2. The Bible in Whitman: Quotation, Allusion, Echo

©2024 F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0357.03

In writing, give no second hand articles—no quotations—no authorities

— Walt Whitman, “med Cophósis”notebook (ca. 1852–54)

In a 1934 article, G. W. Allen pioneered research into Walt Whitman’s biblical quotations and allusions and to date his collection of a hundred and sixty “specific” biblical allusions, echoes, and quotations in Whitman’s writings (prose and poetry), as well as an equally large number of more “general or inclusive allusions” to the Bible, remains the single largest published collection of its kind.1 Articles published since Allen have added to the list of possible biblical allusions, as well as T. E. Crawley’s more in-depth survey of Christ-Symbol imagery in Leaves of Grass (which Allen anticipates),2 and there are several unpublished dissertations on the topic, which (among other things) tally hundreds of more possibilities, especially in Leaves, for which Allen counts less than two dozen echoes of Scripture. After offering preliminary observations made in light of scholarship on the topic since Allen, the chapter is dedicated to documenting Whitman’s allusive practice in the immediate run-up to the 1855 Leaves, from the three unmetered 1850 poems through to the early notebooks and preliminary drafts of lines for the 1855 Leaves. At many points my discussion finds its way from these preparatory materials into the 1855 (and later editions of) Leaves.

Some Preliminary Observations

A number of observations may be offered already in light of the scholarship on biblical allusions in Whitman since Allen. There is much more to assessing and appreciating the allusive texture of an author’s writing than just quantity, but the numbers are not insignificant either. Allen’s sampling alone is warrant enough of Whitman’s knowledge and use of the Bible, even allowing for contested interpretations. In point of fact, however, Allen misses as many allusions, echoes, and quotations as he identifies. The larger counts of M. N. Posey and B. L. Bergquist, who lists a hundred and forty-three biblical allusions in Leaves alone, for example, again allowing for disagreements (e.g., Posey’s and Bergquist’s lists agree only roughly half the time), are surely nearer the mark, and at the very least ramify the Bible’s importance to Whitman. That is, the numbers alone argue the importance of the Bible as a source (of inspiration, language, imagery, etc.) for Whitman.

Second, the direct quotations from the Bible make clear Whitman’s use of the KJB translation. This corroborates what may be inferred from the KJB’s dominance in America during the nineteenth century and what is known from the bibles that can be tied directly to Whitman. And how Whitman quotes is of interest as well. As Bergquist notices there are times when it is clear that Whitman must have a Bible open before him, but just as often Whitman is content to paraphrase (and massage) from memory.3 As an example of the former, Bergquist cites a Christmas editorial from the Daily Eagle which includes multiple exact quotes from the Christmas story in Luke (2:14; 2:10; 1:79).4 In another example, the full quotation of Zech 13:6 (with citation noted) is offered as the headnote to “The House of Friends” (1850): ‘”And one shall say unto him, What are these wounds in thy hands? Then he shall answer, Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.’—Zechariah, xiii. 6.”5 An interesting example of Whitman’s tendency to paraphrase comes in the version of Gen 1:31 (the “spinal meaning of the Scriptural text,”) in “A Memorandum for a Venture” from Specimen Days: “God overlook’d all that He had made, (including the apex of the whole—humanity—with its elements, passions, appetites,) and behold, it was very good”6—the last exact. Of interest is that Whitman revised the phrase “God overlook’d all that He had made” from an earlier “God weighed all that He had made,”7 though (apparently) not going to the KJB to get the wording exactly right: “And God saw everything that he had made.” What is significant here is Whitman’s bent toward revision and tinkering, a characteristic that is amply manifested in the notebooks and unpublished poetry manuscripts and in Whitman’s lifelong revision of Leaves of Grass. Most scholars do not deny the Bible’s influence on Whitman, and yet there seems to be a strong want to emphasize the unconscious nature of the influence.8 But everything that is known about Whitman’s writing process, especially evident in the notebooks, is that conscious deliberation is integral to it—“a deliberate effort of construction.”9 Surely the Bible did exert unconscious influence on Whitman, perhaps a great deal. But most of what can be tracked, contrary to the impression, is Whitman’s conscious use of the Bible (even when such consciousness leads Whitman to erase the biblical lineaments).

Another preliminary observation concerns Bergquist’s statistical overview. Even if only taken heuristically, it is telling. Roughly the same amount of allusive referencing of the Bible appears in Leaves as in Whitman’s other writings and does not vary so markedly chronologically or across genres—all trends contrary to Allen’s impressions.10 There is rough continuity across the writings as well in the uses to which Whitman puts his allusive discourse. Emblematic of this is the poet’s proclivity (across all genres) to read the Bible as much against the grain of its meaning as with it.11 Bergquist cites an example from one of Whitman’s editorials (“American Workingmen, versus Slavery”) in which “what is interesting” is that Whitman takes an obvious allusion to Gen 3:19 and “manipulates it so that the traditional ‘curse of Adam’ sounds like a most desirable aspect of our human heritage.”12 In Leaves Whitman famously and wonderfully reads “Lucifer” (from the Vulgate, lucifer; Hebrew hêlēl lit. “shining one”)13 against the mocking thrust of Isaiah’s parody of a dirge for the king of Babylon (Isa 14:12). For Isaiah the figure is meant to be belittling, the fall from heaven (to the underworld—“to hell”) symbolizing the king of Babylon’s fall from favor (cf. Lam 2:1).14 The conventional “how” of lament (Hebrew ʾêk) is turned into a mocking, gleeful gloat: “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!” Whitman, however, redeems the figure of Lucifer, associating it with rebellion and admiring the “resistance to the all-powerful God.”15 This is made clear, as E. Folsom notes, in a reference from the early and never published “Pictures”:16

And this black portrait—this head, huge, frowning, sorrowful, I think it—is Lucifer’s portrait—the denied God’s portrait,

(But I do not deny him—though cast out and rebellious, he is my God as much as any;)17

“Black Lucifer” is one of Whitman’s most powerful and evocative images of slavery and one of the earliest instances in American poetry, according to Folsom and K. M. Price,18 where a white poet gives over the narrative voice of a poem to a black character:

Now Lucifer was not dead…. or if he was I am his sorrowful terrible heir;

I have been wronged…. I am oppressed…. I hate him that oppresses me,

I will either destroy him, or he shall release me.

Damn him! How he does defile me,

How he informs against my brother and sister and takes pay or their blood,

How he laughs when I look down the bend after the steamboat that carries away my woman.

Now the vast dusk bulk that is the whale’s bulk…. it seems mine,

Warily, sportsman! though I lie so sleepy and sluggish, my tap is death. (LG, 74)

In a preliminary version of these lines, Whitman verbalizes his intent: “You You He cannot speak for yourhimself, slave, negro—I lend you him my own mouth tongue.”19 And also in the “Poem incarnating the mind” notebook, after a section of writing that eventually gets worked into Whitman’s sketch of the “hounded slave” (LG, 39), there is a canceled reference to Lucifer: “What Lucifer felt cursed when tumbling from Heaven.”20 In the material that precedes this comment the ventriloquizing is made visible as Whitman can be seen revising the voice of his discourse from third to first person (e.g., “His blood My gore”). It perhaps merits underscoring that it is an image from that most un-racial (literally before race) of books, the Bible, that provokes Whitman’s racial crossing in this instance and the compellingly humanitarian and empathetic portrayal of a black person (“Black Lucifer”) that results.21 And yet even when the biblical source informing Whitman’s language is not in doubt, as with the figure of Black Lucifer, other potential influences are often also detectable. Whitman’s collaging frequently involves imbrications of multiple resource materials. In this case, the impulse to use a biblical figure to animate the lived experiences of enslaved African-Americans is shared with the evocation of Black Samson in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Warning” (viz. “The poor, blind Slave,…/… There is a poor, blind Samson in this land,” lines 11–13), and is likely not accidental.22 The latter was widely noticed after its initial publication.23 Whitman, early and late, was an admirer of Longfellow,24 and crucially he reviewed Longfellow’s The Poems of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1846, a volume that includes “The Warning” (and Longfellow’s other “Poems on Slavery”).25

A subtler example comes from the beginning of what would become section 19 of the “Song of Myself”:

This is the meal pleasantly set…. this is the meat and drink for natural hunger,

It is for the wicked just the same as the righteous…. I make appointments with all,

I will not have a single person slighted or left away,

The keptwoman and sponger and thief are hereby invited…. the heavy-lipped slave is invited…. the venerealee is invited,

There shall be no difference between them and the rest. (LG, 25)

Folsom and C. Merrill begin their commentary on this section of (the later) “Song of Myself” by calling attention to the “meal table,” which in most cultures provides “sacred space, an intimate place that gathers family and friends—those that we select out from the multitude.”26 However, the table fellowship tradition this passage most obviously echoes is the Lord’s supper tradition of the gospels and Paul (Matt 26:26–29; Mark 14:22–25; Luke 22:14–22: 1 Cor 11:17–34) (and its regular instantiations in Christian liturgy).27 Whitman’s opening line in particular mimics the rhythm of the Lukan version: “This is my body which is given for you: do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19; cf. 1 Cor 11:14)—the deictic “this” is remarkable, and especially important to the larger section in Whitman’s poem.28 “Meat and drink” (Rom 14:17)29 and the “wicked” and the “righteous” (155x together in the KJB) are biblical tropes. Whitman is intent, of course, on overturning the heavenly or otherworldly thrust of the biblical tradition (esp. Matt 26:29; Mark 14:25; Luke 22:16, 18) in favor of satisfying “natural hunger” and emphasizing the democratic nature of the meal his poem means to “equally set” (as in the later “Song of Myself”).30 Indeed, Whitman may well have perceived Jesus’s meal with “the twelve apostles” (Luke 22:14) as epitomizing anti-democratic intimacy. Yet Paul, like Whitman, appears to emphasize the inclusivity of the invitation to the table (esp. 1 Cor 11:17–18, 33).

Finally, not only does Whitman read the Bible against the grain of its plain meaning, but often his collaging results in new poetic creations that echo, vary, or supplement the biblical source materials while overwriting them. This is not so much allusion as that quintessential anxiety of influence in response to a strong literary antecedent.31 This general pose toward the Bible is perhaps made most explicit during the preparation of the 1860 edition of Leaves as the “New Bible”—the very conceptualization of which signals Whitman’s responsive and competitive aspirations. But it is also evident earlier, as made manifest in Whitman’s great commandment about organic fluency from the 1855 Preface:

Who troubles himself about his ornaments or fluency is lost. This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body. (LG, v–vi)

The set-up, “This is what you shall do,” is composed of (modernized) biblical phrasing: “thou shalt do” occurs twenty-four times in the KJB and “what thou shalt do” three times, including “and he will tell thee what thou shalt do,” Ruth 3:4; cf. 1 Sam 10:8; 2 Sam 16:3). The long length of what the poet’s addressee “shall do” with its thirteen imperatives obscures its scriptural inspiration, first, in the Mosaic injunction to love God (Deut 6:4–9) and neighbor (Lev 19:18), and then in Jesus’ own riffing on and replaying of these great commandments, especially in Matt 5:43-45 (cf. Matt 22:36–40; Mark 12:28–34; Luke 10:25–28).32 While the long catalogue of imperatives is quintessential Whitman, there are a number of intriguing Pauline forerunners that anticipate this Whitmanian stylistic tick. 1 Thess 5:14-23 reads as follows:

Now we exhort you, brethren, warn them that are unruly, comfort the feebleminded, support the weak, be patient toward all men. See that none render evil for evil unto any man; but ever follow that which is good, both among yourselves, and to all men. Rejoice evermore. Pray without ceasing. In every thing give thanks: for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus concerning you. Quench not the Spirit. Despise not prophesyings. Prove all things; hold fast that which is good. Abstain from all appearance of evil. And the very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Let love be without dissimulation. Abhor that which is evil; cleave to that which is good. Be kindly affectioned one to another with brotherly love; in honour preferring one another; Not slothful in business; fervent in spirit; serving the Lord; Rejoicing in hope; patient in tribulation; continuing instant in prayer; Distributing to the necessity of saints; given to hospitality. Bless them which persecute you: bless, and curse not. Rejoice with them that do rejoice, and weep with them that weep. Be of the same mind one toward another. Mind not high things, but condescend to men of low estate. Be not wise in your own conceits. Recompense to no man evil for evil. Provide things honest in the sight of all men. If it be possible, as much as lieth in you, live peaceably with all men. Dearly beloved, avenge not yourselves, but rather give place unto wrath: for it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord. Therefore if thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink: for in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head. Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.

Matt 5:44 contains its own run of four such imperatives (“Love,” “bless,” “do good,” and “pray”) and is followed in the next verse by a purpose or result clause (“That ye may be…,” v. 45), which in function is not unlike Whitman’s final clause, “and your very flesh shall be….” The structural logic of the whole is the same in both cases, and Matt 4:43 makes it apparent that Jesus acknowledges the old commandment while doing it one better, or perhaps more charitably, while updating and applying it to his own time and place. That is, the gospel passage gives Whitman the idea for his own hermeneutic when it comes to the Bible, viz. “adjusted entirely to the modern.”33

Interestingly, Whitman’s commandment feels at times like the expanded exegesis of some Targums—the Targums were early Jewish translations of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic.34 Some Targums are expansive. An example of an expanded reading appears in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan’s rendering of the love of God command in Deut 6:5: “Moses the prophet said to the people, the House of Israel, ‘Go after the true worship of your fathers, and love the Lord your God with the two inclinations of your mind, even if your life and all of your money are taken from you.’” The underlying Hebrew text is still visible even in such an expanded and highly interpretive rendering. In Whitman’s Preface the opening command to “Love” with its triple object (“the earth and sun and the animals”) mimes the rhythm and feel of the love command in the Shema, “And thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might” (Deut 6:5).35 The command to “read these leaves” responds to the biblical instruction to memorize, teach, and write down the words of the Shema (Deut 6:6, 7, 9). Instead of binding the words “upon thine hand” and “as frontlets between thine eyes” (Deut 6:8), as Moses urges, Whitman’s promise for all who obey his own charge is that “your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body.” This latter is especially redolent of its biblical model.36

The principal intent in the foregoing example, again, is not to allude in any strong way to the biblical commandments, but rather to respond to them, to carry forward their “autochthonic bequests… adjusted entirely to the modern” and adapted to the needs of American democracy. The chief effect is that of an echo, an oblique resounding at a distance both familiar and distinct.

“No Quotations”: The 1850 Poems

Where there is a difference between the allusions in Leaves of Grass (especially in the 1855 edition) and the rest of Whitman’s writings is in the nature of the allusions. In Leaves there are no extended quotations of biblical passages (“You shall no longer take things at second or third hand…. nor look through the eyes of the dead…. nor feed on the spectres in books” (LG, 14), and allusions “become more ‘elusive,’ more hidden.”37 Exemplary is Whitman’s central image of “grass” in “I celebrate myself,” which owes a debt to the Bible, as Zweig notices: “All flesh is grass, laments Isaiah in a passage [Isa 40:6–8] Whitman surely knew; after a season, it dies. But the grass grows again; and leaves of grass—those ‘hieroglyphics’ of the self, that book not a book, of poems that are not poems—they, too, will grow again, if the reader will stoop to gather them up.”38 Whitman, of course, as is often his want, massages the image to suit his own ends. In this case, he takes the biblical image of grass as signifying human transience (“the grass withereth,” Isa 40:8) and molds it into a sign of optimism and democratic equality,39 that which is always emerging anew from the very realm of death (“the beautiful uncut hair of graves,” LG, 16). Not only does Whitman’s language at the beginning of what becomes section 6 of “Song of Myself” mime that of the anonymous prophet of the exile (“A voice said”// “A child said”; “What shall I cry?”// “What is the grass?”), but Whitman even provides his own kind of “hieroglyphic” pointing to his source—“it is the handkerchief of the Lord” (LG, 16).40 And at the end of the poem, referencing the speaker’s mortality, Whitman retrieves the biblical sense of grass as a cypher of human transience, not to lament but to celebrate and luxuriate in:

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift it in lacy jags.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles. (LG, 56)

Like so many of the echoes of Scripture in Leaves, this one serves Whitman’s present-oriented poetic ends and does not flaunt its biblical lineage.

The lack of quotations in Leaves follows from the aesthetic sensibility that Whitman was evolving in the early 1850s, as Allen well recognizes specifically with reference to the Bible: “Of course, it must be remembered that the use of literary allusions was against the avowed poetic doctrines for Leaves of Grass.”41 The sentiment is most explicitly articulated in a manuscript fragment known as the “Rules for Composition,” conjectured to date from sometime in the early 1850s. One portion of the “Rules” reads as follows:

Take no illustrations whatever from the ancients or classics, nor from the mythology, nor Egypt, Greece, or Rome—nor from the royal and aristocratic institutions and forms of Europe.—Make no mention or allusion to them whatever, except as they relate to the new, present things—to our country—to American character or interests.—Of specific mention of them, even infor these purposes, as little as possible.—42

The Bible is not explicitly mentioned in the “Rules for Composition” fragment, although there is the intriguing canceled notation at the bottom of the leaf, “Mention God not at all.” This “God” is above all the God of the Bible (capitalized appropriately) who does in the end get mentioned quite often in the 1855 Leaves (e.g. “As God comes a loving bedfellow,” LG, 15). Regardless, that the Bible falls under the purview of the “Rules” is perhaps one implication to be drawn from the canceled comment. And the Bible is also likely assumed in the catch-all references to “the ancients.” The list that follows is of the kind, as noted earlier, where Whitman has included the Bible, which is after all exemplary and not comprehensive in nature.43

In this case, what Whitman explicitly theorizes can also be tracked in his poetic practice. The three unmetered 1850 poems—“Blood-Money,”44 “The House of Friends,”45 “Resurgemus”46—begin to anticipate Whitman’s mature poetry in important ways. So much so that P. Zweig says of “The House of Friends” in particular, of that poem’s “angry rhythm” and its suggestion of Whitman’s later line, that “here, maybe, is the very dividing line between the two styles”—between the style of the “juvenile” poems and the style that characterizes the 1855 Leaves.47 The three poems do indeed constitute something of a dividing line on many aspects, including the use of quotations—“in writing, give no second hand articles—no quotations—no authorities” (“med Cophósis” notebook).48 “The House of Friends,” as already mentioned, cites Zech 13:6 in whole, with quotation marks and citation, as its epigraph, and the title itself is a slightly adjusted (as in l. 3) quote (KJB: “the house of my friends”).49 Whitman either did not completely understand the context of Zech 13:2–650—and admittedly the context (and content) is not so obvious, especially in the KJB translation—or, as likely, was attracted mainly to the image of the speaker wounded in the house of his friends. The latter is used by Whitman to allude to the betrayal (in his view) of the North in the debates over slavery and the Compromise of 1850. The opening lines contain a few biblicisms (“thou art,” “thy,” and “house of friends,” which is a close version of the Bible’s “house of my friends”) and the poem closes with the admonition to the “young North” to “Arise” and “fear not,” both commonplaces, especially in the prophetic literature. Indeed, the serial apostrophes to the various states (e.g., “Virginia, mother of greatness,” “Hot-headed Carolina”) even faintly recall the famous pattern (poetic) oracle against the nations in Amos 1:3–2:16 (e.g., “For three transgressions of Damascus, and for four,” Amos 1:3).

Similarly, “Blood-Money” features an epigraph citing a close version of 1 Cor 11:27, also set apart in quotation marks (though no explicit citation): “Guilty of the Body and Blood of Christ” (compare KJB: “guilty of the body and blood of the Lord”).51 Whitman’s change from “Lord” (Greek kyriou) to “Christ” is perhaps a clarifying gesture, and the added capitalization for emphasis. The title itself alludes to Matt 27:6, as Bergquist maintains (“Then went Judas, and sold the Divine youth,/ And took pay for his body”).52 Whitman even quotes from the Bible (Matt 26:15) within the body of the poem itself (lines 12–14):

Again goes one, saying,

What will ye give me, and I will deliver this man unto you?

And they make the covenant and pay the pieces of silver.

Here, too, I have the sense that Whitman’s diversions from KJB (“And said unto them, What will ye give me, and I will deliver him unto you? And they covenanted with him for thirty pieces of silver.”) are mostly contextual adjustments. This is certainly the case with the change from “him” to “this man,” since the quote has been lifted out of its immediate narrative context where the identities of the characters are clear. The dropping of the specific sum (‘thirty”) may be in deference to the new “cycles” where the “fee” need only be “like that paid for the Son of Mary.” Also, however, such deviations become characteristic of how Whitman collages. Once finding a bit of readymade language of interest (as in the Bible), he shapes it to suit his poetical ends.

Of the three poems, “Resurgemus” is the most mature, exhibiting the “rhythmical instinct” that will characterize Whitman’s later poetry, and is the only one to be included (albeit in revised form) in the 1855 Leaves (LG, 87–88). “Resurgemus” exhibits no direct quotations from the Bible, though the Bible’s imprint on the poem remains palpable in the mention of “God” (first word in the second stanza) and of a biblical figure (“Ahimoth, brother of Death,” cf. 1 Chron 6:25),53 allusions (e.g., “And all these things bear fruits, and they are good,” cf. Gen 1:12, 31),54 and even in aspects of Whitman’s diction (e.g., “thee,” “lo” [followed by comma—“lo,”—as throughout the KJB], “locusts,” “seed”).55 Of these, the direct reference to “God,” “Ahimoth,” the biblical figure of “locusts,” and the twofold use of “thee” in the final stanza are excised in the 1855 version of the poem—all no doubt in violation of the poetic theory that Whitman had by then evolved.56 However, the allusions stay, given their present relevance and their more “elusive,” worked over texture. The latter is especially well evidenced in the poem’s final lines, which clearly allude to “the coming of the Son of Man,” though they have been worked over such that the tracks of the source text have been well covered (see Matt 24:42, 48–50; 25:13; Mark 13:34–35 [“Watch ye therefore: for ye know not when the master of the house cometh”]; Luke 21:36; Acts 20:31):57

Liberty, let others despair of thee,

But I will never despair of thee:

Is the house shut? Is the master away?

Nevertheless, be ready, be not weary of watching,

He will surely return; his messengers come anon.58

Therefore, certainly with respect to this one dimension of Whitman’s evolving poetic theory—“no quotations”—1850 and the three poems composed during that spring and summer do seem to offer something of a watershed, a “dividing line.” At that time, Whitman could still freely embed quotations in his poems. Beginning with “Resurgemus” and by the time of the early notebooks (1852 to 1854)59 and then in the 1855 Leaves, Whitman’s new poetics is firmly in place: no more direct quotations, a concerted trimming away of (some) biblical and other literary trappings—those “stock touches,” and a tendency to work over allusions to the point that they become, as Bergquist says, “more ‘elusive,’ more hidden.” The latter is already well-evident in the 1850 version of “Resurgemus,” and Whitman’s revisions of the poem for inclusion in the 1855 Leaves reveal still others. It is perhaps no accident that these stylistic developments all start with three poems heavily invested in the Bible. The period corresponds with the point at which Whitman starts referencing the “poetry” of the Hebrew Bible and the time of his self-study, which included (some) secondary literature about the Bible. The poems themselves have their most immediate provocation in the slavery issue and the political machinations leading up to the Compromise of 1850, to which Whitman was adamantly opposed.60 The biblical quotations, allusions, and phraseology are not incidental, as M. Klammer notes with respect to “House of Friends” in particular, as each side in the slavery debates “attempted to buttress its position with references to the Bible.”61 But at any rate it is with respect to biblical quotations that one can actually track Whitman’s theory about writing in his own writing practice.

The Bible in Whitman’s Prose from 1850–53

The 1850 poems are the last writings Whitman composed with line breaks until the trial lines of the early notebooks (with their signature “hanging indentations”). However, there is now a goodly amount of prose (mostly journalistic in nature) from the three-plus-year period between the time of the 1850 poems and the late summer of 1853—nearly two dozen separate pieces. This material shows Whitman writing abundantly (thinking in particular of the two novelistic contributions, “Sleeptalker” and “Jack Engle”),62 almost up until the time of the early pre-Leaves notebooks. Some of this writing has long been known to Whitman scholars and features in the surveys of biblical allusions by Allen and others. Other material has only recently been recovered (e.g., “Jack Engle”). In general, these prose writings share the same basic attitude to the use of the Bible as is evident in the 1850 poems: the Bible is not prohibited; indeed, as it never appears to be in Whitman’s prose writings. This is most explicit in the “Art and Artists” lecture, which besides the two pieces of long fiction, is perhaps the most carefully crafted essay of the period. It is, as R. L. Bohan observes, “studded with quotations from and indirect references to Emerson, the Bible, Carlyle, Ruskin, Rousseau, Shakespeare, Pope, Bryant, Horace, Socrates, and an unnamed Persian poet”63—Whitman is clearly not worried about second-hand attributions. In addition to the long, rhythmic paraphrase of Genesis 1 previously discussed (see Chapter One), there is also a riff on the risen Christ’s commandment, “And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature” (Mark 16:15): “To the artist, I say, has been given the command to go forth into all the world and preach the gospel of beauty.”64 Here the use of biblical language and form (i.e., a command) is intended to layer Whitman’s aesthetic charge with the familiarity and traditional authority of the gospel saying.

Some further examples will illustrate Whitman’s practice in this material. Periodic eruptions of stylistic flourishes that will typify (much of) the 1855 Leaves are not uncommon, and often are accompanied by (more and less) obvious biblicisms. The editors of the Walt Whitman Archive call attention, for example, to the following paragraph from the third of the so-called “Paumanok letters” (of 1851),65 noting how its “tone and style” anticipate “Song of Myself”:

Have not you, too, at such a time, known this thirst of the eye? Have you not, in like manner, while listening to the well-played music of some band like Maretzek’s, felt an overwhelming desire for measureless sound—a sublime orchestra of a myriad orchestras—a colossal volume of harmony, in which the thunder might roll in its proper place; and above it, the vast, pure Tenor,—identity of the Creative Power itself—rising through the universe, until the boundless and unspeakable capacities of that mystery, the human soul, should be filled to the uttermost, and the problem of human cravingness be satisfied and destroyed?

The run of rhetorical questions come in for particular comment, reminiscent, as they are, of Whitman’s “strategic use” of such questions in Leaves, such as in the following passage:

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

Have you practiced so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems? (LG 14)

Such questions have a biblical lilt about them. The phrase “have ye not” appears twenty-six times in the KJB, often similarly rhetorical in nature, including this short run from Isa 40:21: “Have ye not known? have ye not heard? hath it not been told you from the beginning? have ye not understood from the foundations of the earth?” The lineation of the Leaves passage helps bring out the parallelism (itself a device with a biblical lineage, see Chapter Four) that is present also in Isaiah (a triplet or pair of couplets in the original Hebrew, cf. BHS, NRSV) and in the journalistic passage.

An uncollected newspaper column from the Brooklyn Evening Star (24 May 1852), entitled “An Afternoon Lounge About Brooklyn,” offers another example of writing that anticipates the mature poetry of Leaves. This one contains one of those ample and ambling sentences (fifty-three words) that come to characterize Whitman’s sentential palette in the early Leaves:

Brooklyn is especially beautiful as a summer town. The innumerable trees—the elevated grounds—the views of land and water—the hundreds of choice private gardens, with the frequent glimpses, here and there, of the rare collections in the private conservatories of fruits and flowers, all cause the time of the singing of birds to be our city’s special season of attraction.66

The long dashes are used, much like the suspension points in the 1855 Leaves, to provide the undergirding necessary to support Whitman’s complex and expansive subject (37 words long, no verbs). And Whitman brings the sentence to a close by lifting a phrase from the Song of Songs’ own paean to spring, Song 2:8–17: “the time of the singing of birds” (2:12). The allusion may well be intentional, and yet Whitman is not quoting or citing the biblical text but folding its phrasing into his writing, appropriating its language as his own. Another example comes from one of the long known 1851 “Letters from Paumanok.”67 Here Whitman is reporting an encounter between old “Aunt Rebby” (“she was seventy years old”—“Rebby” is presumably short for “Rebekah”) and Whitman’s equally biblically named interlocutor, “Uncle Dan’l,” whom the old woman at first fails to recognize. When she does recognize him, Whitman writes: “A new light broke upon the dim eyes of the old dame.” The trope of “dim eyes” appears eight times in the Bible, mostly in descriptions of the elderly (Gen 27:1 [said of Isaac, Rebekah’s husband]; 48:10; Deut 34:7; 1 Sam 3:2; 4:15; cf. Job 17:7; Isa 32:3; Lam 5:17).68

The phrase “talents of gold” appears in the last of Whitman’s 1850 “Letters from New York” (also signed “Paumanok”).69 The phrasing is straight from the KJB where “talent” is a unit for measuring gold or silver (Hebrew kikkar/kikkārîm; with gold, 1 Kgs 9:14; 10:10, 14; 1 Chron 22:14; 29:4; 2 Chron 8:18; 9:9, 13; with silver, Exod 38:27; 1 Kgs 20:39; 2 Kgs 5:22; 15:19; 1 Chron 19:6; 22:14; 25:6; Ezra 8:26; Est 3:5). Here Whitman’s collaging of language is accompanied by his massaging of the meaning toward the more standard connotation of the English, viz. talent as aptitude, ability, facility, gift, knack. So “talents of gold,” like Whitman’s own parallel coinage, “endowments of silver” (p. 316; echoing the Bible’s occasional joining of the two phrases, e.g., 2 Kgs 18:14; 23:33; 2 Chron 36:3), are “the highest order of gifts and blessings” (p. 316). The letter also mentions “commentators on the Bible” (p. 314), God (pp. 315, 317), “tales of Gog and Magog” (cf. Ezek 38:2; Rev 20:8; p. 316), and “leaven” that “leaveneth the whole lump” (1 Cor 5:6;70 Gal 5:9; p. 317). Other notable examples of collaged biblical phrasing include “light of life” (John 8:12),71 “Priests of the Sun” (2 Kgs 23:5),72 and the biblicized “and will satisfy any man that hath eyes to see” (cf. Deut 29:4; Ezek 12:2),73 all in regard to the new technology of the daguerreotype and all from the summer of 1853.74

Given its recent recovery, Whitman’s anonymously published novella “Jack Engle” deserves some attention.75 There are more than thirty obvious biblicisms, including names that derive from biblical characters (e.g., “Ephraim Foster,” p. 264; “Rebecca,” p. 274; “Isaac Leech,” p. 288), biblical language (e.g., “ministered unto,” p. 268—22x in KJB; “I say,” pp. 271, 332—212x in KJB; “blessed is/are,” p. 272—37x and 31x respectively in in KJB; “saith,” p. 273—1262x in KJB; “O, Lord!” [353x], “brethern” [563x] and “Amen” [78x], pp. 298–99), direct quotations (e.g., “spirit of Christ,” (p. 268—Rom 8:9; 1 Pet 1:11; “angel from Heaven,” p. 270)—Gal 1:8; “lusts of the flesh,” p. 300—2 Pet 2:18; “in the twinkling of an eye,” p. 316—1 Cor 15:52), and allusions (e.g., “and wouldn’t have taken the name of the Lord in vain,” p. 281—Exod 20:7; Deut 5:11; watchmen scene, pp. 321–26—Song 3:1–5; 5:2–8; “as the dove, which went forth from the ark,” p. 333—Gen 8:8–12; “sower of seeds that have brought forth good and evil,” p. 334—Matt 13:4, 19, 24, 29, 31; Luke 8:5; cf. 2 Cor 9:10; “the serpent has cast his slough,” p. 345)—Genesis 3). One of the more remarkable biblical inflections in “Jack Engle” is a close version of 1 Cor 15:52 (“the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised”), which Whitman lineates as verse: “The trumpet shall sound,/ And the dead shall rise” (p. 335). This comes from one of the epitaphs on a gravestone, some of which Whitman copied out from actual headstones and used in his story.76 In fact, Whitman has Jack Engle, on his “ramble” through the Trinity Church graveyard, copying down such epitaphs—“I put my pencil and the slip of paper on which I had been copying, in my pocket” (p. 336). Whitman himself loved such rambles and his avid note taking in small handmade notebooks is amply attested. The fictionalized process here is a reflection of one of Whitman’s favored modes of composition—collaging—and that he models Jack’s ramble on his own habits anticipates Whitman’s later move to first-person discourse in Leaves. And as significant, this may well offer another concrete example of Whitman literally making verse out of biblical language.77

There is nothing especially biblical about “Jack Engle.” And yet the thirty odd biblical phrases, echoes, allusions, and adaptations from the novella show Whitman’s easy familiarity with the Bible and how ready he is in the spring of 1852 to absorb its language into his own writing.

In sum, although there is no new verse production during this period (aside possibly from the [readymade] versified tombstone inscription of 1 Cor 15:52), Whitman continues to write (in quantity) and continues to evolve and hone a style of writing that will eventually come to characterize the nonnarrative poetry of the 1855 Leaves.78 Biblical and biblicized phrasing abounds in this material. Such phrasing is not chiefly citational in orientation but forms part of the collaged language materials that Whitman absorbs into his writing. In these mainly occasional pieces the lifted phrases are mostly left as taken, their biblical patina not yet burnished away, and hence easily recognizable.

Biblical Echoes in the Early Notebooks and Unpublished Poetry Manuscripts

The early notebooks and unpublished poetry manuscripts fill in another part of the gap between the three 1850 poems and the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Here I turn, first, to the early (1852–54) notebooks, and then to the never published poem, “Pictures,” and a sampling of some of the pre-Leaves poetry manuscripts. In this preparatory material leading up to the 1855 Leaves, the biblical allusions, echoes, and stylistic borrowings begin to take on the “more ‘elusive’” texture of the 1855 Leaves, though many are still readily traceable, perhaps because most of this material was not yet (if ever) finalized for publication. Before focalizing this early material, however, I want to consider a later (Grier: “after July 1, 1865”) pantomime of an “old Hebrew” prophet in a manuscript scrap entitled, “We need somebody.”79 Here Whitman calls for the making of a national literature (following Emerson and Carlyle, and himself in the 1855 Preface). What is of interest is how he names and then shapes this call as if it were a prophetic utterance from the Bible. He begins: “We need someth somebody or something, whose utterance is were like that [illeg.] of an Hebrew prophet’s, only substituting rapt Literature instead of the rapt religion.” He then gives us the “utterance sh crying aloud”:

“Hear, O People! O poets & writers, you ye have supposed your made of literature as an accompaniment, an adjunct, as if the same as the upholstery of your parlors, or the confections of your tables. Ye have made a mere ornaments, a prettiness. you Ye have feebly followed & feebly multiplied the models of other Yet lands. & put Ye are in the midst of idols, of clay, silver & brass. I come to call you to the truth knowledge of the Living God, in writings. Its liter Its own literature, to a Nation, is the first of all things. Even its Religion appears only through its Literature, & as a part of it. Know ye, Ye may have all other things possessions but without your own grand Soul’s Literature, ye are as but little better than an[?] trading prosperous beasts. Aping but others ye are but intelligent apes. Until ye prove title by productions, remain subordinate, & cease those that perpetual windy bragging. Far, far above also all else, in a nation, & making all its men to move as gods, behold in a nation nation race its orignal own poets the bards, orators, & authors, born of the spirit & body of the race nation.80

This is clearly intentionally over the top and Whitman means to make his own “aping” of a prophetic judgment oracle obvious (e.g., address, complaint and judgment, call for new behavior—the making of the nation’s own literature, proclamation of good news—“behold… the bards”). Contrary to his poetic theory,81 instead of getting rid of stock phrases and unnecessary “ornaments” he puts them in. The King James “ye,” for example, occurs a total of nine times. At several points Whitman slips and writes “y/You,” cancels it and inserts “y/Ye.” He tells us it is like an “old Hebrew prophet’s” utterance and then proceeds to litter the passage with phrasal echoes of the Bible, e.g., “Hearken, O people” (1 Kgs 22:28) or “Hear, all ye people” (Mic 1:2); “thou hast moreover multiplied thy fornication in the land of Canaan unto Chaldea” (Ezek 16:29); the famous “image” of Daniel 2 is made up of silver, clay, and brass (esp. vv. 32–33); “I am not come to call the righteous” (Matt 9:13); and in two cases there are actual phrases from the Bible—“Living God,” occurring thirty times in total (the capitalization helps to secure readerly attention) and “behold,” which appears over a thousand times in the Hebrew Bible alone, most often as a translation of Hebrew hinnê. And all, of course, is in prose just like all of the prophetic literature in the rendering of the KJB.

I cite this lampoon for two principal reasons. First, it underscores the centrality of the prophetic to Whitman’s poetic sensibility, which though widely stipulated is also perhaps too easily (and often) sublimated. No doubt he owes much to Carlyle and Emerson for his conception of the poet-prophet whose voice is heard commanding assent throughout the 1855 Leaves.82 But the idea is ultimately rooted in “old Hebraic anger and prophecy.”83 Robert Lowth, and thus the Bible, is the ultimate source for this Romantic conceit—it “runs from Lowth to Blake, to Herder, and to Whitman.”84 Whitman himself acknowledges the biblical source of this Romantic pose in his entry, “The Death of Thomas Carlyle,” included in Specimen Days, where he writes admiringly of Carlyle, “Not Isaiah himself more scornful, more threatening” and then quotes Isa 28:3–4 (from the KJB): “The crown of pride, the drunkards of Ephraim, shall be trodden under feet: And the glorious beauty which is on the head of the fat valley shall be a fading flower.”85 And his own “dream” about the rise of a future “race of… poets” who are “newer, larger prophets—larger than Judea’s, and more passionate.”86 As J. R. LeMaster emphasizes, “That Whitman presented himself as a prophet is beyond doubt.”87 And that his conception of prophecy owes a huge debt to Isaiah and the corpus of prophetic poetry in the Bible is equally beyond doubt—as the early twentieth-century Hebrew poet Uri Zvi Greenberg emphasizes, “Whitman should have written in Hebrew, since he is molded from the same substance as a Hebraic prophet.”88 And thus this is another tell of the Bible’s import to Whitman.

Second, the pantomime of an “old Hebrew” prophetic utterance in “We need somebody,” in its explicitness and exaggeration, also enables a better appreciation of another dimension of Whitman’s debt to the Bible, his mimicry of it. The Bible’s influence on Whitman has been measured mostly by the degree to which he can be seen directly engaging the Bible, e.g., through allusion, by borrowing biblical phrases, by referencing it. Yet there are not many direct biblical references in Leaves. By far the largest way in which the Bible has influenced Whitman is in his adoption of its manner(s) of phrasing, its rhythms and parallelism, its genres, even its formatting, and then shaping them to suit his own poetry, themes, diction, etc. And so I have gathered some of Whitman’s references to biblical prophecy and prophets (e.g., Isaiah), but far more telling is how Whitman himself takes on this persona, this pose—the poet-prophet, and enacts it throughout his mature poetry. There, of course, with few exceptions (e.g., “The dirt receding before my prophetical screams,” LG, 31), it usually goes un-explicated, un-narrated, un-designated. Hence, the importance of the pantomime. In it we catch Whitman doing what he always does but here the mimicry is intentionally made plain for all to see. Allen’s diagnosis of Whitman’s adoption and adaptation of biblical parallelism is perhaps the parade example of such mimicry (see Chapter Four). Much of what I have to say about Whitman’s line, lyricism, free verse, and prose style is in an effort to locate and unpack the artistry of such mimicry. The difference is, we usually lack a pantomime or some other means of self-explication by which to catch Whitman in the act of imitation, of borrowing, of working and re-working, of writing and re-writing until he makes what he borrows his own. In these instances, I will only be able to triangulate on Whitman’s biblical imitations up to a point and then no further. But at least in this case, we may be certain of the ultimate source of his prophetic pose.

* * *

Now to the early notebooks and their biblical inflections. Perhaps the earliest pre-Leaves notebook, the “Autobiographical Data” notebook, appears to have been used over an extended period of time (1848–55/56),89 and thus only some aspects of its content may be fixed more precisely. Still, the notebook contains a number of general references to the “Bible” and queries rhetorically, “[illeg.] Why confine the matter to that part of the it involved in the Scriptures?” There is an echo of the “curse” of humankind from the second creation story in Genesis 2–3 (“Every precious gift to man is linked with a curse—and each pollution has some sparkle from heaven”)—the immediately following line/sentence mentions “angels,” “heaven,” and “serpents.” And then there is an extremely ugly reference to “Mordecai the Jew” (cf. Est 2:5: “there was a certain Jew, whose name was Mordecai”).

In the “Med Cophósis”90 notebook (1852–54) there is a set of three proverbial sayings that though unbiblical in content (with no specific allusions) imitate biblical diction:

Can a man be wise without he get wisdom from the books?

Can he be religious and have nothing to do with churches or prayers?

Can he have great style, without being dressed in fine clothes and without any name or fame?91

These sayings appear to be in prose—or at least they do not exhibit the kind of “hanging indentation” that typifies Whitman’s written verse in these notebooks (and eventually replicated in print in Leaves). The rendering in fact looks very much like the similarly prosaized proverbial sayings in the KJB.92 The use of such rhetorical questions is characteristic of the Bible’s proverbial wisdom (e.g., Job 6:6; 22:2; 36:29; Prov 6:27–28; 20:24; Mark 8:4; John 3:4). And indeed Prov 6:27–28 contains a short run of verses that sound very much like Whitman’s notations, though with different subject matter:

Can a man take fire in his bosom, and his clothes not be burned?

Can one go upon hot coals, and his feet not be burned?

In fact, the second verse could be translated even more literally (“Can a man,” JPS), as the Hebrew repeats ʾîš “man” from v. 27, which the KJB translators have altered (for stylistic and grammatical reasons) to “one.” There is also the run of “Canst thou” headed lines in the Yahweh speeches from Job (38:31–35; 39:1–2, 10, 20; 40:9; 41:1–2, 7).93 The pair “wise (man)”// “wisdom” appears nineteen times in the KJB (e.g., “Wisdom strengthens the wise,” Eccl 7:19).

From the “Poem incarnating the mind” notebook (1854),94 there is this trial line: “And wrote chalked on a great board, Be of good cheer, we will not desert you, and held it up as they to against the and did it.”95 The line is voiced by the “captain” of a rescue ship and is addressed to survivors of a ship wrecked by a storm. The phrase “Be of good cheer” is lifted directly from the gospels, Jesus’s words, also in the middle of a storm, “Be of good cheer; it is I; be not afraid” (Matt 14:27; Mark 6:50; cf. Matt 9:2; John 16:33).96 There is a reference to Adam and Eve and several to God, and then a more serious kind of imitation, or better, exaltation, where Whitman admits that “Yes Christ was Great large so was and Homer was great” and then affirms, “I know that I am great large and strong as any of them.” And: “Not even that dread God is so great to me as mMyself is great to me.— Who knows but that I too shall in time be a God as pure and prodigious as any of them.”97 The reference to “that dread God” (preceded by mention of Christ who “brings the perfumed bread”) makes clear that it is the biblical God that Whitman has chiefly in mind here. In “You know how” notebook (“before 1855”),98 there are also a few obvious biblical allusions: “the god that made the globe,” “reliable[?] sure as immortality pure as Jesus,” and “clear and fresh as the Creation.”99

In several of the 1854 notebooks distinct “echoes” of the Bible’s manner of saying things are heard. For example, in the “Memorials” notebook there is a sequence of didactic conditional statements in which the protasis and apodosis feature the same lexeme, viz. “If the general has a good army…, he has a good army,” “If you are rich… you are rich,” “If you are located… you are well located,” “If you are happy… you are happy.”100 The same trope shows up in Leaves, from both 1855 (“If the future is nothing they are just as surely nothing,” LG, 65) and 1856 (“If one is lost, you are inevitably lost,” LG 1856, 18). Compare Prov 9:12, “If thou be wise, thou shalt be wise for thyself,” and 1 Cor 14:38, “But if any man be ignorant, let him be ignorant.” And there is this analogous run from 1 Esdras (4:7–9):

…if he command to kill, they kill; if he command to spare, they spare; If he command to smite, they smite; if he command to make desolate, they make desolate; if he command to build, they build; If he command to cut down, they cut down; if he command to plant, they plant.

Also in the fourth of Whitman’s conditionals appears a typical Whitman tick: “but I tell you…” (e.g., “If you carouse at the table I say I will carouse at the opposite side of the table,” LG, 58). “I tell you” or “I say” commonly occur in the KJB (e.g., Isa 36:5; Ps 27:14; Eccl 6:3; Matt 5:18,20, 22, 26, 8; Luke 4:25; 13:3, 5, 27), and thus Whitman in (sarcastic) pantomime: “‘O Bible!’ say I ‘what nonsense and folly have been supported in thy name!’”101 And in “I know a rich capitalist” (1854)102 Whitman registers the following (complaint?): “Be thou you like the grand powers.”103 The phrase “be thou” appears some sixty-two times in the KJB, including, “be thou like a roe or a young hart” (Song 2:17).104 Here, too, Whitman can be seen scrubbing the archaic “thou” out of the phrase.

The “Talbot Wilson” notebook105 has a fair number of (possible) biblical echoes. It is littered with archaic diction (e.g., “thither,” “beget”/“begat”), for which the KJB would have been one readily available source. The syntax of much of the verse recorded here is beginning to take on the highly paratactic profile of the 1855 Leaves, another feature shared with the KJB (see Chapters Three and Five). And Whitman’s manner of phrasing often has a biblical ring to it. An example of the latter occurs in the following set of lines that appear by themselves on a single leaf:

DoHave you supposed it beautiful to be born?

I tell you, it I know, it is more just as beautiful to die;

For I take my death with the dying

And my birth with the new-born babes 106

The phrase “have ye” occurs some eighty-three times in the KJB, and “hast thou” some 147 times (both especially common in rhetorical questions), with this passage from Matthew being especially close to the sound, rhythm, and logic of Whitman’s lines:

Or have ye not read in the law, how that on the sabbath days the priests in the temple profane the sabbath, and are blameless? But I say unto you, That in this place is one greater than the temple…. For the Son of man is Lord even of the sabbath day. (Matt 12:5–6, 8)107

Tellingly, the biblical lilt of the notebook lines is entirely jettisoned in their published version:

Has any one supposed it lucky to be born?

I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it.

I pass death with the dying, and birth with the new-washed babe…. and am not contained between my hat and boots (LG, 17).

Whitman has removed the biblically sounding “Have you” (“has” [as opposed to “hast”] only occurs four times in the KJB) and “I tell you” and exploded the overall logic (no “For”) and rhythm of the lines, as well as their integrity as a distinct unit.

In a similar vein, there is a longish prose passage that is shaped on the underlying substructure of antithetical logic that informs so much of the parallelism in the biblical book of Proverbs: “The world ignorant man is demented with the madness of owning things—… —But the wisest soul knows that nothing no not one object in the vast universe can really be owned by one man or woman any more than another.—meddlesome[?] fool who who fancies that.108” Compare, for example, the following from Proverbs:

The wise shall inherit glory: but shame shall be the promotion of fools. (3:35)

The wise in heart will receive commandments: but a prating fool shall fall. (10:8)

The lips of the righteous feed many: but fools die for want of wisdom. (10:21)

It is as sport to a fool to do mischief: but a man of understanding hath wisdom. (10:23)

The way of a fool is right in his own eyes: but he that hearkeneth unto counsel is wise. (12:15)

Every prudent man dealeth with knowledge: but a fool layeth open his folly. (13:16)

The desire accomplished is sweet to the soul: but it is abomination to fools to depart from evil. (13:19)

The heart of him that hath understanding seeketh knowledge: but the mouth of fools feedeth on foolishness. (15:14)

A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth it in till afterwards. (29:11)

Even the biblical binary “wise man”/”fool” is clearly originally in view in Whitman’s “wisest soul” and the “meddlesome[?] fool.

Whitman’s holistic anthropology is already well developed in these notebook entries. For example, the couplet “I am the poet of the body/ And I am the poet of the soul” which will feature in the 1855 Leaves (LG, 26) makes its first appearance in this notebook.109 Although Whitman likely will have come to this holistic sensibility from various sources,110 it is worth stressing that in distinction to the New Testament (and much traditional Christian thought) the Hebrew Bible (like the ancient Semitic world more generally) exhibits a distinctly holistic anthropology as well—body and soul/mind are a unity and not at all dichotomous. Whether Whitman explicitly appreciated this fact is unclear to me,111 but the compatibility with his own thinking is patent112 and perhaps helps to explain Whitman’s assimilation of so much from the Hebrew Bible. And yet the KJB’s typical, hyper-literal translation of Hebrew nepeš as “soul” individuates and animates the concept in ways suggestive of Whitman’s many stagings of his “soul.”113 There are differences, of course. The KJB translators can imagine (no doubt because of their own assumptions about a bipartite anthropology) the psalmist in dialogue with his soul (e.g., Ps 3:2; 11:1; 16:2; 35:3; 42:5, 11; 43:5; cf. Luke 12:19), which Whitman mimics (“and I said to my soul When we become the god enfolders….”;114 cf. LG, 52) and then eroticizes, imagining his soul having sex with his body (LG, 15–16). In fact, there are several biblical inflections in this famous passage from the 1855 Leaves.115 Whitman’s soul-lover, who is addressed directly (“you my soul,” cf. Ps 16:2), “reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet” (LG, 16), an internally parallelistic and wonderful merism—from bearded head (top) to foot (bottom; cf. Song 5:10–16; 2 Sam 14:25)—that surely also must mean to play on “feet” as a biblical euphemism by which the “Hebrews modestly express those parts which decency forbids us to mention” (e.g., “uncover his feet,” Ruth 3:4).116 The “hand of God” (16x in the KJB; “hand of the LORD,” 39x)117 and the “spirit of God” (26x; “spirit of the LORD,” 31x) are common biblical phrases and the release that such handling brings is conveyed so as to echo Paul:118

Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and joy and knowledge that pass all the art and argument of the earth (LG, 15)

And the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus (Phil 4:7)119

As for the notebook couplet quoted above, not only is the animating thought characteristically Hebraic, but so too is the formal shaping of the lines—a parallelistic couplet made up of relatively short lines—it eventually is stretched into a typical, elongated and internally parallelistic Whitmanesque line: “I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul” (LG 1881, 45; see Chapter Four).

More specific allusions abound as well. There is a set of lines in which Whitman’s “I” encompasses that of Christ, on the cross and as incarnated in Whitman himself walking the streets of New York and San Francisco these some “two thousand years” later:

In vain were nails driven through my hands, and my head my head mocked with a prickly

I am here after I remember my crucifixion and my bloody coronation

The sepulchre and the white linen have yielded me up120

The I remember the mockers and the buffeting insults

I am just as alive in New York and San Francisco, after two thousand years

Again I tread the streets after two thousand years.121

These lines anticipate Whitman’s identification with Christ in “I celebrate myself” (LG, 43)—viz. “That I could forget the mockers and insults!”; “my own crucifixion and bloody crowning”; “I troop forth replenished”; “We walk the roads of Ohio… and New York… and San Francisco.” The allusive texture of the latter again is not as explicit as in the notebook entry, yet still the allusion remains clear.122

Dilation is one of Whitman’s “spinal ideas”123 and features prominently in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook. Two passages in that notebook contain trial versions of lines that eventually appear in “I celebrate myself” (LG, 45). The scene, as made clear in the first notebook rendition, is intended as an extended metaphor to show Whitman as “the poet of Strength and Hope,”124 whose poetry is life giving and restorative. The speaker rushes to the house of a dying man, seizes him, and raises “him with resistless will.” The speaker invites the “ghastly man” to “to press your whole weight upon me” and “With tremendous will breath,” the speaker says, “I force him to dilate.” The latter line gets further revised to “I [illeg.] dilate you with tremendous breath [illeg.],/ I buoy you up,”125 which is made into a single line in the 1855 Leaves: “I dilate you with tremendous breath…. I buoy you up” (LG, 45). Bergquist, commenting on the Leaves passage, recognizes that the Bible provides a number of striking parallels “where divine ‘breathing’ is said to fill with the power of life.”126 In particular, he cites Elisha’s restoring of the child of the Shunammite woman (2 Kgs 4:18–37), in which the prophet stretches himself on the boy’s body, puts “his mouth upon” the boy’s mouth and the boy “sneezes seven times” and opens “his eyes.” He also points to Gen 2:7: “And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”127 There are other potential parallels as well (e.g., John 11; cf. Ezek 37:5, 9–10).128 It seems likely, in fact, that Whitman is not here alluding to one particular passage but has an amalgam of such scenes in mind.129 If the specific mention of the “house of any one dying” and the image of “pressing” in the first notebook passage are especially suggestive of the Kings passage, the phrase “bafflers of hell” in the second notebook passage is more reminiscent of Luke 16:20–31, which involves the deaths of the beggar Lazarus and a rich man and is set in hell—where the rich man stays. And the revised version of this line, “bafflers of graves,” makes better sense in light of that other Lazarus in John 11, who is restored to life specifically out of a grave (vv. 17, 38, 43). At any rate, the notebook passages, with their more obvious biblical inflections (e.g., “Lo!”, “I saytell you”) and even a canceled out mention of God (viz. “God and I haveembraced you, and henceforth possess you all to ourmyselves”), would appear to support Bergquist’s intuition about the Bible supplying Whitman with the basic inspiration for the scene. Besides, as Miller observes, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, which might seem to the modern reader an obvious starting point for Whitman’s imagery, was not yet practiced at the time these lines were drafted in the notebook, and thus Miller, like Bergquist, references the Elisha story from the Bible.130

A last example comes near the end of the notebook on two successive leaves:

vast and tremendous is the scheme! It involves no less than constructing a state nation of nations.—a state whose integral state whose grandeur and comprehensiveness of territory and people make the mightiest of the past almost insignificant—and131

And:

Could we imagine such a thing—let us suggest that before a manchild or womanchild was born it should be suggested that a human being could be born—imagine the world in its formation—the long rolling heaving cycles—can man appear here?—can the beautiful animal vegetable and animal life appear here?132

The second of the passages features a typically “elusive” allusion to the creation stories in Genesis. This is cast within the century’s growing understanding of the Earth’s great age and so demythologized to some extent (esp. “the long rolling heaving cycles”). But the shift to first person plural voice (“could we,” “let us”), the gender inclusivity (esp. Gen 1:27: “male and female created he them”), “beautiful” as a descriptor, and the mention of “vegetable and animal life” all echo the creation accounts, especially in Genesis 1, and are prominent in other echoes of this material in Whitman’s writings, including in the 1855 Leaves.133 For example, in “I celebrate myself” occurs an echo of the Priestly writer’s closing assessment of God’s creation, ṭôb mĕʾōd “very good” (Gen 1:31): “The earth good, and the stars good, and their adjuncts all good” (LG, 17; cf. LG, 69—“what is called good is perfect”). And in “Who learns my lesson complete?” (LG, 92) Whitman speaks of “this round and delicious globe, moving so exactly in its orbit forever and ever” (the latter phrase appears 46x in the KJB), of which he says, “I do not think it was made in six days.” This is clearly an allusion to the Priestly version of creation in Genesis 1 (cf. “Nor planned and built one thing after another”). Whitman immediately goes on to mention the Bible’s trope of “seventy years” for the typical length of a well-lived life.

I wonder whether even the language of “manchild” and “womanchild” in the notebook passage, though chosen perhaps because of the resonance with “man” and “human being” elsewhere in the passage and because of the species emphasis of Whitman’s thought here, does not owe a debt to biblical diction. The former occurs some ten times in the KJB, including Job 3:3 (“Let the day perish wherein I was born, and the night in which it was said, There is a man child conceived”), a passage rich with cosmological imagery.134 The phrase “nation of nations” at the beginning of the first notebook passage certainly mimes the use of the periphrastic genitive made popular by William Tyndale in his intentionally close English renditions of the Hebrew superlative construction (a construct chain in Hebrew, viz. “God of goddes,” “lorde of lordes”; cf. Whitman’s “Book of books,” etc.; see Chapter Five for details)—a clear bit of biblicized English diction.135

Whitman’s unpublished poem, “Pictures,”136 which most date to sometime around 1855,137 fits well into the trajectory of the poet’s development leading up to the 1855 Leaves. As with the three 1850 poems and the verse experiments in the early notebooks, Whitman’s rhythms in this poem are distinctly non-metrical.138 His lines are consistently longer (as in the 1855 Leaves) than in the other pre-1855 poetic materials, and they are written here with Whitman’s characteristic “hanging indentation” (Fig. 11) as in the notebooks. No biblical quotations, but there are references to biblical figures and characters (e.g., Adam, Eve, Hebrew prophets, Christ, Lucifer). The two lines immediately preceding the line dedicated to Adam and Eve (from the second creation story in Genesis) focus day and night alluding to the first creation story in Genesis:

Whitman: “There is represented the Day” and “And there the Night”139

Genesis 1: “Let there be light: and there was light” (v. 3) and “And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night” (v. 5)

Whitman keeps the capitalization of the KJB to highlight the allusion and the biblical sequence of the two creation accounts (first the Priestly account of Gen 1:1–2:4a and then that of the Yahwist (or the non-Priestly source), the garden of Eden story of Genesis 2–3) is even emulated. Other specific scriptural allusions include those to the crucifixion narratives in the gospels (“the divine Christ” “en-route to Calvary”)140 and to Isa 14:12 (“the black portrait” of “Lucifer”),141 both allusions that Whitman makes elsewhere as well. The sequence of references in leaves 37–38 of “Pictures”—Adam and Eve, Egyptian temple, Greek temple, Hebrew prophets, Homer, Hindu sage, Christ, Rome, Socrates, Athens—represents the same basic litany of admired figures from antiquity discussed previously (in Chapter One), and is well evidenced in the early notebooks. There are even lines reminiscent of material from the early notebooks. For example, the image of Lucifer’s “black portrait” in “Pictures” (NUPM IV, 1300) appears again in a fragment cited by R. M. Bucke (“I am a hell-name and a curse:/ Black Lucifer was not dead”),142 both of which are preparatory for the related image in the 1855 Leaves (LG, 74; see discussion above). The trinitarian line about the “heads of three other Gods” (“The God Beauty, the God Beneficence, and the God Universality,” NUPM IV, 1301) has a striking parallel in the “I know a rich capitalist” notebook: “Yes I believe in the Trinity—God Reality—God Beneficence or Love—God Immortality or Growth.”143 And the language of “Hebrew prophets, chanting, rapt, ecstatic” (NUPM IV, 1297) is echoed in the “Poem, as in” manuscript fragment: “Poem, as in a rapt and prophetic vision.”144 “Pictures,” thus, patterns well with the early, pre-1855 notebooks and unpublished poetry manuscripts, demonstrating Whitman’s ongoing interest in and handling of the Bible.

“Pictures” is Whitman’s first long poem. As Allen notes, what Whitman needed at the time “was an adequate form, a literary vehicle,”145 and the long poem would become one of his chief poetic vehicles, especially in the earlier editions of Leaves. The poem itself conceptualizes Whitman’s mind and memory as a kind of picture gallery (the daguerreotype gallery then fashionable),146 a “(round) house” of images, personal and otherwise, stored up over a lifetime on whose “walls hanging” are “portraits of women and men, carefully kept” (NUPM IV, 1296), some of which (those with biblical allusions or characters) I have just briefly reviewed. The long poem—which aspires “to achieve epic breadth by relying on structural principles inherent in lyric rather than in narrative modes”147—is mostly a modern phenomenon. Indeed, Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is often credited as one of the more influential early instantiations of the modern genre.148 The surpassing length that characterizes such poems was expressly enabled by writing. The biblical poetic tradition emerges out of a predominantly oral culture,149 and therefore has no true long nonnarrative poems—Psalm 119, which is the most obvious exception (containing 176 verses), is itself an explicitly written poem, as the alphabetic acrostic that structures the psalm is a scribal trope, patterned after a common scribal practice genre, the abecedary. So there is no question of Whitman finding the long poem as such in the Bible.

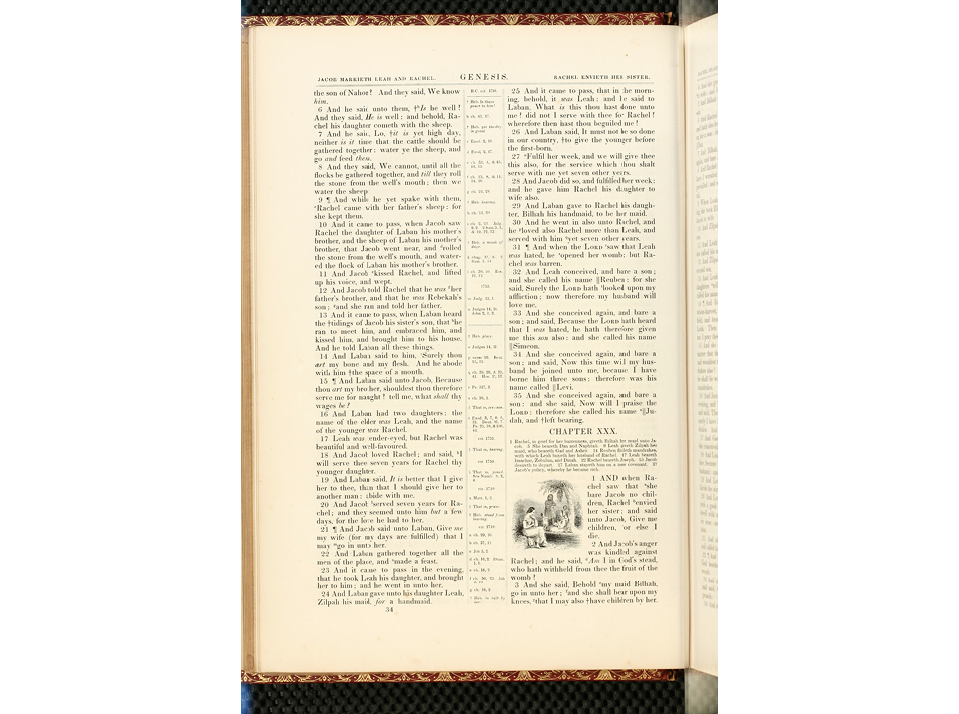

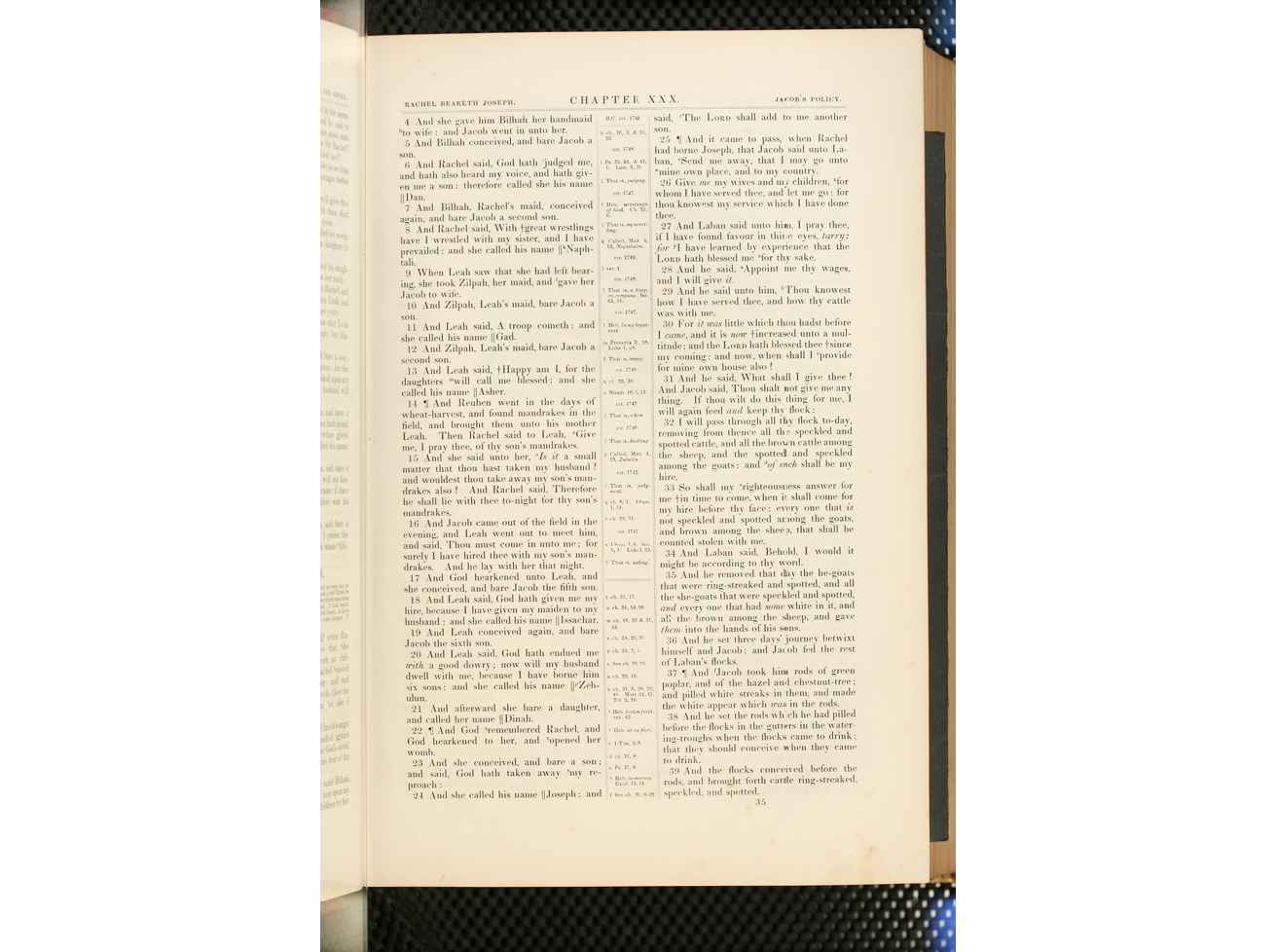

Fig. 11: From “Pictures,” holograph notebook (leaf 38r). Image courtesy of the Walt Whitman Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2007253.

However, this is not to discount totally the possibility of the Bible’s impress on Whitman even here. If there are no genuine long poems in the Bible for Whitman to imitate, nevertheless, the Bible (or portions thereof), especially in the prose translation of the KJB, could certainly be read in a fashion that could give rise to the idea of a long poem. One of the peculiarities of the page layout of the KJB (which it inherits in the main from the Geneva Bible) is that each verse (whether prose or poetry) is numbered separately and begins on a new indented line (see Figs. 4, 12). One consequence of such formatting is to occlude the distinction between the prose and poetry of the underlying Hebrew (in the Old Testament). From their look on the page one simply cannot tell the two apart (cf. Figs. 4, 13–17). As a practical matter, this uniformity at the “outer surface of Scripture,“observes R. G. Moulton (writing at the end of the nineteenth century), means that “the successive literary works appear joined together without distinction, until it becomes the hardest of tasks to determine in the Bible, exactly where one work of literature ends and another begins.”150

Fig. 12: Job 2:2–3:26 from the Harper Illuminated Bible. In the prose and page layout of the KJB it is often difficult to discern the shift from prose to poetry in the original Hebrew—Job 1–2 is prose, while Job 3 is poetry.

In the prose sections of the Bible (e.g., in the Torah) narrative prevails. But in long sections of the Bible’s nonnarrative poetry (e.g., Isaiah 40–55, Song of Songs) there is no narrative logic and no clear way to tell where individual poems begin and end, or even if there are individual poems. Which is to say that this poetry in the translation of the KJB can be read as large singular wholes, long runs of singular indented verses (of varying lengths)—so Whitman: “All its history, biography, narratives, etc., are as beads, strung on and indicating the eternal thread of the Deific purpose and power.”151 Intriguingly, Levine posits the Yahweh speeches from Job 38–41 as the “biblical prototype” for Whitman’s “list”-like catalogues of the “Song of Myself.”152 I might add, on the one hand, that the scale of the Joban poems (presumably the products of written composition) are themselves (individually and collectively) well matched to the scale of Whitman’s early catalogues; and, on the other hand, that the survey of human history from a single person’s perspective in “Pictures,” which offers a starkly contrasting perspective to that reported “out of the whirlwind,” epitomizes the post-Christian, secular antitype to biblical divinity revealed in Levine’s reading of “Song of Myself.”

Whether the KJB played a role in Whitman’s discovery of the long poem as his “literary vehicle” of choice, as exemplified embryonically in “Pictures,” is impossible to say. What is certain is that the KJB (a literary source well known to Whitman), because of its prosaic nature and genre-leveling page layout, contains page after page of runs of indented verse divisions in narrow columns that lend themselves (especially visually) to being read stichicly (as verse)—the look and feel are remarkably similar to the page layout of a typical nineteenth-century newspaper or even the visual display conveyed by the covered wall space in a daguerreotype gallery. Moreover, the fifty-two line-initial “And”s offer (collectively) another important pointer to the Bible, and especially to the prose portions of the Bible where they dominate especially in verse-initial position (because of the prominence of the main underlying Hebrew narrative form, the so-called wayyiqtol form, see Chapters Three and Five for details) and where the individual verses routinely stretch out in Whitmanesque proportions. Consider Gen 30:1–13 in the rendering of the KJB (Figs. 13–14). Twelve of the thirteen verses begin with “And” and are very reminiscent of several of the leaves from “Pictures,” which are also dominated by runs of line-initial “And”s (see Fig. 11). Note that it is Whitman’s use of the conjunction in “Pictures” that distinguishes his poetic renderings from his similarly posed journalistic descriptions of portraits in a daguerreotype gallery.153 Allen even notices that the “rhythms” in “Pictures” are “simply those of prose.”154 Such prosiness is sensible from several angles, but especially if the source of inspiration, whether in the Bible or Whitman’s own journalism, is itself prosaic in nature (see further Chapter Five). In short, read holistically and grossly in the English translation of the KJB, the Bible (especially in certain stretches) looks very much like a Whitmanian long poem (or “cluster” of such long poems).

Fig. 13: Gen 29:5–30:3 from the Harper Illuminated Bible.

Fig. 14: Gen 30:4–39 from the Harper Illuminated Bible.

There are a number of surviving preliminary drafts of lines (or blocks of lines) for Leaves that stand between the trials of the early notebooks and the versions published in 1855. On occasion these, too, reveal biblicisms. Some examples by way of illustration may be offered from proto-versions of “I celebrate myself.”155 In “I call back blunders,” there is this line that Whitman never publishes: “I give strong meat in place of panada.”156 The “strong meat” is the KJB’s translation of Greek στερεὰ τροφή from Heb 5:12 and 14, which references solid food (as opposed, for example, to milk, or as Whitman has it, “panada”—a kind of bread soup). In both of the biblical verses the image is applied figuratively as a trope for teaching, knowledge, the capacity to reason—very much akin to Whitman’s usage. In a manuscript leaf from Duke University, “I know as well as you that Bibles are divine revelation,” Whitman references “God” (3x), “the Lord,” “Jehovah,” and possibly “Adonai.”157 These are all quite specifically references to the God of the Bible, and especially the Hebrew Bible (or Old Testament). “Jehovah” and “Adonai” are each used once in Leaves, in the section the manuscript leaf appears to be working towards (LG, 45). The phrase “the Lord”—with definite article and capitalization—appears twice in Leaves (LG, 15, 84). And “God”—capitalized and not canceled—occurs fully twenty-four times in Leaves (LG, v, vi, viii, xi, 15 [2x], 16, 29, 34, 38, 45, 50, 51, 53, 54 [9x], 95). And there are a number of phrases, like the “hand of God” and “spirit of God” discussed earlier, that are either biblical or sound biblical: “By God!” (LG, 29, 45) when swearing an oath (Mark 5:7; cf. Gen 21:23; 1 Sam 30:15; 2 Chron 36:13; Neh 13:25; also frequently “by the Lord,” e.g., 1 Kgs 1:30); “orchards of God” (LG, 38) sounds very much like a play on and broadening of the idea of Eden, the “garden of God” (Ezek 28:13; 31:8, 9); “And I call to mankind, Be not curious about God” (LG, 54)—this has the feel, shape, and even punctuation (manner of embedding direct discourse) of a saying of Jesus (e.g., “Then said Jesus unto them, Be not afraid,” Matt 28:10) or a prophet (e.g., “And Isaiah said unto them, Thus shall ye say unto your master, Thus saith the LORD, Be not afraid of the words…,” Isa 37:6);158 “In the faces of men and women I see God” (LG, 54)—“yet in my flesh shall I see God” (Job 19:26); and “before God” (LG, 95; 48x in KJB). From the Duke University manuscript, “a revelation of God” is close to similar New Testament idioms, such as “revelations of the Lord” (2 Cor 12:1) or “revelation of Jesus Christ” (Gal 1:12; 1 Pet 1:13; Rev 1:1). And the mention of “the Bibles,” capitalized and pluralized with the canceled definite article, shows Whitman in the process of deconstructing (and democratizing) the otherwise very particular connotation of this term in English (i.e., “THE BOOK… the sacred volume, in which are contained the revelations of God,” Webster, American Dictionary [1852], 102) and anticipating his twofold usage of “bibles” (generalized, pluralized, and not capitalized) in the 1855 Leaves (LG, 29, 60).