5. The Heart of a Maid

©2024 Barbara Fisher, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0377.05

Trix’s first novel, The Heart of a Maid, written only months after her marriage, begins with this scene.

Two riders rein in their horses. They are tiny figures against the backdrop of the towering mountains of the Himalayas. They make a striking pair perched on horseback high above Simla, queen of the North Indian hill stations. The man, tall and commanding in the saddle, turns eagerly towards the girl. She pretends at first not to understand that he wishes to speak, then reluctantly agrees to hear him out. Despite the manly posture of the man, the shy beauty of the girl, and the romantic elevation of the scene, a strikingly unromantic conversation takes place.

May Trent, twenty years old, an acknowledged belle of Simla society—beautiful, intelligent, and talented—rides with her handsome suitor, Percy Anstruther. May is not happy to hear a second proposal from her importunate suitor. Here is May’s response to Percy’s renewed unwelcome proposal.

‘What can I say that will be different from the last time?’ she said, her eyes filling with tears. ‘It is cruel of you to make me give you and myself all this pain again! You know that I don’t love you!’ Then, noticing the change in his face, she added quickly, ‘Oh! Don’t look like that! Please don’t, I can’t bear it. You force me to hurt you! I don’t love anybody in the way you want; I don’t think I ever shall. I must be a stone—I’m not worth caring for.’

‘Only give me a chance. Let me try and teach you to love me, darling,’ said Anstruther hopefully […] May unconsciously drew her reins tighter […]

‘Tell me what I should say. You know me better than anyone does. I am not happy at home; you have seen that. My parents think that they have been good to me long enough, that it is my bounden duty to get married […] That’s about the bitterest feeling a girl can have […] that her father and mother would gladly give her to any man who would take the trouble to support her […]

‘I shall regret having said this tomorrow, and be very much ashamed of it, but I will speak plainly for once. My mother was angry with me for refusing you last year, and said, that, as I cared for no one else, I should end by caring for you. Now I know you better than I did, but my feelings for you are unchanged. How can you ask me to marry you?’

‘It sounds hopeless, but I am not easily frightened […] Oh! Can’t you trust me, May? I am some ten years older than you, and I do not speak thoughtlessly […]’

‘I may look on you merely as a means of escape, then?’

‘As you will. I trust very much to time […]’

May had unwittingly worked herself into a state of revolt against her father and mother, and the life she had led for the last two years; sooner or later most girls feel, for a time at least, that anything is better than what they have […]

‘Yes, I will marry you,’ she said quietly; then, to her great surprise, she felt his arm round her, and as he kissed her, she realized what she had done.1

While it is simplistic to read fiction as a direct representation of the author’s life, as barely disguised autobiography, it is difficult not to read this scene as taken from Trix’s recent experience. Trix, like May, had received an unwanted second proposal from her suitor while spending the hot season in Simla. While she never reported the dialogue that preceded her acceptance of this second proposal, here in fiction she recreated the conversation that may well have passed between herself and her soon-to-be husband.

May agrees to marry Percy after he kisses her and then brutally crushes her hand. She knows that she does not have romantic feelings for him. She tells Percy that she has never loved a man as a husband wishes to be loved and believes that she never will. She asserts these beliefs with great certainty. She gives no explanation for her lack of feeling. This is simply how she is made. The narrator supplies these bits of explanation. May Trent and her mother had little sympathy for each other. They had not lived together, except for a few baby years, until May returned home at eighteen. The narrator comments, ‘This is one of the many evils of Anglo-Indian life […] for the enforced separation of parent and child, the alienation of years, cannot be done away with in a few months, and half the hasty, ill-assorted marriages that take place have for a cause the fact that the girl was not happy at home’.

Trix accepted Jack’s first proposal because she felt pressured to marry someone, and he seemed at first as good a choice as any other. After a few months, feeling uncertain and anxious, she reneged. After breaking off the engagement, she was aware that she had disappointed Jack, had irritated her mother, and was still faced with the same predicament—having to marry someone. When Jack proposed again, she accepted.

In the novel, May explains herself to Percy with stunning candour. She does not try to mislead him or misrepresent herself. And she seems to understand herself very clearly. Although she understands precisely how she feels, she does not at all understand why she feels this way.

Trix married Jack in Simla in June 1889 in a torrent of rain (an omen no one seemed to notice) with only a few family members in attendance. The newly married couple went off together on a tour of northern India. Just weeks into the honeymoon, Jack was ordered to interrupt the tour and leave for Burma to continue his work on the Great Survey of India. Trix did not accompany her husband to his new posting. Having been married for only a matter of weeks, Trix found herself deposited, like an unwanted parcel, back with her parents in Lahore. She had looked forward to a new role and a new life. Instead, she had been dispatched back to her family and was unexpectedly and unhappily reprising her old role as a daughter.

Alice and Lockwood took Trix in. Back with her parents, Trix had no wifely duties or family chores to take up her time, and she needed some occupation. Always comfortable with a pen in her hand, Trix picked hers up and started to write. Perhaps she had had the plot of this novel in mind for a while, perhaps she had only envisioned the dramatic proposal on horseback, perhaps she knew only the character of her heroine. The opening is surely and confidently written. The early years of the unhappy marriage ring true. The large cast of minor characters is clearly and competently introduced, and the scene in Simla is vividly set.

Although she had never written anything longer than a short story, Trix worked at a rapid pace on a complicated plot.

The novel continues:As May prepares for her wedding, she felt ‘that she was entering a dungeon, worn by the steps of those who had passed before’. Her prediction proves to be correct. Three months after the wedding, May knows that there is no sympathy or comfort in her marriage to Percy. Then, she has a baby. Suddenly and wonderfully, she discovers intense feelings of love for the baby. When her baby dies suddenly, she goes mad with grief, furiously and madly accusing her husband and her mother of murder. Eventually, she calms and apathetically agrees to voyage to England to meet her husband’s family. All places and people are the same to her.

Trix had reached this point in her novel when, in January of 1890, she was required once again to move. After less than six months of lodging with her parents, Trix learned that Jack, while in Burma on the Survey, had become ill with sunstroke and fever, possibly malaria, and was required to leave his post. He was on his way back to Lahore and to her. The comfortable routine that Trix had established was at an end. She was needed to care for her ailing husband. It was her duty to tend to Jack who, when she saw him, appeared to be a ghost. She was amazed at the sudden transformation of the strong soldier she had married into the pale patient who was now in her care.

Trix had been working steadily on her novel when Jack unexpectedly and, from a writer’s point of view, inconveniently arrived home. She had set her several sub-plots going forward and knew where they were to end. What she had not resolved was the central conflict of the novel—the uncertain outcome of the marriage between May and Percy. Would this shaky marriage survive?Jack’s poor health required not just abandoning his post, but prolonged home leave. This leave was soon granted and plans for the voyage home were set in motion. Trix needed to pack up all her things, bid farewell to her parents, and head home with her weak and defeated husband. Her novel was almost complete. She had a difficult sea voyage ahead of her, an unknown place to establish with Jack’s family, and an uncertain marital future to work out with her very compromised husband. She could have postponed finishing her novel. She could have put it aside indefinitely. With so many unpredictable events in front of her, she decided to hastily conclude her novel. Passage for the voyage back to England was booked just as Trix began to write the final scenes. She set those scenes on shipboard. The end of the novel takes place at sea.

The plot continues:

Feeling dull and despairing, May sails to England. On shipboard, she reflects on her own feelings and behaviour towards Percy. She blames herself for having been meanly unforgiving and spiteful. She did too little and expected too much. She was selfish and took pleasure in being miserable.

While at sea, she considers the histories of the other girls she knows and the one new girl she meets at sea and compares their feelings with hers. She recognizes that each of them had found some happiness, even as she had made compromises and had committed errors. The frivolous young woman who marries for money and position enjoys the real benefits she attains. May’s sister, although she does something shameful—being engaged while her fiancé’s mad wife still lives—will eventually marry him properly and joyfully. The girl who is advised to marry for wealth and position but chooses to follow her heart’s desire easily accepts the poverty that her choice includes. The new bride May meets on shipboard manages to find pleasure in what she has. May concludes that the lack of joy in her life is her own fault. Filled with regret and remorse, she vows to be a better wife. She recognizes in herself ‘a kind of disdain in her mind, which now grieved her as the commission of an actual sin might have done. Life had not given her its best, so she had refused to see any good in what she had, feeling even a kind of perverted pleasure in mourning over the ruins of her happiness, though she had not given a finger-touch to try and save it from ruin’.

Just as she reaches this self-critical and possibly life-changing conclusion, her story suddenly ends. The final line of the novel comes as an unexpected blow. ‘May never saw her husband again’.

The abrupt ending feels rushed and incomplete, as if the author could not imagine the heroine’s softened spirit and reformed heart, did not want to make the effort to imagine it, or, having struggled to imagine it, did not sufficiently believe in it. Allowing the heroine to remain angry, accusatory, and alone was another narrative possibility Trix could not fully imagine. A reader can almost picture the author throwing up her hands, putting down her pen, and walking away in defeat.

Before marrying, May confesses that she does not think herself capable of love, calls herself a stone, and warns Percy that she is not worth caring for. After marriage, she glories in her own unhappiness and refuses to work at love. She openly acknowledges her lack of sympathy and, in fact, utter disdain for her husband. She blames herself for her shortcomings. She does not pretend that her feelings are other than what they are, although they are inconvenient and unattractive in almost every way.

She knows she could be different, she wants to be different, and the novel briefly holds out the possibility of reformation. But change is denied to her. After dangling the happy ending of reconciliation and marital concord before the reader, the author suddenly and ruthlessly cuts the possibility off. This ending seems at first to be a punishment. May repents, but too late. But it is also a reprieve. She will not have to try to make this marriage work. She is free.

In 1890, when Trix wrote The Heart of a Maid, it was unusual for a novel to begin with a marriage proposal. Traditionally, the marriage proposal arrived as the happy conclusion of the novel. More exceptional is the heroine herself, who accepts the proposal with stunningly bad grace and continues to struggle unsuccessfully with feelings of coldness, indifference, and repulsion. Beginning with an uncomfortable marriage proposal, the novel continues to describe a marriage as it turns sour. The unhappy heroine places the blame for the collapse of her marriage not on society or on the institution of marriage but on herself. She does not doubt the rules of society nor her role in it. She is not a rebel. May insists that it is her own unfortunate temperament that is the problem.

May is an unusual heroine in her refusal to pretend. She is remarkable for her insight into herself and for truthfully expressing her unpleasant and unusual feelings of coldness, remoteness, and rage. May’s truth-telling feels, at first, like a breath of fresh air. But, as the novel progresses, her forth-rightness seems excessive and, at the death of her baby, it seems crazy. It feels good to May to be true to herself, but it also makes others feel bad. She wounds her mother and Percy. A truth-teller is simply who she is, who she must be. And she has terrible personal truths to tell.

Trix had no trouble describing this heroine and her prickly nature. She persuasively dramatized her discontent with her husband. Her passionate love for her baby and her extreme grief at the loss of the baby are less well developed. But most troubling of all was finding an appropriate and satisfying conclusion for such a heroine. Freed from her husband, and unburdened by other societal demands, she has nowhere to go. Finding no place for her to rest comfortably and feeling rushed to complete her story, Trix abruptly ended her novel inconclusively and inadequately.

The minor stories in the novel, variations on the traditional ‘Marriage Plot’, end well. Romantic desire drives the stories forward. The heroines are rewarded with marriage as the ultimate goal for achieving personal fulfilment and social integration. Courtship, romance, and marriage structure their stories and move inevitably to their happy endings. But May’s story is left suspended and untethered.

As Trix sailed home to England with her ailing husband, perhaps she pondered the many disappointments and few joys of her short marriage. Perhaps she vowed, after some initial failure, to be a better wife, a more loving partner. Perhaps she despaired, gave up hope of finding happiness with Jack, and wished never to see him again. Perhaps, as the ending of the novel intimates, less than a year into the marriage, Trix wished her husband gone or even dead.

Fig. 15 The front cover of The Heart of a Maid.

In 1891, slightly more than one year into the marriage, Trix’s novel, The Heart of a Maid, appeared under the name Beatrice Grange.2 The first name of Trix’s pseudonym derives from her nickname Trix, which seems to, but does not, have its origin in Beatrice. The Grange, her pen surname, was the home of her uncle and aunt, the Burne-Joneses, where she was born and spent happy school holidays. Publishing anonymously or using a pseudonym was common practice for women authors who felt the need to conform to Victorian modestly and decorum. Trix’s novel, bearing so close a resemblance to recent parts of her own life, demanded disguise.

Trix did not have to trouble herself to find a publisher for her first long fictional effort. Rudyard arranged for the novel to be published by A.H. Wheeler & Co., Allahabad, India, and issued in a paper cover as Number 8 of the Indian Railway Library. The first six volumes of this series consisted entirely of short stories by Rudyard Kipling, ‘Soldiers Three’, ‘The Gadbys’, ‘In Black and White’, ‘Under the Deodars’, ‘The Phantom Rickshaw’ and ‘Wee Willie Winkie’. These thin, cheap booklets were sold at bookstalls at Indian railway stations and had a wide circulation.

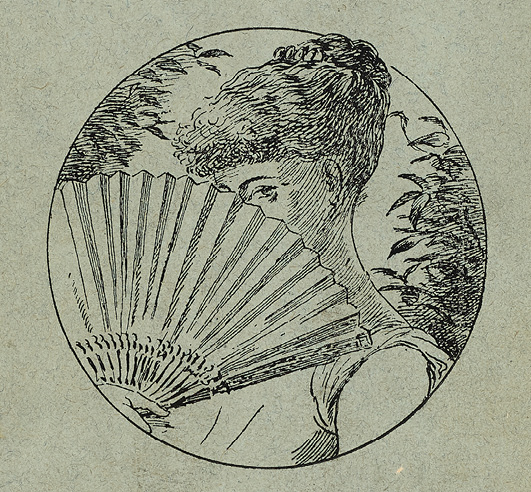

Fig. 16 The front cover of Under the Deodars, by Lockwood Kipling.

Fig. 17 The back cover of Under the Deodars, by Lockwood Kipling. This illustration is a portrait of Trix.

Trix’s novel was good enough to be published on its own merits, but it was especially attractive coming with a recommendation from Rudyard, the firm’s newest and most promising author. Thus, at twenty-two, Trix was the author of a published novel.

Publishing a novel at this age was a quite a feat for a young woman. Even Trix’s precocious brother had not yet published a novel. Trix seemed poised for literary success.