4. The Family Square

©2024 Barbara Fisher, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0377.04

At the end of the year 1883, Alice and Trix disembarked from The S.S. Ancona at Bombay. They had made the arduous, three-week journey through the straits of Gibraltar to Marseilles, to Port Said, through the Suez Canal to the Red Sea to Aden, finally arriving at their destination. After the long sea voyage, Trix was anticipating the soothing solidity of land. Instead, she was met by the overwhelming clamour and squalor of the port of Bombay. Faces darker than she had ever seen before appeared all around her. Almost naked men, children covered with flies, stray dogs, goats, and cows crowded everywhere. Acrid fumes from burning cow dung burned her eyes, while the sweet noxious odours of spices filled her nostrils. The incomprehensible shouting and chatter that accompanied the violent arm-waving of the men confused and alarmed her, while the brilliant colours of the women’s saris—cherry red, emerald green, orange, yellow, blue, and mauve—dazzled her. Although she had been told about the noise and filth of India, nothing had prepared her for the teeming chaos of the port of Bombay.

Trix and Alice were met by bearers—dark men in strange, ragged clothes, who led them through the riotous crowd along the palm-fringed, curving coast to their hotel. In the distance, Trix could see clock turrets, church steeples, and the oddly shaped domes and spires of strange tall buildings.

But mother and daughter did not stay to explore the city. After resting and recovering from the long voyage, they set out on the onerous four-day train journey north to Lahore. Riding for days through the dun-coloured plains, unaccustomed to the oppressive heat, the incomprehensible noise, and the unfamiliar smells, Trix just wished to arrive at Lahore in time for Christmas. The Lahore train station, which Trix looked forward to as an end of the ordeal, was a vast echoing stone hall filled with the clamour of vendors, the shouts of policemen, and the shuffling of women gathering up their children and their baskets. Making their way through the dusty crowds, Trix and Alice secured a carriage to drive them past the old walled city to the newly built British expatriate area, called ‘Donald Town’ after Donald McLeod, the lieutenant governor of the Punjab from 1865–70. As she rode down the centre of town on a broad boulevard known as the Mall, Trix could see on either side grand imposing buildings—brick and stone, multi-domed Anglo-Saracen extravaganzas as well as imposing and fanciful colonial and neo-classical buildings. In the distance, extensive leafy gardens and pleasure parks were barely visible. Out of sight was the British military command where infantry and artillery battalions were always in residence.

As Trix rode along the Mozang Road, she could see the Kipling house from afar. It stood alone in a wide open plain. The large, low house was surrounded on all four sides by a wide veranda of graceful arcades. No trees or shrubs surrounded the house, as Lockwood believed they spread disease. Thus, the dry and dusty house was named Bikanir House, after the great golden Indian desert of that name. Inside, Trix found many large square rooms with high, white-washed walls, wooden floors, and furnishings in the current Anglo-Oriental style—heavy English furniture, Persian carpets, and old master engravings. Family photographs decorated the walls, vases of brilliant flowers and feathers stood on the many small tables. Heavy draperies covered the windows to protect the interior from the heat and dust of the day. The windows faced the pointed arches of the arcade, from which there were unobstructed views in every direction. Most wonderful of all for Trix was her own bedroom, her childhood wish at last fulfilled. Lockwood had decorated the room just for her with lacquered furniture patterned in graffito, a high dado of Indian cotton, and a painted fireplace where her initials were so twined among Persian flowers and arabesques that they seemed part of the design. Trix had never had a room decorated just for her before, and she was thrilled to have this beautiful space, all for herself.

Once settled in her own room, Trix tried to make herself feel at home in the exotic land she had only fantasized about. At first, she dared only to go from Bikanir House down to the Mall, where the Lahore Museum was housed in an extravagant, red-brick, multi-level, multi-domed building. Here Lockwood served as director of the museum and keeper of its wonders. Close to the museum were the offices the of The Civil and Military Gazette, where Rudyard had been toiling as sub-editor for more than a year. Trix soon felt comfortable in the imposing, irregular pile which housed the museum and in the two low, wooden sheds, which held the modest offices of the Gazette.

Like most young people, Trix accepted the world she had been deposited in, engrossed as she was in her new impressions and old worries. Soon, guided by her mother, Trix learned how to move around in this world. She was taught to model her behaviour on the customs, rules, and beliefs of the community of which she was a part. She learned that she was a member of a small ruling elite—the British Raj. To understand the Raj, she was required to learn something of the larger history of the country in which she lived.

She was taught that the British had been in India as traders, mostly under the direction of the East India Company since the sixteenth century. When she arrived in the 1880s, she was taught and she could feel that the British were secure in their position as conquerors and rulers. They were confident in their belief that they were on a great civilizing mission, bringing British laws and culture to a primitive society. But she also could sense anxiety. Just beneath these national certainties was the terrifying memory of the Mutiny of 1857, which, while not fresh in mind, was uneasily and frequently recalled. The memory of this violent revolt was subtly but surely conveyed to Trix, although the rebellion itself had been firmly and finally suppressed a decade before her birth. Stories of the rebellion included details of extreme cruelty on both sides—a cycle of brutal acts by the Indians and horrific reprisals by the British. After the rebellion was contained, the East India Company was dissolved, and the British reorganized the army, the financial system, and the entire administration in India. From 1858 onward, India was administered directly by the British government under the new British Raj. This new administration provided a tiny band of British civil servants, who ruled over the vast sub-continent and its huge population with apparent confidence and ease.

From fear, discomfort, and ignorance, the British distanced themselves from Indian culture, shielding themselves from contact with Indians, except as servants. They laid out their own closed communities with parallel streets on a regular grid. They built spacious bungalows and planted shady English gardens. In their attempt to reproduce the feel of home, they decorated with chintz fabrics, cooked with imported tinned food, and dressed in heavy British woollens and tweeds. They entertained with pomp and pageantry—dinners, balls, teas, and picnics. They practiced British sports—riding, badminton, and tennis. All of this was supported by a host of Indians servants, who cooked, cleaned, tended the garden, served at parties, and watched over children.

To the British, the Indians were useful only as servants. To understand the many complicated differences among Indians was simply too difficult and confusing for most of the British to attempt. Indians looked different—some tall, some short, some dark-skinned, some yellow-skinned, some with light skin and pale eyes. They dressed differently—some women wore bright silk saris, some pants, some were completely covered in long veils. Men wore trousers, skirts, as well as unusual wrappings and bindings of white muslin. Many appeared shirtless, bare-legged, or practically naked. Some wore large, coloured turbans, some skull caps, some were bareheaded. They spoke more than a hundred different languages, the most common being Hindi. Indians were divided into many religions—Muslims and Hindus primarily, but also Buddhists, Jews, Christians, Parsees, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, and Jains. Within these religions were many subdivisions. There was also a powerful caste system, which established and maintained strict and distinct rules and provided harsh punishments for transgressing those rules. The caste into which one was born controlled what jobs one could do, how one could dress, where one could live, and with whom one could associate. The British learned as much of this system as was necessary for them to keep their households running smoothly, recognizing, for example, that a member of the lowest caste, an ‘untouchable’, could serve as a sweeper but only as a sweeper.

Trix adapted to the ways of her family and her class, fitting herself into the society that surrounded her. When she learned, with help from her mother, how to behave properly, she was rewarded with approval and praise.

Thus, at the age of fifteen, Trix entered into the happiest period of her life. At last she was a cherished member of a warm, loving, and cultured household. Safe in the embrace of ‘The Family Square’—a pet name invented by Alice Kipling to describe the four Kiplings together as a group—Trix was content, doted on by her parents and at ease with her brother. At the home she had dreamed of for years, she felt accepted and loved. With the longed-for attention of Alice, she attempted at last to satisfy her ‘mother want’.

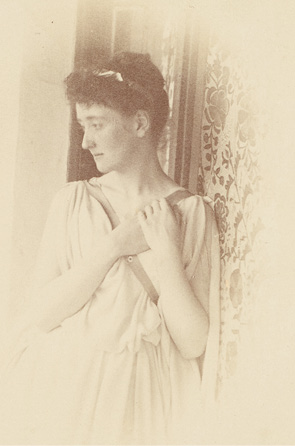

With her family, Trix followed the seasonal patterns of the British, spending the winter months at Birkanir House in Lahore and, during the hot months, travelling with her mother, first to Dalhousie and later to Simla. In the heat, Rudyard and Lockwood remained in Lahore for their work, joining the women at intervals. In Dalhousie, Trix was thrilled by the many compliments she received. Everyone said how fresh and pretty she was, how lively and pleasant. Unself-conscious about her weight and her manners when she first arrived, she responded to Alice’s reminders and remonstrances by quickly slimming down and smartening up. She wore her fair hair in a smooth chignon, with what she referred to as her fringe (bangs) curling over her brow. Keeping her unmanageable fringe, which became frizzy in the humid weather, under control drove her almost mad. She had deep-set blue eyes, a small, delicate mouth, and luminous white skin. She showed off her small waist and ample bosom in the tight bodices of her fashionable dresses. When she was in costume for amateur theatricals or dressed for the evening, she exposed her graceful neck and shoulders. She quickly became an acknowledged beauty, an expert dancer, and soon a heartbreaker.

Alice and Lockwood did what they could to please their daughter, spoiling her with presents and pets. They bought her a Persian cat and a fox terrier puppy. When she began to improve her skill on horseback, they provided her with her own pony, named Brownie. Lockwood, ‘the Pater’, had pet ravens, named Jack and Jill; Ruddy a bull terrier named Buzz. Alice did not take kindly to pets, but was fond of Trix’s cat and, as a great concession, allowed it to sit on her lap.

Living with the family at Bikanir House, Trix seemed untroubled. As her mother had wished, she seemed to have erased all the possible ill-effects of her difficult childhood. If she suffered from doubts and depression, she hid them well. Rudyard from time to time complained that he was beset by ‘blue devils’.1 He suffered from insomnia, night-time wanderings, and hallucinations. But Trix never complained of unhappiness or melancholy either to Rudyard or her parents. Her parents wanted her to be happy, and she wanted to please them by being what they wanted. She was practiced in dissembling and could without much difficulty produce the look and sound of happiness when needed. But this was a time when she was truly happy.

Used to the routine of school, Trix was surprised by the relaxed requirements of her new home. She could do whatever she wished. In the morning, she rode; in the afternoon, she paid visits; in the evening, she attended dinners and dances. When she was at home, she played with the household pets, read novels, and wrote letters. She had no domestic duties, few intellectual pastimes, and no religious observances to attend. She was told to simply enjoy herself, and she did her best to follow this gentle order. But after a short while, she wanted to be useful. She pestered Alice to give her something to do, and Alice reluctantly allowed her to arrange some meals, order a few things at shops, and keep some household accounts.

The members of the Family Square formed a tight group who encouraged, appreciated, and supported each other. When Trix arrived, the three older Kiplings were all busy writing essays, stories, poems, and reviews. There were pens and ink in every room of the house. Lockwood served as special correspondent for the Bombay Pioneer and was a brilliant artist. Rudyard was a talented amateur caricaturist and illustrator. Both Rudyard and Alice served as reporters on the local social scene for the weekly papers. Alice, who had been publishing poems and stories, had an ear for a false rhythm or a false sentiment and worked with Rudyard to develop his writing style, correcting his poems and prose. Trix naturally and easily picked up a pen herself and joined in with her family on their various projects.

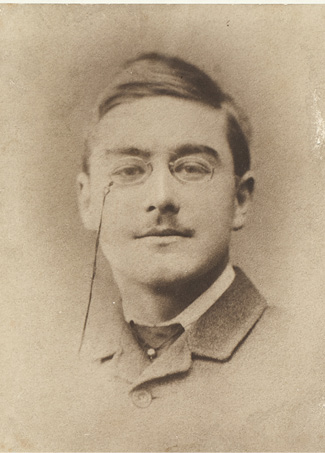

The parents were proud of their two obviously gifted and clever children and were pleased having them at home and showing them off abroad. Rudyard laboured hard and long at The Civil and Military Gazette, leaving himself little time to enjoy a social life. Still devoted to Flo Garrard, he avoided other romantic encounters. Trix, the youngest, was not expected to produce anything, although her scribbles were met with approval. She was praised simply for being pretty and polite.

Trix and Rud, who had played word games and invented stories when they were children, were often together now with pen in hand. In Trix’s first year at Lahore and Dalhousie, she and Rud played what they called pencil and paper games, scribbling together through the long evenings. Collaborating or more often competing with each other, Trix and Ruddy wrote clever imitations of the poets they both knew, from Tennyson to Whitman. Parody was easy for Trix. She was a facile imitator of other poets’ styles, and despite her age (she was only sixteen), she wasn’t shy about mocking the verses of older, famous writers. For their own amusement, Trix and Rudyard lolled around the table together, reciting lines aloud, breaking in on each other to approve or correct the words, tone, and rhythm of each other’s poetic attempts.

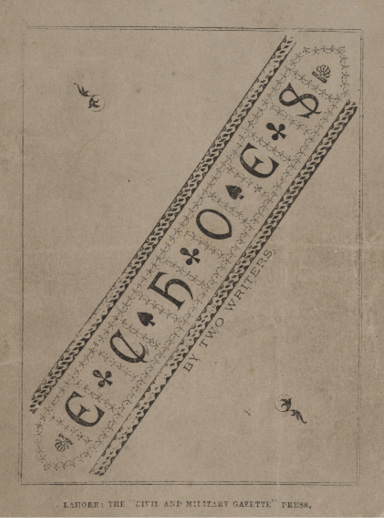

What they considered just playing around was recognized by the parents as accomplished verse and resulted in a little book called Echoes, by Two Writers—a collection of thirty-nine imitations and parodies in verse. Eight of the poems were composed by Trix. ‘Hope Deferred’ was Trix’s imitation of ‘Hope’ or ‘De Profundis’ by Christina Rossetti, and ‘Jane Smith’ was her smart parody of Wordsworth’s ‘Alice Fell’. The book appeared in 1884, published by The Civil and Military Gazette.2 It made a modest but favourable impression on the local British community. The poems were published without individual attribution, and it was impossible for readers to know which had been written by Rudyard and which by Trix. All the poems were considered astonishingly clever for the two teenaged authors. Rudyard was nineteen and Trix sixteen when the book was published. Rudyard later said he found it difficult to disentangle her work from his own during this period because, working together in the same room at the same table, they not only tried to influence each other but, without trying, shared a sensibility for points of reference, rhythms, and language.

Fig. 7 The front cover of Echoes.

Both Rudyard and Trix considered imitation a fair way to learn from older poets, a clever way to show off, and a pleasant way to pass the time. Trix found it easier to imitate other poets than to attempt to write from personal experience or feeling. At sixteen, she had had little experience to write from. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem Aurora Leigh was important for Trix in identifying ‘mother want’. But Aurora, the heroine of the poem, disdains imitation and struggles to write true art. Trix seems never to have tormented herself with the desire to write serious art. Writing was a game, a frivolous and fun pursuit. Aurora Leigh scorned imitation.

And so, like most young poets, in a flush

Of individual life, I poured myself

Along the veins of others, and achieved

Mere lifeless imitations of live verse,

And made the living answer for the dead,

Profaning nature.3

One wonders what Trix made of the whole poem, how she responded to Aurora’s passionate plea to become a true artist. Trix, at this time, did not imagine herself to be or to become an artist. Writing was a happy pastime. One wonders further how Trix understood Aurora’s assertion that she would be not only a true artist but an independent woman. Independence was beyond imagination.

For the six cool months of the year, from November to April, the Kiplings lived in their large, dusty house at Lahore. In the hot season of 1884, the women left the parched plains of Lahore for the drenched greenery of the hills of Dalhousie. Alice chose the serene and beautiful Dalhousie, which Trix later referred to as ‘Dullhouses’4, rather than risk exposing Trix to Simla with its somewhat raffish reputation. In Dalhousie, where Trix was still allowed to be a child, she was at ease and comfortable. The only thing that made her uncomfortable was Alice, whose continued criticism, meant to eliminate what remained of her schoolgirl clumsiness, was a constant reproach.

When Rudyard came up to Dalhousie to visit, he and Trix played like babies, behaving disgracefully together, sharing jokes and a private language, giggling, teasing, and crumpling up with laughter. Having been denied the chance before, they took whatever opportunities there were now to behave like naughty children together.

Nearly every morning, Rud took Trix out riding, determined to teach her how to trot. She loved the lessons, walking out slowly in the dawn, then trotting back as hard as she dared. She bumped a good deal, as was natural for a beginner, but she didn’t mind. With the colour in her cheeks, her hair down and blowing about in the wind, and her hat jammed at the back of the head, she seemed to Rudyard as lovely as any girl could be. He rewarded her progress on horseback by buying her a side saddle. In exchange for having taught her to ride, Trix taught Rudyard to dance.

Riding out in the morning, the two roamed about on the slopes of the Himalaya Mountains, stopping to gaze thousands of feet below where rivulets cut across the valleys. Exploring on foot, they danced on stepping stones, ran up and down boulders, picked wild flowers, splashed in streams, and sailed bark boats and bread crumbs down the currents. On one outing, they came across a mother lizard who had laid five crimson eggs on the ground at the edge of a cliff. After exhausting themselves climbing and running, they went home singing at the top of their voices, simply for the pleasure of hearing how far the sound carried. They gloried in the wild freedom of the place, where they could sing as loudly as they liked and play as madly as they dared in their oldest clothes, unobserved and unafraid.

In her first summer at Dalhousie, Trix met up with her ship-board friend Maud Marshall, the clever bookish girl she had met on her crossing to India. Trix was thrilled to meet Maud again, a girl smart enough to appreciate the Family Square and its literary pursuits. Soon, Trix and Maud became constant companions—recommending, exchanging, and discussing books. Like most teenage girls, they also gossiped about other girls, handsome boys, and party clothes. Trix allowed Maud’s sister Violet to become a friend and confidante as well. In Dalhousie, the pretty and innocent Trix earned the name ‘Rose in June’,5 pleasing herself and her mother.

The following year, Alice concluded that her daughter was sufficiently sophisticated to tolerate the excitements of Simla and took her there in the hot weather. The arduous journey from Lahore to Simla began with the train to Umballa, followed by over 100 miles from Umballa to Simla over rough terrain in a ‘tonga’—a two-wheeled cart pulled by ponies. If the weather was poor or the fatigued travellers needed to rest, the trip could take three, four, or more days.

Simla, the most prestigious and the most disreputable of the Indian hill stations, had been carved out of the slopes of the Himalayas, whose snowy peaks rose up stupendously behind it. The remote village was tightly compressed along a high ridge in the cool mountains, where a strange collection of structures clung to the sides of the hills. Along the central upper Mall stood a Gothic church, mock-Tudor public buildings, an English hotel with wicker chairs and striped awnings, an imposing stone town hall, and Swiss-style chalets. Lower down, a hodgepodge of small shacks comprised the Bazaar. Still lower down the ridge were an open-air market and a park for waiting rickshaws and tonga taxis. Planted terraces and plains spread out in the foothills below. The entire place looked unusually, even defiantly, confused and incoherent; the buildings were at odds with one another architecturally and unrelated to the landscape, the native people, or their culture.

Fig. 8 The Play’s the Thing. Simla, 1884.

Fig. 9 A watercolour painting of Trix by Lockwood.

During the season, the jostle of the bazaar, the eager crowds strolling on the Mall, and the clatter of mountain ponies created a bustling confusion. Simla offered incessant entertainment to the frivolous, fashionable, pleasure-seeking grass widows and the holiday-making military men on leave. There were balls, races, polo matches, picnics, sketching parties, and amateur theatrics. Behind all the gaiety, there existed serious strivings for social supremacy and professional advancement. Petty intrigue and gossip flourished in this atmosphere.

Psychic enquiry was a fashionable past-time in many circles. Silly school girls as well as the most genteel Anglo-Indian ladies and gentlemen dabbled in psychic experiments and attended seances in darkened rooms. Theosophy was especially popular, as two local residents—Alfred Sinnett, editor of the Pioneer, and Allan Octavio (A.O.) Hume—were patrons of Madame Blavatsky’s newly founded religion. Even sober Lockwood Kipling attended a séance conducted by Madame Blavatsky. He concluded that she was an interesting and shrewd fake. Here in Simla, Trix was introduced to informal spiritual experimentation and entertainment. Alice, the eldest of seven sisters and a Macdonald of Skye, and her younger sisters all claimed to be receptive to occult experiences and gifted with second sight. Thus, Trix was following in an established female family tradition when she became interested in conjuring visions in a crystal and writing verse while in a trance.

Simla was also the summer seat of the government. The presence of the viceroy gave the place its exalted social standing. Among all the cool and moist hill stations, Simla held the supreme social status. When the Kiplings first arrived in Simla in 1885, the socially ambitious Alice was eager to enter into viceregal society. This was not easy to accomplish, as Lockwood, the curator of a museum, held a position at the low end of the Anglo-Indian hierarchy. Artists and intellectuals were not accorded precedence, and precedence was all important in Anglo-Indian social life. But when the Kiplings came to Simla, a new Viceroy had been in place for less than a year. The new Viceroy, Lord Dufferin—a sophisticated traveller, scholar, and wit—did not allow precedence to govern his choice of guests. He appreciated sharp and intelligent conversation more than social position. His wife, Lady Dufferin, was a celebrated beauty and fitting consort for her exceptional husband. The Dufferins discovered the Kiplings through their daughter Lady Helen, who studied drawing with Lockwood. They were immediately won over by the clever and charming Kiplings and welcomed them into viceregal society. Lord Dufferin was especially enchanted by the vivacious and loquacious Alice.

Staying at a cottage named ‘The Tendrils’ (later cottages were named ‘Violet Hill’, ‘Victoria Cottage’, and ‘North Bank’), Alice worked at advancing in Simla society. As the gossip columnist for the Bombay Gazette and The Civil and Military Gazette, she was obliged to know what was going on in Simla, and, as a mother, she used that knowledge to introduce her daughter into the respectable parts of Simla social life.

Trix succeeded without really trying. She was naturally beautiful and had become, with her mother’s constant criticism, graceful and slender. She astonished her many suitors with her knowledge of English poetry. One admirer claimed she could recite all of Shakespeare. When her talents became known to the theatrical society, she was invited to use her natural gifts on stage. She proudly displayed her talent for memorizing and reciting in the society’s plays. Rudyard somewhat reluctantly wrote witty prologues for the dramas, and, on several occasions, Trix had the special treat of reciting prologues written by her brother. On stage and off, Trix loved dressing in pretty clothes, favouring bright colours and floating draperies. When preparing for parties and balls, she fussed and fretted over her dress, her jewels, her gloves, her fan, and, of course, her fringe. She felt her best in black for the evening with coral jewellery, red shoes, and a red fan. When she tired of this dramatic combination, she decorated her dress with a gold bow, gloves, and a fan along with topaz jewellery. For the Simla Fancy Dress Ball of 1885, Trix wore a simple Caldecott Olivia Primrose dress designed by her father, and the next year, for ‘The Calico Ball’, another viceregal costume extravaganza, she represented Mooltan pottery in a dress designed by Lockwood in shades of blue. She was a great success in both dresses. She never passed a glass without giving herself an appraising glance. And most people agreed she was well worth looking at.

Fig. 10 Photograph of Trix in Simla.

Fig. 11 Trix in a Grecian costume, in 1887.

At first, Trix innocently and happily displayed herself, unaware of the dangers she was exposing herself to. But soon, she became aware that male admiration easily led to serious courting and even marriage proposals. She was not prepared for this at all. She had never been as content as she was living in the Family Square, and she did not want anything to interfere with this, her first truly happy time. She ceased encouraging suitors. She kept her eyes down when walking on the Mall and ignored the many bold glances and remarks aimed at her. At parties, she spent her time talking gaily to older colonels, majors, and captains, while paying no attention to young subaltern admirers who hovered hopefully around her.

Rudyard, who knew his sister well, became aware of this situation and became concerned that Trix, whom he referred to as the ‘Maiden’, was attracting more attention than she desired. Rudyard understood that she was unprepared for romance and worked to protect her from being rushed out of her childhood. He approved of her strategies to avoid serious advances and proposals and encouraged her to stay at home and concentrate on her writing, beseeching her to cling to the inkpot. Trix happily complied, writing poems and stories for Rudyard’s approval. Rudyard not only encouraged her to write, but also pestered her to submit her stories for publication. Trix was reluctant to publish but eventually allowed Rudyard to consider a ghost story she had recently completed. He was thrilled when she agreed to let him print it.

The ghost story was a form Trix knew well and found easy to imitate. The story she offered Rudyard was titled ‘The Haunted Cabin’.6 Within the conventional form, Trix expressed some of her most unacceptable and angry thoughts. ‘The Haunted Cabin’ has, at its centre, a merry ghost—a little girl named May Rodney. (May is the name Trix used later for the autobiographical heroine of her first novel, The Heart of a Maid.) The story is narrated by a young mother, sailing from England back to India with her three-year-old son, Robbie. She discovers that her cabin is haunted by a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, round-faced child of four. Dressed in only a nightgown and with bare feet, the child roams the ship. The child appears only to the young mother and her son. When they see her at a distance and try to approach her, she capriciously disappears. After repeatedly tempting them to follow her and then withdrawing, they conclude that she is a difficult and tiresome creature. But at the end of the voyage, the little ghost appears perched on the sill of the stateroom porthole when the young mother comes in to take a nap. As the mother enters the cabin, she startles the little creature into losing her balance. Unable to move, the mother watches helplessly as the child’s tiny hands vainly clutch at the air and the little golden head disappears with a ‘short stifled cry which was more like a sob than a shriek’. The young mother screams, and a stewardess comes to calm her, explaining that the little girl is a ghost, not a real child. The woman insists, ‘I tell you a child has fallen overboard and is dying—drowning! She must be dead by now, and it is your fault. They might have saved her if you had called at once! God forgive you for being so wicked!’ The stewardess explains, ‘you’ve seen little May Rodney. She fell out of this very port six years ago […] She had been sitting on the sill of the port leaning out, and her mother came in and spoke to her suddenly, and she was startled and fell […] I didn’t hear her scream. It must have been a very soft, stifled little cry’.

It is difficult not to read the story as describing a piece of Trix’s own early history. At three, golden-haired, blue-eyed Trix had sailed to England and had been abandoned without warning at Southsea. Her cries, soft and stifled, were never heard at all. Her bright young life slipped away, unvalued, unheard. In the ghost story, there are two mothers, the mother of Robbie who narrates the story and the mother of ghostly May Rodney. Both mothers prove themselves helpless to ward off catastrophe. The ghostly child roams about the deck improperly dressed and unattended in dangerous situations. Her capricious comings and goings vex the narrating mother rather than alarm her. Annoyed by finding the child sitting perilously on the sill of the porthole, she speaks sharply and precipitates the same catastrophe that had occurred before.

At the age of seventeen, Trix was not prepared to write directly about the misery of her childhood in fiction or memoir, nor was she prepared to cast blame for that misery. Instead, she worked within a well-known and highly stylized genre—the ghost story—to express her feelings about a crucial piece of her own history. Here, a young mother is haunted by a lost child. The mother is doomed to watch as the child slips helplessly away with a muffled cry. Trix believed herself to be a child who had been thrown away, and here she created a mother who recognizes what she has done to her innocent child. The central act of the story, maternal carelessness, and its result, the death of a child, lead to the somewhat crude moral of the tale. If you neglect your child, she will die and you will suffer endless remorse. Trix’s first published story can easily be read as a thinly disguised accusation against her mother and a fitting punishment for her.

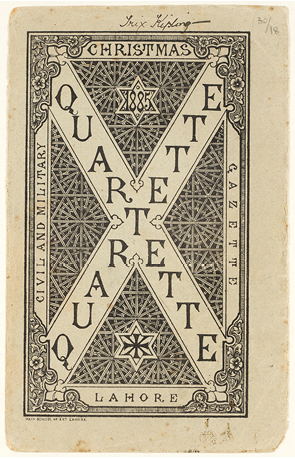

The story was published along with a group of stories and poems by the three other members of the Kipling family in Quartette in 1885. The volume had only one contribution by Trix, this seemingly inoffensive ghost story.

Fig. 12 The front cover of Quartette.

In all of her social activities, Trix was accompanied by her accomplished and confident mother. During her first seasons, Trix struggled to overcome her shyness. She wanted to become composed and calm, like her mother. She knew that Alice was recognized as a beauty and a flirt, while she was seen as little more than a pretty child. When Trix eventually conquered her nervousness and began to be noticed, Alice seemed pleased. But when Trix began to shine, Alice was not altogether pleased to be thrown into the shade by her brilliance. In 1885, Rudyard published a poem titled ‘My Rival’, in Departmental Ditties.7 The subject of the poem is a rivalry between a forty-nine-year-old mother and her seventeen-year-old daughter, the ages of Alice and Trix at the time. The poem is usually attributed to Rudyard alone, although some give the sole credit to Trix. Trix herself described it as a spontaneous collaboration between the brother and sister, arising from a passing remark. One morning, when she and Ruddy were walking together along the Mall in Simla, a rickshaw passed by with a stout painted matron inside, accompanied by a smiling youth. The night before, Trix had had a dull time at a dance. She had actually sat out two or three dances. As the rickshaw passed, the older lady called out, ‘Hullo Darling, walking with your Brother, wonders will never cease’. Trix turned to Rudyard and said bitterly, ‘there goes my rival! She never sits out’. Rudyard laughed and said, ‘Jove! There’s a verse in that’.8

MY RIVAL

I go to concert; party, ball–

What profit is in these?

I sit alone against the wall

And strive to look at ease.

The incense that is mine by right

They burn before Her shrine;

And that’s because I’m seventeen

And She is forty-nine.

I cannot check my girlish blush,

My color comes and goes;

I redden to my finger-tips,

I’m very gauche and very shy,

Her jokes aren’t in my line’

And, worst of all, I’m seventeen

While She is forty-nine.

The young men come, the young men go

Each pink and white and neat,

She’s older than their mother, but

They grovel at Her feet.

They walk beside her ‘rickshaw wheels–

None ever walks by mine;

And that’s because I’m seventeen

And She is forty-nine.

She rides with half a dozen men

(She calls them ‘boys’ and ‘mashers’)

I trot along the Mall alone;

My prettiest frocks and sashes

Don’t help to fill my programme-card,

And vainly I repine

From ten to two A.M. Ah me!

Would I were forty-nine.

She calls me ‘darling’, ‘pet’, and ‘dear’,

And ‘sweet retiring maid’.

I’m always at the back, I know,

She puts me in the shade.

She introduces me to men,

‘Cast’ lovers, I opine,

For sixty takes to seventeen,

Nineteen to forty-nine.

But even She must older grow

And end her dancing days,

She can’t go on forever so

At concerts, balls, and plays.

One ray of priceless hope I see

Before my footsteps shine;

Just think, that She’ll by eighty-one

When I am forty-nine.9

Whether written by Trix or Rudyard or as a collaboration between the two, the poem clearly expressed Trix’s annoyance at her mother. Trix wrote directly to her friend Violet Marshall (Maud’s sister) about her competitive feelings for her mother. She recalled her early shyness and lamented that she had earlier sat ‘as dumb as a fish while men talked to Mother. Now it sometimes happens that if there are not two men Mother goes on alone & the man rides by my rickshaw & talks to me. I like that’.10 While she was pleased with these small triumphs, Trix continued to be worried about their larger consequences—unintentionally encouraging serious suitors.

As she entered into her second season at Simla, Trix well understood that continuing to flirt was a dangerous game. She retreated into herself, causing her pet name to change radically from ‘Rose in June’11 to the ‘Ice Maiden’.12 In order to remain in childhood, a stage she had not been allowed to enjoy before and was happy in now, Trix cooled herself down. This chill did little to deter suitors. She resolutely turned down all offers, including several from Irishmen. In her first year at Simla, she had four proposals, in her second year, three. She assumed that, by the law of averages, there would be more in the next year.

Trix may not have been aware, but Alice certainly was aware that Trix was judged not only by her talents and beauty but by her social standing and financial status. And she had neither position nor provision. Many ambitious young men, eager to make an advantageous match, avoided her. But many other men appreciated her for her beauty, poise, and wit and were untroubled by her lack of status and money. Trix found that even a brief conversation on the Mall or a single dance at a ball too often led to a proposal she did not want to entertain but felt uncomfortable having to refuse. She found herself repeatedly caught in distressing situations that forced her to be rude or seem insensitive.

Alice, on the other hand, was pleased that Trix had so many suitors. Husband hunting was her job. She understood Trix’s discomfort and sympathized with her, but she could also make light of the situation Trix often found herself in. Together they teased each other. Trix often vexed her mother by sighing dramatically, ‘Oh horrible fate! He’s going to adore me!’ when she was encouraged by Alice to ride or dance with someone she didn’t care for. Once Alice asked her if she was getting to be like Miss Barbara Baxter; it was Miss Baxter who ‘refused all the men before they axed her’.13 When an unexpected offer surprised and pained Trix, Alice tried to console by saying, ‘Poor dear—you never have any lovers only men who want to marry you at once’.14 The pleasures of the chase did not attract Trix.

The Pater was more sympathetic, but hardly helpful. While Alice often encouraged unwanted suitors, the Pater discouraged all comers. He often lamented that he did not have enough money to make Trix independent, begging her to study hard so she could be a governess after his death. Trix, with unusual sharpness, pointed out that he should then have left her at school instead of taking her out at fifteen. She reminded him that her Head Mistress had encouraged her to stay for at least two more years and perhaps go on to Girton College. This had never been considered as a real possibility. Independence was not a choice for a pretty and popular girl.

During her second season at Simla, Trix attracted the attention of the Viceroy’s son, Lord Clandeboye. Trix was flattered by the flurry of praise and wonder that attended this aristocratic notice, but she was not interested in the young lord. Alice was thrilled, but the Dufferins were not delighted by the possibility of a match between their noble son and a poor girl. Lady Dufferin suggested to Alice that Trix be sent to another hill station. Feisty Alice suggested that it should be Lord Clandeboye who be sent away. And it was the young lord who went home. The Kiplings were pleased that they were so highly valued by the Dufferins that this difficult situation was resolved without any loss of love between themselves and the ruling family. Trix understood that a penniless wife was the last thing Lord and Lady Dufferin wished for their son.15 She was untroubled by the whole situation, which excited other members of the family and the community far more than it did her. She was relieved when it was all over.

Another of Trix’s suitors was Rudyard’s fellow journalist and best friend in India, Kay Robinson. He met Trix when she was just eighteen. Robinson was immediately beguiled by her, impressed by her literary memory and her witty conversation. He admired her statuesque beauty and was especially charmed by the loveliness of her face in repose, and her face was rarely in repose. When he expressed his feelings to Rudyard, Rudyard heartily discouraged him, vowing to declare war on him if he were to write to their parents. Rudyard was appalled at Robinson’s audacity in approaching Trix. Although Robinson, a literary and cultured man, would have made a suitable husband for Trix, he did not dare to approach her.

When another suitor continued to pursue Trix, she complained to Rudyard and asked him, ‘What am I to do?’ He responded, ‘Shoot the brute!’ ‘That was all the help I got from him,’ Trix concluded.16 Rudyard was certain that Trix didn’t care for the man and would laugh at him. Rudyard was furious that someone might dare to smash the Family Square. He was intensely, even violently, interested in keeping Trix at home and with him for a while longer. Rudyard admitted that he had his own selfish motives in holding Trix back. He wrote to Margaret Burne-Jones about his ‘intense anxiety about the Maiden’ and his ‘jealous care lest she should show signs of being “touched in the heart.” […] Of course we can’t hope to stave off the Inevitable [marriage] but I promise that unless he is a most superior man, I’ll make it desperately uncomfortable for the coming man—when he comes. I want two years more of her if I can get it’.17 Rudyard, who knew his sister well, was conscious of Trix’s lack of feeling for any of the men who approached her. While his interference in Trix’s love life was for his own peace of mind, it also served Trix. She was grateful for Rudyard’s possessive interference. While Alice pushed Trix forward, Rudyard tried to hold her back. Trix knew the inevitable was coming and tried to enjoy the time she had with her family.

Trix may have been in love with one of her many suitors, or more likely wished herself to be in love. One bold young soldier, after dancing with Trix at a ball, pledged himself to her forever. She was doubtful of his intentions when he went off to Burma, where he was killed in an attack on a fort. The doomed soldier may have touched her heart, but it seems unlikely. It is more likely that Trix found it easier to bemoan the loss of a gallant lover than to account for her reluctance to consider the proposals of her many suitors. The story of the tragically lost lover was one she liked to tell (and much later told in a short story), but it is hard to believe.

In the fall of 1885 after the busy season in Simla, Trix settled back into the joys of the Family Square once again reunited in Lahore. As the weather cooled, Alice suffered from an unusual bout of rheumatism in her left shoulder. Dr Elizabeth Bielby, the Punjab’s first woman doctor and Professor of Midwifery at Lahore Medical School, was called in to attend her. Trix had met this woman before at Bikanir House, which had become Lahore’s nearest equivalent to an intellectual salon. Of the smart and influential people who visited, seeking Lockwood’s advice and enjoying Alice’s hospitality, Dr Bielby was the one who most impressed Trix. When the doctor came to examine Alice’s shoulder, Trix used the occasion to exhibit her nursing abilities. She carefully looked after the patient as well as the house, showing off for the new woman doctor. She was anxious to win permission to attend Dr Bielby’s lectures. In recognition of her obvious interest, the parents allowed Trix in early 1886 to attend the doctor’s lectures and, for a short spell, she was ambitious to become a nurse. From attending the lectures, she proudly received ambulance certificates. She was not encouraged to continue with this interest by Rudyard or the rest of the family. She was positively discouraged by Alice, who considered such a life to be beneath her beautiful and talented daughter. Trix’s charms were meant to secure a brilliant husband.

Fig. 13 Rudyard in Lahore in the 1880s.

When not attending parties or imagining herself a nurse, Trix remained attached to the ink pot. After the publication of Echoes and Quartette, Rudyard and Trix went on with their literary games—writing poems, stories, parodies, and pastiches together.

In 1886, Kay Robinson took over the editorship of The Civil and Military Gazette (CMG), where Rudyard’s reputation as an editor and contributor was growing. Hoping to put a little sparkle into the dull publication, Robinson instituted ‘turnovers’—light 2,000-word pieces of local interest that began on page two or three and continued on the next inside page. Titled ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’, they were published anonymously. Robinson assigned the pieces to Rudyard, who, in turn, passed some of them over to his sister. Thirty-nine of the brief stories appeared between November 1886 and June 1887. Of the thirty-nine, Rudyard disowned seven (including the first two). Kipling’s bibliographer and most Kipling scholars agree that the tales not written by Rudyard were by his sister, Trix.18 While Rudyard sometimes attributed the creation of the clever punning title of the series to a family council and sometimes to Alice alone, he id not attribute any of the stories to Trix, either as hers alone or as hers in part. When Plain Tales from the Hills was published under his name as a single volume in 1888, Trix’s stories were properly omitted. But, upon their initial publication in the CMG, all the tales, his and hers, were unsigned and assumed to come from the same hand.

Trix, now more confident in her skills as social satirist, wittily and often witheringly described the Anglo-Indian social scene she had been participating in for a while. The first tale of the series, ‘Love-in-a-Mist’ (2 November 1886), tells the sorry story of newlyweds who, when left alone with only each other, become miserably bored after one day of marriage. Tale number two, ‘How It Happened’ (11 November 1886), describes a chance meeting between a young man and woman, who find themselves inadvertently and unfortunately engaged after one brief conversation. In story number thirteen, ‘A Pinchbeck Goddess’ (10 December 1886), a woman disguises her plain self to attract a husband and succeeds. (Ten years later, Trix expanded this story into her second novel, giving it the same title.)

Number eighteen, ‘A Little Learning’ (14 February 1887), tells of a young woman who, having attended nursing lectures, believes herself competent to act as a doctor to her ailing aunt. In her overconfidence and self-importance, she does more harm (although not lasting) than good. In the end, she is scolded and humbled for her presumption and punished cruelly for it. This story is the most autobiographical of the group and describes Trix’s feelings about wishing to have a useful career as a nurse or doctor. Betty, the young nursing student, is ‘an enthusiastic girl, with strong ideas concerning Woman’s Mission and Work in the World and their Duty’. She believed that ‘Every one should have a Vocation, a Purpose in Life; and she had tried hard to find hers. She had been forced to realize that she could not be an artist, author, actress or musician; but no matter, she would be useful and practical, doing actual good […] she would be a nurse. No—a lady doctor […] Unfortunately for her high resolves, she had a prejudiced and narrow-minded father and mother, who imagined that their daughter would be better and happier living with them in India, than studying medicine in London’.19

Trix may have had the same high resolve as her character, Betty, but, like her, she had been convinced by her ‘prejudiced and narrow-minded’ parents that she ought not to aim for anything but marriage.

These four stories (‘Love-in-a-Mist’, ‘How It Happened’, ‘A Pinchbeck Goddess’, and ‘A Little Learning’) are, without question, by Trix. Other stories most likely by Trix are number fifteen ‘Our Theatricals’, and number seven, ‘Love: A ‘Miss.’’ All six of these stories, which originally appeared in the CMG under the title ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’, were omitted when Rudyard published the stories as a collection, indicating that they were not by him. All six of Trix’s stories were good enough to appear with Rudyard’s and were assumed to be by the same author. Rudyard had been praised for his precocity, writing these stories when he was only twenty-one. Trix was only eighteen when she wrote hers. Several other stories, especially those with a female point of view or central female presence suggest Trix’s active participation. Rudyard never acknowledged that he collaborated with Trix on the stories, and she never claimed her share in them. Thus, it is difficult to assert absolutely that they were a shared effort, but much internal evidence supports her guidance in feminine matters.

By the time Trix was nineteen, she had come into full recognition that, like most girls, she would marry. It was clearly her mother’s wish that she marry, her society’s expectation that she marry, and her own scant knowledge of other possibilities that recommended marriage to her as her only possible path. Trix had been taught that duty, not love or happiness, ruled a woman’s existence, and her duty was to marry.

Rudyard, now twenty-one and promoted to special correspondent on The Pioneer in Allahabad, had moved up to the more senior position at the more important paper. He was therefore away from home much of the time, leaving The Family Square an unbalanced triangle with Trix perched between her parents.

Although Trix was still comfortable at home, she felt some tension between herself and her mother. She believed that Alice was becoming impatient to have her off her hands once again. Always prepared to think of herself as excess baggage, Trix began to feel that it was time for her to unburden her parents of her care. It was time for her to end her time as a dependent daughter and to take her place in society as a wife.

In itself, this is disturbing, but it is doubly so given Alice’s own premarital history. She too came from an impecunious family, with many daughters to marry off, not just one. From the age of fifteen to twenty-seven, she had amused herself with a series of romantic interludes and broken engagements—twice to William Fulford and once to William Allingham—and hung on the family tree until the ripe age of twenty-eight. Although she and her sisters were in competition over finding the best husbands, the parents brought little pressure on the girls, confident that they could choose well for themselves. When Alice at last decided on John Lockwood, to whom she remained engaged for almost two years, the parents waited patiently for the marriage to take place. Without similar compassion, Alice prepared to hustle her sensitive child into marriage, believing that Trix’s fragile and clinging nature required a strong male protector.

Alice fretted not only about Trix but also about Rudyard and encouraged both to accept or at least entertain romantic prospects she found promising. Both brother and sister were openly disdainful of Alice’s marital projects. While Rudyard could dismiss Alice’s interference, Trix could not ignore it.

One of Alice’s more inappropriate choices for Rudyard was a young woman named (Augusta) Gussie Tweddell. Gussie had met Rudyard at a dinner party and had confided to him that she wrote verse. Alice thought that Ruddy ought to fall head over ears in love with the poetry-writing girl, and she pressured Trix to ask her in for tea. When Gussie sent some of her poems over in advance of her proposed visit, brother and sister were appalled. The packet of poems arrived as the two lounged about on the softly cushioned sofa in the large, bright drawing room. Rudyard declaimed the poems aloud for Trix’s entertainment. Then she, snatching the pages, read aloud to him. Together, they mocked the poor girl’s execrable poetry and excruciating sentiments. Trix, who had no patience for girls who moaned over silly affairs in vile verse, was especially unkind. Alice thought them both ‘hard hearted cynics’ when she walked in on them shrieking and howling with delight at the recitation. ‘How did I ever bring you two into the world?’ asked Alice, as Trix pranced about the room spouting poor Gussie’s rhymes and vowing in between the lines that such an idiot should never come to her girls’ teas. All the while, Rudyard sprawled on the sofa, grinning and bellowing from time to time.20

While Trix was flattered by the many proposals she received, she was unmoved by all of them. Her many marital prospects were indistinguishable to her—all equally possible and impossible, likely and unlikely. Neither Kay Robinson nor the Viceroy’s son had excited her. Yet, she realized as she approached twenty that she would have to make a choice, that marriage was inevitable. From the several suitors who were available to her at the time, she chose one. Their first meeting was ‘dull and average’ compared to the often told fairy tale story of Alice and Lockwood’s first meeting at Rudyard Lake. In her diary, Trix wrote: ‘Danced with two new men—both fairly pleasant—Capt Taylor and M. Fleming—the former I never saw again—the latter called next day’.21

Tall and handsome John Murchison Fleming was a soldier from a soldiering family. His father had been a respected Army doctor. John, always called Jack, had served with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers during the Afghan War of 1880-81 and had taken part in expeditions north of the Khyber Pass and east across the border into the Laghman Valley. He was an excellent draughtsman and painted in watercolours, skills that were useful when he was seconded to the Survey of India in July 1885. The Survey, which served as the mapping unit of the government, provided topographical information about the frontiers of the Raj, and often gathered military and political intelligence. Members of the survey were thought to be engaged in espionage in addition to their other duties. Jack was ten years Trix’s senior, a stiff Scotsman of no remarkable achievement, from a family of some minor distinction. Tall and dashing in his military uniform, he was most remarkable for his good looks. He was not intellectual or artistic and had little natural sympathy for Trix’s story-writing or poetry-reciting. He and Trix ‘scarcely shared one thought or pleasure. He was Army to the toe-tips and looked on all writing or painting as rather riff-raff stuff’.22 He was an odd choice for a girl who might well have been able, despite her lack of position, to find a more appropriate, more sympathetic partner. But he was her choice. After a brief courtship and a dramatic proposal on horseback, Trix became engaged to Jack Fleming at nineteen.

While Alice pushed Trix forward, Lockwood made a weak attempt to hold her back. It was Rudyard who recognized and sympathized with Trix’s reticence. Rudyard understood that Trix was ambivalent not about marrying Jack Fleming but about marrying at all. He wanted to help her, but she did not make it easy for him to either comfort or advise her, unaware herself of exactly what was troubling her. If anyone would have been able to help her, it would have been Rudyard, who understood her better than anyone else in the family. But she did not know how to ask for help.

Alice was relieved that Trix had managed to make a choice. She was neither pleased nor displeased by the choice itself, but Rudyard disliked Fleming and thought him a poor match for his sister. ‘He’s an unresponsive sort of animal but appears an honest man,’ Rudyard wrote to his cousin, Margaret Machail.23 Lockwood liked him no more than Rudyard did and predicted that Trix would grow weary of him soon. While Lockwood had some knowledge of his daughter and her needs, he had very keen knowledge of his wife and her views about Trix’s future. He was in the habit of acquiescing to Alice on most domestic subjects, and, on this particular matter he was not going to contradict her views nor countermand her plans. Although Rudyard had objections, he too bowed to his mother’s determination.

Trix, who had her own doubts, strengthened by Lockwood and Rudyard’s lack of enthusiasm for the match, soon broke off the engagement. She had not been compelled to accept Jack, had given herself time to make the choice, but then, after only three months, found herself so unhappy and uncertain that she could not continue.

Alice was distressed by her daughter’s capricious change of plans. Rudyard was sympathetic, but he had little understanding of his sister’s initial choice of Fleming or of her subsequent rejection of him. Lockwood, recalled to England on business matters, was unavailable to voice his objections. When Trix told Rudyard that she was allowing Jack to continue to write to her after calling off the engagement, Rudyard recalled how Flo Garrard had prolonged his agony, like a worm on a hook, by permitting him to hope. Identifying with Fleming in this one instance, he counselled Trix to make a complete break for the young man’s sake. Trix, attempting to follow Rudyard’s advice, was firm in her refusal to see Fleming, but she was confused by her own unhappiness and indecision.

Five months later, while Lockwood remained in England attending to his affairs, Alice, Trix, and Rudyard were invited to stay outside of Simla at ‘The Retreat’—the country house of Sir Edward Buck, the Secretary to the Government of India. They happily accepted the invitation to stay at this splendid English-style house, with its extensive gardens of rare flowering plants, imported fruit trees, and large vegetable beds. Sir Edward grew rhubarb, mushrooms, English pears, and strawberries. One bright and blustery afternoon, Trix asked Ruddy to walk with her over a hillside blooming with wild raspberries and strawberries. She needed advice and hoped that, in private, among the vines and berries, Ruddy would help her. Alone on the hill, she sank down on the ground and poured out her troubles. Haltingly, she told Rudyard that Jack had insisted on another last-despairing interview with her the morning before, and, while she had persisted in her refusals, she had been shaken by his appeals and protestations. She had told Jack that she was indifferent to him, but he had persisted with unreasonable and unfounded self-confidence. When she had told him directly that she did not love him, he had been unfazed. He had relentlessly pressed his suit. He had accepted her lack of feeling and in turn had told her with perfect self-assurance that she would learn to love him. She did not know what to believe.

Trix had not tried to hide her true nature from Jack. She felt comfortable enough with him to admit her lack of romantic feelings and trusted that, by telling him the truth from the start, she would have an explanation and excuse for any later coolness. She was confused and sad that she didn’t have romantic fantasies and feelings and was candid in confessing their absence to a man who had proposed marriage.

She told Ruddy all she could, and then, shivering with cold and confusion, she burst into tears. Sitting among the pine-needles, she shook and sobbed, hoping Ruddy would have words to comfort her. He had only a few, and they hardly helped. Recognizing that she would get little help from Ruddy, she pulled herself together and, half crying and half laughing, stood up and brushed herself off. To end the awkward conversation, Trix started some silly chatter, concluding that never, since the world began, had there been a sorrow like her sorrow. Back on their feet, they returned to hunting for raspberries until Trix’s tears were dried and their fingers were blue-red. Trying to recapture their earlier playful days and happier moods, they began to steal from each other’s vines and throw pine-cones at each other’s heads. But somehow, the foolishness was not amusing, and, when Trix collapsed on a rock and said, ‘Oh how miserable I am!’ it was clear that they could not play at being babies any more. Thus, they came home solemnly to tea and announced to their mother that they had had a riotously jovial afternoon.24

Trix’s tearful explanations only confused Rudyard. They failed to account for what he could see was her very real misery. Rudyard was not sure if Trix was uncomfortable because Fleming’s relentless pursuit caused her to reject him over and over again, because she cared for him too much, or because she didn’t care for him enough. She seemed overwhelmed by her inability to know her own heart and, at the same time, she despaired to find herself acquiescing to another’s will. Rudyard said that she told him ‘as much about it as a woman would ever tell a man’.25 This was her modest excuse for ending their conversation. Trix’s feminine modesty may have inhibited her, but simple emotional fatigue may have worn her down. Fleming’s stolid insistence moved her towards his point of view, as did her mother’s warm approval of Fleming’s suit. Pushing her in the opposite direction was Rudyard’s disregard for the man. Her own point of view was a muddle. Behind the muddle was Trix’s knowledge that she would soon have to marry someone, and Fleming had seemed as likely a choice as any other. Now he seemed more likely than any other. But she was also aware that she did not love him. She was bewildered and genuinely miserable.

Two days after this tearful conversation, Trix and Rud awoke to find their mother in bed, past her usual hour, and complaining of feeling ill. Rudyard called the doctor, who, with some reservations, reassured the children that the illness was not serious. Trix spent the day at her mother’s bedside, relieved to have her mother’s health to worry about rather than her own romantic dilemma. After a day of waiting and watching at twilight, just as Alice’s fever was at its height, Jack turned up in the front garden of The Retreat. He was off his head completely and begged Trix for a quarter of an hour, a few minutes, any time at all. Weary from nursing Alice and worn out from having to repeat herself over and over to Jack, Trix promised Rudyard she would get rid of him with dispatch. Reluctantly, she went downstairs, intent on dealing with him in the space of fifteen minutes. After more than the allotted time, Jack finally went away, leaving Trix on the verge of tears. She restrained her tears but complained bitterly to Rudyard about having to repeatedly reject Jack’s unwanted pleas. Expressing these thoughts made her feel more at ease, as she dragged herself back upstairs to check on her feverish mother. When, after a while, Alice seemed to be resting comfortably, Trix left her mother’s side and returned downstairs.

There, she found Rudyard looking haggard and complaining of hunger. Putting their worries aside, they sat down and had a sad little dinner together. Trix, trying to display good humour and good cheer, said amidst her tears, ‘It’s not nice to have to make poultices with one hand and stave off an importunate lover with the other. Now if I could clap the poultice on his mouth…’26 Trix was pleased to see a slight smile appear on Rudyard’s face. Then she and Ruddy fell to laughing and joking, thinking up fresh torments—Trix falling off a horse, Kay Robinson collapsing in Lahore, and so on until they convinced themselves that they were cheerful again.

Trix concentrated on caring for Alice, distracting herself from fretting over Jack by exercising her nursing skills, but she was annoyed at them both. And she missed Jack. She attempted to be cheerful, hiding her confused feelings from Rudyard, but he recognized that something was not right. Ten days after the last meeting with Jack, when Trix was having trouble hiding her feelings, Rudyard appealed to her for some explanation. She was wandering aimlessly in the garden, when Rudyard found her, shook her gently but firmly, and demanded that she tell him what was the matter. Finally, she confessed that she had changed her mind again and wished to see Jack once more. When Rudyard absorbed what Trix was trying to tell him, he felt that he had been ‘keeping two loving souls apart […] and unconsciously acting the stern parent’. After hearing Trix describe her attachment, he softened towards Fleming, ‘the poor, humble brute’ who had been banned from the house. Trix convinced him that the two only wanted to know each other better. She reassured him that there was to be no engagement; she only wanted to meet with him again. ‘Only let him see me,’ Trix pleaded, ‘and try not to hate him so and then—if there is another quarrel it will be all over—indeed it will’.27 Alice persuaded Rudyard to be lenient, reassuring him that letting them see each other and get to understand each other might as easily lead them apart as together.

When Jack next came to call, Rudyard rushed outside, caught him before he entered the house, and explained that, while he was as much annoyed with him as ever, he desired his sister’s peace of mind. Consequently, Jack wasn’t to stay at the Club making a ‘gibbering baboon’ of himself but was to come down to see Trix now and again with the assurance that he would not be regarded as a burglar and an assassin. Jack gratefully shook hands with Rudyard, highly pleased with the concession of resumed visits.

Without Lockwood’s dislike of Fleming to back up his own, and with mounting pressure from both Trix and Alice, Rudyard dropped his objections. He concluded, ‘Isn’t the heart of a maid a curious thing. I always thought that the maid was so wise and sensible. But she said to me, ‘in these things I’m no wiser than anyone else—and I care for him ever so much.’’28 In fact, she was less wise and less caring than most, having no strong feelings to help her make this crucial decision. Unhappy, confused, and bullied, she agreed to renew the engagement.

Thus, the engagement was reinstated, and wedding plans put into motion. When Rudyard learned of this final development, he said, ‘I ain’t one little bit pleased, but console myself with Mrs Kipling’s practical philosophy. Here it is. “The older I get the less inclined I am to bother about the future until it becomes the present. The future generally arranges itself.” So far good but how about the futures of other people—sisters par example—which are arranged it would appear by detestable irrepressible subalterns’.29 Rudyard was uncharacteristically forthright in his disgust with his mother’s carelessness. He sarcastically ‘consoled’ himself with her ‘practical philosophy’, the same philosophy that had allowed her to cast off her children with strangers, and that allowed her now to cast Trix adrift with an unsuitable husband.

Lockwood, away in England, on hearing the news of Trix’s re-engagement, feared that Trix might ‘one day when it is too late find her Fleming but a thin pasture, and sigh for other fields’. He found Jack ‘a model young man; Scotch and possessing all the virtues; but somewhat austere, not caring for books nor for many things for which Trix cares intensely’.30 After accepting Jack’s second proposal on horseback in the hills above Simla, Trix felt calmer. Once the decision was made, the situation secured, and the engagement announced, Trix relaxed. No longer pressured by her mother or by Jack, she felt excited and happy about the immediate prospect of the wedding. Between the engagement and the marriage, Jack had to return to England. Trix bore the separation bravely. While waiting patiently in Lahore for Jack’s return, she was happily occupied with mastering new house-keeping jobs. Alice, assured of her daughter’s future, was easier on her. Rudyard, finding Trix more carefree and light-hearted, felt at ease making fun of her rudimentary new skills, especially her attempts at cooking something she claimed was a cheesecake. He teased her about constantly writing letters to Jack and mooning over her photo-books, filled with the many photos they had taken of each other. Trix proudly jangled about the house ornamented with the jewels Jack had presented to her—pearl necklaces, curb-chain bangles, and three different engagement rings.

The decision to marry Jack—not the decision to marry at all, which had been made for her by her society and her mother—had been the first important decision Trix had made on her own. Up until this point, everything had been decided for her, but the choice of Jack Fleming was hers. Naively, she hoped that Jack’s ardour would compensate for her coolness, and that her mother’s firm direction would serve to replace her own weak will. She had little else to guide her. She felt little for Jack Fleming, but she was aware that she also felt nothing for anyone else and never had. She had had girlish fantasies of herself in love, had written romantic verses and love-sick letters, but she knew her own nature. If she had to choose a husband, she could do worse than Jack Fleming. He was tall and handsome and wore his uniform with distinction. Ten years older, with a position on the Survey of India, he seemed to offer security and protection. He had assured her that she would learn to love him, and in her hopeful innocence, she believed him. She wanted to love someone.

Rudyard was traveling in America at the time of the wedding. He was not present at the ceremony in Simla, when Alice Macdonald Kipling married John Murchison Fleming—an officer of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, seconded to the Survey of India. The date was

11 June 1889, Trix’s birthday. She had just turned twenty-one.

Fig. 14 Framed photographs of Trix and Jack early in their marriage.

1 Rudyard Kipling, letters to Edith Macdonald, 10–14 July 1884. Library of Congress.

2 Rudyard Kipling and Trix Kipling, Echoes, by Two Writers (Lahore: Civil and Military Gazette, 1884).

3 Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh (London: J. Miller, 1864), First Book.

4 Lorna Lee, p. 16.

5 Ibid.

6 Trix Kipling, ‘The Haunted Cabin’, Quartette (Lahore: Civil and Military Gazette, 1885).

7 ‘My Rival’, Departmental Ditties (Lahore: Civil and Military Gazette, 1886).

8 Trix Kipling, letter to Edith Plowden, 7 October 1936. University of Sussex.

9 ‘My Rival’.

10 Trix Kipling, letter to Violet Marshall, 28 August 1885.

11 Lorna Lee, p. 16.

12 Ibid., p. 18.

13 Trix Kipling, letter to Edith Plowden, 7 October 1936.

14 Ibid.

15 This is one of the few stories that older members of the Kipling Society (founded in 1927 for the advancement and appreciation of the life and works of Rudyard Kipling) know about Trix. When I have mentioned to members of the Kipling Society that I am working on Trix, many say, ‘Ah, yes, the one who captivated the viceroy’s son’. The story is flattering to Trix and to the entire Kipling family.

16 Trix Kipling, letter to Maud Diver, 24 May 1944. Edinburgh.

17 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Margaret Burne-Jones, 27 September 1885. Letters, ed. by Thomas Pinney, 2 vols. (Iowa: University of Iowa, 1990), vol. I, p. 94.

18 Plain Tales from the Hills (Lahore: The Civil and Military Gazette, 1886–1887). David Richards, Rudyard Kipling: A Bibliography (Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010). Richards cites Rudyard’s repudiation of ‘Love-in-a-Mist’ ‘How It Happened, ‘Love: A Miss’, ‘A Straight Flush’, ‘A Pinchbeck Goddess’, ‘On Theatricals’, and ‘A Little Learning’. Richards concludes, ‘Indeed, it is likely that the series was envisioned as a joint effort, like Echoes and Quartette. Certainly the overall title of Plain Tales From the Hills was decided in family council’.

Harry Ricketts in Rudyard Kipling: A Life (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2000), p. 95, writes, ‘Again the idea [of Plain Tales] originated in the Kiplings’ penchant for literary games. Although in his autobiography Rud referred only to a family council over the overall title, his sister was certainly a contributor, and it seems like that the series was initially envisaged as another joint effort, like Echoes.

Of the thirty-nine “Plain Tales” printed in the CMG, Rud later repudiated seven (including the opening two) and an eighth, ‘A Scrap of Letter’, has never been accepted as his. These stories – though the evidence is not conclusive – were probably Trix’s work. One, “A Pinchebeck Goddess”, was definitely hers, and it is hard to imagine who else could have written the others’. Lord Birkenhead in Rudyard Kipling, p. 87, writes, ‘It is probable that Trix also had her fingers in this particular pie [Plain Tales], and it was even suggested that she wrote several of the stories that appeared in the Civil and Military Gazette, but were not republished. Trix knew Simla better than her brother, and was able to give him a great deal of information about personalities’. Hilton Brown, in Rudyard Kipling: A New Appreciation wrote, ‘In the early Indian days, Ruddy and Trix worked closely together. It would be interesting to know how much of Departmental Ditties was first strung together by Trix, or how much of the recondite femininity of Plain Tales sprung from that shrewd judgement and delicate observation…’

Many of the ‘Plain Tales from the Hills’, while attributed to Rudyard alone show Trix’s helping hand, including ‘Lispeth’ (CMG, 2 November 1886), published as the opening story in most collections, and always attributed to Rudyard alone. The story is about a girl from the Hills, a savage who is taken in by a Chaplain’s wife, a good Christian woman. The good Christian woman deceives the poor girl as does her lover, who abandons her to return to England. Broken-hearted, the girl weeps over the map of the world and the unimaginable distance between herself and her lover. The innocent and ignorant girl seems likely to be a creation of Trix’s. Rudyard created few such girls as central characters.

‘Three and—an Extra’ (DMG, 17 November 1886), is told from the point of view of a young wife grieving excessively over the death of her baby. When her husband starts paying attention to another woman, the wife, recognizes the danger and plots successfully to win her husband back. ‘’Take my word for it, the silliest woman can manage a clever man; but it needs a very clever woman to manage a fool.’’ (CMG, 17 November 1886)

‘Miss Youghal’s Sais’ (sais is a groom) (CMG, 25 April 1887), has at its center, an Indian policeman who disguises himself as a groom and courts his beloved on horseback. The happy romance plot is more feminine than most of Rudyard’s fiction. ‘Bitters Neat’ features a young man who is blind to the affection of a girl, who loves him dearly. When he finally discovers her love, it is too late. ‘Yoked to an Unbeliever’ focuses on a young woman who loves a man who goes off to Darjeeling and leaves her. She marries another, and when he dies, she returns to find her first love. He has in the meantime married a hill girl who is ‘making a decent man of him’. In ‘False Dawn’ a man proposes to the wrong sister while riding at night in a fog. In ‘The Other Man’ a woman is forced to marry a man she doesn’t love. The one she does love comes to visit her, but when his rickshaw arrives, he is seated in it stiff and dead. ‘Cupid’s Arrow’ tells the story of a young girl who is pressured by her ambitious mother to marry a rich, older man she does not love. She cleverly defeats her mother’s plan by intentionally losing an archery contest.

19 Trix Kipling, ‘A Little Learning’, The Civil and Military Gazette, 14 February (1887).

20 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Edmonia Hill, 9–10 July 1888. Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 242.

21 Trix Kipling, letter to Edith Plowden, 7 October 1936.

22 Katherine Crossley, ‘Letter to Gwladys Cox’, in Lorna Lee, p. 95.

23 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Margaret Mackail, 11–14 February 1889. Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 289.

24 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Edmonia Hill, 28 June 28–1 July 1888. Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 223.

25 Ibid.

26 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Edmonia Hill, 4–6 July 1888. Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 232.

27 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Edmonia Hill, 15 July 1888, Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 254.

28 Ibid.

29 Rudyard Kipling, letter to Alexander and Edmonia Hill, 6 October 1888. Letters, ed. by Pinney, vol. I, p. 258.

30 John Lockwood Kipling in Arthur Baldwin, The Macdonald Sisters.