23. Financing Our Final Hour

© 2024 Luke Kempet et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0360.23

Highlights:

- This chapter asks the question: “Should institutional investors act to reduce Global Catastrophic Risks? What are their obligations? And if they should, how can they best do so?” The authors review existing investor campaigns on global risks alongside literature from finance, economics, corporate law and ethics to identify and assess the different motivations and tactics for institutional investors to act on potential global catastrophic risks.

- There are at least four rationales that campaigns have already articulated: ethical arguments, legal considerations, financial incentives, and risk avoidance. To these the authors add two new justifications: long-term self-interest and universal ownership.

- Global Catastrophic Risks are relevant to corporate governance, and there are grounds for potentially generalisable ethical and legal obligations towards catastrophic risks. To this end, the chapter argues that a rational and ethical institutional investor should adopt a Financial Hippocratic Oath to not contribute to global risks, while those with deeper stakes, such as Universal Owners, should commit to a Financial Oath of Maimonides: to use their investments to minimise global risks.

- The authors also ask how institutional investors can use their money and influence to reduce global risks. They propose six different tactics for achieving this end: contest, protest, request, divest, reinvest and acquest.

- Investor campaigns benefit from an issue with a clear, compelling “moral villain” (an actor that plausibly increases global risks), profitable alternatives for reinvestment, investor leverage and a strong underpinning campaign. These factors apply to many global risks, including climate change, nuclear weapons, and Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs).

This chapter was written over many years as a response to issues raised by the global divestment movement. This work led, in part, to the University of Cambridge deciding to divest its own investments from fossil fuels via the role played by Dr Quigley on a secondment to the university’s Chief Financial Officer. The role of political economy in extreme global risk is discussed in Chapter 2, while the consideration of different mechanisms for global risk reduction draws on the research presented in Chapter 19.

Introduction

In 2015 students at Swarthmore College crowded the halls of the administration building. They sang, picketed, and occupied it for 32 consecutive days. The sit-in protest was part of a campaign that dated back to 2011.1 It originally demanded that the faculty withdraw their investments from the “sordid sixteen”: a group of 16 US oil, gas and coal companies with appalling human rights and environmental track records.

This was the beginning of the “fossil free” divestment movement (divestment usually referring to investors’ sale of shares (public equity) in target companies; it may also extend to the sale of bonds and other financial instruments). It has spread like a contagion since then. As of 2022, 1508 institutions, collectively worth US $40.43 trillion, had pledged to divest from fossil fuels.2 The types of commitments vary. Some restrict their divestments to a particular type of fossil fuel, such as coal, while many direct their divestment commitments towards the top 200 fossil fuel companies by reserves held. The approach of the “fossil free“ divestment movement has since been adopted by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) through their ‘Don’t Bank on the Bomb’ campaign,3 a group which pushes for institutional investors to divest from nuclear weapons producers and publishes annual reports (since 2013) on who produces and funds nuclear weapons (institutional investors are large entities that pool money to purchase different investment assets; these include banks, pensions, endowment funds, hedge funds and mutual funds).

Many other global risks exist or are on the horizon but have yet to be the subject of investor campaigns. “Global risks” are risks that profoundly threaten the global economy and society.4 Such risks are increasingly well known, but surveys suggest that there is a gap between the higher concerns of scientists and those of business leaders.5 Of these risks we are concerned with those that could produce a global catastrophe, ranging from killing a significant (10–25%) proportion of global population to even resulting in human extinction.6 Nuclear war,7 or catastrophic climate change8 are examples of such catastrophic threats. We may also soon face additional global risks from emerging technologies such as synthetic biology and advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems.

The likelihood of many of these risks is highly uncertain and potentially very low. However, we should be careful not to underestimate the chance of any of them occurring. For instance, one probabilistic historical analysis of inadvertent nuclear conflict put the odds at 0.9%.9 This does not consider the possibility of a hostile first-strike, not of nuclear conflict between other powers. Under a plausible scenario of greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations reaching 700 parts per million (which would be achieved under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change “Middle of the Road” scenario) there is approximately a 10% likelihood of warming exceeding 6 °C.10 This does not account for many potential tipping points, and hence the odds could be even higher. Regardless of probability, such risks are of critical importance to society, corporations, and shareholders. Risk is contingent not just on probability, but impact. Rare, impactful events shape the world, including the financial sector.11 The risks we discuss here can cause tremendous harm, including the dissolution of some of the most powerful industries (or in the case of extinction, all of them). Rather than focusing on setting an arbitrary probabilistic threshold, we suggest focusing on plausible risks: ones which are in line with our background scientific and intellectual knowledge.12 The risks we will cover here ranging from nuclear war to climate change and lethal autonomous weapons are either already occurring or could plausibly cause a global catastrophe.

Ethically, the threat of large-scale mortality or extinction can be a concern for multiple reasons, ranging from the loss of countless future lives,13 breaking our obligations to past generations,14 to simply the harm it would cause to existing, living beings. Most moral value theories can agree that such catastrophes would be wrong, although they differ in their reasons as to why and how bad this would be.15 While ethics is always contested philosophically, there are good reasons to believe that catastrophe and extinction is largely a point of convergence. This is particularly true for the public common-sense notion of the word rather than the philosophical one.

These global catastrophic hazards overlap with systemic risk, a concept that is widely discussed in corporate finance and business ethics. Systemic risk refers to the ability for individual disruptions to cascade into system-wide failure due to the vulnerabilities and structure of a system.16 The Global Financial Crisis is the example par excellence of financial systemic risk. Systemic risk does not need to be global or catastrophic, but under the right conditions it can be. This is particularly the case when a situation of systemic risk leads to reinforcing, “synchronous failures”.17 While systemic risk is relevant and related, we focus instead on Global Catastrophic Risks.

Beck once reflected that the risk society is born from the unforeseen and unintended consequences of systemic behaviour.18 He was wrong: global risks are often anticipated, developed and funded by a select few. Companies, and the investors that finance them, are key contributors to anthropogenic global risks. This is true of climate change, nuclear weapons and many emerging dangerous technologies. Since 1988 71% of global GHG industrial emissions can be traced back to 100 companies.19 Fewer than 30 private companies underpin the maintenance and development of nuclear weapons systems.20 The development of lethal autonomous weapons take place within an oligopolistic marketplace dominated by tech giants.21 39 of the 72 ongoing projects to research and develop high-level machine intelligence (defined as “a general or specific algorithmic system that collectively performs like average adults on cognitive tests that evaluate the cognitive abilities required to perform economically relevant tasks.”22 This is also frequently referred to as “Artificial General Intelligence” (AGI), including in the two surveys mentioned here) are taking place within companies.23 This marks an increase in private sector projects since 2017.24 The actions of a small number of investor-owned companies are fuelling future catastrophe.

The implications of global risks for corporate governance and business ethics appear to be chronically understudied. We used the Existential Risk Research Assessment25 — a machine-learning algorithm which collects global catastrophic risk literature and is updated monthly26 — to search across a sample (available on request) of 15,000 relevant papers produced by TERRA using the search terms “corporate governance”, “business ethics” and “corporate ethics” and find any that directly address corporate governance or business ethics. The one relevant piece we could identify examines the intersection between sustainability discourse and risk management in business ethics,27 but does not directly deal with Global Catastrophic Risks. Given the significance of catastrophic risks to corporate ethics and profits this is perplexing. We suspect that this lacuna is due to their being little overlap between Global Catastrophic Risk studies and the sub-fields of business ethics and corporate governance. Despite this, some relevant literature exists. There have been some initial efforts to reveal the ownership patterns and financial actor behind global environmental changes such as deforestation of the Amazon Rainforest and boreal forests.28 But much more is needed to locate the key financial actors involved in creating global “Anthropocene Risks” and determine their obligations and responsibilities.29 To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has systematically examined the credibility of the underlying arguments for investor campaigns, including for global risks. The Fossil Free movement has received the most academic attention. This has included how it has sowed the seeds of anti-fossil fuel norms,30 how the movement has operated31 and its battle for legitimacy with the fossil fuel industry.32 Despite this coverage the literature has not examined investors’ motivations for shifting their investments to address climate disruption, let alone for a broader suite of global risks.

Global risks (excluding burgeoning action on climate change) also appear to be underappreciated in corporate and financial practice. the prevention of global risks has rarely been considered a part of responsible investment. For instance, during 2016 in the UK around £81 billion was invested in funds with “green” or “ethical” principles.33 None of these funds have enshrined the mitigation of global risk as an explicit principle or objective, and only a small proportion would have represented true “impact” investments.

We address this critical gap in the literature by providing a novel interdisciplinary study and classification of the reasons for institutional investors to manage global risks via their investment strategies, and the tactics they can use to achieve this. Our analysis is valid not only for existing campaigns on climate change and nuclear war, but for campaigns on global risks more broadly. We focus solely on institutional investors and their associated campaigns. This focus covers both institutional investors, and the campaigns by students, activists and others which lead to them taking action.

In Part I we focus on the motivations behind investor campaigns. The analysis proceeds by first discussing what institutional investor campaigns are and what they aim to do. Section 2 examines the multiple different profit-driven and nonprofit rationales for factoring global risk alleviation into investment decisions. Section 3 analyses whether the different reasons for investment redirection hold for all global risks. We find that there are compelling grounds for institutional investors to manage global risk via their investment strategies, built on a range of legal, ethical, economic and political considerations.

Part II examines the tactics of investor campaigns and whether they can be an effective tool for tackling global risks. We proceed by exploring six tactics at the disposal of institutional investors. This is followed by an examination of when investor campaigns are likely to be effective. We then investigate whether investor campaigns could be useful tools for preventing different global risks before concluding with an analysis of ways in which investor campaigns could begin to tackle dual-use technologies.

PART 1 — Institutional Investors’ Obligations to Manage Global Risks

1. Background: The purpose of institutional investor campaigns

The activities of corporations have enormous consequences, for good or ill. Several actors have influence over company management and therefore corporate conduct. These include clients, employees, governments, and publics. We focus on one type of entity: investment funds, especially those of institutional investors. Institutional investors are organisations that pool the money of their members and invest on their behalf. Examples include pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowment funds (for religious, educational and other non-profit institutions), insurance companies, and banks. They are notable due to their power and motivations, which can be different than those of individual (or “retail”) investors or corporate management. Two features that characterise many, but by no means all, institutional investors are their relatively long-term outlook, with many even mandated to preserve the health of their investments in perpetuity, and the breadth and size of their investments, which can come to approximate a representative sample of the economy as a whole.

Over the past four decades “investor campaigns” have become prominent. These involve investors using financing and shares as a way to shift corporate conduct in a more ethical direction. These have included campaigns around the Apartheid regime, tobacco companies, arms companies, nuclear weapons and fossil fuels companies.34 We consider investor campaigns to include a broad range of approaches, encompassing a suite of tools used to reshape investment patterns, corporate conduct, government policy and consumer behaviour from socially harmful to beneficial activities. These tools range from “shareholder activism” (investors using their voice and influence “from the inside” to directly pressure corporations to change their harmful behaviour) to “divestment” (selling shares in target companies). The commonality across investor campaigns is an explicit aim to brand particular activities or companies as morally wrong, or “sinful”, and steer financing away from these activities or companies.

Investor campaigns have experienced mixed results; their effectiveness depends on how their impact is measured. Some activists hope to affect companies’ share prices directly through divestment. Yet historical evidence suggests their influence in financially undermining industries such as tobacco, gambling and arms production has been negligible because divestment efforts have tended to focus on public equity, where shares pass from shareholder to shareholder without any exchange of capital with the company itself.35 Most of the companies in these sectors continue to be profitable and widely invested in. Campaigners have targeted the tobacco industry since the 1980s, yet the industry remains globally profitable and a mainstay among fund managers. While the Fossil Free movement and Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign are spreading rapidly, they have also caused comparatively little financial harm to the companies they are targeting.

However, these campaigns usually do not aim to undermine the share price of destructive industries. Instead, the goal is to eliminate their social license to operate: to make targeted companies into pariahs, to change corporate and consumer behaviour, and, above all, to make them susceptible to more stringent government policy. Partially due to these campaigns, the tobacco industry has now fallen under aggressive excise tax and advertisement regulatory regimes in many countries. Investor campaigns targeted at landmines and cluster munitions were closely involved with the wider political and diplomatic campaigns that led to the international treaties prohibiting these weapons. As Fihn notes for nuclear weapons, “prohibition precedes elimination”.36 Divestment can be regarded as a public shaming tactic, one aimed at changing corporate activities, public discourse and government legislation. It need not directly harm the companies’ share prices to be effective. Bergman concluded in a study of the Fossil Free movement that while the direct impacts have been small, the indirect impacts such as changes in public discourse have been significant.37 While not a silver bullet, social stigmatisation may affect both corporate and government activities.

Investor campaigns such as those that target nuclear weapons and climate change could cover other global risks in the future. Divestment is a strategy that has been employed by social movements since at least the 1980s.38 Theory and empirical studies suggest that social movement tactics, such as divestment, can spread both between groups within a movement, via intramovement diffusion, and across different movements, via intermovement diffusion.39 Specific tactics, such as prolonged sit-ins to push for divestment from apartheid South Africa, quickly spread across universities in the US and internationally in the 1980s.40 Student protests against investments in apartheid South Africa forced IBM, Ford, General Motors, and Exxon Mobil, among others, to withdraw from South Africa. The targets spread to companies associated with arms, tobacco and human rights violations in the 1990s.41

Emerging global risks, such as the development of lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs), advanced AI systems and bioengineering technologies, could be the next battlegrounds. Indeed, Pax (the organisers of the Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign) are now focusing on preventing an AI arms race.42 This includes pushing the private sector to “commit to not contribute to the development of lethal autonomous weapons”. This raises the question: are investor campaigns justified in targeting global risks? In short, should institutional investors care about global risks?

2. Analysis: Motivations for investor campaigns

This section surveys four existing motivations for investor campaigns related to global risks, and introduces two new ones. The “existing” motivations have been publicly voiced in relation to fossil fuel and nuclear weapon investor campaigns. They include motivations stemming from ethical and legal obligations, including potential legal obligations. They rely on either the adoption of new laws in multiple jurisdictions (e.g. codetermination legislation) or a specific legal interpretation of an institution’s purpose (the argument for institutional perpetuity). They also include profit-based motivations to reduce volatility and risk. We also introduce two newly proposed motivations: long-term institutional survival and Universal Ownership Theory. These ideas are not novel, but their use as a justification for shaping institutional investment in relation to catastrophic risks is. Institutional investors depend on wider social stability. It is not in their interests to jeopardise or undermine global stability in the long-term. Their interests rely in stability and avoiding Global Catastrophic Risks. These reasons are not discrete and often interrelate. For example, acting ethically (ethical obligations) could improve a company’s image (or mend a tarnished one) and aid in profits in the longer-term. Table 1 presents our novel classification of these motivations.

The motivations are generally universal. However, there are some caveats. Organisations’ articles of incorporation and bylaws vary greatly, and their obligations rooted in corporate law will vary based on where the company is headquartered, while obligations arising from financial law will also depend on where they are listed or incorporated. The degree of freedom permitted under the Business Judgement Rule will in turn vary according to jurisdiction. Moreover, some organisations are more sensitive to particular rationales. As a general assumption, churches and public bodies such as universities might be more receptive to duty-based reasoning, while corporations might be more persuaded by self-interested arguments that align with their underlying profit motive and fiduciary duties.

Table 1: Motivations for investor campaigns.

2.1 Non-profit-based arguments for investor campaigns

2.1.1 Ethical obligations

Investor campaigns may be driven by an ethical claim: investors should not support, or benefit from, products and services that cause significant social harm. In short, it is wrong to profit from harm. This ethical imperative has been among the most prevalent discourses within investor campaigns. Efforts to change company activities from the inside often appeal to the “better angels” of management. Divestment relies on stigmatising controversial and ethically questionable holdings as “sin stocks”. This ethical branding has been used in the divestment campaigns for both nuclear weapons and climate change. The Don’t Bank on the Bomb 2018 report warns financial institutions that support nuclear weapons producers that they will become “increasingly isolated and stigmatised” unless they divest.43 Similarly, the Fossil Free divestment movement is a battle over hearts and minds.44 Campaigners aim to discredit and de-legitimise an industry. The campaign has hinged on the simple notion that there are no pensions and no use for degrees on a dead planet. McKibben contends that universities that invest in fossil fuels create a tragic situation in which “educations are being subsidized by investments that guarantee they won’t have much of a planet on which to make use of their degree”.45

Appeals to the ethical principles of investors occur in three key ways. First, they may appeal to institutions’ supposed commitments to generalised ethical principles, which can reflect a diversity of ethical traditions and schools of thought.46 Second, they may demand consistency between an investment and the stated principles of the investor or shareholders. This is particularly important for institutions with higher ideals, such as a university, government or religious institution. Deviation from these principles, or the standards of wider society, can grievously injure the reputation of a company or investor. Third, they may influence the individuals involved in the institutions. Executives at companies and institutional investors are not purely economic agents; they consider their reputations and identities when acting.47

Additionally, institutional investors have a duty to their stakeholders not to put them at undue risk, including from global catastrophes that they have the power to influence. By tacitly supporting corporations that are contributing to global risks, these institutional investors are in turn potentially placing their stakeholders in harm’s way. Investors’ responsibilities to their stakeholders should not be limited to purely financial matters where other pressing interests of theirs are at stake.

Ethical obligations could also stem from theories of corporate governance. Stewardship theory sees management and leaders as having a responsibility to guide and protect the long-term performance of a firm.48 Others have sharpened this to “ethical stewardship”: the “honoring of duties owed to employees, stakeholders, and society in the pursuit of long-term wealth creation”.49 Such an approach to leadership lends itself to protecting against catastrophic risks. Preventing global calamity is clearly in the interests of both society and long-term wealth creation, and as highlighted in Section 3.2 is compatible with, if not supportive of, firm performance. An ethical steward would ensure that their employees, society and stakeholders do not face undue, dire risks.

Note, that this is a description of how ethical obligations are articulated, and why they are reasonable. They are not an argument that companies will act ethically. Indeed, there is ample evidence that unethical conduct is brazen and rife in many industries including pharmaceuticals, arms production, and finance.50 This is not a naive plea that institutional investors will comply with ethical demands. Rather, that these ethical obligations exist, are sensible, and are one of many pressures that can change the behaviour of institutional investors and companies.

Following these ethical arguments, which can only be enforced through individual consciences and the court of public opinion, the next subsection will explore the potential of arguments that can be enforced in courts of law.

2.1.2 Legal considerations

Institutional investors are currently under some legal obligations in relation to global risks. There are several possible pathways for them to be considered under other legal obligations.

(a) Considerations relating to domestic and international legal obligations

Institutional investors fall under various existing legal obligations in relation to global risks. These often depend on legal structure and the jurisdiction in which they are incorporated or listed. For example, fiduciary duty for pension trustees is increasingly being interpreted as incorporating the duty to include climate risk into investment analyses. In the UK, the Bank of England specifies how financial institutions are obliged to account for climate change risks.51 ClientEarth recently reported four major UK companies to the UK regulator, the Financial Reporting Council, for failing to address climate change risks in their shareholder reports.52 Similar legal hurdles are arising in the world of nuclear weapons. A company operating in a country that has ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons will be bound by the provisions against contributing to the development, testing, production, stockpiling, stationing, and transfer of nuclear weapons. Legal obligations exist in both international and domestic law.

(b) Considerations vis-à-vis employees

Corporations and other institutions have existing legal (de lege lata) obligations to their stakeholders that could underpin claims to change corporate behaviour or divest. Most larger corporations have hard statutory obligations towards their employees and other stakeholders beyond labour contracts, workplace safety and future pension entitlements. More specifically, laws of codetermination provide workers with a legal right to participate in the management of companies in which they are employed. Such a model is already practised in numerous jurisdictions such as Germany, Austria, Sweden, France, Denmark and the Netherlands, with the German Codetermination Act (Gesetz über die Mitbestimmung der Arbeitnehmer) of 1976, based on an earlier law from as early as 1951, representing a prominent statutory example. The purpose of the codetermination model is to represent the interests of workers alongside the predominating interest of shareholders. Current employees normally have a vested interest in avoiding global risks, both in preserving their own health and well-being as well as that of future generations. In the future, long term-oriented employees might begin to use co-determination to oblige their institutions to move away from risky activities and towards socially beneficial ones. This has yet to occur, but is a promising legal avenue. In this case, co-determination laws are an enabling factor, but action still rests on employee motivation and power relationships.

(c) Considerations relating to fiduciary duties for profit and return

A common objection to divestment and company or sector exclusions is that institutional investors usually cannot legally divest or exclude holdings for moral reasons as this would violate trustees’ duties to beneficiaries. For instance, the Business Judgement Rule states that executives have a fiduciary duty to act in good faith, loyally, with due care (Cede & Co. v. Technicolor, Inc., 634 A.2d 345, 361).53 Similar rules exist in five European states, namely Germany, Romania, Croatia, Greece and Portugal,54 and their obligation to maximise profit for shareholders. Similarly, institutional investors sometimes claim that they cannot engage in campaigns due to fiduciary duties to their trustees to maximise returns and maintain a sufficiently diversified portfolio.

These contentions are all highly contested. Legal experts and scholars have laid out a compelling case in multiple jurisdictions that not only is divestment from certain companies or sectors permitted55 but investing for impact may be legally required. This is because investment returns — and benefits to beneficiaries — rely on the health of the overall economy.56 Some scholars have suggested that the singular duty to maximise returns is an ideological myth and that fiduciaries instead must meet several different fiduciary obligations.57 Importantly, even if this were true there is little evidence that divestment injures profits for companies or returns for investors (see Section 2.2). There are similarly no strong grounds that divestment will injure the diversity of a portfolio substantially enough to violate duties to trustees. This is clear in the long history of investors that have divested from numerous areas (such as tobacco, arms, and gambling) without substantially reducing portfolio diversification.

2.1.3 Protecting investments in perpetuity

Many institutions were founded with the implicit or explicit aim to continue in perpetuity. This includes many schools, universities, and colleges,58 religious institutions,59 NGOs, and some charitable endowments, referred to in the UK as “permanent endowments”.60 Their founders clearly envisioned that they would continue forever. Others, such as sovereign wealth funds and pension funds, are predicated at least on long-term, if not perpetual, existence. The Norwegian Oil Fund’s mission statement is “to safeguard and build financial wealth for future generations”.61 Similarly, much of international law is based on the assumption that states are perpetual.

These institutional investors therefore have a special obligation to ensure the survival of their institution and guard against risks that might destroy it. Global risks that would produce a substantial disruption to the global economy could lead to the bankruptcy or destruction of many corporations and investment vehicles. Indeed, these global risks are some of the few events that could lead to such an outcome for significant swaths of an investor’s portfolio. Thus, investors have an obligation to ensure that they are not contributing to them occurring. The investments of these institutions should be compatible with a vision of themselves as a long-term or perpetual institution. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel and overlooked rationale that has not been prominently used in existing investor campaigns or discussions.

This is not an argument that commitments to perpetuity will de facto lead to a sober consideration of global risks. For instance, the majority of capital inflow for the Norwegian Oil Fund comes from oil and gas extraction. Its commitment to safeguard future generations is at odds with its contributions to climate change. This is an argument that pledges to exist in perpetuity are one (often underexploited) reason that these actors should be acting to address global catastrophic risks.

2.2 Profit-based arguments for investor campaigns

2.2.1 Profiting from investor campaigns

There is tentative evidence that socially responsible investment portfolios may be just as profitable as irresponsible ones. This has been substantially explored in the case of portfolios excluding fossil fuels. Trinks et al. compared portfolios with and without fossil fuel stocks over the period 1927–2016 and found that a fossil-free portfolio’s performance was similar to that of a portfolio including fossil fuel stocks.62 Grantham conducted a comparable study looking at nine major sectors in the stock market and the US-listed companies included in the S&P 500 Index over the past three decades.63 He found that excluding any single sector made no significant difference in portfolio returns. Excluding energy actually increased returns by three basis points. This finding is supported by several earlier studies showing no or little impact of fossil fuel screening on portfolio performance;64 contrary to some claims, divestment does not appear to weaken financial performance. In fact, one study found that a fossil-free portfolio (S&P, excluding fossil fuel companies) outperformed the S&P 500 Index and a fossil-fuel orientated portfolio within the S&P 500 over an eight-year period between 2010 and 2018.65 Finally, the Cambridge divestment report summarised all of the above studies and all of the other peer-reviewed analyses available, concluding that although it is possible to time fossil fuel divestment well or poorly because fossil fuels have outperformed or underperformed the market at different points, judging from a review of studies covering 118 years of data there was little overall difference between fossil-free and conventional portfolios.

Evidence on the performance of socially responsible investments is similarly mixed. Dimson, Karakaş and Li find that after shareholder engagement, particularly on environmental and social issues, companies experience improved accounting performance and governance as well as increased institutional ownership.66 Yu looked at the monthly risk-adjusted returns for 321 funds over 1999–2009 for both social-screened and conventional mutual funds.67 He found that funds in the ethical governance and social categories outperformed their conventional peers. However, there is a debate in the literature as to whether socially responsible portfolios outperform conventional ones.68 For example, some studies suggest that investors who have maintained shareholdings in tobacco may have benefited disproportionately relative to those who divested.69 In general it is still debatable whether socially responsible investment funds outperform, underperform, or match market performance.

There is a connection between the profit-motive and ethical obligations. That is, breaking ethical norms can injure a firm’s reputation. As mentioned earlier, this loss of reputation can affect an investor's or company’s bottom line by enabling regulation, or by leading to boycotts and consumer backlash.

2.2.2 Avoiding legal and reputational risk

If a particular line of business or “sin stocks” will likely become a pariah, or become the object of stringent regulations, then shifting corporate behaviour or withdrawing early can avoid losses. Institutional investors can evade risk by encouraging change or divesting.

Selling stocks before a tidal market shift can be lucrative. Several investors made small fortunes by foreseeing the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis and shorting the market.70 These are cases of investors profiting from a market collapse rather than widespread divestment, but the fundamental premise is the same: it is possible to generate profit and/or avoid risk by diverting funds before a hidden systemic risk is realised by the wider market. The idea is simply to escape the bubble before it bursts.

Such bubble thinking has been prevalent in the Fossil Free movement. It was influenced early on by Bill McKibben’s Rolling Stone article ‘The Terrifying New Math of Climate Change’.71 His popular piece drew from a report by Carbon Tracker on ‘Unburnable Carbon’.72 Unburnable carbon refers to fossil fuel stocks that need to remain buried and unused to limit temperature rise to 2°C. One study by McGlade and Ekins suggests that unburnable carbon could represent known reserves as high as 96% of coal, 54% of conventional oil (100% of unconventional) and 69% of conventional (82% of unconventional) gas.73 Thus the Fossil Free movement argues that, due to this unburnable carbon, investments in the fossil fuel industry are financially reckless.74 The stock price of these companies is built on inflated valuations of unburnable carbon and stranded assets. This asset value will need to be prematurely retired and written off to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Such losses could be significant. Mercure et al. estimate that the losses from stranded assets may amount to a discounted global wealth forfeiture of US $1–4 trillion.75

We argue that the same approach can be applied to “sin stocks” beyond fossil fuels. Trying to change the activities of (or create an early exit from) controversial companies is rational if there are good reasons to believe that government intervention, technological advances, or a divestment contagion will permanently drop the price. This could occur with fossil fuels, nuclear weapons, lethal autonomous weapons and advanced biotechnological and AI systems. Companies in these areas could be in a bubble of underpriced risk. Divestment or dropping particular lines of business entails escaping the bubble before the risk is addressed by government or the judiciary. Which branch of power, the legislature, the judiciary and the executive, creates the legal risk will vary by jurisdiction and case. In Japan the bureaucracy is empowered to change the financial industry. In the US the power rests primarily in the courts.

However, there is some scepticism as to whether one can divest oneself out of a bubble, carbon or otherwise. First, the timing is notoriously difficult to get right. This is evidenced by the rise of passive investing at the expense of active investing (where stock-picking, and its timing, are of paramount importance). Second, some evidence suggests that climate risk may be largely “unhedgeable”. One simulation of a variety of types of diversified portfolios found that it was possible to hedge against less than half of climate risk.76 The nature of Global Catastrophic Risks or existential risks is that they affect the planet as a whole, and therefore cannot be avoided through clever or prescient stock-picking. Whether risk avoidance will work thus depends on the extent and type of market disruption.

Legal risk can also stem from litigation. The advent of attribution studies could provide the foundation for a wave of lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry. Studies that attribute extreme weather events to climate change are already commonplace and improving.77 Given the highly concentrated nature of the fossil fuel industry and supply side emissions, the question of legal liability becomes apparent. For example, Ekwurzel et al. have attempted to attribute responsibility for particular climate effects to particular companies.78 Already suits have been brought against major fossil fuel companies for damages caused by climate change in both New York City and California.79 Greenpeace has threatened similar action in the Netherlands against Royal Dutch Shell plc.80 In 2015 the Urgenda Foundation and 900 Dutch citizens won a case against the government of the Netherlands, forcing it to improve its emissions reductions efforts to fulfil its duty of care in protecting Dutch citizens from climate change (Urgenda Foundation v. The Netherlands [2015] HAZA C/09/00456689 (June 24, 2015)). The case was appealed, but upheld in 2018 (Aff’d (Oct. 9, 2018) (District Court of The Hague, and The Hague Court of Appeal (on appeal)).

The outcomes of such cases will be contingent on the jurisdiction and circumstances. The suit in New York City has already been dismissed, although this was because the judge deemed it to be under the purview of the Federal Court.81 Such cases can be expected to increase over time as the impacts of climate change worsen. Even if unsuccessful they can and often do cause reputational harm to companies and increase the chance of other investors withdrawing or diverting investment. Cases have also begun to be brought against investors, such as in Australia and the UK in recent years. Furthermore, if a company loses a lawsuit and fines are levied, the costs be passed on to investors via cuts to dividends and decreases in share prices.

There is a second risk: reputational. A company or investor’s image is increasingly important to their prospects. Alphabet Inc. was quick to withdraw from the US military contract of “Project Maven” once they faced a boycott from their employees. The Pentagon project aimed to develop algorithms to differentiate between objects and people based on big data from military drones. The threat of losing highly skilled, conscientious employees outweighed the money on offer from the Pentagon. One key historic example was a $5 million contract to produce napalm for use in the Vietnam War, “which most likely cost Dow Chemical billions of dollars” in “damaged reputations, recruiting problems and customer boycotts”.82 This ability to attract and retain consumers and employees has been included in “intangibles” accounting. Corporate executives know that financial incentives alone are not enough to recruit and retain skilled employees.83 One review of the literature suggests that a company’s image plays a role in prospective employees’ decision-making processes, that they prefer to work for corporations whose values overlap with their own, and that this affects long-term employee retention.84 Such considerations are particularly important for top talent.85 Being perceived as a funder of global risks and a questionable corporate citizen is a financial and recruitment liability.

In summary, the combination of legal and reputational risks makes aligning investments to minimise global risks a prudent choice for institutional investors.

2.2.3 Universal ownership theory

“Universal owners” are long-term asset owners such as pension funds or sovereign wealth funds that are invested in a broad (and more or less representative) swath of the economy.86 These universal owners have highly diversified portfolios that span different asset classes encompassing public and private debt and equity, physical assets, and more. Universal ownership theory supposes that an investor who is invested across a broad swath of the economy will have an interest in its overall health. Externalities from one sector could affect returns in another, especially in the long-term, which necessitates a more holistic approach.87 For example, high emissions in the fossil fuel sector could have negative consequences for returns in other asset classes. This includes physical effects on infrastructure, health effects due to pollution in cities and decreases in worker productivity. These factors could easily affect the long-term returns of other parts of a universal owner’s portfolio. If harm from one company or sector affects other companies or sectors within a universal owner’s portfolio, the owner has a strong interest in reducing that harm. For a universal owner, it would make sense to work to reduce the harms produced in the fossil fuel sector to protect the rest of the portfolio.

For the universal owner, who is by definition a long-term investor with a system-wide view, externalised outcomes are counterproductive. Trade-offs between and among companies and sectors need to be accounted for. As universal owners have an interest in the overall health of the economy, it is self-defeating for them to allow the companies it is invested in to contribute to global risks. Instead, they would be better advised to internalise the externality, and use their power through an investor campaign to change companies’ behaviour.88 Universal ownership theory thus provides strong theoretical grounds for a large subset of institutional investors to shift their finances away from contributing to global risk.

3. Are the motivations applicable to all Global Catastrophic Risks?

All of the outlined rationales are compelling, but not all are generalisable across all institutional investors or global risks. The two novel motivations we list (long-term institutional survival and universal ownership theory) are only applicable to particular types of institutional investor. That is, either those with an enshrined goal of perpetuity for the former, or a heavily diversified asset owner portfolio across a representative proportion of the economy for the latter. Arguments to reduce risk or maximise profit vary by issue. Divestment appears to have been a financially prudent move for fossil fuels, but not for tobacco. Similarly, legal, regulatory and financial risks will vary by country and market.

Ethical arguments appear to be universal across actors and risks. All global risks share the common “traits” of destroying vast amounts of future material and immaterial value. The potential for large-scale loss of human life makes investments in activities that contribute to these risks unethical. It is immoral to fund or profit from the endangerment of future generations. That ethos holds true regardless of the threat. Similarly, duties for institutional perpetuity do not depend on the hazard involved. There are no shareholders, churches or universities in a collapsed civilisation. These duties do not hinge on the nature of the specific risk, but rather its potential for causing future damage. Overall, institutional investors appear to have some core common ethical duties to reduce global risk, but whether they are legally bound to, or will profit from it, differs.

The different motivations also vary in terms of their effectiveness. Arguments for ethical action, the avoidance of reputational damage and regulatory risk have been persuasive in the case of both climate change and nuclear weapons. For example, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, Government Pension Fund Global, has excluded 16 companies involved in the production of nuclear weapons due to their potential to violate humanitarian principles.89 The Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF) cited both the moral tension between supporting the fight against climate change and investing in fossil fuels, as well as the fiscal responsibility to avoid stranded assets, as the basis for its decision to divest.90 There is abundant evidence on the efficacy of ethical shaming and stigmatisation tactics.91 This is evident in the proliferation of corporate watchdogs such as the Multinational Monitor, Corporate Watch and Global Exchange.

Redirecting institutional investment to maximise profit, avoid legal risk or meet legal obligations are motivations with more uncertain results. As noted, most legal cases related to fossil fuel divestment have been unsuccessful, while there is little evidence to suggest that diverting investments from globally risky activities will be profitable. Put simply, more time and evidence are needed to assess the profitability of a global risk-averse approach. The case for reducing global risks through investments to protect institutional perpetuity or broader economic stability (universal ownership theory) is even more unclear. These are novel motivations that have rarely been publicly advocated for. Some reasons are more compelling than others, yet none is entirely without grounds. The profit and non-profit basis for a global risk-averse investment strategy appears to be varied and sound.

PART 2 — Institutional Investors’ Tactics for Managing Global Risks

4. Analysis: Six tactics for investment campaigns

Investor campaigns typically employ six tactics: contest, protest, request, divest, re-invest and acquest. Each of these approaches has different strengths and weaknesses. In the following overview presented in Table 2, we describe these tactics and their aims. We focus on tactics relevant to institutional investors and financial redirection. These tactics run across the spectrum from least (contest) to most (acquest) confrontational. There is a long-standing debate on the relative effectiveness of more confrontational tactics: from shareholder activism to divestment.92 However, it seems that a range of tactics operating in tandem can work. The “inside game” can support the “outside game” and vice versa. Examples include tobacco, apartheid, landmines, cluster munitions and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in general).93

Table 2: The six tactics of investment campaigns.

|

Tactic |

Description |

Aim |

Conditions |

|

Contest |

Refers to shareholder activism by those with voting shares who aim to directly influence decision-making, involving a (group of) shareholder(s) with non-negligible holdings, using internal mechanisms to steer a company away from irresponsible, unethical or risky actions; includes both voting and co-filing resolutions and encompasses attempts to introduce independent monitoring and verification schemes to reinforce the desired behaviour. |

To shift a company from within through internal governance processes. |

The company must be capable of changing its behaviour, i.e. its business model cannot entirely dependent on the activity. There should be non-negligible holdings of voting shares, and the company’s terms of incorporation must allow for this form of influence. |

|

Protest |

Refers to shareholder activism by those with shareholdings who aim to lobby a company. For instance, by directly contacting senior executives or using Annual General Meetings (AGMs) for publicity and message amplification, involving a shareholder using their position to raise critiques and urge company transformation in annual general meetings.94 May be done by purchasing a single share. Protest also includes shareholder litigation. That is primarily derivative actions and other corporate-law-based instruments to hold executives responsible and liable by way of a suit in court against decisions that harm the (long-term) interests of shareholders. Both shareholder suits against the corporation and against individual executives are possible, both on behalf of an individual shareholder and on behalf of the corporation itself (i.e. derivative action). Even if such suits are not likely to be successful, their mere filing can attract public attention to management decisions that increase global risks. |

To cause a change to company behaviour or a loss of social licence from within by critiquing harmful activities in boardroom meetings and from outside by releasing this to the media or using shareholder litigation. Shareholder litigation can also shift company activities through the threat of regulatory, financial or reputational damage to the company or particular individuals. |

The company must be possible to change; negligible holdings may suffice. In the case of litigation the feasibility of a case will vary by jurisdiction and circumstances. |

|

Request |

Refers to shareholders and institutional investors directly appealing to government to introduce policies that reshape financial flows, impose standards or enact selective purchasing laws based on promoting their interests as investors. For example, at the 2018 Katowice climate summit, 420 investors managing over USD $32 trillion in investments called for stringent emissions reductions policies and improved climate-related financial reporting measures.95 |

To push governments towards policies causing investors to change asset allocation and businesses to change behaviour. |

An industry’s political power must be weak enough to allow for effective regulation, or the power of investors must be sufficient to overcome industry-imposed barriers to this. |

|

Divest |

Refers to shareholders freezing, reducing, or fully disposing of their holdings; this entails both the action of divesting by shareholders, as well external campaigns that urge divestment. |

To avoid risks, maximise returns, socially align one’s portfolio or cause the loss of social license. Within public equity the effect is indirect in that it is mainly due to public pressure; in other asset classes it can actually shift capital, and therefore can be more directly impactful. |

The company must be unable or unwilling to change; any prior holdings suffice. |

|

Reinvest |

Refers to positive investments in direct96 alternatives that are risk-reducing at a system-wide level. E.g. for climate change this would be renewable energy; as noted earlier, some positive alternatives can offer equivalent returns and reduced risk. |

To redirect capital from socially harmful or risky activities towards alternatives that directly alleviate these risks or damages. |

The previous company could not or would not change; or as standard practice. |

|

Acquest |

Buying up a company so that it comes under the direct control of an institutional investor. This can be done for the entirety of a company, or potentially just a portion of its shares, product lines or infrastructure. |

This is done with the intention of changing the company’s business model away from socially harmful activities, or shutting it down. |

The firm must be incapable of changing its behaviour and other tactics are not working; the investor must have financing to buy out the company. The legality of this tactic will vary by jurisdiction. |

Our list of six tactics can encompass numerous other approaches not explicitly listed here. For example, reinvestment could also involve the creation of new alternative financial institutions that invest in positive rather than risky activities.97

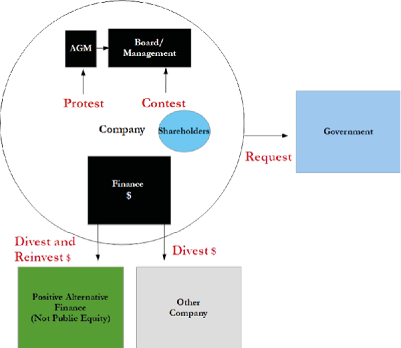

An overview of how these different tactics interact is provided in Figure 1. It shows that divestment and positive investment are two sides of the same coin. Contest and protest encourage companies to change their activities, while divestment frees up resources to be redirected towards positive alternatives (reinvestment). It also provides political pressure that can be translated into behavioural or policy change. Insofar as the social licence to operate has been undermined, request tactics will be more effective at enacting more forceful regulation.

Tactics can be combined throughout a campaign, moving from one to another in reaction to corporate lack of change. For example, the financial services company Legal and General Group Investment Management warned of its intention to divest from non-compliant companies two years prior to taking action. This gave targeted companies the opportunity to change their actions and align with the new standards. Thus, the move followed “protest” with “divest”. Further research could usefully address whether this was more effective than either tactic alone.

Fig. 1: An overview of investor campaign tactics.

There is a long-standing debate on the effectiveness of engagement compared to confrontation.98 We believe our typology offers a new angle on the “shareholder activism” versus “divestment” debate, by suggesting which tactics might be appropriate and successful in particular situations. We suggest that shareholder activism (i.e. contest and protest) is appropriate if such activism can reasonably be expected to change a company’s harmful activities within a reasonable time period (such as five years to a decade, depending on the urgency of the threat). However, if such activism cannot reasonably be expected to change the company’s activities over this time period, then “request”, “divest”, “reinvest” and even “acquest” are appropriate.

5. Timing of tactics: When to escalate

Whether or not it is reasonable to expect shareholder activism by a particular investor campaign to change a particular company’s activities is a difficult question. It will ultimately always be a subjective judgment call. However, some factors can inform this question of whether the company is able and willing to change. These include the centrality of the activity to the business model of the company, and the past behaviour of the company. These factors were identified in 11 interviews with people involved in investor campaigns, all conducted under the condition of anonymity.99 There are four main conditions to determine when to initiate or escalate shareholder activism. These are: ability to change, willingness to change, timing, and susceptibility to activism.

5.1 Ability to change

If a company’s business model is built on activities that create global risk, then there is little hope for it to change. Sometimes the risk-increasing line of business is not central, however. For example, many arms companies can do without nuclear weapons and LAWS contracts; these sources of income are not central to their business model. Large technology companies can very easily do without LAWS contracts. They already have significant profit margins and market capitalisation, and are not reliant on military clients. Some small or medium-sized fossil fuel-related companies, such as the power company Vattenfall AB, might be able to change their business model to become sustainable energy companies. In contrast, driving global warming appears to be irrevocably central to the model of most major fossil fuel companies. The sheer sunk costs in expertise, infrastructure, and assets developed to find and extract hydrocarbons is overwhelming.

5.2 Willingness to change

Is the company engaging with activism in good faith, or merely greenwashing? Both ability to change and past behaviour can be useful guides to this question. For example, fossil fuel companies have a long track record of misrepresenting science and funding “merchants of doubt”.100 They are currently spending billions lobbying the EU and US governments.101 The key metrics for willingness to change all relate to the question of where the company’s new financing is going: the percentage of capital expenditure, research and development spending, and acquisitions (and disposals) spending dedicated to changing course away from Global Catastrophic Risks;102 thus far none of the oil and gas majors are on track to shift their business models according to these metrics. Combined with their structural inability to change, this provides a strong case that the fossil fuel industry is also simply unwilling to change.

5.3 Timing

How long has there been a shareholder activism campaign and are there signs it is working? There is no clear rule or threshold here. It will partly depend on indicators of progress and how urgent the risk being addressed is. If an insider campaign has been ongoing for multiple years without any clear victories, it is likely time to escalate.

5.4 Susceptibility to activism

How likely is a company to be influenced by shareholder activism? Consumer-facing companies may be more susceptible, especially if their consumers are ethically conscious shoppers. Companies that are more reliant on highly skilled, well-organised workers in short supply may be more susceptible as well.103 Companies with a corporate culture of, and management incentive structures for, being agile, disruptive and high growth rather than complacent and defensive may be more susceptible. Ownership and management structure are also important. Companies with an individual majority owner, such as founder-dominated technology companies, can move fast if that individual is persuaded.

These are partly empirical questions, but the final decisions are ultimately subjective judgements. There are also practical considerations, such as the potential speed of divestment, impending regulation and public opportunities to garner attention. If a company is unwilling to change, and simply incapable of doing so, then it would be prudent to turn to divestment and reinvestment. If possible, it may even be wise to consider the tactic of acquest.

6. Effectiveness: When do investor campaigns work?

Investor campaigns of the kind described above will not always be effective. As we will substantiate below, evidence from practice and the literature suggests that investor campaigns work best under the following four conditions: the presence of clearly identifiable, intentional moral villains (actors that plausibly contribute to global risk) to target, existing alternative models of best practice, the presence of a well-organised and well-resourced campaign, and private investors who have substantial leverage over the actors. We term this the “Villain-Hero-Campaign-Leverage” (VHCL) framework.

6.1 Intentional “villains”

Political messages inevitably need to be less nuanced than those reflecting the full complexity of the real world. Experience has shown that the presence and visibility of moral villains acting with intention makes ethical arguments salient and political tactics psychologically effective. The use of a simplified narrative and opposing heroes and villains is a central element of investor campaigns. Benford and Hunt contend that “social movements can be described as dramas in which protagonists and antagonists compete to affect audiences”.104 To be effective, framing by movements needs both “heroes” and “villains”.105 For example, a compelling narrative framing has been shown to be more effective in the communication of climate change.106 The necessity of having a bad actor with intention for a campaign to target is evident in the success of previous campaigns. For example, the Fossil Free divestment movement directly labels the fossil fuel industry as the enemy. The Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign focuses on arms companies, and highlights the emotionally salient hibaku-sha victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The apartheid divestment campaign had a ready-made villain in the discriminatory South African government, while anti-smoking activists focus on shaming Big Tobacco. The ability to portray a salient villain with intention allows an investment campaign to construct a persuasive narrative.

6.2 Reinvestment heroes

A successful framing should also include “heroes”: actors that are working for the societal good to mitigate global risks. Empirical evidence underlines the unique importance of a hero. Jones used an internet experiment with 1,500 US citizens to explore how different considerations shape individual risk and policy preferences for climate change.107 He found that narrative framing, particularly the presence of a compelling hero, was the greatest shaper of individual views on climate risks and policy. Investment campaigns ideally pinpoint a clear alternative that mitigates the targeted risk or harm. To change corporate behaviour through the tactics of contest and protest, it is best to have a clear “ask” and proposed model of best practice. The tactic of reinvesting needs a “hero” for reinvestment; having such a hero can improve the efficacy of the tactic of divestment. In the case of climate change, investments in fossil fuels can be reallocated to renewable energy projects (as long as these are primary market investments — not public equity). This could happen within a given energy company, but mostly the Fossil Free movement has employed a frame of shifting money from the “bad actors” (the fossil fuel industry) to good ones (the renewable energy industry). These heroes are the final destination of funds mobilised for positive investment. However, this is not a necessity. Nuclear weapons do not have a clear, profitable mitigating alternative, yet ICAN’s Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign has operated successfully regardless.108 Nuclear weapons producers have been excluded from a USD $1,537 billion asset pool as both the Norwegian Government Pension Fund, ABP (the world’s fifth-largest pension fund) and 22 other institutions have enacted comprehensive bans on investing in nuclear weapons. This progress has been underpinned by both the continued activism of ICAN, as well as the symbolic power of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.109

6.3 A well-organised and -resourced campaign

Effective action by institutional investors tends to be underpinned by a well-organised and -resourced campaign.110 High-profile shareholder activism organisations include As You Sow, Majority Action, and the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility. For fossil fuel divestment the most well-known campaign is the Fossil Free movement centred around 350.org, while for nuclear disarmament it is the Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign. Such campaigns can help to publicly and forcefully express the rationale for divestment campaigns,111 coordinate a variety of disparate investors and lower the start-up costs (including in terms of risk and transaction costs) for first-movers.112 These first-movers help to promulgate a new standard across the community that becomes legitimised over time.

6.4 Investor leverage

These six tactics are most useful when deciding about investments in the primary market — private equity, venture capital, bond issuances, infrastructure, private real estate and public equity investments at the Initial Public Offering (IPO) stage.113 Within the primary market shareholders have the greatest influence over company behaviour, and divestment decisions are more likely to have an impact on the liquidity, cost and availability of new capital, and profits of a corporation or industry. These tactics can also be applied to some extent to publicly traded companies, where different divestment and engagement strategies can still play important public relations roles.

7. Can investment campaign tactics work for global risk prevention?

In this section we examine how the six tactics of investor campaigns can be applied to four other global risks (in addition to climate change and nuclear war) stemming from biotechnology, LAWS, advanced AI systems and asteroid strikes.114 Biotechnology, LAWS and advanced AI systems are capable of increasing global risks in the coming decades. Asteroid strikes are a naturally occurring risk that has never been viewed from the lens of institutional investment but that we include as representative of natural risks in general.

We review each of these risks according to the four conditions outlined in our framework above: the ability to identify and portray a clear villain with intention, direct (heroic) alternatives, the presence of a campaign, and investor leverage over the problem. Our findings are summarised in Table 3. This includes a comparison against the two global risks that are currently the target of divestment campaigns: climate change and nuclear weapons.

Table 3: Estimating the suitability of investment campaign tactics to mitigate global risks.115

|

Hazard |

Presence of an Investment Campaign |

An Easily Identified Salient Villain |

Heroes for Reinvestment |

Investor Leverage |

|

Climate change |

Yes |

High |

High |

High |

|

Yes |

High |

Low |

Medium |

|

|

Biotechnology |

No |

Mixed |

Yes |

Medium |

|

LAWs |

No |

Yes |

No |

High |

|

No |

Mixed |

Mixed |

Medium |

|

|

No |

Low |

Low-medium |

Low |

7.1 Biotechnology

Biotechnological risks are unprecedented anthropogenic risks. They range from intentionally created weapons through to accidentally birthed pathogens. One risk from emerging technologies is an engineered pandemic. Bioengineering could provide the means for creating a pathogen that is more virulent and deadly than any found in nature. Such a disease could be released through “error or terror” and cause mass fatalities and economic damage.116 The threat is not speculative. One postdoctoral researcher was almost single-handedly able to produce a complete synthesis of a horsepox virus — similar to smallpox, which killed 300 million people in the 20th Century — in only six months.117 There is a small but significant chance that these risks could be global and catastrophic.118

While representing only a small part of the overall risk, there are some identifiable “villains” in this field. Over the course of the 20th century, 23 states “had, probably had, or possibly had” a biological weapons program, although only those of the Soviet Union and the United States developed significant119 capabilities”.120 Non-state groups such as Aum Shinrikyo or Al-Qaeda have also sought to develop biological weapons.121 These terrorist groups, and the Soviets who violated the Biological Weapons Convention for years after signing it, can fairly be called “villains”. In many other cases, risks were created despite good intentions and would only create harm due to an accidental release. For example, in 2011 several research groups produced a strain of H1N1 avian flu that was potentially transmissible between humans.122 These “gain-of-function” experiments to create potential pandemic pathogens (PPP) have attracted controversy.123 These researchers are not “moral villains”. Such research is often aimed at reducing biological threats by better understanding their nature. While there are state and non-state actors looking to use biotechnology to create weapons for the sole purpose of inflicting damage, other threats are born accidentally from well-meaning research. Given this, we rate the presence of a plausible moral “villain” as mixed.

The leverage of institutional investors is often low due to the prevalence of government-funded weapons programs, academic or government-led research and terrorist activities. However, companies appear to be playing an increasing role in biotechnology. For example, the International Gene Synthesis Consortium (IGSC) is an industry-led group of gene synthesis companies and organisations formed to design and apply a common protocol to screen both the sequences of synthetic gene orders and the customers who place them. They represent approximately 80% of commercial gene synthesis capacity worldwide. The centrality of such industry research in potentially risky areas could make investor campaigns an increasingly useful tool in the future.124 Given this we score the current state of investor leverage as “mixed”.

There are clear risk-mitigating alternatives (or “heroes for reinvestment”) in the private sector. These include companies supporting better health surveillance, pandemic preparedness initiatives and vaccination production facilities. There is not yet a campaign on this issue. Thus, we rate biotechnology as “mixed” for the presence of a villain with intention, “yes” for the presence of a clear alternative, “no” for a current campaign, “high” for tangibility of assets and “medium” for investor leverage. If companies become a more important player in the future and are engaged in risky behaviour, then an investor campaign might well be appropriate and successful.

7.2 Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs)

LAWs are weapons systems capable of autonomously identifying, selecting, and killing targets without meaningful human intervention or control.125 They are a near-term technological development and could pose a threat within the next decade. Robotic systems with limited autonomy already exist and are regularly deployed in combat, including the Phalanx Close-In Weapon System and anti-tank and personnel mines.126 In 2017, 49 deployed systems (from an analysis of 154 systems with automated targeting) could detect possible targets and attack them without human intervention.127 An open letter signed by over 3,700 AI and robotics researchers and over 20,000 others claimed that cheaply mass-produced LAWs would be the “Kalashnikovs of tomorrow”.128 That is, ubiquitous on battlefields and easily accessed by terrorist groups. The development, stockpiling and/or use of LAWS could change the cost and speed of wars, and therefore destabilise the global order and/or spark escalating arms races. Moreover, they could empower dictatorships with a new form of brutal control and terrorists with a potent, cheap, and mobile weapon.129 Finally, their vulnerability to unexpected interactions could lead to “flash war”, analogous to “flash crashes” in the stock market.130

Investor campaigns have some potential to help shift finance away from LAWs, but with several caveats. The presence of a moral villain with intention is “mixed”. The private sector is a key part of the emerging regime around LAWS.131 However, currently there is no definitive list of which companies are involved in the development of LAWs. Three groups are likely to be relevant, which vary in the extent to which they can be portrayed as intentional villains. First are the major defence companies such as Lockheed-Martin, Boeing and BAE Systems. These are also companies that are heavily implicated in the production of nuclear weapons and are thus target companies of the Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign.132 A second group is technology companies that provide support to these defense companies, either through “translational” work applying AI breakthroughs to a particular military application or through the provision of data storage and computational processing power. For example, Google was involved with Project Maven, a drone AI-imaging program, and had initially bid for the “JEDI” cloud computing contract, both for the Pentagon. Neither was directly tied to LAWS, but are indicative of “applied” work. Third, many of the technologies necessary to create such systems are being produced by technology conglomerates who have no clear incentive to aid the deployment of LAWs. For example, the co-founders of Deepmind (Shane Legg and Demis Hassabis) and a co-founder of OpenAI (Elon Musk) have all signed the pledge on LAWs. Regardless, the AI technologies their companies develop could still enable the weapons they abhor. However, there are also actors contributing to global risk in companies that are directly working on LAWs through military contracts. We thus rate this as a “yes” for the presence of a plausible “villain”.

The “hero” for best practice or reinvestment would be AI companies that are not involved with R&D into LAWS. This is not, however, a direct mitigating alternative. Preventative responses are unlikely to be profitable or appealing to institutional investors. Thus, we rate this criterion as “mixed”.

Concerns around LAWS have led to calls for a ban on LAWs; the creation of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, now supported by 93 non-governmental organisations and 53 countries;133 United Nations negotiations under the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons; and a widely-signed pledge by companies, individuals and universities not to participate in the manufacture, use or trade of LAWs.134 Moreover, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global is examining whether companies that contribute to the development of LAWs would be violating fundamental humanitarian norms in doing so.135 Despite these developments, LAWs have not yet been subject to an investor campaign. However, an investor campaign could draw on the efforts described above, several of the advocates of which have extensive experience with previous arms-control campaigns that included investment tactics.136

Investors have significant potential leverage over LAWs. Most defence companies are publicly traded companies in which a few key funds hold significant shares. For example, the five largest holders of shares in Lockheed Martin (State Street Corporation, Capital World Investors, Vanguard Group, BlackRock Inc., and The Bank of America Corporation) cover over a third (41.08%) of total holdings. Together they have substantial leverage over Lockheed’s future with LAWs.

At first one might think that investors do not have leverage over technology companies, as they often concentrate voting power in the hands of the founders. However, these same founders have shown themselves to be reactive to public pressure. Investors that engage in contest, protest and request-based tactics are likely to increase leverage. Major technology companies are publicly listed and institutional investors hold significant shares and therefore enjoy some influence. Most tech giants have highly valuable employees who are mindful of ethical challenges and have actively boycotted company activities they disagree with.137 This was the case when Google decided not to renew its contract with the Pentagon on Project Maven and to withdraw its “JEDI” bid due to employee pushback.138

Moreover, Silicon Valley corporates have proven susceptible to shifts in public opinion. In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook deployed a suite of responses including public apologies, full-page advertisements in the US and UK to reassure users, a historical audit of data-using apps, and reforms to the accessibility of privacy and security settings.139 In 2010 Google withdrew from the Chinese market amid public criticism for enabling and legitimising an oppressive regime. A second attempt to launch a censored search engine in China was scuttled in 2018 due to harsh rebukes from free internet advocates, US lawmakers and humanitarian advocates.140 Together, these factors suggest that AI companies may be susceptible to pressure exerted by institutional investors as well as employees, who are often shareholders themselves.

Accordingly, we rate LAWs as “mixed” for the presence of a villain with intention, “mixed” for the presence of a clear alternative, “no” for the presence of a current campaign, and “high” for investor leverage. If particular companies are clearly involved in the development of LAWS, an investor campaign might well be appropriate and successful.

7.3 Advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems

As AI systems become more powerful, and as our societies become more reliant on them, the risks we face will also increase. The field of AI is advancing rapidly,141 but there is uncertainty about the speed of future progress.142 Yet even existing systems have raised multiple concerns around issues such as labour automation, algorithmic bias and privacy intrusions. Longer-term fears include the reinforcement of authoritarian regimes,143 new physical, political and cybersecurity concerns,144 an arms race,145 a destabilisation of the global geopolitical order,146 or even a failure of nuclear deterrence AI systems.147 Even well-designed systems could trigger these accidents due to their sheer complexity and tightly coupled nature.148