7. 1914–18: The Art of Survival

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.07

1. Negotiating the Start of War

On 3 August 1914, Moorcroft sent his first end-of-year accounts to Harold Blackmore; on the following day, war was declared on Germany. The surge of volunteers in the early months had an immediate impact on the industry, the Pottery Gazette reporting in November 1914 that a ‘majority’ of firms were working no more than three days a week. Moorcroft’s workforce, however, remained remarkably stable; of the ten men listed in the wage book in July 1914, all were still there in January 1915. Clearly looking forward, he planned the installation of a second oven, and started to develop new monochrome lustres. He wrote in exultant mood to Alwyn Lasenby on 6 December 1914: ‘The results are better than I expected. […] The copper lustre will be greatly improved later, but now it appeals to all who see it.’1 He saw himself at the threshold of a new epoch; in a draft letter to his step-mother of 6 December 1914, he expressed great hope for the future, when daily life would again be beautified by art:

This European upheaval must be a prelude to a Renaissance greater than ever before. We feel this trial is the shaking away of some of our modern evils. What will the new birth be like; shall we find a happier people; will commerce be a more beautiful force? […] The great things in life must be shaped in our common pursuits, and that art must be greatest that is found in every simple thing, in every home.

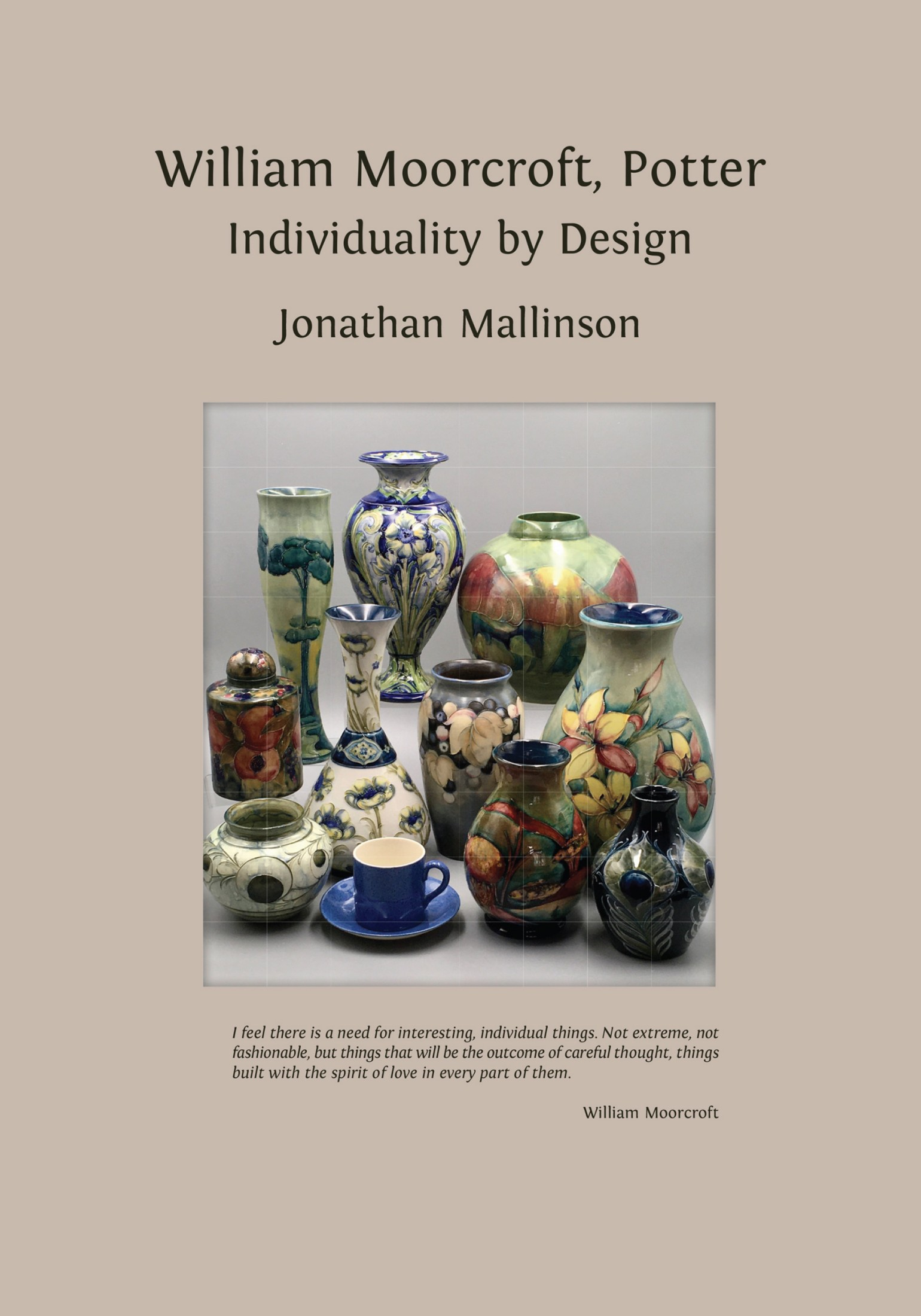

This attitude was reflected, too, in his first major advertisement, used in the course of 1915. It made use of extracts from reviews in the London press, prominently displayed in an inserted box. Significantly, the selection included none from the many favourable reviews he had received in the Pottery Gazette, and focussed on his reputation outside the world of the Potteries. The publications consisted entirely of art journals—The Magazine of Art, The Art Journal, The Studio, The Connoisseur—and London newspapers—The Standard, The New Witness. One extract, from a review in The Standard of his exhibit at the British Pottery and Glass Fair, was explicit about the status and impact of his ware:

A visit to the exhibit is like a sudden transference from the world of commerce to the world of Art. Mr Moorcroft is an artist. Each piece has been carefully sheltered from the potter’s wheel to the furnace, all its changing moods carefully studied, until it comes out in its finished beauty, worthy to carry the signature of Moorcroft. Collectors the world round are already being attracted by Moorcroft ware.2

Fig. 58 Moorcroft’s advertisement in the Pottery Gazette (February 1915), ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Confident about the quality and appeal of his work, Moorcroft continued to promote it. On 5 January 1915, he wrote unsolicited to Thomas Webb & Sons, proposing that they share a travelling representative in the provinces. Webb’s enjoyed an international reputation both for lead crystal and for fine cameo glass; they had a similar target market to Moorcroft’s own, and he wrote to them on equal terms: ‘The pottery we make is entirely hand production and made by the best workmen, each piece being the best possible individual effort. We realise that your glass is the very best.’ On 12 January 1915, they accepted the proposal, offering in addition the use of a small showroom in London; by the end of January, Moorcroft was writing to the most exclusive retailers in any particular town, informing them of the imminent visit of their (now) joint representative. One such was Preston’s of Bolton, the most prestigious jeweller outside London, whose unique, four-storey premises had opened the previous year. Writing on 21 June 1915, they foresaw ‘a very big business together’. Consolidation of the home market was complemented by growth in his export trade. Moorcroft’s business with major Canadian outlets was already strong, and it was thriving. Ryrie Bros, Ltd., an elegant Toronto jewellers, wrote appreciatively on 15 September 1915; Moorcroft’s ware was selling well, and they needed more:

We received your shipment a few weeks ago, and I am very glad to say that it promises to have a ready sale with us, particularly the Red Spanish. I am enclosing a repeat order for a number of lines […].

And on 16 August 1915, he heard from W.D. Barlow, an agent in Florida, who wished to open up new markets in South America:

I really believe that there should be a good future for your goods, especially in the Argentine where they have an educated taste, and they only have to be shown to be sold.

The demand for Moorcroft ware was buoyant, and this, the world over.

Of particular significance, however, in this first year of war, was Moorcroft’s exhibit at the inaugural British Industries Fair (BIF), organised by the Board of Trade. Moorcroft saw the commercial and artistic value of this opportunity, and Liberty’s actively supported him, offering on 14 April 1915 to supply furnishings which would help distinguish his stand. It was the perfect collaboration of artist and promoter, and the effect achieved was the effect sought. The Pottery Gazette placed particular emphasis on Moorcroft as a producer of uniquely distinctive art ware:

It is always a trifle difficult to deal with superlative adjectives, […] but no one will complain of this particular compliment, because they will recognise that in the case of the Moorcroft ware a class of goods was being shown unlike any other ware that the Fair embraced. It is difficult to show off to advantage purely artistic wares except in an artistic setting. This Mr Moorcroft, as an artist, had recognised and provided for.3

Fig. 59 Part of Moorcroft’s exhibit at the 1915 British Industries Fair. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Moorcroft was recognised as an artist, but this did not make his ware any less commercial; quite the reverse. Trade may have been sluggish across the industry as a whole, but Moorcroft’s pottery continued to be noticed, and by significant new clients. A representative for James Shoolbred of the Tottenham Court Road, the celebrated high-end retailer of furniture and accessories for interior design, wrote back to his firm on 21 May 1915, impressed by what he had seen: ‘I made a point of seeing Mr Moorcroft. I think his productions are very artistic.’ And, the most significant sign of his success, the stall was visited by the Queen on the opening day. Moorcroft noted in his diary for 10 May 1915: ‘Moorcroft stand visited by the Queen who explained to the Board of Trade officials and to her friends where the pottery was made.’

The British Industries Fair was a trade fair, but Moorcroft was also making an impression in artistic circles. A letter of 19 June 1915 from the editor of Drawing, An Illustrated Monthly Magazine devoted to Art as a National Asset, enclosed a copy of the June issue, ‘which contains a reference to the excellence of your manufactures’. And the editor of The Connoisseur added this note to a letter of 12 June 1915: ‘I am very glad to see the very beautiful show that Messrs Liberty are giving to your work in Regent St. Last night when passing I thought it was really very fine.’ Liberty’s certainly provided invaluable support throughout this first year of the war. In addition to the promotion of his ware, they brought Moorcroft the benefit of their business experience, checking the credit worthiness of new customers, and offering legal advice in his dealings with contractors. In return, the store enjoyed preferential terms for its orders, and exclusive rights on certain designs. It was a relationship of clear mutual benefit, inspired not simply by a common self-interest, but also, above all, by a shared desire to deal in ware of the highest artistic quality, and to promote it worldwide. Liberty’s supported his presentation at the British Industries Fair; they also supported, morally and financially, the move to expand his factory. At a meeting of Directors on 11 August 1915, a loan, secured by debentures to the value of £1200, was agreed. On 18 September 1915, planning permission for an Oven and Placing Shed was approved; less than four months later, on 5 January 1916, Moorcroft recorded in his diary the first firing of his new Glost oven.

Moorcroft may have prospered in these early months of the war, but the effects of the conflict were nevertheless beginning to make themselves felt. The image of calm creativity projected by his display at the 1915 BIF stood in stark contrast to the growing tensions in the world outside. Within the space of just a few weeks during the summer of 1915, the price of many key materials—fuel, firebricks, colour, clay—was significantly raised, soon to be followed by a 7.5% increase in wages ‘to meet the extra costs of living occasioned by the war’.4 These rises, and others, translated immediately into higher production costs and selling prices. The Pottery Gazette calculated the average increase to be nearly 33%; this was ‘phenomenally high’, but the hope was expressed that retailers would understand its inevitability.5 It was not so in reality. H.G. Stephenson, Manchester, suppliers of catering equipment then at the height of their growth, wrote on 5 August 1915 to query Moorcroft’s invoices: ‘[…] we think there must be an error in the price charged. The general range of prices strikes us as being higher than the impression we got from the quotations given at the Fair.’ And the same was true of Liberty’s, writing on 28 October 1915:

We are in receipt of the consignment of Autumn tint pottery and find that the prices are much higher than before. We do not think this will help the sale of same and therefore ask you to give the matter your attention.

Such pressures had other, more permanent, consequences. Bawo and Dotter, china importers with whom Moorcroft had been doing business for several years, were forced into receivership, and the collaboration with Webb’s, so enthusiastically initiated at the start of the year, had come to nothing by the summer.

In this first year of war, Moorcroft was working in increasingly severe economic conditions, yet determined to maintain the highest quality. And all this in the knowledge that if he failed, his business would not survive. A retrospective article published in the Pottery Gazette traced the brief history of the Linthorpe Pottery, celebrated for its artistic innovation and quality of production, which had closed in 1889 after just ten years. Its fate was succinctly described, a grim reminder of Moorcroft’s precarious position: ‘Linthorpe art pottery was a gallant attempt to found a fresh and original style of pottery. Artistically it was a success, commercially a failure.’6 Developing trade in pottery ‘for every household’, at home and abroad, was just one route to survival in a time of war, and Moorcroft quickly understood that it would not suffice on its own. Equally significant were military contracts; these did not just generate income, they also offered protection against the conscription of male staff. On 6 November 1914, less than two months after the declaration of war, he contacted the Director of Army Contracts, sending a copy of the Connoisseur article on his ware published the previous year. He won orders for inhalers at an early stage; many more would follow.

Fig. 60 William Moorcroft, Inhaler (c.1916), 20cm. Turner’s work card. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

The first year of the war was clearly difficult, and the year-end outcome was awaited with some concern; Lasenby wrote on 16 September 1915: ‘I am (and I know you are) very anxious to learn the result of the past fourteen months trading.’ The results, though, were good. At the second AGM, 6 October 1915, a net profit of nearly £327 was declared.

2. Popularity and Deteriorating Conditions

As the war entered its second year, the cost of labour continued to increase, and so too did its shortage. Without manpower, firms could not function. For Moorcroft, though, the most serious blow to his workforce was not the result of conscription, but the unexpected death in December 1915 of James Newman, his sole thrower. A craftsman of quite exceptional ability, he had worked with Moorcroft from his earliest days at Macintyre’s. Miraculously, Moorcroft managed to secure the services of Fred Hollis, recently retired; without him, the factory would almost certainly have had to close.

Shortage of labour was severely affecting production in the region. In January 1916, the Pottery Gazette appealed to dealers and retailers to show ‘a spirit of benevolent patience’ in view of the ‘stupendous’ problems faced by manufacturers.7 Some of Moorcroft’s customers did so, but many more adopted a different, hectoring, reproachful tone. In a letter of 22 June 1916, F.C. White of Ilfracombe were quite clear about the consequences of a missed deadline, for them and for Moorcroft:

When the order was placed, I specially ordered delivery in May or the latest 1st week in June—this time was fixed to catch the Whitsuntide people. […] As we have now lost these sales, and the coming season promises to be a very bad one, we cannot now accept delivery, only on sale or return. [Emphasis original]

And on 9 September 1916, Jordan Marsh Co., the first department store in the US, wrote in uncompromising terms at the end of an exchange of letters on the subject of a delayed despatch:

If you will refer to our letter, you will find that we asked you for a definite delivery date and informed you that we had to cable a reply to Boston, which we cannot do from your letter of yesterday. Please let us have by return without fail a positive date upon which you promise to make shipment.

The store’s request for a precise and guaranteed date of delivery had evidently been answered by a letter from Moorcroft expressing good intentions, but offering no pledges. The exchange exemplified what was an ever-deepening gulf between past and present, the old normal and the new. Beneath the retailer’s response to what he saw as a manufacturer’s evasiveness was an attempt to find stability in a world which now had none. In the current conditions, where costs were rising, supplies of raw materials were uncertain, and labour was short, one could not foresee the future; one could no longer give one’s word. Unreliability of production was not the sign of a manufacturer’s inefficiency, indifference or loss of moral integrity; it was the consequence of an unsettled, and unsettling, world at war.

In this increasingly turbulent, imperfect world, retailers and their customers clung to a comforting memory of flawless quality, of how things used to be, in their eyes at least; the (at times tetchy) disappointment expressed in letters to Moorcroft reveals just how much such quality was associated with his ware. Some lamented the simplification of his styles which inevitably accompanied more restricted war-time production. Collinge & Co., St Annes-on-Sea, wrote on 5 July 1916 about a consignment of Pomegranate ware, dismayed that it contained no pieces decorated with open fruit, a more time-consuming variant of the design:

We have received the selection of ornaments today, all these appear full pomegranate, one which we received from our Burnley house was much more broken in the design and more green intermixed with the red. […] Please say by return if you have anything similar to our description.

And both retailers and customers clearly found something reassuring about the designer’s personal signature on the base of his pieces; a paper label, introduced at this time, was not quite the same. ‘The Crockery’, Letchworth, writing on 19 October 1916, thought fit to point this out: ‘We prefer your name on the pottery in preference to the label.’ [Emphasis original] Trade in high-end goods may have been slowing down, but Moorcroft’s ware continued to be appreciated.

Fig. 61 Rectangular label introduced c.1915. CC BY-NC

Pressures felt within the industry as a whole were particularly acute in a small enterprise which depended so much on a single man. As Liberty’s well knew, without William Moorcroft there could be no W. Moorcroft, Ltd., and on 16 September 1915, Lasenby wrote (and not for the first time), encouraging him to employ an assistant:

I feel strongly (and I know Mrs Moorcroft is with me) that it is unfair to your health to continue as you are without any change; at the same time I appreciate that in building up a business of so personal a character, the great importance of keeping one’s finger on all the points, and watching the working costs very closely.

Lasenby understood very well the challenges, and the risks, of Moorcroft’s project: to retain the individual quality of a studio pottery while operating on a larger scale, on an international stage. Moorcroft’s vision was difficult to realise at the best of times; by the second year of the war, times were anything but the best.

In early 1916, the situation declined further. The first Military Service Act, passed in March 1916, introduced conscription for unmarried men aged 18 to 41, and exemptions originally granted to the pottery industry were coming under renewed scrutiny. The Home Office and Board of Trade Pamphlet on the substitution of women in industry for enlisted men, dated March 1916, encouraged firms to concentrate their efforts on government contracts, and then on exports. To conform to such priorities, though, was not just a question of patriotism, it was a matter of commercial survival. As pressure mounted to supply the army with men, it was these activities alone which kept the Tribunals at bay. Such was the growing concern in the industry, exhibitors at the 1916 BIF made representations to the President of the Board of Trade. In all these circumstances, the very fact that the Fair took place at all may have seemed anomalous. And yet, significantly, Moorcroft created an impressive display. It is clear from the Fair report in the Pottery Gazette that he was producing ‘a large variety of articles’, from vases and bowls to ink stands, candlesticks, morning sets and dessert sets. But what impressed the reporter above all was not the commercial potential of this functional ware, but its sensitivity, restraint and peacefulness; the tone of his report was markedly different from that given to others:

If there was anything in the whole Fair which appealed definitely to one’s aesthetic nature it must surely have been the stand of this firm, the atmosphere surrounding which was one of quiet, dignified artistry.8

By the summer of 1916, the shortage of men both at the Front and in war service elsewhere was critical, and a second Military Service Act extended conscription to married men aged 18 to 41. Orders were now beginning to falter, and there was a perceptible change in mood. This Act had a major impact not only on pottery manufacturers, but on retailers, too. And as labour became scarcer, firms feared that workers may leave to seek better terms elsewhere; the risk was not just of loss to the army, but of loss also to competitors. It is clear, though, that Moorcroft was regarded highly as an employer, and male employees not eligible for military service remained on his books. On 17 August 1916, he drew up a renewal contract for his foreman, Henry Barlow, the terms of which included, significantly, the guarantee of a specified wage. But the situation continued to deteriorate. Barlow’s renewal contract was drafted on the same date as the ‘Letter to Employers of Labour in No.6 District’ from the Head of Recruiting, chilling in its courteous but uncompromising tone:

[…] as the head of recruiting in this District, it is my duty to emphasise the necessity for providing men for the Army in that steady flow, without which all other efforts are wasted. Recruiting officers and other specially selected gentlemen have received instructions to cause an inspection of the lists of your workpeople […]. I am anxious that this systematic inspection should be carried out in a friendly and sympathetic manner […].

Commercial and military pressures were combining with fearsome force, and coming ever closer to home. The Pottery Gazette recorded the (eventually successful) appeal of William Howson Taylor to be dispensed from military service.9 The two potters had much in common: both ran a small pottery, both played multiple roles crucial to the success of the enterprise. Moorcroft was more fortunate: aged 44 in May 1916, he was (just) three years above the limit for conscription. But he had also been very astute: his production included a wide range of functional items, he had developed a flourishing export trade, and he had secured significant government contracts.

In August 1916, commercial stagnation throughout the industry prompted this gloomy assessment in the Pottery Gazette: ‘The London trade is dead; the provincial trade has fallen off quite perceptibly; and foreign orders, generally speaking, are nothing to crow about’.10 For Moorcroft, though, the picture was quite different. The continued appeal of his pottery in such depressed market conditions was reflected most strikingly in an article on his ware published in the Pottery Gazette; it was seen to offer a ‘permanent delight’ to those ‘fortunate enough to become possessed of specimens of it’, an effect increasingly appreciated in these uncharted, unsettling times.11 But difficult trading conditions had other consequences, too. If retailers had to absorb the effects of delayed deliveries and of rapidly increasing prices, manufacturers had to manage the non-payment of accounts. W.J. Davis of Ilfracombe, writing on 18 July 1916, acknowledged their dire situation which neither reminders from Moorcroft nor their own good will could improve:

I apologise to you in not replying to your repeated applications to settle your account, I have not been able to do so; so little business being done, last season was very quiet, and up to now, this season is no better. Will you please favour me in waiting a little longer to settle the balance of your account? I have enclosed a cheque for £5, and will endeavour to send you more, as soon as possible.

And Moorcroft was not always insistent. George Humphrey, Dumfries, wrote very apologetically on 10 June 1916, acknowledging his patience: ‘I am ashamed at having kept you waiting for this account so long […] Many thanks for your kindly consideration in not pressing for payment.’ But notwithstanding all these difficulties, he still completed a successful financial year. At the third AGM, 25 October 1916, the profit announced had increased to nearly £870, which, together with the balance brought forward from 1914–15 left a healthy surplus of just short of £940. For all Lasenby’s concern in the course of 1916, it was clear that Moorcroft was doing very well indeed.

3. Looking Beyond the Depths

By the start of 1917, conscription was taking its toll, and, to make matters worse, earthenware manufacture was re-designated a ‘non-essential’ occupation. In this context, the 1917 BIF was clearly a defiant, political statement, boldly affirming the ‘essential’ quality of the industry. The Pottery Gazette understood what was at stake:

[…] it needed a great deal of courage on the part of both the authorities and the traders to organise and patronise in these troublous times an exhibition devoted chiefly to ‘non-essential’ industries.12

The Fair was significant too, though, in another way. The Pottery Gazette report drew attention to the emergence of two contrasting styles of stand design, the one open, the other enclosed. Such terms, it was implied, did not simply describe the physical attributes of the stands, but reflected, too, divergent attitudes to business and its future:

Opponents of the open stands alleged that they tended to encourage imitations and the disclosure of business secrets, and also seemed injudiciously to invite retail traffic; while their supporters acclaimed them as being far more effective as advertisements and as an expression of their holders’ contempt for competition and copying. On the whole, however, the closed stands were in the majority.13

If the enclosed style was ‘in the majority’, Moorcroft’s stand was not; he presented as a modern figure, moving away from more traditional Staffordshire instincts, alongside such progressive firms as Carter & Co. and Gray & Co.:

W.Moorcroft, Ltd., Cobridge, Burslem, are fortunate in being manufacturers of a class of ware which is eminently adapted for exhibition purposes. They occupied an open stand in a corner position, and their display was of a most attractive character […].14

This analysis was telling. The open stand was a mark of confidence in the value of one’s wares; it displayed work made to be seen by all, of a quality which could not be imitated. This was Moorcroft’s position, and it was shared by Liberty’s. Lasenby, writing on 5 January 1917, encouraged him to think big, spatially, commercially, and artistically. The display would be Moorcroft’s triumph, but it was clearly a collaborative venture:

Re the show at S.K. 20 ft will be a much better frontage if you can fix up for that. […] I think there is good business to be got there this year, and no doubt you are looking out some of your best samples of each decoration.

Fig. 62 Moorcroft’s stand at the 1917 British Industries Fair. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Another sign of Moorcroft’s enterprise was his display of lamps, anticipating the modern era of domestic electricity, a characteristic blend of functionality and elegance. Their intended effect in a home was enacted in the exhibit; the lamps both illuminated the stand and drew the eye as beautiful objects: ‘The interior was lighted by electric lamps of Moorcroft ware, the light being softly reflected from the lucent glazed surfaces, some of mauve lustre, others pink, and others green, and all fitted with appropriate shades to match.’15 This fusion of the practical and the decorative, so often pointed out in Moorcroft’s ware, was underlined again in this review. But what was noticed particularly was that its distinctive quality of good design and careful production characterised all his work, and not just the most expensive items:

A fine old oak dresser bore a miscellany of useful and ornamental articles in ‘Celadon’ ware. […] We fell in love especially with a biscuit box and a little lidded tea caddy, for, like a true artist, Mr Moorcroft bestows equal care on small articles as on great ones.16

Fig. 63 William Moorcroft, Biscuit box with Pansy design on celadon ground (c.1915), 15cm. CC BY-NC

To read the report, one might not realise that a war was on, and that the resources of factories, Moorcroft’s included, were beyond full stretch. The quality of his work was the focus of attention, and he was presented as ‘one of the great hierarchy of artist potters’. For his royal visitors, though, the pressures on the manufacturer were as keenly appreciated as the achievements of the artist. In a diary entry for 6 March 1917, he noted visits by the King and Queen, and by the Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum [V&A]:

His Majesty King George called and inspected exhibit, followed later by Her Majesty the Queen and Princess Mary, in company of Sir Cecil Harcourt Smith. His Majesty enquired regarding men employed, and expressed approval of exhibit.

Indeed, by 1917, shortage of staff was so widespread, it had become normality. Edith Harcourt-Smith, wife of Sir Cecil, wrote understandingly on 1 May [1917]: ‘Please do not worry about the porridge bowls etc—they can come when it is convenient to you, for I know you are short-handed.’ But this was quite an understatement. Not only was shortage of skilled labour decreasing production, but the pressure of conscription created an inordinate amount of additional work for Moorcroft, such as the gathering of statistics, completing forms, attending Tribunals. Much time was spent in 1917 seeking to retain his small, but essential, skilled male staff. In a completed form DR17, which included a ‘Statement of all male employees of 16 years of age or over’, he listed just thirteen men, of whom seven were under the age of forty-one, subject therefore to conscription unless he could make a case. To lose these would have been to lose his dipper, slipmaker, handler, jollier, fireman, mould maker, two of his three turners and all of his three placers.

Fig. 64 Completed form, Defence of the Realm Regulation 41A, listing Moorcroft’s male workforce in 1917. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

In the summer of 1917, the case of Tom Foulkes, one of his turners, was being assessed. It was reported in the Pottery Gazette, revealing the effort and ingenuity Moorcroft had to display to argue his case. He clearly negotiated an arrangement whereby ‘one man was enabled to perform work which customarily calls forth the services of three men’, a position strengthened by the fact that ‘the man for whom exemption was claimed was engaged on War Office contracts’.17 Moorcroft’s argument prevailed, and Foulkes featured in wages ledgers until the end of the war. But there were other battles to fight with respect to Fred Ashley and Jack Hill, his only handler and dipper respectively, who had been given exemption, only for this to be revoked. On 17 September 1917, he wrote to the Clerk to the Local Tribunal on the subject of Hill, applying for a re-hearing of the case; four days later, his exemption was increased to three months. Such cases were by no means unique in the industry, and required tireless commitment; Moorcroft’s engagement was such that he successfully retained every eligible man on his staff.

In January 1918, the Pottery Gazette looked back at the pressures under which the industry had ‘suffered grievously’ in the past year, itemising ‘shortage of raw materials, scarcity of labour […], difficulties of delivery, heavy expenses, reduction of revenue, and official interference’.18 Moorcroft had survived the year, however, with a flourishing export trade, and astute applications for military contracts. On 17 May 1917, he noted in his diary an order for 6,000 inhalers, and on 7 June, the War Office (Contracts Department) accepted tenders for numerous other items: 1,000 broth basins with cover and stand; 1,700 5-pint beer jugs; 4,000 milk jugs; 500 3-pint jugs; 800 1½-pint jugs; 800 1-pint jugs; 4,000 inkwells, all to be delivered within twenty-eight days. Such contracts brought him little profit, but they enabled him to keep his factory working, and to take advantage of his overseas orders. At the end of 1916–17 he recorded a profit of just over £858, a sum almost identical to that of the previous year. Once again 5% interest could be paid on the debentures, and a 5% dividend on the share capital.

4. The End of the Tunnel

In the last year of the war, conditions got worse before they got better. Under the terms of the Military Service Act 1918, exemptions held on occupational grounds were withdrawn, and this applied to ‘every man born in or after the year 1875’. This was followed, almost inevitably, by further wage increases; with such a shortage of labour, the workers were in a very strong position. For all this, though, Moorcroft continued to develop his art and his image, devoting much time and effort to the British Industries Fair. The Pottery Gazette notice on his 1918 exhibit was a publicity triumph. His lustre ware was a particular success, their plays of colour stretching the reporter’s command of language:

To mention the several shades of red, bronze, blue, green, mauve and yellow is utterly futile in regard to conveying any idea of the entrancing interchange of light and colour through a myriad elusive tints—colour glowing with light and light breaking up into colour perpetually, so that the eye is never weary of gazing, but continually finds fresh beauties in each successive masterpiece.19

Pansy and orchid motifs were on display; but it was not just the design which was noticed, it was the ‘depth of tone, the delicacy of shading and the velvety texture of the surface’.20 These were pieces which commanded attention, to be looked at and to be held. The exceptional impact of this exhibit was reflected too in the fact that the review, which occupied seventy-two lines, was nearly twice as long as any other in the report as a whole: forty lines were given to Gray & Co., thirty-seven to Wedgwood, and just nineteen to Doulton. And this was all the more striking, given that art ware was selling less well than it once did, a result, in the words of the Pottery Gazette reporter, of the ‘changed social conditions of the present time, the more cultured classes being poorer’.21 For Moorcroft, though, artistic acclaim was matched by commercial success; on 22 March 1918 he noted in his diary a total sales figure of £5,000, a value more than twice that of 1917 (£2,000), and greater than that of the preceding three Fairs combined.

In the final months of 1918, the pressures of war did not abate. On 25 July 1918, following further revision of the Military Service Act, Moorcroft had to apply for exemption himself. On 29 July 1918, Ivor Stewart-Liberty, who had succeeded Arthur Liberty as Managing Director on the latter’s death in 1917, wrote to him, seeking ‘assurance that there is no danger of your being called up, and that you are protected!’ And he continued to take on army contracts, confirming a tender for inhalers on 1 May 1918, and on 17 June 1918 for 1,700 sugar bowls. In a letter of 10 September 1918, Lasenby looked forward to the return of peace, when ‘we can settle down to work and produce things to cause pleasure in our homes, instead of what has been done these four years’. But this was wishful thinking. As the world entered the final months of war, conditions seemed destined to become bleaker, not better; there would be no miraculous return to the world of 1914. The shortage of labour had brought high wages and full employment, creating unique (and unsustainable) conditions of economic prosperity. Looking forward in January 1918, the Pottery Gazette outlined very clearly the difficulties which would face countries ‘under a crushing load of debt’; trade would struggle, and decorative ware would be one of the most vulnerable commodities:

The spending power of the nation will shrink most seriously […]. Those branches of our trade that supply necessary articles—dinner, toilet, breakfast and tea ware—will continue, and the cheapest will be most in demand. They are indispensable, but what of the demand for high-class useful ware? Will it be strong and flourishing? I doubt it; and still more do I doubt whether there will be any market for highly decorated goods. Will not a reign, and a long one, of severe simplicity set in, and economy of the most trenchant character prevail?22

For Moorcroft, particularly, this outlook was bleak, touching both his business and his aesthetic values. If there had been prosperity during the war, this had been enjoyed on borrowed time. And the editorial clearly foresaw problems of unemployment, and growing social unrest. Moorcroft’s ware would have to appeal to a shrinking market, or else he would be finished.

But despite all the turmoil, commercial and aesthetic, Moorcroft continued to look ahead. In June 1918, he applied to register his name as a trademark, and just ten days after the Armistice, on the 21 November 1918, the Industrial Property Department of the Board of Trade gave notice that the application had been successful. He was thinking, too, about the terms of his association with Liberty’s. In 1918, exactly halfway through his agreed ten-year contract, a period dominated by the constraints of war on his plans for development, he was keen to ensure that this relationship did not, inadvertently, hold him back. A draft letter dated 18 August 1918 suggested changes to two clauses in the Agreement between him and W. Moorcroft Ltd.: specifically, the clause which committed Moorcroft to serve the Company ‘so long as he shall live’, and the clause which conferred ownership of the trademark to the Company, for all that this may consist of Moorcroft’s name or signature. Moorcroft’s proposal was to eliminate the first, and to limit the validity of the second to the period of his personal involvement in the Company. For all his commercial success, he was as keen as ever to retain what, for him, defined his enterprise as a potter: his own individuality and autonomy. For Moorcroft, the trademark Moorcroft designated a person above all, not a firm or a brand, and he wished to protect his association, practical, metaphorical, vital, with what was produced in his name. This was more than an issue of intellectual property, it was about the right to his own identity. Ironically, Liberty’s understood that need better than anybody: it was William Moorcroft who made W. Moorcroft Ltd. what it was.

At the AGM of 26 November 1918, a small loss on the year of just over £53 was reported. The Minutes recorded no discussion, but there were clearly no distributions of dividend. Challenging times lay ahead, but Moorcroft was ready. On 12 November 1918, he noted in his diary the need to recruit new staff, and recorded a fresh communication from an agent in Canada; the future was beckoning: ‘Advertise for Turners and Placer. Mr Prentice called.’

5. A Changing World

The military struggle with Germany ended in victory; a commercial struggle, which predated the war, engendered tensions within Britain which would continue long after the Armistice. As war raged in 1915, a number of prominent retailers, craftsmen and designers wrote to Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Permanent Secretary at the Board of Trade, urging him to organise an ‘Exhibition of German and Austrian articles typifying successful design’. Their letter drew attention to the ‘remarkable expansion of German trade, achieved largely at the expense of our own’, and attributed its success to ‘the intelligent cooperation of artists, educationists and manufacturers (assisted by such organizations as the Deutscher Werkbund)’.23 The exhibition was held in March 1915 at the Goldsmith’s Hall, and was warmly received by The Times; its review ended with a stark warning:

If the artist and the tradesman both wish to do as well as they can do, they will come together; if the artist wishes only to be artistic and the tradesman only to be commercial, they will remain apart.24

In May that year, the Design and Industries Association [DIA] was formed, its goal to improve the quality of industrially manufactured goods. Its founding members recognised that the Germans had understood more quickly than the British the applicability of Arts and Crafts principles in the modern industrial age. An article in The Times presented the DIA as ‘A New Body with New Aims’; craft was seen to be the basis of good industrial design, which in turn was the basis of commercial success:

[…] modern industrial methods and the great possibilities inherent in the machine demand the best artistic no less than the best mechanical and scientific abilities. Hitherto our mistake in all the arts of design has been to suppose that there is some incompatibility or inevitable conflict between artistic and mechanical or scientific or commercial abilities […].25

The improvement of quality would derive from the close collaboration of the designer and manufacturer, ‘makers’ working with shared aims and values, and not merely following the whims of the public:

[…] if things are to be well made and well designed, they must be made and designed according to the taste of the maker, who because he is a maker, knows what is good. And he must trust in his taste and in his effort to do as well as he can to sell his products. But this confidence of the makers in themselves can only be produced by cooperation between them.26

This spirit of collaboration extended, too, to the retailer. It was implicit in the proposal that quality of design and manufacture would always sell; an enlightened retailer would help create an enlightened public, as The Times report acknowledged:

What they need to guide them is a determined and organised effort to sell them articles well-made and well designed; and this effort can only be made by the cooperation of everyone concerned in making and distributing. That cooperation is the aim of the Design and Industries Association.27

The Association found limited support among pottery manufacturers, who remained committed to the production of decorated wares popular with a public broadly conservative in its tastes, and it was viewed with suspicion by the Art Workers’ Guild, who viewed craft as an end in itself, and not as the starting point of design for industrial production. These tensions came to the fore at the Eleventh Exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1916, which included a display of household pottery submitted by the DIA; looking back in 1936, the designer Noel Carrington described the impact of an exhibit where ‘fitness for purpose’ was the overriding criterion of selection:

The ware it chose was all stock in trade, chosen for purity of line, utility and simplicity rather than for virtuosity or decoration. The exhibit caused a stir because it seemed so unusual. In the Potteries it caused a row. They did not like to see their Cinderellas chosen for honour.28

The opposition was one of principle, but it also implied a regional tension. Staffordshire potters were not inclined to have their work judged by an external London body.

No less significant was a joint initiative of the Boards of Trade and Education to create an Institute of Modern Industrial Art. Hubert Llewellyn Smith and Cecil Harcourt Smith (Director of the V&A) recognised the commercial and aesthetic importance of improving industrial design, and the educational value of promoting its best examples. Harcourt Smith was keen to include select pieces in the V&A’s holdings, an approach very much in the spirit of the original Museum of Manufactures, established after the Great Exhibition to achieve, in the terms of its first Director, Henry Cole, ‘the betterment of the public’s taste’. In his ‘Proposals for a Museum and Institute of Modern Industrial Art’ dated 29 April 1914, he argued against the distinction between fine and industrial art:

The very terminology of today which discriminates between ‘Fine Art’ (as embracing Painting, Sculpture and, possibly, Architecture) and ‘Decorative’ or ‘Industrial’ art, is an unfortunate misnomer of purely modern origin.29

And he sought to establish links with leading manufacturers, hosting the British Industries Fairs of 1916 and 1917.

Moorcroft embodied many of the principles underlying these initiatives. For him, good design was born of practical experience of making, not always the case with industrial designers; and he represented, like few others, a perfect collaboration of artist and manufacturer (as the New Witness of 1913 had observed), free to produce precisely those wares which he, as designer, wished to do. Added to which, his association with Liberty’s already enacted the enlightened collaboration of manufacturer and retailer which the DIA and the Werkbund were trying to promote. Unlike the generality of Staffordshire potters, seen as being too driven by commercial considerations to pay attention to design, William Moorcroft was recognised as being different, one whose sense of design combined with an experience of manufacture, an artist as well as a maker. His growing association with Cecil Harcourt Smith, whom he first met at the 1916 BIF, brought his work to the attention of leading figures at the Board of Trade. And his work attracted, too, the attention of Ambrose Heal, one of the most forward-looking designer/retailers of the age and a founding member of the DIA, who wrote to him on 16 June 1916, less than four months before the exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society at which the DIA was to have its first display:

We called at your old London address on Tuesday, hoping to see a selection of your pottery. We were sorry to find that you at present have no London agent. We are anxious to see examples of your wares, can you help us in the matter?

And yet, for all the apparent conjunction of Moorcroft’s practice and the underlying principles of the DIA, his conception of design and manufacture was in other respects fundamentally different. For him, quality was a matter of craft as well as art, of individuality as well as design. Significantly, he applied on 14 September 1916, but too late, to exhibit in his own name at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. There is no record of the wares selected for the DIA’s exhibit,30 but if Moorcroft’s work was included in it, he was evidently keen to display, too, decorated wares which he, if not they, had selected. The following year, the Pottery Gazette re-printed a letter from Moorcroft to The Times Imperial and Foreign Trade Supplement of September, in response to a letter published the previous month which had commented favourably on industrial design in Europe:

SCIENCE AND ART IN MODERN POTTERY

[…] It is completely surprising that your correspondent should venture to write so much regarding German and Austrian production at the present time—when many would prefer to forget both it and its baneful influence. May the writer state that he inspected the exhibits of German and Austrian work referred to, and he failed to see anything but what has been—and is—in the judgement of many experts—surpassed by British potters? Such exhibits of German and Austrian work show to us mainly what to avoid, and are so far only good.31

To see German and Austrian design as examples of ‘what to avoid’ implied a wry allusion to Henry Cole’s notorious (and short-lived) ‘Chamber of Horrors’, a gallery in the newly opened Museum of Manufactures of 1852 which exhibited ‘Examples of False Principles in Decoration’ among British manufacturers. Moorcroft was now affirming that the best of British pottery was of superior quality to modern European wares, which he consigned to a similar Chamber. But in doing so, he was not suggesting unconditional support for modern British industrial production. Far from it. What he promoted was individuality rather than slavish imitation, whether of European styles or of indigenous ones. This same spirit inspired his commitment to craft, and his implied objection to the principle of standardisation inherent in an industrialised mode of production. And it fuelled above all his resistance to any external imposition of values in matters of taste or design; William Moorcroft would not be dictated to.

It was individuality which characterised Moorcroft’s wartime designs. Revisiting many of his earlier motifs, he gave expression to the spirit of a war-torn age, suggesting its complex mix of nostalgia, grief, reverence, even hope. A series of designs referred to as ‘New Florian’ looked back to an era rapidly and irreversibly receding. Motifs of pansy, wisteria, cornflower or pomegranate, presented in ‘luxurious’ tones at the dawn of a new Georgian age, were shrouded in more subdued colouring. Peacock or landscape decorations were given the most sombre of treatments, emerging eerily from the darkest of grounds. And the orchid, presented in shades of purple against a dark green ground, embodied a discreet expression of mourning.

Among such designs, his treatment of the poppy was particularly notable. One of his earliest floral motifs, it was revived in ochre, accompanied by dark forget-me-nots set against an inky background; launched at a time when McCrae’s poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ had put the poppy in everybody’s mind, the design could not have been more poignant.

Moorcroft’s solemn tones attracted the critical attention of Alwyn Lasenby in a letter of 17 August 1916: ‘I do not care so much for the very dark ground you have on the last delivery of Pomegranate ware, and much prefer our usual colouring.’ But Moorcroft, taking up the subject on 1 December 1916, noted its significance and its appeal:

We have been supplying large quantities of this design in many countries and we have found the dark ground appreciated and requested. Personally I like the lighter ground, but the dark ground also appeals to one.

One may see commercial astuteness here, but also, above all, sensitivity; such designs embodied that quality of ‘dignified artistry’ picked out by the Pottery Gazette in 1916. And it clearly struck a chord at a time when so much English design was seen to be imitative or superficial, lacking character or meaning, ‘doomed to weakness and failure’ in the words of the Pottery Gazette.32 Moorcroft’s designs were themselves the subject of imitation,33 but he remained himself. Writing on the 16 March 1918, Frederick Rhead urged him to join the newly formed National Society of Ceramic Designers, which stood against European models of design:

Men like yourself, for example, ought to be represented, not only on the local education boards, but on the advisory committees of the Boards of Trade and Education. We want the men who have achieved something, and not the men who talk (more or less intelligently) about it.

But Moorcroft declined; admired by different sides, he maintained an independent position.

|

|

(L) Fig. 65 William Moorcroft, Designs in distinctive wartime colours: (clockwise) Spanish (c.1916), 18cm; Orchid (c.1917), 22.5cm; Landscape (1916), 17.5cm; Cornflower (1915), 8cm; Peacock (1917), 13cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 66 William Moorcroft, Ochre Poppy with Forget-me-nots (c.1917), 12cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 67 William Moorcroft, Pre-war and wartime Pomegranate: (left) dated 1914, 12.8cm; (right) c.1917, 12.5cm. CC BY-NC

What was praised in his work was the fact that it represented the individuality of craft in a world whose trend towards standardisation was viewed by many with suspicion. This quality was singled out by the Pottery Gazette:

In its production everything in the nature of mechanical manipulation is rigidly eschewed, […] whilst every separate process is so dovetailed, as it were, into the next that the whole production when complete is a composite admixture of wonderful texture, without any lines of demarcation, the colour, the glaze and the clay being so fused together as to be thoroughly homogeneous and indestructible.34

The analysis implicitly distinguished this work from industrial production, not just by underlining its manufacture on the wheel, but by stressing its unity of conception and realisation; each piece was seen to issue not from a series of disparate processes on a production line, but from a unified creative act. And what was true of his manufacturing methods was true, too, of his design principles; his work was characterised by its integrity of form and decoration:

The main feature that strikes one in inspecting a piece of ‘Moorcroft Ware’ is that in no case does the decoration create the impression that it has been merely applied, but that, on the other hand, it is an integral part of the piece itself, a stage in the creation of the piece instead of a mere afterthought.35

And it was this quality which made him a ‘pottery artist’, and not, it was implied, an industrial designer.36

And yet, for all that, his was not ware destined for connoisseurs alone. On the contrary. The review stressed its suitability for normal commercial distribution, affirming that any china dealer without ‘a collection of ‘Moorcroft Ware’ in his complement’ would have a stock ‘lacking in completeness’. To the extent that it was subject to serial production and distribution through retail outlets, it was the work of a manufacturer, not of a small-scale potter; but it had that quality of individuality lacking in the products of mass production. His was not a streamlined, mechanised model of production, it was one characterised by its diversity, but unified by the personal mark of its originator:

Wm Moorcroft Ltd., are now making quite a large variety of articles, some of them strictly ornamental, others both useful as well as decorative, but in every case the embodiment of refinement, and every piece, it should be remembered, certified by the signature of Mr Wm Moorcroft himself.37

The Pottery Gazette saw in such wares that integrity of both conception and manufacture which the DIA had identified as an essential element in modern industrial design. It was pottery not made simply as a commercial commodity, and yet whose quality could not fail to appeal. The Times report on the launch of the DIA identified this telling order of priorities in Germany: ‘In German industrial art there has been an immense effort to do the best possible, not merely an effort to capture trade; and that is why they have captured trade.’38 The same outcome was foreseen by the Pottery Gazette of Moorcroft’s work:

Our illustration shows a choice selection of modern ‘Moorcroft Ware’ which we feel sure will be bound to arrest the sympathetic attention of every china dealer who is not too much engrossed in pottery dealing as a matter of mere pounds, shillings and pence to be oblivious of the aesthetic virtues to be discovered in potting as a handicraft.39

It was a prediction clearly validated in his balance sheets.

6. Conclusions

Many firms struggled during these years of war: Wedgwood worked short-time for much of the period, Pilkington substantially reduced their production of decorative ware, and Howson Taylor came close to closure as a result of staff conscription. One might have supposed that Moorcroft’s enterprise would have been particularly vulnerable to the pressures and restrictions of wartime: a small and highly skilled workforce, a costly decorative product, and limited administrative support. The costs of war were certainly reflected in his accounts. His total outgoings practically doubled over these four years, his wages bill rising by 72%, even though the number of employees remained remarkably constant, and his expenses and running costs increasing by 176%. But sales income showed an increase of 119% over the same period, and net profits were recorded in all but the last year of war. That this was so is undoubtedly due to the gritty determination of Moorcroft and his workforce, but also to the high quality and commercial appeal of his ware.

The end of the war did not mark a return to the world of 1914. Symbolically, these years witnessed the death of several figures closely associated with a rapidly receding past: in 1915, Walter Crane, one of the foremost designers and theorists of the Arts and Crafts movement, and in 1917, William de Morgan, one of the movement’s leading ceramic artists. The obituary of Thomas Allen, Art Director at Wedgwood for more than twenty years, distinguished his work from ‘the mainly technically produced decorations of the present keen, competitive age’, and noted with some regret: ‘The times have, indeed, changed’.40 In some ways, Moorcroft may have seemed to belong to this past age, not least in his commitment to thrown ware which he maintained even after the death of Newman in 1915. Casting was associated with modern industry, a matter of commercial priorities, allowing for inexpensive and exact reproduction; it implied that design, rather than realisation, was the ultimate measure of artistic quality. Throwing, conversely, was seen to represent a much more individual, expressive mode of creation. The Pottery Gazette explicitly linked the demise of the thrower to the disappearance of a national style of potting and lamented what was close to being a lost world:

[…] it may be that a national style of pottery will evolve. It may be, we say, but it is doubtful, as the great security for a true and national style of potting has disappeared. The ‘thrower’ is no more. His place has been taken by plaster and iron machines, which turn out his work at a quarter of the price, but without his individuality and sense of line.41

But Moorcroft’s commitment to craft was not born of nostalgia. As the Arts and Crafts movement inspired, paradoxically, two opposite ambitions, the reform of industrial design, and the preservation of craft as an end in itself, Moorcroft sought a different pathway for craft in the modern world: to create handmade objects which might be enjoyed by more than a handful of connoisseurs, to bridge the widening rift between studio and factory. It was a unique position, coherent but unclassifiable. For the Pottery Gazette, Moorcroft’s exhibit at the 1918 BIF epitomised the fusion of art and industry:

[…] the whole of Mr Moorcroft’s work is of the greatest use in keeping alive in this country the spirit of industrial art, the extinction of which would be one of the most disastrous losses war could inflict.42

But this was ‘industrial art’ of a very particular kind, quite different from the model of standardised production emerging in Europe. And it was characterised, significantly, by its ‘vitality’, a quality already identified by Bernard Rackham in the pre-industrial pottery of England,43 and whose broad appeal sprang from the individuality of its manufacture: ‘no more convincing example of the vitality and vigour of the craft of the artist potter in this country could be imagined.’44 Moorcroft’s ware was clearly appreciated, but his project was not without risk in a world of increasing competitiveness. The forming of the DIA implied at one level the recognition that the (true) manufacturer could not hope to compete with industry, for want of capital, size or business expertise; Moorcroft was setting out to disprove this, and to carve out a viable place for craft in a modern industrial world.

The end of the war did not bring quite the Renaissance for which Moorcroft had hoped in 1914, nor did it bring a more beauteous form of commerce. Major challenges faced potters in the new post-war world: rising prices, deteriorating economic conditions, different, evolving models of factory relations, increasing pressure for change in production practices, changing attitudes to design style. But for all these pressures, Moorcroft remained committed to the underlying principle of that optimistic statement of 1914: ‘that art must be greatest that is found in every simple thing, in every home.’ He still maintained his ambition to create works of beauty which were both functional and decorative, and which would find a place in the home as well as the museum. Like the modern design reformers, he believed that art and industry could be reconciled, but he sought to do so through individual craft, not industrial design. A factory which in 1913 had epitomised the new world of safe and responsible pottery manufacture embodied, in 1918, a different statement: an act of faith in the unique quality of individualised, handmade ware, it was an act of defiance even.

1 All unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

2 Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (February 1915), p.158.

3 PG (June 1915), p.658.

4 PG (July 1915), p.782.

5 Ibid., p.780.

6 ‘Linthorpe Art Pottery’, PG (August 1915), 849–53 (p.853).

7 ‘Notes from the Potteries’, PG (January 1916), 78–80 (p.79).

8 PG (April 1916), p.390.

9 ‘Recruiting Tribunal Appeals’, PG (April 1916), 406–09 (p.409).

10 PG (August 1916), p.856.

11 PG (July 1916), p.720.

12 PG (April 1917), p.359.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid., p.370.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 PG (July 1917), p.698.

18 PG (January 1918), p.31.

19 PG (April 1918), 309–10 (p.310). This report stood in stark contrast to that devoted to the lustres of Birks and Rawlins, for which a standard vocabulary of colour was quite adequate: ‘On one side […] was some pierced ware, delicately coloured in turquoise, cream and gold, really a quite recherché line; and on the other were a few exquisite lustre vases, yellow, green and mottled’ (Ibid.).

20 Ibid.

21 PG (April 1918), p.303.

22 ‘Oversea Trade after the War’, PG (January 1918), 57–58 (p.57).

23 ‘Education and Industry’, The Times (22 February 1915), p.5.

24 ‘Industrial Art of Germany’, The Times (3 April 1915), p.3.

25 ‘Art and Trade’, The Times (17 May 1915), p.11.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 N. Carrington, ’21 Years of DIA’, Trend in Design (Spring 1936), 39–42 (p.39).

29 Quoted in M.T. Saler, The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground (Oxford: OUP, 1999), p.70.

30 The Catalogue of the Eleventh Exhibition 1916 of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society simply notes: ‘The aim of the Design and Industries Association is to improve the quality and fitness of goods on sale to the general public through the usual channels. The articles in this section are not on sale in the Exhibition. The maker’s name is affixed to each, and these goods should be asked for under the maker’s name at the ordinary shops.’ (p.105).

31 ‘A Timely Rebuke’, PG (November 1917), 1053.

32 ‘Some Thoughts on Pottery Designs’, PG (April 1918), 317–18 (p.317).

33 Some of Charlotte Rhead’s designs for Wood & Sons clearly took inspiration from Moorcroft’s wares: the pomegranate and dark ground of Arras (1917), or the large ochre poppies of Seed Poppy (1919). And similarly sombre tones were sought from 1917 in the Morris Ware of George Cartlidge, Art Director of Sampson Hancock & Sons.

34 PG (July 1916), 720–721 (p.720).

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 ‘Art and Trade’, The Times (17 May 1915), p.11.

39 PG (July 1916), pp.720–21.

40 PG (November 1915), p.1211.

41 ‘Some Thoughts on Pottery Designs’, PG (April 1918), 317–318 (p.317).

42 PG (April 1918), 309–310 (p.310).

43 ‘The exhibition reveals in the ceramic craftsmen of our country a vitality and inventiveness, in design and technique alike […]’, ‘Early English Earthenware and Stoneware at the Burlington Fine Arts Club’, The Burlington Magazine (February 1914), 265–79 (p.265) [quoted in J.F. Stair, ‘Critical Writing on English Studio Pottery 1910–1940’, unpublished PhD thesis, Royal College of Art, 2002 (p.144).

44 PG (April 1918), 309–310 (p.309).