Introduction: William Moorcroft, Potter

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.16

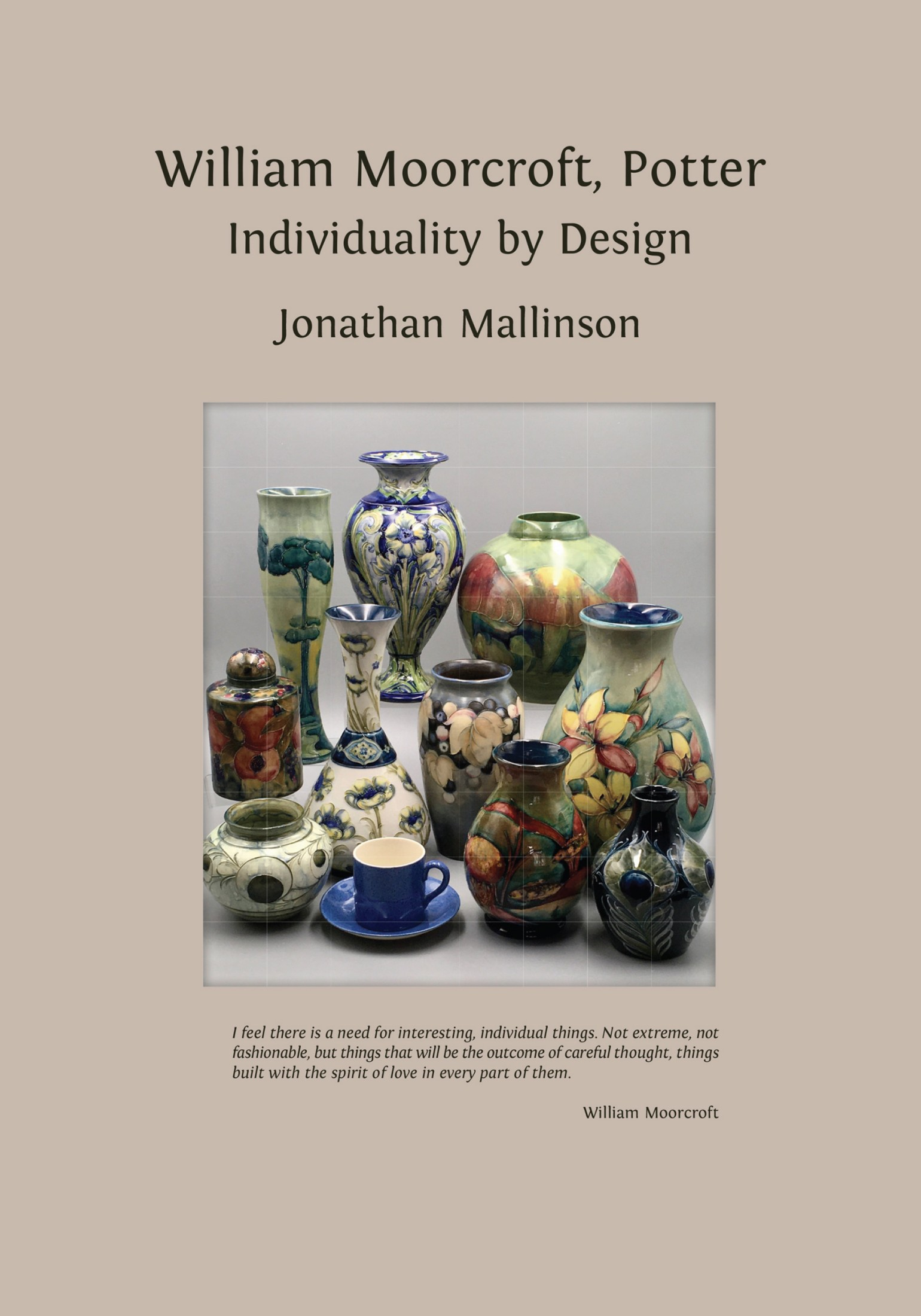

William Moorcroft (1872–1945) was one of the most celebrated potters of the early twentieth century. His work was admired by collectors and connoisseurs of ceramics, exhibited in museums, reviewed in leading art journals, and awarded the highest honours at World’s Fairs over a period of more than thirty years. His decorative and functional wares were stocked by some of the most prestigious retail outlets in the world, from Thomas Goode & Co. in London to Eaton’s in Toronto, from Tiffany in New York to Rouard’s gallery A la Paix in Paris, and his long collaboration with Liberty’s was an unprecedented and highly creative association of innovative designer and progressive retailer. His earliest work, launched under the title Florian Ware, was rated a ‘chemical and artistic triumph’,1 and forty years later examples of his tableware would be singled out as models of ‘undatedly perfect’ design.2 He was one of only a handful of potters at the time to hold a Royal Warrant, and at his death he was said to be the equal of any potter since Josiah Wedgwood.3 In a career which extended from the final years of the Victorian age to the end of the Second World War, a period of political upheavals, economic crises and conflicting aesthetics, artistic acclaim was matched by commercial success.

This was the achievement of a potter who worked simultaneously as artist, chemist and manufacturer. Moorcroft spent the first sixteen years of his working life as Manager of the Ornamental Pottery department at the forward-looking firm of James Macintyre & Co., Ltd., where he was responsible for the design and production of both functional and decorative wares. Under his control, this soon became one of the most renowned art potteries of its time. When Macintyre’s closed the department in 1913, Moorcroft (with financial support from Liberty’s) established his own pottery from where he continued to enhance his reputation as a ceramic artist, even in the challenging conditions of wartime and post-war Depression. In both these phases of his career, he designed form and ornament for all the wares produced; he created his own distinctive decorative technique, and developed a unique palette of underglaze colours; he oversaw the employment and training of his decorators; and he was responsible for the promotion and sale of his work. This combination of roles was without equivalent.

Moorcroft is most often classified among art potters, a category used to describe makers of largely decorative wares, active roughly between the years 1870 and 1920. It is a broad category, both chronologically and conceptually. It includes the craft studios of large firms such as Doulton, Minton or Wedgwood, independent factories such as Linthorpe or Della Robbia, and smaller enterprises focussed on the work of individual potters such as William de Morgan, Bernard Moore or William Howson Taylor. Art pottery covered a wide range of decorative styles, from the refined low-relief ornament of Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon’s pâte-sur-pâte studio at Minton, to the charming sgraffito scenes by Hannah Barlow at Doulton Lambeth; from the dramatic glaze effects of Howson Taylor at his Ruskin Pottery, to the stylized lustre designs of Pilkington’s Royal Lancastrian ware. But it was unified by its principal focus on decoration, be it that of an artist/decorator, or of a ceramic chemist; the vessel itself served implicitly as a canvas, some potters even decorating blanks supplied by other firms. It was also an essentially collaborative enterprise, its ‘authorship’ generally attributed to the firm which produced it. If individual names were associated with objects, it was most often the name of the decorator, artist or chemist, who might initial or otherwise identify their work.

In terms of organisation and aesthetic, Moorcroft clearly had much in common with the manufacturer of art pottery. Both his department at Macintyre’s and his own works at Burslem were characteristic of many industrial workshops, employing a team of throwers, turners, and decorators to assist in the making of the wares. And yet, for all that, Moorcroft’s practice differed in significant ways. Whereas the design of most art pottery was essentially collaborative, Moorcroft designed the complete object, form, ornament and colour together. And although he did not make the wares himself, he was at the centre of production in ways which had few parallels in art potteries: he drew the decoration template for each shape, he created the oxide mixtures for his colours, and, in the case of his flambé wares, he personally fired the kiln. This investment in his work would soon be noted. He was rapidly distinguished from the corporate identity of Macintyre’s and recognised as a name in his own right, and after 1913, when he was working for himself, his pottery was as often attributed to him as an individual as it was to the firm in whose name he operated. At the time of his death, he was even classified as a ‘studio potter’.4 This term was associated, from the 1920s particularly, with a quite different concept of pottery, its principal emphasis falling on the pot as a thrown vessel (rather than as a decorated one), the creation of a craftsman working alone and independently rather than the result of more collaborative enterprise. The designation did not imply that William Moorcroft fell squarely into that category, but it did suggest what distinguished him from the generality of art potters; Moorcroft did not simply decorate ceramic vessels, he expressed himself in clay.

What made Moorcroft stand out too, though, was not just the individuality of his art, but also his commercial success. Many highly regarded art potteries closed in the opening decades of the twentieth century, from Della Robbia (1906) and de Morgan (1907) to Howson Taylor (1935) and Pilkington (1938). Even at the end of the nineteenth century, the heavily subsidised output of Doulton’s Lambeth studio was described in an obituary of Henry Doulton as ‘one of the few sacrificial tributes of Commerce to Art’,5 and thirty years later the studio potter Reginald Wells would conclude (wearily): ‘do not imagine there is a living in so-called artistic pottery—there is not.’6 Throughout the 1920s, though, even as the country began to drift into a post-war depression, Moorcroft’s achievement was noted:

In Mr Moorcroft the present generation has an artist and a potter, who is practising successfully in commerce. The combination is remarkable, for it is one that is seldom met with.7

The emphasis is significant; he was not regarded as a manufacturer in the business of making pottery, he was recognised as an artist potter whose work had wide appeal. And this corresponded exactly to how Moorcroft saw himself. In the face of constant changes in taste and market conditions, he remained true to his artistic principles, often speaking out against designs which merely followed the trend of the moment. In a letter to The Times at the end of the 1925 Paris Exhibition which introduced a new ‘modernity’ to industrial design, he affirmed that artistic integrity, not fashion, was the route to commercial success. ‘If we are to succeed in the markets of the world’, he wrote, ‘it will be mainly by being ourselves’.8 His survival, even in the depths of the Depression, would be evident vindication of that belief.

This success was due, too, to the range and quality of the wares he produced. Moorcroft was more than just an art potter, and his market was not simply a market of collectors; he produced pottery both functional and decorative, from modestly priced tableware to exhibition pieces which commanded prices comparable to those of the most celebrated studio potters. But all were produced by the same means, to the same standard, in a range of prices affordable by customers across a broad social spectrum; in Moorcroft, commercial astuteness and artistic integrity came together. As one critic noted in the 1920s, even a modest piece of Moorcroft’s pottery is ‘regarded by thousands of people as a priceless possession’.9 His functional wares were in competition with those produced by much larger, mass-producing factories, and successfully so. His Powder Blue tableware would be the most striking example of this, hailed as an icon of modern design more than twenty years after its creation, and which continued to sell well even when the quite different aesthetic of Clarice Cliff was dominating the market. It was a model of industrial design and commercial success, yet it was made, significantly, by hand; in this respect, too, Moorcroft’s work spanned the worlds of the manufacturer and the artist.

It was this fusion of roles which clearly distinguished Moorcroft from (and for) his contemporaries, but it has led, paradoxically, to his relative neglect today. Being neither an individual potter nor a designer for mass production, he inevitably falls outside the scope of critical studies both of craft pottery and of industrial design.10 He is included in one reference work on art pottery, but his pottery is examined in entries on J. Macintyre & Co. and W. Moorcroft Ltd., thereby implying corporate authorship of the pottery produced.11 In another study, his designs from the ‘Art Deco’ period are discussed under the name ‘Moorcroft’, in a section devoted to ‘Established Factories’.12 In only one book is his work considered under his own name.13

This perspective is significant, and it has informed other accounts of Moorcroft’s work. He has been situated in a group of artist potters ‘concerned about running an efficient pottery with a marketable, profitable product’,14 and has been attributed with the ambition to create a ‘successful international commercial art pottery business’.15 Moorcroft’s close personal involvement in the design and production of his pottery has been similarly evaluated from a perspective of business management. One study characterises him as an ‘autocrat’,16 and another, while conceding his accomplishments at the time, considers his organisational model ‘detrimental to the continued and future success of the business’.17 If his contemporaries saw him as ‘a manufacturer, but also an artist’,18 it is as a manufacturer that he is principally considered today. In consequence, his pottery is implicitly construed as a trading commodity, and his enduring achievement situated not in the works he made, but in the firm he established in 1913, and from which pottery continues to be produced.19 The name ‘Moorcroft’ has taken on a generic force, and William Moorcroft’s identity has been absorbed, paradoxically, by the Company which bears his name. One writer has referred to his pottery as ‘old Moorcroft’,20 while another has conflated the firm’s entire production into one single entity: ‘There is no such thing as ‘old Moorcroft’ or ‘new Moorcroft’, just Moorcroft.’21 It is an ironic fate for a potter who came to prominence through the force of his individuality.

This construction of a corporate identity is quite consistent with the model of many art potteries such as Della Robbia or Pilkington, whose designers often worked to a particular house style, or whose collaborative mode of production implied a more commercial product. Indeed for many, only pottery created by a single craftsman can have the personal expressiveness of an art object. But to see Moorcroft in this light is to make assumptions about his practice and priorities inconsistent with his reputation at the time, and which sit uncomfortably with his conception of pottery as a vehicle for self-expression. Self-evidently, his contemporaries could have had no conception of Moorcroft as the originator of a firm which would survive beyond his time; but nor did they consider him simply as a manufacturer. Even the British Pottery Manufacturers’ Federation (BPMF) would explicitly categorise him as an artist, recognising in him quite different priorities from theirs, and when, in an obituary, he was likened to Josiah Wedgwood, it was (clearly) not Wedgwood the business man who was evoked, but Wedgwood the potter:

By the death of William Moorcroft, the art of pottery has lost a truly great exponent. In his mastery of the craft, as potter, painter and chemist, he was probably the equal of any potter since the days of the first Josiah Wedgwood. All his work was strikingly original.22

This book sets out to recover William Moorcroft. It is not the first chapter of a longer narrative, it is the story of a potter whose ambition was simply to be himself, individual by design, and whose success, artistic and commercial, would be founded on that.

1 A.V. Rose, ‘Florian Art Pottery’, China, Glass and Pottery Review, XIII:5 (December 1903), n.p.

2 N. Pevsner, ‘Pottery: design, manufacture and selling’, Trend in Design (Spring 1936), 9–19 (p.19).

3 ‘William Moorcroft’, Pottery and Glass Record [PGR] (October 1945), p.21.

4 Ibid.

5 The Graphic (11 December 1897), quoted in D. Eyles, The Doulton Lambeth Wares (1975); rev. L. Irvine (Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis Publications, 2002), p.134.

6 R. Wells, ‘The Lure of Making Pottery’, The Arts and Crafts (May 1927), 10–13 (p.13).

7 ‘Pottery and Glass at the Paris Exhibition of Decorative Arts’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review [PG] (September 1925), p.1398.

8 The Times (7 October 1925).

9 PG (September 1925), p.1398.

10 He is not discussed in E. de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), and there are just the briefest references in A. Casey, 20th Century Ceramic Designers in Britain (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2001), P. Todd, The Arts and Crafts Companion (New York: Bullfinch Press, 2004), and T. Harrod, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century (Yale: Yale University Press, 1999).

11 V. Bergesen, Encyclopaedia of British Art Pottery 1870–1920 (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1991).

12 P. Atterbury, ‘Moorcroft’: in A. Casey (ed), Art Deco Ceramics in Britain (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), pp.74–78.

13 J.A. Bartlett, British Ceramic Art 1870–1940 (PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1993).

14 G. Clark, The Potter’s Art: A Complete History of Pottery in Britain (London: Phaidon, 1995), p.129.

15 R. Prescott-Walker, Collecting Moorcroft Pottery (London: Francis Joseph Publications, 2002), p.32.

16 P. Atterbury, Moorcroft: A Guide to Moorcroft Pottery, 1897–1993 (Shepton Beauchamp: R. Dennis & H. Edwards, 2008), p.32.

17 Prescott-Walker, op. cit., p.33.

18 The New Witness (26 February 1914), p.540.

19 The story of Moorcroft’s firm after his death in 1945 has been told in different ways. In addition to the books of Atterbury and Prescott-Walker, see also Walter Moorcroft, Memories of Life and Living (Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis Publications, 1999); N. Swindells, William Moorcroft: Behind the Glaze. His Life Story 1872–1945 (Burslem: WM Publications Ltd., 2013; and three books by H. Edwards (aka Fraser Street): Moorcroft: The Phoenix Years (Essex: WM publications, 1997); Moorcroft: Winds of Change (Essex: WM Publications, 2002); Moorcroft: A New Dawn (Essex: WM Publications, 2006).

20 Prescott-Walker, op. cit., p.38.

21 Swindells, p.193.

22 PGR (October 1945), p.21.