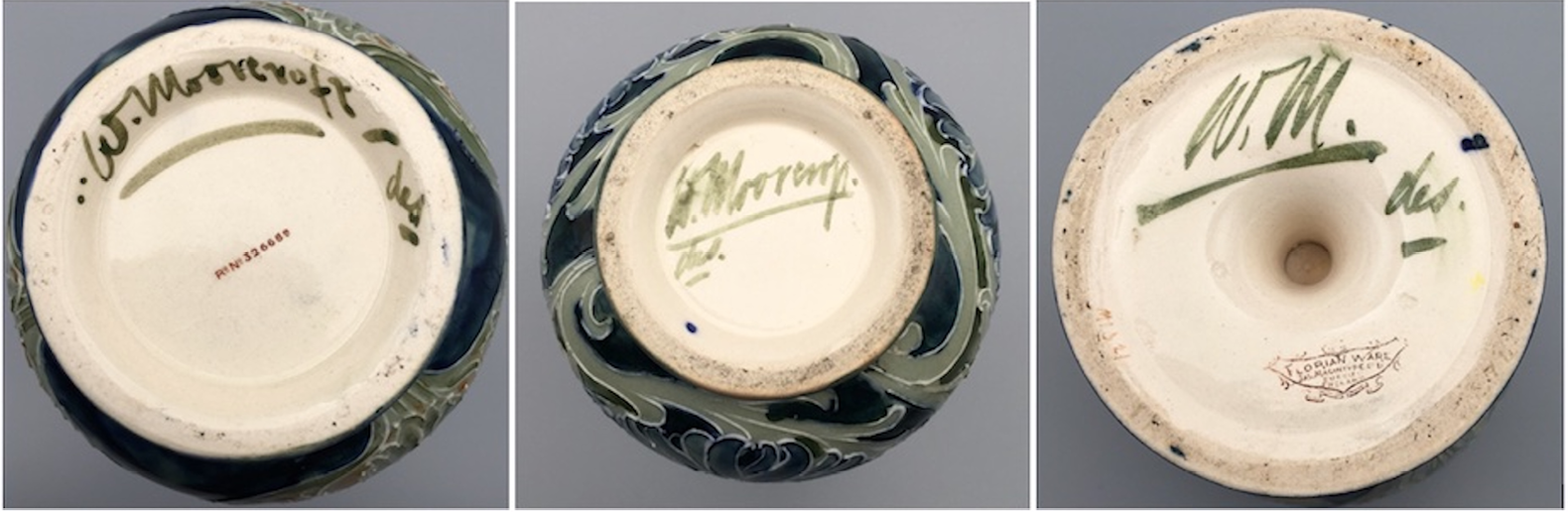

1. 1897–1900: The Making of a Potter

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.01

1. Background and Education

William Moorcroft was born in 1872. He was the son of a ceramic artist, Thomas Moorcroft, Chief Designer at E.J.D. Bodley’s, which was one of the leading potteries in Burslem. Years later, Moorcroft paid tribute to the formative influence of both his parents and to ‘their endeavour to surround their children with all things beautiful and elevating’.1 This childhood idyll, though, was short-lived. In May 1881, Moorcroft’s mother died, aged thirty-two, leaving his father to care for William and three brothers, two sisters having died in their infancy. Thomas employed a housekeeper, whom he married in 1884, but he himself died just nine months later, in 1885, aged thirty-six. Moorcroft was not quite thirteen.

If his parents had sown the seeds of artistic sensitivity, Moorcroft’s formal training helped them flourish. Burslem was at the centre of progressive art education in the Potteries. The Burslem School of Art, which had enjoyed a brief existence from 1853–56, reopened in 1869 as part of the Wedgwood Memorial Institute, the result of energetic promotion by William Woodall, secretary of the organising Committee. The Institute housed Schools of Art and Science, a public library, lecture venue, and exhibition space. It was a cultural centre created for the people of Burslem, and its intention was to educate and inspire manufacturers, designers and the general public alike. It benefited from generous public subscription, not least from Woodall himself, and from Thomas Hulme, a member of the Institute’s Technical Instruction Committee. Such support was crucial at a time when government funding was minimal, and the success of regional initiatives depended almost entirely on local patronage.

In Moorcroft’s day, the Burslem School of Art was one of the most forward-looking Schools in the country. This was in part due to its Principal, George Theaker, formerly a teacher at the Lambeth School of Art, whose collaboration with Henry Doulton in the 1870s was one of the earliest and most successful examples of an art school training designers for industry. Theaker was an innovative teacher, taking students beyond the rigid study of historical ornament which characterised the government’s design syllabus, and encouraging life and landscape drawing. His impact was strengthened by the support of Woodall, Chairman of the Technical Instruction Committee and, throughout the 1880s and 1890s, M.P. first for Stoke-upon-Trent, and then for Burslem and Hanley. Woodall used his contacts and influence to bring London speakers to the Institute (including William Morris in 1881), helping to create a vibrant cultural centre that was outward-looking in its activities. Of particular significance was Woodall’s membership of the Royal Commission on Technical Instruction, whose report of 1884 concluded that Schools of Art were failing in their responsibility to train industrial designers by placing too much emphasis on the academic study of ornament. Woodall shared the views of Morris and his followers that designers should understand the properties of the material for which they were designing, and he was committed to the establishment of practical science classes in the School. In this he reflected the progressive thinking of A.H. Church, first professor of chemistry at the Royal Academy, whose Cantor lectures, delivered at the Royal Society of Arts in 1880, were significantly entitled ‘Some points of contact between the scientific and artistic aspects of pottery’. And he attracted some of the foremost ceramic chemists as teachers: William Burton, who would soon play a defining role in the creation of art pottery at the newly established Pilkington’s Tile Factory, taught at the Institute from 1887 to 1891; and Henry Watkin, one of the first to obtain a Diploma in ceramic chemistry at the City and Guilds of London Institute, gave classes in the School of Science. These were singled out for praise in the Committee’s report of 1895:

It was a matter of congratulation that the pottery class maintained its prestige and its capable teacher […]. It was, however, a matter of regret that the facilities the classes afforded should be taken advantage of by so few students.2

It was evidently exceptional at the time to attend this class; Moorcroft, however, was one who did. Having re-enrolled at the Institute in the autumn of 1886, he attended classes in the Schools of both Science and Art for the next nine years.

Moorcroft’s technical instruction was complemented by equally formative training at the Crown Works, where Bodley had found him work after he left school in 1886. During these apprenticeship years he acquired all the basic skills of potting, and by 1889 he was both decorating and designing. Bodley’s new Art Director was Frederick Rhead, an experienced designer who had trained in the sophisticated decorative technique of pâte-sur-pâte with Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon at Minton in the 1870s, before moving to Wedgwood in 1878 where he worked closely with Thomas Allen. By 1891, Moorcroft may well have expected to make his career at the Crown Works, but it was not to be, as Bodley went bankrupt in early 1892. Times were precarious for pottery designers; jobs were scarce, the work was poorly paid, and security depended entirely on the commercial fortunes of the manufacturer. Rhead joined the (short-lived) Brownfield’s Guild Pottery Society, Ltd., set up in 1892 on the lines of C.R. Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft, and Moorcroft found work as a designer at the Flaxman Art Tile works of J & W Wade, which made majolica, transfer-printed tiles, and hand-decorated art tiles and pottery. On 13 March 1895, Edward Taylor, the forward-looking Principal of the Birmingham School of Art and (soon-to-be) co-founder of the Ruskin Pottery with his son, William Howson Taylor, was the invited speaker on Prize Day at the Burslem School; the Head of one pioneering School recognised a kindred spirit in another. Taylor paid tribute to Woodall and Hulme, whose enlightened vision and generosity provided unique facilities at the Institute, enabling the teaching of design as a practice, and encouraging a spirit of inquiry and innovation:

[…] I am glad to see from your prospectus that you have also such technical classes as will tend to link the work of the school with the industries of the town […] these special classes […] should be of the nature of art and science laboratories for students, in which research and experiment should be the main feature, and not the mere imparting of present trade tradition.3

This was Moorcroft’s last official event as a student at the Institute, but Taylor’s emphasis on the value of experiment was one which he would take with him throughout his career.

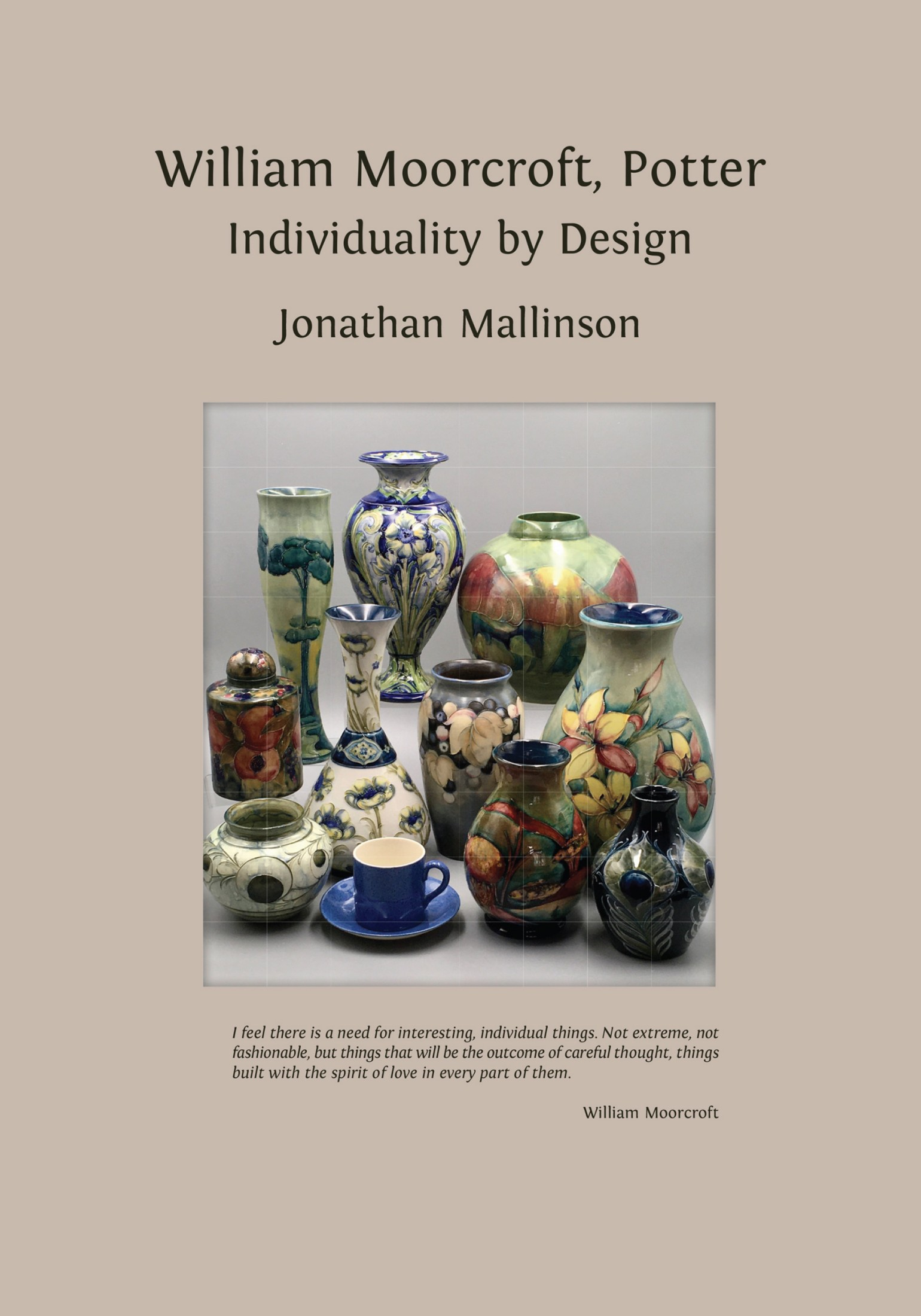

Fig. 1 Moorcroft in the mid-1890s. Photograph. Family papers. CC BY-NC

In 1895, Moorcroft was enrolled at the National Art Training School in South Kensington. He followed classes on ornament by Lewis Day, one of the leading designers of the time, and studied ancient and modern pottery at the South Kensington Museum. The course qualified graduates of the School to teach in the provincial schools of art, but it provided little practical training in industrial design, unlike the more progressive Central School, founded in 1896 to ‘encourage the industrial application of decorative art’. Looking back on his very brief spell as Director of the Royal College of Art (as the School would be re-named from 1896), Walter Crane described the institution he found, just two years after Moorcroft’s departure, as a ‘sort of mill in which to prepare art teachers’, and its curriculum as ‘terribly mechanical and lifeless’.4 In an article published in the Pottery Gazette little more than three years after Moorcroft’s graduation,5 Louis Bilton (a ceramic artist at Doulton, Burslem), expressed regret that few of its graduates were either equipped or inclined to practise their art in industry. Most would either ‘drift away into the crowd of struggling picture painters’, or produce designs neither ‘suitable for reproduction commercially, or even practical working patterns’. But Moorcroft was not such a one. He may have obtained his Art Teaching Certificate, but within a few months of his return to Burslem he began the work of a ceramic designer for which he had long been preparing. The poor relationship of manufacturers and designers would be a recurrent topic of discussion throughout Moorcroft’s career, but in his own case he could not have found a firm more sympathetic to the progressive and enlightened design education from which he had benefited, a firm which numbered among its Directors or former Directors, William Woodall, Thomas Hulme and Henry Watkin. The firm was James Macintyre & Co., Ltd.

2. James Macintyre and Co., Ltd.

First established by W.S. Kennedy in 1838 as a manufacturer of artists’ palettes, door furniture, and letters for signs, the company moved to the Washington Works in 1847. Macintyre, Kennedy’s brother-in-law, joined in 1852, and in 1854 became its sole proprietor, employing Thomas Hulme as his manager; in 1863, he took William Woodall (his son-in-law) and Hulme into partnership. After Macintyre’s death in 1868, Woodall and Hulme expanded its production of largely functional items to include tableware, advertising ashtrays, commemoratives, household fittings, tiles, chemical and sanitary wares.

Woodall was one of the most progressive manufacturers in the Potteries. Trained as a gas engineer, and formerly Chairman of the Burslem and Tunstall Gas Company, he brought business acumen, rather than experience as a potter, to the industry. He understood the need for a skilled and educated workforce, hence his commitment to art education; but he was a pioneer, too, in the reform of working conditions, being the first to introduce an eight-hour working day in the Potteries. It was entirely consistent with his exemplary relationship with his workforce, that they should present him in 1899 with an album of staff photographs, ‘a small token of gratitude for the many benefits received at your hands’.6 Hulme retired as Managing Director when Woodall entered parliament in 1880, but he kept a financial interest in the firm. A new partnership was formed, first with Thomas Wiltshaw and then, in 1887, with Henry Watkin, who had worked at Pinder Bourne in Nile Street. Other Directors were Gilbert Redgrave, who, like his father Richard Redgrave, worked in the Department of Education, and had served as Secretary to the Royal Commission; and three other members of the Woodall family, all with professional backgrounds in the gas industry: William’s two brothers, Henry and Corbet Woodall, and Corbet’s son, Corbett W. Woodall.

Shortly after the arrival of Watkin, the firm began production of porcelain insulators and switchgear for the new electricity industry. In 1893, a Limited Company was formed, and it embarked on a programme of expansion, with significant personal investment from the Directors. In addition to its development of electrical porcelain, it established an art pottery studio to complement its production of tableware and door furniture. Its beginnings were troubled. Minutes of Directors’ meetings in 1893 and 1894 record the short-lived careers of two designers, Mr Rowley and Mr Scaife, and the slightly longer appointment of Mr Wildig, whose contract was renewed for twelve months on 20 January 1894 ‘for the sum of £3 per week’. His ware, marketed as Washington Faience and decorated with coloured slip, gilding and applied relief ornament, attracted the attention of the Pottery Gazette in June 1894 which praised its ‘pure’ tones and ‘delicate’ tints. But it was not commercially successful, and in 1895 the Directors resolved to appoint a much more experienced designer, Harry Barnard, Under-Manager of the decorating studios at Doulton Lambeth. After its triumphant display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Doulton’s art pottery enjoyed international renown; to look to this firm for their Art Director was a clear declaration of intent. A Minute of 18 January 1895 recorded Barnard’s appointment ‘at a salary of £220 for the first year, to be increased to £250 should he remain a second year’. This initial salary represented an increase of over 40% on Wildig’s salary of £156 per annum (£3 a week); Macintyre’s were evidently prepared to invest money in art pottery, although they were still uncertain of its success. Barnard had trained as a modeller, and was experienced in forms of low-relief decoration. In his unpublished memoir, ‘Personal Record’, written around 1931, he described the technique he developed. Patterns, applied with stencils, were created in coloured slip (liquid clay), further ornament being applied freehand in white slip, as had been the practice on some Doulton Lambeth stoneware:7

[…] I called it ‘Gesso’, as it was a pâte-sur-pâte modelling, and the tool to produce it was one that I had made. This proved to be quite a surprise, nothing like it had been seen before. To make it a commercial line, I introduced also an appliqué of ‘slip’ in a form of stencil pattern, and the slip modelling was a free-hand treatment and covered up the spaces necessary in the stencil pattern and so hid to a great extent the fact that it was applied in that way.8

Gesso Faience was given its own elaborate backstamp, and by the end of 1895, hopes were clearly high, a Minute of 1 November 1895 recording that ‘the plastic decoration introduced by Mr Barnard promised to be commercially successful’.

But all this was to change. The firm was under increasingly acute financial pressure: an overdraft with the Bank which stood at just under £2,000 at the start of 1894, had increased to £6,000 by the summer of 1896, and on 18 January 1897 debentures were issued totalling £10,000 and funded by the Directors. In these circumstances, it is particularly surprising that a Minute of 25 January 1897 should record a decision ‘unanimously agreed’ that ‘immediate attempts be made to discover a new designer’. Just six weeks later, on 8 March 1897, Moorcroft’s appointment was announced: ‘It was reported that Mr Wm Moorcroft had been engaged, and would that day enter upon his duty as designer at a remuneration of 50/- [fifty shillings] per week’. Moorcroft’s salary (£130 p.a.) was considerably lower than Barnard’s, but at (just short of) twenty-five years of age he was much less experienced, and Barnard was still working there. But not for long. A Minute of 22 April 1897 recorded a provisional extension of Barnard’s contract, ‘at a reduced salary of £200 per annum’, and six weeks later, on 4 June 1897, the post was reduced to half-time, his salary to be paid jointly with Wedgwood. On 14 September 1897, an uncompromising Minute reported the end of his appointment: ‘Mr Harry Barnard was reported a complete failure, and it was decided to relinquish all claims on his services in favour of Messrs Wedgwood & Sons’.

Financial pressures and/or the commercial failure of Barnard’s designs doubtless motivated this dismissal; nevertheless, the firm’s growing deficit had clearly not deterred the Directors from making another appointment. Why the post was offered to Moorcroft, though, is a different matter. It is certainly the case that he was known to some of the firm’s Directors from his days at the Burslem School of Art, not least to Watkin whose classes Moorcroft had attended. He would also have been known to Watkin and Hulme from the Hill Top Chapel, where Moorcroft served as a Sunday School teacher, Watkin was a lay preacher, and Hulme was both Organist and Choirmaster. But it is true, too, that Moorcroft, newly returned from the National Art Training School, was not the standard product of state art education; his training had been a mixture of theoretical study and practical experience, learning ceramic design both through paper and clay, art and science, history and nature. He had taken full advantage of the progressive environment into which he had been born, and it was quite characteristic of Macintyre’s Directors, several of whom served on the School’s Technical Education Committee, that they recognised in him a designer with the potential to bring originality to their art pottery production.

Early in 1898, shortly after the departure of Barnard, Moorcroft was appointed Manager of Ornamental Ware, and given his own workrooms, a staff of decorators, and the exclusive services of a thrower and turner; he had sole responsibility for the training and supervision of his staff. It was the start of a period of creative collaboration, not just between Moorcroft and Macintyre’s, but also (and just as importantly) between Moorcroft and his decorators. Such was his appreciation of, and concern for, his staff that on 8 May 1899 a Directors’ Minute recorded a decision ‘at the request of Mr Moorcroft’, to give them more security. Some of these decorators may be seen in photographs surviving from the album presented to Woodall in 1899, just one week before Moorcroft’s request; two (Fanny Morrey and Jenny Leadbeater) would still be working with him more than thirty years later.

.jpg)

|

.png)

|

(L) Fig. 2 Decorators in Department of Ornamental Ware, J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd, 1899. Left to Right: Emily Jones, Mary (‘Polly’) Baskeyfield, Fanny Morrey, Jenny Leadbeater, Nellie Wood. Photograph. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 3 Decorators in Department of Ornamental Ware, J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd, 1899. Left to Right: Lillian Leighton, (?) Toft, Nellie Wood, Sally Cartledge, (unidentified), Annie Causley. Photograph. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

3. A New Slipware

When Moorcroft first joined Macintyre’s, he was employed to create designs for the functional wares produced in a department run by Mr Cresswell; responsibility for art wares remained with Barnard. Moorcroft designed a completely new range of decorations, with stylised floral motifs combined with abstract ornament in the form of frets and diapers. The patterns were applied by transfer printing, and finished off with gilding and enamel colours; the range would be called Aurelian. His first designs, featuring poppy, cornflower and briar rose, were registered in February 1898; these, and others, proved very popular and were produced for at least ten years. This collaboration with Cresswell’s department continued even after Moorcroft assumed responsibility for art wares. One early range was decorated with a repeating butterfly motif and other ornaments, applied in slip over a dark blue ground and finished with gilding and touches of white enamel. His most sophisticated range, however, was produced entirely in his own workshops; it was a completely original form of decorative slipware, and was named Florian ware.

For many contemporary critics, the quality of English pottery was declining, as much on account of its means of production as of its poor design. The widespread use of printed transfers, for instance, implied decoration which was merely applied, being neither literally nor metaphorically of a piece with the object. Ornament created in clay, however, had an integrity and permanence which was seen to characterise the highest form of ceramic art. The most esteemed example of this was pâte-sur-pâte, created by applying layers of slip to an unfired ceramic body, and then sculpted into low-relief decoration of great delicacy and sophistication; it was a method perfected in Solon’s studio at Minton, and subsequently adopted by Wedgwood and Doulton. In an article on the technique published in The Art Journal [AJ], Solon presented it as the model of authentic ceramic art:

[…] as a single operation is required to fire the piece and the relief decoration, which becomes, in that way, incorporated with the body, it may be regarded as essentially ceramic in character, a fundamental quality of truly good pottery […].9

Macintyre’s had long been looking to develop a less labour-intensive, but equally authentic form of slip decoration alongside their printed, enamelled and gilded ware. Washington and Gesso Faience were both, in their different ways, ‘essentially ceramic’ in so far as their decoration was integral to the body of the vessel, but their artistic qualities were too limited to attract the interest of a discerning public. Moorcroft situated his work in this same tradition, using slip as the means of creating ornament; but he used it in a quite different way, and with quite different effects. Some of his earliest Florian designs required the application of slip to form elaborate, abstract embellishments of great delicacy. But he was soon using it to adapt for ceramics the ancient technique of cloisonné enamelling in the decoration of metalware, creating compartments with slip rather than wires, and using metallic oxides to stain the clay, rather than applying enamels to the surface of the vessel. To the decorative potential of slip, Moorcroft added the limitless possibilities of colour. A similar technique was used occasionally for the decoration of the finest art tiles, but it had not been developed for the more challenging three-dimensional surface of pottery.

|

|

(L) Fig. 4 William Moorcroft, Vases in Butterfly Ware (1898), 17cm and Aurelian ware, with Poppy motif (c.1898), 7.5cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 5 William Moorcroft, Early Florian designs with prominent slip decoration. Vases with Cornflower motif (1898), 27.5cm, and gilded floral motifs (1898), 25cm. CC BY-NC

|

|

(L) Fig. 6 William Moorcroft, Experimental vase in Butterfly design decorated with Watkin’s Leadless Glaze (1898), 20cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 7 William Moorcroft, Early experiments with underglaze colour. Narcissus (c.1900) in shades of blue, 18cm; sleeve vase with Peacock motifs in celadon and blue (1899), 27cm; Iris (c.1899), in blue, green and russet, 25cm; 2-handled coupe with floral motif (c.1900), in blue, light green and yellow, 8cm. CC BY-NC

The widespread use of on-glaze enamel colours was seen as another sign of the declining quality of ceramic art. In a series of Cantor Lectures entitled ‘Material and Design in Pottery’, William Burton examined pottery decoration through the ages. In one lecture, he deplored the ‘general substitution of hard, thin, scratchy overglaze painting in place of the rich, juicy colour produced when the colour is used underglaze’.10 The ready availability of mass-produced and standardised colours may have been welcomed by many manufacturers, but for Burton it led to lifeless, standardised effects. Research and experiment were no longer the basis of modern industrial practice, as he lamented in a lecture to the Society of Arts, ‘The Palette of the Potter’:

Mechanical finish, and not artistic excellence, is now the great aim of all manufacture; to get an even ground of colour without the least trace of variation, and to repeat this thousands of times in succession, is the point at which the modern potter is compelled to aim.11

It was this desire to produce bright, uniform colours which largely accounted for the resistance to reducing the lead content of glazes, at a time when its dangers to pottery workers had become increasingly evident. Lead significantly reduced the melting point of the glaze, thus allowing both greater control of the firing, and a much wider range of colours.

A surviving trial vase in the Butterfly series carries the manuscript inscription ‘Watkin’s leadless glaze’ on its base, and is decorated with on-glaze enamels. It is clear, though, that Moorcroft did not pursue this method of decoration; his attitude to ceramic colour was very similar to Burton’s, for all the evident challenges. The firing temperature of a glost kiln was significantly higher than that of an enamel or muffle kiln, and the range of colours which could resist these higher temperatures without degrading was more limited. But whereas most underglaze colour was applied to the once-fired biscuit body, Moorcroft decorated the unfired clay, thereby limiting the range even further. The unusualness of this method was implied by Burton in ‘The Palette of the Potter’:

[…] the method of colouring the pottery after it has been once fired, saves the colours from being exposed to a fire angrier than need be, and the palette is extended by several colours that will endure the glazing heat, while they would be decomposed by exposure to the higher temperature of first firing.12

The difficulty was exacerbated, too, by the temperature of Macintyre’s kilns, firing industrial ceramics at temperatures around 1300 degrees Celsius, exceptionally high for earthenware. For all these limits, though, the potential for creating particularly rich colours was all the greater. Unfired clay was more porous than a biscuit body; this allowed the oxides to penetrate more deeply, a more intense colour ensuing as a result.

Moorcroft’s technique was not only without modern parallel, it required the experimental skills of the chemist to produce viable results. Commercially available colours were of little use, even if he had wished to use them; he had to produce his own. To create colours of the rich luminous quality only achieved by chemical reactions, he needed to experiment with different combinations of oxides, glaze recipes and kiln conditions. Nor did he rely on lead-based glazes to intensify his colours or to extend the range, adapting instead to the use of fritted lead, a method which reduced both the concentration and the toxicity of the lead oxide in the glaze. Moorcroft’s diaries and notebooks from this period testify to his irrepressible spirit of enquiry. One notebook entry recorded a path yet to explore: ‘Experiment: the effect of green body and cobalt glaze’, and in his diary for 1900, he made notes on different ways of producing yellow, one of the most unstable of colours, particularly at high temperatures. Research of this kind was acknowledged as rare, but for a critic writing in the Pottery Gazette, it represented the future of ceramic art:

[…] where in the history of English ceramics can a statement be found that this chemist or that has succeeded in compounding a new body or in developing a colour hitherto unknown. […] And why not? […] The reason is that as yet, in this country, scarcely any man of high scientific attainment has been encouraged to devote himself to ceramics.13

But Moorcroft’s interest in colour was not just scientific, it was undertaken in the service of ‘artistic excellence’. Contrasts and harmonies of colour were as essential to his conception of good design as form or ornament. In a notebook from 1900, he reflected on new experiments:

Ground to be washed all over in broken green; no ground to be prominent.

Green to be more conspicuous in design, blue forming borders.

And in another jotting from this same period, he wrote quite simply: ‘Form and colour unite to raise the highest sentiment’. The more restricted palette of underglaze colours at this early stage of Moorcroft’s work contrasted markedly with the more vibrant colours achievable with other methods of decoration. But what he produced were more subtle effects achieved by the interaction of different tones of blue or green, or the application of a light wash of secondary colour on a stained body. It was a mark of his originality that he should explore these possibilities, and of Macintyre’s faith in him that he was encouraged to do so.

4. Design and Realisation

Moorcroft’s conception of art pottery overlapped with modern thinking about ceramic decoration, drawing inspiration from the application of science to art. But it was modern, too, both in its aesthetic principles and its means of production. Pâte-sur-pâte focussed attention on the applied decoration; the vessel itself was, inevitably, secondary in its significance. Moorcroft’s ware, conversely, integrated ornament and body not just at the level of material, but also at the level of design.

It is characteristic of Moorcroft’s approach that his starting point was the introduction of new shapes, many inspired by Middle and Far Eastern, classical and early English traditions. The advantages of working with a thrower are evident. Not constrained by the use of moulds which limited the scope for variety and experiment, Moorcroft could trial a wide range of different forms. It was an invaluable asset for exploring new design possibilities, but it was also a luxury. At the end of the nineteenth century, the skilled thrower was already fast disappearing from the industrial workplace, as moulded ware became increasingly common. The economic advantages of a mould were clear, but no less clear, for some, was the resultant loss of quality; an article published in the Pottery Gazette was categorical:

There are so-called artistic potters who haven’t a throwing wheel on their premises […]. There is something about a piece of well-thrown ware, giving it a distinguished air, which the best moulded ware can never possess.14

Woodall and his directors clearly shared that view; theirs was an ambition to provide the best facilities for the best art ware, and they were prepared to invest in it.

Moorcroft was often inspired by classical shapes, but he decorated them in his own style. To do so was in itself a gamble, both for him and for Macintyre’s. The taste for conspicuous decoration still prevailed, and contemporary design seemed to be driven by commercial opportunism not artistic sensitivity; an article in the Pottery Gazette lamented the absence of ‘any simplicity or severity of style’ in a design world dominated by ‘ornament piled on ornament’.15 Moorcroft, though, was different. Notebooks and diaries of this period record constant reflection on design, form, colour and decoration, inspired by his reading or his observations in museums. A notebook from 1900 contains thoughts about the structure of ornament: ‘Where growth is suggested, give the pattern proper room to grow’, and another series of notes, on a sheet of paper dated 4 May 1900, refer to ornament in relation to the object it adorns. A recurrent theme is its integration with form, without which it can have neither purpose nor justification:

When ornament was applied to anything, it should support the construction.

The mere application of ornament is not decoration.

No ornamentation can be tolerated that is merely used for ornament.

No piece of pottery can be called good, unless it have a perfect balance of parts.

Moorcroft saw the purpose of ornament to accentuate form, not to draw attention to itself. Just as he favoured decoration which was of a piece with the body rather than applied to its surface, so too he conceived form and ornament as inseparable elements of design.

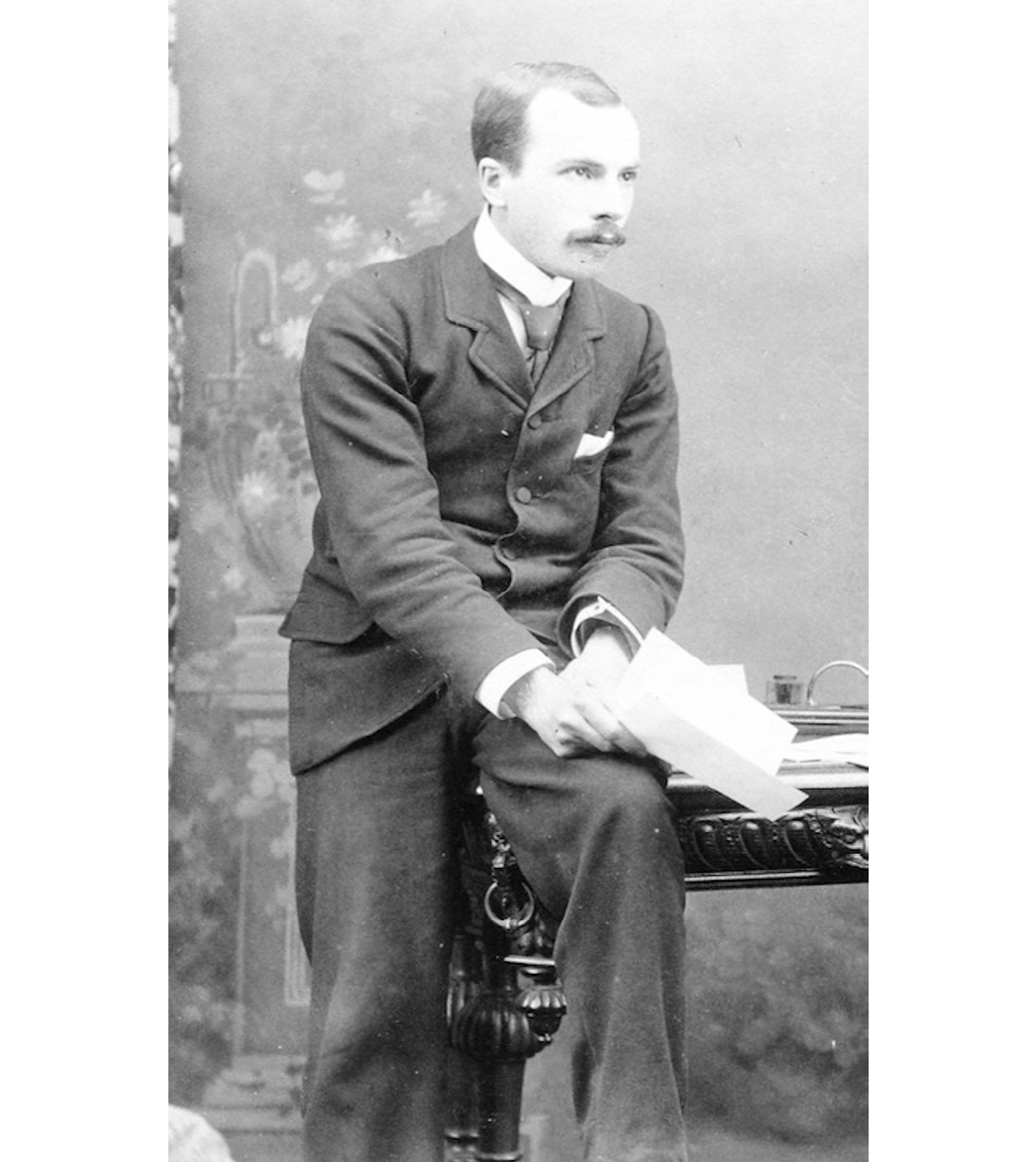

This principle was embodied in the way he worked. Design jottings from this period include many sketches of decorated shapes, the relationship of form and ornament clearly more important at this stage than the detail of the ornament itself which is often indicated in its simplest outlines. The same is true of many surviving sketches in watercolour.

Fig. 8 William Moorcroft, Experiments in the harmony of form and ornament. Vase with Violets and Butterflies (c.1900), 22cm; Urn with Narcissus (c.1900), 21cm; Knopped vase with Daisy and Cornflower (c.1898), 16cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 9 William Moorcroft, Early design sketches, including versions of the Narcissus urn and Peacock sleeve vase illustrated in Figs 8 and 7 above. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Indeed, the numbers written on the base of his pots in the early years, all prefixed by the letter M (for Moorcroft), often indicated the unity of a given pattern on a given shape, inseparable from each other in the one defining, individual reference.

Fig. 10 William Moorcroft, Base of vase with gilded floral motifs (Fig. 5 above), showing incised initials, M number, and the Florian Ware stamp. CC BY-NC

This integrated conception of design was clearly reflected in his work. Formal academic training as practised in South Kensington consisted largely in learning the principles of ornament, tried and tested in the past; design was seen as a skill to be mastered, not to be re-invented, and certainly not as a vehicle for individuality. Ralph Wornum’s Analysis of Ornament, a central part of the official syllabus, was categorical: ‘We have not now to create Ornamental Art, but to learn it; it was established in all essentials long ago’.16 Moorcroft, however, took inspiration as much from nature as from museums, adapting the organic growth of plants to the curves and contours of a thrown pot. The first Florian designs were registered in September and October 1898, the registration number referring to particular flowers or combinations: violets, dianthus, cornflower and butterflies, poppy, iris, forget-me-nots and butterflies. What these numbers did not indicate, however, was the extensive variety in Moorcroft’s adaptations of each motif. Just as he was free to modify his shapes at will, so too, without the constraint of transfers, he could vary the decorations he created. Retail orders specified ‘Florian’, but never a particular flower or pattern; the selection was very often left, and explicitly so, to Moorcroft himself. This was a living range, rarely repetitive, always fresh; to order ‘Florian’ was to order the product of a particular moment’s inspiration, and this is what was despatched.

This individuality of design was both preserved and accentuated by his method of transferring the pattern to each pot. Pottery decoration was traditionally applied either with prints, by moulding, or by freehand drawing; Gesso Faience had used the technique of stencilling, the surround of the stencilled pattern acting as a resist to the applied layer of coloured slip. Moorcroft’s method, though, was quite different. He personally drew the decoration directly on each different shape, after which a tracing was made of it, divided into sections, which was used to apply the outline of the pattern onto each pot; decorators (known as tube-liners) then followed this outline with a thin line of slip. The creation of a tracing meant that each individual decoration could be reproduced more faithfully than freehand copying would do. And yet this process was not mechanical; each act of tracing and tube-lining was inevitably unique, each piece was re-created afresh.

|

|

Fig. 11 Variations on the Poppy motif, dated (in Moorcroft’s hand) between August and November 1899. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Fig. 12 William Moorcroft, Vase with Poppy design (c.1900), 14cm. CC BY-NC

There was scope, too, for the paintresses to display their skills. The different areas or compartments were not simply filled with flat colour, but were treated in lighter or darker washes, or with dabs of different colours, added at the decorator’s discretion. This was no automatic exercise, but required the sensitivity and technique of a watercolourist, who could make her own individual contribution to the pot. It was all the more skilful, given that the paintress was working with oxides, not with enamels; the final colours would only emerge after firing, both in the biscuit oven and in the glost kiln. This method of production preserved the integrity of the designer’s vision, but it enabled the creative contribution of thrower and turner, tube liner and paintress to the realisation of each piece. Each pot was the collaborative rendition of a design, but it was also, always, individual, the exact replica of none other.

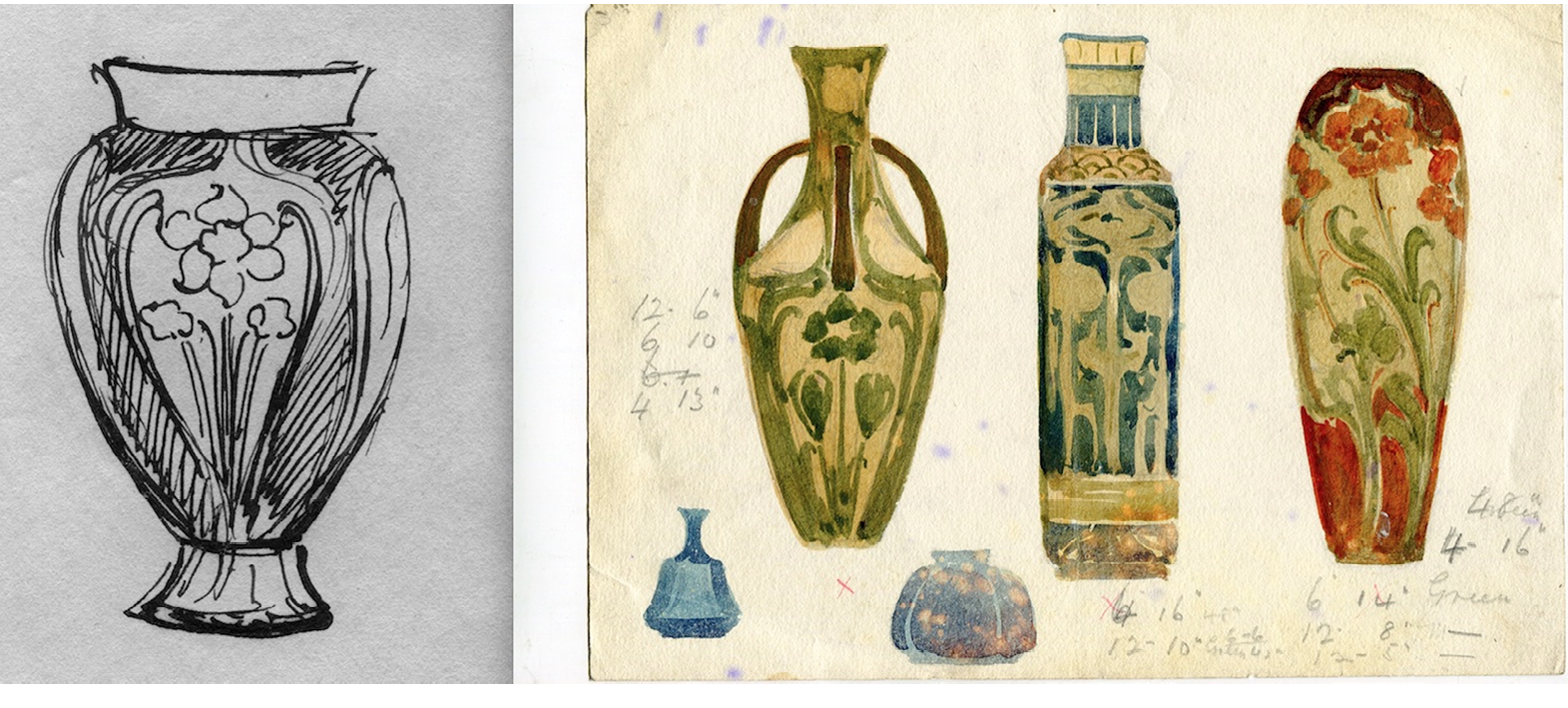

What is striking, though, is that Moorcroft signed or initialled the ware produced in his new department, in some cases discreetly incised, but most often written plainly on the base, W. Moorcroft (or W.M.) des.

Fig. 13 Early examples of Moorcroft’s signature or Initials. CC BY-NC

He was identifying himself as the designer, but he was identifying himself, too, with each particular article. For Moorcroft, design was not about the creation of a template, but about the realisation of an object, each one unique. In his own department, he oversaw production of each piece from clay to kiln, and it was to each one that he put his name, literally, affirming his presence at the end of the process as at the beginning. It is doubtless for this reason that Aurelian ware, decorated by transfers taken from his designs, but created in a different department and finished with enamel colours, was not signed by him; he may have designed the ornament, but he had little or no hand in its manufacture, each example more or less identical to the last. Not so Florian ware, which in its individuality, integrity and quality of production, stood out from other contemporary forms of art pottery. It would not be long before this was noticed.

5. Public Attention

Within eighteen months of his arrival at Macintyre’s, Moorcroft was attracting the attention of the press. Shortly after the registration of his first designs in September 1898, the Pottery Gazette published a report on Macintyre’s latest display in the showroom of their London representatives; Moorcroft’s three new ranges were on show. The speed with which he had created them was in itself remarkable, but what struck the reviewer above all was the originality (and variety) of both style and technique: ‘These are entirely different styles of ornamentation, different not only from each, but also from any previous series of decoration’.17 Although not singled out explicitly, it was Florian ware which attracted particular attention, its ‘very absence of uniformity’ clearly distinguishing it from the standardised ware of industrial manufacture. Its individuality was attributed in part to the ‘free hand of the artist’, but also, significantly, to its designer, identified by name; this was not the anonymised output of a factory, but the creation of an artist:

On the occasion of our visit, Mr Moorcroft, from the works, happened to be at the London rooms. We understand that most of the designs are his. There is abundance of originality, this will be evident when we say that each piece is unique […].18

This was the first published review of Moorcroft’s work; it would not be the last. Within three months, it was the subject of an article in one of the leading art journals of the time. If the Pottery Gazette review had focussed largely, if silently, on Florian Ware, the Magazine of Art did so explicitly. Comparing it with the generality of ‘so-called “art pottery” that has almost become a term of reproach’, the critic identified in Moorcroft’s ‘ceramic art’ a distinctive ‘mark’ which set it apart and gave each piece its character and its life:

But to us, one of the most interesting features of this ware is that it bears indelibly the mark of the artist and the skilful craftsman. All the designs are the work of Mr W.R. Moorcroft; every piece is examined by him at each stage, and is revised and corrected as much as is necessary before being passed into the oven. The decorative work is executed by girls, […] and, while the design of Mr Moorcroft is followed as closely as possible, any individual touches of the operators are seldom interfered with if they tend to improvement. It thus happens that no two pieces are precisely alike.19

Each object drew its individuality from the combined sensitivities of clayworkers and decorators, working in harmony with the artist. It was the perfect collaboration of craft and art, and it could not fail to appeal:

Messrs Macintyre, who are the manufacturers, are to be congratulated on their success in placing before the public a ware that really exhibits evidences of thoughtful art and skilful craftsmanship.20

It was very gratifying for Macintyre’s to be congratulated on securing the services of an acclaimed designer, and in this particular journal. But it was a significant triumph, too, for Moorcroft, prominently identified as the originator of this ware.

6. Commercial Promise

The display at Macintyre’s London showroom attracted considerable attention from retailers, including some of the most prestigious of the age. One of Moorcroft’s notebooks from 1898 recorded contact with Thomas Goode & Co., London’s foremost tableware dealer which counted Queen Victoria and the Tsar of Russia among its customers: ‘They will be glad to receive a lot sufficient to make a show, and promise to make a very attractive display, and further promise repeat orders’. An entry in another notebook listed a meeting on 18 October 1898 with Alwyn Lasenby, a Director of Liberty & Co., the same month as the Pottery Gazette review of Macintyre’s London display. Liberty’s was one of the country’s most influential and fashionable stores, commissioning and retailing work by progressive designers. They were clearly promoting art pottery at this time, announcing their ‘representative and extensive Collection of English Art Potteries’ in a full page advertisement placed in the Magazine of Art, November 1896. To be retailed by Liberty’s was to be at the forefront of elegance, style and modernity. A letter of 24 May 1899 indicates an increasingly close collaboration with Lasenby:

Mr Lasenby is attracted by the rough sketches you forwarded for him to see, and is of opinion that if you produce a few examples on the lines of those he has marked with a red cross (X), he can then better judge their merits, and would be pleased to discuss same with you.

Within two years, Moorcroft had developed an association, both commercial and personal, which would be one of the closest and most creative of his professional life.21

But Moorcroft’s work also caught the attention of an international market, and at the highest level. An early notebook records ‘sample vases’ prepared for Tiffany & Co. of New York, jeweller to royal families throughout Europe and beyond, and purveyors of luxury goods to some of the most illustrious families in the US, from the Astors to the Vanderbilts. By 1900, this relationship, too, was flourishing. Moorcroft’s diary noted a visit in April from Arthur Veel Rose, Tiffany’s chief buyer for pottery and porcelain, and a notebook from the same year records further collaborations based on new, bespoke designs for lamps and vases. And he was being noticed, too, in France. He accompanied Watkin to the Exposition Universelle of 1900, which defined a vibrant new style for the new century, epitomised by the flowing lines of Guimard’s Métro entrances or Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine dance. Macintyre’s had no display at the Exhibition, but Moorcroft, with the firm’s support, was taking every opportunity to promote his own designs. His diary for 1900 recorded visits to some of the leading decorative arts galleries of the time: Emile Bourgeois, whose luxurious Grand Dépot catered for the taste of a fashionable elite; Georges Rouard’s gallery, A la Paix, which became a centre for art nouveau decorative arts in France; Louis Damon, artist and entrepreneur, whose gallery, ‘Au vase étrusque’, stocked the finest work of Gallé, Daum and other leading decorative artists; and Clain & Perrier, whose studio gallery also promoted the work of Daum and Gallé. To do so was a sign of his confidence in the distinctive quality of his own art; that confidence was well-founded, and it was shared. A Directors’ meeting on 5 November 1900 recorded high hopes for Moorcroft’s decorative ware, and there was clearly a desire to encourage him:

It was reported that the Managing Director, accompanied by Mr Moorcroft, designer, paid a visit to the Paris Exhibition during the last week in October. With the Florian ware, 5 calls resulted in opening accounts with 5 of the best Houses in Paris, and there appears every reason to suppose an important fancy trade can be cultivated. A visit once a year by the designer would probably be a good investment, directly and indirectly.

This widespread appreciation of Moorcroft’s ware coincided with a steady improvement in Macintyre’s sales performance. Receipts in 1897–98 rose by nearly 40% on the previous year, and this progress continued during 1898–99, with a Minute of 30 January 1899 recording ‘gratification […] at the continued increase in the sales’. These figures covered the sales of the firm as a whole, but it is clear that the Directors recognised the contribution made by Moorcroft, both in terms of what he produced and of his active role in marketing it. At the same meeting of 30 January 1899, Moorcroft’s salary was increased by ten shillings per week. Orders were flowing in, and the Directors were very aware of the need to increase output. On 3 February 1899, steps were taken to expand the factory space devoted to production of this ware, and three months later, on 8 May 1899, Moorcroft’s appointment was renewed ‘at a remuneration of £3/10 (three pounds and ten shillings) per week’. In the course of two years, his pay had risen by nearly 40% to £182 p.a., much closer to the salary of £220 initially earned by Barnard; and Moorcroft was considerably younger. For all the range of Macintyre’s production, it was Florian ware which attracted the public’s attention and fuelled orders; the Directors clearly recognised this with gratitude. On 12 June 1899, little more than five weeks after his re-appointment on an increased salary, they approved another remuneration of Moorcroft’s success with sales: ‘a commission of 1% upon gross sales from his department, to date from January 1st 1900’. Throughout 1899, Minutes recorded the success of Florian and its consequences for the firm. Within a year of his appointment to direct the design and production of ornamental ware, Moorcroft had contributed to a quite exceptional rise in Macintyre’s turnover; his art pottery was making its presence felt, on the factory floor as well as on the balance sheet. The need for more employees and more space continually increased, to the extent that, on 13 July 1899, the Directors decided to limit its promotion in new markets abroad until the firm was in a position to meet the expected demand. At this same meeting, sales for the year-end 1898–99 were recorded as £34,376, a further increase of 13%. Florian ware had taken Macintyre’s by storm.

The firm was now enjoying great commercial success. A schedule of outturns since the formation of the limited company in 1893 listed deficits of £2,125, £664 and £1,972 in the years 1894–95 to 1896–97; in the following two years, however, profits were recorded of £304 and £2,484. And this pattern continued. On 10 December 1900, a Minute reported ‘the most successful year’s trading since the formation of the Company’, adding that the Directors had ‘every reason to believe the current year will be equally prosperous’. Such success was spectacular; it was also exceptional. In the Pottery Gazette, Louis Bilton, a decorator at Doulton Burslem since 1892, commented on the commercial gamble which was art pottery:

The production of artistic pottery, apart from absolute utility, has almost always proved a hazardous enterprise. Even when encouraged by Government patronage and subsidies, as in France, it has rarely succeeded financially for a lengthened period. […] Art industries should stand or fall on their own merits, artistic and financial alike.22

It is certainly the case that by the end of the century the market for art wares was reducing. Two years after Henry Doulton’s death in 1897, his son turned the firm into a Limited Company; in 1898, Halsey Ricardo dissolved his partnership with William de Morgan, as the firm’s financial difficulties increased; and in 1900, the six-year old Della Robbia factory merged with a religious statuary firm, run by Emile de Caluwe (a Belgian sculptor), in a bid to balance its books. Macintyre’s had taken that gamble, however, and Moorcroft had produced a ware which brought them a financial return on their act of faith. Florian was work of truly distinctive quality, and it was being singled out, rapidly and at the highest level, in both the art and the trade press, and in countries which were acknowledged leaders in the world of decorative arts, France and the US. In his prize-giving address at the Wedgwood Institute in 1895, Taylor had stressed the economic and artistic importance of encouraging creative design:

You must give opportunity for the growth in your midst of a free artistic spirit, which shall primarily make those possessing it, whether manufacturers or workmen, better men and better workmen, each having the opportunity for developing his own individuality and its expression, and these conditions are most conducive to the best interests of both capital and labour.23

Woodall and his Directors had recognised this ‘free artistic spirit’ in Moorcroft; as a new century dawned, the future looked promising indeed.

7. Conclusions

Moorcroft’s career as a potter could not have had a more auspicious start. Macintyre’s encouragement of his creativity was characteristic of a firm which was, in its own way, individual and forward-looking. Promoting the values of handwork, its art pottery department was creating wares which were immediately recognised as different from the uniform products of a factory. But at the same time, it was avoiding the increasingly evident failures of many enterprises inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, which seemed destined to produce unaffordable luxuries, ‘art for a few’,24 a position which Morris had repudiated. Moorcroft’s ware had the individual quality of exclusive objects, but their method of production allowed for more numerous, more varied and less expensive wares; it did not depend on the skill of a single artist-craftsman, but was adapted to serial production. Florian was retailed by some of the most prestigious and fashionable outlets throughout the world, but it was not simply bought by a privileged elite; it sold to a wider public, and it sold well. It was the perfect integration of art and industry.

It is significant too that, in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement, Macintyre’s were ready to identify their designer as the originator of his wares. Less than ten years since the first exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, this was still an uncommon (and enlightened) position, as Crane implied in his article ‘Of the Arts and Crafts Movement’. What he said about the artisan applied equally to the designer:

It is to the commercial interest of the firm to be known as the producer of the work, and it must be therefore out of good nature or sense of fairness, or desire to conform to our conditions, when the name of the actual workman is given […].25

Macintyre’s did not exhibit at Arts and Crafts exhibitions, but their sanctioning of Moorcroft’s signature, an indelible feature of each object he produced, was a telling sign of their appreciation of his art and of their confidence in him. No such privilege had been accorded to Barnard. And this suited Moorcroft perfectly, for his was a very individual art. Florian was created at a time when British ceramic design was seen to have lost its way, perceived as historicist, derivative, ‘at the mercy of every wind of fashion that blows’.26 Critics, and the public, doubtless appreciated Moorcroft’s implied allusion to an English decorative tradition long since lost, a modern, refined variant on the old slip-decorated pottery of the pre-Wedgwood age, with a much more sophisticated use of colour. If the sinuous sensuality of art nouveau was too extravagant and ornamental for British taste, little more than ‘wild and whirling squirms’27 in Crane’s uncompromising evaluation, Moorcroft’s designs were more restrained in their treatment of natural motifs.

But what distinguished this work above all was its personal quality, that distinctive ‘mark’ discerned by the Magazine of Art in 1899. In notes dating to 1900, Moorcroft reflected on the affective nature of design, both the creator’s emotional investment in it and its impact on the observer:

[…] we 20th century potters must be careful to put in our work our own thoughts and emotions, and do our share in building up our civilisation. There is no craft that will be more likely to do this than the art of the potter.

From the very start of his career, Moorcroft conceived pottery as a form of personal language. As he looked back less than six years later to the start of his career at Macintyre’s, he evoked his ambition as an artist and its early fulfilment at the Washington Works:

It was after long dreaming of what was possible in this direction, that in 1898 I was first able to express my own feeling in clay.28

This was not the kind of vocabulary to be found in theoretical or practical manuals of design, but it would be the foundation and driving force of Moorcroft’s career as a potter.

1 ‘Potters of Today. No.9 Mr W. Moorcroft’, Pottery and Glass Record [PGR] (1923), 656–58 (p.657).

2 Wedgwood Institute Burslem: Schools of Science, Art and Technology, Twenty-seventh Annual Meeting, 13 March 1895, p.2.

3 Ibid., p.12.

4 Walter Crane, An Artist’s Reminiscences (London: Methuen, 1907), p.457.

5 Louis Bilton, ‘Some notes on the decoration of pottery’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (February 1900), 205–07 (p.207).

6 Wording of the presentation recorded in the Minutes of a Directors’ meeting, James Macintyre & Co. Ltd (8 May 1899). Unless otherwise indicated, all unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

7 F. Miller described ‘a form of decoration suggestive of sugar-icing to cakes produced by squeezing slips out of a tube’ (‘Doulton’s Lambeth Art Potteries’, The Art Journal [AJ] (1902)), 50–53 (p.51).

8 H. Barnard, ‘Personal Record’, unpublished memoir, p.34 [I am most grateful to Mrs Maureen Leese for allowing me to consult her copy of this document].

9 M.L.E. Solon, ‘Pâte-sur-Pâte’, AJ (1901), 73–79 (p.78).

10 W. Burton, ‘Material and Design in Pottery’, PG (January 1898), 104–07 (p.107).

11 W. Burton, ‘The Palette of the Potter’, PG (July 1900), 805–07 (p.805).

12 W. Burton, ‘The Palette of the Potter’, PG (June 1900), 689–92 (p.690).

13 ‘Science in Ceramics’, PG (November 1897), 1428–29 (p.1428).

14 ‘Something New and Beautiful’, PG (February 1899), 194–95 (p.194).

15 Ibid.

16 R.N. Wornum, Analysis of Ornament [1860]; 3rd edition (London: Chapman & Hall, 1869), p.21.

17 PG (October 1898), p.1248.

18 Ibid.

19 ‘Florian Ware’, Magazine of Art (March 1899), 232–34 (p.233).

20 Ibid., p.234.

21 Alwyn Ernest Lasenby was the cousin of Arthur Lasenby Liberty, founder of the store (Lasenby’s father and Liberty’s mother were siblings). Some studies of Moorcroft erroneously state that his friendship was with the latter, not the former.

22 Louis Bilton, ‘Some notes on the decoration of pottery’, PG (February 1900), 205–07 (p.207).

23 Wedgwood Institute Burslem: Schools of Science, Art and Technology, Twenty-seventh Annual Meeting, 13 March 1895, p.13.

24 W. Morris, ‘The Lesser Arts’ [1877], in The Collected Works of William Morris, XXII (London: Longmans, 1914), 3–27 (p.26).

25 W. Crane, ‘Of the Arts and Crafts Movement’, Ideals in Art (London: George Bell & Sons, 1905), 1–34 (p.23).

26 ‘Something New and Beautiful’, PG (February 1899), 194–95 (p.194).

27 Crane, ‘Thoughts on House Decoration’, Ideals in Art, 110–170 (p.128).

28 F. Miller, ‘The Art Pottery of Mr W. Moorcroft’, AJ (1903), 57–58 (p.57).