3. Business Models and Digitisation

© 2023 Mathias Cöster et al., CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0350.03

In this chapter, we will give examples of how business models can support a strategic dialogue, by identifying activities that contribute to the realisation of strategy. We focus on how IT can contribute to value creation through the digitisation of activities, or how digitisation can constitute the very starting point of a business model. The chapter concludes with a consideration of how a business model analysis provides knowledge about how digitisation contributes to the development and implementation of strategies, goals, and goal fulfilment.

3.1 The Relationship between Strategy and Business Model Concepts

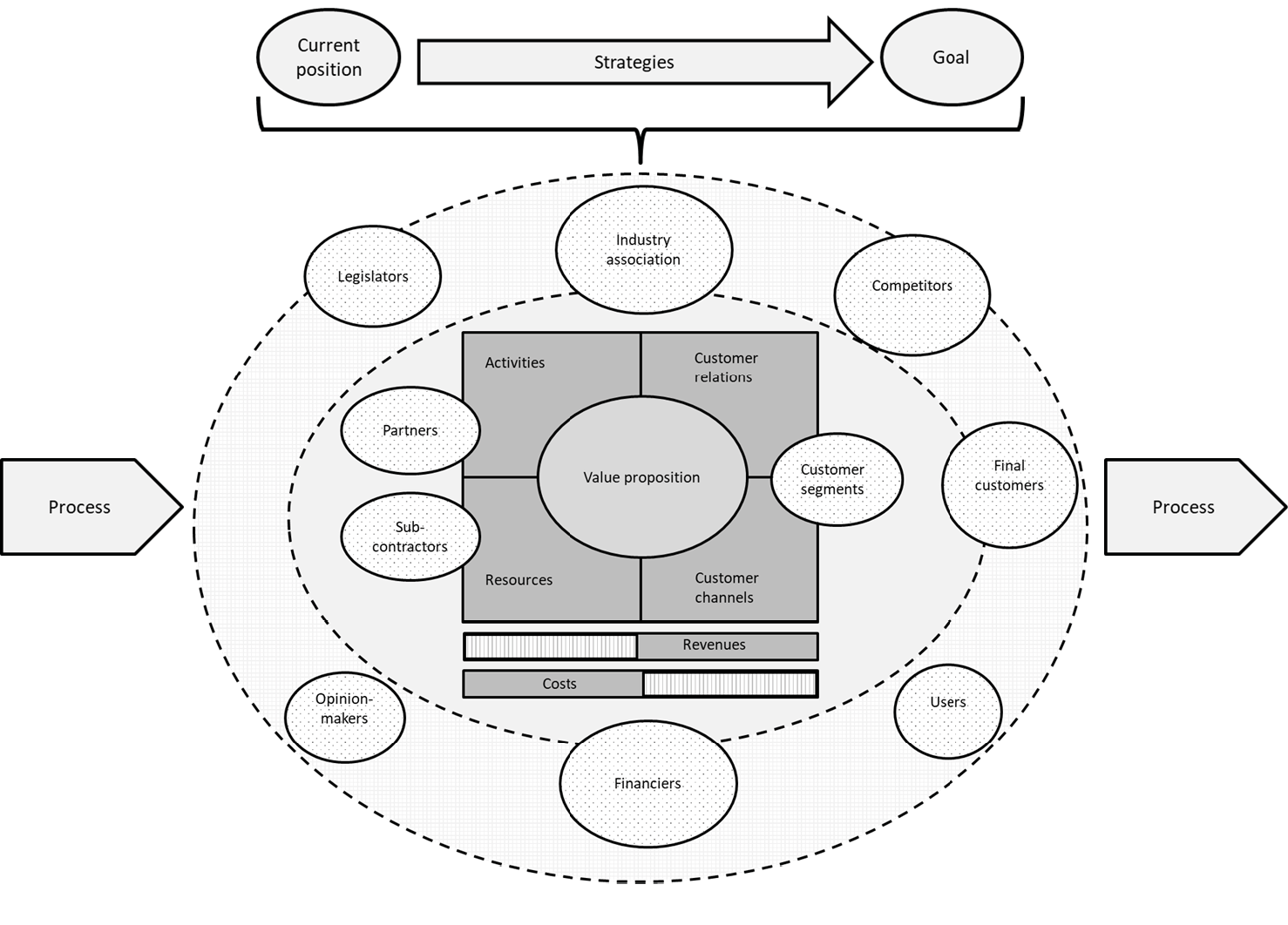

When we discussed the concept of strategy in the previous chapter, we emphasised that an organisation has different strategies at different levels, but that their overarching purpose is the same: they should indicate a direction, a long-term path for the organisation’s goals. However a strategy is not in itself an action plan. It is therefore necessary to identify how to work according to the strategy. In response to this question, the business model concept has gradually received more attention in recent years. Some of the definitions of a business model resemble those for strategy, and the difference may be seen as hierarchical. In Figure 3.1, strategy is depicted as the pathway from current position to desired goal. Strategies emphasise an overall perspective and can therefore accommodate one or several business models. They in turn act as a conceptual layer between strategy and the processes included in an organisation’s activities (that is, what an organisation does in practice). The business model concept can thus be useful when organisations must decisively identify factors in order to develop their processes and implement strategies.

Figure 3.1. The relationship between goals, strategies, and business models.

From this perspective (which is the perspective we choose to assume in this book), a business model can be seen as a simplified and clear representation of an organisation’s critical activities. By analysing its business model, an organisation can assess which activities are critical for creating and capturing value, and can thus also maintain competitive advantages. Put more simply, the organisation imagines the extent to which a certain business will be financially successful and thus viable. The business model describes those parts of the organisation that are necessary to generate products and identifies important supplier, customer, and market conditions. It is also important to remember that business models are dynamic, as relevant events within and outside the organisation constantly need to be evaluated and reflected.

3.2. The Different Parts of a Business Model

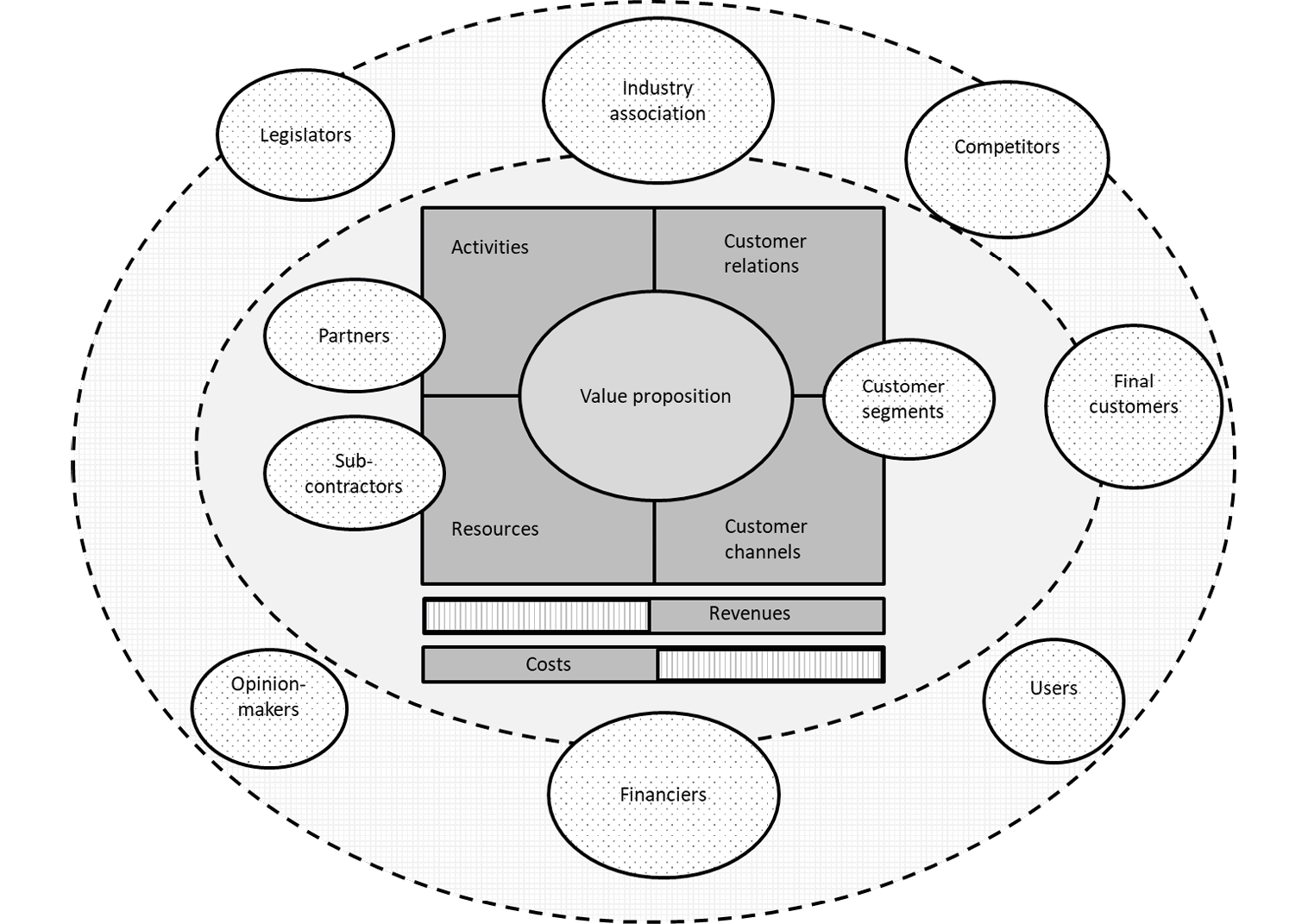

What are the different parts of a business model? Since there is no uniform definition of the business model concept, descriptions of its components will also vary. Figure 3.2 shows those components that are most often included in descriptions of business models.

Figure 3.2. The components of a business model and possible actors within the business ecology of which the organisation is a part.

The organisation is represented by a square with four fields and the dashed circles are the business ecology of which the organisation is a part. “Business ecology” is a metaphor for the outside world or market in which the organisation operates. Business ecologies accommodate a number of actors. Some are foreground actors with whom the organisation interacts directly, such as customers, partners and suppliers, reducing joints (those inside the inner circle). Others are considered background actors; that is, they affect the organisation’s ecology, but the organisation does not interact directly with them, e.g., legislators, opinion makers, and final customers. Some background actors may periodically become foreground actors, as represented in Figure 3.2 by financiers, industry associations, and final customers (the end customers of a chain of linked business activities). The concept of business ecology is used for an organisation’s external analysis because it is a dynamic system. Over time (as in a real ecosystem) some actors may have a reduced significance or disappear completely, while others will grow in importance and affect the organisation and the ecology to a higher degree. Some background actors (even at a distance from the organisation) may come to wield considerable influence over its business, for example by serving as role models. We will not delve further into the business ecology concept here, but will return to it in Chapter 11.

In the middle of Figure 3.2 we see what constitutes the very essence of the business model: the value proposition. An organisation carries out certain activities and has certain resources so as to arrive at a value proposition. These activities and resources may be more or less dependent on partners and subcontractors. Another part of the business model is the customers, who are categorised and divided into different customer segments. Relationships with customers are determined by this categorisation, and an important purpose of customer relations is to help understand customer needs and communicate the value proposition.

At the bottom of the figure are a revenue and a cost stack. The darker part of the bars mark where the main business model revenues and costs are often generated. The largest revenue streams normally come from sales to customers, but can also arise if the organisation is part of an offer from one of its partners. Similarly, in production-heavy organisations, most of the costs come from the activities and resources needed to realise a particular value proposition, but some costs arise in customer relationships and customer channels, and in some organisations, these are even the dominating costs. In the following section, we will take a closer look at each part of the business model and discuss how they are affected by digitisation. We start with the value offering.

3.3. Business Model Digitisation

3.3.1. Value Proposition

Simply put, one can say that a value proposition is the value that can be associated with a particular product. (A product could be something physical, a service or a combination of physical goods and services.) In the business model, value does not simply mean monetary value, even if there is ultimately a price on a product. Instead, the value as expressed in the business model addresses how a product satisfies a customer need. It is also important that the value proposition reflects the strategies an organisation has chosen via their goals to realise, and that the strategies themselves contribute to the realisation of the value proposition.

For some products, it is pretty obvious at first glance what the value proposition is, but if you think about it, there are often several dimensions to associate with it. Take, for example, the value of foods such as cheese, cereals, and bread (and even those which are lactose-free, gluten-free, or made from alternative ingredients). Their obvious value is that they are fuel for our bodies because they provide us with energy and vital building blocks for muscle, bone, and more. If the value is obvious, however, then why do food producers and grocery stores bother to design packaging and advertise their products? They do so largely because they want customers to choose their products over those of their competitors. Here, the value proposition is crucial. How it is defined—and communicated—makes a difference. Food is much more than fuel, it is also enjoyment, community, and cultural expression (why else would holiday meals involve special dishes?). This type of analysis can be applied to most products, so a value proposition needs to undergo a thorough analysis before it can be formulated and communicated.

For example, consider the car as a product. A common value of all cars is that they enable us to transport ourselves from Point A to Point B. This is such a basic and expected value, however, that car manufacturers do not promote it in communications regarding why we should choose their car. Instead, they emphasise other tangible or intangible features, such as safety, speed, reliability, and accessibility, as well as more subtle qualities, such as a sense of exclusivity (you can become part of a small, select crowd of happy owners) and/or wisdom (you are a sensible driver).

IT and digitisation have a major impact on value propositions. The carmaker is a good example. The safety systems in a car are in part purely physical, such as bodywork and brake discs. But just as the design and production of a car’s security systems are accomplished through IT, the systems themselves are also controlled largely by digital technology. Sensors that perceive a risk of collision can activate automatic braking and if a crash occurs, then a digitally controlled belt tensioner and airbags are activated to relieve its effects (security). Similarly, a car’s digital systems contribute to more efficient fuel injection (acceleration and speed as part of the driving experience) and the optimal utilisation of drive systems (operational safety, performance, and accessibility). Digitisation contributes in a crucial way to enabling the value proposition of modern cars.

The digitisation of business models also adds another dimension: value propositions these days tend to have a greater service content. For the car manufacturer, this could be digital navigation systems (GPS) or the fact that a mobile phone wirelessly connects to the car’s audio system and is controlled through a few keystrokes on the steering wheel. GPS features can also be used to enable traceability as part of theft protection, or so that in the event of a collision, a signal to an alarm centre is triggered automatically. When abroad, a help desk function can assist with the remote entry of destinations into the navigation system. Within the not-too-distant future, the sound system may be controlled by eye movements via a head-up display accessed through a pair of glasses included in the car’s equipment.

When 6G data communication technology and the Internet of Things are fully operational, they will enable us to consume the car as a service, and the majority of us may rent or lease a vehicle instead of owning it. The price model, and how we pay for the service, can then be differentiated according to vehicle data (speed, mileage, braking wear and other aspects of driving style, climatic conditions, etc.) that is communicated to the service provider. Someone who drives without care will have to pay for it, but for someone who applies eco-driving, the cost will be significantly lower. We could all be part of a carpool, where self-driving, electric vehicles can be ordered via an app for collection at any address within a certain geographic area. This, in turn, would require substantial development of the value proposition, along with the digital, physical, and organisational systems that would enable it.

3.3.2. Partners, Subcontractors, Activities, and Resources

The left side of the business model (Figure 3.2) contains the parts that are necessary when creating a product to which a certain value is attached. Partners and suppliers do not always have to be separate roles, and can be the same actor. The difference between the roles is the way in which the organisation interacts with the actor. It is not relevant to include all subcontractors that sell to us, because in its business model, an organisation should identify the subcontractors whose products are necessary to create the value proposition. A partner may sell something to us as well as being more involved in the business model activities and thus becoming an important part of the resources. Partnerships can take different forms, such as strategic alliances with non-competitors, partnerships with competitors, joint ventures, and so on. The difference between subcontractors and partners is also that a supplier can be replaced relatively easily, while the relationship with a partner is more long-term and extensive, and involves more mutual adaptation.

For the car manufacturer, the manufacturer of seats or airbags is an important subcontractor. Without these products, there is no car and thus no value proposition. However, if the products are relatively standardised, then the subcontractor can be changed, for example, to reduce purchasing costs. A car manufacturer, on the other hand, could be in a strategic long-term alliance with a consultant specialising in software development for controlling car engines. This requires in-depth knowledge of different car models, with the consultant being involved at a fairly early stage of the research and development phase.

The organisation’s activities create a value proposition. It is also common to consider the activities as parts of a process: that is, within the organisation there is a network of activities that have a definite start and end, and their combination in the process creates customer value. The activities are intimately associated with the resources, and without the resources there are no activities. Resources can be physical, intangible, human, or financial. As well as partners and suppliers, the business model should highlight the activities and resources necessary to achieve the value proposition. The delimitation of activities can be quite difficult to achieve, depending on the complexity of the product.

Digitisation clearly affects the activities of the business model. When a car manufacturer purchases car parts such as seats and airbags, it is important that they are delivered at the same rate as the cars in which they are mounted. One of many ways to reduce the cost of resources is to have as little stock as possible, which is usually referred to as just-in-time production. To schedule deliveries with production, an enterprise resource planning system (ERP) at the car manufacturer can keep track of stock levels through radio frequency identification (RFID) tags, barcodes, and similar digital reading techniques. When they reach a certain critical point, an automatic order is made to their subcontractors. More proactively, the orders will be based on the actual production plan. If the subcontractor is also a partner, it is probably connected and logged into the ERP system, which enables it to access the necessary information and take both long-term and current plans and deviations into account. This type of seamless information flow between the subcontractors and manufacturers within manufacturing is also known as Industry 4.0. Here too, 6G technology and the development of the Internet of Things play an important role, as they enable every product in the production chain to carry with it information about where to go and how. The goal is a production chain with shorter conversion and lead times, fewer errors, greater flexibility, and less time-consuming programming.

It is not only cooperation in production processes that is affected, however. Digitisation also enables brand-new collaborative relationships. For example, millions of camera-equipped cars on the roads, which will give drivers support, can also be used to provide information about road conditions to those responsible for road maintenance on an ongoing basis. GPS data can, in aggregate, provide up-to-date images of traffic flow that enable better control of rush-hour traffic in metropolitan regions.

For our example, the car manufacturer, all internal activities to achieve a value proposition are dependent on resources in the form of various IT solutions. Design is achieved using computer-aided design (CAD). The testing of bodies, braking systems, motors, and so on, is conducted with the support of digital technology: first simulations, and then, in physical tests, different types of sensors collect measurement data for evaluation. Similarly, computer-controlled industrial robots have long been an important part of production, where they ensure quality and maintain time-efficient production. People are, in the car industry as well as in other industries, still an important resource for providing a value proposition, but they increasingly interact with IT in performing their roles.

3.3.3. Customers, Customer Relations, and Customer Channels

At the far right of the business model (Figure 3.2) we find the customers, to whom the value proposition is aimed. They are rarely a homogeneous mass and therefore can usefully be categorised. One might divide them into customer groups or customer segments, such as age- or lifestyle-related categories, or according to how the customer consumes the value proposition. Car manufacturers usually categorise private customers based on lifestyle, i.e., according to whether they are families with children or young adults without children. “Urban and successful” is a common customer category, as is “adventurous”. Willingness and ability to pay should also be assessed in customer segmentation.

Customer relationships and customer channels, as well as activities and resources, are intimately associated with each other. Relationships can be developed in various media, such as by direct contact, websites, or news email—perhaps even through member club discounts. Here, digitisation can enable orchestrated use of multiple channels, a so-called omnichannel approach. Digital channels typically provide organisations with data on their customers’ behaviour. Systematic analysis of all available data on customers can allow organisations to better tailor customer offerings. An omnichannel approach provides coordinated communication with customers across channels, which fruitfully combines the various characteristics of the available channels, rather than using multiple channels in parallel. Customer channels are the means through which the value proposition is conveyed to customers, which in turn affects customer relationships. Traditionally, the dealer is an important partner for the car manufacturer, as it is on their premises that many final customer relationships arise, and through them that the car is delivered to the customer. It is through the dealer’s brand workshops that a car manufacturer’s original spare parts are sold with high profit margins.

Car dealers are an example of a business model that is not necessarily represented by a single organisation. Many car dealers are independent organisations who, through an agreement with the car manufacturer, have the right to convey the car manufacturer’s deals. In a way, therefore, the reseller becomes a customer, because they buy the car from the manufacturer. At the same time, it is a partner, because good dealers are an important resource that benefits from long-term collaboration. The car manufacturer’s value proposition is not primarily formulated for the dealer, but for the final customer, that is, the car buyer. Of course, there is a proposition from car manufacturers to dealers and vice versa—why else would they do business with each other?—but central to the car manufacturer’s business model is the value proposition for the car customer. This is an example of how an actor (the car dealer) can have multiple roles within a business model. This may indicate that the actor is of special strategic importance to the organisation.

Digitisation also affects customer relationships and channels. We found above that these are often divided into groups or segments. Such grouping/segmentation does not depend directly on IT; however, digital technology can be a great support for analysing lifestyle patterns. To achieve such an analysis, you often need to combine several extensive data sources, which is known as big data analysis. In our car example, big data analysis requires access to data and skills that the car manufacturer may be lacking but that some other partner may have.

IT can enable an organisation to manage customer relationships via several media. As we mentioned above, the customers of dealers who meet on-site in a car showroom are probably meeting in the most important customer channel for the traditional car manufacturer. Before the customer decides to visit, they will most certainly have sought out information about different car models. The websites of the car manufacturer and dealer, via price comparison sites and discussion groups on social media, allow potential customers to find documentation on equipment packages, properties, prices, and price models (e.g., buy or private lease). Both the car manufacturer and the dealer should therefore determine which digital channels they can affect either directly (their own websites) or indirectly (e.g., where do they appear in Internet search engines?)

There are also several examples of how digitisation enables new methods of meeting customers. Customer databases are important for creating additional sales, for example, through regular emails or post about service and upgrades to the car system. Car sensors refine the opportunities for additional, situationally tailored sales announcements, and instrument and communication systems in the cars enable new ways to present such offers. Tesla, the electric-car manufacturer, offers the consumer cars directly from the car manufacturer. Not having an existing dealership relation to cultivate and protect, and not seeing any existing dealers with extensive knowledge of the type of offering Tesla provides, their decision to break with the dealership tradition is less complicated than it would be for an established car brand.

Both car manufacturers and dealers can personalise customer relationships to a greater extent with the help of all embedded IT. This is already happening in the sales of commercial vehicles. Data legislation and/or customer reactions might prevent it (owing to privacy issues), but digital technology makes it possible. If the car, as we pointed out above when describing the value proposition, is connected to the Internet of Things, then data on mileage and driving patterns (acceleration, braking, speeds, and more) are regularly transferred to a database held by the manufacturer. This data is then sorted and analysed based on the fact that each car has a digital unique identity in the database. This means, for example, that service intervals can be adjusted to actual driving style and to the climate the car has mainly been used in, rather than simply to distance or time. The provision of customised preventive maintenance is well within reach. Furthermore, companies can communicate with the driver of the car and deliver weekly or monthly reports about how their driving affects the car and tips about how their driving style can be developed to tax the car less (although this may not be appreciated by all drivers).

3.3.4. Revenues and Costs

When a customer buys a product (the value proposition), an income is generated. The summary of incomes that refers to a certain period of time becomes the revenue for that period. The same applies to costs, which are the same period’s summary of the monetary value of resource consumption. Only the expenses that have been used (directly or indirectly) to produce the value proposition are counted. For a car manufacturer, some of the purchases may have ended up in a warehouse and therefore should not be counted as a cost for the period. Some have been investments that will last for a long time, and then, only the part “consumed” in the present period counts as cost for that period. This accounting-based information on costs and revenues can be found in an organisation’s financial statement. It provides us with some financial information, but an analysis of the business model can assist with complementary perspectives on what actually creates the financial information. The bulk of the business model’s revenue is generated by sales (the dark grey part of the revenue stack in Figure 3.2). How the revenue streams look depends on the type of product and the price model, that is, on how the agreed price is tied to what is delivered, including the rights and responsibilities for delivery. In addition to the price model, the size of the revenue is also affected by sales volume and price. As pointed out at the beginning of the chapter, revenue may also arise on the left-hand side of the business model figure. The partners from whom an organisation buys products contribute as resources enabling a value proposition, and may in turn have a sale where the organisation assists with resources for them. In that case, they can choose to define an actor as both/either a partner (cost source) and/or customer (revenue source). This choice depends on how the business model contributes to a comprehensive representation of the organisation’s activities.

In the business model, costs arise when purchasing products from subcontractors and partners (the dark grey part of the cost stack in Figure 3.2). In addition, there are activities and resources that are cost drivers, and (often substantial) costs also arise when customer relationships and customer channels are maintained. The business model clearly shows that costs should be regarded not only as a burden on the organisation, which can easily be concluded if only an income statement is considered, but also as an enabler for value creation; the costs arise because the organisation purchases and uses services and other resources to create the value proposition. That is not to say that an organisation should not strive to reduce its costs and use existing resources more efficiently (as successfully done by the HR manager in the previous chapter’s example. Different calculation models are of great help to support analyses of how to reduce costs and improve efficiency.

Digitisation has a major impact on business model costs. For example, the direct costs of production tend to decrease continuously as IT enables more efficient processes, including extensive automation and standardisation. Costs for many other activities and resources tend instead to increase. Research and development in the automotive industry, as in other industries, draws increasingly higher costs. Here, IT can play a role in increasing or decreasing costs, as the technology enables more extensive analyses and tests of the complex digital systems found in today’s cars. This can, on the one hand, encourage more testing, increasing testing costs. On the other hand, testing via simulation can be cost-efficient and time-saving compared with physical testing, thus helping reduce testing costs.

It is more difficult to assess how digitisation affects revenue. This depends, among other things, on the fact that some IT is considered infrastructural. This means that it is a prerequisite, such as websites and certain IT systems embedded in cars. Without it, an organisation has no value proposition to convey and thus no revenue whatsoever. Digitisation that can affect revenue tends to make the value proposition different from that of an organisation’s competitors. It enables product development that provides a competitive advantage. This can in turn be a combination of different digital techniques, such as the security system we mentioned earlier, or a product with expanded digital service content that makes the car “feel” right, or, as in one of the examples above, new pricing models that change the value proposition and the revenue streams. However, the IT aspect of digitisation is typically easier to copy than the organisational aspect, so advantages based mainly on hardware or software will probably be short-lived; if they are indeed appreciated and profitable, other organisations will soon start offering the same or something similar. A competitive advantage thus rests on the ability to keep improving faster than one’s competitors.

The above examples of how digitisation can affect different parts of a business model apply to many industries and organisations whose business models are derived from a more analogue time, but today there are also examples of business models that originated in the digital age and are thus the result of digitisation. In the next section, we will therefore discuss the characteristics of these digital business models.

3.4. Digital Business Models

As more and more individuals have access to various digital communication platforms (desktop, laptop, tablet, and smartphone), business models that are entirely based on digital information flows have emerged. Without IT, they would not exist in their current form.

3.4.1. The Roots of Digital Innovations

Products offered and delivered by digital business models are not rare, nor are they new or unique. On the contrary, they are often the next step (or leap!) in a long-term development based on the emergence of a number of innovations over time, refined and brought together. In other words, the roots of digital innovators often extend far back in time. Take, for example, the gadget that you probably spend most of your time with—the mobile phone. Its origins can be traced back to the nineteenth century, and the then-up-and-coming electric telegraph. Techniques for communicating over longer distances when telegraphs were emerging included optical signal systems in the form of semaphores, or physical devices in the form of human dispatch riders and pigeons. The revelation that electrical impulses travelled at very high speed and that with the help of a binary code (the Morse Alphabet) and Telegraph Keys (Switch) a person could transmit data between two interconnected units over large geographical distances, revolutionised the way to communicate. The technology that enabled electric telegraphy was the platform for the next innovation in the late-nineteenth century, the telephone. The telephone dominated person-to-person communication at a distance in the twentieth century, but it was still wired. The capacities of wired systems gradually increased, thanks in part to innovations such as automatic switches.

In parallel with wired communication technology, the first steps toward wireless communication were taken. Innovations like the use of electromagnetic waves enabled the development of radio transmissions for one-way communication, often broadcast, and for communication between two units, for example via so-called “radio comms”. However, it took until the mid-1980s before the mobile phone, a combination of the innovations of the telephone and radio, was launched on the consumer market. At the time this market was quite small (among other things because the phones weighed about 3.5 kilos, had limited capacity and cost in current monetary value about ten times more than a standard smartphone does today) and the telephones were used to make voice calls. The mobile phone innovation developed rapidly in parallel with wireless technologies for data transmission and communication via the Internet. The most obvious leap for mobile phones was to smartphones, where the big breakthrough was Apple’s iPhone, which in 2007 was the first to successfully rely entirely on touch-screen technology, with fingers used as pointing devices (although touch screens of different types had then been around as user interfaces on different devices for over forty years). This brings us up to today, and to the emergence and growth of digital business models. We will now categorise and give examples of some of these business models.

3.4.2. Digital Intermediaries and Network Builders

As we noted above, few, if any, digital business models are entirely new. What causes them to emerge and be successful is that they either develop existing, or create entirely new, value propositions. Metaphorically, what these value offerings have in common is their character as bridging joints.

3.4.2.1. Bridging Joints

A passenger riding on an older train can, at some passages, feel the joints in the rails as they are crossed. They are there as a result of a great number of rails that have been linked together over a long distance, and that allow the passenger to move from location A to B. In older wagons and on older tracks the joints feel very distinct, but they are rarely felt in a high-speed train that is running on continuous welded rails built solely for purpose. Similarities may be drawn between innovations that are joined together in order to move us from Demand A, through Supply B, to the final station, gratification. A common denominator for digital business models is that they exist because they help to reduce, and sometimes make almost invisible, the ‘joints’ in a customer’s trip. Let us clarify by studying the example of business models which make music available as their value proposition. These business models are characterised over time by reducing ‘joints’ in terms of both availability and time.

Listening to music was, for a long time (until the late 1970s and early 1980s), mostly a stationary experience, as the listener had to be in a certain place, where a record player or a tape recorder was available: availability was very limited. Cassette tapes and portable cassette players enabled music consumption to become more portable and thus increased accessibility. Listening was also individualised, as listeners were able to choose which songs a cassette tape would contain by recording a so-called “mixtape”. This analogue technology to some extent reduced the joints in the value offering, however, they remained in place because they represented the three separate business models involved in making the music portable: the record label (which offered the predefined products LP disc and pre-recorded cassette tapes), the manufacturers of recordable cassette tapes, and the manufacturers of portable cassette players. This made it necessary to spend a great deal of time in order to put together a music selection that was adapted to your own tastes.

Music consumption started becoming digitised with the introduction of the compact disc (CD), but joints remained, in the form of availability and time, although they decreased somewhat in scope. There were still three actors involved, however: music publishers, the producers of recordable CDs, and the manufacturers of portable CD players. The next digital innovation that further reduced the joints was the mp3 format and the mp3 player. Portable CD players disappeared and were replaced by mp3 players with a completely different capacity to store music, and accessibility increased with the ability to create an individual playlist on a simple laptop computer.

The joint of time remained, however, although it decreased slightly. In order to create playlists and download music to the mp3 player, one had to copy music from CDs to a playback program on a computer (for example, Windows Media Player), which could take considerable time. Another option was to use Internet-based sites that made music available. At first, sharing sites and so-called pirate sites (illegal downloads) appeared, but eventually, niche commercial services, such as iTunes, also emerged. The ability to download music from the web further reduced the joints, as supply and accessibility vastly improved. Music still needed to be downloaded to a computer before it could be transferred to the particular platform—the mp3 player—which made it portable, however, and this was something that still took some time.

When smartphones were successfully introduced in 2007, the need for mp3 players gradually disappeared, because the music player was now on the phone. In combination with the improved ability to transmit data over the Internet (4G communication technology was being introduced), opportunities were created to both increase accessibility and reduce download time (streaming), to organise and listen. Spotify identified this opportunity as a music intermediary, and that is central to its value proposition. Today, the joints of availability and time are, thanks to Internet-based music intermediary services and smartphones, by and large non-existent. Certainly, there are still three vendors involved—the music service, the Internet operator, and the telephone provider—but in such a way that the tripartite structure is not a problem for listeners. Today, we can listen to what we want, when we want, without delay, and without being tied to a dedicated music or audio platform. Another important contribution in this context is the fact that from the music consumer’s perspective, the physical borders between the actors, music publishers, and platform-makers that previously needed to be overcome, are largely non-existent. This is very different from the conditions during the era of the vinyl LP disc and cassette-tape recorder.

One way of further identifying what characterises digital business models is to divide them into categories. Examples of two such categories might be intermediaries and network builders (see Table 3.1). In the text that follows, these categories are illustrated through examples of companies that are not unique in themselves; instead, they have been selected because they can be seen as representatives of digital business models in various industries.

Table 3.1 Examples of companies and industries where digital business models in the form of mediators or network builders are represented.

|

Mediators |

Network builders |

||

|

Company |

Industry |

Company |

Industry |

|

Spotify |

Music |

|

Communication/Entertainment |

|

Uber |

Transportation |

YouTube |

Entertainment |

|

Zalando |

Commerce |

Crowdfunding |

Finance |

3.4.2.2. Mediators

Digital business models are based on bringing together individuals in need of a particular product and the suppliers of the product in question. Brokers are found in many industries and existed long before society was digitised, but they were also more geographically limited. Record labels, record stores, records in a department store, and mail-order vendors are all examples of music mediators.

Thanks to their digital brokerage service, companies like Spotify can design a business model that differs from these earlier intermediaries on several key points. In the section above, we described changes in the value proposition achieved by Spotify. Even customer segments are changing because Spotify is not geographically limited, except by intellectual-property-rights restrictions, and can offer a range that appeals to many categories of music consumers. Customer relationships change when their offers are personalised and the customer channel is completely digital. Revenue streams come via advertising revenues and fixed subscription fees, which allows, among other things, a more even flow of payments. The service they offer also means that their agreements with music publisher partners differ from the business models of traditional music intermediaries. For Spotify and its direct competitors, the ability to offer (close to) the world’s supply of music is of central importance. Instead of a narrow selection of music, the norm is now that users should be able to find anything in the catalogue. As a result, the activities and resources of the business model differ substantially from previous music intermediaries. Skilled programmers and proprietary software are now key resources that cannot be easily replaced. Without them, there would be no Spotify.

Uber is an example of a transport service that links customers in need of transport with drivers who are interested in earning an income. This has also previously existed (and still does) in the form of taxi companies with a telephone exchange. What is new in Uber’s digital business model is that if the availability of vacant cars increases, then consequently the time it takes to get hold of one decreases—at least in a metropolitan region. The service also develops the value proposition by simplifying payment (deducted from a registered credit card) and makes the connection between driver and rider safer, since both can see each other’s rating before closing the deal. The customer knows what the trip will cost, roughly, and where cars are available before the order is completed. This creates added value for the customer, in the transparency of availability and cost, and possibly in the knowledge that the cab will accept the prearranged mode of payment. Uber offers fast, flexible, safe, and accessible transport. New conditions are thus created because there are new customer segments. Customers that may have been hesitant about hailing a regular taxi directly from the street can now use Uber’s services. As in the case of Spotify, customer relations are also altered. To become a customer, people have to register, and as a result, their orders are entered into a database, enabling Uber to analyse their travel patterns over time (and thus also convey more customised offers) and the aggregate travel patterns in real-time, to help direct cars to where customers are or can be expected to appear. The customer-channel aspect of the business model is concentrated on one channel, the app. Anyone who wants to join as a driver is a partner, which is reminiscent of how some taxi companies are organised. Uber cooperates fully with individuals, however, while some taxi companies collaborate with taxi owners, who in turn hire drivers. There are relatively few resources and activities required by the business model, but these are nevertheless absolutely crucial for operations. Without the software to mediate the service, and developers to optimise it, there would be no Uber.

Zalando is in many ways a traditional mail-order merchant in clothes and accessories, but its business model is mainly digital. The business is based on digital interfaces that offer products from other companies, and they do not produce or offer any product of their own. They therefore associate with a large number of suppliers and partners, and Zalando’s internal activities and digital resources are focused on optimising customer offers. Unlike the two examples above, however, Zalando’s business model also relies on physical resources, such as their central warehouses where goods are stored whilst awaiting transportation to customers. No matter what size and what brand, Zalando wants to be able to pass it on to the customer. They also compete on price by partnering with price comparison sites. This develops the value proposition as it increases accessibility and reduces the time required by a customer to find an item, and it may also enable the customer to buy it at a lower price. Like the other service providers, Zalando’s digital business model enables them to build knowledge of their customers, and thereby develop relationships with them on a seemingly individual basis. There are many customer segments, and the customer channel is largely Internet-based, although physical delivery—and returns—are also important.

Accessibility is fundamental to the value propositions of smaller, focused e-retailers who, unlike Zalando, specialise in one or a few products. No matter where a customer is located, they can (as long as there is Internet access, they have a functioning communication platform, and—for physical goods—can take delivery of shipments), find exactly what they are looking for and have it delivered, even if the retailer is currently on the other side of the planet.

3.4.2.3. Network Builders

The common denominator for business models in the category of network builders is that they provide a platform for individuals with common interests. Network builders existed even before society was digitised, and different types of associations attest to that, but just like the mediator category in Table 3.1, network builders were often more geographically limited. Digitisation has significantly changed the way we communicate. Businesses like Facebook have developed value propositions that increase accessibility to various people and decrease the time it takes to build different types of networks. Table 3.1 shows that they belong to the communications industry, but they are just as much a platform for entertainment, because, for example, they allow links to many different channels to be shared. Their customer segments are both individuals and businesses. For smaller organisations, Facebook may be an alternative to creating a full website. Facebook pages can be used to advertise opening hours, special offers, or whatever is relevant at the time. There could be pictures showing a daily offering, or new products that are now available for purchase. For more established organisations, which already have a website, Facebook can serve as a more dynamic channel of communication: news and offers will be pushed to followers, opinion polls can be implemented, and customers and other stakeholders can comment, ask questions, and receive answers. All of this can be achieved with a website and email account, too, but in Facebook, it is handled through standard functionality and through the customs of using the application that have developed in society. In addition, the network structure of Facebook can facilitate the spread of news and opinions regarding a company and its offerings, for better or worse. Again, digitisation as a catalyst can help fuel the spread of both appreciative and negative comments and opinions.

It is not organisations that make up the majority of Facebook users. The largest customer segment comprises individuals with their own Facebook accounts (and for many, probably also accounts on other social media) where they can share their opinions, positive and negative. Today’s widespread use of smartphones also means that people effectively always have access to various communication channels—not just when sitting in front of a computer. Smartphones have also enabled so-called geotagging, which can highlight preferences and opinions based on geographical location. A very important resource for Facebook’s business model is therefore the availability of the large volumes of data that are continuously generated. This data can be analysed to offer paying customers access to targeted advertising channels. It is characteristic of network-builder business models that many actors tend to appear in different parts. The customer who posts information, the core of the value proposition, is at the same time a partner and a key resource. The value of network platforms therefore grows when the number of active users increases. Analyses of this type of digital business model therefore tend to become multidimensional. How do we meet a customer’s (an individual’s or a company’s) need for a communication platform and at the same time make them available for other businesses advertising? It is a delicate balance for companies like Facebook not to overuse and blend its data in ways that users find unethical or provoking, because without users, a network platform like Facebook has zero value.

The same conditions apply to more purely entertainment-oriented networks such as YouTube. It is a channel for both entertainment (for example, a whole line of music videos with the band that meant a lot to you when you grew up) and fact-finding (for example, how best to drill into concrete walls to put up a shelf). The content is entirely user-generated—it is not YouTube that creates and posts the content—and the customer segment is wide. It is possible to talk of companies and individuals here as well, but discussion can be even more nuanced. There are certain individuals who just consume content, and those who consume and also produce it. The latter become important partners and resources, as they are the ones who create and contribute to the value proposition. If no one uploaded films to YouTube, there would be no content available, and thus no value generated.

Unlike previous examples in this section, there are so far within crowdfunding no equally dominant players. Briefly, crowdfunding is a platform for financing services. The value proposition here comprises an offer of access to a marketplace for ideas that need funding. The idea can be described in text, image, and/or video, and the financial contributions can be secured in both directions. If, by the closing date, the pledged contributions total at least the amount required by the idea holder, the contributors will be charged via payment intermediaries connected to the platform, and the sum that has been promised is, after deduction of the platform’s commission, transferred to the idea holder. The expectation is then that the idea holder realises the idea and, if this has been promised, distributes the product that the financiers have funded. If the requested sum is not reached, then no prospective financiers are charged, and no one will expect the idea to be realised. The value proposition also contains additional dimensions for those seeking funding. The crowdfunding platform works as a form of market research “for real”. Previously, anyone wondering about the viability of an idea had to rely on their own or others’ judgment, or just ask people directly whether they would be interested in a product, and if so at what price. The problem with that approach is that judgments are uncertain, and statements of willingness to pay are in no way binding.

Just as in the other examples of digital business models, crowdfunding companies are not linear, and do not have clear supplier and customer roles. They offer a brokerage service (for a fee, which is usually a percentage of the funds raised). Anyone who wants financing buys exposure to conceivable financiers and those who are willing to finance fun ideas or sell products that have not yet been developed have an opportunity. But which of them are really the customers, and who is the supplier in the deal? In some respects, both sides are crowdfunding platform customers, and in some ways, they are subcontractors of the service that the crowdfunding platform offers.

3.4.3. Some Common Denominators for Digital Business Models

We chose to highlight six examples in the section above, but of course there are many more out there, as well as additional dimensions of the impact of digitisation on business models. Our categorisation and our examples may be seen as narrow. Companies like Spotify, Uber, and Zalando also share network-building features, and the Facebook, YouTube and crowdfunding services are also mediators of information and financial resources. Such definitions depend on the perspective taken, and our starting point in the examples above was how the organisation is primarily seen.

An important point of our categorisation, connected to the examples of industries, is showing that digital business models generally belong to a traditional industry that has been around for a long time. With their digital business models, however, the above examples have clearly come to influence their respective industries in different ways. Spotify has changed the way we consume music, Uber our view of what a taxi service is, and Zalando has set a standard of accessibility that is difficult for many retailers to live up to. Facebook has largely removed the geographical boundaries of social networks. YouTube has had a particular impact on younger consumers, with many people foreseeing the death of traditional linear television, and with it a number of today’s dominant media companies who may soon no longer receive sufficient advertising revenue. Crowdfunding opens doors to private financing that few have otherwise been granted.

Regardless of the category of digital business model, there are still some basic common denominators worth mentioning. These have arisen because they significantly affect the experience of customers/consumers in their apprehension of time and availability. They also, unlike our initial car manufacturer example, have a non-linear character. This means, among other things, that an actor affects several different parts of the business model by being a customer at the same time as being a supplier, and participating in activities that create the value proposition itself.

3.5. Chapter Summary

This chapter introduced the business model concept and its relation to an organisation’s goals and strategies. With that as a starting point, we offered examples of how digitisation affects existing business models, from the content of the value proposition to partners, activities and resources. We illustrated the possibilities for new customer segmentation and development of customer relationships and customer channels, as well as how this affects revenue streams and cost structures.

We also discussed digital business models, which have emerged thanks to the ongoing digitisation of society. These have some common features, including the fact that they help to reduce the ‘joints’ of life through increased ease of access to products by reducing the time spent on accessing them. They can also be understood as mediators of products and/or as network builders.

The first three chapters of this book show that, regardless of the business, digital technologies often play a crucial role. However, it is important to remember that digitisation does not automatically contribute to creating competitive advantages. Some are of a purely infrastructural nature; an organisation sometimes has to choose to digitise, adopting the infrastructure of existing standards, if it wants to continue to exist at all (as in the banking example in Chapter 2). That kind of IT utilisation can hardly be considered a strategic asset (although the lack of it would be a strategic liability). Not adopting commonly used infrastructure will typically become a strategic obstacle. Then there is digitisation as central to developing existing, or creating entirely new, value propositions. That type of digitisation can be of great strategic importance. Companies like Spotify, Uber, and YouTube have become large and successful with business models for which digitisation is absolutely crucial to the value proposition.

It is important to remember that the two roles played by digitisation—digitised infrastructure and digitisation as a central part of the value proposition—are not permanent. Digitisation that is today considered infrastructural was often central to a new value proposition when it was initially introduced. Existing digital infrastructure can, if combined in new ways and/or with new technology, gain increased strategic importance. Organising is ongoing. This means that the organisation’s business models and the influence of digitisation on them constantly need to be evaluated. Digitisation per se has no intrinsic value; only if it actually generates value does it attain great and sometimes decisive importance. A question that arises in connection with this is: How can we work to detect new opportunities to develop the value proposition through digitisation, and how can we then act to realise them? In the next chapter of this book, we consider this question. We start by discussing organising, how organisations can divide and coordinate work tasks and decision-making when digitising, either within a single organisation or between organisations. Which organisational roles are important for capturing and realising the potential of digitisation? Which role-holders are allowed to have an input in decisions, and who makes the decisions? Which competencies are important for understanding the role of digitisation in a business and how can these competencies be secured? How can different people’s experiences and competencies come together in a fruitful way, avoiding conflict, in organisational work on digitisation? We address these issues as we move into Chapter 4.

3.6. Reading Tips

There are three articles that define and categorise what distinguishes the business model concept:

- DaSilva, Carlos M. and Trkman, Peter (2014). Business model: What it is and what it is not. Long Range Planning 47 (6), pp. 379–389, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.004.

- Massa, Lorenzo; Tucci, Christopher L. and Afuah, Allan (2017). A critical assessment of business model research. Academy of Management Annals 11 (1), pp. 73–104, https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2014.0072.

- Wirtz, Bernd W.; Pistoia, Adriano; Ullrich, Sebastian and Göttel, Vincent (2015). Business models: Origin, development and future research. Long Range Planning 49 (1), pp. 36–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2015.04.001.

The business model canvas is a concept for understanding and identifying the different elements of a business model, and has received a lot of attention. Its authors have published two manuals for those who wish to identify and visualise business model content:

- Osterwalder, Alexander and Pigneur, Yves (2012). Business Model Generation: A Guide for Visionaries, Pioneers and Challengers. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Osterwalder, Alexander; Pigneur, Yves and Bernarda, Gregory (2014). Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want. New Jersey: Wiley.

An important part of both strategic development and the operationalisation of the business model is to identify how customers should pay and how the organisation should charge for their products. The following articles and book discuss the concepts of business ecology, business model and price model, and how they relate to each other.

- Cöster, Mathias; Iveroth, Einar; Olve, Nils-Göran; Petri, Carl-Johan and Westelius, Alf (2019). Conceptualising innovative price models: The RITE framework. Baltic Journal of Management 14 (4), pp. 540–558, https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-06-2018-0216.

- Cöster, Mathias; Iveroth, Einar; Olve, Nils-Göran; Petri, Carl-Johan and Westelius, Alf (2020). Strategic and Innovative Pricing: Price Models for a Digital Economy. New York: Routledge, https://doi-org.ezproxy.its.uu.se/10.4324/9780429053696.

- Iveroth, Einar; Westelius, Alf; Olve, Nils-Göran; Petri, Carl-Johan and Cöster, Mathias (2013). How to differentiate by price: Proposal for a five-dimensional model. European Management Journal 31(2), pp. 109–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2012.06.007.

As noted, IT can have various functions in developing a value proposition. A rough but classic distinction is that between IT’s streamlining function and IT’s function for contributing new insights about the business, such as customer preferences and profitability. An in-depth look at these two features is available in Shoshana Zuboff’s well-quoted 1988 book. A shorter overview is given in her 1985 article.

- Zuboff, Shoshana (1988). In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power. New York: Basic Books.

- Zuboff, Shoshana (1985). Automate/lnformate: The two faces of intelligent Technology. Organisational Dynamics 14 (2), pp. 5–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(85)90033-6.

The term “crowdsourcing” is said to have been coined by Jeff Howe in a number of articles and blog posts from 2006. An overview is given in this article.

- Howe, Jeff (2006). The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired 14 (06), http://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/.

Innovation and product development are common areas for crowdsourcing. This article provides a good overview of those areas and the challenges they can bring.

- Majchrzak, Ann and Malhotra, Arvind (2013). Towards an information systems perspective and research agenda on crowdsourcing for innovation. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 22 (4), pp. 257–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2013.07.004.