3. Whitman’s Line: “Found” in the King James Bible?

©2024 F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0357.04

Perhaps the likeness which is presented to the mind most strongly is that which exists between our author and the verse divisions of the English Bible, especially in the poetical books

— G. Saintsbury, review of 1870–71 Leaves of Grass (1874)

“Since Leaves of Grass was first published,” observes M. Miller, “readers have often assumed that Whitman developed his line from the Bible.”1 This is a startling observation. Yes, there has been a long-running interest in the more general topic of Whitman and the Bible, but the line only very rarely comes in for specific comment. For example, R. Asselineau in The Evolution of Walt Whitman: An Expanded Edition does remark that Whitman’s long verses “recall above all the Bible,” though without further elaboration or substantiation.2 And I return below to one of the early reviews of Leaves and what is perhaps the most probative perception about Whitman’s line as it relates to the Bible. But in fact such observations specifically about Whitman’s line are not so numerous, and nothing overly detailed, let alone evidence for a continuous and incisive scholarly debate on the topic. In the chapter that follows, then, I propose to undertake such an inquiry, a probing of the proposition that “Whitman developed his line from the Bible.” Once focused on the principal site of textual encounter, the King James Bible, I point to a number of ways in which that Bible may have played a role in shaping Whitman’s ideas about his mature line, its length(s), familiar shapes, contents, and even in places its very staging. Yet as with so much of Whitman’s collaging, the finding is only part of the art. Here, too, what (of the line) Whitman finds is typically worked and reworked such that the finding itself can get obscured and what is made in the process indubitably is made distinctly his own.

The Development of Whitman’s Long Line: A Chronology

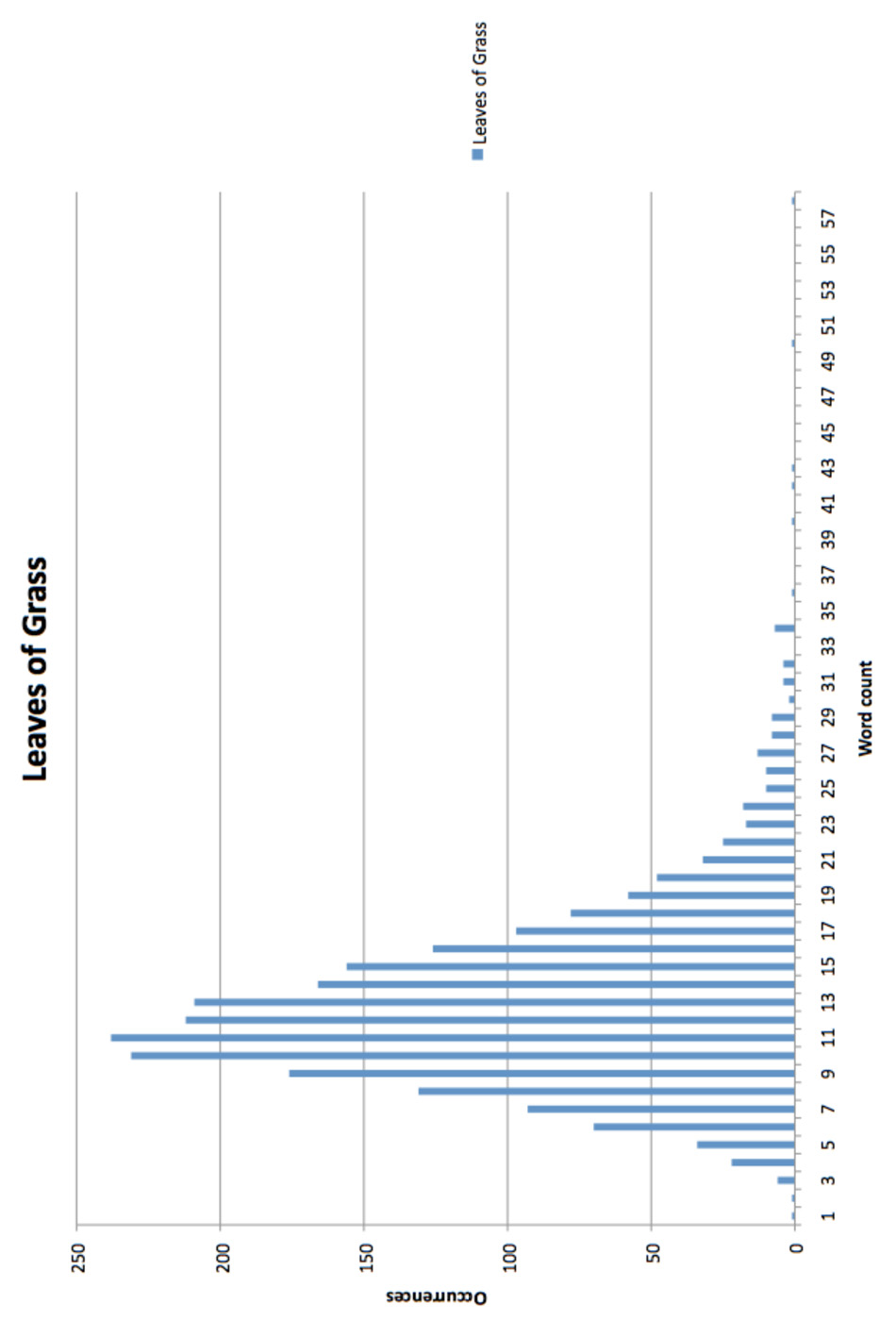

Before turning to my topic in earnest, however, I sketch the chronological development of Whitman’s long line as currently understood. The renewed attention paid to the early notebooks and poetry manuscripts—stimulated in part by the recovery in 1995 of some of the notebooks that had been lost by the Library of Congress during the Second World War3—has enabled scholars to see much more clearly the emergence of that line and to have a better idea of its rough chronology. Presently, the three poems published in the spring and summer of 1850—“Blood-Money,”4 “The House of Friends,”5and “Resurgemus”6—appear to be the last poems (with line-breaks) Whitman composed prior to the trial lines found in the earliest extant notebooks, most of which date from between 1852 and 1854.7 The break with meter in 1850 turns out to be decisive for the development of Whitman’s line as it unshackles the major constraint on line-length and opens the way to using lines of varying lengths according to the requirements of clause or sentence logic.8 A majority of the lines in the three poems remain of conventional lengths. Emblematic of this is the fact that in the case of “Resurgemus,” Whitman often simply combines two (or more) lines to make a single (long) line in the revised version of the poem included in the 1855 Leaves, e.g., “But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter destruction,/ And frightened rulers come back:” (“Resurgemus”; eight words/ five words) => “But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter destruction, and the frightened rulers come back:” (LG, 88; fourteen words).9 Crucially, though, the lengths of the lines vary (however modestly) in these poems, and some stretch out beyond the eight-word limit that characterizes much of Whitman’s earlier metered verse: “Blood-Money” has the most lines eight words in length or longer, eleven (e.g., “Where, as though Earth lifted her breast to throw him from her, and Heaven refused him,” line 7; sixteen words);10 “House of Friends” has five such lines (e.g., “The shriek of a drowned world, the appeal of women,” line 28; ten words); and “Resurgemus” three (e.g., “Suddenly, out of its state and drowsy air, the air of slaves,” line 1; twelve words). None of these “long” lines attain the extended reach of Whitman’s longest lines in the 1855 Leaves, but they all fall squarely within the sweet spot for line-length in that volume, which is from eight to sixteen words per line. Lines of these lengths each occur more than a hundred times and account for 1,641 lines in total—71% of all the lines in the 1855 Leaves (see Fig. 15). Already in these initial free-verse efforts, then, Whitman has found the lineal scale that will carry much of his verbiage in the early Leaves.

Fig. 15: Line lengths by word count for the 1855 Leaves. Computation and chart by Greg Murray.

In the spring of 1851 in his “Art and Artists” lecture, Whitman is still content to quote lines from “Resurgemus” as originally crafted.11 Of the eighteen lines quoted, only one numbers more than eight words (“They live in brothers, again ready to defy you,” nine words, UPP I, 247). In the recombined version of these lines from the 1855 Leaves, the overall number of lines is reduced to ten, and eight of these tally nine or more words, including the nineteen-word “Not a grave of the murdered for freedom but grows seed for freedom…. in its turn to bear seed” (LG, 88). The percentage of lines of conventional lengths (eight or fewer words) in the 1855 Leaves is still smaller, amounting to roughly 15% of the total number of lines (354 lines, see Fig. 15).

Trial verse lines appear in at least four of the pre-Leaves notebooks. The “med Cophósis”notebook is perhaps the earliest of these, with most dating it between 1852 and 1854.12 Only two long leaves survive, and there is just one set of obvious verse lines, material that anticipates the opening of “Who learns my lesson complete?” (LG, 92–93):

My Lesson

Have you learned the my lesson complete:

It is well—it is but the gate to a larger lesson—and

And that to another;: still

And every one opens each successive one to another still13

Of the four original lines started here, only the second is long, containing twelve words.14 Whitman’s deletions and additions in lines 2–3 create the equivalent to the “hanging indentation” that appears in the holographs of other notebooks for rendering the continuation of long lines onto the next manuscript line. This lengthens the line to sixteen words. It also shows Whitman in the process of combining lines, much like what must be assumed, for example, to have taken place in his revisions of “Resurgemus.” Interestingly, Whitman settles on a different combination in the 1855 Leaves, going back to the original substructure and working it out differently:

Who learns my lesson complete?

….

It is no lesson…. it lets down the bars to a good lesson,

And that to another…. and every one to another still. (LG, 92)15

The last line quoted here is a combined version of lines 3–4 from the notebook fragment, stretching the line to ten words.16 While the sample size is statistically irrelevant, the four notebook lines share the same basic profile as found in the 1850 poems.

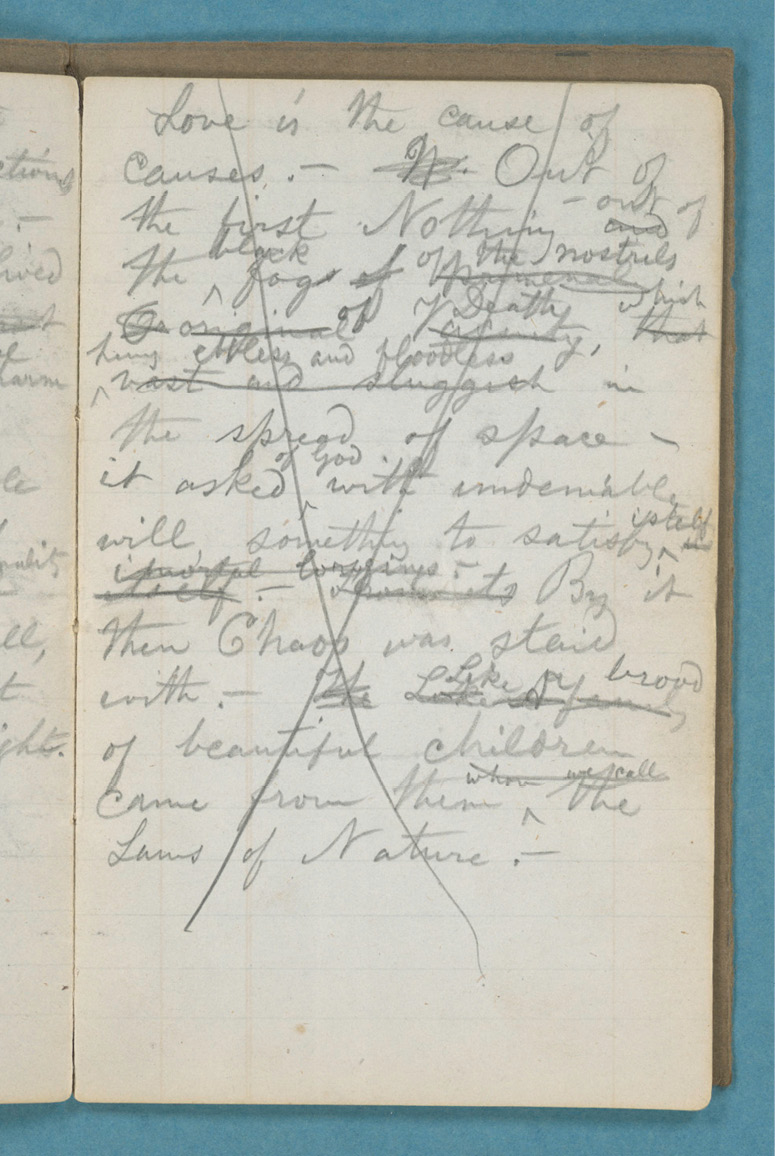

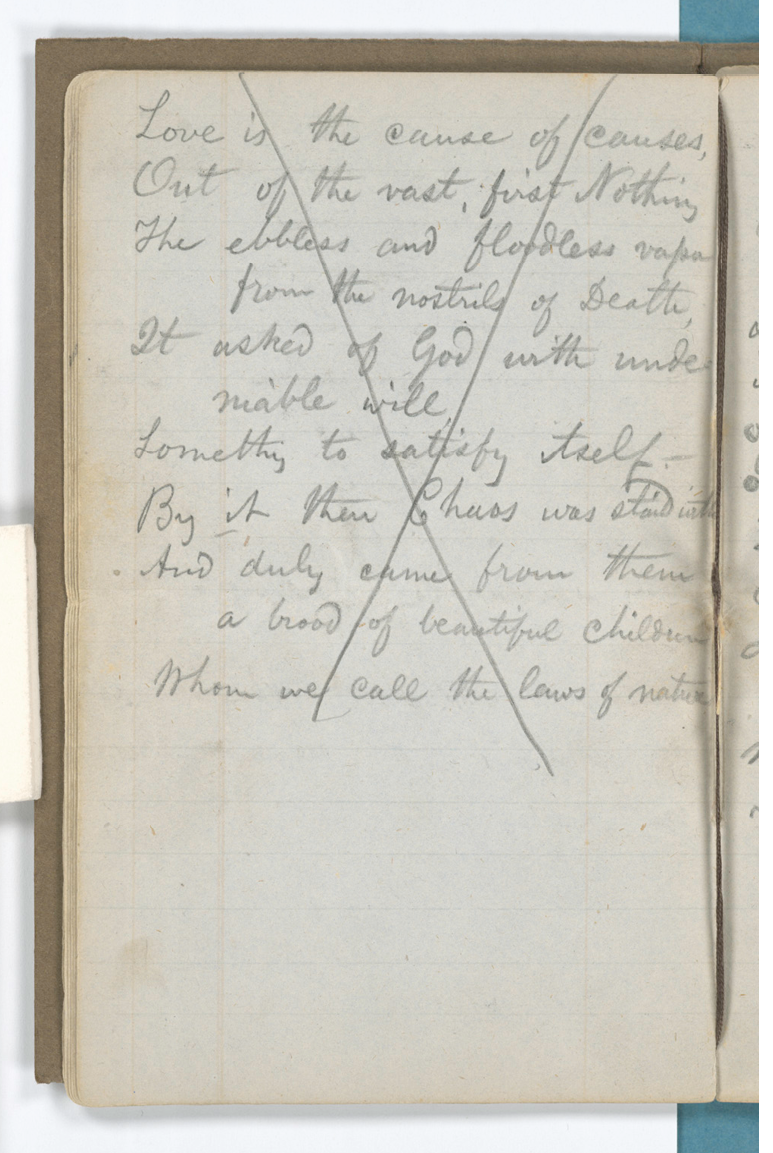

“I know a rich capitalist” is usually dated to 1854 like most of the remaining early notebooks.17 Again, there is only one set of verse lines in this notebook. Of the eight lines of verse written out, only two are long (eleven and ten words in length). The profile—lines of variable lengths, mostly short and none that are really long—here, too, is suggestive of the 1850 poems.18 Moreover, these lines were clearly culled from a passage of prose inscribed earlier in the notebook. Intriguingly, on seven occasions the clausal phrasing of the prose version is circumscribed by long dashes. One of the dashes comes at the end of the passage. Of the other six, five head material that is broken into distinct verse lines in the poetic version (Figs. 16–17). This use of dashes is most reminiscent of Whitman’s long riff on Genesis 1 at the beginning of the “Art and Artists” lecture discussed in Chapter One—only here a versified version also exists.19

Two other early notebooks, the “Poem incarnating the mind” notebook20 and the famous “Talbot Wilson” notebook,21 preserve many more lines of trial verse than the two notebooks just discussed. The prevailing line profile in these notebooks is noticeably different. Short lines (eight or fewer words) and long lines (nine to sixteen words in length) appear in almost equal proportions, with long lines being slightly more numerous in each notebook. Moreover, for the first time each notebook preserves lines of seventeen words or more: “Poem incarnating the mind” has four such lines (e.g., “And in that deadly sea waited five How they gripped close with Death there on the sea, and gave him not one inch, but held on days and nights near the helpless fogged great wreck”; twenty-two words; all canceled)22 and “Talbot Wilson” has nine (e.g., “I will not have a single person left out…. I will have the prostitute and the thief invited…. I will make no difference between them and the rest”; twenty-seven words; all canceled).23 And most of the short lines actually number between six and eight words in length. In fact, the majority of lines in these notebooks range between six and eighteen words in length, as also in the 1855 Leaves (roughly 86% of the lines in the latter are of these lengths, see Fig. 15).

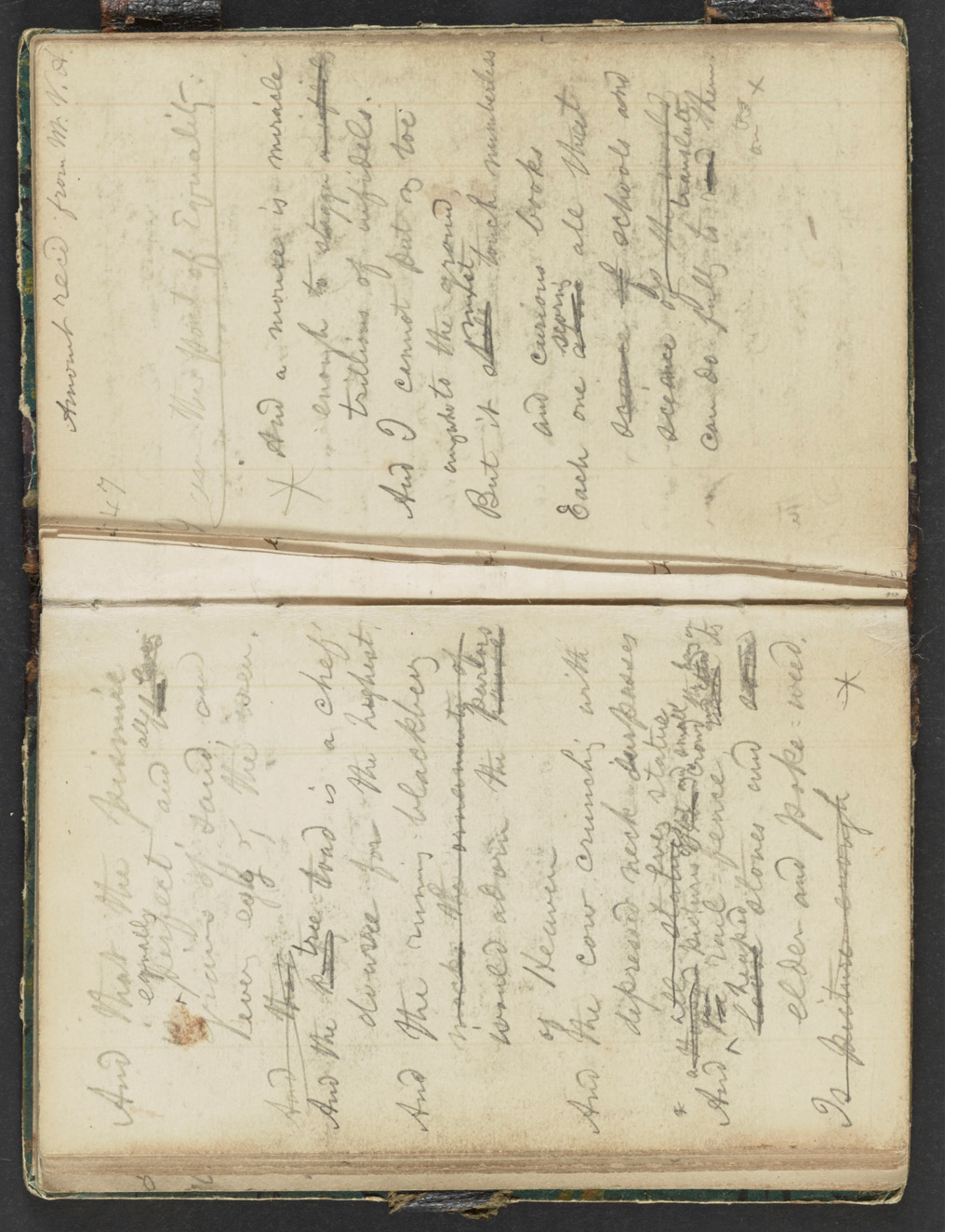

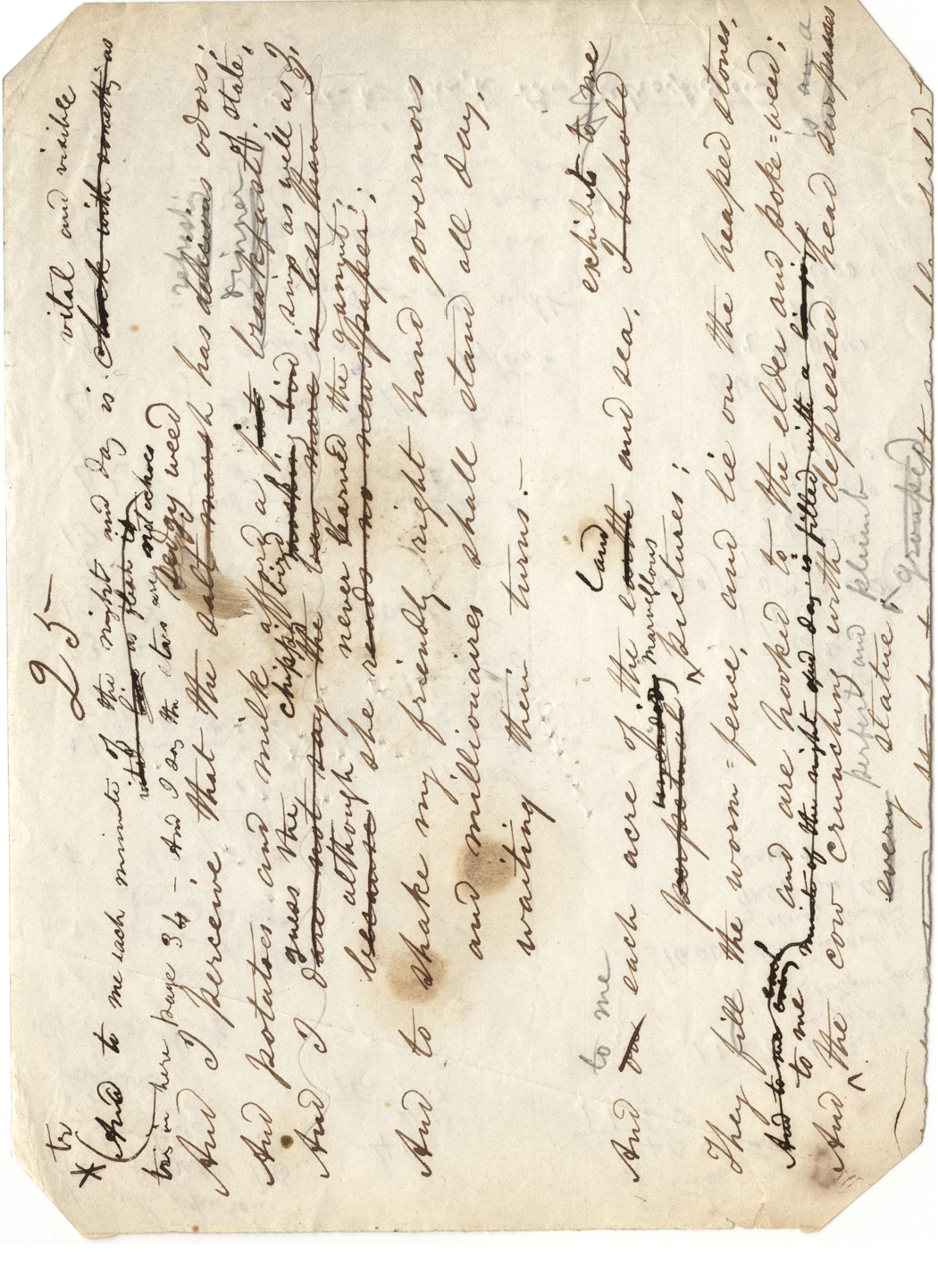

Fig. 16: Leaf 6r from the “I know a rich capitalist” notebook, https://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/figures/nyp.00129.011.jpg, showing the prose version of the “Love is the cause of causes” passage. Image courtesy of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library.

Fig. 17: Leaf 7v from the “I know a rich capitalist” notebook, https://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/figures/nyp.00129.014.jpg, showing the verse version of the “Love is the cause of causes” passage. Image courtesy of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library.

There is one last pre-Leaves notebook that may contain verse lines, the “Autobiographical Data” notebook.24 The notebook appears to have been used over an extended period of time (1848–55/56).25 Unfortunately, the original notebook itself is missing, and the passage (material set out in enumerated sections) that some identify as poetry26 is not preserved in the extant set of (incomplete) photostats—the transcription of this material is dependent on E. Holloway’s edition.27 It is not obvious that (all of) this material is verse (e.g., Grier refers to the numbered sections as “paragraphs,” NUPM I, 212, n. 16)28 and the date of composition cannot be narrowed beyond the range posited for the entire notebook. If the passage is verse, it does not closely resemble “the poetry of 1855–56.”29 There could be as many as fourteen complete lines. Most range in length between seven and eighteen words; there are three longer lines of twenty-one (2x) and thirty-four words. Obviously, much uncertainty remains regarding this material.30

Surviving drafts of proto-versions of lines for the 1855 Leaves appear to stand between the early notebook trials and their published versions. For example, E. Folsom has collected a number of the holographs that anticipate “I celebrate myself” from several university collections.31 Long lines clearly prevail in these manuscripts—more than two-thirds of the lines are long. Yet proportionately short lines still occur twice as often as they do in the 1855 Leaves. Not infrequently, shorter lines in these manuscripts get combined in their published version, as with the revision of “Resurgemus.” The following are illustrative:

|

For I take my death with the dying And my birth with the new-born babes 32 |

|

|

For I take my death with the dying, |

|

|

I pass death with the dying, and birth with the new-washed babe…. and am not contained between my hat and boots, |

|

|

You there! impotent loose.. the knees! Open you mouth gums, my [illegible] that I put send blow grit in you with one a [illegible]th33 |

|

|

You there, impotent, loose in the knees, open your scarfed chops till I blow grit within you, |

|

|

3. “Talbot Wilson”: |

I will am not to be denied—I compel; *I have stores plenty and to spare34 |

|

“You there”: |

I am not to be denied—I compel; I have stores plenty; and to spare;35 |

|

I am not to be denied…. I compel…. I have stores plenty and to spare, |

|

|

190 You villain, Touch! what are you doing? |

|

|

You there, impotent, loose in the knees, open your scarfed chops till I blow grit within you, |

Examples like these suggest that such combining of shorter lines to make longer lines was especially characteristic of the latest stage(s) of Whitman’s composition of the first edition of Leaves of Grass. The lineal profile of the latter shifts yet again. Whitman’s long lines in the 1855 Leaves continue to stretch out, and their numbers are even greater. Sometimes the expansion in length is striking, as witnessed above in Whitman’s combinatory collaging of shorter lines to make long lines, and sometimes it is more incremental. A good example of the latter is the following line, which accumulates more words in each version:

“Talbot Wilson”: I tell you it I know it is more just as beautiful to die; (twelve words)36

“taken soon out of the laps”: I tell hasten to inform you it is just as good to die;, and I know it; (sixteen words)

LG,17: I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it. (eighteen words)

Almost 85% of the lines in the 1855 Leaves are long (65.3%) or really long (19.4%). Short lines persist, as they have from the beginning. For example, “Those corpses of young men” is among a handful of short lines from “Resurgemus” that stays unchanged (un-lengthened) from its first publication in 1850 through to the final lifetime edition of Leaves (LG 1881, 212). However, the number of such short lines decreases dramatically, accounting for just better than 15% of the lines in the 1855 Leaves.37 Whitman’s unpublished long poem, “Pictures,” which most date to sometime around 1855,38 mainly features long lines, with only a very few short lines (less than 5%).39

In sum, while Whitman’s long line is birthed immediately in his break with metrical verse, the basic trajectory of line usage in the run-up to the 1855 Leaves is one of increasing preference for long (and really long) lines matched by decreasing dependence on short lines. The latter persist throughout but in ever decreasing numbers. Really long lines steadily increase (in number and scale), eventually overtaking the number of short lines in the 1855 Leaves. From the time of the “Poem incarnating the mind” and “Talbot Wilson” notebooks, lines of between nine and sixteen words in length dominate Whitman’s verse exercises and published poems. Still, throughout this period Whitman’s line remains strikingly variable and fluid in terms of length. In fact, though many lines settle into canonical shapes for Whitman, many others will continue to vary (and at times disappear completely) in succeeding editions. Long lines continue to be added in the next two editions of Leaves, though the trend towards a favoring of foreshortened lines that marks much of Whitman’s poetry after 1865 already begins in these earlier editions. Whitman’s “finding” of his long line on this view is decidedly processual in nature. After becoming a possibility, it emerges over time in Whitman’s “many MS. doings and undoings,” stretching out, reconfiguring, even contracting when needed as the poet molds his line to fit his sentences.

G. W. Allen, Parallelism, and the Biblical Poetic Line

Of the two studies that Miller recognizes as having explored the connection between Whitman’s line and the Bible “perhaps most definitively,” only G. W. Allen truly takes up the topic of the line, and that not without problems.40 The engine that drives Allen’s analysis is parallelism, which he takes as the first rhythmical principle of the English Bible and which he understands chiefly according to Robert Lowth’s system (as mediated by various secondary discussions).41 This emphasis would seem to be well put, for as G. Kinnell observes, “Whitman is no doubt the greatest virtuoso of parallel structure in English poetry.”42 But in order to unravel Whitman’s understanding and use of parallelism, Allen well appreciated that he had to first give attention to the line: “the line is the unit, ‘the second line balancing the first, completing or supplementing its meaning.’”43 This is Allen quoting J. H. Gardiner about biblical verse. A few pages later he turns to Whitman, making the same point: “The fact that the line in Leaves of Grass is also the rhythmical unit is so obvious that probably all students of Whitman have noticed it.”44 Miller, more recently, underscores just how crucial the development of his poetic line was to Whitman: “In fact his [Whitman’s] notebooks suggest that it [his line] was probably the single most important factor in accelerating his development.”45 And even more emphatically a bit later: “if one event can be described as his strictly creative catalyst, judging from the notebooks it would seem to be his realization of new ways of composing derived from his discovery of his line.”46 What is “so obvious” for students of Whitman, or indeed students of poetry more generally, has only rarely been noticed of biblical poetry. To date, in fact, there has been little substantive appreciation of the verse line and its significance in biblical verse—aside, that is, from issues of syntax (which is not an insignificant matter).47 This is a considerable desideratum given that the line by most accounts is the leading differentia of verse—“the only absolute to be drawn,” writes T. S. Eliot, “is that poetry is written in verse and prose is written in prose.”48 Allen’s observation is astute and goes to the heart of many issues concerning biblical poetry. It warrants the attention of biblical scholars.

However, the line is also a matter Allen muddles considerably. He is very deliberate in setting up the parameters of his research. The English Bible, by which he means above all the King James Bible,49 is the paramount focus of his comments—“I am not concerned here with the Hebrew verse.”50 This is entirely reasonable since Whitman did not know biblical Hebrew,51 and therefore whatever sense he may have had of biblical poetics would have been mediated through translation (and whatever secondary discussions he may have encountered), above all through the KJB. But, of course, quite famously, the KJB is a prose translation of the Bible, including of those portions that are verse (e.g., Psalms, Proverbs, Job, etc.) and that were known to be verse by King James’s translators—and indeed by scholars generally well before that period.52 The trouble for Allen is twofold. First, the understanding of parallelism that he borrows and deploys in his analysis of Whitman and Whitman’s putative use of biblical analogs is a theory derived and elaborated with the Hebrew text of the (Hebrew) Bible in view. It is, in other words, a theory about biblical Hebrew poetry. How well that theory may illuminate a translation of the underlying Hebrew is an open question that depends greatly on the nature of the translation and translation technique. The translation of the KJB, for example, may surely be used when illustrating the role of parallelism in biblical verse, and may even show off some aspects quite spectacularly, such as the (semantic) synonymity that often accompanies the Hebrew Bible’s parallelistic poetic play—so Allen: “at least in the English translation this rhythm of thought or parallelism characterizes Biblical versification.”53 But this still has the underlying Hebrew as its ultimate target. It is a different matter altogether when the translation itself becomes the target of analysis. In other words, Allen does not pay enough attention, especially initially, to the interference and turbulence caused by translation, to the fact that translation does not offer a transparent view of the translated. There is a mismatch between his theory and the source(s) of his theory, all of which have the Hebrew in view, and his own application to an English prose translation of biblical Hebrew verse.

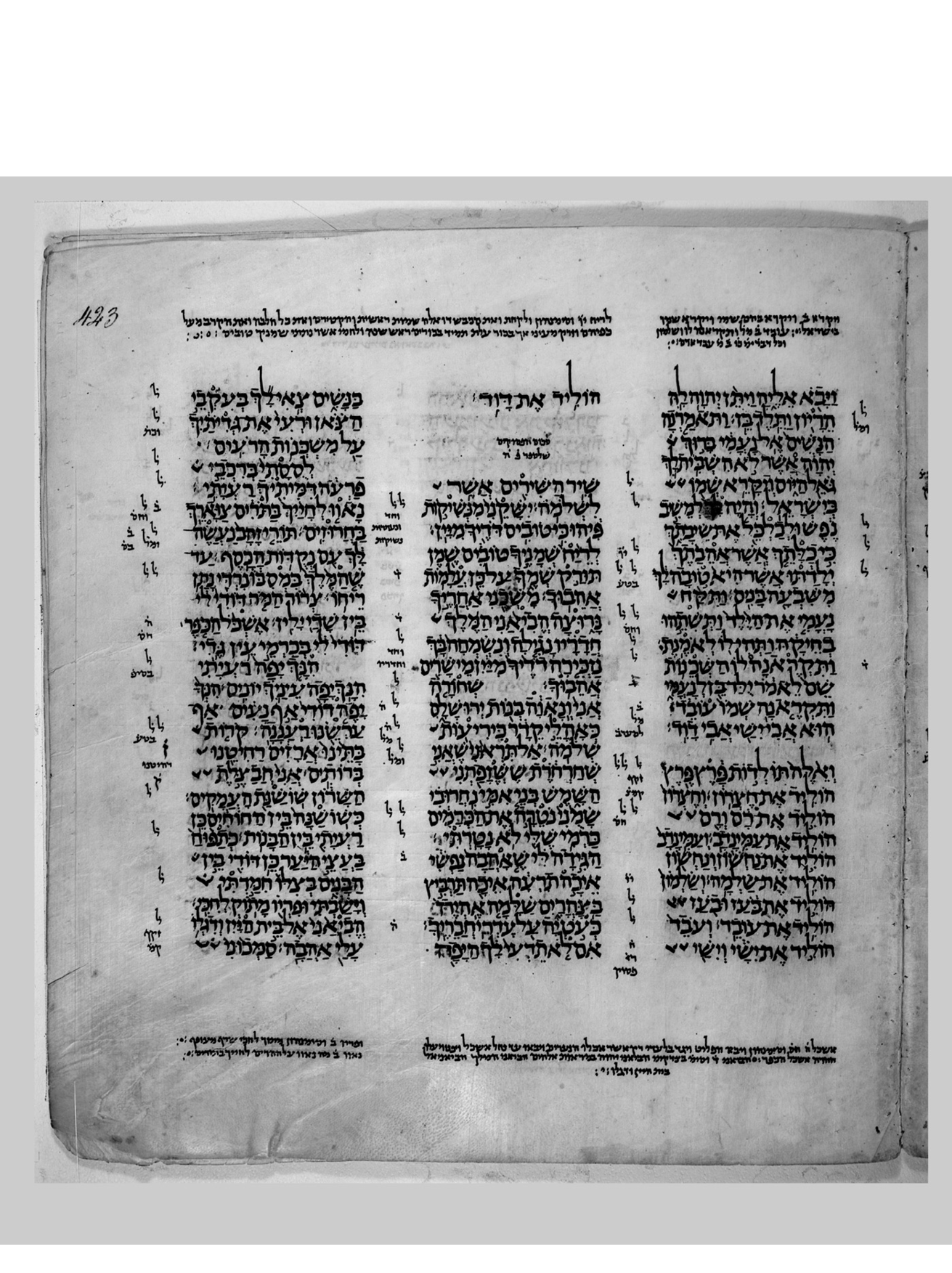

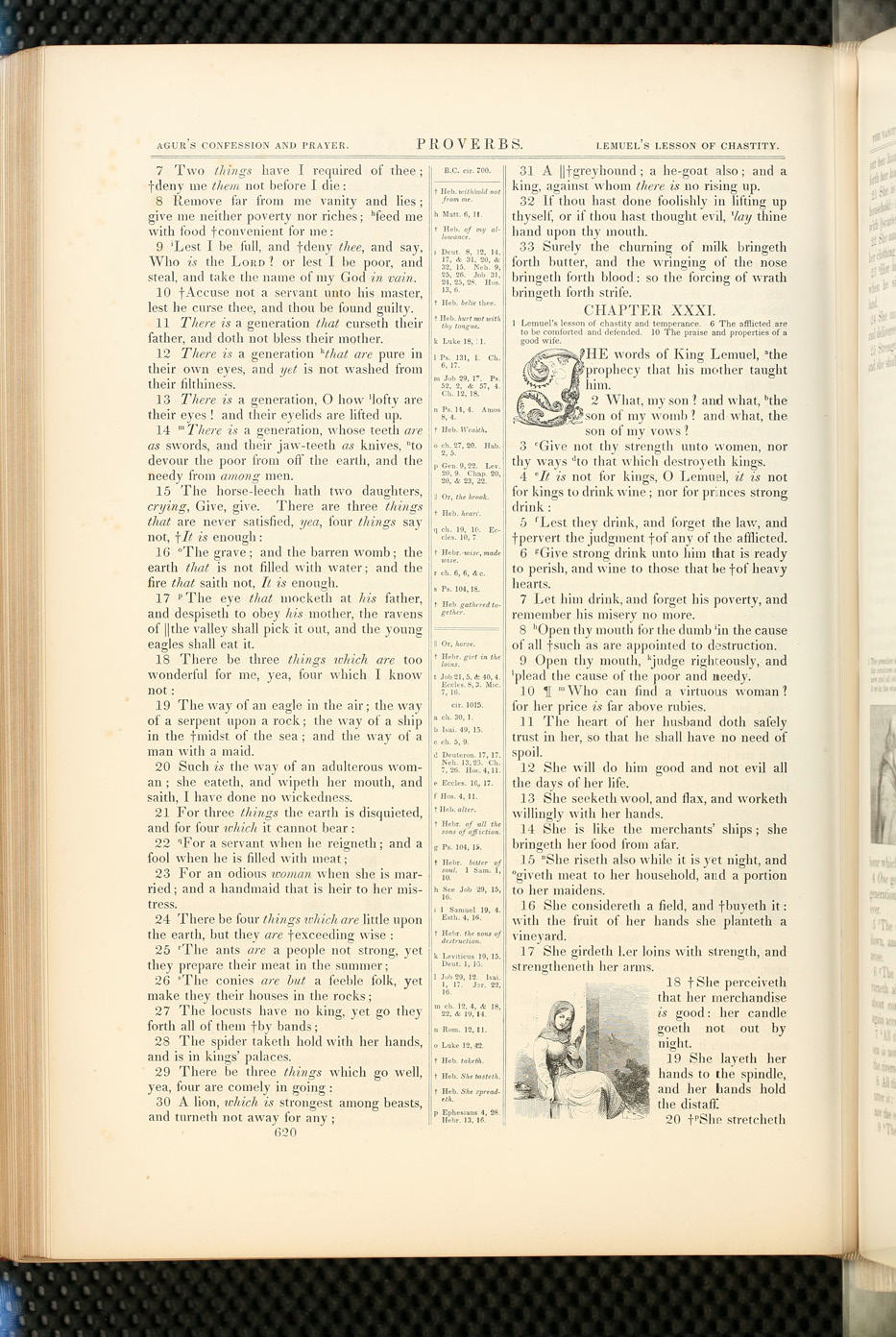

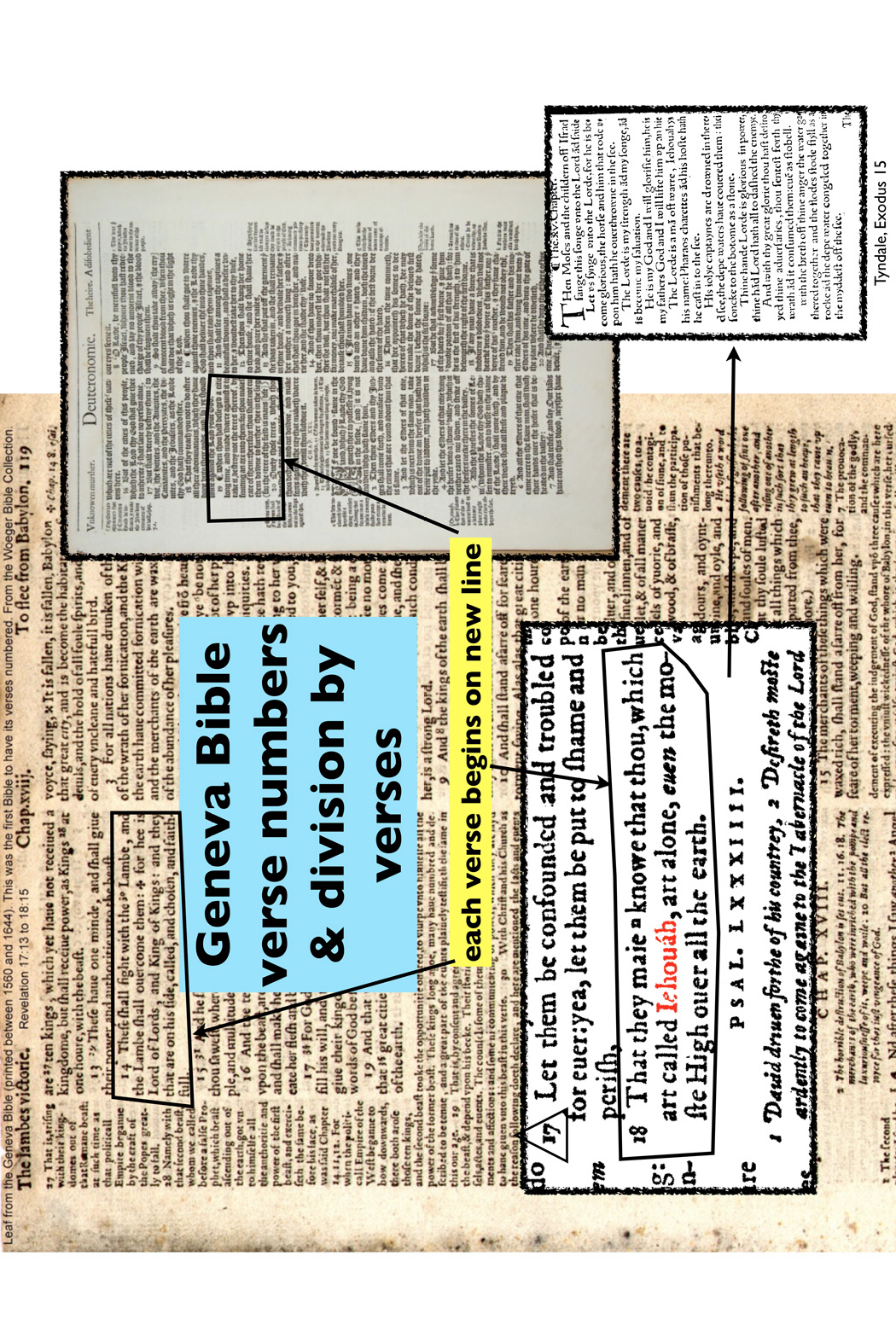

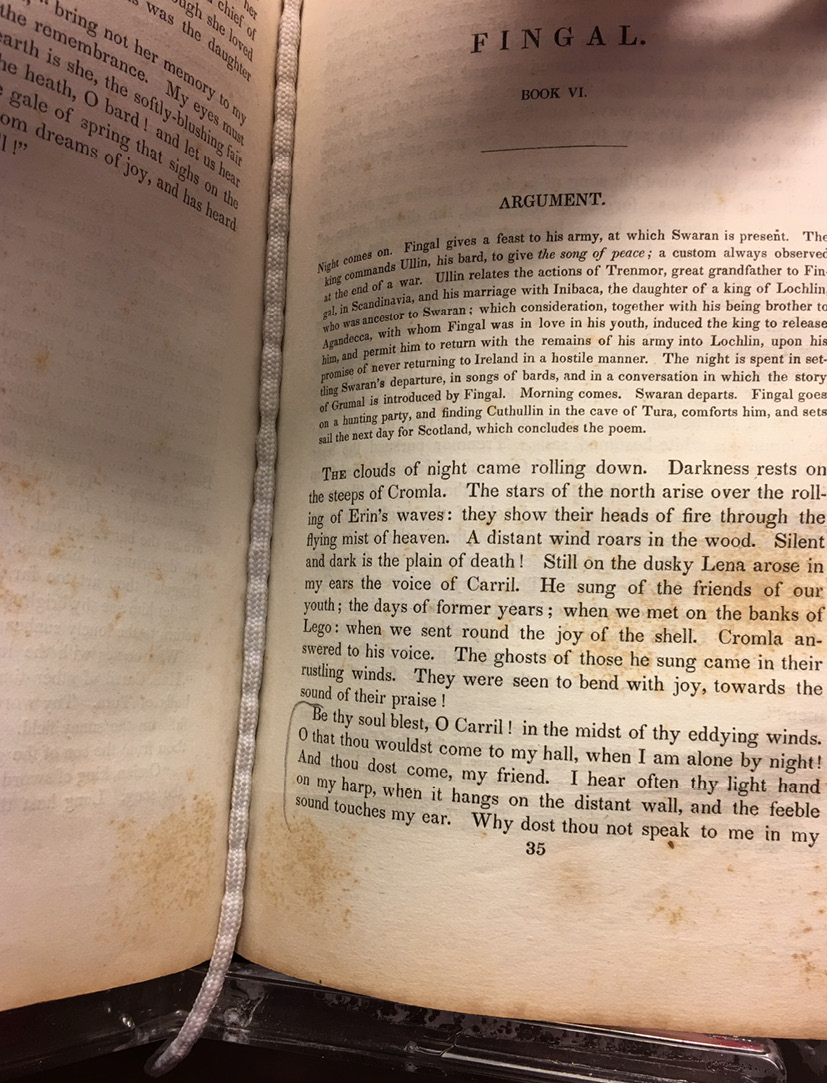

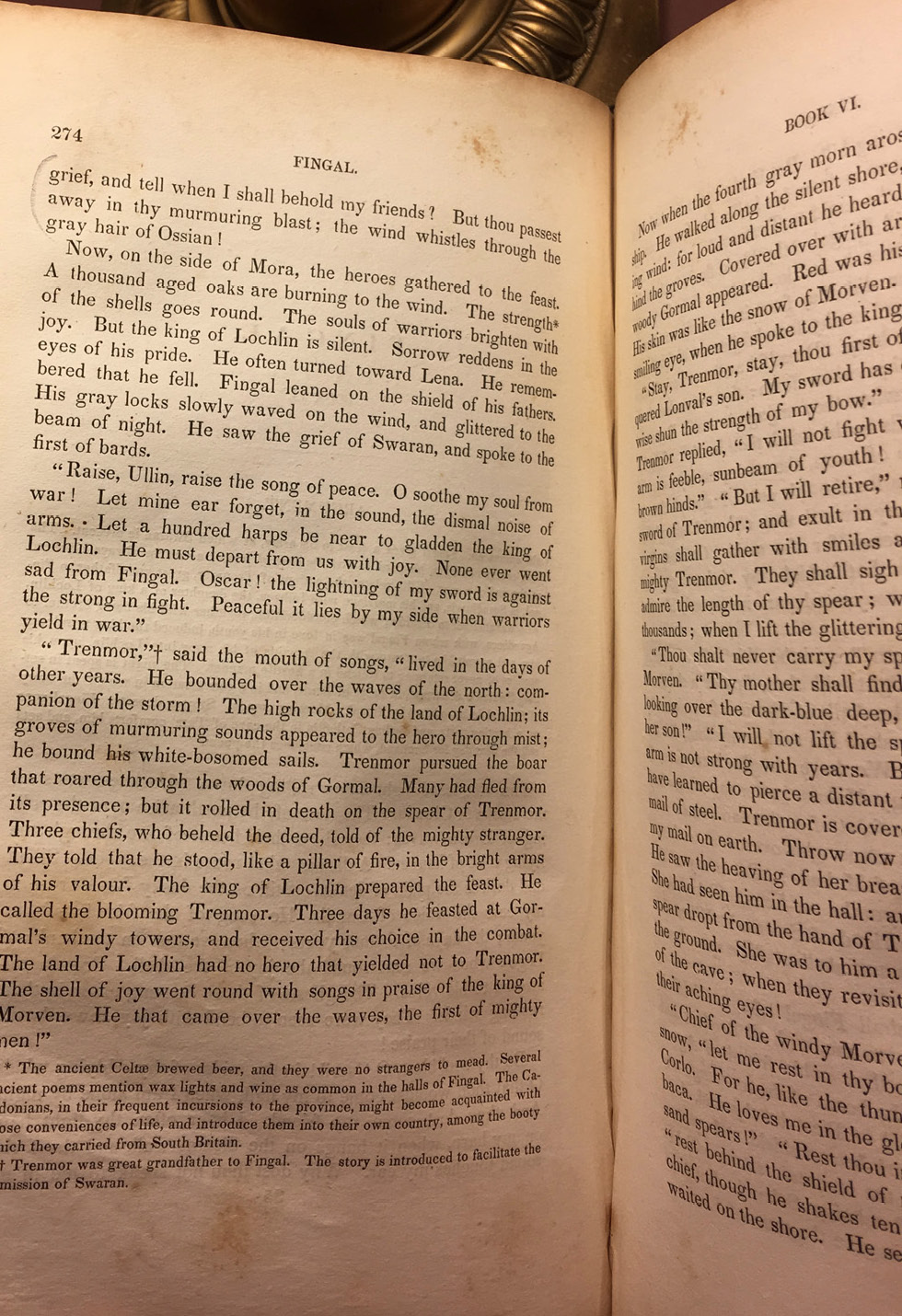

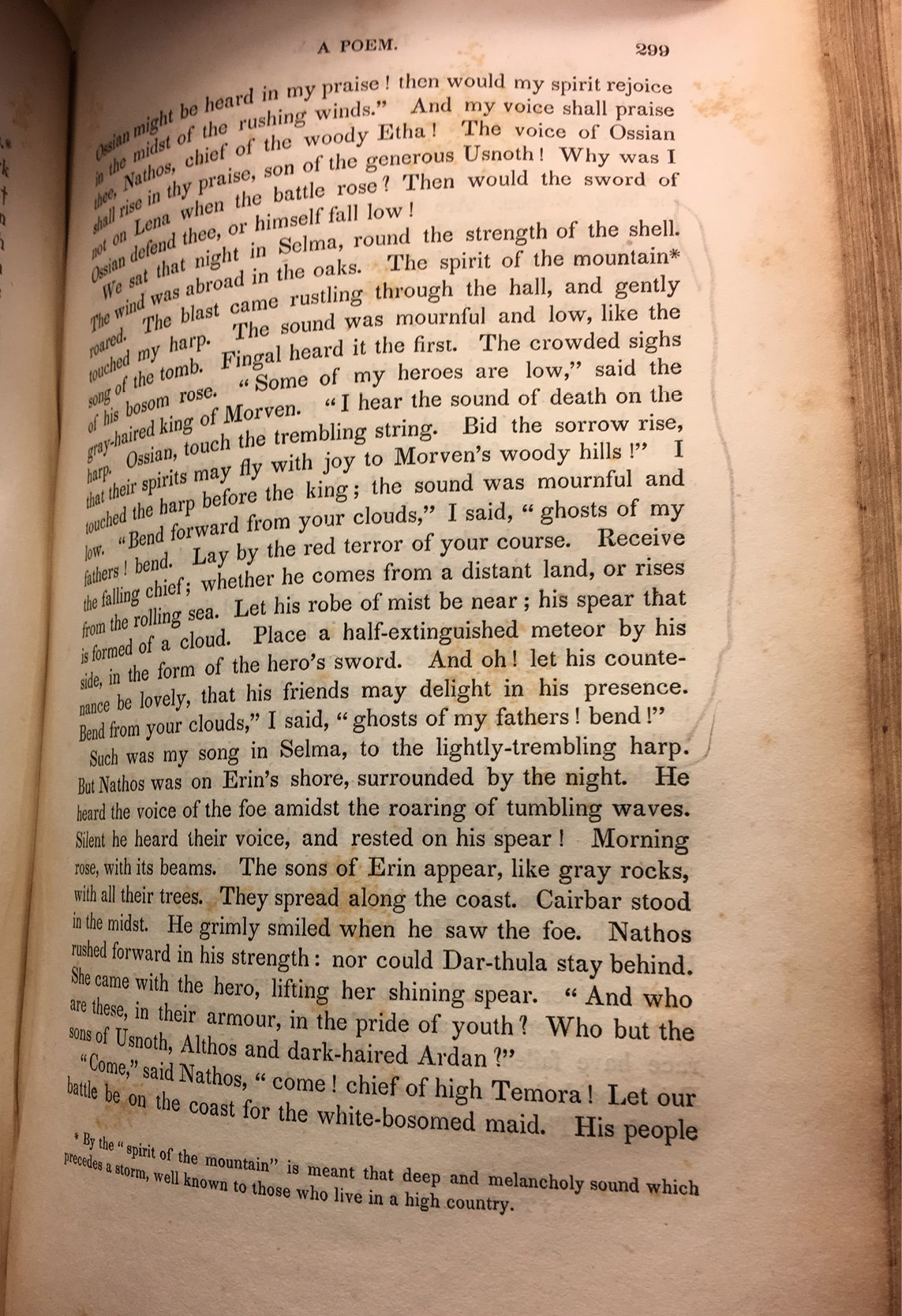

Symptomatic of this blindness and even more problematic for Allen is the sheer absence of lines of verse in the KJB. I repeat: the KJB, like all of its sixteenth-century English predecessors, is a prose translation.54 Moreover, there is no formatting difference between the prose translation of the (Hebrew) Bible’s prose narratives (and other non-poetic materials) and the prose translation of the (Hebrew) Bible’s poetry. They both look very much the same, perhaps with only the smallest bit of extra whitespace in the poetic sections (see esp. Figs. 12, 18–19). This uniformity of appearance effectively levels through much of what distinguishes the underlying poetry of the Hebrew Bible from the prose, and as a consequence disposes readers to read the whole of the Bible uniformly, without a strong awareness of the variety of literary forms and genres in the Bible.55

Fig. 18: Isa 7:19–9:1 from the Harper Illuminated Bible. In the original Hebrew, Isaiah 7–8 is prose and Isaiah 9 is poetry, but all is prose in the KJB and the page layout is the same.

Fig. 19: Isa 9:1–10:11 from the Harper Illuminated Bible. In the original Hebrew, Isaiah 7–8 is prose and Isaiah 9 is poetry, but all is prose in the KJB and the page layout is the same.

Though Allen is correct about the importance of the verse line to the prosodies of both biblical Hebrew verse and Whitman, it is not readily apparent what Whitman could have discerned about line structure from a prose translation lacking any formal marking of verse. This is a problem deserving of critical attention. On the strength of scholarly knowledge of the day and more crucially on Whitman’s own comments, such as in “The Bible as Poetry” and also earlier in his notebooks (for discussion, see Chapter One), one may posit on Whitman’s part a general awareness that the Bible contained poetry, or verse proper. But as to any more specific knowledge regarding the nature of Hebrew verse structure, that is a much more complicated and different proposition entirely, especially if we presume, as Allen does, the mediating force of the KJB. As D. Norton stresses, “It must be painfully apparent to anyone who has tried to read the poetic parts of the KJB using parallelism as a guide to the true form [i.e., line structure] that it is often no help.”56 Perhaps not surprisingly, then, Allen chooses not to use the KJB for his illustrations but instead quotes biblical passages from R. G. Moulton’s “arrangement of biblical poetry in his Modern Reader’s Bible” (see Figs. 21–22), which Allen says “in the main” has as its “basis” the “Lowth system.”57 That is, unlike in the KJB, verse in Moulton’s edition is frequently lineated, following the example of the 1885 Revised Version (see Fig. 23).58 The first of the “many evidences” of Whitman’s indebtedness to the model of the “rhythmic pattern of the English Bible”59 is the equivalence of line units, which Allen summarizes at the end of “Biblical Analogies” in this way:

The first rhythmical principle of the Old Testament poetry is parallelism, or a rhythm of thought, in which the line is the unit. The line is also the unit in Whitman’s poetry, one evidence of which is the punctuation, but conclusive evidence is the fact that the verses may be arranged in synonymous, antithetic, synthetic, and climatic “thought-groups”, just as Moulton prints the poetry of the Bible (emphasis added).60

As Moulton prints the poetry of the Bible this seems self-evident. However, the KJB has no such lines of verse, a fact which the use of Moulton’s edition effectively occludes (cf. Fig. 20 and contrast Figs. 21–23). F. Stovall raises the possibility of Whitman having access to verse translations of biblical poetry, such as those (of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs) by George R. Noyes.61 Though possible—certainly such verse translations in English were available, most stimulated by Lowth’s originary efforts in his Isaiah: A New Translation62—Stovall cannot tie Whitman to any of them. The line forms Whitman prefers are mostly enacted on a (much) larger scale (see below), and Whitman’s known biblical quotations and phrasal borrowings invariably come from the KJB (see Chapter Two). Thus it is not clear that this equivalence of which Allen speaks—the line as the chief rhythmical unit—has quite the force that he imagines, at least not on his representation via Moulton’s translation, as that is a formatting style that becomes most widely accessible only late in Whitman’s life (in the form of the RV).63

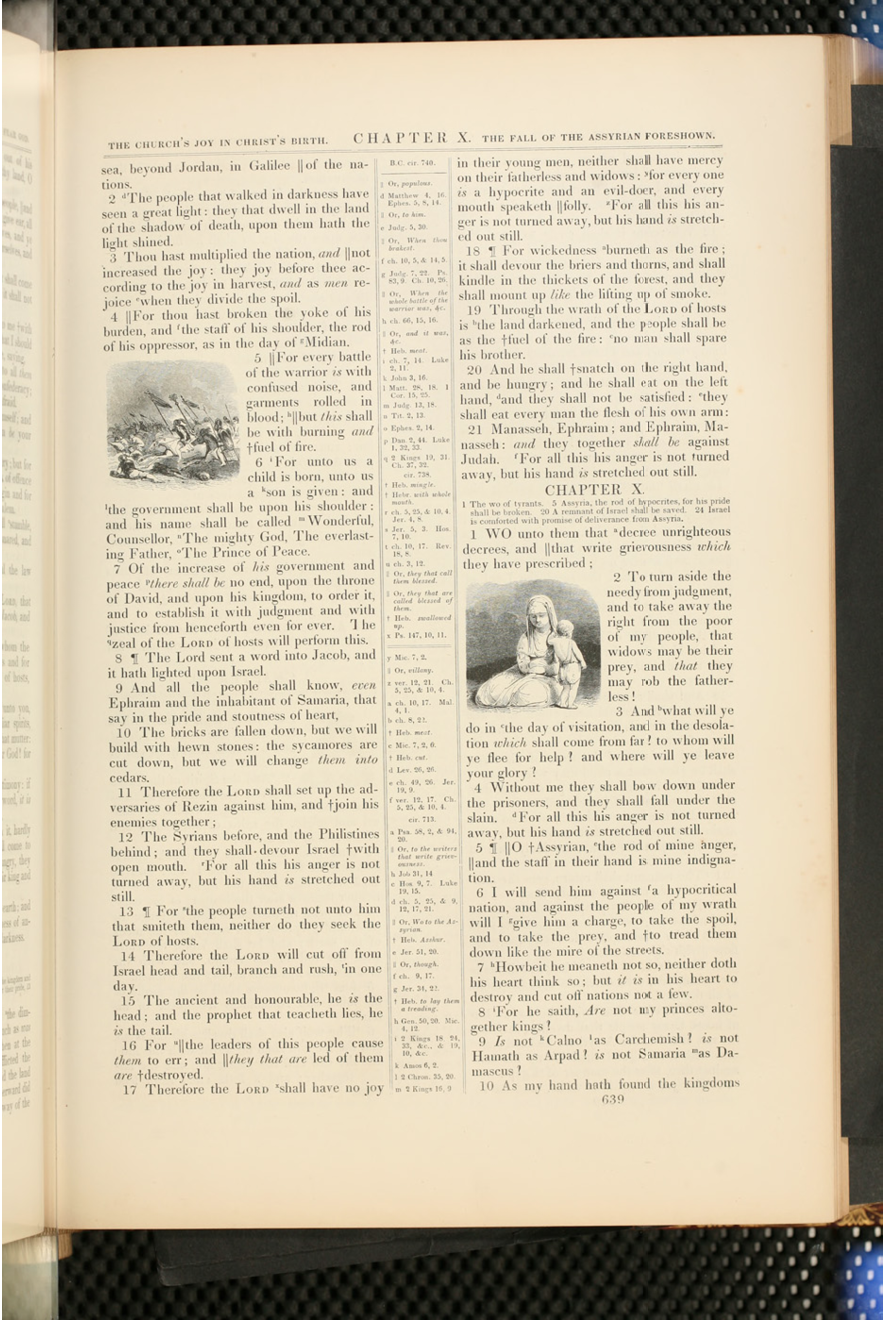

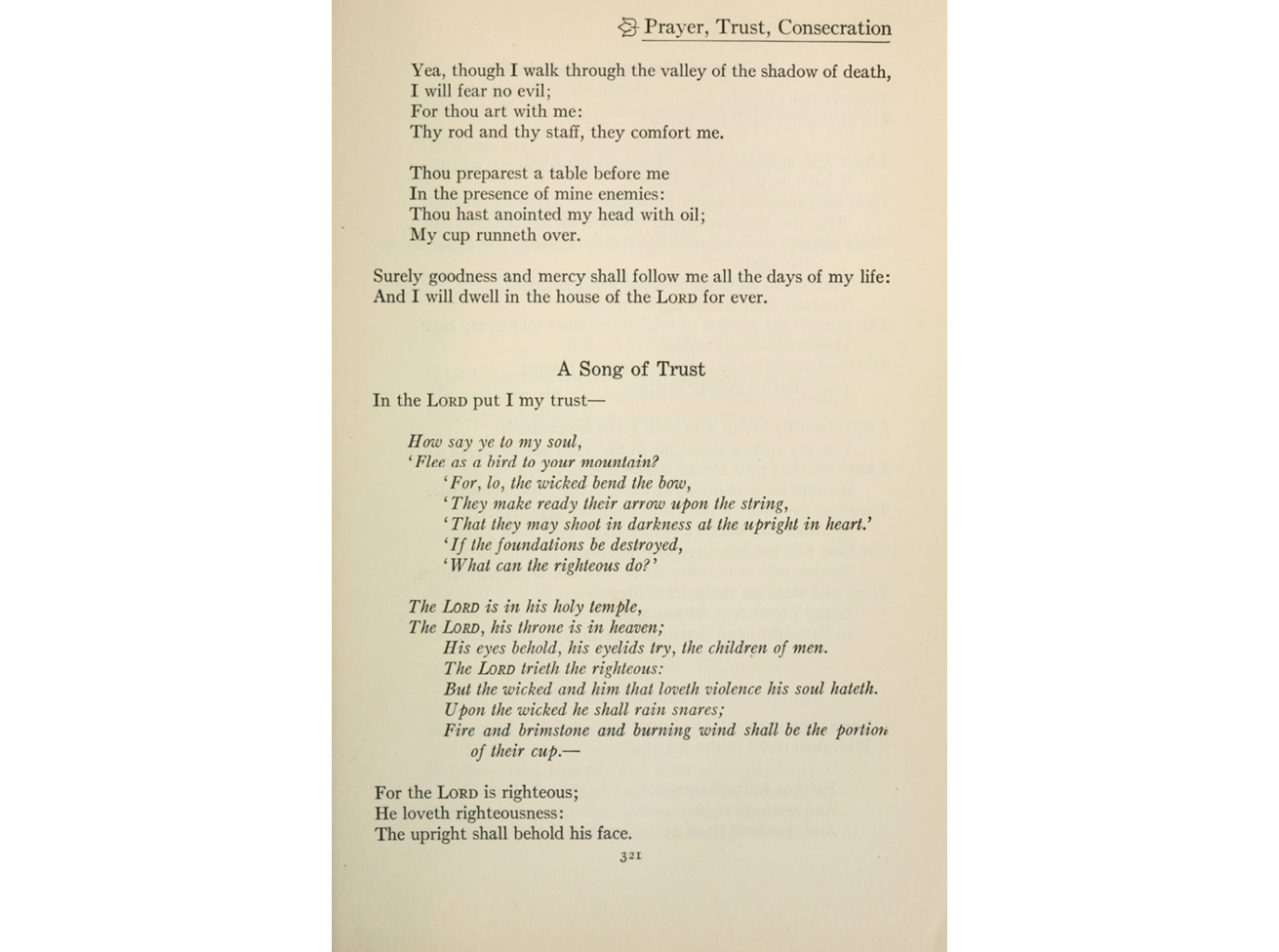

Fig. 20: Ps 23:1–24:23 from the Harper Illuminated Bible. Prose translation of the KJB, with no special formatting for the poetry of this psalm.

Fig. 21: Psalm 23 from R. G. Moulton, Modern Reader’s Bible (New York: Mavmillan, 1922), II, 320. Public domain. Formatted as verse following the lead of the 1885 Revised Version of the Bible.

Fig. 22: Psalm 23 (cont.) from Moulton, Modern Reader’s Bible, II, 321.

Fig. 23: Psalm 23 in the Revised Version (The Holy Bible [Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1885]). Public domain. First major English translation to lineate the poetry of Psalms, Proverbs, and Job as verse.

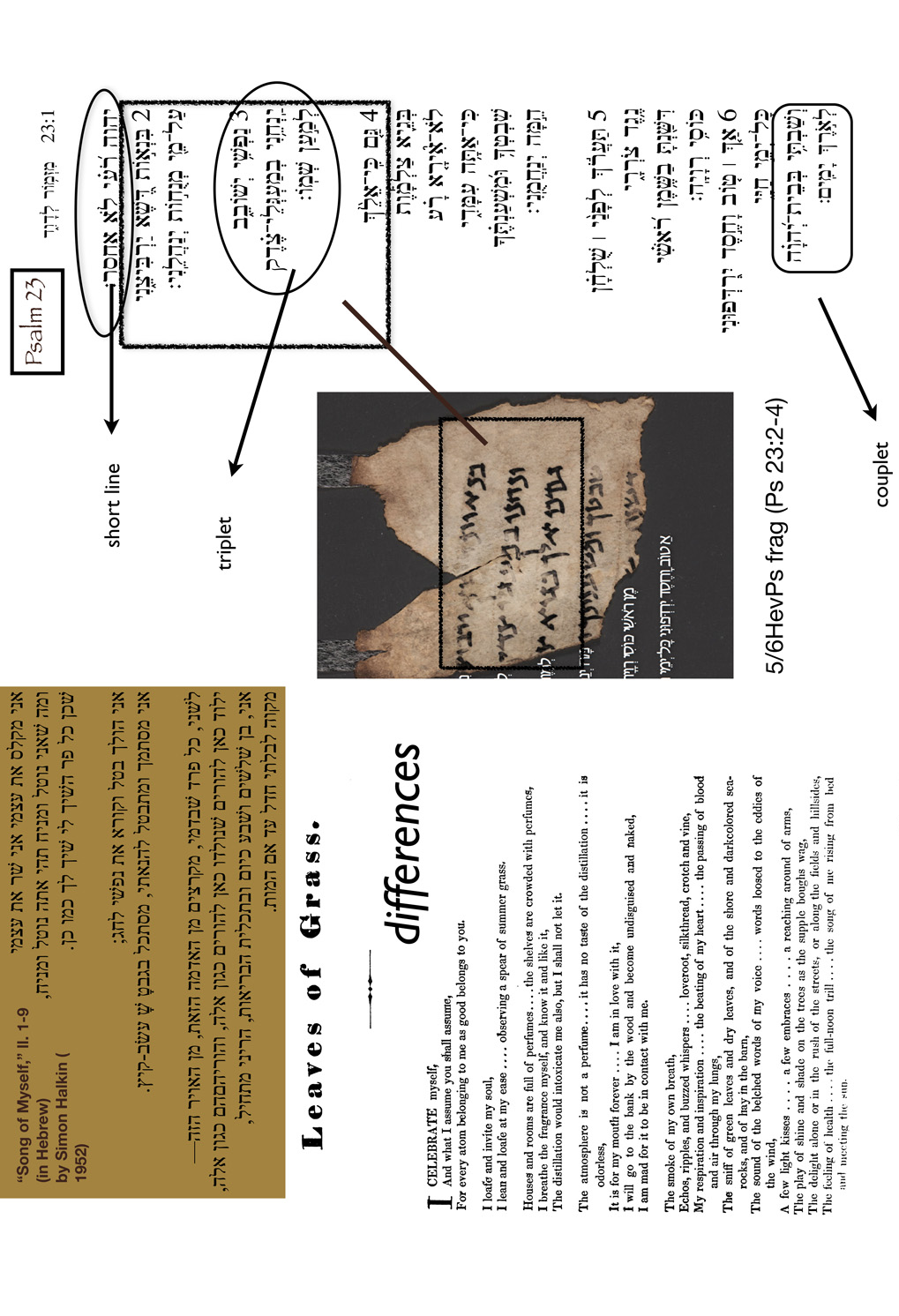

Moreover, in giving visibility to the line structure of the underlying Hebrew original through Moulton’s translation what becomes strikingly apparent—and what would be obvious to any Hebraist—is just how unalike the two line units are. The biblical Hebrew verse line is consistently concise, while Whitman’s line is famously long (and variable); and the biblical verse tradition is dominantly distichic, featuring couplets (and, less commonly, triplets), while Whitman’s verse is prominently stichic. When he does group lines together, their patterns of grouping are quite dissimilar from those in the biblical Hebrew poetic corpus. These are visually apparent even on the most cursory of comparisons (see Fig. 24). Of the two, Allen senses the mismatch in the latter. In his treatment of parallelism in Whitman, he dutifully surveys parallelism involving couplets, triplets, and even quatrains, chiefly because of their prominence in the Bible. But as Allen recognizes, “the number of couplets in Leaves of Grass is not great;”64 that “parallelism in the Bible does not ordinarily extend beyond the quatrain;”65 and perhaps most astutely, that “the couplet, triplet, and quatrain are found more often in the Bible than in Leaves of Grass.”66 I sense in Allen’s minimization of this difference—“the number of consecutive parallel verses is not particularly important”67—an attempt to stave off potentially troublesome worries for his thesis: for example, if Whitman was so impressed by the Bible’s use of parallelism, why is not his own practice of line grouping more reflective of that of the Bible? Of course, it may be that Whitman was simply enamored of the parallelism itself and not the patterns of grouping. But Allen’s own logic of exemplifying and commenting on Whitman’s use of parallelistic couplets and the like suggests that Allen thinks otherwise,68 that he intuitively feels the logic of the worry, though he mostly sweeps it deftly aside.

Fig. 24: A comparison of the differences between Whitman’s typical poetic line and the biblical Hebrew poetic line. Image of p. 13 from the 1855 Leaves, public domain. Image of a 5/6HevPs fragment, showing parts of Ps 23:2–4 (Wikimedia Commons). Unpointed Hebrew translation of “Song of Myself” (lines 1–9), after Simon Halkin.

More surprising is the complete silence as to the difference in line length, which is only too apparent, at least if we are to think of the Hebrew original (usually two to four words) or Moulton’s translation of that original (normally no more than eight or nine words). If the Bible is Whitman’s chief inspiration, wouldn’t there be more lines akin to the length of the typical biblical verse line? This is a potentially more damning worry precisely because Whitman’s own lines (especially early on) are often so strikingly long with absolutely no parallels in biblical Hebrew verse. Neither worry holds substance, however. Whitman had no access to the Hebrew originals. And he probably did not have ready or ongoing access (if any access at all) to an English verse translation of the likes of Moulton’s, which arranges the poetry of the Bible in lines of translated verse, grouped as couplets, triplets and the like according to Lowth’s practice. That is, there is no reason to suspect that Whitman had much (if any) first-hand knowledge of either the nature of line grouping in biblical Hebrew poetry or the typical lengths of these lines (when translated into English). These are features of the biblical verse tradition that are elided in a prose translation like the KJB. It surely is not accidental that it is “chiefly the synonymous variety” of parallelism that Whitman picks up on and uses so pervasively throughout Leaves of Grass.69 Of all linguistic elements, semantics—meaning—is the one most readily translatable. The early translators’ (beginning with Tyndale) sense of a peculiar affinity between Hebrew and English idioms is spurred in part by semantics.70 By contrast, the “core” of parallelism in the poetry of the Hebrew Bible is “syntactic,” viz. the “repetition of identical or similar syntactic patterns” or frames, which when “set into equivalence” bring whatever is “filling those frames” (e.g., lexical items) “into alignment as well.”71

The Verse Divisions of the KJB and Whitman’s Line

More positively, by refocusing on the textual source that prompted Allen’s interest in the first place, the KJB, and the fact that this is a specifically prose translation in distinct formats and page layouts, potential points of similarity between this Bible and Whitman’s line more readily resolve themselves. Besides the parallelistic play of meaning (and syntax) and the rhythm effected in part through this play, both characteristics of the biblical Hebrew verse tradition that were accessible to Whitman through translation, Whitman would have literally seen the verse divisions of the KJB itself. This is a point made early, though little noticed, by G. Saintsbury in his review of the 1871(–72) edition of Leaves of Grass: “Perhaps the likeness which is presented to the mind most strongly is that which exists between our author and the verse divisions of the English Bible, especially in the poetical books, and it is not unlikely that the latter did actually exercise some influence in molding the poet’s work.”72 The “verse divisions of the English Bible” in the Old Testament correspond almost without fail to the full stop (sôp pāsûq) used by the Masoretes to mark the end of a biblical verse. In the narrative sections of the Hebrew Bible, the sôp pāsûq tends to demarcate a complete sentence, though the sentences may vary considerably in length and complexity. In “the poetical books,” the sôp pāsûq does not demarcate the end of a single line of verse in Hebrew, but two, three, four, and sometimes even more such lines. So as in the prose sections there is variability here, too; however, it is far more constrained and regular, given the simpler clause structures and uniformly concise verse lines (see Figs. 12, 19, 20). The formatting in the KJB is the same, whether for prose or poetry, though because of the latter there is subtly more whitespace on the page in the poetic books (see Figs. 12, 18–19). Numerous aspects of Whitman’s mature and signature line—viz. its variability, range of lengths, typical shapes and character, and content—become more clearly comparable to the Bible when thought through in light of Saintsbury’s appreciation of the significance of the actual “verse divisions of the English Bible.”

The Lengths of Lines

Most obvious, perhaps, is that the range of line-lengths in the 1855 Leaves is roughly equivalent to that of the verse divisions of the KJB, especially, as Saintsbury perceives, in the poetic books (e.g., Psalms, Proverbs, Job), and as significant the mix of line-lengths and the mise-en-page that this mix effects is strikingly similar in both as well. Consider the familiar Psalm 23 (which Whitman read) lineated according to the verse divisions in the KJB (see Fig. 20):

1The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

2He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

3He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

4Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

5Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

6Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the LORD for ever.

Note the overall length of the individual verse divisions and their variety. Compare this profile, first, with Moulton’s version of the same psalm, which aims to follow the contours of the original Hebrew line structure,73 resulting in much shorter lines, grouped as couplets74—the indentation and spacing are Moulton’s invention (see Figs. 21–22):

The LORD is my shepherd;

I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures:

He leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul:

He guideth me in the paths of righteousness for his name sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil;

For thou art with me:

Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me

In the presence of mine enemies:

Thou hast anointed my head with oil;

My cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life:

And I will dwell in the house of the LORD for ever.75

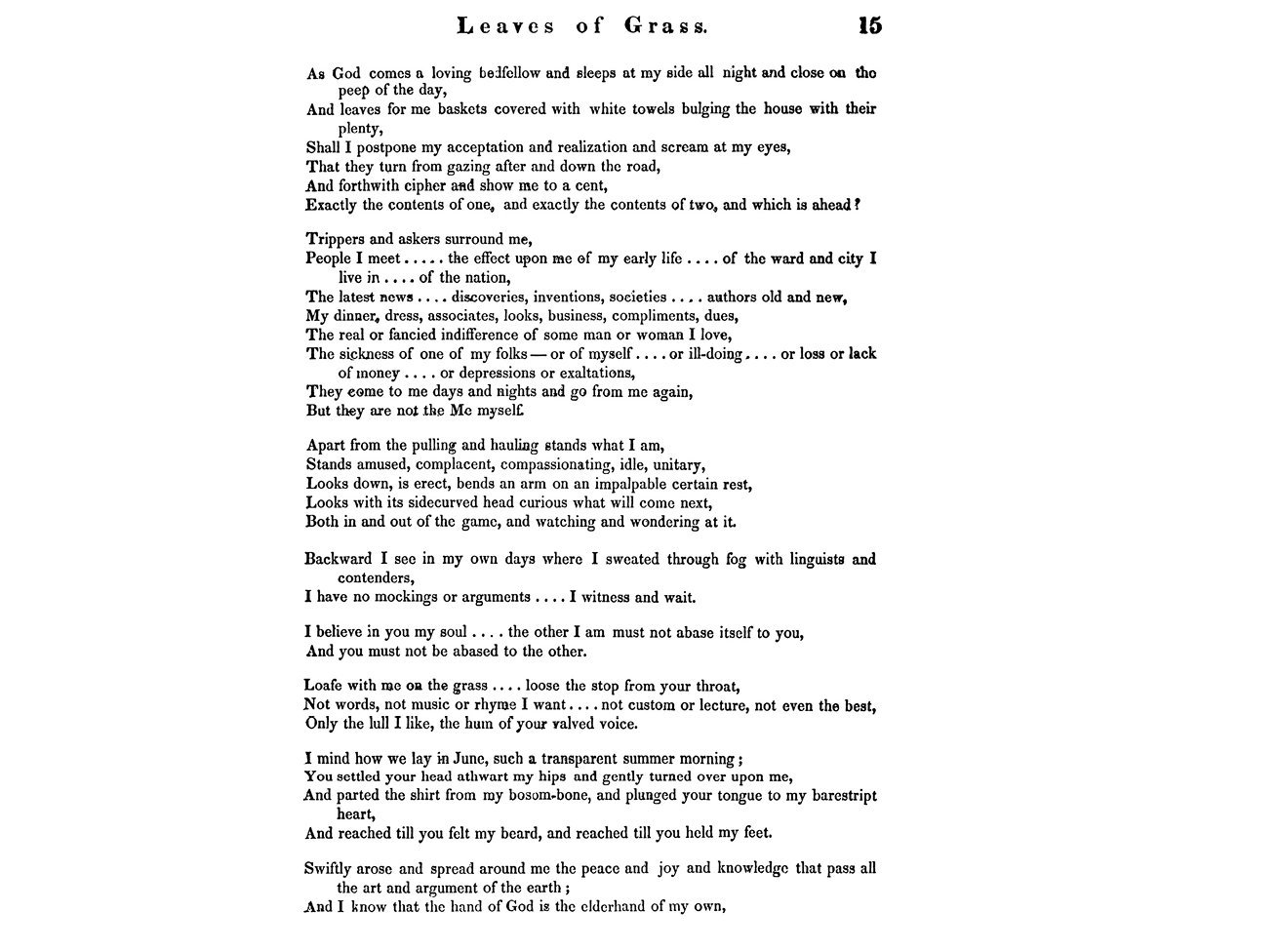

Now consider a few brief selections from the 1855 Leaves (see Figs. 25–26):

Trippers and askers surround me,

People I meet….. the effect upon me of my early life…. of the ward and city I live in…. of the nation,

The latest news…. discoveries, inventions, societies…. authors old and new,

My dinner, dress, associates, looks, business, compliments, dues,

The real or fancied indifference of some man or woman I love,

The sickness of one of my folks—or of myself…. or ill-doing…. or loss or lack of money…. or depressions or exaltations,

They come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself. (LG, 15)

And:

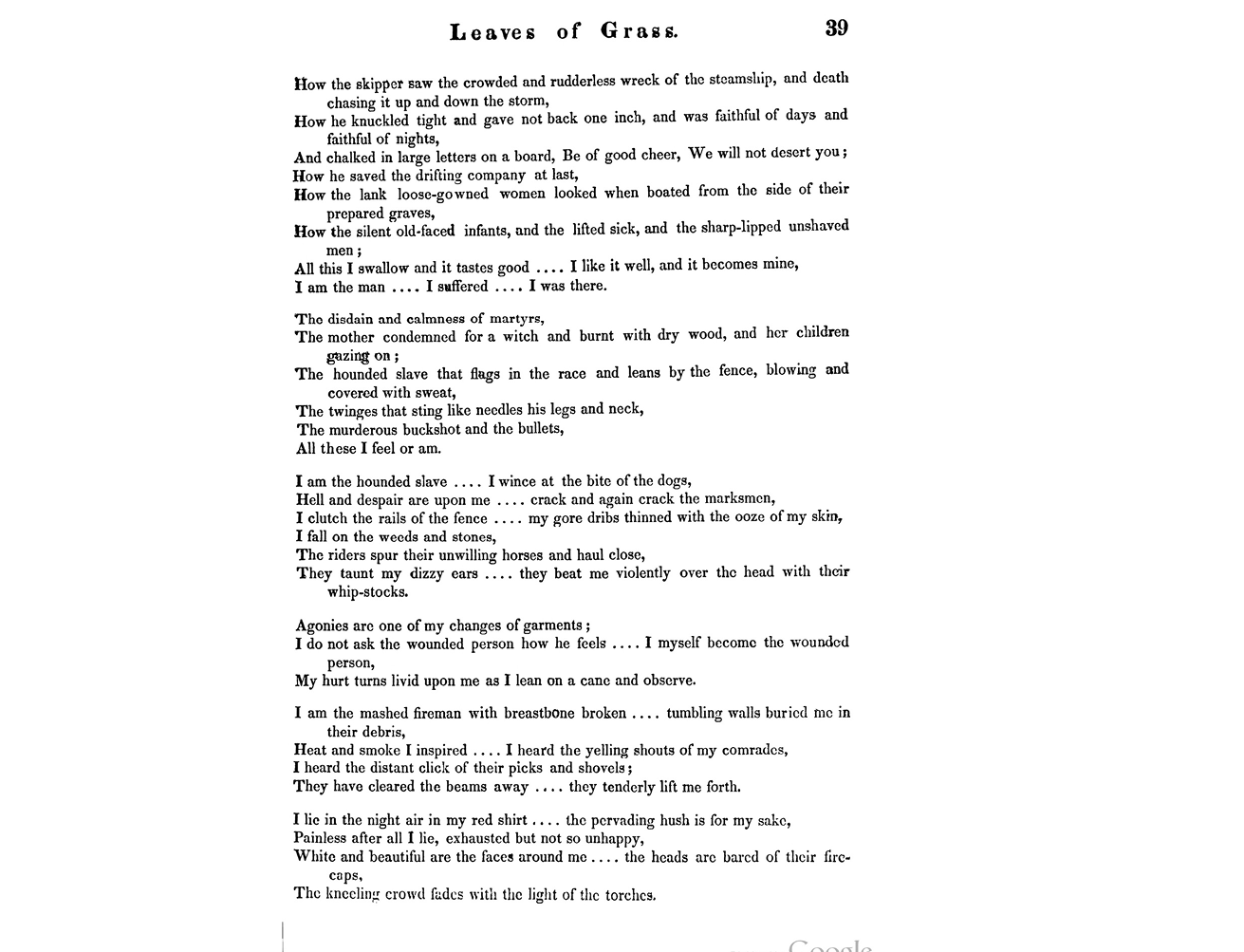

I am the hounded slave…. I wince at the bite of the dogs,

Hell and despair are upon me…. crack and again crack the marksmen,

I clutch the rails of the fence…. my gore dribs thinned with the ooze of my skin,

I fall on the weeds and stones,

The riders spur their unwilling horses and haul close,

They taunt my dizzy ears…. they beat me violently over the head with their whip-stocks. (LG, 39)

Initially, note the typical lengths of Whitman’s lines, which, with but a few exceptions (e.g., “But they are not the Me myself”; “I fall on the weeds and stones”), are much too long for a translated line of actual biblical verse but compare favorably with the verse divisions of the KJB. So:

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. (Ps 23:2, KJB) [sixteen words]

I clutch the rails of the fence…. my gore dribs thinned with the ooze of my skin, (LG, 39) [seventeen words]

Vs:

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: [nine words; Hebrew: three words]

He leadeth me beside the still waters. (Moulton) [seven words; Hebrew: four words]

Or:

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over. (Ps 23:5, KJB) [twenty-two words]

People I meet….. the effect upon me of my early life…. of the ward and city I live in…. of the nation, (LG, 15) [twenty-two words]

Vs:

Thou preparest a table before me [six words; Hebrew: three words]

In the presence of mine enemies: [six words; Heb.: two words]

Thou hast anointed my head with oil; [seven words; Hebrew: three words]

My cup runneth over. (Moulton) [four words; Heb.: two words]

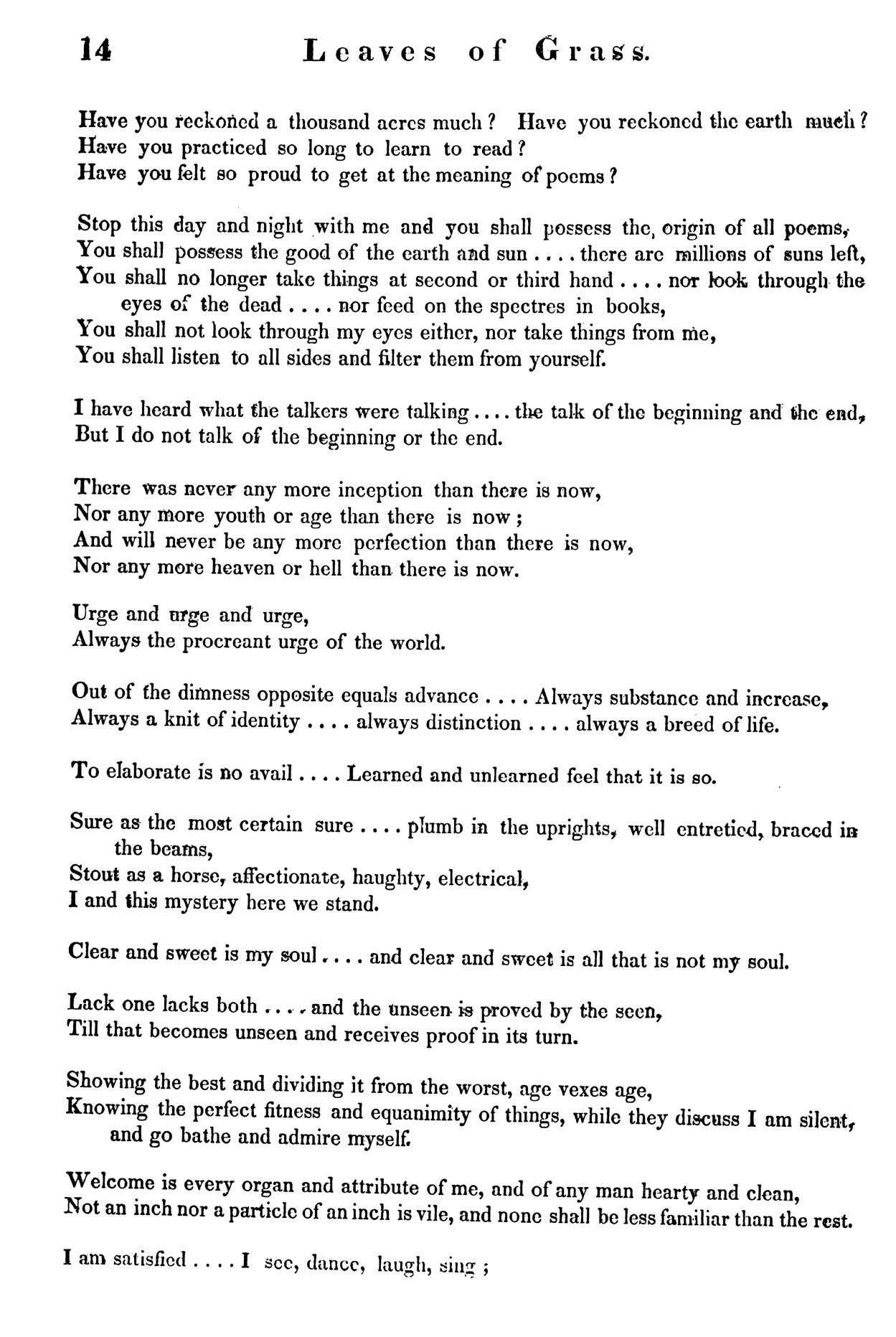

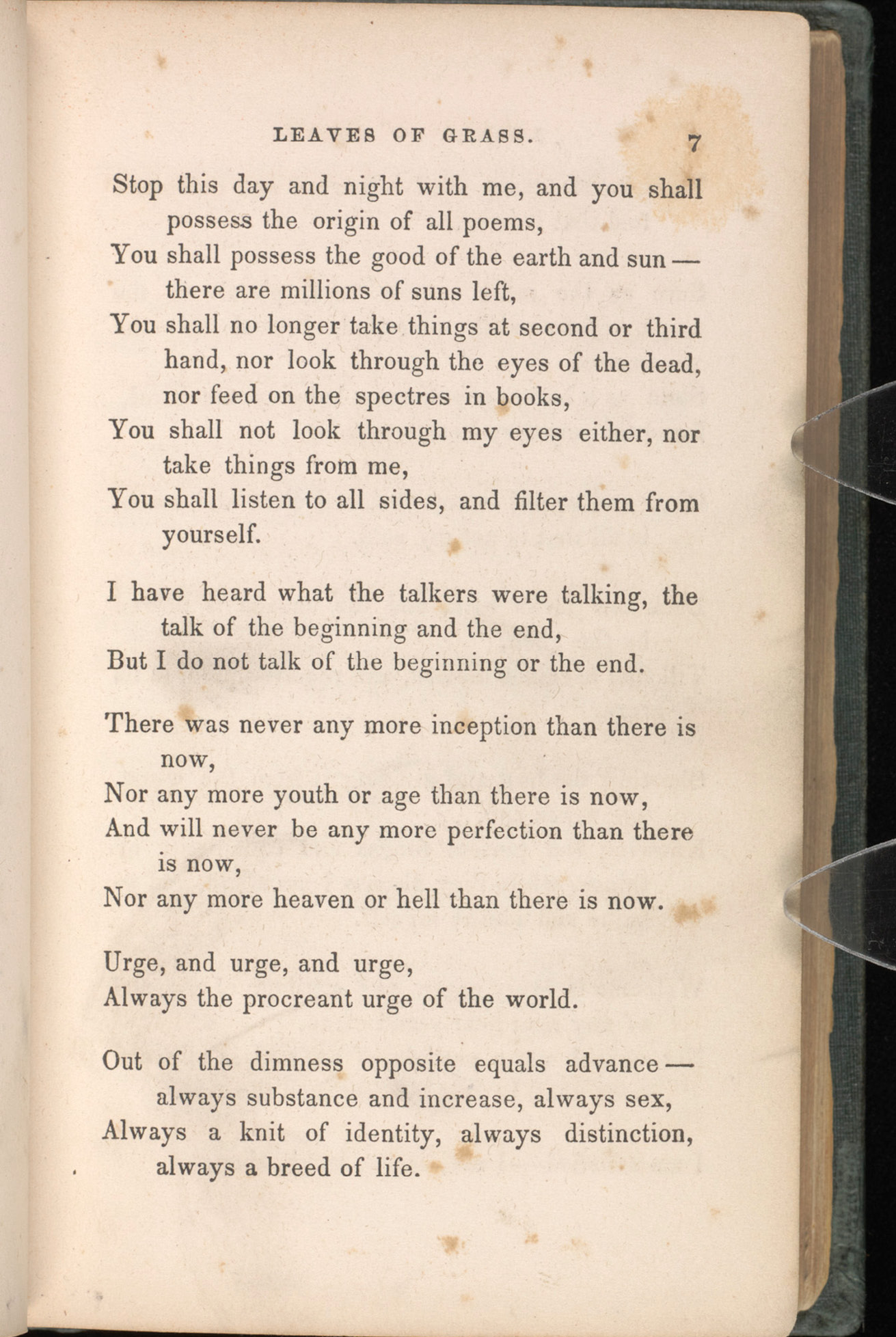

Fig. 25: P. 15 from the 1855 Leaves of Grass (Brooklyn, NY, 1855). Public domain.

Fig. 26: P. 39 from the 1855 Leaves.

The sharp contrast in length is noticeably apparent between the lines in Whitman and in the KJB verse divisions, on the one hand, and in Moulton’s versions, on the other hand. This point may be underscored to good effect by comparing the Hebrew of the latter biblical passage, Ps 23:5, with its characteristic short lines,

תַּעֲרֹ֬ךְ לְפָנַ֨י ׀ שֻׁלְחָ֗ן

נֶ֥גֶד צֹרְרָ֑י

דִּשַּׁ֖נְתָּ בַשֶּׁ֥מֶן רֹ֝אשִׁ֗י

כּוֹסִ֥י רְוָיָֽה׃

with a set of Whitman’s long lines from the beginning of “Song of Myself” in Simon Halkin’s Hebrew translation:76

—לְשֹׁנִי ֥ כָּל פְּרָד שֶׁבְּדָמִי ֥ מְקֹרָצִים מִן הָאֲדָמָה הזֹּאת ֥ מִן הָאַוִּיר הַזֶּה

֥יָלוּד כָּאן לְהוֹרִים שֶׁנּוֹלְדוּ כָּאן לְהוֹרִים כְּגוֹן אֵלֶּה ֥ וְהוֹרֵיהֶם הֵם כְּגוֹן אֵלֶּה

֥ אֲנִי ֥ בֶּן שְׁלֹשִׁים ושֶׁבַע כַּיּוֹם וּבְתַכְלִית הַבְּרִיאוּת ֥ הֲרֵינִי

.מְקַוֶּה לְבִלְתִּי חֲדֹל עַד אִם הָמַּוֶת

(My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death. [LG 1892, 29])

Again, the contrast in line length is stark. Halkin’s rendition of the first two lines of Whitman each contains more words (eleven) than in the four lines of the psalm combined (ten words). And though hardly the kind of empirical sifting that would be required to make a full case, my strong impression is that the general picture registered by these few examples holds across the board. Dip anywhere into Whitman’s 1855 Leaves and the poetic books of the KJB and the same rough equivalences in lengths of lines and verse divisions appear. The same point is made by Robert Alter in a wholly different context but in a way that is nevertheless quite telling for my own thesis. He says of the KJB’s long cherished rendering of Ps 23:4 (“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me”) that it has “the beauty of a proto-Whitmanesque line of poetry rather than of biblical [Hebrew] poetry.”77 Alter here, implicitly, joins the likes of Saintsbury in recognizing the connection between Whitman and the KJB, at least in terms of line length.

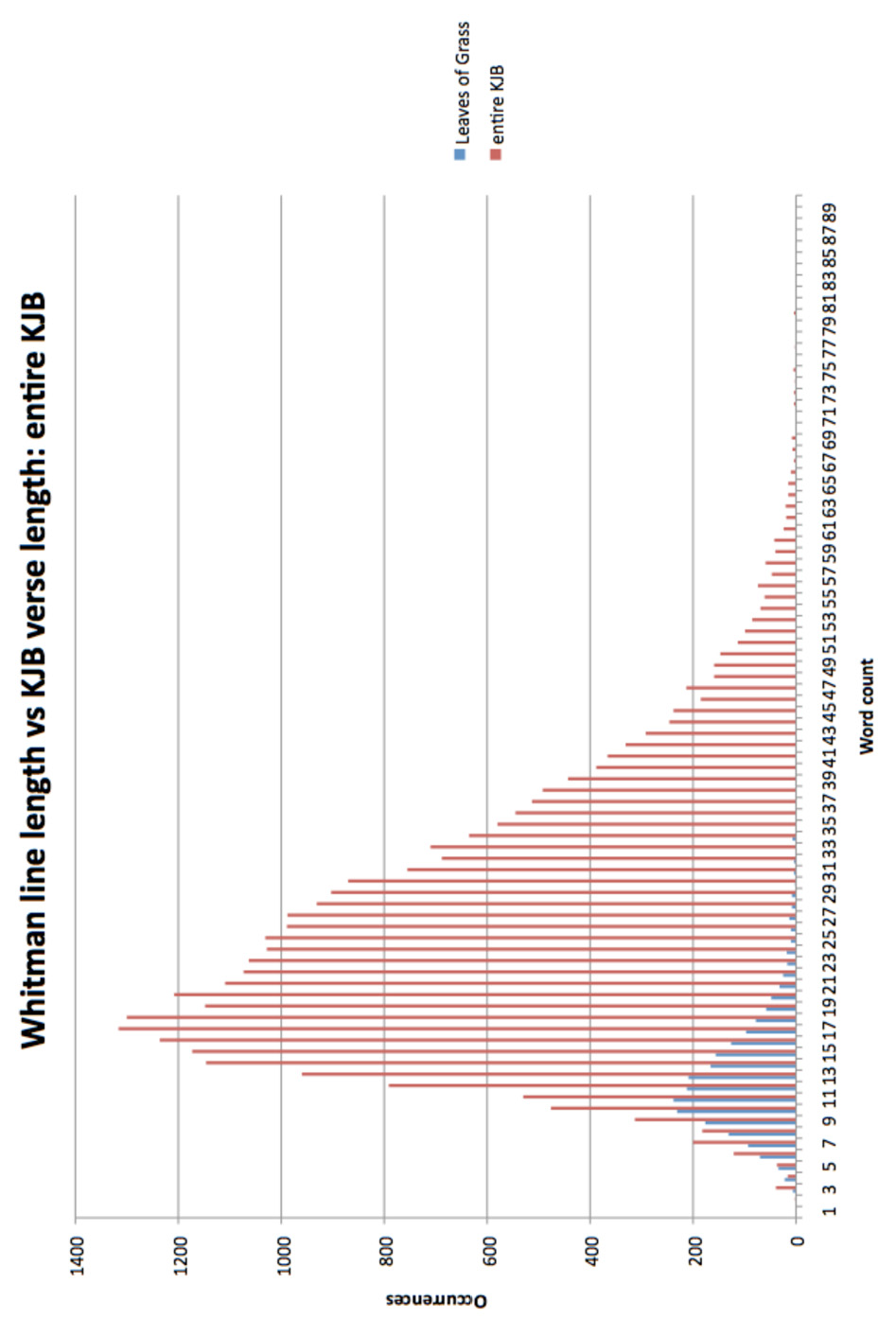

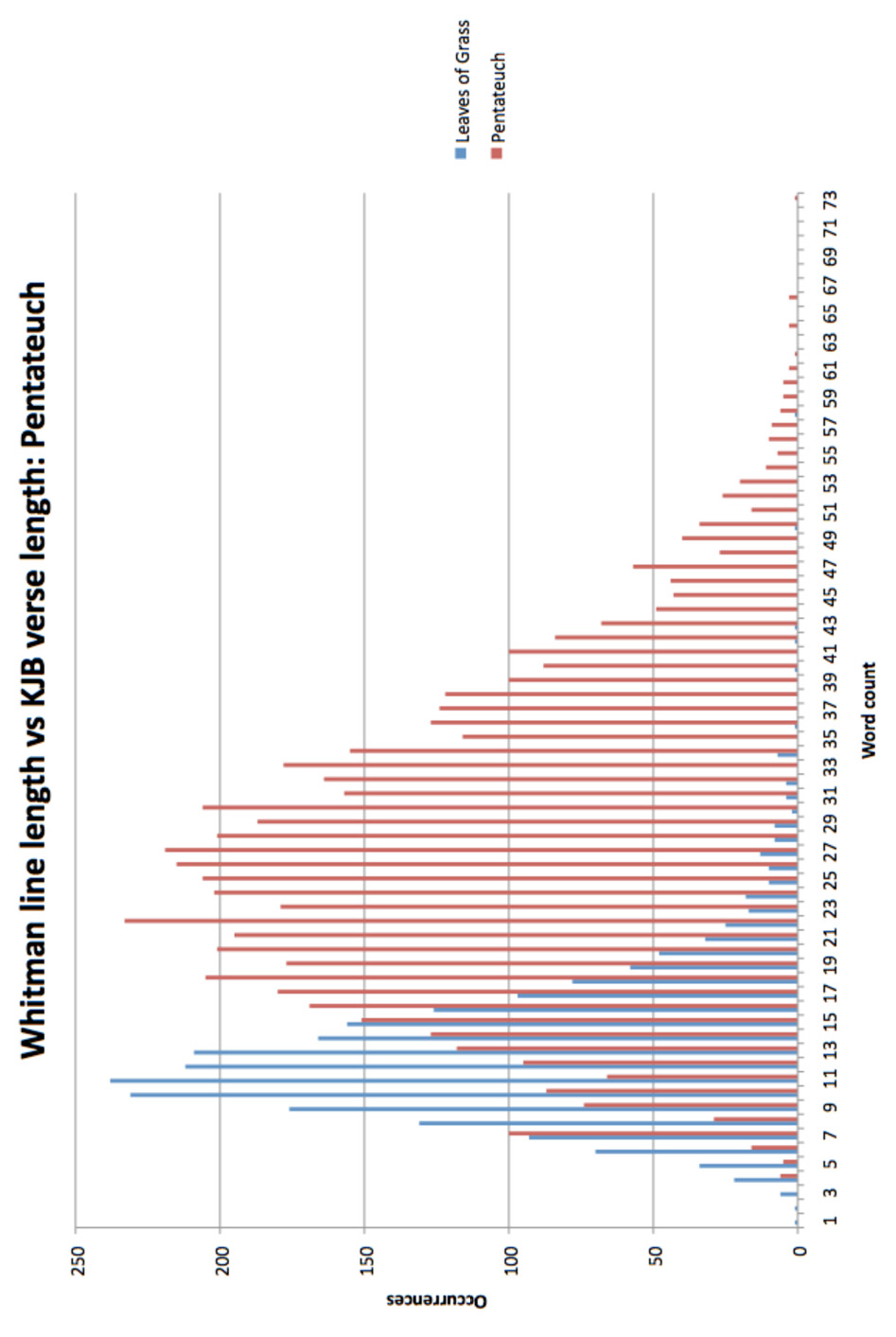

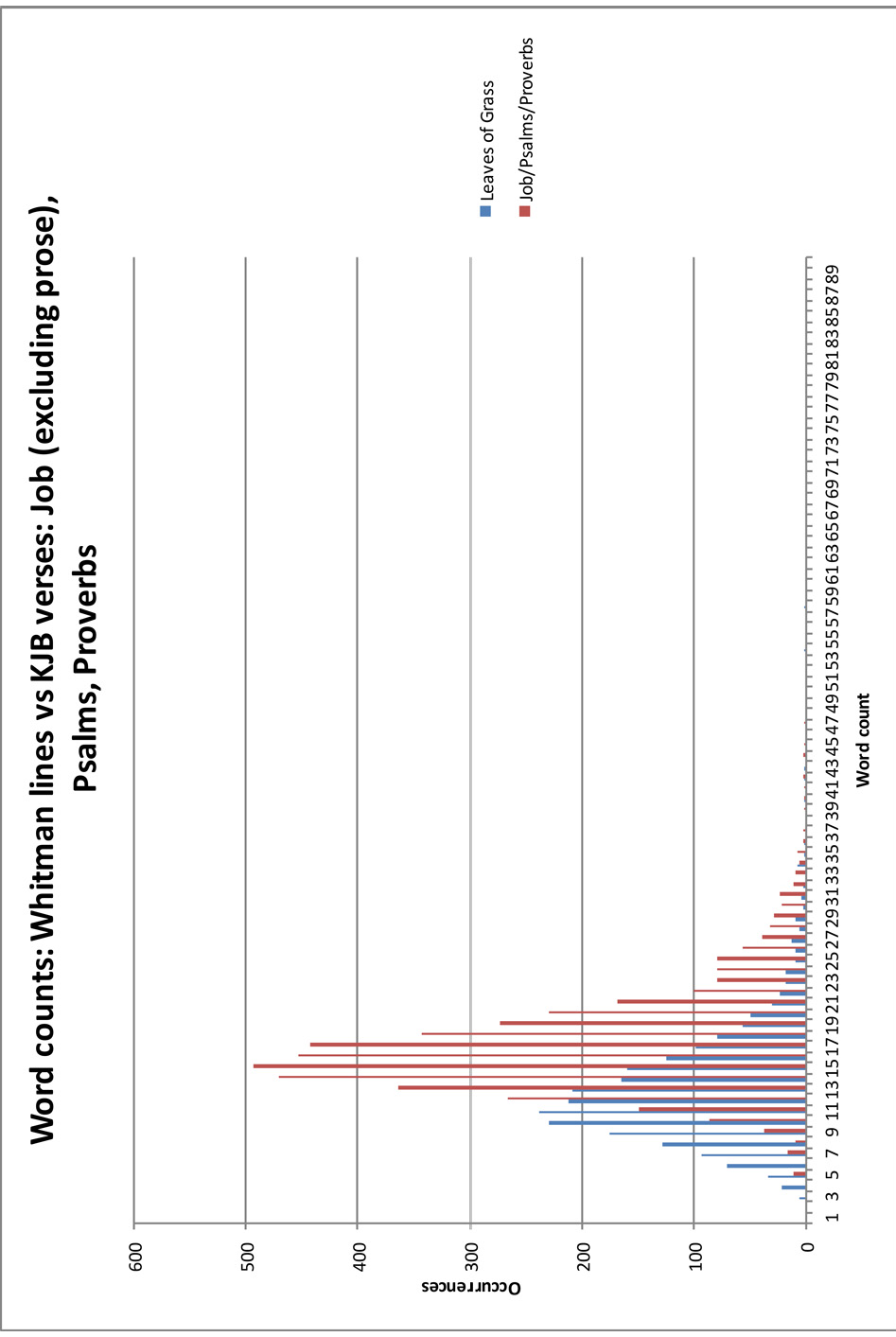

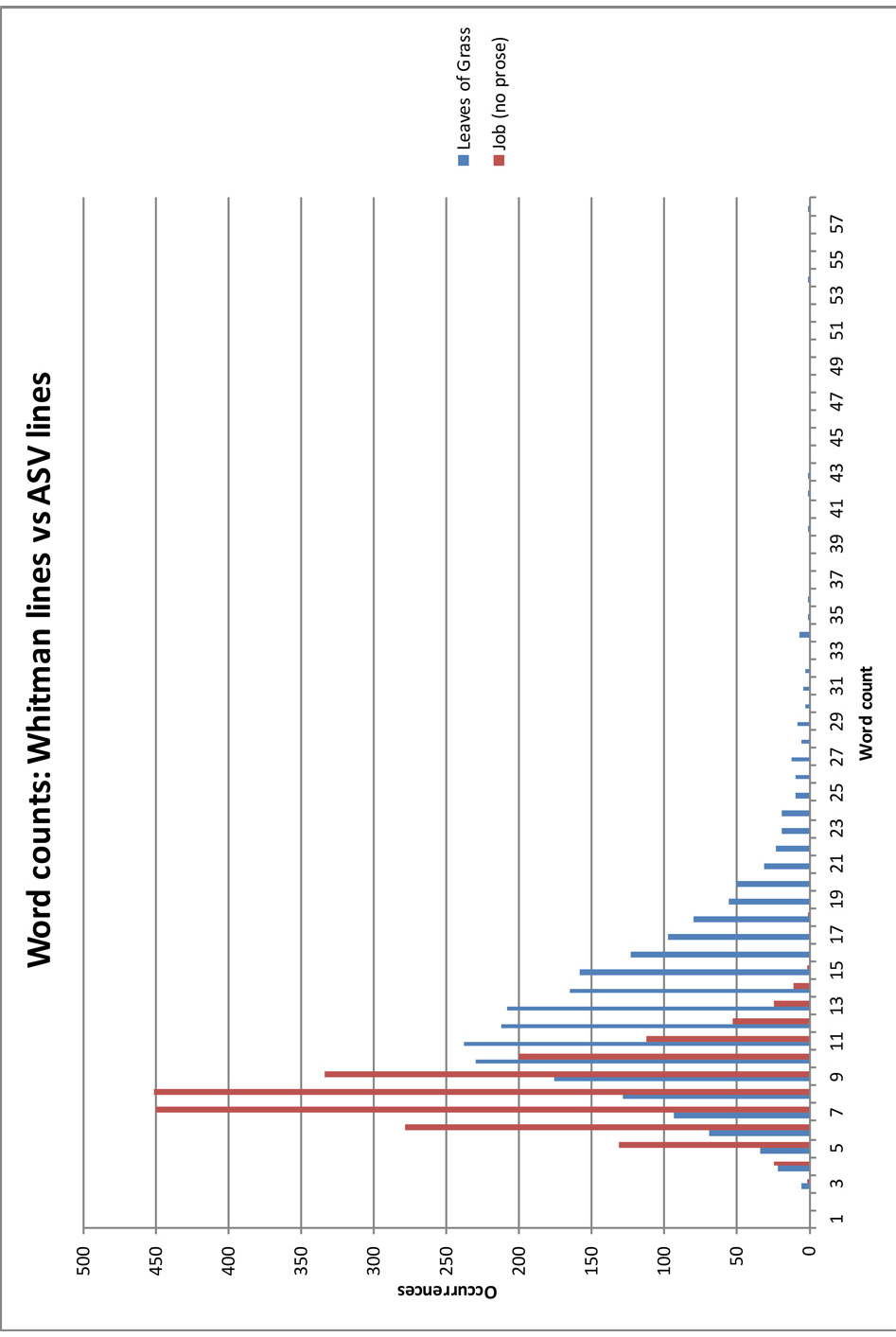

These word counts serve as a crude barometer of dis/similarity. They cannot be pressed too literally. And yet they are also possibly the surest means of measuring and comparing the gross scales of Whitman’s lines (in the 1855 Leaves) and the KJB’s verse divisions. With the aid of computerization such measures can be quantified (to a degree; see charts in Figs. 15, 27–29).78 Fig. 29 is perhaps the most striking, as it shows a considerable degree of overlap between the basic length profiles for Whitman’s verse lines in the 1855 Leaves and the verse divisions of the KJB in the three specially formatted (in the Masoretic tradition) books of biblical poetry: Psalms, Proverbs, and Job.79 The match is not perfect, but it is incredibly close. For example, as noted Whitman’s sweet spot in terms of line-length in the 1855 edition is between eight and sixteen words, accounting for 71% of all lines in the volume. The comparable core of verse divisions in the three poetic books from the KJB contains between twelve and twenty words, accounting for roughly 76% of the verse divisions in this material (Fig. 29). This overlapping correlation in length gives substantial back-up to Saintsbury’s early impressions (“especially in the poetical books”). By contrast, Fig. 30 (comparing the line lengths of Whitman’s 1855 Leaves and the 1901 ASV [Job], which like the RV offers lineated versions of Psalms, Proverbs, and Job) shows the overall dissimilarity between Whitman’s line and the average lengths of translated versions of the constrained biblical Hebrew poetic line.80 Fig. 28, which compares Whitman’s line to KJB-Pentateuch (comprised primarily of biblical prose), not surprisingly shows a good chunk of the KJB’s verse divisions in this material containing more words per verse than does Whitman per line—not surprising because however prosaic Whitman’s verse, it is finally verse and not prose. Importantly, however, Whitman’s longest lines (forty-seven words or more) are comparable only with the verse divisions of biblical prose (see esp. Figs. 27–28)—he was reading the whole Bible.

Fig. 27: Comparison by word count between the lengths of lines in the 1855 Leaves and the verse divisions of the entire KJB. Computation and chart by Greg Murray.

Fig. 28: Comparison by word count between the lengths of lines in the 1855 Leaves and the verse divisions of KJB-Pentateuch. Computation and chart by Greg Murray.

Fig. 29: Comparison by word count between the lengths of lines in the 1855 Leaves and the verse divisions of KJB-Job/Psalms/Proverbs. Computation and chart by Greg Murray.

Fig. 30: Comparison by word count between the lengths of lines in the 1855 Leaves and the lineated translation of ASV-Job. Computation and chart by Greg Murray.

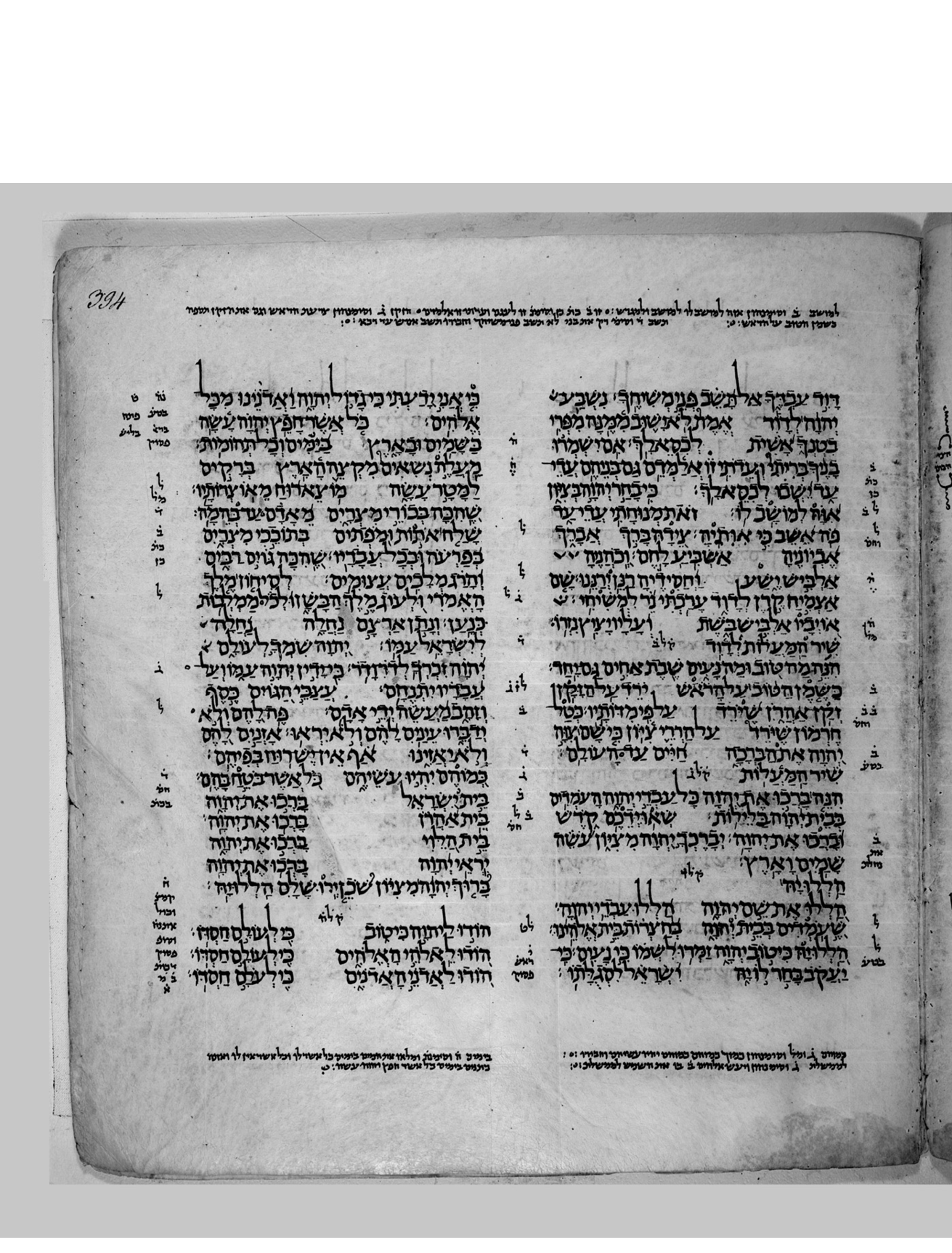

Fig. 31: B19a (Leningrad Codex), folio 423 recto (Ruth 4:13B-Song 2:5A). Freedman et al., The Leningrad Codex. Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research, in collaboration with the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center. Courtesy Russian National Library (Saltykov-Shchedrin).

Fig. 32: B19a, folio 394 recto (Psalm 133). Freedman et al., The Leningrad Codex. Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research, in collaboration with the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center. Courtesy Russian National Library (Saltykov-Shchedrin).

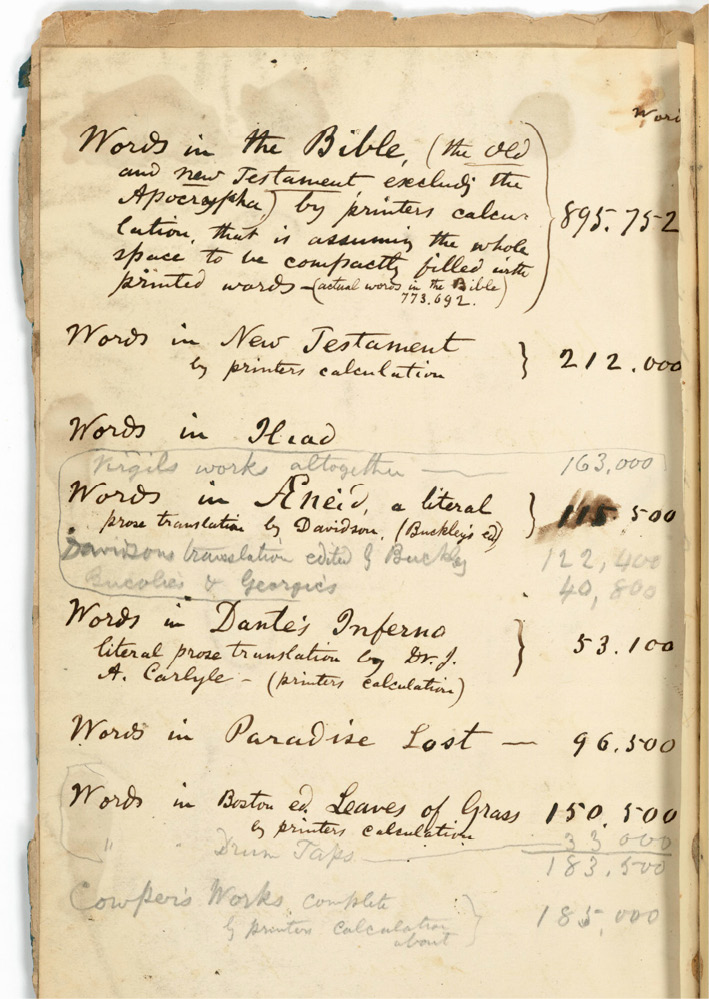

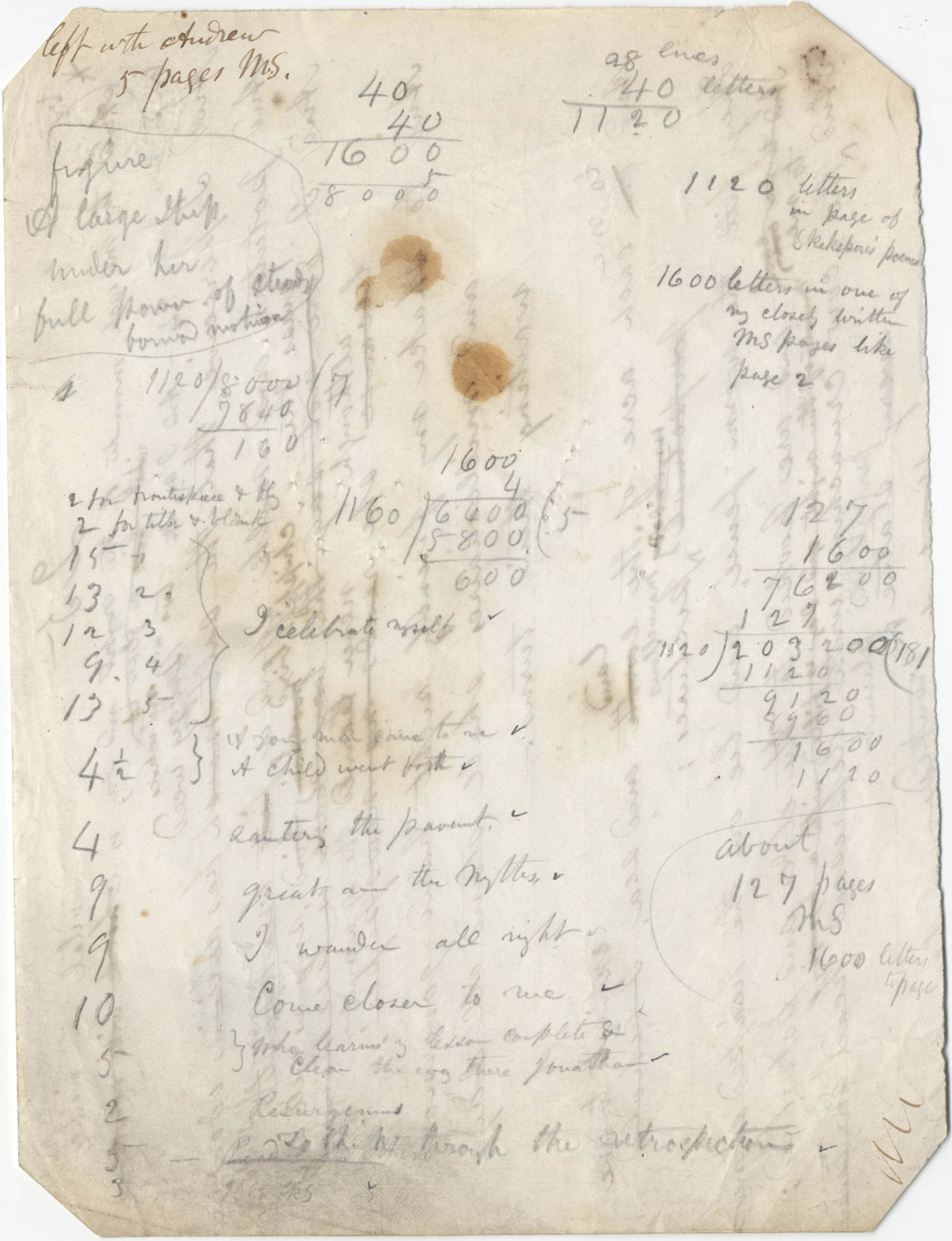

I do not postulate Whitman literally using word counts to generate his poetry or even to mimic (in some hyper-literal way) the variable lengths of the KJB’s verse divisions. As Posey wryly remarks, “I suppose nobody thinks that he sat down with a psalm before him and wrote a poem laboriously fitted to the pattern.”81 Rather, the KJB and its verse divisions furnished Whitman with the model for a long(er) and highly variable line that he then fitted and honed to his own liking, as he can be seen doing in his notebooks and poetry manuscripts. This is precisely the manner of Whitman’s “inspiration” when he bothers to record it, a brief animating (“spinal”) idea that is then worked out over and over (“incessantly”) until it is made to Whitman’s liking.82 Having said that, on at least two occasions Whitman actually counted the number of words and even letters used in (some of) his poems. Most famously, as previously noted, at the beginning of Whitman’s so-called “Blue Book” edition of the 1860 Leaves,83 the poet records (printer calculations of) overall word counts for Leaves (183,500 words, inclusive of Drum-Taps), the Bible, and other classic works (see Fig. 33).84 Here one has the sense that Whitman is using the word counts to measure his poetic accomplishments to date.85 Of equal interest is the verso of a single, 1855 manuscript leaf currently housed in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin (Fig. 34).86 Whitman scribbles notes on this side of the leaf about the size of and a projected arrangement for the 1855 Leaves (though the latter differs markedly from the edition eventually published). In an effort to estimate the number of printed pages needed for the volume, Whitman tallies up the number of letters on average used in what he describes as “one of my closely written MS pages”—he estimates using “1,600” letters. He compares this to the number of “letters in a page of Shakespeare’s poems”—“1,120” is recorded. From this he calculates that the printed Leaves will run to “about 127 pages”—this turns out to be a little off (the 1855 Leaves is 95 pages long), perhaps because of the unusually large page size (“about the size and shape of a block of typewriting paper”)87 used in the 1855 edition. Both items plainly show that literal counts of words and letters factored in Whitman’s thinking about his poetry on occasion.

Fig. 33: Whitman’s comparative word counts on the second leaf of the so-called “Blue Book” edition of the 1860 Leaves. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Fig. 34: Verso of “And to me every minute,” https://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/figures/tex.00057.002.jpg. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Estimated average number of letters in what Whitman considers “one of my closely written MS pages,” comparing to the number of “letters in page of Shakespeare’s poems.”

In fact, however, word (and letter) counts alone do not adequately register the expanded spatial scale of Whitman’s typically long lines in the 1855 Leaves, especially for comparative purposes. The language material that makes up Whitman’s lines and the KJB’s verse divisions are dissimilar in a number of important ways. First, the KJB inherited Willian Tyndale’s preference for Anglo-Saxon monosyllables, which contrasts strikingly with the many polysyllabic and compounded, often Latinate words—not to mention Whitman’s fondness for foreign-derived words of all kinds—that populate Whitman’s poems. So even when word counts converge (as they often do, for example, when comparing the lines of the 1855 Leaves with the verse divisions in KJB-Psalms, -Proverbs, and -Job), it is frequently still the case that Whitman’s lines are more spatially expansive than the KJB’s verse divisions—they literally are lengthier on the page. And Whitman’s unconventional use of suspension points (….) and long dashes (combined with the large page format) in the first edition of Leaves elongates the line still further. The effect of the latter may be illustrated by comparing lines from the first edition of Leaves with lines from most of the succeeding editions where Whitman reverts to more conventional forms of punctuation and smaller page formats.88 The following examples are emblematic (LG, 14; LG 1856, 7; see Figs. 35–36):

LG 1855: “You shall no longer take things at second or third hand…. nor look through the eyes of the dead…. nor feed on the spectres in books”

LG 1856: “You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books”

LG 1855: “I have heard what the talkers were talking…. the talk of the beginning and the end”

LG 1856: “I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the beginning and the end”

LG 1855: “Always a knit of identity…. always distinction…. always a breed of life”

LG 1856: “Always a knit of identity, always distinction, always a breed of life”

The extra-linguistic means (esp. suspension points) for elongating Whitman’s lines, allied with their extreme lengths (by whatever count), makes clear that the poetry of the early editions of Leaves in particular “was a visual poetry,” as Asselineau notices.89 Whitman himself (at least late in life) recognized this as well:

Two centuries back or so much of the poetry passed from lip to lip—was oral: was literally made to be sung: then the lilt, the formal rhythm, may have been necessary. The case is now somewhat changed: now, when the poetic work in literature is more than nineteen-twentieths of it by print, the simply tonal aids are not so necessary, or, if necessary, have considerably shifted their character.90

Whitman experienced the Bible chiefly visually, in print and through reading, yet the biblical traditions (even when originating in written composition) emerge out of dominantly oral environments. Almost every dimension of biblical poetry is shaped for maximal oral and aural reception, including its typically constrained verse line.91 This is antithetical to Whitman’s visually oriented poetics—as Asselineau emphasizes, “who would, without getting out of breath, declaim the first Leaves of Grass; some of the lines contained over sixty words.”92

Fig. 35: P. 14 from the 1855 Leaves, https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/figures/ppp.00271.021.jpg.

Fig. 36: P. 7 from the 1856 Leaves, https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/figures/ppp.00237.015.jpg. Image courtesy of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Interestingly, as K. Campbell and Asselineau observe, over time Whitman’s line began to shrink back down toward more conventional lengths.93 The change already starts to appear in some instances by 1860 but begins in earnest with the (build-up to the) 1867 Leaves. Here is Campbell’s characterization:

In his earliest editions (1855, 1856, and 1860), there are a good many lines that run to thirty or forty words each, and a few that run as high as fifty and even sixty words. To be very specific, there are in the edition of 1856 two lines that run past sixty words each, seven that run past fifty words, sixteen that run past forty words, and forty-two that exceed thirty words each. At the same time there are no poems first published after 1870 with lines that run to as much as twenty-five words, and only one poem published in 1855 or 1856 that retained any considerable number of long lines,—namely, “Our Old Feuillage.” In fact, the longest line in any of the poems first published in the eighties comprises only twenty-one words (and there are only two examples of this), whereas the average long line in the poems written after 1880 runs to about a dozen words.94

Whitman achieves this foreshortening or lightening (as Asselineau calls it) in a number of ways, including breaking longer lines into multiple shorter lines, reducing the number of words in long lines through revision and emendation, and sometimes simply eliminating the long line entirely. Whitman’s “Blue Book” edition provides ample evidence of such revisionary practices, as it anticipates (though also differs significantly from) the 1867 edition.95 Consider the following by way of example.96 This fifty-four word line from “Come closer to me,”

Because you are greasy or pimpled—or that you was once drunk, or a thief, or diseased, or rheumatic, or a prostitute—or are so now—or from frivolity or impotence—or that you are no scholar, and never saw your name in print…. do you give in that you are any less immortal? (LG, 58)

is revised in the “Blue Book” into four shorter lines, with several cancellations:

Because you are greasy or pimpled,

Or that you was once drunk, or a thief, or diseased, or rheumatic, or a prostitute—or are so now,

or from frivolity or impotence, oOr that you are no scholar, and never saw your name in print,

Do you give in that you are any less immortal?97

Emendation is the method of reduction in this line from “Proto-Leaf” (LG 1860, 15): “And I will show that there is no imperfection in male or female, or in the earth, or in the present—and can be none in the future.” The nine canceled words in the “Blue Book” are dropped from succeeding versions of “Starting from Paumanok” (e.g., “And I will show that there is no imperfection in the present—and can be none in the future,” LG 1867, 16). And the following long line also from “Proto-Leaf” (LG 1860, 21) is canceled entirely in the “Blue Book” and does not appear in “Starting from Paumanok” in succeeding editions of Leaves (e.g., section 19; LG 1867, 21):

See the populace, millions upon millions, handsome, tall, muscular, both sexes, clothed in easy and dignified clothes—teaching, commanding, marrying, generating, equally electing and elective.

This program of foreshortening also impacted the overall scale of the poems. New poems in the later editions are generally shorter in length.98

It is useful to recall that Saintsbury’s appreciation of the “likeness” of Whitman’s poetry to the “verse divisions of the English Bible” was articulated in a review of the 1871–72 edition of Leaves, an edition well evidencing the consequences of Whitman’s program of lightening and trimming. There is, of course, more to the “likeness” observed than line-length (e.g., parallelism, rhythm, repetition, diction). However, it does show that the perception of lineal/divisional equivalence persists even without quantification and amidst much abbreviation on the poet’s part. Here Saintsbury’s specification of “especially… the poetical books” remains germane, as the verse divisions in this material only rarely approach the expanse of Whitman’s lengthiest lines (Fig. 29)—Whitman hardly needed to mechanically count words or letters (which of course he could do, and on occasion did) to apprehend the force of the biblical paradigm.

Ideally, Whitman quoting a bit of biblical verse within the format of his mature line, either from the notebooks and early poetry manuscripts or in Leaves—akin, for example, to his close version of Matt 26:15 in “Blood-Money” (lines 12–14) would nicely cinch the observations just made. Unfortunately, so far I have not uncovered any such quotations (or seen such discussed). This makes sense, since by the early 1850s Whitman was evolving a poetic theory that forbade explicit quotations from literature like the Bible in his verse. While there are echoes of, allusions to, and even some phrasing from the Bible in Leaves, there are no explicit quotations or close paraphrases. And, indeed, none either in the pre-1855 notebooks or early poetry manuscripts where Whitman’s long line is being worked and stretched into existence. Whitman only quotes the Bible in his prose writings—and he does that voluminously—and in his poetry from 1850 or earlier.99 The closest I have been able to come to this sort of “catching out” is in passages where Whitman’s lines have a stronger than normal resemblance to biblical material. An example was briefly discussed in Chapter Two. The line from “I celebrate myself,” “Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and joy and knowledge that pass all the art and argument of the earth” (LG, 15), has the shape, feel, rhythm, and some phrasing (“peace… that pass all”) of Phil 4:7. The biblical material that provokes Whitman in this instance is prosaic and from the New Testament, although that the provocation is circumscribed precisely by the KJB’s verse divisions is both readily apparent and significant.

Also from “I celebrate myself” is this example, where the probable biblical stimulant is poetic: “The pleasures of heaven are with me, and the pains of hell are with me” (LG, 26). This line does not quote or allude to a biblical passage, nor is it aiming to riff on a biblical theme. But it does borrow a phrase (“pains of hell”) from Ps 116:3 and is shaped parallelistically very much like the first two-thirds of the biblical verse: “The sorrows of death compassed me, and the pains of hell gat hold upon me: I found trouble and sorrow.”100 The verse from the psalm is actually a triplet in the Hebrew original, so the final “I found trouble and sorrow” has no counterpart in Whitman’s two-part line. The bipartite shape of the latter is more directly comparable to Ps 18: 5 (=2 Sam 22:6): “The sorrows of hell compassed me about: the snares of death prevented me.” While the psalms’ synonymous parallelism focuses two different names for the underworld (“death,” Hebrew māwet; “hell,” Hebrew šĕʾôl), Whitman opts for a more antithetical feel (pleasures/pains) with a biblical merism, heaven and hell (e.g., Amos 9:2; Ps 139:8; Job 11:8; Matt 11:23; Luke 10:15). Still, the sets are remarkably close in feel and form. And again the general pattern of line-length correspondences briefly sketched earlier holds. The lengths of Whitman’s line (fifteen words) and of the KJB verse division of the two psalm verses (Ps 116:3, excepting the last phrase, fifteen words; Ps 18:5, thirteen words) are closely comparable, and they all contrast markedly with the consistently short biblical Hebrew poetic line. The latter are more aptly rendered in a translation such as the ASV:

The cords of death encompassed me:

And the pains of Sheol gat hold upon me;

I found trouble and sorrow. (Ps 116:3)

The cords of Sheol were round about me;

The snares of death came upon me. (Ps 18:5 = 2 Sam 22:6)

The component lines are half the length of the KJB verse division and Whitman’s line and offer a much better approximation of the terse biblical Hebrew lines being translated, which in the Hebrew of these psalmic verses do not exceed more than three words.

Consider further this run of lines from the beginning of “I celebrate myself”:

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

Have you practiced so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems? (LG, 14)

And the similar set from “To think of time”:

Have you guessed you yourself would not continue? Have you dreaded those earth-beetles?

Have you feared the future would be nothing to you? (LG, 65)

Both have the feel and cadence of similarly phrased rhetorical questions posed to Job in the Yahweh speeches toward the end of the book of Job:

Hast thou commanded the morning since thy days; and caused the dayspring to know his place; (Job 38:12)

Hast thou entered into the springs of the sea? or hast thou walked in the search of the depth?

Have the gates of death been opened unto thee? or hast thou seen the doors of the shadow of death?

Hast thou perceived the breadth of the earth? declare if thou knowest it all. (Job 38:16–18)

Hast thou entered into the treasures of the snow? or hast thou seen the treasures of the hail, (Job 38:22)

Hast thou given the horse strength? hast thou clothed his neck with thunder? (Job 39:19)

Hast thou an arm like God? or canst thou thunder with a voice like him? (Job 40:9)101

Whitman greatly admired Job and certainly was familiar with the Yahweh speeches.102 The language has been modernized (e.g., “Have you”)103 and the subject matter is unique to Whitman,104 but the run itself is reminiscent of Job (esp. 38:16–18) and the two-part lines in particular (“Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?” [thirteen words]; “Have you guessed you yourself would not continue? Have you dreaded those earth-beetles?” [thirteen/fourteen words]) in pattern and length are very close to the biblical prototype. Still, Whitman’s lines do not quote or allude to Job but rather have a biblicized feel or “flavor” about them, including their scale.

Two final examples, one from “To think of time” and the other from “I celebrate myself,” both of which feature the archaic “he that” in proverb-shaped sayings: “He that was President was buried, and he that is now President shall surely be buried” (LG, 66; sixteen words) and “He that by me spreads a wider breast than my own proves the width of my own” (LG, 52; sixteen words). The first is shaped as a two-part, internally parallelistic line of a kind that is especially common in the Bible’s wisdom books:

He that is surety for a stranger shall smart for it: and he that hateth suretiship is sure. (Prov 11:15; eighteen words)

He that hath a froward heart findeth no good: and he that hath a perverse tongue falleth into mischief. (Prov 17:20; nineteen words)

He that getteth wisdom loveth his own soul: he that keepeth understanding shall find good. (Prov 19:8; fifteen words)

He that observeth the wind shall not sow; and he that regardeth the clouds shall not reap. (Eccl 11:4; seventeen words)

He that findeth his life shall lose it: and he that loseth his life for my sake shall find it. (Matt 10:39; twenty words)

This sort of saying can also be antithetically shaped:

He that walketh uprightly walketh surely: but he that perverteth his ways shall be known. (Prov 10:9; fifteen words)

He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes. (Prov 13:24; sixteen words)

Although the content of Whitman’s line is not overly didactic, his use of the biblical phrases “he that” (764x in KJB) and “shall surely” (65x in KJB) gives the whole a distinctly biblical feel. The usage of the archaic “he that” is all the more marked (in hindsight) as it all but drops out of modern English translations of the Bible (e.g., RSV: 36x—mostly replaced by “he who”). In fact, Whitman uses the phrase four other times in the 1855 Leaves (LG vii, 27, 75, 91) and “she that” once, in a phrase (“she that conceived,” LG, 91) with its own biblical genealogy (Hos 2:5; cf. 1 Sam 2:5; Prov 23:25; Jer 15:9; 50:12).

The second line, much more sagacious in tone and content, also finds many biblical counterparts of similar shape and scale:

He that followeth after righteousness and mercy findeth life, righteousness, and honour. (Prov 21:21; twelve words)

He that deviseth to do evil shall be called a mischievous person. (Prov 24:8; twelve words)

He that rebuketh a man afterwards shall find more favour than he that flattereth with the tongue. (Prov 28:23; seventeen words)

He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. (Ps 91:1; nineteen words)

Intriguingly, Martin Farquhar Tupper, a contemporary of Whitman’s who was only too happy to mime biblical maxims, uses the archaic “he that” twenty-two times in his 1838 edition of Proverbial Philosophy, a copy of which Whitman owned and marked up (see below).105 Most of these are similar in shape and scale to their biblical models and to Whitman’s two lines, including “He that went to comfort, is pitied; he that should rebuke, is silent” (p. 135; thirteen words) and “And he that hath more than enough, is a thief of the rights of his brother” (p. 150; sixteen words). The latter is among the four lines Whitman brackets on that page. This is quintessential Whitman as a poet-compositor, absorbing the language of others (here from the Bible) and turning it to his own ends: “The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet…. he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you” (LG, vi; for the biblical allusion, see Luke 5:23; John 5:8; Matt 9:5; Mark 2:9; cf. John 11).106

Variability in Line-Length

Moreover, it is the mix of line lengths in Whitman’s poetry that is also telling. Whitman’s line is not monolithic, as the chronological overview offered above makes apparent. If characteristically long (especially in the early editions of Leaves), it is also stubbornly variable. As Allen notices, what is most consistent about it is its “clausal structure,” “each verse [is] a sentence.”107 But the “sentence” can be relatively short (“I celebrate myself,” LG, 13; three words)—Whitman, of course, started out writing metered verse with lines of conventional lengths, and these shorter lines remain a part of his lineal repertoire;108 or really long (“If I and you and the worlds and all beneath or upon their surfaces, and all the palpable life, were this moment reduced back to a pallid float, it would not avail in the long run,” LG, 51; thirty-six words); or most often somewhere in between (“A gigantic beauty of a stallion, fresh and responsive to my caresses,” LG, 35; twelve words). The undoing of meter not only made possible the increased scale of Whitman’s poetic line, it also opened the way to lineal variability, the capacity to shape the sentential wholes out of which Whitman’s lines were normally configured as desired, without external constraints.

The Bible, too, in the familiar bi-columnar format of the KJB, is most immediately experienced as a mass of sentences of varying lengths segmented by verse (and chapter) divisions. The degree of variability and its underlying sources depends on what part of the Bible is in view. The poetic sections of the (Hebrew) Bible offer the most regularity, since the verse divisions in this material usually circumscribe groupings of two, three, four, and sometimes more poetic lines of roughly equivalent lengths. But even here variability is normative. The biblical poetic line itself, though roughly equivalent (especially within couplets and triples) and ultimately constrained, nevertheless varies in length (normally from five to twelve syllables or three to five words). And since the verse divisions distinguish groupings of this variable line, the pattern of grouping that prevails in any one corpus—sometimes more regular (as with the almost unfailing preference for couplets in Proverbs and parts of Job), sometimes less so (Psalms, Song of Songs, and much prophetic poetry, for example, feature unscripted blends of grouping strategies)—adds yet a further parameter of variability.

The magnitude of such variability increases dramatically when the underlying (Hebrew and Greek) prose portions of the Bible are considered alongside the poetic. In these sections, the verse divisions of the KJB usually reflect the sentential structure of the underlying prose. There are no (explicit) length constraints on these prose sentences, whether translated from Hebrew or Greek.109 They can be long or short, and length considerations are not prominent in determining the overall discourse logic of a passage of prose. That is, short sentences may follow upon long ones, or not, for seemingly indiscriminate reasons. Regardless, what is presented to the English reader of the KJB, almost no matter which portions of scripture are in view, are blocks of prose sentences of varying lengths set off in verse divisions (and thus made visually uniform). Like the long lengths of Whitman’s prototypical line—two, three, and often four times as long as the typical biblical Hebrew verse line (in translation)—the variety of these lengths finds a ready analog in the verse divisions in the KJB. Whitman’s own image for his line play—“the [regular] recurrence of lesser and larger waves on the sea-shore, rolling in without intermission, and fitfully rising and falling”110—also well describes the mix of the verse divisions in the KJB, and in the poetic books in particular, and the ebb and flow of their rhythm.

That Whitman’s writing should bear the imprint of both biblical poetry and biblical prose follows from various considerations. Whitman’s trackable quotations, allusions, and echoes come equally from prose and poetic sources in the Bible; the whole Bible was thought of as “poetry” in the nineteenth century, as C. Beyers observes,111 and certainly Whitman, even allowing on his part for an appreciation of the genuinely poetic parts of the Old Testament, shared this larger understanding, especially explicit in “Bible as Poetry”—“all the poems of Orientalism, with the Old and New Testaments at the centre”;112 and the uniform nature of the KJB’s formatting, with only the subtlest differences in whitespace to distinguish (underlying) verse from prose, would itself dispose readers to a uniform treatment of the whole Bible.113 This double-sided impact is no small matter, since there are few sources that can match the English Bible’s diversity of styles. That is, one of the key indicators of the significance of the verse divisions in the KJB for considering Whitman’s line is precisely the great diversity of styles, rhythms, and the like that they enfold, composed as they are of material ultimately drawn from poetry as well as prose—and a plethora of kinds, genres, styles in both media. There are likely not many other sources available to Whitman that match his own breadth and variety.114 As will become more apparent, the KJB does not just provide a singular point of contact with Whitman’s evolving sense of a line, viz. its expanded length, but many such points, and they are diverse in nature.

Caesuras in Whitman

Beyond the gross scale of Whitman’s lines, what takes place in them is also often redolent of what is found in the KJB’s verse divisions, especially in the poetic books. Consider the nature of caesuras in Whitman—caesura here being understood as “syntactic juncture or pause between phrases or clauses, usually signaled by punctuation, but sometimes not,” that is present in every sentence of any length.115 Whitman’s caesural division is usually marked by punctuation—“his internal commas and dashes are also often caesural pauses”116—as in the following handful of examples, taken from the beginning of “I celebrate myself”:

I lean and loafe at my ease…. observing a spear of summer grass.

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes…. the shelves are crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself, and know it and like it,

The atmosphere is not a perfume…. it has no taste of the distillation…. it is odorless,

The sniff of green leaves and dry leaves, and of the shore and darkcolored sea-rocks, and of hay in the barn, (LG, 13)

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand…. nor look through the eyes of the dead…. nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me, (LG, 14)

Or the absence of explicit punctuation:

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself. (LG, 14)

As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side all night and close on the peep of the day,

And leaves for me baskets covered with white towels bulging the house with their plenty,

Shall I postpone my acceptation and realization and scream at my eyes,

Looks with its sidecurved head curious what will come next, (LG, 15)

One significance of Whitman’s pattern of caesural division lies in its close correspondence to the major syntactic (and phrasal) divisions, also mostly marked through punctuation, in the larger verse divisions of the poetic material in the KJB. Consider as but one example part of the opening section of the Song of the Sea (Exod 15:2–8):

2The LORD is my strength and song, and he is become my salvation: he is my God, and I will prepare him an habitation; my father’s God, and I will exalt him.

3The LORD is a man of war: the LORD is his name.

4Pharaoh’s chariots and his host hath he cast into the sea: his chosen captains also are drowned in the Red sea.

5The depths have covered them: they sank into the bottom as a stone.

6Thy right hand, O LORD, is become glorious in power: thy right hand, O LORD, hath dashed in pieces the enemy.

7And in the greatness of thine excellency thou hast overthrown them that rose up against thee: thou sentest forth thy wrath, which consumed them as stubble.

8And with the blast of thy nostrils the waters were gathered together, the floods stood upright as an heap, and the depths were congealed in the heart of the sea.

These divisions are punctuated by clausal and phrasal units, typically set off by commas, colons, and semicolons, in a manner analogous to Whitman’s caesuras—especially as regards the number of such divisions (per verse) and their characteristic length and syntactic integrity. The source of the major syntactic junctures in these verse divisions, as will be clear from the earlier discussion, is the underlying biblical Hebrew poetic line structure that gets embedded in the verse divisions of the KJB. This becomes immediately obvious, again, by either comparing the original Hebrew or a translation, such as Moulton’s below,117 that explicitly intends to show off the original verse structure:

The LORD is my strength and song,

And he is become my salvation:

This is my God, and I will praise him;

My father’s God, and I will exalt him.

The LORD is a man of war:

The LORD is his name.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his host hath he cast into the sea:

And his chosen captains are sunk in the Red sea.

The deeps cover them:

They went down into the depths like a stone.

Thy right hand, O LORD, is glorious in power:

Thy right hand, O LORD, dasheth in pieces the enemy.

And in the greatness of thine excellency thou overthrowest them that rose up against thee:

Thou sendest forth thy wrath, it consumeth them as stubble.

And with the blast of thy nostrils the waters were piled up,

The floods stood upright as an heap,

The deeps were congealed in the heart of the sea.

The correspondence in length, cadence, and syntactic integrity between Whitman’s caesural divisions, the major syntactic junctures in the poetic parts of the KJB, and the individual biblical Hebrew verse line (in translation) is most striking.

Not surprising, then, the caesural divisions of Whitman’s longer lines may even stand on their own as singular lines. For example, the first caesural division set off by suspension points in “Or I guess the grass is itself a child…. the produced babe of the vegetation” two lines later appears as a line of its own, “Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic” (LG, 16). Compare also the following sequence:

Walking the path worn in the grass and beat through the leaves of the brush;

Where the quail is whistling betwixt the woods and the wheatlot,

Where the bat flies in the July eve…. where the great goldbug drops through the dark;

Where the flails keep time on the barn floor…. (LG, 36)

And:

Ever the hard and unsunk ground,

Ever the eaters and drinkers…. ever the upward and downward sun…. ever the air and the

ceaseless tides…. (LG, 47)

Allen observes similarly that “sometimes the caesura divides the parallelism and is equivalent to the line-end pause” (emphasis added).118 That, in fact, Whitman thought very much along these lines is suggested by how he reshapes the 1850 “Resurgemus” into what becomes the eighth poem of the 1855 Leaves. Mostly his adaptation consists in relineating, in combining the shorter lines of the 1850 poem into single, longer lines in Leaves.119 For example, “For many a promise sworn by royal lips/ And broken, and laughed at in the breaking” becomes the single line, “For many a promise sworn by royal lips, And120 broken, and laughed at in the breaking” (LG, 88). In another example a five-line section is recombined into two long lines:

But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter destruction,

And frightened rulers come back:

Each comes in state, with his train,

Hangman, priest, and tax-gatherer,

Soldier, lawyer, and sycophant; (“Resurgemus”)

But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter destruction, and the frightened rulers come back:

Each comes in state with his train…. hangman, priest and tax-gatherer…. soldier, lawyer, jailer and sycophant. (LG, 88)

In both examples, what becomes caesural divisions in Leaves once stood literally as singular lines in “Resurgemus.”

Line-Internal Parallelism

A related consideration arises in what Allen calls “internal parallelism.” In noting dissimilarities between Whitman’s and the Bible’s use of parallelism, Allen observes, “As a rule it is easier to break up Whitman’s long lines into shorter parallelisms (‘internal’, we shall call them), though this can be done with some biblical lines and cannot be done with many of Whitman’s shorter lines.”121 He goes on, with some minor equivocation, to say, “Perhaps Leaves of Grass contains more internal parallelism than the poetry of the Bible.”122 No equivocation is necessary. While there is line internal parallelism within biblical Hebrew verse,123 it is not nearly so prominent as in Whitman.124 And the reason why this is so is also the telling point. Again, Allen is befuddled because he is comparing apples (mostly) and oranges, the Hebrew line of biblical verse (or a presumed translation equivalent thereof) and Whitman’s line. They are not comparable. But when one recalibrates and compares, instead, Whitman’s line and the verse divisions in the KJB, then the view quickly comes into focus. If the biblical Hebrew verse line only sparingly exhibits line-internal parallelism (because it often lacks the necessary scale), the verse divisions of the KJB in the poetic books are rife with it because they are themselves most often translations of sets of parallel lines. The only biblical example of line-internal parallelism that Allen quotes is Ps 19:2–4, which he lays out in the following manner:125

|

(a) |

Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge, |

|

(b): |

There is no speech nor language; their voice cannot be heard. |

|

(c) |

Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. |

Tellingly, this does not appear to be Moulton’s rendition, which both originally and in the volume Allen claims to cite, replicates the RV, a fair English version of the underlying Hebrew line structure:

Day unto day uttereth speech,

And night unto night sheweth knowledge.

There is no speech nor language;

Their voice cannot be heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth,

And their words to the end of the world.126

The wording of Allen’s citation is the same—whether taken from Moulton or from the RV itself—though lined according to the verse divisions of the KJB—albeit in a schematized manner:

Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge.

There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world.

Interestingly, Allen’s confused version of Ps 19:2–4 shows what he claims it shows, namely, line-internal parallelism of the kind commonly found in Whitman, though admittedly not quite in the way that he imagines. The underlying Hebrew lines have no such line-internal parallelism, as Moulton’s version makes clear. Rather, the source of the putative internal parallelism in this example is the verse divisions of the KJB, each containing the translation equivalent to a parallel couplet in the original Hebrew. So here, too, there is a match between the KJB (verse divisions) and Whitman’s line. And as significant the trope is common in both corpuses (see Chapter Four).