

26 The fourteen names I have selected for the eighteenth century, while not precisely objective, are included on the basis of their acknowledged prominence in slip editions; as such, there is no place for Thomas Linley (or his son), despite their being a key part of this world, as none of their compositions seems to have attained true mainstream status.

27 For the ballad opera genre, see Berta Joncus and Jeremy Barlow (eds), ‘The Stage’s Glory’: John Rich, 1692–1761 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011).

28 George Saville Carey, The Balnea, 2nd edn (London: J. W. Myers, 1799), p. vii.

29 For Bach (as a special case), see Johann Christian Bach, Favourite Songs Sung at Vauxhall Gardens, Originally Published in London, 1766–1779, ed. Stephen Roe (Tunbridge Wells: Richard Macnutt, 1985).

30 Storace boasts one of the best biographies of these composers, in Jane Girdham, English Opera in Late Eighteenth-Century London: Stephen Storace at Drury Lane (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).

31 Noyes and Lamson, ‘Broadside-Ballad Versions’, p. 199.

32 The Delights of the Bottle; or, The Town-Gallants Declaration for Women and Wine (printed for P. Brooksby, at the Golden Ball, near the hospital gate, in West Smithfield) [ESTC R14001].

33 Cox Jensen, ‘True Courage’.

34 Joncus, Kitty Clive; Tiffany Potter (ed.), Women, Popular Culture, and the Eighteenth Century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012); David Kennerley, Sounding Feminine: Women’s Voices in British Musical Culture, 1780–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

35 Alfred Moffat (ed.), English Songs of the Georgian Period, with historical notes by Frank Kidson (London: Bayley & Ferguson, 1911); Roger Fiske, English Theatre Music in the Eighteenth Century (London: Oxford University Press, 1973).

36 A prime example is John Aikin, Essays on Song-Writing, with a Collection of Such English Songs as Are Most Eminent for Poetical Merit, 2nd edn (London: Evans, 1810).

37 Charles Burney, A General History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period, 4 vols (London: printed for the author, 1776–89). This is all thoroughly discussed in Fiske, English Theatre Music, esp. p. vi.

38 As typified by the notorious titular phrase of Oscar Schmitz, Das Land ohne Musik: Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme (Munich: Georg Müller, 1904).

39 Neglected, that is, by musicologists, the inheritors of the ‘Land ohne Musik’ problem, above all, although there are now signs of revisionism from excellent scholars such as Amélie Addison, Alice Little, Ian Newman, and Brianna Robertson-Kirkland.