Conclusion: Individuality by Design

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.15

1. Manufacturer and Artist

It is a telling sign of William Moorcroft’s individuality that he was compared at different times with both Josiah Wedgwood and William Morris, figures who for many represented irreconcilable extremes of factory and studio production, commerce and art. Wedgwood was seen, in the interwar years particularly, as the ideal industrial designer, one whose work combined ‘fitness for purpose’ with ‘undeniable beauty of line’.1 Nikolaus Pevsner saw in Powder Blue the same qualities, and Charles Marriott singled out in Moorcroft’s designs a ‘symmetry and purity of form’ he associated with the ‘original Wedgwood’, explicitly distinguished from the spontaneous vitality of medieval or modern studio pottery.2 Such ware was seen to exemplify the best industrial art, good design made available in larger than studio quantities; the achievement of one Potter to HM the Queen was recognised in another.

Such comparisons paid tribute to Moorcroft’s skill as a designer, and to the popular success of his functional wares; they implied, too, a perception of him as a manufacturer. For all that his scale of operation was much smaller than that of Wedgwood, or of most of Moorcroft’s contemporaries in the Potteries, he did practise a division of labour which for many, from Leach to Gropius, was the defining difference between industrial and studio production.3 But if he was a manufacturer, he was no ordinary one; division of labour may have increased production beyond that of a studio, but it did not standardise it. William Moorcroft’s pottery was thrown, not moulded, and even Powder Blue, designed for production in large quantities, retained, in the words of Herbert Read, a ‘personality not found in wholly mechanical production’.4 Unlike Wedgwood, he did not seek to turn his decorators into machines ‘as cannot err’,5 and if design was the watchword of manufacture, for Moorcroft it was individuality. It was a distinction recognised implicitly in 1930 when, on the occasion of Wedgwood’s bicentenary, he was pointedly described in The Daily News and Westminster Gazette as ‘one of the most individualistic potters of his time’,6 a striking contrast to the manufacturer being commemorated.

Moorcroft’s method of production was very much in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts architect John Dando Sedding, who saw architecture as an art of collaborative creation:

[…] the architect uses the best faculties of his fellow craftsmen as well as his own, much as the musical composer secures the services of the best soloists and the best chorus and orchestra to render his oratorio.7

Sedding’s analogy of music was particularly appropriate to Moorcroft’s practice, which came close to that of a performance art. Unlike an architectural drawing, which represents in exact detail a single object to be realised, Moorcroft’s designs were more akin to a musical score, brought to life multiple times and whose every enactment was subject to infinite variations—on the potter’s wheel, in the decorating room and in the kiln—just like a live performance, every one different, none definitive. It is not to say that he approved everything which emerged from the kiln, but each piece was judged on its own terms, and not simply with reference to a template. The same individuality characterised his designs, adapted and redrawn for each different shape, and whose colour palette was often customised for particular retailers, allowing them to stock wares which were exclusive. As a result, very few pieces were made in large quantities, with the same decoration, on the same shape, in the same colours. His pieces were created in series, but each had its own identity, like flowers of the same species, their design familiar, their detail unique. It was a characteristic noted in some of the earliest reviews of his pottery:

All the schemes are the conceptions of an artist, they are carried out by artists, and no pieces can be exactly alike. As in nature, so in art; there is always infinite variety, both in form and color.8

This fusion of design and individuality was tellingly enacted on the base of his wares. One of Wedgwood’s defining innovations was to mark each pot with a factory stamp rather than a written sign in ‘the time-honoured manner of the old faience potters’,9 its unvarying appearance mirroring the pot’s perfect replication of a given design. From the start of his independent career, Moorcroft, too, impressed his name (the registered trademark of his firm) on the base of his pots, but this was most often accompanied by his signature (or initials), personally applied. To do so was not just to identify himself as the designer of a template, but also to associate himself with the individuality of a particular object. This distinction of his work from industrial production was underlined in the 1930s, when he replaced the firm’s stamp with a stamp of his signature and the words ‘Potter to H.M. the Queen’, the (doubtless conscious) allusion to Wedgwood accompanied by an affirmation of his own individuality; this stamp was itself accompanied, more often than not, by his own hand-written sign. It was an eloquent declaration, at a time when industrial standardisation, often explicitly traced back to Wedgwood, was becoming the new orthodoxy.

Moorcroft’s practice enacted an aesthetic principle, but it had a social dimension, too. At the end of his Story of the Potter, Charles Binns commented darkly on the working conditions of decorators in the pottery industry:

That he [the modern decorator] is in some sort reduced to the level of an automaton is more his misfortune than his fault, for in the rush and whirl of competition the demons of speed and cheapness rule. Strong, indeed, must be the manufacturer, and wealthy the capitalist, who can follow the bent of an artistic mind in the production of pottery for the people […].10

Moorcroft never lost sight of his decorators, and even at the end of his career he was designing pieces which gave them scope to show their skills, both in tube-lining and painting. Binns’ book was published in 1898; Moorcroft would combat the ‘demons of speed and cheapness’ for the next five decades, resisting the model which had defined the practice of Josiah Wedgwood and continued to characterise modern factories.

When Moorcroft was described in 1913 as ‘a manufacturer but also an artist’,11 the writer clearly perceived his fusion of these two models. So, too, did the author of the obituary in the Pottery and Glass Record who described him as a ‘post-Morrisite’,12 a telling remark at a time when the legacy of Morris was itself being identified in the radically opposed worlds of factory and studio. Pevsner included him in his Pioneers of the Modern Movement, and significantly used his words as the epigraph to his Enquiry: ‘What business have we with art at all, unless all can share it?’13 For Leach, conversely, what defined Morris was his opposition to industrial production, which culminated in ‘the individual, or artist, craftsman’.14 Moorcroft’s was a distinctive variant on these two perceptions of the Morris legacy. He explored a path between factory and studio, individualising a process of serial production to create what the Pottery and Glass Record called an ‘ideal link between the craft and the industry of potting’;15 it was one of the foundations of his commercial success.

While Crane described the craft revival as ‘a world within a world; a minority producing for a minority’,16 and potteries such as de Morgan or Della Robbia, closely associated with Morris’s principles, struggled to remain viable, Moorcroft brought ‘common things made beautiful’ to a wider market than individual makers were able to achieve. It is a sign of its broad reach that it was more widely marketed than most craft wares, available in (high-end) stores. In a review of the Omega Workshops, The Times noted that an artist’s work made for sale in retail outlets was designed ‘according to the demands of the shopman, not according to his own ideas’, characterising the result as ‘commercial art […] modish rather than beautiful’.17 This was clearly not the case with Moorcroft, whose relationship with Liberty’s exemplified his artistic autonomy. The store was long associated with the commercialisation of modern decorative art, famously scorned by C. R. Ashbee as ‘Messrs Novelty, Nobody & Co.’,18 for selling under their own name work commissioned from leading Arts and Crafts designers and factory-produced to appear individually made. Art was anonymised and craft reduced to a ‘look’, for the commercial benefit of the retailer. Not so Moorcroft’s pottery. This was neither mechanised nor concealed under Liberty’s name; it was made by Moorcroft, sold in his name, and appreciated on its own terms. For more than thirty years the store were investors and partners in his firm, but their relationship was not simply a financial one; it provided a high-profile gallery for some of his most adventurous and innovative designs.

The success of Moorcroft’s ware may be observed in its distribution and quantified in his accounts, but the reasons for its appeal are to be found in other evidence of its reception, in reviews or private correspondence. Even retailers did not regard it simply as a commercial commodity, as one explained in a letter to Moorcroft of 28 December 1943:

Your pottery has just arrived, it is exquisite! and I am sure Keats makes it very clear to us that with a thing of beauty, its loveliness increases. I shouldn’t like just anyone to buy your ware who simply has money (as is so often the case these days), I want to sell it only to a person who can appreciate the fineness.19

This was not just pottery which sold well; it was pottery which struck a chord.

2. Pottery for People

Given the scale of Moorcroft’s works, his ware was never intended for a mass market. But the breadth of his output, from the functional to the decorative, from small items of everyday pottery to works of exhibition quality, implied a target market ranging from those of modest means to wealthy connoisseurs. It was a noted characteristic of his ware, however, that each piece, whether destined for the kitchen or the collector’s cabinet, was designed and created with the same attention to detail. The Pottery Gazette compared his exhibition pieces at the Liverpool Walker Art Gallery, with items to be seen at the British Industries Fair:

[…] although his forthcoming exhibit at the Fair will contain many styles of decoration which are not beyond the reach of people of only modest means, this same high quality will be evidenced. We cannot doubt this, for we know it to be Mr Moorcroft’s aim, in whatever he makes, so to imbue his creations with human appeal that they carry with them a sense of joy of possession.20

And this is how his pottery was received. His Powder Blue teaware inspired ‘joy of possession’ in owners across a wide social and aesthetic spectrum. Its popularity long predated its public appreciation by Pevsner, or its presentation as a high-profile gift for a royal wedding, and it continued throughout and beyond the heyday of Clarice Cliff’s influential modern style. Its appeal could not be theorised by the many who bought and enjoyed it, but it was indisputable, widespread, and enduring. A letter of 14 January 1936 from one customer captured its impact; the pleasure it gave transcended fashion—it was not to be discarded, but to be replaced:

You were good enough to tell me that I might write to you for replacements of my powder blue service when these were necessary. I love my service, and treat it with every care consistent with using it, but have come to the point when I should be ever so glad if I might purchase some pieces […]

There is abundant material evidence, too, that many of Moorcroft’s other functional objects—tableware, tea caddies, biscuit boxes, jardinières, scent bottles, vases, lamps, candlesticks, inkwells, tobacco jars—were a part of their owners’ lives, and were used, damaged, and even repaired.

Purely decorative wares—vases clearly ornamental rather than practical in design, cabinet plates, decorative cups and saucers, miniatures—inspired similar responses; they were, for many, an essential and inseparable part of their owner’s domestic environment. An (undated) letter from the later months of 1940, is characteristic of many Moorcroft received, describing a relationship with his pottery which extended back at least thirty years:

[…] apart from our table pottery which was all Powder Blue, we had all our rooms furnished with the ware that suited the other colourings: from sang-de-boeuf to Murena and then on to more recent designs such as the Orchid, we had pieces of all of them. It became a recognised thing in the family for presents to be a piece of Moorcroft for some particular spot in the house.

It was axiomatic that even Moorcroft’s least sophisticated pieces were appreciated for their beauty, and some functional objects were clearly never put to use, their value as decorative objects being value enough. This was everyday art, designed to be practical and/or ornamental, but always, above all, to bring joy to the owner.

For many, though, the pleasure it provided was more than simply ‘joy of possession’. Correspondents did not always have the vocabulary to describe the impact of this ware, but its intensity, and immediacy, were beyond doubt. Moorcroft’s pottery did not simply beautify a room, it compelled its owner’s attention. This effect was tellingly expressed in a letter to Moorcroft from Austin Reed Ltd., dated 24 April 1935, acknowledging receipt of a vase ordered for their (relatively) new headquarters. What may well have been bought as a decorative item clearly had an impact which took the writer by surprise: ‘The only trouble I find with this creation of yours is that it is impossible to stop looking at it. It expresses a masterpiece, and we are very happy with it.’ It was this haunting quality which was often picked up in reviews, from the start of his career when it was likened to poetry, to the 1930s when the character of ‘soulfulness’ was discerned in it. As one review succinctly put it, ‘Moorcroft pottery is no ordinary pottery’.21 It is doubtless for this reason that he was often described as an artist, and why his work was presented in the interwar years in terms similar to those used in reviews of studio pottery. What Marriott said of William Staite Murray in a review of 15 November 1926 was equally true of Moorcroft: ‘these pots are not to be described; they are to be experienced.’22

The nature of this quality is suggested in a letter of 19 August 1943, written by Frank C. Ormerod, a celebrated ENT surgeon, to a patient who had sent him a particularly fine Moorcroft vase as a thank-you gift:

Thank you very much indeed for the extraordinarily fine piece of Moorcroft you sent me. I feel it is quite absurdly out of proportion for merely offering you a little advice, which happened to turn out right. Nevertheless, I am very grateful and appreciate very much all the kind thought which went into choosing for me what is indeed a museum piece. My wife’s father, the late William Burton, was a very distinguished potter, and she considers herself no mean judge of a pot. She asks me to thank you on her behalf too, and to say that she considers it the finest piece of Moorcroft she has ever seen, and that she values it very greatly as an addition to our collection.

Moorcroft’s pottery was at the centre of this exchange, the language through which deep feelings could be expressed and recognised. For the donor, the vase was clearly intended to enrich the life of its recipient, just as the medical advice had evidently made a life-changing difference to him. And Ormerod read this message perfectly; to appreciate the quality of the vase was to appreciate the depth of the patient’s gratitude. It is a sign of the esteem in which Moorcroft’s ware was held that it could be guaranteed to achieve this purpose; its recognition as a work of art by the daughter of William Burton, one of the great ceramic chemists of the age, underlined the validity of that reputation. But functional ware, too, inspired similar responses. For an American customer writing on 13 June 1942, Moorcroft’s ware was both eloquent and inspirational:

I now have 161 pieces, counting cups and saucers as one, and broth cups and saucers as one. A very nice little cupboard full. However, I am interested in setting a table with Moorcroft not only for breakfast, luncheon or supper, but for dinner also. […] I note your remark, ‘Making objects that will help to awaken a joyous interest in life.’ We are of one thought […]. You make beautiful porcelain which adds greatly to the joy of eating […] Some folks walk so aimlessly thru life, they see no beauty, they see nothing of interest, they wonder why they were born, and they wonder what it’s all about. […] Don’t ever let that kind of life be ours. You keep right on making your beautiful blue porcelain. […] That Moorcroft is simply beautiful. [Emphasis original]

Such reactions corresponded exactly to how Moorcroft conceived of his vocation from the very beginning of his career. At the end of his 1905 diary, he transcribed a comment from an essay on the music of Richard Strauss; this was what his pottery was all about, whatever its apparent function:

It is one of the functions of music to make us feel, another to make us think. The greatest masters are [ever] those who make us both feel and think in one vivid moment.23

And for one correspondent writing on 23 September 1944, less than a year before Moorcroft’s death, this was precisely the effect of his ware: ‘I love the beauties of nature, and so mentally and spiritually I absorb Moorcroft.’ When Marriott suggested in his Obituary notice that Moorcroft’s decorative work had gone out of fashion, this was very misleading. Partly because its absence from the marketplace was entirely the result of wartime restrictions, not of declining popularity; but partly, even principally, because Moorcroft’s pottery was never really ‘in fashion’ at all, and never sought to be. The ‘joy of possession’ implied in correspondence was not the comfort of the familiar, or the pleasure of owning a fashionable object; it was a much deeper and more enduring engagement with the ware.

The many letters written to Moorcroft testify to this impact of his pottery; the fact that he preserved so many of them suggests that this was (at least) as important to him as its financial success. This was a relationship of artist and public which was not simply commercial, but implied a closer integration, an affinity of the kind described by Walter Crane:

Appreciation and sympathy are […] enormously stimulating to artists. […] If they are understood at once, then the artist knows he is in touch with his questioner, and that he speaks in a tongue that is comprehended […].24

Moorcroft’s language was indeed understood, and it was an exchange as enriching for the potter as for the owner of his ware. As he wrote in a letter to his daughter, Beatrice, of 10 March 1929, it made his life worthwhile:

[…] it has been my good fortune to at least have made a few things that have found appreciation. If only one is able to do one small thing that will perpetually give happiness to someone, then one has not lived altogether in vain.

For Ida Copeland, an active campaigner for social reform and former MP for Stoke, writing to Moorcroft on 22 March 1945, the effect of his ware transcended the aesthetic and touched on the moral; it was a quality of the pots, but it was seen also, significantly, as a quality of the man:

[…] One thing is certain, beautiful objects created with love in one’s heart will remain an inspiration and lead many to seek the good and beautiful in the years to come. So be of good heart. I rejoice to have had the pleasure of meeting you and seeing your work on life’s journey.

3. Individuality

Moorcroft was more comfortable, and arguably more effective, expressing himself in clay than in words. His personal motto—Facta non verba—paradoxically said it all; what he made meant more than words, and he believed that a good pot needed no other advocacy than itself. Reactions to his ware clearly confirmed this belief. And yet, although he never systematically developed his ideas in public (and never completed the projected book on his work), he did express informally, in letters to family, friends, customers, or in diary jottings, some of the values and ambitions which motivated his work.

The very act of making pottery had the deepest significance for Moorcroft. Clay took the potter back to the origins of life, and was the perfect medium for expressing his reverence for the created world. His pottery was not simply an object, it was a statement. This was manifested in the creation of his distinctive ceramic colours, highlighted in reviews throughout his career. Like studio potters he deprecated the use of onglaze enamels, describing it as ‘no less offensive than it would be to paint the bark of a tree’,25 but unlike them he did not limit himself to the natural oxides in the clay.26 For Moorcroft, ceramic chemistry unlocked the hidden beauties of the earth, brought to light, and to life, by the fire of the kiln. To discover new colours was to uncover new dimensions in nature, a source of delight which he shared with his daughter in a letter of 25 October 1927: ’how glorious it is to find that the Earth has hidden within it treasures of colour that it is impossible to fully imagine, however quick or alive one’s imagination may be.’ And what was true of colour was true, too, of design. In a letter of 1 March 1943, to Henry Strauss, Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Town and Country Planning, he explained the importance of nature as his inspiration, but experienced directly, not mediated by past traditions:

[…] we must think naturally, and look neither to the distant past nor to Greece or Rome for inspiration, but to the gentle influence of the riverside, or to the budding trees in springtime. […] The line we see in the flowing river, in the bird in flight, and the colours we see will give us the material and the spiritual motive to design.

His aim was not mimetic representation, but to express through line, form, and colour the harmony and permanence of nature. Moorcroft expressed this sense of vocation in a letter to the author George Beardmore, on 13 August 1943; it was one of his most comprehensive, and fervent, affirmations:

Each object I make is an original piece, and is developed with the ever constant feeling that each atom comprising the piece is a part of the beginning of things. In each piece there are the same elements that form us. And with such material, one feels that one has a sacred trust in using the material. I obtain my results by and through the application of physics and the chemistry of metals, added to my drawing from Nature, where pattern appears. The pattern then is a part of the piece, and not merely applied. Each molecule is in complete fusion, and the elements all form a happy reunion, and are a part of that beginning.

It was from the perspective of a potter that Moorcroft conceived his art. It was not about the decoration of a clay vessel, it was about creating a ceramic object, its constituent elements all of a piece, literally and figuratively. The result was work often noticed for its integrity, a quality equivalent to what Pevsner called ‘an indivisible (‘individual’) unity of soul, mind and hand’ in the single craftsman,27 and what a review of his display at the Ghent Exhibition called ‘cohesion’:

Moorcroft Ware is designed and executed entirely under the personal direction of William Moorcroft. […] The forms, the colour schemes, and all added ornament are wholly conceived by the originator. This imparts to Moorcroft Ware a sense of cohesion so often lacking in modern pottery. It is in the combining of rare colour with form that one’s interest is at once awakened […], but there is also an individuality that places this pottery in a class distinct from all other types.28

Moorcroft’s pottery was individual because it was different, and because it was the conception of a single mind; but it was individual too because it was personal. It had little in common with the formal neo-classicism of Wedgwood, nor with Morris’s pre-industrial vision in his 1882 lecture, ‘The Lesser Arts of Life’, with its preference for a ‘workmanlike’ finish. Nor was his aesthetic close to the medievalism of either de Morgan or the Della Robbia factory, both of which sought to recreate the styles or techniques of an earlier age. What mattered to William Moorcroft, above all, was integrity, as he expressed in a letter to Beatrice on 14 October 1927: ‘how joyous it is to work. How wonderful it is to have the power to express oneself, and how important it is that the expression should be true. As Shakespeare says: To thine own self be true’. This conception of his art doubtless prompted the frequent references to him in reviews as an individual rather than as a firm, and even his categorisation in the Pottery and Glass Record as a ‘studio potter’.29 For all that his production technique distinguished him from studio pottery practice, he was, like a studio potter, the sole designer of his ware. This was relatively rare at the start of his independent career; by the end of the 1930s, it was almost unparalleled, as was implied by Forsyth in a talk to the Ceramic Society: ‘no firm could exist with a full measure of success on the work of one designer, however good, any more than a conductor could exist on producing the works of one composer.’30 The result was a very personalised output, the expression in every respect of Moorcroft himself; he was, in the words of one review of 1929, a ‘One-Man Factory’, not so much the head of a firm as its defining spirit.31

This personal quality was evident, too, in the way he ran his business. Like a manufacturer, he supplied retail outlets both direct and via distributors, but he also, and quite atypically, dealt direct with individual buyers. A reply from Moorcroft himself to the speculative enquiry of one customer, evidently a complete stranger, elicited this (undated) response. It was clearly a business practice quite out of the ordinary:

I am extremely grateful to you for your postcard dated October 22nd; it was particularly kind of you to find time to deal with my inquiry yourself. […] it was only as a last resort that I ventured to write direct to you, and it was beyond my best expectations that I should receive so favourable a reply.

Equally distinctive was his willingness to show individuals round his works, and not just commercial buyers. One correspondent, evidently a collector of Moorcroft’s decorative ware, recalled in a letter of 14 January 1936 the way his works were run; his door was always open:

As I look round my lounge every evening at my treasured Moorcroft vases, I often wish I were back in the days of Stoke, when I could visit your works and go through your storerooms with their amazing stock of wonderful pieces; but in the end it is probably all for the best, because I should be tempted at every turn, and probably spend more than I ought to!

This was an astute commercial strategy, but it was also, and, one suspects, above all, a reflection of Moorcroft’s vocation as a potter. To see how his pottery was made, was to increase the pleasure it provided. Another letter, dated 19 October 1937, shows how effective this was:

The vases look beautiful and are a constant daily delight to both of us. Now that I have seen your medium before the enormous heat mixes and determines the colours, it has increased greatly my admiration and interest in your art.

Unlike either Wedgwood or Morris, Moorcroft did not present himself as either a pioneer or protester; he was a potter with a vocation, but he was not on a crusade. Such was his irreducible individuality, that he could not be imitated; as one review of 17 September 1926 put it: ‘What will happen when Moorcroft dies, I don’t know. […] They’ve tried all over the world to copy his particular glaze and raised flower design, but can’t.’32 But this personal dimension was intimately connected with his sense of engagement with his times. In different ways, his designs suggested his own discreet response to the age: the muted tones of many wartime designs expressing his persistent faith in the enduring beauty of the natural world even in the darkest times; his landscape scenes of moonlight, evening or dawn an oasis of calm in a turbulent post-war world; his fish designs of the 1930s, lively and unfettered, playfully resisting the angularity of the modern machine world; his last floral decorations embodying one final defiant celebration of nature in the face of impending war. In a letter to Beatrice of 20 November 1930, he had voiced this sense of purpose in his art:

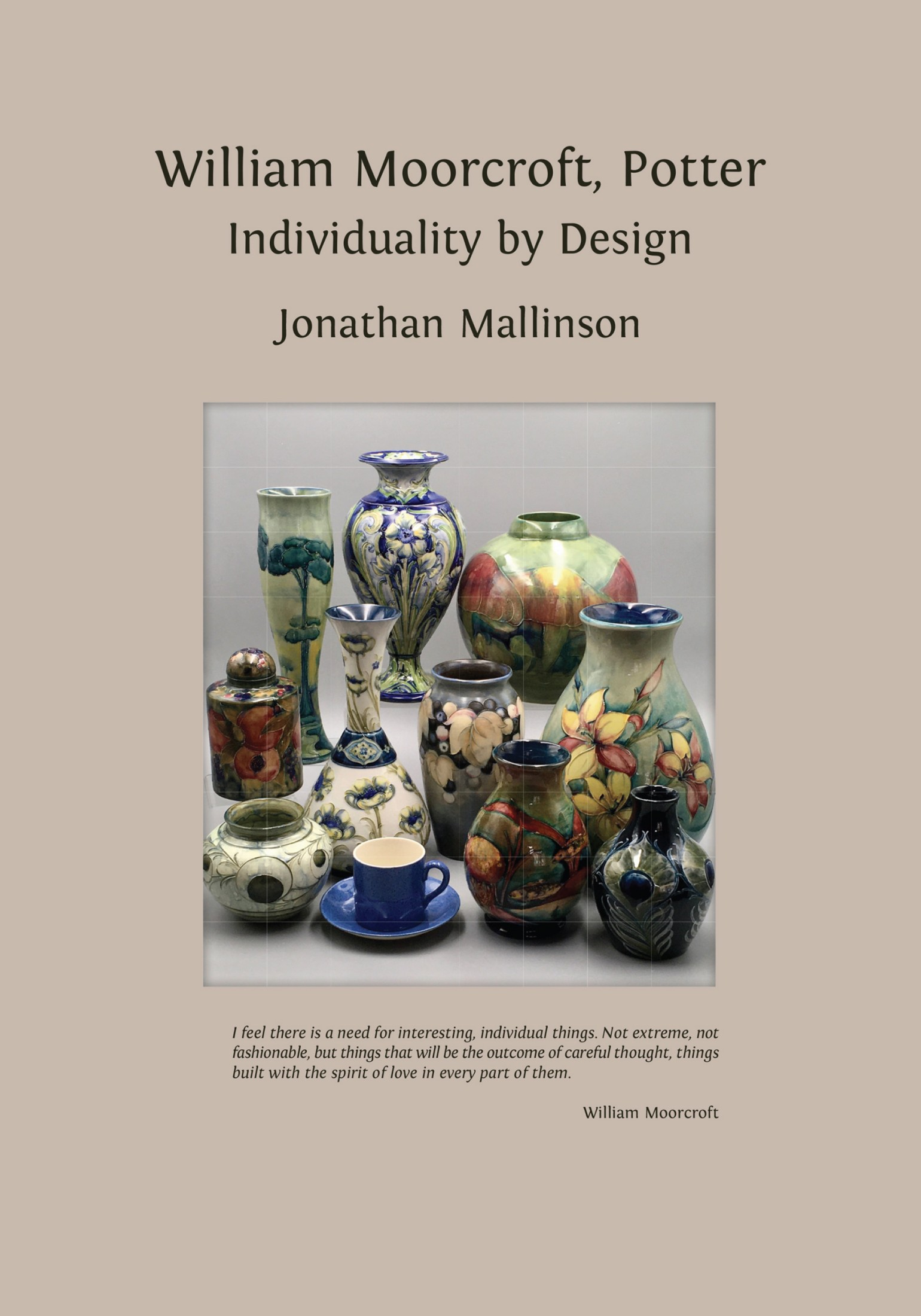

I feel there is a need for interesting, individual things. Something with individual thought expressed therein. We want pleasant things to live with. Not extreme, not fashionable, but things that will be the outcome of careful thought, things built with the spirit of love in every part of them. Life will be more worth living when we seek such means of expression.

In his Individuality, Voysey used this term to describe what he saw as a defining quality of the true artist, one whose work was neither modish nor eccentric, but which had its own integrity, personal but not self-regarding:

We must first and foremost demand from the artist that he be sincere; his own temperament and sense of proportion he cannot get away from—they must influence his work at every turn, but should not be his motive for addressing us. […] And to create beauty for others is a joy that must subdue the desire for self-assertion.33

It was in this way that Moorcroft conceived of his vocation, true to himself in the service of others. Just as his signature changed significantly over nearly fifty years, yet remained the unmistakeable mark of its originator, so too his work, for all its different styles, retained its individual spirit, and its enduring appeal. Writing towards the end of Moorcroft’s career, on 29 April 1939, one correspondent was categorical about the distinctiveness of his ware: ‘All the pieces are very beautiful and as usual easily distinguishable as your work; I think I should know it anywhere, for there is none other like it, and is always a joy to the eye.’

The very particular nature of this individuality and its impact is powerfully conveyed in two letters written to Moorcroft more than twenty years apart, by writers of very different cultural and social background, yet united in their response to his ware. The first was written from Montreal on 9 August 1923 by Kate Reed, interior designer for Canadian Pacific Railways, for whom Moorcroft had made a pansy tea set before the war. Reed had never met Moorcroft, and yet she clearly sensed his presence in his ware:

I pass Birks’s window many times in a month and always gaze at your work, and feel a peculiar nearness to it, and you. […] Some day I hope we will look into each other’s faces, and shake each other’s hands, and I will say to you with sincerity: ‘You have made the world better, for you have put beauty into it!’

The second, dated 25 August 1944, was written by a resident from the neighbouring town of Hanley, thanking him for showing her round his works. At the centre of her experience was (once again) Moorcroft himself, but in person this time, animating his works and the pottery he created:

I feel I must write and thank you for the lovely gift you made me this afternoon. I am such a lover of colour, and your colours are so beautiful that I shall cherish your vase all my life. It was indeed a privilege to go round your factory. I was struck by the happy spirit that seemed contained therein. Your work is your life, I can feel that. Please go on. It is work such as yours that will live when we are long forgotten. I am proud to have a piece of your handicraft in my possession. Thank you for your generosity.

In many respects, the two letters could not be more different. One describes his ware in a retail environment, the other at its place of origin. One exemplifies its international reach, the other expresses its local impact. One is inspired by pottery of wide-ranging design experiment at a time of post-war prosperity, the other dates from a time of wartime restrictions and a much more limited output of decorated ware. One writer was a successful designer, the other, neither critic, retailer nor artist, was a member of the public reacting instinctively to his work. But beneath these differences, the similarity of the two reactions is all the more striking. Neither letter, significantly, describes a commercial transaction, but a deeper and more significant experience: a sense of delight at the sight of Moorcroft’s pottery; an instinctive perception of beauty which inspires a more reflective consideration of its value, extending beyond the immediate present and beyond the appreciation of the writer; and, above all, a recognition of the potter’s personal investment in his work and the joyful spirit which radiates from it, vital in its force, enduring in its effect. Both writers clearly felt the need (like so many other correspondents) to communicate the effect of this pottery upon them. And both captured, in their quite different ways, and as well as any subsequent obituary, the individual spirit of William Moorcroft and the unique appeal of his art.

1 B. Rackham & H. Read, English Pottery, its Development from Early Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), p.125.

2 C. Marriott, ‘Moorcroft Pottery’, The Times (4 March 1939), p.10.

3 Cf. W. Gropius, The New Architecture, p.54: ‘subdivision of labour in the one and undivided control by a single workman in the other.’

4 H. Read, letter to W. Moorcroft, 12 June 1943, William Moorcroft: Personal and Commercial Papers, SD1837, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives [WM Archive].

5 J. Wedgwood, letter to Bentley, 7 October 1769.

6 The Daily News and Westminster Gazette (19 May 1930).

7 J.D. Sedding, Art and Handicraft (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1893), p.165.

8 Canadian Pottery and Glass Gazette (August 1908), p.8.

9 Rackham & Read, English Pottery, p.98.

10 C.F. Binns, The Story of the Potter (London: Hodder & Stoughton [1898]), pp.238–39.

11 The New Witness (26 February 1914), p.540.

12 PGR (October 1945), p.21.

13 W. Morris, letter to the Manchester Examiner (14 March 1883).

14 A Potter’s Book, p.14.

15 PGR (October 1945), p.21.

16 W. Crane, ‘Of the Influence of Modern Social and Economic Conditions on the Sense of Beauty’, Ideals in Art (London: George Bell & Sons, 1905), 76–87 (p.86).

17 ‘A New Venture in Art. Exhibition at the Omega Workshops’, The Times (9 July 1913), p.4.

18 C.R. Ashbee, Craftsmanship in Competitive Industry (Camden: Essex House Press, 1908), p.155.

19 All unpublished documents referred to in this chapter are located in WM Archive.

20 Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (February 1937), p.252.

21 PG (April 1930), p.612.

22 C. Marriott, ‘Stoneware Pottery’, The Times (15 November 1926), p.19.

23 James Huneker, Overtones: A Book of Temperaments (New York: Ch. Scribner’s Sons, 1904), p.50.

24 W. Crane, ‘Of the Social and Ethical Bearings of Art’, Ideals in Art (London: George Bell & Sons, 1905), 88–101 (p.99).

25 ‘How Pottery Should “Grow”’, The Daily News and Westminster Gazette (19 May 1930).

26 Cardew explicitly distinguished himself from the ceramic chemist in his article ‘Slipware Pottery. Following the English Tradition’, Homes and Gardens (May 1932), 548–49: ‘A potter’s processes should be as far as possible in imitation of natural processes, not of the unnaturally pure procedure of the experimental chemist.’

27 An Enquiry into Industrial Art in England, p.188.

28 Unsourced press cutting in WMArchive.

29 PGR (October 1945), p.21.

30 ‘Design in the Pottery Industry’, PG (March 1937), p.399.

31 Sunday Dispatch (24 March 1929).

32 Unsourced (Australian) newspaper review, WMArchive.

33 C.F.A. Voysey, Individuality (London: Chapman & Hall, 1915), p.75.