5. Modelling Text: A Case Study131

© 2023 Arianna Ciula et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0369.05

5.1 “Let’s Talk about Text”

In this book, we talk about models and the process of modelling in a Digital Humanities (DH) (and that is an interdisciplinary) setting. Observation, description, analysis, and generalisation are some of the methods we have used to reflect on modelling and its practices. To a certain extent, a meta-analysis has to be detached from the deeper discussion of single, concrete models. This tension entails the problem of how to bind the theory work back to the actuality of models. In the previous chapters, we used several examples to explain and illustrate different approaches. But how can we demonstrate that our approach can be observed in models in and modelling of a certain domain in itself? How can we derive theoretical assumptions from the variance of models that concern a common object of study? How can we add a more empirical layer to our research? In contrast to our discursive approach towards modelling, in this chapter we present a limited case study that focuses on examples of models around an arguably singular modelling target: text. Only indirectly does this refer to the modelling process itself. This book has the subtitle “Thinking in Practice”. That practice in DH and other fields can mean different things: most of all the practice of developing models by analysing modelling targets and evaluating the applicability of these models for some purpose (like research). This fundamentally iterative process usually does not start from scratch. Rather, it is based on the study of other already existing and established models which have been created in the same or a neighbouring field. The practice of modelling is also a practice of identification and examination of other models as starting points for the particular modelling endeavour as well as points of reference and parts of the terminological and conceptual discourse.

Models are everywhere. In our daily life as well as in all scientific and scholarly domains.132 With our point of departure in DH, which has traditionally focused on text-based studies, it is natural to start with text itself. ‘Text’ as an object of study and as a case for modelling is particularly interesting and suited for our purposes because text is (or texts are) a central matter in many scholarly and scientific disciplines as well as a commodity or something that is just used and processed in various fields (see Section 3.2.1 on this). Even disciplines studying other media types, such as art history or musicology, use text as a major tool for describing objects of study, analysing evidence, recording knowledge and publishing results. Indeed, even in research with a focus on non-textual objects, texts are still an important, sometimes dominant, part of what is actually studied or presented. This prevalent focus on texts allows for the observation of interdisciplinary perspectives on text, as well as of different appropriations of (the concept of) text. ‘Text’ is not only seen very differently in the various academic disciplines but also in their diachronic or isochronic partitions which are often referred to as schools or turns. Text is also handled very differently as an object of study (text as a cultural phenomenon to be observed), as textual content (e.g., linguistic code) or as a tool and technology (text as media). Since the late twentieth century, concepts of ‘text’ and ‘reading’ in some disciplines have even left their original scope of oral or written utterances and eventually been expanded to refer to all sorts of cultural objects—to finally end up with the broadest possible: “culture as text”.133

As we pointed out in this book, in the DH research context, text has been one of the most common objects of modelling activities. Thus, by starting here, we can offer a basis for a wider perspective on how modelling can give us insights into the complex shapes, forms, and the ontological status of text, and thus, on the opportunities and limitations of a model-based approach to studies in the humanities.

‘Let’s talk about text’. Nearly everybody (at least in academia) seems to talk about text. Or the other way round: nobody talks about text but everybody ‘has text’. And nobody talks without text. At least everybody uses text(s). Therefore, everybody must have an idea of what text is. However, beyond the ‘natural’ treatment or use of text, even if people talk explicitly about text (as a phenomenon), in most cases they do not provide well-structured, formal or definitive definitions of text that could serve as models. Depending on the notion of model, some may say that—until today—there is no definitive model of text at all. Others may claim the reverse: that in every talk about text that is research-oriented and even in every practice of working with text (by description, representation, analysis, processing etc.), there must at least be an implicit model of text. Otherwise, one could not work with text in a rational and intersubjective manner. If that is true, then there are very many text models around. Yet, since they are implicit, it is hard to tell precisely what they are and how they differ from each other.

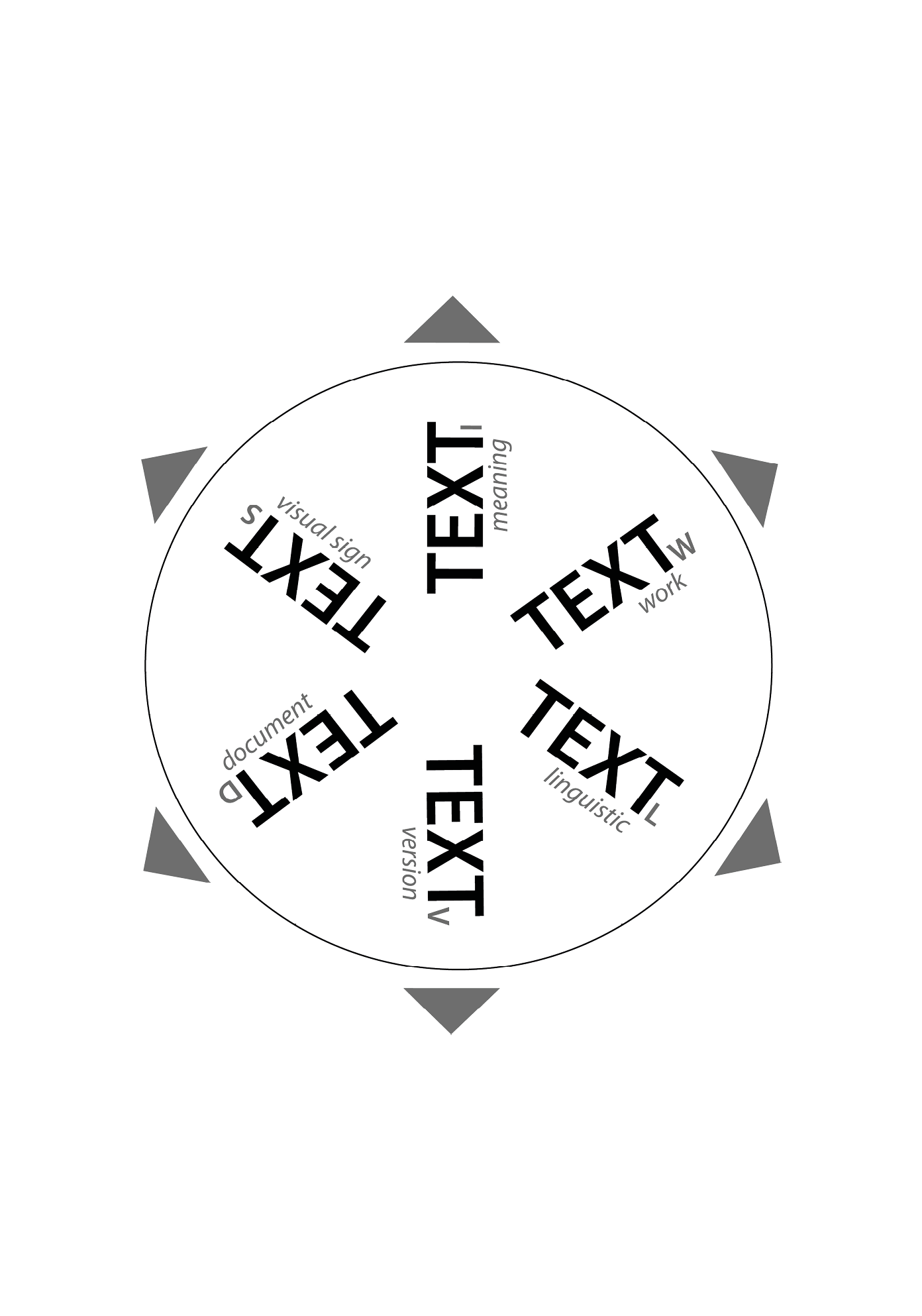

The nature of a thing determines what can be modelled as properties of that thing. But the perceived nature itself is shaped by the model that we have; properties are identified within the model through the act of modelling (cf. Chapters 2 and 3 of this book). Maybe objects only have these properties once they are declared in a model. One of the strange basic characteristics that text shares with other media objects is its ontological status as an abstract object that is always bound to physical items, as discussed in Section 4.5. In fact, the notions of text that we encounter cover a wide range of views on scales constituted by abstract versus concrete, idealistic versus materialistic, content versus form and other similar conceptual pairs. These rather dichotomising frames of investigation have already generated much heated debate and deserve further diligent differentiation. The basic recurring question in debates on ‘text’ regarding the nature of the relationships between an abstract object and its material basis is seen in many other modelling domains as well, and pulls us into underlying philosophical reflections. The simple question of whether text is the script that conveys a message or whether text is the message that is conveyed by some document can easily be debunked as too naïve and not very productive. The extreme positions of pure materialism or Platonism in themselves cannot lead to convincing models that would be useful in describing the phenomenon of text or lead to tools for working with texts. This is why the notion of purely material or purely conceptual things is much less productive in a DH context than possible layers in between, and the relations and translations between observable and describable properties of these layers.

Text as a target for modelling shows further interesting aspects, including the differences between and the duality of models of and models for. Sometimes, for instance in cultural history, a description of a text becomes a model of an observable thing in the real world. But in other domains models are built to decode, encode, represent or re-medialise text (as a category) or to make text treatable and processable as a proxy or resource for the analysis of other phenomena such as language, information, or communication. Therefore, some models are descriptive while others are oriented towards the realisation of media processes or the operationalisation of research agendas, or else they describe such operationalisations. Interests in text, and in models derived and deduced from such interests, mostly focus either on the genesis and production as well as reproduction of text, or the reception (including interpretation, understanding and processing) of text. Very few models cover more than one of these perspectives, and it is equally uncommon to explicitly refer to or integrate other models even from the same domain, let alone from other domains. Thus we clearly see the limitations of disciplinarity and purpose-driven investigations (see also Chapter 1 on this). This begs questions about relations, intersections, and the possibilities for overarching approaches. As text is probably the most important interdisciplinary information resource in scholarship and science as well as in our daily interactions, meta-models integrating the different particular views should help in stabilising a common ground for the understanding and employment of textual resources in a world that is increasingly integrated via the ubiquitous availability and reusability of data. Collecting and comparing the many models of text out there makes it clear how models of a certain object or in a certain domain are not able to, or even meant to reach the larger goal of a comprehensive representation and understanding. They are not developed in broader consensus across the single views of different persons, groups, or disciplines, and not developed in a coordinated process. Rather, they have emerged from certain specific fields of interest and application, leading to a significant diversity of model types. While this is normal for our specialised research fields, disciplines and subdisciplines, we (at least in the field of DH) also need more generalised models. With these, we pursue operational as well as non-operational goals: operational because models have to function in an interdisciplinary research agenda, non-operational because we aim to arrive at a deeper understanding of the meaning of — in this case — text. As we have argued throughout the book, these goals are inextricable: the epistemology of modelling is linked to the practice of building models. The examples here are presented with the dual aim of showing the underlying diversity we have described and also pointing towards a possibility for creating more integrative and general meta-models that may relate and map the more specialised models.134

Often, ‘text’ is also discussed in scholarship without any claim of presenting a theory or model of precisely what ‘text’ is. Still, we assume that one will already have some implicit understanding of text which can in principle be made more explicit. On these processes, from conceptualisations to mental models, see also Section 2.1.135 In many cases, texts about text are long and complex. Elaborate, sophisticated and differentiated. In this case study we aim to make them comparable, to find connections and differences, and to build bridges. Thus, in translating them into graphical forms of expression, we narrow them down. We select, we extract, we simplify, often quite brutally. The excerpts and the choices are ours! Many readers will disagree with our view on the texts about ‘text’ that we study; some of which are already canonical. Our goal is not so much to do justice to the full depth of the authors’ thoughts and expressions, but rather to create visual versions that (in future work) can be used to establish more general meta-models. This anthology approach can also illustrate a methodology for the development of meta-models.

In some cases, authors already provide visualisations of their own models. How these visualisations relate to their ideas, usually given in primarily textual form, that is, how authors express their ideas additionally through visual representations, is another interesting field of research. In Chapter 1, we talked about a new language for modelling. This refers to the concepts, the terms, and the words we use. But this may as well refer to the visual language of the diagrams that express models. Up to now, we must assume that the process of translation and explanation from verbal to visual in the literature we deal with is largely free of method and theory. Most of the authors we cite are highly skilled at expressing complex ideas through written language. Most of them will not have studied, for example, Bertin (1967)136 and his fundamental work on diagrammatical design, and are probably not systematically and formally trained in information visualisation and design. Nor are we.

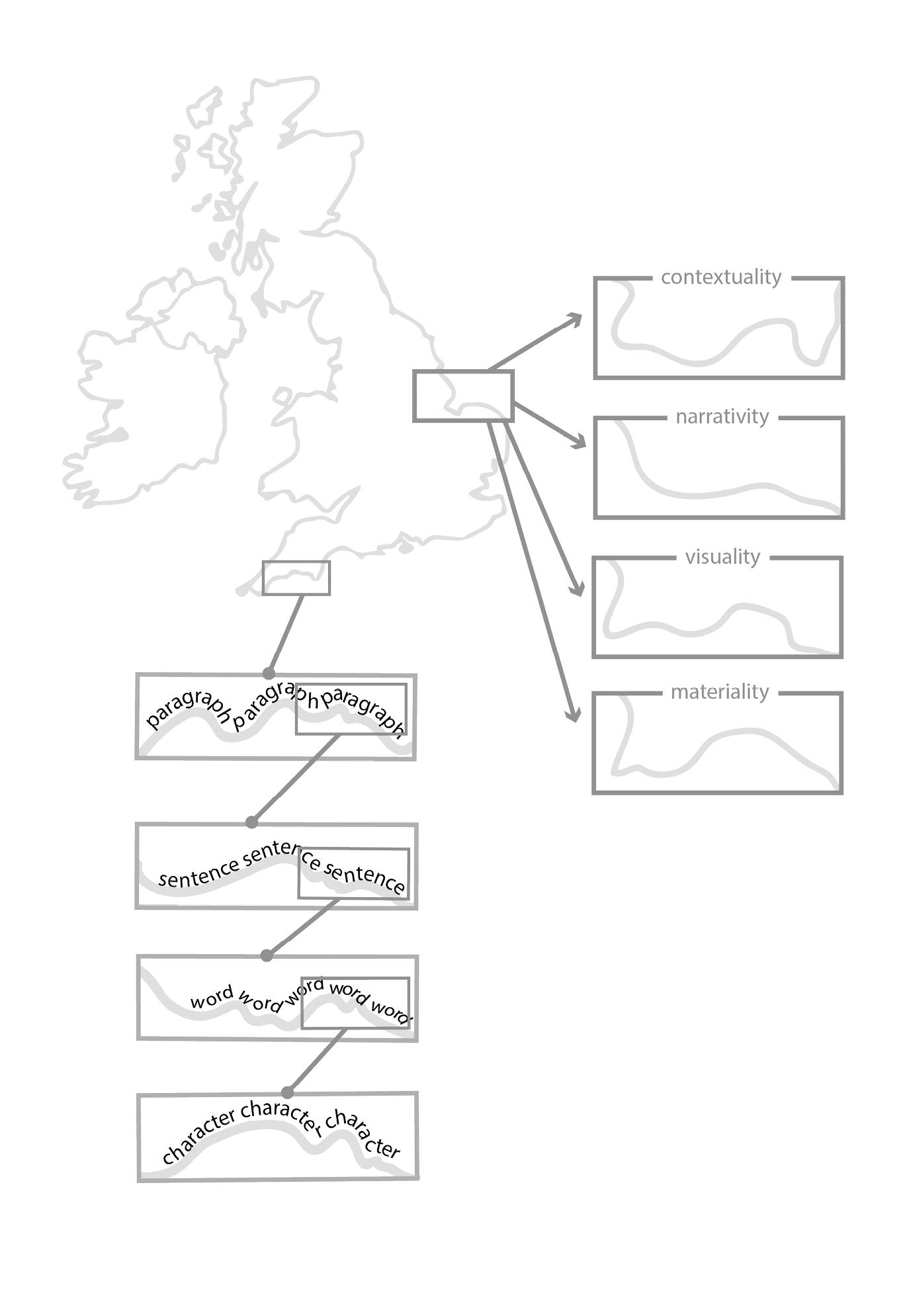

Where authors have included their own visual expression, we have used these. Sometimes we have slightly adapted them to make them fit more appropriately into the format of this book, or we have merged more than one visual expression from the same author. In the majority of cases, however, visual expressions have been created by us based on our own reading and interpretation. They are our graphical expressions of what an author wrote. In intermedia studies, media transformation processes are studied. In transformative digital intermedia studies, media transformation processes are performed, as outlined in Section 4.5. In our visualisations, we also do the latter. Sometimes the authors’ verbal models already use a metaphorical language (see Chapter 2.1 on this) that suggests an obvious imagery – as with McGann’s “coast of England” or Wenzel’s “frozen language”. But more often, we have simply created drawings that show our understanding of what authors have expressed in their texts, translating from the verbal to the visual. In doing this, we show the specific medialities of modelling languages and in particular their intermediality (as discussed in Chapter 4). At first, models seem to be “abstract” or purely structural by nature. Still, they always come in some kind of notation and take some kind of form. And these forms, which are languages of expression, vary widely. In the end, formulas, structure diagrams, metaphorical sketches, drawings, narrative texts are always media products (cf. Section 4.1) – how else could models be communicated?

Recalling the approach towards modelling sketched by Gooding (2003) and re-visualised by us in Section 3.3.2, the examples collected here are mainly about the reduction phases in modelling. In our integrative process of collection and visualisation we use the freedom of subjective judgement and visual interpretation to clarify and strengthen the intersections between the different models. In an idealised understanding of our procedure, we unpack the core concepts as they are expressed through the terms used, as well as through the inherent structures and relations in the single models. In this way, parts of certain models reoccur and overlap, paving the way for a broadening of the modelling process and for more comprehensive overarching meta-models. The development of these meta-models is not grounded in a traditional scholarly discourse, in the exchange and weighing of arguments, which would be expressed in the verbal and narrative modes of academic publications. Rather, they are, at least until now, the results of the creative, visual and conceptual synopsis of the many single models at hand. They are also a skilled activity made possible by many years studying and questioning what ‘text’ really is. They emerge from visual thinking in integrative meta-modelling.

What we present here is a first licentious ‘florilegium’. The examples are taken from well-known texts but they could have been chosen differently. There are of course many more implicit and explicit models of text out there. In fact, this compilation is already a selection of a wider collection with further examples that did not make it into the book. Some of our examples are obvious candidates and stand for central and important approaches (such as linguistics as a discipline, FRBR as a fundamental bibliographic ontology or ASCII as a technical format) although even here, the choice of which reference work to use can be disputed. Others are more randomly sampled to show the breadth of the field and the multitude of perspectives and approaches. The compilation might be developed further in the future as there are many more models to be considered.

This chapter is intended to facilitate research into modelling practice in mixed textual-visual forms of expression. We provide basic exemplary material and make a first attempt, mostly abstaining from analysis. We do not really question the nature, the peculiarities, or develop a scholarly system for the relationships between text and visual forms. We do not dwell on the different grades of iconicity of the selected graphical models. We do not categorise or systematise the very different forms of graphical expressions which span from table to diagram, and from formal notation to drawing. We do not systematically analyse the terms used in the models either, and we do not explicitly unpack the implicit assumptions and connotations of specific words. In this sense, our approach is rather on the playful side. Based on some experience in modelling, as well as on studies of ‘text’ in various forms, but without a stringent methodology, we pick up central words, relations and structures and turn our understanding into some visual expressions. We do this within a formal spatial frame by following a basic typographic rule: each model has to fit an open double page. We take one page for the model as a text–usually represented by a quote, a short summary or a comment–and its bibliographic reference, and one page for each model as a visualisation. With this we do not do justice to the authors and their models. We do not give full accounts of what has been said, we do not situate the models in their historical or disciplinary contexts, we do not talk about the process by which they were shaped on the path from intuitive starting points to sometimes highly elaborated models. Instead, we re-create and re-present these models, simplified and based on our aims for this specific study. We select and extract ‘verbal icons’ from the texts.

In most cases, these are central quotes from well-known texts. Sometimes it is quite difficult to find an appropriate span of text. Sometimes we give short comments on the quotes; explanatory, contextualising or as a starting point for some sort of dialogue. Sometimes, when we do not have an indicative quote, the comment is all we provide. In some cases, a relevant position for which there is not a single most acknowledged publication, we present it with our own summary statement. As we usually use authors and texts as witnesses for particular standpoints, and as the visualisations discuss bibliographic items, we give the full references on the respective pages instead of compiling them in a common bibliography.

The use case presented here is a random anthology of very different types of visualisations. They range from cartoon-like drawings to info-graphic-like illustrations to formalised diagrams and formulas.137 We try to illuminate a spectrum of media modalities (Section 4.2) within the range of affordances and limitations of the printed page. We do not address the question of relations between texts and visualisations explicitly, so we do not deal with the nature and properties of these visualisations in a systematic way. Nor do we investigate the various functions of these visualisations in this chapter; specifically, we do not ask in which sense they are explanatory, if they make use of a metaphor, or how they express and show concepts and relations between them. The material presented here may constitute a corpus of objects for further research, but this exceeds the bounds of the present publication.

The use case starts with a model of the album itself. For every ‘model’, there will be some ‘text’ on the left and a ‘visualisation’ on the right. Running page titles indicate the domain of research (left page) and give a description or name for the diagram (right page). These names are either already established, suggest themselves or are our own proposals. The textual side may contain original quotations, for which we provide translations if the original language is not English. To distinguish quotes from translations, comments and explanations, we use two different fonts. On the right page (bottom right) we credit the creators of the figure: family name for those not drawn by us, initials for contributions from Nils Geissler (NG), Julia Sorouri (JS), Anna Wibbeke (AW) and Patrick Sahle (PS).

5.2 Text Models: An Album

Domain: specifics

Original quote Footnotes Bibliographic information |

Our own translation |

Comments on text or figure |

Name of the figure

Figure |

Origin |

An Introduction: Text as a Word

Text is a common language word. People use it to speak about and point to things. As any other word, it has different meanings in different situations. People use it differently. “The text of this song” means something other than “bring me that text from the library”. We use words without the need to strictly define them or model their domain of application because we use them in context. When it comes to scholarship and science, disciplines demand explicitness and therefore engage extensively in modelling what is denoted by words. It is however not uncommon for researchers and scholars to start this process by conceding that the words they model enjoy or suffer from a pre-theoretical use …

Text: Thought, Spoken and Written

PS, JS

Linguistics: First Impression

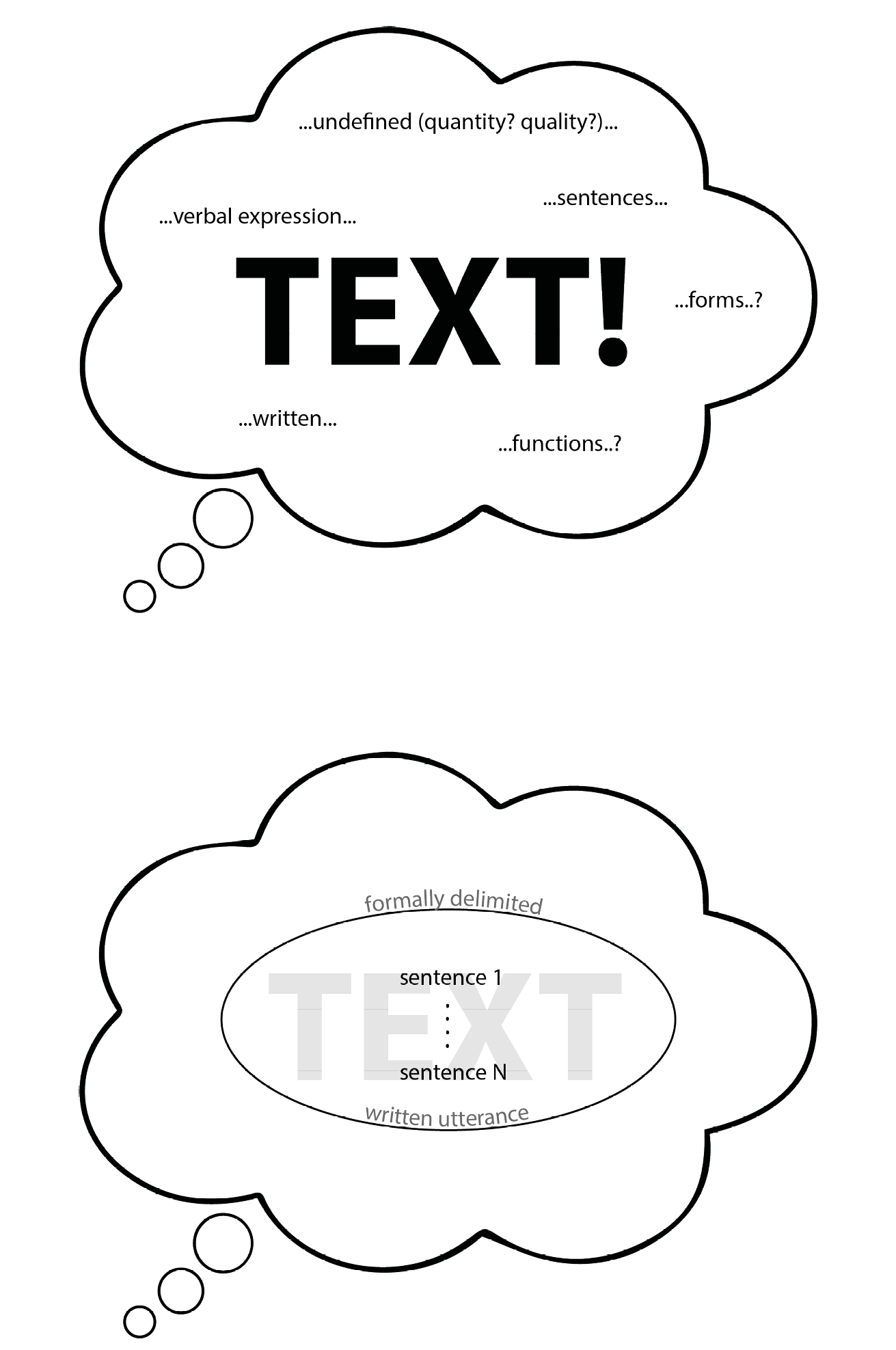

“text (n.) A pre-theoretical term …”

Crystal, David. A [first] Dictionary of Linguistics & Phonetics, Oxford: Blackwell, 1980, 350 (21985, 31991, 31994, 41996, 52003, 62008).

|

“Text ist eine vortheoretisch intuitive, weder quantitative noch qualitativ definierte Kategorie sprachlicher Äußerungen von mehr als einem Satz, die sich vorwiegend auf schriftliche Erzeugnisse unterschiedlichster Form und Funktion bezieht.” Horacek, Helmut. ‘Text, Diskurs Und Dialog’. In Computerlinguistik Und Sprachtheorie. Eine Einführung, edited by Carstensen et al., 2nd ed., 335–347. München: Elsevier, 2004, 335 (12001, 32010). Horacek here refers explicitly to Bußmann, Hadumod, ed. Lexikon Der Sprachwissenschaft. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, 1990, 776 [other editions: 11983 (p. 535), 32002, 42008 (p. 719)] – see below on how the quote does not match exactly. |

Text is a pre-theoretic intuitive, neither quantitatively nor qualitatively defined category of verbal expression of more than one sentence that mainly refers to written products of most diverse form and function. [own translation] |

|

“Text[: ...] Vortheoretische Bezeichnung formal begrenzter, schriftlicher Äußerungen, die mehr als einen Satz umfassen.” Bußmann, Hadumod, ed. Lexikon der Sprachwissenschaft. Stuttgart: Kröner 21990, 776. |

Text: Pre-theoretical term for formally delimited written utterances of more than one sentence. [own translation] |

The claim that ‘text’ is a pre-theoretical term can get lost in translation (here: from German to English). It seems as if, when talking about text, a theory necessarily evolves...

“text[: ...] Theoretical term of formally limited, mainly written expressions that include more than one sentence.”

Bußmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Translated by Gregory P. Trauth and Kerstin Kazzazi. London; New York: Routledge, 1996, 1187 (21998, 32006).

Thinking of Text

PS, NG, JS

Linguistics: Short Definition

|

“Ein Text ist eine komplex strukturierte, thematisch wie konzeptionell zusammenhängende sprachliche Einheit, mit der ein Sprecher eine sprachliche Handlung mit erkennbarem kommunikativem Sinn vollzieht.” Linke, Angelika, Markus Nussbaumer, and Paul R. Portmann. Studienbuch Linguistik. 4th ed. Reihe Germanistische Linguistik. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2001, 245 (11991, 21994, 31996, 52004, repr2007). |

A text is a complexly structured, thematically as well as conceptually coherent linguistic unit, with which a speaker executes a verbal action with recognisable communicative sense. [own translation] |

Text as Megaphone

NG, PS, JS

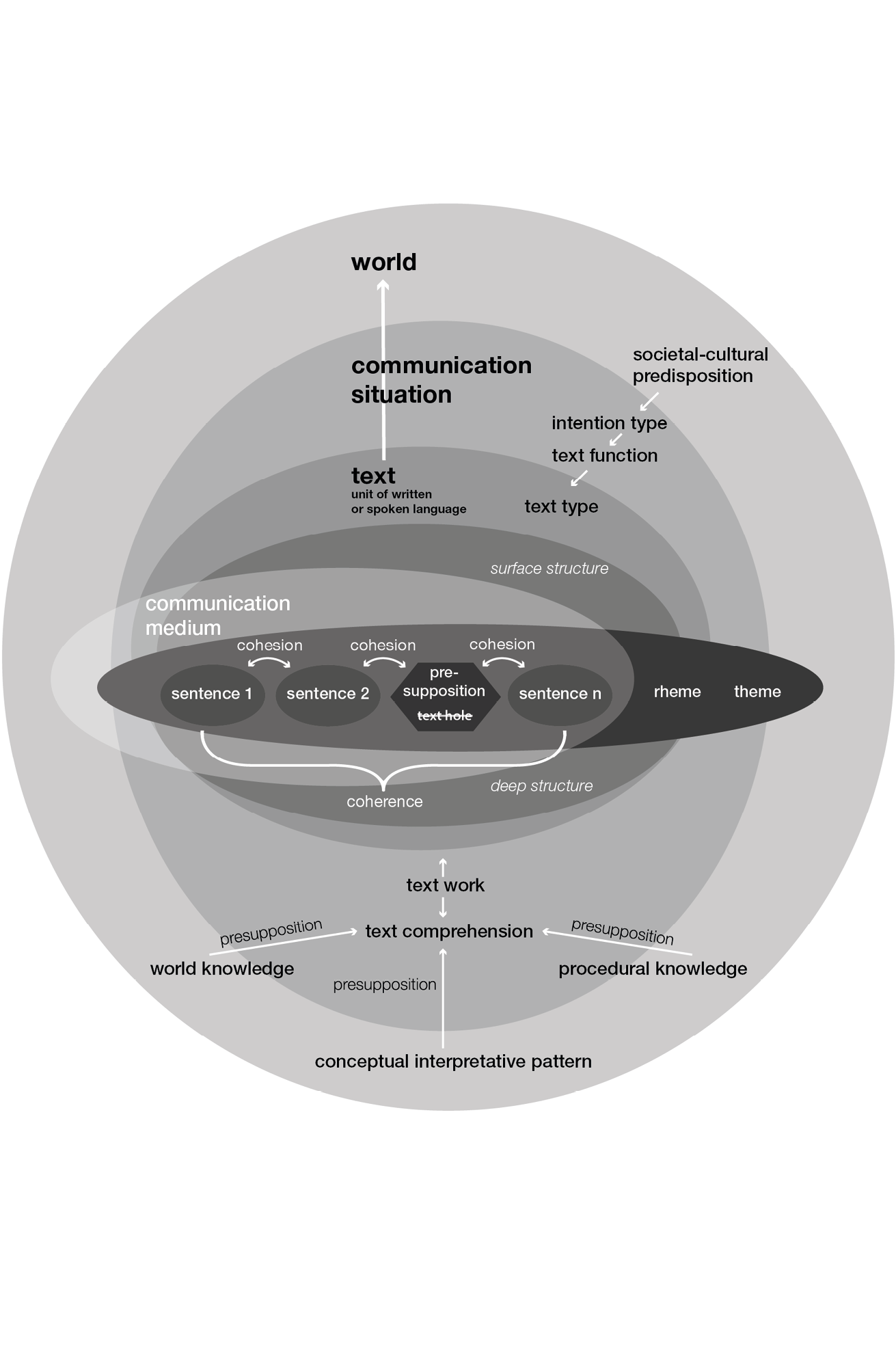

Linguistics: Extensive Definition

Texts, i.e. language units we recognise as a unity although eventually comprising more than one sentence (212) are a product of a union of multiple sentences to a whole (215). The relations between individual sentences can be associated with linguistic elements in many cases. Those elements are syntactically and semantically clearly interrelated—this is called cohesion (215). Text is seen as the topmost form of organisation in speech—speech understood as the particular linguistic products in concrete communication situations (223). A text always just directly gives access to a surface structure, where many—but not all—information units of a text are realised verbally and—also only partly—connected by means of cohesion (224f). The conceptual base of a text—the deep structure—is multi-dimensional, its distinct information units are complexly interlinked (225). “Text holes” on the text surface can be cleared by the text recipient supplementing missing text blocks. The recipients construct relations between text elements thus carrying out text work using extralingual knowledge (226). Where recipients lack the necessary knowledge for the completion of presuppositions (233f), they must infer sensible ‘intermediate pieces of text’ (234). Relevant fields of knowledge are world knowledge and procedural knowledge (227). With the term ‘conceptual interpretative patterns’ we refer to a stock of knowledge that is part of and a prerequisite for our ‘world knowledge’ (227). The Theme is the core content that must not get lost even when radically shortening a text (237). Theme is what something is said about, whereas rheme is what is said (238). A text is a complexly structured, thematically and conceptually coherent linguistic unit, with which a speaker performs a speech act with recognisable communicative sense (245). Text function relates to ‘intention types’, which have a societal-cultural predisposition (246). The communication medium is an extra-textual criterion, which ‘carries’ the text (250).

[own translation of]

Linke, Angelika, Markus Nussbaumer, and Paul R. Portmann. Studienbuch Linguistik. 4th ed. Reihe Germanistische Linguistik. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2001, 212-250 (11991, 21994, 31996, 52004, repr2007).

Textual Atmospheres

PS, NG, JS

Linguistics: Communication

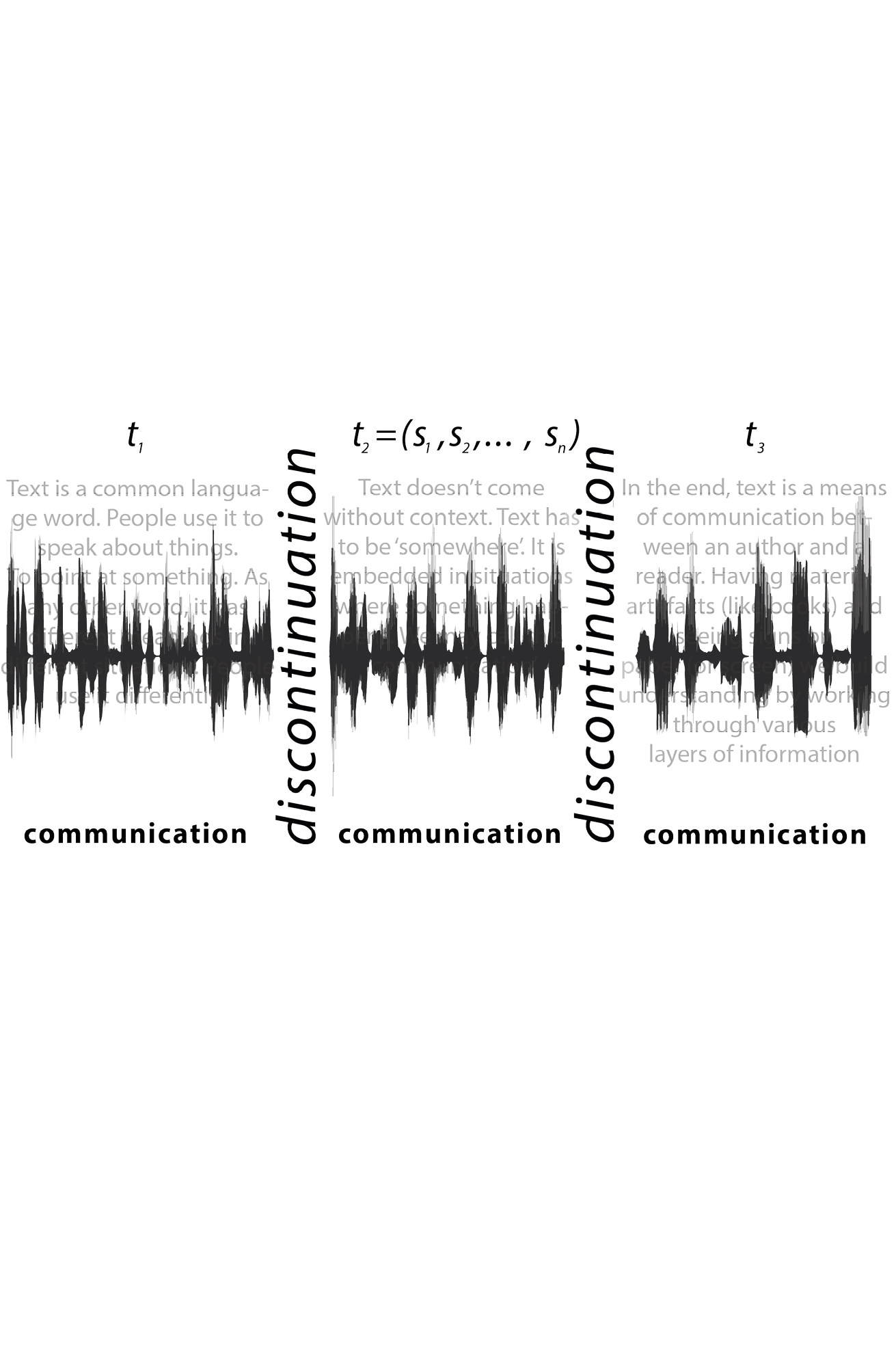

Text does not come without context. Text has to be ‘somewhere’. It is embedded in situations where something happens. We may call this ‘communication’.

“[A] text [is] ‘an ordered sequence of language signs between two noticeable discontinuations {Unterbrechungen} of communication’.”

Beaugrande, Robert-Alain de. ‘Text Linguistics’. In Discursive Pragmatics, edited by Jan Zienkowski, Jan-Ola Östman, and Jef Verschueren, 286–296. Handbook of Pragmatics Highlights 8. Benjamins, 2011, 288. [Original square brackets were altered into curly brackets for the sake of consistency.]

Text as Discontinued Sequences of Communication

PS, NG, JS

Linguistics: Formalisation

“[There are d]efinitions like ‘a text is a coherent sequence of utterances’ (Isenberg 1970, Steinitz 1969, Weinrich 1971), a text is a coherent sequence of language signs and/or sign complexes which are not a priori embedded in another (comprehensive) language unit (Brinker 1979, 7) […]”

Viehweger, Dieter. ‘Coherence – Interaction of Modules’. In Connexity and Coherence: Analysis of Text and Discourse, edited by Wolfgang Heydrich, Fritz Neubauer, János S. Petöfi, and Emil Sözer, 256–274. Research in Text Theory 12. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1989, 256.

The quote refers to Isenberg, Horst. Der Begriff ‘Text’ in der Sprachtheorie. Berlin: Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR, 1970, to Steinitz, Renate. Adverbial-Syntax. 1st ed. Studia Grammatica 10. Berlin: Akademie-Verl., 1969, to Weinrich, Harald. Tempus. Besprochene und erzählte Welt. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln, Mainz: Kohlhammer, 1971 and to Brinker, Klaus ‘Zur Gegenstandsbestimmung und Aufgabenstellung der Textlinguistik’. In Text vs. Sentence. Basic Questions of Text Linguistics, edited by János S. Petöfi, 2:3–12. Hamburg: Buske, 1979.

“Any sequence of sentences temporally or spacially [sic] arranged in a way to suggest a whole will be considered to be a text”

Koch, Walter A. ‘Preliminary sketch of a semiotic type of discourse analysis’. In Linguistics vol. 3 issue 12 (1965): 5-30 (here p. 16).

|

“Wir verstehen unter einem ‘Text’ eine kohärente Folge von Sätzen[...].” Isenberg, Horst. Der Begriff ‘Text’ in der Sprachtheorie. Berlin: Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR, 1970, 1. |

We understand “text” as a coherent sequence of sentences [...]. [own translation] |

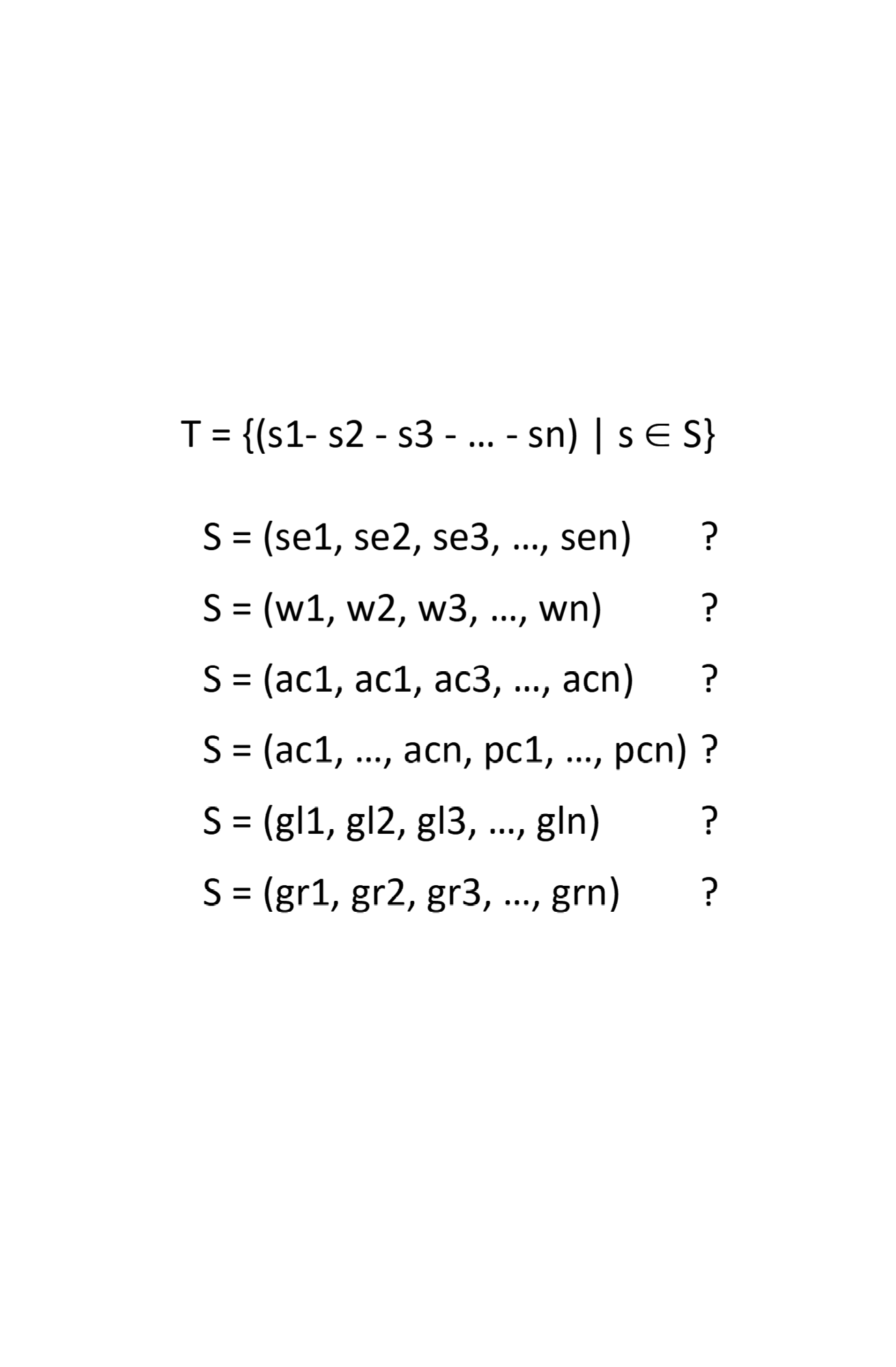

“I use the term ‘text’ […] as a synonym for ‘sequence of linguistic signs’. This should be sufficiently general and vague to be quite uncontroversial.”

Reicher, Maria. ‘Objective Interpretation and the Metaphysics of Meaning’. In Language and World. Part Two: Signs, Minds and Actions, edited by Volker Munz, Klaus Puhl, and Joseph Wang, 181–190. Heusenstamm: Ontos Verlag, 2010, 185.

Sometimes, it is said that text is a sequence of language [or linguistic] signs. This sounds like a clear definition and a complete text model. But what are the language signs? And in which way are the sets of language signs finite and well defined? For some the language signs might be sentences (se), for some they might be words (w). Some may say that language is represented in texts by characters of an alphabet (ac). Some would like to include punctuation marks in the set of language signs (pc). Some would argue that language signs in fact are realisations of characters, allographs or glyphs (gl) – making s and ſ two different language signs; as well as s and s (as being two instances and distinct on the graph level - gr).

Text Sequence Formula

PS

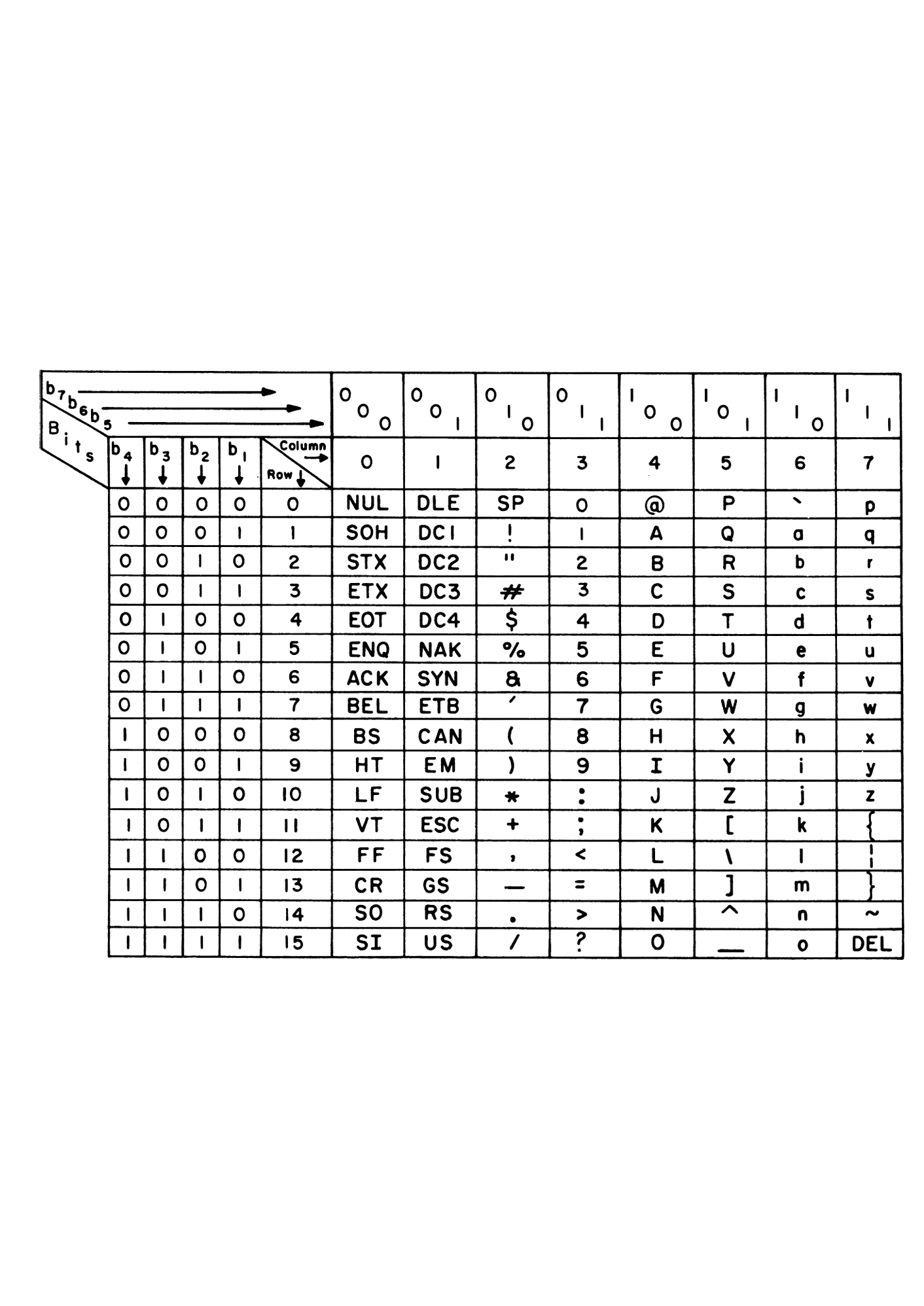

Text Technologies: Standardisation

Probably by far the most influential text technology in our digital media environment has been (and with its successor Unicode still is) the “American Standard Code for Information Interchange” (ASCII) which paved the way for a common global representation of texts.

Every technical solution realises a (often implicit) model of its domain. Based upon the technical possibilities and limitations of encoding, the ASCII standard was first published 1963 and as matured standard in 1968. It comprises these features:

- Given 7 bits of zero and one, 128 code positions are possible. Therefore 128 codes make up the set of textual signs.

- Text is a sequence of distinct signs (characters); one position (one index), one sign. Signs themselves do not have modes. The mode “case” is realized by doubling the alphabet.

- There are normal, visible, printable characters and other, non-printable characters

- printable characters comprise the Latin alphabet, numbers, punctuation marks and other special characters

- non printable characters relate to the structure of the text (as a stream or as displayed in two dimensions) or the transmission of texts between devices

- Signs and Codes are inherited from the tradition of previous text technologies (mostly typewriter and teletype machines) or created due to the intended use of the standard in text encoding and transmission

- Codes are positioned in groups and in bit-shifting relation to each other (upper/lower case; numbers and special characters), following the typewriter tradition or in favour of easy sorting and computation.

The ASCII code is often visualised as a table. There is no compelling reason for this but allows for a strong compactness. Using columns for the 5th to the 7th bit as well as grouping the 16 codes of bit one to four as rows reveals some inner order of the code. Non-printable and control characters are mostly in group one and two. Alphabet characters are in four and five (upper case) and six and seven respectively. With that, there is also an inner functional logic in the positions: changing the sixth bit shifts the letter case.

The diagram (table) comes from the manual to a type printer of the early 1970s. Despite its origin in this rather ephemeral source, it has become quite ubiquitous as a meme for ASCII and binary encoding of data since its use as an illustration to the English Wikipedia article “ASCII” where it is stated as: “copied from the material delivered with TermiNet 300 impact type printer with Keyboard, February 1972, General Electric Data Communication Product Dept., Waynesboro, Virginia.” (Wikimedia)

ASCII Code Chart

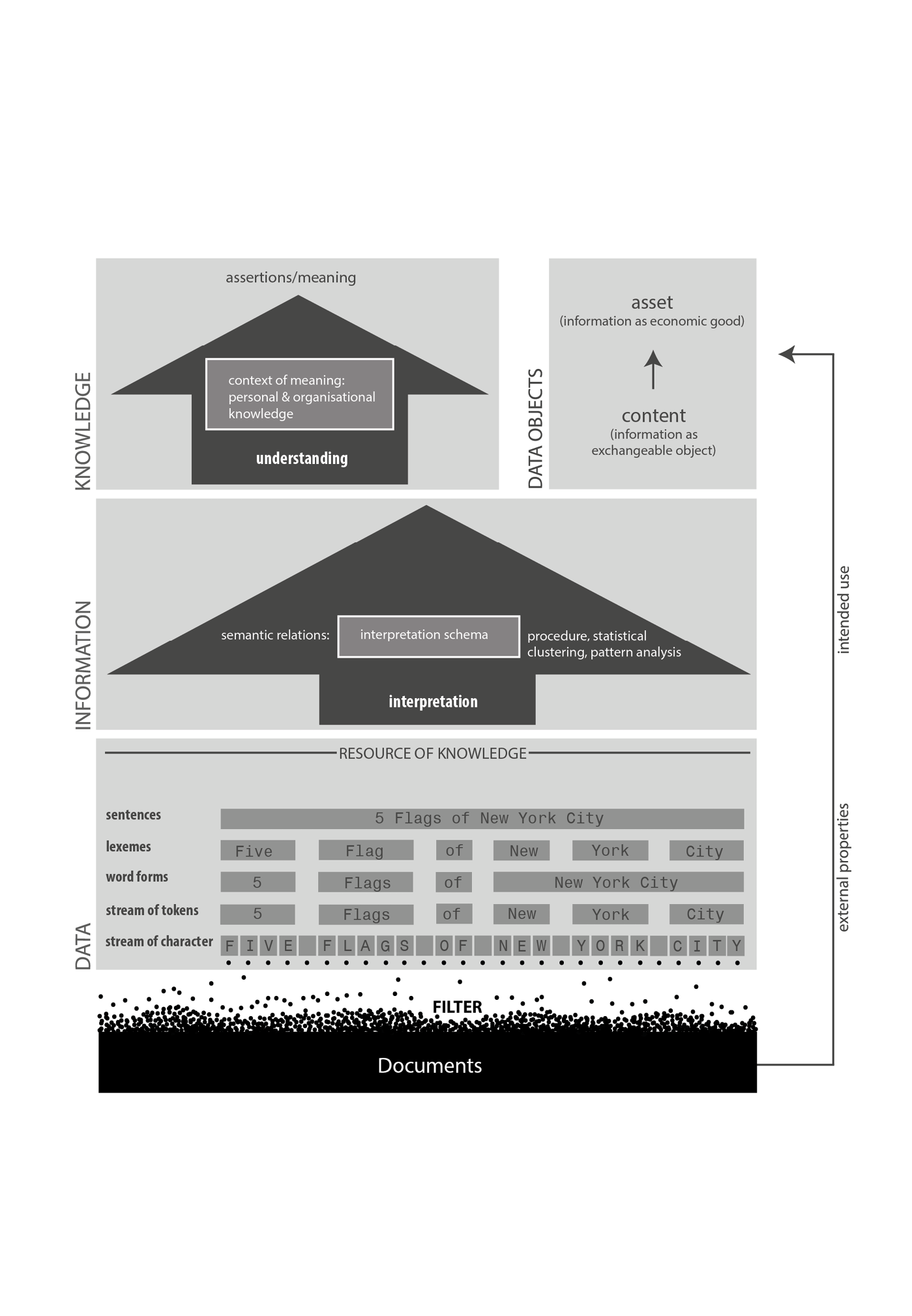

Computational Linguistics: Text Mining and Knowledge Representation

|

“Text repräsentiert Wissen und stellt insofern eine wesentliche Grundlage der Wissensverarbeitung dar. Ein Text besteht aus Wortformen, die ihrerseits aus den Buchstaben eines Alphabets bestehen. Die Wortformen und Sätze eines Textes stellen informationstheoretisch gesehen zunächst einfach nur Daten dar. Werden diese Daten interpretiert (mit Bezug auf ein vorher festgelegtes Interpretationsschema), dann werden die Daten zu Informationen. Werden Informationen mit anderen Informationen vernetzt und zur Lösung von Problemen eingesetzt, dann werden sie als Wissen bezeichnet. Die intendierte Nutzung eines Textes lässt sich oft anhand externer Merkmale dieses Textes erkennen.” (7f) “Um Wissen [...] extrahieren zu können, müssen zunächst semantische Relationen zwischen den Zeichenketten erkannt werden. [...] Wesentliche Verfahren hierfür sind sprach-statistische Verfahren, Clustering-Verfahren (Cluster-Analyse) und musterbasierte Verfahren.” (9f) “Zeichen [...] lassen sich [...] zu Zeichenketten kombinieren. Eine nach vorher festgelegten Regeln zusammengestellte, endliche Folge von Zeichen und Zuständen, die eine Information vermittelt, bezeichnet man als Nachricht. Eine Nachricht zusammen mit ihrer Bedeutung für den Empfänger ist eine Information.” (10) “Die [...] ausgetauschten Nachrichten werden als Daten bezeichnet. Daten sind also nicht interpretierte Zeichen bzw. Zeichenfolgen, die erst durch die Herstellung eines Interpretationsbezugs zu Informationen werden.” (10) “Als Nachricht, die für den Empfänger nach einem festgelegten Informationschlüssel eine Bedeutung hat, besteht eine Information aus Daten, die in einem Bedeutungskontext stehen. Damit allerdings diese Information für den Empfänger auch wertvoll ist, [d.h. zum erfolgreichen Verstehen, muss eine Vernetzung stattfinden, d]iese [...] wird durch das Wissen einer Person oder Organisation geleistet.” (11) “Wird dagegen der Inhalt von Informationen nicht ausgewertet, sondern werden die Informationen nur als sinnhaltige Datenobjekte behandelt, spricht man von Content. [...] Als Wirtschaftsgut wird Content meist als Asset bezeichnet.” (11) “[Text Mining dient dazu], um aus den verfügbaren Datenquellen (Dokumente [...] usw.) das implizit bzw. explizit repräsentierte Wissen [...] abzuleiten [...].” (17) Heyer, Gerhard, Uwe Quasthoff, and Thomas Wittig. Text Mining: Wissensrohstoff Text. Herdecke: W3L, 2006; revised reprint, Herdecke: W3L, 2008. |

“Text represents knowledge and thus is an essential basis of knowledge processing. A text consists of word forms, which itself consist of characters of an alphabet. The word forms and sentences of a text are (by means of information science) just data. When this data is interpreted (using a predetermined interpretation schema), it becomes information. When information is linked to other information and used to solve problems, it is called knowledge. The intended use of a text can often be recognised by external properties. (7f) To be able to extract knowledge, semantic relations between strings have to be identified. Essential procedures are statistical analysis, clustering analysis, and pattern analysis. (9f) Characters can be combined with strings. A finite sequence [stream] of characters and states, composed using predetermined rules, that convey an information, is called a message. A message together with its meaning for a recipient is information. (10) Exchanged messages are called data. Thus data is non-interpreted characters or strings that only become information through an interpretational reference. As a message that has a meaning for a recipient by an established information key, information consists of data within a context of meaning. For information to be of worth for the recipient and thus making sense, creating understanding, there has to be interlinkage, which is provided by personal or organisational knowledge. (11) If [the content of] information is not used but treated as meaningful data objects, it is called content. Content seen as economic good is usually called asset. (11) Text Mining is used to derive implicitly or explicitly represented knowledge from data sources (documents etc.). (17) [own translation] Note: Filter relation between documents and the stream of characters is our addition, as well as ‘lexemes’ or ‘stream of token’. |

Text Mining as Knowledge Processing

PS, JS

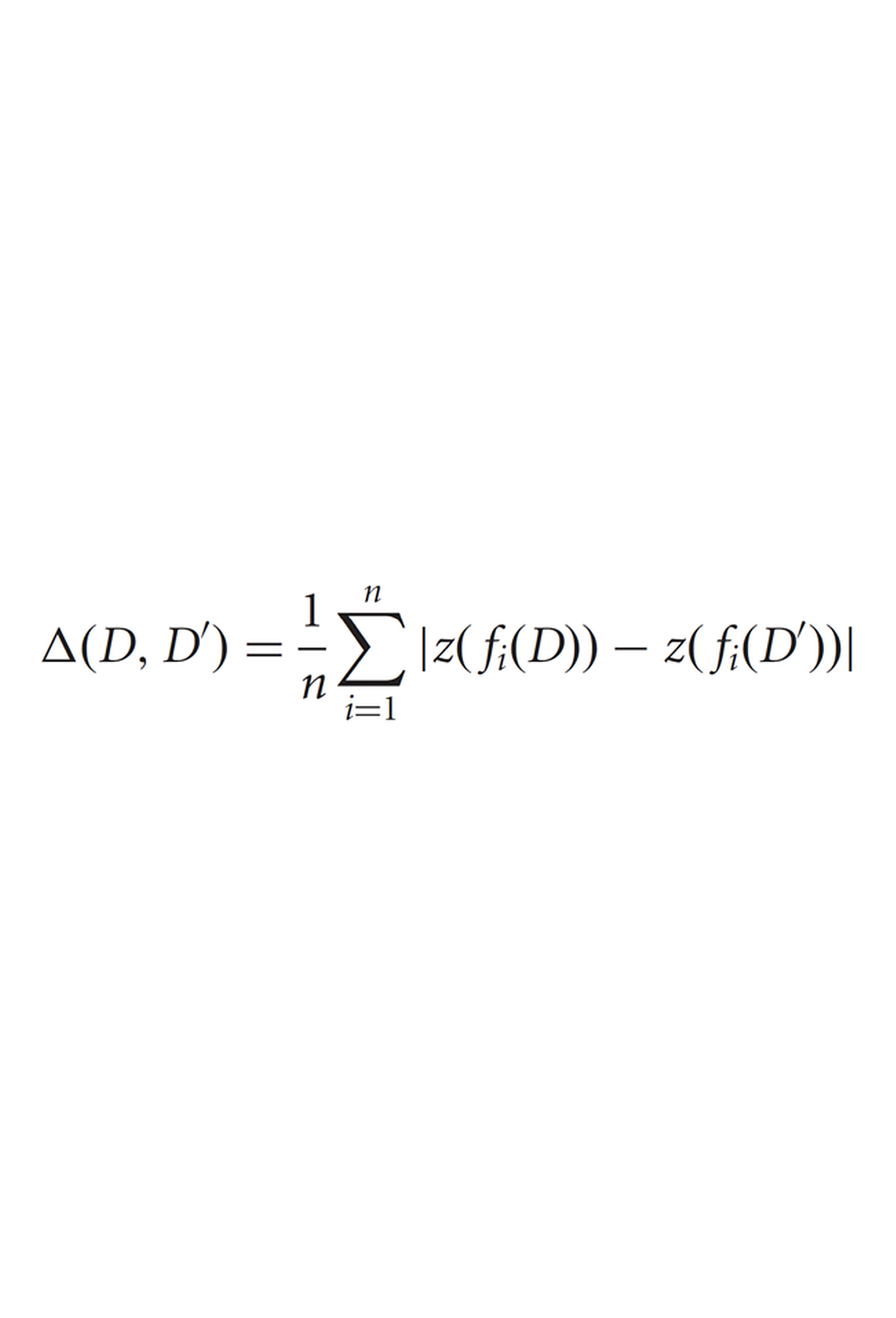

Computational Literary Studies: Burrows’s Delta

What is text? When are texts similar? What is the style of a text? Who is the author of a text?

Texts can be described by their similarity to each other. Burrows Delta is a measure to quantify the stylistic proximity of texts. To do so, the relative frequency of the most frequent words are - after some normalisation steps - compared across the texts in a corpus, resulting in a score which is Burrows Delta. This operationalization (purposefully) relies on a certain model of text as a set of word occurrences. Word order, phrase, sentence and other textual properties have been neglected here. It is a model of ‘style’, an operational model that works on the basis of a reductive model of text. The text model from digital literary studies that is applied here is the “bag of words” approach. Style models in traditional literary studies are based on different models of text.

Literature: Burrows, John. ‘“Delta”: A Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely Authorship’. Literary and Linguistic Computing 17, no. 3 (2002): 267–287.

Burrows, John. ‘Questions of Authorship: Attribution and Beyond: A Lecture Delivered on the Occasion of the Roberto Busa Award ACH-ALLC 2001, New York’. Computers and the Humanities 37, no. 1 (2001 2003): 5–32.

Figure: Argamon, Shlomo. ‘Interpreting Burrows’s Delta: Geometric and Probabilistic Foundations’. Literary and Linguistic Computing 23, no. 2 (2008): 131–147 (formula on page 132).

Context: For a discussion of the concepts of ‘style’ in traditional and digital literary studies, see: Herrmann, J. Berenike, Christof Schöch, and Karina van Dalen-Oskam. ‘Revisiting Style, a Key Concept in Literary Studies’. Journal of Literary Theory 9 (2015).

Burrows’s Delta Formula

Argamon

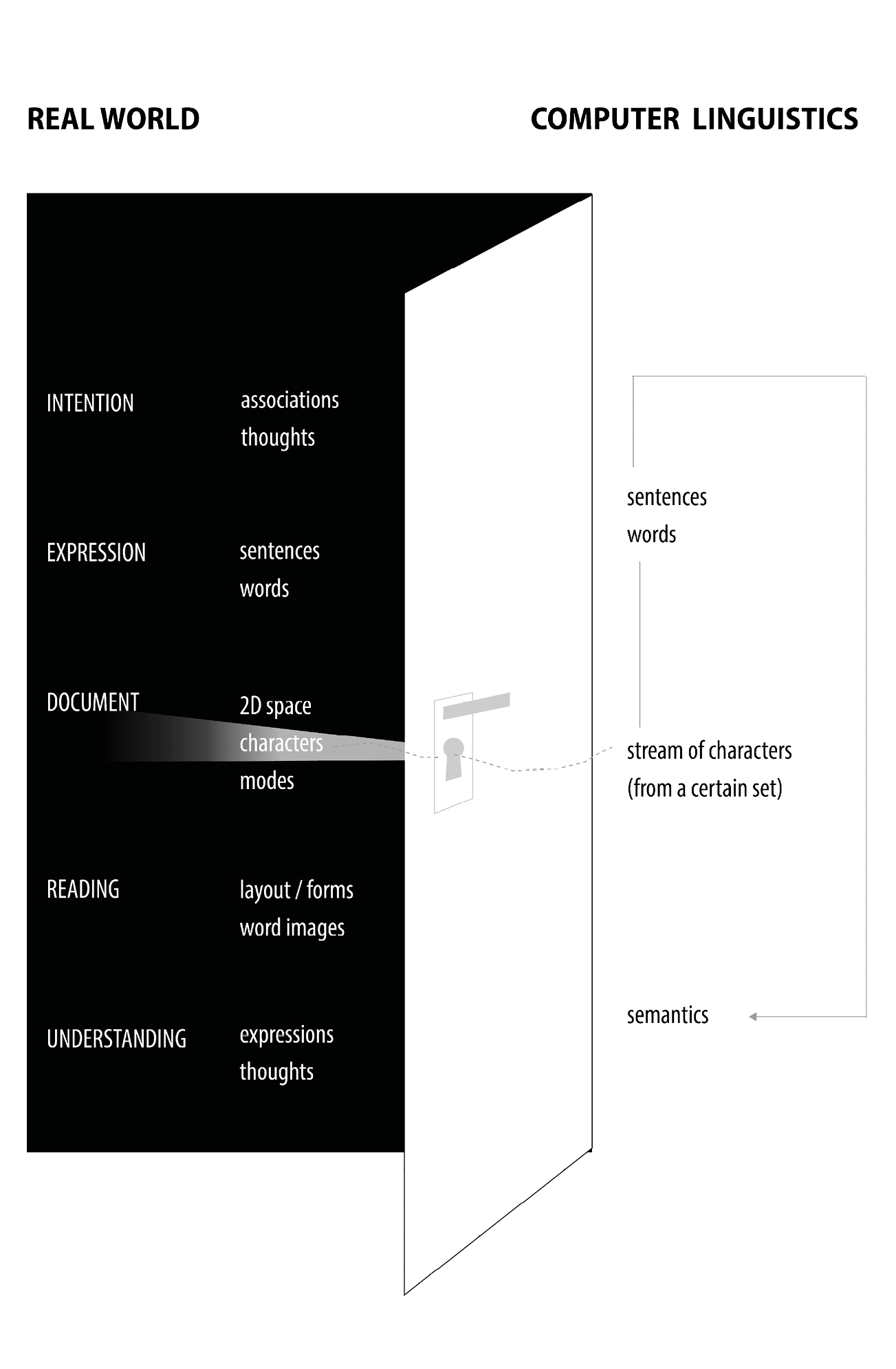

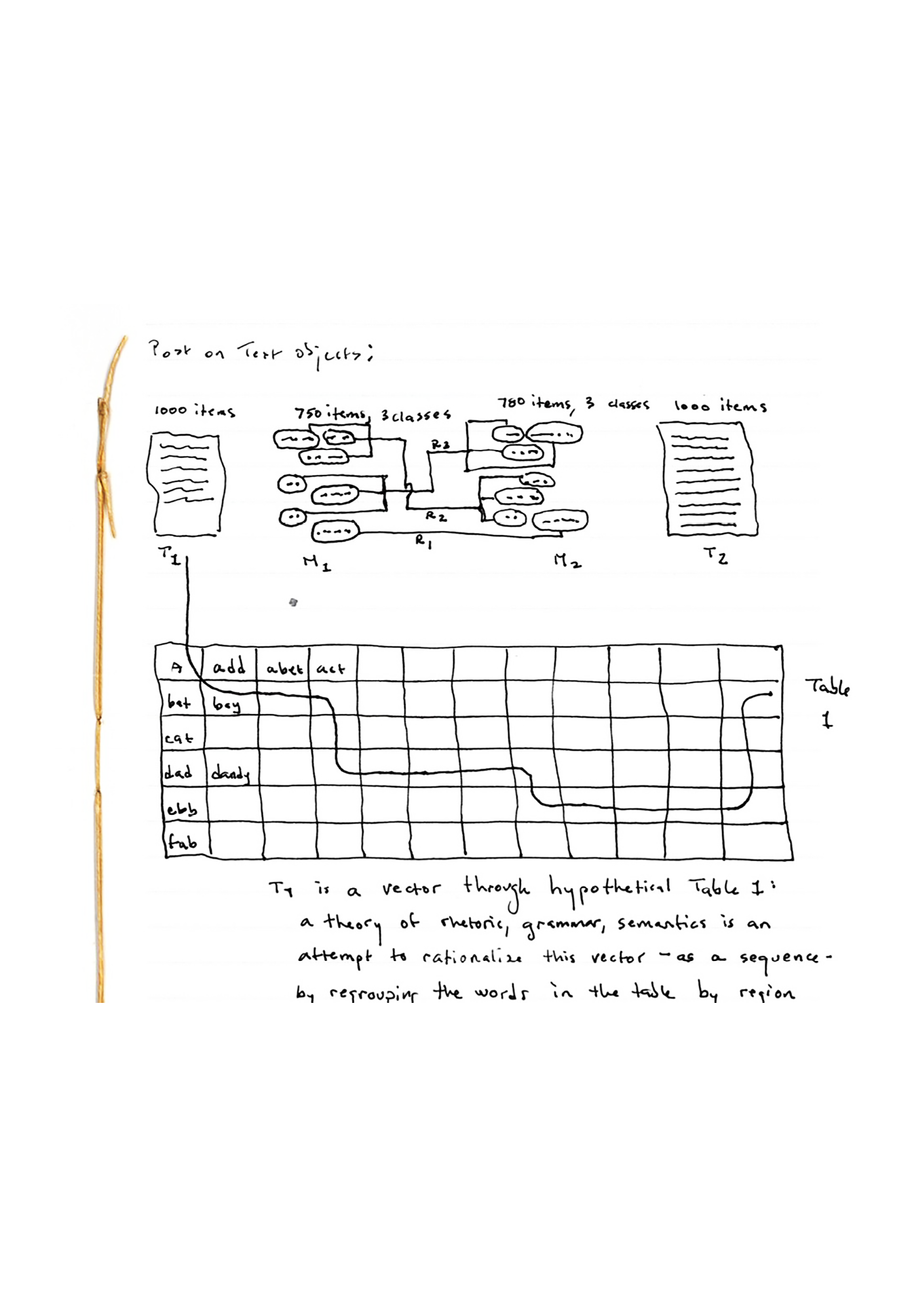

Computer Linguistics: An Analytic Stance Towards a Real World Media System

In the room of textuality, authorial intention is expressed through documents, which are understood through reading. Computer linguistics are also interested in studying texts which are found in documents. These are seen as carriers of sequences of characters. In a reductionist approach, other textual features such as layout (indicating textual structures) or modes of written language (like bold, italics etc.) are considered non-essential. Starting from the filtered stream of characters, the authorial expression as words and sentences is detected and from this, the meaning is derived.

The textual model of computer linguistics in its easy computability is very powerful and has led to astonishing results in manifold applications of handling, aggregation, transmission, translation, analysis and use of texts.

Yet, for people focusing on textuality as a somewhat more complex and layered media system, the computational linguistics approach towards text may seem like looking through a keyhole.

The Keyhole Model

PS, JS

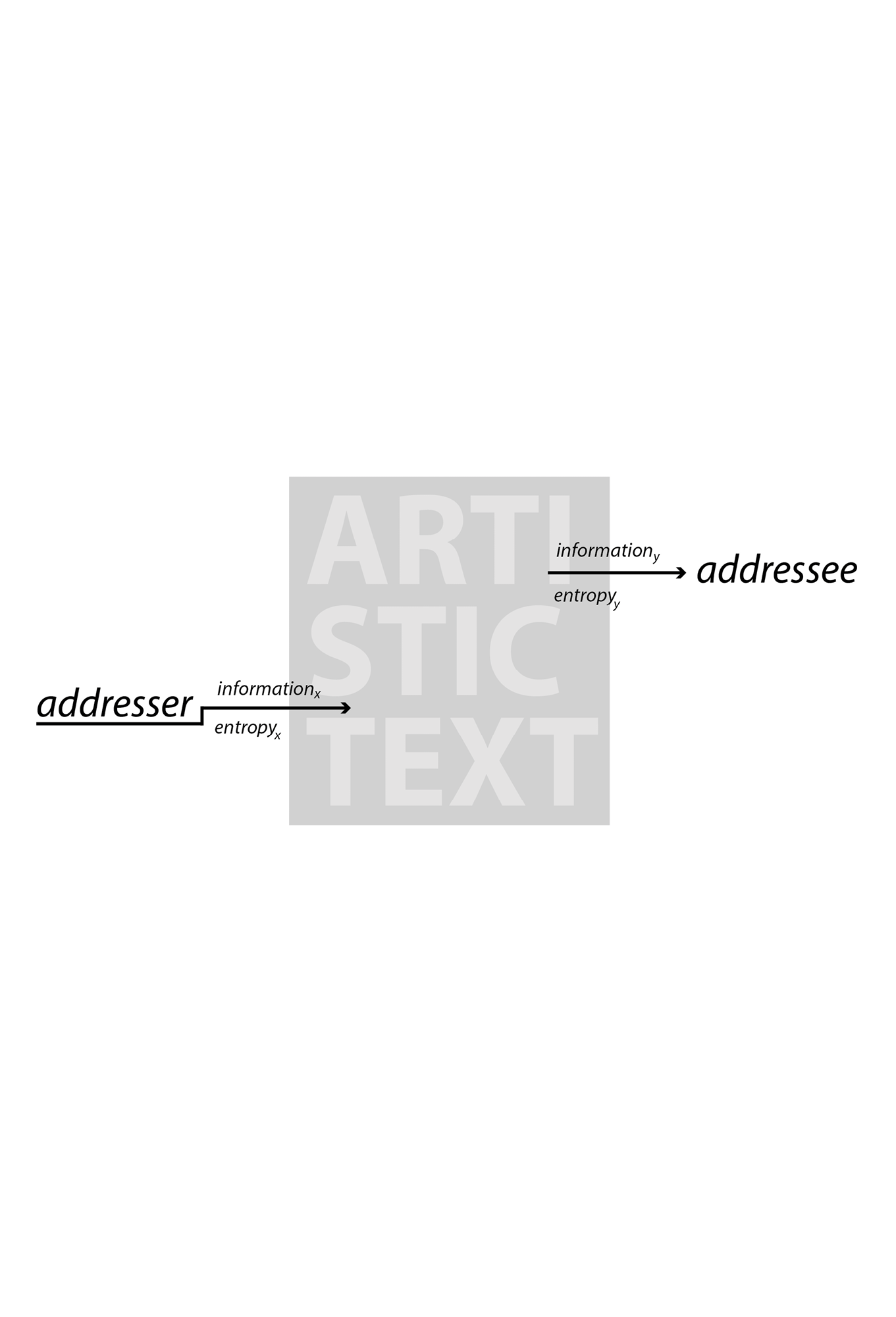

Semiotics: The Artistic Text

“But an artistic text is the end product of the exhaustion of different entropy for addressee and addresser, and consequently carries different information for each.”

Lotman, Jurij. The Structure of the Artistic Text. Translated by Ronald Vroon. University of Michigan, 1977, p. 31.

Information and Entropy of the Artistic Text

PS, NG, JS

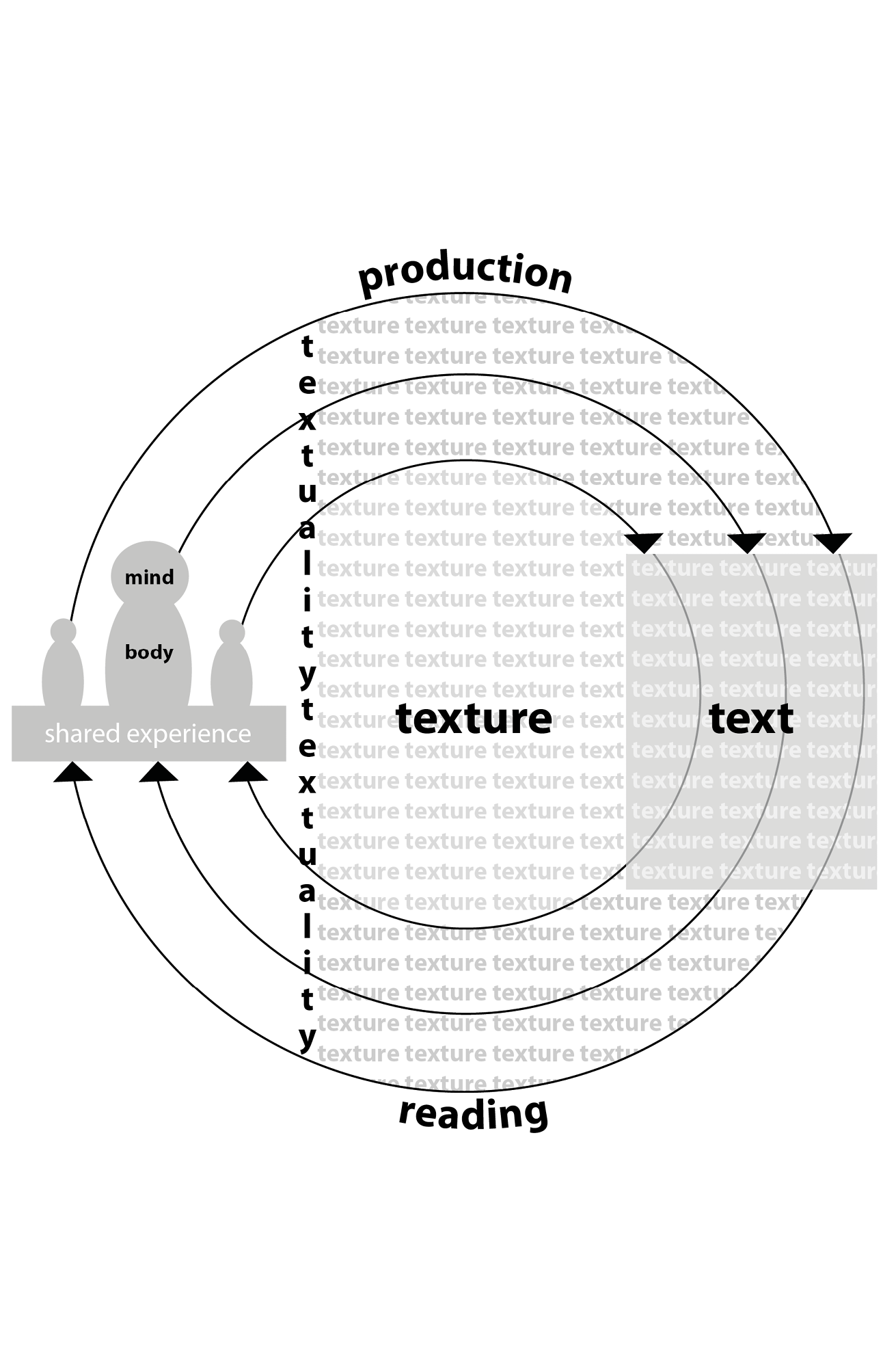

Literary Studies: Text, Textuality and Texture

“The proper business of literary criticism is the description of readings.

Readings consist of the interaction of texts and humans.

Humans are comprised of minds, bodies and shared experiences.

Texts are the objects produced by people drawing on these resources.

Textuality is the outcome of the workings of shared cognitive mechanics,

evident in texts and readings.

Texture is the experienced quality of textuality.”

Stockwell, Peter. ‘Text, Textuality and Texture’. In Texture. A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading, pp. 1–16. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009, p. 1.

Circle of Textuality

NG, PS, JS

Cultural History: On Spoken and Written Text

See also Wenzel, Horst. ‘Poststrukturalismus. Die “fließende” Rede Und Der “gefrorene” Text. Metaphern der Medialität’. In Herausforderung an die Literaturwissenschaft, edited by Gerhard Neumann, 481–503. Stuttgart, Weimar: Metzler, 1997. Or Luhmann, Niklas. ‘Die Form Der Schrift’. In Germanistik in Der Mediengesellschaft, edited by Ludwig Jäger and Bernd Switalla, 405–425. München: Fink, 1994, 422.

Frozen Text

PS, JS

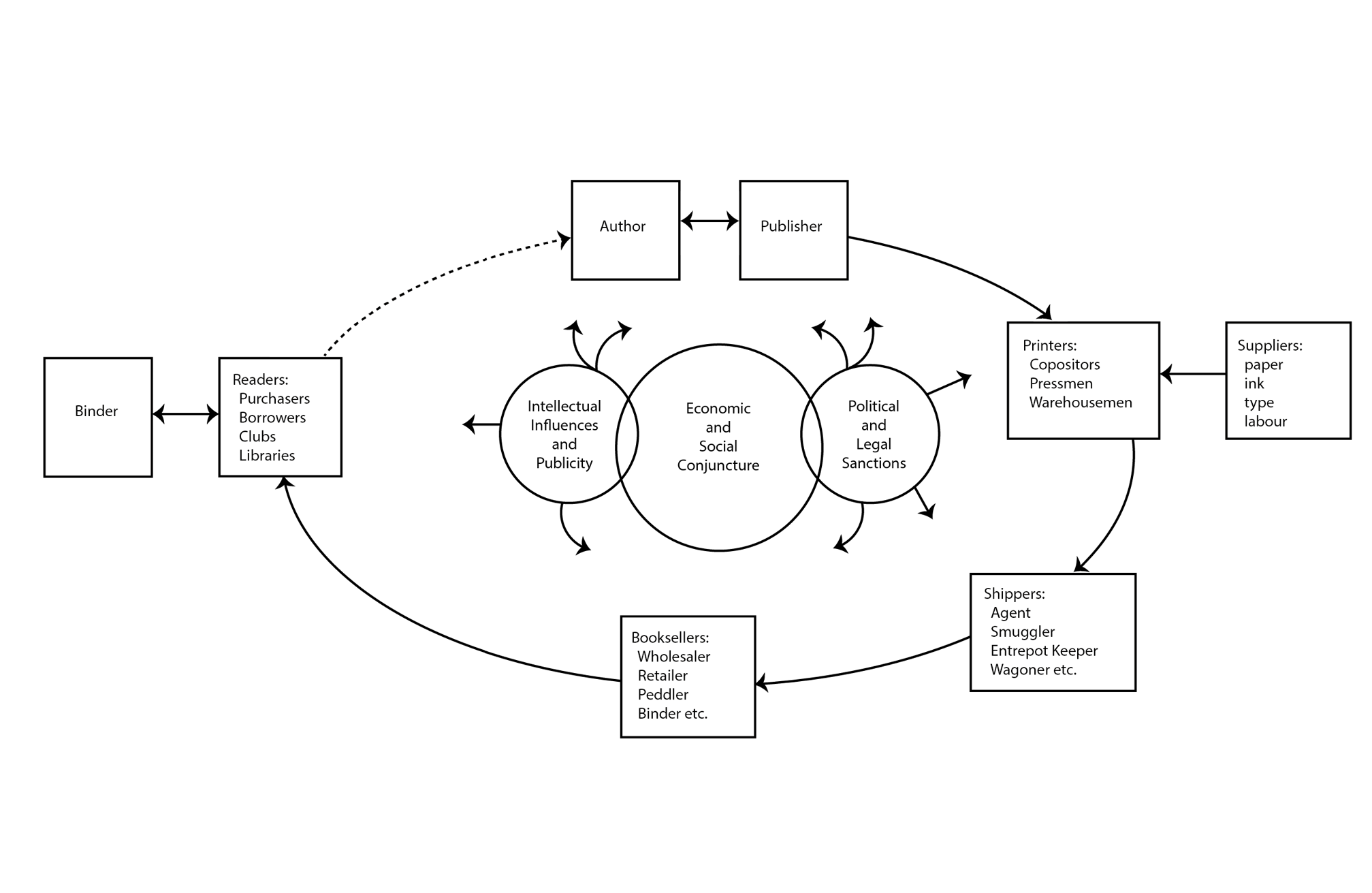

Cultural History: Text Production and Communication

Text as document as book is always part of a complex communication circuit. In order to understand texts it is necessary to understand the conditions, relations and interactions in the creation, distribution and reception of textual media.

The Communication Circuit

“I am not arguing that book history should be written according to a standard formula, but trying to show how its disparate segments can be brought together within a single conceptual scheme.” (75) “[... H]owever [… different book historians] define their subject, they will not draw out its full significance unless they relate it to all the elements that worked together as a circuit for transmitting texts.” (75)

“At what point did writers [read authors] free themselves from the patronage of wealthy noblemen and the state in order to live by their pens? What was the nature of literary career, and how was it pursued? How did writers deal with publishers, printers, booksellers, reviewers, and one another? Until those questions are answered, we will not have a full understanding of the transmission of texts.” (75)

“How did publishers draw up contracts with authors, build alliances with booksellers, negotiate with political authorities, and handle finances, supplies, shipments, and publicity? The answers to those questions would carry the history of books deep into the territory of social, economic, and political history, to their mutual benefit.” (75)

“The printing shop is far better known than the other stages in the production and diffusion of books, because it has been a favorite subject of study in the field of analytical bibliography, whose purpose […] is ‘to elucidate the transmission of texts by explaining the processes of book production.’” (76) “[... B]ibliographers can demonstrate the existence of different editions of a text and of different states of an edition, a necessary skill in diffusion studies. Their techniques also make it possible to decipher the records of printers and so have opened up a new, archival phase in the history of printing.” (77)

“Little is known about the way books reached bookstores from printing shops. The wagon, the canal barge, the merchant vessel, the post office, and the railroad [, and thus shippers] may have influenced the history of literature more than one would suspect.” (77)

“[... M]ore work needs to be done on the bookseller as a cultural agent, the middleman who mediated between supply and demand at their key point of contact. [...] The book trade, like other businesses during the Renaissance and early modern periods, was largely a confidence game, but we still do not know how it was played. […] Despite a considerable literature on its psychology, phenomenology, textology, and sociology, reading remains mysterious. How do readers make sense of the signs on the printed page? And how has it varied? [...] Reading itself has changed over time. It was often done aloud and in groups, or in secret and with an intensity we may not be able to imagine today.” (78) “[... T]exts shape the response of readers, however active they may be. [...]” (79)

“[...B]ooks themselves do not respect limits, either linguistic or national. They have often been written by authors who belonged to an international republic of letters, composed by printers who did not work in their native tongue, sold by booksellers who operated across national boundaries, and read in one language by readers who spoke another. Books also refuse to be contained within the confines of a single discipline when treated as objects of study. Neither history nor literature nor economics nor sociology nor bibliography can do justice to all aspects of the life of a book. By its very nature, therefore, the history of books must be international in scale and interdisciplinary in method. But it need not lack conceptual coherence, because books belong to circuits of communication that operate in consistent patterns, however complex they may be.” (80f)

Darnton, Robert. ‘What Is the History of Books?’ Daedalus 111, no. 3 (1982): 65–83. Figure taken from p. 68, redrawn by Julia Sorouri.

The Communication Circuit

Darnton

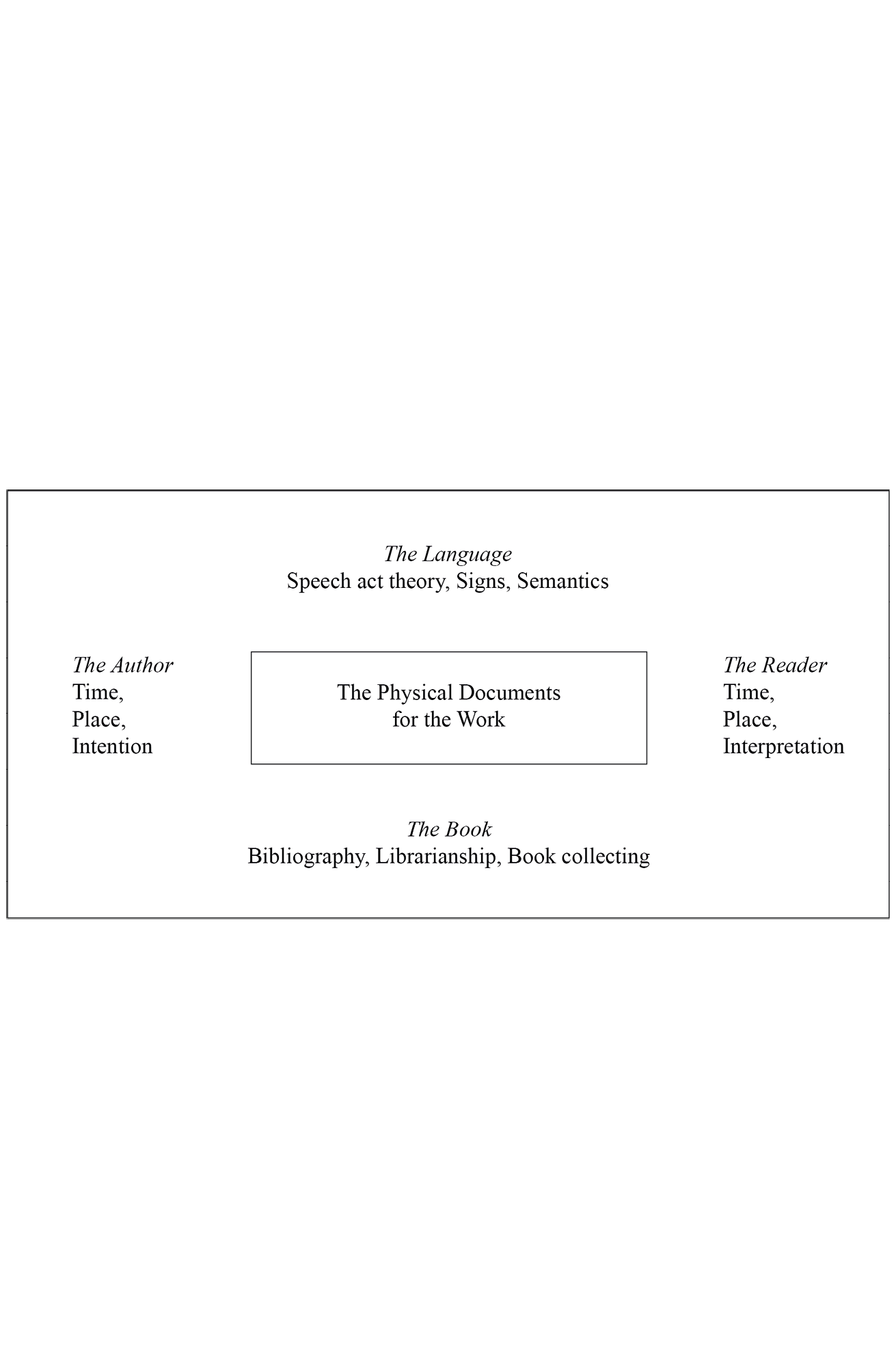

Scholarly Editing / Literary Studies: The Document-Work Ecosystem

“[... L]iterary critics have not had a clear enough vision of the problematic nature of physical texts and their assumptions about textual stability [...]. The ‘structure of reality of written works’ [...] places the writer, the reader, the text, the world, and language in certain relationships and locates the focus of experience of that reality in the reader. This relationship has been mapped by a number of theorists […] but these maps reveal a gaping hole in our thinking, around which swirls a number of vague and sloppily used terms that only appear to cover the situation. The lack of clear focused thinking on this question is revealed graphically when the physical materials of literary works of art are located in a center around which scholarly interests in Works of Art can be visualized. To the West of this physical center is found the scholarship of interest in creative arts, authorial intentions and production strategies, biography, and history as it impinges on and influences authorial activities. To the East of the physical center is the scholarship of interest in reading and understanding, interpretation and appropriation, political and emotive uses of literature. To the North of the physical center is the scholarship of interest in language and speech acts, signs and semantics. All three treat the work of art as mental constructs or meaning units; the physical character of the work is usually considered a vehicular incident , usually transparent. To the South is the scholarship of interest in physical materials: bibliography, book collecting, and librarianship. Only in this last area do we detect the appearance of special attention on the Material Text, but, because traditionally scholars in these fields have made a sharp distinction between the Material and the Text11 and because they have focused their attention on the Material as object, their work has seemed tangential to the interests of the West, North, and East.” (57f)

“11 Note particularly W. W. Greg’s often quoted definition: ‘What the bibliographer is concerned with is pieces of paper or parchment covered with certain written or printed signs. With these signs he is concerned merely as arbitrary marks; their meaning is no business of his’ (‘Bibliography—an Apologia,’ 247).” (58)

Shillingsburg, Peter L. Resisting Texts. Authority and Submission in Constructions of Meaning. 1st ed. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1997, 57f.

The indirect reference is Greg, Walter Wilson. ‘Bibliography—An Apologia’. In Collected Papers, edited by J. C. Maxwell, 239–66. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966, 247.

The Compass of Material Text

Shillingsburg

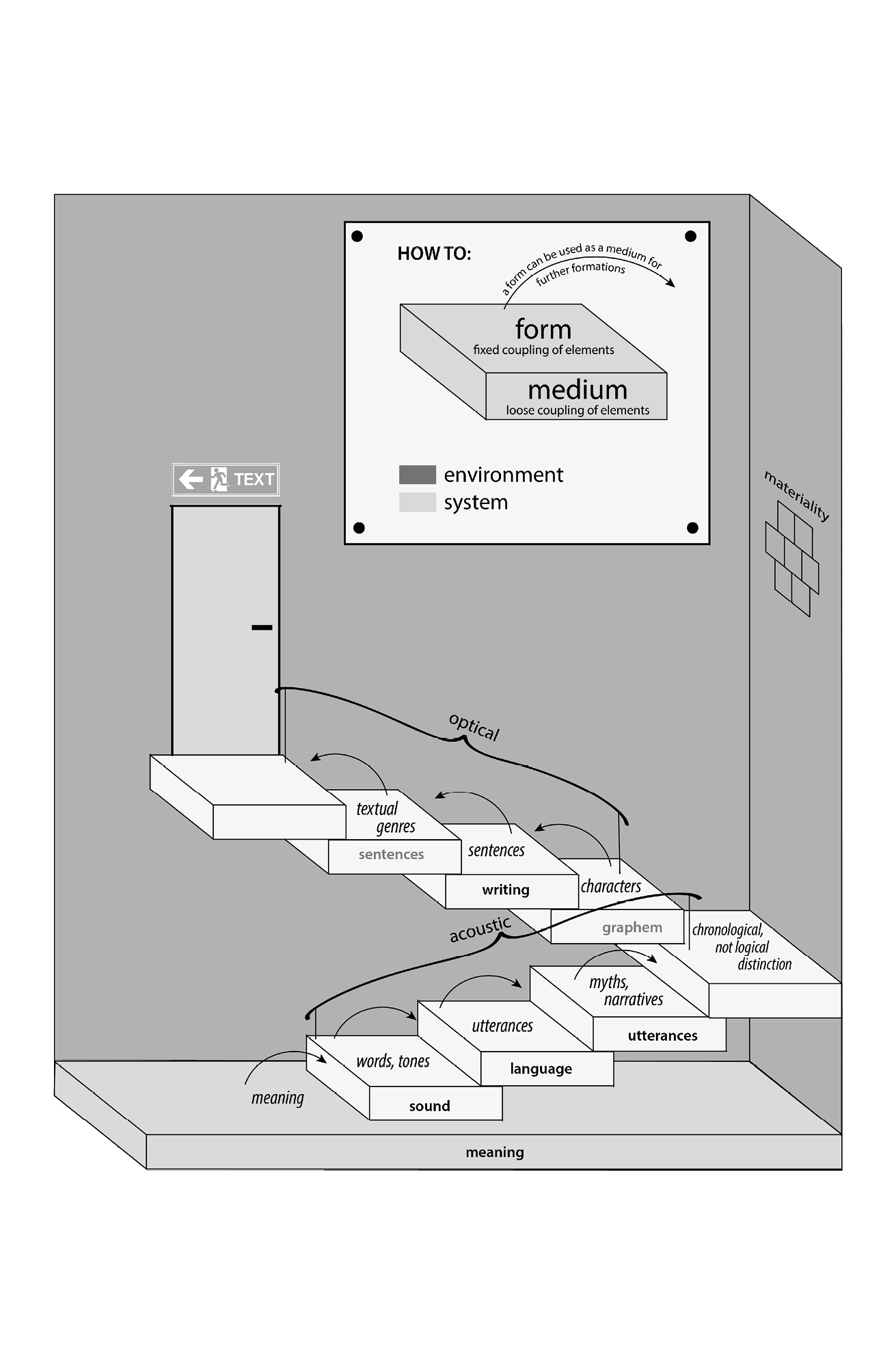

Sociology and Social Systems Theory on Text: Niklas Luhmann

“The distinction between (self-referential, operatively closed) systems and (excluded) environments allows us to reformulate the distinction between text and interpretation. The materiality of texts […] always belongs to the environment and can never become a component of the system’s operational sequences. But the system’s operations determine how texts and other objects in the environment are identified, observed, and described. (99=161) That distinction [between medium and form] is meant to replace the distinction substance/accidence, or object/properties (102=165) [… The term element] always points to units constructed (distinguished) by an observing system – to units for counting money, for example, or to tones in music. (103=167) […] The notion of medium […] applies to cases of ‘loosely coupled’ elements.” (104f=168) [… Rather, the concept indicates an] open-ended multiplicity of possible connections that are still compatible with the unity of an element – such as the number of meaningful sentences that can be built from a single semantically identical word. (104=168) […] media can be recognized only by the contingency of the formations that make them possible. (104=168) Forms are generated in a medium via a tight coupling of its elements. (104=169) […] media impose limits on what one can do with them. Since they consist of elements, media are nonarbitrary. (105=170) […] We can further elucidate the medium/form distinction by means of the distinction between redundancy and variety. The elements that form the medium through their loose coupling – such as letters in a certain kind of writing or words in a text – must be easily recognizable. (105=170) […] It is worth noting that forms, rather than exhausting the medium, regenerate its possibilities. This […] can be easily demonstrated with reference to the role of words in the formation of utterances. Forms fulfil this regenerating function, because their duration is typically shorter than the duration of the medium. Forms, one might say, couple and decouple the medium. (105=170) […] Such elements always also function as forms in another medium. Words and tones, for example, constitute forms in the acoustic medium just as letters function as forms in the optical medium of the visible. […] (106=172) Media are generated from elements that are always already formed. (106=172) […] This situation contains possibilities for an evolutionary arrangement of medium/form relationships in steps […] (106=172) [An] example that illustrates the generality of this step-wise arrangement. In the medium of sound, words are created by constricting the medium into condensable (reiterable) forms that can be employed in the medium of language to create utterances (for the purpose of communication). The potential for forming utterances can again serve as the medium for forms known as myths or narratives, which, at a later stage, when the entire procedure is duplicated in the optical medium of writing, also become known as textual genres or theories. (106=172) […] The most general medium that makes both psychic and social systems possible and is essential to their functioning can be called “meaning” [Sinn]. (107=173) […] meaning is constituted by the distinction between actuality and potentiality (or between the real as momentarily given and as possibility). This implies and confirms that the medium of meaning is itself a form constituted by a specific distinction. (107=173/174) […] a form can be used as a medium for further formations. (108=176) […] an artwork’s material participates in the formal play of the work and is thereby acknowledged as form. (109=176)”

Luhmann, Niklas. Art as a Social System. Edited by David E. Wellbery. Translated by Eva M. Knodt. Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000. “(nnn=nnn)” refers to the pages in the English version and in the German original text (Luhmann, Niklas. Die Kunst der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1995) - bold type is ours.

Note on the diagram: Black font indicates words used by Luhmann (in the published translation), while words printed in grey indicate our interpretation and/or addition.

The Staircase of Text

NG, JS, PS

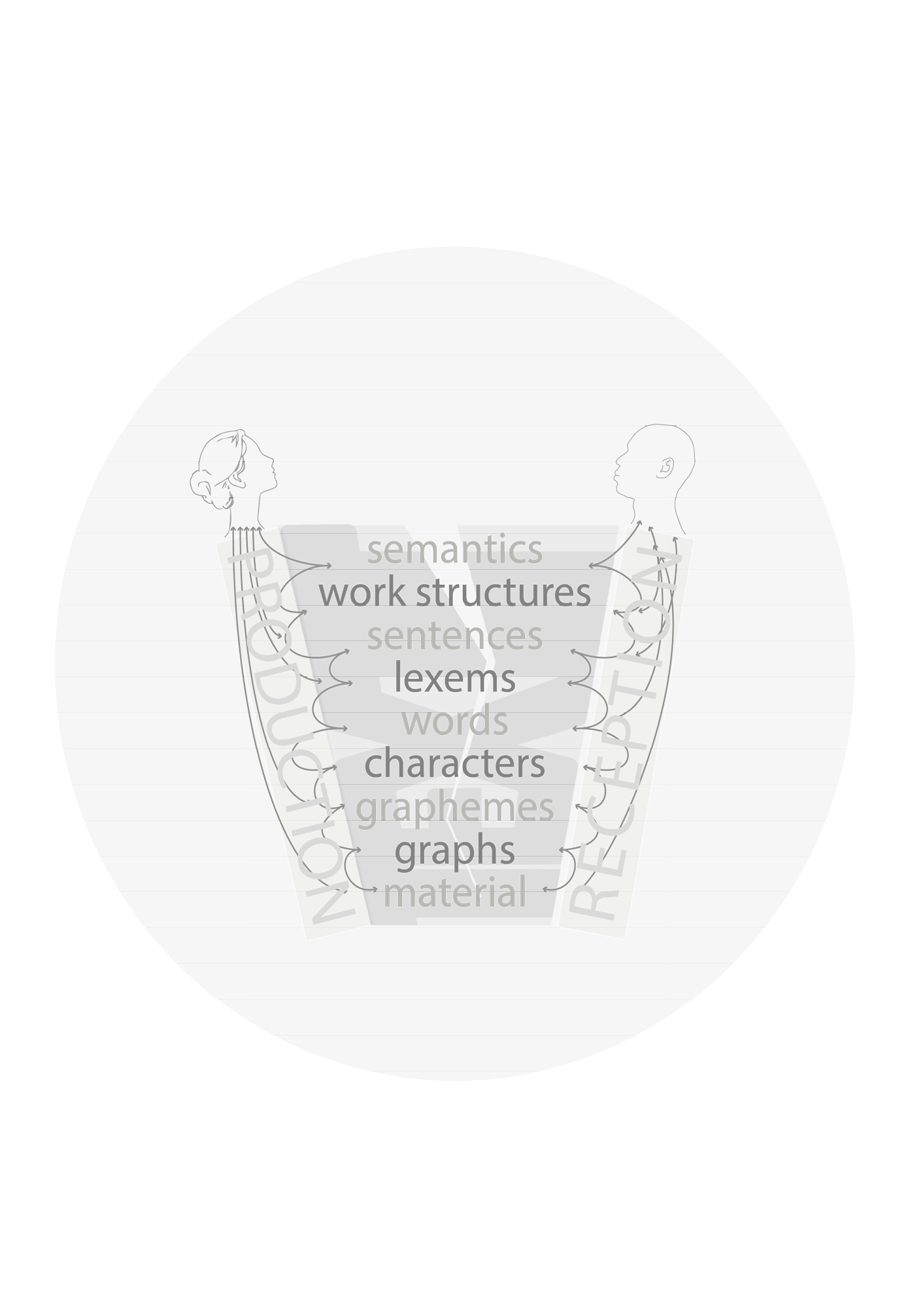

Digital Humanities: How we Read

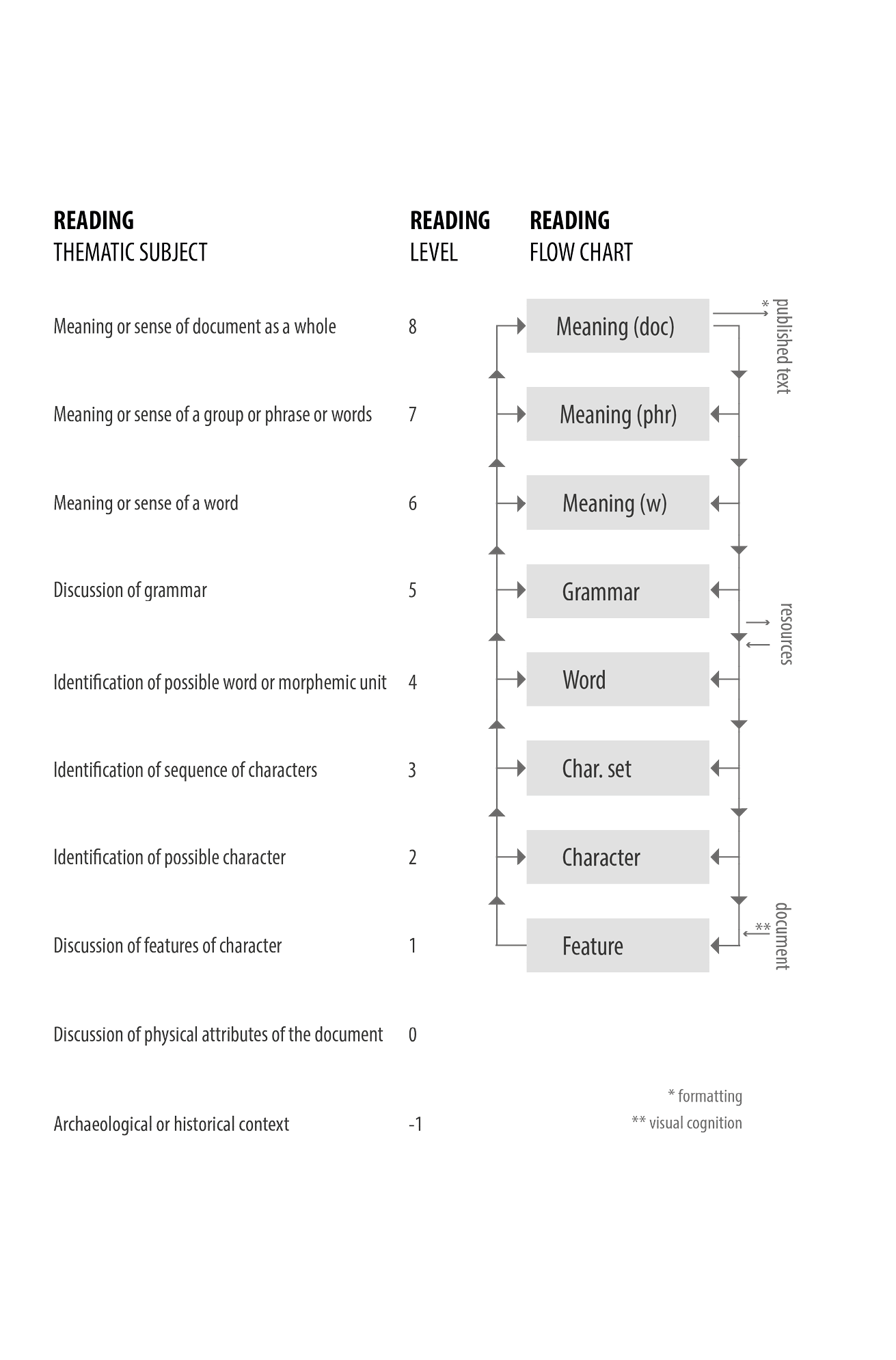

“[... T]he process of reading a text is not linear, building up one character at a time, but depends on the propagation of hypotheses, and the testing of these regarding all available information concerning a text.” (75-77) “It [the encoding scheme] resolves the reading process into a finite set of ‘modes of thought’, or ‘states’, which can be used to track the development of the reasoning process.” (49)

“An expert reads [a …] document by identifying visual features, and then incrementally building up knowledge about the document’s characters, words, grammar, phrases, and meaning, continually proposing hypotheses, and checking those against other information, until s/he finds that this process is exhausted. At this point a representation of the text is prepared in the standard publication format. At each level, external resources may be consulted, or be unconsciously compared to the characteristics of the document.” (82) “[E.g.:] Expert C begins by drawing some conclusions about the meaning of the document (level 8) before looking at the physical attributes (level 0). He then discusses what could be possible features of the text (level 1), before noting more physical attributes of the document (level 0). He then produces a word (level 4), looks at the characters within this word (level 2), and revises his initial word. Checking of the features (level 1) leads to identification of a character (level 2), the noting of a possible word (level 4) and a discussion of meaning of that word (level 6). In this manner the expert vacillates between the different levels in reading a document, until a resolution is reached regarding the sense of the document (level 8), or until he has exhausted all possibilities regarding the text.” (57) “While the lower level processes, such as the identification of features and characters, mostly relate to each other, and the upper levels, such as discussion of word meaning and meaning of document, mostly relate to each other, it is only the word level which shows a relationship with all the different types of information discussed.” (61) “The subjects which are discussed for the longest length of time per instance are the physical characteristics of the document, and the overall meaning of the text. The information regarding these levels is much more complex than the identification of characters and words, and tends to be discursive.” (63)

Terras, Melissa. Image to Interpretation: An Intelligent System to Aid Historians in Reading the Vindolanda Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Diagram: The Illustration is our merger of Terras, Melissa. Image to Interpretation, Table 2.1 and Figure 2.15.

Terras: Levels of Reading

Terras (redrawn PS, JS)

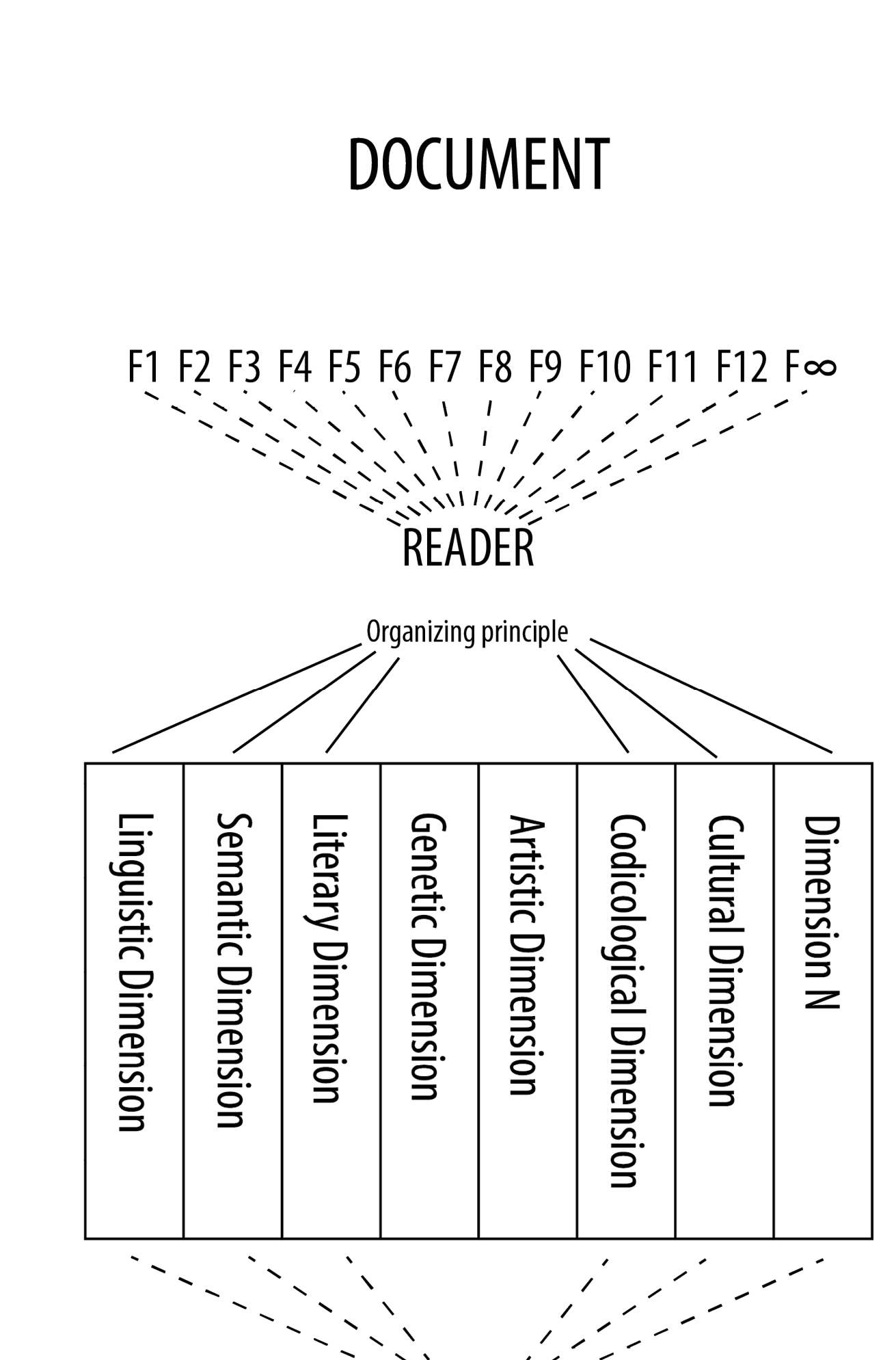

Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods

“The Text [...] is the meaning(s) that readers give to the subset of dimensions they derive from a document and that they consider interesting for their purpose. As a consequence, texts are immaterial and interpretative.” (42)

“Documents we take to be physical objects that contain some sort of inscribed information; therefore, a book is a document, a leaf with some writing on it is a document, a stone is a document. More generally, a document is a physical object that has some text on it[...]. [...] All documents (as defined here) contain verbal texts as well as other things: images, graphs, musical notation, arrows blotches, for instance, as well as including the ‘bibliographical codes’ discussed by McGann.” (40)

“Many people can read from the same document and understand slightly or radical different things, depending on their culture, their understanding, their disposition, their circumstances, and so on. There are facts in the object (the document), but their meaning is not factual, it is interpretative. For one reader the only interesting dimension could be the semantic [dimension ...] (what the text means, the plot, who is the murderer), for another could be the artistic [dimension ...]: maybe she/he cannot read the words written in an unfamiliar language, but she/he can still admire and make (some) sense of the iconography and its artistic value.” (42f)

“[...] Documents have infinite Facts (F1-F∞) which can be arbitrarily grouped (dotted lines) into Dimensions by a Reader; the result of which is the Text, which is then a function of the document conjured by a reader[. ...]” (43)

“These dimensions are only potentially available within a document, [...] the document itself has no particular meaning: it is an inert object with no particular significance.” (42)

“As dimensions potentially observable in a document are defined by the purpose of one’s interest in the document, it is therefore impossible to draw a stable and complete list of such dimensions.” (41)

“[... A] selection of dimensions that does not include consideration of the verbal content of a document is not a text, but must be something else. [...] Text has been defined as a particular selection of dimensions operated by a reader according to specific organising principle; the defining principle of which is the selection of an infinite set of facts with a purpose of study.” (44)

“The model proposed here [...] only concerns documents for which a verbal-content can be determined, since it is built to explain the editorial work.” (40f)

“[...A] text is a model that, among the facts selected by the reader, includes the verbal content of the document. We define then dimensions that include the verbal content of a document as Verbal Dimensions. Other selections which do not include the verbal content of the document are non-textual models.” (44)

Pierazzo, Elena. Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2015. [Original emphasises removed and terms used in the graphic highlighted in bold for the sake of consistency.]

Diagram: Pierazzo, Elena. Digital Scholarly Editin, p. 43, Figure 2.1: “Conceptual model of texts and documents”.

Pierazzo: Dimensions of Text

Pierazzo (redrawn JS, AW)

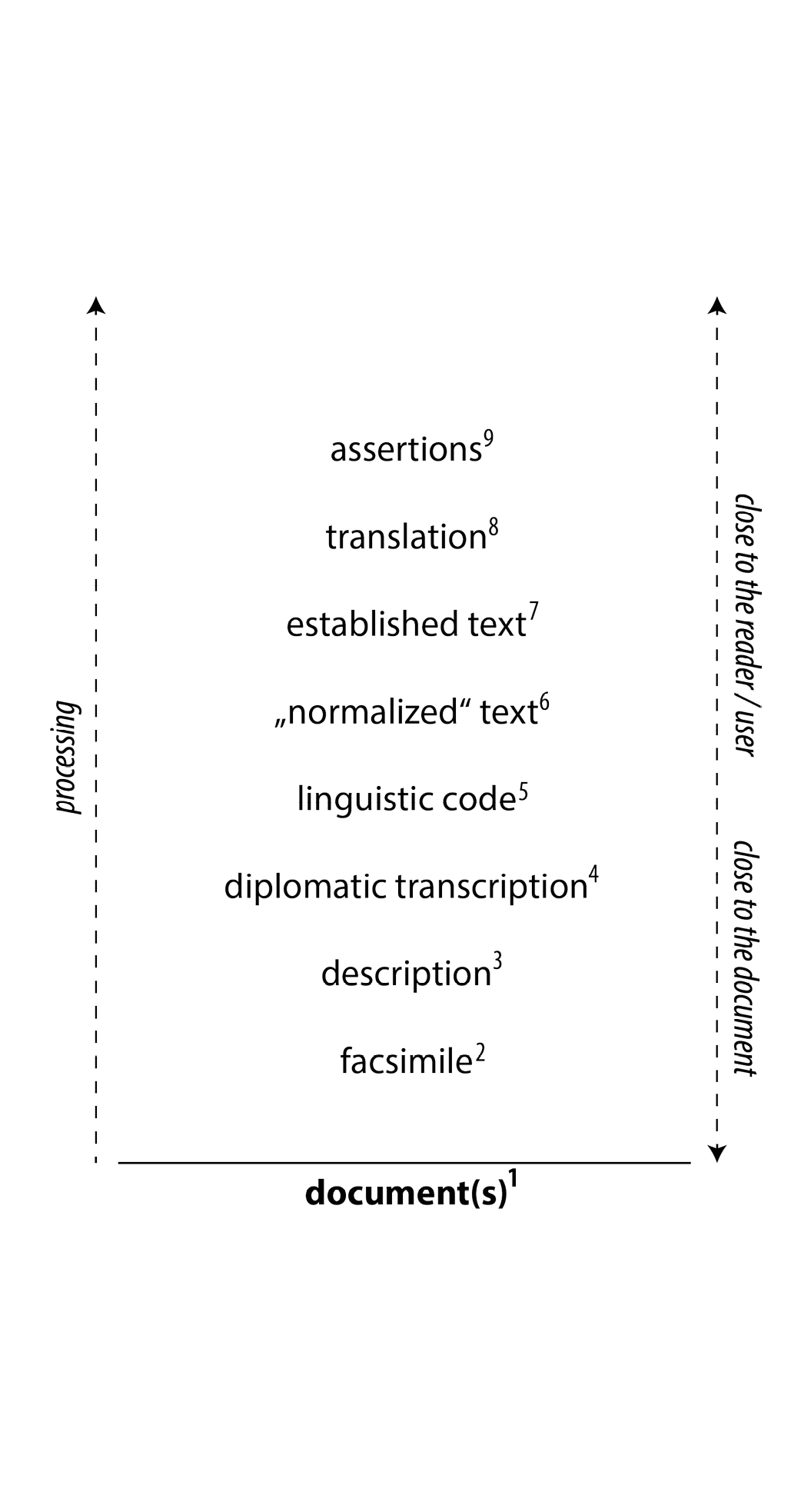

Digital Scholarly Editing: Textual Representation

In scholarly editing, presented texts claim to give a truthful copy, to convey what is essential for a given text or to realize the real text or its author’s intention. The various established modes of text representation in editing can be seen as layers, which are not discrete but should rather be seen as points on a continuous scale. Therefore, the scale given here is very much simplified.

Representations are the result of a double process: First, phenomena of a document are either recognized (as being important) or being ignored (filtered out) – secondly, the recognised phenomena are processed according to certain rules to transform them either into textual data or a media expression.

If textual representation is seen as a scale, the end points and directions are sometimes described as being ‘close to the document’ and ‘close to the reader’ respectively. To say that there is a gradual progress in ‘processing’ is another way of describing the scale.

- Texts are always given as documents. We do not encounter them in another form. Except for situations in which we ‘talk about a text’.

- Facsimiles are very close to the text as document. But even mechanical reproductions are means of filtering perception: think of image resolution, lighting, colors and material aspects..

- An external description (including bibliographic, material, contextual information) is a basic operation in representing a text. It is often done as a first step in creating a proxy for a text. As it can also be described as being highly synthetic, the position of this layer in the scale is disputable.

- The diplomatic transcription is as true to the document as possible. It does not change anything. However, there are many different levels of “truth” defined by what (which aspect of textuality) is to be observed and what can be neglected.

- The linguistic codes focus on text as a stream of alphabet characters (including punctuation and other elements of the target writing system).

- ‘Normalised’ is just an arbitrary label here. Replace it by ‘modernised’, ‘regularised’ or any other label that points at rule-based processes that intervene in and change text.

- In scholarly editing, to create the ‘best text’ or to reconstruct ‘author’s intention’ texts are sometimes constructed from several sources or are ‘emended’ against what can actually be found in the documents.

- A translation represents the same text, only in a different language.

- Texts are meant to convey information. This information can be extracted and represented as a set of assertions (like in RDF triples) or values (like in key-value pairs in an entity relationship model).

Cf. e.g. Sahle, Patrick. Digitale Editionsformen, vol. 3: Textbegriffe und Recodierung. Norderstedt: BoD 2013 [chapter: Dokument und Transkription], 251-340.

Sahle: Text as a Scale

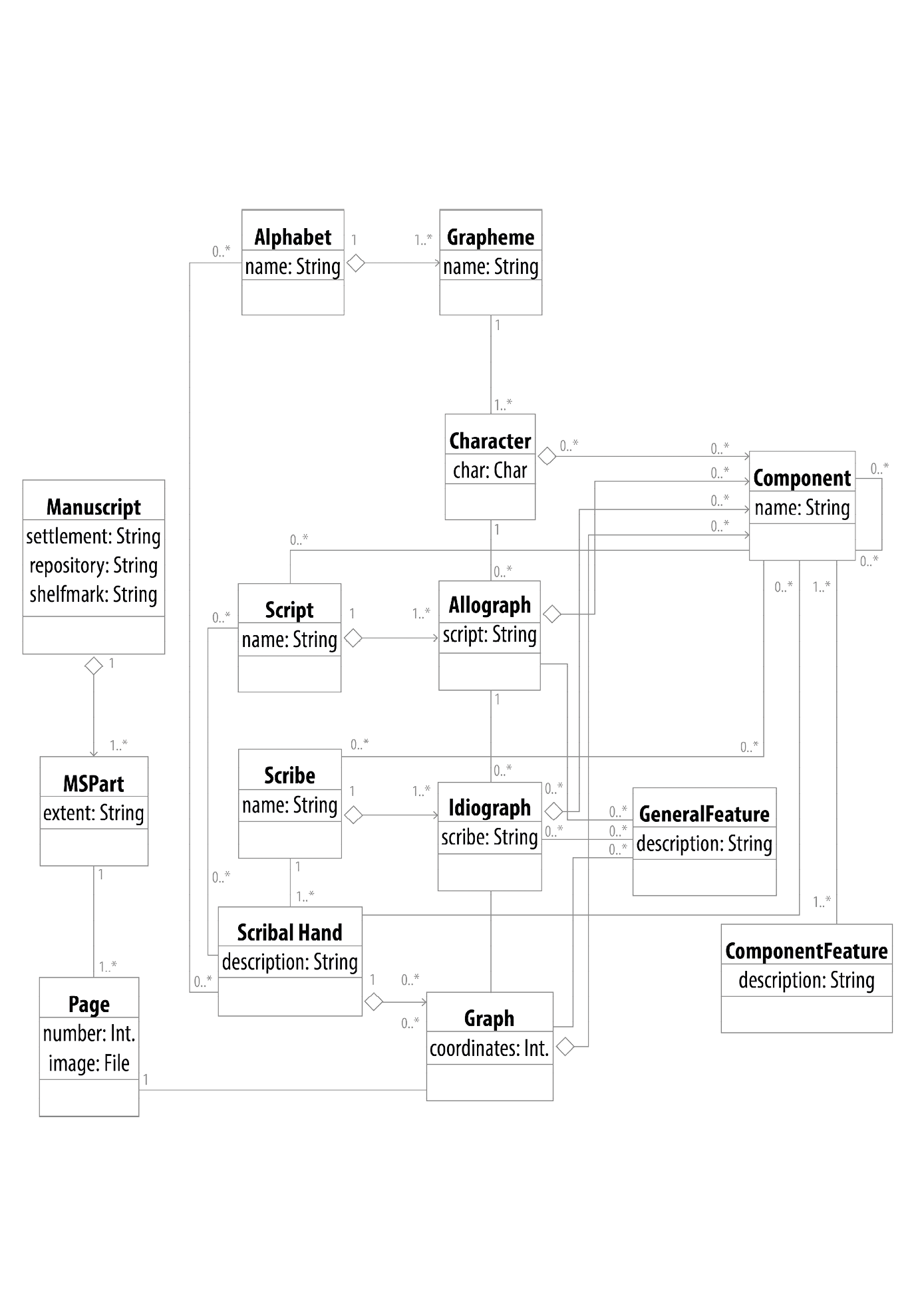

Digital Humanities: Understanding Historical Script

Texts are made of characters? Things are not that simple when you take a closer look …

“A grapheme is associated with one or more characters (for ‘Character’ see below). A character is made up of any number of components. A component in turn can be found in any number of characters and can have one or more features or indeed any number of further components.

A character can also be manifested in one or more allographs, and a set of allographs makes up a script. Allographs themselves can have components which have features, but allographs also have general features which are the aspects of ‘style’ […]. A set of allographs together makes up a script.

Each allograph can be manifested in any number of idiographs (which in turn have components and general features). A set of idiographs makes up the practice of a scribe.

Each idiograph can appear on the page as a graph; graphs have the usual set of general features and components, as well as a set of coordinates. The set of graphs makes up a scribal hand.

Scribal hands are written by exactly one scribe (but a scribe can write many scribal hands); a scribal hand may also be written in one or more scripts and may use one or more alphabets.”

Stokes, Peter A. ‘Describing Handwriting, Part IV: Recapitulation and Formal Model’. DigiPal (blog), 14 October 2011. http://www.digipal.eu/blog/describing-handwriting-part-iv-recapitulation-and-formal-model [Original emphases altered from uppercase into bold for the sake of consistency.]

See also Stokes, Peter A. ‘Modeling Medieval Handwriting: A New Approach to Digital Palaeography’. In Digital Humanities 2012, 382–85. Hamburg, 2012. http://www.dh2012.uni-hamburg.de/conference/programme/abstracts/modeling-medieval-handwriting-a-new-approach-to-digital-palaeography.1.html

Diagram: Stokes, Peter A. ‘Describing Handwriting, Part IV: Recapitulation and Formal Model’. DigiPal (blog), 14 October 2011, UML Diagram of the conceptual model. http://www.digipal.eu/blog/describing-handwriting-part-iv-recapitulation-and-formal-model. Redrawn by Julia Sorouri.

Stokes: Text as Script

Stokes

Information Science meets Electronic Texts: Renear and the Content Objects

“The essential parts of any document form what we call ‘content objects’, and are of many types, such as paragraphs, quotations, emphatic phrases, and attributions. (3) [...] Most content objects are contained in larger content objects, such as subsections, sections, and chapters. (4) [...] Smaller content objects that occur within a larger one, such as the sections within a chapter, or the paragraphs, block quotes, and other objects within a section, occur in a certain order. This ordering is essential information, and must be part of any model of text structure. Combining these essential elements, we can describe a text as an ‘ordered hierarchy of content objects’, or ‘OHCO’. (4)”

DeRose, Steven J., David G. Durand, Elli Mylonas, and Allen H. Renear. ‘What Is Text, Really?’ Edited by Terry R. Girill. Journal of Computer Documentation 21, no. 3 (1997): 1–24. [First published in 1990 as ‘What is Text, Really?’ Journal of Computing in Higher Education 1, no. 2 (December 1990): 3–26.]

“OHCO-1: Text is an ordered hierarchy of content objects.”

“Book: front matter, back matter, body, chapter, section, paragraph [...]”

Renear, Allen H., Elli Mylonas, and David Durand. ‘Refining Our Notion of What Text Really Is: The Problem of Overlapping Hierarchies’, 1993. http://cds.library.brown.edu/resources/stg/monographs/ohco.html. [First presented at the annual joint meeting of the Association for Computers and the Humanities and the Association for Literary and Linguistic Computing, Christ Church, Oxford University, April 1992. Later published as ‘Refining Our Notion of What Text Really Is’. In Research in Humanities Computing, edited by Nancy Ide and Susan Hockey, Vol. 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.]

The OHCO approach is a strange case: As a model it uses a property of a certain text technology (here: text markup) to explain what text is: text is an ordered hierarchy of content objects, because markup (with its double principles of (textual) order and (element) hierarchy) seems so suitable to represent text. The argument here is: “the truth is in the practicality” or “if the model works, it must be right – also in its structural characteristics”.

“[... T]he reason this model of text is so functional and effective is that it reflects what text really is.”

Renear, Allen H. ‘Representing Text on the Computer: Lessons for and from Philosophy’. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 74, no. 4 (1992): 221–48, 221.

“The comparative efficiency and functionality of treating texts *as if* they were OHCOs is best explained, according to this argument, by the hypothesis that texts *are* OHCOs.” (#5.1.6)

Renear, Allen H. ‘Theory and Metatheory in the Development of Text Encoding’, 1995. https://web.archive.org/web/19970401032906/www.rpi.edu/~brings/renear.target

“[... T]ext is an “Ordered Hierarchy of Content Objects” (OHCO), and descriptive markup works as well as it does because it identifies that hierarchy and makes it explicit and available for systematic processing.”

Renear, Allen H. ‘Text Encoding’. In A Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Susan Schreibman, Raymond George Siemens, and John Unsworth, 218–239. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004, 224f.

The OHCO Model

PS, NG, JS

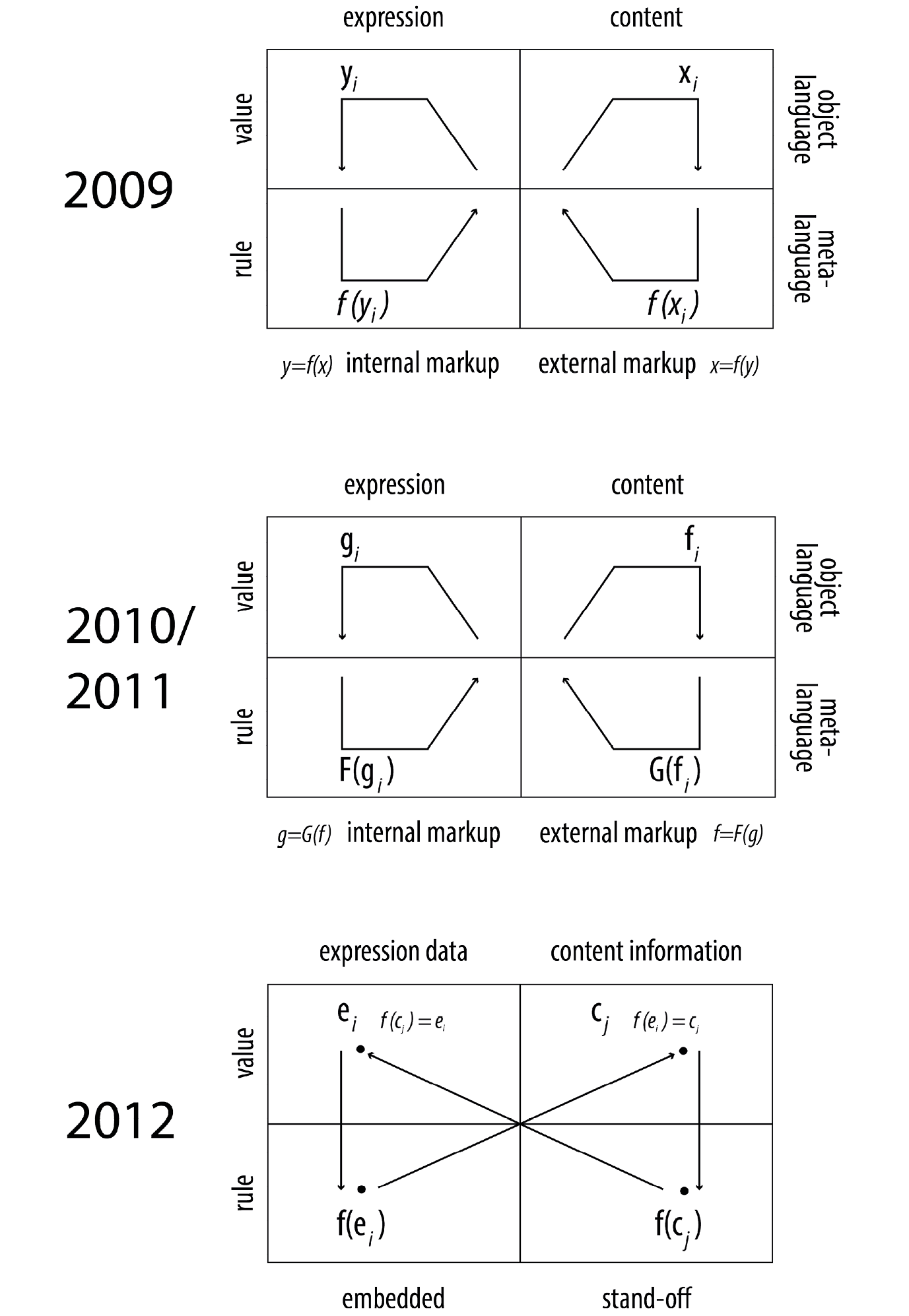

Philosophy and Technology: On Markup

“It is precisely this kind of diacritical ambiguity possessed by markup that can be exploited to devise a dynamic model of the text. Such a model can be expounded through a diagram, a kind of multidimensional matrix, whose elements are connected by a series of operations. The resulting process is a kind of loop. [...]

The structural elements of the expression of the text, represented by embedded or internal markup, are here arranged in the first column of the table. In the second column we find structural elements of the content of the text, as described by data modelling or semantic description languages, that can also be regarded as a form of markup, albeit external. Now, one and the same internal markup construct can be seen either as belonging to the object language of the text, in as much as it is a structural element of its expression, or else as a representation of that very element, separate from the text and belonging to a metalanguage. These two aspects of a markup construct can be severed, and the operation that converts the one into the other is a logical move, that rests on the assumption that the ‘meaning of the markup’ is ‘the set of inferences about the document that are licensed by the markup.’45 Accordingly, this move posits a markup construct as an inference-licence. If so, we can place it in the lower part of the first column and regard it, to recall Gilbert Ryle’s famous description, as an ‘inference-ticket,’ or a rule-statement ‘to move from asserting factual statements to asserting other factual statements’46 – in our case, to infer from a statement about an observed textual property, to a statement about a property of its content. That content property, in its turn, expressed in a semantic annotation language, can be placed in the upper compartment of the second column as the value of the operation prompted by the instruction found in the lower compartment of the first column. All this means that markup can have both ‘descriptive’ and ‘performative’ force,47 and what has just been said about markup constructs, or the structural elements of the expression of the text, applies also to semantic annotation constructs, or the stuctural elements of its content. We can therefore posit a semantic description as a rule, place it in the lower part of the second column, and move from it to the value of the operation it commands, ending up again with a property of the expression, in the upper part of the first column. And so the cycle is complete.”

45 C. M. Sperberg-McQueen, C. Huitfeldt and A. Renear, ‘Meaning and Interpretation of Markup,’ in Markup Languages: Theory & Practice, 2:3 (2000), 215–234, p. 231.

46 G. Ryle, The Concept of Mind, London, Hutchinson’s University Library, 1949 , p. 121.

47 Renear, ‘The descriptive/procedural distinction’ [in Markup Languages: Theory & Practice, 2:4 (2001)] p. 419 (134f).

Text: Buzzetti, Dino. ‘Digital Text Representation: Expression and Content’. In Contexts: Proceedings of ANPA 31 (Alternative Natural Philosophy Association, 31st International Meeting, Wesley House, Cambridge, August 2010), edited by A. D. Ford, 124–145. London: ANPA, 2011.

Diagrams: Buzzetti, Dino. ‘Digital Editions and Text Processing’. In Text Editing, Print, and the Digital World, edited by M. Deegan and K. Sutherland, 45–62. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009, Figure 3.1

Buzzetti, Dino. ‘Digital Text Representation: Expression and Content’. In Contexts: Proceedings of ANPA 31 (Alternative Natural Philosophy Association, 31st International Meeting, Wesley House, Cambridge, August 2010), edited by A. D. Ford, 124–145. London: ANPA, 2011.

Buzzetti, Dino, and Manfred Thaller. Beyond Embedded Markup. Hamburg, 2012, Figure 1.

Buzzetti: Text as Expression and Content

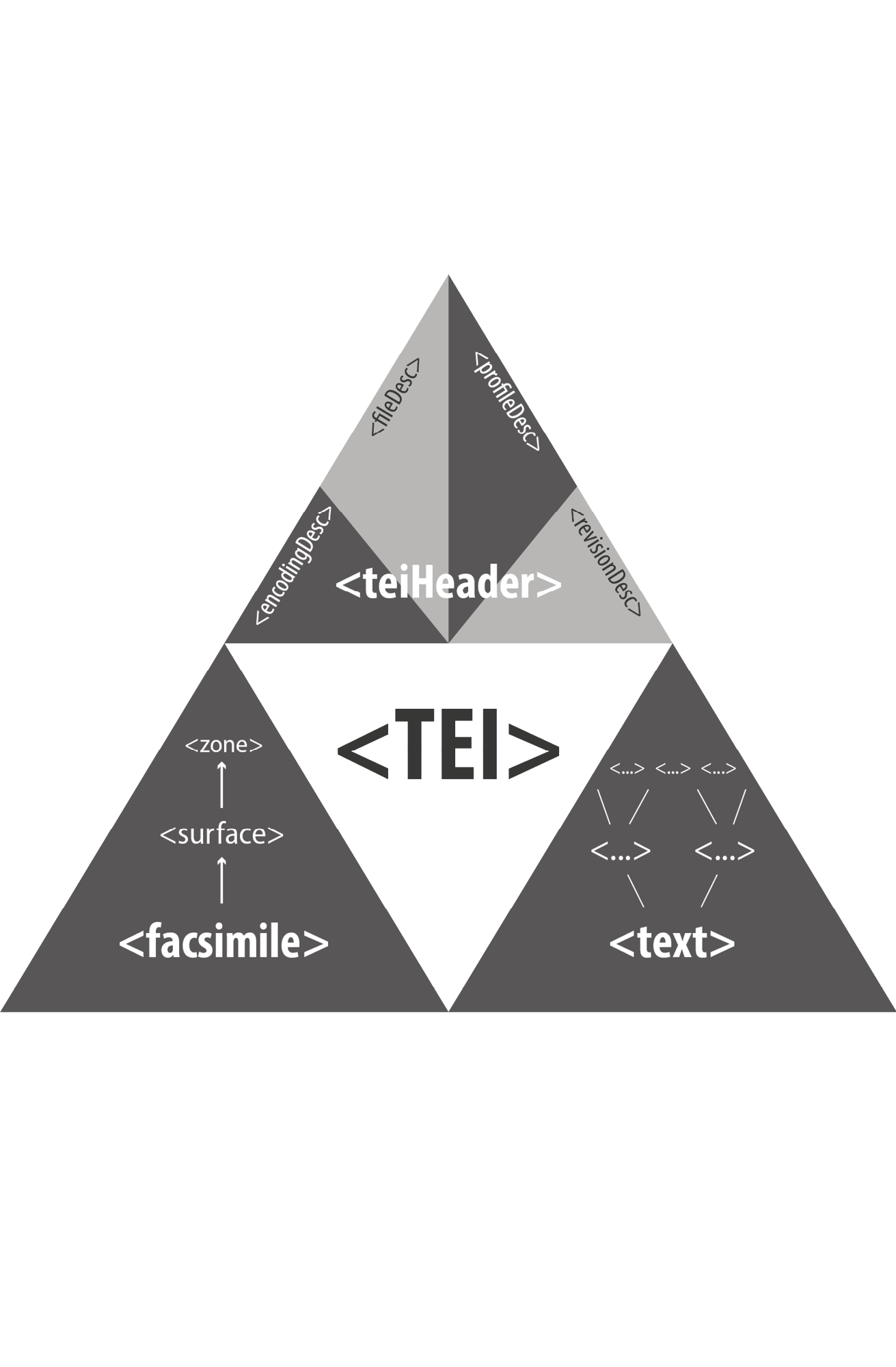

Digital Humanities: Text According to the TEI

The TEI (or more precise: the guidelines of the TEI) are probably the most important standard for the information rich representation of texts in electronic form. With hundreds of elements for the description of textual structures and phenomena it embodies a pluralistic theory of text, developed over three decades by a large number of textual scholars representing various fields of research.

In a formal view which would cover all possibilities of text encoding with TEI and would regard all elements, modules, classes and handbook chapters, the set of TEI tags, attributes and the rules for their usage and nesting would lead to a confusing image of vast options and eventualities.

In a more pragmatic view on basic assumptions and common practices however, it can simply be said that the TEI nowadays has a threefold approach towards text. As a representation of text, a TEI instance always contains (1.) a section (TEIHeader) that describes the text as an object or work and its representation by data. That description in turn is made up of four important areas of information with their own widely ramified structures. The text itself is represented (2.) either following a material or visual paradigm, where a text bearing object becomes a facsimile, further subdivided into surfaces (like pages) and (writing) zones – again containing potentially complex information structures. Or (most often) the text is represented (3.) in accordance to a text logic paradigm that is based on a stream of character with embedded or stand-off annotations that describe further structures and add transcriptive or interpretative information to it. Within the abundance of elements to express textual information, they can roughly be divided into those that describe genre specific structures and phenomena and those that help to encode rather analytic or interpretative knowledge about the text. The set of elements and attributes however is so rich, that a sharp distinction cannot be made and many other divisions and classifications of the TEI vocabulary are likewise possible.

It is noteworthy that the material and the logic view on text are not exclusive but that both can be used at the same time and that they may well refer to each other to capture all aspects of a text and together yield a complete picture of our understanding of that text.

TEI: “[C]ontains a single TEI-conformant document, combining a single TEI header with one or more members of the model.resourceLike class. Multiple TEI elements may be combined to form a teiCorpus element.”

teiHeader: “[S]upplies descriptive and declarative metadata associated with a digital resource or set of resources.”

facsimile: “[C]ontains a representation of some written source in the form of a set of images rather than as transcribed or encoded text.”

text: “[C]ontains a single text of any kind, whether unitary or composite, for example a poem or drama, a collection of essays, a novel, a dictionary, or a corpus sample.”

TEI Consortium. ‘P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange (Version 3.4.0)’, n.d. http://www.tei-c.org/guidelines/p5/.

TEI’s Triangle of Text

PS, JS

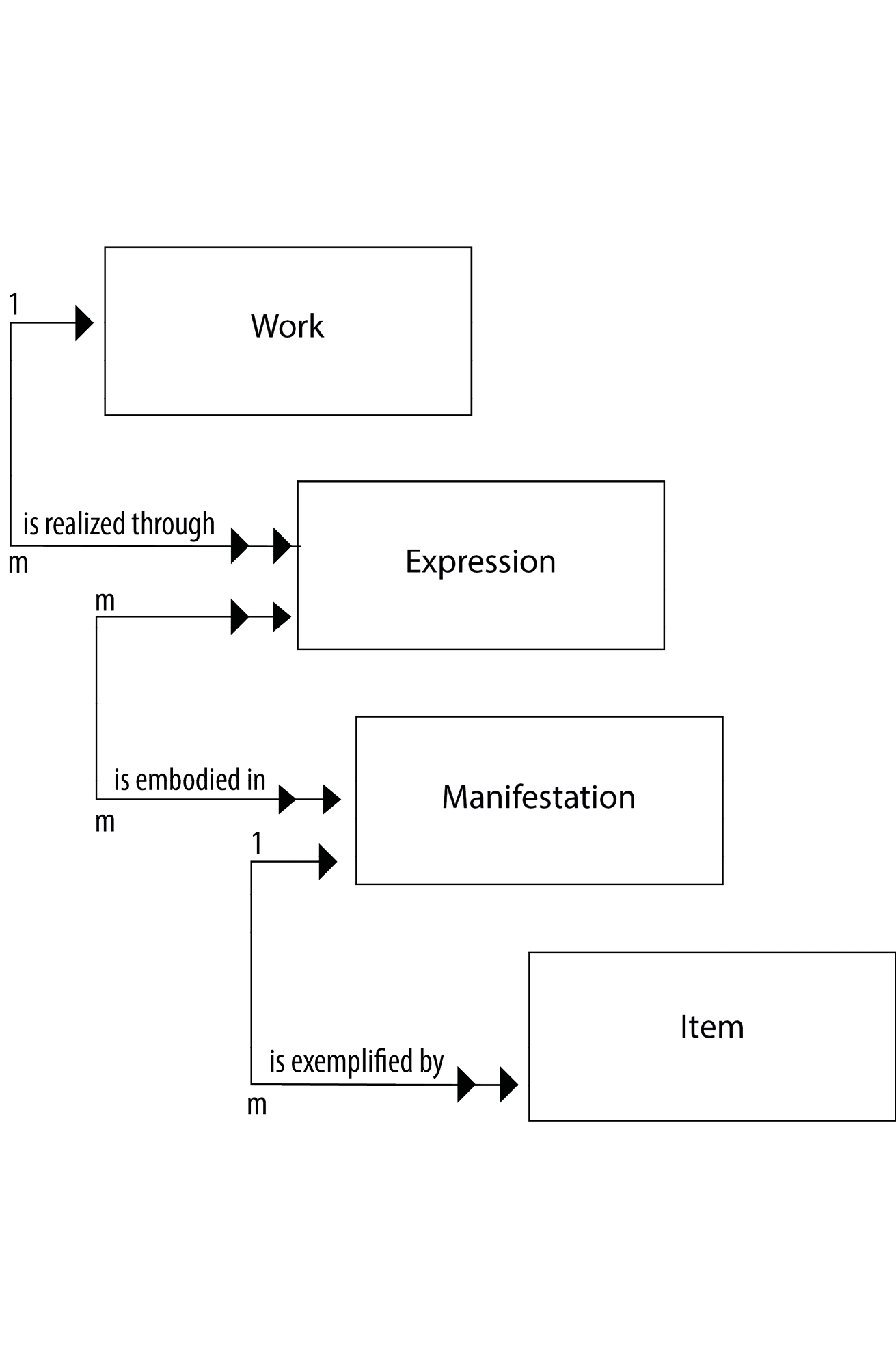

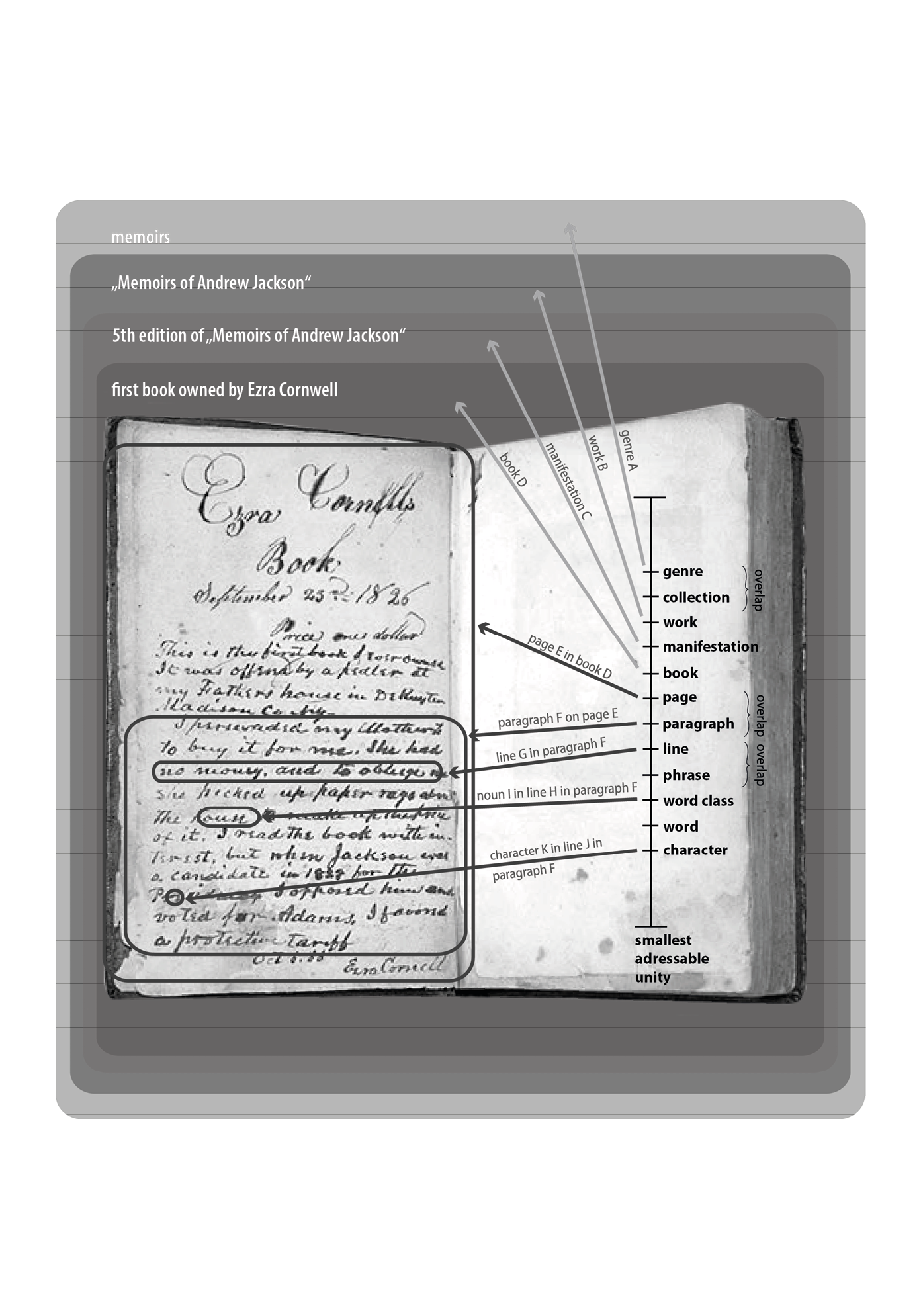

Bibliography, Library and Information Science

FRBR

“The entities in the first group [...] represent the different aspects of user interests in the products of intellectual or artistic endeavour. The entities defined as work (a distinct intellectual or artistic creation) and expression (the intellectual or artistic realization of a work) reflect intellectual or artistic content. The entities defined as manifestation (the physical embodiment of an expression of a work) and item (a single exemplar of a manifestation), on the other hand, reflect physical form.

[... A] work may be realized through one or more than one expression (hence the double arrow on the line that links work to expression). An expression, on the other hand, is the realization of one and only one work (hence the single arrow on the reverse direction of that line linking expression to work). An expression may be embodied in one or more than one manifestation; likewise a manifestation may embody one or more than one expression. A manifestation, in turn, may be exemplified by one or more than one item; but an item may exemplify one and only one manifestation.” (13f)

“The first entity defined in the model is work: a distinct intellectual or artistic creation. A work is an abstract entity; there is no single material object one can point to as the work. (17) [...] The second entity defined in the model is expression: the intellectual or artistic realization of a work in the form of alpha-numeric, musical, or choreographic notation, sound, image, object, movement, etc., or any combination of such forms. An expression is the specific intellectual or artistic form that a work takes each time it is ‘realized.’ (19) [...] The third entity defined in the model is manifestation: the physical embodiment of an expression of a work. The entity defined as manifestation encompasses a wide range of materials, including manuscripts, books, periodicals, maps, posters, sound recordings, films, video recordings, CD-ROMs, multimedia kits, etc. As an entity, manifestation represents all the physical objects that bear the same characteristics, in respect to both intellectual content and physical form. (21) [...] The fourth entity defined in the model is item: a single exemplar of a manifestation. The entity defined as item is a concrete entity. It is in many instances a single physical object (e.g., a copy of a one-volume monograph, a single audio cassette, etc.). There are instances, however, where the entity defined as item comprises more than one physical object (e.g., a monograph issued as two separately bound volumes, a recording issued on three separate compact discs, etc.). (24)”

IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Final Report, 2009. https://archive.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/frbr_2008.pdf

Diagram: IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Final Report, 2009, Figure 3.1, 14. Redrawn by Julia Sorouri. [Added cardinalities to arrows.]

FRBR Group One: Hierarchy of Textual Entities

PS, NG, JS

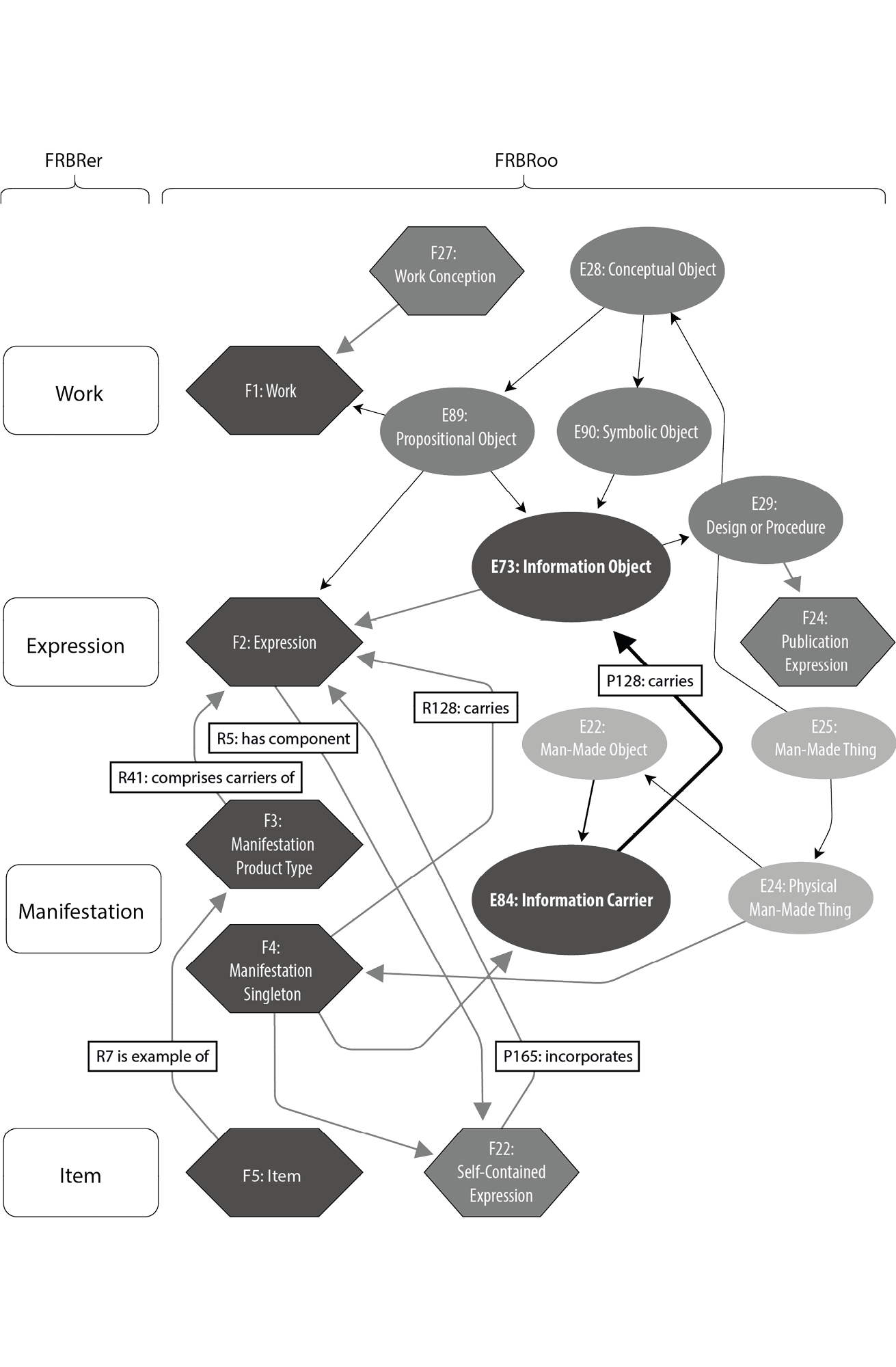

Library and Information Science in the Digital Humanities

FRBRoo

F1 Work

“This class comprises distinct concepts or combinations of concepts identified in artistic and intellectual expressions, such as poems, stories or musical compositions. Such concepts may appear in the course of the coherent evolution of an original idea into one or more expressions that are dominated by the original idea. A Work may be elaborated by one or more Actors simultaneously or over time. The substance of Work is ideas. A Work may have members that are works in their own right.” (54)

F2 Expression

“This class comprises the intellectual or artistic realisations of works in the form of identifiable immaterial objects, such as texts, poems, jokes, musical or choreographic notations, movement pattern, sound pattern, images, multimedia objects, or any combination of such forms that have objectively recognisable structures. The substance of F2 Expression is signs. Expressions cannot exist without a physical carrier, but do not depend on a specific physical carrier and can exist on one or more carriers simultaneously. Carriers may include human memory.” (55f)

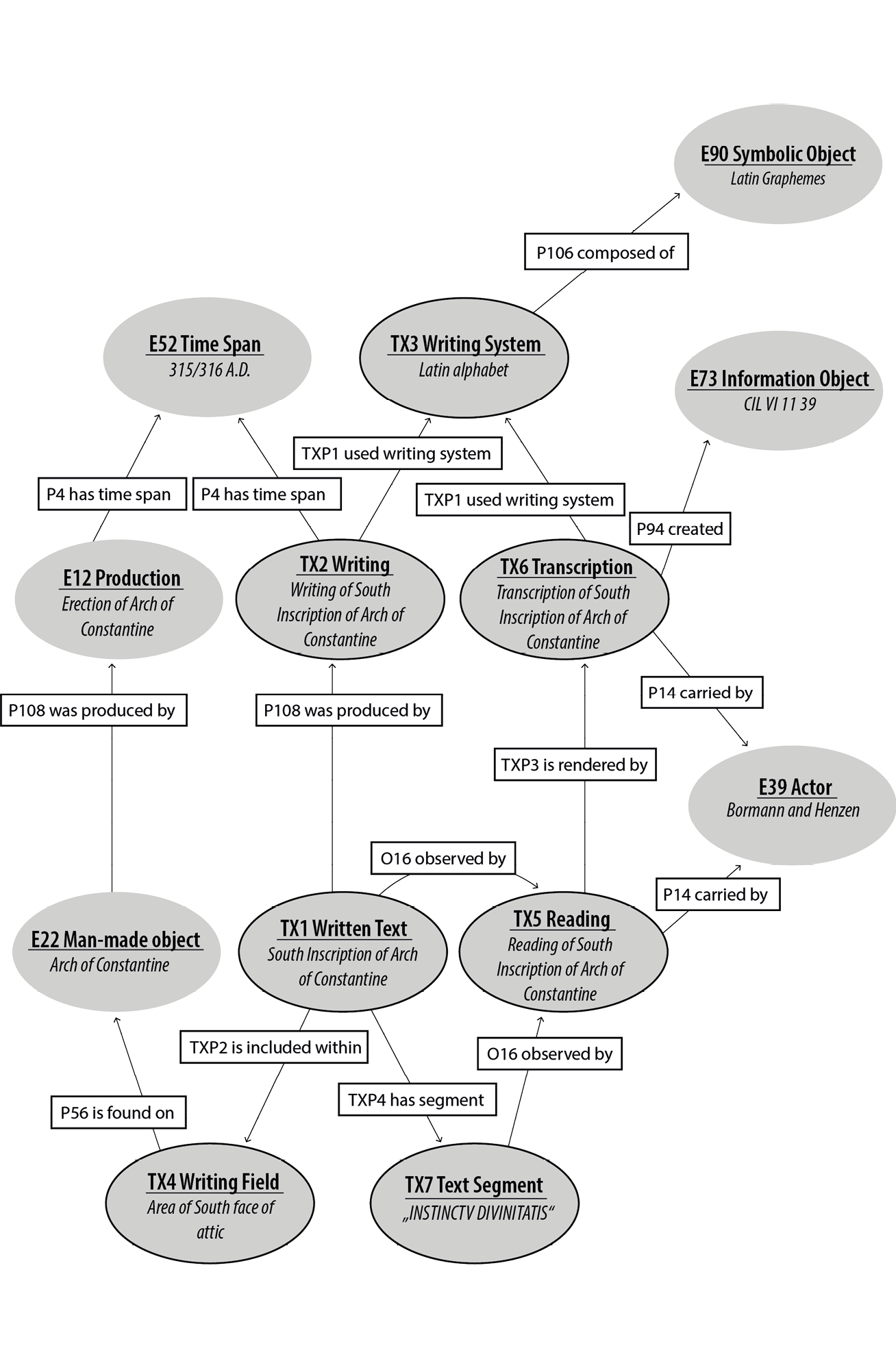

F3 Manifestation Product Type