5. Structured Decisions and Decision Processes

© 2023 Mathias Cöster et al., CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0350.05

So far we have seen how important it is to have adequate business models and business strategies in an organisation. The point is to orient organisations towards concrete targets and to have well-deliberated strategies to drive them towards their goals.

Central components include the decisions that must be made, which are to be aligned with plans and objectives. However, decisions are unfortunately often handled far too frivolously and many organisations believe that it is enough to introduce strict regulatory structures that are somewhat harmonised with the business models in order to achieve an adequate organisational setup, or to try to realise the strategy work in some kind of intuitive sense, which usually leads to underperformance. Instead, well-founded decision-making, where the various priorities are clearly defined, is an important component in achieving quality in strategy work and goal fulfilment.

The value of good decision-making in an organisation cannot be underestimated. Not taking decision-making seriously can become expensive, and there are lots of activities that must be considered. Firstly, it is important to clarify the context, that is, the preparations for the decisions and the organisational decision-making structures since decisions are always made in a context. Secondly, it is important to have appropriate methods and tools for compiling and evaluating the information and to understand the existing strategies and their advantages and disadvantages based on established targets. Thirdly, there should preferably exist an overall decision-making process. In summary, to achieve good decision-making, we must have a proper decision-making structure, access to adequate models and methods, and a process for managing our decision-making in the organisation.

The decision structure may look different depending on the conditions and the nature of the business. Informal decision-making needs to be identified and clarified. Likewise, responsibilities and power relations must be made clear, which helps to reduce conflicts and dissatisfaction that can easily result otherwise. The necessary models and methods also depend on the nature of the business, but one important component of the decision-making is about collecting and interpreting facts and deciding what is relevant and what is not. This creates a decision basis to which some deliberated method can then be applied for the actual decision evaluation. However, it seldom helps to stare at an Excel spreadsheet if you really want to get a picture of the possibilities and options. We will return to this later.

One of the most important things is thus that the organisation has a proper decision-making process. Here, we often see large but unnecessary shortcomings; we often underestimate the real complexity of compiling a decision basis and the decision situation when enforcing the decision. An efficient, coordinated process is needed to manage decisions. This applies both to the organisation’s various parts and to the organisation as a whole. This may seem difficult, especially where experience is lacking. At least at an abstract level, however, this is quite straightforward.

First, you determine who will do what in upcoming work, then what you want to achieve (the target), and thereafter you identify the strategies that can possibly realise this target. This means that you formulate the process and identify partial decisions, the strategy and its properties, and the criteria on the basis of which you will assess the strategy. The criteria and priorities should, of course, express the objectives of the business. Furthermore, you must analyse the properties of possible outcomes and other variables as well as how they might affect the result. Thereafter, you can evaluate the decision.

The overall decision-making process is not necessarily a linear process. Sometimes, we have to go back and forth as roles change, new people enter the process, unexpected information pops up, implementation becomes difficult, compromises become necessary, groups oppose one another, and so on. We simply have to be open to changing circumstances and the need to adjust. Models only represent aspects of reality and yet they are the basis for our analyses.

The components of decision-making are basically as follows. First, the roles should be determined. Thereafter, a rough analysis of the problem must be carried out. After that, opportunities for improvement of the business should be examined, and those requiring closer examination should be identified. It is important to reconcile the results of this examination with the overall goals of the business. Then comes the detailed decision-making process. When the process is completed, it must be documented and, where applicable, presented to the decision-makers, and sometimes to larger sections of the organisation. As with all thorough processes, the process should be evaluated in order to assess what could be improved in subsequent strategy work.

After the above, the actual implementation of the selected alternative commences. This step sometimes also contains decision-making processes, especially when the decisions mean radical changes. Decisions should be firm and timetables should be kept. Many new issues may arise when it comes to major decisions. The process description that we will go through here works well for decisions that will occur during the implementation phase. The decision-making process also requires a clear structure. Employees who feel involved in decisions will perform better, thereby avoiding many conflicts.

5.1. Rough Analysis and Improvement Potential

The first phase is a review of how decisions of relevance are made in the organisation. Then one must look to understand what can be improved. During this rough analysis, the following questions should be posed.

- What is the decision basis? How does the collection of information take place? Is there anything of relevance documented by previous decision-making processes?

- How do the strategies relate to the organisation’s goals and how are the overall objectives affected?

- Which sub-decisions are involved in the decision? What types of decision should be made during the various decision-making processes? Only long-term strategic ones? Or quick ones? Are all relevant criteria covered by the different decision types?

- Which decisions are repetitive? Which components of the strategy can be used in future decisions? Can parts of the information be reused, and if so, which parts and when?

- Which methods are used today? Are there elements that make these methods structured? Or do most things just happen?

- Who makes strategic decisions? Is it primarily the CEO, management group, board, or IT manager? Or are there other decision-makers who make important decisions affecting the business as a whole and impacting the strategy?

- Is there a documented process for implementing the strategy? Which decision components should be employed? Which informal processes can be formalised?

- What are the experiences and outcomes of previous decisions? How do the organisational structure and delegations look? What are the responsibilities and reporting paths?

- Are there adequate information systems and other information management processes?

- Are there well-specified quality assurance and rules of procedures for different staff categories as well as for the board and management groups?

- Who should be in the groups that will be involved in the different phases of the project, and how should they be involved?

The final point is very important for the result of the decision-making process. Developing well-composed groups that are anchored in the business will have a major impact on the decision quality and implementation. It is also fundamental that multiple end users are involved. A well-composed group of active and interested members who feel involved and have representative views is integral to the analysis.

Finally, the conditions for structured processes and the potential for improvement are examined during the strategy work. Often, there is much to be done to address risk analyses, transparency, dependence on individuals, and how fact-based the decisions usually are.

In the analysis of the improvement potential, the following questions should be posed.

- Is there enough potential for implementing and introducing a structured process at all, or is significant preparatory work required? What should be included in the analysis? What boundaries should be defined?

- How can we learn from different experiences in the organisation?

- Who is perceived as beneficial to the organisation?

- What are the qualitative and quantitative goals of the organisation?

- What are the risks and conditions of managing new strategies that appear during the process?

- Are all of the above sufficiently documented?

After the rough analysis, a more formalised decision-making process should be carried out. It is normally advisable to start with a few select decision problems that are particularly important to the organisation.

5.2. The Decision Process

A decision-making process should constitute a complete process of data collection, investigation, analysis, and recommendation. It may look different, but a common one would look as follows:

- Identification of the decision problem (or problems), so one knows what to do

- Structuring the problem so that the decision components and their relationships are clearly visible

- Information collection resulting in a detailed information basis

- Modelling the problem around the information basis

- Evaluation of the model whereby existing information is aggregated and analysed

- If necessary, feedback on and repetition of previous steps

- Creation of a decision basis consisting of instructions and recommendations

5.2.1. Identification and Structuring

It is surprising how often the identification of the problem itself is missing, even though it is central to reasonably tackling the decision problems. In this step, we must clarify the purpose of the decision, what it should include, and what it should omit. The problem can often be seen from several perspectives, and assigning values to different strategies thus depends on the perspectives from which they are considered. The perspectives are represented by various criteria. All of this should be documented in a project specification based on the rough analysis outlined above.

The structuring of an actual decision problem involves specifying the relevant criteria and possible strategies for obtaining a more precise problem formulation to support the collection of information. After this, one should have a rough summary of the criteria based on the specified objectives and a list of the strategies that are considered feasible along with descriptions of what they mean at different levels.

To make the discussion more concrete, we will consider an example of how an organisation might develop an efficient and secure physical IT infrastructure with high transmission capacity nationwide, granting people easy access to interactive public e-services.

After the process described above, the most important criteria are believed to be security, efficiency, availability, and transmission capacity (throughput). There are also three main strategies: i) to outsource the entire development and operation, ii) to develop the necessary services in-house as needed, and iii) to develop more qualified services in-house and outsource simpler services.

Financial aspects are generally central to both the investment itself and the continuation of the operation. Personnel satisfaction and development, as well as changes to work tasks, are further perspectives to consider. We will soon proceed with this example, but first we must explain how to model the information involved.

5.2.2. Information Capture and Modelling

During this phase, precise criteria are developed and ranked, and the strategies are specified. The criteria must be prioritised. This is usually achieved through the assignment of weights indicating importance to each, but the criteria could also simply be ranked. Thereafter, the consequences of the different strategies are analysed and valued. Finally, scenarios are analysed and the probabilities of different strategy consequences are estimated.

There are several difficulties at play here. The first time one gathers information, it is often difficult to find out what is really required for the analysis, that is, to correctly model the relevant criteria, priorities, and possible strategies with consequences as well as utility values and weights.

Further complications usually appear when trying to estimate the probabilities of the different scenarios. Furthermore, there are often preferences that may conflict with each other, such as maximising the quality and at the same time obtaining a high financial return on investment. Such goal conflicts lead us to make some trade-offs between our goals.

There are thus often contradictions. For example, the strategy with the best economic forecast might entail issues with the work environment. Often, one strategy is the most suitable for the short-term profitability of the operation and another is most suitable for accessibility. In this case, which strategy should be chosen? One way of managing the choice would be to evaluate all strategies solely on the basis of the most important criterion, but this approach ignores the information that other perspectives provide. Taking all perspectives into account can yield somewhat absurd effects, such as one strategy being merely slightly better than another from an economic perspective, but obviously worse from a quality perspective.

In order to progress in the analysis, we must prioritise how different criteria relate to each other and express this so that it can be calculated. This can be achieved by assigning significance weights to the criteria that express their relative importance. The greater the weight, the more important the criterion. Then we can assess the strategies based on the criteria by aggregating everything in an evaluation. This approach, whereby criteria are weighted or ranked according to importance, is called a multi-criteria analysis. We also usually study the effects of any uncertainty in the background information in order to assess the reliability of the solutions.

Some of the prerequisites for successful decision-making are thus a real ability to describe the strategies and also a clear sense of how well they fulfil the different criteria. We also need to understand how important the different criteria are in relation to the operational goals. There are better and worse methods for doing so. We will begin by considering a kind of base case, in which criteria weights and strategy values are numbered precisely.

The range of values assigned to strategies can differ depending on the situation. A scale from 1 to 5, for example, where 1 indicates that a strategy has a very poor rating under that criterion and 5 indicates that it has a very high rating, is not uncommon. We then obtain weighted values for the strategies where the values under the criteria are weighted with the criteria weights. The weights must be greater than or equal to zero and the sum of all weights must add up to 100%.

Suppose that in our e-service example above we consider that safety is more important than efficiency, which in turn is more important than accessibility, which is more important than transmission capacity. In order to carry out the analysis, we must formulate this more concretely. Let us specify our criteria preferences on a scale from 0% to 100%, to reflect how important the different criteria are. This is of course impossible to do precisely and reasonably, but let us pretend for the sake of argument that it is actually possible. The importance of:

- Security is 40% (0.4)

- Efficiency is 30% (0.3)

- Availability is 20% (0.2)

- Transmission capacity is 10% (0.1)

The strategies under the criteria are valued in terms of utility (i.e., how “good” they are), represented as numbers. A common method of valuing strategies is, as in Table 5.1, for the lowest possible utility for each criterion to be 0 and the highest 5. Intermediate strategies allow for utility values between 0 and 5. Note that the full utility scale range [0, 5] need not be occupied.

Table 5.1. Development of an e-service structure – valuation of strategies.

|

Strategy |

Security |

Efficiency |

Availability |

Transmission capacity |

|

Outsource the entire development and operation |

1 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

In-house development of the necessary services as required |

4 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

|

In-house development of more qualified services and outsourcing of less qualified |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5.2.3. Evaluation

The values of the strategies under the criteria are then weighted together. If plainly unreasonable strategies have already been sifted out, then a fairly simple and well-established method is to weigh together criteria and values using the following formula:

V(A1) = w1 · v11 + w2 · v12 + w3 · v13.

Here, wj is the importance of criterion j, and vij is the utility value for strategy Ai under criterion j. We then look at which strategy is the most suitable by calculating the weighted values for all strategies:

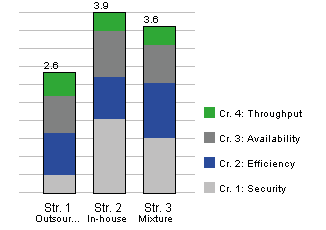

V(Outsource) = 0.4 · 1 + 0.3 · 3 + 0.2 · 4 + 0.1 · 5 = 2.6

V(In-house) = 0.4 · 4 + 0.3 · 3 + 0.2 · 5 + 0.1 · 4 = 3.9

V(Mixture) = 0.4 · 3 + 0.3 · 4 + 0.2 · 4 + 0.1 · 4 = 3.6

We select the option with the highest weighted mean value, which is the strategy of developing the necessary services in-house as requirements arise. See Figure 5.1 which also shows the contribution of each criterion to the total value of each strategy.

Figure 5.1. Values of strategies using one level of criteria.

Note that it is in reality in most cases very difficult, if not impossible, to produce precise weights and values for the strategies. Instead of expressing utilities or weights as precise numbers, we can instead work with comparisons and intervals. This is especially important when handling qualitative criteria such as those we have discussed here. Even without the requirement for precise values, people often find it difficult to express their preferences and therefore use different methods. Sometimes the criteria are compared to a so-called reference criterion, such as cost, and the decision-maker works out which trade-offs he or she is willing to make on that basis. For example, a cost reduction of EUR 10,000 can be perceived as having as much worth as a certain reduction in quality. Needless to say, this requires that everything is measured on well-defined scales with well-defined units.

Good decision support can be obtained by visualising the differences in weights and values through different graphic tools. Surprisingly, it is often sufficient to use quite inexact weightings with interval weights (or rankings) in order to distinguish between strategies. But again, one needs computer support to calculate the results. We will describe this more closely when discussing procurement (which is actually a type of multi-criteria analysis).

5.2.4. Refinement of the Decision Basis

Once we have obtained a result, we may find that we need more information or that we want to expand the analysis for other reasons. For example, we often need to give a more detailed description of the problem by building so-called criteria hierarchies with additional sub-criteria. This is to further facilitate assessing the goal fulfilment of different strategies. In this way, we can often better capture the structure of the decision problem. Criteria hierarchies are applicable when there may be sub-criteria to some or all of the criteria.

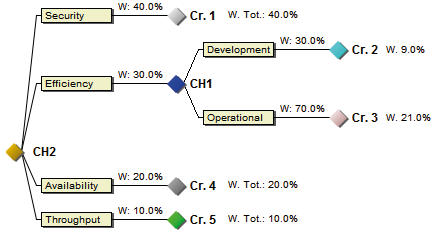

In the example of e-service structure development, we can, for instance, partition the main criterion efficiency into the sub-criteria development efficiency and operational efficiency. In this way, the assessment is facilitated, as the analysis becomes more detailed and we might more easily understand what the criteria entail. When we have sub-criteria in this way, it is usually helpful to model the problem in a tree format as in Figure 5.2. There is no important computational difference, and the calculations essentially look the same, but the trees give a little more visual structure to the problems. In the figure, we have also added weight indications for the two sub-criteria.

Figure 5.2. A criteria hierarchy – an example of iteration in the decision process.

We now assume that development efficiency has a weight of 30% (0.3) and operational efficiency a weight of 70% (0.7), and that the values for the respective strategies are as shown in the table below.

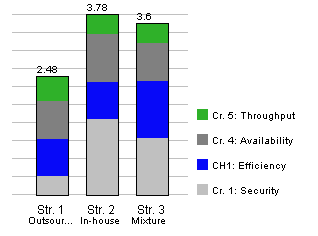

We then, again, use weighted averages to obtain the values of the strategies. See Figure 5.3:

V(Outsource) = 0.4 · 1 + 0.3 · (0.3 · 4 + 0.7 · 2) + 0.2 · 4 + 0.1 · 5 = 2.48

V(In-house) = 0.4 · 4 + 0.3 · (0.3 · 4 + 0.7 · 2) + 0.2 · 5 + 0.1 · 4 = 3.78

V(Mixture) = 0.4 · 3 + 0.3 · (0.3 · 4 + 0.7 · 4) + 0.2 · 4 + 0.1 · 4 = 3.6

Figure 5.3. Value of strategies using sub-criteria.

When we consider ourselves finished with the analyses, we compile them into a structured decision basis.

Table 5.2. The values of the strategies under the sub-criteria.

|

Strategy |

Development efficiency |

Operational efficiency |

|

Outsourcing of the entire development and operation |

4 |

2 |

|

In-house development of the necessary services as needed |

4 |

2 |

|

In-house development of more qualified services and outsourcing of less advanced ones |

4 |

4 |

5.3. Extensions of the Analysis

Once we have come this far, it is possible to deepen the analysis further. Multi-criteria analyses are in this context a good tool for gaining a clearer picture of the decision situation, but do not normally reflect the fact that there is often a great deal of uncertainty involved. When working with risk analyses, which try to assess the probability of various threat scenarios, we must perform more detailed analyses and also estimate the probabilities of the different scenarios, as well as assess how the different consequences of the strategies will affect the situation. We must also work out how to value these consequences in order to get a clearer picture of the characteristics of the possible strategies. The components of a more detailed decision formulation are as follows:

- Criteria weighting, which specifies how important the criteria are in relation to the desired goals. We have explained this above.

- Event description, which specifies the possible events or scenarios and the probability of the occurrence of each. As mentioned, this is particularly important in risk analyses, since we are normally very interested in the likelihood of negative consequences.

- We must also understand the consequences of the different strategies and events and how they are to be valued considering the goals.

During the evaluation phase, we analyse the strategies by, for example, maximising their expected utilities. Sensitivity analysis is often used to investigate robustness (remember that this is the stability of the result considering information changes) and to highlight information that should be clarified or re-evaluated. The evaluation results in a preference scheme for strategies, a risk analysis, a stability analysis, and a specification of any additional information required for the decision. The result is an updated picture of the situation with clearer and more reliable information.

The result of the evaluation forms the basis for the decision, along with other documentation from the decision process and well-founded and well-motivated recommendations regarding development and implementation.

5.4. Chapter Summary

A large part of the total work time in organisations is spent gathering, processing, and compiling information in the light of a set of business goals. The purpose is usually to create a basis for making organisational decisions. Much is gained if the decisions—or at least the important ones—are made in a rational and not intentionally biased manner, and if the decision-maker takes all relevant available information and all reasonable possibilities into account. Unfortunately, this is not usually how it works. People often make decisions on the basis of unclear reasoning, and this chapter has thus provided an introduction to how professional decision-making and quality-assured decision-making processes in companies and authorities should work.

In the next two chapters, we will review and expand on various aspects of decision-making. We will show how decision-making can be applied to procurement processes. Procurements consume a lot of resources every year. Risk management and scenario analyses are also important parts of any organisation’s activities. To act sensibly, we need to understand the possible outcomes and form an opinion on the probability of their occurrence.