19. The Cartography of Global Catastrophic Governance

© 2024 Catherine Rhodes and Luke Kemp, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0360.19

Highlights:

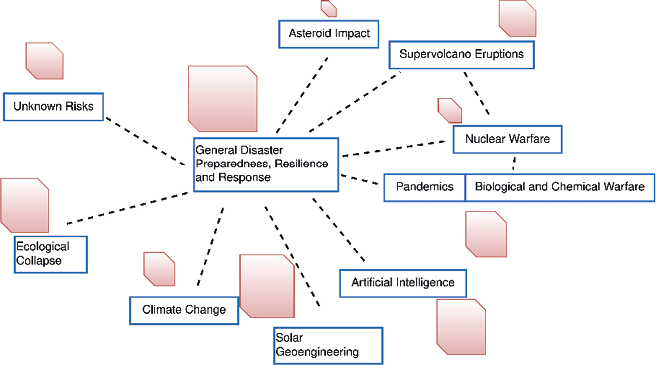

- This chapter provides an overview of the fragmented and insufficient international governance arrangement for GCR hazards and drivers.

- It finds that despite clusters of dedicated regulation and action — including in nuclear, chemical, and biological warfare, climate change, and pandemics — their effectiveness is often questionable.

- In other areas, such as catastrophic uses of AI, asteroid impacts, solar geoengineering, unknown risks, super-volcanic eruptions, inequality and many areas of ecological collapse, the legal landscape is littered more with gaps than effective policy.

- The authors suggest five steps to help advance the state of GCR governance: 1) identifying instruments and policies that can address multiple risks and drivers; 2) researching the relationship between drivers and hazards to create a deeper understanding of “civilisational boundaries”; 3) exploring the potential for “tail risk treaties” that swiftly ramp-up action in the face of early warning signals of catastrophic change; 4) examining the coordination and conflict between different GCR governance areas; and 5) building the foresight and coordination capacities of the UN for GCR.

- These recommendations can ensure that international governance navigates the turbulent waters of the 21st century, without blindly sailing into the storm.

This chapter was written by CSER researchers for the Global Challenges Foundation and provides an overview of existing governance frameworks. For a proposal on how to improve the global governance of nuclear weapons, see Chapter 20. For a methodological framework that can help identify the early warning signals required to make anticipatory governance like tail risk treaties work, see Chapter 17.

1. Introduction

On January 24th 2019, the fingers on the Doomsday Clock did not move: they stayed pressed ominously at two minutes to midnight. The clock has been the most captivating attempt to forecast the likelihood of a Global Catastrophic Risk (GCR). It is inherently limited, focusing only on a subset of GCRs: nuclear weapons, climate change and more recently epistemic security. It also does not reflect the governance of different global risks. Understanding how humanity is currently responding to GCRs is fundamental in comprehending how precarious or resilient the world is to calamity.

While Global Catastrophic Risks are becoming increasingly widely known, their governance is understudied. Only a handful of studies have examined whether existing international law arrangements,1 or the UN,2 are fit for addressing existential or Global Catastrophic Risks. Others have attempted to look at the capability of the UN to prevent new risks in an age of AI and converging, powerful technologies.3 These studies have relied on more of a cursory overview of governance, focusing on broad structures and scenario analysis. They have not systematically examined coverage of different hazards and vulnerabilities.

Our report seeks to overcome these limitations by providing the most far-reaching and comprehensive mapping of the governance of Global Catastrophic Risks, including both hazards and vulnerabilities. Our definition of GCRs and existential risks is provided below in Table 1. While our report will focus on GCRs broadly, many of the assessed issues are plausible of becoming existential risks as well.

Table 1: Definitions of GCRs and existential risks.

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Existential risk |

Any risk that has plausible pathways to cause either human extinction or the drastic and permanent curtailment of societal progress.4 A global collapse could be considered as a lower bound for this, given the uncertainty of how it would unfold in the presence of weapons of mass destruction.5 |

|

Global Catastrophic Risk |

Any risk that plausibly leads to the loss of 10% or more of global population.6 |

Our Cartography of GCRs demonstrates that several GCR hazards (climate change, nuclear weapons) are covered by international law but usually inadequately. That is, the institutions often lack clear enforcement and compliance mechanisms, and have largely failed to address the underlying collective action problem. Other issues, such as solar geoengineering, catastrophic uses of AI, inequality and some areas of ecological collapse (phosphorous, nitrogen and atmospheric aerosols), are either largely or completely neglected. The governance across GCRs is fragmented, with fractured membership and mandates both within and across different hazards and vulnerabilities. There is no central body empowered to coordinate responses to GCRs nor to foresee them.

2. Approach

In order to achieve a comprehensive overview of global governance arrangements for GCRs it is important to adopt a broad conception of global governance, because otherwise key components may be overlooked, and indications of emergent activity may not be apparent.

A core focus of research and practice in global governance — which is also reflected in this report — justifiably remains the actions of states through international (intergovernmental) organisations and international legal instruments. A report that only focused on these components would, however, present an incomplete picture: a range of other intergovernmental governance activities can contribute to addressing GCRs; and there are relevant activities outside the intergovernmental space. For some GCR areas, the latter currently dominate global governance arrangements.

The significance of different components varies between GCR regimes. This means that the construction of maps and attention paid to different components varies too, but we have also aimed for a level of consistency in presentation. For example: we cover bilateral agreements more extensively in nuclear warfare than in other areas because of their high significance in managing global nuclear risk; we cover multilateral expert communities extensively in the Asteroid Impact and Super-Volcanic Eruption areas, because these are more heavily relied upon there.

It is worth making a general observation about the increasing range of issues that need to be addressed through global governance and the challenges this presents:

- Formal intergovernmental governance activities are generally poorly resourced already; their capacity to take on additional tasks and remain responsive to new threats is limited, and some are already overstretched.

- Proliferation of global governance activities can disadvantage less well-resourced states, which can struggle to participate in a large number of international forums and processes, representativeness in which is already sub-optimal.

- Increased complexity generally makes governance arrangements more difficult to navigate (one of the reasons mapping work is useful) and increases the transaction costs associated with international cooperation, the likelihood of conflicts and contradictions between rules, and duplication of effort.

Given the extent and complexity of many of the regimes covered in this report, we have separated some more detailed information into Appendix I. Appendix II provides a list of acronyms. These appendices are available online.

In the report itself, we provide maps and summary information for individual hazards in global GCR governance.

These generally follow the GCR categories from GCF’s Global Catastrophic Risks 2018 Report. The areas of “Biological and Chemical Warfare” and “Pandemics” have been combined, because there are significant overlaps in the global governance activities across these areas that are best illustrated by handling them together. We have also designated “Ecological Collapse” as a driver of GCR, rather than a hazard. Otherwise we have consistently applied the categorisation of the 2018 report.7

The mapping of each of these areas is intended to be representative but not exhaustive. We instead provide an overview of key treaties and governance efforts and characterise these as a regime complex: a constellation of institutions addressing the same international issue.8 We provide information about the gaps and issues requiring attention in each regime at the end of each hazard section. We also deliver a high-level view of broader GRC governance arrangements under the UN and transnational (networks of non-state actors) actions.

We end with a summary assessment of GCR governance arrangements and identification of (priority) lines of research and practical action that could advance the governance of individual GCRs and GCRs collectively.

3. Regime Complexes for Hazards

Hazards are direct threats that could cause global calamity. We draw on both previous GCR reports, as well as consultations with our colleagues to produce the following list of relevant hazards: AI; Asteroid Impact; Pandemics, Biological and Chemical Warfare; Climate Change; Solar Geoengineering; Unknown Risks; Nuclear Warfare, and Super-Volcanic Eruptions. We provide a high-level summary of the governance arrangements of each of these hazards before concluding with an analysis of their effectiveness and gaps.

3.1 AI

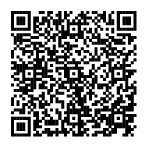

Fig. 1: Catastrophic AI regime complex.

Within the rising age of AI are hidden disastrous developments. There is an open debate over whether AI systems as a class can be regulated. This is because AI is a set of techniques and sub-disciplines rather than a single, specific technology.9 However, there are certain, specific forms of AI systems and end uses which could constitute a GCR. These form a discernible, governable cluster. These include:

- AI-enabled cyberwarfare;

- The creation of a misaligned or misused “High Level Machine Intelligence” (HLMI): a generalised AI system that is roughly equivalent to a human in its cognitive capabilities;

- Lethal autonomous weapons.

Cyberwarfare has essentially no governance at the international stage. There are two minor exceptions. First, is the Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare. The Tallinn Manual has only been endorsed by NATO member states and provides non-binding advice on the application of international law to cyberspace. Second, is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s “Information Security Agreement”. This has only six member states and failed to garner sufficient approval from the UN General Assembly. The absence of effective regulation and the proliferation of threats has led some to call for a Cyberwar Convention.10 Negotiations for such a body have not begun and are not on the horizon.

LAWs could potentially be covered under the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. The Convention has a mechanism — its Additional Protocols — to expand its coverage to new categories of weapons (such as blinding lasers or land mines). However, in practice, negotiations to include LAWs under its remit have been marked by disinterest from great powers. It has yet to yield any success and appears unlikely to do so in the foreseeable future. If it did, the Convention has no ability to enforce its decisions. In the absence of effective international law, civil society has stepped forward in the form of the active Campaign to Stop Killer Robots.

The development of HLMI is ungoverned. It is the most neglected area of international AI law.11 In the absence of explicit regulation, both corporate self-governance and expert community action have filled the void. Many of the firms and bodies creating HLMI are actively engaged in safety work. One 2017 survey of 45 HLMI projects across 30 countries and six continents found that only 15 were directly involved in AI safety research.12 Many of these are directly connected to academic and civil society groups working directly on AI technical safety or AI governance. Bodies such as CSER and AI Gov (under the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University) are all actively engaged with prominent HLMI developers such as Deep Mind (part of Google) and OpenAI.

There is also no consensus on the governing principles for AI systems. The work of both these expert communities and others has spawned a plethora of AI principles. Most of these encapsulate some common, ambiguous concepts: use of AI for the common good; avoiding harm and the infringement of rights; and privacy, fairness and autonomy. No clear set of principles reigns supreme, and several tensions exist across them.13 It is unclear how directly or effectively any of these is for catastrophic AI applications specifically.

There are also several bodies that have some relevance to AI systems but no direct mandate over them. The ITU has been admirably active in promoting AI dialogue through hosting annual “AI for Global Good Summits” since 2017. Yet the ITU is currently limited to regulating telecommunication systems, such as radio infrastructure; efforts to expand its role in internet governance have been resisted. There are legal arguments that its mandate could extend over many AI systems, but this seems politically unlikely to happen. Similarly, the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) has established a committee to discuss a programme on AI standards, but would have no mandate to address the identified AI problems on its own.

Alongside these bodies is a raft of regulations, working groups and decisions under other fora. Action across the IMO, ICAO, ITU, and other bodies, as well as treaty amendments, such as the updating of the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic to encompass autonomous vehicles, are indicative of this.14 Most recently, France and Canada have jointly led an initiative to establish a ‘International Panel on AI’ under the OECD. This proliferating panoply of AI governance shows some signs of self-organising. The UN System Chief Executives Board (CEB) for Coordination through the High-Level Committee on Programmes has been empowered to draft a system-wide AI engagement strategy. Whether such coordination will be successful is unclear. Moreover, this swell of governance does not capture the catastrophic uses cyberwar, LAWs and HLMI.

Table 2: Coverage and gaps in HLMI governance.

3.2 Asteroid impact

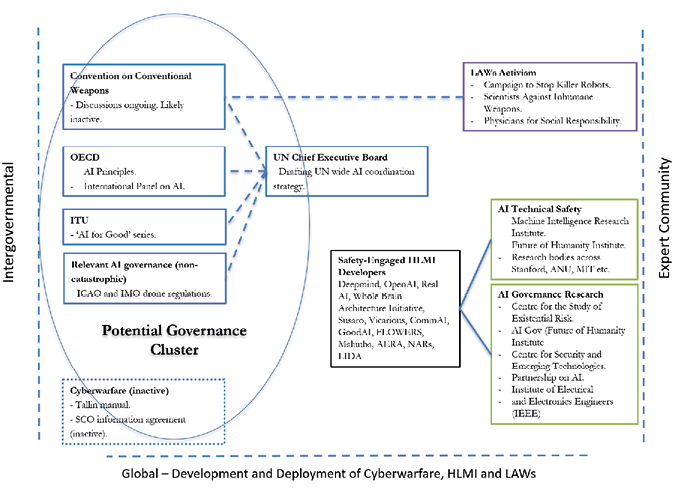

Fig. 2: Asteroid impact regime complex.

Compared to most other GCRs, global governance for asteroid impacts is minimal, and not particularly complex. There is a reasonable quality of coverage for the more technical aspects of identification, monitoring, evaluation, and early warning, as well as coordination and promotion of research, development and testing of deflection techniques. (Broadly, all of those activities focus on prevention.) There is some coordination of planning around communication, for scenarios in which a “credible impact threat” is identified, and some connections with civil defence communities (for example, as part of the response activities of the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group).

Participants in these governance arrangements understand the seriousness of the threat, particularly where an NEO would be large enough to directly cause a global cooling effect (>1km), and an understanding that smaller NEOs (in the 140m-1km range) could indirectly have global catastrophic impacts as well as being locally catastrophic. There is clear hope that there will be sufficient warning time in advance of a significant Earth impact to boost resilience efforts; however, there is limited extension of the NEO-specific governance arrangements to address preparedness and response. Mostly this will depend on more general global governance arrangements for disaster preparedness and response (see Section 5). Notably, the severe impacts that would need to be prepared for and responded to — those associated with the effects of global cooling and damage to critical infrastructure) will be very similar to those caused by some other GCRs, such as super-volcanic eruptions (Section 3.8) and nuclear winter scenarios (Section 3.7).

While the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) and Office on Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) are at the core of global governance of asteroid impacts, most of the governance efforts are undertaken by scientific and technical experts in national space agencies, research institutions, and through individual contributions. Some national (particularly NASA-funded) and regional (e.g. the EU’s NEOShield 2 Project) efforts have particular significance.

The activities of these other groups connect back to COPUOS and strongly emphasise openness, sharing of data and analysis, and collaborative efforts. This arrangement seems to function well for addressing the technical and prevention aspects of asteroid impact governance; however, attention is needed for sustainability and continuity should, for example, a major partner withdraw. (Ensuring continuity has, for example, motivated the establishment of the UNOOSA as a permanent secretariat for the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group.)

Issues around representativeness and equity might in future arise in this governance area, but — currently at least — this seems much less problematic than in other GCR governance areas (such as pandemics), particularly when focusing on the technical and preventative aspects. For representativeness, while the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group, for example, requires the ability to contribute to space missions for participation, and is therefore oriented towards states with space agencies, COPUOS is open to all UN member states (92 are currently members of the Committee) and its recommendations go to the UN General Assembly for discussion and approval. Thus, all UN member states have an opportunity to engage with its work.

For equity, core principles of space law — benefit to humanity and non-appropriation — are established across this governance regime and appear to have broad acceptance and strong normative force. COPUOS has programmes relating to capacity building in space law and for application of space technologies for development goals and during disasters.

It is expected that technological advances will enable mining of NEOs for resources at some point in the future, most likely for use in outer space rather than return to Earth. If this area is substantially financed and/or operated by commercial enterprises, then the practicalities of benefit-sharing will need further consideration. COPUOS will be an appropriate forum for such discussion. COPUOS is also an appropriate point for connection with institutions in the general disaster preparedness and response areas of global GCR governance. The International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) is currently working on definitions and terminology for NEOs, and this will include definition of NEO as a natural hazard to feed into the UN Office on Disaster Risk Reduction’s updated glossary of natural hazards.15

Table 3: Coverage and gaps in asteroid impact prevention and preparedness.

|

Coverage |

There is a good level of coverage for: identification, observation, monitoring, analysis and evaluation, communication, and preventative response. It is limited for: impact preparedness, resilience and response — quality of coverage of these areas will therefore largely depend on general disaster preparedness and response efforts. |

|

Gaps |

These are likely to be found in the general disaster preparedness and response efforts. |

|

Issues Requiring Attention |

Sustainability and continuity (particularly of non-intergovernmental arrangements). Increasing representativeness and engagement. Increasing role of commercial enterprises. |

3.3 Pandemics, biological and chemical warfare

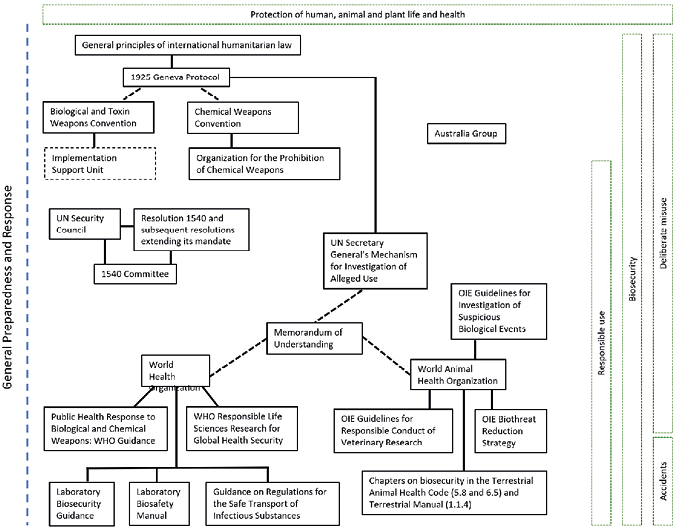

Fig. 3: Pandemics, biological and chemical warfare regime Complex I.

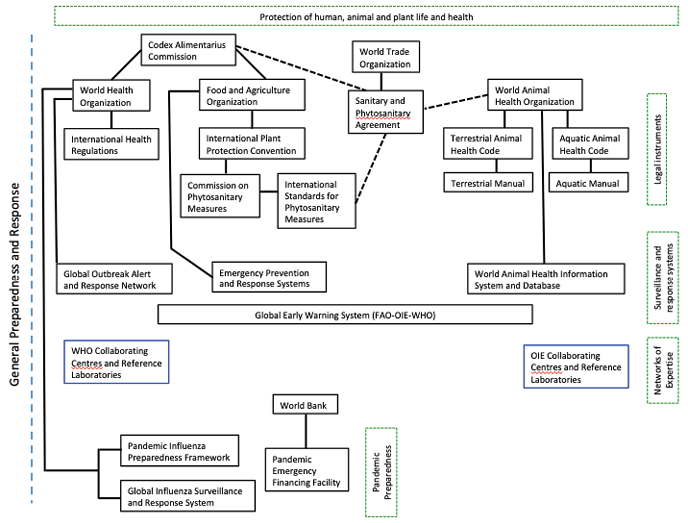

Fig. 4: Pandemics, biological and chemical warfare regime Complex II.

In this summary we combine consideration of global governance of biological and chemical warfare and pandemics, because there are significant areas of overlap between the governance arrangements for these two areas, which might not be fully apparent when addressing them separately.

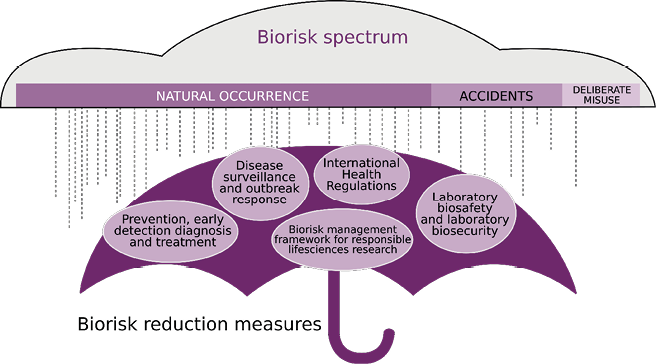

The range of biological risks addressed by global governance is illustrated by the World Health Organization’s “biorisk spectrum”:

Fig. 5: The biorisk spectrum and biorisk reduction measures.16

To this, it is worth adding two further categories to the spectrum: “human-induced” lies between natural occurrence and accidents, and would for example cover anti-microbial resistance as a threat that is “natural” but driven primarily by human action, and might also cover e.g. shifts in geographical range of disease vectors driven by climate change; and “deliberate action with benign intent but unintended consequences” which would sit between accidents and deliberate misuse. This might, for example, relate to release of a biological control agent into the environment without understanding its consequences for health. While this particular image focuses on human health (as the responsibility of the WHO), there are Global Catastrophic Biological Risks associated with threats to animal and plant health, and to ecosystems — particularly where these would severely impact food safety and security and key ecosystem services.

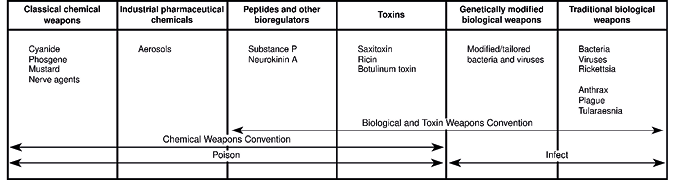

Another risk spectrum to be aware of is that which extends across biological and chemical warfare:

Fig. 6: The comprehensive prohibition of the chemical weapons convention and the biological and toxin weapons convention.17

This illustrates the areas of overlapping coverage between the two conventions. While there are now separate conventions for biological and chemical weapons, they were initially addressed together in international governance, and there remain significant connections between the two regimes. The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibits use of biological and chemical agents in war. It still has relevance because the prohibition on development, production, stockpiling, acquisition and retention in the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) extends to use through reference to the Geneva Protocol, and because the Protocol is accepted as part of customary international law applicable to all states whether or not they are party to the conventions.

The BTWC and Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) utilise general purpose criteria prohibiting use of biology and chemistry for non-peaceful purposes. States parties to the conventions have repeatedly emphasised that they are applicable to all scientific and technological advances in relevant fields. Both conventions include provisions promoting peaceful applications — for the BTWC “prevention of disease” is specifically mentioned in this regard, and this is one way in which they connect with other areas of governance of biological risks.

The long-standing international norms against biological and chemical weapons have experienced some challenges, but while there is some concern around potential erosion, these remain strong at present and are central to global governance efforts. There are also some well-recognised areas of weakness in the conventions. The CWC’s provisions relating to the permitted use of some toxic chemicals for law enforcement purposes, has resulted in some ambiguities and divergent interpretations — for example, about development and use of riot control agents and incapacitants.18 The CWC is overseen by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which has around 500 staff and an annual budget of around €70 million. One of its core roles is verification activities, which are structured around inspection regimes. The BTWC does not have an associated international organisation, and is instead supported by a small Implementation Support Unit of three staff. It also has no verification regime (attempts to negotiate one failed in the early 2000s and are yet to be re-established). This is a significant weakness given the dual-use nature of biological facilities, equipment, materials and research. Both conventions cover areas of rapid scientific and technological advance and their effective implementation by states parties needs to be informed by a good understanding of the risks and opportunities associated with such advances. The OPCW has a Science Advisory Board that undertakes some of this work in regard to the CWC. This is, however, another area in which the BTWC has extremely limited capacity. Civil society groups such as research institutions and science academies undertake efforts in support of science and technology review for the conventions. These efforts are important, but can lack some of the legitimacy of formal processes.

Other international governance relevant to deliberate misuse includes: UN Security Council Resolution 1540(2004), which addresses potential proliferation of biological, chemical and nuclear weapons to non-state actors, and subsequent resolutions which extended its mandate,19 and the associated 1540 Committee, which reports to the Security Council on its implementation; and the UN Secretary General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons.

The OPCW and ISU undertake some activities to support assistance in case of a biological or chemical weapons attack, including through facilitation of requests and offers by their states’ parties. OPCW has also produced a Practical Guide for Medical Management of Chemical Warfare Casualties, directed to medical responders, and the WHO also provides relevant advice, including in its Public Health Response to Biological and Chemical Weapons guidance.

There are two other key overlapping areas with broader global governance of biological risks. First, measures for laboratory biosafety and biosecurity, and safety during transport of infectious materials, which form part of the work of the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Animal Health Organization (OIE) contribute to the safeguarding of biological materials that might be misused. Secondly, the systems for surveillance, preparedness and response to disease events overseen by the WHO, OIE and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) will play a key role in detection and response to any deliberate disease outbreaks or chemical attacks. OIE and WHO both have memorandums of understanding around provision of technical support with the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use.

FAO, OIE and WHO also play important roles in prevention and response to accidental releases of biological agents, toxins and hazardous chemicals, including specific guidance on safety in laboratories and during transport.20 Their general surveillance, preparedness and response systems will play a key role in detection and response to any outbreaks resulting from accidents or deliberate releases with benign intent but unintended consequences. Provisions of the Convention on Biodiversity and its Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety may also have relevance where damage to health or the environment stems from transboundary movements of living modified organisms.

WHO and OIE have also produced some guidance (Responsible Life Sciences Research for Global Health Security; and Guidelines for Responsible Conduct of Veterinary Research: Identifying, Assessing and Managing Dual-Use) that is complementary to BTWC states parties’ discussions and decisions promoting education and training of scientists in biosecurity responsibilities.

The main international organisations responsible for protection of human, animal and plant life, and health (and therefore for addressing threats to them) are the WHO, OIE and FAO. The WHO and FAO also jointly established the Codex Alimentarius Commission to work on international food and feed safety. The disease control activities of each organisation centre around specific legal instruments:

- The International Health Regulations (2005);

- The Terrestrial Animal Health Code, Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, Aquatic Animal Health Code, and Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals; and

- The International Plant Protection Convention.

Their work is also supported by surveillance and response systems, expert advisory groups and networks, and collaborating centres and laboratories. The WHO, for example, has over 800 collaborating centres in 80 countries supporting its programmes, and the OIE has 60 collaborating centres, and a network of reference laboratories focusing on scientific and technical research on over 100 serious animal diseases. Surveillance and response activities, include generalised systems such as the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, World Animal Health Information System, and FAO’s emergency prevention and response systems (EMPRES); and disease specific systems such as the WHO’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System.

In response to a breakdown in the international system for sharing of influenza viral samples in 2006/2007, the WHO took action to revise its Global Influenza Surveillance Network, enhancing traceability through an Influenza Virus Traceability Mechanism, and establishing the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework, which includes centralised stockpiles of vaccines and treatments for distribution to developing countries during outbreaks of human pandemic potential. The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of the Benefits Arising From Their Utilization (to the Convention on Biological Diversity) also has relevance to the international sharing of microbial genetic resources, which may interact with global public health efforts.21

In recognition of the overlaps between protection of human, animal and plant life and health, the FAO, OIE and WHO have instituted several cooperative initiatives, including (for example): OFFLU a FAO-OIE network of expertise on animal influenzas, and the FAO-OIE-WHO Global Early Warning System for Health Threats and Emerging Risks at the Human-Animal-Ecosystems Interface (GLEWS). They also regularly send representatives and provide information to BTWC meetings.

In general, capacity building efforts that focus on building national health system capacities will increase the effectiveness of surveillance and response efforts and reduce the risk of international spread of serious disease outbreaks. Such efforts are supported by states parties to the BTWC, WHO, OIE, FAO among other international organisations and through mechanisms such as the Standards and Trade Development Facility — a partnership between FAO, OIE, WHO, the World Bank and World Trade Organization — that supports access to international markets through development capacities to meet and maintain international standards in food safety, animal and plant health. The World Bank has also increased its activities relating to pandemics over the last few years, including creating a Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility to support countries’ outbreak response and limit their international spread.

While these activities appear extensive, there are particular concerns about their effectiveness in relation to capacity to contain and address serious outbreaks of international concern, whatever their origin. The Global Health Security Index — a partnership of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, John Hopkins Center for Global Health Security, and Economist Intelligence Unit — which focuses on assessing global health security capacities, has recently reported and raised the following key points in this regard:22

- National health security is fundamentally weak around the world. No country is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics, and every country has important gaps to address.

- Countries are not prepared for a globally catastrophic biological event.

- There is little evidence that most countries have tested important health security capacities or shown that they would be functional in a crisis.

- Most countries have not allocated funding from national budgets to fill identified preparedness gaps.

- More than half of countries face major political and security risks that could undermine national capability to counter biological threats.

- Most countries lack foundational health systems capacities vital for epidemic and pandemic response.

- Coordination and training are inadequate among veterinary, wildlife, and public health professionals and policymakers.

- Improving country compliance with international health and security norms is essential.

Table 4: Coverage and gaps in pandemic preparedness and biological security governance.

3.4 Climate change

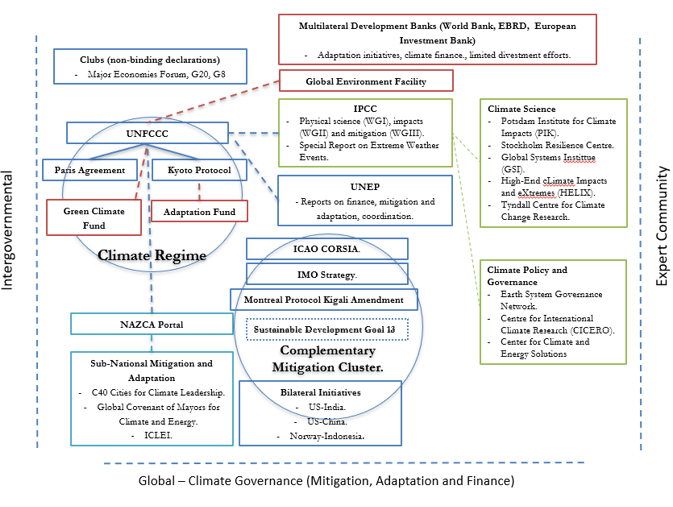

Fig. 7: The climate regime complex.

The global governance of climate change is one of the most well-studied and addressed GCRs under international law. International efforts to address to climate change largely began in 1992 with the creation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC has since been the lynchpin of international legal efforts to address climate change. It includes provisions on adaptation to climate impacts, mitigation, as well as broader considerations such as capacity building. It also establishes the overarching norms and principles of climate diplomacy, such as “common but differentiated responsibilities”.

The UNFCCC is the focal point of the climate regime and has been operationalised through two separate protocols:

- The Kyoto Protocol: created in 1997, before entering into force in 2005. The Kyoto Protocol contains provisions for monitoring, transparency and verification of emissions, market-based mechanisms (including for international emissions trading and offsetting), financing, and adaptation actions and mitigation targets. It is composed of a two-annex system whereby developing country parties are bound to legally binding emissions reductions targets. Developing countries are not bound by any mitigation targets. The first commitment period of the protocol lasted until 2013. The 2012 Doha Amendment which extends to the Kyoto Protocol’s second commitment period through to 2020 has yet to enter into force due to a lack of ratifying countries.

- The Paris Agreement: created in 2015, entered into force in October 2016. The agreement contains provisions on adaptation, mitigation, market-based mechanisms, loss and damages from climate impacts and multiple other mechanisms. The agreement has set an international target to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to keep it to 1.5 °C. It is a pledge-and-review agreement in which countries offer self-determined pledges (nationally determined contributions/NDCs) which are collectively reviewed every five years.23 The agreement only offers one additional binding legal obligation to the UNFCCC: to put forward a pledge every five years. Its structure was watered down to allow for the US to join via an executive agreement rather than Senate ratification.24

These three institutions constitute the UN climate regime. They have set the primary targets and rules for adaptation and mitigation that other institutions follow and implement. In addition to adaptation and mitigation, there is also governance of loss and damages. This refers to managing the damages incurred by the detrimental impacts of climate change, including slow-onset events, and extreme weather events. In 2013 the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (Loss and Damage Mechanism) was established to govern this area. It offers a dialogue platform for relevant stakeholders and aims to enhance knowledge of risk management and support through finance, technology and capacity building. It does not, as developing countries originally desire, provide rules for financial compensation or remediation.

The climate regime is served by multiple institutions providing financial and intellectual resources. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is the primary financial organ of both the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. The GCF is financed by member-parties to the UNFCCC. It has committed USD $5.2 billion to 111 projects covering both adaptation and mitigation.25 The Global Environment Facility was previously the main financer of climate projects, but has now taken a secondary role to the more recent GCF.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides the science basis for international climate governance. It is an intergovernmental scientific process that builds a consensus-based depiction of the science of climate change (working group I), impacts (working group II) and mitigation (working group III). The IPCC provides both assessment reports every five years, as well as special reports both at its own discretion and at the request of the UNFCCC parties.

The IPCC is complemented by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which has provided an abundance of report on climate governance. These include rolling reports on the mitigation gap, adaptation gap and climate finance.

The proliferation of climate-related law and institutions had a watershed moment in 2015. The Paris Agreement was met with a raft of long-awaited climate-relevant policy announcements. These included the Kigali Amendment to phase out hydrofluorocarbons (HCFs, a potent greenhouse gas and replacement for ozone depleting substances), the Carbon Offsetting Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) Under the International Civil Aviation Authority (ICAO) and goal 13 of the Sustainable Development Goals. In 2018 the International Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) released an initial strategy on emissions reductions from shipping. This includes an aim to peak emissions from shipping as soon as possible and reduce them by 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. These different initiatives form a cluster of complementary mitigation efforts outside of the central climate regime. However, in terms of the efficacy of these initiatives, the SDGs are non-binding and offer no concrete targets or mechanisms. The CORSIA agreement is a voluntary agreement based on offsetting. The IMO strategy offers high-level, non-binding strategic guidance with goals that are not congruent with limiting warming to 2 °C.

Mitigation and adaptation activities are also carried out by a range of other intergovernmental bodies. Mini-lateral forums such as the G20, G8 and Major Economies Forum have all made multiple statements regarding climate change. These are non-binding political declarations but can help to mould norms and build political momentum.

Adaptation and mitigation actions are occurring through a range of UN agencies and affiliated institutions. These include large climate finance programmes from the World Bank, European Investment Bank (EIB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Numerous UN agencies, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) are looking to mainstream climate adaptation and mitigation considerations into their projects and programmes.

Actions by subnational and non-state actors are loosely linked to the climate regime. The “NAZCA” platform is a database of non-state and subnational climate actions and pledges maintained by the UNFCCC Secretariat. While it is a useful depository for tracking international efforts, it has no mandate for comparing, critiquing or influencing non-state actions. The actions of sub-national entities such as cities, localities and regions are undertaken through a range of networks including ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability, a network of more than 1,750 local and regional governments), C40 Cities for Climate Leadership and the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy.

While mitigation and adaptation are well covered broadly, the response to tipping points or global catastrophe is not. Scientific knowledge of tipping points26 and early warning signals27 has progressed substantially. Yet the primary instruments of the climate regime do not have dedicated mechanisms to either induce a rapid response in the case of a looming tipping point, nor to adapt to or recover from an unforeseen climate catastrophe. International climate governance is focused on the average, rather than high-impact, low-probability ”tail risks”.

A second blind spot is supply side governance. Regulating the extraction, development and refining of fossil fuels offers numerous economic and political advantages.28 Yet the Paris Agreement makes no mention of fossil fuels. None of the instruments of the climate regime ban the exploration or development of fossil fuels. This has led to recent calls for an international fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty.29

Importantly, the existing governance has not been successful in diverting the world away from dangerous warming. Current emissions trajectories have the world moving towards warming between 2.0–4.9 °C by 2100,30 with a median of around 2.6–3.1 °C31 or 3.1–3.5 °C.32 The Paris Agreement is unlikely to be able to bend the emissions curve down to 1.5–2 °C. Both weak compliance mechanisms, an unproven method of ”ratcheting up” commitments, and the lock-in of emissions-intensive infrastructure by 2020 all undermine the effectiveness of the agreement.33

Table 5: Coverage and gaps in governance to prevent catastrophic or extreme climate change.

3.5 Solar geoengineering

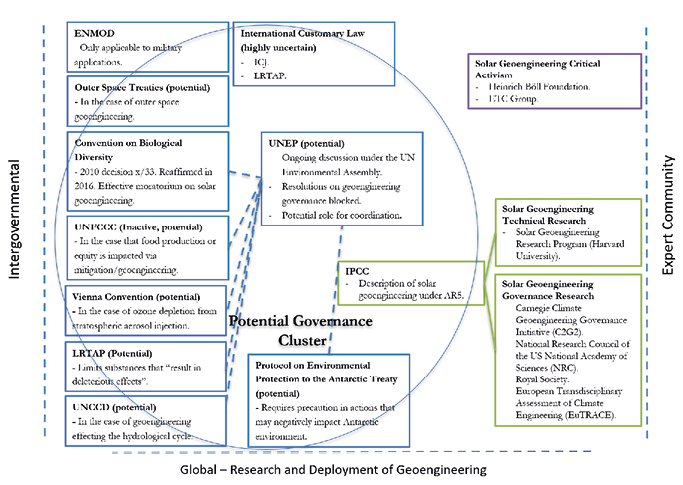

Fig. 8: Solar engineering regime complex.

There is no explicit international governance of solar geoengineering. As shown in Figure 3, there is a large cluster of treaties which could be relevant. However, these are unplanned, incidental and piecemeal with limited ability for binding application.34 Thus, there is widespread agreement that there is no distinct solar geoengineering regime and a need for direct governance.35

There that norms and rules around environmental impact assessments and harms from transboundary pollution have relevance in guiding the testing and use of such technologies. For example, the International Court of Justice has affirmed that states have a duty under international customary law to avoid major transboundary harm to either the global environmental commons or the territory of other states.36 However, the application of customary international is highly uncertain and unlikely to be effective in overseeing or deterring unilateral or multilateral deployment of solar geoengineering, or even smaller field-tests.37

The most direct piece of solar geoengineering governance is the 1976 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (“ENMOD Convention”). ENMOD was established in the wake of US attempts to weaponise weather manipulation during the Vietnam War. It appears to have been successful in curtailing research efforts into weather modification. By 1979 US research into the area had declined sharply.38 However, the use of ENMOD is limited for solar geoengineering as it only covers military applications. The preamble of ENMOD actively endorses the potential civilian uses of geoengineering type activities: “… the use of environmental modification techniques for peaceful purposes could improve the interrelationship of man and nature and contribute to the preservation and improvement of the environment for the benefit of present and future generations.” Given that the majority of use cases of solar geoengineering are likely to be civilian, ENMOD is of restricted utility.

In lieu of any overarching authority, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has undertaken action on governing geoengineering research and deployment. In 2010 the CBD adopted a decision which could be taken as a de-facto moratorium on large-scale geoengineering. Paragraph (w) of decision x/33 states: “that no climate-related geo-engineering activities that may affect biodiversity take place, until there is an adequate scientific basis on which to justify such activities and appropriate consideration of the associated risks for the environment and biodiversity and associated social, economic and cultural impacts.”39 There is an exception for small-scale scientific research studies that can be performed in a controlled environment. The decision was reasserted in 2016, with the caveat that further transdisciplinary research and knowledge-sharing was needed to understand governance options and the potential impacts.40 However, these are non-binding decisions, and ultimately the CBD lacks enforcement mechanisms. It also lacks the participation of one of the most credible potential developers of solar geoengineering: the US.

While international legal arrangements are sparse, there has been a groundswell of work from expert communities. A watershed moment was the 2009 Royal Society Report into governance and ethical issues. This was followed by a 2010 report examining geoengineering regulation by the UK House of Commons Scientific and Technology Committee, a 2011 report by the Kiel Earth Institute, a 2013 piece by the Congressional Research Service in the US and 2015 assessment by the European Transdisciplinary Assessment of Climate Engineering (EU-TRACE).41 Geoengineering was then covered in the IPCC’s fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2014 and will be investigated in further depth in AR6.

Geoengineering governance is now a well-established sub-field with academics across multiple institution involved. Technical research has been slower due to social concerns and the previous failure of the 2011 SPICE (Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering) programme.42 The experiment has sought to field-test a delivery system for stratospheric aerosol injection but faced severe public backlash.

Table 6: Coverage and gaps in governance of solar geoengineering.

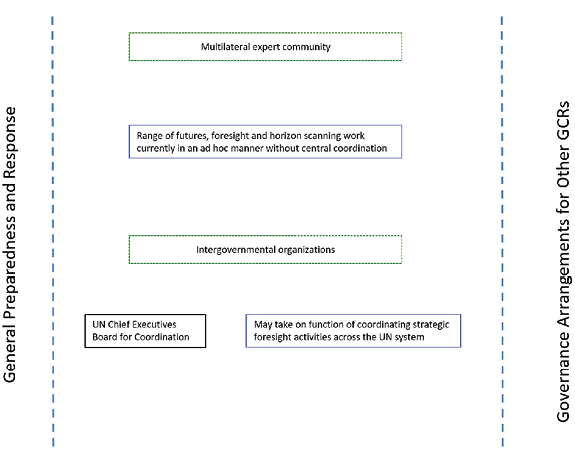

3.6 Unknown risks

Fig. 9: Unknown risks regime complex.

There are two particular elements to consider when seeking to identify global governance arrangements for unknown GCRs:

- Processes that might help with identification and analysis of emerging threats.

- General governance arrangements relating to preparedness, resilience and response to GCRs.

And, while we do not know the source and mechanism of unknown risks, we do have some knowledge about the likely objects of protection — that is, what it is we seek to protect from any such risk — and therefore which areas of governance we might look to for developing responses should such risks become apparent. For example, whatever the source of risk, we are likely to be interested in protecting human, animal and plant life and health and stability of planetary life support systems.43

General GCR governance arrangements are addressed in Section 5.

Processes that might help with identification and analysis of emerging threats involve futures studies, foresight and horizon-scanning work, and a range of approaches are available within this. Such activities do have some limitations, and using a combination of approaches, and joining up different exercises can address some of these. They necessarily face their greatest limitations in identifying unknown risks, but there are some techniques for approaching this: for example, through use of “wild cards”. Involving a wide range of expertise within such processes will also have greater value, particularly because unknown risks may be more likely to occur at the intersection of e.g. different technological areas.

Some national governments and agencies within them regularly undertake foresight activities, often with an aim of identifying potential emerging threats. Such activities are also undertaken by research institutions, science academies, and professional organisations. Global governance of unknown risks could benefit from mechanisms to bring together information from such exercises, so that analysis can be conducted over time and across different countries, regions and sectors.

Several of the international organisations involved in GCR governance conduct simulation exercises which can serve a similar function by helping to identify potential gaps and challenges in responding to emerging threats, and some are exploring the potential use of foresight activities for their work (although not necessarily with the aim of identifying unknown risks, such processes might be adapted to do so). Science and technology review processes associated with some of the organisations may also be a useful basis for such work (although they tend to focus on shorter-term horizons or recent developments). Existing systems for early warning and surveillance may also help to identify novel threats: for example, the health impacts of a novel risk may be picked up before the source of the risk is identified.

The UN Chief Executives Board for Coordination, which is made up of the heads of the UN’s specialised agencies, funds and programmes, and focuses on fostering coordination and coherence across the UN system, is examining the opportunities for “integrating strategic foresight into its work and… for promoting foresight capacities and fostering collaboration across the system”44 — if pursued such activities could significantly enhance foresight capacities at the global level.

Table 7: Coverage and gaps in preparedness for unknown GCRs.

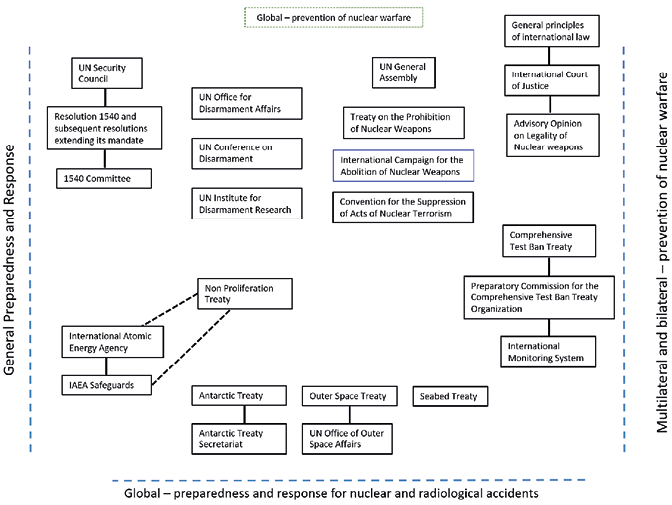

3.7 Nuclear warfare

Fig. 10: Nuclear warfare regime complex.

The extremely severe effects of an all-out nuclear war mean that prevention of such an event is a priority for global governance efforts. If such an event were to occur a response to a range of damage would be needed. Large numbers of immediate fatalities would be expected, particularly where major population centres are targeted (80–95% in a 1–4 km radius);45 there would be significant health impacts on a large scale, compounded by the loss of health systems, staff and infrastructure; widespread environmental contamination; extensive disruption to critical infrastructure; large-scale migration; and probably continued geopolitical instability. If at a sufficient scale to cause “nuclear winter” the associated collapse in global agricultural production would result in global famine and starvation.

Global governance specific to nuclear warfare focuses on:

- Reductions in armaments, with an eventual goal of general and complete nuclear disarmament.

- Preventing proliferation of nuclear weapons and diversion of nuclear materials.

- Measures to stabilise relations between nuclear states, avoid misinterpretation through communication mechanisms, and build confidence through verification and inspection arrangements.

- Creation of nuclear-weapon free zones.

Legal arrangements include:

- Some global legal instruments including a general prohibition on nuclear weapons. These instruments have not all achieved participation of (all) nuclear weapons states, and some are yet to enter into force.

- Some multilateral agreements, generally around creation of nuclear-weapon-free zones, and involving a set of regional states and accompanied by protocols that commit nuclear weapons states to not testing or using nuclear weapons within those zones.

- Some bilateral agreements, primarily between the US and Russia.

The main international organisations operating in this area include the UN Security Council and General Assembly, Conference on Disarmament, and Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), the Preparatory Committee for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). There are also some multilateral export control groups.

(Specific details on each of the legal instruments, agreements and organisations is provided in Appendix I, available online).

Civil society movements have played a significant role in shaping global governance of nuclear warfare, particularly through: the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICANW), which was pivotal in bringing about the successful negotiation of the Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty; the World Court Project that prompted states to take the issue of legality of nuclear weapons to the International Court of Justice; and in establishing nuclear-weapon-free cities, local authorities, and regions. Expert networks support the work of the IAEA, and the Preparatory Committee of the CTBTO, particularly its monitoring systems.

The humanitarian impacts of nuclear war, including nuclear winter scenarios, have motivated a lot of these global governance efforts; however, addressing such impacts is largely outside the focus of these legal arrangements (aside from some generalised commitments to assist states attacked with nuclear weapons).

Some international organisations’ work, which relates to dealing with nuclear accidents, may provide a basis for such responses, but it is generally unclear whether this would be possible and how adaptable and scalable such activities might be. This work includes: two IAEA conventions; guidance documents; and networks of emergency responders and other experts. The effectiveness of a response is therefore likely to depend on general global governance for disaster preparedness, resilience and response and emergency management. This is unlikely to be systematic enough to deal with the full range of immediate through to long-term impacts, nor adequate for such a scale of catastrophic event. Such capacities may also have been damaged or impeded by the geopolitical instability that resulted in nuclear war.

Table 8: Coverage and gaps in governance of nuclear risks.

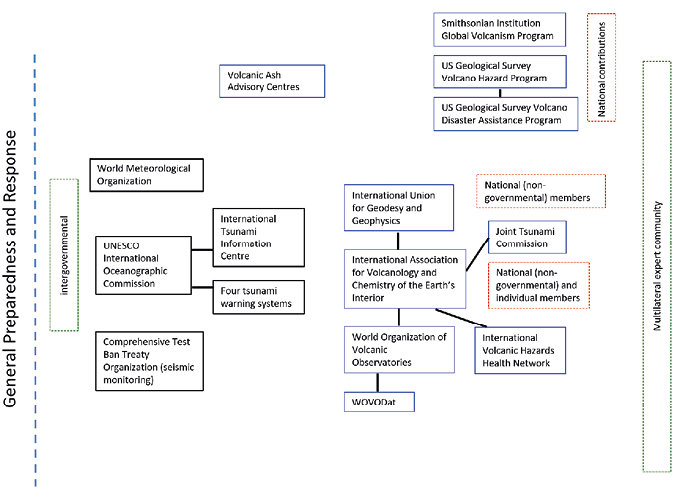

3.8 Super-volcanic eruption

Fig. 11: Super-volcanic eruption regime complex.

Global governance arrangements specific to super-volcanic eruptions are sparse and primarily limited to expert networks and collaborating research institutions. These mainly focus on scientific and technical aspects of monitoring and observation. Given limited (if any) prevention capability, most of the activities addressing impacts will fall under general global governance of disaster preparedness, resilience and response. The areas that need to be addressed include: immediate impacts including large-scale loss of life and damage to critical infrastructure (some volcanoes are in areas with local populations of over five million, and there could also be resulting tsunamis effecting other regions); and the longer-term global impacts associated with climate disruptions and resulting agricultural production losses, which could result in widespread starvation.

Super-volcanic eruptions are predicted to occur far more frequently than globally catastrophic asteroid impacts (~1 in 17,000 years compared to ~1 in several hundred thousand years), so the even more limited governance response probably represents a major gap, particularly if the general global governance of disaster preparedness, resilience and response is inadequate. Anyway, improved global coordination of the research, observation, monitoring and early warning of volcanic eruptions would be beneficial.

Central to international coordination efforts is the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI, an association of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics). National members of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG), of which there are 72 currently, and its associations participate in a non-governmental capacity. 52 IUGG national members participate in of IAVCEI, which also has individual members. Two commissions of the IAVCEI have particular relevance to governance of super-volcanic eruptions: the World Organization of Volcano Observatories (WOVO), which facilitates cooperation between 80 observatories located in 33 countries; and the International Volcanic Health Hazards Network, an interdisciplinary expert network, which collates research and disseminates information on volcanic health hazards and impacts.

A lot of data collection, analysis and dissemination is done by national-based bodies and research institutions such as the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program and the US Geological Survey’s Volcano Hazard Program. The latter includes a Volcano Disaster Assistance Program, which provides expert support and equipment during volcano crisis events worldwide. WOVODat (linked to the WOVO and hosted by the Earth Institute of Singapore) is also building a global database on volcanic unrest with the aim of improving eruption prediction. Data from seismic monitoring conducted as part of the activities of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization may also contribute to data on volcanic unrest.

Nine Volcano Ash Advisory Centres serve the needs of the aviation industry during eruption events. The World Meteorological Organization also provides advice for aviation following eruptions, and may provide information about weather and climate impacts of eruptions. It also has a general disaster risk reduction programme which includes impacts from volcanic eruptions and tsunamis.

Depending on the eruption site, a tsunami may follow a super-volcanic eruption. IAVCEI along with two other IUGG Associations (the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth’s Interior, and the International Association of Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences) have a Joint Tsunami Commission to exchange scientific and technical information with countries that may be affected by tsunamis. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s International Oceanographic Commission (IOC) has a Tsunami Programme which includes intergovernmental committees for four warning systems (covering the Pacific, Indian Ocean, Caribbean, and North East Atlantic and Mediterranean). The IOC has a mandate to develop a global Tsunami warning system, but this has not yet been established. The International Tsunami Information Centre, associated with the Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System also carries out programmes for risk assessment and for local community education on preparedness.

UNESCO also has a Geohazards Programme, focusing on associated disaster risk reduction, management and mitigation. While its overview mentions super-volcanic eruptions as events that can threaten humankind, but there doesn’t seem to be any work addressing them in the programme.

Table 9: Coverage and gaps in governance for super-volcanic eruptions.

4. Drivers and Vulnerabilities

Global Catastrophic Risk is not just a reflection of hazards, but also underlying vulnerabilities. The governance of these vulnerabilities is just as crucial as that of hazards. Yet the coverage of vulnerabilities, both in nature and governance, is far less developed. As a starting point, we will draw on a listing of different contributors to the collapse of previous civilisations.46 Given that previous societal collapses are the closest recurring analogues we have to GCRs, this is a prudent step. The collapse contributors include environmental degradation, climatic change, declining returns on complexity, declining returns on energy, inequality, oligarchy, as well as external shocks such as disease, warfare and natural disasters. Many of these have already been covered in our cartography, including climate change, (nuclear) warfare, disease, and GCR relevant natural disasters. Others, such as complexity and returns on energy investment, are too nascent and theoretical to be approached directly. This leaves us with environmental degradation, inequality and oligarchy. We will subsume oligarchy under inequality and address these as the two fundamental drivers of GCRs to be examined.

4.1 Inequality

Wealth inequality tends to increase inexorably over time47 and has been linked to both historical societal collapses,48 as well as other catastrophes such as world wars.49 This section will explore inequality both in terms of wealth and income inequality within and between countries. There are two separate forms of governance covering these areas:

- Equality-inducing measures within international treaties;

- Governance of mechanisms that drive inequality, primarily tax avoidance and evasion.

The significant global arrangements for poverty alleviation could also be considered as part of international efforts to reduce inequality. This includes both Official Development Assistance (ODA) guidelines under the OECD and the international financial institutions involved with economic development, such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. However, the explicit goal of these efforts and infrastructure is poverty alleviation and economic development, not the alleviation of poverty. To the contrary, efforts such as structural adjustment programmes likely worsened inequality both within numerous developing countries and the between developed and developing countries.50 Instead, we will focus on mechanisms for equity across treaties, and the governance of tax evasion and avoidance.

There is no explicit international governance of income or wealth or income inequality. The closest shadow of direct governance is SDG 10 “Reduce inequality within and among countries”.51 While the headline is compelling, the targets are ambiguous and do not set any concrete objectives or measures. Moreover, the SDGs are a non-binding declaration lacking any credible mechanism for ensuring compliance.

Equity considerations are split across multiple treaties and bodies. It has been integral to most environmental treaties. The CBD, UNFCCC and most other multilateral environmental agreements contain numerous capacity-building measures as well as financial support provisions for developing countries. This is underpinned by the principles of environmental multilateralism as enshrined in the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Principle 3 states the development must “equitably meet developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations”. Principle 5 notes the need for poverty eradication to avoid major international disparities and principle 6 notes that special priority should be given to developing countries. Mechanisms for capacity building and financial transfer are not just common across environmental agreements, but also in the areas of trade, health and security.

The international system also has a dedicated system to manage drivers of inequality such as tax evasion and avoidance. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), OECD, G20 and IMF all provide estimates of tax evasion both as revenue base erosion and profit sharing. Both the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes and the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MCMAATM) provide a platform for the exchange of basic tax information.52 The framework is unlikely to stem tax evasion or global inequality until more drastic measures, such as global wealth tax, are introduced.53

The existing framework to tackle the problem appears to be inadequate. By most measures, global inequality is deteriorating. The typical measurement of the Gini index suggests that inequality between countries has decreased over the past decade over half. In 2000 it was approximately 44, but had dropped to 39 by 2016.54 This is largely due to the economic rise of major developing countries such as China and India. However, the inequality measured by the Gini index has worsened within most countries over the past few decades, particularly OECD countries.55 Other measurements portray an even worse situation. The global wealth share of the top 1% has grown from 25–30% in the 1980s to roughly 40% in 2016.56 The real figure is likely to be far worse once the hidden treasures of tax havens are considered.57 This is testament to the ineffectiveness of the existing patchwork that governs inequality internationally.

Table 10: Coverage and gaps of global wealth inequality.

4.2 Ecological collapse

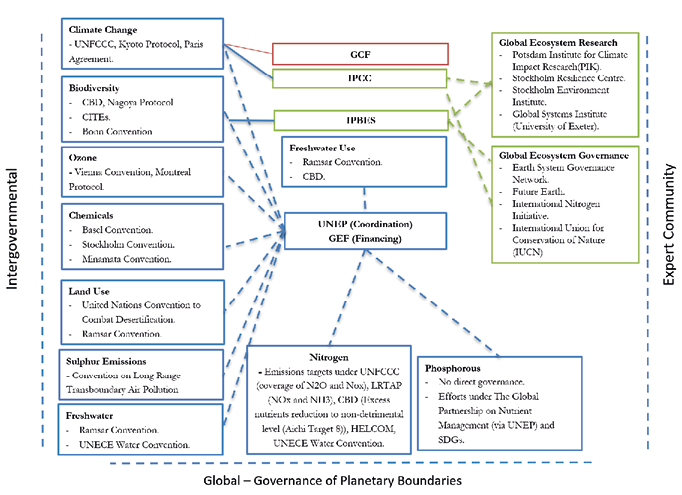

Fig. 12: Planetary boundaries regime complex.

The loss of ecosystem services is a loss of humanity’s resilience. Ecological is a broad phenomenon and it is difficult to draw clear contours around it. We will use the planetary boundaries framework to focus our analysis. The framework puts forward nine key global environmental services that constitute a “safe operating space for humanity”: climate change, biodiversity loss, the nitrogen cycle, phosphorous, ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols and chemical pollution.58

It would be impossible to depict and analyse all of the agreements relevant to the governance of ecological collapse. The International Environmental Agreements Database lists “1,300 multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs), over 2,200 bilateral environmental agreements (BEAs), 250 other environmental agreements, and over 90,000 individual country ‘membership actions’”.59 Instead, we will examine the primary instruments governing each planetary boundary. Climate change will be excluded from the analysis, as it has already been investigated.

As shown in Figure 4, the governance of ecological collapse is fragmented institutions. While the diagram depicts governance clusters for each of the planetary boundaries, this is not the case for many. Governance of land-use, freshwater, nitrogen and phosphorous are all deeply fragmented with no overarching convention of framework.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) acts as the coordinator of UN’s multilateral environmental agreements. In practice, it has struggled to ensure effective collaboration and action between the multitude of agreements.

Most of the governance arrangements are served by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The GEF acts as the primary financier of international environmental governance. It is financially replenished every four years by its 39 donor country members.60 It covers forests, international waters, biodiversity, climate change, land degradation, chemicals and other areas, using a variety of grant and non-grant financial instruments.61

- Biodiversity loss: Biodiversity loss is directly governed by the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and its 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising From Their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity. The CBD provides rules and guidance on biodiversity monitoring and reporting, management actions and targets to reduce biodiversity loss. It is scientifically served by the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The biodiversity regime is complemented by the trade-focused 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the 1979 Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (1979 Bonn Convention).

- Chemical pollution: The international governance of chemical pollution centres upon a trio of treaties: the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants; the 1989 Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal; and the 2017 Minamata Convention on Mercury.

- Ozone: The international regime is the posterchild for effective environmental multilateralism. It is underpinned by the 1985 The Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer. The treaties have been successful in addressing the problem of ozone depletion. The use of ozone depleting substances has been decreasing over the past two decades. Recent satellite data suggests that the hole in the ozone layer is now beginning to shrink and recover. This is largely due to the Montreal Protocols strong non-party mechanism (restricting trade in ozone depleting substances with non-parties) and enforcement mechanism.

- Atmospheric aerosols: The 1979 Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) is the primary international instrument for regulating sulphur emissions.

- Nitrogen: There is no explicit governance framework for nitrogen. Instead, there are targets relevant to nitrogen usage split across multiple multilateral environmental agreements. These include emissions targets under the UNFCCC (coverage of N2O and Nox), LRTAP (NOx and NH3), CBD (excess nutrients reduction to non-detrimental level (Aichi Target 8)), HELCOM (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission — Helsinki Commission), the OSPAR Commission (Nitrogen oxides or their transboundary fluxes impacting eutrophication), United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Water Convention (nitrate and nitrite concentrations).62 The diversity and fragmentation appears to have hindered efforts. A more integrated regime that targets nitrogen pollution origins would be preferable.63

- Phosphorous: Like nitrogen, the governance of phosphorous is fragmented. There are also non-legal approaches to governing both nitrogen and phosphorous. Foremost is the Global Partnership on Nutrient Management under UNEP.

- Land-use: Land-use governance occurs primarily through a duo of legal instruments: the 1994 UN Convention to Combat Desertification and the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. The Ramsar Convention is largely a pledge and review system, requiring countries to voluntarily submit wetland areas of importance to be regulated under it. Both lack effective enforcement and compliance mechanisms.

- Freshwater: As with phosphorous and nitrogen, there is no framework convention or overarching legal instrument to govern freshwater usage and pollution. It occurs through a patchwork including the UNECE Water Convention and the Ramsar Convention.

While not part of the Planetary Boundaries framework, population growth is a key driver of our collective environment impact. Direct governance of population is almost non-existent. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) contains a population division. Its role is relegated to demographic research, including population projections and analysis. It has no role in attempting to curb global population growth. Nor does any other UN legal instrument or framework.

Overall, the global governance of phosphorous, nitrogen, atmospheric aerosols, and freshwater are the largest gaps in the protection of planetary boundaries. However, other important oversights exist. There is little effective, coherent governance across boundaries given their deeply interconnected nature. The role of coordination largely falls to UNEP. However, as an under-resourced programme under the UN General Assembly it has often struggled to effectively fulfil this task. As with climate change, there are no mechanisms to govern tipping-points, early-warning signals and the aversion of catastrophic ecological collapses. While there is the general international norm of the “precautionary principle” its exact meaning and implementation has often been hindered by ambiguity.

Like inequality, indicators for ecosystem collapse have been worsening over time. Ecological footprint per capita has trended steeply upwards since 1960, as far back as records go.64 The Living Planet Index, a composite measurement for biodiversity, has also been more than halved from 1970 to the present day.65 This warning signals suggest that despite that the governance of planetary boundaries while abundant is porous and inadequate.

Table 11: Coverage and gaps in governance of planetary boundaries and ecological collapse

5. The Broader GCR Governance Landscape

5.1 UN governance

The UN contains broader governance arrangements that are relevant for GCRs. First and foremost is the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), which oversees the implementation of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. This includes efforts to build resilience, coordinate emergency responses to disasters and ensure effective recovery. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2015 and provides four priorities and seven targets for action. However, both UNDRR and the Sendai framework are focused on non-GCR, natural hazards. Their efficacy and mandate in reducing GCRs is questionable. It was preceded by the Hyogo Framework for Action, which covered disaster risk reduction guidance for the decade of 2005–2015.

Disaster management splintered across a wide range of bodies including WMO and WHO. The WHO includes decisions and frameworks for disease outbreaks, risks in emergencies, poisoning, displaced peoples, complex emergencies (caused by warfare or the large-scale movement of people) and other areas. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) contains numerous programmes to assist countries in reducing both climate and disaster risk. These include activities on geohazard risk reduction, water hazard risk reduction, school safety, tsunamis, disaster risk reduction in UNESCO designated sites and crisis management and post-crisis transitions. Actions in these areas focus on knowledge provision and capacity building.

There has been nascent, unsuccessful discussion of introducing intergenerational governance mechanisms into the UN. This includes the 2012 push for an Ombudsman for Future Generations (to be located under the Secretary General) at the Rio+20 negotiations and the Secretary General’s 2013 report on “Intergenerational Solidarity and the Needs of Future Generations”. The former was unsuccessful and the latter is a non-binding review. Successfully introduced mechanisms for intergenerational governance in the UN could have profound implications for GCR management and foresight under the UN.

Table 12: Coverage and gaps in governance of catastrophic risk by the United Nations.

5.2 Transnational governance

Taking an appropriately broad perspective on what is encompassed by global governance (as outlined in Section 2), there are various actors and activities beyond formal inter-governmental arrangements. Those significant for the global governance of GCRs include:

5.2.1 Individual experts and communities of expertise

For all GCRs a key need is for greater understanding about the risks and prevention, mitigation and response options. There is, therefore, a substantial need for contributions from a range of experts to address these areas. While some international organisations and treaty processes — and national delegations engaging with them — have some in-house expertise, this is not always the case and may well be insufficient, particularly when it comes to more extreme risk scenarios.

In some GCR governance regimes experts are quite well integrated in inter-governmental arrangements at various levels of formality (for example, in protection of human, animal and plant health). In others, clear spaces have formed in which expert communities play a key support role and help to address gaps (for example, in science and technology reviews associated with the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention). In yet other regimes, inter-governmental activity is very limited and expert communities form the core of global governance efforts (for example, in the area of super-volcanic eruptions).

Expertise may be provided on an individual basis or collectively through a representative organisation (such as a scientific academy) or through participation in collaborative networks (such as laboratory networks supporting the work of the World Health Organization).

An extensive range of disciplinary and practical experience and expertise is needed for effective governance of GCRs. Careful consideration of how to bring knowledge together across fields and integrate it in governance activities is needed, and there is substantial scope for further research and practical action in this regard. This needs to be worked out — and exercised — well in advance of potentially catastrophic events otherwise interventions are more likely to fail. (For example, the lack of integration of social science in international responses to the 2014 Ebola outbreak has been recognised as a key failure point).66

The role of experts in global governance is not unproblematic. There need to be ways of assuring quality, relevance and legitimacy of expertise — which can be assisted, for example, by use of peer networks. Setting particular standards for qualifications and level of experience can be useful, but can also privilege participation by certain groups and limit representativeness. Transparency about potential conflicts of interest is also important. Sometimes relationships between expert communities and formal governance processes are difficult; as at other levels, international policy making is not always evidence-based and policy-makers can have unrealistic expectations about expert input, e.g. expecting a level of certainty that is not achievable. Resourcing of expert communities can also present challenges; being transparent about funding sources is important, and political difficulties could arise where one particular state or agency is the main source of support for a group. Some expert groups will be disadvantaged by lower levels of funding and access to other resources such as facilities, equipment or data. As identified in some of the regime summaries, there is also a need to be alert to the sustainability of governance efforts where they rely heavily on expert activities and to have contingency plans should a key funding source be withdrawn.

5.3.2 Civil Society Organisations (CSOs)

CSOs also perform valuable roles in relation to GCRs governance, some of which we highlight here (with further examples provided in some of the regime summaries):

- Form the basis for transformative global campaigns to address particular GCRs — the role of the International Campaign for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons in advancing negotiations towards the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is a prominent recent example.

- Provide a route of connection from the local to global levels both in bringing citizens’ concerns to the attention of international bodies and in connecting international governance initiatives back to local action. (For example, this can be seen in the connection between local communities and the work of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction in the Community Practitioners Platform for Resilience).67

- Provide global connectivity between groups with aligned interests and concerns, amplifying their ability to effect action transnationally. Examples include the Global Fossil Fuels Divestment Movement,68 and the Mayors for Peace initiative, which brings together over 7,800 cities worldwide to engage citizens in pursuit of nuclear disarmament.69

5.3.3 Industry organisations and transnational corporations