11. 1929–31: No Ordinary Potter

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.11

1. A Creative Response to the Depression

Moorcroft’s Royal Warrant could not have been awarded at a more challenging economic moment. The pottery industry was struggling to compete with cheap wares produced in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Japan, unemployment was high, and firms were facing closure. The Pottery Gazette captured the prevailing mood of despondency among manufacturers ‘beginning to speculate as to whether […] a renewed bout of prosperity will ever come their way’.1 And worse was to come. The Wall Street crash of October 1929 caused a global collapse, and a year later the Depression had become more than just an economic metaphor: ‘morbid depression has become almost an epidemic in North Staffordshire’.2 The Pottery Gazette of June 1931 published statistics which brought home the extent of the decline: in the three years since 1929, unemployment had very nearly trebled. Increased output and reduction of costs (including cuts in workers’ wages) were ‘imperative’ if factories were to remain in business.3

In response to these growing economic pressures, Moorcroft continued to experiment and innovate. The Pottery Gazette underlined the originality of his exhibit at the 1929 British Industries Fair [BIF], his first since the award of the Royal Warrant:

How Mr Moorcroft manages to keep on adding triumphs to his long list of past achievements, one really cannot explain, except that he is, by nature, a creative potter, whose mind is never content unless it is evolving something new, something better.4

It is significant that the review did not situate Moorcroft’s display in the context of contemporary industrial pottery, but evaluated it against different standards: his own. He continued to attract attention for his skill as a potter, creating glaze effects of the highest quality. In an article entitled ‘An Art Achievement in Pottery’, a critic drew attention to a highly publicised appraisal of his latest work:

The most interesting art event of the week at the British Industries Fair was the tribute paid by the Official Lecturer on Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, who described a Moorcroft peach bloom vase as the greatest achievement in modern pottery. […] The tribute is not surprising […]. Moorcroft pottery stands supreme as being not only comparable in beauty to the finest examples of the past, but with the added virtue that it is entirely modern in inspiration and execution.5

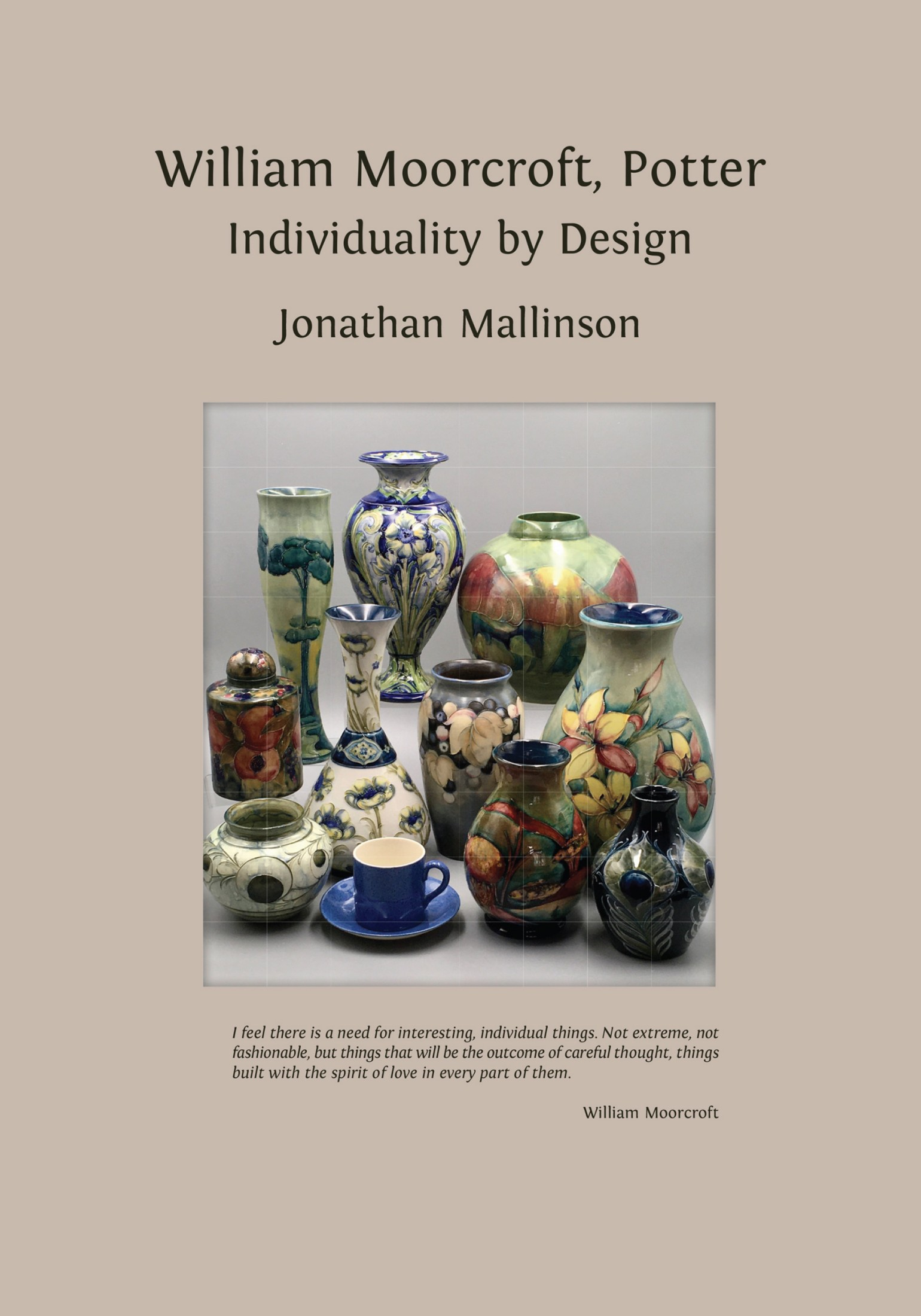

Fig. 86 Moorcroft’s stand at the 1929 British Industries Fair. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Fig. 87 William Moorcroft, New designs in grey and fawn, with matt glaze: Fish (1931), 20cm; Poppy (1931), 11cm; Landscape (1931), 23cm; Leaf and Berries (1931), 17.5cm. CC BY-NC

This phase of creativity culminated in his exhibit at the 1931 BIF, particularly notable for its range of new, non-floral designs, featuring landscapes, fish, and leaf and berry motifs, each presented in different tones. The Pottery and Glass Record commented particularly on his new matt effects, setting them in the context of pre-industrial pottery:

Very interesting was the revival of the use of salt glaze by Mr William Moorcroft, this being a method of glazing which made Staffordshire pottery famous in the 18th century all over the world. But, indeed, the whole Moorcroft exhibit this year was strikingly fresh—still typically Moorcroft, but quite different, in the predominating colours of the ware […], from the display last year. […] Then, instead of the rich reds of last year, the prevailing colours were different shades of grey, blue, jade green and yellow […].6

These consciously muted tones stood in sharp contrast to the predominantly bright colours in much industrial production, and brought him closer to the more ‘sober’ palette of Shoji Hamada, ‘ranging through brown, russet and grey to a grey-blue of beautiful reserved quality’, in his 1929 exhibition at the Paterson Gallery.7

Indeed, as so often before, Moorcroft’s stand at the British Industries Fair had the status, and impact, of an artist’s exhibition, attracting high-profile attention. The unsourced review listed visitors to his stand in 1929, including two serving Cabinet ministers and the wife of the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin:

This year the exhibit contained many new objects which were admired by thousands of visitors. The Queen […] visited the stand and purchased two vases and a jar, and as Her Majesty is recognised as a connoisseur the world over, this fact speaks for itself. The stand was also visited by the Prince of Wales, Prince George, Mrs Baldwin, Sir W. Joynson-Hicks, Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland, and the Brazilian Ambassador.

It was the same story the following year. What caught the attention of the press was not the appeal of his pottery to commercial clients, but its appreciation by prominent figures coming to applaud him:

Mr Moorcroft was, according to his custom, personally in attendance, and a busy man he was, for one after another, visitors of note called upon him, usually to express their congratulations upon his achievements. […] Another distinguished visitor to the stand was the Prime Minister, Mr Ramsay MacDonald, who, though he confessed to being a busy man, said he would like to know something as to the methods by which Mr Moorcroft’s charming decorative effects were secured in rouge flambé and other individualistic styles.8

This was a moment of particular significance, being the first visit to the Fair of a serving Prime Minister since its inception in 1915. Such was Moorcroft’s prestige that appreciation of his ware had become an indicator of fine judgement.

Moorcroft was clearly seen as an artist potter, his ceramic skills and aesthetic sensibilities drawing the attention of critics. After the 1929 BIF, he sent a vase to T. Frederic Wilson, the lecturer at the Victoria and Albert Museum [V&A] whose accolade had attracted press attention. Wilson’s reply, dated 1 May 1929, confirmed the impact his pottery was having in ‘the world of art’: ‘I am giving an ‘At Home’ to a few who really matter in the world of art and reason next Tuesday ‘To meet a Vase’. With very kind thoughts.’9 And a review of his exhibit at the 1930 BIF focussed particularly on its distinctiveness:

If, however, Mr Moorcroft never evolved anything in pottery beyond what is represented by his present achievements he would, at least, have the satisfaction of knowing that he has proved how pottery, as a plastic medium, can be used to express the finer susceptibilities, just as literature or poetry is chosen by some to attain the same ends. Moorcroft pottery is no ordinary pottery; it stands in a class by itself and has to be viewed from that standpoint.10

Moorcroft’s pottery was seen to have the expressive quality of art; it was a judgement very similar to that of Charles Marriott in a review of William Staite Murray’s work:

[…] Mr Murray has now made of pottery a complete form of emotional expression […]. Each of his pots, vases, bowls or dishes is moulded to a mood, none the less real for being indescribable in words […].11

Moorcroft’s Royal Warrant was seen to confirm this status. If Moorcroft was no ordinary potter, the Queen was no ordinary patron; royal approbation was rare, and was awarded only to work of exceptional quality. An article entitled ‘The Queen’s Potter’ summarised this sequence, excellence followed by recognition:

Mr William Moorcroft, who owns a small one-man factory at Burslem, near here, is spoken of in the Potteries as the world’s master potter. Experts say that for beauty and distinctiveness, Mr Moorcroft’s work approaches the brilliant products of the ancient Chinese. The Queen has bought dozens of pieces of his work, and has bestowed the honour of ‘Potter to the Queen’ on him.12

And the qualities recognised by Queen Mary were clearly appreciated, too, the world over; Moorcroft was an artist potter whose work was commanding the highest sums: ‘Members of Royal Families in Europe and American millionaires are his chief customers. Yearly he sends thousands of pounds’ worth of his china to the Far East.’13

But what continued to be stressed in reviews was that Moorcroft’s output appealed to more than wealthy connoisseurs alone, and that it was affordable by more than a narrow elite. His best pottery was fit for the finest collections, but the same qualities were recognised too in his functional ware or more modest decorative pieces. A review of his work in the Woman’s Pictorial moved seamlessly from one to the other:

Experts have said that there are pieces in this ware which rival the early Chinese work for which fabulous sums are paid. There is nothing more lovely in the home than a Moorcroft dessert set. The colouring is marvellous. As the Queen said when she purchased a vase: ‘The blue is the colour of a raven’s wing’, and the colour of the fruit in the pattern is the work of an artist.14

This consistent quality underlay the appeal of Moorcroft’s work to a distinctively broad range of potential buyers, from those seeking objects to treasure to those seeking items to use. Written just weeks after Leach’s ‘A Potter’s Outlook’, this endorsement had particular resonance; this was not just pottery for the museum, it was art for the home. The practicality of his ware was emphasised, too, in The Industrial World, February 1929:

Moorcroft pottery is designed for use, and not merely for ornament. It is astonishingly durable, and is admirably adapted for everyday use in the home, the cups and saucers in deep lapis lazuli blue being particularly attractive against the background of a dark oak table. Bowls and vases of Moorcroft pottery, filled with flowers, bring gaiety and life to any room […].15

What attracted particular attention at the 1931 BIF was Moorcroft’s launch of decorated dinner ware, enthusiastically welcomed in the press for its ‘sound craftsmanship and high artistry’.16 Characteristically, this was tableware quite like no other. Moorcroft did not simply apply floral motifs to white ware, nor did he adopt the increasingly popular style of banded decoration; instead he created a complete integration of colour and ornament.17 And its appeal was widespread. If it won public approval in the Staffordshire press, it was no less warmly appreciated in London circles. Writing to Moorcroft on 12 March 1931, Edith Harcourt-Smith conveyed the enthusiastic appreciation of the Japanese Ambassador: ‘The Ambassador […] adored the autumn dinner service! […] He bought, he told me, some of those dessert plates you gave me—dark blue with coloured fruits, which he thought marvellous, as we do!’

As debate continued about how best to improve the design of functional objects, Moorcroft’s ware was regularly highlighted. His was pottery which brought pleasure, both in use and as an object of contemplation. An article in Town and Country News made just this point:

The renaissance of English ceramics owes much to the genius of W. Moorcroft, a potter who has succeeded in striking a happy compromise between the manufacturing needs of today and the claims of art. In this compromise, the claims of art have been superior; it is no mere figure of speech that Moorcroft pottery will be valued by future generations as typical of the finest ceramic art of the early twentieth century.18

Marfield’s emphasis was significant. Moorcroft’s functional objects were seen to be the creation of an artist potter, and their unique appeal derived from that. Viewed from this perspective, it meant that all of his pieces could be considered artworks, as was suggested in the Pottery and Glass Record review of his exhibit at the 1929 BIF:

What distinguishes a display of Moorcroft pottery is that there is never a piece among it which is not truly beautiful. […] This is another way of saying what has often been said that ‘every piece of Moorcroft pottery is a collector’s piece’.19

And for some owners, Moorcroft’s pottery was not simply an object of collection, it had a defining role in their domestic surroundings; the article in The Industrial World suggested that it was often the centrepiece of a room, ‘the key note of a whole scheme of decoration.20 And this was no simple figure of speech. It was a transformative effect expressed, too, in Wilson’s thank-you note to Moorcroft of 1 May 1929: ‘I have had to change the colour of my walls and paint to harmonise with the vase, the more I see of it, the more it grows on me.’ And for one, the appeal extended further still. In a letter to his daughter, Beatrice, on 29 November 1931, Moorcroft recounted one customer’s exultant reaction to a piece of his ware; it was more than a decorative object, it was the foundation of her well-being. A rhetorical flourish, of course, but eloquent nonetheless: ‘A visitor from Australia told her husband that she would prefer to live in an orange box with a piece of Moorcroft than to be without it.’

For many critics, Moorcroft’s ware could not fail to weather the economic storm. It was affordable by more than just collectors of ceramic art, and its appeal was evidently increased by the Queen’s high-profile patronage. When the Canadian paper The Morning Post reported on the strategies of one buyer visiting the 1931 BIF, it was taken as self-evident that a royal purchase conferred ‘added value in the eyes of her American customers’; for this reason, ‘this clever Canadian buyer was careful to buy […] Moorcroft pottery with the new fish pattern.21 And an article in Public Opinion referred to royal purchases of Moorcroft ware as an inducement to buy with confidence; there could be no better, nor more attainable, aspiration than to show the same taste as the Queen:

Wherever it has been shown, Moorcroft pottery has won the highest praise from connoisseurs. Mr Moorcroft was some years ago appointed potter to the Queen, and her Majesty, whose judgement and taste in such matters is well known, has repeatedly purchased pieces. Those who give Moorcroft pottery this Christmas may be sure that the friends will possess perfect specimens of British craftsmanship at its best.22

Moorcroft’s distinctive blend of art and functionality was widely recognised, both at a local and a national level. In a letter to Moorcroft of 6 May 1931, Sir Francis Joseph, chair of the Staffordshire Chamber of Commerce, expressed ‘the indebtedness to yourself of the district for the lifting and making of earthenware from mere utility to an enviable level of artistic merit’, and on 5 June 1931, he was invited by Hubert Llewellyn Smith to become a Fellow of the British Institute of Industrial Art [BIIA]. The appeal of his ware was seemingly irresistible. So much so that the article in Public Opinion openly re-appropriated Wilson’s praise of Moorcroft’s technical and artistic achievements, using it now as a comment on their commercial potential: ‘Moorcroft pottery is one of the great achievements of modern British industry’.23 The reality, though, was not quite so simple.

2. Art and Commerce

For all that Moorcroft’s pottery was widely appreciated, this did not translate effortlessly into profitable trading in the deteriorating economic conditions. Nevertheless, at the end of his first full year as the Queen’s potter (1928–29), he recorded a profit of just over £518, overturning the significant loss of the previous year. Sales had increased by 6.2%, but money owed from unpaid invoices had risen by nearly 15%, and Moorcroft found himself operating on a steadily increasing overdraft. Throughout the following year, he worked actively to promote his ware. In the wake of the Wall Street crash of 29 October 1929, many firms were absent from the British Industries Fair which was moved in 1930 to the newly built Empire Hall at Olympia. Moorcroft, however, adopted the opposite strategy, reserving a site of particular prominence at the new venue. He worked to develop his position, too, in the European market, exhibiting at the Leipzig Trade Fair, although, as reported in the Pottery Gazette, the commercial benefits were ‘generally poor’.24 And he took positive steps to control the steep decline in his US sales, which had fallen by 33% from 1928 to 1929.25 Within months of the Wall Street crash, he tried to circumvent the prohibitive duties on imported goods, arguing in a letter to the United States Treasury Department that his wares should qualify for the exemption accorded to works of art. But what US customs understood by art was clearly different from Moorcroft’s conception of the term (and that of many reviewers of his work). A reply, dated 1 March 1930, quoted a ruling of the United States Court of Customs Appeals; a defining characteristic of an art work was deemed to be non-functionality, excluding at a stroke so much of Moorcroft’s pottery. Ironically, if Moorcroft had wished to reduce the price of his export wares, he would have needed to deny their ‘utilitarian purpose’, the very quality which gave his work its broad appeal. But there was still clearly a market for his ware in the US. A letter from an importer, Roy Treloar, dated 21 March 1930, expressed confidence that ‘a big business can be done in the States’, and so it proved. Moorcroft’s year-end outcome was a loss of just £20; in the year following the collapse of the US market, this was a remarkable result.

But it was not to last. Trading conditions were stifling, orders were falling, and his bank deficit increasing to alarming levels. Loeffler Inc., a firm of New York importers, wrote on 29 January 1931, describing a market now completely governed by price:

I am sorry to say conditions are terrible here, and there is no improvement at all. Christmas trade was very bad all around, […] and since Christmas there are sales everywhere of pottery and china etc, which makes it very difficult indeed to sell expensive and exclusive articles such as yours. We are passing through one of the worst crises in the history of this country.

Pressure was increasing to cut back his costs, but Moorcroft would only go so far. His innovative exhibit at the 1931 BIF was a defiant demonstration of his commitment both to his design and production principles, and to his workforce. But by the end of the financial year sales had fallen by nearly 40%, and he was left with his third loss in four years. He had reduced the level of money owed by 30%, but it was still a very significant sum: without it, his sales income would have increased by nearly 50%, turning the eventual deficit of £2,201 into a profit of almost equivalent size. By the start of the new financial year, the firm’s overdraft had exceeded the £2,000 limit agreed with the Bank. Moorcroft wrote on 31 August 1931, explaining that the deficit was the result of unpaid accounts and his own efforts to protect the jobs of his staff. But it was a losing battle. As sales fell in the course of the year, the prospect of redundancies loomed larger; he wrote gloomily to Beatrice on 4 June 1931:

The effect of the world’s trade depression appears to be more and more far-reaching. […] We are feeling it just now on the works, and it is a problem how to keep everyone fully employed, a big problem.

By early September, concessions had become inevitable; it was a painful blow, as a letter from Edith Harcourt Smith on 9 September 1931 made plain: ‘How could you help allowing your men to go on the dole! Impossible. You made superhuman efforts to prevent it, yet there comes a time when one must give in, much as one objects.’

But this was not the only concession Moorcroft had to make to the economic pressures. As the Bank sought additional financial guarantees against its loan, Moorcroft was faced with a stark choice: to use the deeds of his works as security, or to reduce the overdraft. On 12 November 1931, he wrote to Liberty’s, expressing confidence that trade was now improving, and sales did indeed rise; by 31 December 1931, income was very nearly 50% higher than the year-to-date figure a year earlier. But these improved figures were not the result of a change in the economic climate, quite the reverse; Moorcroft had just sold a large quantity of his imperfect stock to Eaton’s at a heavily discounted rate.

Fig. 88 Advertisement for sale of Moorcroft’s pottery, Toronto Daily Star (7 December 1931). ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

The benefit to the balance sheet was immediate, but it was an act of desperation. In 1929, an article published in the Sunday Dispatch presented Moorcroft as one whose commitment to quality outweighed purely commercial motives: ‘if he had made money his god, he could have accumulated a great fortune.’26 A manufacturer might judge the success of his work with reference to his sales, but Moorcroft was seen to have quite different criteria, uncompromisingly expressed in his own words; the ultimate arbiter of value was not the public, but he himself:

My work is the revelation of what I consider to be beauty. To get the desired colouring effects, I have to be most careful in watching the temperature of the ovens, and the running of one colour into another. If the result is not as I wish, the pottery is useless to me and is laid aside.27

But as commercial pressures increased, it was more and more difficult to justify setting aside imperfect pieces which might be sold at reduced prices, still less those which, to other eyes, might have seemed without flaw. In 1929, this was precisely what Moorcroft had been doing:

Mr Moorcroft showed me four rooms stacked ceiling high with beautiful pieces of china, but to him they were only so much waste. Either in the colouring or design there was a fault in each, although it would need the eye of an expert to discover it.28

By the end of 1931, however, he could do so no longer. Wares he had described two years earlier as ‘useless’ and unsuitable for sale, he must now accept as a marketable commodity; commercial necessity had finally overridden his artistic ideals. But his reluctance was clear. Writing to Beatrice on 6 November 1931, he revealed that he had, as always, overseen what left the factory; even in these conditions, there were limits to what he would countenance being sold in his name:

I determined to dispose of a lot of pottery, some thousands of pieces, and the packing out of this has been a great strain. Each piece had to finally pass my supervision. That is apart from the fact that each piece had passed through my hands at an early stage.

Worsening trading conditions underlined the fact that Britain needed both cheaper products and better design to compete in the world markets. In 1929, just weeks after the Wall Street crash, the BIIA held an exhibition of Industrial Art for the Slender Purse at the V&A; price took its place alongside design as a criterion of value. Its aim, quoted in The Times, was ‘to give practical proof that beautiful things need not be costly’.29 Many manufacturers were controlling the cost of their decorated wares by adopting simple designs which could be applied freehand and at speed by teams of more or less skilled decorators; painting with on-glaze enamels facilitated the correction of mistakes and reduced the number of losses. Some firms employed art school trained designers, such as Charlotte Rhead, Clarice Cliff, or Eric Slater; another, Susie Cooper, left Gray & Co. in 1929 to set up her own factory. Many firms struggled, but the Newport Pottery was on the crest of a wave. The exuberant, innovative and affordable designs of Clarice Cliff’s Bizarre series appealed to a growing market of young post-war couples. For many, they epitomised commercial design, for better or worse; eclectic in inspiration, they were immediate in appeal, and quick and cheap to produce. The Pottery Gazette noted its remarkable success more than two years after its launch, and for all its bold extravagance:

Never before had such powerful and intensive colourings been applied en masse in flat brushwork effects. […] the designs and colourings struck one as being so unlike anything previously attempted, and so revolutionary in character as to be likely to prove short-lived. […] but experience has proved that any such fears were unfounded.30

Other firms, however, looked to fine artists. There was growing concern about the low status of the industrial designer, and a desire to encourage more artists to collaborate with industry. In the autumn of 1930, Frank Brangwyn exhibited at Pollard & Co., Oxford Street, a series of designs in pottery (made for Doulton) and other media; the event was reviewed in The Times. It was a collaboration intended to create not individual artworks, but items for industrial production:

The exhibition is modern without displaying any of the irritating qualities of much recent modern household equipment and furniture. It is strong and virile in design, and is intended for mass reproduction at a commercial price.31

For some, the most successful examples of collaboration between art and industry were to be found in Europe and Scandinavia. The Stockholm Exhibition of Arts and Crafts and Home Industries, reviewed by Marriott in an article entitled, significantly, ‘Art and the Machine’, represented the new wave in Europe, ‘the boldest and most consistent exhibition of what one is compelled to call ‘functionalist’ design in terms of its own characteristic beauty that we have yet had’.32 Marriott saw among the exhibits ‘things of quite extraordinary beauty, for daily use and at moderate prices’; these were the defining virtues of modern industrial art, identified by the organisers of the BIIA exhibition. The event inspired an exhibition of Swedish Industrial Art at Dorland Hall in 1931, which brought to prominence qualities of simplicity, functionality and easy replicability in the pottery and glass of leading designers such as Ewald Dahlskog and Simon Gate. And it underlined, yet again, the value of close collaboration between high-quality designers and enlightened manufacturers, strikingly rare in Britain. As The Times review noted:

What distinguishes the present exhibition is not so much the evidence of superior talent in design, or technical efficiency, or business enterprise as isolated factors, as the evidence of a relationship, as close as it is easy, between all three; a cheerful association of talents and experience for the common welfare.33

Later that year, Marriott was in no doubt that the best industrial pottery was currently being made in Europe and Scandinavia, not in Staffordshire:

[…] the person who wishes to obey the injunction to ‘buy British’ in factory-produced domestic wares must be prepared to sacrifice his taste in doing so. He can easily get something that is technically sound, but […] his artistic preferences would be better pleased by something from Sweden, Germany or Czechoslovakia.34

Even as economic pressures threatened to compromise the commercial success of Moorcroft’s ware, critics were reflecting on the most appropriate measure of its worth. For many, as indeed for Moorcroft himself, it was not to be found in balance sheets, although some expressed it still in monetary terms. The Overseas Daily Mail argued that his finest work would continue to appreciate in value:

Firms like the Moorcroft Potteries, who are engaged exclusively in the production of the highest quality work, can reasonably claim that […] the collectors’ pieces which are purchased from them at the present day will change hands in future generations at increasingly high figures.35

In the depths of the Depression, this analysis of Moorcroft’s work as a sound financial investment had a clear pertinence. But it had a further significance. It ascribed to his pottery an enduring quality which was appreciated not only at the present time, but whose appeal seemed certain to last long into the future. It was a virtue identified in the finest oriental wares, and attributed, too, to some contemporary studio pottery:

Chinese pottery will answer to any interior, and for that reason may be claimed as a universal pottery, in a sense that Staffordshire or slipware can never be. For that reason, too, the modern stoneware potters who start from the Chinese have the best chance of making an art of to-day and, what is more, an art for to-morrow.36

Moorcroft’s ware, neither a slave to the past nor a plaything of fashion, was clearly seen in this same category. For The Industrial World of February 1929, even his most inexpensive functional pieces would inevitably acquire the status of art objects, such was their intrinsic and enduring quality; it was the trajectory from home to museum which had been evoked in analyses of pre-industrial wares since the end of the previous century:

Although Moorcroft pottery is sold at prices which make it possible for anyone to acquire some of the smaller pieces, there can be no doubt that it will be eagerly sought by collectors in the years to come, and that many pieces will find their way into the museum. Authentic pieces, bearing the signature of the artist, will inevitably become rarer, since so many will be broken in daily use […].37

In the course of these years, Moorcroft was forced to reduce his staff numbers and to sell wares he considered imperfect, but he would not compromise on his designs or production techniques, simply to lower his costs. In a review of a Leach exhibition at the Little Gallery, Marriott concluded that handmade functional objects could not be commercially viable, or compete with the moulded, mass-produced wares of industry:

What Mr Leach is trying to do, in short, is to push the resources of the small private kiln, staffed by two or three people, as far as they will go to meet factory production. It is not a case of attempted competition—hand-thrown can never compete economically with moulded wares—but an attempt to narrow the gulf between the two kinds in artistic quality.38

Moorcroft, though, held a different view; it was a position which set him apart from the manufacturers among whom he worked.

3. A Potter Apart

It was widely recognised that Moorcroft was a potter like no other in these desperate times, neither in the work he produced nor in the manner of its creation. The Industrial World drew attention to the working environment he had created, pointedly commenting on its difference from a factory:

Although the Moorcroft pottery is actually produced in what may be called a factory, it bears only a very slight resemblance to those which are devoted to the manufacture of the ordinary pottery of commerce. It is really much more a home of workers where each one does his or her part to contribute to the making of forms that are as beautiful as possible and in colours that are directly appealing. It was planned by Mr W. Moorcroft, the artist-potter, is pleasantly situated on a hill, with wide views over open country, and is surrounded by trees and shrubs. The aesthetic sense of the workers is developed by an artistic environment, and their physical well-being is assured by the hygienic conditions under which they work.39

For all that it was located in the Potteries, this was clearly not a place of industrial production, it was the site of collaborative artistic endeavour; Moorcroft was not seen as a manufacturer, but as an ‘artist-potter’. His ‘factory’ was described in terms which recalled an Arts and Crafts workshop where the quality of the wares produced and the working conditions of the craftspeople were of equal importance. The point had been made in the first reviews of Moorcroft’s works, but it had added significance now, nearly twenty years later, when the gulf between industry and studio was increasingly discussed. This unique atmosphere was noticed too by a visitor to Moorcroft’s works in a letter of 9 November 1930:

Although I had been going periodically to Stoke for some years, this was my first acquaintance with the inside of a pottery. I realise that your works are hardly typical: the personal touch which I found so much in evidence can scarcely be common elsewhere in these days of mass-production; it is a pity it should be so.

Moorcroft’s distinction, and distinctiveness, as a potter was underlined when he was invited in May 1930 to write an article on pottery for the national paper, The Daily News and Westminster Gazette, on the occasion of the bicentenary of the birth of Josiah Wedgwood. It was published on 19 May 1930, Moorcroft’s photograph appearing opposite that of Princess Mary, who had opened the celebrations that day.

Coming just months after the Wall Street crash, it was hoped that this anniversary would focus attention on the long tradition of pottery manufacture in Staffordshire and inspire a commercial revival; Moorcroft’s article, however, took a quite different line. A brief editorial introduction presented him as ‘one of the most individualistic potters of his time’, and the article itself, significantly entitled ‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’, was written from the perspective of a craft potter, taking a detached and implicitly critical view of contemporary industrial manufacture. Moorcroft’s opening remark focussed on the practice of pottery as a process of creation, as organic as nature itself:

In the making of a piece of pottery, it should first grow naturally, just as a plant from the earth, being a part of the earth, and any colour given to the pot should be an inherent part of it, as much so as the colour of a natural flower is an inherent part of it.40

Such metaphors underlined his commitment to thrown ware, a value he shared with studio potters. Staite Murray had written in 1925 of the ‘rhythmic plastic growth’ of the pot on the wheel,41 and in his review of a Leach exhibition at the Paterson Gallery, Marriott used a similar analogy: ‘You rear a pot as you might rear a plant.42 But these images had a particular resonance now, implying a discreet but unmistakeable distance from the popular, if impractical, angularity of many moulded forms, such as Cliff’s Conical range, introduced in 1929. No less critical of contemporary industrial practice were his comments on the use of bright, on-glaze colours; what he saw here was impermanence and superficiality, the very opposite of colour in nature:

Unless fashions in pottery are the outcome of a natural growth they will not give satisfaction. To apply a colour compound upon a fired and glazed pot is no less offensive than it would be to paint the bark of a tree.43

Moorcroft wrote as a potter, one whose mastery of glaze effects had been publicly admired as triumphs of the potter’s art. The firing of onglaze colours in a low-temperature enamel kiln required much less ceramic skill than was needed to achieve the different atmospheric conditions for the creation of high-fired colours in clay stained with metallic oxides.

But it was not just on the grounds of technique that he distinguished himself from industrial manufacture, there was a difference, too, of principle. For William Moorcroft, the potter’s art was not simply a commercial activity, it was a moral one, its aim to create beauty for others, not profit for oneself:

If our future pottery work were done with a spiritual and physical regard for the materials used in making the pot, we should give a real joy to the world. There would be no hard mechanical lines, no harsh ornament.44

Beneath this profession of faith, Moorcroft’s criticism of modern manufacture was as trenchant as that of Leach.45 He acknowledged the popularity of ware made to satisfy tastes of the day, but he saw in it an exercise in commercial opportunism. And even as he himself was feeling the economic pressures, it is striking that he should express so keenly his belief in the value, both artistic and monetary, of work produced according to more enduring principles:

It is difficult to combine commerce and art. Art, well considered and thoughtfully applied, is the greatest capital when dealing with the clays and metals of the earth—it is useless to say the public do not want real, thoughtful work. Too often the commercial man in his ignorance prevents the public from having what is their birthright—the opportunity to choose.46

In the quest for commercial survival, Moorcroft’s response was to maintain the basic principles of the potter’s art, respect for his materials, integrity of design; all else, he implied, followed from this, not least the appeal to the public. It was a powerful, personal statement, and a controversial one. Significantly, the article ended with his signature, which had become by this time the unmistakeable mark of the man, and the emblem of his authority.

Fig. 89 William Moorcroft, ‘‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’, The Daily News and Westminster Gazette (19 May 1930). ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Moorcroft’s distance from industrial manufacturers came to the fore in his display at the Exhibition of Modern Pottery, organised by the British Pottery Manufacturers’ Federation (BPMF) to accompany the bicentenary events. The Pottery Gazette described this project as ‘the most comprehensive Exhibition of modern pottery which has ever been staged’,47 and most of the major Staffordshire firms were represented. A review in the Pottery Gazette singled out in Moorcroft’s exhibit its range from ‘masterpieces of technical and artistic execution’ to simpler designs, but all distinctively his: ‘even in the less involved decorations there was that purity of line and grace of form which, in conjunction with perfectly balanced ornamentation, is a feature of Mr Moorcroft’s creations’.48 Moorcroft clearly promoted, and the review underlined, his royal patronage. What provoked dispute, however, was his inclusion in the exhibit of a card from Frederick Wilson, lecturer at the V&A, which repeated his much publicised endorsement of a vase with peach-bloom glaze first exhibited at the 1929 BIF: ‘The greatest achievement of the modern potter’. When Moorcroft wrote on 20 June 1930 to Sidney Dodd, secretary to the BPMF, a dispute had been rumbling for some time:

In reply to your letter of the 19th of June, I have a witness of the statement you made in the King’s Hall with regard to the card I was showing in my case. You expressed the view that the written statement of the Expert of the Victoria and Albert Museum was ‘mere puff’. When you made the statement, you also told me that your committee had met and demanded a withdrawal of the card from my case.

The BPMF had doubtless taken the view that Moorcroft’s display of Wilson’s comment implied the technical and artistic superiority of his own work, at the expense of the other exhibitors; for Moorcroft, their objection implied a disparagement of his achievement as a potter. Edith Harcourt Smith, writing in the aftermath of the exhibition, had no doubt about the cause of the dispute, and the conclusions to draw from it, bluntly suggesting in a letter of 8 June 1930 the radically different priorities which distinguished Moorcroft from Staffordshire potters in general, and which his article had eloquently made plain:

[…] it was just you, thoughtful to a degree, full of beautiful ideas and hopes, my husband thought the same. It was very kind of you condescending to write it, for all those men down there are full of jealousy, and you returned good for evil. Yet remember, you’re on a different plane altogether, and they know it!

The quarrel, in itself trivial, nevertheless indicated a significant tension between Moorcroft and the BPMF. It was no doubt exacerbated by the fact that Moorcroft had not paid his levy to the Federation since first joining in 1926; Dodd had much correspondence with him on this subject too. But its causes lay almost certainly deeper, arising from Moorcroft’s distinctive approach to pottery manufacture at the heart of the Potteries, all the more unpalatable as he was clearly admired both in the trade press and in London, and appeared to be weathering the economic storm. Ironically, at the height of the dispute, on 2 July 1930, Claude Taylor wrote to inform him that he looked likely to be awarded the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition at Antwerp: ‘It is excellent to find that they have recognised your work and propose to give you the highest award possible’. If his work provoked dispute in the Potteries, it was winning acclaim in Belgium.

Shortly before Moorcroft’s article, Marriott alluded again to the possibility of bridging the gap between studio and industrial production in a review of a Leach exhibition at the New Handworkers’ Gallery:

The difficulty of linking up studio and factory pottery so as to retain the high quality of the one and secure the practical advantages—of rapid production and low cost—of the other is now an old story. Many attempts have been made to bridge the gulf […].49

The review ended with a reference to a ‘special exhibit’, a ‘standardised tile fireplace, composed of tiles made in quantity by semi-mechanical means and decorated with conventional animal, bird and plant forms’. The example was significant, introducing the two elements which Marriott (and many others) saw as the basis of a successful collaboration between craft and industry: standardised design and mechanised production. It was the model he would subsequently applaud at Stockholm later that same year; it was the way of the future. Moorcroft, though, had a quite different conception of his identity as a potter, and his article, written just weeks after Marriott’s review, and on the occasion of a major industrial bicentenary, was the defiant affirmation of his practice of (true) manufacture, making by hand. He was bridging the gap between studio and factory, creating craft wares on a larger than studio scale, and defying the commercial pressures in the process. In an article published in the Sunday Dispatch, he was seen to place himself at the very centre of production:

No machinery is used in the execution of my work, Mr Moorcroft said today. I use only the potter’s wheel, an instrument that has been in existence for 4,000 years or more. Many people have asked me why I mix my own chemicals, why I design and mould all my own work; but my only answer is that I am the creator. To leave this to other people would be to destroy my greatest joy.50

He was, in the words of the article, a ‘one-man factory’.

What distinguished Moorcroft above all from manufacturers, either from Staffordshire or Sweden, was not simply his close personal involvement in both design and production, but his principled opposition to mass production. Large-scale replication implicitly sited the quality of an object in its design; this was increasingly seen as the new art, art for the modern age of mechanical reproduction. Marriott identified this ambition in his review of the Stockholm Exhibition: ‘its primary object may be supposed to be to present the artistic possibilities latent in standardisation and mass production methods. Its motto might be ‘How to civilize the machine’.’51 For Moorcroft, however, manufacture was about individuality, not uniformity. Even his dinner ware, significantly, was not intended for production in industrial quantities. Writing to his daughter, Beatrice, on 20 November 1930, he recounted his meeting with ‘a keen commercial mind in the form of a buyer from the United States of America’:

He suddenly expressed a keen admiration for my new service plates. So he imagines I shall require an enlarged works. It is not really the case, as I do not want mass production. I feel there is a need for interesting, individual things. Something with individual thought expressed therein.

His objection was closely connected to how he viewed himself as a potter. He did not seek to create standardised wares, easily reproduced by means of moulded forms, printed decoration, or freehand copying; he was defending the individuality of craft. But he was defending too a very personal conception of design, which was not simply a response to the requirements of market forces, function, or mass production, but which was, above all, a means of expression.

4. Nature and Self-Expression

Moorcroft’s public interventions frequently voiced a critical attitude to the commercial motivation of modern industrial design. For him, design was much more personal, a response to the world around him. He often gave expression to this belief in the letters he wrote, at least once a week, to his teenage daughter, Beatrice, at school in Buxton. A recurrent theme in these letters is the inspiration he found in the contemplation of nature. Writing on 12 October 1930, he described a sunset he had witnessed on his way home from a visit to Buxton:

The sunset was very charming, the massive rocks made a majestic foreground. In parts there were beautiful turquoise blue clouds behind the dark purple hill, and in other places there were the rich glowing clouds that suggested the fire of the sun. […] These beautiful scenes carry our thoughts both before and beyond our time. How delightful it is to live and to think of worlds beyond, of all that is infinite […].

Moorcroft’s sensitivity to colour is evident here, but so too is his active engagement with the experience. This was a spectacle not simply to be enjoyed, but to be read; in it he saw and celebrated the wonder of creation. Just as he had sought in some earlier designs to capture natural scenes in the light of the evening sun, or the risen moon, he was inspired by such moments as this to create a series of striking landscapes, their impact enriched by their glaze effects; these were pieces made in very small numbers, but they were not just technical experiments, they expressed a gratitude for life, a sensitivity to the magnificence of the natural world.

He was no less sensitive to leaves than to landscapes. Recurring frequently in his designs over the next decade, they embodied Moorcroft’s delight in the simple as well as the majestic, and inspired a motif developed in pieces large and small. In a letter of 23 November 1930, he was already reflecting on the rich and varied colours of the leaf in autumn:

Recently I have been making pottery and obtaining colour in it resembling autumn leaves. […] There are leaves of a golden yellow with veins of a red sunset colour merging into a luscious green, somewhat like the green leaves we see in the woods in the autumn intermingled with the morning dew lying on the ground. There is a charm in such colour, like the charm one finds in the singing of the birds and in the running river. A charm one finds in all that is Pure […].

As he sought to express in words the correspondence of sight and sound in this rich synaesthetic experience, he endeavoured too as a potter to embody in colour, form and texture the beauties of the world he observed. It was a significant statement. In his catalogue essay for Staite Murray’s exhibition earlier that month, Herbert Read had evoked pottery as self-sufficient form, ‘pure art’, with no representation either explicit or implicit.52 Moorcroft’s conception of ‘pure’ ceramic art was more expansive, it was pottery in the service of nature.

Moorcroft’s responsiveness to the natural world was evident too in another of his new decorative motifs, fish, admired by the Queen at the 1931 BIF. The motif coincided with the installation of a fishpond in his garden at Trentham. What enthused him most about the fish were their sinuous movements and iridescent colours in the sunlit water. Even as his dispute with the BPMF was gathering momentum, Moorcroft delighted in these impressions in a letter of 8 June 1930:

This afternoon we sat reading in the garden with the fountain playing. The fish were leaping up to kiss the sun, as it were, and the colour was charming. I had no idea how wonderful goldfish are in colour when they leap out of the water. They resemble a combination of rubies, gold and silver, each element appearing to be more supreme than another.

Such comments shed light on Moorcroft’s creative process. He did not seek designs in books of decorative ornament, or in contemporary trends, he consulted the world around him. And he clearly found it both stimulating and refreshing to do so, respite from the preoccupations of everyday life which (he felt) stifled his creativity. He wrote wearily to Beatrice on 29 November 1931; nature alone could enliven the spirit:

There is too little time to see the beautiful country, and without nature’s teaching we become torpid, dull, inanimate. So often one feels with the poet who wrote: Oh for the wings, the wings of a dove, far, far away would I roam. And yet one’s imagination helps one to survive.

The reference to Mendelssohn’s anthem, made famous in Ernest Lough’s iconic recording of 1927, did not just indicate sympathy with the yearning of the text, but implied, too, a recognition of the reviving power of beauty in a troubled world; he expressed its value in a letter of 12 November 1929: ‘Nature ever abounds with interest. And one’s imagination is quickened thereby. And nature sometimes outdoes even the pressures of work.’ It was this energising, restorative influence which inspired him as an artist, and which he sought to capture in his pots. The transforming effect of his imagination is evident in variants of toadstool or landscape designs created at this time, pieces which evoke moments in the natural cycle from vitality to repose, their expressive power enhanced by the intensity of colour beneath the rich flambé glaze. Even in the depths of 1931 he was moved by nature’s beauty; it did not simply provide a means of escape from the increasing commercial pressures, it represented all that was real, all that truly mattered:

This is a day of glorious sunshine, the trees and flowers are together joyous with their new life. The green of the leaves was never more beautiful and the flowers seem to have risen in a night to throw out their spirit of thankfulness for such an awakening.53

At this time of exceptional economic, political and social uncertainty, Moorcroft’s preoccupation with the beauty of the natural world had a particular resonance. On 9 June 1929 he contrasted what he saw as the haste and commercialism of modern life with the tranquillity and expansiveness of nature:

Motor cars, petrol pumps and hideous advertising are like an ugly dream as we walk in the country. With such restlessness it will be difficult to create great literature or great architecture or any great art. To do great work, we somehow yearn for spaciousness, for the great breadth of the hills and plains, for the gentle, continuous flowing river.

For William Moorcroft, nature embodied a completely different, more peaceful and more authentic rhythm of life. It was this that he yearned for as the post-war world entered its second decade; writing on 15 October 1930, he expressed the belief that a new era of calm would soon succeed the turbulence of the present:

In these days, it is more than ever necessary to make things as appealing as possible. Sometimes I think we are about to change from a period that has been conspicuous for its unrest […], to another period of extreme restfulness. Then we shall find restraint in thought and speech, in our great arts, in music, in painting, in sculpture, and in all the minor arts. Once again we shall avoid mass production and we shall all strive and we shall all seek for beauty and truth in all things.

It was a defiant response to the modern age. On that very day, The Times had reported Marriott’s lecture to the Anglo-Swedish Society, in which he saw in the Stockholm Exhibition the dawn of industrial design:

It was […] a frank and calm acceptance of things as they are, and an attempt to make the best of them artistically on their own lines; and as reflecting the Swedish combination of idealism and common sense, it cleared the way for the future.54

No ‘calm acceptance’, though, from Moorcroft; he had a different vision to express.

Fig. 90 William Moorcroft, ‘Autumn Leaves and Berries’ (c.1930), 6cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 91 William Moorcroft, early fish designs under flambé glaze (1931): (left) 15cm; (right) 17.5cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 92 William Moorcroft, experiments with flambé glaze: (left to right) Landscape (c.1931), 23cm; Toadstools (c.1930), 20cm; Landscape (c.1930), 20cm. CC BY-NC

His prediction was unfounded, but his very personal designs continued to speak to the times. Critics often noted in his work a quality of restfulness, recognised as unique in contemporary design. A review of his 1930 BIF exhibit sought to explore its distinctive character:

W. Moorcroft, Ltd., Burslem, once more presented an exhibit which, to lovers of the beautiful in pottery form and decoration, provided a real resting place for the eye. […] Somehow, each individual pot seems to have some quality which is personal, and belongs to no other pot in quite the same degree. In short, there is a soulfulness about every individual piece of ‘Moorcroft’ ware which can be associated only with pottery which reflects in no uncertain degree individualism in its production.55

Particularly striking was the critic’s emphasis on the effect of Moorcroft’s ware. This was pottery which was serene, expressive, personal, qualities quite different from those found in industrial manufacture; the critic’s reference to its ‘soulfulness’ echoed, consciously or not, Leach’s ‘A Potter’s Outlook’: ‘who has ever seen a factory-made pot with a nature of its own—a soul? How should it have one, except it were breathed into it by the love of its maker?’56 This was precisely the quality Moorcroft sought in his work, and in whose expressiveness he had such confidence. Significantly, even his Powder Blue was experienced in a similar way. Introduced in 1914, its purity of line, harmony of form and colour, and unobtrusive functionality were qualities which anticipated in many ways the modernist aesthetic coming increasingly to the fore. And yet, for all its absence of ornament, it exuded that same stillness so frequently identified in Moorcroft’s ware at this time, as Edith Harcourt-Smith noted in a letter of 17 September 1929:

You are so often talked of in this house by us and those who come. Your tea service is in use daily, giving untold delight all round. One never tires of the hue of blue, restful as well as cheerful, which is what one requires.

In a letter to Beatrice of 24 February 1929, Moorcroft recalled the visit of the Prime Minister’s wife to his stand at the British Industries Fair: ‘On Wednesday, Mrs Baldwin called to see our pots. She was charmed, so she said, and chose a special piece for the Prime Minister.’ On the day before this visit, 19 February 1929, Baldwin had faced (but narrowly avoided) defeat in a Commons vote on proposals for compensation to be paid to Irish loyalists. Mrs Baldwin’s purchase of a ‘special piece’ for her husband that day may well have been another, unobtrusive endorsement of the calming qualities of Moorcroft’s art.

Pottery brought Moorcroft close to the earth, both literally and figuratively. On 24 October 1930, he imagined working with his daughter, enjoying the wonder of creativity:

I am longing for the day when you will be with me at the works, making beautiful things, good forms, good colour and thrilling design. The joy of expressing oneself in a material that has been already millions of years in the forming is inexpressible. To enter upon it with a reverent regard for its possibilities is some way towards success.

This was not just (or even at all) an anticipation of the future, it was a profession of faith. His focus was not on creating designs which might be profitable, but on those which embodied a personal sense of beauty, a tribute to the earth; this was the ‘success’ he evoked. In these desperate economic conditions, when commerce and art were increasingly difficult to reconcile, Moorcroft was formulating afresh his reasons for creating, expressing the enduring significance of his ware, even when his balance sheets might have implied that it had no value, and nothing to say.

5. Conclusions

As economic conditions continued to deteriorate, Moorcroft began his new career as holder of the Royal Warrant with a defiant commitment to individuality both of design and of production. It was a commitment upheld in the face of conventional commercial logic, or necessity. The focus of his efforts was not simply, and perhaps not even predominantly, the balance sheet, it was on the expression of beauty as a response to the times, and on the benefits which this might bring. Writing to Beatrice on 27 February 1931, in the year which saw his most significant trading loss to date, he noted with evident pleasure the continued appreciation of his ware. Pottery was not simply a commercial exercise, it was an act of service:

The concentrated work of some months has found its reward. […] Many times, visitors have been thrilled and found words only too inadequate to express their admiration and their love for Moorcroft pottery. It is gratifying to find that one is able to give joy to someone.

In happier times, this attitude had brought significant trading success; now, there was a growing tension between (his) art and commerce.

It is clear, though, that his work continued to speak to the times, in a language beyond words. From his earliest years at Macintyre’s, Moorcroft had voiced the ambition ‘to express with as much humanity as possible my thoughts in clay’; for him, this was not a matter of finding a distinctive style, but of giving form to a philosophy of life, a vision of the world. And to do so required both the ceramic skill of a potter and the sensitivity of an artist, each applied to the best of his ability; he wrote to Beatrice on 30 October 1929:

Natural science and physics are both subjects full of interest, and […] only as we realise the mystery and beauty of nature’s way do we make good things. […] There is a definite charm in putting one’s thoughts into a material that is practically indestructible. And when one has such a responsibility, that of using a material that is so lasting, it is necessary to express ourselves with immense care.

What he envisaged was an art which had an enduring value, all the more significant in these turbulent and uncertain times. It is perhaps no coincidence that he expressed this view on the very day The Times reported an event which took the world into uncharted economic territory: ‘Wall Street record. Nearly 17,000,000 shares sold […] There has never been such a day of liquidation on the stock markets as this.’57

Paradoxically, Moorcroft’s self-expression was akin to self-effacement; his aspiration to the highest quality was his tribute to the beauty of the natural world: the warm harmonies of sunset, the luxuriance of autumn, the joyful freedom of fish in their element. In a letter of 4 March 1930, he described his sense of responsibility to complement nature, not to compete with it:

Just now I have been thinking how to make pots to hold iris and tulips, and blue and red anemones. […] As God gives us such beautiful flowers, it is a sacred trust, that of attempting to display them. To put charming fairy-like flowers into crude vessels of either glass or pottery seems almost a crime. Only the best of one’s imagination should be used in finding a counterpart for the flowers to rest in.

And his work was a tribute, too, to the materials with which he worked, as he wrote to his daughter on 7 December 1930: ‘why should not we do our utmost to make beautiful things, something worthy of the materials God provides us with?’ The personality of the designer was expressed in the pieces he fashioned; but the focus remained on the objects themselves. The article in the Sunday Dispatch provided a rare glimpse of the man behind the pots, his achievements all the more compelling for being so understated:

Meet Mr William Moorcroft. He is an unassuming little man with a softly modulated voice. When he speaks of himself, it is in a tone of depreciation, but in the Potteries district he is regarded as the master potter of the world.58

But if there was humility in Moorcroft’s art, there was also self-belief. At a time of extreme economic pressure, he continued to experiment. On 17 October 1930, as he worked on the designs he would launch to such critical acclaim at the 1931 BIF, he gave expression to a defiant spirit, drawing strength from his past as he confronted the present, and the future:

[…] these days one has more to do than usual owing to difficult economic conditions. It is useless to take things as though all was normal. I feel that difficult times are with us, to force the best out of us. We do better work when we are faced with something to fight against.

He was widely seen to be creating a ware which was distinctively his and which could not truly be imitated. In a world where standardisation was the watchword of modern industrial manufacture, Moorcroft continued to affirm the very personal quality which had defined his art since the start of his career. It was in this spirit that in the spring of 1930 he explicitly, and pointedly, submitted his exhibit to the International Exhibition in Antwerp in his own name, and not that of the firm which bore his name.

Fig. 93 Part of Moorcroft’s ‘personal’ exhibit at Antwerp 1930. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Fig. 94 Photograph of Moorcroft’s works, and the amended version sent to Town and Country News in 1930. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

To exhibit as a firm might imply that his work was no more than a commercial commodity, lacking ‘soul’ both in its inspiration and its making; he wished to stress, on the contrary, that his exhibit was ‘a personal one’, as a letter from R.E. Moore dated 1 October 1930 made plain:

I have already pointed out to the Belgian authorities that your exhibit is a personal one, and have ascertained that on their records the entry is simply ‘W. Moorcroft, Esq.’ I hope therefore that the diploma will be correctly inscribed […].

There could be no more emphatic way of asserting his commitment to craft over design, of individuality over uniformity. More telling yet were the photographs of his works supplied to Town and Country News for Marfield’s article of 15 August 1930. If the sign board actually carried the name of his firm, W. Moorcroft Ltd., the photographs submitted had been consciously altered, the letters ‘Ltd.’ blacked out to leave visible simply his name. A small but eloquent transformation of manufacturer to potter.

By the end of 1931, Moorcroft had introduced a stamp to mark his Royal Warrant.

Fig. 95 Labels and stamp used to indicate Moorcroft’s Royal Warrant. CC BY-NC

A gold foil label, embossed with the Royal Arms and the formula ‘By Appointment to H.M. the Queen’, had been applied to pieces in the months immediately following his award, but it almost always became detached from the wares. It was soon superseded by a paper label, which added to the wording ‘By Appointment…’ the title first granted in 1765 to Josiah Wedgwood by Queen Charlotte to record her admiration for his ware: Potter to H.M. the Queen. It was a personal tribute, significantly singular. The design was completed with Moorcroft’s signature, the unmistakeable emblem of his individual investment in each piece. The stamp, though, was more eloquent still. Unlike a label, it fixed the very personal nature of his Warrant in the body of his ware, the one henceforth indissociable from the other. But it also, tellingly, took the place of the upper case stamp ‘Moorcroft’, for more than a decade the trademark of his firm: the potter’s affirmation of his individuality was imperishable, unequivocal and uncompromising.

1 Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (August 1929), p.1290.

2 PG (September 1930), p.1469.

3 PG (June 1931), p.866.

4 PG (April 1929), p.610.

5 Unsourced press cutting in William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

6 Pottery and Glass Record [PGR] (March 1931), p.69.

7 C. Marriott, ‘A Japanese Potter’, The Times (24 May 1929), p.12.

8 PG (April 1930), p.612.

9 All unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in WM Archive.

10 Ibid.

11 C. Marriott, ‘Stoneware Pottery’, The Times (3 November 1928), p.17.

12 ‘The Queen’s Potter’, Sunday Dispatch (24 March 1929).

13 Ibid.

14 ‘The Charm of Pottery in the Home’, Woman’s Pictorial (12 January 1929), p.13.

15 M. Brandon, ‘A Home of Artist-Potters’, The Industrial World (February 1929), 26–27 (p.27).

16 Staffordshire Sentinel (17 February 1931), p.4.

17 His designs did not fit into the categories identified by Pevsner, An Enquiry into Industrial Art in England (Cambridge: C.U.P., 1937): ‘However, good or bad, Banded or Floral, English earthenware is by now modern (or modernistic) in appearance. It was about eight or ten years ago that commercial Modern Floral forced its way into the British market. Banded patterns came a little later, about 1930’ (p.75).

18 E. G. Marfield, ‘The Revival of Ceramic Art. A British Master Craftsman and His Creations’, Town and Country News (15 August 1930), 24–25 (p.25).

19 PGR (April 1929). Moorcroft would adopt that phrase in some of his publicity material.

20 Brandon, ‘A Home of Artist-Potters’, p.27.

21 P. Scott, ‘The Woman Buyer comes to London for Ideas’, The Morning Post (23 February 1931).

22 ‘A Christmas Hint’, Public Opinion (11 December 1931).

23 Ibid.

24 PG (April 1930), p.637.

25 Letter from Pasco, 17 July 1930.

26 ‘The Master Potter’, Sunday Dispatch (24 March 1929).

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 ‘”For slender purses”. Industrial Art Exhibition’, The Times (9 November 1929), p.9.

30 PG (June 1930), p.941.

31 ‘Art and Household Decoration’, The Times (8 October 1930), p.12.

32 ‘Art and the Machine. The Achievement of Stockholm’, The Times (18 June 1930), p.15.

33 ‘Swedish Art’, The Times (18 March 1931), p.17.

34 ‘Art Exhibitions’, The Times (29 October 1931), p.10.

35 ‘British Pottery Industry’, The Overseas Daily Mail (27 December 1930).

36 W.A. Thorpe, ‘English Stoneware Pottery by Miss K. Pleydell-Bouverie and Miss D.K.N. Braden’, Artwork (Winter 1930), 257–65 (p.257).

37 Brandon, ‘A Home of Artist-Potters’, p.27.

38 C. Marriott, ‘Art Exhibitions’, The Times (29 October 1931), p.10.

39 Brandon, ‘A Home of Artist-Potters’, p.26.

40 W. Moorcroft, ‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’, The Daily News and Westminster Gazette (19 May 1930).

41 W.S. Murray, ‘Pottery from the Artist’s Point of View’, Artwork (May-August 1925), 201–05 (p.201).

42 C. Marriott, ‘Stoneware Pottery’, The Times (21 April 1926), p.20.

43 Moorcroft, ‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’.

44 Ibid.

45 Leach, ‘A Potter’s Outlook’, p.189: ‘the shapes are wretched, the colours sharp and harsh, the decoration banal, and quality absent’.

46 Moorcroft, ‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’.

47 PG (December 1929), p.1960.

48 PG (July 1930), p.1133.

49 C. Marriott, ‘Stoneware Pottery’, The Times (31 March 1930), p.12.

50 ‘The Master Potter. Art Objects for the Queen. One-Man Factory’, Sunday Dispatch (24 March 1929).

51 ‘Art and the Machine’, The Times (18 June 1930), p.15.

52 H. Read, ‘The Appreciation of Pottery’, reprinted as ‘Art without Content: Pottery’ in The Meaning of Art (London: Faber & Faber, 1931), 32–33 (p.33).

53 Letter to Beatrice, 10 May 1931.

54 ‘Mr C. Marriott on Stockholm Exhibition’, The Times (15 October 1930), p.10.

55 PG (April 1930), p.612.

56 Leach, ‘A Potter’s Outlook’, p.189.

57 The Times (30 October 1929), p.14. On 28 and 29 October 1929, the Dow Jones index fell in value by more than 23%; the Wall Street crash is seen to mark the start of the Great Depression, the longest and most widespread period of recession in the twentieth century.

58 ‘The Master Potter’, Sunday Dispatch (24 March 1929).