5. “The Divine Style”: An American Prose Style Poeticized

©2024 F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0357.06

Also no ornaments… perfect transparent clearness sanity and health

are wanted—that is the divine style—O if it can be attained—

— Walt Whitman, “In future Leaves of Grass”

In an incisive study, Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible,1 Robert Alter argues for the existence of an “American prose style” among major American novelists from the nineteenth through the twenty-first centuries (including Melville, Bellow, Faulkner, Hemingway, McCarthy, Robinson) that descends from the King James Bible. For Alter, style has aesthetic values and intimates a vision of reality yet also has material, linguistic manifestations. In the style that descends from the KJB, these latter include parallelism, diction and phrasing, syntactic frames, distinctive rhythms or cadences, as well as an assorted use of biblical themes, characters, imagery, and imitations. Whitman wrote lots of prose over the course of his lifetime, including some fiction, but it was as the poet of Leaves of Grass that he obtained real achievement as a writer. Understandably, then, Whitman does not figure in Alter’s study. And yet there are ways, I want to suggest, that the style of Whitman’s poetry (especially in the early editions of Leaves) equally descends from the prose of the KJB and shares a broad kinship with the American prose style charted by Alter, albeit in a nonnarrative mode and with a decidedly political bent—the English prose style of the Bible poeticized and politicized. For my larger thesis, recognizing the strong stylistic affinities Whitman’s poetry shares with aspects of many of the novels studied by Alter offers another means by which to tease out further dimensions of Whitman’s debt to the KJB. And since a number of this style’s leading material characteristics (e.g., parallelism) are touched on in previous chapters, viewing Whitman heuristically through Alter’s lens of an American prose style provides a convenient way to reprise some of the leading features of my own argument. It also has the added benefit of confirming many of Alter’s insights, not least because of the refraction the style is given in a nonnarrative mode. Lastly, the prominence of the style’s prosaic bent is important for understanding both the development of Whitman’s style and why he succeeds with it. Whitman mostly wrote and read prose in the run-up to the 1855 Leaves. It is only once he fashions a line capacious enough to accommodate his own distinctly prosaic talents and tendencies and deploys it (somewhat perversely) towards nonnarrative ends that Whitman achieves success—Chapter 19 in Whitman’s novella, “Jack Engle” (from 1852),2 offers a fabulous prosaic foretaste of this style to come. The biblical prose style poeticized was necessary for Whitman to become the poet of Leaves of Grass. William Tyndale (d. 1536) features prominently in my discussion as it is his commitment to plain and simple diction, clarity and accuracy, and staying close to the Hebrew and Greek originals while ultimately making sense in English that sets the norm for all succeeding English translations of the Bible, including the KJB. Whitman’s self-denominated “divine style” is a rightful heir to the biblical English prose style divinely inaugurated by Tyndale.

“Plate-glassy style”

Whitman’s determination to “make no mention or allusion” to classic sources like the Bible in his poetry, except “as they relate to the new, present things,” was in service to the aesthetic sensibility he was evolving in the 1850s that prized above all “a perfectly transparent plate-glassy style,” as he puts it in the “Rules for Composition”:3

A perfectly transparent, plate-glassy style, artless, with no ornaments, or attempts at ornaments, for their own sake,—^they only coming in where answering looking well when like the beauties of the person or character, by nature and intuition, and never lugged in [illeg.] in by the colla to show off, which founders nullifies the best of them, no matter under when and where, or under of the most favorable cases.

….

Too much attempt at ornament is the blur upon nearly all literary styles.

Clearness, simplicity, no twistified or foggy sentences, at all—the most translucid clearness without variation.—4

That is, quotations of or allusion to the Bible—and “Mention not God at all” (i.e., the God of the Bible, with a capital “G”)—are among the “ornaments” that Whitman judges to be a “blur upon nearly all literary styles.” Also jettisoned are the many “thee”s and “thy”s and “lo”s that mark the biblical text (and its imitators, such as Martin Farquhar Tupper). And Whitman writes in a register he means to be broadly accessible—literally, democratic—and even when he is intentionally obscure (“Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then…. I contradict myself,” LG) or his larger structures are at their most ambling and undulating (“the free growth of metrical laws and bud from them as unerringly and loosely as lilacs or roses on a bush,” ), his language at the lineal and sub-lineal levels remains mostly simple and clear—“I lean and loafe at my ease…. observing a spear of summer grass” (). “The art of art, the glory of expression and the sunshine of the light of letters,” Whitman writes in the 1855 Preface, “is simplicity” (). His lines, though often long, are unfailingly end-stopped and (mostly) contain “no twistified or foggy sentences.” However much this aspiration toward “clearness” and “simplicity” of style suited Whitman’s temperament as a writer, he also worked hard to achieve it, as his many doings and redoings in his notebooks and poetry manuscripts amply attest. He encountered similar appreciations in the reading he did from 1845 to 1852, especially from 1848 on as his reading turned more exclusively to focus on poetry and literature.5 For example, in a review essay by A. De Vere in the Edinburgh Review from 1849, clipped and annotated by Whitman, the author’s admiration for plain style is echoed by a marginal note from Whitman: “The substance is always wanted perfect—after that attend to costumes—but mind, attend to costumes.”6 Perhaps one of Whitman’s earliest bits of advice to himself about style comes in an annotation to a clipping on Ossian from an article by M. Fuller from 1846.7 After an admiring gloss on Ossian (“Ossian must not be despised”), Whitman writes more critically: “How misty, how windy, how full of diffused, only half-meaning words! —How curious a study!—(Don’t fall into the Ossianic, by any chance.).” These comments are followed immediately by Whitman’s query about the Ossian poems’ (possible) relationship to “Biblical poetry” and his exaltation of the greatness and originality of the latter (as discussed in Chapter One). The connection between the style of the “Hebrew poems” and the style of the Ossian poems is at best implicit or subconscious, viz. the style of Ossian provoking in Whitman, first, an exhortation about his own manner of writing and, second, a reflection on the “tremendous figures and ideas of the Hebrew Poems.” And yet the availability of this stylistic plainness in English is due in large part to the KJB and to the genius of William Tyndale.

Alter identifies two “great sources of stylistic counterpoint” in English, which derive respectively “from the Greco-Latin and the Anglo-Saxon components of the language.”8 The former, historically, is erudite, ornate, featuring polysyllabic words and subordinating syntax; while the latter, as Alter well describes, is “phonetically compact, often monosyllabic, broadly associated with everyday speech, and usually concrete.”9 It is this latter, plain style that “by and large” pervades the KJB. And though Alter is not wrong to emphasize that “the counterpointing” of the two styles has been a possibility in “English prose since the seventeenth century”10—in no small part because of the wild popularity the KJB eventually obtains (especially in the nineteenth century)—in fact it is only a possibility because of Tyndale.11 The KJB, originally conceived as “a new translation of the Bible,”12 evolved in the end as a revision of the preceding English translations of the sixteenth century, with a 1602 edition of the Bishops’ Bible (first published in 1568) serving as the base text for King James’ translators.13 Among the rules Richard Bancroft set as guidelines for the translators is the fourteenth, listing the main versions to be consulted besides the Bishops’ Bible: “These translations to be used, when they agree better with the text than the Bishops’ Bible, viz.: Tyndale’s, Matthew’s, Coverdale’s, Whitchurch’s [Great], Geneva.”14 Tyndale’s inclusion in the list is both tragically ironic, he was martyred because of his translations, and strictly unnecessary, since his translations formed the foundation for all of the others, including the Bishops’ Bible—and (as it turned out) the KJB. With regard to the latter the statistical data alone are telling: in the New Testament, 83% of the language is Tyndale’s; and in the Old Testament where he translated (Pentateuch, Former Prophets, Jonah, and other selected passages used in the daily liturgy) Tyndale is responsible for 76% of the language used by the KJB translators.15 The plain style that Alter associates with the KJB is largely the creation of Tyndale.

Tyndale, the first to translate from the original Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic of the Bible into English,16 followed Luther’s lead in translating the New Testament first. A first complete edition of the latter in English appeared in 1526.17 Upon turning his attention to the Old Testament, Tyndale discovered a linguistic congeniality between Hebrew and English:

And the properties of the Hebrue tonge agreeth a thousande tymes moare with the englysh then with the Latyn. The maner of speaking is both one, so that in a thousande places thou neadest not but to translat it in to the englysh worde for worde when thou must seke a compase in the latyne & yet shalt haue moch worke to translate it welfauerdly, so that it haue the same grace & swetnesse sence and pure understandinge with it in the latyne as it hath in the Hebrue. A thousande partes better maye it be translated into the english then into the latyne.18

These observations come from Tyndale’s polemical treatise, Observations of a Christian Man (1528), in which, among other matters, Tyndale is making a case for translating the Bible into English.19 Tyndale here is calling attention to the fact that the syntax of both English and biblical Hebrew mostly unwinds additively in what are known as branching patterns.20 In such patterns, as E. B. Voigt describes (for English), “modification follows in close proximity to what is modified” so that listeners are not overly taxed in remembering or anticipating referents.21 This branching pattern in part compensates for the erosion of the case system on nominals that happened in earlier stages of both languages. Without case to indicate precise grammatical function, English and biblical Hebrew make use of function words, word order, and proximity to help map syntactic relations. These are “the properties of the Hebrue tonge” that “agreeth a thousande tymes moare with the englysh then with the Latyn,” a language whose rich case system is still intact (like ancient Greek), and thus is morphologically wired to tolerate more play in word order (“thou must seke a compase in the latyne”) with less dependency on proximity and lexical staging. The chief upshot for Tyndale stylistically is his “willingness to be as literal as is reasonably possible within the bounds of producing a readable English version”22—as he says, “thou neadest not but to translat it in to the englysh worde for worde.”23 This determination to stay close to the original Hebrew of his biblical source had important implications for Tyndale’s plain style, including its privileging of finite verbs, its rhythmicity, and its proclivity for variation in word orders, parataxis, short sentences, and the use of verbal and nominal redundancies (and other formulaic repetitions) and primary naming (as opposed to secondary referencing).24 D. Daniell offers this assessment of the importance of Tyndale’s discovery:

Tyndale, and Tyndale alone… was engaged in a full-scale work of translating Hebrew into English. His discovery of the happy linguistic marriage of the two languages, though not quite as important as Newton’s discovery of the principle of universal gravitation, was still of high significance for the history of western Christian theology, language and literature—a high claim, but not difficult to support, though the work on it has largely still to be done….25

Beyond the strong imprint that Hebrew narrative style in particular left on Tyndale, Tyndale’s writing is marked above all by clarity, directness, and simplicity and a diction that famously every plowboy could understand—“If God spared him life, ere many years he would cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture than he did.”26 This set the pattern for all English translations of the Bible to follow, including the KJB.27 Therefore, not only is there a lot of Tyndale literally in the KJB but the latter’s prose style more generally is also directly indebted to Tyndale. And thus while it is undeniable that from the seventeenth century forward the KJB “introduced a new model of stylistic power to the [English] language,” as Alter maintains,28 that style originated some eighty years earlier with Tyndale. Many aspects of Whitman’s plain style, as I show below, may be directly associated with stylistic elements of the KJB (as with Lincoln, Melville, and the other novelists Alter studies), making Whitman, ultimately, a rightful heir of the KJB and the KJB’s foremost stylist, William Tyndale.

(Some) Biblical Elements of Whitman’s Plain Style

In what follows I isolate a number of the leading material elements of Whitman’s style that may be tied to the KJB. There is more to Whitman’s style than a tallying of its main features. Still, these features (singularly and in aggregate) provide a concrete means of connecting this style to the prose of the KJB. In advance of his own analysis of the style of a given author (and novel under review), Alter usually establishes that author’s connection to the Bible in some way (e.g., through Faulkner’s title for Absalom, Absalom!, a modification of phrasing in 2 Sam 19:4; in Hemingway’s biblical epigraph to The Sun Also Rises, Eccl 1:4–7). Many of the reviews of the early editions of Leaves, as well as Whitman’s own (often belated) commentary (e.g., “The Great Construction of the New Bible,” NUPM I, 353), make clear the biblical impulse of Leaves. And the preceding chapters of this study amply attest to Whitman’s use and knowledge of the Bible more generally, and at some points even anticipate the principal topic of discussion in this chapter.

None of the authors studied by Alter fully replicates Tyndale’s (or his heirs’) plain prose style. Rather, they deploy elements of this style selectively and develop them to their own ends. Faulkner is emblematic. His spectacularly “flamboyant” style is often the antithesis of the simplicity and plainness of the English Bible’s prose. Nevertheless, Alter points to a “thematically fraught” lexicon of biblical terms in Absalom, Absalom! that clarifies “how the writing in this novel is pervasively biblical even as a conspicuously unbiblical syntax and vocabulary are constantly flaunted.”29 Whitman is not different. In particular, his fondness of polysyllabic and foreign words and the expanded space of his poetic line often run counter to Tyndale and his revisers’ use of Saxon monosyllabics and a spare, short prose line. And Whitman’s forte is not in narrative.30 Yet there remain multiple elements of the style Whitman fashions for his poetry in Leaves that he clearly found in the KJB. I review the most prominent of these here.

The Difference of Poetry

That Whitman is writing poetry in Leaves turns out to be consequential for what he devolves from the prose of the Bible and how. Parallelism is paradigmatic. Parallelism for Alter is a characteristic element of the prose style that descends from the KJB and features prominently throughout his study.31 And yet because Alter’s focus is on the novel, parallelism is never a pervasive stylistic feature of any of the authors he studies. Prose by its nature (viz. language organized in sentences) cannot exploit parallelism’s repetitive play in anything approaching the regularity that verse (viz. language periodically interrupted) permits; and when it does appear it is more easily sublimated by narrative’s linearity, logic, and argument.32 That is, the very medium of Whitman’s writing—poetry—means that this facet of the biblically-based prose style that Alter seeks to reveal stands out as it cannot in prose. Alter rightly emphasizes the prosaic nature of the KJB as a translation and specifically its lack of “typographic indication of lines of verse for the poetry” and how this “would have encouraged Melville,” for example, “as an English reader to see the biblical poetry as a loose form of elevated discourse straddling poetry and prose and hence eminently suited to his own purposes.”33 Much the same may be said of Whitman (see Chapter Three), except Whitman in Leaves is (mostly) not narrating a story and accommodates the underlying structure of the biblical Hebrew parallelistic couplet to his long line such that the former’s shape and rhythm are not “masked” (as in Melville’s prose) but accentuated (see Chapter Four). Tyndale’s decision to stay as close as possible to the underlying Hebrew in his translations meant that the parallelistic structures pervading biblical literature (whether poetry or prose) were preserved and ready for Whitman (and other writers) to find and reanimate.

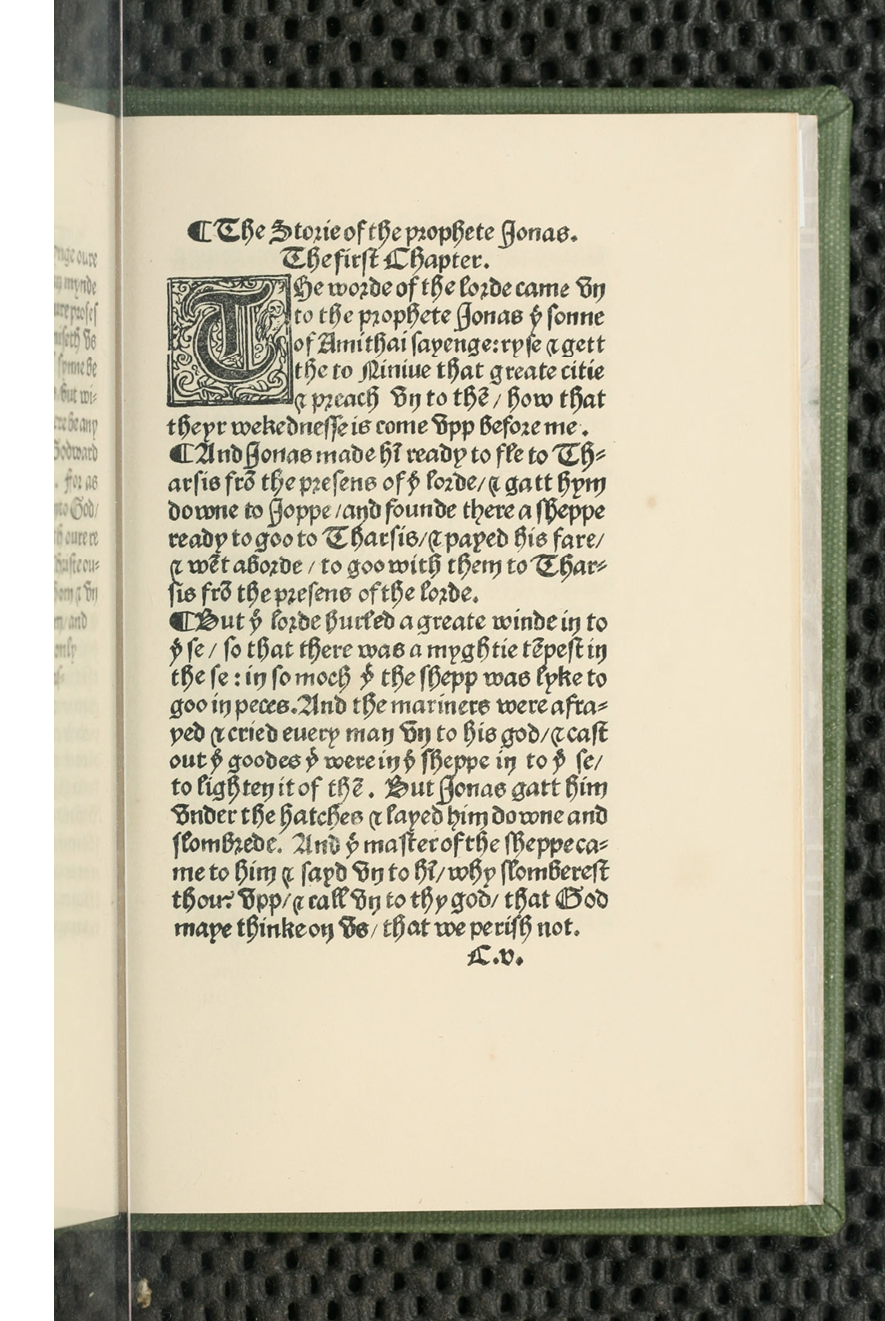

Whitman’s line offers another example of the consequence of poetry for what Whitman inherits from the Bible. The line is the basic scaffolding for Whitman’s writing, and its shapes and lengths are part of what distinguishes his style. As argued in Chapter Three, the verse divisions of the KJB likely played a role in shaping Whitman’s ideas about his line. Here what is most consequential is formatting, the interrupting force of the KJB’s verse divisions and accompanying indentations which Whitman transforms into lineal units—and indeed the later Whitman even reifies this move by supplying his own poem, section, and stanza numbers (beginning in the 1860 Leaves) in imitation of the Bible. The novelists in Alter’s study, in contrast, return (unconsciously no doubt) to the plain page layout of Tyndale (Fig. 48), and thus must sublimate the persistent interruptions caused to the flow of sentences in the Bible by the verse divisions (and their enumeration). Hemingway’s choice of formatting for the biblical epigraph to The Sun Also Rises brings this fact into relief. In his quotation of Eccl 1:4–7, he opts for a running format, eschewing the indentations and new lines for new verses, and uses ellipses instead of the verse numbers of the KJB, e.g., “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh; but the earth abideth forever… The sun also ariseth.”34 The ellipses accommodate to the running format of Hemingway’s own prose, while leaving a trace of the segmented style of the biblical source.

Fig. 48: A facsimile edition of William Tyndale’s translation of the Book of Jonah (1863 [1531]) showing the plain page layout Tyndale used (in the then familiar “Black letter” typeface). Public domain.

Daniell emphasizes the malleability of the prose that Tyndale fashions for his Bible translations, a style that remains distinct and identifiable and yet capable of rendering a rich array of different kinds of discourses (e.g., narratives of various sorts, ritual and legal legislation, historiography, Pauline letters, some Hebrew poetry).35 Prose in the KJB is not just for telling stories. Alter is alert to the nonnarrative dimensions of this prose as they impact the writers he surveys (e.g., semantic parallelism in Moby-Dick). But these dimensions, when present, are mostly intermittent in these writers and their novels. In Leaves the nonnarrative is primary. Like Melville and the others, Whitman absorbs the prose language of the KJB (narrative and otherwise), but he deploys it quite differently, towards nonnarrative (often explicitly lyrical) ends. This is a disposition his poetry shares with large chunks of the (English) Bible’s prose, much of which, of course, is a translation of biblical Hebrew verse, itself a decidedly nonnarrative poetic tradition—“the Hebrew writers used verse for celebratory song, dirge, oracle, oratory, prophecy, reflective and didactic argument, liturgy, and often as a heightening or summarizing inset in the prose narratives—but only marginally or minimally to tell a tale.”36 The “Hebraic chant” (like that “of the ancient prophet poets”) that early readers of Leaves heard in Whitman was mediated to English speakers through a biblical prose disposed toward nonnarrative ends.37 Non-narrativity itself, then, is an important aspect of (some of) the English prose of the Bible and gains sustained refraction in Whitman’s verse in a way generally not met with in most novelistic fiction. Whitman’s own fiction is illustrative. In Chapter 19 of his novella “Jack Engle,” Whitman momentarily suspends the narrative as his young protagonist wanders among the gravestones of the old Trinity Church cemetery. Z. Turpin rightly notes how the content of the chapter “strikes similar notes” to and perhaps “hints at the geographical origins” of the various meditations on mortality in Leaves.38 Yet it is also the sentential style of this meditation, especially the expanded amplitude of so many of its sentences, pitched at an angle of non-narrativity that stands out from the rest of the novella. The opening sentence of the chapter announces the stylistic shift immediately:

In the earliest chapter of my life, speaking of Wigglesworth, I alluded to the melancholy spectacle of old age, down at the heel, which we so often see in New York—the aged remnants of former respectability and vigor—the seedy clothes, the forlorn and half-starved aspect, the lonesome mode of life, when wealth and kindred had alike decayed or deserted.39

The sentence stretches out to sixty-one words, the last half of which consists of appositional elaborations frequently pocked by alliterative phrasing (e.g., “the aged remnant of former respectability,” “the lonesome mode of life,” “decayed or deserted”). In another example, Jack Engle, “in a musing vein,” comes across a family plot of “natives of New York” and queries the human instinct to come home again to die:

Human souls are as the dove, which went forth from the ark, and wandered far, and would repose herself at last on no spot save that whence she started. To what purpose has nature given men this instinct to die where they were born? Exists there some subtle sympathy between the thousand mental and physical essences which make up a human being, and the sources where from they are derived?40

The brief meditation begins with an allusion to the dove episode from the flood narrative (Gen 8:8-12), albeit read slightly against the grain—the dove returns (initially, vv. 8–9) because the earth is still covered with water and the dove “found no rest for the sole of her foot.” Rhetorical questions follow. It appears to be “musing” outside of narrative that unshackles Whitman’s prose in ways that anticipate the nonnarrative poetry of Leaves. Many similar moments occur in Leaves. For example, compare the latter to this passage from “I celebrate myself”:

I wish I could translate the hints about the dead young men and women,

And the hints about old men and mothers, and the offspring taken soon out of their laps.

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere;

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceased the moment life appeared. (LG–).

Whitman’s allusions to and quotations, echoes, and citations of the nonnarrative portions of the Bible show that the poet knows this prose (see Chapter Two). What I am emphasizing here is the non-narrativity itself—Whitman is chiefly a lyricist in the early editions of Leaves of Grass. This is perhaps a subtle point but one worth making. There are narrative runs in Leaves, but they are inevitably constrained and put to nonnarrative ends. What is different in Whitman (vis-a-vis the narrative artists of interest to Alter) is that all of the KJB’s prose deployed for something other than telling stories—including the dialogue that dominates biblical stories—finds a ready outlet in the poet’s long-line, prose-infused, nonnarrative verse.

Emblematic of this non-narrativity is Whitman’s preference for the present tense. M. Doty, commenting specifically on “I celebrate myself,” perceptively observes that Whitman’s “poem operates in the now”—the opening three lines “establish the poem in the present tense.”41 Doty elaborates:

Along the way we’ll hear short narratives of remembered experience, family stories, even the tale of a sea battle the speaker’s heard about. But the body of the poem seems spoken in the moment of its composition, which lends the voice a living edge, and helps to account for the poem’s aura of timelessness.42

This is the Psalms, Job, Isaiah, Song of Songs, Lamentations, and the great festival songs (e.g., Exodus 15, Judges 5, Deuteronomy 32) and the language of the present tense that Tyndale, Myles Coverdale, and the Geneva Bible and KJB translators fashioned to give expression in English to this body of decidedly nonnarrative verse. Crucially, verb morphology in biblical Hebrew does not grammaticalize tense specifically, and thus it is the necessity of rendering Hebrew into the tense-based forms of English that results in the pronounced present-tense bias of Englished versions of biblical poetry, squarely an achievement of the sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century translators.

Directly affiliated with a proclivity for non-narrativity and the present tense is what M. Miller describes as Whitman’s “inclusive, declarative, broadly figured first person voice.”43 I take note of this stylistic trait here, in part, because it stands in contrast with the third person narration (mostly in past tense) that is a central preoccupation of Alter in Pen of Iron, and, in part, because Whitman’s discovery of his voice—his “barbaric yawp”—is so dramatically on display in the early “Poem incarnating the mind”44 notebook (especially in a section appropriately titled “The Poet”45) in the poet’s revisions from third- to first-person address:

All this he I drinks swallowed in his my soul, and it becomes his mine, and he I likes it well.

He is I am the man; [illeg.] he I suffered, he I was there:

The third person is literally canceled—struck through—and merely by a change of the pronoun, as Miller observes,46 the first-person voice of Whitman’s poetic speaker enters history. With the change, Whitman subtly but crucially shifts from writing poetry about the ideal (“greatest”) poet of (his and Emerson’s)47 theory to becoming that poet—“I am the Poet.”48

As ever with Whitman, what motivated this change is unknown.49 C. K. Williams provocatively evokes Archilochos as a means of regrounding Whitman’s all encompassing “I” in the tradition of “the lyric ‘I.’”50 I am sympathetic to the direction of Williams’ gesture. But contrary to Williams, it does not all begin with Archilochos. The lyric itself is a culturally diverse phenomenon, with traditions that antedate that of ancient Greece, including those of the Hebrew Bible.51 Whitman himself was not only well-read in the Bible but he thought “it often transcends the masterpieces of Hellas.”52 Moreover, poetry and direct discourse in the Bible share the same basic pronominal and verbal profile,53 and thus first-person address abounds in biblical poems, including such capacious voices as the “I” of the haggeber—“the man”—in Lamentations 3. And it seems that Whitman himself was very much aware of the commodious nature of the Bible’s own poetic speakers (including lyricists): “The finest blending of individuality with universality (in my opinion nothing out of the galaxies of the ‘Iliad,’ or Shakspere’s heroes, or from the Tennysonian ‘Idyls,’ so lofty, devoted and starlike,) typified in the songs of those old Asiatic lands.”54 In fact, the breadth and diversity of those who vocalize the “poetic I” in biblical verse (priest, prophet, singer, ordinary women and men, God), read holistically, anticipates and no doubt in part funds Whitman’s own omnivorous “poetic I.”

Parallelism, Whitman’s line, and the non-narrativity (often in first person, present tense) of most of the verse in the early Leaves illustrate to varying degrees the important difference of poetry in how and what is inherited from the prose tradition of the KJB and how that inheritance may manifest itself. What Whitman helps to illuminate, in light of Alter’s identification of an American prose style devolved from the KJB, is the possibilities for that style beyond narrative fiction.

Parataxis

Parataxis, which Alter characterizes generally as “the form of syntax that strings together parallel units joined by the connective ‘and,’”55 is another hallmark of the biblical prose style that Alter traces in American fiction. The parallel units strung together in this manner tend to be “relatively short sentences” made up mostly of “phonetically compact,” Anglo-Saxon monosyllables.56 This is Tyndale’s plain style: “a strong direct prose line, with Saxon vocabulary in a basic Saxon subject-verb-object syntax”—“Saxon words are short. So too are Saxon sentences, in which short phrases are joined by ‘and.’”57 It is a style that Tyndale crafted for English under the direct impress of biblical Hebrew. As G. Hammond explains: “In Hebrew biblical narrative there is little variation in the way sentence is tied to sentence and clause to clause. Ubiquitously—and by that I mean well over ninety percent of the time—the connecting link is the particle waw.”58 Tyndale, who never wanted “to run too far” from the underlying Hebrew, mostly translated the main (and pervasive) Hebrew coordinating conjunction (wĕ-) with the simple English “and”—the KJB ramifies this practice.59 And part of the affinity Tyndale saw between English and Hebrew was how well his short native Saxon sentences matched the typically compact Hebrew prose sentences, “thou neadest not but to translat it in to the englysh worde for worde” (with but the slightest alteration of Hebrew’s classic verb-(subject)-object word order).60 Verbs are “the central verbal power” in both languages.61

The imprint of this paratactic style on Whitman is most obvious in the many “And”-headed lines that populate his poetry (185x in the 1855 Leaves), especially when they bunch together (e.g., LG, 15–16 [7x], 19 [5x], 20 [5x], 33 [4x], 34 [7x], 53–54 [8x], 90–91 [5x], 92–93 [7x]).62 As noted (see Chapter Three), this is a refraction in Tyndale’s English (and that of his heirs) of the peculiar Hebrew verb form (the so-called wayyiqtol form which has the conjunctive waw directly attached) that carries the main narrative line in much of the prose in the Pentateuch and Former Prophets. The verse divisions of the KJB (with attendant indentation) serve to highlight these sentence-initial “And”s. With some exceptions (e.g., “And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart,/ And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you held my feet,” LG), the majority of these “And”-initiated lines, of course, are tuned to the present tense of Whitman’s defining nonnarrative pose, viz. “And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves” ().

Parataxis pervades the Hebrew Bible beyond just this one form. Its character varies depending on medium, genre, and style. For example, Alter introduces his discussion of the paratactic style of Ernest Hemingway with a brief stylistic analysis of Eccl 1:4–7, the biblical passage which serves as an epigraph for The Sun Also Rises (1926): “The use of parataxis in both the original and the translation is uncompromising: a steady march of parallel clauses, with ‘and’ the sole connective, and the only minimal use of a subordinate clause occurring in ‘from whence the rivers come’… just before the end.”63 The assessment is correct. However, the language of Ecclesiastes, a relatively late book of the Bible (dating from the post-exilic period) shaped more as autobiography than straight narrative, is quite distinct from that of the earlier parts of the Old Testament that Tyndale translated. There are plenty of conjunctive waws. Eight in the original Hebrew of the passage, five of which are translated with “and” in the KJB.64 But the classic Hebrew wayyiqtol form never occurs and often the word order has shifted to subject-verb-(object) (e.g., dôr [Subj] hōlēk [Vb] “one generation passeth away,” Eccl 1:4; kol-hannĕḥālîm [Subj] hōlĕkîm [Vb] ʾel-hayyām [PP] “all the rivers run to the sea,” Eccl 1:7), no accommodation to English word order is needed.65 Though still paratactic, the look and feel of the Ecclesiastes passage is subtly but significantly different from that of most narrative prose in the Pentateuch—especially note the use of the present tense in the KJB’s translation:

4 One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.

5 The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

6 The wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits.

7 All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

The five “and”s in the translation function as clausal coordinators (as so often in the Pentateuch) but none are in verse initial position. And while “and” is the sole connective used, the “steady march of parallel clauses” often proceeds without any connecting word (e.g., “All the rivers run,” v. 7)—parataxis at its base involves the “placing of propositions or clauses one after another, without indicating by connecting words the relation… between them” (OED). In Leaves lines with a similar profile of multiple line-internal, clause-initial “and”s (usually two or three) are not infrequent (e.g., “I lift the gauze and look a long time, and silently brush away flies with my hand,” LG; “Where the cheese-cloth hangs in the kitchen, and andirons straddle the hearth-slab, and cobwebs fall in festoons from the rafters,” ). Lines headed with “And” seem also to attract line-internal “and”s (e.g., “And counselled with doctors and calculated close and found no sweeter fat than sticks to my own bones,” ; “And lift their cunning covers and signify me with stretched arms, and resume the way,” ). Frequently enough there are bursts of narrativity, sometimes sustained even, in the midst of Leaves’ more typical present oriented temporality, and these are where Whitman’s style can appear closest to the (past-tense) style of biblical narrative. A paradigm example is the vignette about the “runaway slave” from “I celebrate myself”:

The runaway slave came to my house and stopped outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsey and weak,

And went where he sat on a log, and led him in and assured him,

And brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruised feet,

And gave him a room that entered from my own, and gave him some coarse clean clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north,

I had him sit next me at table…. my firelock leaned in the corner. (LG)

The little narrative is evolved in a sequence of parallel clauses with and without connecting words. “And” appears fifteen times in these ten lines. Five of the lines are headed by “And.” In eleven instances “and” heads a clause in which the subject is assumed and thus elided (twice the slave—“and stopped outside”; “and passed north”; nine times the “I” of the speaker) and the verb follows immediately (with or without objects), e.g., “And went… and led… and assured him.” The lines themselves, and especially the individual clauses that comprise the intra-lineal caesurae, are relatively compact and feature mostly concrete, everyday vocabulary—with the occasional compound (e.g., “runaway,” “half-door,” “firelock”) Whitman so enjoyed.66 The vignette as a whole, as M. Klammer remarks, helps to inscribe the kind of “sympathy as measureless as its pride” (LG) to which Whitman aspires, and the repeated use of “and” in the passage (especially at the beginning of lines) emphasizes the bond between speaker and slave—that is, the paratactic style itself is a manifestation of the empathy for and the receptivity to the other.67

On four occasions in the passage “and” functions as an item coordinator (“limpsey and weak,” “his sweated body and bruised feet,” “his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,” “his neck and ankles”). Whitman, in fact, is very fond of this use of the simple conjunction, as is made apparent immediately in the 1855 Preface—“Here are the roughs and beards and space and ruggedness and nonchalance that the soul loves” (LG; emphasis added). The other major role of the conjunctive waw in biblical Hebrew is to conjoin nouns at the phrasal level.68 This is a common use of “and” in English as well, and thus this usage is not marked as such as an indicator of possible biblical influence. Still, Whitman uses “and” very frequently to conjoin nominals. And like Leaves the English Bible is filled with verses containing multiple “and”s, whether conjoining clauses or individual lexemes (especially nouns), viz. “And he rose up that night, and took his two wives, and his two womenservants, and his eleven sons, and passed over the ford Jabbok” (Gen 32:22).

Parataxis pervades the biblical Hebrew poetic tradition as well but in ways that are different still from the patterning in the Bible’s prose traditions. The corpus is dominantly nonnarrative. Therefore, for example, the classical wayyiqtol form appears more sparingly. And the speaking roles and verbal patterns that prevail are those that typify the representation of spoken discourse, whether in orally performed verbal art (which informs, for example, much biblical poetry) or in the written prose of biblical narrative. Two aspects in particular, however, bear on a consideration of parataxis in Whitman. While the conjunctive waw is common (especially as an item coordinator) in biblical poetry, there is also a tendency to adjoin clauses and sentences asyndetically, with no explicit conjunction—this is parataxis at its most fundamental (e.g., “The sorrows of hell compassed me about: the snares of death prevented me,” Ps 18:5). That is, in the poetic sections of the Bible Whitman was confronted with runs of verses, sentences, and clauses that are conjoined contiguously without any or only minimal (often just the simple conjunction “and”—also “but,” “yet,” “or,” “yea”) indication of how these units were to be related. This is very much akin to the basic profile of Whitman’s verse—“the end-stopped lines linked by parallelism, repetition, and periodic stress.”69 More specifically, as discussed in Chapters Three and Four, one of Whitman’s most favored line types is a two-part, internally parallel line in which the second clause is headed by a simple conjunction, usually “and” (e.g., “Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,” LG; “I jump from the crossbeams, and seize the clover and timothy,” ).70 There are literally hundreds of such lines that populate the 1855 Leaves.

It is worth pausing over Whitman’s use of the conjunction “and” and the parataxis it emblemizes. In the 1855 Leaves the conjunction appears 2,544 times (including the Preface). This is not an insubstantial number of occurrences. Such a highly paratactic style is sometimes labeled “primitive.”71 In fact, G. W. Allen explicitly links Whitman’s rediscovery of such a style to the “primitive rhythms of the King James Bible,” emphasizing that the “original language of the Old Testament was extremely deficient in connectives, as the numerous ‘ands’ of the King James translation bear witness.”72 Primitive in such usage is a literary-critical descriptor of a syntactic style (often opposed to a “sophisticated” syntax that more routinely and explicitly discriminates clausal relations of subordination, qualification, consequence, etc.).73 The term should not be construed to imply intellectual simpleness or naiveté. In fact, Allen’s comment about Whitman’s “primitive” parataxis is tied directly to the poet’s hyper-democratic political commitments: “such doctrines demand a form in which units are co-ordinate, distinctions eliminated, all flowing together in synonymous or ‘democratic’ structure. He needed a grammatical and rhetorical structure which would be cumulative in effect rather than logical or progressive.”74 “Form and style are not incidental features” of thought, as M. C. Nussbaum (among others) well explains, but themselves make claims, express “a sense of what matters,” are “a part of content,” and thus “an integral part… of the search for and the statement of truth.”75 That Whitman’s own stylistic preferences (here his preference for parataxis) should suit his politics and even themselves bear political consequence is part and parcel of how language art works. Parataxis, no less than the high sophistication of subordinating syntax, may be disposed toward thinking. G. Deleuze’s philosophical method is a case in point. It relies on a paratactic style of discourse—what he calls “thinking with AND”—to move beyond philosophies of first principles and subordination toward a thinking through of life and world in terms of relations, fragmentation, inclusivity, and multiplicity.76 K. Mazur has even leveraged Deleuze’s ideas to sharpen the political appreciation of Whitman’s formal style.77 Parataxis, as it prescinds from predetermining connections, from privileging order, linearity, and hierarchy, making all equal, suits most congenially the poetics of democracy that Whitman crafts. And thus, as with Whitman’s free verse and parallelism, the choice here of a distinct formal style—parataxis—is not simply a matter of borrowing a biblical model for the sake of that model, but the latching onto (and then developing) a style that is deployed with precise political and intellectual attention. Whitman “thinks with” the “AND” that he finds foremostly in the Bible, and thinks it toward an American democratic polity where “there can be unnumbered Supremes, and that one does not countervail another any more than one eyesight countervails another . . and that men can be good or grand only of the consciousness of their supremacy within them” (LG).

The Periphrastic Genitive

Modern English has two genitive constructions, the s-genitive and the of-genitive.78 The former is a clitic formation that originated in the inflectional morphology of Old English. The latter is a periphrastic and postposed construction, also present in Old English though severely restricted in use there (e.g., mostly in locatives). By the fourteenth century the of-genitive increasingly became the preferred adnominal genitive construction. In part this resulted from changes internal to the development of English (e.g., erosion of inflectional morphology) and in part due to the influence of French de after 1066. In the Early Modern period (1400–1630) the s-genitive again increases in frequency, though now mostly restricted to usages with highly animate (e.g., humans) and/or topical (e.g., proper names) possessors.79 Both constructions are available to Tyndale. However, he almost exclusively uses the of-genitive to render the Hebrew “construct chain,” the commonest means in the language for expressing a genitival relationship between two nouns. The latter consists of a head noun (in construct) followed immediately by its modifier (a noun in the absolute):80

|

Hebrew: |

qĕdôš |

+ |

|

|

(head) noun1 |

+ |

(modifier) noun2 |

|

|

English: |

the-Holy-One-of |

+ |

Israel |

|

Tyndale: |

“the holy of Israel” (> KJB: “the Holy One of Israel”) |

||

Tyndale’s preference for the of-genitive allows him to maintain the word order of the underlying Hebrew, i.e., noun1 + of + noun2,81 and imbues his prose with a distinct rhythmicity that results from the repeated use of this one genitive construction.82 The KJB broadly retains Tyndale’s pattern of usage.

The pattern of usage of the two genitives in Whitman’s poetry is interesting. In the pre-1850 metrical poems the s-genitive is prominent.83 This is understandable since use of the s-genitive provides maximum flexibility in order to accommodate the constraints of meter.84 By contrast, the s-genitive appears relatively infrequently in the 1855 Leaves, only a hundred times,85 while the preposition “of” appears over 1400 times86—Whitman’s expanded, non-metrical line making the space necessary to accommodate the lengthier, less rhythmically regular phrasing of the of-genitive. Less rhythmically regular, however, does not mean non-rhythmical. Indeed, the of-genitive is one of the oft-repeated “syntactical structures” critical to the free rhythms of Whitman’s mature verse.87 This is noticeable even at the level of the line, as in these two- and three-part lines:

You are the gates of the body and you are the gates of the soul (LG)

The rope of the gibbet hangs heavily…. the bullets of princes are flying…. the creatures of power laugh aloud (LG

In both the repeated of-genitive formation helps create a strong sense of parallelism in these lines and provides the lines with their basic rhythmic shape—the repeated vocabulary in the two-part line enhances this feel all the more. Increasing the scale shows what is possible when the patterned repetition is sustained over a longer stretch of lines. Consider this section from “I celebrate myself” (emphasis is mine):

I hear the bravuras of birds…. the bustle of growing wheat…. gossip of flames…. clack of sticks cooking my meals.

I hear the sound of the human voice…. a sound I love,

I hear all sounds as they are tuned to their uses…. sounds of the city and sounds out of the city…. sounds of the day and night;

Talkative young ones to those that like them…. the recitative of fish-pedlars

and fruit-pedlars…. the loud laugh of workpeople at their meals,

The angry base of disjointed friendship…. the faint tones of the sick,

The judge with hands tight to the desk, his shaky lips pronouncing a death-sentence,

The heave’e’yo of stevedores unlading ships by the wharves…. the refrain of the anchor-lifters; (LG)

The adnominal construction itself provides a two-part cadence that then punctuates these lines with enough regularity to be felt rhythmically. The repetitions also help hold the section together. While more difficult to apprehend, the rhythmical effect as the syntagma is repeated throughout the whole of Leaves is not dissimilar. And it is very reminiscent of the “rhythmic repetitiveness” that Hammond notices in Tyndale’s (and by extension the KJB’s) use of the periphrastic genitive.88

Beyond the pattern of distribution in Leaves, there is also a revealing half-line from “I wander all night” that makes clear the deliberateness with which Whitman deploys the two genitives: “The call of the slave is one with the master’s call” (LG). The use of both genitives allows Whitman to provide a chiastic (abba) shaping to the phrase: call + slave [“is one with”] master + call. The chiasm aligns slave and master in proximate adjacency, permitting the equality of their calls at the surface of the phrase to be ghosted by a more revolutionary equality, namely, that “the slave is one with the master.”

That the phrasing preference for the of-genitive is at least in part inherited from the Bible is certain. The overall profile of genitive usage in the 1855 Leaves, both in terms of the pattern of usage89 and the rhythmical consequences of this usage, is broadly suggestive of that of the KJB. A few outstanding of-genitives in Leaves are lifted verbatim from the KJB, e.g., “the hand of God” (LG; 16x in the KJB), “the spirit of God” (; 26x in the KJB), “the pains of hell” (; cf. Ps 116:3), “stars of heaven” (; 11x in the KJB), “pride of man” (; Ps 31:20).90 But mostly Whitman has absorbed this pattern of phrasing and adjusted it to fit his own language. Sometimes the echoes of scriptural phrasing are readily apparent:

“the great psalm of the republic,” LG; cf. “A Psalm of David,” Ps 15; “A Psalm of Asaph,” Ps 82; “A Psalm of praise,” Ps 100

“the begetters of children,” LG—here using a KJB idiom, “beget/begat,” though “begetter” or “begetters” never actually appears in the KJB

“the mother of men,” LG; “Mother father of Causes” and “the Father a Motherof Causes,” “My Soul”;91 cf. “the mother of young men,” Jer 15:8; “the mother of all living,” Gen 3:20; “a mother of nations,” Gen 17:16; “THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS,” Rev 17:5; “father of many nations,” Gen 17:4)

“A word of the faith that never balks,” LG; cf. “the word of faith, which we preach,” Rom 10:8

“in the calm and cool of the daybreak,” LG; cf. “walking in the garden in the cool of the day,” Gen 3:8

“flesh of my nose,” LG; cf. “flesh of my flesh” (Gen 2:23) and “flesh of my people” (Mic 3:3)

“the old hills of Judea,” LG—sounds biblical in part because of the of-genitive but it is not

“dimensions of Jehovah,” LG—of-genitive plus Jehovah (= Exod 6:3; Ps 83:18; Isa 12:2; 26:4) provides the biblical feel to the phrase

“Soul of men,” LG; cf. “the Soul of man! the Soul of man!”, NUPM I, 105; cf. “soul of man,” Rom 2:9;

“born of a woman and man,” LG; cf. “born of a woman,” Job 14:1; 15:14; 25:4; “born of woman,” (2x); cf. “born of women,” Matt 11:11; Luke 7:28)—not an adnominal construction but suggestive of Whitman’s penchant for adapting biblical language

“the pleasure of men with women” (LG), cf. “the way of a man with a maid,” Prov 30:19

“Children of Adam” (LG), cf. “sons of Adam,” Deut 32:8; Sir 40:1; “children of Israel,” Gen 32:32; “children of Simeon,” Num 1:22; “children of Levi,” 1 Chron 12:26; etc.92

“a revelation of God,” “I know as well as you”;93 cf. “revelation of Jesus Christ,” Gal 1:12; 1 Pet 1:13; Rev 1:1

Yet in at least one instance even Whitman’s imitations can be directly tied to the Bible. The Hebrew construct formation is not limited to genitival relationships. Most notably, the superlative in biblical Hebrew is expressed by way of a construct phrase.94 In Deut 10:17 Israel’s god is extolled as the highest god and most superior lord through a pair of conjoined construct phrases, ʾĕlōhê hāʾĕlōmîm and ʾădōnê hāʾădōnîm, which Tyndale renders literally, “God of goddes” and “lorde of lordes.” And this translation pattern prevails throughout the KJB (e.g., “king of kings,” Ezra 7:12; “song of songs,” Song 1:1).95 Whitman is fond of such phrasing. An early example comes in a book notice about Harper and Brother’s Illuminated Bible of 1846, which he calls “the Book of Books”—his phrasing imitating biblical English style to designate the surpassing nature of the Bible (“It is almost useless to say that no intelligent man can touch the Book of Books with an irreverent hand”).96 Such superlatives abound in the early notebooks and the 1855 Leaves: e.g., “the nation of nations,” LG “the race of races,” ; “the art of art,” “the nation of many nations,” (glossed as “one of the great nations”); “the puzzle of puzzles,” ;97 “a compend of compends,” (followed by another of-genitive which emphasizes the rhythmic effect: “is the meat of a man or woman”); “the circuit of circuits,” ; “an apex of the apices,” “mother of mothers,” ; “cause of causes” (2x), NUPM I, 130, 131. The biblical inspiration for this manner of phrasing is patent. There are even a handful of times where Whitman plays on the superlative construction with slight deformations, e.g., “the gripe of the gripers,” ; “mothers of mothers,” ;98 “the myriads of myriads,” “the mould of the moulder,” ; “the wrestle of wrestlers,” ; “the bids of the bidders,” ; “offspring of his offspring,” .

In sum, the periphrastic of-genitive (i.e., the noun+of+noun construction) is a critical element of Whitman’s style in Leaves. Its pervasive usage creates rhythm and coherence and its biblical lineage lends Whitman’s poetry “a Biblical atmosphere” even when the content and language is decidedly un-biblical.99 Whitman’s most famous of-genitive is the title of the volume itself, Leaves of Grass, which S. Halkin’s rendering as a construct phrase in (modern) Hebrew, ʿălê ʿēśeb, helpfully reifies.

Cognate Accusative

Biblical Hebrew, like other Semitic languages, has a root system in which a sequence of (usually three) consonants “stay constant in a set of nouns and verbs with meanings in some semantic field.”100 For example, Hebrew dābār “word,” dibbēr “to speak,” and midbār “mouth” all share the same three root consonants, d-b-r, and meanings related to “speech”—namely, the production of speech (verb “to speak”), the speech that is produced (“word”), and the place of speech production (“mouth”). The root system is relevant grammatically, rhetorically, and tropologically. A common grammatical formation is the so-called “cognate accusative.” This is a construction involving a verb and either an effected or internal accusative that share the same root.101 For example, “your old men will dream dreams [ḥălōmôt (N) yaḥălōmûn (V), from the root ḥ-l-m “to dream”]” (Joel 2:28). This is a form of repetition that Tyndale often made sure to reproduce in his translation:102

“But God plaged Pharao and his house wyth greate plages” (Gen 12:17)

“wherefore hast thou rent a rent uppon the” (Gen 38:29)

“the oppression, wherwith the Egiptians oppresse them” (Exod 3:2)

“this people have synned a great synne” (Exod 32:31)

“the Lorde slewe of the people an exceadynge myghtie slaughter” (Num 11:33)

“I haue herde ye murmurynges of ye childern of Ysrael whyche they murmure agenste me” (Num 14:27)

“When thou hast vowed a vowe vnto the Lorde thy God” (Deut 23:21)

And these carried through to the KJB, and the latter extended this style of translation into portions of the Bible that Tyndale did not translate.103

One of the kinds of repetition that Whitman is enamored of consists of lexically related nouns and verbs, the ultimate model for which is the KJB and its habitual repetitive rendering (inherited from Tyndale) of the cognate accusative. A striking example comes from the 1869 poem, “The Singer in the Prison.”104 In one of the quatrains from “a quaint old hymn” that Whitman sets within the larger poem there is this line: “It was not I that sinn’ d the sin.” Not only does “sinn’d the sin” mimic an Englished version of the biblical cognate accusative, it does so using Tyndale’s very language (“this people have synned a great synne,” Exod 32:31; the combination appears dozens of times in the KJB)—the biblicism, no doubt, intended to lend the “Hymn” sung at “Christmas church in prison” depth and moral weight. This signature grammatical Hebraism occurs a dozen or so times already in the 1855 Leaves:

“It is the medium that shall well nigh express the inexpressible” (LG)

“I do not snivel that snivel the world over” (LG)

“I chant a new chant,” (LG)

“Sea breathing broad and convulsive breaths!” (LG)

“Where the laughing-gull scoots by the slappy shore and laughs her near-human laugh” (LG)

“I fly the flight” (LG)

“Bussing my body with soft and balsamic busses” (LG)

“Long enough have you dreamed contemptible dreams” (LG; cf. Gen 37:9; 40:5; 41:11, 15; Judg 7:13; Dan 2:3)

“to sing a song” (LG; cf. Exod 15:1; Num 21:17; Ps 33:3; 96:1; 98:1; 137:3; 144:9; 149:1; Isa 5:142:10; Rev 15:3)

“and songs sung” (LG)

“and named fancy names” (LG)

“I dream in my dream all the dreams of the other dreamers,/ And I become the other dreamers.”(LG)105

“If you groan such groans you might balk the government cannon” (LG)

The collocations “dream(ed)… dreams” and “sing a song” go back ultimately to Tyndale. The rest are not biblical phrases. Whitman has absorbed the Hebraic pattern and adapted it to his own language and needs. Whitman does not restrict his repetitive play to only verbs with direct objects. Occasionally, he extends his cognate phrasings to include verbs with prepositional objects (so also Tyndale: “sett vpp greate stones and playster them with playster, and write vpo the all the wordes of this lawe,” Deut 27:2):

“Does this acknowledge liberty with audible and absolute acknowledgement” (LG)

“stuffed with the stuff” (LG [2x])

“I will certainly kiss you with my goodbye kiss” (LG; cf. Song 1:2: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth”106

“but a child born of a woman and man I rate beyond all rate” (LG)

“I sleep close with the other sleepers” (LG)

“And swim with the swimmer, and wrestle with wrestlers” (LG

“It attracts with fierce undeniable attraction” (LG)

“It is the mother of the brood that must rule the earth with the new rule./The new rule shall rule as the soul rules, and as the love and justice and equality that are in the soul rule.” (LG

Another Hebrew grammatical formation involving a shared root is the “paronomastic infinitive.”107 In this construction the infinitive (absolute) appears with the same root as the finite verb and adds emphasis to the verb’s semantics, viz. môt [Inf Abs] tāmût [Vb] lit. “dyingly you will die” (Gen 2:17). However, with this formation Tyndale does not normally try to replicate in English the repetition of the original Hebrew but uses instead an adverb plus verb combination, usually involving “surely” (but also “certainly,” “indeed,” “altogether”), viz. “thou shalt surely dye” (Gen 2:17). Though involving no etymological play (in English) even here, Whitman’s debt to Tyndale’s biblical English is occasionally readily apparent, as in the phrase “thou would’st surely die” from “Lilacs” (Sequel)—the paronomastic infinitive with Hebrew m-w-t “to die” occurs scores of times in the Hebrew Bible and inevitably appears in the KJB with Tyndale’s customary gloss (“surely die”).108 There are several points in the 1855 Leaves where Whitman’s language takes on this biblical cadence: “it must indeed own the riches of the summer and winter” (); “the purpose must surely be there” (); “The coward will surely pass away” (); “We should surely bring up again” and “as surely go” (); “I will certainly kiss you with my goodbye kiss” ();109 “You surely come back at last” (); and “he that is now President shall surely be buried” ().

The peculiarity of the Hebrew root system, the strictly grammatical status of the cognate accusative and the paronomastic infinitive in biblical Hebrew, and the habituated means by which these grammatical collocations have been taken into English (following Tyndale) make identifying the (ultimate) biblical source or inspiration of some of Whitman’s etymological figures certain. The root system in biblical Hebrew did not only impact the grammar of the language. It also proved a rich resource for tropological play by biblical writers and performers. The literature of the Old Testament abounds in all kinds of etymological plays, many of which, because of Tyndale’s habit of keeping his English close to the underlying Hebrew, are captured in English translation:

“What profiteth the graven image that the maker thereof hath graven it” (Hab 2:18)

“Therefore all they that devour thee shall be devoured” (Jer 30:16)

“a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted” (Eccl 3:2)

“and sealed them with his seal” (1 Kgs 21:8)

“But be ye glad and rejoice for ever in that which I create: for, behold, I create Jerusalem a rejoicing, and her people a joy.” (Isa 65:18)

“Hath he smitten him, as he smote those that smote him? or is he slain according to the slaughter of them that are slain by him?” (Isa 27:7)

The examples are representative of a much larger phenomenon. As L. Alonso Schökel notices in his discussion of the figural significance of the root system in biblical Hebrew poetry, “the examples are extremely abundant.”110 Whitman, too, is much enamored with etymological plays of all sorts, including many that are of a kind with their biblical forerunners:

“He judges not as the judge judges….” (LG)

“For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you” (LG)

“the plougher ploughs and the mower mows” (LG)

“The palpable is in its place and the impalpable is in its place” (LG

“I turn the bridegroom out of bed and stay with the bride myself” (LG; cf. )

“in a framer framing a house” (LG)

“This printed and bound book…. but the printer and the printing-office boy?” (LG)

“by a look in the lookingglass” (LG)

“the saw and buck of the sawyer” (LG)

“the mould of the moulder” (LG)

“a bundle of rushes for rushbottoming chairs” (LG)

“The swimmer naked in the swimmingbath . . seen as he swims” (LG)

“And the glory and sweet of a man is the token of manhood untainted” (LG)

“he that had propelled the fatherstuff at night, and fathered him” (LG)

“Great is the greatest nation” (LG

Many, many more such plays could be cited. They are central to Whitman’s style. The language, with only rare exceptions (“When the psalm sings instead of the singer,” LG; cf. Ps 98:5), is not biblical. Whitman was well aware of the etymological relationships in English between verbs, nouns, adjectives, and other parts of speech.111 And he had available to him other resources modeling the possibilities for etymological plays in English, including almost two and a half centuries of English language poetry since the KJB was first published (plus Shakespeare, of course).112 It is not necessary to insist that the Bible was Whitman’s only source of inspiration for such plays, or even his main source. But it was one resource well known to him and widely influential (stylistically). The binary pattern (e.g., “voices veiled, and I remove the veil,” ; “I teach straying from me, yet who can stray from me?”, ; “untouchable and untouching,” ) in which so many of these plays are elaborated perhaps offers a vague imprint of the biblical poetic tradition in which such plays often are apportioned according to the doubling logic of much biblical poetic parallelism, whether at the level of the couplet (e.g., “and his king shall be higher than Agag, and his kingdom shall be exalted,” Num 24:7) or line internally (e.g., “Heal me, O LORD, and I shall be healed,” Jer 17:14). Whitman’s etymological plays are not just strictly binary (e.g., “The new rule shall rule as the soul rules, and as the love and justice and equality that are in the soul rule,” ), though many are, and often they are cast in parallelistic patterns that ghost biblical poetic line structures, e.g., “Askers embody themselves in me, and I am embodied in them” (), “casting, and what is cast” (), “He is the joiner . . he sees how they join” ().

In sum, many of Whitman’s figural plays on word formations and etymological knowledge carry forward a tradition in English that dates back to Tyndale and the KJB. In some instances, as in phrases with lexically related verbs and nominal objects (e.g., “It was not I that sinn’ d the sin” from “The Singer in the Prison”; cf. Exod 32:31), the ultimate biblical genealogy is patent. Yet the main point is to suggest a broad stylistic kinship between Whitman and the prose of the English Bible with respect to these plays.

Formatting of Attributed Speech

Whitman’s printerly sensibility (“I was chilled with the cold types and cylinder and wet paper between us,” LG) meant that his poetry was always infused with a strong materialist element. Formatting mattered, even stylistically.113 For example, the use of suspension points distinguishes the poetry of the 1855 Leaves. Whitman introduced poem and stanza numbers to the 1860 Leaves in order to give his book a biblical feel. His line at times clearly mimes the verse divisions of the KJB (see ). Another formatting element borrowed from the KJB is the practice of introducing attributed (or direct) speech with a comma followed by initial capitalization but without quotation marks:

Whether is easier, to say, Thy sins be forgiven thee; or to say, Rise up and walk? (Luke 5:23)

he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you (LG)

The Lukan passage comes from the story of Jesus’ healing of the paralytic (Luke 5:17–26; Matt 9:1–8; Mark 2:1–12; cf. John 5:1–8). Whitman’s language recalls Jesus’ command to “Rise up and walk” (cf. “Arise, and walk,” Matt 9:5; “Arise, take up thy bed, and walk,” Mark 2:9; “Rise, take up thy bed, and walk,” John 5:8), though Whitman likely had in mind one of the raising of the dead stories, such as that of Lazarus (John 11), since “the greatest poet” is said to drag “the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet” (LG). Regardless, it is at least clear here that Whitman borrows language from a Gospel story and formats it exactly as he found it in the KJB.114 This formatting practice is (mostly) consistent throughout the 1855 Leaves:

“He swears to his art, I will not be meddlesome….” (LG)115

“The messages of great poets to each man and woman are, Come to us on equal terms” (LG)

“It is that something in the soul which says, Rage on” (LG)

“A child said, What is the grass?” (LG)116

“Ya-honk! he says, and sounds it down to me like an invitation” (LG)117

“The mocking taunt, See then whether you shall be master!” (LG)

“It says sarcastically, Walt, you understand enough” (LG)

“And chalked in large letters on a board, Be of good cheer, We will not desert you,” (LG)118

“He gasps through the clot…. Mind not me…. mind…. the entrenchments.” (LG)119

“…the voice of my little captain,/ We have not struck, he composedly cried, We have just begun our part of the fighting” (LG)

“And I said to my spirit, When we become the enfolders of those orbs….” (LG)120

“And I call to mankind, Be not curious about God,” (LG)

“She speaks to the limber-hip’ d man near the garden pickets,

Come here, she blushingly cries…. Come nigh to me limber-hip’ d man and give me your finger and thumb,

Stand at my side till I lean as high as I can upon you,

Fill me with albescent honey…. bend down to me,

Rub to me with your chafing beard . . rub to my breast and shoulders.” (LG)

“He says indifferently and alike, How are you friend?” (LG)

“and one representative says to another, Here is our equal appearing and new” (LG)

Occasionally, Whitman leaves out the comma:

“…and say Whose?” (LG)

“Crying by day Ahoy from the rocks of the river” (LG)

“And my spirit said No, we level that lift to pass and continue beyond.” (LG)

“And he says Good day my brother, to Cudge that hoes in the sugarfield;” (LG)121

Quotation marks are never used.122 This practice stands contrary to Whitman’s practice in his other writings (including his pre-1850 juvenile poetry). The last poems to have material enclosed in quotation marks are “Blood-Money”123 and “House of Friends.”124 Both poems are prefaced with epigraphs containing close versions of biblical passages enclosed in traditional quotation marks:

“Guilty of the Body and Blood of Christ” (1 Cor 11:27; “Blood-Money”)125

“And one shall say unto him, What are these wounds in thy hands? Then he shall answer, Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.”—Zechariah, xiii. 6 (“House of Friends”)126

The quotation from Zech 13:6 contains two examples of the KJB’s habitual mode of embedding attributed speech (comma + initial capitalization, without quotation marks), “say unto him, What….” and “Then he shall answer, Those….” The first time Whitman uses the biblical format in the body of a poem is in “Blood-Money” where he offers a version of Matt 26:15:

Again goes one, saying,

What will ye give me, and I will deliver this man unto you?

And they make the covenant and pay the pieces of silver. (lines 12–14)127

None of the poetry in the early notebooks and poetry manuscripts contains material enclosed in quotation marks. There are in these materials, and also in some of the prose selections from the early notebooks, several instances of the format for introducing attributed speech that Whitman uses in Leaves:

“And wrote chalked on a great board, Be of good cheer, we will not desert you, and held it up as they to against the and did it;” (“Poem incarnating the mind”)128

“The poet seems to say to the rest of the world

Come, God and I are now here

What will you have of us.” (“Poem incarnating the mind”)129

“and what says indifferently and alike, How are you friend? (“Talbot Wilson”)130

“and Good day my brother, to Sambo, among the black slaves rowed hoes of the sugar field” (“Talbot Wilson”)131

“and I said to my soul When we become the god enfolders” (“Talbot Wilson”)132

“and the answer was No, when we fetch….” (“Talbot Wilson”)133

“and it the answer was, No, when I reach there….” (“Talbot Wilson”)134

“It seems to say sternly, Back Do not leave me” (“Talbot Wilson”)135

“they each one says in it down and within, That music!” (“The regular old followers”)136

“Ya-honk! he says, and sounds it down to me like an invitation” (“The wild gander leads”)137

“I simply answer, So it seems to me.” (“After all is said”)138

Whitman was aware that “punctuation marks” of all sorts “were not extant in old writings” (DBN III, 367),139 and thus perhaps his motive in adopting such a format was to provide his book with the authority and look of an old poem. Or perhaps it was simply a printerly convenience. And undoubtedly it was part and parcel of that “cleanest expression” he aspired to fashion, namely, “that which finds no sphere worthy of itself and makes one” (LG).140 Yet whatever the motivation, that the Bible furnished Whitman with one model for such a practice may be confidently surmised, and thus one more indicator of Whitman’s biblicizing style.141

* * *

To summarize, I have identified a handful of elements in Whitman’s style that may be directly connected to the prose style of the King James Bible. There is much more to Whitman’s “divine style” than an accounting of these several elements can offer. Still, these elements do furnish a concrete means of showing where that style has been imprinted by the prose of the KJB. In particular, Whitman’s use of parallelism (see also Chapter Four), parataxis of various kinds, the of-genitive as a superlative (e.g., “the Book of Books”), verbs with lexically related direct objects (e.g., “chant a new chant”), and the format for introducing attributed speech (comma + initial capitalization, without quotation marks) have (relatively) unambiguous biblical genealogies. These are mostly formal elements and thus devoid of positive semantic content, which made it all the easier for Whitman to take them up and shape them to his own ends; for perceptive readers he gets the biblical feel without biblical content (except what he finds congenial to his project). And while it is difficult to concretize in the same way, that the non-narrativity of so much of Whitman’s poetry bears a kinship with the chunks of nonnarrative prose of the KJB, especially in the latter’s present tense dominant renderings of the “Hebraic chant” of biblical Hebrew poetry, is of significance; it brings the fact of a nonnarrative English prose style descending from the KJB into stark relief.

Prose into Poetry

The large point of the previous section is to identify elements of Whitman’s poetic style that derive (ultimately) from the prose style of the KJB. In these takings from the Bible, Whitman exercises one of his most characteristic modes of composition, collage. Whitman’s practice of collage has been well observed, especially in Miller’s Collage of Myself. Often enough what is found by the poet is a readymade piece of prose (whether his own or someone else’s), which he then shapes into poetry. Numerous instances of this turning of found prose into poetry have been identified or discussed in the preceding pages. When it comes to the Bible, Whitman’s practice of collage is not different. A most telling (if early) example is the passage from “Blood-Money” in which the poet offers a slightly adjusted and lineated version of Matt 26:15:

Again goes one, saying,

What will ye give me, and I will deliver this man unto you?

And they make the covenant and pay the pieces of silver. (ll. 12–14)

Here Whitman is quite literally culling lines from the prose of the KJB, turning major syntactic junctures into poetic lines. What changes in the immediate lead-up to the 1855 Leaves for Whitman is the evolution of a poetic theory that proscribes using such close renditions of traditional literature like the Bible. Some biblical content (language, imagery, ideas), whether literally, allusively, or echoically, gets into the early Leaves (see Chapter Two). Yet what Whitman collages far more liberally and in greater quantities from the Bible are non-semantic features of various sorts—tropes (e.g., parallelism), presentational dimensions (e.g., verse divisions), forms or kinds (e.g., lyric, non-narrativity), prosody (e.g., no meter), elements of style (e.g., parataxis, periphrastic genitive). Lacking semantic content these features do not betray their source so obviously and easily accommodate new or different content. They are readymade for reuse and recalibration. Parallelism, for example, may be fitted out with Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” (instead of the “Hebraic chant” of the Bible) and its play of iteration adjusted to suit the linguistic infrastructure of English (see Chapter Four). The scale of these latter takings—to think just of Whitman’s use of parallelism, the conversion of biblical verse divisions into long, end-stopped, often two-part lines, and the prominence of parataxis—is actually quite immense. Allen’s contention that “no book is more conspicuous in Walt Whitman’s ‘long foreground’ than the King James Bible” is not overstated.142

Not a few of the stylistic elements discussed above (e.g., plain, everyday diction, parallelism, parataxis) show up consistently in the American prose style that Alter reveals in the novelists he studies. These shared elements and their common biblical ancestry are part of why I have considered Whitman’s style in light of Alter’s thesis. Alter’s work makes apparent the importance of prosaic style to Whitman’s poetry. The place of prose in Whitman’s writing, and especially in the style of poetry that he evolves for Leaves, is more thoroughgoing still. Prose was what Whitman read and wrote most in the years prior to the 1855 Leaves. This is a view that J. Loving underscores when he notices the importance of Whitman’s development of the “essay form” in the 1840s writing for the Aurora: “It is from the essay, more than anywhere else perhaps, that Whitman’s use of free verse came into being.”143 And it is the sententious style and stretched out rhythms of prose that seem to best suit his writerly temperament, leveraging, as it does, “the language of the profession he trained himself for, journalism.”144 Whitman was a writer of prose (lots of it), and ultimately in Leaves he became a writer of a poetry infused with pronounced prosaic inflections. The break with meter in 1850 enabled a long(er) line and the gradual shaping of that long(er) line throughout the early 1850s creates the expanded space necessary to accommodate a poetic discourse injected with prosaic sensibilities—“a sort of excited prose broken into lines without any attempt at measure or regularity.”145 Therefore, not only does Whitman borrow elements of style from the prose of the (English) Bible—just like Alter’s authors; but prose itself is central to his sensibility as a writer. Much of the poetry of the early Leaves was itself culled from prose and retains this inherited prosiness in various ways; and, as important, even the poetry that began as poetry, in lines, without obvious prosaic mediation, this poetry, too, takes advantage of the flexibility and freedom of prose and uncoils its syntax in elongated lineal stretches with leisurely patience and the extended rhythms otherwise characteristic of prose. There is perhaps no better indicator of the importance of prose to Whitman as a writer, especially early on, than the fact that the 1855 Leaves is itself introduced by ten pages of prose, which stylistically is so close to the poetry that follows that much of it would eventually be culled into lines for poems (e.g., “Poem of Many In One”146 and “Poem of The Last Explanation of Prudence”147 from the 1856 Leaves). Whitman may be viewed properly as participating in the “American prose” tradition that Alter identifies.