7. Shikama Totsuji: Music Reform and a Nationwide Network

©2024 Margaret Mehl, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0374.07

I intended, by importing music from the civilized countries (bunmei koku) to reform the music of our country and with this intent, from about Meiji 7 or 8 [1874 or 1875] I researched the various musics of our country. All the same, I achieved nothing. But finally, fortunately, I entered the Ministry of Education’s Music Research Institute and for the first time I was able to study Western music thoroughly in accordance with my wishes […]. 1

Totsudō is not a musician: carrying a brush in one hand and a koto in the other, he writes and draws as he continues his pilgrimage through all the provinces.2

Shikama Totsuji’s activities were, arguably, just as significant as Isawa’s for the transformation of musical culture in the late nineteenth century. His many initiatives highlight the importance of individual actors, as does the content of Ongaku zasshi, which includes reports of the activities of other individuals who did not hold an official appointment, or, if they did―such as teachers in public schools―worked well beyond the scope of their employment. 3

How exactly Shikama (1859–1928) came to play the role he did, remains somewhat of a mystery: little is known about his early education, and even less about his early experience of music, whether Japanese or Western. At the time of his birth as the first son of Shikama Nobunao, his father, a vassal of the house of the Date (the rulers of Sendai domain), was responsible for the Date’s horses (baseika). After 1868, Nobunao selected and bred riding horses for the emperor.4 He was a prominent figure in the local stock-raising business. His second son Shikama Jinji (1863–1941) became a pioneer of music education in Sendai (see Chapter 9).5 Better known than either Totsuji or Jinji is Nobunao’s fourth son Kōsuke (1876–1937), a vice admiral who fought in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–05 and in the First World War.6

Shikama Totsuji received his early training in the Confucian classics at the domain school Yōkendō. The school admitted boys from the age of eight, so Totsuji is likely to have been enrolled in 1866 or 1867. There was no fixed graduation age. The curriculum, as was usual for domain schools, included military training and book learning, mostly in the form of the Chinese classics, and Yōkendō printed its own copies of them.7 A distinguishing feature of Yōkendo was that noh chanting (yōkyoku) had been introduced as a subject of ‘rites and music’ in 1817 and thus became part of education for the domain’s vassals.8 If, as his biographer states, Totsuji studied there for eight years, he would have been among a minority of students who remained there through the Restoration wars, when the school suffered severe disruption. From 1869 the school underwent several transformations.9 Whether Shikama stayed on or whether he changed to one of the new schools specializing in Western subjects is not known. He may well have continued his studies in Tokyo. He reportedly spent two years studying both English and kangaku at Dōjinsha, the private academy opened in 1873 by Nakamura Masanao (1832–91), a founding member of the Meiji Six Society.10 Whatever the details of his education, Totsuji was subsequently employed by Miyagi prefecture and married Tatsu, a geisha (also known as Kotatsu; c.1862–1940).11 The couple had four sons and six daughters, of whom three daughters survived them.12 All three became musicians.

Totsuji himself claimed that he had already begun to study music in the 1870s.13 Even if we take his claim with a pinch of salt, he does appear to have developed an interest in music early in life and learnt various musical instruments. In 1881 he reportedly published sheet music for the gekkin, the popular fretted lute with a round body, used in Ming-Qing music.14 The space given to Ming-Qing music in Ongaku zasshi suggests that he had a special interest in that music. On 3 December 1884, Totsuji was admitted onto the short training course for prospective music teachers at the institute of the Music Investigation Committee in Tokyo. Earlier that year all the prefectures had been invited to send suitable candidates. Only twelve of them did (Fukuoka sent four).15 Miyagi prefecture sent Totsuji’s younger brother Jinji, who at only eighteen years of age had become the principal of a local primary school. Whether the prefecture also sent Totsuji, who was not employed as an educator, or whether his strong interest in music made him persuade the authorities to let him attend too we cannot be sure.16 The Institute was, presumably, happy to have him, as the number of applicants fell below the Institute’s quota.17 The nine-month course consisted of shōka, reed organ, koto and kokyū (Japanese bowed lute). The Japanese instruments were used, sometimes in modified forms, as a substitute for the keyboard and the violin, although most schools made every effort to purchase at least one reed organ.

After graduating in July 1885,18 Shikama Jinji returned to Sendai, while Shikama Totsuji remained in Tokyo. For the next few years he taught at Tokyo Normal School (until 1888). He is also listed as a teacher (of what exactly is not recorded) at the Tokyo Academy of Music from 1892 to 1894.19 Most of his wide-ranging musical activities, however, he conducted privately. He taught at the Tōkyō Shōkakai in the Yūrakuchō district of Tokyo. Established in 1885, this was the first of several private music schools offering short courses in music for primary school teachers. He also engaged in publishing, collecting instruments and even inventing a new one himself, as well as performing and organizing concerts.

In May or June 1896 Totsuji returned to Sendai, ostensibly because of his father’s illness (Nobunao died in December 1897).20 Possibly, he also saw more scope for his pioneering activities in the provincial town, where there were far fewer men with even his low level of musical training. For the next ten years or so, he continued his pioneering activities in Sendai. He may have moved back to Tokyo with his family in around 1906, but left his family to travel around the Tohoku region, a lifestyle that a newspaper article in 1909 unflatteringly described as hōrō (roaming, wandering about like a vagabond).21 For a while he stayed in Maebashi in Gunma prefecture, where he reportedly lived by his writing.22 He acquired a concubine, Saitō Sumi from Gunma prefecture, with whom he fathered two children, a son (born in 1916 in Tochigi prefecture) and a daughter (born in 1918 in Chiba prefecture).23 Judging from the places of birth of his youngest children, Totsuji’s itinerant life continued into his final years. He died in Tokyo on 7 September 1928.

Global Ambitions and a Nationwide Network: The Musical Magazine (Ongaku zasshi)

The publication of Ongaku zasshi may well have been Shikama Totsuji’s greatest achievement. As Shikama himself suggested, the time was indeed ripe for a magazine dedicated to music. Government efforts to disseminate music education nationwide had just begun, and Western music had no mass appeal. Meanwhile, traditional Japanese music and the immensely popular Ming-Qing music flourished. The world of traditional Japanese music, while still fairly closed, with its strict division into genres, was changing: its practitioners were making use of the new opportunities offered by the abolition of monopolies and guilds and other economic and social changes.

Ongaku zasshi was remarkable in more ways than one. First, from the very first issue (25 September 1890), it included an English title: The Musical Magazine. This, together with occasional reports about musical events outside Japan, suggests that Shikama perceived his initiative as having significance beyond Japan. In his launching statement, moreover, Shikama Totsuji compared his initiative with similar ones abroad. Even in the capital of France, ‘well-known for its music’, publishers of musical magazines struggled, he stated with reference to an unnamed weekly musical magazine and the weekly music supplement of Le Figaro.24 Second, regular reports about musical activities from locations across Japan helped create a nationwide network of people (mostly, but not exclusively, teachers) engaged in promoting music. Third, true to the idea of combining the best of all musical worlds, Ongaku zasshi included articles and reports on Western and Japanese music, as well as Ming-Qing music.25 This inclusiveness may well have represented a major contribution to establishing ongaku (i.e. ‘music’) as a concept. The broad coverage was in keeping with Totsuji’s advocacy of music reform, for which Ongaku zasshi was to provide a forum.

Music had previously been discussed in other journals, such as Tōyō gakugei zasshi (The Eastern journal of learning and the arts), established in 1881, and Dai Nippon Kyōikukai zasshi (Journal of the Education Society of Japan), established in 1883.26 But Ongaku zasshi provided a specialized forum for all those who embraced the promotion of music as a cause―not least the increasing number of young men and women who, like Totsuji himself, graduated from the Tokyo Academy of Music and, unlike Totsuji but like his brother Jinji, went on to teach in provincial schools. Subscribers to Ongaku zasshi received a monthly reminder that they were part of a larger community, linked to other parts of the country and to its capital, and even to the wider world.

Besides regular news about the activities of the Tokyo Academy of Music and other institutions, Ongaku zasshi included reports from different regions, probably supplied by teachers at the prefectural teacher training colleges, several of whom would have been Shikama’s fellow graduates. Reports from outside Japan informed readers about activities in the Japanese community in Korea and in Taiwan after it became a Japanese colony in 1895, and even North America or Europe. The regional reports often represented the personal impressions of the reporter, who may well have been a local actor himself and keen to present his achievements in the best light. This is certainly true of the reports about Sendai, several of which detailed Shikama Totsuji’s own activities. They give us valuable information about local institutions and societies, the activities of individuals, and performances; they often included concert programmes.

The magazine’s other regular sections were: Music (articles); Songs; Contributions; Miscellaneous Reports; Reference; Miscellaneous Notes; Company Notifications; and Adverts: the first few issues included a serial and some issues had a ‘Question and Answer’ section.27 Many of the articles were written by Totsuji himself (under various pen names), at least until issue no. 58, published on 28 May 1896, in which Totsuji announced his return to Sendai. Until then the magazine was published monthly apart from one or two delays. Issue no. 59 was not published until 8 August 1896, by which time Ongaku zasshi had been taken over by Kyōeki Shōsha, a major trading company which dealt in educational materials, including sheet music and musical instruments. From no. 61 (25 September 1896), the name was changed to Omukaku.28 The contents changed too. From no. 59 a section with literary contributions (Bun’en) was introduced, as were longer, serialized articles by leading experts. Just over a year later, in February 1898, no. 77 became the last issue to be published, although there is nothing to indicate this in the issue itself. Presumably financial difficulties prevented its continued publication.29 Shikama Totsuji’s name appears in Ongaku zasshi/Omukaku only a few times after he ceased publishing the journal. In effect, it ceased to be his work after May 1896.

For the roughly five years Shikama Totsuji himself edited and published Ongaku zasshi, it provided a wealth of information and food for discussion on subjects such as musical theory, particularly harmony (regarded as the defining characteristic of Western music); Western, Japanese, and Chinese musical instruments and musical genres; as well as Western composers and musicians, starting with Jean-Baptiste Lully in the first issue, perhaps because of his significance as a composer of music played by the French-trained band of the Japanese army. Presumably, one or both of the returnees from music studies in France acted as Totsuji’s informers.30 Other topics included discussions of the role of music in education, public morality, patriotism, health, and Buddhism.

Songs, in staff or cipher notation and often composed by Totsuji himself, were another regular feature of Ongaku zasshi, as were announcements and adverts for his own publishing company, Ongaku Zasshi Sha, and other adverts, mainly for institutions offering music courses and for educational material, sheet music, and musical instruments. Around the time Ongaku zasshi was launched, Yamaha Torakusu (1851–1916) and Suzuki Masakichi (1859–1944) embarked on the nationwide distribution of their instruments, and Ongaku zasshi regularly carried adverts for Yamaha reed organs and Suzuki violins. Totsuji initially tried to develop the domestic production of violins himself, but gave up when he realized that Suzuki had beaten him to it.31

The value of Totsuji’s magazine as a primary source regarding musical activities in the 1890s for historians today is obvious. But how was Ongaku zasshi received in its time? The magazine itself gives us some clues, as do other contemporary publications.32 We do not know how many copies of each issue were printed and distributed,33 but issue no. 2 lists forty-seven places where the magazine was on sale, and no. 5 lists 107. Just over half of the locations were outside Tokyo. In several issues, ‘supporters’ (the nature of their support is not specified) are listed, totalling about 150 in issues 6 to 18. Many of these were people Totsuji may have met during his studies in Tokyo, including musicians associated with the Tokyo Academy of Music and the imperial court. One of the people named, Nose Sakae, was a graduate of the American Pacific University. Appointed head of Nagano Prefectural Normal School in July 1882, he pioneered the training of music teachers outside Tokyo when he established a training course in that prefecture in January 1886.34

In addition, forty-two individuals and organizations who donated money are named: besides Yamaha Torakusu, the largest contributor, these include the Satsuma Biwa Association35–an indication that it was not just those involved in Western music who appreciated the magazine. Support also took the form of advertising: the majority of advertisers were based in Tokyo, but a significant number were from other parts of the country.36 Finally, eleven magazines and twenty-four newspapers from around the country published favourable reviews, having been sent a copy of the second issue and asked for a response.37 Praise for the magazine typically stressed its rich content and its potential appeal to educators, musicians, music lovers, and even women and children. One enthusiastic supporter even likened Shikama Totsuji to Christopher Columbus.38

It seems fair to conclude that even though Ongaku zasshi did not make enough money to ensure its continued publication, it was welcomed by contemporaries as a source of information and a forum for discussion. It must have been particularly valuable for music teachers, who were working hard within the localities in which they found themselves to disseminate what they had so recently learnt. The magazine informed (and, possibly, inspired) its readers, not just regarding new music, but also the new musical practices such as music education in schools and public concerts (reports on musical activities included concert programmes). Ongaku zasshi would have reminded readers far from the capital with its substantial and growing musical public that they were part of a larger community.

Ongaku zasshi was Shikama Totsuji’s most important and lasting contribution to musical culture in modern Japan, but not his only one. His zeal for music reform drove him to become engaged in a wide range of musical activities, all of which he, of course, advertised and reported on in Ongaku zasshi.

Shikama Totsuji’s Other Publications

In addition to Ongaku zasshi, Shikama Totsuji also published several other works.39 By 1888 he had authored or co-authored Kaichū orugan danhō (A pocket guide to playing the organ) and Gakki shiyōhō (How to play musical instruments), as well as two collections of songs: Katei shōka (Songs for use in the home, 4 vols, 1887–?) and Senkyoku shōka shū (A collection of selected songs, 2 vols, 1888–89). More collections of songs and tutors for self-study followed during the years when he was publishing Ongaku zassshi; namely, Shingaku dokushū no tomo (A companion to teaching yourself Qing music, 1891); Tefūkin dokushū no tomo (A companion to teaching yourself the accordion, 3 vols, 1892); Satsumabiwa uta (Collection of songs for satsumabiwa, 2 vols, 1892), and Kanzoku gakki dokushū no tomo (A companion to teaching yourself wind instruments, 1895). Another collection of satsumabiwa song texts as well as of ‘miscellaneous’ compositions was published with his wife Kotatsu named as the editor: Kokin zakkyoku shū (Collection of ancient and modern music, 2 vols, 1894), and Satsumabiwa uta: Yabu uguisu (Nightingale in the thicket: satsumabiwa songs, composed by Yoshimizu Tsunekazu, 1894).

Like Ongaku zasshi, Shikama’s other publications reflect his ambition to spread knowledge of suitable music for performance, whether Western, Chinese, or Japanese. Besides, Shikama may well have been motivated by commercial interests at a time when many instrumental tutors for self-study were being published (see the following chapter). Shikama’s (and Kotatsu’s) interest in the satsumabiwa is remarkable, given that they were from Sendai and the instrument was mainly played in South-Western Japan until the Meiji period, when performers moved to Tokyo and popularized it beyond its region of origin. While Shikama published little apart from shōka after giving up Ongaku zasshi, he wrote the lyrics for the biwa ballad Ishidōmaru, based on an old Buddhist morality tale about the young man Ishidōmaru who goes in search of his father, only to find him as a Buddhist monk who does not disclose his true identity to him.40 The tale had previously inspired other genres, from noh to kabuki and jōruri (narrative shamisen music). First performed by Yoshimizu, it became known as a masterpiece of his disciple Nagata Kinshin (1885–1927). It is included in the UNESCO Collection: A Musical Anthology of the Orient.41

Shikama Kotatsu was also named as the editor of Yūgi shōka (Songs for movement games, 1892), published by Shikama’s own company, Ongaku Zasshi Sha. Advertisements for this appeared in the issues of Ongaku zasshi throughout 1892, starting in number 18 (March 1892). The blurb is the same each time and reads as follows:

It is in children’s nature to be lively (kappatsu). Lively children thoroughly enjoy movement games (yūgi) and singing (shōka). Yūgi and shōka, moreover, are most important for developing children’s intellect and to stimulate their physical education. The editor has paid thorough attention to this and has selected yūgi shōka that suit the characteristic nature of the children of our country, and that we believe will help them to gradually progress to refinement (kōshō) and nourish their natural virtue (bitoku). In particular the movements to each song, with illustrations, will make this book an ideal one for children. The first edition has been highly praised, and a second edition has now been published.42

The advertisements each include different pictures of children in Western clothes, suggesting that they were taken from Western books.43 The preface by the editor is similar in content to the blurb, while a short note on the following page, by Senka (one of Totsuji’s pen names), reiterates the book’s purpose, beginning by citing the German pedagogue Carl Kehr (1830–85), part of whose work Die Praxis der Volksschule (1877) was published in Japanese by the Ministry of Education in 1880.44 The collection itself features pictures of children in Japanese dress. The melodies of the nineteen songs are in cipher notation, with brief descriptions of the movements.

Shikama Totsuji, who was clearly influenced by Isawa Shūji, may well have adopted his views on the importance of yūgi as well as other aspects of music education. However, the limited coverage of the subject in Ongaku zasshi suggests that Totsuji had little more than a passing interest in it. The May 1894 issue carried a short report about influential Japanese in Korea who were planning to establish a private kindergarten and to order musical instruments from Japan.45 A few issues include yūgi shōka by different authors. The August 1896 issue (the first issue published by Kyōeki Shōsha) included a song entitled Zen’aku mon (The gates of good and evil) by Kakyōin Shōsen, possibly another pseudonym for Shikama Totsuji or, conceivably, his wife.46 The tune was known, according to the explanation. As the title suggests, the content was highly moral and it is hard to imagine it appealing to children.

After 1896, Shikama seems to have published little apart from shōka and the odd journal article.47

Shikama Totsuji as a Performer, Collector

and Inventor of Musical Instruments, and Band Instructor

Identifying suitable musical instruments was one of the measures for reforming music that Shikama mentioned in his article on the subject, and articles on a wide range of musical instruments regularly appeared in Ongaku zasshi. In July 1892 the magazine even carried a short report on Turkish and Middle Eastern musical instruments, based on information from Yamada Torajirō (Sōyū, 1866–1957), a businessman who first travelled to Turkey in 1892 and made a major contribution to relations between the two countries.48 Shikama’s published tutors offered practical help for anyone wishing to learn an instrument without a teacher. He played himself, although how consistently or skilfully is anybody’s guess, as our only clues are concert programmes that name him as a performer. He may well have been the type of musician who can pick a tune with relative ease on any instrument they take into their hands. He reportedly played several Japanese and Ming-Qing musical instruments before he enrolled on the training course at the Tokyo Academy of Music, where he would have studied the violin and the piano or reed organ.49

He was certainly a collector of instruments. A report in Ongaku zasshi in July 1894 listed the following instruments in his collection (classification as in the report):50

From Europe:

Stringed instruments: 1 violin; 1 tenor (viola); 1 cello; 1 mandolin

Wind instruments: 1 clarinet; 1 petit flûte (piccolo flute); 1 grande flûte (transverse flute); 1 trumpet

Instruments with keys: 1 organ; 1 accordion

Percussion: 1 cymbal; 1 triangle; 1 chōritsukei (tuning fork)

From China:

Wind: 1 dōshō (bamboo flute); 9 Shin-teki (flutes played in Shingaku); 1 chanmera (or suona: double reed, oboe-like instrument, originally from Persia); 1 hitsuriki (hichiriki: double-reed flute)

Strings: 1 pipa (Chinese biwa: plucked lute); 5 gekkin (round lute with frets); 1 jahisen (or jabisen: Okinawa sanshin, the Okinawan version of the shamisen: three-stringed plucked lute); 1 yōkin (Chinese, yangqin; zither-like instrument); 1 teikin (Chinese tiquin; two-stringed, bowed instrument); 1 kokin (Chinese huqin; bowed instrument with two strings); 1 shichigenkin (Chinese guqin; seven-stringed zither)

Percussion: 1 hakuhan (?paiban; clappers) 1 banko (Chinese bangu; small, high-pitched drum); 1 dōra (Chinese tóngluó; gong)

From Japan:

Wind: 1 shō; 1 hitsuriki (hichiriki double-reed flute used in court music); 1 yokobue (transverse flute); 1 komabue (type of flute used in gagaku); 1 shinobue (transverse flute used in kabuki and folk music); 2 shakuhachi (end-blown bamboo flute); 8 hitoyogiri (a type of shakuhachi); 2 tenfuku/tenpuku (a type of flute from Kagoshima, similar to the shakuhachi); 1 mokukan (wooden flute)

Strings: 4 senkakin (Shikama’s own invention); 1 thirteen-stringed koto (plucked zither); 1 shamisen (three-stringed plucked lute); 1 yakumogoto (a type of two-stringed koto); 1 nigenkin (two-stringed koto); 1 chikukin (three-stringed koto, similar to yakumogoto, invented in 1886 by Tamura Yosaburō); 1 satsumabiwa (plucked lute of the Satsuma-type); 1 Ryūkyū sanshin (Okinawan version of the shamisen); 1 chōshisō (device for tuning a koto51); 1 Ezo-koto (or tonkori; plucked instrument of the Ainu)

The lack of Japanese percussion instruments on the list seems surprising. On the other hand, it is remarkable that his collection included a tonkori, an instrument of the Ainu, which must have been unfamiliar to most Japanese, as well as two Okinawan shamisen: one each listed under Chinese and Japanese instruments, possibly reflecting the ambiguous status of the Ryūkyū kingdom before the Meiji government incorporated it into the Japanese nation. The list of European percussion instruments likewise seems incomplete, given that a previous report listed drums among the instruments for use by Shikama’s youth band.

The clarinet was introduced to Japan with the military bands, but is unlikely to have been widely played in other contexts.52 It was not taught at the Tokyo Academy of Music. Shikama had introduced the clarinet in a previous issue, praising its tone and range and describing it as ‘the soul (konpaku) of wind instruments’ and thus the equivalent of the violin, the ‘king (teiō) of string instruments’.53 He played it in concerts on at least two occasions in 1893: a concert in aid of a children’s home, organized by Amaha Hideko, who had graduated from the school for the blind;54 and at a shōka concert held at a school in his neighbourhood.55 What he played is not specified, except that he played solo. At the charity concert, he also played the hitoyogiri (three-stringed koto) in an ensemble that included the head of the Ōgishi school of yakumogoto, as well as his own invention, the senkakin, in an ensemble with clarinet, violin (played by Amaha Hideko), and several koto.

The mandolin listed among Shikama’s stringed instruments was apparently a recent acquisition: according to a short note on the last page (34) of the same issue of Ongaku zasshi, it was given to him by an unnamed Englishman. Possibly this was A. Caldwell, who is listed among the supporters of the magazine in the sixth issue and contributed a short article on music published in the following issue both in English and in Japanese translation.56 Shikama Totsuji is credited with being the first Japanese to have played the mandolin at a concert. The concert, organized by Shikama himself, took place on 26 August 1894. On 1 August the emperor had formally declared war against China, and the event was billed as a ‘Patriotic concert as courageous offering to the state’ (Giyū hōkō hōkoku ongakukai).57 Originally planned for 19 August, it had to be postponed at the last minute because of a death in the imperial family.58 The declaration of war was quoted in full in the September issue of Ongaku zasshi, followed by Shikama’s statement of the rationale for the concert. At a time when everybody had to contribute to the war effort according to their abilities, it fell to musicians to compose and perform music that would encourage the patriotic spirit. The proceeds of the concerts were to go directly to the army.59 True to Shikama’s broad approach to music, the programme included a mixture of genres: bands playing gunka and marches, different styles of koto music, reciting, storytelling (kōdan), and nagauta. Apart from the mandolin, Shikama also played the hitoyogiri in the concert, as previously, together with the head of the Ōgishi school.

The mandolin performance, in a three-part ensemble, was described as Senka gaku, Senka being one of several pen names used by Shikama: here, his name (assuming it was his) was given as Koto no ie Shōsen.60 The other players were Amaha Hideko (violin) and Totsuji’s daughter Fujiko (harp/hāpu), and they played Yachiyo jishi (Lion of eight thousand years). It is not clear what kind of instrument the ‘harp’ was. If it was a Western harp, it may well have been another first, but no harp is listed among the instruments in Totsuji’s collection.61

There is no evidence of Totsuji pursuing the mandolin further, and the introduction of the mandolin in Japan in a more lasting way is attributed to Hiruma Genpachi (1867–1936), who graduated from the Tokyo Academy of Music and then studied in Europe, bringing a mandolin home with him in 1901. Totsuji’s youngest daughter Kiyoko, however, later played the mandolin professionally.

Shikama’s own invention, the senkakin, was born from ‘my sincere and deep desire to devote myself to reforming the music of our country’.62 A brief note in the November 1892 issue claimed that the senkakin could be used in place of the koto, shamisen, or biwa. The fingerboard (here he seems to be referring to the tonal range) was the same as that of the cello, the viola, and the violin, making it possible to perform music with Western-style harmonies. The note is followed by another, restating the purpose of Ongaku zasshi to promote music reform,63 while an advertisement by the Tanaka Reed Organ Factory included the senkakin along with organs and satsumabiwa.64 The merits of the senkakin were described in detail in the next issue of Ongaku zasshi in a three-page article that included an illustration.65 After outlining his ideas on music reform (see Chapter 6), Shikama introduced his new instrument, this time spelt with a different character for the ‘Sen’, the same character as in his home town Sendai.66 The advantage of the senkakin, he asserted, was that its four strings could be tuned in different ways, either G-D-A-E like those of a violin, or A-D-A-D starting an octave below the violin’s A string. A capo (kase), that is, a device clamped across the strings of the senkakin’s long, fretted neck, enabled the player to raise the tuning with ease. This, asserted Shikama, made it easy to play Western or Japanese music or Ming-Qing music. The tonal range of the senkakin included lower notes than most Japanese instruments, enabling players to perform pieces with several different parts, including a bass part.

A second article two issues later, by an author who called himself ‘Tetteki Bōhyō’ (possibly Shikama), again stressed the importance of suitable musical instruments for music reform: the right instrument was as important for a musician as a weapon was to a soldier.67 After years of research, Shikama had finally developed the senkakin, based on the koto and the shamisen, and enhanced it by adapting characteristics of the violin and the biwa. The result was an instrument that sounded exceedingly elegant (yūbi) and had a wider range of lower tones than Japanese instruments, making it well-suited for playing harmonies and thus appropriate for the trend towards more complex music. It was not realistic to enforce music reform too quickly, continued the author, as this might lead to an increase in objectionable musical practices (an argument already presented in the first article). The senkakin, it was hoped, would provide the essential tool for promoting musical reform.

Subsequent issues of Ongaku zasshi included further mentions of the senkakin as well as adverts—for a time. Presumably, Tanaka soon gave up production, as the instrument then disappeared from their adverts. From the January 1893 issue (no. 28) the senkakin was advertised as being available from Shikama’s own company, Ongaku Zasshi Sha. The advertisement praised the instrument as having ‘a beautiful form, a superior and clear sound, is easy to play and to carry around. Moreover, the fact that it is suitable for playing Japanese, Chinese, and Western music with a single instrument.’ The instrument was claimed to have elicited high praise, and music enthusiasts (ongaku no shishi) were urged to try it for themselves. Nevertheless, the senkakin failed to gain popularity. Without a published tutor and appropriate sheet music, or a skilled performer to champion the instrument, it did not have much of a chance. The November and December issues of Ongaku zasshi included notation for a senkakin version of the popular koto piece Yachio jishi in cipher notation, accompanied by a tablature.68 Shikama himself played the instrument on at least a couple of occasions. One was at the charity concert on 23 April 1893 already mentioned.69 That, however, seems to have been the extent of his efforts to promote the senkakin, which soon faded into oblivion, as did many musical instruments invented in the nineteenth century, both in Japan and in Europe.

Shikama’s concert performances reveal him as an advocate of playing Japanese music on Western instruments, often in ensembles with players of koto or shamisen. This practice also characterized the youth band founded by Shikama in December 1894, the Tokyo Shōnen Ongakutai. One of the first of its kind, the band’s stated aim was ’to avoid vulgar music and practise refined, proper musical compositions in order to promote good public morals and gradually incline (the public) towards the true music of civilization’.70 According to the regulations published in Ongaku zasshi, the band was for boys and girls from the age of ten to the age they entered university. Rehearsals were on three afternoons a week. Participation was to be free, as were the instruments provided, but a maintenance fee had to be paid.71 The following instruments were listed in the regulations: accordion; senkakin; flageolet; small pipe; large drum; small drum; triangle; cymbals; tambourine; flute; clarinet; saxophone; contrabass; bass; and unspecified stringed instruments.72

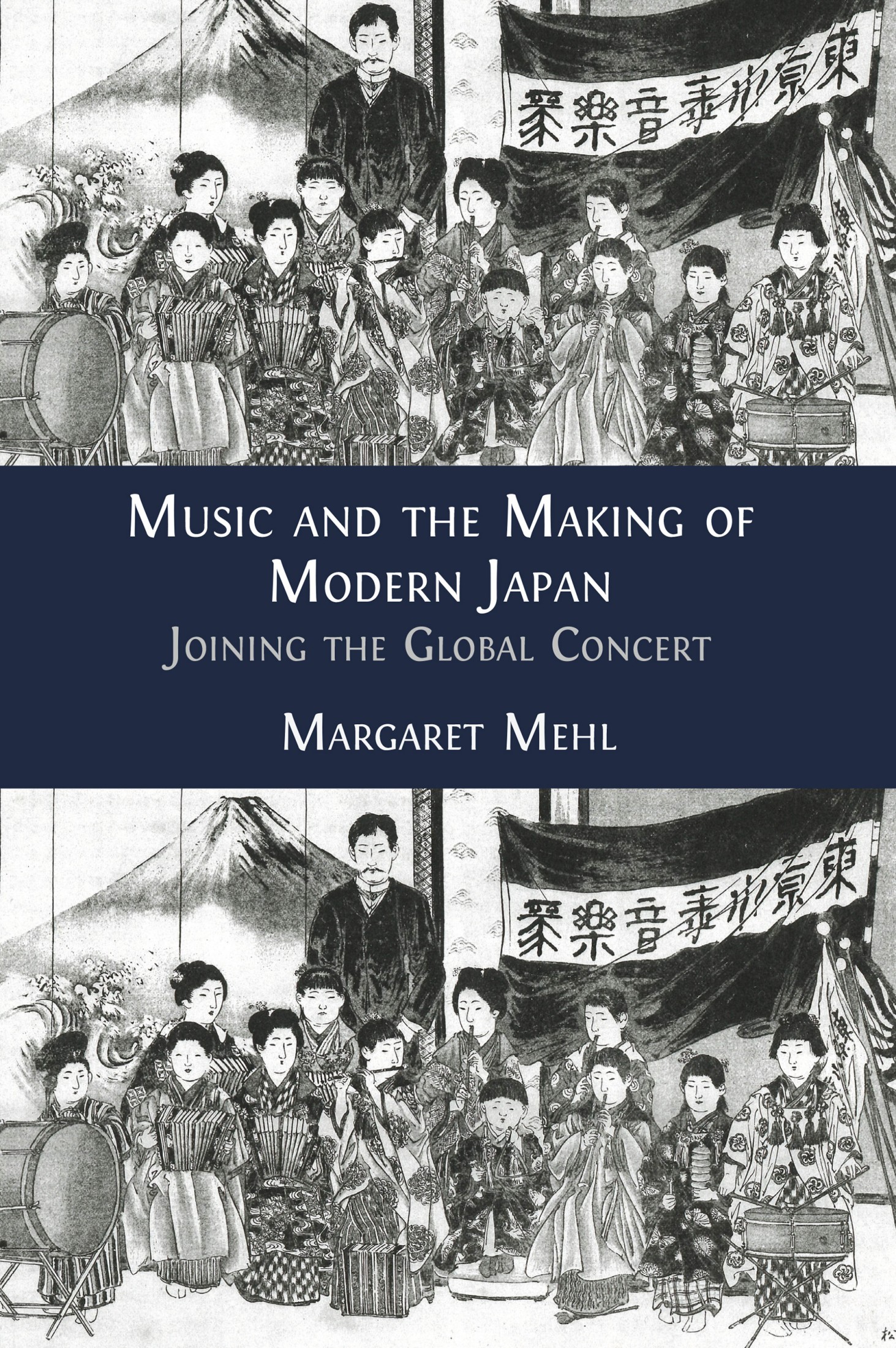

Two months later Shikama could report that the band had featured in the magazine Fūzoku gahō (Illustrated magazine of customs): the short article, reprinted in Ongaku zasshi, described Shikama as a promoter of reformed music (kairyō ongaku) with the aim of supporting education in the home (katei kyōiku) and furthering the reform of society.73 According to the article, the band boasted sixteen kinds of instruments from East and West and performed proper music (seikyoku), whether Eastern or Western, old or new, elevated or popular. It played upon invitation at gentlemen’s functions. The illustration accompanying the report was drawn from a photograph and showed a group of twelve boys and girls in formal Japanese dress playing a large and a small drum, accordions, side- and end-blown flutes, a triangle, and handheld pagoda bells. Shikama himself, in a Western suit, is standing behind the group, flanked by a background picture of Mount Fuji with a breaking wave at its base, and a large banner bearing the name Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai. At the right-hand edge of the picture a Japanese flag and another flag with what may be the name of the band are just discernible. While the band is clearly the main subject of the picture, the flag and Mount Fuji suggest that they are representing the nation and thus Shikama’s reform ambitions, which went well beyond training a group of children.

Subsequent reports in Ongaku zasshi provide a little more detail about the repertoire, which reportedly included the national anthems of various countries, famous waltzes and polkas, as well as pieces from the koto repertoire, shōka, and military songs (gunka).74

Privately established bands were becoming increasingly popular at the time.75 A report in Ongaku zasshi in September 1895 briefly introduced the ones in Tokyo prefecture, eleven besides Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai, one of them another youth band.76 In December 1895, a year after founding his own band, Shikama reported that he was finding imitators in other parts of the country as well as Tokyo and offered to assist with instruments and advice.77 Indeed, he involved himself in the establishment of a youth band as well as one for adults in Sendai even before he moved there in summer 1896. The fate of the band in Tokyo is not known. Shikama may have travelled to Tokyo while he was based in Sendai, just as he became active in Sendai while still living in Tokyo; however, it seems unlikely that he would have done so in the long term.

Shikama Totsuji’s pedagogical activities included his daughters. The eldest daughter Fujiko (1884–1901) was described by her (hardly unbiased) father in Ongaku zasshi as a highly talented musician.78 She reportedly studied the violin with Rudolf Dittrich from age nine and was said to be even better than Andō Kō.79 The three who survived into adulthood earned their living as musicians. The eldest, Ranko (1887–1968) reportedly taught music from the age of fifteen, after graduating from Miyagi Prefectural High School for Girls (Miyagi Kenritsu Kōtō Joshi Gakkō) in 1902. When the family moved back to Tokyo in 1906, she taught in the music department of the Matsuzakaya department store in Ueno alongside her father, from whom she eventually took over. She worked there for twenty-seven years. From 1908 to 1909 she studied piano at the Tokyo Academy of Music.80 In 1909 she received a certain notoriety when the press reported an alleged liaison with an infamous conman. She and her sister Kunie (c. 1891–1969) were described as regular performers on the piano and the violin at Japan’s first beer hall (opened in 1899). 81 The conman-scandal pursued Ranko for years: newspaper articles in 1911, 1912, and 1918 referred to it, and so we learn that in 1911 she was still performing at the beer hall, and that in 1918 the sisters were known for their talent and beauty.82 Not much else is known about them. They remained single and presumably made a living by teaching and performing, conceivably benefiting from the post-1945 rise in demand for music lessons.83 Totsuji’s youngest daughter Kiyo (1903–65) played the mandolin professionally, making several recordings during the 1920s and 1930s, some of them together with her sisters. She married Takenaka Kaseiji, a recording engineer.84 After 1945 Kiyo reportedly ran her own mandolin studio, and, for a time, played in the Orchestra Symphonica Takei, a mandolin orchestra founded by Takei Morishige (1890–1949) in 1915.85

The daughters’ careers are remarkable, particularly when compared to those of the Kōda sisters, barely a generation earlier: likewise from a samurai family (although from the capital and in the service of the shogun), they only performed in public in concerts under the auspices of the Tokyo Academy of Music and did not make recordings. They would almost certainly have considered playing for money in a beer hall as beyond the pale.86 Even so, neither could they escape scandal. Kōda Nobu (1870–1946) had to resign from her teaching position at the Academy in 1909 due to allegations of an affair with August Junker, who taught there at the time. Although teaching music presented a viable career for women, the long-standing association of musical performance with the pleasure quarters made performing in public suspect.

Even for men, at least those from samurai families, music as a career was suspect. Shikama Totsuji, being the firstborn, certainly failed to conform to social expectations. Instead of remaining in Sendai and preparing to take over as the head of the family, he followed his younger brother to Tokyo, remaining there for several years. He made his living from music; not as part of a respectable teaching career in public schools like his younger brother, but as a freelancer and entrepreneur. He spent a considerable part of the family assets on his ventures, most of which were short-lived. He made his daughters perform in the streets of Sendai as members of his youth bands, hardly an appropriate occupation for samurai daughters.87 Finally, he abandoned his family for what appears to have been a restless life.

Yet Shikama Totsuji’s contributions to the growth and dissemination of music-related activities were important, occurring as they did during the period when Western music was only beginning to reach the wider population outside the capital and the commercialization of music was still in its infancy. Its growing importance and the rising demand for music-related products were reflected in the increasing proportion of adverts in Ongaku zasshi. Above all, both Shikama’s own activities, and those of the local actors whose achievements were reported in the pages of Ongaku zasshi, demonstrate the importance of individual initiative for putting into practice the ideas for music reform advocated by politicians and leading intellectuals, as well as bringing about developments that were not envisaged or endorsed by them. This is further illustrated by the activities of a younger generation of would-be reformers, as well as musical entrepreneurs, who promoted their own version of blending Western and Japanese music.

1 Totsuji Shikama, ‘Yamato miyage no jo’, Ongaku zasshi 46 (1894).

2 ‘Jinbutsu dōsei’, Ongakukai, no. 160 (1915). Totsudō was Shikama’s Sinitic literary name. Two years later he was living in Tsuchiura (Ibaraki prefecture): Ongakukai, no. 189 (1917): 50.

3 Part of the content in this chapter was previously published as Margaret Mehl, ‘Between the Global, the National and the Local in Japan: Two Musical Pioneers from Sendai’, Itinerario 41, no. 2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0165115317000389

4 Biographical details on Shikama Totsuji in Keiji Masui, ‘Ongaku zasshi (Omukaku) kaidai’, in Ongaku zasshi (hōkan) (Tokyo: Shuppan Kagaku Sōgō Kenkyūsho, 1984). Besides information culled from Ongaku zasshi, Masui relied on documents and reports from family members, namely Shikama Tsuneo, the son of Totsuji’s youngest brother Kōsuke, and the widow of Totsuji’s fourth and only surviving son by a concubine.

5 He is generally described as the first music teacher of note in Sendai: see biographical details in Shin’ya Watanabe, ‘Sendai sho no shōka kyōshi Shikama Jinji’, Sendai bunka, no. 11 (2009); Miyagiken Kyōiku Iinkai, ed., Miyagiken kyōiku hyakunenshi Vol 4 (Sendai: Gyōsei, 1977), 429; Sakae Ōmura, Yōkendō kara no shuppatsu: kyōiku hyakunenshi yowa, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Gyōsei, 1986), 175.

6 Shikama Nobunao’s third son (Kōji?) died as a student, according to Masui; the inscription on Shikama Totsuji’s family grave records the year of his death as 1891: his age is not recorded.

7 Osamu Ōtō, Sendai-han no gakumon to kyōiku: Edo jidai ni okeru Sendai no gakuto-ka, Kokuhō Osaki Hachimangū Sendai Edogaku Sōsho 13 (Sendai: Ōsaki Hachimangū (Sendai Edogaku Jikkō Iinkai), 2009), 38–41.

8 Sumire Yamashita, ‘Tōhō seikyō no ongakaku to shizoku’, in Kindai ikōki ni okeru chiiki keisei to ongaku: tsukurareta dentō to ibunka sesshoku, ed. Kanako Kitahara and Kenji Namikawa (Kyoto: Mineruba Shobō, 2020), 190.

9 The Yōkendō was established as the Gakumonjo in 1736 and renamed in 1772. The following summary is based on Kazusuke Uno, Meiji shōnen no Miyagi kyōiku (Sendai: Hōbundō, 1973). For the Tokugawa period, see also Ōtō, Sendai-han no gakumon.

10 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 7–8. The chronology is uncertain.

11 According to the inscription on the family grave at Kōmyōji in Sendai, she died in 1940 at the age of seventy-eight.

12 The second daughter, Ranko (c. 1886–1968), the third Kunie (c. 1891–1969), and the sixth, Kiyoko (c. 1900–65). The eldest son Kaoru went to the United States to study and was not heard of again.

13 See the quote at the beginning of this chapter.

14 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 8. I have not been able to verify this.

15 Masami Yamazumi, Shōka kyōiku seiritsu katei no kenkyū (Tokyo: Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppankai, 1967), 158–70; Mamiko Sakamoto, Meiji chūtō ongaku kyōin no kenkyū: ‘Inaka kyōshi’ to sono jidai (Tokyo: Kazama Shobō, 2006), 119–22. There were forty-seven prefectures at the time (the numbers fluctuated before 1888). Sakamoto’s work is the most detailed about the training of secondary level music teachers in the Meiji period (although only from lower secondary level onwards).

16 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 8. Totsuji (unlike Jinji) is not on the list of students sent by their prefectures in 1885 compiled by Sakamoto: Sakamoto, Meiji chūtō ongaku kyōin, 120. Possibly he studied at his family’s expense, as did his contemporary Tsunekawa Ryōnosuke, who likewise is missing from the list. See Satsuki Inoue, ‘Tsunekawa Ryōnosuke to Meijiki Nihon no Ongaku’, Aichi Kenritsu Geijutsu Daigaku kiyō, no. 41 (2011): 24, https://doi.org/10.34476/00000014

17 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 9.

18 The university’s later yearbooks say 1886, but 1885 is correct.

19 Tōkyō Geijutsu Daigaku Hyakunenshi Hensan Iinkai, Tōkyō Ongaku Gakkō hen 2, 1560, 1588.

20 A short report in Ongaku zasshi 58 (May 1895) stated that he was returning because his father was ill. The next volume was not published until September, by which time Kyōiku Shōsha had taken over.

21 ‘Tokyo no onna (34): Biya hōru no gakushu, Inazuna kozō jiken no Shikama Ranko’, Asahi shinbun, 22 September 1909, Morning.

22 See quote at the beginning of this chapter.

23 True to the customs of the time, the son was adopted into the Shikama family and registered with Tatsu as his mother, while the daughter was registered as an illegitimate daughter: information from copy of the koseki (family register) entry for Shikama Totsuji’s household, dated 1 April 1929 (Shōwa 14). I thank Totsuji’s grandson Shikama Tatsuo for this information; according to him, Totsuji also spent time in Nagano Prefecture.

24 Totsuji Shikama, ‘Hakkan no shushi’, Ongaku zasshi 1 (1890). The magazine is probably La Revue et Gazette Musicale; published under different names from 1827 onwards, it ceased publication in 1880.

25 For a list of articles on Ming-Qing music published in Ongaku zasshi from 1891–97, see Yasuko Tsukahara, Jūkyū seiki no Nihon ni okeru Seiyō ongaku no juyō (Tokyo: Taka Shuppan, 1993), 598–609.

26 Setsuko Mori, ‘A Historical Survey of Music Periodicals in Japan: 1881–1920’, Fontis Artis Musicae 36, no. 1 (1989).

27 Ongaku; shinkyoku; kisho; zatsuroku; sankō; zassan; mondō; shakoku; and kōkoku.

28 Spelt phonetically, in hiragana.

29 Masui, ‘Kaidai’.

30 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 20, 26.

31 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 10. Suzuki Masakichi was not the first Japanese to make violins, but he was the most successful when it came to large-scale production and distribution: see Mehl, Not by Love Alone, 72–83.

32 For detailed description and analysis of the supporters, sponsors, and advertisers named in Ongaku zasshi as well as feedback from readers and reviews in contemporary publications, see Akio Kusaka, ‘Ongaku zasshi ni miru Shikama Totsuji no keimō katsudō to sono hirogari: juyō no shiten kara (1)’, Aomori Ake no hoshi tanki daigaku kiyō, no. 24 (1998), http://www.aomori-akenohoshi.ac.jp/images/stories/pdf/college/kiyo/kiyo26.pdf; Akio Kusaka, ‘Ongaku zasshi ni miru Shikama Totsuji no keimō katsudō to sono hirogari: juyō no shiten kara (2)’, Aomori Ake no hoshi tanki daigaku kiyō, no. 26 (2000), http://www.aomori-akenohoshi.ac.jp/images/stories/pdf/college/kiyo/kiyo26.pdf The following numbers are based on the lists compiled by Kusaka. His lists of supporters overlap, so there are a few duplications.

33 Masui, based on information in Ongaku zasshi 36, estimates the total at 600–800 printed copies: Masui, ‘Kaidai,’ 13.

34 Yoshihiro Kurata, Geinō no bunmei kaika: Meiji kokka to geinō kindaika (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1999), 208.

35 Kusaka, ‘Ongaku zasshi (1)’, 65.

36 Ibid., 68–73. Kusaka lists a total of 139 advertisers, including Shikama Totsuji himself, forty-six of which were based outside Tokyo.

37 Kusaka, ‘Ongaku zasshi (2)’, 45.

38 Summarized in Kusaka, ‘Ongaku zasshi (2)’, 47.

39 The publications listed here are in the catalogue of the National Diet Library, except for Kotatsu’s Yūgi shōka, which was advertised repeatedly in Ongaku zasshi and published by Ongaku Zasshi Sha in 1892; Tokyo University of the Arts has a copy. For Katei shōka, the NDL lists only volumes 1–3 (1887–89), while the catalogue at Tokyo University of the Arts includes a fourth volume, but without giving a concluding date.

40 Ishidōmaru was published in 1905, in Seishin kyōiku teikoku biwa renmashū, ed. by Yoshimizu Tsunekazu. See Tadashi Shimazu, Meiji Satsumabiwa uta (Tokyo: Perikansha, 2001), 56, 208–09.

41 Record 6, side 2.: Noh play, Biwa, and Chanting (1962). See https://discog.piezoelektric.org/musicalanthologyoftheorient.html

42 Ongaku zasshi 18 (March 1892), facing p. 1.

43 Further advertisements appeared in Ongaku zasshi 22 (July 1892), front inside cover; 27 (December 1892), back cover.

44 Carl Kehr, Die Praxis der Volksschule (8th ed.) (Gotha: E. F. Thienemann, 1877 (1868)). Japanese C. Kehr, Heimin gakkō ron ryaku (Tokyo: Monbushō, 1880).

45 ‘Kaigai no Nihon yōchien’, Ongaku zasshi 44 (1894) p. 15.

46 ‘Yūgi shōka Zen’aku mon’, Ongaku zasshi 59 (1896), p. 23. Kakyōin was the address of the Shikama residence in Sendai.

47 See Chapter 9.

48 ‘Konstanchinopuru no gakki’, Ongaku Zasshi 22 (1892), pp. 14–15.

49 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 8, 9. Masui states that Shikama Totsuji played at least the koto, biwa, and gekkin.

50 Totsuji Shikama, ‘Kakushu no gakki’, Ongaku zasshi, no. 46 (1894).

51 See Kosen (Shikama Totsuji), ‘Koto no chōshi sōgatten’, Ongaku zasshi 44 (1894). I thank Prof. Tsukahara Yasuko for drawing my attention to this article.

52 The clarinet is today one of the instruments played by chindonya, colourfully dressed street performers who play for advertisers, but this probably represents a later development.

53 Senka [Shikama Totsuji], ‘Kurarinetto’, Ongaku zasshi 30 (1893).

54 ‘Yūikuin jizen ongaku kai’, Ongaku zasshi 31 (1893).

55 ‘Seito shōkakai’, Ongaku zasshi 32 (1893). His eldest daughter Fujiko played the koto in both these concerts.

56 A. Caldwell, ‘Music’, Ongaku zasshi 7 (1891).

57 The expression giyū hōkoku comes from the Imperial Rescript on Education issued in 1891.

58 Announcements in Yomiuri shinbun, 16, 19, and 25. See also Ongaku zasshi 47 (1894): 26.

59 Totsuji Shikama, ‘Giyū hōkō hökoku ongakukai kaikai no taii’, Ongaku zasshi 47 (1894). According to the report of the concert in the same issue, 100 yen were delivered to the army the day following the concert.

60 Masui assumes that this is Shikama Totsuji; the hitoyogiri performer appears under the same name in the programme, while in the concert in 1893 Shikama performed as ‘Shikama Senka’.

61 Masui, ‘Kaidai’, 31.

62 Wagakuni ongaku no kyōsei ni tsukusan to suru no seikishin shukushi: Totsuji Shikama, ‘Senkakin ni tsuite’, Ongaku zasshi, no. 27 (December 1892), 11.

63 Ongaku zasshi 26 (1892), 32.

64 Tanaka Fūgin Seizōsho, 35.

65 Shikama, ‘Senkakin ni tsuite’.

66 The meaning of both the characters used is the same.

67 Bōhyō Tetteki, ‘Senkakin’, Ongaku zasshi, no. 29 (February 1893).

68 Yachio jishi ‘Senkakin gakufu’, Ongaku zasshi 37 (1893): 7–8; 38 (1893): 10; despite the announcement ‘to be continued’ in no. 38, it does not seem to have been.

69 Item no. 12: ‘Yōikuin jizen ongakukai’, Ongaku zasshi 31 (1893).

70 yahi naru ongaku o sake yūbi naru seikyoku o renshū shite fūkyō o hiho shi zenji bunmei no shin ongaku ni utsurashimuru: Regulations for the band in ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai’, Ongaku zasshi 50 (1895).

71 An advertisement for members in the following issue stated that a monthly fee of fifty sen was payable: Ongaku zasshi 51 (1895): 16.

72 ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai’, 32. The terminology appears to be derived from French.

73 ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Gakutai sōga ni fu shite’, Ongaku zasshi 52 (1895). See ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai’, Fūzoku gahō 97 (1895).

74 ‘Fuka genzai no ongakutai’, Ongaku zasshi 53 (1895); ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai’, Ongaku zasshi 55 (1895).

75 Yasuko Tsukahara, ‘Gungakutai to senzen no taishū ongaku’, in Burasubando no shakaishi: gungakutai kara utaban e, ed. Kan’ichi Abe et al. (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2001), 110.

76 ‘Fuka genzai no ongakutai’.

77 ‘Tōkyō Shōnen Ongakutai’.

78 ‘Shikama Fujiko no Kōei’, Ongaku zasshi 21 (June 1892): 21.

79 ‘Biya hōru no gakushu’. Dittrich was (1861–1919) was employed as artistic director at the Tokyo Academy of Music from 1888 to 1894. Andō Kō (1878–1963), like her elder sister Kōda Nobu (see Chapter 3), played a pioneering role in the introduction of Western music. Having studied with Dittrich from an early age, she graduated from the preparatory course at the Tokyo Academy of Music, graduating in 1894. After completing her studies at the Academy, she studied in Berlin for three years, before being appointed professor at the Academy in 1903.

80 Yoshihiro Kurata and Shuku Ki Rin, eds., Shōwa zenki ongakuka sōran: ‘Gendai ongakuka taikan’ gekan (Tokyo: Yumani Shobō, 2008), 251. Ishida Tsunetarō, ed., Meiji fujin roku, 2 vols. (Tokyo: Tōkyō Insatsu Kabushiki Kaisha, Fujo Tsūshinsha, Hakuunsha, 1908). The year of her birth is given as 1887 by Ishida, which appears to be correct. The inscription on the family grave states that she died in 1968 at eighty-two.

81 ‘Biya hōru no gakushu’.

82 ‘Bā to hōru (4): Onna kyūji no Shinbashi hōru’, Asahi shinbun, 16 September 1911, Morning; ‘Jogakusei o mayowasu’, Asahi shinbun, 22 March 1912; ‘Norowaretaru koi no akushu’, Yomiuri shinbun, 22 March 1912, Morning; ‘Inazuma Kozō torawaru Shikama shimai no jōfu nite’, Asahi shinbun, 26 December 1918, Morning.

83 Margaret Mehl, Not by Love Alone: The Violin in Japan, 1850–2010 (Copenhagen: The Sound Book Press, 2014), 231–47.

84 Information from music yearbooks (1922–41). The one for 1929 lists Kiyo as a Mandolin player: Gakuhōsha, ed., Ongaku nenkan: Gakudan meishiroku Shōwa 4 nen han (Tokyo: Takenaka Shoten, 1928), 110. In 1933 she was listed as Shikama Kiyoko but with the addition of Takenaka, her family name: Hitoshi Matsushita, ed., Kindai Nihon Ongaku Nenkan (Shōwa 8) (Tokyo: Ōzora Sha, 1997), 41. Subsequent yearbooks in the 1930s list Kiyo and Takenaka Kaseiji at the same address in Kōjimachi. There are several recordings in the National Diet Library and in the sound archives of Osaka College of Music.

85 Renamed Orchestra Symphonica Tokyo in 1987. I have not been able to verify the information about Shikama Kiyo’s post-war career.

86 About the Kōda sisters, see Margaret Mehl, ‘A Man’s Job? The Kōda Sisters, Violin Playing and Gender Stereotypes in the Introduction of Western Music in Japan’, Women’s History Review 21, no. 1 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2012.645675

87 According to his grandson Shikama Tatsuo, their cousin, the eldest daughter of Totsuji’s brother, was unhappy about this, as she was taunted about it at school: e-mail correspondence 19 and 23 July 2019.