5. 1912–13: Breaking with Macintyre’s

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.05

1. Winning Time

When Macintyre’s Directors met on 4 October 1912, it was reported that the new financial year had started well, and that there had been ‘an improvement in every direction’. But such improvement evidently did not include Moorcroft’s department; giving less than three months’ notice, the decision was taken to close it down:

A letter having been read from Mr Moorcroft, the Secretary was instructed to inform him that the Balance Sheet shows his Department to be unremunerative, and in consequence the Directors were reluctantly resolved to close down the Department at the end of the year […].1

A letter written the following day from Corbet Woodall, Chairman of Directors, confirmed the financial motive for the Directors’ decision: the Department was ‘unproductive of profit’, and the consequence, therefore, ‘inevitable’. Woodall’s expectation was doubtless that Moorcroft would find employment in another firm, as Harry Barnard had done nearly twenty years earlier, and he implicitly acknowledged that Moorcroft may not have been adequately appreciated, or rewarded, at the Washington Works:

[…] I have learned to esteem not only your work but yourself so highly that I find it difficult to express, parting with you will be a real sorrow. I am comforted in one respect that I am assured that you have given us your services at a rate of remuneration decidedly below that which they would command elsewhere. I hope this will prove so and that the future before you is one of increasing distinction and prosperity.

Moorcroft’s note in his diary for 7 October was ironically matter-of-fact: ‘Received letter from Mr Woodall re department.’ But this was a devastating blow, and on 12 October, he drafted his reply. The extent to which the Directors’ decision was, in fact, a surprise is not clear, but his disappointment was palpable; and he would fight back: ‘The decision of your Board came as a great surprise. There is something wrong, and the future I feel will reveal this.’

Moorcroft did not agree with the verdict that his department was ‘unremunerative’. Nor, perhaps, did Corbett Woodall, son of the Chairman, who, in a letter of 2 November 1912, stopped short of endorsing a view which he attributed explicitly to Henry Watkin: ‘The Managing Director is fully convinced that the department is run at a serious loss, and, I think, that it always has been (That is, I believe Mr Watkin is of opinion that it has always been a loss).’ Woodall’s position was both regretful and supportive; Moorcroft’s department may be on the point of closure at the Washington Works, but he had no desire to see the end of Moorcroft’s pottery. In a subsequent letter, Woodall gave him the option of taking with him his staff and all essential equipment. Moorcroft understood the significance of this gesture, but if he was to continue production, he needed not just his staff, he needed time: to create a viable plan, to find a site to relocate, and to secure financial support. He wrote to Woodall on 16 November in anticipation of the next Directors’ meeting. To win an extension of time beyond December 1912, he had to persuade them that he was not simply seeking to pursue his own interests at their expense. He sketched out a proposal in which they might be profitably involved, but without financial investment: ‘I would very much like to build on your land at the back of the present works on any terms agreeable to you.’ A draft paper, headed ‘Re. Dept’, gave further details. Moorcroft would buy clay from Macintyre’s, share the services of the firemen, and even rent space at the Washington Works for the clay and decorating shops; but he would have his own financial and administrative independence, and his own kilns. The proposed firm was not even given the Moorcroft name; it would be called ‘James Macintyre 1912’.

But he also needed to counter the perception that his department was loss-making; the Directors would never agree to delaying its closure, if to do so would simply increase a deficit on their balance sheet. Moorcroft’s many surviving drafts of his letter of 16 November 1912 all underlined his belief in the department’s economic viability, as yet not fully realised:

My evenings have been spent in finding new outlets for the production and during the last few years I have made sales to the value of some four thousands of pounds. Chiefly for abroad. There would be found in England an opportunity for a great output. I have much evidence that would confirm this opinion, and also that would explain the causes of a stultified development.

This line of argument took Moorcroft down a particularly hazardous path. One draft implied very strongly that the Managing Director had not in fact always believed, as Woodall clearly thought, that Moorcroft’s department was unprofitable. Quite the reverse:

May I further add, one can recall proposals of some years ago which convince me it has not always been the opinion of the Managing Director that the department was unremunerative. The fulfilment of the suggestions then made depended entirely upon the successful working of that which is now called in question.

And an earlier draft of this same section, written significantly in Alwyn Lasenby’s hand, even refers to arguments (‘passages’) with Watkin about these ‘suggestions’:

I am precluded from believing otherwise by my very clear recollection of some passages between myself and Mr Watkin a few years ago which conveyed to me from Mr Watkin suggestions for joining [in] independent action with him which would have rested upon the character of my work as its justification. […] the lack of success, if such there has been, in my efforts for the Directors has not arisen from the character of my work or its inadaptability to a market.

What kind of ‘independent action’ Watkin may have proposed to Moorcroft, and when, is not recorded, but it was clearly a source of dispute between them, and Moorcroft evidently declined to pursue it. If an explanation was sought for the ‘stultified’ development of his department, he was implying, it was not to be found in the unprofitability of his ware.

The James Macintyre 1912 project is not mentioned in any other surviving documents, but Moorcroft’s letter had the desired effect; Woodall wrote to him on 21 November to record an extension of the deadline. It was a concession of enormous practical significance, but it implied too, at some level, a belief in Moorcroft’s ware as a worthwhile, and viable, enterprise. On 25 November, he drafted another letter to Woodall. He recognised the exciting potential of his own independent works, but he was conscious, too, of the challenges ahead:

I have to find the capital which I roughly estimate at £10,000, and follow with the building. It is my hope to erect a modern works complying with all the new conditions just now demanded by the Home Office. […] I am risking all I have to keep together the workers who have been specially trained during the 16 years. It is in their interest as well as my own I beg for your special consideration.

Moorcroft needed the support of the Woodalls, but he also needed financial backing; without it, there could be no future.

2. The Search for Funding

It is not certain when Moorcroft first had the idea of approaching Liberty’s, but he had clearly done so by the time of his letter to Woodall of 16 November 1912:

On Tuesday afternoon, I met three of the directors of Messrs Liberty & Co. […] I had given them no previous intimation of my visit or the object of my visit, but they met me very courteously and I was requested to put before them a statement of the probable cost of building a modern works and the amount of capital necessary with as little delay as possible, and to submit the same to their secretary who is also their legal adviser. At such short notice, I am grateful for their action.

Over the following weeks, Moorcroft and Harold Blackmore, the Company Secretary (and Arthur Liberty’s nephew by marriage), exchanged letters about sales, costs and turnover. Drafts of Moorcroft’s letters emphasise the financial potential of his project. A move to his own modern works would create a more economical mode of production, increased output and, it was implied, more effective marketing. But he was clearly under pressure from Liberty’s to keep the costs down. In a letter of 16 December, Blackmore summarised Moorcroft’s estimates for set-up and initial running costs which were already 20% lower than the figure of £10,000 he had indicated in his letter to Woodall just three weeks earlier:

I am in receipt of your letter of the 14th inst., which seems to confirm the figures we got out the other day […] So that up to this point you would want:

|

For the factory |

6000 |

|

For three months working expenses |

1000 |

|

For credit purposes on your books and general reserve |

1000 |

|

Total |

8000 |

And this pressure was sustained. Moorcroft instructed Reginald Longden,2 the architect of the new works, to scale down his initial scheme for a building with three ovens and two kilns. On 20 December he was sent a revised estimate of £4,850; the cost had been cut by a further 20%, and the provision reduced to two ovens and one kiln. Blackmore wrote again on 23 December; Liberty’s Directors were prepared to invest about half of the estimated costs, but before proceeding, Blackmore needed a meeting with the Macintyre Directors to scrutinise the finances. His letter was fair and unambiguous:

We are particularly anxious not to lead you astray by this letter. The only position which we really can take up at the moment is that we are quite disposed to look further into the whole thing and if all our enquiries result in satisfactory answers, then our Board would be prepared to consider a definite financial proposal on the lines that I discussed with you. […] We must leave it to you to decide whether you think it worthwhile to go further into the matter with us on the chance of our joining in with you […].

That Moorcroft had persuaded Liberty’s to go this far says much about the reputation of his work, but there was still some way to go. Blackmore left him the chance to look for support elsewhere, but Moorcroft had very little choice; if Liberty’s did not agree, he had no alternatives in play.

At the start of the New Year, knighthoods were conferred on both Corbet Woodall and Arthur Liberty. Moorcroft wrote to Woodall on 1 January 1913 expressing the hope that this coincidence may prove to be ‘a happy augury for the proposed amalgamation’; he wrote the next day to Liberty. The Woodalls shared this hope. On 2 January, Woodall reported very positively on a recent meeting (on 31 December 1912) with Liberty’s, and when Sir Corbet Woodall wrote on 6 January to thank Moorcroft for his letter, he added his own wish to see ‘a settlement, entirely satisfactory to you, of your professional career’. But when, on 9 January, a meeting brought together Liberty’s Directors, Woodall and Watkin, the outcome was a disaster. Blackmore wrote to Moorcroft that same day, ending their association before it had even begun:

We have seen Mr Corbett Woodall and Mr Watkins [sic] today and they have given us certain figures which they are prepared to verify from the books. Messrs Macintyre’s financial year finishes in July, in each year, and the figures for last year are so very much below your estimates that we are afraid it will put an end to our Board entertaining the matter.

Watkin’s figures (and their accuracy) cannot be verified, but the message they conveyed was unequivocal: Moorcroft’s pottery was unprofitable. With a grim irony, on 10 January, the day after Blackmore’s letter, Longden wrote to report that ‘the plans for your factory are now well in hand’.

Moorcroft’s project was in shreds, but he took immediate action. He arranged a meeting with Liberty’s (for 13 January 1913), and on the same day he wrote to Corbett Woodall, requesting an interview. On 15 January, Blackmore wrote again, giving a more nuanced explanation for the decision to withdraw from the project:

We have, rightly or wrongly, formed the opinion that when you actually come to break off with Macintyre’s, a good many obstacles will be put in the way of the transaction going through smoothly, and we very much doubt whether the true benefit of the goodwill of that part of the business which you are to take over will fall to your share, and it is partly on this account that we have decided to stand out.

Liberty’s misgivings were clearly not just related to the (disputed) profitability of Moorcroft’s department, they also concerned the cooperation of Macintyre’s. If his plans were to be revived, Moorcroft would have to devise an even smaller-scale business model, but he also had to persuade Liberty’s that Macintyre’s were committed to the smooth transfer of his department to a new factory. The Woodalls were quick to react. In a letter of 16 January, Moorcroft thanked Corbett Woodall for his undertaking ‘to assist [me] to regain their confidence’, and on 21 January Sir Corbet wrote after a meeting of Directors, explicitly allaying the fear of ‘obstacles’ voiced by Blackmore:

If it is of service to you, you are quite at liberty to tell Messrs Liberty & Co. that the Directors of James Macintyre & Co. will put no obstacle in the way of the transfer of the Florian Department.

Woodall also repeated the Directors’ undertaking not to continue production of art pottery at the Washington Works after Moorcroft’s departure. Curiously, there was no record of this resolution in the Minutes; what was recorded, however, stood in stark contrast to Woodall’s letter:

It was decided to advise customers that the manufacture of Florian ware was abandoned, and to offer £5 lots at reduced prices to clear stocks.

To announce, before any plans for continuation had been established, that the production of Florian ware was ‘abandoned’, and to sell off old stock, would scarcely facilitate the successful transfer of Moorcroft’s department, but it might easily hasten its demise. Blackmore’s concerns were doubtless well founded.

On 25 January 1913, Moorcroft wrote to Lasenby, hoping to build on Woodall’s affirmation; and he instructed Longden to reduce by a further two-thirds his costing for the new building. Two days later, Longden had drawn up a revised estimate for a much smaller factory, comprising:

Potter’s shop, clay decorating, one Hot house divided for both the latters’ use, Office, one 10 feet oven to be used alternately as bisque and glost, Rooms 16 feet square for the purpose of bisque and glost warehouses, dipping, decorating, and male and female Mess-rooms and lavatories, respectively. There will also be one kiln and small shed.

An undated paper, headed ‘Summary’ lists items in this new scheme, including both building and running costs; provision for building had been cut from £6,000 to £1,400, estimates for working expenses more than halved, and the total capital needed reduced by nearly three quarters. On the same day as Longden’s letter (27 January), Woodall wrote again to offer support at a further meeting with Liberty’s; such assistance implied his unshaken confidence in Moorcroft’s project, if not a tacit acknowledgement that Watkin’s attitude was not his own. The following day, just fifteen days after receiving Blackmore’s letter, Moorcroft wrote to Lasenby, hoping to persuade Liberty’s with his new plan. He considered Watkin’s financial picture to be misleading and obstructive, and he was determined to counter this:

My present proposal will overcome all the difficulty unhappily presented by the Managing Director, and the outlook is brighter following his attempt to stifle the development.

The plan was discussed by Liberty’s Directors on 11 February; the next day, Blackmore wrote to propose a deal. On 13 February, Moorcroft simply noted in his diary: ‘Received letter from Liberty re. new works.’ It was a remarkable reversal of fortune. To recover from the seemingly irrecoverable failure of his first scheme, to move from a large project (requiring immediate capital of nearly £7,000) to a small one (which needed just short of £2,500) in just over six weeks, shows determination, vision, and clear self-belief. But it also implied the assistance of others. There is evidence of interventions from both Lasenby and the Woodalls, and one senses too, although there is no archival trace, the decisive support of Florence.

3. Growing Tensions at the Washington Works

With funding in place, the next step was to build the new factory; Liberty’s, with its major investment in the project, would be actively involved. The plan of the factory itself had been drawn up; the last element was the land. The original plan to build on land behind the Washington Works was clearly abandoned, and when Blackmore wrote to Moorcroft on 14 February 1913, he referred to a new site, owned by the Sneyd Colliery. Longden sent plans on 20 February, but the next day the land deal fell through; marl had been discovered in the soil, its high moisture content making it quite unsuitable for building. Within days, Moorcroft was inspecting other sites, and by 3 March, he had settled on an alternative plot, writing to R. Bygott, clerk to the Sandbach School Foundation, with a request that he ‘sell about three thousand three hundred yards of the land now and give to us the option to purchase the remainder of the suggested plot in the near future.’ On the same day, appropriately, Moorcroft took another decisive step forward, signing a contract of employment with James Newman, his thrower; his project was taking shape. But the 30 June deadline was now little more than sixteen weeks away. On 10 March, Blackmore wrote to Woodall with news of the new site, but hinting that completion may be delayed. Moorcroft’s relationship with Macintyre’s was by this time, and for quite different reasons, under considerable strain; the prospect of a delay did not help to defuse the tension.

The land site was ideal, but at an agreed price of two shillings per yard, it was nearly 14% higher than Moorcroft’s original estimate (of one shilling and nine pence), thus increasing the pressure to keep building costs to an absolute minimum. In a letter to Longden of 17 March 1913, he stressed that ‘every possible economy must be enforced’. Ending with a personal postscript, the strain was clear: ‘I beg you to help me to get a building that will be well worth the money expended. I am putting my all into this scheme’. To make matters worse, the sale transaction was painfully slow. On 12 April, just seven weeks from the end of June, Moorcroft wrote again to Longden; he had a contingency plan, but he was keen to avoid it at all costs:

We must be in a position to move into the building by the end of June, or earlier. Could we occupy a portion with any satisfaction, we could work without the oven for a time. In case of doubt, we shall be compelled to take the Ducal Works and have the same put in some state of repair. This expense we must avoid if possible.

On 14 April, Bygott confirmed that a draft agreement of the land sale had been sent to Blackmore; but Blackmore was reluctant to incur building expenses before the sale had been completed. Writing to Moorcroft on 6 May, he revealed an enduring concern that Watkin might yet seek to undermine the plans; it was a remarkable admission:

As far as I can judge, the only way in which the Governors of the School Foundation could now get out of the sale would be by persuading the Board of Education to refuse their consent to the sale. I do not know how far this local body would be likely to be influenced by anything that Mr Watkin might say or do […].

But by 9 May, Moorcroft had instructed Longden to proceed. The contract with Joseph Cooke, the builder, was dated 13 May, the cost set at £1,400, and completion within nine weeks; this put back the termination date to 15 July, more than two weeks beyond the date agreed with Macintyre’s. The land sale was not finalised, however, until the 30 May, delaying completion, then, by a total of four weeks.

The collapse of the Sneyd Colliery land sale inevitably put pressure on Moorcroft’s relations with his employers; this was significantly increased when a notice was published in the Pottery Gazette, reporting the proposed transfer of his department. When Moorcroft wrote to Woodall on 1 March 1913, informing him of the failure of the land purchase, he told him of a forthcoming announcement in the Pottery Gazette:

A fortnight ago, a journalist from the P.G. called at the works on his usual annual round, and I explained the position […] that when he came next year he would find a change, and he has included a short paragraph in this month’s issue. I have not seen a copy, but will send you one if I am able to obtain it.

Moorcroft was anxious to give notice of the transfer to customers, not least in order to counter the earlier announcement of its discontinuation and the ready availability of cheap stock. He had no reason to fear that the Directors might object, since he knew that all press notices were sent in draft to Watkin for his approval or amendment. But this notice caused a storm:

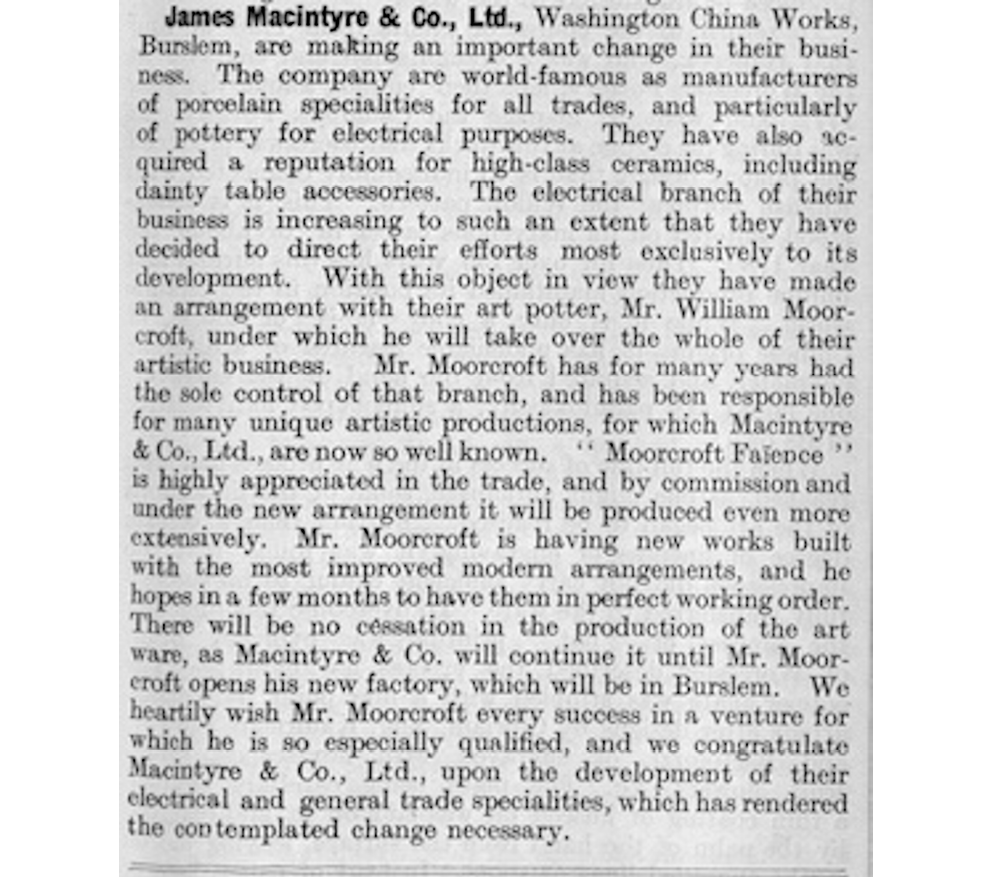

‘Moorcroft Faience’ is highly appreciated in the trade, and by commission and under the new arrangement it will be produced even more extensively. Mr Moorcroft is having new works built with the most improved modern arrangements, and he hopes in a few months to have them in perfect working order. There will be no cessation in the production of the art ware, as Macintyre & Co. will continue it until Mr Moorcroft opens his new factory, which will be in Burslem.3

Fig. 41 Announcement of the new factory in the Pottery Gazette (March 1913). ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

The statement that Macintyre’s would continue production of art ware ‘until Mr Moorcroft opens his new factory’ clearly implied that their support of Moorcroft’s interests was unconditional. But against the background of the failed Sneyd Colliery land sale just four days earlier, it inadvertently implied a commitment which was not only one-sided, but open-ended. Woodall replied to Moorcroft’s letter on 3 March: ‘There is a most extraordinary article in the ‘Pottery Gazette’ dated 1st March, which is so incorrect I feel sure it cannot have emanated from you.’ In this context, Blackmore’s letter to Woodall of 10 March, announcing the imminent land deal with Bygott, but preparing the way for a possible delay in the completion of the transfer, could not have come at a more inopportune moment. Woodall may have been accommodating at the meeting in early February, when the Sneyd Colliery land deal was imminent, but since then the situation had changed. Blackmore’s re-statement of Woodall’s helpful assurances must have seemed inappropriately unconcerned, even exploitative:

[…] although we are in hopes that the new factory will be up and in working order by the end of June, it is just possible that there will be, as you know there often is, a certain amount of delay, and if that is the case, we may have to ask the indulgence which you were so good as to say that you would afford us.

Moorcroft established that a proof of the Pottery Gazette notice had not on this occasion been sent to Watkin for his approval, a result of the journalist’s sudden illness. The impression remained, however, that he had acted independently. Moorcroft drafted a letter to Woodall on the 24 March 1913, assuring him that he had played no part in the writing of the notice, and revealing at the same time a telling side to Watkin’s proof-reading practice:

I had never known what would be published until I had seen the paper. Past experience confirms this, as the censorship of Mr Watkin has been a very severe one. In one instance I recall it was so drastic that the Editor of the Art Journal declined to publish the matter. […] The Editor returned Mr Watkin’s proof to me, stating he could not publish as the content was so contrary to their opinion […] Mr Watkin struck out my name in every paragraph.

On 28 March, a special meeting of the Macintyre Directors was called ‘for the purpose of considering Mr W. Moorcroft’s position and the attitude the Company should adopt in dealing with Messrs Liberty & Co. and the Pottery Gazette’. This was not just about the publication of an announcement; it was about Moorcroft’s relationship with Macintyre’s, and Macintyre’s relationship with his new project and with his powerful sponsor. The impression had unintentionally been given that their support was being taken for granted, and the Directors were naturally keen to set down its limits. It was decided that no further extension to the end of June deadline would be granted, and that Woodall would inform Blackmore of this; curiously, he did not do so until 24 April, nearly four weeks later. As for the Pottery Gazette, it was agreed to make a public statement in the journal, underlining the termination of Moorcroft’s engagement and with only a passing reference to his independent future:

We are requested by Messrs James Macintyre & Co. Ltd. of Washington Works, Burslem, to state that the paragraph relating to their business which appeared in our March number was inserted without their knowledge; and they wish it to be understood that Mr Moorcroft who is leaving their employment and intends to commence business on his own account will not in future have any connection with their firm or be entitled to use their name for any purpose whatever.

But this was not all. Problems arising from Moorcroft’s participation at the Ghent Universal Exhibition were coming to a head in the same month of March. Moorcroft had always seen the value of international exhibitions, but he had failed to persuade Watkin to apply for space at Ghent. At the same Directors’ meeting of 4 October 1912 which agreed the closure of his department, a Minute recorded the firm’s decision not to participate. As a result, Moorcroft applied to exhibit independently, as a means of promoting ware which would soon be manufactured in his own name. But then, at a meeting of 21 November 1912, the Directors reversed their earlier decision not to exhibit. This put Moorcroft in a delicate position, his twin status as employee of Macintyre’s and (soon to become) independent potter now brought uncomfortably into tension. Tension became opposition when, at the Directors’ meeting of 28 March 1913, Watkin announced his decision to withdraw:

It was reported that the Board of Trade had allotted two cases out of the four applied for: when asked for a reason for the reduction of the number, the explanation was so unsatisfactory the Managing Director decided to withdraw entirely and to exhibit nothing.

Whether the ‘so unsatisfactory’ explanation offered by the Board of Trade included reference to the space already allocated to Moorcroft’s independent exhibit is not documented, but it cannot have strengthened the case of his (not yet) former employer; and it would certainly have increased the impression that Moorcroft’s actions were adversely affecting their plans. This perception may well have prompted Watkin to reject Moorcroft’s request to buy stock for display in his own name, and on 4 April, Moorcroft drafted a letter to T.C. Moore at the Board of Trade, withdrawing from the Exhibition: ‘[I] deeply regret that owing to unforeseen delay in the transfer and in building operations, I fear it will not be possible to make the pottery in time to exhibit at Ghent.’ Within days, though, his diary recorded a new solution: wares would be supplied from Liberty’s stock.

These two disputes added to the pressure Moorcroft was already under from the immediate, practical issues of buying land, designing a factory and negotiating terms with Liberty’s. Both originated in his desire to advertise his new venture, to win orders and to effect, as smoothly as possible, the transfer of his business. How much of the increased tension with Macintyre’s was due to misunderstanding, and how much to conscious misrepresentation, cannot be known, but by the end of March 1913 good relations had broken down completely. This was most tellingly reflected in the changing text of Macintyre’s advertisements in the Pottery Gazette. In March the Company name had been followed with the statement ‘Manufacturers of High-Class ceramics. New and distinctive designs on original shapes’. In April, though, even this anonymised reference to ‘High-Class ceramics’ had been removed, its place taken by ‘Highest Grade Electrical Porcelains’. All trace of Moorcroft’s department had been erased.

Fig. 42 J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd., Advertisements in the Pottery Gazette March & April 1913. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

|

|

(L) Fig. 43 Notice of dismissal sent to Fanny Morrey, one of Moorcroft’s most senior decorators. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 44 Official announcement of the new works. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Ironically, these disputes were taking place on the eve of the much heralded visit of the King and Queen to Stoke on the 22 and 23 April 1913; at its meeting of 28 March, the Directors had agreed that ware from Moorcroft’s department should be sent for inspection by the Queen, including ‘one choice piece for her acceptance’, a tacit recognition of its quality even as the firm edged closer to its closure. On 24 April, Moorcroft wrote to Sir Corbet Woodall, informing him that the Queen had accepted the gift of two [sic] pieces of his ware, ‘a quaint teapot with pansies on a white ground and a pot pourri jar with a design of pomegranate and vine’. On the same day, Woodall (finally) wrote to Blackmore the letter agreed at the Directors’ meeting of 28 March, confirming that the June deadline for Moorcroft’s departure would not be extended. Blackmore replied the next day, calmly pointing out the importance of keeping the workforce together:

[…] it is very doubtful whether we shall be able to get the buildings sufficiently forward by the end of June to actually go into occupation, and you will realise the difficulty in which we shall be placed in keeping the workers together if we have nothing for them to do.

Blackmore’s use of ‘we’ was eloquent and assertive. Liberty’s were fully invested in this project; to make life difficult for Moorcroft was to make it difficult for them, and they would have none of it:

Had we not felt perfectly certain from your statements to us on more than one occasion that the parting with Mr Moorcroft was to be carried out in such a manner as to give those who were prepared to finance him every opportunity of keeping the business together, we should have never entertained the proposal for one moment.

Blackmore’s letter was persuasive. When the Directors met on 29 April 1913, an extension was agreed to the end of July. Moorcroft met Corbett Woodall at the works that same day, the day before his wedding to Florence, recording in his diary a flexible attitude: ‘Met C.W. Woodall at works. He agreed to our working to the end of July and a little more if necessary.’ Sir Corbet Woodall’s letter to Blackmore, though, was more categorical. Writing on 30 April, he implied no further flexibility in the date, and added a condition:

As I have told you on many occasions, the Board have no desire to do anything but act in a friendly spirit, and with a view to falling in with your wishes, will arrange to extend the period by one month, which will, we hope, be sufficient for your purpose. This further concession is made on the understanding that the whole of the stock made for you, and which is, of course, of no use to us, shall be taken at an early date.

Blackmore’s reply of 1 May openly declined to acknowledge the ‘concession’, and pointedly conceded nothing with regard to the stock. Tension was now clearly building, too, between Liberty’s and Macintyre’s:

We are obliged for your letter of the 30th April, and felt that when we explained the circumstances to you, you would realise the awkward position to which your proposed action was putting us. As regards the stock, […] we have little doubt that some arrangement could be made in regard to that, though at the moment we do not know what it comprises.

And yet, despite all the obstacles to a smooth transition, Moorcroft’s work continued to be appreciated. As early as 6 February 1913, Mr Ravenscroft, one of Macintyre’s travellers, reported that the (provocative) announcement of his department’s closure, agreed by the Directors on 16 January, had provoked widespread expressions of support for Moorcroft:

[…] without exception, they all say how pleased they are and will support you. The clinch of it all is, though, they won’t order now (only small) and prefer to wait and to help Moorcroft Ltd along. It is very gratifying in a way and a compliment to both of us.

And even the offer of cut-price stock did not override a sense of loyalty, a telling sign of the very personal way Moorcroft had conducted his business. Marks, a leading Manchester retailer, was uncompromising in his view:

Marks [….] showed me a letter Mr W wrote them which is only one more proof of your contention that he blocks the department all he can. […] They would not have it from him even if he went round himself and offered it at half price. [Emphasis original]

And the same was true of customers abroad. Writing with an order on 21 July 1913, William Sandover, Australian importer, pointed out the importance of Moorcroft’s name for new business:

I notice that we have received today, from Macintyre’s, an invoice of your vases, but I notice it does not mention your name. Now, I want to make a speciality of these, and I ought really to have some showcards with your name on such as ‘Moorcroft ware’. I am quite certain this will be the way to sell them best […].

Even in such difficult times, Moorcroft’s name promised to take him a long way.

What was true of the retail sector was true, too, in the world of art. Moorcroft exhibited again at the Royal Institution on 30 May 1913, his display attracting a review in The Connoisseur. When Reginald Grundy confirmed the notice in a letter of 31 May, he was clearly aware of the tensions at Macintyre’s, and his letter corroborated Moorcroft’s perception that Watkin took every opportunity to anonymise his work:

Are you on your own yet? In the notice in ‘The Mail’, I did not venture to mention that you were setting up for yourself, as your former firm might probably have protested […]. I may say (entre nous) that the notes they sent to be written up did not mention your name and barely alluded to your work, and that in a manner to give no clue whatever to the identity of the maker.

Grundy’s notice appeared in July 1913; it situated Moorcroft’s pottery at the forefront of contemporary ceramic art, and emphatically so:

These show a marked originality of treatment, more especially as regards the coloration, which is never glaring or obtrusive, but always characterised by refinement and restraint. To single out any special piece for preferment is rather difficult, but in some of the representations of conventionally treated pansies on a white ground, and rich combinations of red pomegranates and purple grapes with green, some of the most beautiful effects which have been produced by modern ceramic art were attained.4

4. The Summer of 1913

The summer months of 1913 saw both the building of the new factory and ever-increasing tensions at the Washington Works. On 24 June, notices of dismissal were issued to Moorcroft’s staff; this was nearly two weeks after the Directors’ meeting of 11 June when it had been decided to issue the notices ‘at once’, but, perhaps not coincidentally, it was a day when Moorcroft was absent from the Works, attending the second Board meeting of his new Company in London.

The retention of Moorcroft’s trained workforce was as essential to the successful transfer as the building of the factory and the maintenance of the business. If they were dismissed before the new works were ready, they could only be kept together if the department moved into a temporary site, or if they were paid to do nothing. This increased the financial pressure on Moorcroft, but it put pressure, too, on his staff. When Moorcroft returned from London, he wrote at once to Sir Corbet Woodall, drawing attention to an announcement on the factory gates which stated that ‘only workpeople who have received formal notices will be affected by the discontinuance of the Florian Department’. This statement implied a choice between Macintyre’s and Moorcroft; to opt for the former was to ensure continued employment at the Washington Works, to opt for the latter was to face certain dismissal, and (it was implied) an uncertain future with an employer whose new factory was still little more than a building site. It is clear that Moorcroft’s staff had already been confronted with this stark choice:

Workmen who have worked many years for the firm in connection with my department have been […] questioned as to their intentions of transferring their service to Moorcroft […]. There is much strong feeling roused in the matter, and this appears to be quite contrary to the idea of ‘transfer’ named in your letter as the word ‘discontinuance’ conveys a false idea, contrary I feel sure to the wish of the Board as a whole, by intimidation of men and women […] without whose services the transfer could not take place.

The letter was sent on 26 June 1913; Woodall replied the next day. He re-affirmed his wish that ‘the transfer of your department should be carried out without friction and with every consideration for your interest’, but he was either unwilling or unable to intervene: ‘I am distressed to have your letter of the 26th but cannot see my way to interfering between the Managing Director and yourself.’

Ironically, the notices were served on the very day the Directors of W. Moorcroft Ltd. approved the wording of a formal announcement of the new Company. The text bore the scars of the past few months; it began factually, tactfully focussing on the business plans of Macintyre’s:

Owing to the development of the Electrical Fitting side of the business of Messrs. James Macintyre & Co. Ltd., of Burslem, and the consequent need for space, they have decided to discontinue the production of the Faience and Decorative Potteries called Florian Ware […].

The finality of ‘discontinue’ was deftly countered in the next sentence, the decision to ‘continue’ Moorcroft’s work being attributed, implicitly, to both parties, strengthening an image of productive collaboration:

He has earned a well-deserved reputation for the quality and artistic merit of his work at Messrs Macintyre, […] and it therefore seemed most desirable that the good work which he has established should be continued.

The impression created was of a seamless and harmonious transition, the contentious issue of timing, still very acute, being adroitly avoided. It was a masterpiece of diplomatic and marketing rhetoric:

Arrangements have accordingly been made, with the cordial good wishes of Messrs. James Macintyre & Co. Ltd., under which this class of pottery will be manufactured by us at Cobridge, Burslem. Mr Moorcroft will act as the Managing Director, and the production will be under his direct control, with the services of the same artists and workpeople who have hitherto been employed under him.

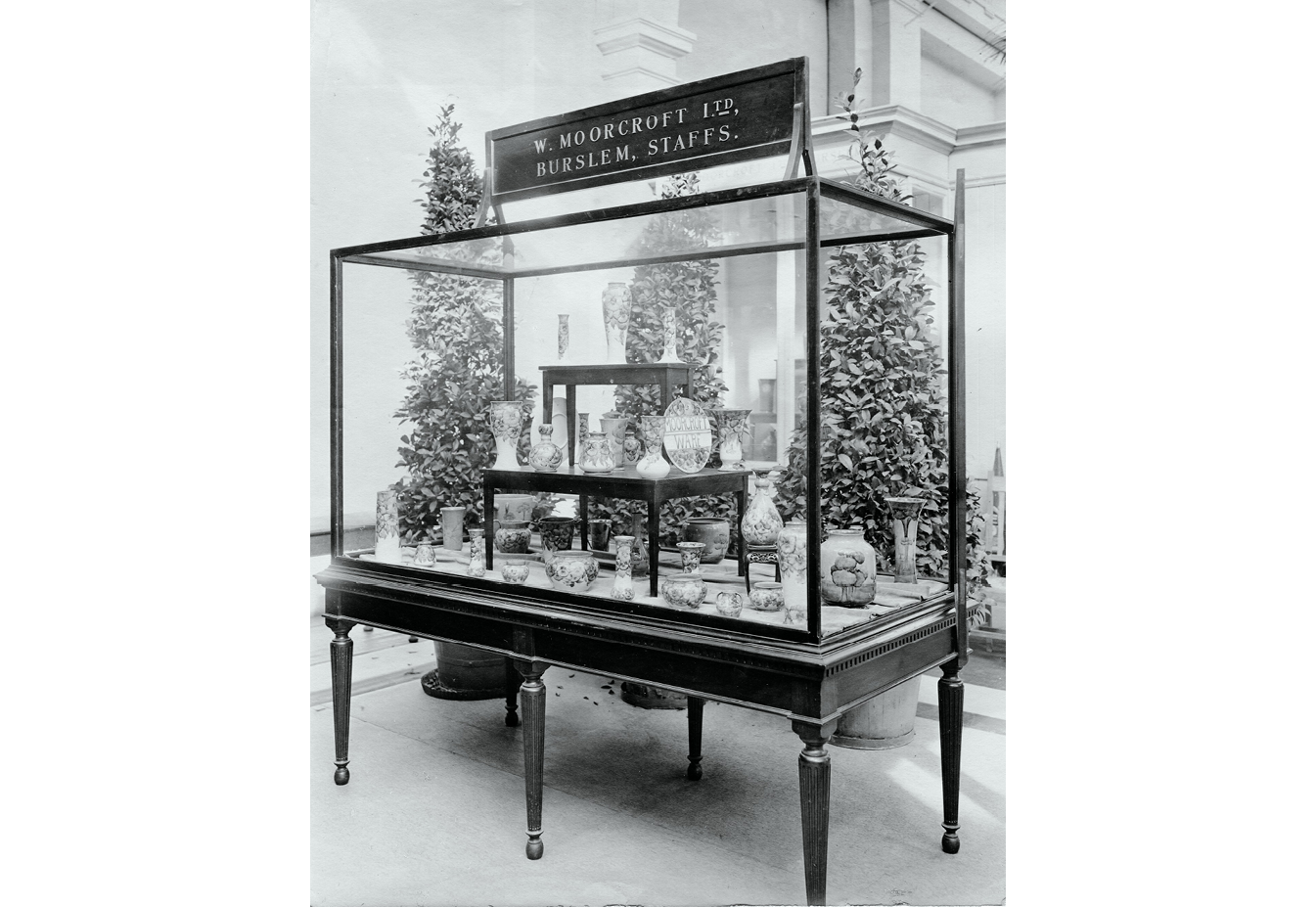

The ambivalent relationship of Macintyre’s and Moorcroft caused other problems at Ghent, where the exhibit of W. Moorcroft Ltd was initially awarded a Gold Medal. On 7 July 1913, T.C Moore, a member of the jury, wrote to explain the background to this award. It had been judged that W. Moorcroft Ltd. was a new firm, quite distinct from J. Macintyre & Co., Ltd.; new firms, by convention, were not considered for the higher awards. Invited to appeal, Moorcroft argued that, for all that the two firms were indeed distinct, the pottery exhibited by Macintyre’s at Brussels and by W. Moorcroft Ltd. at Ghent was created by the same designer and his assistants; the one was, therefore, a seamless continuation of the other. It was ironic that he should have to make this argument against the background of a far from seamless transition, but it was a successful appeal, and on 26 July, his award was increased to the Diplôme d’honneur. Just five days before his departure, it was a fitting end to his career at the Washington Works, an acknowledgement of his defining role in pots officially produced in Macintyre’s name.

Fig. 45 William Moorcroft, Part of his exhibit at Ghent 1913. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

But the month ended neither smoothly nor harmoniously. On the official last day, 31 July 1913, Moorcroft noted simply in his diary: ‘Staff left 6 pm. Watkin looked over department and was again unusually bitter.’ The staff had left, but Moorcroft had not cleared his office, and tensions increased as Watkin instructed the firm’s solicitor to deny him further access to his (now former) place of work. A week later, though, on 7 August, his attention was fixed on the new factory, and he recorded the first significant step towards production; his sixteen years at the Washington Works were over, and a new chapter was beginning:

New works with Mr Lasenby. Thrower made first bowls which were to be signed and described as the first pieces made. Met Newman, Barlow H., Barlow, (Jnr), Greatbatch, Hawley, Plimbley, Tudor, K. Newman, Hassall (Engineer).

5. The Contract with Liberty’s

Blackmore’s letter of 12 February 1913, which first proposed the terms on which Liberty’s would consider an investment in Moorcroft’s yet-to-be-born company, was perhaps the most important document in his career. Although its terms would be radically re-written fifteen years later, this proposal both ensured and enhanced his independence as a potter.

Liberty’s were prepared to invest two thirds of an initial capital sum of £3,000, against Moorcroft’s one third; but there were conditions. All of Moorcroft’s investment was to be in shares, whose value would be determined by the fortunes of the Company; three quarters of Liberty’s money was in the form of debentures, and therefore safeguarded against failure. Added to which, Liberty’s claimed entitlement to a full half share of distributable profits, and a voting power ‘in excess of’ Moorcroft’s. The uneven distribution of risk and benefit was evident, and Blackmore made no secret of it:

We feel bound to point out to you that […] if the Company is not successful, although we might retrieve the whole or portion of our capital secured by the Debenture, the resulting loss would, in the main, fall upon yourself; and also that the fact of our holding a Debenture puts us in the position of a creditor of the concern and consequently in a stronger position than yourself. In effect, you really place yourself unreservedly in our hands.

In addition, Blackmore proposed a fixed time limit of ten years on this investment, clearly setting out two possible outcomes at the end of this period:

We must also have the right at the expiration of ten years to withdraw our capital, or if you are not inclined to pay us out at par, to wind up the concern and realize it to the best advantage.

Survival beyond February 1923 depended, then, on the commercial success of the Company, and Moorcroft’s ability to buy Liberty’s out within ten years. But the next stipulation was perhaps the most significant of all:

You must of necessity enter into an agreement with the new Company to give your services to it for your life, or so long as the Company may require your services.

Liberty’s were not so much co-financing a company as investing in William Moorcroft, and in pottery designed and produced by him; his personal involvement was the indispensable condition of their financial support. Blackmore recognised that such terms, clearly designed to protect Liberty’s capital, could not be accepted lightly. And yet the fact that they were drawn up at all implied a shared belief that the project had commercial potential, and they were prepared to invest the time and resource to make it succeed. It was a lifeline, with strings attached no doubt, but a lifeline nevertheless. Moorcroft’s letter of acceptance was dated that same day, 12 February:

I beg to thank you for your proposals regarding the new works. I am grateful for your interest, and agree entirely with all you suggest. Under the conditions now proposed, I believe a fuller development of the business is assured.

The signing of the Articles of Association took place on 21 April 1913, just nine days before Moorcroft’s wedding, and two days before the royal visit to Stoke. The Agreement documents codified and clarified many of the clauses in Blackmore’s letter. Moorcroft was entering into a relationship with W. Moorcroft Ltd.; the Company bore his name, but it was a separate entity. His appointment as its Managing Director was fixed for ‘a period of 9½ years from 1st July 1913’; authority to renew was in the hands of the Company, as was authority to dismiss. In such circumstances, the issue of voting power was thus potentially crucial. The Memorandum attributed 1,250 A shares to Moorcroft, and 650 B shares to Lasenby; with the enhanced voting power of the B shares, ultimate control rested, therefore, with Liberty’s. Given that Lasenby was Liberty’s Director on the Board, the risk of confrontation was minimal; but the theoretical possibility of being outvoted by the B shareholders was built into the agreement. Such terms may have enshrined Liberty’s effective power to terminate Moorcroft’s appointment, but this is not where the focus of the contract lay. Quite the reverse. The contract created an independent company, but it also underlined the indispensable role of Moorcroft within it. Ownership of his designs was assigned to the Company, and he was required, too, to keep written records of his glaze and other recipes. The clauses sought to protect the Company (and Liberty’s investment) against a future without Moorcroft’s input; but they were based on a clearly flawed belief that the quality and impact of his work could be reduced to, or replicated by, a pattern or a chemical formula.

Such terms put Moorcroft in a different, and better position than he had enjoyed with Macintyre’s. The contract may have been unequal, but it was not one-sided, and Moorcroft stood to benefit greatly, and in many ways, from the association. It gave him access to the legal and commercial expertise of a leading London retailer, but, more significantly, he had the freedom to run his own works, to be himself in ways which had hitherto been impossible. He may have been reliant on Liberty’s financial support, but he had the means, and the incentive, to buy them out. Writing on 14 February 1913 to acknowledge his acceptance of the terms, Blackmore added in a postscript:

What do you think would be the best name for the new Company?:

W. Moorcroft, Limited

Moorcrofts Limited

Moorcroft & Co., Limited

W. Moorcroft & Co., Limited.

The options proposed by Blackmore confirmed Liberty’s focus on William Moorcroft at the heart of the new firm; and in his choice, Moorcroft underlined the same priority, selecting the option which most clearly focussed attention not on the Company, but on the man. This same principle would be reflected, too, in the continuation of his distinctive practice of signing his ware; his name impressed on the base of pots was the trademark of the Company which produced them, but what truly defined them as Moorcroft ware was this manuscript mark of his personal association with each individual piece.

6. Conclusions

A desire to concentrate on the production of electrical porcelain was doubtless one reason why Macintyre’s Directors agreed to close Moorcroft’s department, but it seems certain that this alone was not enough to explain the decision. Nor is the alleged unprofitability of his work, an argument which the Woodalls never wholeheartedly endorsed, and which clearly did not dissuade Liberty’s from investing in its future. Moorcroft’s growing international reputation as a ceramic designer was evidence enough of the success of his ware, and the Woodalls celebrated it. It was quite characteristic of the enlightened industrial view praised by the Pottery Gazette:

Most of the best firms in our industries are proud of the work of their artists, and are always willing to give them credit for their skill.5

And even after the decision had been taken, their encouragement continued; indeed, without the support of the Woodalls for an artist they clearly valued highly, the production of Moorcroft ware would not have continued beyond 1912. The fact that they allowed him to take his staff, and to claim ownership of designs created while their employee, was a gesture of decisive significance; the terms of his contract with Liberty’s were not nearly as permissive in this respect. It is clear, though, that Macintyre’s Managing Director, for his own reasons, was unwilling to facilitate Moorcroft’s success, and he was able to persuade the Woodalls that closure of the department was in the best interests of the Company as a whole. It is possible that, in other circumstances, Moorcroft might have made his career as Art Director with this firm, but it is by no means certain. As he developed his distinctive identity as an artist, he clearly began to envisage the greater opportunities which independence would bring him; the deterioration of working conditions at the Washington Works doubtless merely accelerated a separation which, one way or another, was bound to happen.

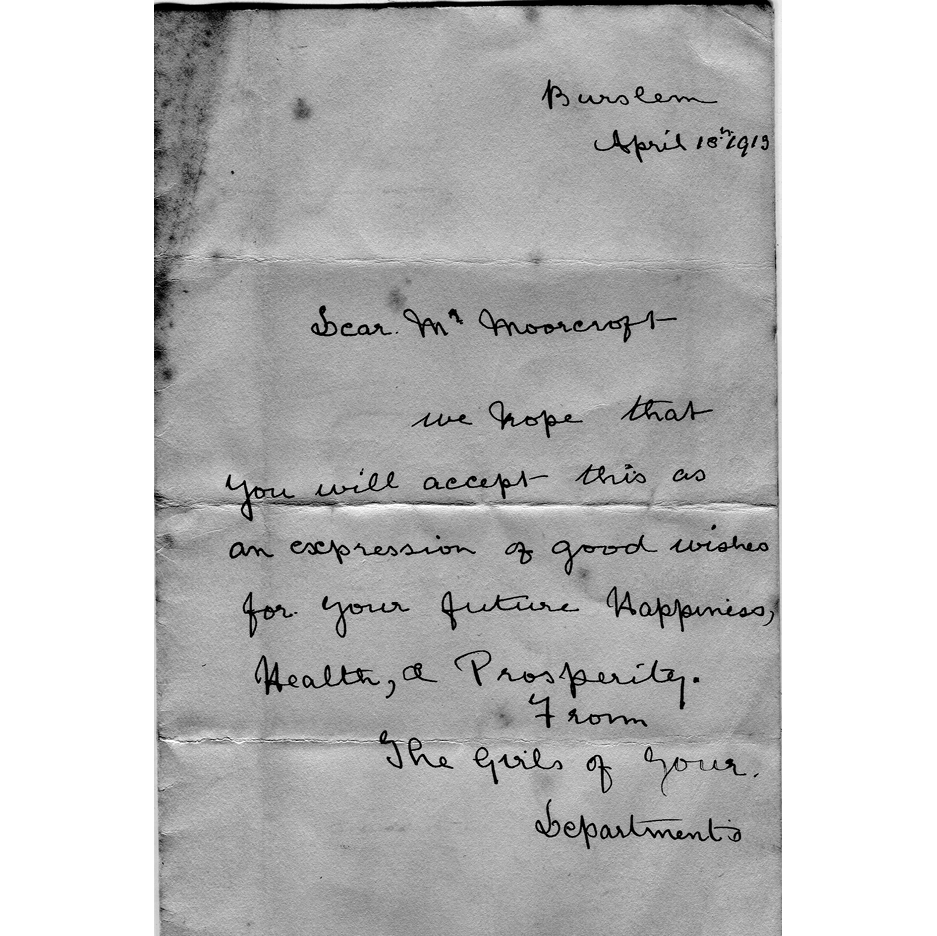

These months would certainly have been far less troubled if he had simply sought work as a designer in another firm, as Woodall, in October 1912, doubtless thought he might. But for Moorcroft, design led naturally and inevitably to production, and from there to the satisfaction of his customers. This was all part of a single creative process which he had been able to direct in his department at the Washington Works, but which was not the standard role of the Art Director in other firms. Only in his own works would he be able to find the same kind of freedom to be himself, and he would do anything to achieve it. And his staff were no less essential to this project. Without his thrower, turner, tube-liners, paintresses or firemen there could be no Moorcroft ware; these were his ‘assistants’ as he tellingly called them in his will, specially trained by him to realise his designs, extensions of his own self to whom he felt absolute loyalty. And the reverse was also true. On the occasion of his wedding to Florence Lovibond, he received a greeting from ‘The Girls of your Departments’ dated 18 April 1913; just over two months away from the closure of the department, and with, as yet, no factory to go to, this was a significant vote of confidence, solidarity and trust:

We hope that you will accept this as an expression of good wishes for your future happiness, health and prosperity.

Fig. 46 Note to Moorcroft, 18 April 1913,‘From the Girls of your Departments’. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

When Moorcroft wrote to Arthur Liberty to congratulate him on his knighthood on 2 January 1913, he pointedly echoed Crane’s affirmation of man’s right to the ‘possession of beauty in things common and familiar’;6 he saw in Liberty’s a commercially successful firm, but one not driven by commercial values alone:

May one offer you one’s congratulations and also express the hope that you will be long spared to continue your wonderful work of making the common things in life beautiful, as well as adding beauty to the rarest.

He used the same phrase with respect to his own enterprise just seven weeks later, when he returned the proof of the ill-fated Pottery Gazette notice on 19 February. His new association with Liberty’s was not just the result of a personal friendship with one of the firm’s Directors, nor was it pure expediency on his part. He saw in their future collaboration a shared ambition: to beautify everyday life:

[…] we shall be indeed grateful for any assistance you can afford us in directing attention to our efforts to produce pottery such as will show that it is possible to make common things beautiful.

But crucially, this ambition was not conceived at the expense of commercial success; quite the reverse. At stake was the retention of Liberty’s support (and perhaps, too, the prospect of buying them out), but also, equally, Moorcroft’s own self-belief. It had been repeatedly asserted by Watkin that his department was unviable, and Moorcroft was determined to prove it had the potential it had been denied. He believed in his ware, and he believed that it would sell, and sell well; beauty and commerce were not incompatible. His proposal for expansion, in his last report to the Macintyre Directors, had already implied this belief, as did an undated draft letter to Watkin, clearly written in this period:

The other day, Waddington of Keighley, was telling me how he first heard of the firm. He was visiting a house in Harrogate and saw two ‘Aurelian’ vases. They attracted his attention and led to his writing to the works for a collection to be sent. Since that time, he informs us he has not missed re-ordering in any year. But more, he paid us this tribute that the goods were so distinct that they had brought the best people in Keighley to his shop, and had helped him to develop a better class business. In my humble opinion, there are hundreds of such people in the country, who are waiting to be shown our productions.

At the end of his letter to Woodall on the 16 November 1912, as he sought more time to make his plans, he gave powerful expression to his vision for the future:

In conclusion may one add that one has long and fondly hoped and yet hopes to establish at Washington Works a production unequalled and one that would make a reputation world-wide. I feel so very deeply a force both within one and without, shaping a future that will find in its fulfilment ones wishes realised.

Now, nine months later, he was in a position he might not have dared imagine then, with his own modern, purpose-built factory, the freedom to create, and access to the commercial network of a leading London retailer. He had ten years to prove himself. And he would.

1 All unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

2 Reginald T. Longden (1879–1941) was a prominent architect in north Staffordshire, and an active member of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England.

3 Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (March 1913), p.277.

4 R. Grundy, ‘Current Art Notes’, The Connoisseur (July 1913), p.206.

5 ‘The Arts and Crafts Exhibitions’, PG (February 1913), 186–87 (p.187).

6 W. Crane, ‘Of the Revival of Design and Handicraft’, Arts and Crafts Essays (London: Rivington, Percival & Co., 1893), 1–21 (p.13).