2. 1901–04: The End of the Beginning

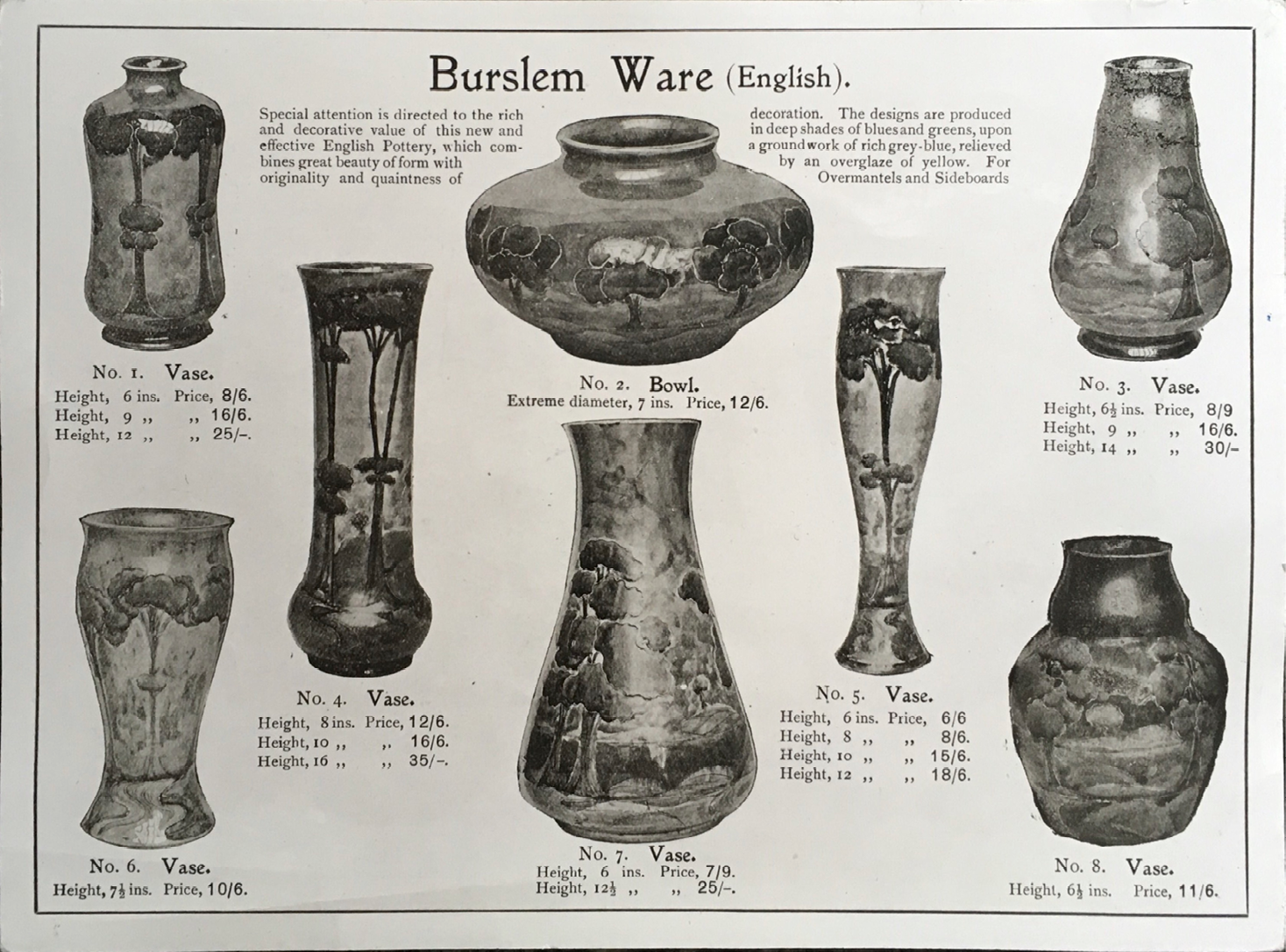

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.02

1. New Directions in Design

As the new century dawned, the need for fresh initiatives in pottery design was widely recognised. Techniques and materials were becoming increasingly globalised, and competition from abroad, particularly from Germany and the US, was increasing. In 1903, William Burton regretted that the Staffordshire potter, ‘content to work on his old traditional lines’ had fallen far behind the innovative work of potters in Europe.1 And in 1904, the Pottery Gazette ran a series of articles on ‘The Present Position of Pottery among the Crafts’, which lamented, as so often, the continued reliance on transfer printed decoration; the conclusion was uncompromising: ‘the bulk of the decorated pottery made in England today is entirely spurious and commercial’.2

If the refined pâte-sur-pâte decoration perfected by Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon at Minton was accorded ‘the post of honour among the artistic porcelains of the nineteenth century’,3 it is clear that for many potters, both industrial and individual, the future of ceramic art lay elsewhere. Several potteries were following the lead of French potters, conducting advanced research on glazes, with a view to mastering ancient techniques and making them commercially viable. John Slater, Charles Noke and Cuthbert Bailey worked together at Doulton Burslem to re-create Oriental flambé effects suitable for industrial production; they commissioned the help of Bernard Moore, one of the country’s leading ceramic chemists, who had developed reduction firing to produce his own ‘novel and wonderful effects by the use of metals other than copper’.4 The fruits of nearly three years of experiment were displayed at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St Louis in 1904, where they won two Grands Prix. William Howson Taylor’s high-fired glazes won a Grand Prix at the Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin in 1902, and were welcomed in the Pottery Gazette of January 1903 as a ‘new kind of artistic pottery’.5 Owen Carter was producing reduction-fired lustre wares at Carter & Co. from 1901; from 1902, Sir Edmund Elton was making crackled lustre ware; and Burton’s own research at Pilkington into crystalline, opalescent, eggshell and transmutation glazes culminated in a special exhibition at the Graves Gallery in June 1904. In a review, Lewis Day acknowledged that ‘the most recent advances in ceramic art have been […] in the direction of artistic effects due entirely to the science of the potter’.6 Pilkington also introduced a range of pottery under the name ‘Lancastrian’, using decorative schemes by leading artists or designers such as Walter Crane, Lewis Day and C.F.A. Voysey. And other firms sought a modern look by adopting the European fashion for art nouveau. In 1902, Minton launched Secessionist ware, designed by Léon Solon and John Wadsworth, and at Doulton Lambeth, Eliza Simmance introduced designs in a similar style.

From the start of the new century, Moorcroft was experimenting, too. He clearly did not have the facilities of Doulton or Pilkington to conduct his own elaborate glaze experiments, but nor did he simply follow the fashionable path of art nouveau. Continuing to explore the relationship of form, ornament and colour, he produced in these years some of his most creative and original work. Leaving behind the more formal designs of early Florian, Moorcroft moved towards a sparer style of floral decoration, setting off the lines of stem and flowerhead against a plain white ground. Such designs were closer in spirit to the contemporary art glass of Daum, having the fluidity of art nouveau, but simplified; space became just as important as ornament. Notebooks dating from this period reflect new thoughts and guiding principles:

Consider the need of greater simplicity.

To be simple in decoration is always to be in good taste.7

Of a quite different style was a floral design which he would refer to in a notebook from 1902 as ‘Florian cloisonné’; it was registered in January 1903. Far removed from the shaded colouring of Florian, it created stylised designs from solid blocks of colour, starkly juxtaposed. It was produced in different palettes, most notably Green and Gold, Blue and Gold, and a Blue, Salmon and Red with Gold, subsequently called Alhambra. Quite different again (and requiring particular skill from the decorators) were designs which set the distinctive outline of Honesty seedheads (or, occasionally, other flowers) against a stippled ground, focussing attention not on colour, but on line and texture.

Fig. 14 William Moorcroft, Examples of more open, flowing designs in blue on white. Harebell (c.1904), 20cm; Poppy (c.1902), 24cm; Cornflower (c.1902), 17.5cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 15 William Moorcroft, ‘Florian cloisonné’ in three distinct palettes: Narcissus in Green and Gold (1904), 24cm; Tulip in Blue, Salmon and Gold, ‘Alhambra’ (1903), 7.5cm; Narcissus and Tulip in Blue and Gold (1903), 15cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 16 William Moorcroft, Designs on stippled ground. Honesty (c.1903), 22.5cm; Tulip (c.1903), 20cm. CC BY-NC

But Moorcroft’s design experiments were by no means confined to the world of flowers. By the spring of 1902, he had produced the first of his landscape designs, a motif which he would revisit and modify throughout his career. It was explored in different palettes, with contrasting effects of blue on blue (with occasional touches of yellow or pink), of green on green, or of green on white. And it clearly attracted the attention of Liberty’s. An order, dated 15 April 1902 included ‘the new ware with trees [in] a variety of forms’; the design was not officially registered until September 1902.

Fig. 17 William Moorcroft, Sketches for Landscape designs in notebooks. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. Two early examples of the design: Hyacinth vase with blue landscape (1902), 18cm; vase with green landscape (c.1903), 10cm. CC BY-NC

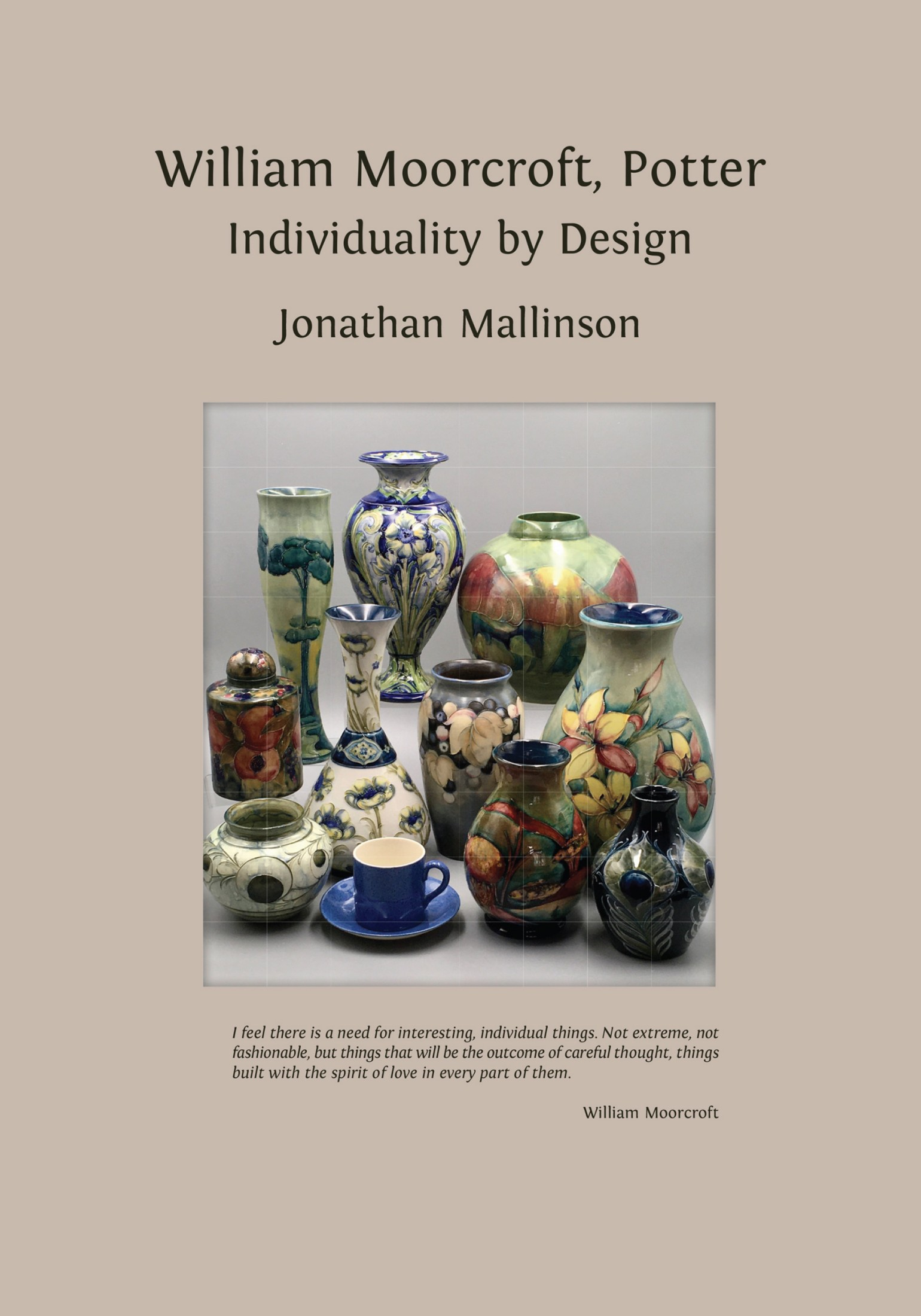

At the start of 1903, he was experimenting with toadstool motifs. Notebooks from this time contain many sketches of fungi of different sizes and aspects, as well as comments about treatment. It was in this design that he expanded his palette of colours, introducing different shades of red and orange. A notebook records what would eventually become one of his most distinctive effects: ‘The necessity of a more harmonious combination, a softer bleeding of colour’. This ‘bleeding’ of colour would create a strikingly ethereal air, at the opposite pole to the clean lines and stark contrasts of Wadsworth’s Secessionist wares. By the end of the year, the design was in production; on 21 November 1903, his diary recorded the despatch of ‘first package Toadstool decoration’ to Liberty’s.

Fig. 18 William Moorcroft, Sketches for toadstool designs in notebooks. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. Bowl in early version of the design (1903), 10cm. CC BY-NC

It was in early 1903, too, that he created the first of his fish designs. Produced in very small numbers, and with an implied allusion to Gallé’s celebrated carp vase, exhibited at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878 and bought the following year by the Musée des arts décoratifs, it was clearly intended as a collector’s piece. He would include it in his exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904.

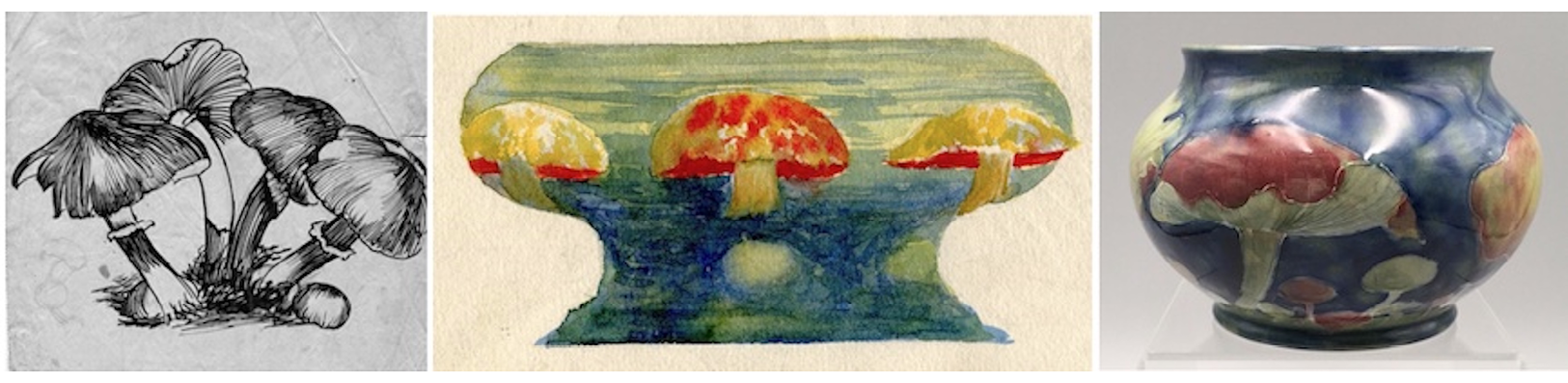

It is significant that several of these experiments were attracting the attention of Liberty’s, whose reputation was founded on their involvement in innovative design. The store would become particularly associated with two of the most original of these designs, Tree and Toadstool, which they retailed under their own distinctive names, Hazledene and Claremont. Their Yule-Tide Gifts catalogue of 1902 included a full-page picture of Hazledene pots, under the heading ‘Burslem Ware’. The accompanying text promoted the artistic qualities of this ware, which combined ‘great beauty of form with originality and quaintness of decoration’. And Claremont featured in their Bric-a-Brac catalogue of c.1905: ‘The motif […] and the name were suggested by a peculiar kind of fungi growing in the woods on the estate of the Duchess of Albany.’ The statement tellingly underlined the fact that the design was inspired by nature; this was ceramic art for the modern age, breaking free from the stiff historicism of the previous century. And it suggests, too, an early sign of Moorcroft’s creative collaboration with Alwyn Lasenby, who lived in Esher, the location of the Duke and Duchess of Albany’s Claremont estate.

But Liberty’s interest did not end here. During 1904, they commissioned Moorcroft to produce an exclusive floral design; a diary note on 11 March 1904 records work on ‘Tudor Rose’, a pattern registered in April 1904. It was to be a more traditional motif, but in a quite new palette set on a distinctive jade ground; and Moorcroft would use it to experiment with variants on the running glaze effects which were beginning also to characterise ‘Toadstool’. And in 1904, too, he was creating pieces for Liberty’s new range of Tudric ware, launched in 1902 and made for them by Haselers of Birmingham. Noted for its avant-garde designs, many by Archibald Knox, Tudric brought modern style and quality of finish within the reach of a much wider market than the Arts and Crafts Guilds were able to do. Moorcroft was recognised as a designer working very much in the same spirit, his diary for 2 February 1904 noting a meeting with Lasenby to discuss ‘the application of pottery to mounting in pewter’. Liberty’s interest in Moorcroft’s modern designs was wide-ranging, and their collaboration was bringing both aesthetic and commercial rewards; an order dated 1 June 1904 was characteristic of many:

£100 Tudor Rose design in Vases, Pots and Bowls

£50 in Toadstool design (Claremont), shapes as suggested

£25 in Tree design (Hazledene), shapes as suggested

Fig. 19 ‘Burslem Ware’, in Liberty & Co., ‘Yule Tide Gifts’ catalogue (1902). ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

|

|

(L) Fig. 20 William Moorcroft, Early examples of ‘Hazledene’ (1902), 25cm; and ‘Claremont’ (c.1903), 10cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 21 William Moorcroft, ‘Tudor Rose’ (1904), 12.5cm. CC BY-NC

In his review of the Turin exhibition of 1902, Crane expressed concern that art nouveau had become no more than a decorative style, an ‘aesthetic rhetoric, with little or no thought or meaning behind it’, imitated and thereby degraded ‘for purely trade purposes’.8 Against this background, Moorcroft’s new designs stood out, and they were noticed, not least by imitators. Lasenby wrote to him on 13 February 1903; a London firm was selling copies of his ware, albeit without his signature, and he advised Moorcroft to adopt a robust response:

[…] you appear to me to be practically helpless, unless you are prepared to tell them that in view of the totally unjustifiable position which they have assumed, having committed a wrong on you, that you prefer to thrash out the case in court, as a warning not only to them but to others who may desire to pirate your goods.

If not the most welcome form of flattery, such plagiarism nevertheless confirmed Moorcroft’s status as a designer already, and firmly, in the public eye.

2. Making A Name

Moorcroft’s energy and creativity continued to attract the attention of the art world. His diary of 5 March 1901 noted a meeting with Charles Holme, founding editor of The Studio, and he was approached in January 1902 by William Jervis, Stoke-born potter and author now resident in the US, who wished to include Moorcroft in a commissioned Encyclopedia of Ceramics. A surviving draft of Moorcroft’s reply, dated 28 January 1902, gives a unique insight into how he saw his vocation as a potter at this time, underlining, as so often, its primary purpose as a means of expression:

[…] I will do my best to give a short account of what has mainly led to my great desire of expressing with as much humanity as possible my thoughts in clay. The potter and his art have charmed me from my earliest days […], and my desire increases to make an effort to carry forward the fine spirit which was manifest in the early workers of centuries ago […].

Jervis’s article appeared first in Keramic Studio, a journal founded in 1899 by the pioneering potter Adelaide Alsop-Robineau. He gave a detailed account of Moorcroft’s distinctive production technique, portraying a designer who retained the individuality of handcraft within the constraints of commercial production:

[…] it is all made by the old process on the potter’s wheel and the turner’s lathe, […] on purpose that as far as is practicable in a commercial project, the individuality of the designer should be preserved, nor is there any use made of other mechanical aids, such as printing the outline, each piece being entirely done by hand.9

This individuality was identified, too, in Moorcroft’s skills as a ceramic chemist. The range of colours available for underglaze decoration may once have seemed limited, but at the end of the article praise of Moorcroft’s palette took Jervis to the limits of language:

Our illustrations will give a good general idea of the forms and decoration, but the unsurpassably beautiful colors with their iridescence and charm, their hidden depths revealed by the fire of the furnace, can only be imagined.10

Jervis, writing as a potter, understood the significance of Moorcroft’s methods of production, and he recognised, too, that this work was innovative, and personal. It was not just a question of technique, but also of design; William Moorcroft was creating work ‘of such a high order of merit as to justify us in classing his work as a distinct advance in ceramics, charming alike in thought and execution’. Florian was, he concluded, ‘the inspiration of an artist’.11 Even in 1902, Moorcroft’s project as a potter came across as something remarkable. Unlike earlier reviewers, Jervis did not pass comment on the commercial value of this work; what was most significant was its distinctive artistry.

The Encyclopedia of Ceramics was published later in 1902.12 It contained significant entries on some of the leading English potteries, such as Doulton, Minton, Pilkington, Wedgwood, as well as articles on individual designers or potters, past and present: Thomas Allen (retired Art Director, Wedgwood), Léon Arnoux (retired Art Director, Minton), Walter Crane, William Burton, Charles Binns, Taxile Doat, Sir Edmund Elton, the Martin brothers, Bernard Moore, Frederick A. Rhead, Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon and George Tinworth were all included. With little more than four years’ experience, Moorcroft’s inclusion in this volume says much about his status as a designer and the immediate impact of his work. Added to which, the Encyclopedia carried illustrations of seven pieces of Florian ware, more images than for any other designer. But most striking of all is the fact that the article was listed under Moorcroft’s own name; he was identified not as the employee of Macintyre’s, but as a designer in his own right.

This explicit focus on Moorcroft as an individual designer was soon repeated in the British art press. A substantial article by Fred Miller, author of ‘Pottery-Painting’ (1885), clearly distinguished his work from the ‘torpid uniformity […] of manufactured art’; it was pottery ‘once more expressive of our higher aspirations’.13 An extensive quotation from Moorcroft focussed above all on the individuality of his wares, made possible precisely by the production methods adopted; to work by hand, on the unfired clay, brought the artist in direct contact with the material itself:

‘Perhaps no other material is so responsive to the spirit of the worker as is the clay of the potter, and my efforts and those of my assistants are directed in an endeavour to produce beautiful forms on the thrower’s wheel, the added ornamentation of which is applied by hand directly upon the moist clay. This, I feel, imparts to the pottery the spirit of the art-worker, and spontaneously gives the pieces all the individual charm and beauty that is possible, a result never attained by mechanical means.’14

Moorcroft’s use of the term ‘art-worker’ tellingly evoked the Art Workers’ Guild, a forerunner of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, and it underlined his conception of production as a collaborative exercise, the designer and his ‘assistants’ working in harmony. It was to this spirit of a shared and focussed project that Miller attributed the energy and naturalness which he identified in Moorcroft’s work, and which expressed perfectly the vitality of the designs:

Mr Moorcroft has apparently trained his staff to good effect, for the lines on some specimens I have examined have a nice swing about them, and flow with a certain nervous freedom which is too often absent in pottery.15

This was quite different from the vision of modern industrial practice painted by Crane, where the division of labour was seen to depersonalise all aspects of production: ‘The effect of this is to throw the designer out of sympathy with the use and material of his design […], while it turns the craftsman or mechanic into an indifferent tool.’16

But Miller understood that the distinctiveness of this work lay not just in its execution, but in its design. Like critics before him, he drew attention to Moorcroft’s integration of ornament and object, a quality whose absence was often lamented in industrial ware.17 And he stressed, too, his skill as a ceramic chemist. Moorcroft understood the composition of glazes as well as he judged the harmony of colours; his ware was characterised by its subtlety, not its brashness. This was art pottery with a difference, art for the discerning eye:

The glaze of Moorcroft ware is as hard as salt-glazed ware, and the palette is therefore restricted, there being few metallic oxides that will bear the high fire to which this ware is subjected; but this is no drawback where harmony of colour is aimed at, as the limited palette helps to secure this, and the commonness, almost vulgarity, of much ‘art’ pottery is avoided by this enforced reticence.18

And behind all this, he discerned what Crane called ‘the spirit of the artist’, that desire ‘not merely to produce but to express‘.19 He did not examine particular designs, but he implicitly likened their conception and impact to that of poetry, alluding to Shakespeare’s evocation of poetic inspiration in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, V.1. 12–17:20

[…] the reproductions of a few examples of ‘Moorcroft’ ware accompanying these notes will enable the reader to gain some slight idea of what this ‘fine phrenzy’ becomes when it has ‘a local habitation and a name’.21

Fig. 22 William Moorcroft, Florian designs illustrated in Miller’s article which exemplify the harmony of form, ornament and colour: 4-handled vase with Narcissus design (1902), 12.5cm; Crocus (1902), 17.5cm. CC BY-NC.

In both design and its realisation, the presence of Moorcroft was to be found, which is doubtless why Miller could refer in the article to ‘Moorcroft ware’; the designer was given an entirely separate identity from the manufactory which produced his work. It is quite significant that there was just one reference to the ‘Washington China Works’, and no mention at all of J. Macintyre & Co., Ltd.; William Moorcroft was making a name for himself, and not just metaphorically.

He was clearly delighted with the article, and sent copies to his most important retail contacts, not least Arthur Liberty and Arthur Veel Rose of Tiffany. Rose visited him just a few weeks later, and in December 1903 he published in the American journal China, Glass and Pottery Review an article, ‘Florian Art Pottery’. Its opening clearly situated Moorcroft’s ware at the forefront of English art pottery:

While visiting the English potteries last spring, few of them interested me as much as Messrs McIntyre’s [sic] Washington China Works at Burslem, Staffordshire, where W. Moorcroft has entire charge of their art department. He is an artist-craftsman of high order and a chemist of exceptional ability […].22

Rose drew much of his material from Miller’s article, but what he underlined, too, was the enterprise of a designer who dared to be original:

Each succeeding year has seen marked improvement in his productions, and today he is producing one of the most original and charming art potteries in the market, daring in its boldness, yet with a harmony of color and design that stamp him at once an artist of rare ability.23

If much contemporary pottery was marketed as ‘art pottery’, that categorisation was seen to be rarely merited. Moorcroft’s ware, though, was breaking new ground in technique, colour and design, and this was recognised both at home and abroad. Rose’s conclusion was categorical: ‘Florian art pottery is a chemical and artistic triumph, and Mr Moorcroft’s work must be classed with the finest of modern ceramic productions.’24

The following year brought another significant article devoted to Moorcroft’s ware, published in the main British trade journal, the Pottery Gazette. The journalist, William Thomson, commented first on the electrical porcelains for which Macintyre’s were clearly well known, but it was Moorcroft’s name that was destined for the history books:

Messrs. Macintyre make a large number of electrical and other specialities […]. But the company have another very important department devoted to the production of artistic ceramics. This branch is under the personal superintendence of Mr William Moorcroft, an artist who has already made a name for himself, which, whatever now happens, will in the future be classed with the most famous art potters of the country.25

Like Miller, Thomson sought to explore what gave this ware its distinctive quality. It was not just a question of being ‘novel’, of being different from the ware of other firms, nor was it the inevitable result of a replicable technique:

I understand most of the designs are registered, but Mr Moorcroft has neither patented nor registered his method of producing his beautiful effects. He lets you see him do the primary, and most essential, part of the work, and tells you how it is completed. But you cannot ‘go and do likewise’.26

The unique qualities were seen to be the result of human intervention at each stage of production. Thomson gave an account of Moorcroft’s distinctively varied roles as designer, artist and chemist, each requiring the sensitivity of a craftworker; none was susceptible to mechanisation, each was marked by personal touch:

[…] the artist-potter himself adds the outline of the design intended in white ‘slip’. The only ‘secret’ process (in addition to the inimitable skill of the artist) occurs at this stage, and lies in the chemicals employed to secure the marvellous coloured results after firing the ware at the high temperature required to give the necessary density to the body.27

It was in this context that Thomson drew attention to that other distinctive quality of Moorcroft ware, the handwritten signature on the base of each piece. It was a guarantee of authenticity, but it was the final sign, too, of the designer, implicit in every stage of production and explicit now in the mark of his hand:

Every piece of Florian ware bears Mr Moorcroft’s signature, and if it did not, each piece carries with it the impress of his skill. Each design is absolutely the work of his own hand, while the decorative detail is carried out by trained artists under his personal supervision. He examines the work in its various stages, and passes each finally before it is fired.28

Moorcroft was applauded as a ceramic chemist, his manipulation of colours winning the same kind of approbation as the glaze effects of Burton, Howson Taylor, Noke or Moore. But he was admired above all as a designer. These articles did not assess the ware as a commercial commodity, they sought instead to understand what made it both unique and inimitable. It was ware which defied description, but it was commanding attention.

And it was selling. The interest of critics was clearly reflected in the retail world, as Moorcroft’s ware continued to attract commissions from leading stores. A diary entry for 28 February 1902 marked the beginning of one of his most exclusive relationships; it was with F. & C. Osler, retailers of ornamental glass whose store on Oxford Street was one of the most majestic (before the arrival of Gordon Selfridge in 1909). E.W. Watling wrote on 5 April 1902 to discuss the name of ware which Moorcroft would make exclusively for them, with its own distinctive palette of blues and pinks; the range would become inseparably associated with the firm:

As to the name for these things, I am still at a loss as to what to suggest. How does ‘Hispalian’ strike you? (taken from the name of an old Persian city). Or Hesperian, from the Garden of Hesperides? […] Please let me know what you think.

Moorcroft’s diary on 3 May 1902 recorded the final outcome: ‘Hesperian’.

Fig. 23 William Moorcroft, Daisy design in Hesperian palette for F. & C. Osler (1902), 12cm. CC BY-NC

And despite growing competition in the export market, Moorcroft won the attention of fashionable retailers abroad. In 1901, he made contact in Paris with another major dealer in exclusive china and glass ware, Ernest-Baptiste Léveillé, owner of an elegant showroom at 140 Faubourg Saint-Honoré; and he supplied wares to Louis and Marthe Demeuldre-Coché, one of the leading porcelain producers and dealers in high-quality tableware in Brussels. His reputation in the US also continued to grow, and he was now dealing with some of the most select retailers and importers of the age. His diary for the spring of 1901 recorded a number of contacts in New York: Tiffany & Co., Ch. Ahrenfeldt (major importers of Limoges and other china), and Ovington Brothers (celebrated china importer). His ware was actively promoted, too, by Jervis, who wrote enthusiastically on 23 February 1902:

I have had pleasure in speaking of Florian to several, or rather many, good houses in the trade, and I quite think you will derive considerable benefit from the same. Louis Reizenstein, Allegary, Pa will probably see you in the course of the next 3 or 4 weeks. […] Commercially, I class him as one of the best judges of ceramics in America.

The Charles Reizenstein Co. was an internationally renowned glass and china importer, and Louis, son of the founder, was a recognised authority in these areas; this was another major contact for Moorcroft, and it was followed up. By 1903, he was dealing with a wide range of outlets, both specialist and departmental, his diary for that year noting orders from, among others, Spaulding & Co., Chicago (goldsmiths, with a Paris branch at 36, avenue de l’Opéra, next door to Rouard), Marshall Field & Co., Chicago, John Wanamaker, Philadelphia, and A. Stowell & Co., Boston (retailers of gold clocks, silverware and jewellery). These contacts, and many others like them, were all the more remarkable as they were made at a time of declining exports to the US, and the prominence of native potteries, not least that of Rookwood, whose international reputation continued to grow. In an interview with the Pottery Gazette, the potter John Ridgway offered this blunt assessment of the market:

As things stand at present, the States have shut out practically everything in the way of English pottery which they cannot make for themselves. The stuff they have not shut out is stuff they want, because they cannot manufacture it themselves.29

Moorcroft’s ware was too individual to be manufactured by US potters, but it was self-evidently ‘stuff’ which the American market wanted.

3. Recognition and Reward

Moorcroft’s development and promotion of his ware was undertaken in an environment which was clearly both harmonious and supportive. The death of William Woodall in 1901 marked the end of an era, but Moorcroft continued to work very productively with Henry Watkin, at a personal as well as a professional level. Time spent together was of significant enough note to warrant entries in his diary:

8 April 1901: Mr Woodall died, early morning. Walked across Downs at Barlaston with Mr Watkin.

31 March 1902: Drove round Orme’s Head with Mr Watkin, morning, and walked over Little Orme in afternoon.

27 December 1903: Spent day with Mr Watkin.

And in May 1902, he went to London with Watkin to deliver a Coronation mug to the King; their professional and social lives intersected in harmony.

This personal encouragement was echoed, too, at an institutional level. Following Woodall’s death, the Directors gave Moorcroft a memento of their highly respected Chairman, a sign of the value they placed on their designer’s association with the firm. And on 29 January 1902, Henry Woodall asked him to show his brother-in-law ‘some of your lovely things’. Moorcroft’s department benefited too from practical support. On 29 July 1902, a Minute reported an increase in the allocation of money for advertising, and on 24 October 1902, Minutes of a Directors’ meeting recorded the preparation of a new catalogue. Moorcroft’s achievements in his department were recognised, too, at a personal level. On 4 December 1902, Minutes noted two resolutions which rewarded past endeavours, and offered firm encouragement for the future: ‘a cheque for £25 at Xmas’, and an increase to 2% of his sales commission. Such was their appreciation of his work that, at a meeting of 17 February 1903, the Directors agreed to reproduce the reviews first published in the Magazine of Art, dated 1899 and 1900, and ‘other articles of a similar character’; they recognised the benefit they derived from Moorcroft’s growing reputation, and their support was unequivocal.

At the end of 1903, the Pottery Gazette drew attention to this fruitful collaboration. Stressed again was the fact that Moorcroft had complete control and oversight of production. This unusual level of involvement for a designer implied as much about Macintyre’s confidence in him, as it did about Moorcroft’s conception of his role; the firm’s ideals were inseparable from Moorcroft’s own. The result was seen to be work of clear commercial and cultural value, broad in its appeal and in its benefit:

[…] dealers should assist manufacturers in still further improving the public taste. The increased sale of useful art ware, such as Messrs Macintyre and others are producing at reasonable prices, will contribute largely to that improvement.30

This was a perfect partnership, and it coincided with growing financial success for Macintyre’s. A Minute for the Annual General Meeting of 25 January 1901, Woodall’s last meeting as Chairman, recorded ‘satisfaction […] at the continued increase in the profits’. And results in 1902–03 were even better. At a meeting of 5 January 1903, figures reported for half-year sales showed growth of 9.5% over the same period in 1901–02, and growth of 11% over the equivalent quarter-year period. It was minuted that these figures represented new sales records for the Company, and from this date Monthly Returns were systematically recorded in the Minutes, the total sales figure subdivided into ‘General’ and ‘Electrical’. The Minutes of 23 July 1903 noted a very satisfactory performance for 1902–03, showing a 6.7% increase in turnover, ‘the highest turnover we have ever made’. Such was the success that, at a meeting of 26 August 1903, a 5% dividend was paid to shareholders; this was without precedent. The proportion of sales from Moorcroft’s department covered by ‘General’ is not recorded, but figures show that non-electrical sales constituted 44% of the total sales figure for the year, and that in the first half-year of 1902–03, results in this category had grown by 8.2% and those in ‘Electrical’ by 10.5%. The electrical business was clearly flourishing, but other ceramic production was not far behind. At a time of increasing competition from Europe and the US, this was a significant achievement.

The firm’s participation at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 was the natural culmination of this success. Nationally, the Fair was seen as a valuable opportunity for the pottery industry to counter the erosion of British exports to the US, and the Government was prepared to offer subsidies to that end. In a Minute of 19 January 1904, the Directors agreed to submit ‘2 cases of Florian ware’, a move supported by Gilbert Redgrave, a Macintyre Director and member of the adjudicating committee of the Exhibition. The decision paid dividends. Macintyre’s were ineligible for a manufacturer’s award, given the participation of Redgrave on the jury, but a Gold Medal, the highest award for an individual, was awarded to Moorcroft and also to Watkin, who had submitted a new design of pyrometer. In the official report on the British Section, compiled by Sir Isidore Spielmann and published in 1906, Moorcroft featured prominently in the Ceramics category. The account of his ware highlighted its ‘refinement in design and colour’, and implied the ideal partnership of designer and manufacturer: ‘Fifty-seven pieces of pottery, designed by and executed under the direction of Mr W. Moorcroft, were exhibited by Messrs James Macintyre & Co.’31

Success at St Louis was a significant moment for both Macintyre’s and Moorcroft, the culmination of their first seven years of association. But as it was happening, economic conditions continued to deteriorate in the country at large, as recession took hold in the wake of the Boer War. The profits of 1902–03 were not to be repeated in 1903–04, and as financial pressures increased, the Directors discussed on 15 March 1904 the need to reduce selling prices, clearly aware that this would mean ‘a reduction in wages’ for the staff. Growing concern about the expense of advertising was noted on 18 April 1904, and a Minute of 26 July 1904 reported a decline of 13.2% in sales. It was decided at the same meeting to close the works during Wakes week ‘owing to slackness of trade’. There seemed to be little anxiety, though. Writing to Watkin on 7 November 1904, Gilbert Redgrave offered his ‘best thanks’ for the ‘highly satisfactory’ balance sheet. Fresh from St Louis, it may well have been that Redgrave saw the future benefits of the Fair. Macintyre’s art pottery was attracting serious attention, and both Moorcroft and Watkin had won international recognition. It was a powerful and harmonious combination, and the future looked bright. But it was not to be.

5. Conclusions

This was a highly productive period for Moorcroft. His experiments in both technique and design were taking him in new directions, and his ware was winning appreciation in both artistic and commercial circles, at home and abroad. This creativity was complemented, and to some extent shaped, by two significant relationships.

His association with Liberty’s was of inestimable value. The store was not just an effective retail outlet for his wares, it was a sounding board for ideas about design, taste, and market conditions. In the commercial art world of the new century, Liberty’s continued to be at the forefront of design initiatives. Their interest in Moorcroft was a resounding endorsement of his energy, creativity and artistic enterprise; his interest in them showed his ambition to make his mark in the world of art pottery as it emerged from the Victorian age. This collaboration was as significant in the development of Moorcroft’s art as it was in the growth of his sales.

And he was developing, too, with his employer, J. Macintyre & Co., Ltd., and with Henry Watkin—an ideal designer/manufacturer relationship. Macintyre’s were wholly committed to producing ‘art pottery’, and appreciated the efforts which their young, enterprising designer was making. The Directors clearly recognised the value of what he produced, both commercial and artistic, and allowed him his individual identity as designer. The decision to re-print reviews of his work was made in the same month as Miller’s Art Journal article, which, in its very title ‘The Art Pottery of Mr W. Moorcroft’, had explicitly focussed on Moorcroft as designer. And they clearly sanctioned the absence on wares made for Liberty’s (and for Osler’s) of any mark indicating the firm’s name, leaving only the retailer’s stamp and the designer’s signature. This was in itself remarkable, especially as other pottery retailed by this store did customarily carry a manufacturer’s mark alongside their own stamp. For Liberty’s, clearly, the individuality of Moorcroft’s ware was what distinguished it above all; it was the very antithesis of industrial manufacture.

Fig. 24 William Moorcroft, Signature and retailer’s mark on base of pots made for Liberty & Co., and F. & C. Osler. CC BY-NC

Macintyre’s support was unequivocal; it was also uncommon in the pottery world. A very different picture of the designer’s lot was painted by Crane in his Moot Points: ‘I maintain that an artist—say, a designer—having his living to get, must either be prepared to meet the demands of trade, the caprice of fashion—whatever you like to call it—or starve.’32 And in an article published in the Pottery Gazette, the manufacturer’s preoccupation with profit was seen to stifle good design. Yet art, it was argued, was the safest route to commercial survival in these difficult times:

[…] manufacturers should recognise the fact that art and pottery are inseparably connected, and that it is only by an all-round improvement in art up to the highest level of the market that they can expect to survive in the long run […]33

At a time when craftsmen, both in the UK and in Europe, were exploring ways of achieving larger scale production of high-quality craft wares, setting up collaborative enterprises such as the Alliance Provinciale des Industries d’Art in Nancy (1901), the Guild of Handicraft in Chipping Campden (1902), or the Wiener Werkstätte in Vienna (1903), Macintyre’s had achieved a quite different model for the commercialisation of art. Moving beyond the increasingly uneconomic production of expensive art wares, such as Solon had created at Minton, or George Owen at Worcester, they supported a craft studio based on the work of a single designer which operated on quasi-industrial lines. And this had led to neither trivialised design, low production quality, nor financial difficulty, as early reviews were quick to point out. Nor did it require the adoption of machinery; quite the reverse. Ashbee would eventually fail, in part because he could not produce wares cheaply enough to compete with the avant-garde designs machine-produced by Haselers on behalf of Liberty’s. Not so Macintyre’s; Moorcroft’s work could not be reproduced by mechanical means.

At the turn of the century, the quest for novelty was seen to define the design ambitions of industrial artists; this was the new commercial virtue. But for Crane, it was a life of hard labour, not of creative freedom: ‘The designer is perhaps kept chained to some enterprising firm. Novelties are demanded of him—something ‘entirely new and original’ every season […].’34 Moorcroft’s relationship with Macintyre’s was quite different, and so was his ambition as an artist. Far from being ‘chained’, what was stressed in early reviews was his absolute control over the department he ran, and his freedom to create. His conception of art pottery was not defined by its quest for new-season ‘novelty’, but by the quality of its design and of its realisation, by its art and its craft. On 29 March 1904, a journalist wrote to Moorcroft proposing an article on Florian ware; significantly, he treated him not as a designer whose ambition was commercial success, but as an artist whose work expressed a creative outlook which he was keen to understand:

I would very much like to go on with ‘Florian Ware’ and I would like to combine with the article something of the manufacture which to my mind is the most interesting. I would also like to have your own opinion of the influences and ideas which you have in designing, as it is only in this way that I can write a proper article on your ware.

Even at this early stage in his career, Moorcroft was being taken very seriously. The end of Jervis’s article in Keramic Studio recognised in his work an originality and quality of great significance:

Mr Moorcroft is as yet but a young man, but this initial effort with which his name has been associated leads us to hope for yet greater things. For over one hundred and fifty years no added precious secret in ceramics has been discovered. Florian ware suggests the question to our thoughts as to whether the man and the time have arrived.35

The economic climate was challenging, but Moorcroft’s working environment was stimulating and he was full of ideas. An order from Liberty’s, dated 11 March 1904, listed items in his new designs, ‘Tudor Rose’, ‘Tree decoration’ and ‘Toadstool decoration’, and, at the end, other pieces in ‘Old Decoration’. Above this, in Moorcroft’s hand, is the annotation, ‘Florian ware’. Already, just weeks before the St Louis Exhibition which would bring him his first international award, Florian belonged to the past. Later that year, the Pottery Gazette used the term ‘Burslem Ware’ to describe Moorcroft’s new work, picking up the expression used in Liberty’s YuleTide catalogue of 1902.36 But the article ended on a different note, introducing a new name for the ware which focussed explicitly on its creator: ‘A hundred years hence connoisseurs of pottery will have reason to be proud of the possession of a signed piece of Moorcroft faience.’37 The next chapter of Moorcroft’s career was about to begin.

1 W. Burton, ‘The Pottery Trade and Protection’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (October 1903), 1028–29 (p.1029).

2 PG (November 1904), 1248–49 (p.1248).

3 W. Burton, A History and Description of English Porcelain (New York: A. Wessels, 1902), p.183.

4 Ibid., p.187.

5 ‘Ruskin Pottery’, PG (January 1903), p.53.

6 L.F. Day, ‘The New Lancastrian Pottery’, The Art Journal [AJ] (1904), 201–04 (p.202).

7 All unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

8 W. Crane, ‘Impressions of the First International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art at Turin’, AJ (1902), 227–30.

9 W.P. Jervis, ‘Florian Ware’, Keramic Studio (April 1902), 260–61 (p.260).

10 Ibid., pp.260–61.

11 Ibid.

12 W.P. Jervis, The Encyclopedia of Ceramics (New York, 1902).

13 F. Miller, ‘The Art Pottery of Mr W. Moorcroft’, AJ (1903), 57–58 (p.57).

14 Miller, ‘Art Pottery’, p.57.

15 Ibid.

16 Crane, ‘Design in Relation to Use and Material’, p.103.

17 Cf. Crane, ‘Design in Relation to Use and Material’, The Claims of Decorative Art (London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1892), 90–105.

18 Miller, ‘Art Pottery’, p.58.

19 Crane, ‘Art and Industry’, The Claims of Decorative Art (London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1892), 172–191 (pp.173–74).

20 The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven.

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

21 Miller, ‘Art Pottery’, p.57.

22 A.V. Rose, ‘Florian Art Pottery’, China, Glass and Pottery Review, 13:5 (December 1903), n.p.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 ‘A Short Visit to the Potteries’, PG (October 1904), 1114–15 (p.1114).

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid., p.1115.

28 Ibid.

29 ‘Mr John Ridgway on the Fiscal Question’, PG (February 1904), 193–96 (p.194).

30 PG (December 1903), p.1220.

31 I. Spielmann (ed.), St Louis International Exhibition 1904. The British Section (Royal Commission, 1906), p.329.

32 W. Crane, Moot Points: Friendly Disputes on Art & Industry between Walter Crane and Lewis F. Day (London: Batsford, 1903), p.34.

33 ‘The Present Position of Pottery among the Crafts’, PG (August 1904), 898–99 (p.898).

34 W. Crane, ‘The Importance of the Applied Arts and their Relation to Common Life’, The Claims of Decorative Art (London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1892), 106–122 (p.115).

35 Jervis, ‘Florian Ware’, p.261.

36 ‘A Short Visit to the Potteries’, PG (October 1904), p.1115.

37 Ibid.