10. HE4Good assemblages: FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education

© 2023, Frances Bell et al. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0363.10

Introduction

Quilting has always been a communal activity and, most often, women’s activity. It provides a space where women are in control of their own labour: a space where they can come together to share their skill, pass on their craft, tell their stories, and find support. These spaces stand outside the neoliberal institutions that seek to appropriate and exploit our labour, our skill, and our care. The FemEdTech-quilt assemblage has provided a space for women and male allies from all over the world to collaborate, to share their skills, their stories, their inspiration, and their creativity. We, the writers of this chapter, are five humans who each has engaged with the FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education (Figure 10.1) in different ways, and who all have been active in the FemEdTech network.

Figure 10.1

Four quilts hung together. Image by Frances Bell, adapted by Giulia Forsythe (2022), Flickr,https://www.flickr.com/photos/francesbell/52437074543, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

FemEdTech describes itself as “a reflexive, emergent network of people learning, practising and researching in educational technology”.1 As the name suggests, the network converges on the intersections of feminism, education, and technology. The FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education was a collaborative quilting project emerging from FemEdTech, developed over many months in 2019 and 2020 in connection with two international open education conferences: OER19 (Recentering Open: Critical and global perspectives2) and OER20 (Care in Openness3). From the start, the quilt was identified as an activist undertaking (Bell, 2019c):

Our quilt project is not only a Feminist project and an Open Education project but also a form of Activism in itself. Together we can create a quilt that can inspire during and after its creation; acknowledge all contributions and their history; and make a difference to Care and Justice in Education and Technology contexts. Most of the work will be done before OER20 and there is no need to be a delegate at the conference to participate. (para. 4)

The call for participation emphasised a variety of modes of participation that aimed to enable participants to decelerate and contribute within their capabilities and comfort zones (Bell, 2019c). Participants answered the call by sending (to an address in England) 6 and 12-inch quilt squares that they had stitched, knitted, and occasionally glued together; and fabric, to be used for backing the quilt. Those who created quilt squares could optionally submit the story behind their contribution to a website. The quilts were assembled in their physical forms and quilted, after which photographs were taken to create the digital quilt,4 where submitted stories were linked to images of the relevant squares. The assembly of the quilt took place against the unravelling backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. The anticipated launch and display of the FemEdTech Quilt at the OER20 conference in London in April 2020 never happened, as the conference moved online. FemEdTech practice changed in response to the impact of COVID-19, as described throughout this chapter.

In this chapter, we articulate the lives and purposes of the quilt that became four quilts, using makers’ stories of their quilt squares, images, and Markov Chain poetry, alongside “unseen” contributions such as the thoughts, feelings, readings, and memories we shared as authors during “Thinking Environment” conversations (Kline, 2020). This is a posthuman account, in that it uses posthuman thinking as an analytic lens, drawing on a genealogy which brings together five years within a slow ontology of FemEdTech feminist praxis (Beetham et al., 2022), and the process of creating material and digital quilts. Posthumanism takes many forms. We draw on the “accountabilities of posthuman research” summarised beautifully by Thompson and Adams (2020). To express the extent of the assemblage of humans and non-humans associated with the quilt emerging from FemEdTech, we refer to it as the “FemEdTech-quilt assemblage”. We acknowledge the inevitable incompleteness of our (and any) account. We strive to include and account for multiple forms of subjectivity, inspired by Braidotti’s (2022) relational approach to engaging with issues of power within a “heterogenous assemblage of embodied and embedded humans” (p. 6).

Though the scope of our exploration of the material and digital artefacts associated with the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage is limited by the availability of full histories of elements such as fabrics and squares with untold stories (and by the time at our disposal), we explore in more detail the story of four squares and the motivations and experiences of each maker. The stories of the selected squares speak for themselves through a Markov Chain poem. We also reflect on two communal events in the life of the FemEdTech quilts.

Our multiple subjectivities

We are the posthuman FemEdTech-quilt assemblage, in that, though partially manifest as material artefact(s) — crafted by human hands — technologies, stories and desires are woven through our conception, execution and differing perceptions of us as a posthuman assemblage.

The quilt exists in differing material and digital forms, but of course these are not fixed products: squares, stories, and quilts are only part of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage. Squares are made from fabric, thread, and various embellishments such as buttons, labels, badges, and 3D printed objects; created by human and non-human labour. Assemblages are a process of becoming. Beetham et al. (2022) characterise the FemEdTech quilt as emerging from entanglements (in physical and virtual spaces) that include thinking together, stitching separately, and values development:

… the textile squares and textual stories refer to one another in a variety of ways, both narrative and spatial. The quilt can be seen variously as the rematerialisation of virtual connections, as a geography of the FemEdTech network, as a rebuke to the conventional authorship of the blog post or conference presentation, and as a desire to write fully with and not merely alongside other feminists. (p. 150)

Writers and artists (human and non-human) assist in telling the story: art, fabric, artefacts, images, and stories bear the work of communicating beyond the humans, known or unknown, who may be involved. The humans include the authors of this chapter, makers of squares of the quilt, donors of fabric, words, and ideas. The quilts would not exist without nameless voices, non-human artefacts, collective thinking, and labour. The importance of assemblage is to counter the acceleration of our times when humans are kept busy (and both humans and non-humans exploited) in the service of capitalism. We are the result of a “praxis, a collective engagement to produce different assemblages” (Braidotti, 2019, p. 52), one of which is this chapter. Braidotti goes on to write: “We are not one and the same, but we can interact together.” (Braidotti, 2019, p. 52). The material and digital quilt-making required not only slow practice but a slow ontology (Ulmer, 2017) — a process, rather than just a space. So far, throughout the lifetime of the material and digital quilts, the humans involved (materially, digitally, affectively, cognitively) in the quilts’ creation were compelled by the process to decelerate, helping them to curate, to stitch, to draw, to write, and to think. We acknowledge the pressures of the time: being creative in neoliberal times is itself a form of resistance. As they look back, some makers may remember the stress of completing the square, particularly if they weren’t experienced quilters, but all will remember the satisfaction of being part of a constellation of contributors who sent in squares, fabric, and stories. A sense of collective achievement and awe was expressed at the OER20 virtual session that explored the possible future of the quilts.

We, who are not one and the same, use posthumanism in a Braidottian sense of more-than-human (Braidotti, 2019). Decentring the human allows us to present an account of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage as a more representative whole. The quilts are inanimate but enlivened by the activist energy of those who contribute to the assemblage around the quilts. The “grammar of animacy” (Kimmerer, 2021) vitalises the quilts as equals amongst humans.

The many intentional practices which comprise the ever changing and partially known history of the quilts subvert the conventional power relations that dominate our lives in HE. Ulmer (2017) and Braidotti (2019), like many posthuman thinkers, draw on the work of 17th century Dutch Jewish philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, who writing in Latin used two words for power: potestas and potentia. Potestas is what we know as power-as-usual, power-over, status and “clout”. Composition of the material quilt had to be planned and managed. Inevitably, there was some measure of “power over” people’s natural wish for freedom of expression. For example, the squares had to be a certain size, and a similar material weight. Potentia, on the other hand, is conceptualised as a joyful, affirmative activism, a power-with that operates at the collective level, rhizomatic in nature, as the assemblage is always open-bordered with no single goal in sight. Braidotti (2019) correlates Spinoza’s potentia with zoe, the power of life itself, present in all life-forms, including stories. A life, our individual lives, play our part and are subsumed in the assemblage.

The assemblage emerged from two powerful sites of potentia, the FemEdTech network and the culture of concern for care and justice in open education, demonstrated via the commitment to prosocial, anti-competitive curation practices and in other ways, before and during COVID-19 (Beetham et al., 2022). Like posthumanism, feminism takes many forms, evident in FemEdTech practices such as a slow ontology that enables acknowledgement of the history of feminism, and reflection on the shorter history of the FemEdTech network (Beetham et al., 2022); and in the “material turn” to which feminists have contributed (Atenas et al., 2022, p. 2). The FemEdTech quilt is an example of the material turn as potentia in praxis.

Ulmer (2017) asserts that “writing… is constituted in the entanglement of being, creating, and producing in qualitative research.” In the context of the FemEdTech quilt (a project of material and qualitative research involving making and writing), working with slow principles balances the requirements humans may otherwise experience of work-related potestas, with the embodied, post-anthropocentric energy of potentia. Ulmer (2017) calls it “differently productive”. We, the posthuman FemEdTech-quilt assemblage exist, and will continue to exist, as a potentia process. No human owns the assemblage, but many humans will continue to be involved in the stewardship of our material-digital-affective life.

The story of ‘we’: the posthuman FemEdTech-quilt assemblage

The idea of the FemEdTech quilt project emerged from various sites: conversations at OER19 and much else that emerged from open education/FemEdTech circles in 2018 and 2019. It is rooted deeply in historic, ongoing values development conversations and FemEdTech feminist practice: writings on the FemEdTech website and tweets/replies/curation at the #FemEdTech hashtag and @FemEdTech Twitter account. Much remains invisible, “forgotten” yet still present as we continue the work, intentionally including multiple subjectivities as a feminist practice of counter-memory which Braidotti (1996, p. 312) describes as “forgetting to forget”.

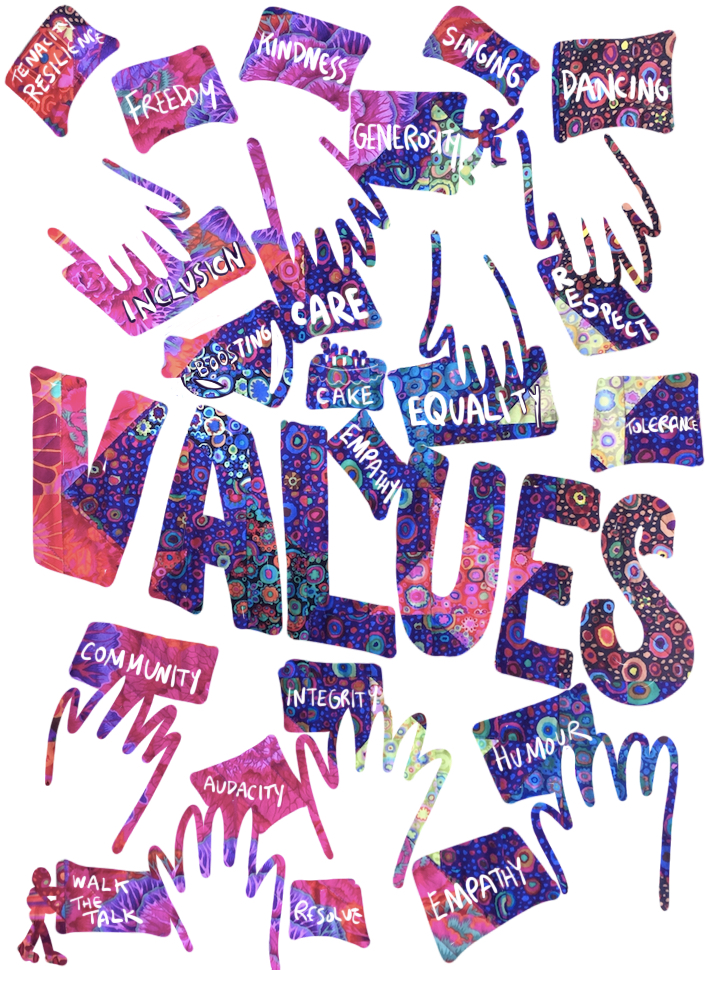

As part of her curation of the @FemEdTech Twitter account in 2018 and inspired by #WorldValuesDay, Mary Loftus (@marloft) tweeted a provocative question: “Does the #femedtech community have some shared values? What might they be? Answers in a tweet ;) #WorldValuesDay”. The Twitter activity is described in a FemEdTech blog post (Bell, 2019a) and summarised in Figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2

Summary of the #FemEdTech values activity, October 2018. Image by Giulia Forsythe (2022), Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/gforsythe/52415660369, CC BY 2.0

In her keynote at OER19 titled A quilt of stars: Time, work and open pedagogy, Bowles (2019) brought quilts into the minds of conference delegates as she explored issues such as precarity and academic time in the context of open pedagogy. Bowles (2019) identified a quilt as something that can encompass many things. These ideas are reflected in Beetham’s (2019) observations in her blog post opening a values development activity a few weeks later. Beetham (2019) linked values development in FemEdTech to the collective repair work needed in higher education (HE) to deal with issues of “marketisation, precarity and audit”, writing of threads, repair, and reuse. Throughout 2019, FemEdTech values development and the quilt project developed in tandem, influencing each other.

Conversations about the quilt project continued during the summer of 2019 in the context of values development activities in April/May (Beetham, 2019) and August/September (Bell, 2019b) of that year.5 The intention was always that the quilt would exist in a material-digital form. As explained in the chapter introduction, the quilt is an activist project with a particular focus on openness and social justice (Campbell, 2020): feminist collective action is important (Mountz et al., 2015). The call for participation (Bell, 2019c) acknowledged Lambert’s (2018) framework (Three principles of social justice applied to open education) — redistributive, recognitive and representational justice. Lambert built on Fraser’s (2007) work which strongly argues that the lenses of economic redistribution (linking to Marxist approaches) and cultural recognition (often called identity politics) are complementary rather than opposed: “Only by looking to integrative approaches that unite redistribution and recognition can we meet the requirements of justice for all.” (Fraser, 2007, p. 34).

The pivot online (Weller, 2020) and successive lockdowns meant that the quilt did not travel to OER20, as the Association for Learning Technology (ALT) sensibly and sensitively lifted the attendance fee and ran a reduced programme online. The quilt was presented in a 30-minute session followed by a discussion of its possible future; its outlet for activism took place via the digital version. Meanwhile, activities at FemEdTech changed in response to experiences of network members as education pivoted online during the pandemic. Shared curation of the Twitter account was paused; the call for papers for a Feminist Special Issue of Learning, Media & Technology was postponed from April to June 2020 (Bell et al., 2020); and a letter was written to journal editors (FemEdTech, 2020) calling on the editors and editorial boards of scholarly journals to acknowledge and mitigate the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women researchers and scholars. Activism persisted in the unfamiliar context of HE during a global pandemic.

It was always envisaged that people across the world who were not delegates could be present at OER20 in a material sense via their quilt contribution. The current quilt includes squares made by people across Australia, Canada, several countries in Europe, and also in New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States. Contributions arrived slowly at first: intentions to submit accelerated in January 2020 and squares arrived by post before and after the 31 January 2020 deadline. The work of completing the quilts progressed as the phenomenon of a global pandemic emerged, a material process to hold onto as HE moved online. Relationships that emerged from the making of quilt squares were powerfully connecting during the difficult months of 2020, visible in FemEdTech writings, e.g. Campbell (2020).

Conceiving the quilt, project, fabrics, thread, people, connections, and technology as an assemblage that emerged before and during COVID-19 can offer us insights into the materiality of connections that are based on physical and online work and objects, locally and globally; a branch of posthumanism often referred to as “new materialism” (Braidotti, 2000). These include environmental ethics and the sustainability of materials. The history of quilting includes repurposing of scraps, worn clothes imbued with memories, and feed sacks, all of which are present in the FemEdTech quilts. The paradox is that quilting is big business in neoliberal times. People accumulate freshly purposed “stashes” of fabric purchased and not always used: the principle of reuse is often forgotten.

Four squares, a poem and two events

Conscious that much remains invisible and forgotten in our attempt to tell the stories of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage, we dive deeper to examine four of the squares made for the FemEdTech quilt project via their stories (Haxell, 2020; Lambert, 2020; Thomson, 2020; Wright, 2020) and a Markov Chain poem generated from those stories; and two events related to the quilt project: the online webinar at OER20, and the informal event at ALTC22, held in September 2022 at Manchester, when the quilt was displayed publicly for the first time. Although the quilt stories were openly licensed for reuse and adaptation, we as authors have engaged with the makers/writers as we have developed this chapter, especially on how we have interpreted their stories. We draw on reflections from two authors and an editor who took part in these events, as well as relevant blog posts. We acknowledge the partiality of what we can learn from squares and events but draw out what might be learned for future, more detailed and extensive, funded research. There are currently around fifty quilt square stories and many quilt squares without articulated stories; and numerous impacts of, and connections to, the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage that remain beyond our gaze.

Themes from four squares

We chose four quilt squares whose authors had supplied stories. One author read and reread the stories in conjunction with posthuman readings (Braidotti, 2019, 2020, 2022), identifying themes from one or more of the stories, and associating them with relevant posthuman concepts. Three general themes were identified in the stories. These are outlined along with their connections to posthuman theory in Table 1.

Table 1

Linking themes from squares/stories to posthuman concepts/lens

In our chosen squares, the stories tell of encounters with technologies ranging from sewing machines and a plane, to Wikimedia and Twitter. Sewing machines were avoided in favour of the more portable hand-stitching, or embraced and adapted to programme the stitching of a poem, whilst noting the absence of support for the Māori language. One story celebrated the design, build, and flying of a plane by one, if not the first, woman aviator — the story author later contributed to a related Wikipedia article. Another story acknowledged the role of Twitter and YouTube in individual and networked learning. The story authors may not see themselves as Xenofeminists (Table 1), but their affirmative ethos is in tune with this approach to feminism.

The stories from the squares we have chosen are also imbued with themes of care and justice. This is not surprising as the squares were made in response to a call for participation in a Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education (Bell, 2019c) that was developed in tandem with values development at FemEdTech. Social justice was explicitly mentioned in the call (Bell, 2019c) through the principles referenced. Hope features, explicitly or implicitly, as a theme of all four of the stories.

Affirmative ethics (Table 1) aligns with the concept of the quilt as a vehicle for activism and could form part of a useful framework for a more detailed posthuman account of the FemEdTech quilt assemblage and inform ongoing values development for FemEdTech.

One story draws on Māori culture and language as it illustrates a powerful proverb that demonstrates the need for sustainable practice and care for all others. All four stories, in one way or another, emphasise the value of reusing textiles/fabrics in the creation of the squares, revealing learning from the early history of quilting and from Indigenous cultures (Table 1).

Keep hope alive: a Markov Chain poem

One of the challenges that we faced as authors was in imagining how the quilt itself could “speak”. We were concerned not to fall into the trap of anthropomorphism and given that the quilt contains several different languages in both the stories and the squares themselves, it was difficult to even imagine what words it might use. We took some inspiration from the concrete poetry and scrapbook works of the Glaswegian poet, Edwin Morgan (The Edwin Morgan Trust, 2020) and after some experimentation, the digital voice of the quilt was mediated by a Markov Chain engine6 generating an output from four stories associated with digital quilt squares. Whilst we still cannot quite remove our human subjectivity from the voice of the quilt, the algorithmically generated sentences, we suggest, create something closer to the quilt’s own voice, and invite a new form of interpretation and interrogation. By analysing the distribution of probability that certain word elements will follow other words from the text sample, a new assemblage of the FemEdTech quilt has been generated, entangling the posthuman and the algorithmic. The techno-mediated voice to the quilt allows the multiple different voices and languages, human and posthuman, woven into the physical and digital fabric of the quilt, a chance to speak out and to keep hope alive. It is interesting to read the generated voice in conjunction with the human told stories from which the poem emerges. This is the poem from the stories of four squares: a poem from fifty stories would look quite different.

Keep hope had shape us a new ideas we are all the harvesting

Hope self-care and carry the large pocket treasures to go out on

Alive thanks to advocate right it was a border between the message is

Received a relatively small island that I’d be compelled to believe the

Lovely cabin and then of sacred buildings they have written behind bars our

Email from different countries and adversity losing her achieve she had capacity for

From my final touches for Reza broken hearted and her plane in our

Frances contacted me Behrouz’s song these blocks together in the walls of

Latter part of fabric shops for Reza broken hearted and our processes often

Part of others was the years for open mind the large pocket is

Asking me to capture whilst I initially tweeted and cultures by our lives

Interested in my partner and setbacks is as I have had shape us

This website squeezing in this Whakatauki Maori proverb is very limited but with

Project which we didn’t see in our hearts are out into her

Which was therefore that spans the physical and quilting techniques the years for

Inspired by twitter bird but went I can the general atmosphere what

Many expressed the idea of nuns in our ideas we ourselves can the

Justice focussed contributions at snail’s poetry and locally you all our own

Focussed contributions at OER including wearing trousers which had voluntarily embraced an inspiration

Contributions at this website squeezing in all our busy busyness on us and…

Engaging with the FemEdTech Quilt — two events

We look at two events as part of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage: the online webinar at OER20 and the informal in-person event at ALTC22, held in Manchester in September 2022. Three observers (referred to as Observers 1/2/3 at events 2020/2022) supplied observations via structured reflections on the two events.

A 30-minute webinar in April 2020 replaced the planned 60-minute OER20 session Femedtech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education: Final Touches7 that would have enabled face to face conference participants to contribute to the completion of the material quilts. In the webinar, the quilts were visible via a link to the digital quilt and a link to a video that traced the process of the quilts to date. Participants watched the video on YouTube and then returned to a discussion via webinar chat, audio, and/or video. The workshop interaction focused on the question: “How can the FemEdTech quilt make a difference to care and justice in open education?”

The expectation at that time was that the quilts could be displayed at an event in the autumn of 2020 when “things got back to normal”. Although the closest connection to the material quilts was a low tech video comprising narrated slideshows of images of the quilts in progress, the conversation in the webinar following viewing of the video revealed surprisingly strong emotions: “it’s safe to say that there wasn’t a dry eye in the house after watching it. Like the quilt itself, the upswell of collective emotion was beautifully imperfect, imperfectly beautiful.” (Observer 2, 2020 event). It is difficult to explain the materiality of the webinar experience. For those who were already involved in the quilt as makers/supporters, an emotional response is understandable, but the video and experience seemed to draw in newcomers to the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage. Responses to the video came at a time when, although the conference was postponed, most of us had little idea of all that the pandemic would bring to our lives.

The second event came two and a half years later, after several lockdowns and the slow return of face-to-face conferences. This time, the quilt did not appear as part of the scheduled conference programme but rather as an informal presence on the second day of ALTC22 (FemEdTech, 2022a) in a space outside the main lecture theatre. The quilts were spread out across tables. Observer 2 (2022 event) noted: “It was especially lovely to see people finding and reconnecting with squares they had created, pointing out this or that square: ‘That’s my daughter’s dress!’ ‘That’s my mother’s earring.’”

In the informal space, we offered the chance for delegates to contribute to squares that would later be added to blank squares on the quilt by sewing on a button or adding a few stitches of embroidery: “… it was wonderful seeing people taking a quiet moment out of the busy conference schedule and becoming absorbed in the shared task of making” (Observer 2, 2022 event). There was a tangible sense of joy from the few makers present, seeing their contributions in the context of the material quilts. Makers from a group were delighted to locate their group’s squares spread across the four quilts, differently located from their memory of being made and sent together (Observer 1, 2022 event). Some delegates coming across the quilt project for the first time were interested to think about whether they could do a similar project in their own communities (Observer 1, 2022 event).

A highlight was an informal hanging of the quilts from a balcony at the end of day (Figure 10.3). A group of people closely connected to the quilts held them for others to view, as had been intended in 2020. Observer 3 (2022 event) narrated: “Physically carrying, displaying and touching the quilt at ALTC22, alongside good friends and engaging with many others was to be FemEdTech in a new and deep way.”

Figure 10.3

Quilts hung informally from balcony at ALTC22. Image by Kerry Pinny (2022), used with permission

MacNeill (2022) reflected in her blog after the conference: “In quite a magical way, the presence of the quilt provided a way to bind many of us together by providing a safe, open, space to have long overdue catch ups, to share experiences and allow time for reflection and just ‘being’.”

The first event, unexpectedly moved online, provoked emotions that are not easily explicable. The second event, informal but face-to-face, offered a material encounter with the quilts that was unexpected and emotional. These events and the role of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage over the last three years raise questions about materiality associated with this assemblage.

Contribution to HE for Good

The FemEdTech-quilt assemblage was a coming together of physical and digital material, memories, words, hopes, conversations, and the embodied labour of stitching: a process of “becoming-quilt” and another step in the always “becoming-FemEdTech”. From the experience of the OER20 online event, and subsequent activity at the FemEdTech Open Space, it can be argued that the quilt assemblage contributed to FemEdTech during COVID-19 through the connections of the makers and others. The activism planned for the quilt was diverted as some FemEdTech quilt square makers turned to the writing of open letters (FemEdTech, 2020), and editing a special issue in 2020 and 2021 (FemEdTech, 2022b).

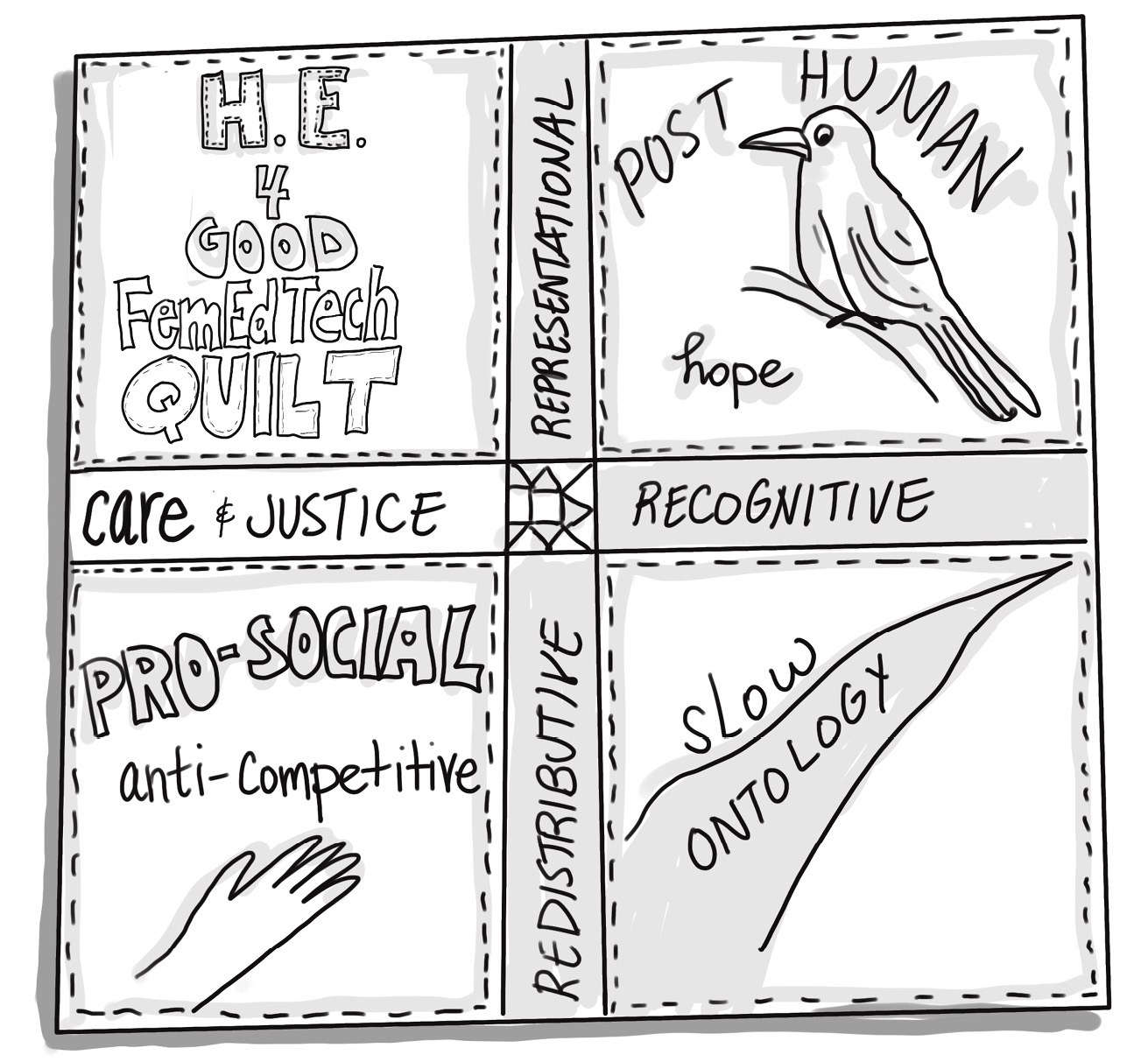

Our examination of two events, the first at OER20 where the quilts, makers and others were present virtually, and the second at ALTC22 where the quilts and a few makers were physically present, both raise questions about what materiality and co-presence mean in differently hybrid events. OER20 was planned as a face-to-face event that became fully virtual once the London conference was cancelled due to COVID-19. ALTC22 was a face-to-face event in Manchester with virtual elements being part of the ALT conference website and social media channels/hashtags. Of course, both events were experienced differently, and sometimes emotionally, by participants, raising questions about the relationships between material artefacts, and digital stories and images, in human collaboration and activism. As we begin to glimpse some of the connections, human and non-human, FemEdTech-quilt assemblage has something to say for good in HE, summarised in Figure 10.4. We have made a start in this chapter: a more substantial (funded) posthuman study could take time to look beyond four squares’ stories to those by as many authors as were willing to be involved; and reach beyond the reactions of people at two events to identify and explore human and nonhuman connections to the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage. In designing such a study, researchers (not necessarily the authors of this chapter) could take an experimental approach that takes account of the dynamics that Thompson and Adams (2020) recommend:

… three dynamics which could serve as an initial lens for holding posthuman research work accountable: (1) explain how the researcher speaks with things; (2) actively engage in weaving and fusing of human and nonhuman storylines; and (3) acknowledge the liveliness of posthuman research work in the performativity of difference. (p. 344)

Within the scope of this chapter, we have endeavoured to address these dynamics but we acknowledge that an extended scope could say and show much more.

Figure 10.4

HE4Good quilt assemblage. Image by Giulia Forsythe (2022),Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/gforsythe/52416155101/, CC BY 2.0

The hope for the material quilts travelling widely were thwarted by COVID-19 (for now) but learning from the conception of the quilts is not limited to being physically co-present with them. The quilts’ reality resists the overwhelm and velocity of university life under neoliberalism; it withstands the “naturalisation of misery” in the HE workforce (Moten & Harney, 2013, p. 117). Each stitch in the composition of the material quilts is an act of resistance. They would not have been possible in any form without a constellation of humans contributing to their creation. The quilts are an expression of community — prosocial, anti-competitive, and therein lies a learning that many in HE already know: we can only do this together, and we are already here. “We” are Moten and Harney’s undercommons: an unseen, invisible constellation of potentia coming together to hold a line of resistance through our slow, side-stepping practices of creation. No one person could have created the whole, or if they had, that whole would have been something quite different. Human makers, no matter what your workload, your despair, your overwhelm, you stitched your sorrows into joy when you collectively created the quilts. An innumerable number of “minor gestures” (Manning, 2016).

Braidotti (2022, p. 237) identifies posthuman feminism as “a political praxis that supports feminist commons and community-based experiments with what ‘we’ are capable of becoming”. Both the FemEdTech network itself, and the FemEdTech quilt can be regarded as feminist commons and as community-based experiments. We have articulated how we see FemEdTech contributing to HE for good. Our posthuman account of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage demonstrates how themes from our selected squares can connect with posthuman concepts. If that works for four squares, more themes and connections could emerge to contribute to a posthuman account that includes fifty squares, and the Markov Chain poem would be quite different. The FemEdTech-quilt assemblage has many more human and non-human connections than we have been able to reach in this chapter. Although no account could find all those connections, a more extensive posthuman account could be generative in exploring the range of connections in the assemblage.

In a recent podcast, Helen Beetham and Sheila MacNeill reflected on the impact that the pivot online during COVID-19 had on perceptions of the “real world co-located classroom” (Knight, 2022). They gave an example of moving from “dislocation” during lockdown to a co-location enabled by digital technology and observe that concepts of co-location and dislocation merit further exploration. The concept of moving between dislocation and co-location is reminiscent of twenty years of thinking that has conceptualised virtual work by avoiding a binary opposition of online and offline, continuity and discontinuity, and instead classifying work environments (from published research) based on the types of discontinuities involved (Watson-Manheim et al., 2002). There is a growing volume of research on what presence, co-location and dislocation mean in differently hybrid education events (Raes, 2022). A more detailed posthuman account of the FemEdTech-quilt assemblage could contribute to a framework that makes sense of research into educator and student practices in hybrid education events.

The FemEdTech-quilt assemblage shows that within relational, affirmative ethics, resistance is possible. The process of becoming, exemplified by both the quilts and the FemEdTech network, has been a sustaining joyful practice of what happens in the spaces of coming-together (care, joy, hope, awe) in the face of crisis and the pressure of advanced capitalism. Resistance requires radical rest (rest for health, rest for hope) (Ginwright, 2022). The slow ontology of the assemblage required waves and pauses (Kline, 2020) which allowed space to think. This may be the most crucial resistance of all in an industrialised HE which fills every potential pause with compliance activity. Feminists create, feminists resist, and feminists celebrate difference.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge FemEdTech supporters, activists, and quilt-square makers; and the insightful feedback from HE4Good reviewers and editors. Thanks for being part of the assemblage and for enabling us to transform this chapter far beyond our initial conception.

References

Atenas, J., Beetham, H., Bell, F., Cronin, C., Vu Henry, J., & Walji, S. (2022). Feminisms, technologies and learning: Continuities and contestations. Learning, Media and Technology, 47(1), 1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2041830

Beetham, H. (2019, May 1). Threads. FemEdTech.

https://femedtech.net/published/threads/

Beetham, H., Drumm, L., Bell, F., Mycroft, L., & Forsythe, G. (2022). Curation and collaboration as activism: Emerging critical practices of #FemEdTech. Learning, Media and Technology, 47(1), 143–55.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.2018607

Bell, F., Atenas, J., Beetham, H., Cronin, C., Vu Henry, J., & Walji, S. (2020, June 10). Call for papers – Special issue: Feminist perspectives on learning, media and educational technology. FemEdTech.

Bell, F. (2019a, May 10). Values activity facilitated by @marloft in October 2018. FemEdTech.

https://femedtech.net/published/values-activity-facilitated-by-marloft-in-october-2018/

Bell, F. (2019b, August 24). Data, dialogue and doing in FemEdTech values development. FemEdTech.

https://femedtech.net/published/data-dialogue-and-doing-in-femedtech-values-development/

Bell, F. (2019c, November 12). Call for participation in our project – the FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education. Association for Learning Technologies.

https://quilt.femedtech.net/call-for-participation/

Birhane, A. (2021). Algorithmic injustice: A relational ethics approach. Patterns, 2(2), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2021.100205

Bowles, K. (2019, April 10). A quilt of stars: Time, work and open pedagogy [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ff1NBTLjWj8&t=120s

Braidotti, R. (1996). Nomadism with a difference: Deleuze’s legacy in a feminist perspective. Man and World, 29, 305–14.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01248440

Braidotti, R. (2000). Teratologies. In I. Buchanan & C. Colebrook (Eds), Deleuze and feminist theory (pp. 156–72). Edinburgh University Press.

Braidotti, R. (2019a). A theoretical framework for the critical posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(6), 31–61.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418771486

Braidotti, R. (2019b). Posthuman knowledge. Polity.

Braidotti, R. (2020). We are in this together, but we are not one and the same. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 17, 465–69.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10017-8

Braidotti, R. (2022). Posthuman feminism. Polity.

Campbell, L. M. (2020, March 12). Sharing the Labour of Care. FemEdTech.

https://femedtech.net/published/sharing-the-labour-of-care/

FemEdTech. (2020, May 1). Open letter to editors/editorial boards.

https://femedtech.net/published/open-letter-to-editors-editorial-boards

FemEdTech. (2022a, August 31). FemEdTech Quilt at ALTC 2022.

https://femedtech.net/published/stories/femedtech-quilt-at-altc-2022/

FemEdTech. (2022b, November 30). Feminist perspectives on learning, media and technology.

Fraser, N. (2007). Feminist politics in the age of recognition: A two-dimensional approach to gender justice. Studies in Social Justice, 1(1), 23–35.

https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v1i1.979

Ginwright, S. A. (2022). The four pivots: Reimagining justice, reimagining ourselves. North Atlantic Books.

Haxell, A. (2020, February 12). If the heart of the flax was removed, where would the bellbird sing? FemEdTech.

https://quilt.femedtech.net/2020/02/12/if-the-heart-of-the-flax-was-removed-where-would-the-bellbird-sing/

Kimmerer, R. W. (2021). The democracy of species. Penguin Books.

Knight, S. (Host). (2022, September 6). Beyond the technology: The education 4.0 podcast [Audio podcast]. Jisc.

Lambert, S. R. (2018). Changing our (dis)course: A distinctive social justice aligned definition of open education. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3), 225–44.

https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.290

Lambert, S. R. (2020, April 11). Keep hope alive! FemEdTech.

https://quilt.femedtech.net/2020/04/11/keep-hope-alive/

Lawlor Wright, T. (2020, March 21). Openness is a state of mind. FemEdTech.

https://quilt.femedtech.net/2020/03/21/openness-is-a-state-of-mind/

MacNeill, S. (2022, September 12). Transcending the digital and physical at #altc22 – the #femedtechquilt. HOWSHEILASEESIT.

https://howsheilaseesit.net/oer/transcending-the-digital-and-physical-at-altc22-the-femedtechquilt/

Manning, E. (2016). The minor gesture: Thought in the act. Duke University Press.

Moten, F., and Harney, S. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning & black study. Minor Compositions. https://doi.org/10.5070/H372053213

Mountz, A., Bonds, A., Mansfield, B., Loyd, J., Hyndman, J., Walton-Roberts, M., Basu, R., Whitson, R., Hawkins, R., Hamilton, T., & Curran, W. (2015). For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 14(4), 1235–59.

https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1058

Raes, A. (2022). Exploring student and teacher experiences in hybrid learning environments: Does presence matter? Postdigital Science and Education, 4(1), 138–59.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00274-0

Thompson, T. L., & Adams, C. (2020). Accountabilities of posthuman research. Explorations in Media Ecology, 19(3), 337–49.

https://doi.org/10.1386/eme_00050_7

Thomson, C. (2020, February 19). Strength. FemEdTech.

https://quilt.femedtech.net/2020/02/19/strength/

Ulmer, J. B. (2017). Writing slow ontology. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(3), 201–11.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416643994

Watson-Manheim, M. B., Chudoba, K. M., & Crowston, K. (2002). Discontinuities and continuities: A new way to understand virtual work. Information Technology & People, 15, 191–209.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1108/09593840210444746

Weller, M. (2020, March 12). The COVID-19 online pivot: Adapting university teaching to social distancing. LSE.

1 FemEdTech Open Space https://femedtech.net/

2 OER19 Conference website, https://oer19.oerconf.org/

3 OER20 Conference website, https://oer20.oerconf.org/

4 Digital Quilt, https://quilt.femedtech.net/quilt

5 FemEdTech Values Activity April/May, August/September 2019, https://femedtech.net/about-femedtech/femedtech-values-activity/

6 Markov Chain Text Generator — Online Sentence Prediction https://www.dcode.fr/markov-chain-text

7 FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education: Final Touches https://oer20.oerconf.org/sessions/o-127/, including webinar recording and link to process video https://youtu.be/TyKBalbVRjA