Section I Finding Fortitude and Hope

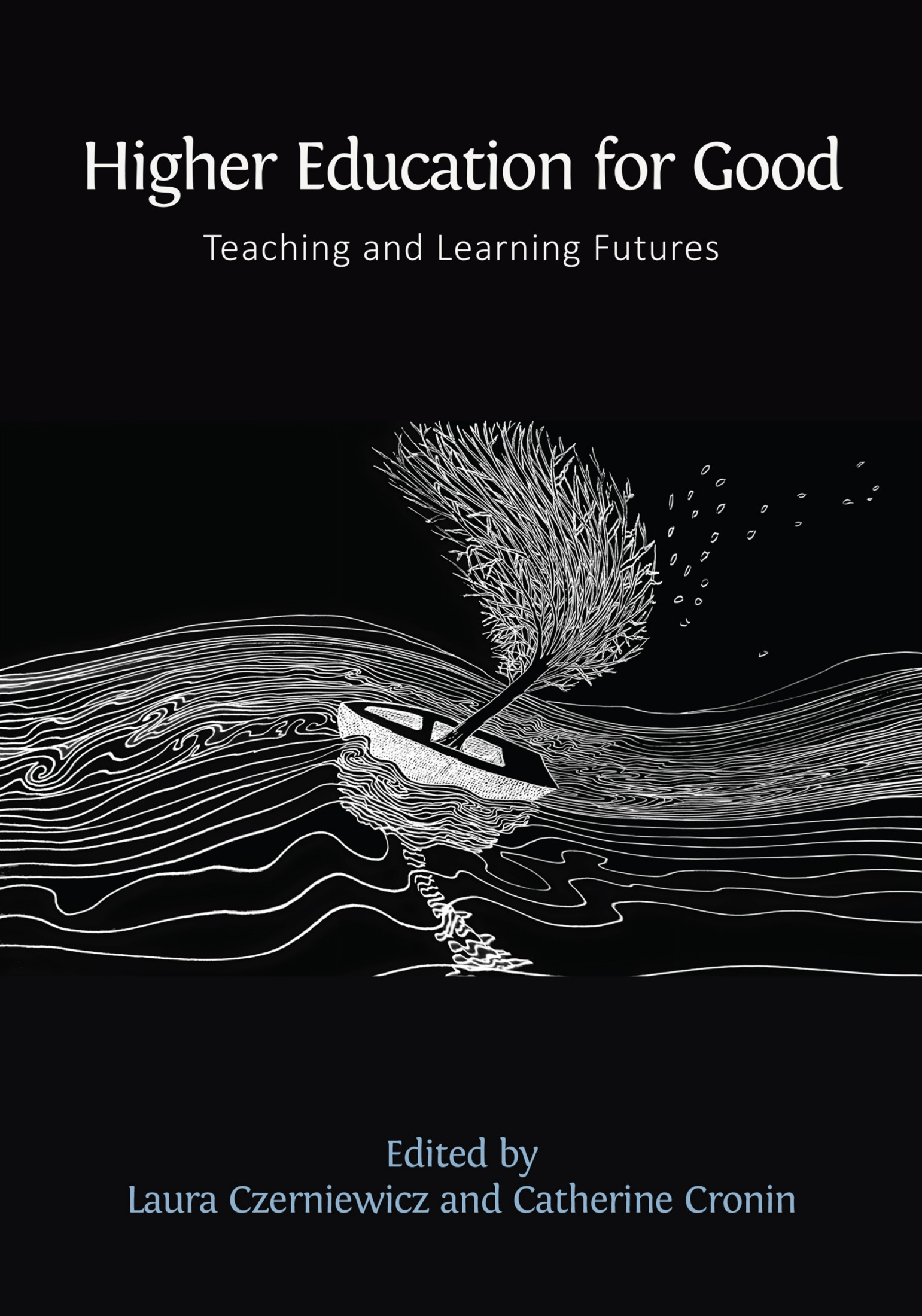

‘Hope’ by George Sfougaras (CC BY NC-ND)

Note from the artist

The print ‘Hope’ was inspired by the exodus of refugees and the images of people sailing across the Mediterranean from Turkey to the Greek islands. The news was and is saturated with shocking pictures of little boats and uprooted people, desperately seeking a better life, leaving all they had and all that sustained them behind.

Early on the day when the original idea was conceived, I was walking to my studio through Victoria Park in Leicester. The trees had shed their last autumnal leaves and stood in a bitter breeze which bent and swayed their thin branches. They stoically faced their circumstances in the hope of a new spring and new life. The image of the tree made me think of how hope survives and sustains us — even guides us — when we face insurmountable odds. The tree on the boat is a metaphor. The three components of the print, the boat, the tree, and the sea are simple and universally understood, but their juxtaposition makes us look again and reflect. The tree symbolises a person who has been displaced or uprooted and through life-changing events, forced to become a refugee. Anyone in that position cannot survive long without putting roots down somewhere. When they do, will they survive and thrive, create a meaningful life for themselves and their children, and bear fruit?

Every displaced person is sustained in their search for a better life through their hopes and dreams. For immigrant families, the education of the children was seen as the way to succeed in a new country. It was certainly the case for me, coming to the UK as an adolescent with basic English. I vividly recall wanting to master the language, to integrate and be seen as capable and competent in my school and later in the workplace. Having come to a rather insular and xenophobic 1970s England, I saw education as my way to demonstrate my capacity for hard work, but, more than that, to address the perceptions of ‘foreigners’ as less capable, less educated, less emotionally literate, and somehow less than. Higher education gave me a way to gain qualifications, which allowed me to progress and, in some ways, overcome the barriers of prejudice, at least professionally. Towards the end of my career as the head teacher of a school, I realised that the hope education gave me was still a powerful currency, and in my discussions with displaced or disenfranchised young people, I was able to turn to the hope that education offers, to escape difficult circumstances, and to create a better world through knowledge and insight.

On a deeply personal level, the image reminds me of my own family’s tortuous path to safety, when they escaped war and ethnic violence. My mother’s family followed a route from their home in Smyrna (Izmir) in 1922 to the island of Chios, which a century later is the same route taken by refugees from the Middle East and Asia. They rebuilt their lives in Greece, the ‘home’ country they had never seen. It seems that they were destined to uproot again, this time during the troubled Greek Junta period. History is, for all of us, a bigger part of our lives than we like to acknowledge.

Higher education for good

© 2023 Catherine Cronin and Laura Czerniewicz, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0363.28

“There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”1 This book is about the light in higher education, a sector that was already fragmenting and fragile before the pandemic began, and since then has been addressing and resisting foundational challenges. Rare are the academics and professionals who are not dispirited, even demoralised. In the face of such despair, it feels hard to know what to do, to believe that it is possible to do anything at all, or even to find the energy to act. Yet change is possible, both change responding to flaws in the sector and proactive change aiming to prioritise values that are just, humane, and globally sustainable.

Using the Igbo word “nkali” to describe power structures in the world, Adichie (2009) has persuasively explained how there is never a “single story”. A single story stereotypes and risks promoting a hegemonic universal discourse. A single story pretends that “one size fits all”. In this book, the reflections, analyses, and expression of principles in context mean multiple stories, in multiple realities, even within similar physical locations. The book is a commitment to the importance of context and intersectionality.

We co-editors, Laura and Catherine, are academics committed to social justice and open education. We are colleagues and we are friends. Together, in 2021, we chose to take a journey of radical hope; the result is this book.2 We consciously take inspiration from those fighting for justice globally — those who came before us and those whom we walk alongside, including the authors and artists in this book and the many scholars cited within it. At the start of this book project (in June 2021), each of us was employed full-time in higher education — Laura as professor of education at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and Catherine as digital and open education lead at Ireland’s National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. As this book goes to press, we occupy different professional positions as professor emerita and independent scholar, respectively, and remain as committed as ever to work which enacts the principles driving this book. The decision to seek answers regarding what higher education (HE) for good would look like, and what can be done, has been driven by our own experiences in a turbulent sector as well as by the global picture.

What to expect from this book

The chapters in Higher Education for Good: Teaching and Learning Futures offer ways of thinking, conceptualising, and creating real possibilities for making and remaking HE for good, with a particular but not sole focus on teaching and learning. Throughout the book is a vision of universities re/claiming their roles of “serving society as a change agent and empowering people across different sections of society” (Misra & Mishra, Ch. 25). Even to imagine such a move, let alone to lobby for and enact it, is to plant a sapling in our imagination: “And now that we have thought of it, it is already growing, and might yet come to be seen for miles” (Bowles, Ch. 15).

The book brings to fruition 27 chapters written by 71 authors in 17 countries.3 Authors include established academics and researchers, learning professionals, and early career scholars, as well as students, those in academic leadership positions, and educators working outside higher education but with valuable perspectives on it. Responding to our invitation to consider all forms of creative expression, including but extending beyond the usual academic genre, chapters are written in a variety of forms: critical reflections, conceptual essays, dialogues, speculative fiction, poetry (including haiku), graphic reflection, image, and audio. Each chapter was peer reviewed by at least one scholar external to the book project (see the list of external peer reviewers), and at least one fellow book author. Chapters directly related to teaching, learning and students were also reviewed by student reviewers.

In addition to these diverse chapters, we wanted to acknowledge the role of artists in “seeding resistance and providing the tools for us to imagine otherwise” (Davis et al., 2022, p. 8). Artwork relevant to the book’s themes is included in the book, together with reflections from the artists.

The book is organised into five sections, enabling readers to focus on particular areas of interest. Section I, Finding Fortitude and Hope, contains foundational ideas for the book, elucidating current dilemmas and looking to the future with conviction and hope. Section II, Making Sense of the Unknown and Emergent, offers a range of theoretical lenses and imaginaries by which we can make sense of and reconsider our present, unfolding dilemmas. In Section III, Considering Alternative Futures, authors offer various ways to vision and imagine better futures, as a step towards bringing such realities into being. Section IV, Making Change through Teaching, Assessment and Learning Design, contains a collection of diverse and creative ways that educators and students have used to make changes in the broad area of teaching and learning, with examples from HE sectors in eleven countries. Finally, the chapters in Section V, (Re)making HE Structures and Systems, take a broad view, describing ways to embed long-term change through systemic and structural changes at institutional and national levels.

Towards a manifesto for higher education for good

Considered together, the chapters and artwork in the book coalesce into an agenda for higher education for good that responds directly to our opening question, “What is to be done”? Overall, the book represents an invitation to hope, identifies avenues for thought and action, and provides inspiration towards a possible manifesto(s) for “higher education for good” which could be tailored to specific contexts. The book’s five tenets of action, inspiration, and hope are:

- Name and analyse the troubles of HE

- Challenge assumptions and resist hegemonies

- Make claims for just, humane, and globally sustainable HE

- Courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities

- Make positive changes, here and now

As we elaborate on each of these tenets below, we provide illustrative examples from the book. Most chapters exemplify several tenets, so these examples are far from exclusive.

Tenet One: Name and analyse the troubles of HE

Naming and analysing the troubling problems of HE are necessary in order to challenge and to change them: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” (Baldwin, 1962). Thus, a book about HE for good must inevitably begin by analysing “the bad”. As Fricker (2013) writes of studying injustice in her work on epistemic justice, the “negative imprint reveals the form of the positive value” (p. 1318).

The chapters in this book attest to the need to both confront the overt challenges and excavate the covert ones because, as Auerbach Jahajeeah (Ch. 8) contends, universities “take for granted and are taken for granted”. It is by “challenging, scrutinising, and problematising what seems natural and commonsensical” (Kuhn et al., Ch. 21) that a foundation can be laid for uncovering the troubles of HE and for illuminating the good which exists nevertheless. Undertaking this work requires a kind of “radical acceptance that the status quo is neither desirable nor acceptable… there is nothing that is ‘normal’ about current systems” (Childs et al., Ch. 13).

What are the troubles of higher education?

This book makes blindingly clear the damage wrought to higher education by the evolving permutations of neoliberalism, not only economically through continuous state underfunding but also politically and culturally through the transfer of free market thinking into educational practices and language. Almost all chapters begin with the consequences of neoliberalism in HE, the dominance of which is critiqued as being treated in a matter-of-fact way “as ahistorical, apolitical and value-neutral” (Hordatt Gentles, Ch. 20). DeRosa (Ch. 1) maps out in detail and in despair the particularities of the “pervasive austerity logic that constricts not just our budgets, but every facet of what we do”; Khoo (Ch. 3) emphasises that “neoliberalism continues to evolve its uncanny non-death… [that] broad and deep economic and sociopolitical crises have continued, spreading the slow violence of structural harm, inequity and precarity”.

Related to neoliberalism is coloniality, arguably two sides of the same coin. While colonialism is time and place bound, its logic endures in ongoing systems and practices, patterns, and structures of power premised on extraction and exploitation, echoing colonial forms of engagement. In higher education, coloniality is manifest in many ways including economically, culturally, and epistemologically. Coloniality persists “in the unjust politics of knowledge legitimation” which infiltrate the academy and the curriculum and indeed “creates absence where there is presence” (Mbembe in Belluigi, Ch. 5). A point affirmed by many authors, Belluigi explains why the decolonisation of knowledge is a critical endeavour for educators, academic developers, and learning professionals in terms of questioning knowledge formations of the self, the social, and the ecological in education.

Intrinsic to both neoliberalism and coloniality and threaded through many of the chapters are the risks of data extraction to students and academics through the business models of big tech companies which became particularly entrenched in the sector during the pandemic. In different ways, several chapters explore data extraction and sovereignty. Amiel and do Rozário Diniz (Ch. 18) address these risks through educators’ efforts to offer alternative practices and understandings of extractive platform logics. Scott and Gray (Ch. 27) make overt the hidden politics, ethics, considerations, and implications of software choices for teaching and learning. The urgency of data literacies and the need for data justice are articulated in several chapters.

Interwoven throughout are the many forms of inequity and levels of exclusion expressed in and contributed to by HE. Macgilchrist and Costello (Ch. 19) sum up how performance metrics generate hierarchical rankings of universities, amplifying uneven global access to essential infrastructure, while surveillance technologies disproportionately penalise students of colour and predictive analytics systems can block the paths of students whom the system predicts to be unlikely to succeed. Furthermore, digital education concerns mirror material realities where exclusions “such as perpetuated language barriers and ableism permeate the fabric of higher education… [and where] being unheard and underrepresented can cause students to feel alienated in their educational journey” (Ramparsad Banwari et al., Ch. 16).

Tenet Two: Challenge assumptions and resist hegemonies

Awareness and anger at the status quo can spur action and there are numerous examples in the book of both calls to and enactments of resistance. Khoo (Ch. 3) eloquently shows the power of “cursing the darkness” of colonial legacies in the sector, while also arguing that darkness can be “an interruption that serves to foster creativity and imagination”.

To change knowledge and understanding in the sector means centring and bringing in from the margins voices and views. It means intentionally crossing borders of all kinds: geographic, disciplinary, status and “accepted genre”. This may take effort, given how hegemonies in HE rest on socialisation and reward systems, but such efforts to move past acquired familiarity yield enrichment in the form of wider and deeper intellectual resources and insights. We concur that “there’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless’. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard” (Roy, 2004). We hope in our own way that this book, in form and content, demonstrates how knowledge is deepened for everyone when boundaries are crossed.

Challenging assumptions is both hard and possible. In their chapter on openness as a strategy against HE corporate capture and associated platform models, Amiel and do Rosário Diniz (Ch. 18) push back against the dominant Silicon Valley narratives of education, recounting their practical efforts to resist big tech’s extractive surveillance demands inside classrooms, and offer alternatives of both practice and thinking. And in her chapter employing a data justice perspective on the use of AI in higher education, Pechenkina (Ch. 9) provides frameworks which see “learners as leaders directing AI action within complex educational terrains”.

Several chapters are built on profound challenges to knowledge, economic, and cultural hegemonies; they affirm educator agency despite limited room to manoeuvre and the structural constraints outlined above. Attention is focused on “trying to disrupt the technical rationality that erodes our [educators’] capacity and confidence for professional autonomy” (Hordatt Gentles, Ch. 20). That disruption includes moves towards “care” and moves towards the “social”. It is the social that Fawns and Nieminen (Ch. 23) emphasise in their provocative conversation on assessment, explaining how “assessment for good means social, not just individual good… requir[ing] an epistemological shift from the measurement of individual competencies and abilities against known standards, to collective and communal ways of knowing”.

Tenet Three: Make claims for just, humane, and globally sustainable HE

Making legitimate and explicit claims to better futures is necessary, both to fuel resistance to dominant narratives and to inspire the production of new visions. A key element in resisting and moving beyond the status quo is to “stake claims to improving conditions and society” (Phoenix, 2022). Considered together, the chapters in HE4Good make specific and powerful claims for higher education that is just, humane, and globally sustainable.

One bias within large systems is to assume that stated good intentions (HEI mission statements advocating equity, diversity, and inclusion, for example) translate into good practice. More pernicious is the masking of bad practice with statements of commitment to laudable ideals. Forestalling or resisting this tendency towards diverse forms of “washing” (e.g. equity-washing, green-washing, open-washing) requires continual attention and the persistent assertion of values consonant with justice, humanity, and global sustainability in order to manifest these values in HE systems, structures, policies, and practices. This is as true at global, regional, and national levels as it is for individual higher education institutions.

Across the 27 diverse chapters in this book, all authors articulate specific values which could characterise “good” higher education in context. These include equity, justice (social, economic, environmental, epistemic, data, and design justice), sustainability, pluriversality, mutuality, generosity, creativity, and collectivism — all underpinned by ethics including affirmative ethics, relational ethics, environmental ethics, and ethics of care.

To further articulate these characteristics, authors draw on a wealth of theory and theory-informed practice to conceive of “good”. Authors describe different forms including moral and cultural goods (Fawns & Nieminen, Ch. 23) and “good” as grounded in different cosmologies/spiritualities centred on human interconnection and our “radical interdependence” with the earth (Chan et al., Ch. 4). Authors also interrogate various inter-related theoretical concepts such as public good, common good, social/societal good, and economic good; some seek to disentangle the concepts of public and common good.

For many scholars, “good’ means conceptualising different structures and governance for HE. Luke (Ch. 6) theorises the knowledge commons as the community of scholars that establishes rules and norms, managing the use, creation, and sharing of a common pool resource which is the intangible sum of human knowledge. He makes the case for universities as part of a polycentric network of smaller commons within the larger knowledge commons and for educators’ role as stewards of the knowledge pool. Wittel (Ch. 7) takes a Marxist perspective to argue for a higher education commons, explaining that it would provide the best context to foster higher education as a gift, emphasising that such a political economy can only be made sustainable in a post-capitalist world. He makes the case for the pedagogical principles of resonance, relevance, and imagination for educators to foster the gift. Furthermore, Chan et al. (Ch. 4) propose an alternative “communal-based exchange model” for HE to align with a “growing understanding of the importance of land-based pedagogy as practised by many Indigenous communities around the world, while calling for the validation of Indigenous knowledge, epistemology, and ontology within the hegemonic structure of higher education.”

Reconceptualising good requires an epistemological shift: a commitment to higher education for good means promoting a pluriversality of knowledge, embracing a horizontal strategy of openness to dialogue among different epistemic traditions, and addressing the underlying structures that prevent such transformation from taking place (Luckett & Shay, 2017; Mbembe, 2015).

The characteristics of good in higher education as explored in this volume align in many respects with Raewyn Connell’s (2019) five characteristics of the “good university”, i.e. democratic, engaged, truthful, creative, and sustainable.4 In addition, there is agreement that “goodness” is both relational and contextual, deeply interwoven with our ideological, political, and social realities. As Auerbach Jahajeeah (Ch. 8) expresses in her inspiring haikus:

pursuit of a good

that the good does not

rest in the tables

of university ranks

or the shininess

of lecture theatres.

rather the good nestles in

amongst between us

Making claims to better HE futures is essential, helping not just to sustain resistance but also to articulate narratives of hope and inspire new visions.

Tenet Four: Courageously imagine and share fresh possibilities

In a time when previously anticipated HE futures may be fading and new futures are projected by technocorporate actors committed to profit-making, we in higher education are called to imagine alternatives. As Davis et al. (2022) wrote of the brilliant Octavia Butler: “we will dream our way out; we must imagine beyond the given” (p. 16). Treating the future as a site of “radical possibility” (Facer, 2016), we can bravely imagine and share fresh possibilities and alternative HE futures, beyond existing realities and hegemonic discourses.

In our call for chapters for this book, we invited all contributors to share “glimmers of alternative futures” of higher education for good. This requires grappling with the future in ways that keep possibilities open rather than closing them down. We are compelled to ask, for example: What alternative visions of HE would prioritise dignity, wellbeing, and flourishing for all who are engaged with HE? What alternative visions of HE would extend possibilities for all who are currently excluded, particularly marginalised individuals and communities? What alternative visions of HE would hold and extend possibilities for future generations and for our planet?

One approach to addressing these complex questions is to use speculative methods for researching, analysing, designing, and teaching, i.e. asking “what if” instead of “what is”. Speculative approaches enable working with the future as a space of uncertainty, collaborative and creative imagining/reimagining, deepening our understanding of the present, and bringing capacious realities into being (Houlden & Veletsianos, 2022; Ross, 2022). Authors of three chapters in the book detail their use of speculative approaches. Macgilchrist and Costello (Ch. 19) describe using Africanfuturist speculative fiction (Okorafor, 2019) to invite students to imagine a university far beyond contemporary colonialist institutions, intentionally opening generative spaces “for students and lecturers to reflect on their (our) own positions in the academy, to critique the reproduction of classed, raced, gendered inequities in higher education… and to generate futures that are oriented to justice”. Childs et al. (Ch. 13) used a speculative scenario to evoke responses from colleagues with very different roles in higher education, and Flynn et al. (Ch. 14) invited students to write their own speculative imaginaries of HE futures.

Audre Lorde (1984) wrote that poetry is “the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought” (p. 37). Two authors used the medium of poetry to “name the nameless”, unsettling both what and how we think and talk about HE. Spelic (Ch. 2) offers a collection of five short, powerful poems, preceded by a short meditation on hope. Auerbach Jahajeeah (Ch. 8) explores the present and possible futures of HE in a dramatically different form: the haiku, supported by extensive footnotes. Other authors used different imaginative forms to invite readers to “imagine beyond the given” (Davis et al., 2022). Corti and Nerantzi’s chapter (Ch. 11), in the form of a landscape photograph, audio podcast and transcript, invites readers (and potentially educators and students) to “see the higher education landscape with fresh eyes” and to imagine alternative futures themselves. Trowler (Ch. 26) uses the format of a graphic reflection to give voice to “non-traditional students’” views of what “good” education looks like.

What counts as a fresh possibility is shaped by context. Some changes may seem small from the outside, or already accepted practice in a different context, yet revolutionary in a particular environment. At the same time, HE hegemonies mean that educators everywhere are weighed down by similar pressures and their imaginative interventions are of universal interest. This book is awash with extraordinary examples, offering fresh approaches, practices, and ways of thinking in a variety of contexts. Ramparsad Banwari et al. (Ch. 16) critically analyse and apply a universal design for learning (UDL) approach to course design in South Africa. They highlight how social and design justice can be attained by expanding conceptions of access and equity to explicitly address “barriers that are faced by students who have been excluded, marginalised, or diminished because of their skin colour, language, ethnicity, gender, and/or sexual orientation”. Molloy and Thomson (Ch. 17), from their standpoints as learning designers in Irish/UK universities, explain how aspirational values are implemented in the work of learning designers who offer “good help” in ways that are generative, iterative, and positive, guiding towards achievement in small steps and eventually leading to “transformational changes”. These and other examples of locally grounded work provide insights into their unique contexts, as well as bringing new insights, inspiration, and avenues for change-making to other HE contexts.

Tenet Five: Make positive change, here and now

An overriding message across all chapters in this book is that change is indeed possible, and that now is the time. The chorus of voices in this book only amplifies de Sousa Santos’s (2012) invocation: “In my mind we are at a juncture which our complexity scientists would characterise as a situation of bifurcation. Minimal movements in one or other direction may produce major and irreversible changes. Such is the magnitude of our responsibility” (p. 12).

Change means looking to the past as well as to the future. Moving forward often requires taking care to repair the past in meaningful ways. Exploitations of the past live on in the present and universities are complicit, criticised for perpetuating past injustices and for failing to address colonial and apartheid pasts (Makoe, Ch. 12). In HE locations such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, for example, acknowledging the past means acknowledging the land stolen from Indigenous peoples for universities to be built. Important steps to heal the past can be taken in different ways. Change can take the form of redress, moving beyond “sitting on our hands” to think practically about “back rent” (Bowles, Ch. 15). Indeed, Connell (2019), the author of the afterword of this book, has made practical suggestions for taxes to be paid to developing countries for the “international” students who bolster the coffers of universities in the Global North (as Bowles points out).

Making change also means recognising that streams become rivers: small changes matter and genuine change is possible. In this book are many examples of seemingly small changes, having affected one individual, one class, or one course. Hordatt Gentles (Ch. 20) describes a conscious decision to adopt a pedagogy of care in her teaching. Kuhn et al. (Ch. 21) describe a class studying social change who made and shared lists of indigenous trees in English, Swahili, and other local languages. Small changes can be contagious and inspiring; they can have ripple effects, in both intended and unintended ways, oftentimes unknown. The students who developed lists of trees shared openly decided to plant trees in the community around the university, making impossible-to-measure changes to university-community relationships and indeed to climate change mitigation. Work done locally can have huge consequences, “no matter how far we think we are from each other and how different from the ‘other’, we are all very intimately interconnected” (Gebru, 2022).

Large-scale changes can grow from a multitude of small changes and can also happen in both planned and unplanned ways. Indeed, as Wittel (Ch. 7) points out so aptly: “The most astonishing realisation about changes due to lockdown was the fact that many well-established procedures could not only be changed, but they could also be changed with lightning speed. Furthermore, these changes all handed over power to university teachers, or more precisely, the changes handed power back to university teachers.”

Planned large-scale changes are complex, as Arinto et al. (Ch. 24) show, using the framework of an ecology with biotic and abiotic nodes and components to illustrate the intentional design of a national and very diverse HE sector, requiring several modalities across 7,000 islands and 182 ethnolinguistic groups. Misra and Mishra (Ch. 25) explore specific challenges within a national higher education sector, outlining specific recommendations towards making (or remaking) HEIs as open knowledge institutions (OKIs).

Effective progressive change is strengthened by communality, the condition of belonging to a community, the condition of being communal. It is most powerful when forged through coalition. After all, “it is in the many acts, small and large, acting in constellations and collectivities, over time and place that bear results” (Sultana, 2022).

Calls for and enactments of community and coalition are rich threads through the book, with authors writing of the importance of engaging collectively, in partnership, in communities of practice, in prosocial communities, in open communities, and in networks — within HEIs, across HEIs, between HEIs and wider communities, beyond HEIs, and across borders of all kinds. The work of creating this book has been a communal and border-crossing act. In seeking to share diverse perspectives, in every sense, and to affirm openness in the process, we have taken inspiration from Mounzer (2016): “The only way to make borders meaningless is to keep insisting on crossing them… For when you cross a border, you are not only affirming its permeability, but also changing the landscape on both sides”.

Manifesting communal change is not easy in cultures that reward individualism and competition, yet such change is possible. For example, Fabian et al. (Ch. 22) describe a complex university project that entailed an intentional effort to create something that none of the seven organisations involved could have achieved alone, resulting in a “way of working together… which centred on principles of mutual respect and trust, of valuing each other’s knowledge and expertise, of collaborative working practices and consensus-based decision making”. In writing of the FemEdTech Quilt project as a communal activity, Bell et al. (Ch. 10) draw on Braidotti’s (2022) work on posthuman feminism, espousing affirmative ethics “stressing diversity while asserting that we are in this posthuman convergence together” and relational ethics “assum[ing] one cares enough to minimise the fractures and seek for generative alliances” (p. 237). Communal change in HE, though often exceptionally challenging, can bring unique rewards: “The process of becoming, exemplified by both the quilts and the FemEdTech network, has been a sustaining joyful practice of what happens in the spaces of coming-together (care, joy, hope, awe) in the face of crisis and the pressure of advanced capitalism” (Bell et al.).

Dwelling in hope

The delineation of the five tenets listed above does not imply a sequence or flow, any idea of completion, or even a single manifesto. Rather, the contributors to this book, individually and together as a diverse chorus, offer ways forward towards “good” higher education through imagination, openness, heart, and hope.

As the traditional saying goes: the best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago, the second-best time is now. Through its ideas, this book seeds many trees in both fertile and seemingly barren soil; they will grow through commitment and hope.

In our work and thinking, prior to and during the process of editing this book, we have been inspired by numerous perspectives on and analyses of hope — practical, critical, radical, epistemic, and existential hope (Butler, 2000; Facer, 2016; Freire, 1994; Ojala, 2017; Schwittay, 2021; Solnit & Lutunatabua, 2023). We conclude, however, with our own understanding of hope, galvanised by the contributors to this book and specific to the work of (re)making higher education for good.

Hope is firmly rooted in the belief that it is never too late.

Hope is practical. It means taking action, being disciplined, making plans.

Hope is impractical. It means dreaming, being undisciplined, being open-ended.

Hope is strengthened when practised in solidarity with others. It means building and strengthening alliances, coalitions, communities.

Hope is contested and contradictory. And yet whatever its form, it is essential.

Without hope, there would be no future worth living.

Depending on the challenges, the context, the timing, the resources available, and the will of all involved, the creative and critical work of building a just, humane, and globally sustainable higher education is always beginning — as beautifully expressed in one of Sherri Spelic’s poems (Ch. 2):

If my students and I build anything at all

a nation of acceptance

We are never done

and always beginning.

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009). The danger of a single story [Video]. TED Conferences.

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

Baldwin, J. (1962, January 14). As much truth as one can bear. The New York Times.

Braidotti, R. (2022). Posthuman feminism. Polity.

Butler, O. E. (2000). A few rules for predicting the future. Essence, 31(1), 165.

https://commongood.cc/reader/a-few-rules-for-predicting-the-future-by-octavia-e-butler/

Connell, R. (2019). The good university: What universities actually do and why it’s time for radical change. Zed Books.

Davis. A. Y., Dent, G., Meiners, E. R., & Richie, B. E. (2022). Abolition. Feminism. Now. Hamish Hamilton.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2012). The university at a crossroads. Human Architecture: Journal of Self-Knowledge, X(1), 7–16.

https://www.boaventuradesousasantos.pt/media/University%20at%20crossroads_HumanArchitecture2011.pdf

Facer, K. (2016). Using the future in education: Creating space for openness, hope and novelty. In H. E. Lees, & N. Noddings (Eds), The Palgrave international handbook of alternative education (pp. 63–78). Palgrave McMillan.

https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-41291-1_5

Freire, P. (1994). Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing. (Original work published in 1970.)

Fricker, M. (2013). Epistemic justice as a condition of political freedom? Synthese, 190, 1317–1332.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-012-0227-3

Gebru, T. (2022, May 26). Timnit Gebru to UC Berkeley graduates: Work collectively for a better future for all. Berkeley School of Information.

Houlden, S., & Veletsianos, G. (2022). Impossible dreaming: On speculative education fiction and hopeful learning futures. Postdigital Science and Education, 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00348-7

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press.

Luckett, K., & Shay, S. (2020). Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Critical Studies in Education, 61(1), 50–65.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2017.1356341

Mbembe, A. (2015, n.d). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive [PDF]. The Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Mounzer, L. (2016, October 6). War in translation: Giving voice to the women of Syria. Literary Hub.

https://lithub.com/war-in-translation-giving-voice-to-the-women-of-syria/

Ojala, M. (2017). Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures, 94, 76–84.

Okorafor, N. (2015). Binti. Tor Books.

Phoenix, A. (2022). (Re)inspiring narratives of resistance: COVID-19, racisms and narratives of hope. Social Sciences, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100470

Ross, J. (2022). Digital futures for learning: Speculative methods and pedagogies. Taylor & Francis.

Roy, A. (2004, November 8). The 2004 Sydney peace prize lecture [Video]. University of Sydney.

https://sydneypeacefoundation.org.au/peace-prize-recipients/2004-arundhati-roy/

Schwittay, A. (2021). Creative universities: Reimagining education for global challenges and alternative futures. Policy Press.

Solnit, R., & Lutunatabua, T. Y. (Eds), (2023). Not too late: Changing the climate story from despair to possibility. Haymarket Books.

Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography, 99.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

1 Cohen, L. (1992). Anthem [Song]. On The Future. Columbia.

2 We share the frustrations of many of the authors of this book with the limitations of ordering author names which don’t allow for the representation of genuine collaboration. This chapter — and this book — is forged in trust and mutual overlays of writing and editing. We “resolved” this conundrum by alternating authorship order for book and chapter.

3 Adding the peer reviewers brings the number of countries to 26.

4 See Raewyn Connell’s afterword in this book.