Afterword

©2024 F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0357.07

“No book is more conspicuous in Walt Whitman’s ‘long foreground’ than the King James Bible”

— Gay Wilson Allen, Reader’s Guide to Walt Whitman (1970)

In the preceding pages I have endeavored, through “careful investigation” and “massing of evidence,”1 to reveal the fact of Walt Whitman’s stylistic debt to the King James Bible and the nature and extent of this debt—G. W. Allen’s estimation that the KJB is one of the “more conspicuous” books in Whitman’s “long foreground” is not an exaggeration.2 My focus throughout has been on the immediate run-up to the 1855 Leaves and the general period of the first three editions of Whitman’s remarkable book. The intent has been to press the idea that the KJB’s influence was consequential for many of the leading elements of Whitman’s mature style—his long lines, unmetered rhythm, parallelism, parataxis, non-narrativity, preference for the periphrastic of-genitive. The style of the later period shifts dramatically in many respects. The lengths of Whitman’s lines and poems atrophy, punctuation and page layout become more conventional, and some aspects of his 1850s poetic theory become relaxed, e.g., some of those “stock ‘poetical’ touches” once robustly eschewed appear with commonality. A full accounting of Whitman’s stylistic debt to the KJB would need to consider the poetry (and other writings) of the later period. I gesture here to this fuller accounting to come with a reading of Whitman’s late poem, “Death’s Valley.”3

* * *

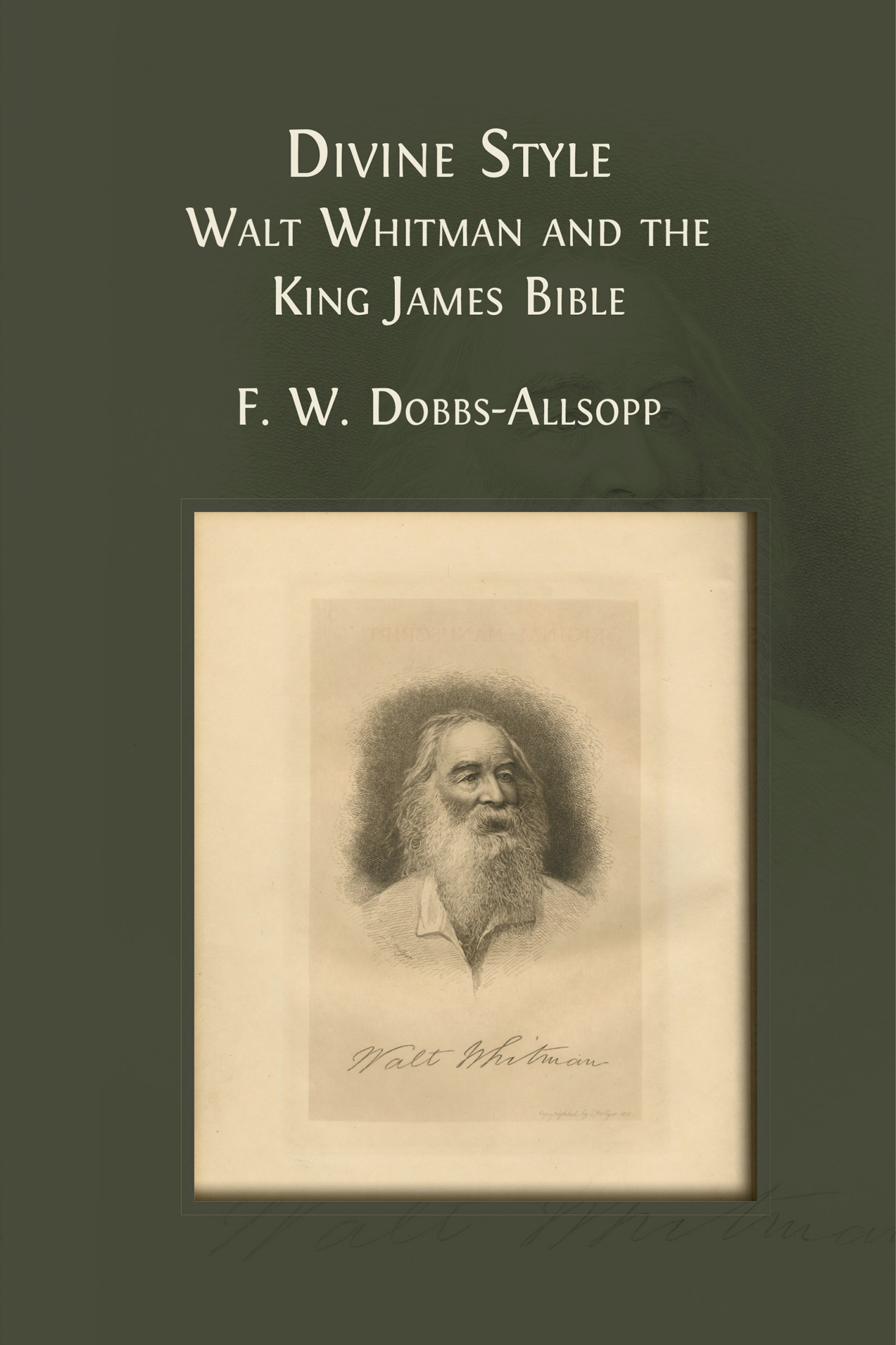

On 28 August 1889, H. M. Alden, editor of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, wrote Whitman to request a poem to accompany an engraving of a painting by George Inness entitled “The Valley of the Shadow of Death”4 (1867; see Fig. 49). Alden had “enclosed a proof” of the engraving for Whitman’s use.5 Whitman responded quickly with the requested poem by the next day’s mail. 6 He asked for and received (“in a couple of days”)7 a $25 honorarium. However, Harper’s did not publish the poem until a month after Whitman’s death.8 Although “Death’s Valley” was not the last poem Whitman composed, its posthumous publication and biblically inspired provocation make the poem an especially appropriate subject for my own after-word.

Fig. 49: “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (1867) by George Inness. Image courtesy of the Francis Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, http://emuseum.vassar.edu/objects/59/the-valley-of-the-shadow-of-death.

The poem is in the first place a response to Inness’s painting, which is as Alden requested: “on the chance that it may meet some spontaneous current of poetic movement in you… let the movement have its course & let us have the result.”9 The parenthetical comment just under the title—“(To accompany a picture; by request”)—makes Whitman’s ekphrastic ambition explicit. The opening (four-line) stanza is an apostrophe to the unnamed Inness (addressed only as “Thou,” “thy,” “thee”):

NAY, do not dream, designer dark,

Thou hast portray’d or hit thy theme entire:

I, hoverer of late by this dark valley, by its confines, having glimpses of it,

Here enter lists with thee, claiming my right to make a symbol too.

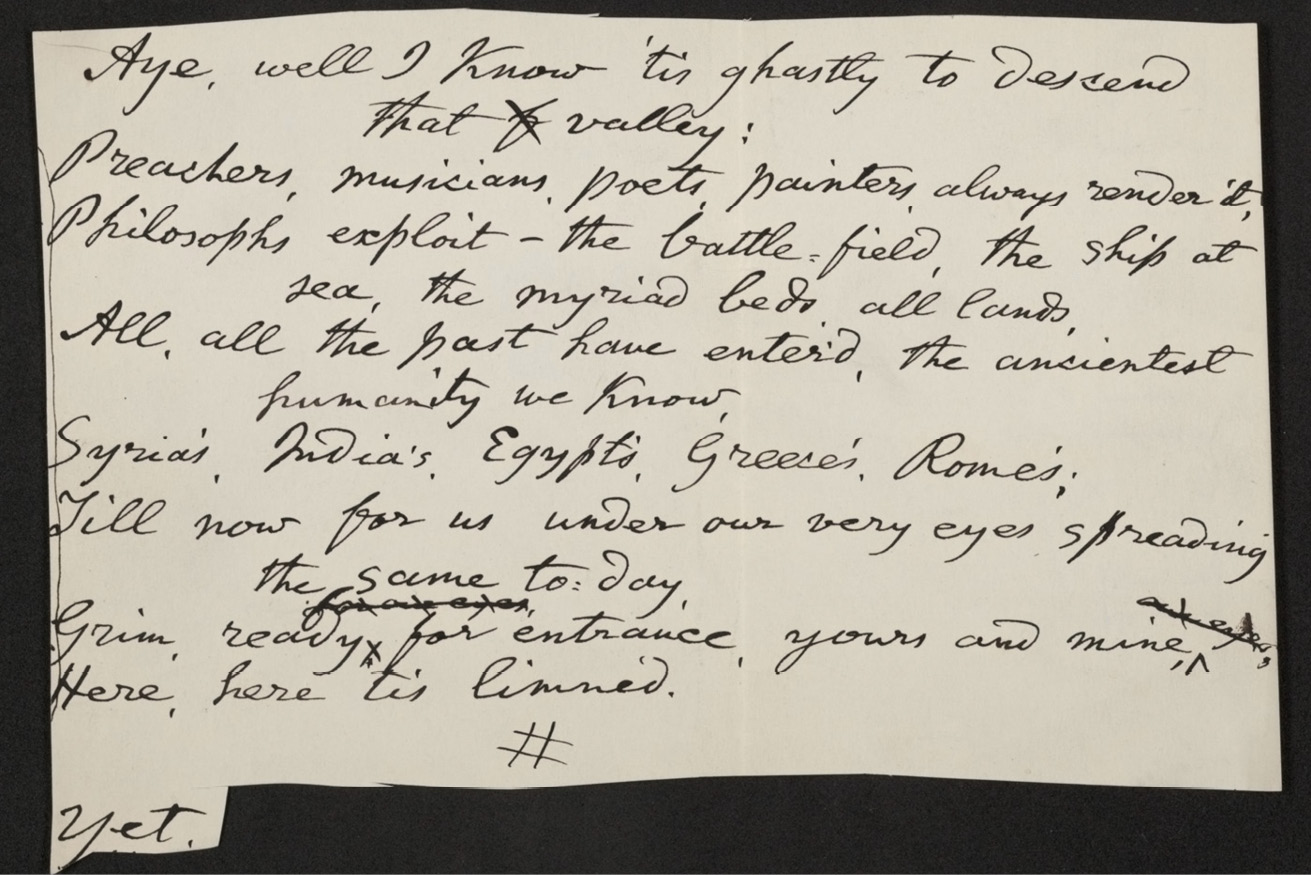

The painting, too, is obliquely referenced here—the “dark” of the designer’s creation (line 1), that which is “portray’d” (line 2), “this dark valley” (line 3), and the other “symbol” implied by Whitman’s avowal “to make a symbol too” (line 4). Later in the poem—the second (lines 5–11) and third (lines 12–20) stanzas are given over mostly to the making of Whitman’s competing “scene” and “song” (line 13) of Death—the half-line “Nor gloom’s ravines, nor bleak, nor dark” (line 14) likely takes its initial cue from the dark, rocky crags that loom forbiddingly on either side of the valley depicted in Inness’s painting. The darkness of Inness’s color palette in this canvas leaves a lasting impression on viewers. The painting is also plainly in view in the poem’s original opening lines that Whitman eventually rejected (after working through several drafts)—“Just as I was folding it up, the thought struck me that I was not satisfied with it—with that part and so I cut it off the sheet—let it start with the other—sent the mutilated piece”:10

Aye, well I know ’tis ghastly to descend that f valley:

Preachers, musicians, poets, painters, always render it,

Philosophs exploit—the battle-field, the ship at sea, the myriad beds, all lands,

All, all the past have enter’d, the ancientest humanity we know,

Syria’s, India’s, Egypt’s, Greece’s, Rome’s;

Till now for us under our very eyes spreading the same to-day,

Grim, ready for our eyes, for entrance, yours and mine, our eyes,

Here, here ‘tis limned.

#

Yet11

Here Whitman is already intent on bending the painting’s theme, alluded to in “…that f valley:/… Grim” (lines 1, 7), to his own “current of poetic movement”—here literalizing the metaphoric valley as the passageway from life to death and asserting the long history of death as a part of human existence, “all the past have enter’d.” His glance at the painting itself is most explicit in the final line, “Here, here ‘tis limned.” The primary meaning of “limn,” according to Webster’s American Dictionary, is “to draw or paint; or to paint in water-colors.”12 The deictic “here” references the extratextual “picture” the poem accompanies. Confirmation of this construal is the apostrophe to the painter that followed immediately before Whitman “cut wholly out” the first “third” of the original poem. In fact, the connection was more explicit as what became the poem’s opening line (“NAY, do not dream, designer dark”) originally started with “Yet,” which was precisely “cut… off the sheet” (se Fig. 50).

Fig. 50: “Aye, well I know ’tis ghastly to descend.” Image courtesy of the Walt Whitman Papers in the Charles E. Feinberg Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. mss18630, box 26; reel 16, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1863000626

However, “limned” also can have transferred and figurative meanings, including to describe or depict in words, a usage that the OED dates back to the seventeenth century (meaning 3b). Therefore, Whitman’s limning “Here, here” may be intentionally doubled, pointing to Inness’s painting and also to his own “symbol” made of words—“And out of these and thee,/ I make a scene, a song, brief” (“Death’s Valley,” lines 12–13). He uses “limn” with this transferred sense in both “As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free”13 (1872)14 and “Had I the choice”15 (1885). The latter poem is especially revealing because it intentionally plays on the word’s base meaning, viz. “To limn their portraits, stately, beautiful, and emulate at will” (line 2) and its extended sense—the “portraits” here in view are of the “greatest bards” (Homer, Shakespeare, Tennyson) and their verbal art, “Metre or wit the best, or choice conceit to wield in perfect rhyme, delight of singers” (line 5). The speaker would “gladly barter” these poetic marvels would one wave of the sea “its trick to me transfer,/ Or breathe one breath of yours upon my verse” (lines 7–8).16 In “Death’s Valley” Whitman’s “mutilated” limning in words is poised to do battle with Inness’s visual art (“enter lists with thee,” line 4). The “Here” that heads line 4 unmistakably points to Whitman’s own poem.

The published version of “Death’s Valley” consists of three stanzas, each organized sententially. The lines are irregular, ranging between four and eighteen words in length, with two of the shortest lines opening (“NAY, do not dream, designer dark,” six words) and closing (“Sweet, peaceful, welcome Death,” four words) the poem, forming a lineal envelope. The poem itself is “brief” (line 13)— “not a long job.”17 The small scale of the three stanzas emphasizes the syntactic connectedness of the lines, sometimes lending them an enjambed feel that contrasts with the closed feel of so many of Whitman’s early end-stopped lines apportioned in long catalogues. Lines 3–4 are emblematic. The subject “I” heads line 3 and is qualified by a short series of appositional phrases (“by this dark valley, by its confines, having glimpses of it”). Line 4 completes the incomplete clause: “I…/ Here enter lists with thee.” The longer second stanza (seven lines), where the speaker tallies his own experiences of death, with its receptions (“have seen” [2x], “have watch’d,” “and seen”), lineal apposition (lines 8–9), three line-initial “And”s (lines 7, 9–10; cf. lines 12, 17), some interlinear parallelism (e.g., lines 7–9; cf. lines 13–15), and even an occasional internally parallel line (e.g., “And I have watch’ d the death-hours of the old; and seen the infant die,” line 7; cf. line 18), gestures back to the style of the younger Whitman. And yet at the same time, all seems somehow “mutilated,” to use Whitman’s word for his foreshortened poem. The punctuation is conventional throughout. And Whitman has relaxed his earlier proscription of stock poetic elements, which flood this poem: “NAY” (line 1), “Thou” (line 2), “thy” (line 2), “thee” (lines 4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 18 [2x]), “hast” (line 2), elided spelling of past tense verbs (“portry’d,” line 2; “watch’d,” line 7; “call’d,” line 19), and inverted syntax (e.g., “theme entire,” line 2; “a song, brief,” line 13).18

Though provoked initially by Inness’s painting, the psalm that inspired the painting is also in view for Whitman from the start.19 The second line of the discarded opening stanza—“Preachers… always render it”—makes apparent that the biblical source of “that f valley” is as significant for Whitman as is Inness’s painterly rendering of it. The speaker’s doubled confession “not fear of thee” (line 13) and “for I do not fear thee” (line 14) is inspired directly from the language of Inness’s theme verse, Ps 23:4: “I will fear no evil; for thou art with me.” The cadence of the phrase “for I do not fear thee” mimes (and chimes with) the psalm’s “for thou art with me.”20 And the line “Of the broad blessed light and perfect air, with meadows, rippling tides, and trees and flowers and grass” (line 16) is a Whitmanian elaboration of the psalm’s familiar images of “green pastures” and “still waters” (v. 2)—nothing in Inness’s painting answers to this beatific outburst exalting the “Rich, florid… life” (line 19) of mortal existence; hence Whitman’s initial “NAY” (capitalized for emphasis). Other striking biblicisms are noticeable, e.g., “breathed my every breath” (line 10) reprises (and repurposes) Tyndale’s famous cognate coinage (not present in the Hebrew) from the second creation story, “and brethed into his face the breath of lyfe” (Gen 2:7; cf. Ezek 37:9); the capitalized references to “God’s” (line 17) and “Heaven” (line 18), signaling their biblical lineage; the well balanced, internally parallel line, “Thee, holiest minister of Heaven—thee, envoy, usherer, guide at last of all” (line 18), with matching biblical “thee”s and of-genitives (“minister of Heaven”// “guide… of all”).

In the end, however, Whitman turns both painting and psalm on their proverbial heads. The psalm is a confession of trust in Yahweh, the “thou” directly addressed in vv. 4–5, and the painting Inness’s Swedenborgian gloss on the Christian pilgrim’s dependence on the light of “faith alone”—symbolized above all by the cross given in “place of the moon” and the dark valley’s blue hues, the color of faith (for Inness).21 The palliative consolation for the harsh reality of mortal existence implicit in the cross cum moon and the dark tonalities in which Inness colors the pilgrim’s journey (on earth) in the shadow of death were contrary (in emphasis) to Whitman’s own ideas about death—“Nor gloom’s ravines, nor bleak, nor dark…,/ Nor celebrate the struggle, or contortion, or hard-tied knot” (lines 14–15).22 Whitman’s dissatisfaction with the opening stanza eventually discarded was perhaps because he realized he had already conceded too much to Inness’s vision, viz. “well I know ‘tis ghastly…/ Grim” (lines 1, 7). The change from “Yet” to “NAY” emphasizes Whitman’s resolve to “make… a song” welcoming of death. Therefore, in contrast to Psalm 23 and Inness’s painting, Whitman fixes on death itself, long a favored theme.23 Death only comes into the psalm, and through the psalm into the painting, through that most enchanting of the KJB’s mistranslations, “the valley of the shadow of death.” The Hebrew is gêʾ ṣalmāwet, an adnominal genitival construction (see Chapter Five) consisting of “valley” (+ of) + “darkness.” The second Hebrew noun (ṣalmāwet) signifies “an impenetrable gloom, pitch, darkness,”24 but early on was provided with something of a folk etymology, decomposing the term as if it were a compound of ṣēl “shadow” and māwet “death” (Septuagint: skias thanatou; cf. Job 38:17). Whitman’s title, “Death’s Valley,” deftly thematizes the focus of his poem. By first abbreviating the biblical phrase that Inness takes for his title, and then choosing to render the genitival relation with the apostrophe + “s” construction instead of the biblical English phrasing with an of-genitive,25 the valley in question—that which “preachers, musicians, poets, painters, always render”—ceases to be a mere metaphor (a “dark valley”) for danger and becomes the very place of Death’s abode, a place to which “‘tis ghastly to descend.” The change-up from the biblical English genitive formation also allows Whitman to enclose his poem within an inclusio, “Death’s” (first word of the title)// “Death” (last word of the poem)—Death literally has the first and last word. And as this inclusio encloses the lineal envelope of short opening and closing lines (lines 1, 20), Whitman fashions for his poetic “scene” a frame not unlike that which he imagined framed Inness’s picture but made up entirely of words—a most literal ekphrasis.

And, importantly, Death, like the old Canaanite god Mot himself, is personified—the owner of the valley—addressed directly (“O Death,” line 10), countering the psalm’s opening, “The LORD is my shepherd” (v. 1). God has been demoted, all but kicked out of Whitman’s poem—not unlike “Lucifer” in Isa 14:12—present only vestigially as another way of naming Death: “God’s beautiful eternal right hand,/ Thee, holiest minister of Heaven….” “Thou” and “thy” of Psalm 23 are used to address Yahweh (vv. 4–5), whereas these archaic pronouns solicit in Whitman’s “song” a counterpointing use of “thee” to address Death after line 10:

And I myself for long, O Death, have breathed my every breath

Amid the nearness and the silent thought of thee.

And out of these and thee,

I make a scene, a song, brief (not fear of thee,

Nor gloom’s ravines, nor bleak, nor dark—for I do not fear thee,

Nor celebrate the struggle, or contortion, or hard-tied knot),

Of the broad blessed light and perfect air, with meadows, rippling tides, and trees and flowers and grass,

And the low hum of living breeze—and in the midst God’s beautiful eternal right hand,

Thee, holiest minister of Heaven—thee, envoy, usherer, guide at last of all,

Rich, florid, loosener of the stricture-knot call’d life,

Sweet, peaceful, welcome Death.

The line-ending “thee”s in lines 11–14 help tie the second and third stanzas together and set up the hymnic crescendo at poem’s end, beginning with the internally parallel line 18 and ending by bidding “welcome” to “Death” (line 20). Within the poem these accepting “thee”s as they chime and punctuate the latter stanzas counter the disparate second person forms used in the opening, disapproving apostrophe of the painter. And it is not just the God of Psalm 23 who personified Death preempts but also the Christ symbolized in Inness’s moon-like cross. Death is glossed as “God’s beautiful eternal right hand” (line 1), usurping the place the New Testament reserves for the risen Christ (Mark 16:19; Luke 22:69; Acts 2:33; 5:31; 7:55, 56; Rom 8:34; Col 3:1; Heb 10:12; 12:2; 1 Pet 3:22), whom in “Blood-Money” Whitman calls “the beautiful God, Jesus.”26 Whitman’s habit of reading against the biblical grain is evident here again, as it was throughout his life.

Where Whitman reads with the psalm (and against Inness) is in his tone. His is a joy-filled song. Taking his cue from the buoyant and comforting images of the psalm’s iconic “green pastures” and “still waters” (v. 2), Whitman makes “a scene, a song” “Of the broad blessed light…,/ And the low hum of living breeze” (not “gloom’s ravines” of Inness’s devising), “and in the midst” of such a rich and ample life is “Sweet, peaceful, welcome Death.” There is a way in which this attitude is fundamentally non-Hebraic. With high infant mortality rates, comparatively short average lifespans (30 years for women, 40 years for men), and deep attachments to the dead ancestors, the ancients, like Whitman, accepted death as a given part of life. Unlike Whitman, the typical pose was to lament death (and suffering), viz. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Ps 22:1; cf. Mark 15:34; Matt 27:46). In the case of “Death’s Valley,” the adoration and trust that drive Psalm 23—a hymnic psalm that is not concerned with death (except in the KJB’s mistranslation)—are taken by Whitman as found and formed into another—a final—rendition of the poet’s familiar pose before death—“Sweet, peaceful, welcome.”

* * *

From the vantage point of this one posthumously published poem both continuities and dissimilarities with the style of the early Whitman as it regards the Bible are noticeable. The impress of the Bible on Whitman continues, as does the poet’s penchant for reading against the grain of its plain sense. Whitman’s conjuring of personified Death as a means of decentering Yahweh in the biblical psalm is a striking example of the latter, lifelong tendency. Whereas the early Whitman worked assiduously to rid his poems of “stock ‘poetical’ touches” and all but the most necessary of second-hand allusions, in “Death’s Valley” biblical stock phrasing abound (“Thou,” “thy,” “thee,” “hast,” “Heaven,” elided past tense verbs, etc.) and there is no reluctance to engage the biblical psalm that inspired Inness’s painting. Indeed, the later Whitman seems much less self-conscious about using language from the Bible generally. Another brief example comes in “If I Should Need to Name, O Western World!”27 The poem was published just ahead of the presidential election of 1884 (later entitled, “Election Day, November, 1884” [LG ]) and has as its basic conceit the scene of Elijah on the mountain waiting for Yahweh to pass by in 1 Kings 19. Famously, there is wind, an earthquake, and fire (all alluding to the episode in Exodus 19 with Moses on Mount Sinai), but Yahweh was not made manifest in any of these natural marvels. Instead, Elijah’s god comes “as a still small voice” (I Kgs 19:12). According to Whitman’s poem the “powerfulest scene to-day” is not America’s natural wonders (paralleling those of the biblical stories) but “This seething hemisphere’s humanity, as now, I’ d name—the still small voice preparing—America’s choosing day,” (line 4). Whitman’s italics signal his verbatim use of biblical language (a coinage which again goes back ultimately to Tyndale, this time from his posthumously published translation of the Former Prophets in Matthew’s Bible of 1537). Not only are second-hand quotations no longer avoided; here the language is even underscored. Here, too, Whitman is happy to read against the biblical grain. His next line parenthetically notes that “(The heart of it not in the chosen—the act itself the main, the quadrennials choosing,),” which would appear to be intended to counter what the Bible’s “still small voice” reveals, namely, that Elijah is to announce to the future kings of Aram and Israel that Elisha is to be Elijah’s prophetic successor (I Kgs 19:15–19)—“the chosen.”

One consequence of this relaxation of some of the stringencies of Whitman’s earlier poetic theory is that the poet’s various biblicisms in these late poems are easier to track, as they are less elusive; indeed, they are often granted semantic visibility at the surface of the poems, as is evident in both “Death’s Valley” and “If I Should Need to Name.”

A further noticeable difference is the reduction in typical lengths of both line and poem—the latter “mutilated” as Whitman observes. These trends toward foreshortening in the later poems have been noted more generally (see Chapter Three). This retraction in amplitude blunts the shaping force the KJB had on Whitman’s early lineal palette. For example, while parallelism continues to feature prominently in Whitman’s poetics, the biblical sensibilities that are so apparent in the poet’s early longer, two-part, internally parallel lines seem less adamant in abbreviation.28 However, since Whitman continues to republish the older poems intermixed with newer poems in succeeding editions of Leaves of Grass the overall impression of these various shifts in style may be more dispersed, less acute. In fact, somewhat counter-intuitively, the greater play of biblical language at the surface of the late poems may give an overall impression of greater biblical influence, even while the impact of the Bible on Whitman’s later poetic style seems less pronounced.

These all are but initial impressions. I offer them here, alongside my closing reading of “Death’s Valley,” as a means of gesturing toward the ongoing need for future scholarship on the topic and of signaling an anticipation of shifts and changes amid continuities as the later Whitman continues to revise and reanimate Leaves with each succeeding edition.29 Only death itself manages to thwart the poet’s penchant for “doings and redoings.”

1 “Whitman’s Debt to the Bible with Special Reference to the Origins of His Rhythm” (unpubl. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas, 1938), 1.

2 A Reader’s Guide to Walt Whitman (Syracuse: Syracuse University, 1970), 24.

5 Letter from H. M. Alder to Walt Whitman (28 August 1889, https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/loc.04087.html. Unfortunately, H. Aspiz’s treatment of the poem in his study So Long! Walt Whitman’s Poetry of Death ([Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama, 2004], 241–43) contains inaccurate or misleading information, including the observation that Whitman “may never have seen the original painting” (242). Strictly speaking this is likely true. But Whitman did have the “proof” of the engraving (by W. Closson), which Alden included with his letter to Whitman and which Whitman acknowledged receiving (and perhaps returning: “illustration in text”) in his return letter to Alden the next day (Letter from Walt Whitman to H. M. Alden [29 August 1889], https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/med.00881.html). Importantly, “Death’s Valley” is a poem that responds to the painting by Inness. Cf. WWWC 5: 470–71.

6 Letter from Walt Whitman to H. M. Alden (29 August 1889).

7 WWWC 5: 471.

8 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 84 (April 1892), 707–0 9, https://whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/poems/per.00028.

9 Letter from H. M. Alden to Walt Whitman (28 August 1889). Cf. W. A. Pannapacker, “‘Death’s Valley’ (1892)” in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (eds. J. R. LeMaster and D. D. Kummings; New York: Garland Publishing, 1998).

10 WWWC 5: 471. Aspiz (Whitman’s Poetry of Death, 242) mistakenly asserts that “the editors chose not to print” this first set of lines.

11 “Aye, well I know ‘tis ghastly to descend,” https://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/transcriptions/loc.00107.html. Several partial, preliminary drafts appear among the images included between pp. 242 and 243 in WWWC 5.

12 N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield: G. & C. Merriam, 1857), 666.

14 New York Herald (26 June 1872), 3.

16 “Had I the choice” was initially published as a part of the sequence “Fancies at Navesink,” The Nineteenth Century 18 (August 1885), 234–37, 234. Cf. LG 1892, 389.

17 WWWC 5: 471.

18 Additional stock elements from “Aye, well I know ‘tis ghastly to descend” include: “Aye” (line 1), inverted syntax (e.g., “well I know,” line 1; “that f valley:/… Grim,” lines 1, 7), “‘tis” (lines 1, 7), and elided spelling of past tense verb (“enter’d,” line 4)—and perhaps the doubled “All, all” (line 4) and “Here, here” (line 7).

19 Whitman alludes to Psalm 23 a number of times elsewhere in his writings, see Posey, “Whitman’s Debt,” 190; B. L. Bergquist, “Walt Whitman and the Bible: Language Echoes, Images, Allusions, and Ideas” (unpubl. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska, 1979), 98, 123, 280, 290, 308.

20 Cf. Pannapacker, “‘Death’s Valley’ (1892)” (“‘Death’s Valley’ echoes the diction and cadence of the Psalms”).

21 S. M. Promey, “The Ribband of Faith: George Inness, Color Theory, and the Swedenborgian Church,” American Art Journal 26 (1994), 52–54. Promey emphasizes the “sharp contrast” between the painting and Whitman’s (supposed) “meditation” on it.

22 For a broad characterization of these ideas, see Aspiz, Whitman’s Poetry of Death, esp. 1–32.

23 “The Tomb-Blossoms” (1842), https://whitmanarchive.org/published/fiction/short, in EPF, 94: “There have of late frequently come to me times when I do not dread the grave—when I could lie down, and pass my immortal part through the valley and shadow, as composedly as I quaff water after a tiresome walk.”

24 HALOT, 1029. Cf. C. L. Seow, Job 1–21 (Illuminations; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 341–43. So elsewhere in the KJB the phrase “shadow of death” is associated with darkness generally (Job 3:5; 10:21–22; 38:17), even where death is not at issue (e.g., Job 16:16; 24:17; 34:33; Ps 44:19; 107:10, 14; Isa 9:2; Jer 13:16; Amos 5:8).

25 The s-genitive, not prominent in the 1855 Leaves, appears three times in the published poem and five times in the rejected stanza.

26 New York Daily Tribune, Supplement (22 March 1850), 1, https://whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/poems/per.00089.

27 Philadelphia Press (25 October 1884), https://whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/poems/per.00010 ; cf. “If I should need to name, O Western World,” https://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/transcriptions/loc.00203.html.

28 Not surprisingly, the two most obviously internally parallel lines in the poem (lines 7 and 18) stretch out to biblical English proportions (14 and 13 words in length).

29 The latter anticipation is acutely observed by K. M. Price in his recent Whitman in Washington: Becoming the National Poet in the Federal City (Oxford: Oxford University, 2022).