4. Parallelism: In the (Hebrew) Bible and in Whitman

©2024 F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0357.05

Whitman no doubt is the greatest virtuoso of parallel structure in English poetry

— G. Kinnell, “‘Strong is Your Hold’: My Encounters with Whitman” (2007)

The Politics of Parallelism

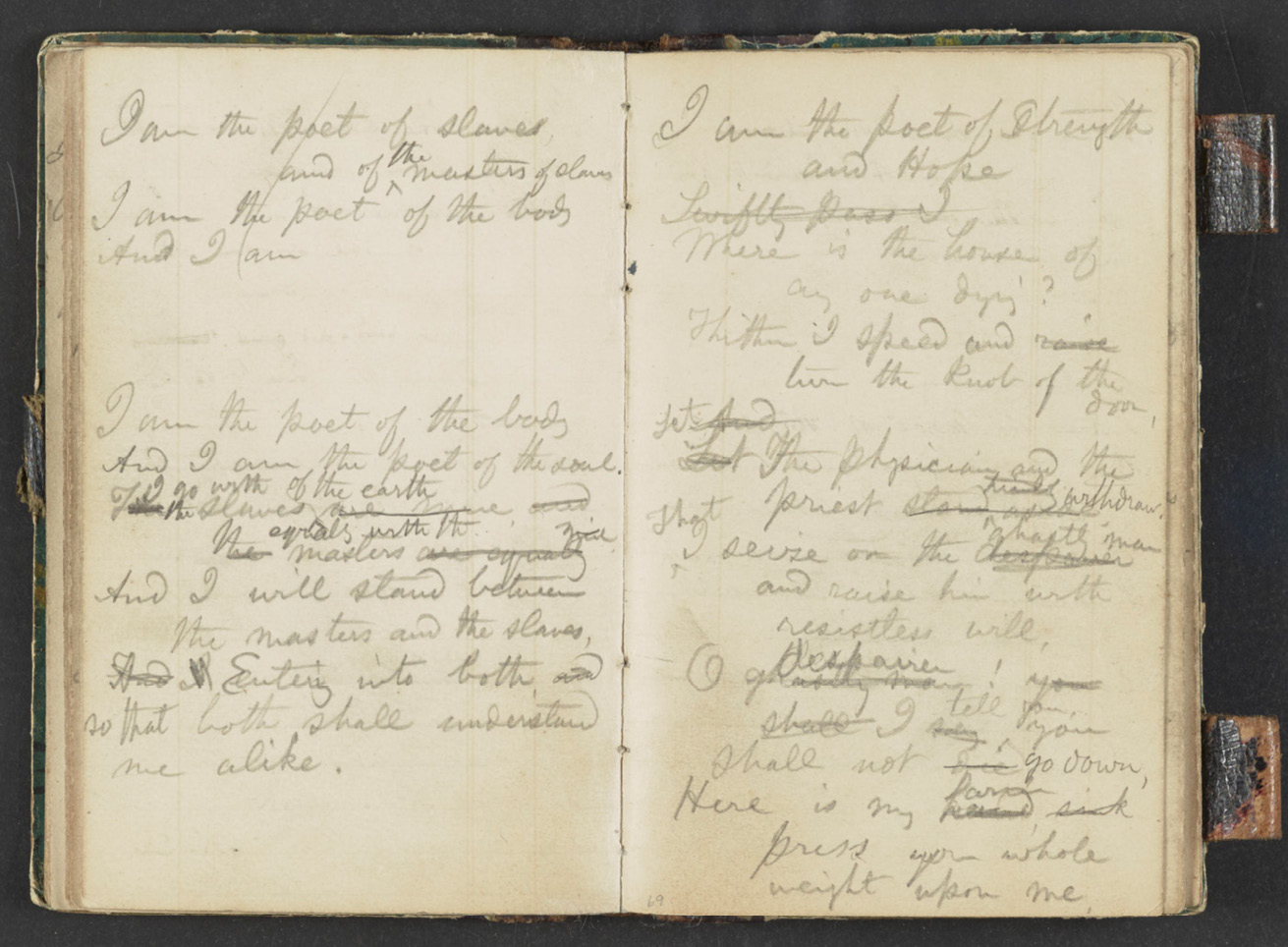

For most of the twentieth century, the “Talbot Wilson” notebook1—perhaps Whitman’s most important surviving notebook for understanding the initial stages of composition of the 1855 Leaves—was thought to date from 1847.2 Consequently, the initial lines of verse that appear in this notebook (approximately halfway through) have attracted much scholarly attention (Fig. 47)3:

I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves

I am the poet of the body

And I am4

Noting the “impress of the slavery issue” on these lines presumed to be Whitman’s first that approximate the free verse of the 1855 Leaves, B. Erkkila writes:

The lines join or translate within the representative figure of the poet the conflicting terms of master and slave that threaten to split the Union. Essential to this process of translation are the strategies of parallelism and repetition, which, as in the democratic and free-verse poetics of Leaves of Grass, balance and equalize the terms of master and slave within the representative self of the poet. By balancing and reconciling the many within the one of the poet, Whitman seeks to reconcile masters and slaves within the larger figure of the E PLURIBUS UNUM that is the revolutionary seal of the American republic.5

This is an incisive analysis. Erkkila appreciates how thoroughly fused were this hyperly holistic poet’s poetics and politics. The internally parallelistic line (“I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves”), which Whitman collages from the King James Bible (e.g., “I am become a stranger unto my brethren, and an alien unto my mother’s children,” Ps 69:8; for details, see below), is essential to the “balancing and reconciling” the poet’s gesture of bodily encompassment effects. By setting identical prepositional frames in equivalence (“of” + Obj// “and of” + Obj), the elements filling these frames (the prepositional objects “slaves” and “masters of slaves”) “are brought into alignment as well.”6 And this “alignment” is ramified syntactically as both prepositional objects are made to modify a single nominal, “poet.” Whitman’s poetic response to the political dilemma is to balance (“one part does not need to be thrust above another,” LG, vi) and join the conflicting extremes within his democratically expansive poetic-I (“I reject none, accept all, reproduce all in my own forms,” LG)—the fully embodied nature of this “I” is underscored in the 1855 Leaves by the engraved daguerreotype of the poet that fronts and introduces that volume.7

Fig. 47: Leaves 35v–36r of the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss454430217. Leaf 35vs is the point in the notebook where Whitman begins experimenting with trial lines in verse. Image courtesy of the Thomas Biggs Harned Collection of the Papers of Walt Whitman, 1842–1937, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. MSS45443, Box 8: Notebook LC #80.

The initial lines are finally canceled and Whitman begins afresh:

I am the poet of the body

And I am the poet of the soul

The I go with the slaves of the earth are mine, and the equally with the masters are equally mine8

And I will stand between the masters and the slaves,

And I Entering into both, and so that both shall understand me alike.

These lines seem to be a variation on the same strategy, and importantly parallelism continues to figure prominently. The poet asserts his embodied integrity in the famous parallelistic couplet that survives into the 1855 Leaves (LG), albeit there decoupled from any slavery issue.9 As M. Klammer observes, “Here the two sides of the divided self—body and soul—are reconciled, and that reconciliation seems to make possible the poet’s egalitarian joining of himself with both slaves and masters.”10 In the 1855 Preface Whitman proclaims the poet to be “the equalizer of his age and land” (LG, iv). The next line originally offered another attempt to absorb parallelistically slaves and masters within the poet’s holistic self: “The slaves are mine, and the masters are equally mine.”11 The line is revised. The assertion of possession (“mine”) is perhaps judged inappropriate.12 In the revision the poet (as “the equable man” to come, LG, iv) is imagined as going (body and soul) equally with slaves and masters. Whitman next places the poet’s body (and soul) “between the masters and the slaves”—the only line not caught up in the play of parallelism. The last line on the notebook page takes a tack opposite to that of the first. Instead of absorbing masters and slaves into the poetic-I (“And I” is canceled), now the poet enters both (through his poetry?)13 “so that” both may understand him “alike,”14 and thus presumably become accommodated through such bodily mediation.

The analysis remains equally insightful and significant now that the “Talbot Wilson” notebook is more securely dated to 1854 and its first poetic lines are known not to be Whitman’s first free-verse lines. Parallelism is a trope that is vital to the democratic and free-verse poetics that Whitman develops over the course of the early 1850s. In fact, though the political calculations are different, parallelism (however embryonic) already features in Whitman’s very first free-verse lines, those in “Blood-Money”15 (from the spring of 1850). Here, too, the Bible and slavery are very much in view as Whitman imagines “the Beautiful God, Jesus” (line 2), having taken on “man’s form again” (line 19), as a “hunted” fugitive slave (lines 20–27):

Thou art reviled, scourged, put into prison;

Hunted from the arrogant equality of the rest:

With staves and swords throng the willing servants of authority;

Again they surround thee, mad with devilish spite—

Toward thee stretch the hands of a multitude, like vultures’ talons;

The meanest spit in thy face—they smite thee with their palms;

Bruised, bloody, and pinioned is thy body,

More sorrowful than death is thy soul.

Parallelism in these lines does not balance or reconcile opposing sides but through its doubling movement concentrates and reiterates the abuse paid to the fugitive Christ (e.g., “throng the willing servants of authority;”// “Again they surround thee….,” lines 22–23; “The meanest spit in thy face”// “they smite thee with their palms,” line 25) and figures the holism of the hurt in a body-soul merism (lines 26–27) that anticipates the later lines from the “Talbot Wilson” notebook (and beyond).

Parallelism continues to figure into Whitman’s political calculations on the theme in the early editions of Leaves. An outstanding example comes from the 1856 “Poem of Many In One”:

Slavery, the tremulous spreading of hands to shelter it—the stern opposition to it, which ceases only when it ceases. (LG)

The line is culled from the prose of the 1855 Preface (“slavery and the tremulous spreading of hands to protect it, and the stern opposition to it which shall never cease till it ceases or the speaking of tongues and the moving of lips cease,” LG). It divides into two parts and is internally parallelistic. The long dash halves the line. Here Whitman exploits what in the Lowthian system of biblical parallelism is known as “antithetical parallelism,” a form of parallelism in which opposites are posed (e.g., “The wicked flee when no man pursueth: but the righteous are bold as a lion,” Prov 28:116). Such posing can be scripted to different ends. In this instance, Whitman means to hold the opposing perspectives together without resolving their central antagonism—the holism of the trope containing the centrifugal pull of its content. After the war, Whitman’s political perspective shifts. The internal parallelism of the line is exploded minus the need to contain opposing views, and the line itself morphs into two lines, both of which angrily decry the “conspiracy” to impose slavery more broadly and its consequences (of which there is no “respite”):

Slavery—the murderous, treacherous conspiracy to raise it upon the ruins of all the rest;

On and on to the grapple with it—Assassin! then your life or ours be the stake—and respite no more. (LG)

The breakdown in parallelism is emblematic of the lines’ prevailing sense of exhaustion and ongoing uncertainty—the trope (in this instance) can no longer conform (to) the political calculus.

From the very beginning, then, Whitman’s new American verse, in addition to being freed from meter and rhyme and whatever political regimes these symbolize, relies heavily on the reiterative play of a parallelism seemingly always equally posed prosodically and politically. To reflect on the place of parallelism in Whitman’s poetry and its possible debt to the Bible is to reflect on part of what is foundational to Whitman’s art.

* * *

In what follows I offer an explication of parallelism in three movements. In the first I review (in broad strokes) the discussion of parallelism in biblical scholarship from Robert Lowth (mid-eighteenth century) to the present. Because of the wide influence of G. W. Allen and his early essay “Biblical Analogies for Walt Whitman’s Prosody,”17 Whitman scholarship is peculiarly indebted to biblical scholarship for its understanding of parallelism. Unfortunately, Allen’s own understanding of parallelism in biblical (Hebrew) poetry is both flawed and (now) dated. My ambition in reviewing the status of the question about parallelism in biblical scholarship is to give students of Whitman both updated understandings of parallelism in the biblical poetic corpus as currently conceptualized by biblical scholars and ideas for exploring Whitman’s uses of the trope (prosodically and otherwise)—Biblical Studies is one discipline of textual study in which parallelism has been robustly theorized and those theorizations (multiple and contested) are eminently translatable and transferable. In the second part of the chapter I return to one of Allen’s central concerns in “Biblical Analogies,” namely, to indicate more precisely (now in light of a better understanding of the biblical paradigm) what in Whitman’s uses of parallelism is suggestive of and/or indebted to the Bible. My principal focus here is what Allen describes as “internal parallelism”—where “Whitman’s long lines” break “into shorter parallelisms.”18 The last section is the briefest. Here I point out a number of ways in which Whitman develops his uses of parallelism beyond the models he found in the KJB. These latter observations are intentionally gestural and heuristic. Enough is said to illuminate once again how Whitman, upon finding the ready-made he is collaging (this time a trope), shapes and makes it his own. As J. P. Warren states with regard to parallelism in particular, “Whitman does not content himself with the forms of biblical poetry.”19

Lowth’s Idea of Parallelism and Its Modern Reception

The question of parallelism in Whitman’s poetry since 1933 and Allen’s seminal essay, “Biblical Analogies,” has been deeply entangled with the idea of parallelism in biblical (Hebrew) poetry. Inspired by B. Perry’s belief that Whitman’s prosodic model in Leaves “was the rhythmical pattern of the English Bible,” Allen sought, first, “to determine exactly why the rhythms of Whitman have suggested those of the Bible…, and second to see what light such an investigation throws on Whitman’s sources.”20 Of these two large aims, Allen regarded the first “as more important because it should reveal the underlying laws of the poet’s technique.”21 The second aim, what can be said positively of Whitman’s use of the Bible as a resource, which Allen tackles most forthrightly in “Biblical Echoes,” serves chiefly to provide warrant for Allen’s recourse to biblical analogies as a means of elucidating Whitman’s free-verse prosody.22 In that analysis, parallelism, as understood primarily through Lowth’s biblical paradigm, figures prominently—the “first rhythmic principle” of both Whitman and the poetry of the Bible.23 Recall that at the time literary scholars were still casting around for ways to make sense of nonmetrical verse, a mostly new phenomenon (in the middle of the nineteenth century) in a poetic canon otherwise dominated since classical antiquity by meter. Allen sees in the analogy of biblical prosody the revelation of “specific principles” that enable a more perspicuous analysis and explanation of “Walt Whitman’s poetic technique.”24 The analysis, though problematic in places, successfully establishes (among other things) the presence and significance of parallelism in Whitman, especially as it bears on his underlying prosody, and the likelihood that the Bible is an important source of Whitman’s knowledge of parallelism.25 It also is important as an early effort at articulating a prosody that means to accommodate the differences of non-metrical verse.

I have detailed (some of) the confusions that attend Allen’s attempt to appropriate Lowth’s theory of parallelism in biblical Hebrew poetry for an understanding of parallelism in both the English Bible and in Whitman (see Chapter Three). Equally problematic, at least from a contemporary perspective, is Allen’s dependence on Lowth’s categorical scheme and developments thereof—to Lowth’s three-way scheme of synonymous, antithetical, and synthetic parallelism, Allen adds a fourth category, climactic parallelism, as suggested by one of his primary sources for knowledge of Lowth, S. R. Driver.26 Lowth’s paradigm was already 180 years old at the time of Allen’s first writing in 1933 and remained the conventional understanding of parallelism (with occasional supplementation as in Driver) in Biblical Studies for another fifty years. The late 1970s through the early 1990s saw a significant reorientation to the field’s understanding of parallelism in biblical poetry.27 Many of Lowth’s insights remain vital, though his overall categorization scheme is no longer sustainable.28

Phenomenologically, and at its broadest, parallelism is centrally concerned with correspondence, “the quality or character of being… analogous,” “correspondence or similarity between two or more things” (OED, meanings 1, 2), and its principal mode of manifestation (especially in the verbal arts) is through iteration or recurrence, a pattern of matching. As applied to prosody, the OED glosses parallelism as “correspondence, in sense or construction, of successive clauses or passages” (meaning 3). Lowth was the first to use the term with this sense, and specifically in his study of biblical Hebrew poetry (viz. parallelismus membrorum “parallelism between the clauses,” cf. OED). His analysis divides into two main parts: a general description and a threefold categorization scheme. His fullest general descriptions of parallelism are given in several places.29 The first is the most general and appears early in Lectures, in Lecture III:

In the Hebrew poetry, as I before remarked, there may be observed a certain conformation of the sentences, the nature of which is, that a complete sense is almost equally infused into every component part, and that every member constitutes an entire verse. So that as the poems divide themselves in a manner spontaneously into periods, for the most part equal; so the periods themselves are divided into verses, most commonly couplets, though frequently of greater length. This is chiefly observable in those passages which frequently occur in the Hebrew poetry, in which they treat one subject in many different ways, and dwell upon the same sentiment; when they express the same thing in different words, or different things in a similar form of words; when equals refer to equals, and opposites to opposites: and since this artifice of composition seldom fails to produce even in prose an agreeable and measured cadence, we can scarcely doubt that it must have imparted to their poetry, were we masters of the versification, an exquisite degree of beauty and grace.30

Parallelism will be named as such only later in the Lectures (esp. in Lecture XIX). Here, however, Lowth offers a first attempt to circumscribe the phenomenon. The first thing to notice is that Lowth directs his attention to the individual verse or line (the latter is the English term he will begin to use in his Preliminary Dissertation) and to the interlinear relations of immediately contiguous lines—“a certain conformation of the sentences.”31 The verse line in biblical poetry, Lowth observes, is typically composed of a part of a sentence or a clause, what he calls a “member”—“every member constitutes an entire verse”; and these clauses are mostly end-stopped, “a complete sense is almost equally infused into every component part,” i.e., line breaks occur at major clausal, phrasal, or sentential junctures. The poems divide into “periods” or sentences, “for the most part equal,” which “are divided into verses” (composed of clauses), “most commonly couplets,” but also triplets and larger groupings. This “conformation of the sentences,” Lowth emphasizes later in Lecture IV, is “wholly poetical.”32 In fact, continues Lowth, there is “so strict an analogy between the structure of the sentences and the versification that when the former chances to be confused or obscured, it is scarcely possible to form a conjecture concerning the division of the lines or verses.”33

The OED’s emphasis on correspondence in its definition of parallelism—“correspondence, in sense or construction, of successive clauses or passages” (meaning 3)—is essentially a gloss on Lowth’s own understanding of the concept. This is most obvious in the definition given in the Preliminary Dissertation, viz. “the correspondence of one Verse, or Line, with another,”34 which is the first authority cited by the OED.35 What this correspondence entails is variously described by Lowth, but his emphasis is generally consistent: it “consists chiefly in a certain equality, resemblance, or parallelism between the members of each period; so that… things for the most part shall answer to things, and words to words, as if fitted to each other by a kind of rule or measure.”36 As in his other statements, the intent is to gesture to a range of correspondences that may be observed, which as he emphasizes explicitly, “has much variety and many gradations.”37 One unfortunate consequence of how Lowth goes on to categorize parallelism is to limit how these correspondences would be conceptualized by later generations of scholars. However, the impulse of his more general description of the trope (or “ornament” as Lowth calls it in Lecture IV)38 is an expansive understanding of parallelism.

It is the (re)turn to linguistics by modern biblical scholars some two hundred years later that was a major stimulus for reassessing the nature of parallelism in biblical poetry. These scholars were able to expand and sophisticate Lowth’s original diagnosis with a whole panoply of new tools. A. Berlin’s Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism (1985) is paradigmatic as she, leveraging the work of R. Jakobson in particular, explores the play of parallelism beyond semantics at all levels of linguistic structure, including sound elements (phonetics), grammar (morphology and syntax), and words and their meanings (lexicon and semantics). The precision of the linguistic analysis is well advanced of what Lowth could achieve (in an era prior to the coalescence of linguistics as an academic discipline). But in this aspect the trajectory of analysis carries forward Lowth’s ideas,39 which remarkably foregrounds syntax as well as semantics, viz. “in Sense or Similar to it in the form of Grammatical Construction.”40 The place of syntax in Lowth’s thinking has been underappreciated as the reception of his ideas mostly (over)emphasized semantics. Allen is emblematic when he speaks of Whitman’s “thought rhythm” (his preferred gloss for parallelism, its “first principle”), a term he picked up from biblical scholarship.41

Berlin ultimately moves away from Lowth’s tight focus on “the conformation of the sentences” as the site of parallelism and resists his privileging of syntax and semantics, though she knows well that “grammatical and semantic parallelism generally co-occur” in biblical poetry.42 E. L. Greenstein and M. O’Connor more obviously carry forward Lowth’s focus on parallelism in biblical poetry as a line-level trope. Greenstein situates the phenomenon of parallelism structurally at the interface of “one line of verse” with “the following line or lines” and foregrounds the “repetition of a syntactic pattern.”43 This twofold focus means to challenge the view that “whatever goes on between two lines” of biblical Hebrew verse is meaningfully denominated as parallelism.44 For O’Connor, too, “the core of a [parallelism] is syntactic”—“the repetition of identical or similar syntactic patterns in adjacent phrases, clauses, and sentences.”45 He elaborates its inner workings (indebted to Jakobson’s thinking), “when syntactic frames are set in equivalence by [parallelism], the elements filling those frames are brought into alignment as well,” especially at the lexical level (semantics) but potentially (all) other linguistic levels may (also) be activated.46 Greenstein, in his revision of O’Connor’s entry on “Parallelism” in the newest version of The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, allows that while “the repeating structure is often syntactic in nature,” as prototypically in biblical Hebrew verse, “the repetition may entail other ling[uistic] components” (e.g., lexicon, morphology, rhythm).47 One of the gains, then, in the understanding of poetic parallelism in the Bible since the late 1970s is the renewed attention paid to syntax (and other levels of linguistic structure).

When a scholar such as Berlin writes that “most contemporary scholars have abandoned the models of Lowth and his successors,” what she has in view most particularly is Lowth’s categorization of parallelism into three “species”: synonymous, antithetical, and synthetic (or constructive). The criticisms are myriad and well made, chief among which is that the schema itself (especially as articulated in the Preliminary Dissertation) is unnecessarily reductive. What Lowth counts as three kinds of parallelism others have numbered as many as eight.48 The different ways of categorizing the same phenomena show that there is nothing necessarily absolute about Lowth’s threefold scheme. If anything, the latter, in particular, has had the effect of obscuring the subtleties of the trope and narrowing too much how it is conceptualized.49 And while one prominent line of discussion about parallelism following Lowth focused on supplementing and/or redescribing Lowth’s categories (e.g., complete, incomplete, numerical, impressionistic, repetitive, emblematic, internal, metathetic, climactic), what has become clear is that the varieties are endless and defy any neat classification scheme (however pragmatically handy certain descriptors may be for exposition).50

Lowth’s individual “species” are equally problematic. The “most frequent” kind of parallelism,51 according to Lowth, is “synonymous parallelism,” which he describes as that “which correspond one to another by expressing the same sense in different, but equivalent terms; when a Proposition is delivered, and is immediately repeated, in the whole or in part, the expression being varied, but the sense entirely, or nearly the same.”52 This conceptualization remains foundational for the field’s understanding of parallelism. However, the emphasis on semantics, both in Lowth’s denomination of the species (viz. synonymity) and in so much of his explication (though syntax, for example, is never ignored), meant that most treatments of parallelism after Lowth focused chiefly on semantic repetition,53 with many simply glossing parallelism, as J. L. Kugel contends, as “saying the same thing twice.”54 Exact synonymity—sameness without difference—does not exist.55 Contemporary scholarship has exposed the difference(s) that parallelism activates, revealing an infinite array of subtlety and nuance that had previously been occluded or neutralized by the emphasis on the same. Kugel and Robert Alter, among others, led the way in exploring the possibilities in parallelistic play beyond likeness, from emphasizing semantic coloring, focusing, intensification, ellipsis, and antithesis to elaborating incipient forms of narrativity.56 What has become of interest to biblical scholars is what takes place between the Lowthian parallel lines, or as a result of their combination, their being coupled in close adjacency. 57

“Antithetical parallelism” is the second species of parallelism described by Lowth: “when a thing is illustrated by its contrary being opposed to it. This is not confined to any particular form: for sentiments are opposed to sentiments, words to words, singulars to singulars, plurals to plurals, &c.”58 Lowth’s first example from Prov 27:6 is typical:

“The blows of a friend are faithful;

“But the kisses of an enemy are treacherous.”59

The contemporary critique here again is not what Lowth picks out for analysis but how he conceptualizes it. As Kugel quips, it is “a distinction without a difference.”60 That is, the focus remains on semantics—contrast or opposition instead of likeness; it is “another way” for what comes afterwards “to pick up and complete” what precedes.61 Moreover, O’Connor points out that this variety of parallelism “largely occurs” in the wisdom literature of the Bible (esp. Proverbs), making “it suspect as an independent category.”62

The last of the Lowthian categories is “Synthetic or Constructive parallelism,” wherein “the sentences answer to each other, not by the iteration of the same image or sentiment, or the opposition of their contraries, but merely by the form of construction.”63 The critique here is entirely different. If conceptualization and overemphasis on semantics are faulted in Lowth’s characterizations of synonymous and antithetical parallelism, most contemporary scholars nonetheless agree that the underlying phenomena diagnosed are of issue, that Lowth (and his predecessors) had identified an important feature of biblical verse. The problem with the third category is phenomenological. As G. B. Gray observed early on, while Lowth’s examples of synthetic parallelism “include, indeed, many couplets to which the term parallelism can with complete propriety be applied,” there are other examples “in which no term in the second line is parallel to any term in the first, but in which the second line consists entirely of what is fresh and additional to the first; and in some of these examples the two lines are not even parallel to one another by the correspondence of similar grammatical terms.”64 In short, many of the lines categorized under the rubric of “synthetic parallelism” exhibit no parallelism whatsoever. The category becomes a kind of catchall: “all such as do not come within the former two classes” “may be referred” to this final class.65 Lowth’s mistake is in pressing the idea of parallelism too far, in trying to make it account for the interrelations of all sets of lines in biblical verse. But to allow parallelism to cover every possible interlinear relationship in biblical verse, even where no ostensible signs of parallelism exist, is to make the idea of parallelism itself untenable, “undeniable.”66 Rather, as Gray contends, “the study of parallelism must lead… to the conclusion that parallelism is but one of the forms of Hebrew poetry.”67 Parallelism simply is not everywhere in the biblical corpus. Conservatively estimated, as much as a third of the corpus is composed of nonparallelistic lines.68 D. Norton, a non-biblicist, acutely draws out the logical implication of the presence of nonparallelistic lines that has all too often been missed even by specialists: “if there are unparallel lines, and parts of the poetry where parallelism is not apparent, it would seem that parallelism is not to be found everywhere in the poetry: consequently parallelism cannot be taken as the general system it is often thought of as being.”69

* * *

Given the prominence of Lowth’s ideas about parallelism in Allen’s explication of “biblical analogies” for Whitman’s prosody, the foregoing has focused principally on comprehending these ideas—especially the two main components of his understanding, his general description of the phenomenon and his classification scheme—and their modern scholarly reception. Together—Lowth’s ideas and their reception—these form the bedrock of contemporary understandings of biblical parallelism. The topic continues to attract scholarly attention. One last development in the study of parallelism that deserves mention here is parallelism’s rhythmic significance, especially in nonmetrical verse, like that of the Bible (and Whitman, too). Lowth could not conceptualize verse outside of a metrical framework. Even while he stresses that “nothing certain can be defined concerning the metre of the particular verses” of Hebrew poetry,70 he continues to think it “not improbable that some regard was also paid to the numbers and feet.”71 Still, he trusts his new kind of empirically grounded close reading, noticing the “measured cadence” effected by the rough regularity of the “conformation of the sentences” and the parallelistic play it sponsors.72 In fact, this “conformation of the sentences,” he says later, “has always appeared to me a necessary concomitant of metrical composition.”73 In the end, this “measured cadence” ultimately resists strict numerical quantification. And yet in its very articulation Lowth may be seen stretching the received ideas about metricality; indeed, as J. Engell well observes, Lowth “actually ends up providing a new, different kind of poetic original… [that] could not be reduced, despite his own efforts, to set meters.”74 This ultimately changes how poetry is imagined in the West (especially in English language poetry) and makes possible “the unrhymed verse without strict metrical scansion” of “Blake, Smart, Cowper, Macpherson, and Whitman.”75

Biblical scholarship more generally takes longer to absorb fully the consequences of Lowth’s expanded sensibility about what counts as metrical. Not until B. Hrushovski’s [Harshav’s] seminal “On Free Rhythms in Modern Poetry”—which aims to account prosodically for the rhythmic achievements of the kind of not-strictly-metrical verse inspired by Lowth—is a conceptual framework articulated for understanding the rhythm of biblical poetry beyond the positing of strict numerical regularity.76 Echoing Lowth, Hrushovski observes that “no exact regularity of any kind has been found” and thus by definition “the poetry of the Hebrew Bible” forms “a ‘natural’ free-rhythmic system.”77 Parallelism, in all of its variability, offers one set of parameters that may contribute to a given biblical poem’s overall rhythm. For example, in poems composed predominantly of parallelistic couplets and triplets (and not all biblical poems are so composed), the forward movement of the rhythm is periodically checked by moments of felt-stasis as the balancing and repetition at the heart of parallelism—one propositional gesture instinctively triggering another of like form and meaning—enact their bilateral pulse. There may be no better description and illustration of this rhythm than that provided by J. Hollander in his delightful imitation of it in English translation, viz. “Its song is a music of matching, its rhythm a kind of paralleling.”78

Parallelism, since Lowth’s celebrated analysis in the middle of the eighteenth century, is the best known characteristic of (much) biblical poetry, and, indeed, since the early 1990s, parallelism is now also the best understood feature of biblical poetry. Its many varieties and common tendencies, its basic mechanisms and informing structures, have been well researched, catalogued, and exemplified. If parallelism per se cannot be constitutive of biblical poetry—since there is a substantial amount of nonparallelistic lines in the biblical Hebrew poetic corpus—there is no denying its significance when present—the keenness of Lowth’s original insight continues to redound to this day.

Whitman and Biblical Parallelism: Line-Internal Parallelism

Having reviewed the question of parallelism in biblical poetry from a contemporary, post-Lowthian perspective, I want to return to a fresh consideration of the second of Allen’s two main aims in “Biblical Analogies,” namely, “to see what light such an investigation throws on Whitman’s sources.”79 That is, what (if anything) in Whitman’s use of parallelism is owed to the (English) Bible? Allen ultimately hedges some on this question. Among his main conclusions, he states: “It is certain, however, that Whitman could have learned (or ‘absorbed’) his first rhythmical principle from his extensive reading of the English Bible” (emphasis added).80 The chief evidence, on Allen’s accounting, is that as in the Bible Whitman features lines joined by synonymous, antithetical, synthetic, and climactic parallelism; and there is a great deal of line-internal parallelism as well, “which is found in the Bible almost as frequently as in Leaves of Grass.”81 So influential was Allen’s assessment that it became canonized in the entry on “parallelism” for the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics.82

A problem with Allen’s analysis is its reliance on a Lowthian inspired categorization scheme that contemporary biblical scholars no longer find compelling. This is more problematic for providing a framework for understanding Whitman’s free-verse prosody than for assessing what in his use of parallelism was inspired by the Bible, as Warren notices.83 Warren is chiefly critical of Allen’s emphasis on semantics, on “thought rhythm,” especially at the expense of paying attention to syntax.84 And he cites Kugel’s critique of Lowth’s categorization scheme in order to bolster his own contention that Allen’s “method…. for classifying Whitman’s rhythmical devices does not appear to be valid.”85 The spirit of Warren’s criticism is in line with the post-1970s work done by biblical scholars on parallelism. In fact, his own analysis could have been sharpened had he availed himself of more of the work reviewed above, especially those working from within an explicitly linguistic framework—Kugel is the only biblicist consulted, and he is not centrally interested in linguistic matters as they relate to parallelism. However, on the question of establishing a link between parallelism in the Bible and parallelism in Whitman, Warren thinks Allen succeeds: “By using the rhythm-producing syntax of the English Bible, Whitman connects himself with the impassioned voices of the Old Testament prophets.”86 The position, however, is more asserted than argued, with Warren seemingly content to rely on the field’s long-held presumption of biblical influence on Whitman.87

Warren correctly underscores the limited value of the Lowthian tripartite classification paradigm for unlocking the nature of Whitman’s prosody—or for that matter for simply getting a better understanding of the nature of parallelism in Whitman’s poetry. The paradigm, however flawed, nevertheless does permit (with some recalibration) some initial glimpses of what Whitman takes from the Bible with regard to this trope. Synonymous parallelism is a good example. This is “Whitman’s favorite form” and “no one can doubt” its presence in Leaves, writes Allen.88 The vast majority of Allen’s examples, in fact, involve synonymity of some kind. He even admits difficulty in distinguishing “the synonymous from the synthetic” in Whitman.89 In part the latter difficulty arises because synthetic parallelism, as discussed above, often is used in the Lowthian paradigm to classify sets of lines that do not exhibit any kind of parallelism. In Whitman, as in the Bible, there are many nonparallelistic lines of verse (of various sorts). The large observation to make about Whitman’s preference for synonymity is that semantics (meaning) is the linguistic element that most readily translates from one language into another. Putting aside Lowth’s own emphasis on semantics (an emphasis then bequeathed to succeeding generations of biblical scholars and through Allen to Whitman scholars), it is the semantic element of parallelism in biblical Hebrew poetry that carries over most visibly into the English translation of the KJB—and this despite the translators’ general ignorance of the phenomenon (as it later became diagnosed by Lowth). Therefore, if the Bible is one source of Whitman’s knowledge of parallelism, it is not surprising that he picks up most commonly semantic reiteration and reformulation (whether synonymous, antithetical, or whatever). The challenge is to be able to identify biblicisms in Whitman’s parallelistic play beyond the sheer presence of synonymity.

The likeliest place to locate a biblical genealogy for Whitman’s use of parallelism is in his “long lines,” which, as Allen astutely observes, often may be broken into “shorter parallelisms”—what Allen calls “internal parallelism.”90 “The smallest parallels in Whitman”—and H. Vendler says that “semantic or syntactic parallelism” is the “basic molecule of Whitmanian chemistry”—“comes two to a line.”91 These internally parallelistic lines (whether of two or three parts), as previously noted (see Chapter Three), are extremely common in Leaves and are one of the surest signs of the KJB’s imprint on Whitman’s mature style.92 The parallelistic couplet and triplet are the most dominant forms of line grouping in biblical Hebrew verse (isolated, ungrouped, singular lines are rare) and are inevitably rendered into two- and three-part verses (i.e., verse divisions) in the prose translation of the KJB. Mostly, of course, Whitman has just adopted this parallelistic substructure and fitted it out with his own language material. Still, the substructure itself and the prominence of semantic synonymity are important markers of a biblical genealogy. I have already identified a number of examples of internally parallel lines in Whitman in which other pointers to the Bible exist as well, the most striking being Whitman’s adaptation of the biblical graded number sequence (“two greatnesses—And a third”) in section 34 of “Proto-Leaf” (LG; cf. Prov 30:18–19; see ). Here I concentrate on examples of two-part, internally parallelistic lines from the 1855 Leaves, again highlighting those with biblical inflections of some kind.

Synonymity

I begin, however, with a selection of internally parallelistic lines featuring synonymity. I do so mainly as a reminder of the ubiquity of this line type in Leaves. These several examples, all taken from “I celebrate myself,” could be multiplied hundreds of times over:

“The pleasures of heaven are with me, and the pains of hell are with me” (LG

“This is the meal pleasantly set…. this is the meat and drink for natural hunger” (LG)

“Regardless of others, ever regardful of others” (LG)

“The woollypates hoe in the sugarfield, the overseer views them from his saddle” (LG)

“Hurrah for positive science! Long live exact demonstration!” (LG)

The first example I discuss also in Chapter Three. I repeat it here because the closeness of its phrasing to the first two-thirds of Ps 116:3 (“The sorrows of death compassed me, and the pains of hell gat hold upon me: I found trouble and sorrow”),93 although Ps 18:5 (= 2 Sam 22:6) brings the bipartite, parallelistic structure in Whitman more sharply into focus: “The sorrows of hell compassed me about: the snares of death prevented me.” The synonymity of the psalmic verses (e.g., “sorrows”// “pains”// “snares”; “death”// “hell”) contrasts with the antithesis of Whitman’s line (e.g., “pleasures”/ “pains”), pointed with a well-known biblical merism, “heaven”/ “hell” (e.g., Amos 9:2; Ps 139:8; Job 11:8; Matt 11:23; Luke 10:15). The semantic upshot of Whitman’s line is to signal (efficiently) the speaker’s absorption of all pleasure and pain.

The second example shows Whitman working with biblical material—namely, the Lord’s Supper tradition of the gospels and Paul (Matt 26:26–29; Mark 14:22–25; Luke 22:14–22: 1 Cor 11:17–34; see Chapter Three)—and shaping it into his own appositive, parallelistic phrasing. The repetition of “This is” in parallel syntactic frames holds “meal” and “meat and drink” together. The move from the abstract or general (“meal”) to the more concrete (“meat and drink”) is a typical semantic development activated in biblical parallelisms.94 The prepositional phrase in the second half of the line, “for natural hunger,” balances “pleasurably set” in the first half and at the same time counters the (presumed) spiritual nature of the Lord’s supper tradition.

The next two examples are intended to ramify an idea I have already begun making with the first two examples, namely, that there is more to appreciating parallelism in Whitman’s poetry than noting its facticity or categorizing it or even assessing its place in Whitman’s prosody (which is not insignificant). Attending to what takes place as a result of setting parallel syntactic frames in equivalence is perhaps the most significant takeaway from contemporary biblical scholarship for a better understanding of the dynamics of Whitman’s parallelism. In “Regardless of others, ever regardful of others” (LG) it is the difference between “regardless” and “ever regardful” that the parallel of-genitives bring into alignment. The defiant “Regardless of others” is provided with a deep empathy by its echo in “ever regardful of others.” The line “The woollypates hoe in the sugarfield, the overseer views them from his saddle” () comes amidst one of Whitman’s early and long catalogues (, 21–23) in which vignettes of people at work are strung together creating a tapestry of the American worker, all of which are absorbed by Whitman’s expansive “I” in the catalogue’s last line, “And such as it is to be of these more or less I am” ()—this is the parallelistic absorption strategy Whitman was experimenting with in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook discussed at the outset of this chapter, only now enacted on a much larger scale. Almost every line features SV word order with attendant adjuncts (e.g., objects, prepositional phrases, adverbials).95 The vast majority of lines begins with the definite article (“The”) and an actor noun. The “woollypates” line features the same syntactic structure in both halves of the line, creating the line-internal parallelism. One effect of the mirroring internal frames is to create two parts of one image, a kind of verbal diptych. What is captured is a still life of one dimension of slavery in antebellum America. The tight syntactic equivalences enhance the contrasts in the two panes: plural “woollypates” versus one “overseer”; the former are named pejoratively96 while the “overseer” is called by his title; the slaves work while the “overseer” sits on a horse and “views them” working—the “them” (linguistically) objectifies the slaves, displacing the subjectivity that was bestowed upon “them” in the first half of the line.97 A lot can happen in the midst of Whitman’s parallelistic play.

The final example is meant as a reminder that synonymous parallelism may also serve reiterative ends. In this instance, the doubling exultation of the gains of scientific methodology and reasoning is not so differently shaped from the often iterative praise of the deity in so many of the psalms, e.g., “Praise ye the LORD. O give thanks unto the LORD” (Ps 106:1). Not infrequently this iteration at the heart of parallelism is ramified through what biblical scholars sometimes call “repetitive parallelism,” a form of parallelism that involves verbatim repetition(s) (e.g., “Wherefore I will yet plead with you, saith the LORD, and with your children’s children will I plead,” Jer 2:9; “The voice of the LORD shaketh the wilderness; the LORD shaketh the wilderness of Kadesh, Ps 29:8).98 Whitman is very fond of such internally parallel verbatim repetitions, e.g., “Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?,” LG “Clear and sweet is my soul…. and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul,” ; “Exactly the contents of one, and exactly the contents of two, and which is ahead?”, . Indeed, these kinds of verbatim repetitions are far more frequent in Leaves than in the Bible.

Antithesis

No matter the accuracy of the criticisms of the place of antithetical parallelism in Lowth’s reductive classification scheme, it nevertheless remains the case that the kinds of semantic play organized under this rubric originally by Lowth—“when two lines correspond with one another by an Opposition of terms and sentiments; when the second is contrasted with the first, sometimes in expressions, sometimes in sense only”99—do in fact appear in biblical poetry, especially in the didactic verse of the wisdom tradition (Proverbs, Job, Ben Sira). A typical example cited by Lowth is Prov 10:1: “A wise son maketh a glad father: but a foolish son is the heaviness of his mother.” He explains the opposing plays in this way: “Where every word hath its opposite: for the terms father and mother are, as the Logicians say, relatively opposite.”100 Such antithesis features prominently in the internally parallel lines of Martin Farquhar Tupper’s Proverbial Philosophy,101 a book directly inspired by the biblical wisdom tradition. Several lines may be offered to exemplify what a close emulation of the biblical form can look like:

“The alchemist laboureth in folly, but catcheth chance gleams of wisdom.” (p. 13)

“And the weak hath quailed in fear, while the firm hath been glad in his confidence.” (p. 17)

“The zephyr playing with an aspen leaf,—the earthquake that rendeth a continent;” (p. 20)

“Man liveth only in himself, but the Lord liveth in all things;” (p. 21)

“Poverty, with largeness of heat: or a full purse with a sordid spirit:” (p. 23)

Tupper is useful because he does not try to distance his own lines from his biblical model(s); indeed, he is even willing to develop biblical themes and ideas and feature biblical characters. Here his use of the KJB inspired two-part line and antithetical parallelism, with his own language slotted in, is plain to see. Whitman’s collaging from the Bible (and other sources) is often accompanied by a great deal more processing, and thus leaves fewer signs of the collaging itself (see Chapters Two and Three above). When he uses opposition, contrast, or antithesis in his parallelistic play, which is not as frequently as in Tupper or the Bible,102 it does not have the strong oppositional and weighted (to one side or the other) force of so many of the biblical binaries (e.g., wise/fool, rich/poor). Rather, Whitman’s optimism and inclusivity means that he is much more interested in using parallelism to overcome opposing dichotomies (“It is for the wicked just the same as the righteous,” LG), as epitomized in the line from the “Talbot Wilson” notebook discussed above, “I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves.”103 And there is the neighboring set of lines that gets included in Leaves but only belatedly massaged into a single, internally parallel line: “I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul” ()—the parallel frames (“I am the poet of”) hold together the “sharply contrasting” pair, “Body”//”Soul,” thus forging a parallelistic expression of the poet’s holistic anthropology.104

Whitman rarely crafts lines in which all corresponding parts are opposites (e.g., “And make short account of neuters and geldings, and favor men and women fully equipped,” LG). More commonly, Whitman’s antitheses are staged amidst synonymity (Lowth’s second variety of antithetical parallelism), and he is especially fond of playing on identical (or near identical) terms (see discussion of repetitive parallelism above):

“The rest did not see her, but she saw them and loved them” (LG)105

“I hear and behold God in every object, yet I understand God not in the least” (LG)

“I pass so poorly with paper and types…. I must pass with the contact of bodies and souls” (LG)

“It is not that you should be undecided, but that you should be decided” (LG)

“I love the rich running day, but I do not desert her in whom I lay so long” (LG)

“I stay awhile away O night, but I return to you again and love you” (LG)

“Happiness not in another place, but this place … not for another hour, but this hour” (LG

“The welcome ugly face of some beautiful soul … the handsome detested or despised face” (LG)

Most of these have the classic disjunctive (with “but” or “yet” heading the second clause) shaping of biblical antithesis, as well as at least one set of opposing terms (e.g., “did not see”// “saw”; “hear and behold”// “understand… not”; “be undecided”// “be decided”; “day”// night (unnamed); “stay away”// “return”; “ugly face”// “handsome… face”). For the sixth example, taken from “I wander all night,” compare this passage from Second Isaiah cited by Lowth in his initial discussion of antithetical parallelism: “In a little wrath I hid my face from thee for a moment; but with everlasting kindness will I have mercy on thee” (Isa 54:8).106 Prov 11:24, “There is that scattereth, and yet increaseth; and there is that withholdeth more than is meet, but it tendeth to poverty,” employs what Lowth describes as a “kind of double Antithesis”: “one between the two lines themselves; and likewise a subordinate opposition between the two parts of each.”107 Whitman’s line, “Happiness not in another place, but this place . . not for another hour, but this hour” (LG), is of a similar nature, though featuring synonymity instead of antinomy between the two subparts of the lines (see also “Great is wealth and great is poverty … great is expression and great is silence,” ). The “subordinate opposition between the two parts of each” of the original Hebrew lines in Prov 11:24 reflects line-internal parallelism within Hebrew line structure, which as noted earlier exists but is comparatively rare because typical biblical Hebrew poetic lines are generally too short, lacking the necessary amplitude for this kind of play. Whitman’s caesural divisions, as in this example, are another structural site where the poet stages parallelism with biblical antecedents. Some of these involve antithetical parallelism, e.g., “The vulgar and the refined … what you call sin and what you call goodness … to think how wide a difference” ().

Climactic Parallelism

Following Driver, Allen isolates a fourth pattern of parallelism (beside the Lowthian triumvirate) that he believes Whitman shares with the Bible. In climactic parallelism, according to Driver, “the first line is itself incomplete, and the second line takes up words from it and completes them.”108 He then cites three examples:

Give unto the LORD, O ye sons of the mighty,

Give unto the LORD glory and strength. (Ps 29:1)

The voice of the LORD shaketh the wilderness;

The LORD shaketh the wilderness of Kadesh. (Ps 29:8)

Till thy people pass over, O LORD,

Till the people pass over, which thou hast purchased. (Exod 15:16)

Lowth treats this “variety” of parallelism in his discussion of synonymous parallelism: “The parallelism is sometimes formed by the iteration of the former member, either in the whole or in part.”109 He cites as an example Ps 94:3:

“How long shall the wicked, O Jehovah,

“How long shall the wicked triumph!”

The three examples in Exod 15:16, Ps 29:1 and Ps 94:3, all with an intervening vocative in the first lines, represent a more restrictive version of the pattern, and are now more commonly referred to as “staircase parallelism.”110 In such parallelism (involving either two or three lines of verse), typically “a sentence is started, only to be interrupted… then resumed from the beginning again, without the intervening epithet [or subject NP], to be completed in the second or third line.”111 However, with or without the intervening element, staircase or climactic, the pattern is as Driver notices, “of rare occurrence” in the Bible.112

Allen repeats Driver’s definition and the first of his two examples from Psalm 29.113 However, nowhere in his initial discussion, nor in later iterations, does he specifically identify an example of climactic (or staircase) parallelism in Whitman, and none of his cited examples are especially redolent of the proposed biblical model(s). This is not unexpected. After all, Allen admits his difficulty in differentiating in Whitman between synonymous, synthetic, and climactic parallelism.114 In part this difficulty stems from the fact that Allen is working in translation, and is more beholden to Driver’s (among others) definition, rather than appreciating the underlying Hebraic pattern and how that pattern manifests itself in English translation. Whitman is enamored with anaphora, elliptical sentences and clauses, and runs of lines whose repetitions and parallelisms build on an underlying sentential structure or logic.115 All of these can appear to answer to Driver’s definition of climactic parallelism, but they are all very different from the attested biblical paradigm. The other part of Allen’s difficulty, quite simply, is that there are not many good examples of biblical climactic (or staircase) parallelism in Whitman’s poetry. Allen’s closest example is the first set of lines he cites from “I wander all night”:116

How solemn they look there, stretched and still;

How quiet they breathe, the little children in their cradles. (LG)

Variations on the three elements of staircase parallelism are present: 1) the repeated element (“How solemn they look there”// “How quiet they breathe”) are more synonymous than iterative (which is likely why Allen cites the lines, i.e., as exemplifying synonymous parallelism);117 2) there is an intervening element (“stretched and still”), though not the vocative or subject NP of biblical exemplars; and 3) the completing element (“the little children in their cradles”) supplies the referent for the fronted pronoun “they.” Closer interlinear matches are these two examples from “Suddenly out of its stale and dusty lair” and “Lilacs”:

They live in other young men, O kings,

They live in brothers, again ready to defy you: (LG)

Must I leave thee, lilac with heart-shaped leaves?

Must I leave thee there in the door-yard, blooming, returning with spring? (Sequel)

As with Allen’s examples there are variations here, too—most notably the shaping of the two lines from “Lilacs” as two questions, yet the biblical staircase structure in both is readily recognizable. Also from “Suddenly out of its stale and dusty lair” appears a possible line-internal (after combination) example of the staircase structure: “Out of its robes only this…. the red robes, lifted by the arm” (LG). The re-combined line (originally two in “Resurgemus”118) ultimately veers away from the biblical type, with “only this,” for example, serving as the intervening element (instead of a vocative or subject NP) and the syntax carrying over into the next line (viz. “One finger pointed high over the top, like the head of a snake appears”). There is also this tantalizing example from “The bodies of men and women engirth me”: “I will duly pass the day O my mother and duly return to you” ()—though only “duly” is repeated from the first half. A very abbreviated version of climactic parallelism (i.e., without an intervening element) occurs late in “I celebrate myself”: “I sleep…. I sleep long” (). Further examples are likely to be uncovered in a thorough search of Whitman’s expansive poetic corpus. Still, if staircase and climactic parallelism are rare in the Bible, they are even rarer in Whitman. The peculiarity of the form points to the Bible, but how consciously Whitman shaped his lines as a reflection of this form remains an open question.

Gapping.

One of the characteristic varieties of synonymous parallelism on which Lowth remarks specifically involves the gapping (or ellipsis) of an element: “There is frequently something wanting in the latter member, which must be repeated from the former to complete the sentence.”119 The gapping commonly features the “verb” or the “Nominative Case,” as Lowth observes, although verb gapping is prominent, since the verb is highly inflected and syntactically prominent in Semitic languages generally, with V(S)O word order prevailing in main clauses in the classical (or standard) phase of biblical Hebrew. These examples (from Lowth) feature verb gapping:

Isa 55:7

“Let-the-wicked forsake his-way;

“And-the-unrighteous man his-thoughts:” (Lowth)

“Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts” (KJB)

Isa 46:3

“Hearken unto-me, O-house of-Jacob;

“And-all the-remnant of-the-house of-Israel.” (Lowth)

“Hearken unto me, O house of Jacob, and all the remnant of the house of Israel” (KJB)

Prov 3:9

“Honour Jehovah with-thy-riches;

“And-with-the-first-fruits of-all thine-increase.” (Lowth)

“Honour the LORD with thy substance, and with the firstfruits of all thine increase” (KJB)

In each of these examples, the verb (forsake, hearken, honour) from the first line (or part of the verse) must be supplied in the second in order for the latter to be sensible—and in Prov 3:9 both verb and object must be supplied, i.e., “Honour Jehovah with-thy-riches”// “And-[honour Jehovah] with-the-first-fruits of-all thine-increase.” Whitman, too, likes gapping, especially the subject (English prefers SV(O) word order and lexically explicit subjects are mostly required given the minimal nature of inflectional morphology for verbs),120 as epitomized by the expanded opening line of the “Song of Myself,” “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” (LG), in which the subject, “I,” is gapped.121 Some examples from the many possibilities in the 1855 Leaves, include (elided elements in bold):

“They come to me days and nights and go from me again” (LG)

“Not words, not music or rhyme I want…. not custom or lecture, not even the best” (LG)

“You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me” (LG)

“And that all the men ever born are also my brothers…. and the women my sisters and lovers” (LG)

“And mine a word of the modern…. a word en masse” (LG, 28)

“Through me the afflatus surging and surging…. through me the current and index” (LG)

“Voices of the diseased and despairing, and of thieves and dwarfs” (LG)

“I do not know what it is except that it is grand, and that it is happiness” (LG)

“To think of today . . and the ages continued henceforward” (LG, 65)

“He whom I call answers me and takes the place of my lover” (LG)

Many similar examples could be cited. Tyndale and the KJB, by staying close to their underlying Hebrew source, bequeath to English style a tolerance for ellipsis generally. And the prominence of ellipsis within Whitman’s two-part lines is suggestive of this broad inheritance. Often as in biblical examples the gapping is compensated for—balanced—by an additional element in the second halves of lines, which can be manipulated to various (sometimes subtle) ends. For example, the gapping of the subject “You” in “You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me” (LG) allows Whitman to add “gently,” which gives the line a tenderness it would lack were the subject repeated and the second verb left unmodified (viz. “and you turned”). In “And that all the men ever born are also my brothers…. and the women my sisters and lovers” () the elision of “are also” after the suspension points makes space for the erotic charge he adds at line-end, “and lovers.”

Incipient Narrativity

The biblical poetic corpus, as previously noticed, is fundamentally nonnarrative in nature—poetry is used for all manner of things except telling tales.122 To be sure, individual poems incorporate narrative runs and sometimes even develop characters, but for the most part these forms are restricted in scale and put mainly to nonnarrative ends (e.g., Exodus 15, Proverbs 7). Of interest here is the “propelling force” for narrative in biblical poems on a still smaller scale, namely, “the incipiently narrative momentum” that can carry over from one line to the next in the play of parallelism.123 That is, one of the dynamics of biblical parallelism is the capacity to create a variety of small, often incremental, narrative effects (e.g., sequentiality, description, cause and effect) amidst the pulse of iteration. For example, sometimes the sequence of actions is quite explicit as in 2 Sam 22:17: “He sent from above, he took me; he drew me out of many waters.” Here Yahweh is imagined as sending forth his arm from on high and takes hold of the petitioner; and in the second half of the verse he draws the speaker to safety out of the “many waters”—or better the “mighty waters” of cosmic chaos. Exod 15:10 provides another good example: “Thou didst blow with thy wind, the sea covered them: they sank as lead in the mighty waters.” There is both movement in action (“sea covered them” > “they sank”) and a rendering of cause (“Thou didst blow with thy wind”) and effect (“they sank as lead in the mighty waters”). In Ps 106:19 (“They made a calf in Horeb, and worshipped the molten image”) is subtler. There is sequential development implied thematically in the two verbs—one has to make the calf before it can be worshiped.

Whitman’s internally parallel lines are filled with similar kinds of incremental narrative movement. Typical examples include:

“Loafe with me on the grass…. loose the stop from your throat” (LG)

“You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart,

And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet.” (LG)

“One hand rested on his rifle…. the other hand held firmly the wrist of the red girl” (LG)

“And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him” (LG)

“The sun falls on his crispy hair and moustache…. falls on the black of his polish’ d and perfect limbs” (LG)

“The carpenter dresses his plank…. the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp” (LG)

“They have cleared the beams away…. they tenderly lift me forth” (LG)

“I seize the descending man…. I raise him with resistless will” (LG)

“I open my scuttle at night and see the far-sprinkled systems” (LG)

“Washington stands inside the lines . . he stands on the entrenched hills amid a crowd of officers” (LG)

“The chief encircles their necks with his arm and kisses them on the cheek,

He kisses lightly the wet cheeks one after another…. he shakes hands and bids goodbye to the army.” (LG)

“The coats vests and caps thrown down . . the embrace of love and resistance,

The upperhold and underhold—the hair rumpled over and blinding the eyes;” (LG)

“Which the winds carry afar and re-sow, and the rains and the snows nourish” (LG)

“I love to look on the stars and stripes…. I hope the fifes will play Yankee Doodle” (LG)

“And clap the skull on top of the ribs, and clap a crown on top of the skull” (LG

Detailed commentary is not required to reveal the various kinds of incipient narrativity on display in these examples. Many involve sequences of related actions (e.g., “parted the shirt”// “plunged your tongue”; “went where he sat”// “led him”; “I seized the descending man”// “I raised him”). The two lines from the “wrestle of wrestlers” passage (LG) show that narrative momentum can even be projected without verbal predication. The succession of nominal phrases offers snapshots (stills) of the “two apprentice-boys” in the midst of their match. It is the succession itself, one nominal snapshot followed on by another, that creates the appearance of narrative momentum. In the content of the lines themselves Whitman is able to embellish descriptive details about the scene. For example, “the hair rumpled over and blinding the eyes” is a direct consequence of the “upperhold and underhold” (hence the long dash) and the “rumpled over” hair stands in as a metonym for the frenetic activity of wrestling. And yet what Whitman provides is a detail of the image of the wrestlers, their long hair askew and blinding them. In some of these instances, momentum can be created by using the same verb. In “And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet” () common knowledge of human anatomy (head at the top and feet at the bottom) allows the repeated verb “reached” in immediate adjacency and sequentially to give the impression of the lover’s ongoing (durative) reaching from head to feet. In “And clap the skull on top of the ribs, and clap a crown on top of the skull” () body knowledge is leveraged as well to create upward movement. The movement is provided by the noun phrases: “skull on top of ribs” > “crown on top of the skull.” As in the KJB, the narrativity in question need not be actional. Sometimes the link is cause and effect, as in the line from “Clear the way there Jonathan,” (“I love to look on the stars and stripes…. I hope the fifes will play Yankee Doodle,” ), where the appearance of the flag evokes a desire to hear “Yankee Doodle” played. At other times what results is more of an enriching of details in a scene, as in the line about where Washington “stands” (), or the image from the “marriage of the trapper” in which “one hand” of the trapper “rested on his rifle” and “the other hand held firmly the wrist of the red girl” ()—this last, famously, is Whitman’s ekphrastic rendering of an actual painting (The Trapper’s Bride by Alfred Jacob Miller, 1845).124

Envelope

Allen identifies the “envelope” as a figure of special import “because it shows how closely Whitman’s forms resemble those of biblical poetry” and “because it is one of the most numerous of the specific parallelistic devices that Whitman used.”125 Moulton is again Allen’s inspiration and source, and he uses the latter’s definition of the envelope: “A series of parallels enclosed between an identical (or equivalent) opening and close.”126 Here Allen slightly misunderstands Moulton. The envelope is itself not a “specific parallelistic” device. Rather, according to Moulton, it is a figure that frames sets of parallel lines. The “opening and close” may or may not be a figure of parallelism. Unfortunately, even Moulton is mistaken about the sets of lines contained by the envelope needing to be parallelistically related. They do not. All manner of lines, however they are grouped, are so enclosed. For example, most of the lines framed by the envelope in Song 4:1 (“Behold, thou art fair, my love”) and 7 (“Thou art all fair, my love”) are not parallelistically related. The envelope—also known as an inclusio, ring structure, or frame—is a traditional technique for bringing the “inherent interminability” of paratactic structures to a stopping point (however momentarily) via returning to the beginning.127 Like parallelism the envelope is a trope of repetition, viz. Moulton’s “an identical… opening and close.” The frames may well feature some version of parallelism (so the synonymous frame-words “city”// “gate” [a metonym for the former] in Ps 127:1, 5),128 but most often they are exact repetitions (or plays thereon). All structural levels are made use of, including even non-linguistic material (e.g., the couplets in Job 3:3, 10 frame an unrelenting series of triplets in the first section of Job’s famous curse of his birthday). Most common are envelopes made up of single lines (e.g., “Praise ye the LORD,” Ps 147:1, 20) or couplets (e.g., “O LORD our Lord, how excellent is thy name in all the earth!”, Ps 8:1, 9; “O give thanks unto the LORD; for he is good: because his mercy endureth for ever,” Ps 118:1, 29; “Rise up [v. 13: Arise], my love, my fair one, and come away,” Song 2:10, 13). The latter is made most visible for readers (like Whitman) in the KJB as it is coextensive with the verse divisions.

Allen also draws attention to what he calls the “incomplete envelope,” that is, “with either the introduction or the conclusion left off.”129 Of course, as Allen more judiciously observes later, “But of course an ‘incomplete envelope’ is not an envelope at all.”130 And there are no half envelopes (as such) in the Bible. Nonetheless, Allen does point to an interesting phenomenon in Whitman’s poetry. These misidentified “incomplete” envelopes usually consist of short(er) lines. A common means for concluding paratactic (and other kinds of) structures is to change up the pattern(s) governing the poem (or a section of a poem) at or near the end. Smith calls this “terminal modification.”131 Given the dominance of the long(er) line in the early editions of Leaves of Grass, an effective means for closing a poem or section is to shift to a shorter line. It is also not uncommon for beginnings to be set off in some fashion, though this can only be experienced retrospectively by readers. Short lines introducing runs of long(er) lines in Whitman is both comprehensible and well evidenced. W. D. Snodgrass notes a common stanza form in Whitman’s poetry that consists of an opening short line, progressively longer lines in the middle, and then short lines again at the close—the latter “form, with the opening lines, a syntactic and/or rhythmic envelope.”132 Here is a not untypical example from “I celebrate myself”:

Trippers and askers surround me,

People I meet…. . the effect upon me of my early life…. of the ward and city I live in…. of the nation,

The latest news…. discoveries, inventions, societies…. authors old and new,

My dinner, dress, associates, looks, business, compliments, dues,

The real or fancied indifference of some man or woman I love,

The sickness of one of my folks—or of myself…. or ill-doing…. or loss or lack of money…. or depressions or exaltations,

They come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself. (LG)

This manipulation of line length also appears commonly in biblical poetry, but the prose renderings of the KJB blur such distinctions, especially given the markedly narrower range of Hebrew line-length variation.

Conditionals

Conditional sentences (or clauses) have nothing to do with parallelism. However, because of the overwhelming binarism of the biblical poetic tradition—lines come grouped mostly as couplets—the protasis and apodosis of conditionals are often distributed to align with the couplet’s component lines, and thus typically rendered in the KJB as a single, two-part verse division (e.g., “If I regard iniquity in my heart, the Lord will not hear me,” Ps 66:18). Such two-part lines filled with conditionals abound in Leaves:

“If I worship any particular thing it shall be some of the spread of my body” (LG)

“If they are not yours as much as mine they are nothing or next to nothing” (LG)

“If you tire, give me both burdens, and rest the chuff of your hand on my hip” (LG)

“If you would understand me go to the heights or water- shore” (LG)

“If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles” (LG)

“If you remember your foolish and outlawed deeds, do you think I cannot remember my foolish and outlawed deeds?” (LG)

“If you were not breathing and walking here where would they all be?” (LG)

“If maggots and rats ended us, then suspicion and treachery and death” (LG)

“If life and the soul are sacred the human body is sacred” (LG)

“If you blind your eyes with tears you will not see the President’s marshal” (LG)

“If you groan such groans you might balk the government cannon” (LG)

“If there be equilibrium or volition there is truth . . . if there be things at all upon the earth there is truth” (LG)

Several of the examples collected here have apodoses which contain questions (e.g., “…where would they all be?” LG). There are many biblical models for these (e.g., “If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?”, Ps 11:3; “If thou, LORD, shouldest mark iniquities, O Lord, who shall stand?”, Ps 130:3; “If thou hast nothing to pay, why should he take away thy bed from under thee?,” Prov 33:27). One example contains a compound apodosis (“If you tire, give me both burdens, and rest the chuff of your hand on my hip,” ). Compound protases and apodoses are common in biblical poetic conditionals (e.g., “If I sin, then thou markest me, and thou wilt not acquit me from mine iniquity,” Job 10:14; “If iniquity be in thine hand, put it far away, and let not wickedness dwell in thy tabernacles,” Job 11:14; “If thou hast run with the footmen, and they have wearied thee, then how canst thou contend with horses?”, Jer 12:5). The last example from Whitman () contains a double conditional, also found in the Bible (e.g., “If I be wicked, woe unto me; and if I be righteous, yet will I not lift up my head. I am full of confusion,” Job 10:15; “If I ascend up into heaven, thou art there: if I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there,” Ps 139:8; “If thou be wise, thou shalt be wise for thyself: but if thou scornest, thou alone shalt bear it,” Prov 9:12). Job 31 repeats the conditional protasis fifteen times, which is suggestive of Whitman’s several runs of conditionals in the 1855 Leaves ( –).

Duple Rhythm

Whitman’s two-part lines as they isolate (and iterate) syntactic units through parallelism give his verse a persistent duple rhythm that pervades the whole of the 1855 Leaves. Other line types ensure that this double pulse never seems too insistent or monotonous. Yet its feel and presence is periodically magnified when a number of these two-part lines are grouped together, as in this passage from “I celebrate myself”:

You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart,

And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet. (LG

All goes onward and outward…. and nothing collapses,… (LG,)

Or this set from “To think of time”:

How beautiful and perfect are the animals! How perfect is my soul!

How perfect the earth, and the minutest thing upon it!

What is called good is perfect, and what is called sin is just as perfect;

The vegetables and minerals are all perfect . . and the imponderable fluids are perfect;

Slowly and surely they have passed on to this, and slowly and surely they will yet pass on. (LG)

This duple pulse mostly counterpoints the regular march of lineal (end-stopped) wholes that is the rhythmic backbone of Whitman’s poetry—“internal parallelism… is one of the means Whitman employs to prevent his use of the synonymous form from becoming monotonous.”133 Occasionally, Whitman’s grouping of syntactically parallel lines into couplets momentarily reinforces the doubled movement within so many of his lines (e.g., “I am the poet of the body,/ And I am the poet of the soul,” LG,).134

The role syntax plays in shaping these rhythmic effects merits underscoring, given the emphasis on syntax in more recent studies of biblical parallelism, as well as in Warren’s own work on parallelism in Whitman.135 For Warren, in fact, Whitman folds himself within the tradition of “the impassioned voices” of Hebrew prophecy specifically “by using the rhythm-producing syntax of the English Bible.”136 Like Allen, Warren is chiefly preoccupied with how parallelism structures the relationship between lines in Whitman’s poetry. However, the principal elements of this “rhythm-producing syntax of the English Bible”—the coordinating structure and the parallel alignment of clauses137—are themselves primordially made manifest within the internally parallelistic verse divisions of the poetic books of the English Bible. While Whitman does also martial this same “rhythm-producing syntax” as a line grouping strategy, as Warren shows, the kernel of what is taken from the “English” Bible by Whitman is most directly on display in the poet’s many internally parallel lines with their distinctive duple pulse.138

One of Allen’s main ambitions in “Biblical Analogies” is to determine “why the rhythms of Whitman have suggested those of the Bible.”139 In this instance, the doubling rhythm that courses through Whitman’s many two-part lines appears to be a distinct echo of the bilateral pulse of biblical parallelism’s “music of matching,” which as Hollander well describes, carried over into English through translation—“One river’s water is heard on another’s shore; so did this Hebrew verse form carry across into English.”140 Hollander’s mimicking exposition is as illuminating of Whitman as it is of the English Bible, for in Hollander we see what Whitman must have been doing as well.

Three-Part Lines

Though biblical verse is dominantly distichic, the triplet is not uncommon, often appearing at structurally or thematically pertinent places—though triplets occasionally form the basic grouping scheme in sections of a poem and even in whole poems (e.g., Ps 93; Job 3:3–10).141 In the prose translation of the KJB, these triplets are shaped mostly into verse divisions comprised of three distinct parts (Hollander: “One half-line makes an assertion; the other part paraphrases it; sometimes a third part will vary it”).142 For example, consider Job 3:5, first in the lineated translation of the ASV and then in the prose rendering of the KJB:

Let darkness and the shadow of death claim it for their own;

Let a cloud dwell upon it;

Let all that maketh black the day terrify it. (ASV)

Let darkness and the shadow of death stain it; let a cloud dwell upon it; let the blackness of the day terrify it. (KJB)

The three parts of the KJB’s prose are marked by the two semicolons and correspond to the component lines of the underlying triplet, which the ASV’s lineation makes visible (the language of the KJB and the ASV are otherwise quite close). Sometimes the underlying triplet is not apparent in translation, either because of English syntax or because the translators themselves have misunderstood the underlying line division of the Hebrew. In Ps 128:5 (“The LORD shall bless thee out of Zion: and thou shalt see the good of Jerusalem all the days of thy life”) it is only the elongated second half of the verse (fourteen words as opposed to eight in the first half) that betrays the presence of a third poetic line in the underlying Hebrew (= “all the days of thy life”; ASV also misconstrues as a couplet). Whitman’s verse also contains many three-part, internally parallel lines:

“A few light kisses…. a few embraces…. a reaching around of arms” (LG, 13)

“As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side all night and close on the peep of the day” (LG)