Section IV Making Change through Teaching, Assessment and Learning Design

‘Little Me’ by Sheila MacNeill (CC BY 4.0)

Note from the artist

This work is based on a work which I created as part of a collaborative project for the NPA Lab 2021 Collaborative Online Exhibition. Our project was titled “Copped Out” and used the COP26 Climate Change Conference as its central theme.

Living in Glasgow, I was intensely aware of the impacts of the conference — both at local and global levels. One of the most profound experiences for me was a night time march with Little Amal, the 2m puppet who has walked from Syria to Europe. Watching and following Little Amal as part of a torch lit parade was an intensely emotional experience. Hearing small children ask questions about the why and how of her reminded me of the importance of education and sharing lived experiences of the impact of our actions.

The puppet has an almost hyper real presence, embodying struggle, fear, resistance, hope but most importantly, humanity. Education is the key to all our futures, signifiers such as Little Amal bring the plight and stories of real people to those who are currently protected from the ravages of human cruelty and climate change. Her presence creates new empathy, understanding and new narratives, providing hope. I hope that this image provides some synergies with the narratives of hope being shared in this book.

16. A design justice approach to Universal Design for Learning: Perspectives from the Global South

© 2023 Aleya Ramparsad Banwari et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0363.16

This chapter focuses on the issue of exclusion in higher education and how to promote inclusivity by implementing Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles within a larger social and design justice context. The chapter critically analyses the strengths and challenges of a UDL approach within a Global South context, highlighting how social and design justice can be attained by focusing on broad conceptions of access and equity. The chapter documents the experiences of four postgraduate students in their roles as educational technology advisors (ETAs) at the University of Cape Town, outlining collaborative insights arising from the authors’ varied positionalities and disciplinary backgrounds (Friedman, 1998; Kim, 2016). The chapter seeks to offer a challenge to established epistemological paradigms that regard the core nature of knowledge as impartial and absolute, as well as to catalyse more significant insights into inclusive, accessible, and socio-culturally responsive education practices in higher education.

Introduction

It is long established that formal education, in its role to meet the needs of the nations within which it is situated, can be as exclusionary as it can be liberating and empowering (Boughey, 2012; Khalid & Pedersen, 2016; Steyaert, 2005). Interwoven with the social, cultural, political, and economic dynamics of societies and the world at large, education and its exclusionary mechanisms extend beyond the physical structures of teaching and learning. Issues such as perpetuated language barriers and ableism permeate the fabric of higher education (HE). Educational exclusion impedes a student’s learning experience, the direct consequence of socioeconomic conditions occurring outside of the academic realm (Sayed, 2003). Being unheard and underrepresented can cause students to feel alienated in their educational journey.

In this chapter, we consider UDL in the broader context of design justice and social justice. South Africa faces many challenges in the HE sector due to rising inequality, lack of stable access to electricity and other services, and high data costs, amongst many others. Historically, “the university” in South Africa as an institution of HE has been systemically exclusionary by perpetuating practices, values, and beliefs aimed at helping to further the interests of colonialists and, presently, the Global North (Brodkin et al., 2011). This extends into the realm of digital colonialism practices, in which institutions in the Global North develop much of the content that is utilised in the Global South. This is often done without consultation or contextualisation of who this content will be taught to and under what circumstances. The reasons that knowledge generated in the Global North is dominant are multiple, sometimes including the cost of materials and the lack of equivalent materials in the Global South; itself perhaps a by-product of the reach that material generated in the Global North has historically had. Unfortunately, the result remains the same: such practices implicitly privilege knowledge generated in the Global North instead of knowledge generated in the Global South (Adam, 2020). A social justice approach may aid in highlighting and then addressing these exclusionary practices.

Social justice, design justice, and Universal Design for Learning

Social justice can be framed as fairness in distributing wealth, resources, and opportunities (Fraser, 2005). The economic challenge of access to technology for some students, in conjunction with the aforementioned cultural issue of privileged epistemologies and the political issue of neo-colonialism, can be galvanising points to explore curriculum design and, by extension, design justice.

Understood as an “ethical praxis of world-making” (Escobar, 2018, p. 21), design is an integral feature in understanding the world around us. Design often reproduces existing hegemonic worldviews, which can silence marginalised communities and different ways of being (Escobar, 2018). There have been considerable strides made towards addressing this exclusion through better integration of technologies and more epistemologically driven means, such as Achille Mbembe’s concept of the “decolonial pluriversity” (Reinders, 2019). A decolonial pluriversity is a space where a multitude of knowledge systems can exist on equal footing through dialogue, allowing for greater accessibility and a greater diversity of thought (Mbembe, 2015). It is impossible to achieve a decolonial pluriversity without addressing the underlying structures that prevent transformation from taking place (Luckett & Shay, 2017).

We argue that to achieve decolonial pluriversity, one must be cognisant of existing inequities, which manifest through curriculum design and dissemination in addition to socioeconomic and political equities. Only once we acknowledge existing inequities can we genuinely aim to combat ongoing disparities. The implementation of design justice can be used to bring this change about (Boidin et al., 2012).

Design justice brings to light how the design of objects, systems, and structures affect the production and distribution of risks, harms, and benefits among various people (Costanza-Chock, 2020). Design justice approaches can ensure a more equitable distribution of a design’s benefits and burdens in a manner that promotes accessibility, thus allowing for more meaningful participation in design decisions and subsequent proceedings. Accessibility or the ease of access to information, services, or knowledge is critical to design justice in HE. A curriculum that empowers all people, strengthens societal dynamics, and addresses local needs should be the norm. Though a global commitment toward inclusive education exists, ways to actualise it are still being sought. UDL can be one step towards this commitment (Karisa, 2022).

Universal Design for Learning has gained international attention as a promising framework for reducing barriers to education and developing equitable, quality learning for all (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020; McKenzie et al., 2021; Zhang & Zhao, 2019). The goal of UDL is to design educational experiences that allow all students to match their unique ways of learning to varied modes of engagement, information representation, and expression of learning (CAST, 2018; McKenzie & Dalton, 2020).

Originating from disability accommodations in primary and secondary education settings, its proponents claim that it can also improve learning and inclusion for all students in HE settings (CAST, 2018). Inclusive practices are needed for all learners regardless of learning needs, socioeconomic status, and socio-political standing. It is envisaged that the UDL framework and its underpinning principles can enable design justice through intentionally redesigned courses for accessibility, equity, and inclusivity. Such an approach to course redesign may serve as a vehicle to actualise this. For example, providing well-described video lectures with closed captioning and transcripts ensures that students with hearing and visual impairments can engage meaningfully in lessons.

Our theoretical framework utilises Nancy Fraser’s concept of social justice (2005), which contains three dimensions: economic, cultural, and political. These three dimensions speak to three key issues to help address injustice: redistribution (economic), recognition (cultural), and representation (political). In an educational context, redistribution refers to the equitable distribution of resources, including monetary resources for access to university. Recognition refers to ensuring equal access to a rich and intensive curriculum for students of all backgrounds. Representation refers to increased mechanisms for marginalised voices to be heard. For example, there should be a forum or platform for students who are differently abled to be heard (Fraser, 2005; Keddie, 2012).

Furthermore, recognition means that all stakeholders in the HE sector must be seen as “full partners in social interaction”, allowing for increased participation (Fraser, 2000) of lecturers, students, external examiners, and representatives of government, industry, and civil society. Recognition and representation feed into one another. If we can provide recognition to marginalised communities in HE sectors, and give them a platform to be heard, we can enable representation (Caden, 2012). Social justice must be grounded in design justice. Design justice is defined by Costanza-Chock (2020) as:

a framework for analysis of how design distributes benefits and burdens between various groups of people.… Design justice is also a growing community of practice that aims to ensure a more equitable distribution of design’s benefits and burdens; meaningful participation in design decisions; and recognition of community-based, Indigenous, and diasporic design traditions, knowledge, and practices. (p. 23)

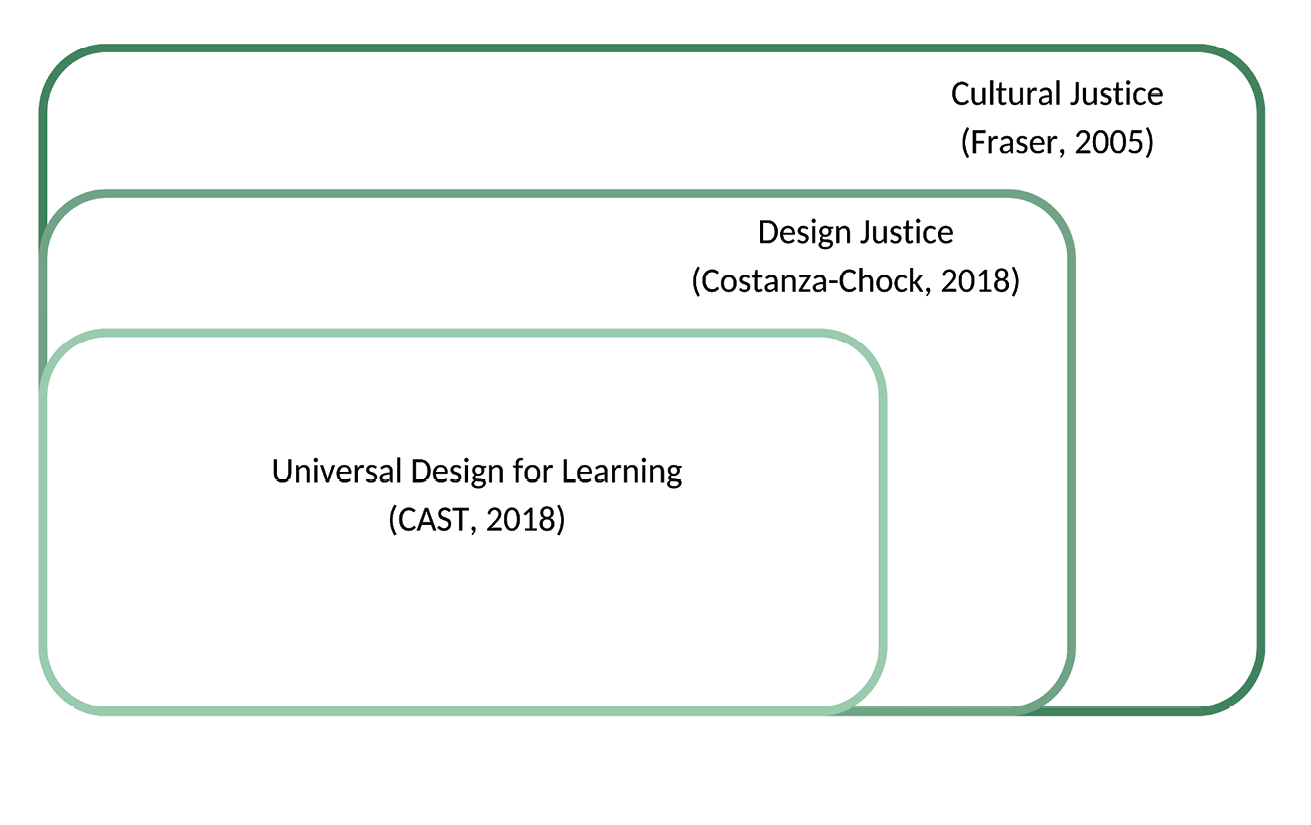

UDL acts as a framework for a more equitable distribution of the design benefits of curriculum and learning design (see Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1

Locating social justice within UDL, design justice, and cultural justice

Considering UDL in a Global South context

Universal Design for Learning is a framework initially developed by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) to provide a blueprint for a learning design process that will be equitable and inclusive (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020). Since its conception, UDL has been utilised as an increasingly popular framework in the education sector of countries in North America and Europe (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020). The UDL framework is built on the three pillars of “representation, action and expression, and engagement” (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020, p. 4). These three principles are based on areas in the brain responsible for recognition, strategy, and affect (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020). They emphasise student diversity by advocating for multiple and appropriate forms of representation, action and expression, and engagement when designing a learning experience (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020). The principle of multiple means of representation refers to providing students with various ways of accessing learning material and the learning process. Practically, this can mean providing transcripts of voice recordings or videos or making infographics with alternative text on the content available to be accessible to students who are auditorily or visually impaired. Providing students with multiple means of action and expression will create opportunities for students to convey what they have learned in diverse ways. For instance, this can mean that some students will be assessed using a traditional written examination while others may opt for an oral examination. Finally, multiple means of engagement in UDL refer to how students learn and interact with the course material. By providing different methods of engagement, a more diverse range of students can be included in the learning experience.

UDL has become a central tenet in many North American and European HE institutions, where it is positioned as a paradigm for inclusivity that is premised on principles of sustainability (Fovet, 2020). This, in turn, allows for a reduced burden on accessibility services, as the needs of students can be addressed in the classroom itself, and can also lower the total expense while still revolutionising how we perceive education. These strong claims made about UDL motivated the writing of this section, which critically examines the successes of the implementation of UDL and addresses some of the barriers to learning that UDL unwittingly fails to consider.

UDL in the Global South

Since its inception, much has been written about UDL with most of the research centred on North America and Europe respectively (Cai & Robinson, 2021; Fovet, 2020; Olaussen et al., 2019). As UDL gains greater attention as a paramount inclusion in educational policy and practice, the need to understand how it is utilised in contexts outside the regions mentioned above becomes more crucial. As a result, this section explores the application of UDL in the Global South. The Global South broadly refers to the regions of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania.

There is a recognition that UDL has the potential to engage students, improve social inclusion, lead to higher achievement outcomes, and reduce the risk of stigma for marginalised students, including those with disabilities (Almumen, 2020; Lowrey et al., 2017; Mackey, 2019). The UDL framework recognises the individuality of learners and can facilitate more collaborative approaches and increased digital inclusion if support structures are implemented that enhance equity and accessibility. UDL’s features of openness, flexibility, and foresight can enlighten teaching and learning practice, moving the focus of teaching methods from the curriculum and texts to the needs of and relevance to the learners.

Much like the broader concept of inclusive education, UDL has often been adopted as a way better to integrate learners with disabilities into the academic mainstream. Additionally, more focus is placed on the use of technology. Perspectives from the Global South appear to be breaking from this trend as they focus on how UDL can be used to enhance education and accessibility of all students, considering the barriers and different ways it can be applied. For example, Chiwandire (2019) explored how established UDL principles inform HE curricula in South Africa, while Al-Azawei, Parslow, and Lundqvist (2017) studied the direct application of UDL to strengthen e-learning acceptance at an institution in Iraq. Karr, Hayes, and Hayford (2020) posit that should educators in Ghana start receiving training in UDL, improved academic performances and a reduction in the stigma around people with disabilities may be seen. Zhang and Zhao (2019) share a similar sentiment and suggest that the autonomy and expressiveness that UDL seeks to cultivate may bolster Chinese education. However, the way it is currently being implemented is still deeply rooted in the instructor’s pedagogy, indicating that instructors still need further support to change their traditional teaching philosophy and better utilise UDL technologies.

Across the literature, it is evident that the application of a UDL framework has generally failed to recognise the unequal power relations between the Global North and Global South (Fovet, 2020; Grech, 2011; Miles & Singal, 2010; Song, 2017). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there has been a limited amount of scholarship on UDL, and UDL experts and authors could be criticised for disregarding this geopolitical aspect of education (Benton Kearney, 2022). It is of utmost importance that the movement cultivates a culture where concepts such as power, privilege, and post-colonialism are critically examined and critiqued. The future of UDL in HE depends on the discourse consistently identifying the Global North/Global South divide and focusing more on embedding and magnifying perspectives from the South (Fovet, 2020).

There are significant barriers to implementing the UDL framework in the Global South. These include large class sizes, lack of resources, and lack of staff awareness regarding inclusive design (Ferguson et al., 2019; Maree, 2015; Song, 2016). A shortage of support professionals to guide educators in adapting their teaching, inaccessible environments, and an absence of effective screening and identification services exacerbates academic exclusion and implementation of interventions such as incorporating UDL into the teaching and learning space (McKenzie et al., 2021). Additionally, from our own experiences as education technology advisors (ETAs), it is evident that some educators may resist using UDL. For example, promoting accessibility and diverse learning environments is associated with a higher workload. One of the goals of UDL is to create expert learners (Rose et al., 2021). In other words, allowing learners to be the champion of their learning process.

Finally, there are other barriers that are barely addressed in the UDL guidelines. These are barriers that are faced by students who have been excluded, marginalised, or diminished because of their skin colour, language, ethnicity, gender, and/or sexual orientation. There is plenty of evidence that such students face barriers and low expectations. However, there is little evidence that the UDL guidelines are either relevant or attentive to these kinds of identity barriers they face (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2021). A scoping review by McKenzie et al. (2021) highlighted that UDL applications in LMICs tend not to utilise an intersectional lens well enough. For example, disability, gender, race, and socioeconomic status are not examined in consideration of each other.

Implementation of UDL

The COVID-19 lockdown pushed education sectors across the world to move teaching and learning to online platforms. The University of Cape Town (UCT) was no exception, as it encountered many challenges during the pivot to emergency remote teaching and learning. The UCT Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching (CILT) recognised that there was a gap in translating educational content into accessible online learning. As part of a Redesigning Blended Courses project in 2020, eight postgraduate students from various backgrounds were appointed to the roles of ETAs. The primary task of ETAs was to support teaching staff to design inclusive, digitally enabled education with a UDL-centred approach strategically aligned with UCT’s Vision 2030. Recent findings suggest that the situatedness of those designing courses and curricula fundamentally affects the course released to students (Adam, 2020). ETAs were considered to be well-equipped to promote accessible and inclusive learning and teaching environments and materials because they are students and are more likely to understand the challenges that students may face. The ETAs underwent two weeks of training where they learnt about inclusivity and accessibility in relation to blended course design. Further topics covered were on student diversity and learning needs in HE, UDL, accessibility, disability and guidelines for accessible curriculum and educational content design, with reference to relevant tools and multimedia.

This chapter’s four authors formed part of the ETA cohort. We hail from a diverse set of backgrounds academically (disability studies, public health, education, and anthropology), and personally in terms of race, gender, sexuality, abilities, and disabilities. All of us had been students during a time of significant change in South African HE, punctuated by movements such as Rhodes Must Fall (2015), Fees Must Fall (2016–2018), and the gender-based violence protests of 2018 and 2019.

Our primary role as ETAs was to offer support to teaching staff to create inclusive, accessible, and multimedia-rich learning materials and activities based on UDL principles and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). These efforts aimed to enhance student access and inclusion in blended courses for improved student learning outcomes. This entailed working with lecturers and learning designers to ensure that any materials produced for learning complied with UDL and accessibility standards.

Our experiences as ETAs

In general, using UDL as a framework within a broader design justice approach was valuable in realigning focus on the diversity of our students in the university. Rather than creating a “one-size-fits-all” online learning experience, this approach to UDL allowed us to design different learning pathways. As noted earlier, the three core principles upon which the UDL framework is built are principles of representation, action and expression, and engagement (McKenzie & Dalton, 2020).

In our roles as ETAs, we ensured multiple means of engagement for students by providing video recordings of lectures with closed captions which were accompanied by transcriptions of the lectures. This allowed students to choose whether they would want to listen to the recording or read through the transcript. Another way in which engagement was fostered was by ensuring a streamlined design of the learning pathway on the learning management system (LMS), including detailed instructional text for all learning activities. This approach was especially helpful in supporting student engagement in short educational courses, as many students were unfamiliar with online learning. A more straightforward design allowed for easier site navigation. In disciplines such as accounting and health sciences, a checklist of learning outcomes was included at the end of each topic, encouraging students to engage with the content systematically. This was particularly helpful in a content-heavy discipline like accounting and self-paced courses for working students in the health sciences, promoting self-regulatory skills.

The UDL principle of multiple means of representation was accomplished by providing students with an array of text, audio, and visual representations of content. In some health sciences courses, infographics were created to simplify complex concepts. These infographics include alternative text for students using screen readers. Another visual enhancement added to course sites was introducing each topic with a flow chart, summarising the learning pathway for the topic. Each topic was also introduced with an introductory video (with closed captions) to give students a broad overview and the necessary background knowledge. ETAs from the science disciplines were especially adept at providing a student’s perspective on what constitutes a conducive learning pathway, with one ETA creating such a user-friendly learning pathway for chemistry courses that they have been asked to provide the same treatment to other chemistry courses at UCT. In addition, the two ETAs in the education discipline provided theoretically grounded perspectives on improving students’ learning experiences.

Multiple means of action and expression were enacted in various ways. First, several options for the physical act of responding to content were created. For instance, in using the comment tool on the LMS, students were able to post a written response, an audio or video clip, or a pictorial reply. Other tools in the LMS, such as the forum tool, allowed students to post their responses in diverse media. Additional communication tools were also incorporated such as Padlet and Twitter. Student expression was also guided by prompting questions on the content, helping to ensure meaningful engagement and expression.

The implementation of all three main principles of UDL using a design justice approach is perhaps best exemplified by a first-year course in the humanities that one of the chapter’s authors worked on. This course was well-designed and extremely inclusive. The class comprised over one hundred students, the majority of whom were from low-income communities and were isiXhosa first language speakers. This course was designed to make the segue into academic writing, reading, and speaking easier. Keeping the demographic composition of the class in mind, the course convenor worked with the tutors to ensure that the course outline and instructional texts were provided in both English and isiXhosa. The tutors also created WhatsApp groups for their tutorial groups to check in with their students. Students who struggled with internet connectivity could conduct their tutorial discussions over WhatsApp. These actions helped to ensure that students were supported in terms of language (UDL Guidelines Checkpoint 2.4. Promote understanding across language), but also helped to ensure no students fell through the cracks by communicating with students through a less “formal” platform such as WhatsApp. This flexibility in learning methods (which is in line with UDL Guidelines Checkpoint 5.1. Use multiple media for communication) helped to ensure student success for students who may otherwise have fallen through the cracks because of their lack of connectivity, and ability to connect with tutors and classmates.

Key insights based on our experiences implementing UDL with a focus on design justice

Throughout this project, we realised that a design justice-focused implementation of UDL is complex and requires resources and sufficient time for planning and implementation. In terms of engagement, we noticed that an overemphasis on providing multiple pathways of engagement through many online activities could cause students to become overwhelmed and lose engagement. Another issue encountered was a lack of digital literacy from students, which inhibited meaningful engagement as students struggled to access many of the representations of content. Here, time and budget constraints also played a role. For instance, a visually impaired student had issues with accessibility in one course. Many concessions had to be provided manually, such as providing alternative text to graphics in the reading material or manually creating transcripts of video resources. This proved to be time-consuming. In addition, the physical action of expression proved challenging to some students, like accessing forum discussions or comment sections. Without allocating sufficient time and resources to developing competency in a UDL-adapted curriculum, the framework will fail due to the increased pressures and frictions that arise from adopting different pedagogies too rapidly.

Undertaking this work required awareness of challenges within our specific Global South context. Not all students have access to technology or a home environment conducive to studying. Approaches that minimise educational inequality in a digitally-enabled education must be taken. The challenge of promoting equitable education is further exacerbated by the growing diversity of the student body and resource inequalities. In the South African HE sector, resource inequalities have been at the forefront of the discussion through movements such as #FeesMustFall and, even more recently, during emergency remote teaching because of the digital divide becoming even starker (Czerniewicz et al., 2020). For example, the cost of data in our context may prevent students from completing online learning activities such as quizzes and polls.

Another challenge we encountered was that while there was the intention to design courses that promoted accessibility and inclusion, there was room for improvement in the implementation of these guidelines in course design. Under the UDL principle of multiple means of action and expression, one checkpoint highlights the need to develop executive functions such as goal setting, strategy development and management of resources and information. This guideline is something we, as the ETA team, must consider. Hence, when designing courses on the LMS, the ETAs and broader learning design team included “checklists” on each lesson page so students could tick off tasks, and thus measure their progress through the course.

A significant challenge for one of our ETAs, who is visually impaired, was the lack of accessibility to build content on the LMS. The site is also often inaccessible for students depending on assistive devices for learning. Another challenge faced by one of the authors was lack of sufficient time to build a first-year archaeology site. This course focused heavily on the UDL principle of multiple means of action and expression, so there were many activities and exercises for the students to do. The setting up of these activities and exercises took a great deal of time because it required the creation of activity resources, such as images for the students to sort through. The setting up of such a course is highly beneficial for online students as it allows for options for physical action, and it is visually engaging. However, a total of three students registered for the course. While the content is valuable and can be reused in the future, it would have been more practical to design the course with fewer activities to suit a smaller class size, as some of the activities may have been better suited to a larger group of students. Our hope is that by identifying these challenges, barriers to inclusive education for all can be recognised and removed.

Principles of UDL to take forward in HE for good

In line with the core focus of this book, Higher Education for Good, we consider two questions in relation to our UDL project at UCT: What does learning for good look like? How could we re-imagine higher education futures for good?

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed multiple alternative teaching and learning futures. As a result of COVID-19 restrictions, universities had to adopt remote teaching strategies, which involved lecturers recording themselves teaching and adapting their teaching approaches and resources to be suitable for online use. The unanticipated pivot to remote online teaching and learning, at least in our UCT context, encouraged design approaches to accommodate different ways of knowledge being consumed and created.

However, these futures are still not yet realised, as we have gleaned through our dual roles as both students and ETAs. As we have discussed throughout this chapter, this process of transition between different teaching and learning modalities is difficult and uncomfortable. After teaching in-person on campus for many years, it was uncomfortable for lecturers who were being asked to teach online, often from their homes. It was uncomfortable for students who were trying to study and attend online lectures from home environments which may not be conducive to studying for several reasons. Also, it was uncomfortable because this shift to online learning requires more time, effort, and resources than the way teaching had traditionally been undertaken. Thus, a key theme that kept emerging when discussing our role was that of finding comfort in discomfort. How could we ease the discomfort during the transformation of pedagogical spaces such as the classroom?

We observed discomfort arise at many different intersections for students, teaching staff, and support staff. In addition to the personal toll of the pandemic, all these groups were experiencing heavy workloads, digital fatigue, and uncertainty — socially, economically, and politically. When considering teaching and learning futures, we must remember that “we cannot return to the world as it was before” (United Nations, 2020). The educational disruption caused by the pandemic has far-reaching consequences that we still do not fully understand. To prevent this crisis from causing further harm, it requires us to be resilient — not just as individuals, but systemically.

The United Nations (2020) highlighted the importance of building resilient education systems that can respond to immediate challenges but are also able to cope with unknown future crises. They emphasise that this can be made possible by focusing not just on access but also on inclusion and equity. To build resilient educational systems that can accommodate unforeseen changes, we need more than just technology. We need to share resources and teachings, reflect on past practices, consider how we can improve, and perhaps most importantly, we need to do all this with care and compassion. We are still at significant risk of creating a negative feedback loop of losing students through means of exclusion and a lack of accommodation.

So, how can we design and ensure alternative, inclusive, digitally enabled HE futures in which all students are encouraged and supported to reach their full learning potential? We have three recommendations, taken from our experiences, on how this future can be successfully achieved:

1. Student and faculty collaboration

An essential requirement under the UDL guideline of engagement is fostering community and collaboration. This does not simply apply to learners, but it applies to all involved in teaching and learning spaces. As ETAs, we can attest from our experience that the building of course sites is a collaborative task. There are many checks and balances in place when a course is being built. In our case, a course is usually built by an ETA who is supervised and assisted by a learning designer. Academic staff provide the content for the course and are there to offer feedback on the build and useability of the site. This process goes back and forth until both parties are happy. This whole process is overseen by a head learning designer who oversees the coordination of many courses within a discipline or faculty. Learning designers and educational technologists can teach lecturers how to engage students in online discussions to support learning. They can also collaborate with lecturers to determine how to best use technology for teaching and how to make the most of online/blended learning (Houlden & Veletsianos, 2020).

2. Focus on strategy, planning and resources for inclusive design

It is essential to remember that successful online education is not just about giving students information and expecting them to learn it. Ensuring that a digitally enabled education is accessible and inclusive requires careful planning and intelligent design. Such planning must take place at the conceptual level of course design to ensure that courses include rather than accommodate others into the learning process.

Based on our own experience, we found attending webinars and events about UDL and accessible education most valuable. This allowed us to learn from other educators and practitioners in the space about how they design and plan inclusive educational resources and content. Three of the authors of this chapter presented at a webinar panel titled “Promoting UDL principles and strategies for inclusive learning: The Redesigning Blended Courses Project at the University of Cape Town”, hosted by INCLUDE and UCT in September 2021. Presenting on this panel provided a platform for us as ETAs to share our experiences with others from different HE institutions in other parts of the world who were also trying to implement UDL in their settings. More importantly, this webinar allowed us to learn from other attendees and improved how we implement UDL. We also found attending other webinars hosted by other universities, such as the Digitally Enhanced Education Webinars from the University of Kent to be particularly useful. We also noted that when learning about educational strategies used in the Global North, some recommendations would have to be adapted to suit our local context in the Global South.

3. Share resources and strategies

Institutions of HE should prioritise internal departmental collaboration as well as external collaboration with other HE institutions. These collaborations will ensure that departments and institutions benefit from each other’s experiences. Within the CILT department, we hosted a weekly academic reading group which included both students and staff. These weekly sessions allowed for mutual learning and teaching between these two groups. These reading groups provided a forum for both groups to talk their way into and around scholarly topics, which allowed us to become familiar with discipline-specific terminology. As we were exposed to more literature, we were able to engage with various interpretations and approaches to educational pedagogy. Reading groups provide a great way for us to work with texts in the company of others, thus deepening our collective knowledge of scholarship on topics like UDL, social justice and blended learning, as well as (importantly) how we practise them (Thomson, 2021).

Furthermore, the integration of open education resources (OER) needs to be made an imperative. In collaborating and utilising OERs more readily, a practice of accessible information unhindered by physical and socioeconomic barriers becomes more of a reality (Butcher, 2015). These are beneficial strategies developed in one course. If these strategies could be shared with different departments at the university, others may benefit and ultimately help other students and teaching staff who may face a similar predicament.

Conclusion

The traditional pedagogical approach of “one-size-fits-all” cannot meet learner diversity in a contemporary academic milieu. As the student population in HE continues to diversify and the delivery of teaching changes (face-to-face, online, and blended), it is imperative to design curricula that effectively support and promote diversity and equity. UDL guidelines advocate for an inclusive instructional approach by minimising barriers and maximising learning for all students. University students can directly benefit from two major aspects of UDL: (a) its emphasis on a flexible curriculum and (b) the inclusion of a variety of instructional practices, materials, and learning activities. UDL is an educational framework that can effectively support university lecturers and learning designers in designing and developing curricula that are accessible to as many diverse learners as possible.

In this chapter, we have demonstrated as ETAs at UCT how design justice and UDL frameworks helped us to guide and support lecturers and learning designers as they attempt, during the COVID-19 pandemic and the overnight pivot, to untangle the social justice issues which surround online learning initiatives. We also have adopted decolonial theory as a lens to critically examine the practicability of UDL in shaping academic discourse from the Global South context. This contributes to the ongoing debates on transformation and inclusive pedagogies in the Global South. We conclude that UDL is a practical framework which can promote accessibility and include diversity if applied with a design justice lens. While the UDL framework cannot be treated as a catch-all solution to the challenges faced in HE institutions, especially those in the Global South, UDL has shown enough promise globally that it is likely to be a part of this solution. The use of UDL in a context in which its limitations and challenges are recognised will still provide means to create a truly equitable solution for the accessibility challenges within the Global South. Reflections within the Global South, like the experience of the authors of this chapter, have taken the theory of UDL and put it into practice. These provide a real way forward for UDL in the Global South and a new and more inclusive future of education. In doing so, we can start to ensure that the issue of education exclusion is less pronounced, and we move ever closer to true social justice.

Acknowledgements

Our chapter describes our experiences as Education Technology Advisors at the University of Cape Town, however, telling this story would not have been possible without the support of several key individuals. Firstly, a big thank you to the editors, Catherine and Laura for giving us the opportunity to be a part of this wonderful project. We are also most grateful to Nokthula Vilakati, Cheryl Hodgkinson-Williams, and the CILT team at UCT for their unwavering support. It has been incredible to be part of a broader project where young scholars such as ourselves are encouraged to contribute to the re-imagining of higher education futures with patience, kindness, and generosity. And lastly, thank you dear reader for wanting to re-imagine a different HE future alongside us.

References

Adam, T. (2020). Addressing injustices through MOOCs: A study among peri-urban, marginalised, South African youth [Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge].

https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.56608

Al-Azawei, A., Parslow, P., & Lundqvist, K. (2017). The effect of universal design for learning (UDL) application on e-learning acceptance: A structural equation model. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6), 54–87.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020969674

Almumen, H. A. (2020). Universal design for learning (UDL) across cultures: The application of UDL in Kuwaiti inclusive classrooms. Sage Open, 10(4).

https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i6.2880

Benton Kearney, D. (2022). Universal design for learning (UDL) for inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA). eCampus Ontario.

https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesign/

Boidin, C., Cohen, J., & Grosfoguel, R. (2012). Introduction: From university to pluriversity: A decolonial approach to the present crisis of western universities. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 10(1), 1.

https://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol10/iss1/2/

Boughey, C. (2012). Social inclusion & exclusion in a changing higher education environment. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 2(2), 133–51.

https://hipatiapress.com/hpjournals/index.php/remie/article/view/244

Brodkin, K., Morgen, S., & Hutchinson, J. (2011). Anthropology as white public space? American Anthropologist, 113(4), 545–56.

Butcher, N. (2015). A basic guide to open educational resources (OER). Commonwealth of Learning (COL).

https://doi.org/10.56059/11599/36

Cai, Q., & Robinson, D. (2021). Design, redesign, and continuous refinement of an online graduate course: A case study for implementing universal design for learning. Journal of Formative Design in Learning, 5(1), 16–26.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41686-020-00053-3

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2.

Cazden, C. B. (2012). A framework for social justice in education. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 1(3), 178–98.

https://hipatiapress.com/hpjournals/index.php/ijep/article/view/432

Chiwandire, D. (2019). Universal design for learning and disability inclusion in South African higher education curriculum. Alternation Special Edition, 27, 6–36.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. The MIT Press.

https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12255.001.0001

Czerniewicz, L., Agherdien, N., Badenhorst, J., Belluigi, D., Chambers, T., Chili, M. et al. (2020). A wake-up call: Equity, inequality and covid-19 emergency remote teaching and learning. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 946–67.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00187-4

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds: New ecologies for the twenty-first century. Duke University Press Books.

https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822371816

Ferguson, B. T., McKenzie, J., Dalton, E. M., & Lyner-Cleophas, M. (2019). Inclusion, universal design and universal design for learning in higher education: South Africa and the United States. African Journal of Disability, 8(1), 1–7.

https://ajod.org/index.php/ajod/article/view/519/1100

Fovet, F. (2020). Universal design for learning as a tool for inclusion in the higher education classroom: Tips for the next decade of implementation. Education Journal, 9(6), 163–72.

https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20200906.13

Fraser, N. (2000). Rethinking recognition. New left review, 3(3), 107–18.

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii3/articles/nancy-fraser-rethinking-recognition

Fraser, N. (2010). Injustice at intersecting scales: On “social exclusion” and the “global poor”. European Journal of Social Theory, 13(3), 363–71.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431010371758

Friedman, S. (1998). (Inter)disciplinarity and the question of the women’s studies PhD. Feminist Studies, 24(2), 301–25.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/10.2307/3178699

Grech, S. (2011). Recolonising debates or perpetuated coloniality? Decentring the spaces of disability, development and community in the Global South. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(1), 87–100.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.496198

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., Verstichele, M., & Andries, C. (2017). Higher education students with disabilities speaking out: Perceived barriers and opportunities of the universal design for learning framework. Disability & Society, 32(10), 1627–49.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1365695

Houlden, S., & Veletsianos, G. (2020, March 12). Coronavirus pushes universities to switch to online classes – but are they ready? The Conversation.

Karisa, A. (2022). Universal design for learning: not another slogan on the street of inclusive education. Disability & Society, 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2125792

Karr, V., Hayes, A., & Hayford, S. (2020). Inclusion of children with learning difficulties in literacy and numeracy in Ghana: A literature review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–15.

Keddie, A. (2012). Schooling and social justice through the lenses of Nancy Fraser. Critical Studies in Education, 53(3), 263–79.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2012.709185

Khalid, M. S., & Pedersen, M. J. L. (2016). Digital exclusion in higher education contexts: A systematic literature review. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, 614–21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.094

Kim, J. (2016). Locating Narrative Inquiry in the Interdisciplinary Context. In J. Kim, Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research (pp. 1–25). SAGE Publications, Inc.

https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781071802861

Lowrey, K. A., Hollingshead, A., & Howery, K. (2017). A closer look: Examining teachers’ language around UDL, inclusive classrooms, and intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(1), 15–24.

Luckett, K., & Shay, S. (2020). Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Critical Studies in Education, 61(1), 50–65.

Mackey, M. (2019). Accessing middle school social studies content through universal design for learning. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 9(1), 81–88.

Maree, J. G. (2015). Barriers to access to and success in higher education: Intervention guidelines. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(1), 390–411.

https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC172780

Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive [PDF]. Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

McKenzie, J., Karisa, A., Kahonde, C., & Tesni, S. (2021). Review of universal design for learning in low and middle-income countries. Including Disability in Education in Africa (IDEA).

McKenzie, J. A., & Dalton, E. M. (2020). Universal design for learning in inclusive education policy in South Africa. African Journal of Disability, 9.

https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v9i0.776

Miles, S. and Singal, N. (2010). The Education for All and inclusive education debate: Conflict, contradiction or opportunity? International Journal of Inclusive Education, Disability and the Global South, 14(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802265125

Munro, P. (1998). Subject to fiction: Women teachers’ life history narratives and the cultural politics of resistance. McGraw-Hill Education.

Ntombela, S. (2022). Reimagining South African higher education in response to covid-19 and ongoing exclusion of students with disabilities. Disability & Society, 37(3), 534–39.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.2004880

Olaussen, E. J., Heelan, A., & Knarlag, K. A. (2019). Universal Design for Learning–license to learn: A process for mapping a Universal Design for Learning process on to campus learning. In S. Braken, & K. Novak (Eds), Transforming higher education through Universal Design for Learning (pp. 11–32). Routledge.

Rao, K., & Torres, C. (2017). Supporting academic and affective learning processes for English language learners with universal design for learning. Tesol quarterly, 51(2), 460–72.

Reinders, M. B. (2019). Decolonial reconstruction: A framework for creating a ceaseless process of decolonising South African society. [LLM, University of Pretoria].

http://hdl.handle.net/2263/73485

Rose, D., Gravel, J. W., & Tucker-Smith, N. (2021). Cracks in the foundation personal reflections on the past and future of the UDL guidelines [PDF]. CAST.

Sayed, Y. (2003). Educational exclusion and inclusion: Key debates and issues. Perspectives in education, 21(3), 1–12.

https://digitalknowledge.cput.ac.za/handle/11189/5094

Small, J. (2020). Redesigning blended courses project. Center for innovation in learning and teaching.

http://www.cilt.uct.ac.za/cilt/projects/udl

Song, Y. (2017). To what extent is universal design for learning “universal”? A case study in township special needs schools in South Africa. Disability and the Global South, 3(1), 910–29.

https://disabilityglobalsouth.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/dgs-03-01-05.pdf

Staley, D. J., & Trinkle, D. A. (2011). The changing landscape of higher education. Educause Review, 46, 15–32.

https://er.educause.edu/articles/2011/2/the-changing-landscape-of-higher-education

Steyaert, J. (2005). Web-based higher education: The inclusion/exclusion paradox. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 23(1–2), 67–78.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J017v23n01_05

Thomson, P. (2021, 25 January). Reading groups/journal clubs are a good idea. Patter.

United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. United Nations.

Zhang, H., & Zhao, G. (2019). Universal design for learning in China. In S. L. Gronseth, & E. M. Dalton (Eds), Universal access through inclusive instructional design: International perspectives on UDL (pp. 68–75). Routledge.